An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.12(6); 2020 Jun

Social Media Use and Its Connection to Mental Health: A Systematic Review

Fazida karim.

1 Psychology, California Institute of Behavioral Neurosciences and Psychology, Fairfield, USA

2 Business & Management, University Sultan Zainal Abidin, Terengganu, MYS

Azeezat A Oyewande

3 Family Medicine, California Institute of Behavioral Neurosciences and Psychology, Fairfield, USA

4 Family Medicine, Lagos State Health Service Commission/Alimosho General Hospital, Lagos, NGA

Lamis F Abdalla

5 Internal Medicine, California Institute of Behavioral Neurosciences and Psychology, Fairfield, USA

Reem Chaudhry Ehsanullah

Safeera khan.

Social media are responsible for aggravating mental health problems. This systematic study summarizes the effects of social network usage on mental health. Fifty papers were shortlisted from google scholar databases, and after the application of various inclusion and exclusion criteria, 16 papers were chosen and all papers were evaluated for quality. Eight papers were cross-sectional studies, three were longitudinal studies, two were qualitative studies, and others were systematic reviews. Findings were classified into two outcomes of mental health: anxiety and depression. Social media activity such as time spent to have a positive effect on the mental health domain. However, due to the cross-sectional design and methodological limitations of sampling, there are considerable differences. The structure of social media influences on mental health needs to be further analyzed through qualitative research and vertical cohort studies.

Introduction and background

Human beings are social creatures that require the companionship of others to make progress in life. Thus, being socially connected with other people can relieve stress, anxiety, and sadness, but lack of social connection can pose serious risks to mental health [ 1 ].

Social media

Social media has recently become part of people's daily activities; many of them spend hours each day on Messenger, Instagram, Facebook, and other popular social media. Thus, many researchers and scholars study the impact of social media and applications on various aspects of people’s lives [ 2 ]. Moreover, the number of social media users worldwide in 2019 is 3.484 billion, up 9% year-on-year [ 3 - 5 ]. A statistic in Figure 1 shows the gender distribution of social media audiences worldwide as of January 2020, sorted by platform. It was found that only 38% of Twitter users were male but 61% were using Snapchat. In contrast, females were more likely to use LinkedIn and Facebook. There is no denying that social media has now become an important part of many people's lives. Social media has many positive and enjoyable benefits, but it can also lead to mental health problems. Previous research found that age did not have an effect but gender did; females were much more likely to experience mental health than males [ 6 , 7 ].

Impact on mental health

Mental health is defined as a state of well-being in which people understand their abilities, solve everyday life problems, work well, and make a significant contribution to the lives of their communities [ 8 ]. There is debated presently going on regarding the benefits and negative impacts of social media on mental health [ 9 , 10 ]. Social networking is a crucial element in protecting our mental health. Both the quantity and quality of social relationships affect mental health, health behavior, physical health, and mortality risk [ 9 ]. The Displaced Behavior Theory may help explain why social media shows a connection with mental health. According to the theory, people who spend more time in sedentary behaviors such as social media use have less time for face-to-face social interaction, both of which have been proven to be protective against mental disorders [ 11 , 12 ]. On the other hand, social theories found how social media use affects mental health by influencing how people view, maintain, and interact with their social network [ 13 ]. A number of studies have been conducted on the impacts of social media, and it has been indicated that the prolonged use of social media platforms such as Facebook may be related to negative signs and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress [ 10 - 15 ]. Furthermore, social media can create a lot of pressure to create the stereotype that others want to see and also being as popular as others.

The need for a systematic review

Systematic studies can quantitatively and qualitatively identify, aggregate, and evaluate all accessible data to generate a warm and accurate response to the research questions involved [ 4 ]. In addition, many existing systematic studies related to mental health studies have been conducted worldwide. However, only a limited number of studies are integrated with social media and conducted in the context of social science because the available literature heavily focused on medical science [ 6 ]. Because social media is a relatively new phenomenon, the potential links between their use and mental health have not been widely investigated.

This paper attempt to systematically review all the relevant literature with the aim of filling the gap by examining social media impact on mental health, which is sedentary behavior, which, if in excess, raises the risk of health problems [ 7 , 9 , 12 ]. This study is important because it provides information on the extent of the focus of peer review literature, which can assist the researchers in delivering a prospect with the aim of understanding the future attention related to climate change strategies that require scholarly attention. This study is very useful because it provides information on the extent to which peer review literature can assist researchers in presenting prospects with a view to understanding future concerns related to mental health strategies that require scientific attention. The development of the current systematic review is based on the main research question: how does social media affect mental health?

Research strategy

The research was conducted to identify studies analyzing the role of social media on mental health. Google Scholar was used as our main database to find the relevant articles. Keywords that were used for the search were: (1) “social media”, (2) “mental health”, (3) “social media” AND “mental health”, (4) “social networking” AND “mental health”, and (5) “social networking” OR “social media” AND “mental health” (Table 1 ).

Out of the results in Table 1 , a total of 50 articles relevant to the research question were selected. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, duplicate papers were removed, and, finally, a total of 28 articles were selected for review (Figure 2 ).

PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Peer-reviewed, full-text research papers from the past five years were included in the review. All selected articles were in English language and any non-peer-reviewed and duplicate papers were excluded from finally selected articles.

Of the 16 selected research papers, there were a research focus on adults, gender, and preadolescents [ 10 - 19 ]. In the design, there were qualitative and quantitative studies [ 15 , 16 ]. There were three systematic reviews and one thematic analysis that explored the better or worse of using social media among adolescents [ 20 - 23 ]. In addition, eight were cross-sectional studies and only three were longitudinal studies [ 24 - 29 ].The meta-analyses included studies published beyond the last five years in this population. Table 2 presents a selection of studies from the review.

IGU, internet gaming disorder; PSMU, problematic social media use

This study has attempted to systematically analyze the existing literature on the effect of social media use on mental health. Although the results of the study were not completely consistent, this review found a general association between social media use and mental health issues. Although there is positive evidence for a link between social media and mental health, the opposite has been reported.

For example, a previous study found no relationship between the amount of time spent on social media and depression or between social media-related activities, such as the number of online friends and the number of “selfies”, and depression [ 29 ]. Similarly, Neira and Barber found that while higher investment in social media (e.g. active social media use) predicted adolescents’ depressive symptoms, no relationship was found between the frequency of social media use and depressed mood [ 28 ].

In the 16 studies, anxiety and depression were the most commonly measured outcome. The prominent risk factors for anxiety and depression emerging from this study comprised time spent, activity, and addiction to social media. In today's world, anxiety is one of the basic mental health problems. People liked and commented on their uploaded photos and videos. In today's age, everyone is immune to the social media context. Some teens experience anxiety from social media related to fear of loss, which causes teens to try to respond and check all their friends' messages and messages on a regular basis.

On the contrary, depression is one of the unintended significances of unnecessary use of social media. In detail, depression is limited not only to Facebooks but also to other social networking sites, which causes psychological problems. A new study found that individuals who are involved in social media, games, texts, mobile phones, etc. are more likely to experience depression.

The previous study found a 70% increase in self-reported depressive symptoms among the group using social media. The other social media influence that causes depression is sexual fun [ 12 ]. The intimacy fun happens when social media promotes putting on a facade that highlights the fun and excitement but does not tell us much about where we are struggling in our daily lives at a deeper level [ 28 ]. Another study revealed that depression and time spent on Facebook by adolescents are positively correlated [ 22 ]. More importantly, symptoms of major depression have been found among the individuals who spent most of their time in online activities and performing image management on social networking sites [ 14 ].

