Examples of How to Introduce Yourself on Online Dating Sites & Apps

Don't stress about introducing yourself. Use these dating site introduction examples to help you craft the perfect line to show your match the authentic you.

Michele is a writer who has been published both locally and internationally.

Learn about our Editorial Policy .

So you've created a dating profile and found a few people with potential. Great! But now what? It's time to let your personality shine through with a winning first message. If you're not sure how to introduce yourself on a dating site or app, try out these fun options.

Basic First Message Examples

Just as you would introduce yourself to someone in real life, start with a form of "hello" and the short version of why you're reaching out.

- Hey there, stranger, wanna become acquaintances?

- Bonjour/Ciao/Hola, I see you're free to travel the world, but are you free to chat?

- Hello, it's nice to virtually meet you! (Insert handshake or high-five emoji.)

- Hi, are you up for the challenge of communicating awkwardly through text?

- What's up? If you're interested in chatting, message back with the answer to this question. (Include a simple question that requires them to read your profile such as "What's my favorite color?")

- 14 "About Me" Dating Site Examples to Help You Find the One

- 25 Best Opening Lines for Online Dating

- How to Cancel a Date Without Being Rude

Related: Insider Tips to Write the Perfect Dating Profile

Messages That Emphasize Similarities

Your similarities are the things you can bond over from the start of any type of relationship. Find a creative way to incorporate something you both like into your first message to show you've paid attention to who they are.

- Looks like we're the only two people in the world with a passion for narwhal conservation, maybe we should team up and talk strategy?

- Hello, fellow Dodgers fan. Did you catch that play last night?

- I just finished reading The President Is Missing too! Did you see that ending coming?

- I can't believe I found another person who's been to Chincoteague Island! What was your favorite place to explore?

- Is it creepy or cool that we're wearing the same T-shirt in our profile pictures?

- I see we're both dog lovers! Tell me about that cutie in your profile picture. First your dog, then you. (Insert winky face emoji.)

- I've always wanted to get into (insert hobby they enjoy here). Do you have any tips or advice for beginners like me?

Related : 25 Best Opening Lines for Online Dating

Lead With a Question to Get Their Interest

Start the conversation off with an active request that includes a general interest question . Look for topics the other person is interested in on their profile, then come up with a fun question to break the ice .

- After reading your profile, I'm dying to know — who is your favorite Spiderman? Tobey, Tom, or Andrew?

- I'm new to online dating, any tips on how to start up a conversation?

- Sending this message is the most spontaneous thing I've ever done. What's the most spontaneous thing you've ever done?

- They say a picture's worth a thousand words. What would your profile picture say if it could talk?

- Laughter is supposed to be the best medicine. What's the funniest thing that's happened to you recently?

- I noticed you're a book lover. What was your last five-star read?

Try a Flirty Message to Introduce Yourself

It's okay to lead with a little flirtation , just be careful not to come on too strong or sound like all you're after is a physical relationship.

- Can I call you Q.T., or do you prefer Jeff?

- Whoever makes the first move wins this round. That's one point for me.

- I'm interested, what are you gonna do about it?

- There's only one way my day could get better — a message from you.

- I need to update my profile, I forgot to add one of my likes — you.

- Do you believe in love at first swipe, or should we unmatch and swipe again?

- This might be too cheesy but you look really gouda in your profile picture.

Related : How to Reply to Online Dating Messages the Right Way

Introduce Yourself With an Intro Inspired by Pop Culture

Use your favorite movies, television shows, songs, and other pop culture references for a casual intro that speaks to your interests and personality.

- Joey's classic pickup line from Friends: "How you doin'?"

- Fonzie's catchphrase from Happy Days: "Aaay!"

- Use the Breaking Bad line: "I am the one who knocks." Follow this with:"Are you the one who answers?"

- Ask: "Do you want to get to know each other better?" followed by the line from How I Met Your Mother: "It's gonna be legen - wait for it - dary."

- From Friday Night Lights: "Clear eyes, full hearts, can't lose."

- The classic alien line from sci-fi movies: "I come in peace."

- Use a play on the iconic Stranger Things character: "On a scale from 1 to 10 you're definitely Eleven."

- From the Barbie movie: "Hi Barbie!"

Put Your Best Message Forward

Getting started in online dating is all about taking the leap to send that first message, and these introduction lines for dating sites will help you open a conversation. Keep the message short and to the point, but include some of your own personality or interests to give it a personalized feel. You can never go wrong by being yourself!

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- The Virtues and Downsides of Online Dating

30% of U.S. adults say they have used a dating site or app. A majority of online daters say their overall experience was positive, but many users – particularly younger women – report being harassed or sent explicit messages on these platforms

Table of contents.

- 1. Americans’ personal experiences with online dating

- 2. Users of online dating platforms experience both positive – and negative – aspects of courtship on the web

- 3. Americans’ opinions about the online dating environment

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

How we did this

Pew Research Center has long studied the changing nature of romantic relationships and the role of digital technology in how people meet potential partners and navigate web-based dating platforms. This particular report focuses on the patterns, experiences and attitudes related to online dating in America. These findings are based on a survey conducted Oct. 16 to 28, 2019, among 4,860 U.S. adults. This includes those who took part as members of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses, as well as respondents from the Ipsos KnowledgePanel who indicated that they identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual (LGB). The margin of sampling error for the full sample is plus or minus 2.1 percentage points.

Recruiting ATP panelists by phone or mail ensures that nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. This gives us confidence that any sample can represent the whole U.S. adult population (see our Methods 101 explainer on random sampling). To further ensure that each ATP survey reflects a balanced cross-section of the nation, the data are weighted to match the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories.

For more, see the report’s methodology about the project. You can also find the questions asked, and the answers the public provided in this topline .

From personal ads that began appearing in publications around the 1700s to videocassette dating services that sprang up decades ago, the platforms people use to seek out romantic partners have evolved throughout history. This evolution has continued with the rise of online dating sites and mobile apps.

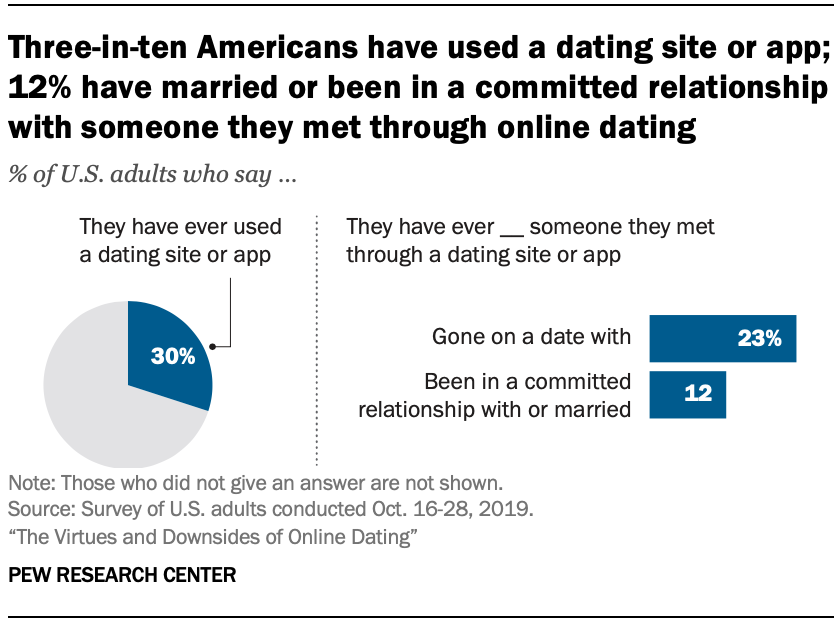

Today, three-in-ten U.S. adults say they have ever used an online dating site or app – including 11% who have done so in the past year, according to a new Pew Research Center survey conducted Oct. 16 to 28, 2019. For some Americans, these platforms have been instrumental in forging meaningful connections: 12% say they have married or been in a committed relationship with someone they first met through a dating site or app. All in all, about a quarter of Americans (23%) say they have ever gone on a date with someone they first met through a dating site or app.

Previous Pew Research Center studies about online dating indicate that the share of Americans who have used these platforms – as well as the share who have found a spouse or partner through them – has risen over time. In 2013, 11% of U.S. adults said they had ever used a dating site or app, while just 3% reported that they had entered into a long-term relationship or marriage with someone they first met through online dating. It is important to note that there are some changes in question wording between the Center’s 2013 and 2019 surveys, as well as differences in how these surveys were fielded. 1 Even so, it is clear that websites and mobile apps are playing a larger role in the dating environment than in previous years. 2

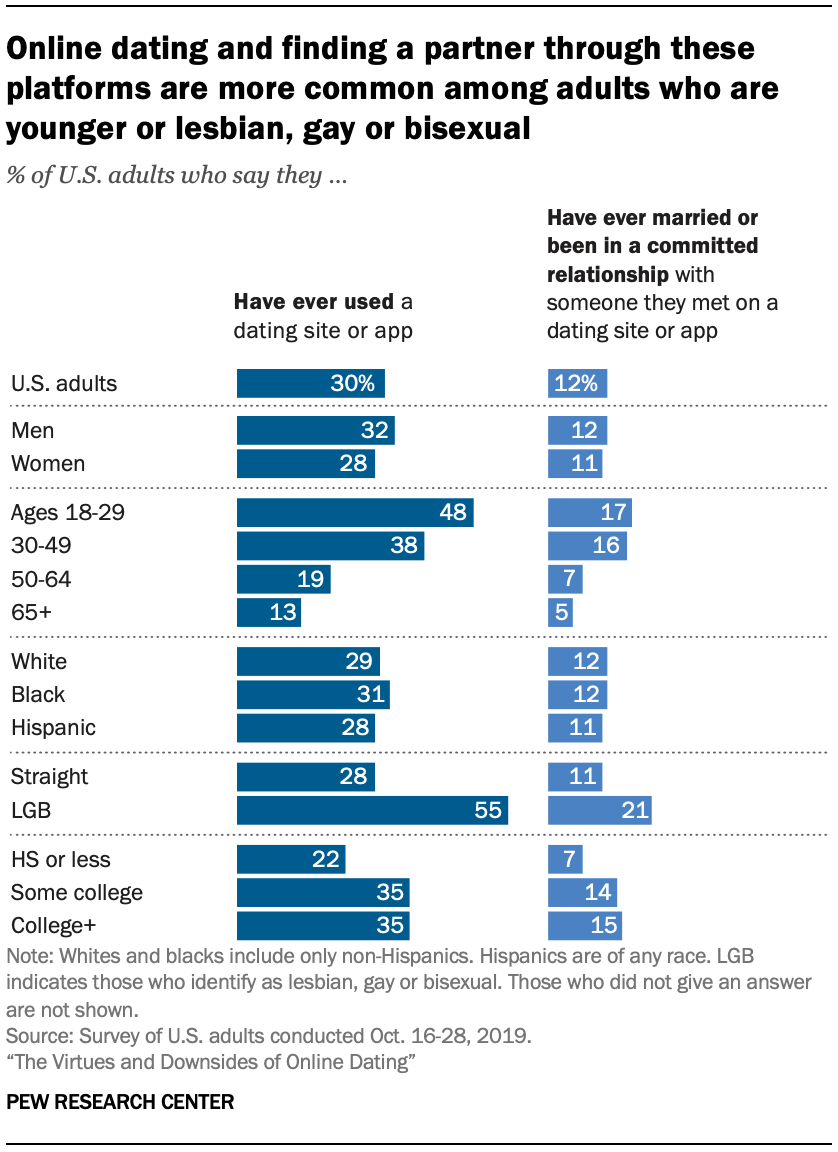

The current survey finds that online dating is especially popular among certain groups – particularly younger adults and those who identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual (LGB). Roughly half or more of 18- to 29-year-olds (48%) and LGB adults (55%) say they have ever used a dating site or app, while about 20% in each group say they have married or been in a committed relationship with someone they first met through these platforms. Americans who have used online dating offer a mixed look at their time on these platforms.

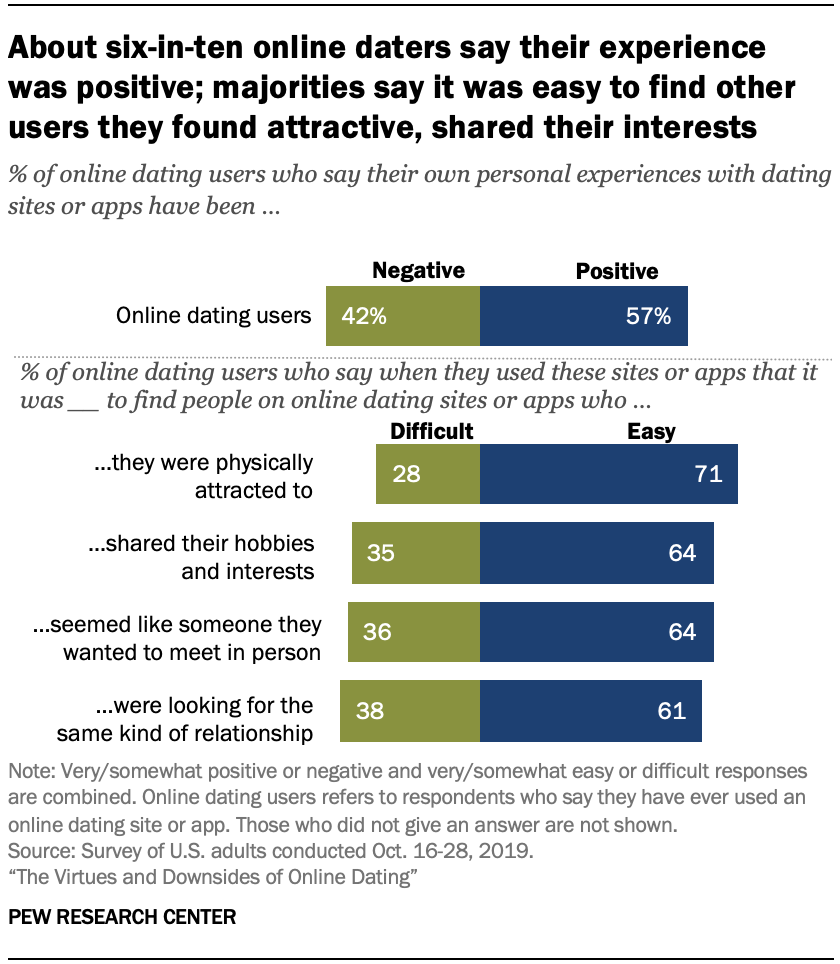

On a broad level, online dating users are more likely to describe their overall experience using these platforms in positive rather than negative terms. Additionally, majorities of online daters say it was at least somewhat easy for them to find others that they found physically attractive, shared common interests with, or who seemed like someone they would want to meet in person. But users also share some of the downsides to online dating. Roughly seven-in-ten online daters believe it is very common for those who use these platforms to lie to try to appear more desirable. And by a wide margin, Americans who have used a dating site or app in the past year say the experience left them feeling more frustrated (45%) than hopeful (28%).

