What is an economic crisis? Definition and examples

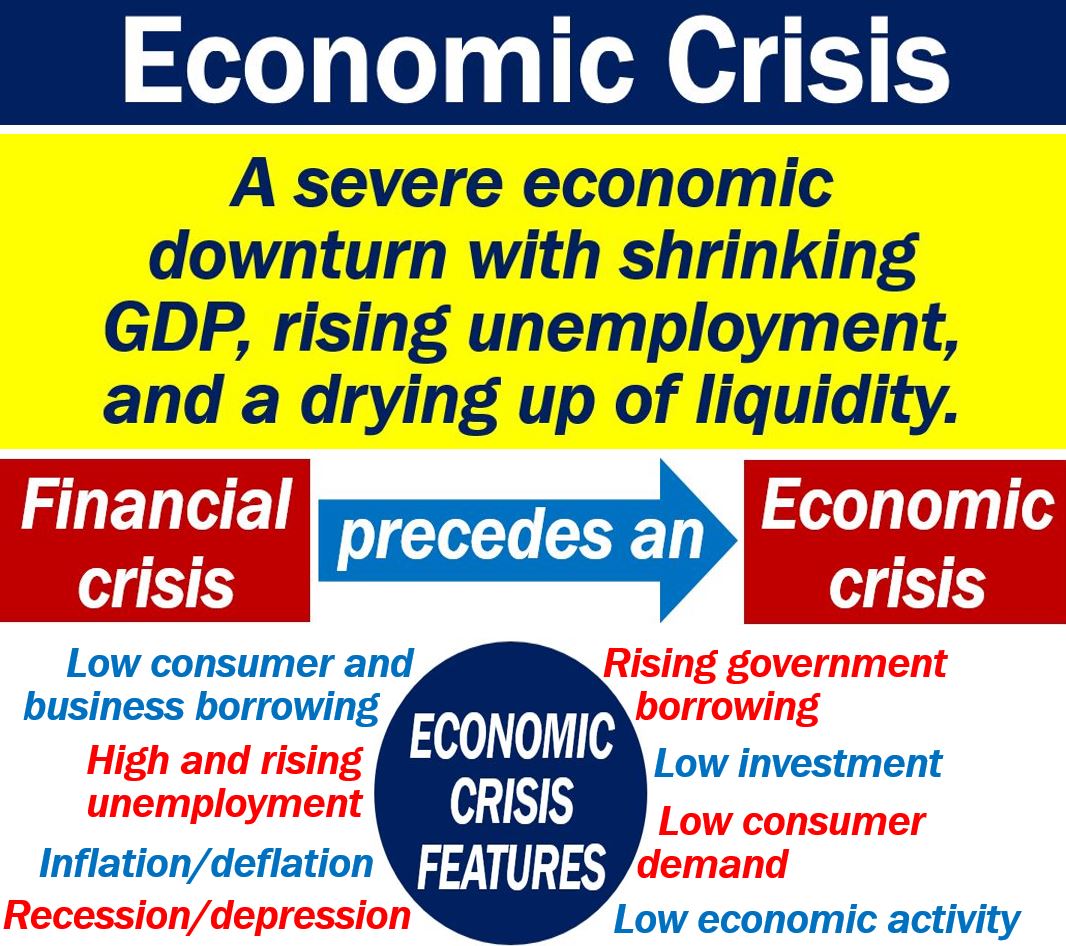

An Economic Crisis is a situation in which a country’s economy deteriorates significantly. We also call it a real economic crisis . In most cases, a financial crisis is the cause of an economic crisis. Typically preceded by a period of excessive debt accumulation and speculative investments, an economic crisis often manifests after such financial bubbles burst.

During the crisis, GDP is typically declining, liquidity dries up, and property and stock market prices plummet. It is an economic downturn that gets worse and worse.

GDP stands for Gr oss D omestic P roduct . GDP is the sum of everything a country produces over a specific period.

Economic downturn refers to slowing GDP growth or GDP contraction. During a downturn, property prices fall, joblessness rises, borrowing falls, and companies invest less.

When an economic crisis is devastating, there is a depression. When it is serious, but not as devastating, it is a recession . Recessions and depressions are similar. In both cases, the economy declines, and unemployment rises. However, a depression is more severe and usually longer-lasting.

India Today has the following definition of the term:

“An economic crisis occurs when a country’s economy faces a sharp downturn as a result of a financial crisis. Under an economy in crisis, GDP will most likely decline, liquidity will dry up, and prices will rise or fall due to inflation or deflation. A recession or depression are two types of economic crises.”

Economists say that a recession is a normal phase of the business cycle. If we can manage the downturn properly, however, we can prevent it from becoming an economic crisis or depression.

Economic crisis vs. financial crisis

We often see the terms economic crisis and financial crisis in history books, newspapers, and business journals. Although the two terms have similar meanings, they are not the same.

Financial crisis

A financial crisis typically involves problems in the banking and finance sector. Banks, financial institutions, the currency market, and the capital markets, for example, are part of the banking and finance sector.

If a country’s major bank collapses, this is a financial crisis, especially if other banks also start crashing. It is also a financial crisis if a significant number of borrowers default on their debts (fail to pay back what they borrowed).

If these problems continue, the problem will start influencing macroeconomic conditions. Macroeconomics refers to things that span the whole economy , such as GDP growth, unemployment, and inflation. A significant rise in interest rates is also a macroeconomic issue.

A global financial crisis is a financial crisis that affects several countries simultaneously . During global financial crises, financial institutions lose faith. Subsequently, they stop lending to each other and traders stop purchasing financial instruments. Most lending eventually dries up, and businesses suffer considerably.

The last global financial crisis occurred in 2007/8. We call it the 2008 Global Financial Crisis or 2008 Financial Crisis .

Economic crisis

As mentioned above, if the financial crisis worsens and spreads, it will eventually affect macroeconomic conditions. When this happens, the financial crisis starts turning into an economic crisis.

Unlike a financial crisis, which is limited to one sector, an economic crisis affects the whole economy. Unemployment rises, GDP stops growing or shrinks, and many other things go wrong.

Put simply; if the authorities and those responsible do not address a financial crisis properly, it can turn into an economic crisis.

An unchecked economic crisis can lead to disruptions in global supply chains and exacerbate geopolitical tensions as nations struggle to stabilize their economies.