Another study assessed gender differences in associations between social media use and mental health. Females were found to be more addicted to social media as compared with males [ 26 ]. Passive activity in social media use such as reading posts is more strongly associated with depression than doing active use like making posts [ 23 ]. Other important findings of this review suggest that other factors such as interpersonal trust and family functioning may have a greater influence on the symptoms of depression than the frequency of social media use [ 28 , 29 ].

Limitation and suggestion

The limitations and suggestions were identified by the evidence involved in the study and review process. Previously, 7 of the 16 studies were cross-sectional and slightly failed to determine the causal relationship between the variables of interest. Given the evidence from cross-sectional studies, it is not possible to conclude that the use of social networks causes mental health problems. Only three longitudinal studies examined the causal relationship between social media and mental health, which is hard to examine if the mental health problem appeared more pronounced in those who use social media more compared with those who use it less or do not use at all [ 19 , 20 , 24 ]. Next, despite the fact that the proposed relationship between social media and mental health is complex, a few studies investigated mediating factors that may contribute or exacerbate this relationship. Further investigations are required to clarify the underlying factors that help examine why social media has a negative impact on some peoples’ mental health, whereas it has no or positive effect on others’ mental health.

Conclusions

Social media is a new study that is rapidly growing and gaining popularity. Thus, there are many unexplored and unexpected constructive answers associated with it. Lately, studies have found that using social media platforms can have a detrimental effect on the psychological health of its users. However, the extent to which the use of social media impacts the public is yet to be determined. This systematic review has found that social media envy can affect the level of anxiety and depression in individuals. In addition, other potential causes of anxiety and depression have been identified, which require further exploration.

The importance of such findings is to facilitate further research on social media and mental health. In addition, the information obtained from this study can be helpful not only to medical professionals but also to social science research. The findings of this study suggest that potential causal factors from social media can be considered when cooperating with patients who have been diagnosed with anxiety or depression. Also, if the results from this study were used to explore more relationships with another construct, this could potentially enhance the findings to reduce anxiety and depression rates and prevent suicide rates from occurring.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 01 July 2020

The effect of social media on well-being differs from adolescent to adolescent

- Ine Beyens ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7023-867X 1 ,

- J. Loes Pouwels ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9586-392X 1 ,

- Irene I. van Driel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7810-9677 1 ,

- Loes Keijsers ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8580-6000 2 &

- Patti M. Valkenburg ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0477-8429 1

Scientific Reports volume 10 , Article number: 10763 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

117k Accesses

198 Citations

122 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

The question whether social media use benefits or undermines adolescents’ well-being is an important societal concern. Previous empirical studies have mostly established across-the-board effects among (sub)populations of adolescents. As a result, it is still an open question whether the effects are unique for each individual adolescent. We sampled adolescents’ experiences six times per day for one week to quantify differences in their susceptibility to the effects of social media on their momentary affective well-being. Rigorous analyses of 2,155 real-time assessments showed that the association between social media use and affective well-being differs strongly across adolescents: While 44% did not feel better or worse after passive social media use, 46% felt better, and 10% felt worse. Our results imply that person-specific effects can no longer be ignored in research, as well as in prevention and intervention programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Some socially poor but also some socially rich adolescents feel closer to their friends after using social media

J. Loes Pouwels, Patti M. Valkenburg, … Loes Keijsers

Associations between youth’s daily social media use and well-being are mediated by upward comparisons

Andrea Irmer & Florian Schmiedek

Variation in social media sensitivity across people and contexts

Sumer S. Vaid, Lara Kroencke, … Gabriella M. Harari

Introduction

Ever since the introduction of social media, such as Facebook and Instagram, researchers have been studying whether the use of such media may affect adolescents’ well-being. These studies have typically reported mixed findings, yielding either small negative, small positive, or no effects of the time spent using social media on different indicators of well-being, such as life satisfaction and depressive symptoms (for recent reviews, see for example 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ). Most of these studies have focused on between-person associations, examining whether adolescents who use social media more (or less) often than their peers experience lower (or higher) levels of well-being than these peers. While such between-person studies are valuable in their own right, several scholars 6 , 7 have recently called for studies that investigate within-person associations to understand whether an increase in an adolescent’s social media use is associated with an increase or decrease in that adolescent’s well-being. The current study aims to respond to this call by investigating associations between social media use and well-being within single adolescents across multiple points in time 8 , 9 , 10 .

Person-specific effects

To our knowledge, four recent studies have investigated within-person associations of social media use with different indicators of adolescent well-being (i.e., life satisfaction, depression), again with mixed results 6 , 11 , 12 , 13 . Orben and colleagues 6 found a small negative reciprocal within-person association between the time spent using social media and life satisfaction. Likewise, Boers and colleagues 12 found a small within-person association between social media use and increased depressive symptoms. Finally, Coyne and colleagues 11 and Jensen and colleagues 13 did not find any evidence for within-person associations between social media use and depression.

Earlier studies that investigated within-person associations of social media use with indicators of well-being have all only reported average effect sizes. However, it is possible, or even plausible, that these average within-person effects may have been small and nonsignificant because they result from sizeable heterogeneity in adolescents’ susceptibility to the effects of social media use on well-being (see 14 , 15 ). After all, an average within-person effect size can be considered an aggregate of numerous individual within-person effect sizes that range from highly positive to highly negative.

Some within-person studies have sought to understand adolescents’ differential susceptibility to the effects of social media by investigating differences between subgroups. For instance, they have investigated the moderating role of sex to compare the effects of social media on boys versus girls 6 , 11 . However, such a group-differential approach, in which potential differences in susceptibility are conceptualized by group-level moderators (e.g., gender, age) does not provide insights into more fine-grained differences at the level of the single individual 16 . After all, while girls and boys each represent a homogenous group in terms of sex, they may each differ on a wide array of other factors.

As such, although worthwhile, the average within-person effects of social media on well-being obtained in previous studies may have been small or non-significant because they are diluted across a highly heterogeneous population (or sub-population) of adolescents 14 , 15 . In line with the proposition of media effects theories that each adolescent may have a unique susceptibility to the effects of social media 17 , a viable explanation for the small and inconsistent findings in earlier studies may be that the effect of social media differs from adolescent to adolescent. The aim of the current study is to investigate this hypothesis and to obtain a better understanding of adolescents’ unique susceptibility to the effects of social media on their affective well-being.

Social media and affective well-being

Within-person studies have provided important insights into the associations of social media use with cognitive well-being (e.g., life satisfaction 6 ), which refers to adolescents’ cognitive judgment of how satisfied they are with their life 18 . However, the associations of social media use with adolescents’ affective well-being (i.e., adolescents’ affective evaluations of their moods and emotions 18 ) are still unknown. In addition, while earlier within-person studies have focused on associations with trait-like conceptualizations of well-being 11 , 12 , 13 , that is, adolescents’ average well-being across specific time periods 18 , there is a lack of studies that focus on well-being as a momentary affective state. Therefore, we extend previous research by examining the association between adolescents’ social media use and their momentary affective well-being. Like earlier experience sampling (ESM) studies among adults 19 , 20 , we measured adolescents’ momentary affective well-being with a single item. Adolescents’ momentary affective well-being was defined as their current feelings of happiness, a commonly used question to measure well-being 21 , 22 , which has high convergent validity, as evidenced by the strong correlations with the presence of positive affect and absence of negative affect.

To assess adolescents’ momentary affective well-being (henceforth referred to as well-being), we conducted a week-long ESM study among 63 middle adolescents ages 14 and 15. Six times a day, adolescents were asked to complete a survey using their own mobile phone, covering 42 assessments per adolescent, assessing their affective well-being and social media use. In total, adolescents completed 2,155 assessments (83.2% average compliance).