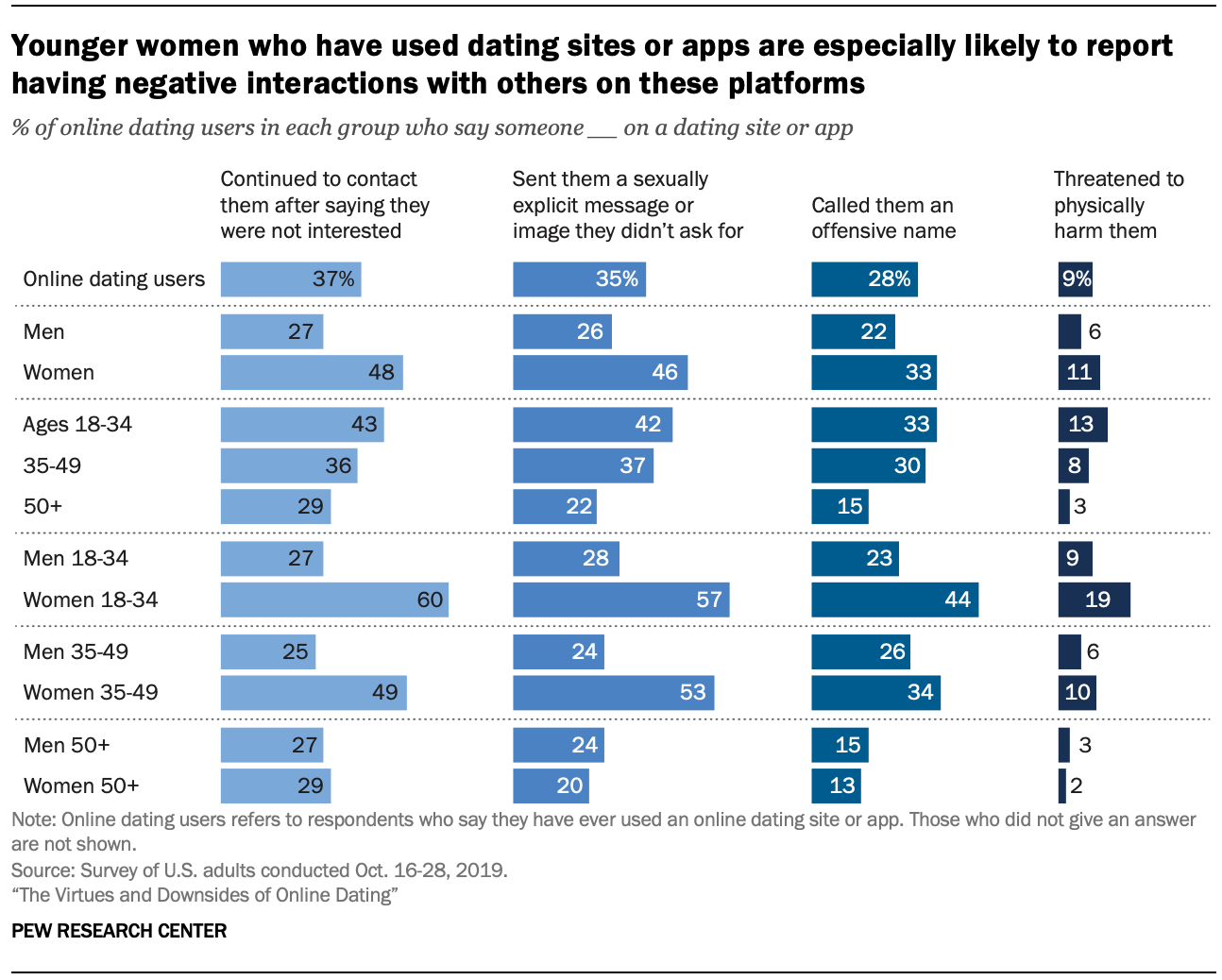

Other incidents highlight how dating sites or apps can become a venue for bothersome or harassing behavior – especially for women under the age of 35. For example, 60% of female users ages 18 to 34 say someone on a dating site or app continued to contact them after they said they were not interested, while a similar share (57%) report being sent a sexually explicit message or image they didn’t ask for.

Online dating has not only disrupted more traditional ways of meeting romantic partners, its rise also comes at a time when norms and behaviors around marriage and cohabitation also are changing as more people delay marriage or choose to remain single.

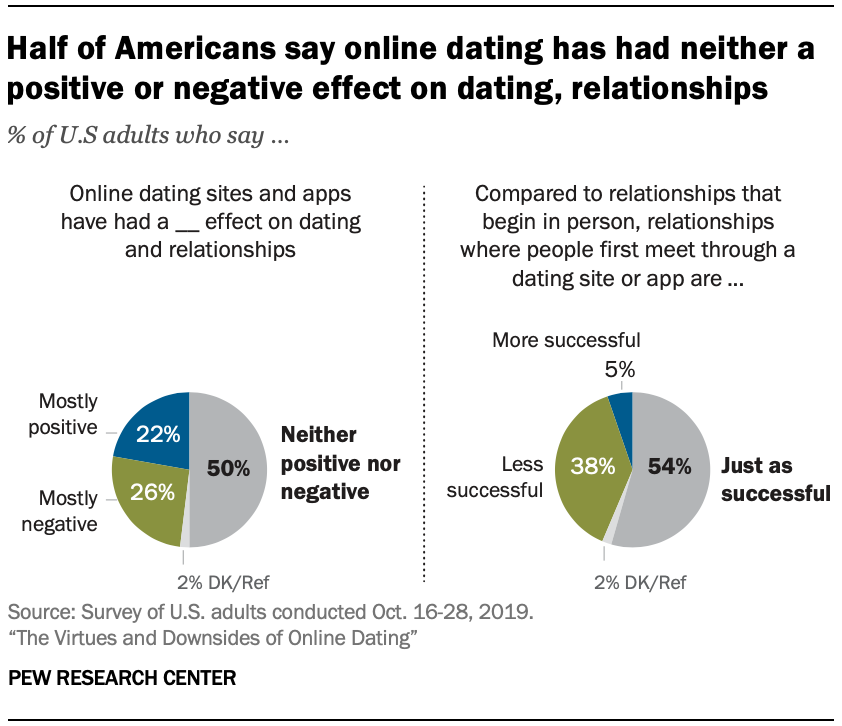

These shifting realities have sparked a broader debate about the impact of online dating on romantic relationships in America. On one side, some highlight the ease and efficiency of using these platforms to search for dates, as well as the sites’ ability to expand users’ dating options beyond their traditional social circles. Others offer a less flattering narrative about online dating – ranging from concerns about scams or harassment to the belief that these platforms facilitate superficial relationships rather than meaningful ones. This survey finds that the public is somewhat ambivalent about the overall impact of online dating. Half of Americans believe dating sites and apps have had neither a positive nor negative effect on dating and relationships, while smaller shares think its effect has either been mostly positive (22%) or mostly negative (26%).

Terminology

Throughout this report, “online dating users” and “online daters” are used interchangeably to refer to the 30% of respondents in this survey who answered yes to the following question: “Have you ever used an online dating site or dating app?”

These findings come from a nationally representative survey of 4,860 U.S. adults conducted online Oct. 16 to 28, 2019, using Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel. The following are among the major findings.

Younger adults – as well as those who identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual – are especially likely to use online dating sites or apps

Some 30% of Americans say they have ever used an online dating site or app. Out of those who have used these platforms, 18% say they are currently using them, while an additional 17% say they are not currently doing so but have used them in the past year.

Experience with online dating varies substantially by age. While 48% of 18- to 29-year-olds say they have ever used a dating site or app, that share is 38% among 30- to 49-year-olds, and it is even smaller among those ages 50 and older. Still, online dating is not completely foreign to those in their 50s or early 60s: 19% of adults ages 50 to 64 say they have used a dating site or app.

Beyond age, there also are striking differences by sexual orientation. 3 LGB adults are about twice as likely as straight adults to say they have used a dating site or app (55% vs. 28%). 4 And in a pattern consistent with previous Pew Research Center surveys , college graduates and those with some college experience are more likely than those with a high school education or less to say they’ve ever online dated.

There are only modest differences between men and women in their use of dating sites or apps, while white, black or Hispanic adults all are equally likely to say they have ever used these platforms.

At the same time, a small share of U.S. adults report that they found a significant other through online dating platforms. Some 12% of adults say they have married or entered into a committed relationship with someone they first met through a dating site or app. This too follows a pattern similar to that seen in overall use, with adults under the age of 50, those who are LGB or who have higher levels of educational attainment more likely to report finding a spouse or committed partner through these platforms.

A majority of online daters say they found it at least somewhat easy to come across others on dating sites or apps that they were physically attracted to or shared their interests

Online dating users are more likely to describe their overall experience with using dating sites or apps in positive, rather than negative, terms. Some 57% of Americans who have ever used a dating site or app say their own personal experiences with these platforms have been very or somewhat positive. Still, about four-in-ten online daters (42%) describe their personal experience with dating sites or apps as at least somewhat negative.

For the most part, different demographic groups tend to view their online dating experiences similarly. But there are some notable exceptions. College-educated online daters, for example, are far more likely than those with a high school diploma or less to say that their own personal experience with dating sites or apps is very or somewhat positive (63% vs. 47%).

At the same time, 71% of online daters report that it was at least somewhat easy to find people on dating sites or apps that they found physically attractive, while about two-thirds say it was easy to find people who shared their hobbies or interests or seemed like someone they would want to meet in person.

While majorities across various demographic groups are more likely to describe their searches as easy, rather than difficult, there are some differences by gender. Among online daters, women are more likely than men to say it was at least somewhat difficult to find people they were physically attracted to (36% vs. 21%), while men were more likely than women to express that it was difficult to find others who shared their hobbies and interests (41% vs. 30%).

Men who have online dated in the past five years are more likely than women to feel as if they did not get enough messages from other users

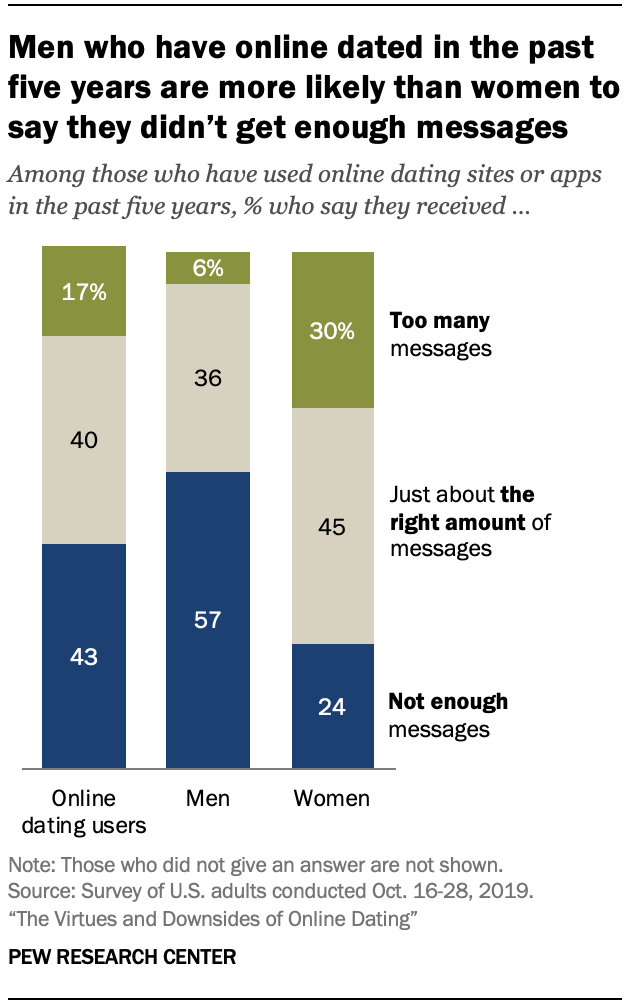

When asked if they received too many, not enough or just about the right amount of messages on dating sites or apps, 43% of Americans who online dated in the past five years say they did not receive enough messages, while 17% say they received too many messages. Another 40% think the amount of messages they received was just about right.

