Alternative Courses of Action in Case Study: Examples and How To Write

The ultimate goal of creating a case study is to develop a feasible action that can solve the problem it raised.

One way to achieve this is by enumerating all the possible solutions for your case study’s subject. The portion of the case study where you perform this is called ACA or Alternative Courses of Action.

Are you struggling with writing your case study’s ACA? Do not worry; we have provided you with the most detailed guide on writing the Alternative Courses of Action (ACA) of a case study.

Table of Contents

What are alternative courses of action (aca) in a case study.

Alternative Courses of Action (ACA) are the possible actions a firm or organization can implement to address the problem indicated in the case study. These are suggested actions that a firm can consider to arrive at the most feasible and effective solution to the problem.

This portion doesn’t provide the actual and optimal solution yet. Instead, it contains proposed alternatives that will still undergo an evaluation of their respective advantages and disadvantages to help you come up with the best solution.

The ACA you will offer and indicate will be based on your case study’s SWOT analysis in the “ Areas of Consideration ” portion. Thus, a SWOT analysis is performed first before writing the ACA.

What Is the Importance of Alternative Courses of Action (ACA) in a Case Study?

Given the financial, logistical, and operational limitations, developing solutions that the firm can perform can be challenging. By enumerating and evaluating the ACA of your case study, you can filter out the alternatives that can be a potential solution to the problem, given the business’s constraints 1 . This makes your proposed solutions feasible and more meaningful.

How To Write Alternative Courses of Action in Case Study

Here are the steps on how to write the Alternative Courses of Action for your case study:

1. Analyze the Results of Your SWOT Analysis

Using the SWOT analysis, consider how the firm can use its strengths and opportunities to address its weaknesses, mitigate threats, and eventually solve the case study’s problem.

Suppose that the case study’s problem is declining monthly sales, and the SWOT analysis showed the following:

- Strength : Creative marketing team

- Opportunity : Increasing trend of using social media to promote products

Then, you may include an ACA about developing the digital marketing arm of the firm to attract more customers and boost monthly sales. This can also address one of the possible threats the firm faces, which is increasing direct marketing costs.

2. Write Your Proposed Solutions/Alternative Courses of Action (ACA) for Your Case Study’s Problem

Once you have reviewed your SWOT analysis and come up with possible solutions, it’s time to write them formally in your manuscript. Each solution does not have to be too detailed and wordy. State the specific action that the firm must perform concisely.

Going back to our previous example in Step 1, here is one of the possible ACA that can be included:

ACA #1: Utilize digital platforms such as web pages and social media sites as an alternative marketing platform to reach a wider potential customer base. Digital marketing, together with the traditional direct marketing strategy currently employed, maximizes the business’ market presence, attracting more customers, and potentially driving revenues upward.

In our example above, there is a clear statement of the firm’s action: to use web pages and social media sites to reach more potential customers and increase market presence. Notice how the ACA above provides only an overview of “what to do” and not a complete elaboration on “how to do it.”

3. Identify the Advantages and Disadvantages of Each ACA You Have Proposed

After specifying the ACA, you must evaluate them by stating their respective advantages (pros) and disadvantages (cons). In other words, you must state how your ACA favors the firm (advantages) and its downsides and limitations (disadvantages).

Again, your evaluation does not have to be too detailed but make sure that it is relevant to the ACA that it pertains to.

Let’s return to the ACA we developed from step 2, utilizing digital platforms (e.g., social media sites) to reach more potential customers. What do you think will be the pros and cons of this ACA?

Let’s start with its potential benefits (advantages). Using digital platforms is cheaper than using print ads or direct marketing. So, this will save some funds for the firm. In short, it is cost-effective.

Second, digital platforms offer analytical tools to measure your ads’ reach, making it easier to evaluate people’s perceptions of your offering.

Third, using social media sites makes communicating with any potential customer easier. You can quickly respond to their queries, especially if they are interested in your product.

Lastly, you can reach as many types of people as possible by taking advantage of the internet algorithm.

Now, let us consider its disadvantages 2 . First, using digital marketing takes time and effort to learn, and you must be able to adapt quickly to the changes in trends and new strategies to keep up with the competition.

Second, you must deal with the increasing market competition, as many businesses already use digital platforms.

Third, you have to deal with negative feedback from your customers that are visible to the public and may affect their perception of your brand.

After pondering over the pros and cons of your ACA, it’s time to write them concisely in your manuscript. You can present it in two ways: by tabulating it or by simply listing them.

Example in Table Form:

Examples of Alternative Courses of Action (ACA) in a Case Study

Case Study Problem: Xenon Pastries faces a problem handling larger orders as Christmas Day approaches. With an estimated 15% increase in customer demand, this is the most significant increase in their daily orders since 2012. The management aims to maximize profit opportunities given the rise in customer demand.

ACA #1: Hire part-time workers to increase staff numbers and meet the overwhelming seasonal increase in customer orders. Currently, Xenon Pastries has a total of 9 workers who are responsible for the accommodation of orders, preparation, and delivery of products, and addressing customers’ inquiries and complaints. Hiring 2 – 3 part-time workers can increase productivity and meet the daily order volume.

- Do not require too much effort to implement since hiring announcements only require signages or social media postings

- High certainty of finding potential workers due to the high unemployment rate

- Improve overall productivity of the business and the well-being of other workers since their workload will be lessened

Disadvantages

- Increase in operating expense in the form of wages to the new workers

- Managing more employees and monitoring their performance can be challenging

- New workers might find it challenging to adapt essential skills required in the operation of the business

ACA #2: Increase the prices of Xenon pastries’ products to increase revenues . This option can maximize Xenon Pastries’ profit even if not all customers’ orders are accommodated.

- Cost-effective

- Easy to implement since it only requires changing the price tags of the products

- If customers’ desire to buy the products does not change, the price increase will certainly increase the business’ revenue

- Some customers might be discouraged from buying because of an increase in prices

- There’s a possibility that the increase in the price of the products will make it more expensive relative to competitors’ products

Case Study Problem: Delta Motors has been manufacturing motorcycles for ten years. Recently, the business suffered a gradual shrink in its quarterly revenues due to the increasing popularity of traditional and newly-developed electric bikes. Delta Motors seeks a long-term strategy to attract potential customers to bounce back sales.

ACA #1: Develop a “regular installment payment” scheme to attract customers who wish to purchase motorcycles but have insufficient lump-sum money to acquire one. This payment scheme allows customers to pay an initial deposit and the remaining amount through smaller monthly payments.

- Enticing for middle to low-income individuals who comprise a large chunk of the population

- Requires low initial capital to implement

- Provides a new source of monthly income streams that can benefit the financial standing of the company

- Risk of default or delays in installment payments

- Requires additional human resources to manage and collect installment payments

- The payment scheme requires time to gain returns due to the periodic flow of funds

- Requires a careful creation of guidelines and terms and conditions to ensure smooth facilitation of the installment payment scheme

ACA #2: Introduce new motorcycle models that can entice different types of customers. These models will feature popular designs and more efficient engines.

- This may capture the public’s interest in Delta Motors, which can lead to an increase in the number of potential customers and earning opportunities

- Enables the business to keep up with the intense market competition by providing something “fresh” to the public

- Provides more alternatives for those who already support Delta Motors, strengthening their loyalty to the brand

- Conceptualization of a new model takes a lot of brainstorming to test its feasibility and effectiveness

- Requires sufficient funds to sustain the investment for the development of a new model

- It requires effective marketing strategies to promote the new model to the public

Tips and Warnings

- Do not include in this portion your case study’s conclusion . Think of ACA as a list of possible ways to address the problem. In other words, you suggest the possible alternatives to be selected here. The “ Recommendation ” portion of your case study is where you pick the most appropriate way to solve the problem.

- Use statistical data to support the advantages and disadvantages of each ACA. Although this is optional, presenting numerical data makes your analysis more concrete and factual than just stating them descriptively.

- Do not fall into the “meat sandwich” trap. This happens when you intently make some of the alternatives less desirable so that your preferred choice stands out. This can be done by refusing to elaborate on their benefits or excessively concentrating on their disadvantages. Make sure that each ACA has potential and can be implemented realistically.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. how many alternative courses of action (aca) can a case study have.

Sometimes your instructor or teacher will tell you the required number of ACA that must be included in your case study . However, there’s no “standard” limit to how many ACA you can indicate.

2. What is the difference between Alternative Courses of Action (ACA) and Recommendations?

As mentioned earlier, the case study’s ACA aims to enumerate all possible solutions to the problem. It is not the stage where you state the “final” action you deem most appropriate to address the issue. The case study portion where you explicitly mention your “best” alternative is called the “Recommendation.”

To help you understand the point above, let’s return to our Delta Motors example. In our previous section, we have provided two ACA that can solve the problem, namely (1) developing a regular installment payment plan and (2) introducing a new motorcycle model.

Suppose that upon careful analysis and evaluation of these ACA, you came up with ACA #2 as the more fitting solution to the problem. When you write your case study’s recommendation, you must indicate the ACA you chose and your reasons for selecting it.