“Economic crisis” vocabulary

There are many compound nouns in the English language that contain the words “economic crisis.” A compound noun is a term that consists of two or more words. Let’s have a look at some of them, their meanings, and how we can use them in a sentence:

Economic Crisis Management

The strategies and measures employed by governments and financial institutions to mitigate the impact of an economic crisis. Example: “The government’s economic crisis management plan included tax reliefs and increased public spending to stimulate the economy.”

Economic Crisis Response

The immediate actions taken to address the initial effects of an economic crisis. Example: “The central bank’s economic crisis response was to lower interest rates and inject liquidity into the market.”

Economic Crisis Indicator

A statistical metric or sign that signals the potential or onset of an economic crisis. Example: “Sudden stock market crashes are often considered a reliable economic crisis indicator.”

Economic Crisis Impact

The effects and consequences that an economic crisis has on the broader economy, businesses, and individuals. Example: “Researchers studied the economic crisis impact on small businesses, which included reduced consumer spending and difficulty accessing credit.”

Economic Crisis Prevention

The policies and regulations designed to avoid the occurrence of an economic crisis. Example: “Economic crisis prevention measures often involve strict banking regulations and oversight of investment practices.”

Economic Crisis Recovery

The period of rebuilding and growth following an economic crisis. Example: “The country’s economic crisis recovery was marked by a gradual decrease in unemployment rates and stabilization of the housing market.”

Economic Crisis Policy

The set of rules and guidelines formulated by governments to navigate through an economic crisis. Example: “The new administration focused on creating a robust economic crisis policy to prepare for any future financial downturns.”

Video – What is an Economic Crisis?

This interesting video presentation, from our sister channel on YouTube – Marketing Business Network , explains what an ‘Economic Crisis’ is using simple and easy-to-understand language and examples.

Share this:

- Renewable Energy

- Artificial Intelligence

- 3D Printing

- Financial Glossary

Reimagining the global economy: Building back better in a post-COVID-19 world

- Download the full essay collection

Subscribe to Global Connection

November 17, 2020

The COVID-19 global pandemic has produced a human and economic crisis unlike any in recent memory. The global economy is experiencing its deepest recession since World War II, disrupting economic activity, travel, supply chains, and more. Governments have responded with lockdown measures and stimulus plans, but the extent of these actions has been unequal across countries. Within countries, the most vulnerable populations have been disproportionately affected, both in regard to job loss and the spread of the virus.

The implications of the crisis going forward are vast. Notwithstanding the recent announcement of vaccines, much is unknown about how the pandemic will spread in the short term and beyond, as well as what will be its lasting effects. What is clear, however, is that the time is ripe for change and policy reform. The hope is that decisionmakers can rise to the challenge in the medium term to tackle the COVID-19 virus and related challenges that the pandemic has exacerbated—be it the climate crisis, rising inequality, job insecurity, or international cooperation.

In this collection of 12 essays, leading scholars affiliated with the Global Economy and Development program at Brookings present new ideas that are forward-looking, policy-focused, and that will guide policies and shape debates in a post-COVID-19 world.

Sustainable Development Goals

Authors: Homi Kharas , John W. McArthur

Some have questioned whether the pandemic has put attaining the already ambitious 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) out of reach, and whether they should be scaled back and deprioritized. In this essay, Homi Kharas and John McArthur argue that the SDGs remain as relevant as ever and that the goals can in fact provide a handrail for recovery policy.

Continue reading

Leadership at the local level

Authors: Anthony F. Pipa , Max Bouchet

The pandemic has revealed the importance of good leadership at the local level. In this essay, Anthony F. Pipa and Max Bouchet explore the role that global cities can have in driving a sustainable recovery.

Multilateralism

Authors: Kemal Derviş

Given the global nature of the pandemic, there have been calls for greater international cooperation. In this essay, Kemal Derviş examines the state of multilateralism and presents lessons of caution as its future is reimagined.

Rebooting the climate agenda

Authors: Amar Bhattacharya

Shared recognition of the climate agenda is central to global cooperation. In this essay, Amar Bhattacharya explores how international action can pursue a recovery that produces sustainable, inclusive, and resilient growth.

The international monetary and financial system

Authors: Brahima Sangafowa Coulibaly , Eswar Prasad

The pandemic has exposed the weaknesses in the international financial system and the need to improve the financial safety net for emerging and developing countries. In this essay, Brahima Coulibaly and Eswar Prasad make the case for an international monetary and financial system that is fit for purpose to help countries better withstand shocks like a global pandemic.

The future of global supply chains

Authors: David Dollar

International trade has slowed, and existing trade challenges, including automation, new data flows, and the rise of protectionism, could accelerate post-COVID. In this essay, David Dollar discusses these challenges, the future of global supply chains, and the implications for international trade.

The global productivity slump

Authors: Alistair Dieppe , M. Ayhan Kose

COVID-19 could further accelerate the fall in global productivity, which has been slowing since the global financial crisis. Evidence from other recent pandemics such as SARS and Ebola show their negative impact on investment growth and productivity. In this essay, Alistair Dieppe and Ayhan Kose argue that policy approaches to boost productivity must be country-specific and well-targeted.

Dislocation of labor markets

Authors: Marcela Escobari , Eduardo Levy Yeyati

Throughout the world, the health and economic costs of the pandemic have been felt harder by less well-off populations. On the jobs front, the pandemic is affecting labor markets differently across and within advanced and developing countries as low-wage, high-contact jobs are disproportionally affected. In this essay, Marcela Escobari and Eduardo Levy Yeyati explore the future of work and policies for formalizing and broadening labor protections to bolster resiliency.

Tackling the inequality pandemic

Authors: Zia Qureshi

Technology, globalization, and weakening redistribution policies are leading to rising inequality in many countries. To tackle inequality, Zia Qureshi discusses policies to better harness technology for fostering inclusive economic growth.

The human costs of the pandemic

Authors: Carol Graham

Evidence suggests that the poor have been suffering higher emotional costs during the pandemic. In this essay, Carol Graham offers a look into well-being measurement and strategies to combat the effects of the lockdowns.

The complexity of managing COVID-19

Authors: Alaka M. Basu , Kaushik Basu , Jose Maria U. Tapia

From strict lockdowns to ensuring sufficient supplies of personal protective equipment to sending students home from school, governments around the world have enacted varying measures to respond to the virus. In this essay, Alaka M. Basu, Kaushik Basu, and Jose Maria U. Tapia examine how governments in emerging markets have managed the crisis so far, as they design governance strategies that both reduce the spread of infection and avoid prohibiting economic activity.

