Essay on Philippines History

Students are often asked to write an essay on Philippines History in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Philippines History

Early history.

Long ago, people from Asia and Borneo came to the Philippines by walking on land bridges. These bridges are now underwater. These people were hunters and gatherers. They used simple tools made from stone and bone.

Trade and Influence

Between 1000 BC and 1521 AD, the Philippines was influenced by many cultures. Traders from India, China, and the Middle East came to the islands. They brought new ideas, goods, and religions. The locals learned to farm, make pottery, and use metal.

Spanish Rule

In 1521, Spanish explorer Ferdinand Magellan arrived. Spain took control of the islands and named them the Philippines. The Spanish taught the locals Christianity and Spanish. They ruled for over 300 years.

American Period

In 1898, the US fought Spain and won. The Philippines then became a US territory. The US introduced English and modern education. But many Filipinos wanted independence.

Independence

On July 4, 1946, the Philippines became an independent nation. The country faced many challenges like poverty and corruption. But it also made progress in areas like education and healthcare. Today, the Philippines is a vibrant democracy with a rich history.

250 Words Essay on Philippines History

Long ago, the Philippines was not one country but a group of small islands. People from different parts of Asia came to these islands by boat. These people were hunters and food gatherers. They used simple tools made from stone and wood.

Over time, other people came to the Philippines for trade. They brought new ideas and goods. These people were from China, India, and the Islamic world. They influenced the way of life in the Philippines. The locals learned how to farm, make pottery, and weave cloth.

In 1521, a Spanish explorer named Ferdinand Magellan came to the Philippines. The Spanish wanted to control the islands because of their rich resources. They ruled the Philippines for more than 300 years. The Spanish changed many things. They brought their religion, culture, and law to the islands.

In 1898, the United States took control of the Philippines from Spain. The American rule brought new changes. They improved education, health, and infrastructure. But, many Filipinos wanted independence.

On July 4, 1946, the Philippines became an independent nation. It was a big step for the Filipinos. They could now make their own laws and decisions. But, they also faced many challenges. They had to rebuild the country after World War II.

In short, the history of the Philippines is a mix of different cultures and influences. It is a story of change and growth. The Filipino people have shown resilience and strength in the face of challenges. They continue to strive for a better future.

500 Words Essay on Philippines History

The Philippines is a Southeast Asian country with a rich and complex history. The early history of the Philippines dates back to around 50,000 years ago when the first humans arrived from Borneo and Sumatra via boats. These early people were known as Negritos, who were followed by the Austronesians. The Austronesians introduced farming and fishing techniques to the islands.

In the 10th century, trade began with nearby Asian kingdoms, like the Indianized kingdom of Sri Vijaya and the Chinese Song Dynasty. Traders from these regions brought with them religion, culture, and political ideas. The Philippines was heavily influenced by these cultures, adopting Hindu-Buddhist and Islamic beliefs.

Spanish Colonization

In 1521, the explorer Ferdinand Magellan arrived in the Philippines and claimed the islands for Spain. This marked the start of over 300 years of Spanish rule. The Spanish brought with them Christianity and a new form of government. They built schools, roads, and hospitals, but they also imposed harsh laws and taxes.

American Rule and Independence

After the Spanish-American War in 1898, the Philippines became a territory of the United States. The U.S. introduced democratic governance and a new educational system. Then, on July 4, 1946, the Philippines gained independence, becoming a sovereign nation.

Post-Independence Era

Post-independence Philippines faced several challenges including political instability and economic issues. Ferdinand Marcos, who became president in 1965, declared martial law in 1972. This period, known as the Marcos Era, was marked by human rights abuses and corruption. Marcos was ousted in 1986 through the People Power Revolution, a peaceful protest that marked a significant moment in Philippine history.

Modern Day Philippines

Today, the Philippines is a democratic country with a growing economy. Despite facing issues like poverty and political corruption, it continues to progress. The country’s rich history and diverse culture are reflected in its traditions, festivals, and the warm spirit of its people.

In conclusion, the history of the Philippines is a story of resilience and adaptability. From its early inhabitants to the modern-day Filipinos, the country has navigated through periods of change and challenges, shaping it into the vibrant nation it is today.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Philippines Fun

- Essay on Philippines Culture

- Essay on Philippines Crimes

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

- AAS-in-Asia Conference July 9-11, 2024

Education About Asia: Online Archives

A brief essay on my key issues book: the philippines: from earliest times to the present.

My AAS Key Issues in Asian Studies book— The Philippines: From Earliest Times to the Present —is intended to introduce readers to a nation originally named after a European prince. The people of the archipelago that now constitutes the Philippines had a long history before any European contact occurred. Since the latter part of the nineteenth century, Filipinos have experienced a wide range of encounters with the US. The Philippines was Asia’s first republic and then became a US colony after an American war of conquest and pacification, which some argue resulted in the deaths of 10 percent of the population. Almost a million Filipino soldiers and civilians, and approximately 23,000 American military, died in the war against Imperial Japanese forces.

There are at least two ideas that drive this book. The first is that the Philippines was not some isolated archipelago that was accidentally “discovered” by Ferdinand Magellan in 1521. Some residents of the Philippines had contact with “the outside world” long before European contact through trade with other Southeast Asian polities and Imperial China.

The second and more important theme is that vibrant cultures existed before outsiders arrived, and they have continued throughout the history of the Philippines, though perhaps not seen or simply ignored by historians and other scholars. The intrusion by the Spaniards might be seen to have changed almost everything, as did the American incursion, and to a lesser extent the Japanese occupation. This is not the case. But if one does not know what was there before, the focus may be upon the intruders—their religion, culture, economies, and the impact they had on the local population—rather than on Filipinos, the local inhabitants. While acknowledging the impact and influence of foreign occupations, I sought in the book to focus on Filipinos and to see them as not merely, or even primarily, reactive.

Beginning with the pre-Hispanic period, The Philippines: From Earliest Times to the Present seeks to present, briefly, the reality of an advanced indigenous culture certainly influenced but not erased by more than three centuries of Spanish occupation. The second half of the nineteenth century saw the emergence on two levels—peasants and elite—of organized resistance to that presence, culminating in what some call a revolution and finally a republic. But this development was cut short by the Americans. When a commonwealth was put in place during the fourth decade of American rule, this was interrupted by World War II and the Japanese occupation. After World War II, the Philippines once again became an independent republic with the growing pains of a newly evolving democracy and its share of ups and down, including the Marcos dictatorship.

The Philippines has emerged in the twenty-first century with a robust and expanding economy, and as an important member of ASEAN. And it has its issues. On November 7, 2013, the most powerful Philippine typhoon on record hit the central part of the archipelago, resulting in more than 6,000 deaths. President Rodrigo Duterte, elected in 2016, has caught the eye of human rights advocates as he has dealt harshly with a drug problem that is far more significant than most realized. Then there is the ongoing conflict with China over islands in the South China Sea. The Philippines has been and will continue to be in the news.