Here’s an example of the Recommendation of the case study:

Recommendation

Introducing new motorcycle models that feature popular designs and more efficient engines to entice different types of customers is the most promising alternative course of action that Delta Motors can implement to bounce back its quarterly revenues and keep up with the competitive market. This creates a strong impression on the public of the company’s dedication to promoting high-quality motorcycles that can withstand changes in consumer preferences and market trends. Furthermore, this action proves that the company is continuously evolving to offer a variety of alternative models to suit everyone’s tastes. With proper promotion, these models can rekindle the company’s popularity in the automotive and motorcycle industry.

- How to Analyze a Case Study. Retrieved 23 May 2022, from https://wps.prenhall.com/bp_laudon_essbus_7/48/12303/3149605.cw/content/index.html

- Develop a Digital Marketing Plan. Retrieved 23 May 2022, from https://www.nibusinessinfo.co.uk/content/advantages-and-disadvantages-digital-marketing

Written by Jewel Kyle Fabula

in Career and Education , Juander How

Last Updated July 8, 2023 08:29 PM

Jewel Kyle Fabula

Jewel Kyle Fabula is a Bachelor of Science in Economics student at the University of the Philippines Diliman. His passion for learning mathematics developed as he competed in some mathematics competitions during his Junior High School years. He loves cats, playing video games, and listening to music.

Browse all articles written by Jewel Kyle Fabula

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net

404 Not found

404 Not found

Business Case Analysis Format and Guidelines for Students

This Case Analysis Guideline will help you to have an idea of how to analyze a Business case properly. It will also give you pointers on how to construct and what to include in the different parts of your Case Analysis from the Point of View, Problem Statement, down to the decision-making, and Plan of Action.

May this post be of help to all of you, so you can come up with a better analysis of your group’s homework such as thesis or projects?

I. Point of View

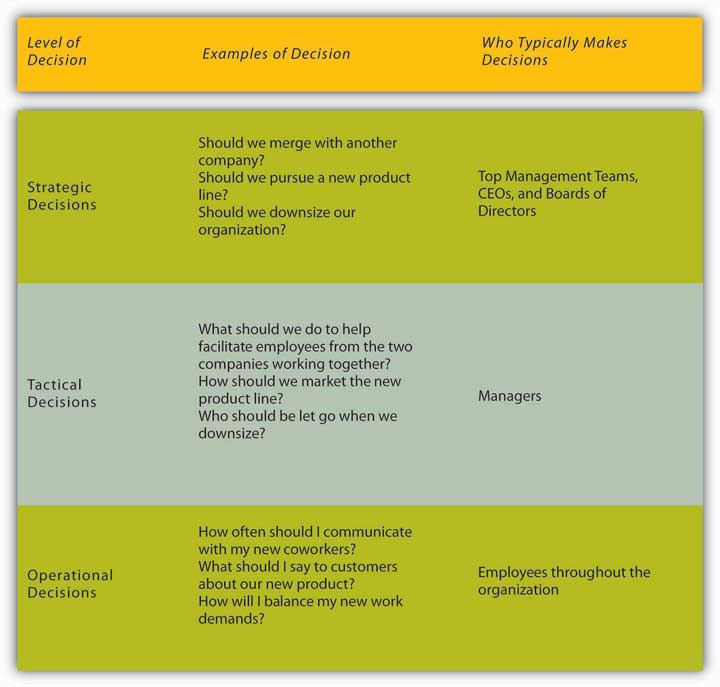

The Point of View refers to the perspective of the decision-maker or person who is in the position to make the final recommendations as mentioned in the case.

For example, the problem is related to the manufacturing division. It can be about Engineering, manufacturing processes, quality assurance, and warehousing. The possible decision-maker or point of view is the Vice President of the Manufacturing division.

If the concern or problem is related to product quality which is under a Quality Department within the manufacturing division, then it is possible to put the ‘Manager of Quality Department’ at the Point of View.

II. Time Context

The Time Context is the time in the case when you will start your analysis. It can be an imaginary time or the last-mentioned date in the case. Make sure that you can justify the reason behind your given time context. Because if your stated time is not relevant, it is possible that your analysis is also not relevant.

Assuming that the problem arises during the summer / dry season in the Philippines. You cannot put June to November in the time context as it is usually the rainy/wet season in PH.

If the problem arises in 2021, you can use that year in time context. For example, ‘First Quarter of 2021’ or ‘February 2021.’

III. Statement of the Problem

The Statement of the Problem defines the perceived problem in the case which becomes the subject of the analysis. You can present this in declarative or in question format.

For example: How to expand the business of Company A while in the middle of the current situation of the food industry.

IV. Statement of the Objectives

The Statement of the Objectives are goals that the case analysis hopes to achieve. It should basically satisfy the test of SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic, and Time-bound)

For example: To improve the company’s performance in terms of product quality in 12 months. Or to increase the company’s sales for its dog food product lines in 6 months.

IV. Areas of Consideration

For the areas of consideration in your case study, you have to state the internal and external environment of the company/firm through SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) Analysis.

You can indicate in the internal environment the facts relating to the company’s financial situation, manufacturing, marketing, and human resources.

For example, does the business have a high employee turnover rate? Does the business’ revenue continuously increase year after year? How about product quality, can it keep up with the industry competition? You should focus on the factors that can help solve the issues and problems that the business is facing .

For the external environment, indicate the economic situation of the city or country. If the government policy affects your business then you can also state it. Indicate here also your competition which company it is or which product. If your chosen company sells dog food or mobile phone, state your competitor.

Now that you have the list of the internal and external environments. You should now list your company’s Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats.

Under ‘Strengths,’ of course, depending on what is stated in the case. You can indicate if the company is prominent in the industry, awards such as ‘Best Manpower Agency for 10 years,’ ‘Best Hotel in terms of service.’

For ‘Weakness,’ include if the company has a high manpower turnover ratio, lowest quality in the market, and low budget for marketing/advertisement.

Under Opportunities, indicate if the country the company is located in a ‘Free Trade Zone,’ rising population which can equate to increasing product consumption. For example, increasing toothpaste consumption. The Philippine Government has a build build build program which means they will need an increase in cement usage.

VI. Assumptions

The Assumptions are the factors that are not clear or not specifically stated in the case. You need to clarify these factors and state them as assumptions to limit the analysis.

In layman’s terms, you will list in the Assumptions the boundaries of your analysis. It will also help the panelist to understand the reason behind the items you list in your case analysis.

VII. Alternative Courses of Action (ACA)

The Alternative Courses of Actions (ACAs) are the possible solutions to the identified problem. Each of the ACA must stand alone and must be able to solve the stated problem and achieve the objectives. The ACA must be mutually exclusive. In this regard, the student must choose an ACA to the exclusion of the others.

Also, you have to analyze each ACA in the light of the SWOT analysis and assumptions that is if there are any. You have to state clearly the advantages and disadvantages of each ACA. If the case contains enough information or data. Your stated advantages and disadvantages should be supported quantitatively to minimize bias.

VIII. Analysis of ACAs

The analysis of ACAs will state the list of advantages and disadvantages of each alternative course of action.

I have here examples of the courses of action. Again, these ACAs should be mutually exclusive and should solve the issues of the company. If the ACAs are somewhat related to each other, it is best to combine them and then think of a new one that is totally independent.

ACA 1. Increasing the Salary of the Employees

- Advantages of this course of action

- Disadvantages of this course of action

ACA 2. Reduce the Price of the Products Sold

ACA 3. Buyout the Competition

- Disadvantages

IX. Conclusion/Recommendation

After the analysis of the different Alternative Courses of Action (ACAs), you can now come up with the conclusion, recommendations, and decisions. You do not need to repeat the analysis which you have done in the ACA section of the analysis.

