- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2021

A scoping review of the literature featuring research ethics and research integrity cases

- Anna Catharina Vieira Armond ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7121-5354 1 ,

- Bert Gordijn 2 ,

- Jonathan Lewis 2 ,

- Mohammad Hosseini 2 ,

- János Kristóf Bodnár 1 ,

- Soren Holm 3 , 4 &

- Péter Kakuk 5

BMC Medical Ethics volume 22 , Article number: 50 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

25 Citations

28 Altmetric

Metrics details

The areas of Research Ethics (RE) and Research Integrity (RI) are rapidly evolving. Cases of research misconduct, other transgressions related to RE and RI, and forms of ethically questionable behaviors have been frequently published. The objective of this scoping review was to collect RE and RI cases, analyze their main characteristics, and discuss how these cases are represented in the scientific literature.

The search included cases involving a violation of, or misbehavior, poor judgment, or detrimental research practice in relation to a normative framework. A search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, SCOPUS, JSTOR, Ovid, and Science Direct in March 2018, without language or date restriction. Data relating to the articles and the cases were extracted from case descriptions.

A total of 14,719 records were identified, and 388 items were included in the qualitative synthesis. The papers contained 500 case descriptions. After applying the eligibility criteria, 238 cases were included in the analysis. In the case analysis, fabrication and falsification were the most frequently tagged violations (44.9%). The non-adherence to pertinent laws and regulations, such as lack of informed consent and REC approval, was the second most frequently tagged violation (15.7%), followed by patient safety issues (11.1%) and plagiarism (6.9%). 80.8% of cases were from the Medical and Health Sciences, 11.5% from the Natural Sciences, 4.3% from Social Sciences, 2.1% from Engineering and Technology, and 1.3% from Humanities. Paper retraction was the most prevalent sanction (45.4%), followed by exclusion from funding applications (35.5%).

Conclusions

Case descriptions found in academic journals are dominated by discussions regarding prominent cases and are mainly published in the news section of journals. Our results show that there is an overrepresentation of biomedical research cases over other scientific fields compared to its proportion in scientific publications. The cases mostly involve fabrication, falsification, and patient safety issues. This finding could have a significant impact on the academic representation of misbehaviors. The predominance of fabrication and falsification cases might diverge the attention of the academic community from relevant but less visible violations, and from recently emerging forms of misbehaviors.

Peer Review reports

There has been an increase in academic interest in research ethics (RE) and research integrity (RI) over the past decade. This is due, among other reasons, to the changing research environment with new and complex technologies, increased pressure to publish, greater competition in grant applications, increased university-industry collaborative programs, and growth in international collaborations [ 1 ]. In addition, part of the academic interest in RE and RI is due to highly publicized cases of misconduct [ 2 ].

There is a growing body of published RE and RI cases, which may contribute to public attitudes regarding both science and scientists [ 3 ]. Different approaches have been used in order to analyze RE and RI cases. Studies focusing on ORI files (Office of Research Integrity) [ 2 ], retracted papers [ 4 ], quantitative surveys [ 5 ], data audits [ 6 ], and media coverage [ 3 ] have been conducted to understand the context, causes, and consequences of these cases.

Analyses of RE and RI cases often influence policies on responsible conduct of research [ 1 ]. Moreover, details about cases facilitate a broader understanding of issues related to RE and RI and can drive interventions to address them. Currently, there are no comprehensive studies that have collected and evaluated the RE and RI cases available in the academic literature. This review has been developed by members of the EnTIRE consortium to generate information on the cases that will be made available on the Embassy of Good Science platform ( www.embassy.science ). Two separate analyses have been conducted. The first analysis uses identified research articles to explore how the literature presents cases of RE and RI, in relation to the year of publication, country, article genre, and violation involved. The second analysis uses the cases extracted from the literature in order to characterize the cases and analyze them concerning the violations involved, sanctions, and field of science.

This scoping review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). The full protocol was pre-registered and it is available at https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5bde92120&appId=PPGMS .

Eligibility

Articles with non-fictional case(s) involving a violation of, or misbehavior, poor judgment, or detrimental research practice in relation to a normative framework, were included. Cases unrelated to scientific activities, research institutions, academic or industrial research and publication were excluded. Articles that did not contain a substantial description of the case were also excluded.

A normative framework consists of explicit rules, formulated in laws, regulations, codes, and guidelines, as well as implicit rules, which structure local research practices and influence the application of explicitly formulated rules. Therefore, if a case involves a violation of, or misbehavior, poor judgment, or detrimental research practice in relation to a normative framework, then it does so on the basis of explicit and/or implicit rules governing RE and RI practice.

Search strategy

A search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, SCOPUS, JSTOR, Ovid, and Science Direct in March 2018, without any language or date restrictions. Two parallel searches were performed with two sets of medical subject heading (MeSH) terms, one for RE and another for RI. The parallel searches generated two sets of data thereby enabling us to analyze and further investigate the overlaps in, differences in, and evolution of, the representation of RE and RI cases in the academic literature. The terms used in the first search were: (("research ethics") AND (violation OR unethical OR misconduct)). The terms used in the parallel search were: (("research integrity") AND (violation OR unethical OR misconduct)). The search strategy’s validity was tested in a pilot search, in which different keyword combinations and search strings were used, and the abstracts of the first hundred hits in each database were read (Additional file 1 ).

After searching the databases with these two search strings, the titles and abstracts of extracted items were read by three contributors independently (ACVA, PK, and KB). Articles that could potentially meet the inclusion criteria were identified. After independent reading, the three contributors compared their results to determine which studies were to be included in the next stage. In case of a disagreement, items were reassessed in order to reach a consensus. Subsequently, qualified items were read in full.

Data extraction

Data extraction processes were divided by three assessors (ACVA, PK and KB). Each list of extracted data generated by one assessor was cross-checked by the other two. In case of any inconsistencies, the case was reassessed to reach a consensus. The following categories were employed to analyze the data of each extracted item (where available): (I) author(s); (II) title; (III) year of publication; (IV) country (according to the first author's affiliation); (V) article genre; (VI) year of the case; (VII) country in which the case took place; (VIII) institution(s) and person(s) involved; (IX) field of science (FOS-OECD classification)[ 7 ]; (X) types of violation (see below); (XI) case description; and (XII) consequences for persons or institutions involved in the case.

Two sets of data were created after the data extraction process. One set was used for the analysis of articles and their representation in the literature, and the other set was created for the analysis of cases. In the set for the analysis of articles, all eligible items, including duplicate cases (cases found in more than one paper, e.g. Hwang case, Baltimore case) were included. The aim was to understand the historical aspects of violations reported in the literature as well as the paper genre in which cases are described and discussed. For this set, the variables of the year of publication (III); country (IV); article genre (V); and types of violation (X) were analyzed.