We focused on middle adolescence, since this is the period in life characterized by most significant fluctuations in well-being 23 , 24 . Also, in comparison to early and late adolescents, middle adolescents are more sensitive to reactions from peers and have a strong tendency to compare themselves with others on social media and beyond. Because middle adolescents typically use different social media platforms, in a complementary way 25 , 26 , 27 , each adolescent reported on his/her use of the three social media platforms that s/he used most frequently out of the five most popular social media platforms among adolescents: WhatsApp, followed by Instagram, Snapchat, YouTube, and, finally, the chat function of games 28 . In addition to investigating the association between overall social media use and well-being (i.e., the summed use of adolescents’ three most frequently used platforms), we examined the unique associations of the two most popular platforms, WhatsApp and Instagram 28 .

Like previous studies on social media use and well-being, we distinguished between active social media use (i.e., “activities that facilitate direct exchanges with others” 29 ) and passive social media use (i.e., “consuming information without direct exchanges” 29 ). Within-person studies among young adults have shown that passive but not active social media use predicts decreases in well-being 29 . Therefore, we examined the unique associations of adolescents’ overall active and passive social media use with their well-being, as well as active and passive use of Instagram and WhatsApp, specifically. We investigated categorical associations, that is, whether adolescents would feel better or worse if they had actively or passively used social media. And we investigated dose–response associations to understand whether adolescents’ well-being would change as a function of the time they had spent actively or passively using social media.

The hypotheses and the design, sampling and analysis plan were preregistered prior to data collection and are available on the Open Science Framework, along with the code used in the analyses ( https://osf.io/nhks2 ). For details about the design of the study and analysis approach, see Methods.

In more than half of all assessments (68.17%), adolescents had used social media (i.e., one or more of their three favorite social media platforms), either in an active or passive way. Instagram (50.90%) and WhatsApp (53.52%) were used in half of all assessments. Passive use of social media (66.21% of all assessments) was more common than active use (50.86%), both on Instagram (48.48% vs. 20.79%) and WhatsApp (51.25% vs. 40.07%).

Strong positive between-person correlations were found between the duration of active and passive social media use (overall: r = 0.69, p < 0.001; Instagram: r = 0.38, p < 0.01; WhatsApp: r = 0.85, p < 0.001): Adolescents who had spent more time actively using social media than their peers, had also spent more time passively using social media than their peers. Likewise, strong positive within-person correlations were found between the duration of active and passive social media use (overall: r = 0.63, p < 0.001; Instagram: r = 0.37, p < 0.001; WhatsApp: r = 0.57, p < 0.001): The more time an adolescent had spent actively using social media at a certain moment, the more time s/he had also spent passively using social media at that moment.

Table 1 displays the average number of minutes that adolescents had spent using social media in the past hour at each assessment, and the zero-order between- and within-person correlations between the duration of social media use and well-being. At the between-person level, the duration of active and passive social media use was not associated with well-being: Adolescents who had spent more time actively or passively using social media than their peers did not report significantly higher or lower levels of well-being than their peers. At the within-person level, significant but weak positive correlations were found between the duration of active and passive overall social media use and well-being. This indicates that adolescents felt somewhat better at moments when they had spent more time actively or passively using social media (overall), compared to moments when they had spent less time actively or passively using social media. When looking at specific platforms, a positive correlation was only found for passive WhatsApp use, but not for active WhatsApp use, and not for active and passive Instagram use.

Average and person-specific effects

The within-person associations of social media use with well-being and differences in these associations were tested in a series of multilevel models. We ran separate models for overall social media use (i.e., active use and passive use of adolescents’ three favorite social media platforms, see Table 2 ), Instagram use (see Table 3 ), and WhatsApp use (see Table 4 ). In a first step we examined the average categorical associations for each of these three social media uses using fixed effects models (Models 1A, 3A, and 5A) to investigate whether, on average, adolescents would feel better or worse at moments when they had used social media compared to moments when they had not (i.e., categorical predictors: active use versus no active use, and passive use versus no passive use). In a second step, we examined heterogeneity in the within-person categorical associations by adding random slopes to the fixed effects models (Models 1B, 3B, and 5B). Next, we examined the average dose–response associations using fixed effects models (Models 2A, 4A, and 6A), to investigate whether, on average, adolescents would feel better or worse when they had spent more time using social media (i.e., continuous predictors: duration of active use and duration of passive use). Finally, we examined heterogeneity in the within-person dose–response associations by adding random slopes to the fixed effects models (Models 2B, 4B, and 6B).

Overall social media use.

The model with the categorical predictors (see Table 2 ; Model 1A) showed that, on average, there was no association between overall use and well-being: Adolescents’ well-being did not increase or decrease at moments when they had used social media, either in a passive or active way. However, evidence was found that the association of passive (but not active) social media use with well-being differed from adolescent to adolescent (Model 1B), with effect sizes ranging from − 0.24 to 0.68. For 44.26% of the adolescents the association was non-existent to small (− 0.10 < r < 0.10). However, for 45.90% of the adolescents there was a weak (0.10 < r < 0.20; 8.20%), moderate (0.20 < r < 0.30; 22.95%) or even strong positive ( r ≥ 0.30; 14.75%) association between overall passive social media use and well-being, and for almost one in ten (9.84%) adolescents there was a weak (− 0.20 < r < − 0.10; 6.56%) or moderate negative (− 0.30 < r < − 0.20; 3.28%) association.

The model with continuous predictors (Model 2A) showed that, on average, there was a significant dose–response association for active use. At moments when adolescents had used social media, the time they spent actively (but not passively) using social media was positively associated with well-being: Adolescents felt better at moments when they had spent more time sending messages, posting, or sharing something on social media. The associations of the time spent actively and passively using social media with well-being did not differ across adolescents (Model 2B).

Instagram use

As shown in Model 3A in Table 3 , on average, there was a significant categorical association between passive (but not active) Instagram use and well-being: Adolescents experienced an increase in well-being at moments when they had passively used Instagram (i.e., viewing posts/stories of others). Adolescents did not experience an increase or decrease in well-being when they had actively used Instagram. The associations of passive and active Instagram use with well-being did not differ across adolescents (Model 3B).

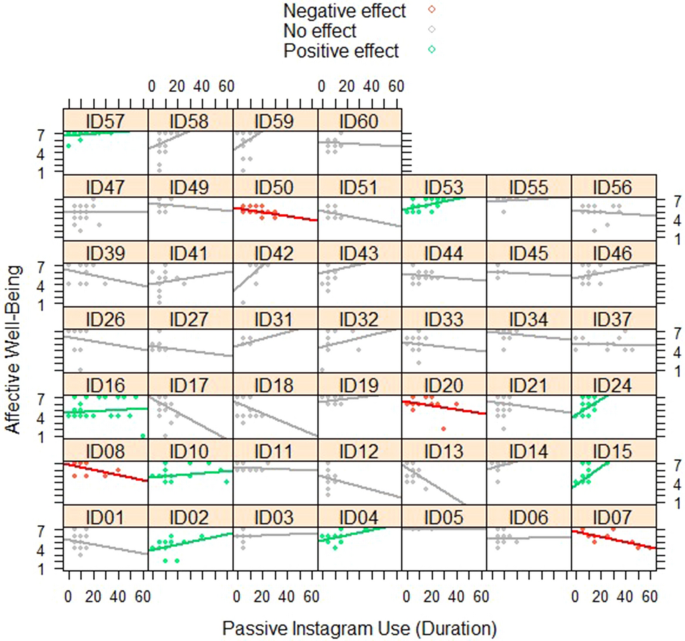

On average, no significant dose–response association was found for Instagram use (Model 4A): At moments when adolescents had used Instagram, the time adolescents spent using Instagram (either actively or passively) was not associated with their well-being. However, evidence was found that the association of the time spent passively using Instagram differed from adolescent to adolescent (Model 4B), with effect sizes ranging from − 0.48 to 0.27. For most adolescents (73.91%) the association was non-existent to small (− 0.10 < r < 0.10), but for almost one in five adolescents (17.39%) there was a weak (0.10 < r < 0.20; 10.87%) or moderate (0.20 < r < 0.30; 6.52%) positive association, and for almost one in ten adolescents (8.70%) there was a weak (− 0.20 < r < − 0.10; 2.17%), moderate (− 0.30 < r < − 0.20; 4.35%), or strong ( r ≤ − 0.30; 2.17%) negative association. Figure 1 illustrates these differences in the dose–response associations.

