An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Korean Med Sci

- v.37(16); 2022 Apr 25

A Practical Guide to Writing Quantitative and Qualitative Research Questions and Hypotheses in Scholarly Articles

Edward barroga.

1 Department of General Education, Graduate School of Nursing Science, St. Luke’s International University, Tokyo, Japan.

Glafera Janet Matanguihan

2 Department of Biological Sciences, Messiah University, Mechanicsburg, PA, USA.

The development of research questions and the subsequent hypotheses are prerequisites to defining the main research purpose and specific objectives of a study. Consequently, these objectives determine the study design and research outcome. The development of research questions is a process based on knowledge of current trends, cutting-edge studies, and technological advances in the research field. Excellent research questions are focused and require a comprehensive literature search and in-depth understanding of the problem being investigated. Initially, research questions may be written as descriptive questions which could be developed into inferential questions. These questions must be specific and concise to provide a clear foundation for developing hypotheses. Hypotheses are more formal predictions about the research outcomes. These specify the possible results that may or may not be expected regarding the relationship between groups. Thus, research questions and hypotheses clarify the main purpose and specific objectives of the study, which in turn dictate the design of the study, its direction, and outcome. Studies developed from good research questions and hypotheses will have trustworthy outcomes with wide-ranging social and health implications.

INTRODUCTION

Scientific research is usually initiated by posing evidenced-based research questions which are then explicitly restated as hypotheses. 1 , 2 The hypotheses provide directions to guide the study, solutions, explanations, and expected results. 3 , 4 Both research questions and hypotheses are essentially formulated based on conventional theories and real-world processes, which allow the inception of novel studies and the ethical testing of ideas. 5 , 6

It is crucial to have knowledge of both quantitative and qualitative research 2 as both types of research involve writing research questions and hypotheses. 7 However, these crucial elements of research are sometimes overlooked; if not overlooked, then framed without the forethought and meticulous attention it needs. Planning and careful consideration are needed when developing quantitative or qualitative research, particularly when conceptualizing research questions and hypotheses. 4

There is a continuing need to support researchers in the creation of innovative research questions and hypotheses, as well as for journal articles that carefully review these elements. 1 When research questions and hypotheses are not carefully thought of, unethical studies and poor outcomes usually ensue. Carefully formulated research questions and hypotheses define well-founded objectives, which in turn determine the appropriate design, course, and outcome of the study. This article then aims to discuss in detail the various aspects of crafting research questions and hypotheses, with the goal of guiding researchers as they develop their own. Examples from the authors and peer-reviewed scientific articles in the healthcare field are provided to illustrate key points.

DEFINITIONS AND RELATIONSHIP OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

A research question is what a study aims to answer after data analysis and interpretation. The answer is written in length in the discussion section of the paper. Thus, the research question gives a preview of the different parts and variables of the study meant to address the problem posed in the research question. 1 An excellent research question clarifies the research writing while facilitating understanding of the research topic, objective, scope, and limitations of the study. 5

On the other hand, a research hypothesis is an educated statement of an expected outcome. This statement is based on background research and current knowledge. 8 , 9 The research hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a new phenomenon 10 or a formal statement on the expected relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable. 3 , 11 It provides a tentative answer to the research question to be tested or explored. 4

Hypotheses employ reasoning to predict a theory-based outcome. 10 These can also be developed from theories by focusing on components of theories that have not yet been observed. 10 The validity of hypotheses is often based on the testability of the prediction made in a reproducible experiment. 8

Conversely, hypotheses can also be rephrased as research questions. Several hypotheses based on existing theories and knowledge may be needed to answer a research question. Developing ethical research questions and hypotheses creates a research design that has logical relationships among variables. These relationships serve as a solid foundation for the conduct of the study. 4 , 11 Haphazardly constructed research questions can result in poorly formulated hypotheses and improper study designs, leading to unreliable results. Thus, the formulations of relevant research questions and verifiable hypotheses are crucial when beginning research. 12

CHARACTERISTICS OF GOOD RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Excellent research questions are specific and focused. These integrate collective data and observations to confirm or refute the subsequent hypotheses. Well-constructed hypotheses are based on previous reports and verify the research context. These are realistic, in-depth, sufficiently complex, and reproducible. More importantly, these hypotheses can be addressed and tested. 13

There are several characteristics of well-developed hypotheses. Good hypotheses are 1) empirically testable 7 , 10 , 11 , 13 ; 2) backed by preliminary evidence 9 ; 3) testable by ethical research 7 , 9 ; 4) based on original ideas 9 ; 5) have evidenced-based logical reasoning 10 ; and 6) can be predicted. 11 Good hypotheses can infer ethical and positive implications, indicating the presence of a relationship or effect relevant to the research theme. 7 , 11 These are initially developed from a general theory and branch into specific hypotheses by deductive reasoning. In the absence of a theory to base the hypotheses, inductive reasoning based on specific observations or findings form more general hypotheses. 10

TYPES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions and hypotheses are developed according to the type of research, which can be broadly classified into quantitative and qualitative research. We provide a summary of the types of research questions and hypotheses under quantitative and qualitative research categories in Table 1 .

Research questions in quantitative research

In quantitative research, research questions inquire about the relationships among variables being investigated and are usually framed at the start of the study. These are precise and typically linked to the subject population, dependent and independent variables, and research design. 1 Research questions may also attempt to describe the behavior of a population in relation to one or more variables, or describe the characteristics of variables to be measured ( descriptive research questions ). 1 , 5 , 14 These questions may also aim to discover differences between groups within the context of an outcome variable ( comparative research questions ), 1 , 5 , 14 or elucidate trends and interactions among variables ( relationship research questions ). 1 , 5 We provide examples of descriptive, comparative, and relationship research questions in quantitative research in Table 2 .

Hypotheses in quantitative research

In quantitative research, hypotheses predict the expected relationships among variables. 15 Relationships among variables that can be predicted include 1) between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable ( simple hypothesis ) or 2) between two or more independent and dependent variables ( complex hypothesis ). 4 , 11 Hypotheses may also specify the expected direction to be followed and imply an intellectual commitment to a particular outcome ( directional hypothesis ) 4 . On the other hand, hypotheses may not predict the exact direction and are used in the absence of a theory, or when findings contradict previous studies ( non-directional hypothesis ). 4 In addition, hypotheses can 1) define interdependency between variables ( associative hypothesis ), 4 2) propose an effect on the dependent variable from manipulation of the independent variable ( causal hypothesis ), 4 3) state a negative relationship between two variables ( null hypothesis ), 4 , 11 , 15 4) replace the working hypothesis if rejected ( alternative hypothesis ), 15 explain the relationship of phenomena to possibly generate a theory ( working hypothesis ), 11 5) involve quantifiable variables that can be tested statistically ( statistical hypothesis ), 11 6) or express a relationship whose interlinks can be verified logically ( logical hypothesis ). 11 We provide examples of simple, complex, directional, non-directional, associative, causal, null, alternative, working, statistical, and logical hypotheses in quantitative research, as well as the definition of quantitative hypothesis-testing research in Table 3 .