There are substantial gender differences in the amount of attention online daters say they received on dating sites or apps. Men who have online dated in the past five years are far more likely than women to feel as if they did not get enough messages (57% vs. 24%). On the other hand, women who have online dated in this time period are five times as likely as men to think they were sent too many messages (30% vs. 6%).

The survey also asked online daters about their experiences with getting messages from people they were interested in. In a similar pattern, these users are more likely to report receiving too few rather than too many of these messages (54% vs. 13%). And while gender differences remain, they are far less pronounced. For example, 61% of men who have online dated in the past five years say they did not receive enough messages from people they were interested in, compared with 44% of women who say this.

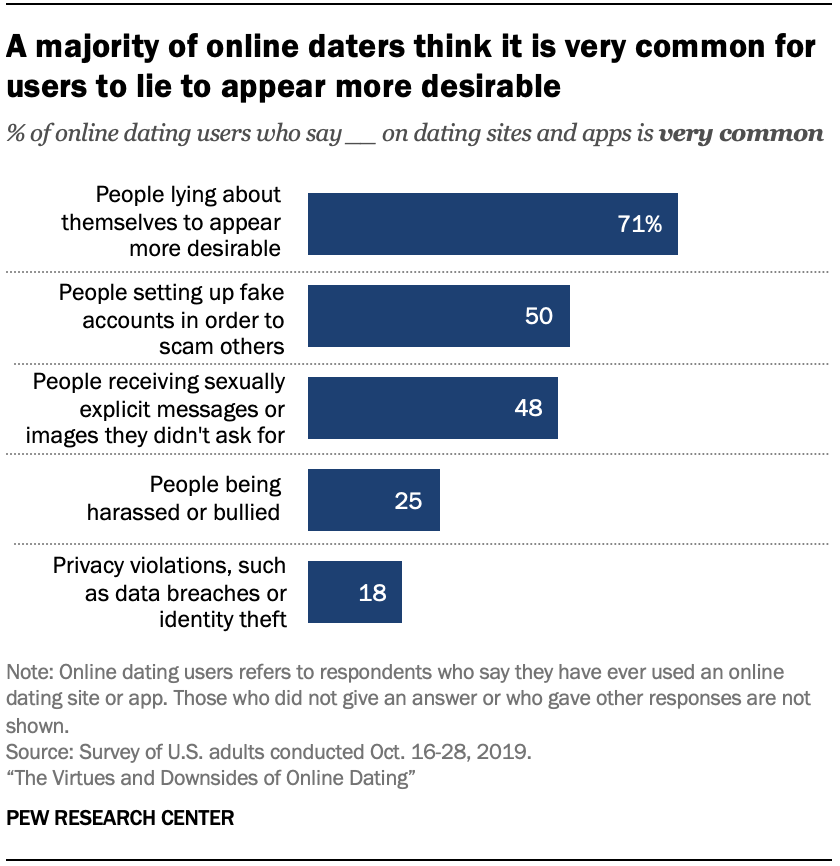

Roughly seven-in-ten online daters think people lying to appear more desirable is a very common occurrence on online dating platforms

Online daters widely believe that dishonesty is a pervasive issue on these platforms. A clear majority of online daters (71%) say it is very common for people on these platforms to lie about themselves to appear more desirable, while another 25% think it is somewhat common. Only 3% of online daters think this is not a common occurrence on dating platforms.

Smaller, but still substantial shares, of online daters believe people setting up fake accounts in order to scam others (50%) or people receiving sexually explicit messages or images they did not ask for (48%) are very common on dating sites and apps. By contrast, online daters are less likely to think harassment or bullying, and privacy violations, such as data breaches or identify theft, are very common occurrences on these platforms.

Some users – especially younger women – report being the target of rude or harassing behavior while on these platforms

Some experts contend that the open nature of online dating — that is, the fact that many users are strangers to one another — has created a less civil dating environment and therefore makes it difficult to hold people accountable for their behavior. This survey finds that a notable share of online daters have been subjected to some form of harassment measured in this survey.

Roughly three-in-ten or more online dating users say someone through a dating site or app continued to contact them after they said they were not interested (37%), sent them a sexually explicit message or image they didn’t ask for (35%) or called them an offensive name (28%). Fewer online daters say someone via a dating site or app has threatened to physically harm them.

Younger women are particularly likely to encounter each of these behaviors. Six-in-ten female online dating users ages 18 to 34 say someone via a dating site or app continued to contact them after they said they were not interested, while 57% report that another user has sent them a sexually explicit message or image they didn’t ask for. Other negative interactions are more violent in nature: 19% of younger female users say someone on a dating site or app has threatened to physically harm them – roughly twice the rate of men in the same age range who say this.

The likelihood of encountering these kinds of behaviors on dating platforms also varies by sexual orientation. Fully 56% of LGB users say someone on a dating site or app has sent them a sexually explicit message or image they didn’t ask for, compared with about one-third of straight users (32%). LGB users are also more likely than straight users to say someone on a dating site or app continued to contact them after they told them they were not interested, called them an offensive name or threatened to physically harm them.

Online dating is not universally seen as a safe way to meet someone

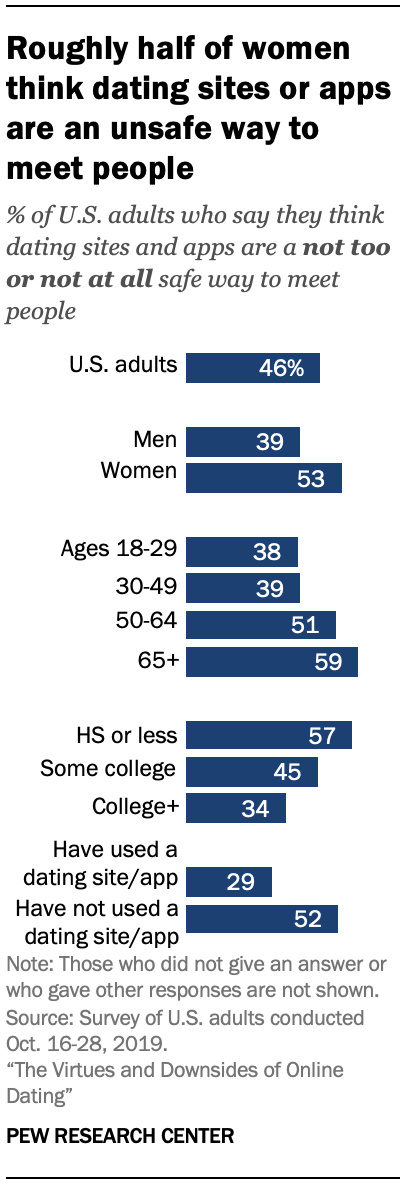

The creators of online dating sites and apps have at times struggled with the perception that these sites could facilitate troubling – or even dangerous – encounters. And although there is some evidence that much of the stigma surrounding these sites has diminished over time, close to half of Americans still find the prospect of meeting someone through a dating site unsafe.

Some 53% of Americans overall (including those who have and have not online dated) agree that dating sites and apps are a very or somewhat safe way to meet people, while a somewhat smaller share (46%) believe these platforms are a not too or not at all safe way of meeting people.

Americans who have never used a dating site or app are particularly skeptical about the safety of online dating. Roughly half of adults who have never used a dating or app (52%) believe that these platforms are a not too or not at all safe way to meet others, compared with 29% of those who have online dated.

There are some groups who are particularly wary of the idea of meeting someone through dating platforms. Women are more inclined than men to believe that dating sites and apps are not a safe way to meet someone (53% vs. 39%).

Age and education are also linked to differing attitudes about the topic. For example, 59% of Americans ages 65 and older say meeting someone this way is not safe, compared with 51% of those ages 50 to 64 and 39% among adults under the age of 50. Those who have a high school education or less are especially likely to say that dating sites and apps are not a safe way to meet people, compared with those who have some college experience or who have at bachelor’s or advanced degree. These patterns are consistent regardless of each group’s own personal experience with using dating sites or apps.

Pluralities think online dating has neither helped nor harmed dating and relationships and that relationships that start online are just as successful as those that begin offline

Americans – regardless of whether they have personally used online dating services or not – also weighed in on the virtues and pitfalls of online dating. Some 22% of Americans say online dating sites and apps have had a mostly positive effect on dating and relationships, while a similar proportion (26%) believe their effect has been mostly negative. Still, the largest share of adults – 50% – say online dating has had neither a positive nor negative effect on dating and relationships.

Respondents who say online dating’s effect has been mostly positive or mostly negative were asked to explain in their own words why they felt this way. Some of the most common reasons provided by those who believe online dating has had a positive effect focus on its ability to expand people’s dating pools and to allow people to evaluate someone before agreeing to meet in person. These users also believe dating sites and apps generally make the process of dating easier. On the other hand, people who said online dating has had a mostly negative effect most commonly cite dishonesty and the idea that users misrepresent themselves.

Pluralities also believe that whether a couple met online or in person has little effect on the success of their relationship. Just over half of Americans (54%) say that relationships where couples meet through a dating site or app are just as successful as those that begin in person, 38% believe these relationships are less successful, while 5% deem them more successful.

Public attitudes about the impact or success of online dating differ between those who have used dating platforms and those who have not. While 29% of online dating users say dating sites and apps have had a mostly positive effect on dating and relationships, that share is 21% among non-users. People who have ever used a dating site or app also have a more positive assessment of relationships forged online. Some 62% of online daters believe relationships where people first met through a dating site or app are just as successful as those that began in person, compared with 52% of those who never online dated.

- Pew Research Center’s 2013 survey about online dating was conducted via telephone, while the 2019 survey was fielded online through the Center’s American Trends Panel . In addition, there were some changes in question wording between these surveys. Please read the Methodology section for full details on how the 2019 survey was conducted. ↩

- Other studies show that online dating is playing a larger role in how romantic partners meet. See Rosenfeld, Michael J., Reuben J. Thomas, and Sonia Hausen. 2019. “ Disintermediating your friends: How online dating in the United States displaces other ways of meeting .” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. ↩

- This survey includes an oversample of lesbian, gay or bisexual (LGB) adults. For more details, see the Methodology section of the report. ↩

- Other research suggests that online dating is an especially important way for populations with a small pool of potential partners – such as those who identify as gay or lesbian – to identify and meet partners. See Rosenfeld, Michael J., and Thomas, Reuben J. 2012. “ Searching for a Mate: The Rise of the Internet as a Social Intermediary .” American Sociological Review. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Gender & Tech

- LGBTQ Attitudes & Experiences

- Online Dating

- Online Harassment & Bullying

- Online Privacy & Security

- Privacy Rights

- Romance & Dating

- Sexual Misconduct & Harassment

- Social Media

U.S. women more concerned than men about some AI developments, especially driverless cars

Young women often face sexual harassment online – including on dating sites and apps, how social media users have discussed sexual harassment since #metoo went viral, there’s a large gender gap in congressional facebook posts about sexual misconduct, facts on foreign students in the u.s., most popular, report materials.

- Shareable facts about Americans’ experiences with online dating

- American Trends Panel Wave 56

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

Researched by Consultants from Top-Tier Management Companies

Powerpoint Templates

Icon Bundle

Kpi Dashboard

Professional

Business Plans

Swot Analysis

Gantt Chart

Business Proposal

Marketing Plan

Project Management

Business Case

Business Model

Cyber Security

Business PPT

Digital Marketing

Digital Transformation

Human Resources

Product Management

Artificial Intelligence

Company Profile

Acknowledgement PPT

PPT Presentation

Reports Brochures

One Page Pitch

Interview PPT

All Categories

14 Key Slides to Draft a Pitch Deck for Dating App Like Bumble!

Deepali Khatri

We live in a world where smartphone Apps have made our lives easier.

If mobile apps can help find us the right cabs, food, and salon services, then what’s wrong with getting an app that helps us find our love?

And, a big thanks to the dating apps like Bumble and Tinder that help us find the right match.

Seeing the increasing potential of the dating apps like Bumble, most entrepreneurs are now planning to invest in one such dating app. If you are interested in investing in dating app development, this blog is all you need.

Before knowing the actual cost of developing an app like Bumble, let’s know more about this platform.

Whitney Wolfe Herd, CEO of Bumble dating App, became the youngest woman billionaire in the world. This app is enjoying the spotlight these days.

What is Bumble App?

Bumble is a dating app. It was launched in 2014, and it has been growing exponentially ever since. From 1M users in 2015 to 23.5M in 2017, Bumble decided to diversify its services and came out with a new app called "Bumble BFF."

Bumble is a popular platform for people to connect and not just for those looking for their honey on Date mode.

Bumble BFF is a friendship-based app. It allows people to find friends in their area, make new friends, and meet up with them when they are in the same place.

Like Bumble, it is also growing exponentially. In 2017 , there were 1M users on the App, and in 2018, there are already 7M.

They succeeded in making people adopt their friendship app just like how they adopted Bumble.

Bumble BFF and Bumble Bizz

When Bumble was still a dating app, it had certain problems. Men would exploit the system to talk to as many women as possible, and women would also pretend to be men and other gimmicks. These problems affected the dating experience of honest users, who had fewer chances of making a connection.

With Bumble BFF , this problem is no longer present as users can also connect to build friendship with other people.

The prominent feature in this dating app is that it empowers women to take control of their matches and conversations, allowing them to make the first move.

It also opens the door for those seeking to make a new business connection on Bumble Bizz .

It introduced the signature women-first swiping right experience to the professional world.