For the analysis of cases, all duplicated cases and cases that did not contain enough information about particularities to differentiate them from others (e.g. names of the people or institutions involved, country, date) were excluded. In this set, prominent cases (i.e. those found in more than one paper) were listed only once, generating a set containing solely unique cases. These additional exclusion criteria were applied to avoid multiple representations of cases. For the analysis of cases, the variables: (VI) year of the case; (VII) country in which the case took place; (VIII) institution(s) and person(s) involved; (IX) field of science (FOS-OECD classification); (X) types of violation; (XI) case details; and (XII) consequences for persons or institutions involved in the case were considered.

Article genre classification

We used ten categories to capture the differences in genre. We included a case description in a “news” genre if a case was published in the news section of a scientific journal or newspaper. Although we have not developed a search strategy for newspaper articles, some of them (e.g. New York Times) are indexed in scientific databases such as Pubmed. The same method was used to allocate case descriptions to “editorial”, “commentary”, “misconduct notice”, “retraction notice”, “review”, “letter” or “book review”. We applied the “case analysis” genre if a case description included a normative analysis of the case. The “educational” genre was used when a case description was incorporated to illustrate RE and RI guidelines or institutional policies.

Categorization of violations

For the extraction process, we used the articles’ own terminology when describing violations/ethical issues involved in the event (e.g. plagiarism, falsification, ghost authorship, conflict of interest, etc.) to tag each article. In case the terminology was incompatible with the case description, other categories were added to the original terminology for the same case. Subsequently, the resulting list of terms was standardized using the list of major and minor misbehaviors developed by Bouter and colleagues [ 8 ]. This list consists of 60 items classified into four categories: Study design, data collection, reporting, and collaboration issues. (Additional file 2 ).

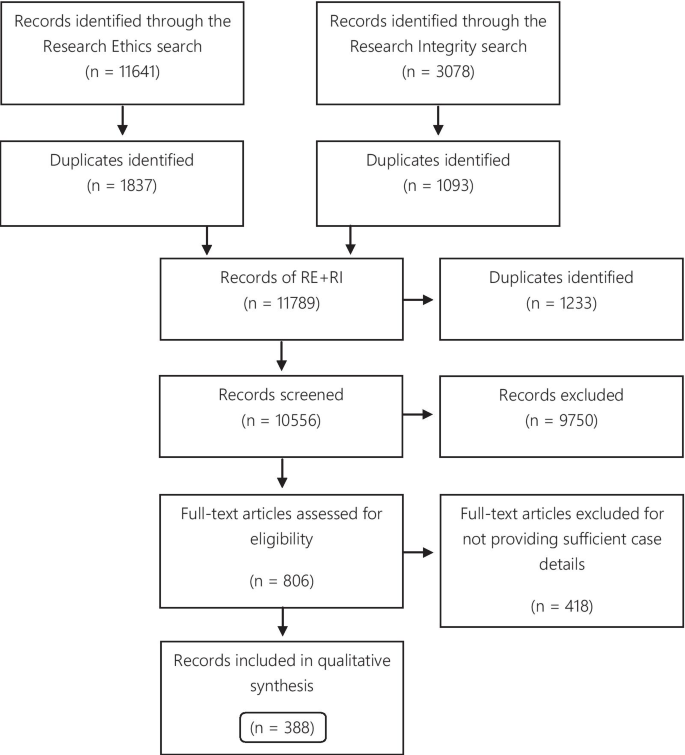

Systematic search

A total of 11,641 records were identified through the RE search and 3078 in the RI search. The results of the parallel searches were combined and the duplicates removed. The remaining 10,556 records were screened, and at this stage, 9750 items were excluded because they did not fulfill the inclusion criteria. 806 items were selected for full-text reading. Subsequently, 388 articles were included in the qualitative synthesis (Fig. 1 ).

Flow diagram

Of the 388 articles, 157 were only identified via the RE search, 87 exclusively via the RI search, and 144 were identified via both search strategies. The eligible articles contained 500 case descriptions, which were used for the analysis of the publications articles analysis. 256 case descriptions discussed the same 50 cases. The Hwang case was the most frequently described case, discussed in 27 articles. Furthermore, the top 10 most described cases were found in 132 articles (Table 1 ).

For the analysis of cases, 206 (41.2% of the case descriptions) duplicates were excluded, and 56 (11.2%) cases were excluded for not providing enough information to distinguish them from other cases, resulting in 238 eligible cases.

Analysis of the articles

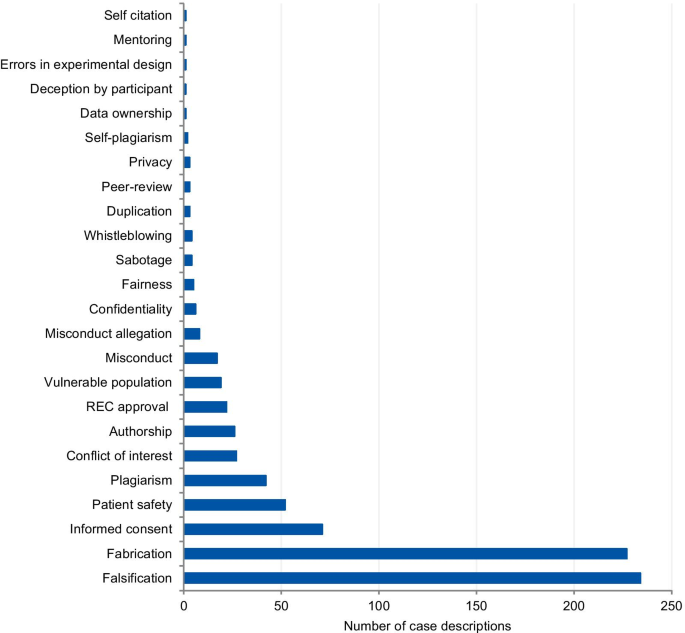

The categories used to classify the violations include those that pertain to the different kinds of scientific misconduct (falsification, fabrication, plagiarism), detrimental research practices (authorship issues, duplication, peer-review, errors in experimental design, and mentoring), and “other misconduct” (according to the definitions from the National Academies of Sciences and Medicine, [ 1 ]). Each case could involve more than one type of violation. The majority of cases presented more than one violation or ethical issue, with a mean of 1.56 violations per case. Figure 2 presents the frequency of each violation tagged to the articles. Falsification and fabrication were the most frequently tagged violations. The violations accounted respectively for 29.1% and 30.0% of the number of taggings (n = 780), and they were involved in 46.8% and 45.4% of the articles (n = 500 case descriptions). Problems with informed consent represented 9.1% of the number of taggings and 14% of the articles, followed by patient safety (6.7% and 10.4%) and plagiarism (5.4% and 8.4%). Detrimental research practices, such as authorship issues, duplication, peer-review, errors in experimental design, mentoring, and self-citation were mentioned cumulatively in 7.0% of the articles.