The Philippines: From Earliest Times to the Present depicts Filipinos as not passive or merely the recipients of foreign influences. Contrary to the title of Stanley Karnow’s 1989 book, In Our Image: America’s Empire in the Philippines, the Philippines is not made in anyone’s, including America’s, image. Teachers and students should find this book helpful, not only in dealing with the history of the Philippines but also in recognizing that often the histories of developing countries fail to seriously take into account the local population—their culture, their actions, their vision of the world. The Philippines is perhaps best known today in the West as a place with beautiful beaches and as a wonderful place to vacation. This book will show it to be much more than that.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Latest News

- Join or Renew

- Education About Asia

- Education About Asia Articles

- Asia Shorts Book Series

- Asia Past & Present

- Key Issues in Asian Studies

- Journal of Asian Studies

- The Bibliography of Asian Studies

- AAS-Gale Fellowship

- Council Grants

- Book Prizes

- Graduate Student Paper Prizes

- Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies Award

- First Book Subvention Program

- External Grants & Fellowships

- AAS Career Center

- Asian Studies Programs & Centers

- Study Abroad Programs

- Language Database

- Conferences & Events

- #AsiaNow Blog

The Philippines: Historical Overview

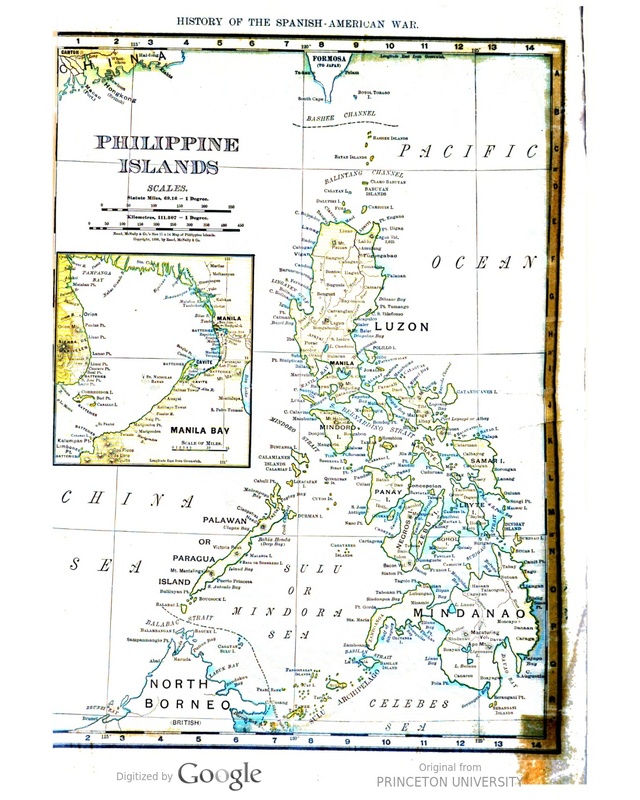

Map of the Philippines from 1898.

Source: History of the Spanish-American War , (New York: the Company, 1898), 2.

The Philippines is an archipelago made up of over 7,000 islands located in Southeast Asia. There are more than 175 ethnolinguistic groups, and over 100 dialects and languages spoken. One of the difficulties of writing a history of the Philippines is that prior to the arrival of the Spanish in the sixteenth century, the people that inhabited the archipelago did not see themselves as a unified political or cultural group. In fact, it was not until the late nineteenth century that a sense of a Philippine nation began to develop.

The first peoples to inhabit the Philippines migrated more than 4,000 years ago from what is today southern China. These peoples did not just populate the Philippines but dispersed throughout Southeast Asia. Historians and anthropologists have been able to trace their early migrations by examining linguistic patterns and have noted the Austronesian origin of most of the languages spoken in the precolonial Philippines and Southeast Asia. Indigenous languages spoken in Indonesia and Malaysia, for example, also share Austronesian roots.[1]

Early settlements of the Philippine archipelago occurred along rivers which kept populations somewhat isolated from one another. Rivers provided natural resources (water and protein via seafood) to sustain small communities. While these settlements were scattered along rivers, they did not develop a political center. Instead, early settlers saw themselves in relation to smaller communities and developed local alliances and allegiances. People were linked to one another through kinship, both biological and fictive, and followed a leader whom they called a datu. Datus emerged as protectors of the group. They used their skills in negotiation and warfare to demand tribute from merchants and maintain their clans. Eventually, these small communities ranging from 30 to 100 households became known as barangays, meaning “boat” in Tagalog, a Philippine language that originates in central Luzon.[2]

When Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan arrived in the archipelago, specifically to the Visayas region in 1521, he encountered a large network of barangays connected to a broader maritime world in Southeast Asia. Precolonial communities were in contact with other ethnolinguistic groups across the archipelago and beyond through trade and religious exchange. Goods such as rice, spices, aromatics, and other forest products attracted foreign merchants as far as India and China and richly rewarded the datus.[3] In terms of religion, historical evidence shows that precolonial Philippine peoples practiced “animism,” or beliefs and practices that held spirits as immanent to the surrounding world. These religious practices developed through trade networks, which also paved the way for the spread of Islam. Well before the arrival of Christianity, Islam reached the archipelago in the fourteenth century.[4]

It was the Spanish expedition led by Magellan in 1521 that laid the foundations for imagining a Spanish colony in the Philippines. Over the next 50 years, the Spanish crown sent more expeditions to the islands in search of spices and other goods. They named the islands after King Felipe II and aimed to have every datu follow him.[5] In 1565, Miguel Lopez de Legaspi arrived and brought the datu of Cebu in the Visayas to swear allegiance to the Spanish crown. His power over the region was insecure, however. Legaspi then gathered his followers and an army to travel to Maynilad (today known as Manila) to capture the port town from the son of a Luzon datu.[6]

Securing power over local settlements was a long and difficult process occurring over the next century that required both coaxing and coercion. By 1576, the Spanish created many settlements and the population of Spanish men in the region reached over 250.[7] One of their main challenges entailed bringing the indigenous people, who were still living in scattered settlements, under a centralized authority.

Bringing the indigenous population under Spanish rule took many decades of cajoling and relied on different tactics including developing alliances and enticing people through gifts and promises of salvation. Central to this process were the missionary friars who were a part of four main Catholic orders: Augustinians, Franciscans, Jesuits, and Dominicans. These missionary friars were sent to convert the native peoples to Christianity with the promise of Spain’s claim to the archipelago. According to historian John Phelan, “Christianization acted as a powerful instrument of societal control over the conquered people.”[8] Religious conversion through what was called conquista espiritual (“spiritual conquest”) became an important means to subjugate indigenous populations and also persuade them to relocate to political centers in order to facilitate a centralized Spanish rule.

The Spanish friars referred to the relocation process as reducción. As much as reducción was a process of religious conversion, it was also a militarized endeavor that involved violence when the so-called “indios” resisted.[9] A century after the Spanish Reconquista, wherein the Spanish reconquered the Iberian peninsula from Muslim rule, Spanish friars in the Philippines viewed their missionary duty as a continuation of an earlier struggle. The growing presence of Islam in the southern islands of the archipelago proved that the Spanish were destined to provide the natives salvation. They called converts to Islam “Moros” after the Moors they fought in Spain, which discursively connected their religious mission to their previous war of conquest.

Once areas were under Spanish control, the colonial government established an encomienda system that required the local population to pay tribute and perform labor for the colony.[10] A Spanish governor, who was also a military captain, effectively had the power to make decisions for the colony. This was due to the fact that the Philippine islands were so far away from the metropole. Yet, the governor’s power was still limited. The fact that he was also a military captain signals how, even after 300 years of rule, the Spanish never fully had control over the local population and therefore depended on military leadership [11]. Under the governor, provinces were established with a gobernadorcillo ruling each town. The gobernadorcillo enforced the law established by the colonial governor. Under the gobernadorcillo was the cabeza de barangay or the head of barangay who collected taxes locally. At times, the gobernadorcillo and the cabeza de barangay used force to obtain the funds they required from the local people. The Spanish colonial government depended on the collection of tribute to maintain their operations and control the Philippine population.