Research questions in qualitative research

Unlike research questions in quantitative research, research questions in qualitative research are usually continuously reviewed and reformulated. The central question and associated subquestions are stated more than the hypotheses. 15 The central question broadly explores a complex set of factors surrounding the central phenomenon, aiming to present the varied perspectives of participants. 15

There are varied goals for which qualitative research questions are developed. These questions can function in several ways, such as to 1) identify and describe existing conditions ( contextual research question s); 2) describe a phenomenon ( descriptive research questions ); 3) assess the effectiveness of existing methods, protocols, theories, or procedures ( evaluation research questions ); 4) examine a phenomenon or analyze the reasons or relationships between subjects or phenomena ( explanatory research questions ); or 5) focus on unknown aspects of a particular topic ( exploratory research questions ). 5 In addition, some qualitative research questions provide new ideas for the development of theories and actions ( generative research questions ) or advance specific ideologies of a position ( ideological research questions ). 1 Other qualitative research questions may build on a body of existing literature and become working guidelines ( ethnographic research questions ). Research questions may also be broadly stated without specific reference to the existing literature or a typology of questions ( phenomenological research questions ), may be directed towards generating a theory of some process ( grounded theory questions ), or may address a description of the case and the emerging themes ( qualitative case study questions ). 15 We provide examples of contextual, descriptive, evaluation, explanatory, exploratory, generative, ideological, ethnographic, phenomenological, grounded theory, and qualitative case study research questions in qualitative research in Table 4 , and the definition of qualitative hypothesis-generating research in Table 5 .

Qualitative studies usually pose at least one central research question and several subquestions starting with How or What . These research questions use exploratory verbs such as explore or describe . These also focus on one central phenomenon of interest, and may mention the participants and research site. 15

Hypotheses in qualitative research

Hypotheses in qualitative research are stated in the form of a clear statement concerning the problem to be investigated. Unlike in quantitative research where hypotheses are usually developed to be tested, qualitative research can lead to both hypothesis-testing and hypothesis-generating outcomes. 2 When studies require both quantitative and qualitative research questions, this suggests an integrative process between both research methods wherein a single mixed-methods research question can be developed. 1

FRAMEWORKS FOR DEVELOPING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions followed by hypotheses should be developed before the start of the study. 1 , 12 , 14 It is crucial to develop feasible research questions on a topic that is interesting to both the researcher and the scientific community. This can be achieved by a meticulous review of previous and current studies to establish a novel topic. Specific areas are subsequently focused on to generate ethical research questions. The relevance of the research questions is evaluated in terms of clarity of the resulting data, specificity of the methodology, objectivity of the outcome, depth of the research, and impact of the study. 1 , 5 These aspects constitute the FINER criteria (i.e., Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, and Relevant). 1 Clarity and effectiveness are achieved if research questions meet the FINER criteria. In addition to the FINER criteria, Ratan et al. described focus, complexity, novelty, feasibility, and measurability for evaluating the effectiveness of research questions. 14

The PICOT and PEO frameworks are also used when developing research questions. 1 The following elements are addressed in these frameworks, PICOT: P-population/patients/problem, I-intervention or indicator being studied, C-comparison group, O-outcome of interest, and T-timeframe of the study; PEO: P-population being studied, E-exposure to preexisting conditions, and O-outcome of interest. 1 Research questions are also considered good if these meet the “FINERMAPS” framework: Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, Relevant, Manageable, Appropriate, Potential value/publishable, and Systematic. 14

As we indicated earlier, research questions and hypotheses that are not carefully formulated result in unethical studies or poor outcomes. To illustrate this, we provide some examples of ambiguous research question and hypotheses that result in unclear and weak research objectives in quantitative research ( Table 6 ) 16 and qualitative research ( Table 7 ) 17 , and how to transform these ambiguous research question(s) and hypothesis(es) into clear and good statements.

a These statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

b These statements are direct quotes from Higashihara and Horiuchi. 16

a This statement is a direct quote from Shimoda et al. 17

The other statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

CONSTRUCTING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

To construct effective research questions and hypotheses, it is very important to 1) clarify the background and 2) identify the research problem at the outset of the research, within a specific timeframe. 9 Then, 3) review or conduct preliminary research to collect all available knowledge about the possible research questions by studying theories and previous studies. 18 Afterwards, 4) construct research questions to investigate the research problem. Identify variables to be accessed from the research questions 4 and make operational definitions of constructs from the research problem and questions. Thereafter, 5) construct specific deductive or inductive predictions in the form of hypotheses. 4 Finally, 6) state the study aims . This general flow for constructing effective research questions and hypotheses prior to conducting research is shown in Fig. 1 .

Research questions are used more frequently in qualitative research than objectives or hypotheses. 3 These questions seek to discover, understand, explore or describe experiences by asking “What” or “How.” The questions are open-ended to elicit a description rather than to relate variables or compare groups. The questions are continually reviewed, reformulated, and changed during the qualitative study. 3 Research questions are also used more frequently in survey projects than hypotheses in experiments in quantitative research to compare variables and their relationships.

Hypotheses are constructed based on the variables identified and as an if-then statement, following the template, ‘If a specific action is taken, then a certain outcome is expected.’ At this stage, some ideas regarding expectations from the research to be conducted must be drawn. 18 Then, the variables to be manipulated (independent) and influenced (dependent) are defined. 4 Thereafter, the hypothesis is stated and refined, and reproducible data tailored to the hypothesis are identified, collected, and analyzed. 4 The hypotheses must be testable and specific, 18 and should describe the variables and their relationships, the specific group being studied, and the predicted research outcome. 18 Hypotheses construction involves a testable proposition to be deduced from theory, and independent and dependent variables to be separated and measured separately. 3 Therefore, good hypotheses must be based on good research questions constructed at the start of a study or trial. 12

In summary, research questions are constructed after establishing the background of the study. Hypotheses are then developed based on the research questions. Thus, it is crucial to have excellent research questions to generate superior hypotheses. In turn, these would determine the research objectives and the design of the study, and ultimately, the outcome of the research. 12 Algorithms for building research questions and hypotheses are shown in Fig. 2 for quantitative research and in Fig. 3 for qualitative research.

EXAMPLES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS FROM PUBLISHED ARTICLES

- EXAMPLE 1. Descriptive research question (quantitative research)

- - Presents research variables to be assessed (distinct phenotypes and subphenotypes)

- “BACKGROUND: Since COVID-19 was identified, its clinical and biological heterogeneity has been recognized. Identifying COVID-19 phenotypes might help guide basic, clinical, and translational research efforts.

- RESEARCH QUESTION: Does the clinical spectrum of patients with COVID-19 contain distinct phenotypes and subphenotypes? ” 19

- EXAMPLE 2. Relationship research question (quantitative research)

- - Shows interactions between dependent variable (static postural control) and independent variable (peripheral visual field loss)

- “Background: Integration of visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive sensations contributes to postural control. People with peripheral visual field loss have serious postural instability. However, the directional specificity of postural stability and sensory reweighting caused by gradual peripheral visual field loss remain unclear.

- Research question: What are the effects of peripheral visual field loss on static postural control ?” 20

- EXAMPLE 3. Comparative research question (quantitative research)

- - Clarifies the difference among groups with an outcome variable (patients enrolled in COMPERA with moderate PH or severe PH in COPD) and another group without the outcome variable (patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH))

- “BACKGROUND: Pulmonary hypertension (PH) in COPD is a poorly investigated clinical condition.

- RESEARCH QUESTION: Which factors determine the outcome of PH in COPD?

- STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS: We analyzed the characteristics and outcome of patients enrolled in the Comparative, Prospective Registry of Newly Initiated Therapies for Pulmonary Hypertension (COMPERA) with moderate or severe PH in COPD as defined during the 6th PH World Symposium who received medical therapy for PH and compared them with patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) .” 21

- EXAMPLE 4. Exploratory research question (qualitative research)

- - Explores areas that have not been fully investigated (perspectives of families and children who receive care in clinic-based child obesity treatment) to have a deeper understanding of the research problem

- “Problem: Interventions for children with obesity lead to only modest improvements in BMI and long-term outcomes, and data are limited on the perspectives of families of children with obesity in clinic-based treatment. This scoping review seeks to answer the question: What is known about the perspectives of families and children who receive care in clinic-based child obesity treatment? This review aims to explore the scope of perspectives reported by families of children with obesity who have received individualized outpatient clinic-based obesity treatment.” 22

- EXAMPLE 5. Relationship research question (quantitative research)

- - Defines interactions between dependent variable (use of ankle strategies) and independent variable (changes in muscle tone)

- “Background: To maintain an upright standing posture against external disturbances, the human body mainly employs two types of postural control strategies: “ankle strategy” and “hip strategy.” While it has been reported that the magnitude of the disturbance alters the use of postural control strategies, it has not been elucidated how the level of muscle tone, one of the crucial parameters of bodily function, determines the use of each strategy. We have previously confirmed using forward dynamics simulations of human musculoskeletal models that an increased muscle tone promotes the use of ankle strategies. The objective of the present study was to experimentally evaluate a hypothesis: an increased muscle tone promotes the use of ankle strategies. Research question: Do changes in the muscle tone affect the use of ankle strategies ?” 23

EXAMPLES OF HYPOTHESES IN PUBLISHED ARTICLES

- EXAMPLE 1. Working hypothesis (quantitative research)

- - A hypothesis that is initially accepted for further research to produce a feasible theory

- “As fever may have benefit in shortening the duration of viral illness, it is plausible to hypothesize that the antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen may be hindering the benefits of a fever response when taken during the early stages of COVID-19 illness .” 24

- “In conclusion, it is plausible to hypothesize that the antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen may be hindering the benefits of a fever response . The difference in perceived safety of these agents in COVID-19 illness could be related to the more potent efficacy to reduce fever with ibuprofen compared to acetaminophen. Compelling data on the benefit of fever warrant further research and review to determine when to treat or withhold ibuprofen for early stage fever for COVID-19 and other related viral illnesses .” 24

- EXAMPLE 2. Exploratory hypothesis (qualitative research)

- - Explores particular areas deeper to clarify subjective experience and develop a formal hypothesis potentially testable in a future quantitative approach

- “We hypothesized that when thinking about a past experience of help-seeking, a self distancing prompt would cause increased help-seeking intentions and more favorable help-seeking outcome expectations .” 25

- “Conclusion

- Although a priori hypotheses were not supported, further research is warranted as results indicate the potential for using self-distancing approaches to increasing help-seeking among some people with depressive symptomatology.” 25

- EXAMPLE 3. Hypothesis-generating research to establish a framework for hypothesis testing (qualitative research)

- “We hypothesize that compassionate care is beneficial for patients (better outcomes), healthcare systems and payers (lower costs), and healthcare providers (lower burnout). ” 26

- Compassionomics is the branch of knowledge and scientific study of the effects of compassionate healthcare. Our main hypotheses are that compassionate healthcare is beneficial for (1) patients, by improving clinical outcomes, (2) healthcare systems and payers, by supporting financial sustainability, and (3) HCPs, by lowering burnout and promoting resilience and well-being. The purpose of this paper is to establish a scientific framework for testing the hypotheses above . If these hypotheses are confirmed through rigorous research, compassionomics will belong in the science of evidence-based medicine, with major implications for all healthcare domains.” 26

- EXAMPLE 4. Statistical hypothesis (quantitative research)

- - An assumption is made about the relationship among several population characteristics ( gender differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of adults with ADHD ). Validity is tested by statistical experiment or analysis ( chi-square test, Students t-test, and logistic regression analysis)

- “Our research investigated gender differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of adults with ADHD in a Japanese clinical sample. Due to unique Japanese cultural ideals and expectations of women's behavior that are in opposition to ADHD symptoms, we hypothesized that women with ADHD experience more difficulties and present more dysfunctions than men . We tested the following hypotheses: first, women with ADHD have more comorbidities than men with ADHD; second, women with ADHD experience more social hardships than men, such as having less full-time employment and being more likely to be divorced.” 27

- “Statistical Analysis

- ( text omitted ) Between-gender comparisons were made using the chi-squared test for categorical variables and Students t-test for continuous variables…( text omitted ). A logistic regression analysis was performed for employment status, marital status, and comorbidity to evaluate the independent effects of gender on these dependent variables.” 27

EXAMPLES OF HYPOTHESIS AS WRITTEN IN PUBLISHED ARTICLES IN RELATION TO OTHER PARTS

- EXAMPLE 1. Background, hypotheses, and aims are provided

- “Pregnant women need skilled care during pregnancy and childbirth, but that skilled care is often delayed in some countries …( text omitted ). The focused antenatal care (FANC) model of WHO recommends that nurses provide information or counseling to all pregnant women …( text omitted ). Job aids are visual support materials that provide the right kind of information using graphics and words in a simple and yet effective manner. When nurses are not highly trained or have many work details to attend to, these job aids can serve as a content reminder for the nurses and can be used for educating their patients (Jennings, Yebadokpo, Affo, & Agbogbe, 2010) ( text omitted ). Importantly, additional evidence is needed to confirm how job aids can further improve the quality of ANC counseling by health workers in maternal care …( text omitted )” 28

- “ This has led us to hypothesize that the quality of ANC counseling would be better if supported by job aids. Consequently, a better quality of ANC counseling is expected to produce higher levels of awareness concerning the danger signs of pregnancy and a more favorable impression of the caring behavior of nurses .” 28

- “This study aimed to examine the differences in the responses of pregnant women to a job aid-supported intervention during ANC visit in terms of 1) their understanding of the danger signs of pregnancy and 2) their impression of the caring behaviors of nurses to pregnant women in rural Tanzania.” 28

- EXAMPLE 2. Background, hypotheses, and aims are provided

- “We conducted a two-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate and compare changes in salivary cortisol and oxytocin levels of first-time pregnant women between experimental and control groups. The women in the experimental group touched and held an infant for 30 min (experimental intervention protocol), whereas those in the control group watched a DVD movie of an infant (control intervention protocol). The primary outcome was salivary cortisol level and the secondary outcome was salivary oxytocin level.” 29

- “ We hypothesize that at 30 min after touching and holding an infant, the salivary cortisol level will significantly decrease and the salivary oxytocin level will increase in the experimental group compared with the control group .” 29

- EXAMPLE 3. Background, aim, and hypothesis are provided

- “In countries where the maternal mortality ratio remains high, antenatal education to increase Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness (BPCR) is considered one of the top priorities [1]. BPCR includes birth plans during the antenatal period, such as the birthplace, birth attendant, transportation, health facility for complications, expenses, and birth materials, as well as family coordination to achieve such birth plans. In Tanzania, although increasing, only about half of all pregnant women attend an antenatal clinic more than four times [4]. Moreover, the information provided during antenatal care (ANC) is insufficient. In the resource-poor settings, antenatal group education is a potential approach because of the limited time for individual counseling at antenatal clinics.” 30

- “This study aimed to evaluate an antenatal group education program among pregnant women and their families with respect to birth-preparedness and maternal and infant outcomes in rural villages of Tanzania.” 30

- “ The study hypothesis was if Tanzanian pregnant women and their families received a family-oriented antenatal group education, they would (1) have a higher level of BPCR, (2) attend antenatal clinic four or more times, (3) give birth in a health facility, (4) have less complications of women at birth, and (5) have less complications and deaths of infants than those who did not receive the education .” 30

Research questions and hypotheses are crucial components to any type of research, whether quantitative or qualitative. These questions should be developed at the very beginning of the study. Excellent research questions lead to superior hypotheses, which, like a compass, set the direction of research, and can often determine the successful conduct of the study. Many research studies have floundered because the development of research questions and subsequent hypotheses was not given the thought and meticulous attention needed. The development of research questions and hypotheses is an iterative process based on extensive knowledge of the literature and insightful grasp of the knowledge gap. Focused, concise, and specific research questions provide a strong foundation for constructing hypotheses which serve as formal predictions about the research outcomes. Research questions and hypotheses are crucial elements of research that should not be overlooked. They should be carefully thought of and constructed when planning research. This avoids unethical studies and poor outcomes by defining well-founded objectives that determine the design, course, and outcome of the study.