Tagged violations from the article analysis

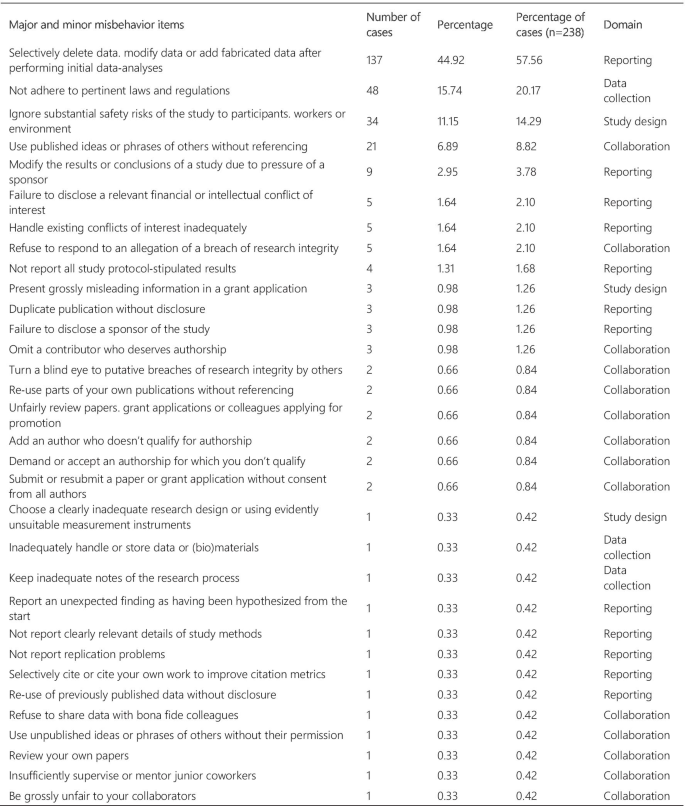

Analysis of the cases

Figure 3 presents the frequency and percentage of each violation found in the cases. Each case could include more than one item from the list. The 238 cases were tagged 305 times, with a mean of 1.28 items per case. Fabrication and falsification were the most frequently tagged violations (44.9%), involved in 57.7% of the cases (n = 238). The non-adherence to pertinent laws and regulations, such as lack of informed consent and REC approval, was the second most frequently tagged violation (15.7%) and involved in 20.2% of the cases. Patient safety issues were the third most frequently tagged violations (11.1%), involved in 14.3% of the cases, followed by plagiarism (6.9% and 8.8%). The list of major and minor misbehaviors [ 8 ] classifies the items into study design, data collection, reporting, and collaboration issues. Our results show that 56.0% of the tagged violations involved issues in reporting, 16.4% in data collection, 15.1% involved collaboration issues, and 12.5% in the study design. The items in the original list that were not listed in the results were not involved in any case collected.

Major and minor misbehavior items from the analysis of cases

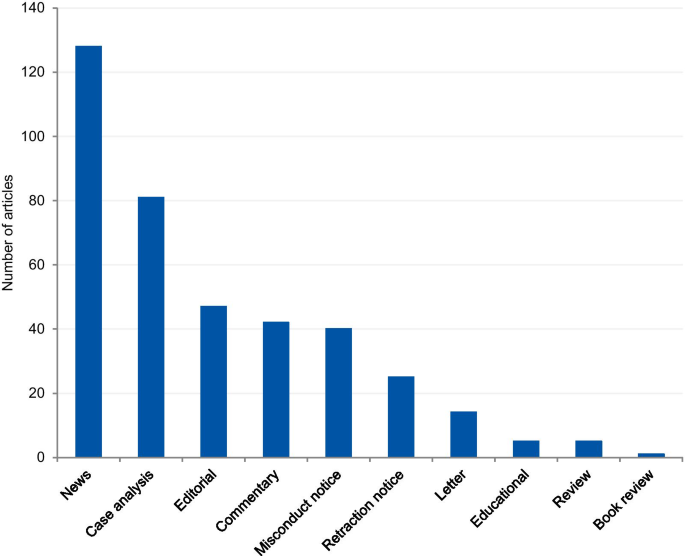

Article genre

The articles were mostly classified into “news” (33.0%), followed by “case analysis” (20.9%), “editorial” (12.1%), “commentary” (10.8%), “misconduct notice” (10.3%), “retraction notice” (6.4%), “letter” (3.6%), “educational paper” (1.3%), “review” (1%), and “book review” (0.3%) (Fig. 4 ). The articles classified into “news” and “case analysis” included predominantly prominent cases. Items classified into “news” often explored all the investigation findings step by step for the associated cases as the case progressed through investigations, and this might explain its high prevalence. The case analyses included mainly normative assessments of prominent cases. The misconduct and retraction notices included the largest number of unique cases, although a relatively large portion of the retraction and misconduct records could not be included because of insufficient case details. The articles classified into “editorial”, “commentary” and “letter” also included unique cases.

Article genre of included articles

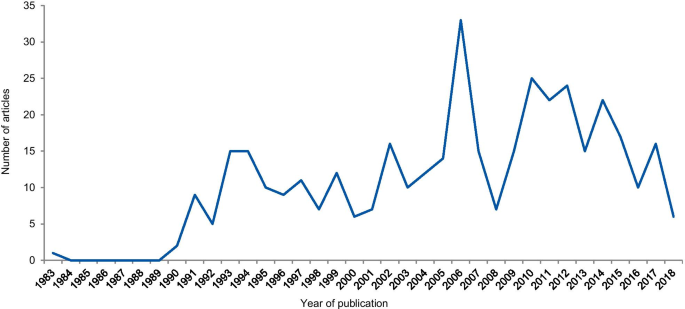

Article analysis

The dates of the eligible articles range from 1983 to 2018 with notable peaks between 1990 and 1996, most probably associated with the Gallo [ 9 ] and Imanishi-Kari cases [ 10 ], and around 2005 with the Hwang [ 11 ], Wakefield [ 12 ], and CNEP trial cases [ 13 ] (Fig. 5 ). The trend line shows an increase in the number of articles over the years.

Frequency of articles according to the year of publication

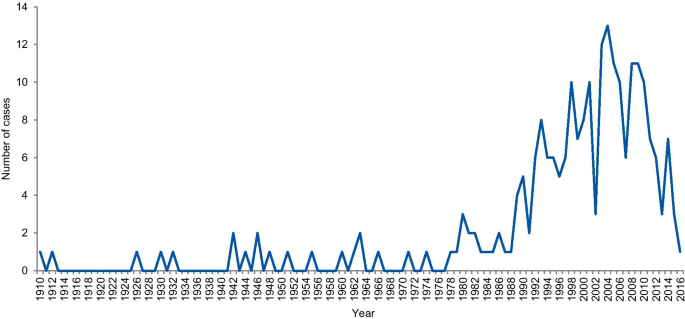

Case analysis

The dates of included cases range from 1798 to 2016. Two cases occurred before 1910, one in 1798 and the other in 1845. Figure 6 shows the number of cases per year from 1910. An increase in the curve started in the early 1980s, reaching the highest frequency in 2004 with 13 cases.