By the 1850s, the economic prosperity of the native-born population, especially of Chinese mestizos, began to develop into an elite class that rivaled the peninsulares, or the “pure blooded” Spanish in the archipelago (also sometimes known as criollos). By the 1870s, this new elite sent their sons to Manila and Europe for a liberal education and they became known as ilustrados, or “enlightened ones.”[12] Ilustrados began to question the authority of the Spanish friars and publicly critique the poor administration of the Philippine colony. It was this group of elite men that established the Propaganda Movement, based in Manila and Spain, calling for reforms centered on equality between Filipinos, mestizos, and the Spanish.[13] The writings of propagandists, especially that of Jose Rizal, the most famous of the group, inspired the Filipino masses. The views of the majority, however, diverged from those of the elites who advocated mainly for modest reform and representation. The politics of the elite was ultimately considered too moderate from the perspective of a majority who became inspired to revolt against Spain and fight for independence. In 1896, the Philippine revolution began as a radical fight for emancipation from Spanish colonialism and the right to Filipino self-governance.[14]

In 1898, a major event on the other side of the globe stymied the efforts of the Filipino revolutionaries. In April of 1898, the US sent the battleship USS Maine to Havana Harbor, Cuba, in support of Cuban revolutionaries. When the ship exploded killing over 200 Americans, the US government assumed the Spanish were responsible and used the event as a pretext for war. US president William McKinley declared war with Spain in August of 1898, and US troops were shipped to the remaining Spanish possessions, including the Philippines, just two days later.[15] The Filipino revolutionaries could not have predicted such a turn of events that would ultimately affect the outcome of their fight for an independent Philippines.

By the time the American military arrived in April of 1898, the Filipino revolutionaries had successfully gained control over all major cities in the archipelago except for the capital city of Manila. There, the Spanish were protected by a fortress constructed for military protection against outside invaders called Intramuros. Knowing that they were losing the war against the Filipinos, Spanish and US military officers pre-arranged a battle in Manila which excluded Filipino soldiers in order to stage the Spanish defeat. The Spanish orchestrated a mock battle in order to save face and lose the war to the Americans rather than to the Filipinos, whom they believed to be an inferior race.[16] The 1898 Treaty of Paris ended the Spanish-American War and officially transferred ownership of Spain’s remaining colonies to the US.[17]

Filipino revolutionaries continued their fight for independence against the US in the Philippine-American war. Over the next several decades of US rule, the US military and colonial officials attempted to establish control, pacify the local populations, and justify US imperialism in the Philippines. This is where our exhibit begins.

[1] Patricio N. Abinales and Donna J. Amoroso, State and Society in the Philippines, (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2005), 20.

[2] Patricio N. Abinales and Donna J. Amoroso, State and Society in the Philippines, 27.

[3] Patricio N. Abinales and Donna J. Amoroso, State and Society in the Philippines, 23.

[4] James Francis Warren, The Sulu Zone, 1768-1898: The Dynamics of External Trade, Slavery, and Ethnicity in the Transformation of a Southeast Asian Maritime State, (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1981).

[5] José S. Arcilla, An Introduction to Philippine History, (Manila: Ateneo Publications, 1971), 11.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Patricio N. Abinales and Donna J. Amoroso, State and Society in the Philippines, 53.

[8] John Leddy Phelan, The Hispanization of the Philippines: Spanish Aims and Filipino Responses, 1565-1700, (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1959), 93.

[9] John Leddy Phelan, The Hispanization of the Philippines, 44-45.

[10] John Leddy Phelan, The Hispanization of the Philippines, 95.

[11] José S. Arcilla, An Introduction to Philippine History, 28.

[12] Edgar Wickberg, The Chinese in Philippine Life, 1850-1898, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965).

[13] John N. Schumacher, The Propaganda Movement, 1880-1895: The Creators of a Filipino Consciousness, the Makers of Revolution, (Manila: Solidaridad Pub. House, 1973).

[14] Patricio N. Abinales and Donna J. Amoroso, State and Society in the Philippines, 104.

[15] Paul Kramer, The Blood of Government: Race, Empire, the United States, and the Philippines, (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 78.

[16] Paul Kramer, The Blood of Government, 90.

8 Amazing Facts About Philippine History You Never Learned in School

There’s more to learn in Philippine history beyond Jose Rizal and Andres Bonifacio . Sadly, history is so vast a subject that it’s nearly impossible to know everything during our brief high school stay.

Here are eight astonishing trivia that your Philippine history teachers might have missed.

Table of Contents

8. there were three other martyr priests aside from “gomburza”.

The words “martyr priest” usually conjure images of the “Gomburza,” an amalgam of the names of three Filipino priests who were executed for their alleged involvement in the 1872 Cavite Mutiny.

But several years after their deaths, another three martyr priests would again shed their blood in Bagumbayan. Their names are much more obscure, though, mainly because they were part of a group of Bicolano martyrs collectively known as Los Quince Martires .

After discovering Katipunan in September 1896, the Spanish government immediately ordered mass arrests of those connected to the secret organization. The wrath of the Spaniards eventually reached Bicol, and arrests were made between September and October 1896.

A total of 15 men were arrested, tortured, and sentenced to death. Of these 15, three were secular priests from Nueva Caceres (now Naga City): Fr. Severino Diaz, Fr. Inocencio Herrera, and Fr. Gabriel Prieto .

Fr. Severino Diaz y Lanuza was the first secular priest to head the Cathedral of Nueva Caceres. Fr. Innocencio Herrera, on the other hand, was a native of Pateros in Rizal. He moved to Bicol and became a secular priest and choirmaster at the Cathedral under Diaz. Both priests were arrested on September 19, 1896, and suffered grave torture thereafter.

The third priest, Fr. Gabriel Prieto y Antonio, was implicated when his brother, Tomas, was forced to give up names under severe torture. He was arrested at the parish house in Malinao, Albay, on September 22, 1896, under the orders of then Albay Civil Governor Angel Bascaran. Like the other two priests, he also suffered verbal and physical torture after his arrest.

Bound in ropes and chains, the three priests and other prisoners were transferred to Manila aboard the steamships Ysarog and Montañes. They were temporarily imprisoned in the convent of San Agustin in Intramuros before being transferred to the Bilibid Prison, where they would stay until their execution by firing squad on January 4, 1897.

7. The First American Hero of World War II Was Killed in Combat in the Philippines

A graduate of West Point, 25-year-old Capt. Colin P. Kelly Jr. became the first American hero of World War II when he bombed a Japanese cruiser three days after the attacks in Pearl Harbor.

On December 10, 1941, Kelly and his crew were ordered to fly out of Clark Air Field and attack targets on Formosa (now Taiwan). He was forced to take off the B-17 with only three 600-pound bombs, and the plane partly fueled.

On the way to Formosa, they saw a huge Japanese landing party with accompanying destroyers. Kelly ordered the attack on the Japanese fleet despite receiving no clear permission from the base to engage the enemy.

The crew dropped the bombs from 20,000 feet. One bomb directly hit the target while the other two impacted the flank. With no bombs left, Kelly maneuvered the plane to return to Clark Air Field.

Unfortunately, the plane was almost back to its home airfield when two enemy planes attacked it. Kelly ordered his crew of six to bail out while he remained in the plane until it exploded.

After his death, it was discovered that Kelly’s bomber had hit a light Japanese cruiser named Ashiraga, not the battleship Haruna as earlier reports had suggested. For this reason, Gen. Douglas MacArthur lowered the recommendation to the Distinguished Service Cross.

To honor his heroism, a post office and a highway in his hometown in Florida were named after him.

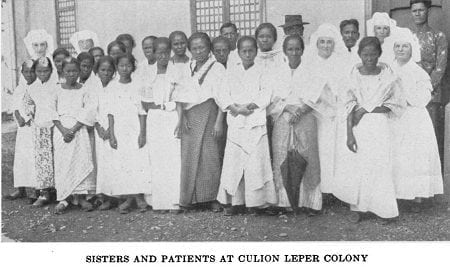

6. Philippines’ Leper Colony Had Its Own “Leper Money”

Leprosy is a communicable bacterial disease characterized by skin lesions and numbness. In 1633, it was said that a Japanese Emperor sent a ship loaded with lepers to the Spanish missionaries based in the Philippines. He also instructed the ship’s captain to drown the lepers in case no one would receive them.

Fortunately, the missionaries kindly welcomed the patients with open arms and even established the San Lazaro Hospital to care for them. At that time, people had very little knowledge about the disease, so it didn’t take long before leprosy started to afflict the Filipino populace.