Global education

Authors: Emiliana Vegas , Rebecca Winthrop

COVID-19 disrupted education systems everywhere and has accelerated education inequality as seen through what service governments could provide: At one point during the pandemic, 1 in 4 low-income countries was able to provide remote education, while 9 in 10 high-income countries were able to. In this essay, Emiliana Vegas and Rebecca Winthrop present an aspirational vision for transforming education systems to better serve all children.

Global Trade Sustainable Development Goals

Global Economy and Development

The Brookings Institution, Washington DC

10:00 am - 11:30 am EDT

Kevin Dong, Mallie Prytherch, Lily McElwee, Patricia M. Kim, Jude Blanchette, Ryan Hass

March 15, 2024

March 6, 2024

The Global Economic Crisis: Historical Roots, Lessons Learned, and Implications for Geopolitical Stability

- First Online: 17 June 2023

Cite this chapter

- Ioannis-Dionysios Salavrakos 2 &

- Allison L. Palmadessa 3

366 Accesses

This chapter considers the origins of the current global economic crisis, the lessons learned from past crises, and how the pandemic-created economic crisis influences more than finance and monetary policy, but has implications for geopolitical stability. The current global financial crisis attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic is far more complex than simply a response to the Great Lockdown. Rather, the current crisis is rooted in the Great Recession of 2007–2009, and the resulting Global Financial Crisis of 2009–2016 that we argue did not end in 2016 but continued into the current crisis, serving as a means to reveal the structural changes in the international economic system that were only exacerbated by the pandemic context. The economic crises of the twenty-first century to date are analyzed and juxtaposed against the twentieth-century crises as a means to understand the roots of the structural issues. Thus providing a reminder for leaders and policymakers to consider decisions of the past to avoid an extreme socio-political outcome paralleling that of the post-Great Depression world.

- Great recession

- Global financial crisis

- Great lockdown

- Maastricht treaty

- 2007 Treaty of Lisbon

- Euro-zone debt crisis

- COVID-19 pandemic

- Post-depression

- Great depression

- Unemployment

- Global health crisis

- Global economic crisis

- The Treaty of the European Union (TEU), also known as Treaty of Maastricht

- Treaty of Lisbon

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bibliography

Admati, A., & Hellwig, M. (2013). The bankers new clothes. What is wrong with Banking and what to do about it . Princeton University Press.

Google Scholar

Angelides, P., & Thomas, B. (2011). The financial crisis inquiry report: Final report of the National Commission on the Causes of the Financial and Economic Crisis in the United States . Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission.

Baker, D. (2007, May). The economic impact of the Iraq War and higher military spending . Center for Economic and Policy Research.

Bloomberg News. (2013). PBOC says no longer in China’s interest to increase reserves. Bloomberg News . https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-11-20/pboc-says-no-longer-in-china-s-favor-to-boost-record-reserves#xj4y7vzkg3

Booker, C., & North, R. (2003). The great deception. The Secret History of the European Union . Continuum.

Branson, W. H., Giersch, H., & Peterson, P. G. (1980). Trends in United States international trade and investment since World War II. In M. Feldstein (Ed.), The American economy in transition . University of Chicago Press.

Brown, G. (2011). Beyond the crash: Overcoming the first crisis of globalisation . Simon & Schuster.

Bush, G. W. (2010). Decision points . Virgin Books.

Camera, L. (2021, January 20). Biden’s surreal transition to power inside fortress Washington. US News and World Report. https://www.usnews.com/news/elections/articles/2021-01-20/bidens-surreal-transition-to-power-inside-fortress-washington

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, September 9). COVID-19 vaccine equity for racial and ethnic minority groups. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/vaccine-equity.html

Charles, H. R. H. Prince. (2007, October 25). Speech of the heir to the British throne, Prince Charles, at Hampton Court Palace. https://www.princeofwales.gov/uk

CoinDesk. (2020). https://wwwcoindesk.com

Davidson, I., & Weil, G. (1970). The Gold War: The secret battle for financial and political domination from 1945 onwards . Secker & Warburg.

De Gaulle, C. (1963, January 14). French President Charles DeGaulle’s Veto on British Membership of the EEC . Available from International Relations and Security Network, Primary Resources in International Affairs. https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/125401/1168_DeGaulleVeto.pdf

Delors, J. (1990). Report on the economic and monetary union in the European Community. https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/pages/publication6161_en.pdf

Detrow, S., & Summers, J. (2021, January 6). Biden: Democracy “under unprecedented assault” as pro-Trump extremists occupy Capitol. National Public Radio . https://www.npr.org/sections/congress-electoral-college-tally-live-updates/2021/01/06/954063529/watch-live-joe-biden-speaks-as-protesters-force-u-s-capitol-into-lockdown

European Central Bank. (2021). Non performing loans data . https://sdw.ecb.europa.eu/quickview.do?SERIES_KEY=420.SUP.Q.B01.W0._Z.I7000._T._Z._Z._Z._Z.PCT.C

Falk, G. (2021, August 20). Unemployment rates during the Covid-19 pandemic . Congressional Research Services. https://crsreports.congress.gov R46554

Ferguson, N. (2012). The great degeneration . Allen Lane.

Freeman, K. (2012). Secret weapon: How economic terrorism brought down the US stock market and why it can happen again . Regency.

Galbraith, J. K. (1975). The great crash 1929 . Penguin Books.

Gapper, J., & Denton, N. (1996). All that glitters: The fall of Barings . H-H Editions.

Getachew, Y., Zephyrin, L., Abrams, M. K., Shah, A., Lewis, C., & Doty, M. M. (2020, September 10). Beyond the case-count: The wide-ranging disparities of COVID-19 in the United States. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/sep/beyond-case-count-disparities-covid-19-united-states?gclid=CjwKCAiA78aNBhAlEiwA7B76p7L0x80YjaT6ZCpXBOkzGf77LGxTKAmvvQpXPTfLdBM4BqeKfxe2ThoCmvMQAvD_BwE#2

Harrison, B., & Bluestone, B. (1988). The great U-turn: Corporate restructuring and polarizing of America . Basic Books.

Hughes, J., & Cain, L. P. (1998). American economic history . Addison Wesley.

Jackson, J. K., Weiss, M. A., Schwarzenberg, A. B., Nelson, R. M., Sutter, K. M., & Sutherland, M. D. (2021, November 10). Global economic effects of COVID-19. Congressional Research Service . https://crsreports.congress.gov , R46270.