Frequency of cases per year

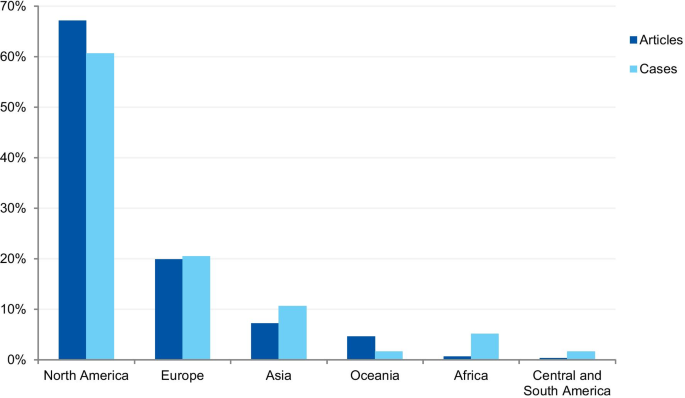

Geographical distribution

The first analysis concerned the authors’ affiliation and the corresponding author’s address. Where the article contained more than one country in the affiliation list, only the first author’s location was considered. Eighty-one articles were excluded because the authors’ affiliations were not available, and 307 articles were included in the analysis. The articles originated from 26 different countries (Additional file 3 ). Most of the articles emanated from the USA and the UK (61.9% and 14.3% of articles, respectively), followed by Canada (4.9%), Australia (3.3%), China (1.6%), Japan (1.6%), Korea (1.3%), and New Zealand (1.3%). Some of the most discussed cases occurred in the USA; the Imanishi-Kari, Gallo, and Schön cases [ 9 , 10 ]. Intensely discussed cases are also associated with Canada (Fisher/Poisson and Olivieri cases), the UK (Wakefield and CNEP trial cases), South Korea (Hwang case), and Japan (RIKEN case) [ 12 , 14 ]. In terms of percentages, North America and Europe stand out in the number of articles (Fig. 7 ).

Percentage of articles and cases by continent

The case analysis involved the location where the case took place, taking into account the institutions involved in the case. For cases involving more than one country, all the countries were considered. Three cases were excluded from the analysis due to insufficient information. In the case analysis, 40 countries were involved in 235 different cases (Additional file 4 ). Our findings show that most of the reported cases occurred in the USA and the United Kingdom (59.6% and 9.8% of cases, respectively). In addition, a number of cases occurred in Canada (6.0%), Japan (5.5%), China (2.1%), and Germany (2.1%). In terms of percentages, North America and Europe stand out in the number of cases (Fig. 7 ). To enable comparison, we have additionally collected the number of published documents according to country distribution, available on SCImago Journal & Country Rank [ 16 ]. The numbers correspond to the documents published from 1996 to 2019. The USA occupies the first place in the number of documents, with 21.9%, followed by China (11.1%), UK (6.3%), Germany (5.5%), and Japan (4.9%).

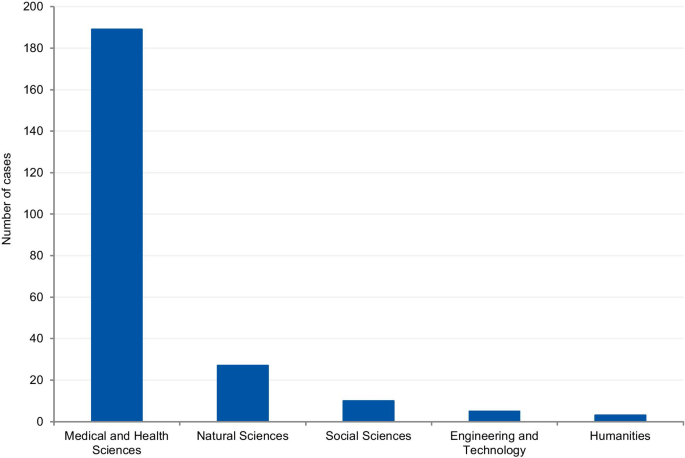

Field of science

The cases were classified according to the field of science. Four cases (1.7%) could not be classified due to insufficient information. Where information was available, 80.8% of cases were from the Medical and Health Sciences, 11.5% from the Natural Sciences, 4.3% from Social Sciences, 2.1% from Engineering and Technology, and 1.3% from Humanities (Fig. 8 ). Additionally, we have retrieved the number of published documents according to scientific field distribution, available on SCImago [ 16 ]. Of the total number of scientific publications, 41.5% are related to natural sciences, 22% to engineering, 25.1% to health and medical sciences, 7.8% to social sciences, 1.9% to agricultural sciences, and 1.7% to the humanities.

Field of science from the analysis of cases

This variable aimed to collect information on possible consequences and sanctions imposed by funding agencies, scientific journals and/or institutions. 97 cases could not be classified due to insufficient information. 141 cases were included. Each case could potentially include more than one outcome. Most of cases (45.4%) involved paper retraction, followed by exclusion from funding applications (35.5%). (Table 2 ).

RE and RI cases have been increasingly discussed publicly, affecting public attitudes towards scientists and raising awareness about ethical issues, violations, and their wider consequences [ 5 ]. Different approaches have been applied in order to quantify and address research misbehaviors [ 5 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]. However, most cases are investigated confidentially and the findings remain undisclosed even after the investigation [ 19 , 20 ]. Therefore, the study aimed to collect the RE and RI cases available in the scientific literature, understand how the cases are discussed, and identify the potential of case descriptions to raise awareness on RE and RI.

We collected and analyzed 500 detailed case descriptions from 388 articles and our results show that they mostly relate to extensively discussed and notorious cases. Approximately half of all included cases was mentioned in at least two different articles, and the top ten most commonly mentioned cases were discussed in 132 articles.

The prominence of certain cases in the literature, based on the number of duplicated cases we found (e.g. Hwang case), can be explained by the type of article in which cases are discussed and the type of violation involved in the case. In the article genre analysis, 33% of the cases were described in the news section of scientific publications. Our findings show that almost all article genres discuss those cases that are new and in vogue. Once the case appears in the public domain, it is intensely discussed in the media and by scientists, and some prominent cases have been discussed for more than 20 years (Table 1 ). Misconduct and retraction notices were exceptions in the article genre analysis, as they presented mostly unique cases. The misconduct notices were mainly found on the NIH repository, which is indexed in the searched databases. Some federal funding agencies like NIH usually publicize investigation findings associated with the research they fund. The results derived from the NIH repository also explains the large proportion of articles from the US (61.9%). However, in some cases, only a few details are provided about the case. For cases that have not received federal funding and have not been reported to federal authorities, the investigation is conducted by local institutions. In such instances, the reporting of findings depends on each institution’s policy and willingness to disclose information [ 21 ]. The other exception involves retraction notices. Despite the existence of ethical guidelines [ 22 ], there is no uniform and a common approach to how a journal should report a retraction. The Retraction Watch website suggests two lists of information that should be included in a retraction notice to satisfy the minimum and optimum requirements [ 22 , 23 ]. As well as disclosing the reason for the retraction and information regarding the retraction process, optimal notices should include: (I) the date when the journal was first alerted to potential problems; (II) details regarding institutional investigations and associated outcomes; (III) the effects on other papers published by the same authors; (IV) statements about more recent replications only if and when these have been validated by a third party; (V) details regarding the journal’s sanctions; and (VI) details regarding any lawsuits that have been filed regarding the case. The lack of transparency and information in retraction notices was also noted in studies that collected and evaluated retractions [ 24 ]. According to Resnik and Dinse [ 25 ], retractions notices related to cases of misconduct tend to avoid naming the specific violation involved in the case. This study found that only 32.8% of the notices identify the actual problem, such as fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism, and 58.8% reported the case as replication failure, loss of data, or error. Potential explanations for euphemisms and vague claims in retraction notices authored by editors could pertain to the possibility of legal actions from the authors, honest or self-reported errors, and lack of resources to conduct thorough investigations. In addition, the lack of transparency can also be explained by the conflicts of interests of the article’s author(s), since the notices are often written by the authors of the retracted article.