The dose–response association between passive Instagram use (in minutes per hour) and affective well-being for each individual adolescent (n = 46). Red lines represent significant negative within-person associations, green lines represent significant positive within-person associations, and gray lines represent non-significant within-person associations. A graph was created for each participant who had completed at least 10 assessments. A total of 13 participants were excluded because they had completed less than 10 assessments of passive Instagram use. In addition, one participant was excluded because no graph could be computed, since this participant's passive Instagram use was constant across assessments.

WhatsApp use

As shown in Model 5A in Table 4 , just as for Instagram, we found that, on average, there was a significant categorical association between passive (but not active) WhatsApp use and well-being: Adolescents reported that they felt better at moments when they had passively used WhatsApp (i.e., read WhatsApp messages). For active WhatsApp use, no significant association was found. Also, in line with the results for Instagram use, no differences were found regarding the associations of active and passive WhatsApp use (Model 5B).

In addition, a significant dose–response association was found for passive (but not active) use (Model 6A). At moments when adolescents had used WhatsApp, we found that, on average, the time adolescents spent passively using WhatsApp was positively associated with well-being: Adolescents felt better at moments when they had spent more time reading WhatsApp messages. The time spent actively using WhatsApp was not associated with well-being. No differences were found in the dose–response associations of active and passive WhatsApp use (Model 6B).

This preregistered study investigated adolescents’ unique susceptibility to the effects of social media. We found that the associations of passive (but not active) social media use with well-being differed substantially from adolescent to adolescent, with effect sizes ranging from moderately negative (− 0.24) to strongly positive (0.68). While 44.26% of adolescents did not feel better or worse if they had passively used social media, 45.90% felt better, and a small group felt worse (9.84%). In addition, for Instagram the majority of adolescents (73.91%) did not feel better or worse when they had spent more time viewing post or stories of others, whereas some felt better (17.39%), and others (8.70%) felt worse.

These findings have important implications for social media effects research, and media effects research more generally. For decades, researchers have argued that people differ in their susceptibility to the effects of media 17 , leading to numerous investigations of such differential susceptibility. These investigations have typically focused on moderators, based on variables such as sex, age, or personality. Yet, over the years, studies have shown that such moderators appear to have little power to explain how individuals differ in their susceptibility to media effects, probably because a group-differential approach does not account for the possibility that media users may differ across a range of factors, that are not captured by only one (or a few) investigated moderator variables.

By providing insights into each individual’s unique susceptibility, the findings of this study provide an explanation as to why, up until now, most media effects research has only found small effects. We found that the majority of adolescents do not experience any short-term changes in well-being related to their social media use. And if they do experience any changes, these are more often positive than negative. Because only small subsets of adolescents experience small to moderate changes in well-being, the true effects of social media reported in previous studies have probably been diluted across heterogeneous samples of individuals that differ in their susceptibility to media effects (also see 30 ). Several scholars have noted that overall effect sizes may mask more subtle individual differences 14 , 15 , which may explain why previous studies have typically reported small or no effects of social media on well-being or indicators of well-being 6 , 11 , 12 , 13 . The current study seems to confirm this assumption, by showing that while the overall effect sizes are small at best, the person-specific effect sizes vary considerably, from tiny and small to moderate and strong.

As called upon by other scholars 5 , 31 , we disentangled the associations of active and passive use of social media. Research among young adults found that passive (but not active) social media use is associated with lower levels of affective well-being 29 . In line with these findings, the current study shows that active and passive use yielded different associations with adolescents’ affective well-being. Interestingly though, in contrast to previous findings among adults, our study showed that, on average, passive use of Instagram and WhatsApp seemed to enhance rather than decrease adolescents’ well-being. This discrepancy in findings may be attributed to the fact that different mechanisms might be involved. Verduyn and colleagues 29 found that passive use of Facebook undermines adults’ well-being by enhancing envy, which may also explain the decreases in well-being found in our study among a small group of adolescents. Yet, adolescents who felt better by passively using Instagram and WhatsApp, might have felt so because they experienced enjoyment. After all, adolescents often seek positive content on social media, such as humorous posts or memes 32 . Also, research has shown that adolescents mainly receive positive feedback on social media 33 . Hence, their passive Instagram and WhatsApp use may involve the reading of positive feedback, which may explain the increases in well-being.

Overall, the time spent passively using WhatsApp improved adolescents’ well-being. This did not differ from adolescent to adolescent. However, the associations of the time spent passively using Instagram with well-being did differ from adolescent to adolescent. This discrepancy suggests that not all social media uses yield person-specific effects on well-being. A possible explanation may be that adolescents’ responses to WhatsApp are more homogenous than those to Instagram. WhatsApp is a more private platform, which is mostly used for one-to-one communication with friends and acquaintances 26 . Instagram, in contrast, is a more public platform, which allows its users to follow a diverse set of people, ranging from best friends to singers, actors, and influencers 28 , and to engage in intimate communication as well as self-presentation and social comparison. Such diverse uses could lead to more varied, or even opposing responses, such as envy versus inspiration.

Limitations and directions for future research

The current study extends our understanding of differential susceptibility to media effects, by revealing that the effect of social media use on well-being differs from adolescent to adolescent. The findings confirm our assumption that among the great majority of adolescents, social media use is unrelated to well-being, but that among a small subset, social media use is either related to decreases or increases in well-being. It must be noted, however, that participants in this study felt relatively happy, overall. Studies with more vulnerable samples, consisting of clinical samples or youth with lower social-emotional well-being may elicit different patterns of effects 27 . Also, the current study focused on affective well-being, operationalized as happiness. It is plausible that social media use relates differently with other types of well-being, such as cognitive well-being. An important next step is to identify which adolescents are particularly susceptible to experience declines in well-being. It is conceivable, for instance, that the few adolescents who feel worse when they use social media are the ones who receive negative feedback on social media 33 .

In addition, future ESM studies into the effects of social media should attempt to include one or more follow-up measures to improve our knowledge of the longer-term influence of social media use on affective well-being. While a week-long ESM is very common and applied in most earlier ESM studies 34 , a week is only a snapshot of adolescent development. Research is needed that investigates whether the associations of social media use with adolescents’ momentary affective well-being may cumulate into long-lasting consequences. Such investigations could help clarify whether adolescents who feel bad in the short term would experience more negative consequences in the long term, and whether adolescents who feel better would be more resistant to developing long-term negative consequences. And while most adolescents do not seem to experience any short-term increases or decreases in well-being, more research is needed to investigate whether these adolescents may experience a longer-term impact of social media.