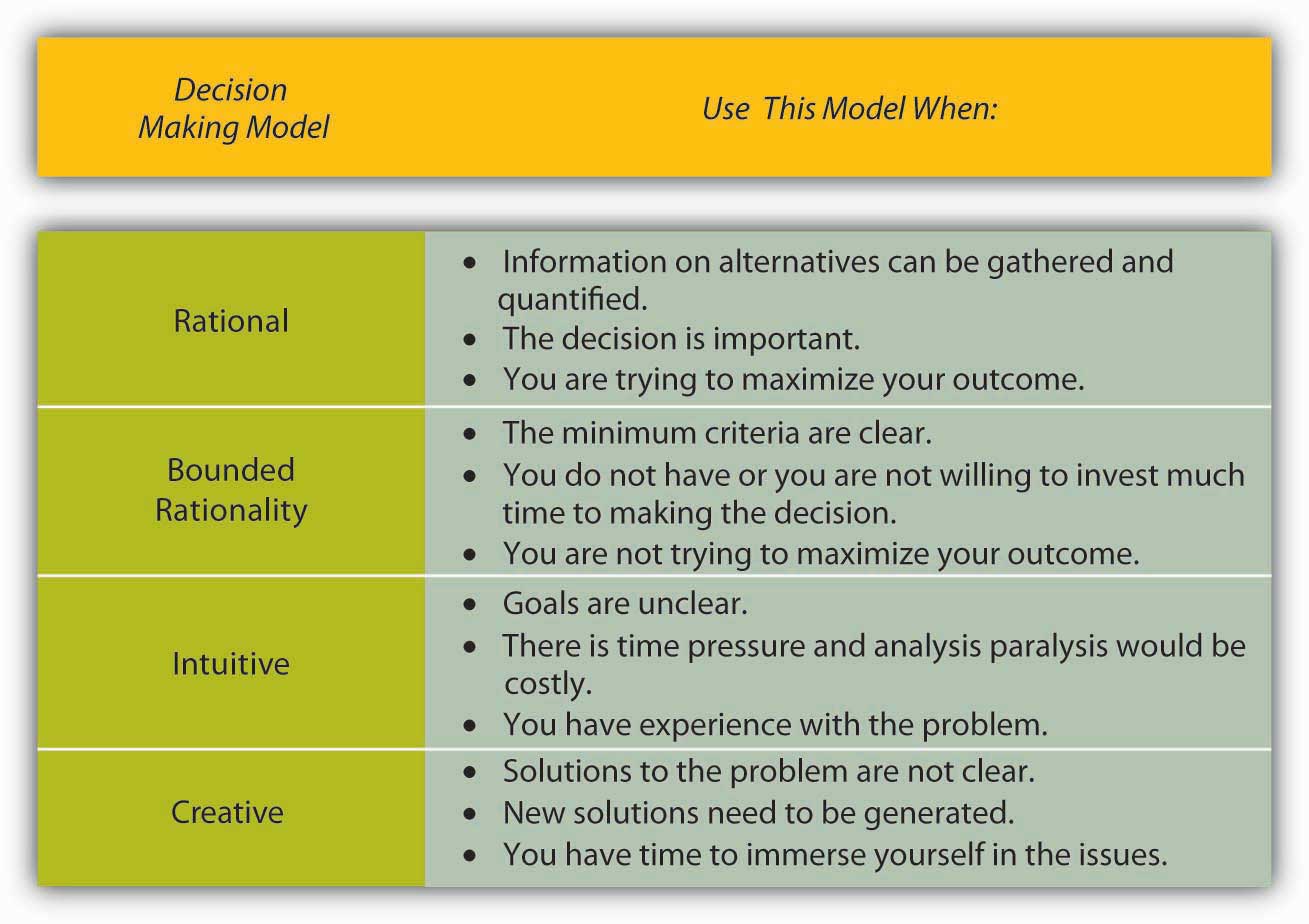

To make this part clearer, it is best to come up with a decision matrix similar to the photo.

Decision Matrix Sample

- 1 – Least Favorable

- 2 – Favorable

- 3 – Most Favorable

Here are the examples of criteria that you can use in the decision matrix.

- Ease of Implementation – refers to the effort required to implement the ACA, the least number of people involved or lesser process in implementing the ACA is the highest score

- Time Frame – This is the time required to implement the ACA, the highest score means the least amount of time needed

- Cost-Efficient – This is the amount of capital requirement, the highest score means the least amount of capital needed to implement the task

Recommendation:

Based on the decision matrix, ‘ACA 3 which is Buying out the competition is the best course of action to solve the problem.

X. Plan of Action

The Plan of Action outlines the series of actions to be undertaken to implement the adopted ACA. The plan of action should reflect, the list of activities, the person in charge, the time frame, and the budget to implement the ACA.

To ensure that you have done the analysis comprehensively, it would be best to program the plan according to the basic functional areas. You should present the plan by having column headings for activity, person/unit responsible/ time frame, and budget.

*There you have it guys! May this business case analysis format and guidelines will be able to help students like you in coming up with a logical solution to business-related cases that your teacher gave your group. Good luck!!!

Related posts:

Useful Guides for Filipinos

How to Find Jobs Abroad for Filipinos

POEA (DMW) Job Fair Schedule 2024

Top No Placement Fee Recruitment Agencies for Jobs Abroad

List of No Placement Fee Countries for Filipino Job Seekers

Best Countries that have Job Opportunities for OFW

How to Check if a Recrruitment Agency is Legit in DMW Website?

How to Find Jobs in the Philippine Government

Here are the List of TESDA Courses

How to Renew PRC License in 3 Ways

- Privacy Policy

- Government Services

- Travel Essentials

- Educational

MattsCradle.com is from the Philippines | Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved.

Do Your Students Know How to Analyze a Case—Really?

Explore more.

- Case Teaching

- Student Engagement

J ust as actors, athletes, and musicians spend thousands of hours practicing their craft, business students benefit from practicing their critical-thinking and decision-making skills. Students, however, often have limited exposure to real-world problem-solving scenarios; they need more opportunities to practice tackling tough business problems and deciding on—and executing—the best solutions.

To ensure students have ample opportunity to develop these critical-thinking and decision-making skills, we believe business faculty should shift from teaching mostly principles and ideas to mostly applications and practices. And in doing so, they should emphasize the case method, which simulates real-world management challenges and opportunities for students.

To help educators facilitate this shift and help students get the most out of case-based learning, we have developed a framework for analyzing cases. We call it PACADI (Problem, Alternatives, Criteria, Analysis, Decision, Implementation); it can improve learning outcomes by helping students better solve and analyze business problems, make decisions, and develop and implement strategy. Here, we’ll explain why we developed this framework, how it works, and what makes it an effective learning tool.

The Case for Cases: Helping Students Think Critically

Business students must develop critical-thinking and analytical skills, which are essential to their ability to make good decisions in functional areas such as marketing, finance, operations, and information technology, as well as to understand the relationships among these functions. For example, the decisions a marketing manager must make include strategic planning (segments, products, and channels); execution (digital messaging, media, branding, budgets, and pricing); and operations (integrated communications and technologies), as well as how to implement decisions across functional areas.

Faculty can use many types of cases to help students develop these skills. These include the prototypical “paper cases”; live cases , which feature guest lecturers such as entrepreneurs or corporate leaders and on-site visits; and multimedia cases , which immerse students into real situations. Most cases feature an explicit or implicit decision that a protagonist—whether it is an individual, a group, or an organization—must make.

For students new to learning by the case method—and even for those with case experience—some common issues can emerge; these issues can sometimes be a barrier for educators looking to ensure the best possible outcomes in their case classrooms. Unsure of how to dig into case analysis on their own, students may turn to the internet or rely on former students for “answers” to assigned cases. Or, when assigned to provide answers to assignment questions in teams, students might take a divide-and-conquer approach but not take the time to regroup and provide answers that are consistent with one other.

To help address these issues, which we commonly experienced in our classes, we wanted to provide our students with a more structured approach for how they analyze cases—and to really think about making decisions from the protagonists’ point of view. We developed the PACADI framework to address this need.