In 1906, the Director of Health for the Philippines, Dr. Heiser, opened a leper colony in Culion, an island located north of Palawan. Lest they might continue spreading the disease, a unique monetary system separate from the rest of the country was established. These leper coins were only allowed within the colony, and those who would leave the place had to convert the leper money into “government money.”

Leper money was strictly regulated, and those who violated the law would pay a fine, stay in prison for up to 1 month, or both.

The first few issues of the leper coins were made from aluminum, but it was later replaced by copper nickel as those made from aluminum were easily damaged by chemicals used to disinfect the coins.

5. Before Martial Law, There Was the Colgante Bridge Tragedy

On September 16, 1972, a few days before the declaration of martial law, the Colgante bridge in Naga City collapsed, killing 114 Roman Catholic pilgrims celebrating the feast of their patroness, Nuestra Señora de Peñafrancia .

Most of the victims were either drowned or crushed to death on boats beneath. The tragic incident happened when 1,000 faithful rushed to the 15-year-old Bailey bridge to watch with excitement the fluvial procession that would bring the image of their patroness from Naga Metropolitan Cathedral to her shrine.

Several broadcast journalists covering the event also perished in the tragedy. One of them is Miss Mila Obia, who was announcing the approach of the religious image using her local dialect when the bridge suddenly collapsed.

Incidentally, this was the second time the bridge claimed many lives during a fluvial procession. In 1948, the old Colgante bridge–which was only a suspension type back then–fell into the river and left 30 people dead.

4. President Elpidio Quirino Helped Save the Lives of Almost 6,000 “White Russians”

If President Quezon was the savior of the Holocaust Jews , President Quirino should be the unsung hero of “White Russians.”

In 1948, China was on the brink of a total invasion by the Communists led by Mao-Tse-Tung. For this reason, Russian emigrants living in Peking, Hankow, Tiensin, and other nearby cities in northern China were forced to evacuate to Shanghai. However, they were aware that the Communist army would eventually take over the rest of China, so they had to move somewhere else or end up dying in Russian labor camps.

This is when the International Refugee Organization (IRO) came to the rescue. They knew the danger that might ensue, so they asked for help from other countries to provide temporary shelter for the “White Russians.”

These “White Russians” were named after the color of the tsarist court and the Russian soldiers’ uniforms. If you can recall your world history, the “White Russians” were opposed to the Communist regime (i.e., the “Red Russians”) who went against the Tsar during the 1917 Bolshevik revolution. The conflict resulted in a civil war, forcing the White Russians to transfer to other countries, including China.

Also Read: The Forgotten Story of Japanese Christians – Philippines’ First Refugees

Going back to IRO, no country had responded to their plea for fear of China. They were about to lose hope when the Philippines under President Elpidio Quirino agreed to convert the tiny island of Tubahao in Eastern Samar into a Russian refugee camp. In 1949, about 5,000 to 6,000 White Russians finally arrived and settled in Tubahao for about 27 months.

The Russian Refugee Camp was divided into 14 districts, and the White Russians who stayed there had their hospital, electricity, churches, and a cemetery. After more than two years on the island, most of the refugees were eventually admitted to other countries like France, Australia, and the United States.

To honor Quirino’s act, a Russian sculptor made a bronze artwork featuring the late Philippine president being blessed by St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco. It was unveiled in 2011 in the Philippine Trade Training Center lobby in Pasay City.

3. In 1942, Almost 16 Million Silver Coins Were Dumped Near Corregidor. Some of It Remains Unretrieved

After the Fall of Manila in 1942, Filipino and American officials were thinking of ways to keep the Philippine National Treasury out of the enemy’s hands. At that time, the treasury was brimming with 70 million pesos in paper bills, 269 pieces of gold bars, and 16,422,000 pesos in silver coins.

They were running out of time, so they had to move fast. After recording the serial numbers, 20 million in 500-peso bills were burned from January 19 to 20, 1942. When the submarine U.S.S. Trout arrived in Corregidor on February 3, workers loaded it with 2 million dollars in gold bars and $360,000 in silver, eventually shipped to San Francisco.

With no more time left, high court government officials dumped the remaining 15,792,000 pesos in silver coins to Caballo Bay, a deep and rough location just off Corregidor.

For some reason, the Japanese learned about the sunken treasure right after the fall of Corregidor. Soon, they sought the help of Filipino divers–some of whom died due to drowning–to salvage the boxes of silver coins. Ultimately, they only recovered $54,000 or 100,000 pesos.

But the Japanese wouldn’t settle for less, so they handpicked more experienced divers from a group of American prisoners. From June 20 to September 28, 1942, the American divers retrieved 150,000 pesos. Of course, it was hazardous work, and they thought of only one way to retaliate: outsmarting the Japanese.

Indeed, they could steal 30,000 to 60,000 pesos without the Japanese knowing. Their Filipino friends found Chinese money changers in Manila to exchange Japanese paper currency for Philippine silver coins. Some coins were also passed off to other prisoners of war who would later use the money to bribe Japanese soldiers.

Eventually, the recovery program was canceled, much to the joy of American prisoners. In 1945, the U.S. Navy salvaged 5,380,000 pesos which they turned over to the Philippine government.

Although 75% of the sunken treasure was already recovered, no one knows precisely how much of it remains at the bottom or if it can still be retrieved in the first place.

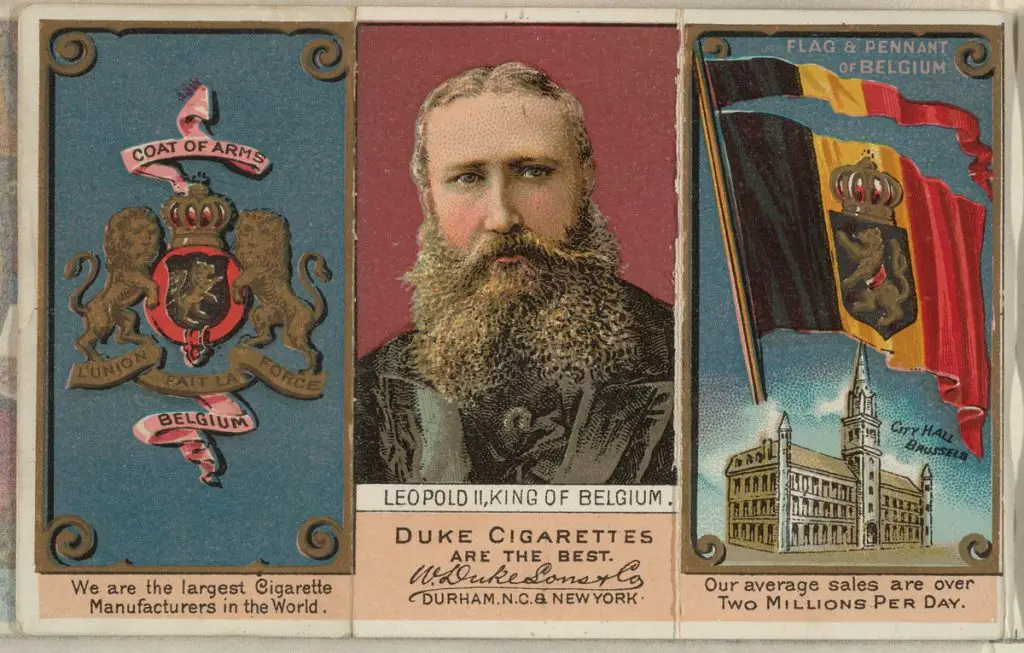

2. A Belgian King Almost Bought the Philippines From Spain

King Leopold II of Belgium was passionate about geography and everything that had something to do with maps. He also loved to travel, and during one of his trips, he realized that he could turn Belgium into one of the world’s wealthiest countries.

To make this possible, he first needed a colony. His focus then shifted to Asia, specifically the islands considered to be the gateway to other nearby countries: the Philippines.

According to historian Ambeth Ocampo, most details of King Leopold’s quest to make the Philippines a Belgian colony can be found in the 1962 book A La Recherde d’un Etat Independent: Leopold II et les Philippines 1869-1875.