There are many ways by which you can showcase your professional qualifications in the same app.

All of these changes were made to improve the user experience. They ensured that their users would get the best out of Bumble, and they succeeded.

This platform encourages interaction in love, friendship, and now business.

How It Works?

In this app, once the match is established, a woman is given 24 hours to make the decision, and if she fails to make the first move, the connection expires.

In the case of same-gender matches, both the person gets equal power to make the first move.

There are some interesting features that allow you to extend the time on a match or rematch with an expired connection if you are really interested in making the connection with the other person.

Bumble’s Success Story

When Bumble first started, the founders had no idea how well their App would fare. Fast forward to today, and after several significant updates, Bumble has grown to be one of the top dating apps on the market.

People find Bumble a refreshing change from Tinder, which has become a bit of a joke in the dating world. Bumble is similar to Tinder except for two key differences: women make the first move, and men can't initiate a conversation with a woman.

Bumble was launched by Whitney Wolfe Herd , who also founded Tinder. Many of her employees from Tinder moved on to join her, which has undoubtedly provided Bumble with the know-how it needs to succeed.

In addition to the BFF feature, popular updates have included a paid subscription option and the ability to swipe back on people you accidentally swiped left on.

People flock to Bumble because women make the first move, a stark contrast from the Tinder experience. Bumble also allows women to message men first, which many women find appealing.

Though the usage rate for dating apps has declined in recent years, Bumble has been able to buck the trend and reach a record high in membership.

Bumble has seen membership numbers quadruple in less than six months since being launched in the United Kingdom.

With 500 million profiles to swipe through and the ability to match with people all over the world, it's no surprise that Bumble is growing in popularity.

Bumble has positioned itself at the top of the dating app market by doubling its commitment to empowering women. They've also been a leader in the dating app industry by innovating and introducing new features.

Why is it Beneficial to Develop a Dating App Like Bumble?

As per the stats, the revenue of dating apps like Bumble is expected to reach US $2322 and is expected to grow at 9.3 %.

In order to gain a share in the profitable market, it would be the wise and right time to invest in one such dating app that is riding a growth wave.

Bumble's Original Pitch Deck Template

Bumble is a dating app that has taken the world by storm. Since its inception in 2014, it has seen rapid growth and now boasts more than 15 million users. It's no surprise then that entrepreneurs are looking to replicate this success for their ventures - but how do you go about creating a compelling pitch deck? We've compiled 14 essential slides from our original Bumble Pitch Deck into one handy guide so you can start crafting your perfect pitch today.

This article will take you through each slide step-by-step to help make sure yours is up to scratch too. Ready? Let's get started...

Click Here to explore world's largest collection of Pitch Decks

The cover slide.

Meeting new people and building strong connections has now become easy, thanks to this amazing Bumble Investor Funding Elevator pitch deck.

The added advantage of this dating app is that it is not just for those looking to date. But, the idea is to arm all those seeking to make new friends, business relations, etc.

Depicted here is the cover slide of this amazing Bumble pitch deck showcasing business graphs—a great tool for people looking for business mentors, and friends.

Download this PowerPoint Template Now

The Problem Slide

Next, we present our problem slide that highlights the issues faced by people all over the dating applications. It talks about the unmonitored space given to people on social media dominated by abused user experience.

In addition, this template talks about other problems like harassment and sexual misconduct , and lesser digital satisfaction that are faced by people using other dating apps.

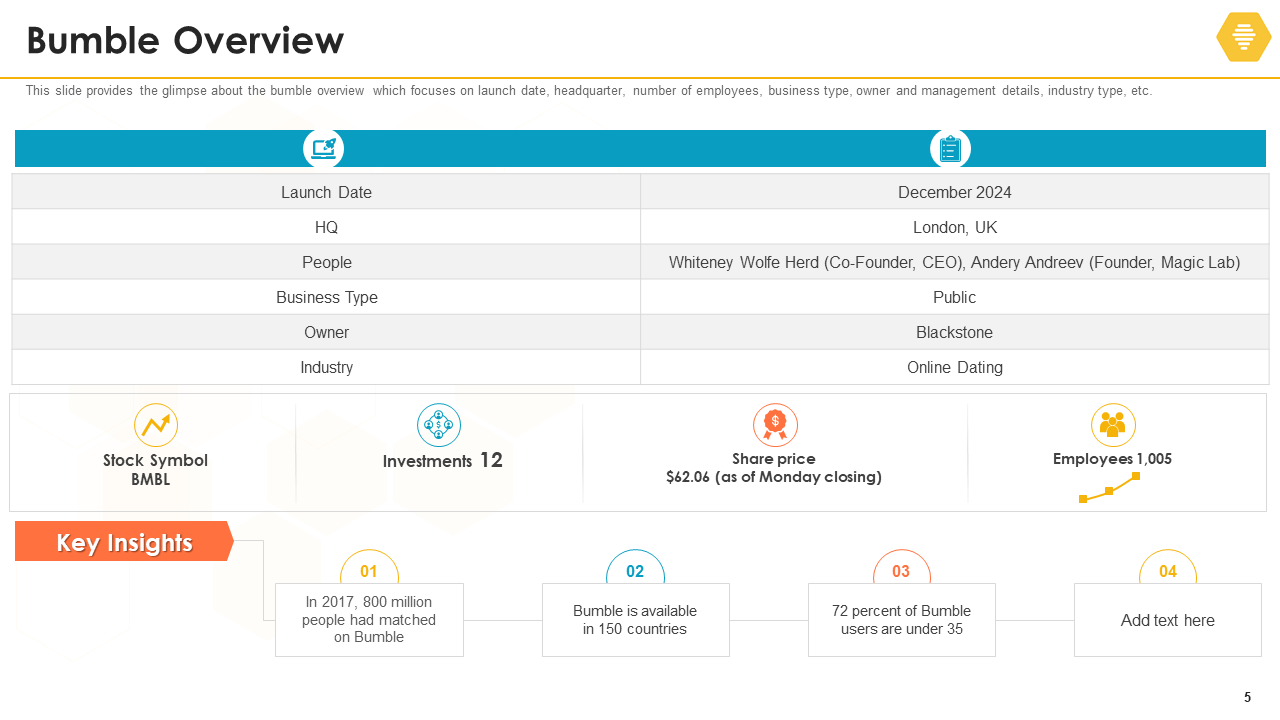

Bumble Overview

If you are thinking of investing in one such app, it is vital to be aware of its overview, which is where this bumble overview template comes in handy.

It provides a glimpse of its launch date, headquarter, business type and management details.

Along with these, other areas covered in the slides are the number of employees, industry type, etc.

Share some key insights with your audience by grabbing this editable bumble overview template.

Need of Bumble Dating App

Bumble is different from other dating apps. Unlike others, it has solved the problem of bullying and abuse.

The given slide elucidates the need for this dating app and lists out the point that surpasses other such applications.

It focuses on eliminating bullying and abusive user experience .

Nevertheless, it also talks about working on antiquated dating norms and changing global view for women.

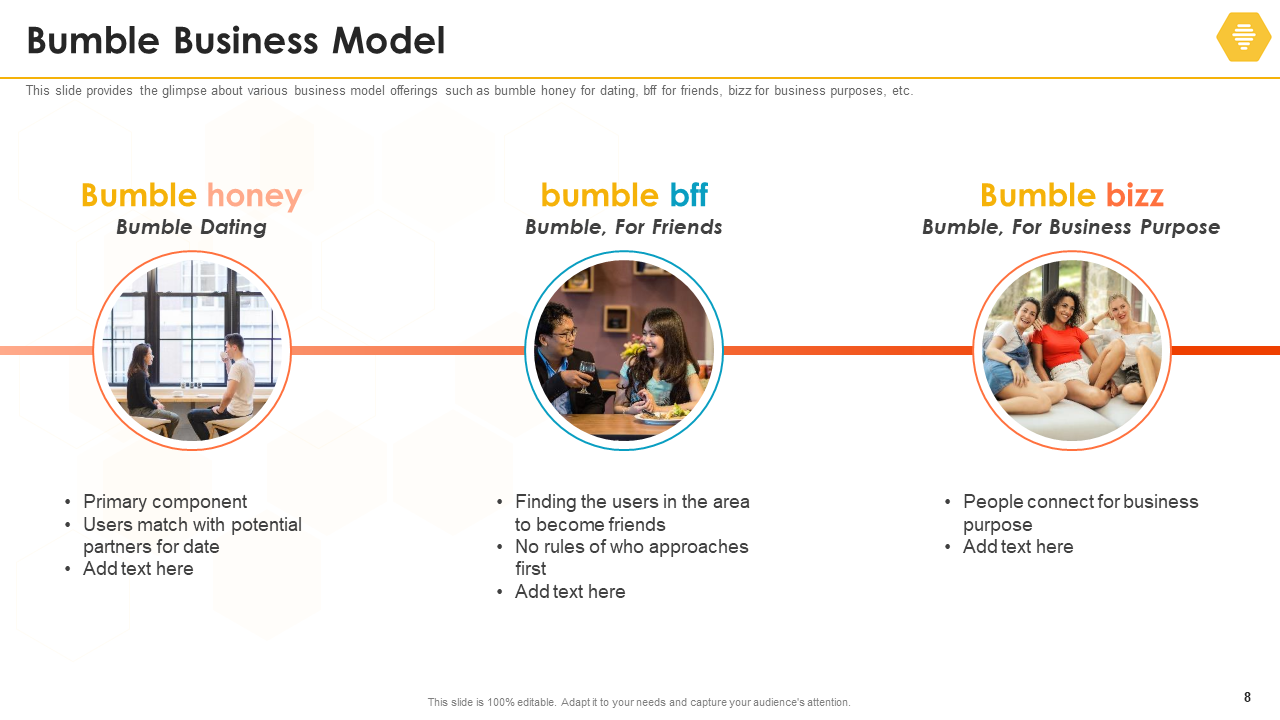

Bumble Business Model

Bumble has a lot more to offer which is clearly depicted in the given bumble business model PowerPoint template. It gives a glimpse of various business model offerings such as Bumble honey used for dating purpose , Bumble BFF for making new friends, and Bumble BIZZ for people looking to connect for business purpose.

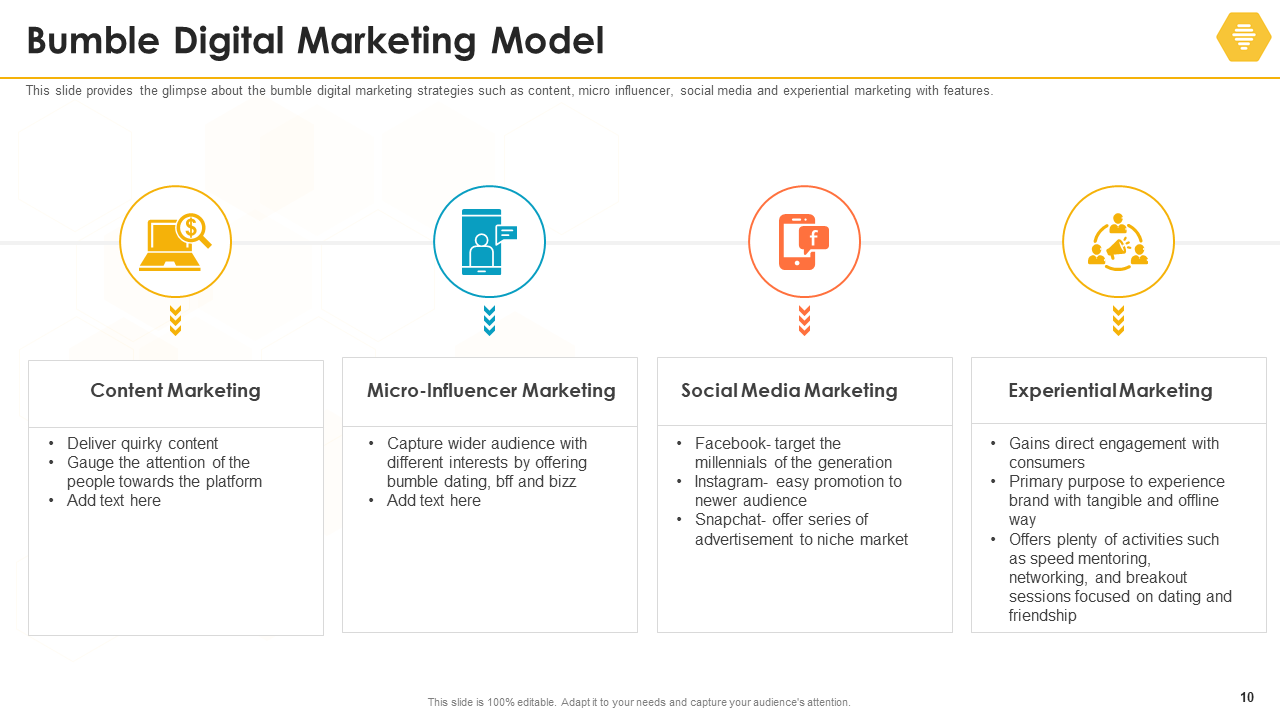

Bumble Digital Marketing Model

The given slide walks you through the Digital marketing strategies namely content marketing, social media marketing, experiential marketing and micro influencer marketing .

The idea behind introducing this slide is to gauge the attention of people towards the platform.

It is good for those seeking to invest in an application with different interests. All this and more can be easily done with this well framed pitch deck offering bumble bizz, dating, and bff under a single platform.