James, H., Lindgren, H., & Teichova, A. (Eds.). (2002). The role of banks in the interwar economy . Cambridge University Press.

James, L. (1998). The rise and fall of the British Empire . Abacus.

Kennedy, P. (1989). The rise and fall of Great Powers . Fontana Press.

Kremmidas, V. (1989). Introduction to the economic history of Europe . Gnosi Editions.

Mallaby, S. (2010). More money than god . Penguin Books.

Mesnard, B., Margerit, A., Power, C., & Magnus, M (2016, March 18). Non-performing loans in the Banking Union: Stocktaking and Challenges. European Parliament, Economic Governance Support Unit.

Morrison, W. M., & Labonte, M. (2013, August 19). China’s holdings of US Securities: Implications for the US economy. Congressional Research Paper.

Mundell, R. A. (1961). Theory of optimal currency areas. American Economic Review, 51 .

Panayiotou, P. (2012). Markets Tango . Livanis Editions.

Reinhart, C. M., & Rogoff, K. S. (2009). This time is different eight centuries of financial folly . Princeton University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Rhodes, C. (2016, August 18). Manufacturing: International comparisons. House of Commons British Parliament serial number 05809.

Rickards, J. (2011). Currency wars: The making of the next global crisis . Portfolio-Penguin Editions.

Stiglitz, J., & Bilmes, L. (2008). The three trillion dollar war . Allen Lane.

Stolper, G. (1967). The German economy: 1870 to the present . Harcourt & World.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2012) Social spending during the crisis. https://www.oecd.org

Trump, D. (2020). March 18 2020 remarks at a White House Coronavirus Task Force Press briefing. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-white-house-coronavirus-task-force-press-briefing-4

US Census Bureau. (2020). Quick facts. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/POP010220#POP010220

US Debt Clock. (2021). https://www.usdebtclock.org/

US Department of Labor Statistics. (2021). Unemployment rises in 2020, as the country battles the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2021/article/unemployment-rises-in-2020-as-the-country-battles-the-covid-19-pandemic.htm

U.S. Department of Treasury. (2016). Data 15 December 2016. http://ticdata.treasury.gov

Warde, I. (2007). The price of fear: Al Qaeda and the truth behind the financial war on terror . I.B. Tauris.

Warner, P. (1970). Report to the Council and the Commission on the Realisation by Stages of Economic and Monetary Union in the Community: Werner Report . Supplement to Bulletin 11, 1970, of the European Communities.

World Gold Council. (2021). https://www.gold.org

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

The University of Athens, Athens, Greece

Ioannis-Dionysios Salavrakos

Greensboro College, Greensboro, NC, USA

Allison L. Palmadessa

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Allison L. Palmadessa .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

IR Globe Cross-Cultural Inc, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Adebowale Akande

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Salavrakos, ID., Palmadessa, A.L. (2023). The Global Economic Crisis: Historical Roots, Lessons Learned, and Implications for Geopolitical Stability. In: Akande, A. (eds) Globalization, Human Rights and Populism. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-17203-8_43

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-17203-8_43

Published : 17 June 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-17202-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-17203-8

eBook Packages : Political Science and International Studies Political Science and International Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

The Honors College

Economic crisis.

Economic Crisis: Causes, Consequences, and Remedies

Spurred by the bursting of the housing bubble, the financial and market crisis that began in 2007 has wreaked havoc on the global economy. In the last five years, this crisis has seen the collapse of major financial institutions, bank and corporate bailouts, extraordinary volatility in stock markets, unprecedented numbers of foreclosures and job losses, and new austerity measures and regulations. And the uncertainty continues. This series of public lectures invites thinkers from a variety of perspectives to discuss the economic and political roots of the crisis, its historical precedents and origins, and potential remedies in moving forward. The series draws inspiration from the view that the time is ripe for fresh thinking about our political and economic future—a future dependent on innovative ideas that defy partisan and party divisions.

Upcoming Events - RSVP Now

Lawrence white - february 25.

George Mason University economist Lawrence H. White will speak on the topics covered in his book, The Clash of Economic Ideas: The Great Policy Debates and Experiments of the Last Hundred Years .

The Clash of Economic Ideas interweaves the economic history of the last hundred years with the history of economic doctrines to understand how contrasting economic ideas have originated and developed over time to take their present forms. It traces the connections running from historical events to debates among economists, and from the ideas of academic writers to major experiments in economic policy. The treatment offers fresh perspectives on laissez faire, socialism, and fascism; the Roaring Twenties, business cycle theories, and the Great Depression; Institutionalism and the New Deal; the Keynesian Revolution; and war, nationalization, and central planning. After 1945, the work explores the postwar revival of invisible-hand ideas; economic development and growth, with special attention to contrasting policies and thought in Germany and India; the gold standard, the interwar gold-exchange standard, the postwar Bretton Woods system, and the Great Inflation; public goods and public choice; free trade versus protectionism; and finally fiscal policy and public debt. The investigation analyzes the theories of Adam Smith and earlier writers on economics when those antecedents are useful for readers.

Lawrence H. White is Professor of Economics at George Mason University. He specializes in the theory and history of banking and money, and is best known for his work on free banking. He received his A.B. from Harvard and his M. A. and Ph.D. from the University of California, Los Angeles. He previously taught at New York University, the University of Georgia, and the University of Missouri - St. Louis.

Professor White is the author of The Clash of Economic Ideas (Cambridge, forthcoming); The Theory of Monetary Institutions (Basil Blackwell, 1999); Free Banking in Britain (2nd ed., Institute of Economic Affairs, 1995; 1st ed. Cambridge, 1984), and C ompetition and Currency (NYU, 1989). In 2008 White received the Distinguished Scholar Award of the Association for Private Enterprise Education. He has been Visiting Professor at Queen's University Belfast, Visiting Fellow at the Australian National University, Visiting Research Fellow and lecturer at the American Institute for Economic Research, visiting lecturer at the Swiss National Bank, and a visiting scholar at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. He co-edits a book series for Routledge, Foundations of the Market Economy . He is a co- editor of Econ Journal Watch, and hosts bi-monthly podcasts for EJW Audio. He is a member of the board of associate editors of the Review of Austrian Economics and a member of the editorial board of the Cato Journal. He is a contributing editor to the Foundation for Economic Education's magazine The Freeman and lectures at the Foundation's annual seminar in Advanced Austrian Economics. He is an adjunct scholar of the Cato Institute and a member of the Academic Advisory Council of the Institute of Economic Affairs.