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions:

- Conceptualization: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Methodology: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Writing - original draft: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Writing - review & editing: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

The Craft of Writing a Strong Hypothesis

Table of Contents

Writing a hypothesis is one of the essential elements of a scientific research paper. It needs to be to the point, clearly communicating what your research is trying to accomplish. A blurry, drawn-out, or complexly-structured hypothesis can confuse your readers. Or worse, the editor and peer reviewers.

A captivating hypothesis is not too intricate. This blog will take you through the process so that, by the end of it, you have a better idea of how to convey your research paper's intent in just one sentence.

What is a Hypothesis?

The first step in your scientific endeavor, a hypothesis, is a strong, concise statement that forms the basis of your research. It is not the same as a thesis statement , which is a brief summary of your research paper .

The sole purpose of a hypothesis is to predict your paper's findings, data, and conclusion. It comes from a place of curiosity and intuition . When you write a hypothesis, you're essentially making an educated guess based on scientific prejudices and evidence, which is further proven or disproven through the scientific method.

The reason for undertaking research is to observe a specific phenomenon. A hypothesis, therefore, lays out what the said phenomenon is. And it does so through two variables, an independent and dependent variable.

The independent variable is the cause behind the observation, while the dependent variable is the effect of the cause. A good example of this is “mixing red and blue forms purple.” In this hypothesis, mixing red and blue is the independent variable as you're combining the two colors at your own will. The formation of purple is the dependent variable as, in this case, it is conditional to the independent variable.

Different Types of Hypotheses

Types of hypotheses

Some would stand by the notion that there are only two types of hypotheses: a Null hypothesis and an Alternative hypothesis. While that may have some truth to it, it would be better to fully distinguish the most common forms as these terms come up so often, which might leave you out of context.

Apart from Null and Alternative, there are Complex, Simple, Directional, Non-Directional, Statistical, and Associative and casual hypotheses. They don't necessarily have to be exclusive, as one hypothesis can tick many boxes, but knowing the distinctions between them will make it easier for you to construct your own.

1. Null hypothesis

A null hypothesis proposes no relationship between two variables. Denoted by H 0 , it is a negative statement like “Attending physiotherapy sessions does not affect athletes' on-field performance.” Here, the author claims physiotherapy sessions have no effect on on-field performances. Even if there is, it's only a coincidence.

2. Alternative hypothesis

Considered to be the opposite of a null hypothesis, an alternative hypothesis is donated as H1 or Ha. It explicitly states that the dependent variable affects the independent variable. A good alternative hypothesis example is “Attending physiotherapy sessions improves athletes' on-field performance.” or “Water evaporates at 100 °C. ” The alternative hypothesis further branches into directional and non-directional.

- Directional hypothesis: A hypothesis that states the result would be either positive or negative is called directional hypothesis. It accompanies H1 with either the ‘<' or ‘>' sign.

- Non-directional hypothesis: A non-directional hypothesis only claims an effect on the dependent variable. It does not clarify whether the result would be positive or negative. The sign for a non-directional hypothesis is ‘≠.'

3. Simple hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement made to reflect the relation between exactly two variables. One independent and one dependent. Consider the example, “Smoking is a prominent cause of lung cancer." The dependent variable, lung cancer, is dependent on the independent variable, smoking.

4. Complex hypothesis

In contrast to a simple hypothesis, a complex hypothesis implies the relationship between multiple independent and dependent variables. For instance, “Individuals who eat more fruits tend to have higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.” The independent variable is eating more fruits, while the dependent variables are higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.

5. Associative and casual hypothesis

Associative and casual hypotheses don't exhibit how many variables there will be. They define the relationship between the variables. In an associative hypothesis, changing any one variable, dependent or independent, affects others. In a casual hypothesis, the independent variable directly affects the dependent.

6. Empirical hypothesis

Also referred to as the working hypothesis, an empirical hypothesis claims a theory's validation via experiments and observation. This way, the statement appears justifiable and different from a wild guess.

Say, the hypothesis is “Women who take iron tablets face a lesser risk of anemia than those who take vitamin B12.” This is an example of an empirical hypothesis where the researcher the statement after assessing a group of women who take iron tablets and charting the findings.

7. Statistical hypothesis

The point of a statistical hypothesis is to test an already existing hypothesis by studying a population sample. Hypothesis like “44% of the Indian population belong in the age group of 22-27.” leverage evidence to prove or disprove a particular statement.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

Writing a hypothesis is essential as it can make or break your research for you. That includes your chances of getting published in a journal. So when you're designing one, keep an eye out for these pointers:

- A research hypothesis has to be simple yet clear to look justifiable enough.

- It has to be testable — your research would be rendered pointless if too far-fetched into reality or limited by technology.

- It has to be precise about the results —what you are trying to do and achieve through it should come out in your hypothesis.

- A research hypothesis should be self-explanatory, leaving no doubt in the reader's mind.

- If you are developing a relational hypothesis, you need to include the variables and establish an appropriate relationship among them.

- A hypothesis must keep and reflect the scope for further investigations and experiments.

Separating a Hypothesis from a Prediction

Outside of academia, hypothesis and prediction are often used interchangeably. In research writing, this is not only confusing but also incorrect. And although a hypothesis and prediction are guesses at their core, there are many differences between them.

A hypothesis is an educated guess or even a testable prediction validated through research. It aims to analyze the gathered evidence and facts to define a relationship between variables and put forth a logical explanation behind the nature of events.

Predictions are assumptions or expected outcomes made without any backing evidence. They are more fictionally inclined regardless of where they originate from.

For this reason, a hypothesis holds much more weight than a prediction. It sticks to the scientific method rather than pure guesswork. "Planets revolve around the Sun." is an example of a hypothesis as it is previous knowledge and observed trends. Additionally, we can test it through the scientific method.

Whereas "COVID-19 will be eradicated by 2030." is a prediction. Even though it results from past trends, we can't prove or disprove it. So, the only way this gets validated is to wait and watch if COVID-19 cases end by 2030.