While the use of different platforms may be differently associated with well-being, different types of use may also yield different effects. Although the current study distinguished between active and passive use of social media, future research should further differentiate between different activities. For instance, because passive use entails many different activities, from reading private messages (e.g., WhatsApp messages, direct messages on Instagram) to browsing a public feed (e.g., scrolling through posts on Instagram), research is needed that explores the unique effects of passive public use and passive private use. Research that seeks to explore the nuances in adolescents’ susceptibility as well as the nuances in their social media use may truly improve our understanding of the effects of social media use.

Participants

Participants were recruited via a secondary school in the south of the Netherlands. Our preregistered sampling plan set a target sample size of 100 adolescents. We invited adolescents from six classrooms to participate in the study. The final sample consisted of 63 adolescents (i.e., 42% consent rate, which is comparable to other ESM studies among adolescents; see, for instance 35 , 36 ). Informed consent was obtained from all participants and their parents. On average, participants were 15 years old ( M = 15.12 years, SD = 0.51) and 54% were girls. All participants self-identified as Dutch, and 41.3% were enrolled in the prevocational secondary education track, 25.4% in the intermediate general secondary education track, and 33.3% in the academic preparatory education track.

The study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Amsterdam and was performed in accordance with the guidelines formulated by the Ethics Review Board. The study consisted of two phases: A baseline survey and a personalized week-long experience sampling (ESM) study. In phase 1, researchers visited the school during school hours. Researchers informed the participants of the objective and procedure of the study and assured them that their responses would be treated confidentially. Participants were asked to sign the consent form. Next, participants completed a 15-min baseline survey. The baseline survey included questions about demographics and assessed which social media each adolescent used most frequently, allowing to personalize the social media questions presented during the ESM study in phase 2. After completing the baseline survey, participants were provided detailed instructions about phase 2.

In phase 2, which took place two and a half weeks after the baseline survey, a 7-day ESM study was conducted, following the guidelines for ESM studies provided by van Roekel and colleagues 34 . Aiming for at least 30 assessments per participant and based on an average compliance rate of 70 to 80% reported in earlier ESM studies among adolescents 34 , we asked each participant to complete a total of 42 ESM surveys (i.e., six 2-min surveys per day). Participants completed the surveys using their own mobile phone, on which the ESM software application Ethica Data was installed during the instruction session with the researchers (phase 1). Each 2-min survey consisted of 22 questions, which assessed adolescents’ well-being and social media use. Two open-ended questions were added to the final survey of the day, which asked about adolescents’ most pleasant and most unpleasant events of the day.

The ESM sampling scheme was semi-random, to allow for randomization and avoid structural patterns in well-being, while taking into account that adolescents were not allowed to use their phone during school time. The Ethica Data app was programmed to generate six beep notifications per day at random time points within a fixed time interval that was tailored to the school’s schedule: before school time (1 beep), during school breaks (2 beeps), and after school time (3 beeps). During the weekend, the beeps were generated during the morning (1 beep), afternoon (3 beeps), and evening (2 beeps). To maximize compliance, a 30-min time window was provided to complete each survey. This time window was extended to one hour for the first survey (morning) and two hours for the final survey (evening) to account for travel time to school and time spent on evening activities. The average compliance rate was 83.2%. A total of 2,155 ESM assessments were collected: Participants completed an average of 34.83 surveys ( SD = 4.91) on a total of 42 surveys, which is high compared to previous ESM studies among adolescents 34 .

The questions of the ESM study were personalized based on the responses to the baseline survey. During the ESM study, each participant reported on his/her use of three different social media platforms: WhatsApp and either Instagram, Snapchat, YouTube, and/or the chat function of games (i.e., the most popular social media platforms among adolescents 28 ). Questions about Instagram and WhatsApp use were only included if the participant had indicated in the baseline survey that s/he used these platforms at least once a week. If a participant had indicated that s/he used Instagram or WhatsApp (or both) less than once a week, s/he was asked to report on the use of Snapchat, YouTube, or the chat function of games, depending on what platform s/he used at least once a week. In addition to Instagram and WhatsApp, questions were asked about a third platform, that was selected based on how frequently the participant used Snapchat, YouTube, or the chat function of games (i.e., at least once a week). This resulted in five different combinations of three platforms: Instagram, WhatsApp, and Snapchat (47 participants); Instagram, WhatsApp, and YouTube (11 participants); Instagram, WhatsApp, and chatting via games (2 participants); WhatsApp, Snapchat, and YouTube (1 participant); and WhatsApp, YouTube, and chatting via games (2 participants).

Frequency of social media use

In the baseline survey, participants were asked to indicate how often they used and checked Instagram, WhatsApp, Snapchat, YouTube, and the chat function of games, using response options ranging from 1 ( never ) to 7 ( more than 12 times per day ). These platforms are the five most popular platforms among Dutch 14- and 15-year-olds 28 . Participants’ responses were used to select the three social media platforms that were assessed in the personalized ESM study.

Duration of social media use

In the ESM study, duration of active and passive social media use was measured by asking participants how much time in the past hour they had spent actively and passively using each of the three platforms that were included in the personalized ESM surveys. Response options ranged from 0 to 60 min , with 5-min intervals. To measure active Instagram use, participants indicated how much time in the past hour they had spent (a) “posting on your feed or sharing something in your story on Instagram” and (b) “sending direct messages/chatting on Instagram.” These two items were summed to create the variable duration of active Instagram use. Sum scores exceeding 60 min (only 0.52% of all assessments) were recoded to 60 min. To measure duration of passive Instagram use, participants indicated how much time in the past hour they had spent “viewing posts/stories of others on Instagram.” To measure the use of WhatsApp, Snapchat, YouTube and game-based chatting, we asked participants how much time they had spent “sending WhatsApp messages” (active use) and “reading WhatsApp messages” (passive use); “sending snaps/messages or sharing something in your story on Snapchat” (active use) and “viewing snaps/stories/messages from others on Snapchat” (passive use); “posting YouTube clips” (active use) and “watching YouTube clips” (passive use); “sending messages via the chat function of a game/games” (active use) and “reading messages via the chat function of a game/games” (passive use). Duration of active and passive overall social media use were created by summing the responses across the three social media platforms for active and passive use, respectively. Sum scores exceeding 60 min (2.13% of all assessments for active overall use; 2.90% for passive overall use) were recoded to 60 min. The duration variables were used to investigate whether the time spent actively or passively using social media was associated with well-being (dose–response associations).

Use/no use of social media

Based on the duration variables, we created six dummy variables, one for active and one for passive overall social media use, one for active and one for passive Instagram use, and one for active and one for passive WhatsApp use (0 = no active use and 1 = active use , and 0 = no passive use and 1 = passive use , respectively). These dummy variables were used to investigate whether the use of social media, irrespective of the duration of use, was associated with well-being (categorical associations).

Consistent with previous ESM studies 19 , 20 , we measured affective well-being using one item, asking “How happy do you feel right now?” at each assessment. Adolescents indicated their response to the question using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 ( not at all ) to 7 ( completely ), with 4 ( a little ) as the midpoint. Convergent validity of this item was established in a separate pilot ESM study among 30 adolescents conducted by the research team of the fourth author: The affective well-being item was strongly correlated with the presence of positive affect and absence of negative affect (assessed by a 10-item positive and negative affect schedule for children; PANAS-C) at both the between-person (positive affect: r = 0.88, p < 0.001; negative affect: r = − 0.62, p < 0.001) and within-person level (positive affect: r = 0.74, p < 0.001; negative affect: r = − 0.58, p < 0.001).

Statistical analyses

Before conducting the analyses, several validation checks were performed (see 34 ). First, we aimed to only include participants in the analyses who had completed more than 33% of all ESM assessments (i.e., at least 14 assessments). Next, we screened participants’ responses to the open questions for unserious responses (e.g., gross comments, jokes). And finally, we inspected time series plots for patterns in answering tendencies. Since all participants completed more than 33% of all ESM assessments, and no inappropriate responses or low-quality data patterns were detected, all participants were included in the analyses.