Previous Events in the Series

February 24 - Lost Decades: The Making of America's Debt Crisis and the Long Recovery with Menzie Chinn , Professor of Public Affairs and Economics at the University of Wisconsin

The U.S. economy lost the first decade of the twenty-first century to an ill-conceived boom and subsequent bust. It is now in danger of losing another decade to the stagnation of an incomplete recovery. How did this happen? Menzie Chinn explains the political and economic roots of this crisis, as well as its long-term effects, including political strategies that led to the debt and the continuing impact of the huge U.S. public debt in the ongoing slow recovery from the recession.

With Jeffry Frieden, he is coauthor of Lost Decades: The Making of America's Debt Crisis and the Long Recovery (September 2011, W.W. Norton). He is also a contributor to Econbrowser , a weblog on macroeconomic issues.

April 4 - The Long Term Consequences of the Financial Crisis with John Allison , Retired CEO of Branch Banking and Trust & Distinguished Professor of Practice at Wake Forest

The American economy continues to suffer from the bursting of the housing bubble and subsequent collapse in the capital markets in spring of 2007. In this second talk in our series on the Economic Crisis, John Allison, retired CEO of Branch, Banking, & Trust, will discuss the causes of this crisis, including government policies and errors by financial institutions, and potential short and long-term solutions.

Allison is a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He received his master’s degree in management from Duke University (1974). He is also a graduate of the Stonier Graduate School of Banking and has received 6 Honorary Doctorate Degrees. Allison has received the Corning Award for Distinguished Leadership, been inducted into the NC Business Hall of Fame and received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Banker. He was recognized by the Harvard Business Review as one of the top 100 most successful CEOs in the world over the last decade. He serves on the Board of Visitors at the business schools at Wake Forest, Duke, and UNC-Chapel Hill, and the Board of Directors of the Clemson Institute for the Study of Capitalism and the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. A native of Charlotte, N.C., Allison is married to the former Elizabeth McDonald of Elkin, N.C. They have two sons and one daughter.

September 13 - Five Myths About America’s Future Economic Decline with Stephen Rose

In Five Myths About America’s Economic Decline , Georgetown Professor Stephen Rose will argue that our economic strengths are many and that our future is bright. The prolonged economic crisis has taken a severe toll but it will end within the next few years. While we have many problems that need addressing (high inequality, relatively poor elementary and HS education, and expensive health care system), we have the largest consumer market in the world by a wide margin, the best higher education system, and by international standards very good legal, financial, and regulatory institutions.

Stephen J. Rose is a Research Professor and Senior Economist at the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce where he studies the interactions between formal education, training, career movements, and earnings. Dr. Rose has coauthored three reports for the Center: The Undereducated American, The College Payoff, and Certificates: Gateway to Gainful Employment and College Degrees. He is a nationally recognized labor economist who has conducted innovative research and written about social class in America for the last 30 years and he is currently working on separate studies on certificates, graduate degrees, and community colleges. He is the author of Rebound: Why America Will Emerge Stronger From the Financial Crisis (2009, St. Martin's Press) .

- Arts & Culture

Get Involved

Autumn 2023

Annual Gala Dinner

Internships

Lebanon’s economic crisis: A tragedy in the making

Amer Bisat , Marcel Cassard , Ishac Diwan

For the past 18 months, Lebanon has been reeling from a wrenching economic crisis. This essay deciphers the crisis’s origin, describes the current juncture, and reflects on the likely outcomes in the proximate future.

How did we get here?

With hindsight, Lebanon’s economic crisis was predictable . By the time the crisis erupted in October 2019, the economy was facing four extraordinary challenges. First, public sector debt had reached such elevated levels that a default had become a question of when, not if. Second, the banking sector, having lent three-quarters of deposits to the government, had become functionally bankrupt and increasingly illiquid. Third, the productive economy had experienced virtually no growth for an entire decade — a development with acute socio-political implications. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the country was politically rudderless: there was no president between 2014 and 2016, there were multiple and lengthy delays in cabinet formation, and the 2018 parliamentary elections took place but only after a five-year delay. The Hariri government that was in place when the crisis hit in 2019 became impotent to such an extent that it lacked power to deliver on any of the reforms required as a condition for foreign support.

By October 2019, the citizenry had had enough. Sensing a looming crisis and frustrated by the utter lack of action by the political class, hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets demanding radical political change. The cabinet resigned, throwing the country into a political crisis. Unsurprisingly, capital inflows came to a sudden halt. Banks, already insolvent, experienced a sharp liquidity crunch, forcing them to declare a “bank holiday” and institute severe restrictions on bank withdrawals. A foreign exchange black market emerged and the national currency, the lira, sharply depreciated. In turn, inflation soared and people’s real wages and purchasing power collapsed. In addition, as if all these woes were not sufficient, a severe COVID-19 crisis hit the country and, most tragically, a devastating explosion took place on Aug. 4, leveling a third of downtown Beirut.

The confluence of these large negative shocks led to the implosion of the economy: GDP is estimated to have contracted by 25% in 2020, with an additional 10-15% decline forecast for 2021. When measured in USD, the Lebanese economy may end up shrinking from $60bn in 2018 to $15bn in 2021. An extreme form of wealth destruction is taking place with the Lebanese de facto losing the majority of their bank savings. Meanwhile, four out of every ten Lebanese are out of work, and half the population is under the poverty line.

But what these numbers do not reveal are the structural scars. Human capital is fast eroding due to a massive brain drain of the young and skilled. Equally worrying is the loss of physical productive capacity resulting from widespread business closures. Much more alarming are the security consequences of the economic implosion. Lebanon’s sectarian history is rife with conflict. An economic collapse provides a perfect habitat for a return of violence.

What is being done?

Confronted with these traumatic shocks, the Lebanese political class has been appallingly missing in action. A new government was formed in January 2020 and, to its credit, worked with an international consultant on an emergency economic program and initiated IMF negotiations. The program spelled out the size of the financial losses and called on all stakeholders to share in the burden, starting with creditors and bank shareholders. Unfortunately, the effort quickly proved quixotic. Under concerted attack from a wide-ranging coalition of political and vested interests, the government balked at the required economic and financial measures, which in turn led to a halt in IMF negotiations. In the event, the government became ineffectual and, following the Aug. 4 explosion, tendered its resignation, creating another political vacuum.

What explains the political class’s inaction?