Finally, How to Write a Hypothesis

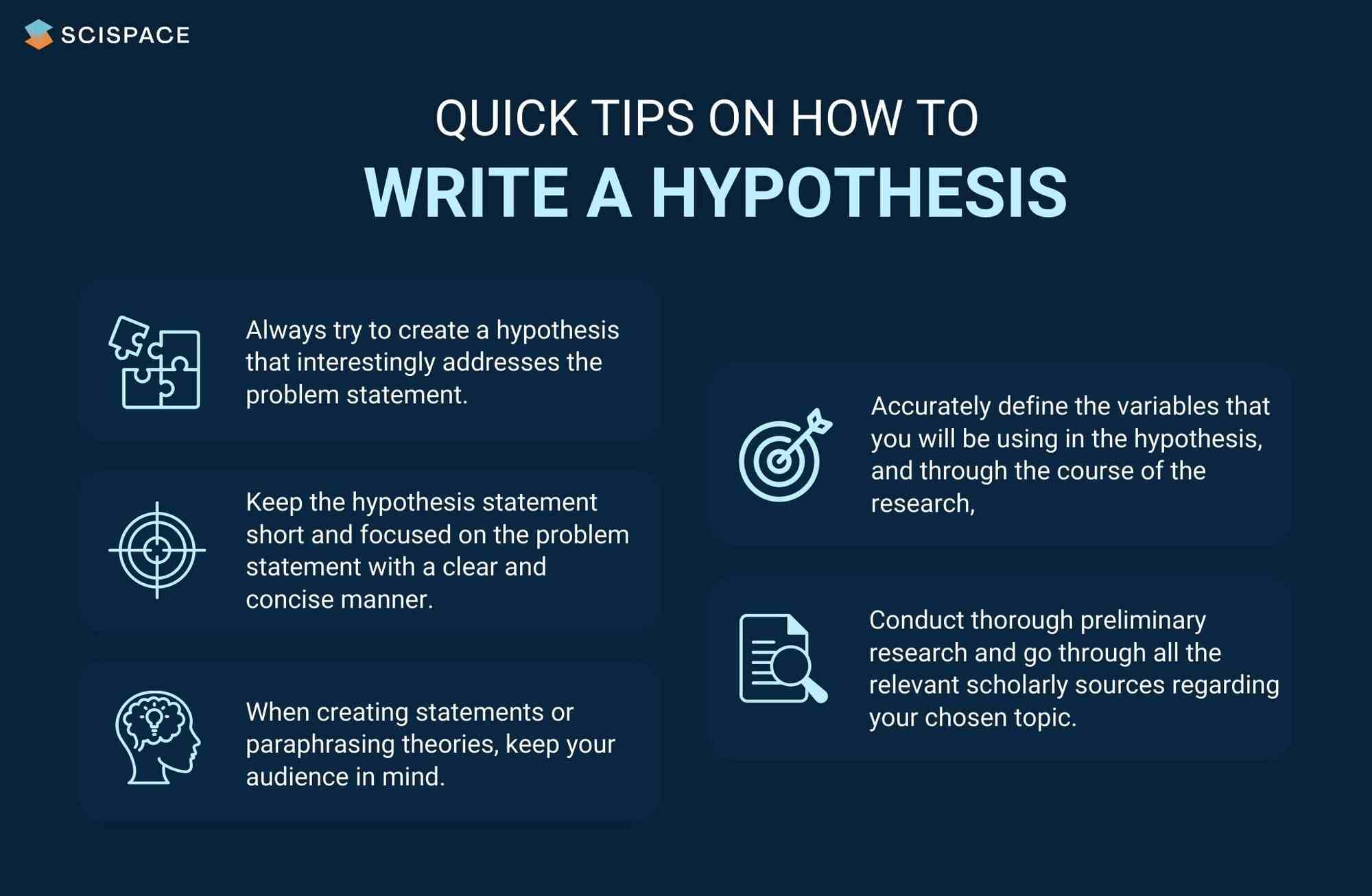

Quick tips on writing a hypothesis

1. Be clear about your research question

A hypothesis should instantly address the research question or the problem statement. To do so, you need to ask a question. Understand the constraints of your undertaken research topic and then formulate a simple and topic-centric problem. Only after that can you develop a hypothesis and further test for evidence.

2. Carry out a recce

Once you have your research's foundation laid out, it would be best to conduct preliminary research. Go through previous theories, academic papers, data, and experiments before you start curating your research hypothesis. It will give you an idea of your hypothesis's viability or originality.

Making use of references from relevant research papers helps draft a good research hypothesis. SciSpace Discover offers a repository of over 270 million research papers to browse through and gain a deeper understanding of related studies on a particular topic. Additionally, you can use SciSpace Copilot , your AI research assistant, for reading any lengthy research paper and getting a more summarized context of it. A hypothesis can be formed after evaluating many such summarized research papers. Copilot also offers explanations for theories and equations, explains paper in simplified version, allows you to highlight any text in the paper or clip math equations and tables and provides a deeper, clear understanding of what is being said. This can improve the hypothesis by helping you identify potential research gaps.

3. Create a 3-dimensional hypothesis

Variables are an essential part of any reasonable hypothesis. So, identify your independent and dependent variable(s) and form a correlation between them. The ideal way to do this is to write the hypothetical assumption in the ‘if-then' form. If you use this form, make sure that you state the predefined relationship between the variables.

In another way, you can choose to present your hypothesis as a comparison between two variables. Here, you must specify the difference you expect to observe in the results.

4. Write the first draft

Now that everything is in place, it's time to write your hypothesis. For starters, create the first draft. In this version, write what you expect to find from your research.

Clearly separate your independent and dependent variables and the link between them. Don't fixate on syntax at this stage. The goal is to ensure your hypothesis addresses the issue.

5. Proof your hypothesis

After preparing the first draft of your hypothesis, you need to inspect it thoroughly. It should tick all the boxes, like being concise, straightforward, relevant, and accurate. Your final hypothesis has to be well-structured as well.

Research projects are an exciting and crucial part of being a scholar. And once you have your research question, you need a great hypothesis to begin conducting research. Thus, knowing how to write a hypothesis is very important.

Now that you have a firmer grasp on what a good hypothesis constitutes, the different kinds there are, and what process to follow, you will find it much easier to write your hypothesis, which ultimately helps your research.

Now it's easier than ever to streamline your research workflow with SciSpace Discover . Its integrated, comprehensive end-to-end platform for research allows scholars to easily discover, write and publish their research and fosters collaboration.

It includes everything you need, including a repository of over 270 million research papers across disciplines, SEO-optimized summaries and public profiles to show your expertise and experience.

If you found these tips on writing a research hypothesis useful, head over to our blog on Statistical Hypothesis Testing to learn about the top researchers, papers, and institutions in this domain.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. what is the definition of hypothesis.

According to the Oxford dictionary, a hypothesis is defined as “An idea or explanation of something that is based on a few known facts, but that has not yet been proved to be true or correct”.

2. What is an example of hypothesis?

The hypothesis is a statement that proposes a relationship between two or more variables. An example: "If we increase the number of new users who join our platform by 25%, then we will see an increase in revenue."

3. What is an example of null hypothesis?

A null hypothesis is a statement that there is no relationship between two variables. The null hypothesis is written as H0. The null hypothesis states that there is no effect. For example, if you're studying whether or not a particular type of exercise increases strength, your null hypothesis will be "there is no difference in strength between people who exercise and people who don't."

4. What are the types of research?

• Fundamental research

• Applied research

• Qualitative research

• Quantitative research

• Mixed research

• Exploratory research

• Longitudinal research

• Cross-sectional research

• Field research

• Laboratory research

• Fixed research

• Flexible research

• Action research

• Policy research

• Classification research

• Comparative research

• Causal research

• Inductive research

• Deductive research

5. How to write a hypothesis?

• Your hypothesis should be able to predict the relationship and outcome.

• Avoid wordiness by keeping it simple and brief.