Following our preregistered analysis plan, we tested the proposed associations in a series of multilevel models. Before doing so, we tested the homoscedasticity and linearity assumptions for multilevel analyses 37 . Inspection of standardized residual plots indicated that the data met these assumptions (plots are available on OSF at https://osf.io/nhks2 ). We specified separate models for overall social media use, use of Instagram, and use of WhatsApp. To investigate to what extent adolescents’ well-being would vary depending on whether they had actively or passively used social media/Instagram/WhatsApp or not during the past hour (categorical associations), we tested models including the dummy variables as predictors (active use versus no active use, and passive use versus no passive use; models 1, 3, and 5). To investigate whether, at moments when adolescents had used social media/Instagram/WhatsApp during the past hour, their well-being would vary depending on the duration of social media/Instagram/WhatsApp use (dose–response associations), we tested models including the duration variables as predictors (duration of active use and duration of passive use; models 2, 4, and 6). In order to avoid negative skew in the duration variables, we only included assessments during which adolescents had used social media in the past hour (overall, Instagram, or WhatsApp, respectively), either actively or passively. All models included well-being as outcome variable. Since multilevel analyses allow to include all available data for each individual, no missing data were imputed and no data points were excluded.

We used a model building approach that involved three steps. In the first step, we estimated an intercept-only model to assess the relative amount of between- and within-person variance in affective well-being. We estimated a three-level model in which repeated momentary assessments (level 1) were nested within adolescents (level 2), who, in turn, were nested within classrooms (level 3). However, because the between-classroom variance in affective well-being was small (i.e., 0.4% of the variance was explained by differences between classes), we proceeded with estimating two-level (instead of three-level) models, with repeated momentary assessments (level 1) nested within adolescents (level 2).

In the second step, we assessed the within-person associations of well-being with (a) overall active and passive social media use (i.e., the total of the three platforms), (b) active and passive use of Instagram, and (c) active and passive use of WhatsApp, by adding fixed effects to the model (Models 1A-6A). To facilitate the interpretation of the associations and control for the effects of time, a covariate was added that controlled for the n th assessment of the study week (instead of the n th assessment of the day, as preregistered). This so-called detrending is helpful to interpret within-person associations as correlated fluctuations beyond other changes in social media use and well-being 38 . In order to obtain within-person estimates, we person-mean centered all predictors 38 . Significance of the fixed effects was determined using the Wald test.

In the third and final step, we assessed heterogeneity in the within-person associations by adding random slopes to the models (Models 1B-6B). Significance of the random slopes was determined by comparing the fit of the fixed effects model with the fit of the random effects model, by performing the Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square test 39 and by comparing the Bayesian information criterion (BIC 40 ) and Akaike information criterion (AIC 41 ) of the models. When the random effects model had a significantly better fit than the fixed effects model (i.e., pointing at significant heterogeneity), variance components were inspected to investigate whether heterogeneity existed in the association of either active or passive use. Next, when evidence was found for significant heterogeneity, we computed person-specific effect sizes, based on the random effect models, to investigate what percentages of adolescents experienced better well-being, worse well-being, and no changes in well-being. In line with Keijsers and colleagues 42 we only included participants who had completed at least 10 assessments. In addition, for the dose–response associations, we constructed graphical representations of the person-specific slopes, based on the person-specific effect sizes, using the xyplot function from the lattice package in R 43 .

Three improvements were made to our original preregistered plan. First, rather than estimating the models with multilevel modelling in R 43 , we ran the preregistered models in Mplus 44 . Mplus provides standardized estimates for the fixed effects models, which offers insight into the effect sizes. This allowed us to compare the relative strength of the associations of passive versus active use with well-being. Second, instead of using the maximum likelihood estimator, we used the maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors (MLR), which are robust to non-normality. Sensitivity tests, uploaded on OSF ( https://osf.io/nhks2 ), indicated that the results were almost identical across the two software packages and estimation approaches. Third, to improve the interpretation of the results and make the scales of the duration measures of social media use and well-being more comparable, we transformed the social media duration scores (0 to 60 min) into scales running from 0 to 6, so that an increase of 1 unit reflects 10 min of social media use. The model estimates were unaffected by this transformation.

Reporting summary

Further information on the research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analysed during the current study is available in Figshare 45 . The preregistration of the design, sampling and analysis plan, and the analysis scripts used to analyse the data for this paper are available online on the Open Science Framework website ( https://osf.io/nhks2 ).

Best, P., Manktelow, R. & Taylor, B. Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: A systematic narrative review. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 41 , 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.001 (2014).

Article Google Scholar

James, C. et al. Digital life and youth well-being, social connectedness, empathy, and narcissism. Pediatrics 140 , S71–S75. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1758F (2017).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

McCrae, N., Gettings, S. & Purssell, E. Social media and depressive symptoms in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2 , 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-017-0053-4 (2017).

Sarmiento, I. G. et al. How does social media use relate to adolescents’ internalizing symptoms? Conclusions from a systematic narrative review. Adolesc Res Rev , 1–24, doi:10.1007/s40894-018-0095-2 (2018).

Orben, A. Teenagers, screens and social media: A narrative review of reviews and key studies. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01825-4 (2020).

Orben, A., Dienlin, T. & Przybylski, A. K. Social media’s enduring effect on adolescent life satisfaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116 , 10226–10228. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1902058116 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Whitlock, J. & Masur, P. K. Disentangling the association of screen time with developmental outcomes and well-being: Problems, challenges, and opportunities. JAMA https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3191 (2019).

Hamaker, E. L. In Handbook of Research Methods for Studying Daily Life (eds Mehl, M. R. & Conner, T. S.) 43–61 (Guilford Press, New York, 2012).

Schmiedek, F. & Dirk, J. In The Encyclopedia of Adulthood and Aging (ed. Krauss Whitbourne, S.) 1–6 (Wiley, 2015).

Keijsers, L. & van Roekel, E. In Reframing Adolescent Research (eds Hendry, L. B. & Kloep, M.) (Routledge, 2018).

Coyne, S. M., Rogers, A. A., Zurcher, J. D., Stockdale, L. & Booth, M. Does time spent using social media impact mental health? An eight year longitudinal study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 104 , 106160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106160 (2020).

Boers, E., Afzali, M. H., Newton, N. & Conrod, P. Association of screen time and depression in adolescence. JAMA 173 , 853–859. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1759 (2019).

Jensen, M., George, M. J., Russell, M. R. & Odgers, C. L. Young adolescents’ digital technology use and mental health symptoms: Little evidence of longitudinal or daily linkages. Clin. Psychol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702619859336 (2019).

Valkenburg, P. M. The limited informativeness of meta-analyses of media effects. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10 , 680–682. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615592237 (2015).

Pearce, L. J. & Field, A. P. The impact of “scary” TV and film on children’s internalizing emotions: A meta-analysis. Hum. Commun.. Res. 42 , 98–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12069 (2016).

Howard, M. C. & Hoffman, M. E. Variable-centered, person-centered, and person-specific approaches. Organ. Res. Methods 21 , 846–876. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428117744021 (2017).

Valkenburg, P. M. & Peter, J. The differential susceptibility to media effects model. J. Commun. 63 , 221–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12024 (2013).

Eid, M. & Diener, E. Global judgments of subjective well-being: Situational variability and long-term stability. Soc. Indic. Res. 65 , 245–277. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SOCI.0000003801.89195.bc (2004).