The analysis of violations/ethical issues shows the dominance of fabrication and falsification cases and explains the high prevalence of prominent cases. Non-adherence to laws and regulations (REC approval, informed consent, and data protection) was the second most prevalent issue, followed by patient safety, plagiarism, and conflicts of interest. The prevalence of the five most tagged violations in the case analysis was higher than the prevalence found in the analysis of articles that involved the same violations. The only exceptions are fabrication and falsification cases, which represented 45% of the tagged violations in the analysis of cases, and 59.1% in the article analysis. This disproportion shows a predilection for the publication of discussions related to fabrication and falsification when compared to other serious violations. Complex cases involving these types of violations make good headlines and this follows a custom pattern of writing about cases that catch the public and media’s attention [ 26 ]. The way cases of RE and RI violations are explored in the literature gives a sense that only a few scientists are “the bad apples” and they are usually discovered, investigated, and sanctioned accordingly. This implies that the integrity of science, in general, remains relatively untouched by these violations. However, studies on misconduct determinants show that scientific misconduct is a systemic problem, which involves not only individual factors, but structural and institutional factors as well, and that a combined effort is necessary to change this scenario [ 27 , 28 ].

Analysis of cases

A notable increase in RE and RI cases occurred in the 1990s, with a gradual increase until approximately 2006. This result is in agreement with studies that evaluated paper retractions [ 24 , 29 ]. Although our study did not focus only on retractions, the trend is similar. This increase in cases should not be attributed only to the increase in the number of publications, since studies that evaluated retractions show that the percentage of retraction due to fraud has increased almost ten times since 1975, compared to the total number of articles. Our results also show a gradual reduction in the number of cases from 2011 and a greater drop in 2015. However, this reduction should be considered cautiously because many investigations take years to complete and have their findings disclosed. ORI has shown that from 2001 to 2010 the investigation of their cases took an average of 20.48 months with a maximum investigation time of more than 9 years [ 24 ].

The countries from which most cases were reported were the USA (59.6%), the UK (9.8%), Canada (6.0%), Japan (5.5%), and China (2.1%). When analyzed by continent, the highest percentage of cases took place in North America, followed by Europe, Asia, Oceania, Latin America, and Africa. The predominance of cases from the USA is predictable, since the country publishes more scientific articles than any other country, with 21.8% of the total documents, according to SCImago [ 16 ]. However, the same interpretation does not apply to China, which occupies the second position in the ranking, with 11.2%. These differences in the geographical distribution were also found in a study that collected published research on research integrity [ 30 ]. The results found by Aubert Bonn and Pinxten (2019) show that studies in the United States accounted for more than half of the sample collected, and although China is one of the leaders in scientific publications, it represented only 0.7% of the sample. Our findings can also be explained by the search strategy that included only keywords in English. Since the majority of RE and RI cases are investigated and have their findings locally disclosed, the employment of English keywords and terms in the search strategy is a limitation. Moreover, our findings do not allow us to draw inferences regarding the incidence or prevalence of misconduct around the world. Instead, it shows where there is a culture of publicly disclosing information and openly discussing RE and RI cases in English documents.

Scientific field analysis

The results show that 80.8% of reported cases occurred in the medical and health sciences whilst only 1.3% occurred in the humanities. This disciplinary difference has also been observed in studies on research integrity climates. A study conducted by Haven and colleagues, [ 28 ] associated seven subscales of research climate with the disciplinary field. The subscales included: (1) Responsible Conduct of Research (RCR) resources, (2) regulatory quality, (3) integrity norms, (4) integrity socialization, (5) supervisor/supervisee relations, (6) (lack of) integrity inhibitors, and (7) expectations. The results, based on the seven subscale scores, show that researchers from the humanities and social sciences have the lowest perception of the RI climate. By contrast, the natural sciences expressed the highest perception of the RI climate, followed by the biomedical sciences. There are also significant differences in the depth and extent of the regulatory environments of different disciplines (e.g. the existence of laws, codes of conduct, policies, relevant ethics committees, or authorities). These findings corroborate our results, as those areas of science most familiar with RI tend to explore the subject further, and, consequently, are more likely to publish case details. Although the volume of published research in each research area also influences the number of cases, the predominance of medical and health sciences cases is not aligned with the trends regarding the volume of published research. According to SCImago Journal & Country Rank [ 16 ], natural sciences occupy the first place in the number of publications (41,5%), followed by the medical and health sciences (25,1%), engineering (22%), social sciences (7,8%), and the humanities (1,7%). Moreover, biomedical journals are overrepresented in the top scientific journals by IF ranking, and these journals usually have clear policies for research misconduct. High-impact journals are more likely to have higher visibility and scrutiny, and consequently, more likely to have been the subject of misconduct investigations. Additionally, the most well-known general medical journals, including NEJM, The Lancet, and the BMJ, employ journalists to write their news sections. Since these journals have the resources to produce extensive news sections, it is, therefore, more likely that medical cases will be discussed.

Violations analysis

In the analysis of violations, the cases were categorized into major and minor misbehaviors. Most cases involved data fabrication and falsification, followed by cases involving non-adherence to laws and regulations, patient safety, plagiarism, and conflicts of interest. When classified by categories, 12.5% of the tagged violations involved issues in the study design, 16.4% in data collection, 56.0% in reporting, and 15.1% involved collaboration issues. Approximately 80% of the tagged violations involved serious research misbehaviors, based on the ranking of research misbehaviors proposed by Bouter and colleagues. However, as demonstrated in a meta-analysis by Fanelli (2009), most self-declared cases involve questionable research practices. In the meta-analysis, 33.7% of scientists admitted questionable research practices, and 72% admitted when asked about the behavior of colleagues. This finding contrasts with an admission rate of 1.97% and 14.12% for cases involving fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism. However, Fanelli’s meta-analysis does not include data about research misbehaviors in its wider sense but focuses on behaviors that bias research results (i.e. fabrication and falsification, intentional non-publication of results, biased methodology, misleading reporting). In our study, the majority of cases involved FFP (66.4%). Overrepresentation of some types of violations, and underrepresentation of others, might lead to misguided efforts, as cases that receive intense publicity eventually influence policies relating to scientific misconduct and RI [ 20 ].