In 1866, a year after he acceded to the throne, King Leopold II asked his ambassador in Madrid to negotiate with the Queen of Spain about possibly ceding the Philippines to Belgium.

But here’s the catch: It was common knowledge then that Leopold’s government was against his imperialistic plans. They believed colonization “entails naval vessels and an army to protect interests halfway across the world,” and Belgium was not yet ready to take that risk.

As expected, his first attempt failed. And so was the second when he even attempted to get personal loans from English banks, which ended in rejection.

He also devised a scheme to turn the Philippines into an independent country and later a colony under the Belgian monarch. Unfortunately, this, too, failed miserably.

Ultimately, his dream of having a colony finally came true when he proclaimed his sovereignty over Congo, an African country.

1. A Filipino Dwarf Became a Famous Figure in 19th-Century Britain

Don Santiago de los Santos, a Filipino dwarf , became part of a traveling show in England between the late 1820s and the early 1830s. He was a local celebrity in that part of the world.

So, how did he end up in England?

Popular journals from the late Georgian and Victorian eras had documented his story, although they might have exaggerated some of the details to sell more copies.

The existing documents suggest that Don Santiago de los Santos was born in 1786 to poor parents. The 1836 edition of the Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction (Volume 28) went on to say that he is

“….a native of the Spanish settlement of Manila; in one of the forests of which, it seems, he was exposed to death in his infancy, on account of his diminutive size. He, was, however, miraculously saved by the Viceroy, who, happening to be hunting in that quarter, humanely ordered him to be taken care of and nursed with the same tenderness as his own children, with whom the little creature was brought up and educated, until he attained the age of manhood.”

Sadly, the Viceroy died when he was 20 years old. His foster brothers and sisters moved to Spain shortly thereafter, while Santiago decided to stay because of his “attachment to the land of his birth.”

That decision proved to be futile. Neglected by his own family, he “found his way to Madras, and was brought to England by the captain of a trading vessel.”

The journal also reveals some of Don Santiago’s unique characteristics. He was described as “stoutly built” with “slight copper” complexion. He also liked “glittering attire, jewellery, and silver plate.” And just like Jose Rizal, Don Santiago was also multilingual: He could speak his native tongue and Indian patois, Portuguese, and English.

He later married Anne Hopkins, a 29-year-old dwarf from Birmingham slightly taller than him (she was thirty-eight inches tall while Don Santiago was only twenty-five inches high). However, they faced a minor hurdle before they could tie the knot. According to the 1848 edition of The London Lancet,

“..a protestant clergyman hesitated to marry them, on the presumption that it was contrary to the canon law, as being the means of propagating a race of dwarfs; but in this he was overruled by the high bailiff of Birmingham, and some legal opinions.”

They were finally married on July 6, 1834, at two separate churches in Birmingham (Santiago was a Roman Catholic while his wife was a Protestant).

Anne Hopkins eventually gave birth to a child, but it was not a happy ending:

“…the infant, though it came to the world alive, did not survive its birth above an hour. Its length is thirteen inches and a half; its weight is one pound four ounces and a half, (avoirdupois;) it is in every respect well formed; and the likeness of its face to that of the father is very striking.”

Barrameda, J. (2012). The Bicol Martyrs of 1896 revisited . Bicol Mail . Retrieved 2 October 2015

Cheng, J. (1960). Silver Coins Buried Under The Sea. The Quan , p. 3.

Davies, H. (1848). On Account Of Two Labours Of A Dwarf, With Some Observations On The Operation Of Craniotomy, And On The Induction Of Premature Labour. The London Lancet: A Journal Of British And Foreign Medical And Chemical Science, Criticism, Literature And News , 8 , 31-32.

Garvey, J. (2007). San Francisco in World War II (p. 26). Arcadia Publishing.

Hubbell, J. The Great Manila Bay Silver Operation . Corregidor.org . Retrieved 2 October 2015

Labro, V. (2011). ‘White Russians’ return to refugee island . Inquirer.net . Retrieved 2 October 2015

Limbird, J. (1836). J. Limbird. The Mirror Of Literature, Amusement, And Instruction , 28 , 295.

Lodi News Sentinel,. (1972). Bridge Collapse Kills Catholics, p. 13.

The Milwaukee Journal,. (1941). Heroes of the Philippines Honored By MacArthur, p. 3.

Wheeler, M. (1913). The Culion Leper Colony. The American Journal Of Nursing , 13 , 663-665.

Written by Luisito Batongbakal Jr.

in Facts & Figures , History & Culture

Last Updated April 9, 2023 11:02 AM

Luisito Batongbakal Jr.

Luisito E. Batongbakal Jr. is the founder, editor, and chief content strategist of FilipiKnow, a leading online portal for free educational, Filipino-centric content. His curiosity and passion for learning have helped millions of Filipinos around the world get access to free insightful and practical information at the touch of their fingertips. With him at the helm, FilipiKnow has won numerous awards including the Top 10 Emerging Influential Blogs 2013, the 2015 Globe Tatt Awards, and the 2015 Philippine Bloggys Awards.

Browse all articles written by Luisito Batongbakal Jr.

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net

- Borrow, Renew, Request How to borrow materials, request pdf scans, and interlibrary loans .

- Study Spaces Areas for individual and group study and how to reserve them.

- Course Reserves How to access course-related materials reserved by faculty for their students.

- Services for Faculty and Instructors A list of services offered to faculty and instructors at the University of Hawaii at Manoa.

- Library Instruction Request library instruction for your course or register for a workshop.

- Suggest a Purchase Suggest new materials that support teaching, study, or research.

- Other Services Apply for a research carrel or reserve our lactation room.

- Loanable Technology Cables, adaptors, audio and video equipment, and other devices

- Collections An overview of the various library collections.

- Online Databases Search across 100s of library databases.

- Journals Search journals by title or subject.

- Research Guides Guides for subjects, select courses, and general information.

- OneSearch Finds books and other materials in the UH Manoa Library's collection.

- Scholarly Communication Learn about scholarly communication, open access, and our institutional repositories ScholarSpace , eVols , and the UH System Repository .

- Ask a Librarian Get help by email, online form, or phone.

- FAQ Frequently asked questions.

- Accessibility and Disability Information about accessibility and disability.

- Subject Librarians Find a librarian for a specific subject.

- Copyright Help Links to resources about copyright.

- Technology in the Library Wireless access, scanning, printing.

- English 100 Students The starting point for English 100 research.

- Request a Research Appointment Contact us to schedule an in-person appointment.

- Office and Department Contacts View a list of the departments at the library.

- Jobs at the Library Faculty, staff, and student job opportunities.

- Staff Directory Contact information for staff at the library.

- Exhibits Current and past exhibits at the library.

- Support the Library Find out how you can support the library.

- Our Library Annual reports, mission, values, history, and policies.

- Visiting Hours, directions, floor plans

- News, Blogs & Events News, blogs & events from the library.