Kross, E. et al. Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS ONE 8 , e69841. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069841 (2013).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Reissmann, A., Hauser, J., Stollberg, E., Kaunzinger, I. & Lange, K. W. The role of loneliness in emerging adults’ everyday use of facebook—An experience sampling approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 88 , 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.06.011 (2018).

Rutledge, R. B., Skandali, N., Dayan, P. & Dolan, R. J. A computational and neural model of momentary subjective well-being. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111 , 12252–12257. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1407535111 (2014).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Tov, W. In Handbook of Well-being (eds Diener, E.D. et al. ) (DEF Publishers, 2018).

Harter, S. The Construction of the Self: Developmental and Sociocultural Foundations (Guilford Press, New York, 2012).

Steinberg, L. Adolescence . Vol. 9 (McGraw-Hill, 2011).

Rideout, V. & Fox, S. Digital Health Practices, Social Media Use, and Mental Well-being Among Teens and Young Adults in the US (HopeLab, San Francisco, 2018).

Google Scholar

Waterloo, S. F., Baumgartner, S. E., Peter, J. & Valkenburg, P. M. Norms of online expressions of emotion: Comparing Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and WhatsApp. New Media Soc. 20 , 1813–1831. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817707349 (2017).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rideout, V. & Robb, M. B. Social Media, Social Life: Teens Reveal their Experiences (Common Sense Media, San Fransico, 2018).

van Driel, I. I., Pouwels, J. L., Beyens, I., Keijsers, L. & Valkenburg, P. M. 'Posting, Scrolling, Chatting & Snapping': Youth (14–15) and Social Media in 2019 (Center for Research on Children, Adolescents, and the Media (CcaM), Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2019).

Verduyn, P. et al. Passive Facebook usage undermines affective well-being: Experimental and longitudinal evidence. J. Exp. Psychol. 144 , 480–488. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000057 (2015).

Valkenburg, P. M. & Peter, J. Five challenges for the future of media-effects research. Int. J. Commun. 7 , 197–215 (2013).

Verduyn, P., Ybarra, O., Résibois, M., Jonides, J. & Kross, E. Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being? A critical review. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 11 , 274–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12033 (2017).

Radovic, A., Gmelin, T., Stein, B. D. & Miller, E. Depressed adolescents’ positive and negative use of social media. J. Adolesc. 55 , 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.002 (2017).

Valkenburg, P. M., Peter, J. & Schouten, A. P. Friend networking sites and their relationship to adolescents’ well-being and social self-esteem. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 9 , 584–590. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9.584 (2006).

van Roekel, E., Keijsers, L. & Chung, J. M. A review of current ambulatory assessment studies in adolescent samples and practical recommendations. J. Res. Adolesc. 29 , 560–577. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12471 (2019).

van Roekel, E., Scholte, R. H. J., Engels, R. C. M. E., Goossens, L. & Verhagen, M. Loneliness in the daily lives of adolescents: An experience sampling study examining the effects of social contexts. J. Early Adolesc. 35 , 905–930. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431614547049 (2015).

Neumann, A., van Lier, P. A. C., Frijns, T., Meeus, W. & Koot, H. M. Emotional dynamics in the development of early adolescent psychopathology: A one-year longitudinal Study. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 39 , 657–669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-011-9509-3 (2011).

Hox, J., Moerbeek, M. & van de Schoot, R. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications 3rd edn. (Routledge, London, 2018).

Wang, L. P. & Maxwell, S. E. On disaggregating between-person and within-person effects with longitudinal data using multilevel models. Psychol. Methods 20 , 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000030 (2015).

Satorra, A. & Bentler, P. M. Ensuring positiveness of the scaled difference chi-square test statistic. Psychometrika 75 , 243–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-009-9135-y (2010).

Article MathSciNet PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Schwarz, G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann. Stat. 6 , 461–464. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1176344136 (1978).

Article MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar

Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 19 , 716–723. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705 (1974).

Article ADS MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar

Keijsers, L. et al. What drives developmental change in adolescent disclosure and maternal knowledge? Heterogeneity in within-family processes. Dev. Psychol. 52 , 2057–2070. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000220 (2016).

R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, 2017).

Muthén, L. K. & Muthén, B. O. Mplus User’s Guide 8th edn. (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, 2017).

Beyens, I., Pouwels, J. L., van Driel, I. I., Keijsers, L. & Valkenburg, P. M. Dataset belonging to Beyens et al. (2020). The effect of social media on well-being differs from adolescent to adolescent. https://doi.org/10.21942/uva.12497990 (2020).

Download references

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the NWO Spinoza Prize and the Gravitation grant (NWO Grant 024.001.003; Consortium on Individual Development) awarded to P.M.V. by the Dutch Research Council (NWO). Additional funding was received from the VIDI grant (NWO VIDI Grant 452.17.011) awarded to L.K. by the Dutch Research Council (NWO). The authors would like to thank Savannah Boele (Tilburg University) for providing her pilot ESM results.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Amsterdam School of Communication Research, University of Amsterdam, 1001 NG, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Ine Beyens, J. Loes Pouwels, Irene I. van Driel & Patti M. Valkenburg

Department of Developmental Psychology, Tilburg University, 5000 LE, Tilburg, The Netherlands

Loes Keijsers

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

I.B., J.L.P., I.I.v.D., L.K., and P.M.V. designed the study; I.B., J.L.P., and I.I.v.D. collected the data; I.B., J.L.P., and L.K. analyzed the data; and I.B., J.L.P., I.I.v.D., L.K., and P.M.V. contributed to writing and reviewing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ine Beyens .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Beyens, I., Pouwels, J.L., van Driel, I.I. et al. The effect of social media on well-being differs from adolescent to adolescent. Sci Rep 10 , 10763 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67727-7

Download citation

Received : 24 January 2020

Accepted : 11 June 2020

Published : 01 July 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67727-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

- Sumer S. Vaid

- Lara Kroencke

- Gabriella M. Harari

Scientific Reports (2024)

Social Media and Youth Mental Health: Assessing the Impact Through Current and Novel Digital Phenotyping Methods

- Elana Perlmutter

- Bridget Dwyer

- John Torous

Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry (2024)

Problematic social media use and psychological symptoms in adolescents

- Ramin Mojtabai

Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology (2024)

Mental health profiles of Finnish adolescents before and after the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic

- Jasmine Gustafsson

- Nelli Lyyra

- Leena Paakkari

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health (2023)

The importance of high quality real-life social interactions during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Maximilian Monninger

- Pascal-M. Aggensteiner

- Nathalie E. Holz

Scientific Reports (2023)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Open access

- Published: 06 July 2023

Pros & cons: impacts of social media on mental health

- Ágnes Zsila 1 , 2 &

- Marc Eric S. Reyes ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5280-1315 3

BMC Psychology volume 11 , Article number: 201 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

371k Accesses

13 Citations

89 Altmetric

Metrics details

The use of social media significantly impacts mental health. It can enhance connection, increase self-esteem, and improve a sense of belonging. But it can also lead to tremendous stress, pressure to compare oneself to others, and increased sadness and isolation. Mindful use is essential to social media consumption.

Social media has become integral to our daily routines: we interact with family members and friends, accept invitations to public events, and join online communities to meet people who share similar preferences using these platforms. Social media has opened a new avenue for social experiences since the early 2000s, extending the possibilities for communication. According to recent research [ 1 ], people spend 2.3 h daily on social media. YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, and Snapchat have become increasingly popular among youth in 2022, and one-third think they spend too much time on these platforms [ 2 ]. The considerable time people spend on social media worldwide has directed researchers’ attention toward the potential benefits and risks. Research shows excessive use is mainly associated with lower psychological well-being [ 3 ]. However, findings also suggest that the quality rather than the quantity of social media use can determine whether the experience will enhance or deteriorate the user’s mental health [ 4 ]. In this collection, we will explore the impact of social media use on mental health by providing comprehensive research perspectives on positive and negative effects.