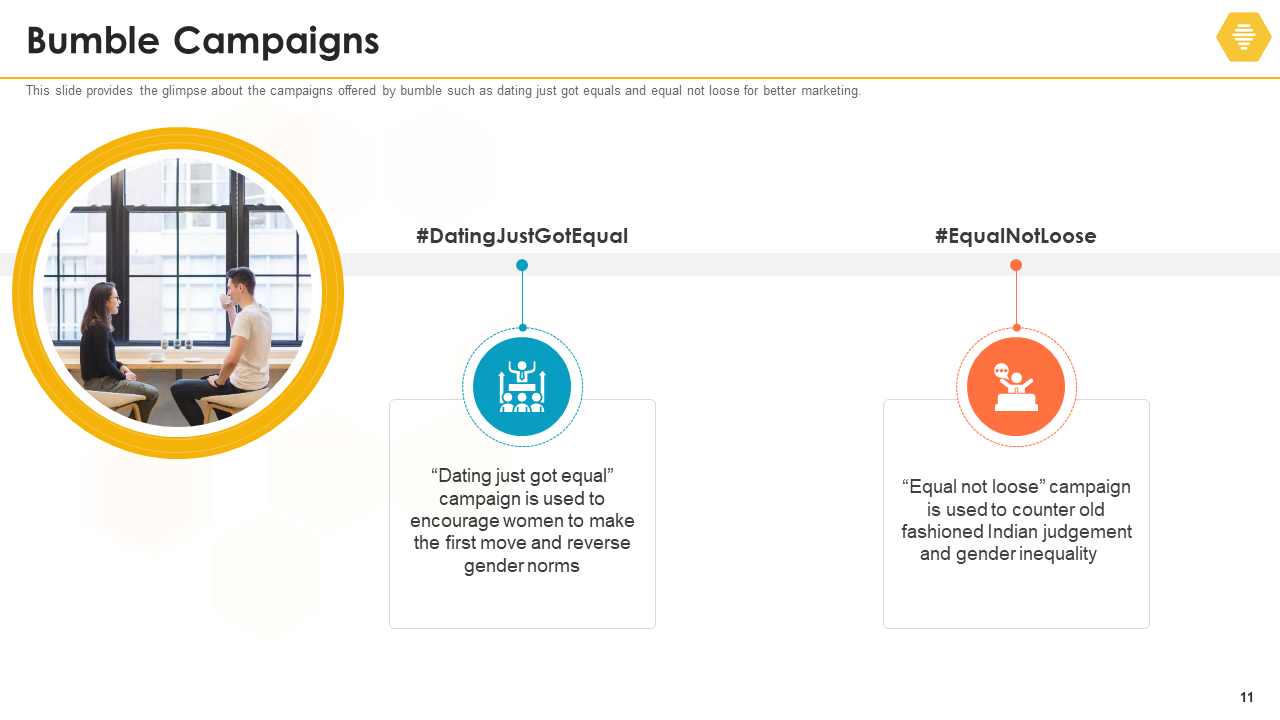

Bumble Campaigns

To shed some light over the importance of Bumble campaigns we have introduced this Bumble campaigns PowerPoint slide.

It showcases different campaigns offered by this platform that intrigues your audience. Some of the campaigns depicted in the given templates are dating just got equal and equal not loose.

The main purpose of coming up with such kind of campaigns is to perform better in terms of marketing and beat the high-level competition.

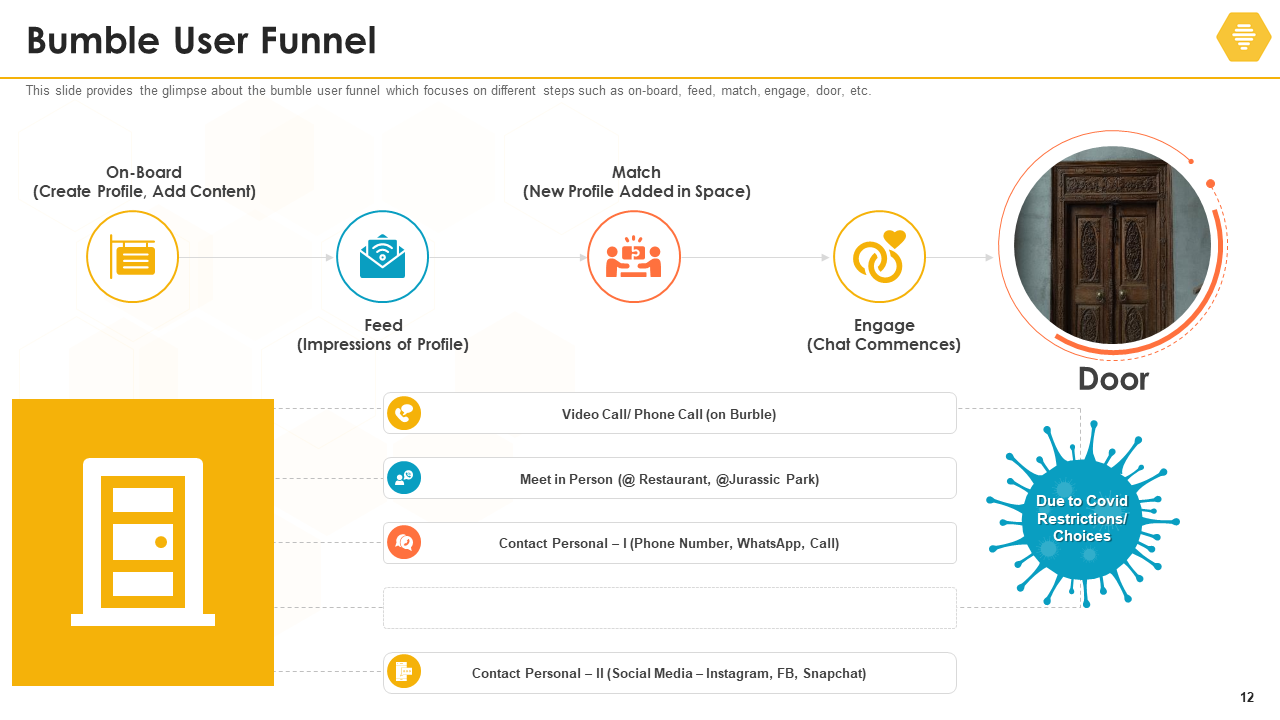

Bumble User Funnel

If you are keen to convert your prospective investors into your clients you must be able to present different steps of bumble user funnel in a succinct way. This is where our user funnel comes in handy.

Incorporating different steps such as on board, feed, match, and engage ; this slide itself showcases a sequence to be followed by the users. We have also covered some points keeping in mind the COVID restrictions.

Considering such restrictions, the deck introduces you to the added advantage of video calling and meeting in person by exchanging contact details.

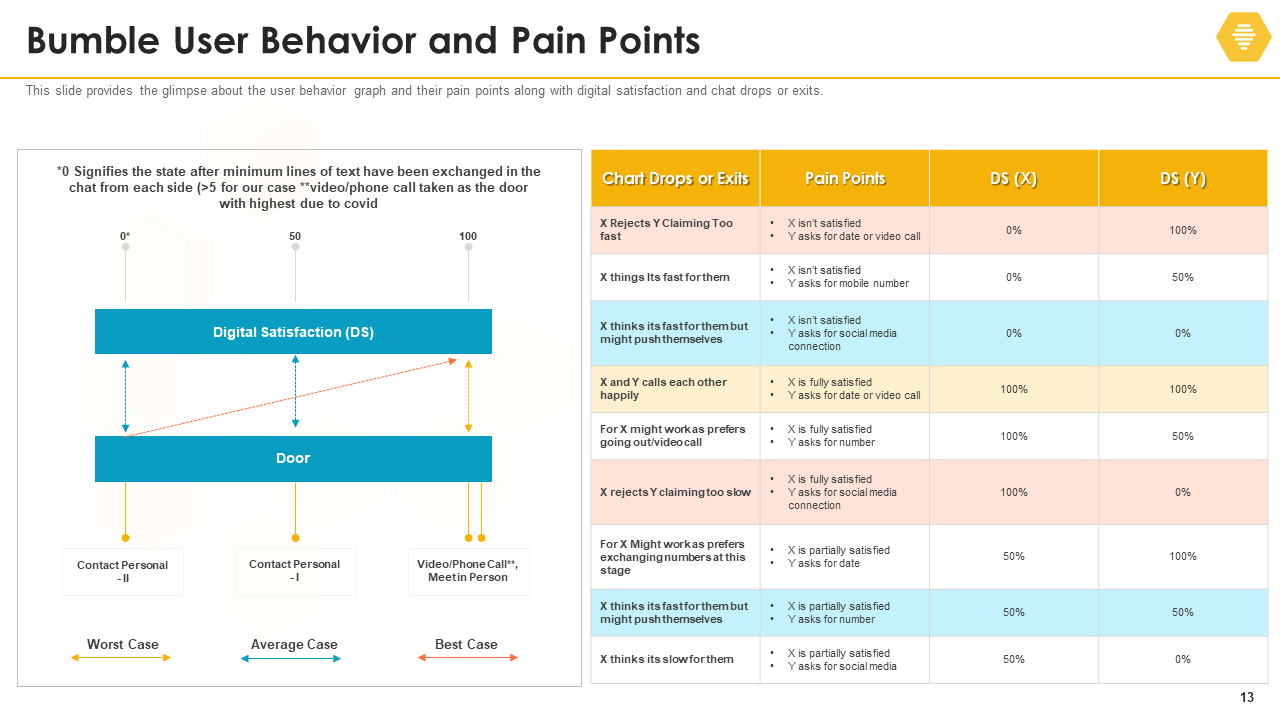

Bumble User Behavior and Pain Points

A company’s strength is in solving their customer’s problems and this can be done if it is well aware of the issue that the user is facing with their application.

Our user behavior and pain points PowerPoint template gives a glimpse for the same in the diagram depicted in the given template.

Bumble has accomplished goals and resolve their users concerns by focusing on the pain points depicted using the table. It also talks about the chat drops and exits along with the digital satisfaction.

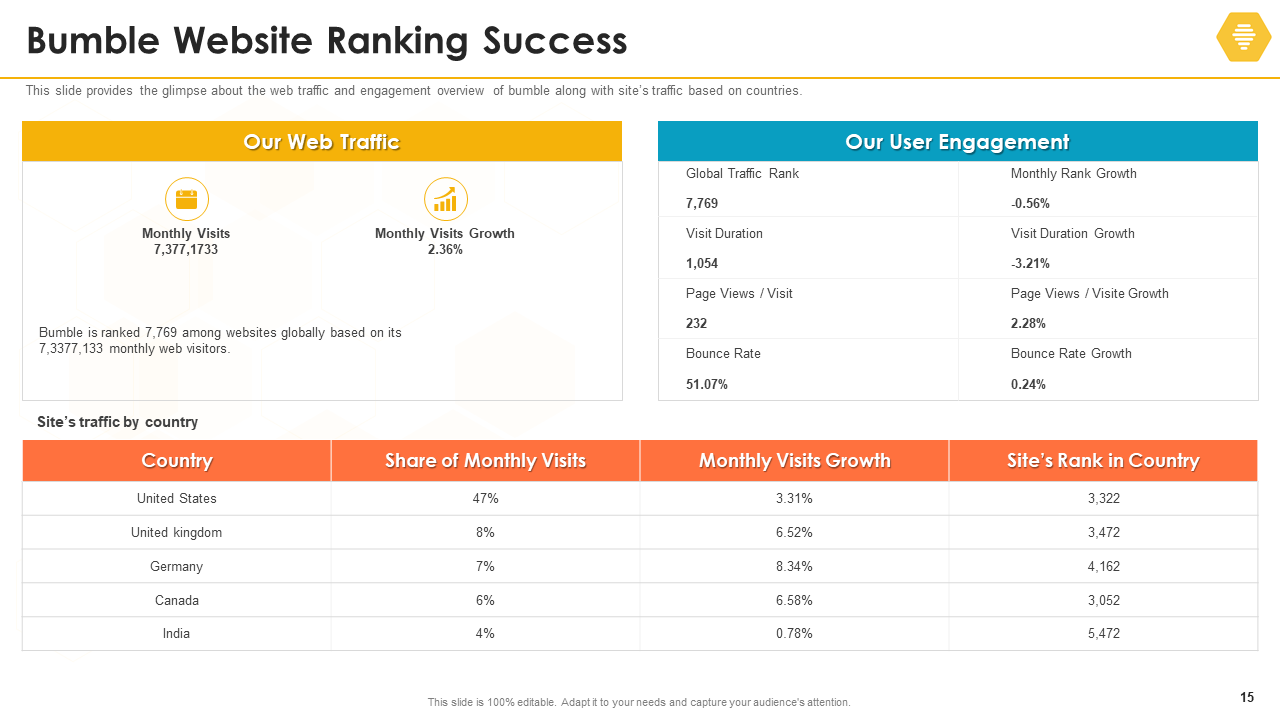

Bumble Website Ranking Success

To survive in the cut throat competition, every company must be aware of its current performance for which it needs a performance metrics.

This website ranking success PowerPoint template is a well-researched slide that is specially designed to entice the investors about the significance of measuring the website performance.

The given template showcases different parameters that should be looked into and provides a glimpse about the website traffic, and user’s engagement . It also incorporates a table depicting site’s traffic based on different countries. By having knowledge of the kind of traffic you are dealing with, you can better utilize it.