PACADI: A Six-Step Decision-Making Approach

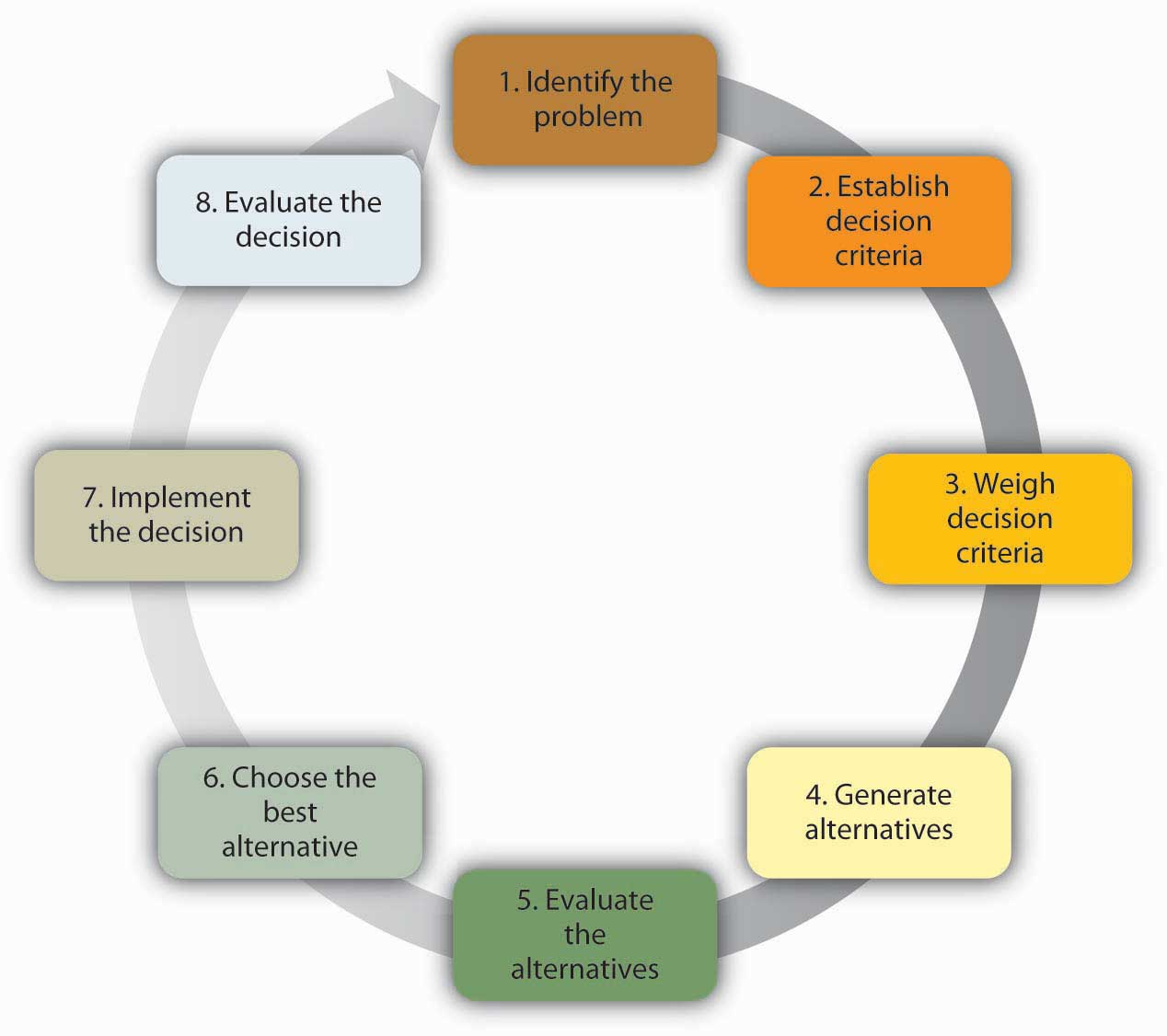

The PACADI framework is a six-step decision-making approach that can be used in lieu of traditional end-of-case questions. It offers a structured, integrated, and iterative process that requires students to analyze case information, apply business concepts to derive valuable insights, and develop recommendations based on these insights.

Prior to beginning a PACADI assessment, which we’ll outline here, students should first prepare a two-paragraph summary—a situation analysis—that highlights the key case facts. Then, we task students with providing a five-page PACADI case analysis (excluding appendices) based on the following six steps.

Step 1: Problem definition. What is the major challenge, problem, opportunity, or decision that has to be made? If there is more than one problem, choose the most important one. Often when solving the key problem, other issues will surface and be addressed. The problem statement may be framed as a question; for example, How can brand X improve market share among millennials in Canada? Usually the problem statement has to be re-written several times during the analysis of a case as students peel back the layers of symptoms or causation.

Step 2: Alternatives. Identify in detail the strategic alternatives to address the problem; three to five options generally work best. Alternatives should be mutually exclusive, realistic, creative, and feasible given the constraints of the situation. Doing nothing or delaying the decision to a later date are not considered acceptable alternatives.

Step 3: Criteria. What are the key decision criteria that will guide decision-making? In a marketing course, for example, these may include relevant marketing criteria such as segmentation, positioning, advertising and sales, distribution, and pricing. Financial criteria useful in evaluating the alternatives should be included—for example, income statement variables, customer lifetime value, payback, etc. Students must discuss their rationale for selecting the decision criteria and the weights and importance for each factor.

Step 4: Analysis. Provide an in-depth analysis of each alternative based on the criteria chosen in step three. Decision tables using criteria as columns and alternatives as rows can be helpful. The pros and cons of the various choices as well as the short- and long-term implications of each may be evaluated. Best, worst, and most likely scenarios can also be insightful.

Step 5: Decision. Students propose their solution to the problem. This decision is justified based on an in-depth analysis. Explain why the recommendation made is the best fit for the criteria.

Step 6: Implementation plan. Sound business decisions may fail due to poor execution. To enhance the likeliness of a successful project outcome, students describe the key steps (activities) to implement the recommendation, timetable, projected costs, expected competitive reaction, success metrics, and risks in the plan.

“Students note that using the PACADI framework yields ‘aha moments’—they learned something surprising in the case that led them to think differently about the problem and their proposed solution.”

PACADI’s Benefits: Meaningfully and Thoughtfully Applying Business Concepts

The PACADI framework covers all of the major elements of business decision-making, including implementation, which is often overlooked. By stepping through the whole framework, students apply relevant business concepts and solve management problems via a systematic, comprehensive approach; they’re far less likely to surface piecemeal responses.

As students explore each part of the framework, they may realize that they need to make changes to a previous step. For instance, when working on implementation, students may realize that the alternative they selected cannot be executed or will not be profitable, and thus need to rethink their decision. Or, they may discover that the criteria need to be revised since the list of decision factors they identified is incomplete (for example, the factors may explain key marketing concerns but fail to address relevant financial considerations) or is unrealistic (for example, they suggest a 25 percent increase in revenues without proposing an increased promotional budget).

In addition, the PACADI framework can be used alongside quantitative assignments, in-class exercises, and business and management simulations. The structured, multi-step decision framework encourages careful and sequential analysis to solve business problems. Incorporating PACADI as an overarching decision-making method across different projects will ultimately help students achieve desired learning outcomes. As a practical “beyond-the-classroom” tool, the PACADI framework is not a contrived course assignment; it reflects the decision-making approach that managers, executives, and entrepreneurs exercise daily. Case analysis introduces students to the real-world process of making business decisions quickly and correctly, often with limited information. This framework supplies an organized and disciplined process that students can readily defend in writing and in class discussions.

PACADI in Action: An Example

Here’s an example of how students used the PACADI framework for a recent case analysis on CVS, a large North American drugstore chain.

The CVS Prescription for Customer Value*

PACADI Stage

Summary Response

How should CVS Health evolve from the “drugstore of your neighborhood” to the “drugstore of your future”?

Alternatives

A1. Kaizen (continuous improvement)

A2. Product development

A3. Market development

A4. Personalization (micro-targeting)

Criteria (include weights)

C1. Customer value: service, quality, image, and price (40%)

C2. Customer obsession (20%)

C3. Growth through related businesses (20%)

C4. Customer retention and customer lifetime value (20%)

Each alternative was analyzed by each criterion using a Customer Value Assessment Tool

Alternative 4 (A4): Personalization was selected. This is operationalized via: segmentation—move toward segment-of-1 marketing; geodemographics and lifestyle emphasis; predictive data analysis; relationship marketing; people, principles, and supply chain management; and exceptional customer service.

Implementation

Partner with leading medical school

Curbside pick-up

Pet pharmacy

E-newsletter for customers and employees

Employee incentive program

CVS beauty days

Expand to Latin America and Caribbean

Healthier/happier corner

Holiday toy drives/community outreach

*Source: A. Weinstein, Y. Rodriguez, K. Sims, R. Vergara, “The CVS Prescription for Superior Customer Value—A Case Study,” Back to the Future: Revisiting the Foundations of Marketing from Society for Marketing Advances, West Palm Beach, FL (November 2, 2018).

Results of Using the PACADI Framework

When faculty members at our respective institutions at Nova Southeastern University (NSU) and the University of North Carolina Wilmington have used the PACADI framework, our classes have been more structured and engaging. Students vigorously debate each element of their decision and note that this framework yields an “aha moment”—they learned something surprising in the case that led them to think differently about the problem and their proposed solution.

These lively discussions enhance individual and collective learning. As one external metric of this improvement, we have observed a 2.5 percent increase in student case grade performance at NSU since this framework was introduced.

Tips to Get Started

The PACADI approach works well in in-person, online, and hybrid courses. This is particularly important as more universities have moved to remote learning options. Because students have varied educational and cultural backgrounds, work experience, and familiarity with case analysis, we recommend that faculty members have students work on their first case using this new framework in small teams (two or three students). Additional analyses should then be solo efforts.

To use PACADI effectively in your classroom, we suggest the following:

Advise your students that your course will stress critical thinking and decision-making skills, not just course concepts and theory.

Use a varied mix of case studies. As marketing professors, we often address consumer and business markets; goods, services, and digital commerce; domestic and global business; and small and large companies in a single MBA course.

As a starting point, provide a short explanation (about 20 to 30 minutes) of the PACADI framework with a focus on the conceptual elements. You can deliver this face to face or through videoconferencing.

Give students an opportunity to practice the case analysis methodology via an ungraded sample case study. Designate groups of five to seven students to discuss the case and the six steps in breakout sessions (in class or via Zoom).

Ensure case analyses are weighted heavily as a grading component. We suggest 30–50 percent of the overall course grade.

Once cases are graded, debrief with the class on what they did right and areas needing improvement (30- to 40-minute in-person or Zoom session).

Encourage faculty teams that teach common courses to build appropriate instructional materials, grading rubrics, videos, sample cases, and teaching notes.

When selecting case studies, we have found that the best ones for PACADI analyses are about 15 pages long and revolve around a focal management decision. This length provides adequate depth yet is not protracted. Some of our tested and favorite marketing cases include Brand W , Hubspot , Kraft Foods Canada , TRSB(A) , and Whiskey & Cheddar .

Art Weinstein , Ph.D., is a professor of marketing at Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, Florida. He has published more than 80 scholarly articles and papers and eight books on customer-focused marketing strategy. His latest book is Superior Customer Value—Finding and Keeping Customers in the Now Economy . Dr. Weinstein has consulted for many leading technology and service companies.