• Your hypothesis should contain observable and testable outcomes.

• Your hypothesis should be relevant to the research question.

6. What are the 2 types of hypothesis?

• Null hypotheses are used to test the claim that "there is no difference between two groups of data".

• Alternative hypotheses test the claim that "there is a difference between two data groups".

7. Difference between research question and research hypothesis?

A research question is a broad, open-ended question you will try to answer through your research. A hypothesis is a statement based on prior research or theory that you expect to be true due to your study. Example - Research question: What are the factors that influence the adoption of the new technology? Research hypothesis: There is a positive relationship between age, education and income level with the adoption of the new technology.

8. What is plural for hypothesis?

The plural of hypothesis is hypotheses. Here's an example of how it would be used in a statement, "Numerous well-considered hypotheses are presented in this part, and they are supported by tables and figures that are well-illustrated."

9. What is the red queen hypothesis?

The red queen hypothesis in evolutionary biology states that species must constantly evolve to avoid extinction because if they don't, they will be outcompeted by other species that are evolving. Leigh Van Valen first proposed it in 1973; since then, it has been tested and substantiated many times.

10. Who is known as the father of null hypothesis?

The father of the null hypothesis is Sir Ronald Fisher. He published a paper in 1925 that introduced the concept of null hypothesis testing, and he was also the first to use the term itself.

11. When to reject null hypothesis?

You need to find a significant difference between your two populations to reject the null hypothesis. You can determine that by running statistical tests such as an independent sample t-test or a dependent sample t-test. You should reject the null hypothesis if the p-value is less than 0.05.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing

7.4 Qualitative Research

Learning objectives.

- List several ways in which qualitative research differs from quantitative research in psychology.

- Describe the strengths and weaknesses of qualitative research in psychology compared with quantitative research.

- Give examples of qualitative research in psychology.

What Is Qualitative Research?

This book is primarily about quantitative research Research that involves formulating focused research questions, collecting small amounts of data from a large number of participants, and summarizing the data using descriptive and inferential statistics. . Quantitative researchers typically start with a focused research question or hypothesis, collect a small amount of data from each of a large number of individuals, describe the resulting data using statistical techniques, and draw general conclusions about some large population. Although this is by far the most common approach to conducting empirical research in psychology, there is an important alternative called qualitative research. Qualitative research originated in the disciplines of anthropology and sociology but is now used to study many psychological topics as well. Qualitative researchers generally begin with a less focused research question, collect large amounts of relatively “unfiltered” data from a relatively small number of individuals, and describe their data using nonstatistical techniques. They are usually less concerned with drawing general conclusions about human behavior than with understanding in detail the experience of their research participants.

Consider, for example, a study by researcher Per Lindqvist and his colleagues, who wanted to learn how the families of teenage suicide victims cope with their loss (Lindqvist, Johansson, & Karlsson, 2008). Lindqvist, P., Johansson, L., & Karlsson, U. (2008). In the aftermath of teenage suicide: A qualitative study of the psychosocial consequences for the surviving family members. BMC Psychiatry, 8 , 26. Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/8/26 They did not have a specific research question or hypothesis, such as, What percentage of family members join suicide support groups? Instead, they wanted to understand the variety of reactions that families had, with a focus on what it is like from their perspectives. To do this, they interviewed the families of 10 teenage suicide victims in their homes in rural Sweden. The interviews were relatively unstructured, beginning with a general request for the families to talk about the victim and ending with an invitation to talk about anything else that they wanted to tell the interviewer. One of the most important themes that emerged from these interviews was that even as life returned to “normal,” the families continued to struggle with the question of why their loved one committed suicide. This struggle appeared to be especially difficult for families in which the suicide was most unexpected.

The Purpose of Qualitative Research

Again, this book is primarily about quantitative research in psychology. The strength of quantitative research is its ability to provide precise answers to specific research questions and to draw general conclusions about human behavior. This is how we know that people have a strong tendency to obey authority figures, for example, or that female college students are not substantially more talkative than male college students. But while quantitative research is good at providing precise answers to specific research questions, it is not nearly as good at generating novel and interesting research questions. Likewise, while quantitative research is good at drawing general conclusions about human behavior, it is not nearly as good at providing detailed descriptions of the behavior of particular groups in particular situations. And it is not very good at all at communicating what it is actually like to be a member of a particular group in a particular situation.

But the relative weaknesses of quantitative research are the relative strengths of qualitative research. Qualitative research can help researchers to generate new and interesting research questions and hypotheses. The research of Lindqvist and colleagues, for example, suggests that there may be a general relationship between how unexpected a suicide is and how consumed the family is with trying to understand why the teen committed suicide. This relationship can now be explored using quantitative research. But it is unclear whether this question would have arisen at all without the researchers sitting down with the families and listening to what they themselves wanted to say about their experience. Qualitative research can also provide rich and detailed descriptions of human behavior in the real-world contexts in which it occurs. Among qualitative researchers, this is often referred to as “thick description” (Geertz, 1973). Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures . New York, NY: Basic Books. Similarly, qualitative research can convey a sense of what it is actually like to be a member of a particular group or in a particular situation—what qualitative researchers often refer to as the “lived experience” of the research participants. Lindqvist and colleagues, for example, describe how all the families spontaneously offered to show the interviewer the victim’s bedroom or the place where the suicide occurred—revealing the importance of these physical locations to the families. It seems unlikely that a quantitative study would have discovered this.

Data Collection and Analysis in Qualitative Research

As with correlational research, data collection approaches in qualitative research are quite varied and can involve naturalistic observation, archival data, artwork, and many other things. But one of the most common approaches, especially for psychological research, is to conduct interviews A data collection method in qualitative research. Interviews can be structured, semistructured, or unstructured—depending on how well specified the sequence of questions or prompts is. . Interviews in qualitative research tend to be unstructured—consisting of a small number of general questions or prompts that allow participants to talk about what is of interest to them. The researcher can follow up by asking more detailed questions about the topics that do come up. Such interviews can be lengthy and detailed, but they are usually conducted with a relatively small sample. This was essentially the approach used by Lindqvist and colleagues in their research on the families of suicide survivors. Small groups of people who participate together in interviews focused on a particular topic or issue are often referred to as focus groups A small group of people who participate together in an interview focused on a particular topic or issue. . The interaction among participants in a focus group can sometimes bring out more information than can be learned in a one-on-one interview. The use of focus groups has become a standard technique in business and industry among those who want to understand consumer tastes and preferences. The content of all focus group interviews is usually recorded and transcribed to facilitate later analyses.

Another approach to data collection in qualitative research is participant observation. In participant observation An approach to data collection in qualitative research in which the researcher becomes an active participant in the group or situation under study. , researchers become active participants in the group or situation they are studying. The data they collect can include interviews (usually unstructured), their own notes based on their observations and interactions, documents, photographs, and other artifacts. The basic rationale for participant observation is that there may be important information that is only accessible to, or can be interpreted only by, someone who is an active participant in the group or situation. An example of participant observation comes from a study by sociologist Amy Wilkins (published in Social Psychology Quarterly ) on a college-based religious organization that emphasized how happy its members were (Wilkins, 2008). Wilkins, A. (2008). “Happier than Non-Christians”: Collective emotions and symbolic boundaries among evangelical Christians. Social Psychology Quarterly, 71 , 281–301. Wilkins spent 12 months attending and participating in the group’s meetings and social events, and she interviewed several group members. In her study, Wilkins identified several ways in which the group “enforced” happiness—for example, by continually talking about happiness, discouraging the expression of negative emotions, and using happiness as a way to distinguish themselves from other groups.