Sanctions analysis

The five most prevalent outcomes were paper retraction, followed by exclusion from funding applications, exclusion from service or position, dismissal and suspension, and paper correction. This result is similar to that found by Redman and Merz [ 31 ], who collected data from misconduct cases provided by the ORI. Moreover, their results show that fabrication and falsification cases are 8.8 times more likely than others to receive funding exclusions. Such cases also received, on average, 0.6 more sanctions per case. Punishments for misconduct remain under discussion, ranging from the criminalization of more serious forms of misconduct [ 32 ] to social punishments, such as those recently introduced by China [ 33 ]. The most common sanction identified by our analysis—paper retraction—is consistent with the most prevalent types of violation, that is, falsification and fabrication.

Publicizing scientific misconduct

The lack of publicly available summaries of misconduct investigations makes it difficult to share experiences and evaluate the effectiveness of policies and training programs. Publicizing scientific misconduct can have serious consequences and creates a stigma around those involved in the case. For instance, publicized allegations can damage the reputation of the accused even when they are later exonerated [ 21 ]. Thus, for published cases, it is the responsibility of the authors and editors to determine whether the name(s) of those involved should be disclosed. On the one hand, it is envisaged that disclosing the name(s) of those involved will encourage others in the community to foster good standards. On the other hand, it is suggested that someone who has made a mistake should have the right to a chance to defend his/her reputation. Regardless of whether a person's name is left out or disclosed, case reports have an important educational function and can help guide RE- and RI-related policies [ 34 ]. A recent paper published by Gunsalus [ 35 ] proposes a three-part approach to strengthen transparency in misconduct investigations. The first part consists of a checklist [ 36 ]. The second suggests that an external peer reviewer should be involved in investigative reporting. The third part calls for the publication of the peer reviewer’s findings.

Limitations

One of the possible limitations of our study may be our search strategy. Although we have conducted pilot searches and sensitivity tests to reach the most feasible and precise search strategy, we cannot exclude the possibility of having missed important cases. Furthermore, the use of English keywords was another limitation of our search. Since most investigations are performed locally and published in local repositories, our search only allowed us to access cases from English-speaking countries or discussed in academic publications written in English. Additionally, it is important to note that the published cases are not representative of all instances of misconduct, since most of them are never discovered, and when discovered, not all are fully investigated or have their findings published. It is also important to note that the lack of information from the extracted case descriptions is a limitation that affects the interpretation of our results. In our review, only 25 retraction notices contained sufficient information that allowed us to include them in our analysis in conformance with the inclusion criteria. Although our search strategy was not focused specifically on retraction and misconduct notices, we believe that if sufficiently detailed information was available in such notices, the search strategy would have identified them.

Case descriptions found in academic journals are dominated by discussions regarding prominent cases and are mainly published in the news section of journals. Our results show that there is an overrepresentation of biomedical research cases over other scientific fields when compared with the volume of publications produced by each field. Moreover, published cases mostly involve fabrication, falsification, and patient safety issues. This finding could have a significant impact on the academic representation of ethical issues for RE and RI. The predominance of fabrication and falsification cases might diverge the attention of the academic community from relevant but less visible violations and ethical issues, and recently emerging forms of misbehaviors.

Availability of data and materials

This review has been developed by members of the EnTIRE project in order to generate information on the cases that will be made available on the Embassy of Good Science platform ( www.embassy.science ). The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) repository in https://osf.io/3xatj/?view_only=313a0477ab554b7489ee52d3046398b9 .

National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine. Fostering integrity in research. National Academies Press; 2017.

Davis MS, Riske-Morris M, Diaz SR. Causal factors implicated in research misconduct: evidence from ORI case files. Sci Eng Ethics. 2007;13(4):395–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-007-9045-2 .

Article Google Scholar

Ampollini I, Bucchi M. When public discourse mirrors academic debate: research integrity in the media. Sci Eng Ethics. 2020;26(1):451–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-019-00103-5 .

Hesselmann F, Graf V, Schmidt M, Reinhart M. The visibility of scientific misconduct: a review of the literature on retracted journal articles. Curr Sociol La Sociologie contemporaine. 2017;65(6):814–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392116663807 .

Martinson BC, Anderson MS, de Vries R. Scientists behaving badly. Nature. 2005;435(7043):737–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/435737a .

Loikith L, Bauchwitz R. The essential need for research misconduct allegation audits. Sci Eng Ethics. 2016;22(4):1027–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-016-9798-6 .

OECD. Revised field of science and technology (FoS) classification in the Frascati manual. Working Party of National Experts on Science and Technology Indicators 2007. p. 1–12.

Bouter LM, Tijdink J, Axelsen N, Martinson BC, ter Riet G. Ranking major and minor research misbehaviors: results from a survey among participants of four World Conferences on Research Integrity. Res Integrity Peer Rev. 2016;1(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-016-0024-5 .

Greenberg DS. Resounding echoes of Gallo case. Lancet. 1995;345(8950):639.

Dresser R. Giving scientists their due. The Imanishi-Kari decision. Hastings Center Rep. 1997;27(3):26–8.

Hong ST. We should not forget lessons learned from the Woo Suk Hwang’s case of research misconduct and bioethics law violation. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31(11):1671–2. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2016.31.11.1671 .

Opel DJ, Diekema DS, Marcuse EK. Assuring research integrity in the wake of Wakefield. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2011;342(7790):179. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d2 .

Wells F. The Stoke CNEP Saga: did it need to take so long? J R Soc Med. 2010;103(9):352–6. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2010.10k010 .

Normile D. RIKEN panel finds misconduct in controversial paper. Science. 2014;344(6179):23. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.344.6179.23 .

Wager E. The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE): Objectives and achievements 1997–2012. La Presse Médicale. 2012;41(9):861–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lpm.2012.02.049 .

SCImago nd. SJR — SCImago Journal & Country Rank [Portal]. http://www.scimagojr.com . Accessed 03 Feb 2021.

Fanelli D. How many scientists fabricate and falsify research? A systematic review and meta-analysis of survey data. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(5):e5738. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005738 .

Steneck NH. Fostering integrity in research: definitions, current knowledge, and future directions. Sci Eng Ethics. 2006;12(1):53–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00022268 .

DuBois JM, Anderson EE, Chibnall J, Carroll K, Gibb T, Ogbuka C, et al. Understanding research misconduct: a comparative analysis of 120 cases of professional wrongdoing. Account Res. 2013;20(5–6):320–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2013.822248 .

National Academy of Sciences NAoE, Institute of Medicine Panel on Scientific R, the Conduct of R. Responsible Science: Ensuring the Integrity of the Research Process: Volume I. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) Copyright (c) 1992 by the National Academy of Sciences; 1992.

Bauchner H, Fontanarosa PB, Flanagin A, Thornton J. Scientific misconduct and medical journals. JAMA. 2018;320(19):1985–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.14350 .