Herbert V. Brotspies , D.B.A., is an adjunct professor of marketing at Nova Southeastern University. He has over 30 years’ experience as a vice president in marketing, strategic planning, and acquisitions for Fortune 50 consumer products companies working in the United States and internationally. His research interests include return on marketing investment, consumer behavior, business-to-business strategy, and strategic planning.

John T. Gironda , Ph.D., is an assistant professor of marketing at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. His research has been published in Industrial Marketing Management, Psychology & Marketing , and Journal of Marketing Management . He has also presented at major marketing conferences including the American Marketing Association, Academy of Marketing Science, and Society for Marketing Advances.

Related Articles

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Environ Health Perspect

- v.125(6); 2017 Jun

Advancing Alternative Analysis: Integration of Decision Science

Timothy f. malloy.

1 UCLA School of Law, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Los Angeles, California, USA

2 UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, UCLA, Los Angeles, California, USA

3 University of California Center for the Environmental Implications of Nanotechnology, UCLA, Los Angeles, California, USA

Virginia M. Zaunbrecher

Christina m. batteate.

4 Environmental and Public Health Consulting, Alameda, California, USA

William F. Carroll, Jr.

5 Department of Chemistry, Indiana University Bloomington, Bloomington, Indiana, USA

Charles J. Corbett

6 UCLA Anderson School of Management, UCLA, Los Angeles, California, USA

7 UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, UCLA, Los Angeles, California, USA

Steffen Foss Hansen

8 Department of Environmental Engineering, Technical University of Denmark, Copenhagen, Denmark

Robert J. Lempert

9 RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, California, USA

Igor Linkov

10 U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center, Concord, Massachusetts, USA

Roger McFadden

11 McFadden and Associates, LLC, Oregon, USA

Kelly D. Moran

12 TDC Environmental, LLC, San Mateo, California, USA

Elsa Olivetti

13 Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA

Nancy K. Ostrom

14 Safer Products and Workplaces Program, Department of Toxic Substances Control, Sacramento, California, USA

Michelle Romero

Julie m. schoenung.

15 Henry Samueli School of Engineering, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, California, USA

Thomas P. Seager

16 School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona, USA

Peter Sinsheimer

Kristina a. thayer.

17 Office of Health Assessment and Translation, National Toxicology Program, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Morrisville, North Carolina, USA

Supplemental Material is available online ( https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP483 ).

The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

Note to readers with disabilities: EHP strives to ensure that all journal content is accessible to all readers. However, some figures and Supplemental Material published in EHP articles may not conform to 508 standards due to the complexity of the information being presented. If you need assistance accessing journal content, please contact vog.hin.shein@enilnophe . Our staff will work with you to assess and meet your accessibility needs within 3 working days.

Associated Data

Background:.

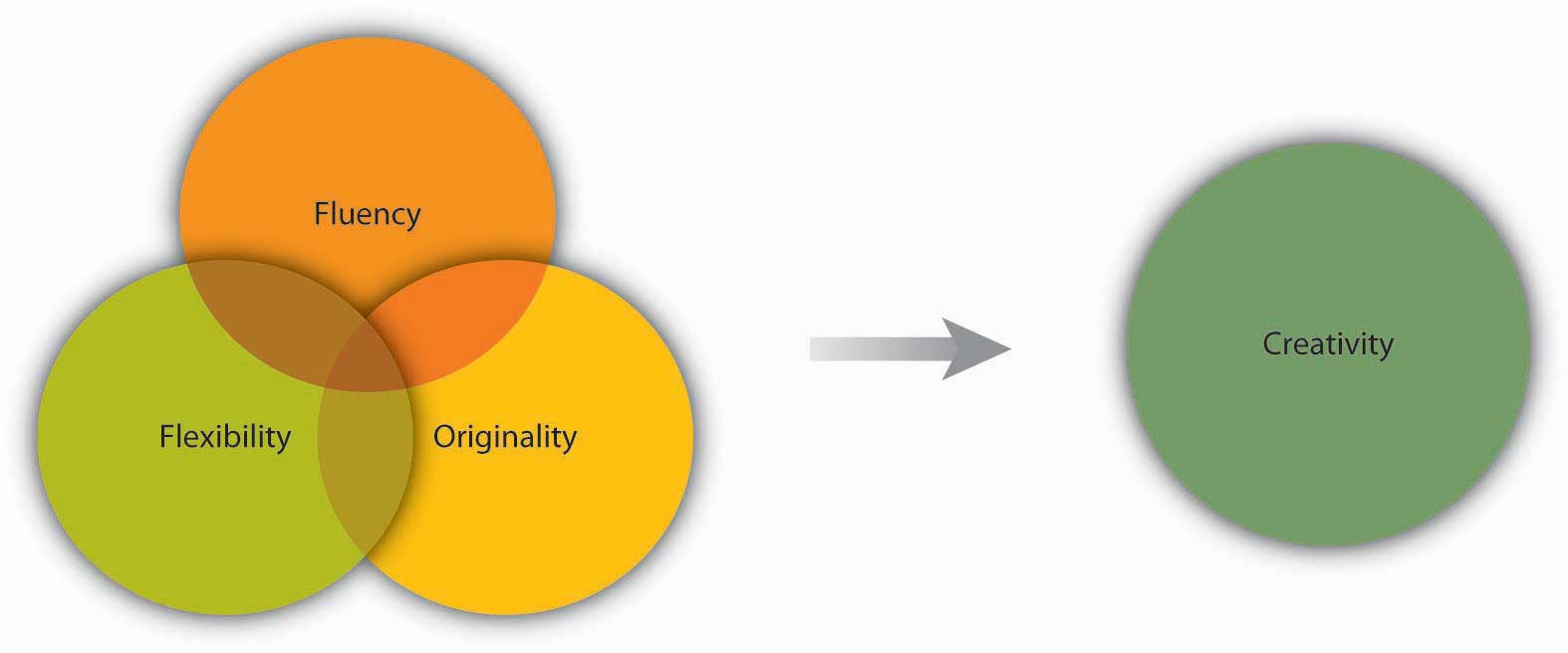

Decision analysis—a systematic approach to solving complex problems—offers tools and frameworks to support decision making that are increasingly being applied to environmental challenges. Alternatives analysis is a method used in regulation and product design to identify, compare, and evaluate the safety and viability of potential substitutes for hazardous chemicals.

Objectives:

We assessed whether decision science may assist the alternatives analysis decision maker in comparing alternatives across a range of metrics.

A workshop was convened that included representatives from government, academia, business, and civil society and included experts in toxicology, decision science, alternatives assessment, engineering, and law and policy. Participants were divided into two groups and were prompted with targeted questions. Throughout the workshop, the groups periodically came together in plenary sessions to reflect on other groups’ findings.

We concluded that the further incorporation of decision science into alternatives analysis would advance the ability of companies and regulators to select alternatives to harmful ingredients and would also advance the science of decision analysis.

Conclusions:

We advance four recommendations: a ) engaging the systematic development and evaluation of decision approaches and tools; b ) using case studies to advance the integration of decision analysis into alternatives analysis; c ) supporting transdisciplinary research; and d ) supporting education and outreach efforts. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP483

Introduction

Policy makers are faced with choices among alternative courses of action on a regular basis. This is particularly true in the environmental arena. For example, air quality regulators must identify the best available control technologies from a suite of options. In the federal program for remediation of contaminated sites, government project managers must propose a clean-up method from a set of feasible alternatives based on nine selection criteria ( U.S. EPA 1990 ). Rule makers in the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) compare a variety of engineering controls and work practices in light of technical feasibility, economic impact, and risk reduction to establish permissible exposure limits ( Malloy 2014 ). At present, as we describe below, some agencies must identify safer, viable alternatives to chemicals for consumer and industrial applications. Such evaluation, known as alternatives analysis, requires balancing numerous, often incommensurable, decision criteria and evaluating the trade-offs among those criteria presented by multiple alternatives.

The University of California Sustainable Technology and Policy Program, in partnership with the University of California Center for Environmental Implications of Nanotechnology (CEIN), hosted a workshop on integrating decision analysis and predictive toxicology into alternatives analysis ( CEIN 2015 ). The workshop brought together approximately 40 leading decision analysts, toxicologists, law and policy experts, and engineers who work in national and state government, academia, the private sector, and civil society for two days of intensive discussions. To provide context for the discussions, the workshop organizers developed a case study regarding the search for alternatives to copper-based marine antifouling paint, which is used to protect the hulls of recreational boats from barnacles, algae, and other marine organisms. Participants received data regarding the health, environmental, technical, and economic performance of a set of alternative paints (see Supplemental Material, “Anti-Fouling Paint Case Study Performance Matrix”). Throughout the workshop, the groups periodically came together in plenary sessions to reflect on other groups’ findings. This article focuses on the workshop discussion and on conclusions regarding decision making.