Philippines: Philippine History

- Architecture

- Martial Arts

Philippine History

- Costumes & Fashion

- Performing Arts

- Sculptures & Paintings

- Food by Region

- Cebuano Language, Literature, History, Arts & Culture

- Human Trafficking

- Marine Ecology & The Environment

- Jose S. Libornio

- Bataan Death March

- HIST 296 ("WWII and Its Legacies in Asia/Pacific")

- Indigenous Peoples of Luzon/The Cordilleras

- The Ilokanos

- The Tagalogs

- Indigenous Peoples in Mindanao

- Mindanao Politics and History

- Islam in the Philippines

- Philippine Boats & Navigation

- Colonial Mentality

- Reference Materials

- Ramon Sison Collection

- Dissertations

- Digital Archives

- U.S. Government Documents on the Philippines

Agoncillo, T. (1962). Philippine history. Inang Wika Pub. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma995179914605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .A34

Arcilla, J. (1973). An introduction to Philippine history (2d ed., enl.). Ateneo de Manila University Press. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma998405584605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .A82 1973

Women’s role in Philippine history : selected essays. (1996). https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9917408334605682

Location: Hamilton Asia HQ1757 .C66 1996

Zaide, G. (1951). Great events in Philippine history : patriotic calendar . M. Colcol. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma995179894605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS667 .Z3

Looney, D. (1977). A beginner’s guide to Philippine history books . Friends of the Filipino People. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma995180024605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .L66

De la Costa, H. (1965). Readings in Philippine history : selected historical texts presented with a commentary . Bookmark. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma998348874605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .C6

Abeto, I. (1989). Philippine history reassessed : a collection of undiscovered historical facts from prehistoric time to 1872 . Integrated Pub. House. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9915965084605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .A24 1989

Scott, W., & Scott, W. (1984). Prehispanic source materials for the study of Philippine history (Rev. ed.). New Day Publishers. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9914729264605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS673.8 .S36 1984

Scott, W. (1982). Cracks in the parchment curtain and other essays in Philippine history . New Day Publishers. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9913659044605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .S366

Scott, W. (1992). Looking for the prehispanic Filipino and other essays in Philippine history . New Day Publishers. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9916747444605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS673.8 .S355 1992

Scott, W. (1968). A critical study of the prehispanic source materials for the study of Philippine history. University of Santo Tomas Press. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma999685544605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668.A2 S36

Gagelonia, P. (1970). Concise Philippine history. Far Eastern University Consumers Cooperative Incorporation. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9910091030505681

Print available through LCC

Zafra, N. (1967). Philippine history through selected sources. Alemar-Phoenix Pub. House. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma999685634605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .Z273

Valencia, E. (2002). Trade & Philippine history & other exercises. Giraffe Books. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9921935834605682

Location: Hamilton Asia HC453 .V35 2002 v.2

Bernal, R. (1967). Prologue to Philippine history. Solidaridad Pub. House. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma995180204605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS669 .B47

De la Costa, H., & Jesswani, P. (1989). A Look at Philippine history. St. Paul Press. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma995873454605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .L658 1989

Sánchez-Arcilla Bernal, J. (1990). Recent Philippine history, 1898-1960 . Office of Research and Publications, Ateneo de Manila University. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9916211104605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS685 .S265 1990

Zaide, G. (1938). Philippine history and government. S. E. Macaraig co. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma991508434605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS676 .Z3

Prominent caviteños in Philippine history. (1941). Atty. Eleuterio P. Fojas. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma996232564605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS688.C38 P96 1941

Alejandro, R., Vallejo, R., & Santiago, A. (2000). Selyo : Philippine history in postage stamps. Published and exclusively distributed by National Book Store, Inc. and Anvil Pub. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9920966844605682

Location: Hamilton Asia HE7265 .A43 2000

Bernad, M. (1983). Tradition & discontinuity : essays on Philippine history & culture. National Book Store. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9913857054605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .B456 1983

Wickberg, E., Wei, A., & Wu, W. (2001). The Chinese mestizo in Philippine history. Kaisa Para sa Kaunlaran. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9921693624605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS666.C5 W53 2001

Quirino, C. (1995). Who’s who in Philippine history. Tahanan Books. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9910320113705681

Print available through Kauai Community College

Dery, Luis Camara. When the World Loved the Filipinos and Other Essays on Philippine History. España, Manila: UST Pub. House, 2005. Print. / https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9926868854605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS669 .D47 2005

Anderson, Gerald H. Studies in Philippine Church History. Ithaca [N.Y: Cornell University Press, 1969. Print. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9912038704605682

Location: Hamilton Asia BR1260 .A5

Zaide, Gregorio F. The Pageant of Philippine History : Political, Economic, and Socio-Cultural. Manila, Philippines: Philippine Education Co., 1979. Print. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma998680134605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .Z288

Trillana, Pablo S. The Loves of Rizal and Other Essays on Philippine History, Art, and Public Policy. Quezon City, Philippines: New Day Publishers, 2000. Print. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9921091674605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS675.8.R5 T74 2000

Bohol, E. (1948). Outline on Philippine history for the fourth year high school. Bohol Junior Colleg. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma995179974605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .B8 1948

Soliven, P. (1999). Half a millennium of Philippine history : snippets of what we were-- snatches of what we ought to be. Phil. Star Daily, Inc. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9920391134605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS655 .S65 1999

Bulletin of Philippine folklore & local history. (1981). Cebuano Studies Center of the University of San Carlos. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9919428124605682

Location: Hamilton Asia (Library Use Only) DS651 .B84

McCoy, A., & De Jesus, E. (1982). Philippine social history : global trade and local transformations. Ateneo de Manila University Press. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9911802664605682

Location: Hamilton Asia HN713 .P52 1982

Fernandez, D. (1996). Palabas : essays on Philippine theater history. Ateneo de Manila University Press. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9918558194605682

Location: Hamilton Asia PN2911 .F36 1996

Kalaw, T. (1969). The Philippine revolution. Jorge B. Vargas Filipiniana Foundation. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma995181134605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS676 .K3 1969

Taylor, J. (1971). The Philippine Insurrection against the United States; a compilation of documents with notes and introduction. Eugenio Lopez Foundation. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9918622934605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS676 .T38 1971

Zaide, G. (1957). Philippine political and cultural history (Rev. ed.). Philippine Education Co. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma992202714605682

Location: Hamilton DS668 .Z32 1957

Agoncillo, T. (1974). Introduction to Filipino history. Radiant Star Pub. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma999968264605682

Gagelonia, P. (1977). Filipino nation : history and government. National Book Store. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma998661564605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .G26

Hornedo, F. (2001). Ideas and ideals: essays in Filipino cognitive history. University of Santo Tomas Pub. House. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9921663694605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS664 .H65 2001

Marcos, F. (1976). Tadhana: The history of the Filipino people. [Publisher not identified]. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9911735624605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .M37

Root, M. (1997). Filipino Americans : transformation and identity. Sage Publications. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9919145254605682

Location: Hamilton Main E184.F4 F385 1997

Dery, L. (2006). Pestilence in the Philippines : a social history of the Filipino people, 1571-1800 . New Day Publishers. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9928888094605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS663 .D47 2006

Philippine History (Continuation)

Batacan, D. (1972). The Supreme Court in Philippine history; from Arellano to Concepcion. Central Lawbook Pub. Co.; [distributed by Central Book Supply, Manila. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma998953074605682

Location: Hamilton Asia KQH .P6 B37

Ileto, R. (2018). Knowledge and pacification : on the U.S. conquest and the writing of Philippine history . Ateneo de Manila University Press. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9949874814605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS682 .A184 2017

Zaide, G. (1939). Philippine history and civilization. Philippine associated publishers. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma995181154605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS676 .Z25

Diaz, C. (2009). The other Philippine history textbook. Anvil. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9932768274605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .D52 2009

Jose, R. (2006). Recent studies in Philippine history. College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9932306234605682

Location: Hamilton Asia (Library Use Only) H1 .P537 v.57

Benitez, C. (1928). Philippine history in stories. Ginn and company. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma991508274605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .B4

Engel, F. (1979). Philippine history : a brief digest (2nd ed.). [Publisher not identified]. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9911330244605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .E53 1979

Zaide, G. (1937). Early Philippine history and culture. G.F. Zaide. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma999277334605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .Z23

Zafra, N. (1956). Readings in Philippine history (New ed.). University of the Philippines. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma995180094605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .Z28 1956

Zaide, G., & Zaide, S. (1990). Documentary sources of Philippine history. National Book Store. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9916188534605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .D6 1990

Miravite, R. (1967). Books on Philippine history . [publisher not identified]. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma996857894605682

Location: Hamilton Asia Z3298.A4 M53

IBON Teacher’s manual on Philippine history. (2nd ed.). (1981). IBON Data Bank Phils. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma999892824605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS669 .I244 1981