There are three likely explanations. First, an intractable political environment that makes collective decision-making difficult, especially given the size of the losses that need apportioning. Second, Lebanese political parties are “agents and not principals,” effectively acting as messengers of regional and international players who are currently not incentivized to solve the Lebanese crisis. Third, paralysis reflects an active decision by the political class to do nothing: high inflation, exchange rate depreciation, and deposit “lirafication” shift the burden onto the population at large and away from the interests of the oligarchy. Regardless of which of these reasons dominates, policy neglect is creating seismic political shifts that will eventually threaten the survival of the current political class.

Where do we go from here?

Predicting how the crisis evolves from here is difficult, but we can frame the contours of the likely outcomes around three different scenarios.

The worst-case scenario is a continuation of the path of “ malign neglect .” While not our baseline, we see the probability of this scenario playing out as reasonably high. This scenario allows for a continuation of the ongoing but extremely insidious process of “auto-adjustment” of macroeconomic imbalances, albeit in a very sub-optimal and regressive manner, and with a long-term negative impact on growth and the social fabric of the country. Left to its own devices, the economy will generate an alarming acceleration of youth and skilled labor emigration, and enterprise closures. The currency will become further un-anchored, hyperinflation will wipe out incomes and wealth, and food and medical shortages will escalate, requiring rising levels of humanitarian support. The security situation will inevitably deteriorate into, at best, a state of lawlessness and, at worst, organized armed conflict of the kind the country has experienced in the past.

The best-case scenario involves a political consensus around a comprehensive economic program, on which basis a credible and independent government with emergency legislative powers is formed. Such a cabinet would start with a short-term stabilization program involving tightening of liquidity, arresting the fiscal implosion, officializing capital controls, and obtaining an urgent bridge loan under the umbrella of an IMF Stand-By agreement. The cabinet would also commit to a three-year program that would restructure the debt, recapitalize the banking sector, streamline the public sector, and enact “real economy” reforms that would put the country on a recovery path.

At this juncture, we assign to this positive scenario a very low probability of coming to fruition. Indeed, such an ambitious program, albeit essential for the long-term survival of the country, will almost certainly be rejected by an entrenched political class and vested interests, who would see it as political suicide.

The most likely scenario lies somewhere in the middle and involves the formation of a “traditional” (as opposed to independent) government, with the backing of all political parties. A shift in regional dynamics (with the promise of an Iran/U.S. rapprochement) may open a space for domestic compromise. Furthermore, the magnitude of the recent economic collapse may have created enough fear among local players regarding their political survival, that they may be willing to implement some difficult measures.

Under this middle scenario, the government would only have limited room for maneuver and will remain hostage to the political class and associated vested interests. It would not have the political muscle (or willingness) to put in place the structural transformation required by the country and would be unlikely to adhere (on an ongoing basis) to the conditions of an IMF program . With elections planned in 2022, political parties would block measures required to put the economy on a sustainable path, including reducing subsidies, restructuring the banking sector with an even distribution of the massive losses across the various segments of the economy and population, and cutting government spending and raising taxes. As such, although this middle-of-the-road scenario may stabilize the situation in the short run (and may even mobilize some limited foreign funding), it has little chance of allowing the country to genuinely turn the corner.

Lebanon is facing an existential moment. Over the short term, the best one can hope for is a “muddle through” scenario (with limited foreign financial support) that arrests the economic collapse. In the medium term, the 2022 parliamentary elections, if they are held on time, and the hoped-for resolution of regional crises may open up a window for the emergence of a new leadership that can finally put the country on the trajectory of prosperity it so deserves.

Amer Bisat is Head of Sovereign and Emerging Markets (alpha) at BlackRock and a former IMF economist. Marcel Cassard was the global head of Fixed Income and Economics Research at Deutsche Bank and a former IMF economist. He is a member of LIFE's Advocacy Committee. Ishac Diwan is professor of economics at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris and a former Director at the World Bank. The views expressed in this piece are their own.

Photo by JOSEPH EID/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click her e .

Programs submenu

Regions submenu, topics submenu, strengthening australia-u.s. defence industrial cooperation: keynote panel, cancelled: strategic landpower dialogue: a conversation with general christopher cavoli, china’s tech sector: economic champions, regulatory targets.

- Abshire-Inamori Leadership Academy

- Aerospace Security Project

- Africa Program

- Americas Program

- Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy

- Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

- Asia Program

- Australia Chair

- Brzezinski Chair in Global Security and Geostrategy

- Brzezinski Institute on Geostrategy

- Chair in U.S.-India Policy Studies

- China Power Project

- Chinese Business and Economics

- Defending Democratic Institutions

- Defense-Industrial Initiatives Group

- Defense 360

- Defense Budget Analysis

- Diversity and Leadership in International Affairs Project

- Economics Program

- Emeritus Chair in Strategy

- Energy Security and Climate Change Program

- Europe, Russia, and Eurasia Program

- Freeman Chair in China Studies

- Futures Lab

- Geoeconomic Council of Advisers

- Global Food and Water Security Program

- Global Health Policy Center

- Hess Center for New Frontiers

- Human Rights Initiative

- Humanitarian Agenda

- Intelligence, National Security, and Technology Program

- International Security Program

- Japan Chair

- Kissinger Chair

- Korea Chair

- Langone Chair in American Leadership

- Middle East Program

- Missile Defense Project

- Project on Fragility and Mobility

- Project on Nuclear Issues

- Project on Prosperity and Development

- Project on Trade and Technology

- Renewing American Innovation Project

- Scholl Chair in International Business

- Smart Women, Smart Power

- Southeast Asia Program

- Stephenson Ocean Security Project

- Strategic Technologies Program

- Transnational Threats Project

- Wadhwani Center for AI and Advanced Technologies

- All Regions

- Australia, New Zealand & Pacific

- Middle East

- Russia and Eurasia

- American Innovation

- Civic Education

- Climate Change

- Cybersecurity

- Defense Budget and Acquisition

- Defense and Security

- Energy and Sustainability

- Food Security

- Gender and International Security

- Geopolitics

- Global Health

- Human Rights

- Humanitarian Assistance

- Intelligence

- International Development

- Maritime Issues and Oceans

- Missile Defense

- Nuclear Issues

- Transnational Threats

- Water Security

An Economic Crisis in Pakistan Again: What’s Different This Time?

Photo: AAMIR QURESHI/AFP/Getty Images

Critical Questions by Daniel F. Runde and Ambassador Richard Olson

Published October 31, 2018

Pakistan’s newly-elected government is already dealing with a balance of payments crisis, which has been a consistent theme for the nation’s newly elected officials. Pakistan’s structural problems are homegrown, but what is different this time around is an added component of Chinese debt. Pakistan is the largest Belt and Road (BRI) partner adding another creditor to its already complicated economic situation.