We first review regulatory decision making in general, and we provide background on selection of safer alternatives to hazardous chemicals using alternatives analysis (AA), also called alternatives assessment. We then summarize relevant decision-making approaches and associated methods and tools that could be applied to AA. The next section outlines some of the challenges associated with decision making in AA and the role that various decision approaches could play in resolving them. After setting out four principles for integrating decision analysis into AA, we advance four recommendations for driving integration forward.

Regulatory Decision Making and Selection of Safer Alternatives

The consequences of regulatory decisions can have broad implications in areas such as human health and the environment. Yet within the regulatory context, these complex decision tasks are traditionally performed using an ad hoc approach, that is to say, without the aid of formal decision analysis methods or tools ( Eason et al. 2011 ). As we discuss later, such ad hoc approaches raise serious concerns regarding the consistency of outcomes across different cases; the transparency, predictability, and objectivity of the decision-making process; and human cognitive capacity in managing and synthesizing diverse, rich streams of information. Identifying a systematic framework for making effective, transparent, and objective decisions within the dynamic and complex regulatory milieu can significantly mitigate those concerns ( NAS 2005 ). In its 2005 report, the NAS called for a program of research in environmental decision making focused on:

[I]mproving the analytical tools and analytic-deliberative processes necessary for good environmental decision making. It would include three components: developing criteria of decision quality; developing and testing formal tools for structuring decision processes; and creating effective processes, often termed analytic-deliberative, in which a broad range of participants take important roles in environmental decisions, including framing and interpreting scientific analyses. ( NAS 2005 )

Since that call, significant research has been performed regarding decision making related to environmental issues, particularly in the context of natural resource management, optimization of water and coastal resources, and remediation of contaminated sites ( Gregory et al. 2012 ; Huang et al. 2011 ; Yatsalo et al. 2007 ). This work has begun the process of evaluating the application of formal decision approaches to environmental decision making, but numerous challenges remain, particularly with respect to the regulatory context. In fact, very few studies have focused on the application of decision-making tools and processes in the context of formal regulatory programs, taking into account the legal, practical, and resource constraints present in such settings ( Malloy et al. 2013 ; Parnell et al. 2001 ). We focus upon the use of decision analysis in the context of environmental chemicals.

The challenge of making choices among alternatives is central in an emerging approach to chemical policy, which turns from conventional risk management to embrace prevention-based approaches to regulating chemicals. Conventional risk management essentially focuses upon limiting exposure to a hazardous chemical to an acceptable level through engineering and administrative controls. In contrast, a prevention-based approach seeks to minimize the use of toxic chemicals by mandating, directly incentivizing, or encouraging the adoption of viable safer alternative chemicals or processes ( Malloy 2014 ). Thus, under a prevention-based approach, the regulatory agency would encourage or even mandate use of what it views as an inherently safer process using a viable alternative plating technique. Adopting a prevention-based approach, however, presents its own challenging choice—identifying a safer, viable alternative. Effective prevention-based regulation requires a regulatory AA methodology for comparing and evaluating the regulated chemical or process and its alternatives across a range of relevant criteria.

AA is a scientific method for identifying, comparing, and evaluating competing courses of action. In the case of chemical regulation, it is used to determine the relative safety and viability of potential substitutes for existing products or processes that use hazardous chemicals ( NAS 2014 ; Malloy et al. 2013 ). For example, a business manufacturing nail polish containing a resin made using formaldehyde would compare its product with alternative formulations using other resins. Alternatives may include drop-in chemical substitutes, material substitutes, changes to manufacturing operations, and changes to component/product design ( Sinsheimer et al. 2007 ). The methodology compares the alternatives with the regulated product and with one another across a variety of attributes, typically including public health impacts, environmental effects, and technical performance, as well as economic impacts on the manufacturer and on the consumer. The methodology identifies trade-offs between the alternatives and evaluates the relative overall performance of the original product and its alternatives.

In the regulatory setting, multiple parties may be involved to varying degrees in the generation of an AA. Typically, the regulated firm is required to perform the AA in the first instance, as in the California Safer Consumer Products program and the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) authorization process ( DTSC 2013 ; European Parliament and Council 2006 ). The AA, which may be done within the firm or by an outside consultant retained by the firm, is generally performed by an interdisciplinary team of experts (hereafter collectively referred to as the “analyst”) ( DTSC 2013 ). The firm submits the AA to the regulatory agency for review. The regulatory agency will often propose a final decision regarding whether a viable, safer alternative exists and the appropriate regulatory action to take. ( DTSC 2013 ; European Parliament and Council 2006 ). Possible regulatory actions include a ban on the existing product, adoption of an alternative, product labeling, use restrictions, or end-of-life management. Stakeholders such as other government agencies, environmental groups, trade associations, and the general public may provide comments on the AA and regulatory response. Ultimately, the agency retains the authority to require revisions to the analysis and has the final say over the regulatory response ( Malloy 2014 ).

Development of effective regulatory AA methods is a pressing and timely public policy issue. Regulators in California, Maine, and Washington are implementing new programs that call for manufacturers to identify and evaluate potential safer alternatives to toxic chemicals in products ( DTSC 2013 ; MDEP 2012 ; Department of Ecology, Washington State 2015 ). At the federal level, in the last few years, the U.S. Environmental Health Protection Agency ( EPA ) began to use AA as part of “chemical action plans” in its chemical management program ( Lavoie et al. 2010 ). In the European Union, the REACH program imposes AA obligations upon manufacturers seeking authorization for the continued use of certain substances of very high concern ( European Parliament and Council 2006 ). The stakes in developing effective approaches to regulatory AA are high. A flawed AA methodology can inhibit the identification and adoption of safer alternatives or support the selection of an undesirable alternative (often termed “regrettable substitution”). An example of the former is the U.S. EPA’s attempt in the late 1980s to ban asbestos, which was rejected by a federal court that concluded, among other things, that the AA method used by the agency did not adequately evaluate the feasibility and safety of the alternatives ( Corrosion ProoFittings v. EPA 1991 ). Regrettable substitution is illustrated by the case of antifouling paints used to combat the buildup of bacteria, algae, and invertebrates such as barnacles on the hulls of recreational boats. As countries throughout the world banned highly toxic tributyltin in antifouling paints in the late 1980s, manufacturers turned to copper as an active ingredient ( Dafforn et al. 2011 ). The cycle is now being repeated as regulatory agencies began efforts to phase out copper-based antifouling paint because of its adverse impacts on the marine environment ( Carson et al. 2009 ).

AA frameworks and methods abound, yet few directly address how decision makers should select or rank the alternatives. As the 2014 NAS report on AA observed, “[m]any frameworks … do not consider the decision-making process or decision rules used for resolving trade-offs among different categories of toxicity and other factors (e.g., social impact), or the values that underlie such trade-offs” ( NAS 2014 ). Similarly, a recent review of 20 AA frameworks and guides identified methodological gaps regarding the use of explicit decision frameworks and the incorporation of decision-maker values ( Jacobs et al. 2016 ). The lack of attention to the decision-making process is particularly problematic in regulatory AA, in which the regulated entity, the government agency, and the stakeholders face significant challenges related to the complexity of the decisions, uncertainty of data, difficulty in identifying alternatives, and incorporation of decision-maker values. We discuss these challenges in detail below.

A variety of decision analysis tools and approaches can assist policy makers, product and process designers, and other stakeholders who face the challenging decision environment presented by AA. For these purposes, decision analysis is “a systematic approach to evaluating complex problems and enhancing the quality of decisions.” ( Eason et al. 2011 ). Although formal decision analysis methods and tools suitable for such situations are well developed ( Linkov and Moberg 2012 ), for the reasons discussed below, they are rarely applied in existing AA practice. The range of decision analysis methods and tools is quite broad, requiring development of principles for selecting and implementing the most appropriate ones for varied regulatory and private settings. Following an overview of the architecture of decision making in AA, we examine how various formal and informal decision approaches can assist decision makers in meeting the four challenges identified above. We conclude by offering a set of principles for developing effective AA decision-making approaches and steps for advancing the integration of decision analysis into AA practice.

Overview of Decision Making in Alternatives Analysis

In the case of regulatory AA, the particular decision or decisions to be made will depend significantly upon the requirements and resources of the regulatory program in question. For example, the goal may be to identify a single optimal alternative, to rank the entire set of alternatives, or to simply differentiate between acceptable and unacceptable alternatives ( Linkov et al. 2006 ). As a general matter, however, the architecture of decision making is shaped by two factors: the decision framework adopted and the decision tools or methods used. For our purposes, the term “decision framework” means the overall structure or order of the decision making, consisting of particular steps in a certain order. Decision tools and methods are defined below.