Torres, J. (2000). Pananaw : viewing points on Philippine history and culture. UST Pub. House. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9921387604605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS663 .T67 2000

Ocampo, A., Peralta, J., & Rodriguez, F. (2012). The diorama experience of Philippine history. Ayala Museum. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9941650394605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .O23 2004

Rasul, J. (n.d.). Philippine history : from thousand years before Magellan. [Publisher not identified]. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9931273854605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS655 .R37 2008

Gagelonia, P. (1970). The Filipino historian (controversial issues in Philippine history). FEUCCI. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma995180234605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS669 .G33

Abinales, P. (2010). The “Local” in Philippine National History: Some Puzzles, Problems and Options. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9910993006405681

Location: Hamilton Asia DS674 .S76 2013

De Viana, Augusto V. Stories Rarely Told : the Hidden Stories and Essays on Philippine History . Quezon City: New Day Publishers, 2013. Print. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9946341294605682

Owen, Nrman G. Trends and Directions of Research on Philippine History, an Informal Essay. Place of publication not identified: Publisher not identified, 1975. Print. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma995180254605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS669 .O94

Joaquin, N. (1977). A question of heroes : essays in criticism on ten key figures of Philippine history. Ayala Museum. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma998474024605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS653.7 .J63

Scott, W. (1968). A critical study of the prehispanic source materials for the study of Philippine history. Thesis--University of Santo Tomas. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma99512344605682

Location: Hamilton Asia (Library Use Only) MICROFICHE 187

Barrientos, V. (1998). A finding guide to the picture collection of the Filipiniana Division. Part IV, Heroes in Philippine history. Special Collections Section, Filipiniana Division, The National Library. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9920366764605682

Location: Hamilton Asia Reference (Library Use Only) Z3299 .N38 1998

Alip, E. (1958). Philippine history: political, social, economic; based on the course of study of the Bureau of Public Schools. (7th rev. ed). Alip & Sons. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma995179924605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .A4 1958

Mastura, M. (1979). The rulers of Magindanao in modern history, 1515-1903 : continuity and change in a traditional realm in the southern Philippines. Publisher not identified]. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma999183994605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS666.M23 M37 1979a

Lumbera, B., & Lumbera, C. (1997). Philippine literature : a history & anthology (Rev. ed.). Anvil. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9926072204605682

Location: Hamilton Asia PL5530 .P44 1997

Outline of Philippine history and government, based on the course of study and includes all changes before and after World War II. (Rev. ed.). (1950). Philippine Book Co. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma991508294605682

Location: Hamilton DS670 .O88 1949

Voices, a Filipino American oral history. (1984). Filipino Oral History Project. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9911221724605682

Location: Hamilton Main F870.F4 V65 1984

Gorospe, O. (1933). Making Filipino history in Hawaii. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma997879204605682

Location: Hamilton Hawaiian (Library Use Only) DU620 .M5 v.45 p.241-253

Rafael, V. (2000). White love and other events in Filipino history. Ateneo de Manila University Press. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9922646264605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS685 .R24 2000b

Filipino-American history. (2008). Language, Literature & History Section, Hawaiʻi State Library, Hawaii State Public Library System. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9931245804605682

Location: Hamilton Hawaiian (Library Use Only) IN CATALOGING 3124580

Bautista, V. (2002). The Filipino Americans: (1763-present) : their history, culture, and traditions (2nd ed.). Bookhaus Pub. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9923164014605682

Location: Hamilton Main E184.F4 B38 2002

Okamura, J. (1991). Filipino organizations: a history. Operation Manong. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma995894474605682

Location: Hamilton Hawaiian (Library Use Only) DU624.7.F4 O42 1991

Agoncillo, T., & Guerrero, M. (1973). History of the Filipino people ([4th ed.]). R.P. Garcia. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9919225084605682

Location: Hamilton Main DS668 .A32 1973

Tubangui, H. (1982). The Filipino nation : a concise history of the Philippines. Grolier International. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9913647534605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .F5 1982

Batacan, D. (1966). The laughter of my people: a history of the Filipino people written a smile. Printed by MDB Pfint. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma995180194605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS669 .B38

Craig, A., Mabini, A., & Rizal, J. (1973). The Filipinos’ fight for freedom; true history of the Filipino people during their 400 years’ struggle. AMS Press. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9912137304605682

Location: Hamilton Asia DS668 .C69 1973

Measham, F. (2016). The secret history of Filipino women. Lifted Brow, The, 29, 49–52. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/1rbop20/informit901765406961917

Location: ILL through unspecified college

San Juan, E. (1989). MAKING FILIPINO HISTORY IN A “DAMAGED CULTURE.” Philippine Sociological Review, 37(1/2), 1–11. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/1rbop20/jstor_archive_1241853640

Location: Hamilton Asia (Library Use Only) DS651 .P462 // Also through JSTOR

Online - Ebook

Nagano, Y. (2006). Transcultural Battlefield: Recent Japanese Translations of Philippine History. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/68t5m5h0 https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/1rbop20/cdl_soai_escholarship_org_ark_13030_qt68t5m5h0

Link: Through escholarship UCLA https://escholarship.org/uc/item/68t5m5h0

Project Muse: https://muse-jhu-edu.eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/journal/531

Journal title: Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints

Aquino, B. (2006). From Plantation Camp to Global Village:100 Years of Filipino History in Hawaii. Honolulu, Hawaii: Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawaii at Manoa. https://uhawaii-manoa.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UHAWAII_MANOA/11uc19p/alma9910995904405681

Link: Through UH Scholarspace http://hdl.handle.net/10125/15379

Databases - Scholarly Works/Articles

Database: Historical Abstracts

Serizawa, T. (2019). Translating Philippine history in America’s shadow: Japanese reflections on the past and present during the Vietnam War. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 50(2), 222–245. https://doi-org.eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/10.1017/S0022463419000274

Database: Business Source Complete

Reyes, P. L. (2018). Claiming History: Memoirs of the Struggle against Ferdinand Marcos’s Martial Law Regime in the Philippines. SOJOURN: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia, 33(2), 457–498. https://doi-org.eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/10.1355/sj33-2q

Database: Points of View Reference Center

Republic of the Philippines. (2003). In Background Notes on Countries of the World 2003 (pp. 1–15). http://eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=pwh&AN=11208051&site=ehost-live

Database: MasterFILE Complete

Trent Smith, S. (2018). A Call to Arms. World War II, 33(3), 64–71. http://eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f6h&AN=131241187&site=ehost-live

Suter, K. (2007). The Philippines: What Went Wrong with One Asian Economy. Contemporary Review, 289(1684), 53–59. http://eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=pwh&AN=24884353&site=ehost-live

FRANCIA, L. H. (2014). José Rizal: A Man for All Generations. Antioch Review, 72(1), 44–60. https://doi-org.eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/10.7723/antiochreview.72.1.0044

Luyt, B. (2019). The early years of Philippine Studies , 1953 to 1966. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 50(2), 202–221. https://doi-org.eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/10.1017/S0022463419000237

Database: ABI/INFORM

Mercene, R. (2016, Mar 27). A shining moment in philippine history. Business Mirror Retrieved from http://eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/docview/1776085049?accountid=27140

A guide to the philippines' history, economy and politics: Daily chart. (2016, May 06). The Economist (Online), Retrieved from http://eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/docview/1787331077?accountid=27140

Carroll, J. (1961). Contemporary Philippine Historians and Philippine History. Journal of Southeast Asian History, 2(3), 23-35. Retrieved October 22, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20067346

Zafra, N. (1958). On The Writing Of Philippine History. Philippine Studies, 6(4), 454-460. Retrieved October 22, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/42720410

Larkin, J. (1982). Philippine History Reconsidered: A Socioeconomic Perspective. The American Historical Review, 87(3), 595-628. doi:10.2307/1864158