COPE Council. COPE Guidelines: Retraction Guidelines. 2019. https://doi.org/10.24318/cope.2019.1.4 .

Retraction Watch. What should an ideal retraction notice look like? 2015, May 21. https://retractionwatch.com/2015/05/21/what-should-an-ideal-retraction-notice-look-like/ .

Fang FC, Steen RG, Casadevall A. Misconduct accounts for the majority of retracted scientific publications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(42):17028–33. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1212247109 .

Resnik DB, Dinse GE. Scientific retractions and corrections related to misconduct findings. J Med Ethics. 2013;39(1):46–50. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2012-100766 .

de Vries R, Anderson MS, Martinson BC. Normal misbehavior: scientists talk about the ethics of research. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics JERHRE. 2006;1(1):43–50. https://doi.org/10.1525/jer.2006.1.1.43 .

Sovacool BK. Exploring scientific misconduct: isolated individuals, impure institutions, or an inevitable idiom of modern science? J Bioethical Inquiry. 2008;5(4):271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-008-9113-6 .

Haven TL, Tijdink JK, Martinson BC, Bouter LM. Perceptions of research integrity climate differ between academic ranks and disciplinary fields: results from a survey among academic researchers in Amsterdam. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(1):e0210599. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210599 .

Trikalinos NA, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JPA. Falsified papers in high-impact journals were slow to retract and indistinguishable from nonfraudulent papers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(5):464–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.019 .

Aubert Bonn N, Pinxten W. A decade of empirical research on research integrity: What have we (not) looked at? J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2019;14(4):338–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1556264619858534 .

Redman BK, Merz JF. Scientific misconduct: do the punishments fit the crime? Science. 2008;321(5890):775. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1158052 .

Bülow W, Helgesson G. Criminalization of scientific misconduct. Med Health Care Philos. 2019;22(2):245–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-018-9865-7 .

Cyranoski D. China introduces “social” punishments for scientific misconduct. Nature. 2018;564(7736):312. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-07740-z .

Bird SJ. Publicizing scientific misconduct and its consequences. Sci Eng Ethics. 2004;10(3):435–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-004-0001-0 .

Gunsalus CK. Make reports of research misconduct public. Nature. 2019;570(7759):7. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-01728-z .

Gunsalus CK, Marcus AR, Oransky I. Institutional research misconduct reports need more credibility. JAMA. 2018;319(13):1315–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.0358 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the EnTIRE research group. The EnTIRE project (Mapping Normative Frameworks for Ethics and Integrity of Research) aims to create an online platform that makes RE+RI information easily accessible to the research community. The EnTIRE Consortium is composed by VU Medical Center, Amsterdam, gesinn. It Gmbh & Co Kg, KU Leuven, University of Split School of Medicine, Dublin City University, Central European University, University of Oslo, University of Manchester, European Network of Research Ethics Committees.

EnTIRE project (Mapping Normative Frameworks for Ethics and Integrity of Research) has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement N 741782. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Behavioural Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Debrecen, Móricz Zsigmond krt. 22. III. Apartman Diákszálló, Debrecen, 4032, Hungary

Anna Catharina Vieira Armond & János Kristóf Bodnár

Institute of Ethics, School of Theology, Philosophy and Music, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland

Bert Gordijn, Jonathan Lewis & Mohammad Hosseini

Centre for Social Ethics and Policy, School of Law, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

Center for Medical Ethics, HELSAM, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Center for Ethics and Law in Biomedicine, Central European University, Budapest, Hungary

Péter Kakuk

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors (ACVA, BG, JL, MH, JKB, SH and PK) developed the idea for the article. ACVA, PK, JKB performed the literature search and data analysis, ACVA and PK produced the draft, and all authors critically revised it. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Anna Catharina Vieira Armond .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

. Pilot search and search strategy.

Additional file 2

. List of Major and minor misbehavior items (Developed by Bouter LM, Tijdink J, Axelsen N, Martinson BC, ter Riet G. Ranking major and minor research misbehaviors: results from a survey among participants of four World Conferences on Research Integrity. Research integrity and peer review. 2016;1(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-016-0024-5 ).

Additional file 3

. Table containing the number and percentage of countries included in the analysis of articles.

Additional file 4

. Table containing the number and percentage of countries included in the analysis of the cases.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Armond, A.C.V., Gordijn, B., Lewis, J. et al. A scoping review of the literature featuring research ethics and research integrity cases. BMC Med Ethics 22 , 50 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-021-00620-8

Download citation

Received : 06 October 2020

Accepted : 21 April 2021

Published : 30 April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-021-00620-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Research ethics

- Research integrity

- Scientific misconduct

BMC Medical Ethics

ISSN: 1472-6939

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 23 August 2022

Deceiving scientific research, misconduct events are possibly a more common practice than foreseen

- Alonzo Alfaro-Núñez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4050-5041 1 , 2

Environmental Sciences Europe volume 34 , Article number: 76 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

4109 Accesses

1 Citations

24 Altmetric

Metrics details

Today, scientists and academic researchers experience an enormous pressure to publish innovative and ground-breaking results in prestigious journals. This pressure may blight the general view concept of how scientific research needs to be done in terms of the general rules of transparency; duplication of data, and co-authorship rights might be compromised. As such, misconduct acts may occur more frequently than foreseen, as frequently these experiences are not openly shared or discussed among researchers.

While there are some concerns about the health and the transparency implications of such normalised pressure practices imposed on researchers in scientific research, there is a general acceptance that researchers must take and accept it in order to survive in the competitive world of science. This is even more the case for junior and mid-senior researchers who have recently started their adventure into the universe of independent researchers. Only the slightest fraction manages to endure, after many years of furious and cruel rivalry, to obtain a long-term, and even less probable, permanent position. There is an evil circle; excellent records of good publications are needed in order to obtain research funding, but how to produce pioneering research during these first years without funding? Many may argue this is a necessary process to ensure good quality scientific investigation, possibly, but perseverance and resilience may not be the only values needed when rejection is received consecutively for years.

There is a general culture that scientists rarely share previous bad experiences, in particular if they were associated to misconduct, as they may not be seen or considered as a relevant or hot topic to the scientific community readers. On next, a recent misconduct experience is shared, and a few additional reflections and suggestions on this topic were drafted in the hope other researchers might be spared unnecessary and unpleasant times.

Scientists are under great pressure to publish not only high-quality research, but also a larger number of publications, the more the merrier, within the first years of career in order to survive in the competitive world of science. This pressure might mislead young less experienced researchers to take “shortcuts” that may consequently mislead to carry out misconduct actions. The aim of this article is not just trying to report a case of misconduct to the concerned stakeholders, but also to the research community as a whole in the hope other researchers might avoid similar experiences. Moreover, some basic recommendations are shared to remind the basic rules of transparency, duplication of data and authorship rights to avoid and prevent misconduct acts based on existing literature and the present experience.