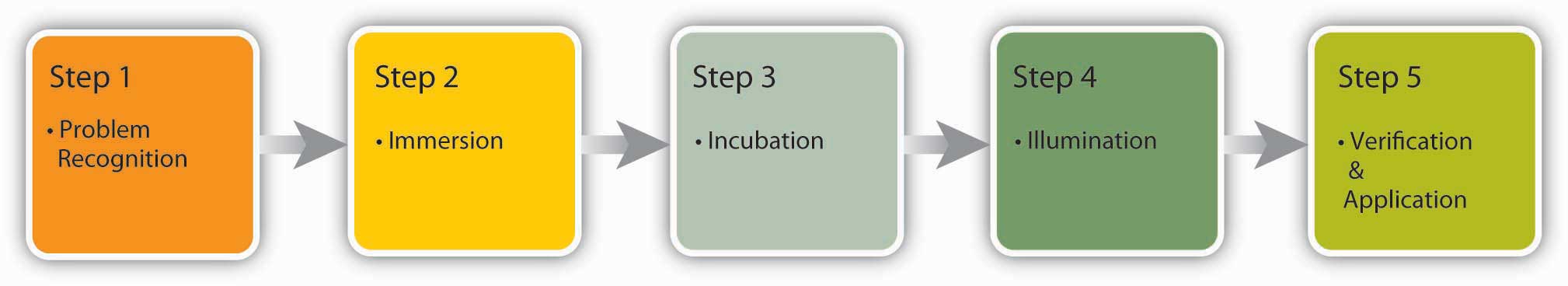

Decision Frameworks

Existing AA approaches that explicitly address decision making use any of three general decision frameworks: sequential, simultaneous, and mixed ( Figure 1 ). The sequential framework includes a set of attributes, such as human health, environmental impacts, economic feasibility, and technical feasibility, which are addressed in succession. The first attribute addressed is often human health or technical feasibility because it is assumed that any alternative that does not meet minimum performance requirements should not proceed with further evaluation. Only the most favorable alternatives proceed to the next step for evaluation, which continues until one or more acceptable alternatives are identified ( IC2 2013 ; Malloy et al. 2013 ).

Decision frameworks. Compares the process for decision making under sequential, simultaneous, and mixed frameworks.

The simultaneous framework considers all or a set of the attributes at once, allowing good performance on one attribute to offset less favorable performance on another for a given alternative. Thus, one alternative’s lackluster performance in terms of cost might be offset by its superior technical performance, a concept known as compensation ( Giove et al. 2009 ). This type of trade-off is not generally available in the sequential framework across major decision criteria. Nevertheless, it is important to note that even within a sequential framework, the simultaneous framework may be lurking where a major decision criterion consists of sub-criteria. For example, in most AA approaches, the human health criterion has numerous sub-criteria reflecting various forms of toxicity such as carcinogenicity, acute toxicity, and neurotoxicity. Even within a sequential framework, the decision maker may consider all of those subcriteria simultaneously when comparing the alternatives with respect to human health ( NAS 2014 ; IC2 2013 ).

The mixed or hybrid framework, as one might expect, is a combination of the sequential and simultaneous approaches ( NAS 2014 ; IC2 2013 ; Malloy et al. 2013 ). For example, if technical feasibility is of particular importance to an analyst, she may screen out certain alternatives on that basis, and subsequently apply a simultaneous framework to the remaining alternatives regarding the other decision criteria. A recent study of 20 existing AA approaches observed substantial variance in the framework adopted: no framework (7 approaches), mixed (6 approaches), simultaneous (4 approaches), menu of all three frameworks (2 approaches), and sequential (1 approach) ( Jacobs et al. 2016 ).

Decision Methods and Tools

There are a wide range of decision tools and methods, that is to say, formal and informal aids, rules, and techniques that guide particular steps within a decision framework ( NAS 2014 ; Malloy et al. 2013 ). These methods and tools range from informal rules of thumb to highly complex, statistically based methodologies. The various methods and tools have diverse approaches and distinctive theoretical bases, and they address data uncertainty, the relative importance of decision criteria, and other issues differently. For example, some methods quantitatively incorporate the decision maker’s relative preferences regarding the importance of decision criteria (a process sometimes called “weighting”), whereas others make no provision for explicit weighting. For our purposes, they can be broken into four general types: a ) narrative, b ) elementary, c ) multicriteria decision analysis (MCDA), and d ) robust scenario analysis. Each type can be used for various decisions in an AA, such as winnowing down the initial set of potential alternatives or for ranking the alternatives. As Figure 2 illustrates, in the context of a mixed decision framework, two different decision tools and methods could even be used at different decision points within a single AA.

Multiple decision tool use in mixed decision framework. Demonstrates one potential scenario for using multiple decision tools in one chemical selection process. (Derived from Jacobs et al. 2016 ).

Narrative Approaches

In the narrative approach, also known as the ad hoc approach, the decision maker engages in a holistic, qualitative balancing of the data and associated trade-offs to arrive at a selection ( Eason et al. 2011 ; Linkov et al. 2006 ). In some cases, the analyst may rely on explicitly stated informal decision principles or on expert judgment to guide the process. No quantitative scores are assigned to alternatives for the purposes of the comparison. Similarly, no explicit quantitative weighting is used to reflect the relative importance of the decision criteria, although in some instances, qualitative weighting may be provided for the analyst by the firm charged with performing the AA. The AA methodology developed by the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) for substances that are subject to authorization under REACH is illustrative ( ECHA 2011 ). Similarly, the AA requirements set out in the regulations for the California Safer Consumer Products program, which mandates that manufacturers complete AAs for certain priority products, adopt the ad hoc approach, setting out broad, narrative decision rules without explicit weighting ( DTSC 2013 ). This approach could be particularly subject to various biases in decision making, which we will address later.

Elementary Approaches

Elementary approaches apply a more systematic overlay to the narrative approach, providing the analyst with specific guidance about how to make a decision. Such approaches provide an observable path for the decision process but typically do not require sophisticated software or specialized expertise. For example, Hansen and colleagues developed the NanoRiskCat tool for prioritization of nanomaterials in consumer products ( Hansen et al. 2014 ). The structure may take the form of a decision tree that takes the analyst through an ordered series of questions. Alternatively, it may offer a set of checklists, specific decision rules, or simple algorithms to assist the analyst in framing the issues and guiding the evaluation. Elementary approaches can make use of both quantitative and qualitative data and may incorporate implicit or explicit weighting of the decision criteria ( Linkov et al. 2004 ).

MCDA Approaches

The MCDA approach couples a narrative evaluation with mathematically based formal decision analysis tools, such as multi-attribute utility theory (MAUT) and outranking. The output of the selected MCDA analysis is intended as a guide for the decision maker and as a reference for stakeholders affected by or otherwise interested in the decision. MCDA itself consists of a range of different methods and tools, reflecting various theoretical bases and methodological perspectives. Accordingly, those methods and tools tend to assess the data and generate rankings in different ways ( Huang et al. 2011 ). However, they generally share certain common features, setting them apart from the type of informal decision making present in the narrative approach. Each MCDA approach provides a systematic, observable process for evaluating alternatives in which an alternative’s performance across the decision criteria is aggregated to generate a score. Each alternative is then ranked relative to the other alternatives based on its aggregate score. Figure 3 provides an example of the type of ranking generated from an MAUT tool. In most of these types of ranking approaches, the individual criteria scores are weighted to reflect the relative importance of the decision criteria and sub-criteria ( Kiker et al. 2005 ; Belton and Stewart 2002 ).

Sample output from MAUT decision tool comparing alternatives to lead solder. SnPb is a solder alloy composed of 63% Sn/37% Pb; SAC (Water) is a solder alloy composed of 95.5% Sn/3.9% Ag/0.6% Cu; water quenching is used to cool and harden solder; SAC (air) is a solder alloy composed of 95.5% Sn/3.9% Ag/0.6% Cu; air is used to cool and harden solder; SnCu (water) is a solder alloy composed of 99.2% Sn/0.8% Cu; water quenching is used to cool and harden solder; SnCu (air) solder alloy composed of 99.2% Sn/0.8% Cu; air is used to cool and harden solder [ Malloy et al. 2013 with permission from Wiley Online Library http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1002/(ISSN)1551-3793/homepage/Permissions.html )]. Note: Ag, silver; Cu, copper; Pb, lead; Sn, tin.

Some MCDA tools, such as MAUT, are optimization tools that seek to maximize the achievement of the decision maker’s preferences. These optimization approaches use utility functions, dimensionless scales that range from 0 to 1, to convert the measured performance of an alternative for a given decision criterion to a score between 0 and 1 ( Malloy et al. 2013 ). In contrast, outranking methods do not create utility functions or seek optimal alternatives. Instead, outranking methods seek the alternative that outranks other alternatives in terms of overall performance, also known as the dominant alternative ( Belton and Stewart 2002 ). The diverse MCDA tools use various approaches to address uncertainty regarding the performance of alternatives and the relative importance to be placed on respective attributes. Some, such as MAUT, use point values for performance and weighting and rely upon sensitivity analysis to evaluate the impact of uncertainty ( Malloy et al. 2013 ). Sensitivity analysis evaluates how different values of uncertain attributes or weights would affect the ranking of the alternatives. Others, such as stochastic multi-criteria acceptability analysis (SMAA), represent performance information and relative weights as probability distributions ( Lahdelma and Salminen 2010 ). Still others, such as multi-criteria mapping, rely on a part-quantitative, part-qualitative approach in which the analyst facilitates structured evaluation of alternatives by the ultimate decision maker, eliciting judgments from the decision maker regarding the performance of the respective alternatives on relevant attributes and on the relative importance of those attributes. The analyst then generates a ranking based upon that input ( SPRU 2014 ; Hansen 2010 ). MCDA has been used, though not extensively, in the related field of life-cycle assessment (LCA) ( Prado et al. 2012 ). For example, Wender et al. ( 2014 ) integrated LCA with MCDA methods to compare existing and emerging photovoltaic technologies.