Pakistan’s system is ill-equipped to make changes which would avoid future excessive debt. A bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is probably the safest bet for the country although it is unclear whether the United States will support the program. How Pakistan decides to handle its debt crisis could provide insight into how the U.S., IMF, and China will resolve development issues in the future. Beijing is a relatively new player in the development finance world so much is to be learned from how it deals with Pakistan and how it could possibly maneuver in other developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Q1: What is Pakistan’s current financial and economic situation?

A1: Pakistan held its most recent elections in July 2018. The Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party gained over 100 seats in the parliament, and its founder Imran Khan , a famous cricket team captain, was installed as prime minister. Prime Minister Khan has inherited a balance of payments crisis , the third one in the last 10 years. By the end of June 2018, Pakistan had a current account deficit of $18 billion , nearly a 45 percent increase from an account deficit of $12.4 billion in 2017. Exorbitant imports (including those related to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC)) and less-than-projected inflows (export revenues and remittances) have led to a current account deficit widening, with foreign currency reserves levels covering less than two months of imports—pushing Pakistan towards a difficult economic situation .

Part of Pakistan’s financial crisis stems from the fact that 2018 was a poor year for emerging markets. Global monetary tightening, increased oil prices, and reduced investor confidence have negatively impacted the country’s already precarious economic situation. But the country’s deep structural problems and weak macroeconomic policies have further exposed the economy to an array of debt vulnerabilities.

Pakistan has had an overvalued exchange rate, low interest rates, and subdued inflation over the last few years. This loose monetary policy has led to high domestic demand, with two-thirds of Pakistan’s economic growth stemming from domestic consumption. An overvalued exchange rate has led to a very high level of imports and low level of exports. Pakistan’s high fiscal deficit was accelerated even further in 2017 and 2018 because elections have historically caused spending to rise (both of the most recent fiscal crises followed elections). Perhaps the greatest financial issues facing Pakistan are its pervasive tax evasion and chronically low level of domestic resource mobilization. Taxes in Pakistan comprise less than 10 percent of GDP , a far cry from the 35 percent of countries that are part of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Pakistan also suffers from impediments in the energy sector through frequent and widespread power outages that hurt its competitiveness.

In Western media, Chinese investment is often cited as the main driver of Pakistan’s debt crisis. This is somewhat true as China’s BRI makes Pakistan a key partner through the shared CPEC. The CPEC is a $60 billion program of infrastructure, energy and communication projects that aims to improve connectivity in the region. CPEC infrastructure costs have certainly placed a greater debt burden on Pakistan, but the current structural problems are homegrown; the root cause of the energy shortages is now less a matter of power generation, and more of fiscal mismanagement of the power sector .

Q2: What are Pakistan’s options?

A2: Pakistan appears to be in perpetual crisis-mode, and for too long the Pakistani government has been overly reliant on U.S. bilateral assistance. While it may not be the first choice of the Pakistani government, an IMF bailout is the most likely outcome of this financial crisis because it is probably the only path for Pakistan to regain its macroeconomic stability. Any “bailout” from a bilateral donor (meaning China or Pakistan’s Gulf State friends, including Saudi Arabia which has recently provided Pakistan $3 billion for a period of one year as balance-of-payment support) will not get at the root issues that Pakistan faces—its loose macroeconomic, fiscal, and monetary policies. Pakistan needs to get its house in order and remedy many of its domestic economic issues. 18 out of Pakistan’s 21 IMF programs over the last 60 years have not been completed despite obtaining over $30 billion in financial support across those programs. Just like today’s current financial crisis, Pakistan’s last two IMF packages (in 2008 and 2013) were also negotiated by incoming governments.

Q3: Would the U.S. support a new IMF Pakistan program?

A3: The current U.S. administration and Congress would not be supportive of additional bilateral funding to Pakistan—meaning money coming directly from the United States. Since 2001, Pakistan has been the beneficiary of the U.S. Coalition Support Fund (CSF), which reimburses allies for costs incurred by war on terrorism. The CSF is used to reimburse Pakistan for U.S. military use of its network infrastructure (e.g., ports, railways, roads, airspace) so that the United States can prosecute the war in neighboring Afghanistan, as well as certain Pakistani military counter-terrorism operations. The CSF for Pakistan has been as high as $1.2 billion per year, and, in recent years, $900 million per year. With nearly $1 billion in CSF distributed every year, along with $335 million in humanitarian assistance, it will be difficult to convince Congress to appropriate more funds for a Pakistan bailout yet. However, due to inaction on the part of Pakistan to expel or arrest Taliban insurgents operating from Pakistani territory, the United States has recently cut another $300 million from the CSF, bringing the total to $850 million in U.S. assistance withheld from Pakistan this year. In fact, all security assistance to Pakistan, whether it is international military education and training, foreign military financing, or the CSF, has been suspended for this year according to one State Department official.

An IMF program for Pakistan faces resistance from some members of Congress. A group of 16 senators has already signed a letter to President Trump that outlines their opposition to bailing out Pakistan because the IMF package would, in effect, be bailing out Chinese banks.

The Trump administration has also taken a hardline stance towards assisting Pakistan with its financial crisis. Secretary of State Pompeo stated this past July that he would not support an IMF bailout that went towards paying off Chinese loans. In September, Secretary Pompeo visited Pakistan, and there were indications that the United States would not block an IMF program. If an IMF program is enacted, there is no doubt that it would have stronger conditionality and a greater insistence on full transparency of Pakistan’s debt obligations.

Q4: Would an IMF package be a bailout of the Chinese?

A4: The terms of Pakistan’s loans with China are currently unclear and multiple news outlets have reported that Pakistan has refused to share CPEC information with the IMF. However, it is not unreasonable to presume that the terms in those contracts would be more demanding than terms typically asked by the IMF. Unless the terms between Pakistan and China and its state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are disclosed and made clear to the IMF, then it is unwise for the IMF to proceed with a bailout package.

The IMF’s focus is not in projecting power and influence; rather it seeks to help struggling nations get back on their feet. The same cannot be said for China. China appears to be most interested in spreading its influence and gaining valuable assets for its military and expanding economy, while at the same time exporting its surplus capacity for infrastructure building. In its annual report to Congress, the Department of Defense reiterated this concern, “countries participating in BRI [such as Pakistan] could develop economic dependence on Chinese capital, which China could leverage to achieve its interests.”