Mulder, N. (1994). The Image of Philippine History and Society. Philippine Studies, 42(4), 475-508. Retrieved October 22, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/42633467

OWEN, N. (1974). The Principalia in Philippine History: Kabikolan, 1790-1898. Philippine Studies, 22(3/4), 297-324. Retrieved October 22, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/42634875

Baumgartner, J. (1977). Notes on Piracy and Slaving in Philippine History. Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society, 5(4), 270-272. Retrieved October 22, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/29791568

Cristina E. Torres. (1997). Health Issues and the Quality of Life in Philippine History. Quality of Life Research, 6(5), 461-462. Retrieved October 22, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4035251

Farrell, J. (1954). An Abandoned Approach to Philippine History: John R. M. Taylor and the Philippine Insurrection Records. The Catholic Historical Review, 39(4), 385-407. Retrieved October 22, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25015651

GEALOGO, F. (2013). Reflections of A Filipino Social Historian. Philippine Sociological Review, 61(1), 55-68. Retrieved October 23, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/43486355

MAOHONG, B. (2012). On Studies of the History of the Philippines in China. Philippine Studies: Historical & Ethnographic Viewpoints, 60(1), 102-116. Retrieved October 23, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/42634704

Nexis Uni

(October 3, 2020 Saturday). Studies on Philippine history. The Philippine Star. https://advance-lexis-com.eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:6109-GWY1-JCH9-G1MH-00000-00&context=1516831 .

ABI/INFORM

Filipino history, culture studied in international seminar. (2019, May 16). Business Mirror Retrieved from http://eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/docview/2226338201?accountid=27140

Association For Asian Studies

Totanes, V. R. (2010). History of the Filipino people and martial law: a forgotten chapter in the history of a history book, 1960-2010. Philippine Studies, 58(3), 313–348. http://eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bas&AN=BAS788208&site=ehost-live

Okamura, J. Y. (1996). Filipino American history, identity and community in Hawai’i: in commemoration of the 90th anniversary of Filipino migration to Hawai’i. Honolulu. http://eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bas&AN=BAS515519&site=ehost-live

Association for Asian Studies

Rafael, V. L. (1995). Discrepant histories: translocal essays on Filipino cultures. Philadelphia, Pa. http://eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bas&AN=BAS559630&site=ehost-live

Association for Asian Studies

Pinzon, J. C. (2015). Remembering Philippine history: satire in popular songs. South East Asia Research, 23(3), 423–442. http://eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bas&AN=BAS872861&site=ehost-live

- << Previous: Martial Arts

- Next: Costumes & Fashion >>

- Last Updated: Feb 6, 2024 12:29 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/philippines

An equal opportunity/affirmative action institution . Use of this site implies consent with our Usage Policy .

Terms of Use | UH System | UH Mānoa

- Research Guides

- Learning Skills

- Teaching Resources

- Study Spaces

- Ask A Librarian

- Interlibrary Loan

- Library Faculty/Staff (Internal)

2550 McCarthy Mall Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 USA 808-956-7214 (Reference) 808-956-7203 (Circulation)

Library Digital Collections Disclaimer and Copyright information

© University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library

Philippine History

A Brief History of the Philippines from a Filipino Perspective Pre-Colonial Period The oldest human fossil remains are found in Palawan, on the western fringe of the archipelago. These remains are about 30,000 years old, suggesting that the first human migrations to the islands took palce during the last Ice Age, when land bridiges connected the archipelago to mainland Asia and Borneo. The islands were eventually inhabited by different groups that developed domestic trade linkages.

The archaelogical evidence shows a rich pre- colonial culture that included skills in weaving, ship-building, mining and goldsmithing. Contact with Asian neighbors date back to at least 500 B. C. Trade linkages existed with the powerful Hindu empires in Java and Sumatra. These linkages were venues for exchanges with Indian culture, including the adoption of syllabic scripts which are still used by indigenous groups in Palawan and Mindoro. Trade ties with China were extensive by the 10th centuray A. D. while contact with Arab traders reached its peak about the 12th century.

By the time the Spaniards arrived, Islam was well established in Mindanao and had started to influence groups as far north as Luzon. Many existing health beliefs and practices in the Philippines are rooted back in the pre-colonial period. This includes magico-religious elements, such as beliefs in spirits and sorcery as causes of illness, as well as empirical aspects such as the use of medicinal plants. Archaelogical sites in the Philippines have yielded skeletal remains showing intricate ornamental dental work and the use of trephination (boring a hole into the skull as a magical healing ritual).

Today’s traditional medicinal practitioners can trace their origins back to the pre-colonial period – the psychic surgeons, with their flair for drama, parallel the pre-hispanic religious practicioners (babaylan and catalonan) who also played roles as healers. The Spanish Occupation When the Spaniards arrived in the Philippines, the indios (natives) had reached different levels of political development, including simple communal groups, debt peonage (often erroneously described as slavery) and proto-feudal confederations.

The Spaniards imposed a feudal system, concentrating populations under their control into towns and estates. During the first two centuries of their occupation, the Spaniards used the Philippines mainly as a connecting point for their China-Acapulco (Mexico) trade. The country’s economic backwardness was reinforced by Roman Catholicism, which was practiced in a form that retained many pre-colonial elements such as animism while incorporating feudal aspects of the colonizers’ religion such as dogmatism, authoritarianism and patriarchial oppression.

The Spaniards wer never able to consolidate political control over the entire archipelago, with Muslims and indigenous resisting the colonizers most effectively. Among the groups that were subjugated, there were numerous localized revolts throughout the Spanish occupation. In the 19th century , the Philippines was opened to world trade, allowing the limited entry of liberal ideas. By the late 19th century , there was a distinct Filipino nationalist movement which erupted into a revolution in 1896, culminating with the establishment of Asia’s first republican government in 1898.

Spain laid the foundation for a feudal health care system . The religious orders built charity hospitals, often next to churches, dispensing services to the indio. Medical education was not extended to the indio until late in the 19th century, through the University of Santo Tomas. This feudal system of the rich extending charity to the poor persists to this day among many church-run as well as non-sectarian institutions. The U. S. Occupation (1898-1946) The first Philippine Republic was short-lived. Spain had lost a war with the United States .

The Philippines was illegally ceded to the United States at the Treaty of Paris for US$20 million, together with Cuba and Puerto Rico. A Filipino-American War broke out as the United States attempted to establish control over the islands. The war lasted for more than 10 years , resulting in the death of more than 600,000 Filipinos. The little-known war has been described by historians as the “first Vietnam” , where US troops first used tactics such as strategic hamleting and scorched-earth policy to “pacify” the natives. The United States established an economic system giving the colonizers full rights to the country’s resources.

The Spanish feudal system was not dismantled; in fact, through the system of land registration that favored the upper Filipino classes , tenancy became more widespread during the US occupation. A native elite, including physicians trained in the United States , was groomed to manage the economic and political system of the country. The U. S. also introduced western modells of educational and health-care systems which reinforced elitism and a colonial mentality that persists to this day, mixed with the Spanish feudal patron-client relationship.

Militant peasant and workers’ groups were formed during the U. S. occupation despite the repressive situation. A movement for Philippine independence, involving diverse groups, continued throughout the occupation. A Commonwealth government was established in 1935 to allow limited self-rule but this was interrupted by the Second World War and the Japanese occupation. The guerilla movement against Japanese fascism was led mainly by socialists and communists, known by their acronym, HUKS. Shortly after the end of the Second World War , flag independence was regained although the U.

S. imposed certain conditions, including the disenfranchisement of progressive political parties , the retention of U. S. military bases and the signing of economic agreements allowing the U. S. continued control over the Philippine economy. The Philippine Republic (1946 – ) The political system of the Philippines was basically pattered after the U. S. , with a bicameral legislature and a president elected every four years, limited to one re-election. Philippine democracy remained elitist with two political parties taking turns at the leadership.