Social media can provide opportunities to enhance the mental health of users by facilitating social connections and peer support [ 5 ]. Indeed, online communities can provide a space for discussions regarding health conditions, adverse life events, or everyday challenges, which may decrease the sense of stigmatization and increase belongingness and perceived emotional support. Mutual friendships, rewarding social interactions, and humor on social media also reduced stress during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 4 ].

On the other hand, several studies have pointed out the potentially detrimental effects of social media use on mental health. Concerns have been raised that social media may lead to body image dissatisfaction [ 6 ], increase the risk of addiction and cyberbullying involvement [ 5 ], contribute to phubbing behaviors [ 7 ], and negatively affects mood [ 8 ]. Excessive use has increased loneliness, fear of missing out, and decreased subjective well-being and life satisfaction [ 8 ]. Users at risk of social media addiction often report depressive symptoms and lower self-esteem [ 9 ].

Overall, findings regarding the impact of social media on mental health pointed out some essential resources for psychological well-being through rewarding online social interactions. However, there is a need to raise awareness about the possible risks associated with excessive use, which can negatively affect mental health and everyday functioning [ 9 ]. There is neither a negative nor positive consensus regarding the effects of social media on people. However, by teaching people social media literacy, we can maximize their chances of having balanced, safe, and meaningful experiences on these platforms [ 10 ].

We encourage researchers to submit their research articles and contribute to a more differentiated overview of the impact of social media on mental health. BMC Psychology welcomes submissions to its new collection, which promises to present the latest findings in the emerging field of social media research. We seek research papers using qualitative and quantitative methods, focusing on social media users’ positive and negative aspects. We believe this collection will provide a more comprehensive picture of social media’s positive and negative effects on users’ mental health.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Statista. (2022). Time spent on social media [Chart]. Accessed June 14, 2023, from https://www.statista.com/chart/18983/time-spent-on-social-media/ .

Pew Research Center. (2023). Teens and social media: Key findings from Pew Research Center surveys. Retrieved June 14, 2023, from https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/04/24/teens-and-social-media-key-findings-from-pew-research-center-surveys/ .

Boer, M., Van Den Eijnden, R. J., Boniel-Nissim, M., Wong, S. L., Inchley, J. C.,Badura, P.,… Stevens, G. W. (2020). Adolescents’ intense and problematic social media use and their well-being in 29 countries. Journal of Adolescent Health , 66(6), S89-S99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.02.011.

Marciano L, Ostroumova M, Schulz PJ, Camerini AL. Digital media use and adolescents’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2022;9:2208. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.641831 .

Article Google Scholar

Naslund JA, Bondre A, Torous J, Aschbrenner KA. Social media and mental health: benefits, risks, and opportunities for research and practice. J Technol Behav Sci. 2020;5:245–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-020-00094-8 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Harriger JA, Thompson JK, Tiggemann M. TikTok, TikTok, the time is now: future directions in social media and body image. Body Image. 2023;44:222–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.12.005 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Chi LC, Tang TC, Tang E. The phubbing phenomenon: a cross-sectional study on the relationships among social media addiction, fear of missing out, personality traits, and phubbing behavior. Curr Psychol. 2022;41(2):1112–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-0135-4 .

Valkenburg PM. Social media use and well-being: what we know and what we need to know. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022;45:101294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.101294 .

Bányai F, Zsila Á, Király O, Maraz A, Elekes Z, Griffiths MD, Urbán R, Farkas J, Rigó P Jr, Demetrovics Z. Problematic social media use: results from a large-scale nationally representative adolescent sample. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0169839. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169839 .

American Psychological Association. (2023). APA panel issues recommendations for adolescent social media use. Retrieved from https://apa-panel-issues-recommendations-for-adolescent-social-media-use-774560.html .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Ágnes Zsila was supported by the ÚNKP-22-4 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Psychology, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Budapest, Hungary

Ágnes Zsila

Institute of Psychology, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary

Department of Psychology, College of Science, University of Santo Tomas, Manila, 1008, Philippines

Marc Eric S. Reyes

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AZ conceived and drafted the Editorial. MESR wrote the abstract and revised the Editorial. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Marc Eric S. Reyes .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors have no competing interests to declare relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

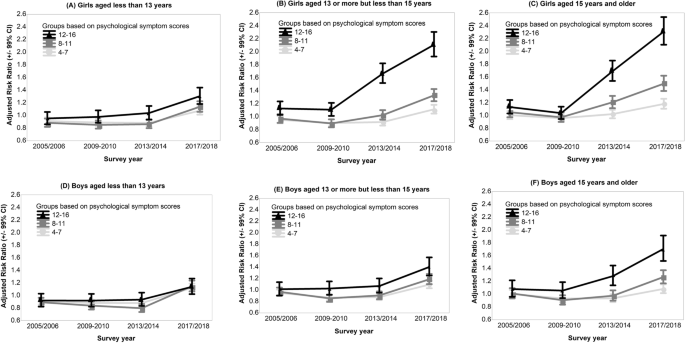

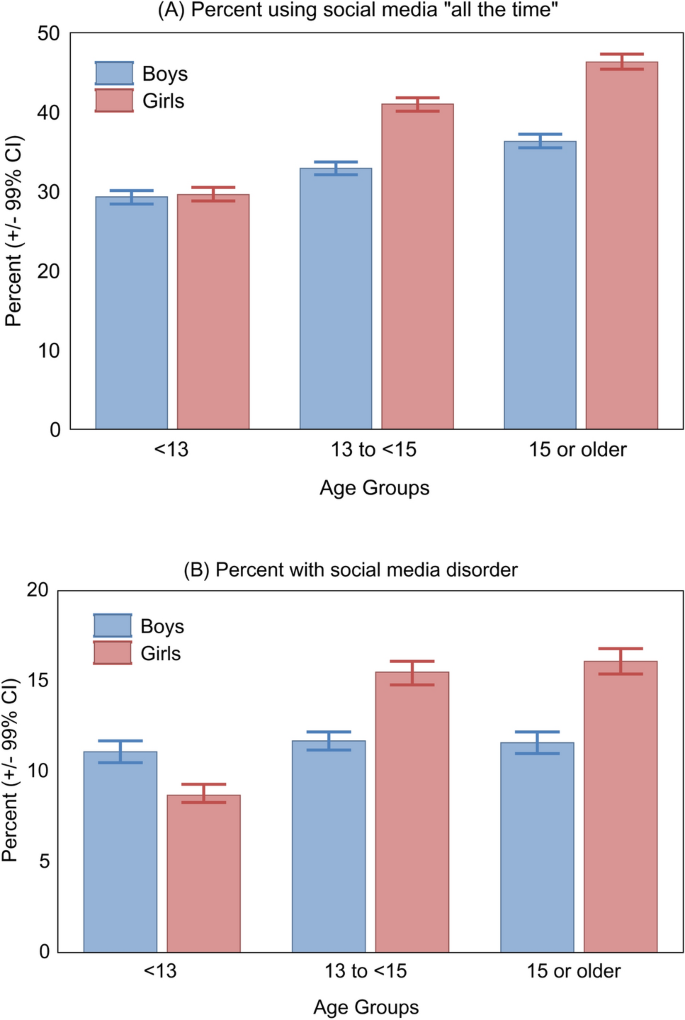

Rights and permissions