Of Pakistan’s nearly $30 billion trade deficit, 30 percent is directly attributable to China . If China were concerned about the economic crisis in Pakistan, it would make immediate concessions which Pakistan Finance Minister Asad Umar says China is working on . To help with the crisis, China could readjust its trade surplus with Pakistan in different ways. For example, China could buy Pakistani cement and other purchases in the short term to illustrate that they are aware of and swiftly responding to the economic turmoil in Pakistan. Other nations have struggled with debt obligations to China. For instance, in July 2017, Sri Lanka signed over a 99-year lease for Hambantota Port to a Chinese SOE because of Sri Lanka’s inability to pay for BRI costs. Malaysia took a different path and decided to cancel major infrastructure projects with China in August 2018 due to worries that they would increase its debt burden .

Q5: What are the consequences if there is no IMF package?

A5: It is likely that China will provide even more assistance to broaden Pakistan’s dependency. Chinese banks and SOEs have already invested heavily into Pakistan, so much so that state bank loans have not been fully disclosed to the global community. In fact, Pakistan’s Status Report for July 2017 through June 2018 shows that Chinese commercial banks hold 53 percent of Pakistan’s outstanding commercial debt. However, that percentage may be even higher than the report depicts. While China and Pakistan have agreed to make all CPEC projects readily available to the public, the information is scattered and often left blank on essential financial reports (see July-June 2017 document ), and so it is difficult to obtain a full sense of the degree of Pakistan’s indebtedness to China. Again, much of the loan information provided by the Pakistani government, especially concerning China, is not entirely transparent.

If China chooses to follow through and become the “point person” for an assistance package, the pressure will be taken off the IMF. But, if the United States does not support an IMF package, it will forego major geopolitical potential in the region to its main competitor, China.

Pakistan represents a litmus test of all future cases in which the IMF, United States, China, and any emerging market country are all involved. Depending on how Beijing chooses to navigate Pakistan’s financial crisis, China may soon find itself responsible for rectifying the debt burdens of Zambia and many other BRI countries.

Q6: What are U.S. geopolitical “equities” in Pakistan?

A6: The United States is invested in Pakistan because of its significant geopolitical importance.

- Pakistan is an important component of the balance of power in South Asia. Both India and Pakistan have nuclear weapons capabilities. Moreover, China, India, and Pakistan have been in dispute over the Kashmir region since 1947. Regional stability is in the interest of the United States.

- Despite its ambiguous stance on militant groups, Pakistan is ostensibly an ally of the United States because of its proximity to Afghanistan. Since the War on Terror began in 2001, Pakistan has been an active partner in the elimination of core al Qaeda within Pakistan and has facilitated aspects of the U.S. military campaign in Afghanistan.

- The United States now seeks a negotiated settlement to the conflict in Afghanistan. To accomplish this, perhaps the United States will come to Pakistan with a simple offer: “deliver the Taliban, and we will give you the IMF.”

- Whereas previous administrations may have tried to “play nice” with Pakistan, under the Trump administration, there is a chance that the U.S. government will push the IMF to adopt stricter terms for a Pakistan bailout, citing the Pakistani government’s failures of the last two programs.

- Other than strategic military importance, one of the most important national security challenges to the United States is Pakistan’s demographic trends. Currently, over 64 percent of Pakistanis are under the age of 30—the largest percentage of youth in the country’s history. Over the next 30 years, Pakistan’s population will increase by over 100 million, jumping from 190 million to 300 million by 2050 . The spike in youth population presents an opportunity for the U.S. government and private sector to increase investment in Pakistan. Pakistan’s economy must generate 1 million jobs annually for the next three decades and GDP growth rates must equal 7 percent or more per year to keep up with the population boom. Were Pakistan’s economy to collapse, the world would see the first instance of a failed state with a substantial arsenal of nuclear weapons.

- An economically healthy Pakistan could be a large market for U.S. goods and services. If the U.S.-Pakistan relationship is strained as a result of this financial crisis, it will not only harm the United States militarily but will also harm U.S. businesses and Pakistani consumers.

Q7: Should the U.S. support an IMF package to Pakistan?

A7: Given the geostrategic importance of Pakistan for the United States, we should support a package but with stronger conditionality than in 2013 along with full transparency and disclosure of its debt obligations.

Daniel F. Runde is senior vice president, director of the Project on Prosperity and Development, and holds the William A. Schreyer Chair in Global Analysis at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. Richard Olson is a non-resident senior associate at CSIS. He is the former U.S. ambassador to the United Arab Emirates and Pakistan; most recently he served as the U.S. special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan during the Obama administration. Special thanks to CSIS Project on Prosperity and Development program coordinator Owen Murphy and intern Austin Lucas for their contributions to this analysis.

Critical Questions is produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(s).

© 2018 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. All rights reserved.

Daniel F. Runde

Ambassador richard olson, programs & projects.

- Project on U.S. Leadership in Development

Home / Essay Samples / Economics / Economic Crisis / Understanding the Dynamics of an Economic Crisis

Understanding the Dynamics of an Economic Crisis

- Category: Economics

- Topic: Economic Crisis , Economic Problem

Pages: 1 (307 words)

- Downloads: -->

Causes of Economic Crises

- Financial Speculation: Speculative bubbles in asset prices, such as real estate or stock markets, can lead to sudden crashes and trigger an economic crisis.

- Excessive Debt: High levels of public or private debt can strain the financial system and lead to a debt crisis.

- External Shocks: Global events, such as commodity price fluctuations or international financial crises, can impact a country's economy.

- Policy Failures: Mismanagement of fiscal and monetary policies can exacerbate economic imbalances and contribute to a crisis.

- Political Instability: Political uncertainties and conflicts can disrupt economic activities and investor confidence.

Signs and Impact of Economic Crises

--> ⚠️ Remember: This essay was written and uploaded by an--> click here.

Found a great essay sample but want a unique one?

are ready to help you with your essay

You won’t be charged yet!

Consumerism Essays

Economic Inequality Essays

Capitalism Essays

Brexit Essays

Nafta Essays

Related Essays

We are glad that you like it, but you cannot copy from our website. Just insert your email and this sample will be sent to you.

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Your essay sample has been sent.

In fact, there is a way to get an original essay! Turn to our writers and order a plagiarism-free paper.

samplius.com uses cookies to offer you the best service possible.By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .--> -->