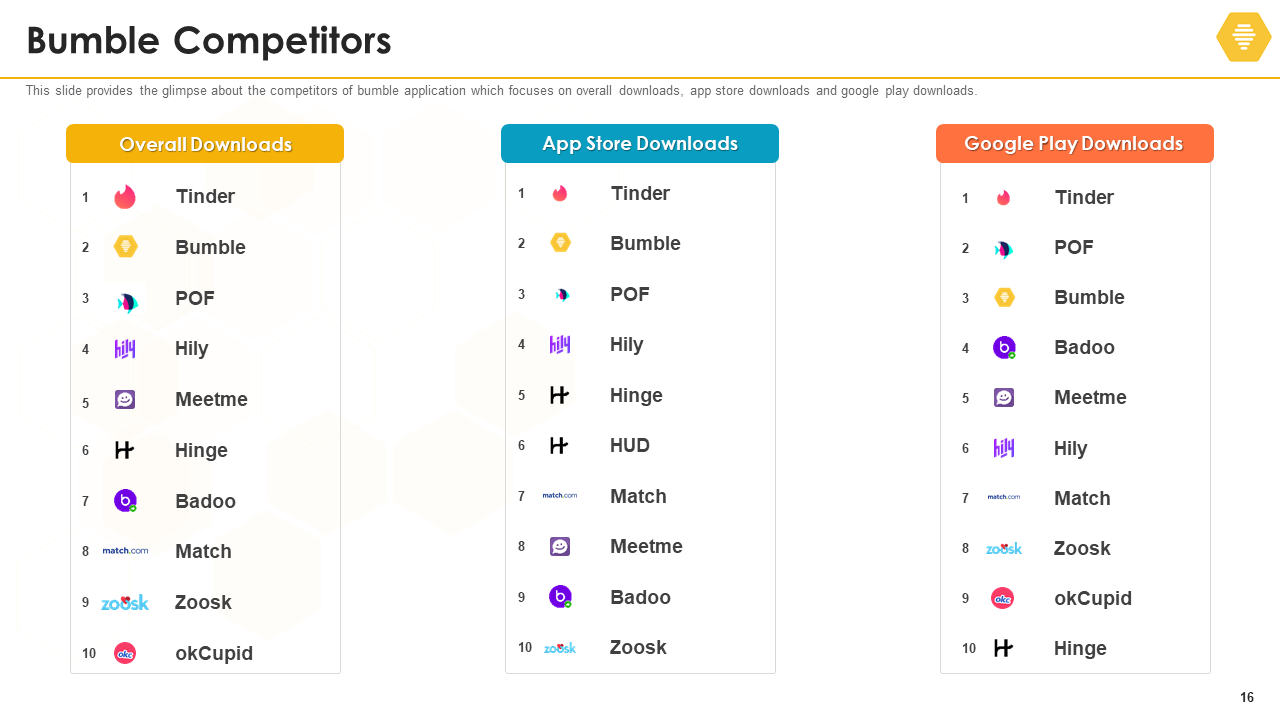

Bumble Competitors

Having a great knowledge of who your competitors are and what do they offer, can help you make your product stand out of the crowd.

This is where this bumble competitors template comes to serve the purpose.

This thoughtful template talks about the app store, google play and overall downloads, which can further arm you in devising such marketing strategies that take advantage from your competitors’ weakness.

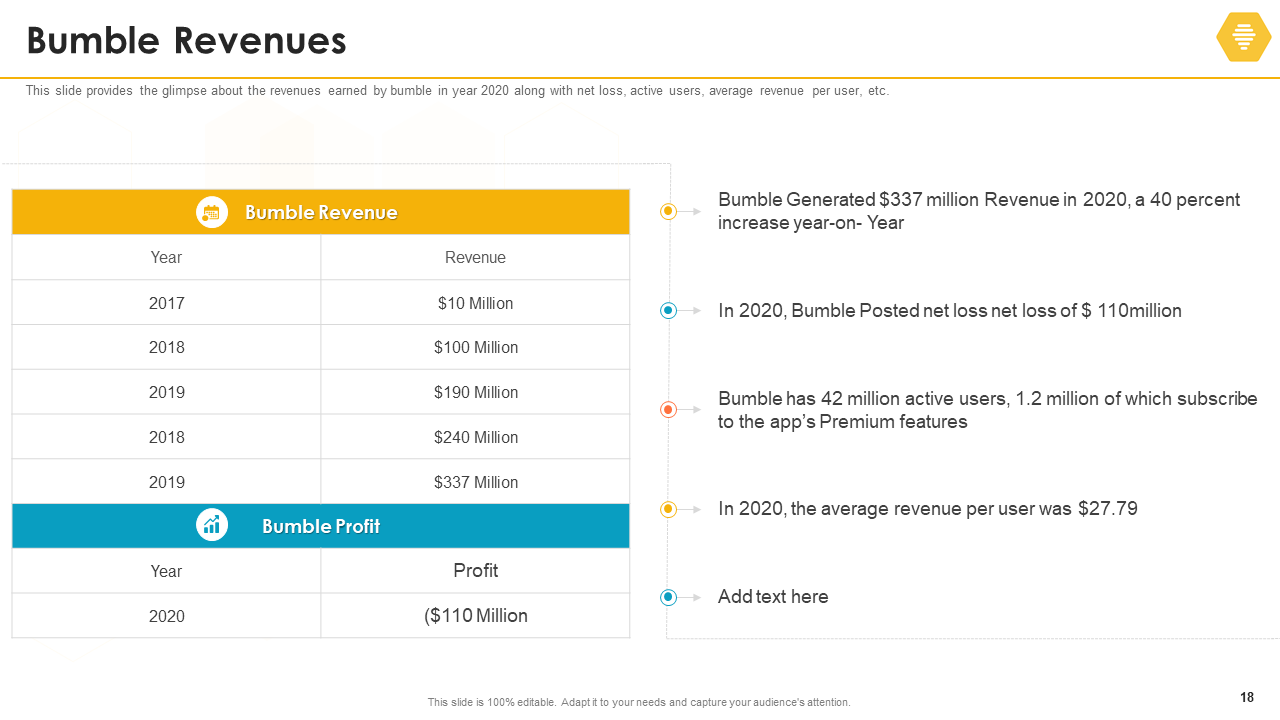

Bumble Revenues

To win the fundraising round, you must provide your investors, the exact stats of your company’s revenue.

This is where we have brought you this R evenue PowerPoint template that shares a glimpse of bumble revenue in different years.

Additionally, it can be used to display the net profit, loss, average revenue per user and active users.

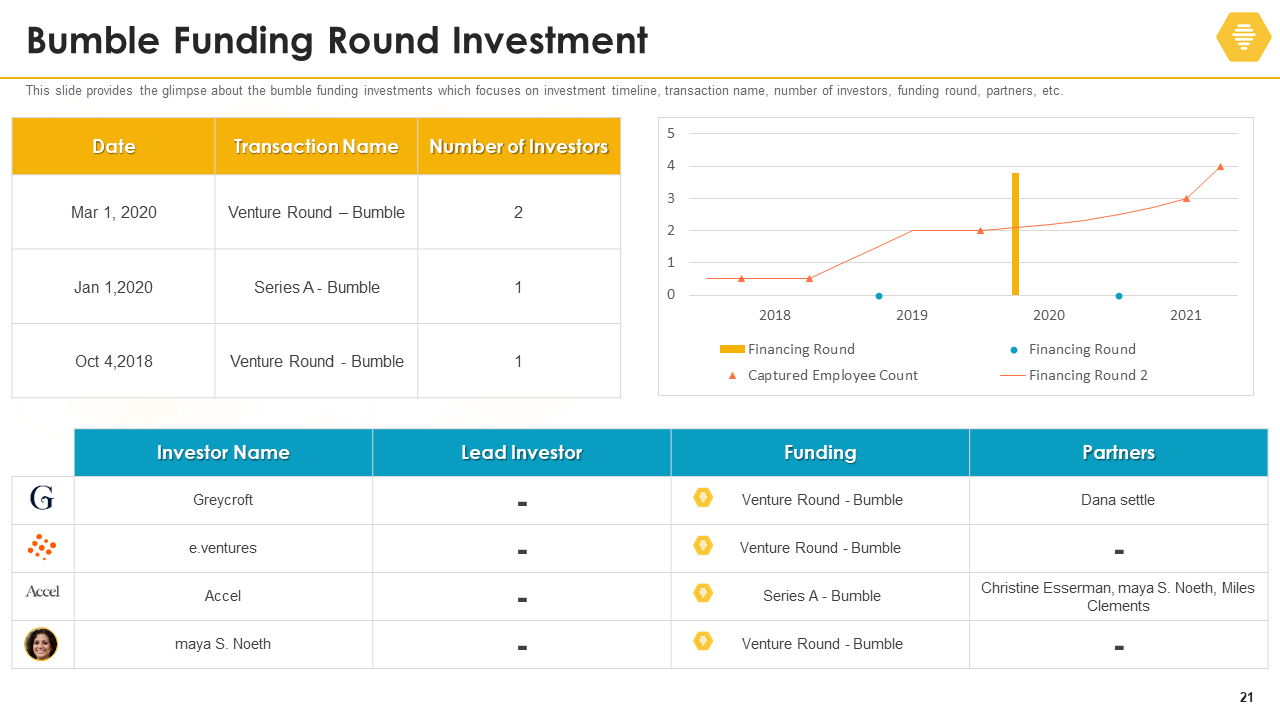

Bumble Funding Round Investment

The slide talks about funding investment round that showcases investment timeline taking the assistance of the line graph.

It incorporates a table that gives a clear picture of investor’s name, lead investor, funding and partners.

Downloading upon this template you can get a succinct idea of the transactions held on the particular dates.

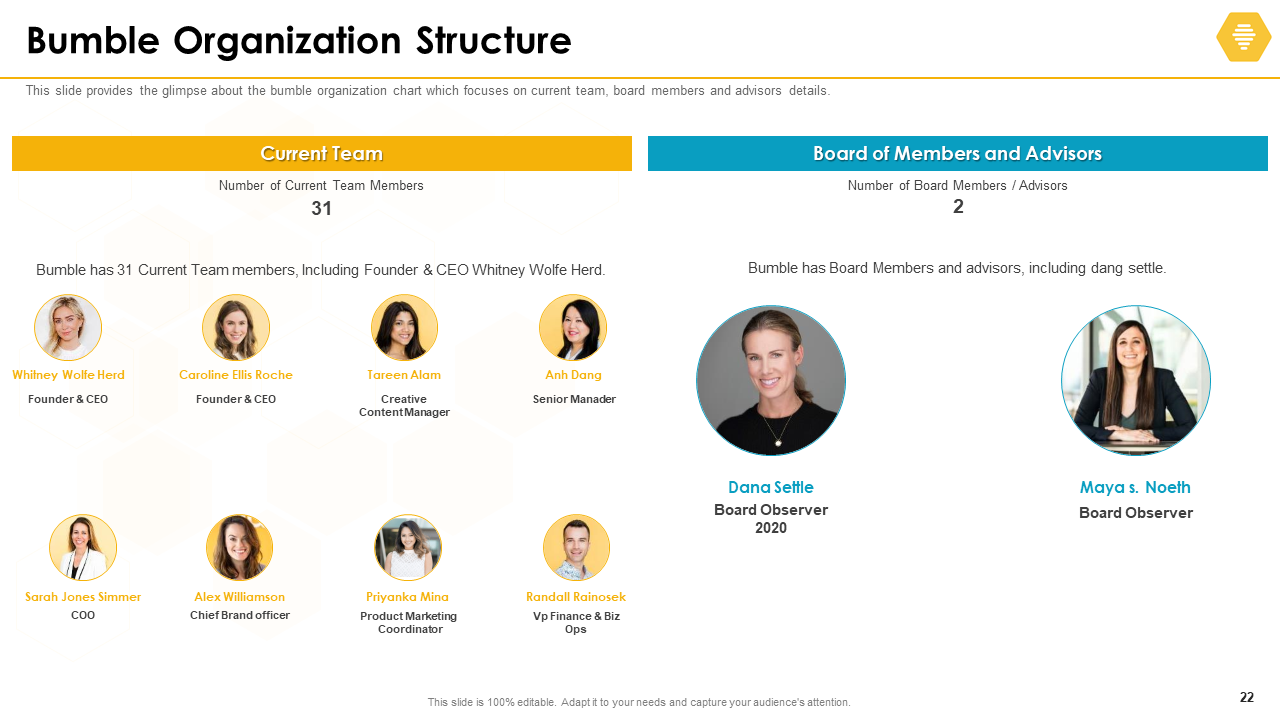

Bumble Organization Structure

Before actually setting up a business, you must have a great idea in place, for which, there is a need to decide the organizational structure of your organization.

Grab this slide to provide a glimpse of the organizational structure. Showcase the faces that are the driving forces behind your organization’s success.

The template gives you enough space to jot down the names of board members and advisors.

Also, you can collectively present your current team members with their designation utilizing this given bumble pitch deck template.

Wrapping Up

If you are planning to create one such dating app, then you are just one click away from your dream plan.

There’s nothing much you need to do to bag this lucrative set of templates for your start-up presentation.

Just sign up for SlideTeam membership and get ready to exercise the liberty of customizing these thoughtful templates as per your start-up plan.

Contact us to book a FREE Demo.

Related posts:

- 14 Schlüsselfolien zum Entwerfen eines Pitch Decks für Dating-Apps wie Bumble

Top 12 Slides on “How to Raise Funds for a Platform Like Spotify”

Drafting a pitch deck taking inspiration from tinder’s legendary investor presentation.

- A Guide to Seed Funding – 21 Best PowerPoint Templates Included!

Liked this blog? Please recommend us

IT Services Pricing Model Templates for Acquiring More Clients!