Data Analysis in Quantitative Research

Although quantitative and qualitative research generally differ along several important dimensions (e.g., the specificity of the research question, the type of data collected), it is the method of data analysis that distinguishes them more clearly than anything else. To illustrate this idea, imagine a team of researchers that conducts a series of unstructured interviews with recovering alcoholics to learn about the role of their religious faith in their recovery. Although this sounds like qualitative research, imagine further that once they collect the data, they code the data in terms of how often each participant mentions God (or a “higher power”), and they then use descriptive and inferential statistics to find out whether those who mention God more often are more successful in abstaining from alcohol. Now it sounds like quantitative research. In other words, the quantitative-qualitative distinction depends more on what researchers do with the data they have collected than with why or how they collected the data.

But what does qualitative data analysis look like? Just as there are many ways to collect data in qualitative research, there are many ways to analyze data. Here we focus on one general approach called grounded theory An approach to analyzing qualitative data in which repeating ideas are identified and grouped into broader themes. The themes are integrated in a theoretical narrative. (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . Chicago, IL: Aldine. This approach was developed within the field of sociology in the 1960s and has gradually gained popularity in psychology. Remember that in quantitative research, it is typical for the researcher to start with a theory, derive a hypothesis from that theory, and then collect data to test that specific hypothesis. In qualitative research using grounded theory, researchers start with the data and develop a theory or an interpretation that is “grounded in” those data. They do this in stages. First, they identify ideas that are repeated throughout the data. Then they organize these ideas into a smaller number of broader themes. Finally, they write a theoretical narrative In grounded theory, a narrative interpretation of the broad themes that emerge from the data, usually supported by many direct quotations or examples from the data. —an interpretation—of the data in terms of the themes that they have identified. This theoretical narrative focuses on the subjective experience of the participants and is usually supported by many direct quotations from the participants themselves.

As an example, consider a study by researchers Laura Abrams and Laura Curran, who used the grounded theory approach to study the experience of postpartum depression symptoms among low-income mothers (Abrams & Curran, 2009). Abrams, L. S., & Curran, L. (2009). “And you’re telling me not to stress?” A grounded theory study of postpartum depression symptoms among low-income mothers. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33 , 351–362. Their data were the result of unstructured interviews with 19 participants. Table 7.1 "Themes and Repeating Ideas in a Study of Postpartum Depression Among Low-Income Mothers" shows the five broad themes the researchers identified and the more specific repeating ideas that made up each of those themes. In their research report, they provide numerous quotations from their participants, such as this one from “Destiny:”

Well, just recently my apartment was broken into and the fact that his Medicaid for some reason was cancelled so a lot of things was happening within the last two weeks all at one time. So that in itself I don’t want to say almost drove me mad but it put me in a funk.…Like I really was depressed. (p. 357)

Their theoretical narrative focused on the participants’ experience of their symptoms not as an abstract “affective disorder” but as closely tied to the daily struggle of raising children alone under often difficult circumstances.

Table 7.1 Themes and Repeating Ideas in a Study of Postpartum Depression Among Low-Income Mothers

The Quantitative-Qualitative “Debate”

Given their differences, it may come as no surprise that quantitative and qualitative research in psychology and related fields do not coexist in complete harmony. Some quantitative researchers criticize qualitative methods on the grounds that they lack objectivity, are difficult to evaluate in terms of reliability and validity, and do not allow generalization to people or situations other than those actually studied. At the same time, some qualitative researchers criticize quantitative methods on the grounds that they overlook the richness of human behavior and experience and instead answer simple questions about easily quantifiable variables.

In general, however, qualitative researchers are well aware of the issues of objectivity, reliability, validity, and generalizability. In fact, they have developed a number of frameworks for addressing these issues (which are beyond the scope of our discussion). And in general, quantitative researchers are well aware of the issue of oversimplification. They do not believe that all human behavior and experience can be adequately described in terms of a small number of variables and the statistical relationships among them. Instead, they use simplification as a strategy for uncovering general principles of human behavior.

Many researchers from both the quantitative and qualitative camps now agree that the two approaches can and should be combined into what has come to be called mixed-methods research Research that uses both quantitative and qualitative methods. (Todd, Nerlich, McKeown, & Clarke, 2004). Todd, Z., Nerlich, B., McKeown, S., & Clarke, D. D. (2004) Mixing methods in psychology: The integration of qualitative and quantitative methods in theory and practice . London, UK: Psychology Press. (In fact, the studies by Lindqvist and colleagues and by Abrams and Curran both combined quantitative and qualitative approaches.) One approach to combining quantitative and qualitative research is to use qualitative research for hypothesis generation and quantitative research for hypothesis testing. Again, while a qualitative study might suggest that families who experience an unexpected suicide have more difficulty resolving the question of why, a well-designed quantitative study could test a hypothesis by measuring these specific variables for a large sample. A second approach to combining quantitative and qualitative research is referred to as triangulation In mixed methods research, using multiple quantitative and qualitative methods to study the same topic, with the goal of converging on a single interpretation. . The idea is to use both quantitative and qualitative methods simultaneously to study the same general questions and to compare the results. If the results of the quantitative and qualitative methods converge on the same general conclusion, they reinforce and enrich each other. If the results diverge, then they suggest an interesting new question: Why do the results diverge and how can they be reconciled?

Key Takeaways

- Qualitative research is an important alternative to quantitative research in psychology. It generally involves asking broader research questions, collecting more detailed data (e.g., interviews), and using nonstatistical analyses.

- Many researchers conceptualize quantitative and qualitative research as complementary and advocate combining them. For example, qualitative research can be used to generate hypotheses and quantitative research to test them.

- Discussion: What are some ways in which a qualitative study of girls who play youth baseball would be likely to differ from a quantitative study on the same topic?

Chapter 5. Sampling

Introduction.

Most Americans will experience unemployment at some point in their lives. Sarah Damaske ( 2021 ) was interested in learning about how men and women experience unemployment differently. To answer this question, she interviewed unemployed people. After conducting a “pilot study” with twenty interviewees, she realized she was also interested in finding out how working-class and middle-class persons experienced unemployment differently. She found one hundred persons through local unemployment offices. She purposefully selected a roughly equal number of men and women and working-class and middle-class persons for the study. This would allow her to make the kinds of comparisons she was interested in. She further refined her selection of persons to interview:

I decided that I needed to be able to focus my attention on gender and class; therefore, I interviewed only people born between 1962 and 1987 (ages 28–52, the prime working and child-rearing years), those who worked full-time before their job loss, those who experienced an involuntary job loss during the past year, and those who did not lose a job for cause (e.g., were not fired because of their behavior at work). ( 244 )

The people she ultimately interviewed compose her sample. They represent (“sample”) the larger population of the involuntarily unemployed. This “theoretically informed stratified sampling design” allowed Damaske “to achieve relatively equal distribution of participation across gender and class,” but it came with some limitations. For one, the unemployment centers were located in primarily White areas of the country, so there were very few persons of color interviewed. Qualitative researchers must make these kinds of decisions all the time—who to include and who not to include. There is never an absolutely correct decision, as the choice is linked to the particular research question posed by the particular researcher, although some sampling choices are more compelling than others. In this case, Damaske made the choice to foreground both gender and class rather than compare all middle-class men and women or women of color from different class positions or just talk to White men. She leaves the door open for other researchers to sample differently. Because science is a collective enterprise, it is most likely someone will be inspired to conduct a similar study as Damaske’s but with an entirely different sample.