Robust Scenario Approaches

Robust scenario analysis is particularly useful when decision makers face deep uncertainty, meaning situations in which the decision makers do not know or cannot agree upon the likely performance of one or more alternatives on important criteria ( Lempert and Collins 2007 ). Robust scenario analysis uses large ensembles of scenarios to visualize all plausible, relevant futures for each alternative. With this range of potential futures in mind, it helps decision makers to compare the alternatives in search of the most robust alternative. A robust alternative is one that performs well across a wide range of plausible scenarios even though it may not be optimal or dominant in any particular one ( Kalra et al. 2014 ).

Robust scenario decision making consists of four iterative steps. First, the decision makers define the decision context, identifying goals, uncertainties, and potential alternatives under consideration. Second, modelers generate ensembles of hundreds, thousands, or even more scenarios, each reflecting an outcome flowing from different plausible assumptions about how each alternative may perform. Third, quantitative analysis and visualization software is used to explore the benefits and drawbacks of the alternatives across the range of scenarios. Finally, trade-off analysis (i.e., comparative assessment of the relative pros and cons of the alternatives) is used to evaluate the alternatives and to identify a robust strategy ( Lempert et al. 2013 ).

Decision-Making Challenges Presented by Alternatives Analysis

Like many decisions involving multiple criteria, identifying a safer viable alternative or set of alternatives is often difficult. Finding potential alternatives, collecting information about their performance, and evaluating the trade-offs posed by each alternative are all laden with problems. Those difficulties are exacerbated in the regulatory setting because of additional constraints associated with that regulatory setting, such as the need for accountability, transparency, and consistency across similar cases ( Malloy et al. 2015 ). In this review, we focus on four challenges that are recognized in the decision analysis field to be of particular importance to regulatory AA:

- • Dealing with large numbers of attributes

- • Uncertainty in performance data

- • Poorly understood option space

- • Incorporating decision-maker values (sometimes called weighting of attributes)

Large Numbers of Attributes

In its essential form, AA focuses upon human health, environmental impacts, technical performance, and economic impact. But in fact, AA involves many more than four attributes. Each of the four major attributes, particularly human health, includes numerous sub-attributes, many more than any human can process without some form of heuristic or computational aid. An example is the case of California Safer Consumer Products regulations, which require that an AA consider all relevant “hazard traits” ( DTSC 2013 ). Hazard traits are “properties of chemicals that fall into broad categories of toxicological, environmental, exposure potential, and physical hazards that may contribute to adverse effects …” ( DTSC 2013 ). For human health alone, the California regulations identify twenty potentially relevant hazard traits ( DTSC 2013 ). Similarly, the U.S. EPA considers a total of twelve hazard end points in assessing impacts to human health in its alternatives assessment guidance ( U.S. EPA 2011 ).

Large numbers of attributes raise two types of difficulties. First, as the number of attributes increases, data collection regarding the performance of the baseline product and its alternatives becomes increasingly difficult, time-consuming, and expensive. Because not all attributes listed in regulations or guidance documents will be salient or have an impact in every case, decision-making approaches that judiciously sift out irrelevant or less-important attributes are desirable. Second, given humans’ cognitive limitations, larger numbers of relevant attributes complicate the often inevitable trade-off analysis that is needed in AA. Consider an example of two alternative solders, one of which performs best in terms of low carcinogenicity, neurotoxicity, acute aquatic toxicity, and wettability (a very desirable feature for solders), but not so well with respect to endocrine disruption, respiratory toxicity, chronic aquatic toxicity, and tensile strength (another advantageous feature for solders). Suppose the second alternative presents the opposite profile. Now, add dozens of other attributes relating to human health and safety, environmental impacts, and technical and economic performance to the mix. Even in the relatively simple case of one baseline product and two potential alternatives, evaluating and resolving the trade-offs can be treacherous. In assessing the alternatives, decision makers must determine whether and how to compensate for poor performance on some attributes with superior performance on other attributes. Similarly, the nature and scale of the performance data for the attributes varies wildly; using fundamentally different metrics for diverse attributes generates a mixture of quantitative and qualitative information.

Decision frameworks and methods should provide principled approaches to integrating or normalizing such information to support trade-off analysis. Elementary approaches often use ordinal measures of performance to normalize diverse types of data. For example, the U.S. EPA AA methodology under the Design for the Environment program characterizes performance on a variety of human health and environmental attributes as “low,” “medium,” or “high” ( U.S. EPA 2011 ). The increased tractability comes with some decrease in precision, potentially obscuring meaningful differences in performance or exaggerating differences at the margins. As the number of relevant attributes increases, it becomes more difficult to rely upon narrative and elementary approaches to manage the diverse types of data and to evaluate the trade-offs presented by the alternatives. MCDA approaches are well suited for handling large numbers of attributes and diverse forms of data. ( Kiker et al. 2005 ). In an AA case study using an MCDA method to evaluate alternatives to lead-based solder, researchers used an internal normalization approach to convert an alternative’s scores on each criterion to dimensionless units ranging from 0 to 1 and then applied an optimization algorithm to trade-offs across more than fifty attributes ( Malloy et al. 2013 ).

Uncertain Data Regarding Attributes

Uncertainty is not unique to AA; it presents challenges in conventional risk assessment and in many environmental decision-making situations. However, the diversity and number of the relevant data streams and potential trade-offs faced in AA exacerbate the problem of uncertainty. In thinking through uncertainty in this context, three considerations stand out: defining it, responding to it methodologically, and communicating about it to stakeholders.

The meaning of the term “uncertainty” is itself uncertain; definitions abound ( NAS 2009 ; Ascough et al. 2008 ). For our purposes, uncertainty includes a complete or partial lack of information, or the existence of conflicting information or variability, regarding an alternative’s performance on one or more attributes, such as health effects, potential exposure, or economic impact ( NAS 2009 ). Uncertainty includes “data gaps” resulting from a lack of experimental studies, measurements, or other empirical observations, along with situations in which available studies or modeling provide a range of differing data for the same attribute ( NAS 2014 ; Ascough et al. 2008 ). It also includes limitations inherent in data generation and modeling such as measurement error and use of modeling assumptions, as well as naturally occurring variability caused by heterogeneity or diversity in the relevant populations, materials, or systems. Uncertainty regarding the strength of the decision maker’s preferences, also known as value uncertainty, is discussed below.

There are a variety of methodological approaches for dealing with uncertainty. Some approaches (typically within narrative or elementary approaches) simply call for identification and discussion of missing data or use simple heuristics to deal with uncertainties, for example by assuming a worst-case performance for that attribute ( DTSC 2013 ; Rossi et al. 2006 ). Others rely upon expert judgment (often in the form of expert elicitation) to fill data gaps ( Rossi et al. 2012 ). Although MCDA approaches can make similar use of simple heuristics and expert estimations, they also provide a variety of more sophisticated mechanisms for dealing with uncertainty ( Malloy et al. 2013 ; Hyde et al. 2003 ). Simple forms of sensitivity analysis in which single input values are modified to observe the effect on the MCDA results are also often used at the conclusion of the decision analysis process—the lead-based solder study used this approach to assess the robustness of its outcomes—although this type of ad hoc analysis has significant limitations ( Malloy et al. 2013 ; Hyde et al. 2003 ).

Diverse MCDA methods also offer a variety of quantitative probabilistic approaches relying upon such tools as Monte Carlo analysis, fuzzy sets, and Bayesian networks to investigate the range of outcomes associated with different values for the uncertain attribute ( Lahdelma and Salminen 2010 ). Canis and colleagues used a stochastic decision-analytic technique to address uncertainty in an evaluation of four different processes for synthesizing carbon nanotubes (arc, high-pressure carbon monoxide, chemical vapor deposition, and laser) across five performance criteria. Rather than generating an ordered ranking of the alternatives from first to last, the method provided an estimate of the probability that each alternative would occupy each rank ( Canis et al. 2010 ). Robust scenario analysis takes a different approach, using large ensembles of scenarios in an attempt to visualize all plausible, relevant futures for each alternative. With this range of potential futures in mind, decision makers are enabled to compare the alternatives in search of the most robust alternative given the uncertainties ( Lempert and Collins 2007 ).

Choosing among these approaches to uncertainty is not trivial. Studies in the decision analysis literature (and in the context of multi-criteria choices in particular) demonstrate that the approach taken with respect to uncertainty can substantially affect decision outcomes ( Hyde et al. 2003 ; Durbach and Stewart 2011 ). For example, one heuristic approach—called the “uncertainty downgrade”—essentially penalizes an alternative with missing data by assuming the worst with respect to the affected attribute. In some cases, such a penalty default may encourage proponents of the alternative to generate more complete data, but it may also lead to the selection of less-safe but more-studied alternatives ( NAS 2014 ).