A Guide to Seed Funding - 21 Best PowerPoint Templates Included!

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA - the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Digital revolution powerpoint presentation slides

Sales funnel results presentation layouts

3d men joinning circular jigsaw puzzles ppt graphics icons

Business Strategic Planning Template For Organizations Powerpoint Presentation Slides

Future plan powerpoint template slide

Project Management Team Powerpoint Presentation Slides

Brand marketing powerpoint presentation slides

Launching a new service powerpoint presentation with slides go to market

Agenda powerpoint slide show

Four key metrics donut chart with percentage

Engineering and technology ppt inspiration example introduction continuous process improvement

Meet our team representing in circular format

Tips for Safer Online Dating and Dating App Use

Online dating and dating apps are powerful connectors in the American dating landscape. In 2023, 30% of Americans used online dating services or apps according to Pew Research Center. As is the case when meeting someone new, whether online or offline, it’s wise to keep a few precautions in mind for safer interactions. Very few dating apps conduct criminal background checks on users, so it’s up to each user to determine if they are comfortable meeting up with someone. And remember that if you do experience sexual violence while dating online or using an app, it is not your fault.

Below are some steps you can take to for safer interaction with others through online dating apps and services—whether you are interacting virtually or in person. We say “safer” because no sexual violence “safety” tip is ever a promise of safety, and the only one responsible for sexual assault is a perpetrator. Full stop.

When Connecting Online

Use different photos for your dating profile. It’s easy to do a reverse image search with Google. If your dating profile has a photo that also shows up on your Instagram or Facebook account, it will be easier for someone to find you on social media.

Avoid sharing live or motion photos. Photos taken in “live” mode include geolocation information that can be passed on along with the photo. Exercise caution when sharing these images with matches and potential dates.

Avoid connecting with suspicious profiles. If the person you matched with has no bio, linked social media accounts, and has only posted one picture, it may be a fake account. It’s important to use caution if you choose to connect with someone you have so little information about.

Check out your potential date on social media. If you know your match’s name or handles on social media—or better yet if you have mutual friends online—look them up and make sure they aren’t “catfishing” you by using a fake social media account to create their dating profile.

Block and report suspicious users. You can block and report another user if you feel their profile is suspicious or if they have acted inappropriately toward you. This can often be done anonymously before or after you’ve matched. As with any personal interaction, it is always possible for people to misrepresent themselves. Trust your instincts about whether you feel someone is representing themself truthfully or not.

The list below offers a few examples of some common stories or suspicious behaviors scammers may use to build trust and sympathy so they can manipulate another user in an unhealthy way.

- Asks for financial assistance in any way, often because of a sudden personal crisis

- Claims to be from the United States but is currently living, working, or traveling abroad

- Claims to be recently widowed with children

- Disappears suddenly from the site then reappears under a different name

- Gives vague answers to specific questions

- Overly complimentary and romantic too early in your communication

- Pressures you to provide your phone number or talk outside the dating app or site

- Requests your home or work address under the guise of sending flowers or gifts

- Tells inconsistent or grandiose stories

- Uses disjointed language and grammar, but has a high level of education

Examples of user behavior you may want to report can include:

- Requests financial assistance

- Requests photographs

- Sends harassing or offensive messages

- Attempts to threaten or intimidate you in any way

- Seems to have created a fake profile

- Tries to sell you products or services

Wait to Share Personal Information. Never give someone you haven’t met with in person your personal information, including your: social security number, credit card details, bank information, or work or home address. Dating apps and websites will never send you an email asking for your username and password information, so if you receive a request for your login information, delete it and consider reporting.

Don’t Respond to Requests for Financial Help. No matter how convincing and compelling someone’s reason may seem, never respond to a request to send money, especially overseas or via wire transfer. If you do get such a request, report it to the app or site you’re using immediately. For more information, check out the U.S. Federal Trade Commission's tips on avoiding online dating scams .

When Meeting in Person

Video chat before you meet up in person. Once you have matched with a potential date and chatted, consider scheduling a video chat with them before meeting up in-person for the first time. This can be a good way to help ensure your match is who they claim to be in their profile. If they strongly resist a video call, that could be a sign of suspicious activity.

Tell a friend where you’re going. Take a screenshot of your date’s profile and send it to a friend. Let at least one friend know where and when you plan to go on your date. If you continue your date in another place you hadn’t planned on, text a friend to let them know your new location. It may also be helpful to arrange to text or call a friend partway through the date or when you get home to check in.

Meet in a public place. For your first date, avoid meeting someone you don’t know well yet in your home, apartment, or workplace. It may make both you and your date feel more comfortable to meet in a coffee shop, restaurant, or bar with plenty of other people around. Avoid meeting in public parks and other isolated locations for first dates.

Don’t rely on your date for transportation. It's important that you are in control of your own transportation to and from the date so that you can leave whenever you want and do not have to rely on your date in case you start feeling uncomfortable. Even if the person you're meeting volunteers to pick you up, avoid getting into a vehicle with someone you don’t know and trust, especially if it’s the first meeting.

Have a few ride share apps downloaded on your phone so in case one is not working when you need it, you’ll have a backup. Make sure you have data on your phone and it’s fully charged, or consider bringing your charger or a portable battery with you.

Stick to what you’re most comfortable with. There’s nothing wrong with having a few drinks on a date. Try to keep your limits in mind and do not feel pressured to drink just because your date is drinking. It can also be a good idea to avoid taking drugs before or during a first date with someone new because drugs could alter your perception of reality or have unexpected interactions with alcohol.

Enlist the help of a bartender or waiter. If you feel uncomfortable in a situation, it can help to find an advocate nearby. You can enlist the help of a waiter or bartender to help you create a distraction, call the police, or get a safe ride home.

Trust your instincts. If you feel uncomfortable, trust your instincts and feel free to leave a date or cut off communication with whoever is making you feel unsafe. Do not worry about feeling rude—your safety is most important, and your date should understand that.

If you felt uncomfortable or unsafe during the date, remember you can always unmatch, block, or report your match after meeting up in person which will keep them from being able to access your profile in the future.

Sexual assault and harassment are never acceptable and are never the victim’s fault no matter what you were wearing, drinking, or whom you were with. The National Sexual Assault Hotline (800.656.HOPE and online.rainn.org ) is here to listen and provide resources, and is anonymous, free, and available 24/7.

Eight out of 10 sexual assaults are committed by someone who knows the victim.

Your next birthday can help survivors of sexual violence..

Got any suggestions?

We want to hear from you! Send us a message and help improve Slidesgo

Top searches

Trending searches

17 templates

9 templates

tropical rainforest

29 templates

summer vacation

19 templates

islamic history

36 templates

american history

70 templates

Dating Wrapped Trend in Social Media

Dating wrapped trend in social media presentation, free google slides theme, powerpoint template, and canva presentation template.

Are you a fan of dating? It can be in restaurants, cinemas, parks, night clubs or any other place, there’s always a fun activity to do when meeting someone new! But what’s even better is speaking all about it afterwards! If you have some funny stories from dating experiences and want to tell the world, try creating a fun dating wrapped to share on your social media! Where did you meet these people? How did it end up? What are your preferences? What do you get out of all this? Write everything down in this romantic template with many hearts and narrate your dating life!

Features of this template

- 100% editable and easy to modify

- 25 different slides to impress your audience

- Contains easy-to-edit graphics such as graphs, maps, tables, timelines and mockups

- Includes 500+ icons and Flaticon’s extension for customizing your slides

- Designed to be used in Google Slides, Canva, and Microsoft PowerPoint

- 16:9 widescreen format suitable for all types of screens

- Includes information about fonts, colors, and credits of the resources used

How can I use the template?

Am I free to use the templates?

How to attribute?

Attribution required If you are a free user, you must attribute Slidesgo by keeping the slide where the credits appear. How to attribute?

Related posts on our blog.

How to Add, Duplicate, Move, Delete or Hide Slides in Google Slides

How to Change Layouts in PowerPoint

How to Change the Slide Size in Google Slides

Related presentations.

Premium template

Unlock this template and gain unlimited access

Register for free and start editing online

- Search Menu

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Why Submit?

- About Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication

- About International Communication Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, literature review, acknowledgments, about the authors.

- < Previous

Managing Impressions Online: Self-Presentation Processes in the Online Dating Environment

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Nicole Ellison, Rebecca Heino, Jennifer Gibbs, Managing Impressions Online: Self-Presentation Processes in the Online Dating Environment, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , Volume 11, Issue 2, 1 January 2006, Pages 415–441, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00020.x

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This study investigates self-presentation strategies among online dating participants, exploring how participants manage their online presentation of self in order to accomplish the goal of finding a romantic partner. Thirty-four individuals active on a large online dating site participated in telephone interviews about their online dating experiences and perceptions. Qualitative data analysis suggests that participants attended to small cues online, mediated the tension between impression management pressures and the desire to present an authentic sense of self through tactics such as creating a profile that reflected their “ideal self,” and attempted to establish the veracity of their identity claims. This study provides empirical support for Social Information Processing theory in a naturalistic context while offering insight into the complicated way in which “honesty” is enacted online.

The online dating arena represents an opportunity to document changing cultural norms surrounding technology-mediated relationship formation and to gain insight into important aspects of online behavior, such as impression formation and self-presentation strategies. Mixed-mode relationships, wherein people first meet online and then move offline, challenge established theories that focus on exclusively online relationships and provide opportunities for new theory development ( Walther & Parks, 2002 ). Although previous research has explored relationship development and self-presentation online ( Bargh, McKenna, & Fitzsimons, 2002; McLaughlin, Osbourne, & Ellison, 1997; Parks & Floyd, 1996; Roberts & Parks, 1999; Utz, 2000 ), the online dating forum is qualitatively different from many other online settings due to the anticipation of face-to-face interaction inherent in this context ( Gibbs, Ellison, & Heino, 2006 ) and the fact that social practices are still nascent.

In recent years, the use of online dating or online personals services has evolved from a marginal to a mainstream social practice. In 2003, at least 29 million Americans (two out of five singles) used an online dating service ( Gershberg, 2004 ); in 2004, on average, there were 40 million unique visitors to online dating sites each month in the U.S. ( CBC News, 2004 ). In fact, the online personals category is one of the most lucrative forms of paid content on the web in the United States ( Egan, 2003 ) and the online dating market is expected to reach $642 million in 2008 ( Greenspan, 2003 ). Ubiquitous access to the Internet, the diminished social stigma associated with online dating, and the affordable cost of Internet matchmaking services contribute to the increasingly common perception that online dating is a viable, efficient way to meet dating or long-term relationship partners ( St. John, 2002 ). Mediated matchmaking is certainly not a new phenomenon: Newspaper personal advertisements have existed since the mid-19th century ( Schaefer, 2003 ) and video dating was popular in the 1980s ( Woll & Cosby, 1987; Woll & Young, 1989 ). Although scholars working in a variety of academic disciplines have studied these earlier forms of mediated matchmaking (e.g., Ahuvia & Adelman, 1992; Lynn & Bolig, 1985; Woll, 1986; Woll & Cosby, 1987 ), current Internet dating services are substantively different from these incarnations due to their larger user base and more sophisticated self-presentation options.

Contemporary theoretical perspectives allow us to advance our understanding of how the age-old process of mate-finding is transformed through online strategies and behaviors. For instance, Social Information Processing (SIP) theory and other frameworks help illuminate computer-mediated communication (CMC), interpersonal communication, and impression management processes. This article focuses on the ways in which CMC interactants manage their online self-presentation and contributes to our knowledge of these processes by examining these issues in the naturalistic context of online dating, using qualitative data gathered from in-depth interviews with online dating participants.

In contrast to a technologically deterministic perspective that focuses on the characteristics of the technologies themselves, or a socially deterministic approach that privileges user behavior, this article reflects a social shaping perspective. Social shaping of technology approaches ( Dutton, 1996; MacKenzie & Wajcman, 1985; Woolgar, 1996 ) acknowledge the ways in which information and communication technologies (ICTs) both shape and are shaped by social practices. As Dutton points out, “technologies can open, close, and otherwise shape social choices, although not always in the ways expected on the basis of rationally extrapolating from the perceived properties of technology” (1996, p. 9). One specific framework that reflects this approach is Howard’s (2004) embedded media perspective, which acknowledges both the capacities and the constraints of ICTs. Capacities are those aspects of technology that enhance our ability to connect with one another, enact change, and so forth; constraints are those aspects of technology that hinder our ability to achieve these goals. An important aspect of technology use, which is mentioned but not explicitly highlighted in Howard’s framework, is the notion of circumvention , which describes the specific strategies employed by individuals to exploit the capacities and minimize the constraints associated with their use of ICTs. Although the notion of circumvention is certainly not new to CMC researchers, this article seeks to highlight the importance of circumvention practices when studying the social aspects of technology use. 1

Self-Presentation and Self-Disclosure in Online and Offline Contexts

Self-presentation and self-disclosure processes are important aspects of relational development in offline settings ( Taylor & Altman, 1987 ), especially in early stages. Goffman’s work on self-presentation explicates the ways in which an individual may engage in strategic activities “to convey an impression to others which it is in his interests to convey” (1959, p. 4). These impression-management behaviors consist of expressions given (communication in the traditional sense, e.g., spoken communication) and expressions given off (presumably unintentional communication, such as nonverbal communication cues). Self-presentation strategies are especially important during relationship initiation, as others will use this information to decide whether to pursue a relationship ( Derlega, Winstead, Wong, & Greenspan, 1987 ). Research suggests that when individuals expect to meet a potential dating partner for the first time, they will alter their self-presentational behavior in accordance with the values desired by the prospective date ( Rowatt, Cunningham, & Druen, 1998 ). Even when interacting with strangers, individuals tend to engage in self-enhancement ( Schlenker & Pontari, 2000 ).