This chapter is all about sampling. After you have developed a research question and have a general idea of how you will collect data (observations or interviews), how do you go about actually finding people and sites to study? Although there is no “correct number” of people to interview, the sample should follow the research question and research design. You might remember studying sampling in a quantitative research course. Sampling is important here too, but it works a bit differently. Unlike quantitative research, qualitative research involves nonprobability sampling. This chapter explains why this is so and what qualities instead make a good sample for qualitative research.

Quick Terms Refresher

- The population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about.

- The sample is the specific group of individuals that you will collect data from.

- Sampling frame is the actual list of individuals that the sample will be drawn from. Ideally, it should include the entire target population (and nobody who is not part of that population).

- Sample size is how many individuals (or units) are included in your sample.

The “Who” of Your Research Study

After you have turned your general research interest into an actual research question and identified an approach you want to take to answer that question, you will need to specify the people you will be interviewing or observing. In most qualitative research, the objects of your study will indeed be people. In some cases, however, your objects might be content left by people (e.g., diaries, yearbooks, photographs) or documents (official or unofficial) or even institutions (e.g., schools, medical centers) and locations (e.g., nation-states, cities). Chances are, whatever “people, places, or things” are the objects of your study, you will not really be able to talk to, observe, or follow every single individual/object of the entire population of interest. You will need to create a sample of the population . Sampling in qualitative research has different purposes and goals than sampling in quantitative research. Sampling in both allows you to say something of interest about a population without having to include the entire population in your sample.

We begin this chapter with the case of a population of interest composed of actual people. After we have a better understanding of populations and samples that involve real people, we’ll discuss sampling in other types of qualitative research, such as archival research, content analysis, and case studies. We’ll then move to a larger discussion about the difference between sampling in qualitative research generally versus quantitative research, then we’ll move on to the idea of “theoretical” generalizability, and finally, we’ll conclude with some practical tips on the correct “number” to include in one’s sample.

Sampling People

To help think through samples, let’s imagine we want to know more about “vaccine hesitancy.” We’ve all lived through 2020 and 2021, and we know that a sizable number of people in the United States (and elsewhere) were slow to accept vaccines, even when these were freely available. By some accounts, about one-third of Americans initially refused vaccination. Why is this so? Well, as I write this in the summer of 2021, we know that some people actively refused the vaccination, thinking it was harmful or part of a government plot. Others were simply lazy or dismissed the necessity. And still others were worried about harmful side effects. The general population of interest here (all adult Americans who were not vaccinated by August 2021) may be as many as eighty million people. We clearly cannot talk to all of them. So we will have to narrow the number to something manageable. How can we do this?

First, we have to think about our actual research question and the form of research we are conducting. I am going to begin with a quantitative research question. Quantitative research questions tend to be simpler to visualize, at least when we are first starting out doing social science research. So let us say we want to know what percentage of each kind of resistance is out there and how race or class or gender affects vaccine hesitancy. Again, we don’t have the ability to talk to everyone. But harnessing what we know about normal probability distributions (see quantitative methods for more on this), we can find this out through a sample that represents the general population. We can’t really address these particular questions if we only talk to White women who go to college with us. And if you are really trying to generalize the specific findings of your sample to the larger population, you will have to employ probability sampling , a sampling technique where a researcher sets a selection of a few criteria and chooses members of a population randomly. Why randomly? If truly random, all the members have an equal opportunity to be a part of the sample, and thus we avoid the problem of having only our friends and neighbors (who may be very different from other people in the population) in the study. Mathematically, there is going to be a certain number that will be large enough to allow us to generalize our particular findings from our sample population to the population at large. It might surprise you how small that number can be. Election polls of no more than one thousand people are routinely used to predict actual election outcomes of millions of people. Below that number, however, you will not be able to make generalizations. Talking to five people at random is simply not enough people to predict a presidential election.

In order to answer quantitative research questions of causality, one must employ probability sampling. Quantitative researchers try to generalize their findings to a larger population. Samples are designed with that in mind. Qualitative researchers ask very different questions, though. Qualitative research questions are not about “how many” of a certain group do X (in this case, what percentage of the unvaccinated hesitate for concern about safety rather than reject vaccination on political grounds). Qualitative research employs nonprobability sampling . By definition, not everyone has an equal opportunity to be included in the sample. The researcher might select White women they go to college with to provide insight into racial and gender dynamics at play. Whatever is found by doing so will not be generalizable to everyone who has not been vaccinated, or even all White women who have not been vaccinated, or even all White women who have not been vaccinated who are in this particular college. That is not the point of qualitative research at all. This is a really important distinction, so I will repeat in bold: Qualitative researchers are not trying to statistically generalize specific findings to a larger population . They have not failed when their sample cannot be generalized, as that is not the point at all.

In the previous paragraph, I said it would be perfectly acceptable for a qualitative researcher to interview five White women with whom she goes to college about their vaccine hesitancy “to provide insight into racial and gender dynamics at play.” The key word here is “insight.” Rather than use a sample as a stand-in for the general population, as quantitative researchers do, the qualitative researcher uses the sample to gain insight into a process or phenomenon. The qualitative researcher is not going to be content with simply asking each of the women to state her reason for not being vaccinated and then draw conclusions that, because one in five of these women were concerned about their health, one in five of all people were also concerned about their health. That would be, frankly, a very poor study indeed. Rather, the qualitative researcher might sit down with each of the women and conduct a lengthy interview about what the vaccine means to her, why she is hesitant, how she manages her hesitancy (how she explains it to her friends), what she thinks about others who are unvaccinated, what she thinks of those who have been vaccinated, and what she knows or thinks she knows about COVID-19. The researcher might include specific interview questions about the college context, about their status as White women, about the political beliefs they hold about racism in the US, and about how their own political affiliations may or may not provide narrative scripts about “protective whiteness.” There are many interesting things to ask and learn about and many things to discover. Where a quantitative researcher begins with clear parameters to set their population and guide their sample selection process, the qualitative researcher is discovering new parameters, making it impossible to engage in probability sampling.

Looking at it this way, sampling for qualitative researchers needs to be more strategic. More theoretically informed. What persons can be interviewed or observed that would provide maximum insight into what is still unknown? In other words, qualitative researchers think through what cases they could learn the most from, and those are the cases selected to study: “What would be ‘bias’ in statistical sampling, and therefore a weakness, becomes intended focus in qualitative sampling, and therefore a strength. The logic and power of purposeful sampling like in selecting information-rich cases for study in depth. Information-rich cases are those from which one can learn a great deal about issues of central importance to the purpose of the inquiry, thus the term purposeful sampling” ( Patton 2002:230 ; emphases in the original).

Before selecting your sample, though, it is important to clearly identify the general population of interest. You need to know this before you can determine the sample. In our example case, it is “adult Americans who have not yet been vaccinated.” Depending on the specific qualitative research question, however, it might be “adult Americans who have been vaccinated for political reasons” or even “college students who have not been vaccinated.” What insights are you seeking? Do you want to know how politics is affecting vaccination? Or do you want to understand how people manage being an outlier in a particular setting (unvaccinated where vaccinations are heavily encouraged if not required)? More clearly stated, your population should align with your research question . Think back to the opening story about Damaske’s work studying the unemployed. She drew her sample narrowly to address the particular questions she was interested in pursuing. Knowing your questions or, at a minimum, why you are interested in the topic will allow you to draw the best sample possible to achieve insight.