However, research suggests that pressures to highlight one’s positive attributes are experienced in tandem with the need to present one’s true (or authentic) self to others, especially in significant relationships. Intimacy in relationships is linked to feeling understood by one’s partner ( Reis & Shaver, 1988 ) and develops “through a dynamic process whereby an individual discloses personal information, thoughts, and feelings to a partner; receives a response from the partner; and interprets that response as understanding, validating, and caring” ( Laurenceau, Barrett, & Pietromonaco, 1998 , p. 1238). Therefore, if participants aspire to an intimate relationship, their desire to feel understood by their interaction partners will motivate self-disclosures that are open and honest as opposed to deceptive. This tension between authenticity and impression management is inherent in many aspects of self-disclosure. In making decisions about what and when to self-disclose, individuals often struggle to reconcile opposing needs such as openness and autonomy ( Greene, Derlega, & Mathews, 2006 ).

Interactants in online environments experience these same pressures and desires, but the greater control over self-presentational behavior in CMC allows individuals to manage their online interactions more strategically. Due to the asynchronous nature of CMC, and the fact that CMC emphasizes verbal and linguistic cues over less controllable nonverbal communication cues, online self-presentation is more malleable and subject to self-censorship than face-to-face self-presentation ( Walther, 1996 ). In Goffman’s (1959) terms, more expressions of self are “given” rather than “given off.” This greater control over self-presentation does not necessarily lead to misrepresentation online. Due to the “passing stranger” effect ( Rubin, 1975 ) and the visual anonymity present in CMC ( Joinson, 2001 ), under certain conditions the online medium may enable participants to express themselves more openly and honestly than in face-to-face contexts.

A commonly accepted understanding of identity presumes that there are multiple aspects of the self which are expressed or made salient in different contexts. Higgins (1987) argues there are three domains of the self: the actual self (attributes an individual possesses), the ideal self (attributes an individual would ideally possess), and the ought self (attributes an individual ought to possess); discrepancies between one’s actual and ideal self are linked to feelings of dejection. Klohnen and Mendelsohn (1998) determined that individuals’ descriptions of their “ideal self” influenced perceptions of their romantic partners in the direction of their ideal self-conceptions. Bargh et al. (2002) found that in comparison to face-to-face interactions, Internet interactions allowed individuals to better express aspects of their true selves—aspects of themselves that they wanted to express but felt unable to. The relative anonymity of online interactions and the lack of a shared social network online may allow individuals to reveal potentially negative aspects of the self online ( Bargh et al., 2002 ).

Although self-presentation in personal web sites has been examined ( Dominick, 1999; Schau & Gilly, 2003 ), the realm of online dating has not been studied as extensively (for exceptions, see Baker, 2002; Fiore & Donath, 2004 ), and this constitutes a gap in the current research on online self-presentation and disclosure. The online dating realm differs from other CMC environments in crucial ways that may affect self-presentational strategies. For instance, the anticipated future face-to-face interaction inherent in most online dating interactions may diminish participants’ sense of visual anonymity, an important variable in many online self-disclosure studies. An empirical study of online dating participants found that those who anticipated greater face-to-face interaction did feel that they were more open in their disclosures, and did not suppress negative aspects of the self ( Gibbs et al., 2006 ). In addition, because the goal of many online dating participants is an intimate relationship, these individuals may be more motivated to engage in authentic self-disclosures.

Credibility Assessment and Demonstration in Online Self-Presentation

Misrepresentation in online environments.

As discussed, online environments offer individuals an increased ability to control their self-presentation, and therefore greater opportunities to engage in misrepresentation ( Cornwell & Lundgren, 2001 ). Concerns about the prospect of online deception are common ( Bowker & Tuffin, 2003; Donath, 1999; Donn & Sherman, 2002 ), and narratives about identity deception have been reproduced in both academic and popular outlets ( Joinson & Dietz-Uhler, 2002; Stone, 1996; Van Gelder, 1996 ). Some theorists argue that CMC gives participants more freedom to explore playful, fantastical online personae that differ from their “real life” identities ( Stone, 1996 ; Turkle, 1995 ). In certain online settings, such as online role-playing games, a schism between one’s online representation and one’s offline identity are inconsequential, even expected. For instance, MacKinnon (1995) notes that among Usenet participants it is common practice to “forget” about the relationship between actual identities and online personae.

The online dating environment is different, however, because participants are typically seeking an intimate relationship and therefore desire agreement between others’ online identity claims and offline identities. Online dating participants report that deception is the “main perceived disadvantage of online dating” ( Brym & Lenton, 2001 , p. 3) and see it as commonplace: A survey of one online dating site’s participants found that 86% felt others misrepresented their physical appearance ( Gibbs et al., 2006 ). A 2001 research study found that over a quarter of online dating participants reported misrepresenting some aspect of their identity, most commonly age (14%), marital status (10%), and appearance (10%) ( Brym & Lenton, 2001 ). Perceptions that others are lying may encourage reciprocal deception, because users will exaggerate to the extent that they feel others are exaggerating or deceiving ( Fiore & Donath, 2004 ). Concerns about deception in this setting have spawned related services that help online daters uncover inaccuracies in others’ representations and run background checks on would-be suitors ( Baertlein, 2004 ; Fernandez, 2005 ). One site, True.com , conducts background checks on their users and has worked to introduce legislation that would force other online dating sites to either conduct background checks on their users or display a disclaimer ( Lee, 2004 ).

The majority of online dating participants claim they are truthful ( Gibbs et al., 2006; Brym & Lenton, 2001 ), and research suggests that some of the technical and social aspects of online dating may discourage deceptive communication. For instance, anticipation of face-to-face communication influences self-representation choices ( Walther, 1994 ) and self-disclosures because individuals will more closely monitor their disclosures as the perceived probability of future face-to-face interaction increases ( Berger, 1979 ) and will engage in more intentional or deliberate self-disclosure ( Gibbs et al., 2006 ). Additionally, Hancock, Thom-Santelli, and Ritchie (2004) note that the design features of a medium may affect lying behaviors, and that the use of recorded media (in which messages are archived in some fashion, such as an online dating profile) will discourage lying. Also, online dating participants are typically seeking a romantic partner, which may lower their motivation for misrepresentation compared to other online relationships. Further, Cornwell and Lundgren (2001) found that individuals involved in online romantic relationships were more likely to engage in misrepresentation than those involved in face-to-face romantic relationships, but that this was directly related to the level of involvement. That is, respondents were less involved in their cyberspace relationships and therefore more likely to engage in misrepresentation. This lack of involvement is less likely in relationships started in an online dating forum, especially sites that promote marriage as a goal.

Public perceptions about the higher incidence of deception online are also contradicted by research that suggests that lying is a typical occurrence in everyday offline life ( DePaulo, Kashy, Kirkendol, Wyer, & Epstein, 1996 ), including situations in which people are trying to impress prospective dates ( Rowatt et al., 1998 ). Additionally, empirical data about the true extent of misrepresentation in this context is lacking. The current literature relies on self-reported data, and therefore offers only limited insight into the extent to which misrepresentation may be occurring. Hitsch, Hortacsu, and Ariely (2004) use creative techniques to address this issue, such as comparing participants’ self-reported characteristics to patterns found in national survey data, but no research to date has attempted to validate participants’ self-reported assessments of the honesty of their self-descriptions.

Assessing and Demonstrating Credibility in CMC

The potential for misrepresentation online, combined with the time and effort invested in face-to-face dates, make assessment strategies critical for online daters. These assessment strategies may then influence participants’ self-presentational strategies as they seek to prove their trustworthiness while simultaneously assessing the credibility of others.

Online dating participants operate in an environment in which assessing the identity of others is a complex and evolving process of reading signals and deconstructing cues, using both active and passive strategies ( Berger, 1979; Ramirez, Walther, Burgoon, & Sunnafrank, 2002; Tidwell & Walther, 2002 ). SIP considers how Internet users develop impressions of others, even with the limited cues available online, and suggests that interactants will adapt to the remaining cues in order to make decisions about others ( Walther, 1992; Walther, Anderson, & Park, 1994 ). Online users look to small cues in order to develop impressions of others, such as a poster’s email address ( Donath, 1999 ), the links on a person’s homepage ( Kibby, 1997 ), even the timing of email messages ( Walther & Tidwell, 1995 ). In expressing affinity, CMC users are adept at using language ( Walther, Loh, & Granka, 2005 ) and CMC-specific conventions, especially as they become more experienced online ( Utz, 2000 ). In short, online users become cognitive misers, forming impressions of others while conserving mental energy ( Wallace, 1999 ).

Walther and Parks (2002) propose the concept of “warranting” as a useful conceptual tool for understanding how users validate others’ online identity cues (see also Stone, 1996 ). The connection, or warrant, between one’s self-reported online persona and one’s offline aspects of self is less certain and more mutable than in face-to-face settings ( Walther & Parks, 2002 ). In online settings, users will look for signals that are difficult to mimic or govern in order to assess others’ identity claims ( Donath, 1999 ). For instance, individuals might use search engines to locate newsgroup postings by the person under scrutiny, knowing that this searching is covert and that the newsgroup postings most likely were authored without the realization that they would be archived ( Ramirez et al., 2002 ). In the context of online dating, because of the perceptions of deception that characterize this sphere and the self-reported nature of individuals’ profiles, participants may adopt specific presentation strategies geared towards providing warrants for their identity claims.

In light of the above, our research question is thus:

RQ: How do online dating participants manage their online presentation of self in order to accomplish the goal of finding a romantic partner?

In order to gain insight into this question, we interviewed online dating participants about their experiences, thoughts, and behaviors. The qualitative data reported in this article were collected as part of a larger research project which surveyed a national random sample of users of a large online dating site (N = 349) about relational goals, honesty and self-disclosure, and perceived success in online dating. The survey findings are reported in Gibbs et al. (2006) .

Research Site

Our study addresses contemporary CMC theory using naturalistic observations. Participants were members of a large online dating service, “ Connect.com ” (a pseudonym). Connect.com currently has 15 million active members in more than 200 countries around the world and shares structural characteristics with many other online dating services, offering users the ability to create profiles, search others’ profiles, and communicate via a manufactured email address. In their profiles, participants may include one or more photographs and a written (open-ended) description of themselves and their desired mate. They also answer a battery of closed-ended questions, with preset category-based answers, about descriptors such as income, body type, religion, marital status, and alcohol usage. Users can conduct database searches that generate a list of profiles that match their desired parameters (usually gender, sexual orientation, age, and location). Initial communication occurs through a double-blind email system, in which both email addresses are masked, and participants usually move from this medium to others as the relationship progresses.

Data Collection

Given the relative lack of prior research on the phenomenon of online dating, we used qualitative methods to explore the diverse ways in which participants understood and made sense of their experience ( Berger & Luckman, 1980 ) through their own rich descriptions and explanations ( Miles & Huberman, 1994 ). We took an inductive approach based on general research questions informed by literature on online self-presentation and relationship formation rather than preset hypotheses. In addition to asking about participants’ backgrounds, the interview protocol included open-ended questions about their online dating history and goals, profile construction, honesty and self-disclosure online, criteria used to assess others online, and relationship development. Interviews were semistructured to ensure that all participants were asked certain questions and to encourage participants to raise other issues they felt were relevant to the research. The protocol included questions such as: “How did you decide what to say about yourself in your profile? Are you trying to convey a certain impression of yourself with your profile? If you showed your profile to one of your close friends, what do you think their response would be? Are there any personal characteristics that you avoided mentioning or tried to deemphasize?” (The full protocol is available from the authors.)

As recommended for qualitative research ( Eisenhardt, 1989; Glaser & Strauss, 1967 ), we employed theoretical sampling rather than random sampling. In theoretical sampling, cases are chosen based on theoretical (developed a priori) categories to provide examples of polar types, rather than for statistical generalizability to a larger population ( Eisenhardt, 1989 ). The Director of Market Research at Connect.com initially contacted a subsample of members in the Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay areas, inviting them to participate in an interview and offering them a free one-month subscription to Connect.com in return. Those members who did not respond within a week received a reminder email. Of those contacted, 76 people volunteered to participate in an interview. Out of these 76 volunteers, we selected and scheduled interviews with 36 (although two were unable to participate due to scheduling issues). We chose interview participants to ensure a good mix on each of our theoretical categories: gender, age, urban/rural, income, and ethnicity. We focused exclusively on those seeking relationships with the opposite sex, as this group constitutes the majority of Connect.com users. We also confirmed that they were active participants in the site by ensuring that their last login date was within the past week and checking that each had a profile.

Fifty percent of our participants were female and 50% were male, with 76% from an urban location in Los Angeles and 24% from a more rural area surrounding the town of Modesto in the central valley of California. Participants’ ages ranged from 25 to 70, with most being in their 30s and 40s. Their online dating experience varied from 1 month to 5 years. Although our goal was to sample a mix of participants who varied on key demographic criteria rather than generalizing to a larger population, our sample is in fact reflective of the demographic characteristics of the larger population of Connect.com ’s subscribers. Thirty-four interviews were conducted in June and July 2003. Interviews were conducted by telephone, averaging 45 minutes and ranging from 30 to 90 minutes in length. The interview database consisted of 551 pages, including 223,001 words, with an average of 6559 words per interview.

Data Analysis