Welcoming collaboration

During the first months of 2021, already in the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic with most European research institutes and labs still in lockdown [ 1 ], and all over the world, I received an email from a young researcher overseas. This young fellow is based in Bangladesh, South Asia, in a country in which I have never collaborated before. He was interested in a potential collaboration with many ideas, and proved to be a very energetic person writing me on a daily basis and even several times a day during the first weeks.

There were obviously some suspicions about the nature of this collaboration, but the general and basic background check out was done, and this fellow seemed to be legitimate. Thus, after a few weeks of discussing back and forth research ideas, I welcomed the collaboration. Thereafter, for the first few months many ideas were elaborated and discussed, and so we began to draft two review manuscripts simultaneously. In no time, it felt like a potential and long-standing collaboration was born. However, it also required additional time because of the linguistic and cultural barrier. It appeared that sometimes the main message was getting lost in translation, and it was reflected in the text on the various manuscript versions. We repetitively argued about the importance of transparency, the correct use of data previously published and the general rules of authorship and citation, especially when producing a new review document. Nevertheless, these errors were corrected and he guaranteed to have full understanding, and I trusted.

After some time, enthusiasm started to decline and the highly motivated collaborator started to rush to complete the work regardless of the quality, especially as a third manuscript was now also in play. I was not willing to sacrifice quality, so I started using more of my personal time to complete the different manuscripts, I felt committed. After six months or so, the first of the three manuscripts was ready, and the process of submission started to a high-impact peer-review journal to a special issue on a topic where I had been invited months ago. A few months later, the second manuscript followed the same steps.

By the middle of April 2022, the first of the manuscripts had just been accepted; the second one was already in its second round of review, and the third and last of the manuscripts was ready for submission. I cannot deny the satisfaction felt of a good job properly done in a time record (for my personal standards).

Deceptive surprise

Through the last hours, before submitting our final manuscript, the mandatory final inspection was done. However, I noticed something odd, two new citations had been added in the last minute, and I did not approve that change. Even more curious, the two citations had the new collaborator’s name on it. Immediately, I searched for the two mysterious documents, a book chapter and another peer-reviewed publication were the result. To my surprise, the titles of these two new works were very similar and somehow nearly identical to the topic we had just finished and his name appeared as the first author. Both documents were not open access and had recently been published, one of them less than a week old. Furthermore, our manuscript, the same document I was supposed to submit that same day, had six figures and four tables, all generated by our collaborative work. The book chapter had exactly the same figures and tables just in a different order, but the data and content were nearly identical. The text redaction was different, and there were also some other co-authors from his same region, but the content and background idea was the same.

During the next hours, I went back to the other two manuscripts. Indeed, all my fears were right. My new collaborator had systematically been committing fraud, replicating manuscripts using the same data and publishing by himself using my very ideas and sentences.

I confronted him; I wanted to receive an explanation, a reason for these actions. I copied all other co-authors in these communications. The three manuscripts had built international collaboration, and other parties had actively participated, and now we all were compromised. The first reaction received was that he was not aware that was an illegal action, and then, silence. No satisfactory answer was ever received, and more importantly, it seemed some of the other co-authors did not care, nor were surprised.

The aftermath of deception

In the next coming days, I redacted several email letters describing the misconduct situation to the different journal’s editors, preprint services and especially to the main affiliations of this fraudulent person. The two manuscripts were withdrawn from the respective journals right away. Together with the third manuscript, none of the documents will ever be published. There is a long history and documentation showing that withdraws and retractions of scientific manuscripts may be the most relevant form of silently reporting scientific misconduct [ 2 , 3 ], and now I was part of it. Editors from the journals and editorial houses where the duplicated documents had been published responded to investigate the case. However, after several months of waiting, and despite the multiple complain letters providing all the evidence to prove the misconduct act, no official sanctions have been taken by any of the journals and the documents remain still available online. Editors have the responsibility to pursue scientific misconduct in submitted or published manuscripts; however, editors are not responsible for conducting investigation or deciding whether a scientific misconduct occurred [ 4 ].

The preprint services response was very clear and conclusive, regardless of the evidence provided, the documents published online in their preprint format cannot and will not be removed. Now our names will remain associated with this person to posterity, another wonderful discovery. Release of early results in the format of preprints without going through the process of peer-review is an old well known issue of concern [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. For the last few years I have been in favour and accepting the early release of preprint publications, this new experience has made me reconsider and change entirely this position. I find unacceptable that in spite of providing all evidence of research misconduct, fraud and duplication of data especially, a retraction of a preprint document is not possible for most preprint services available.

As for the consequences or sanctions imposed on this “researcher” by his own affiliate institutions, it also remains unknown as no reply or answer has been received until now. Additionally, some of his personal collaborators also included as co-authors during the editing process of the manuscripts, as it was claimed they “intellectually contributed” to the study, contacted me during the first weeks after withdrawing. These collaborators were unhappy about the decision taken, and complained asking: ‘‘ what is it really necessary to retract the documents entirely, in particular one manuscript already accepted and a second one in-review? Why was not this decision put into a vote among the co-authors?” They did not considered to be an enough reason for withdrawing and claimed, “ It had been a rush and wrong decision” . The answer was simple, it was a clear research misconduct act and the data has been duplicated and misused, my decision could not be clouded by the grief of losing three publications. Besides, I was the last author and corresponding author for all three manuscripts, and thus, the responsibility and final decision relied on me. Furthermore, and as a curious additional detail, all editors associated to the journals where the two-duplicated manuscripts were published, all are as well from the same region as this person. All these facts together allow me to reach the conclusion that misconduct practices may be relatively more common in some other parts of the world, and the research culture may play an important role in this type of practices, but we are still afraid to discuss about it [ 8 ]. There are no rigorous or systematic controls to regulate that one unique person can manipulate, duplicate with slight modifications in the text, and publish the same datasets in different journals, especially if the time between submissions is minimal. There are thousands of journals with many more thousands of editors in an infinite number of online platforms. Decisions over whether to retract or modify a study are more likely to take years than months, this time could potentially harmfully misinform [ 9 ] and damage the reputation of researchers [ 3 ] if any sanction is taken at all by the end [ 10 ]. Based on the previous rationale, this author who duplicated our work and published by himself may simply get away with it, two fraudulent copy/paste extra publications and zero consequences.

Hundreds of hour’s work and nearly a year of effort were lost in an instant. As many others, I believe I work and interact with researchers sharing similar values of honesty, openness and accountability pursuing to establish as an independent researcher to produce good science work. Yet every aspect of science, from the framing of a research idea to the publication of a manuscript, is susceptible to influences that can lead to misconduct [ 11 ]. By withdrawing at once three manuscripts, now associated to misconduct practices, my research colleagues and I will suffer the consequences of the current academia culture of “publish or perish” [ 12 ].

Recommendations to avoid unpleasant research events

With two official retractions across the editorial offices of two major journals and three preprint documents that I cannot rig out, all associated to fraud and scientific misconduct; I am probably the less qualified person with the least authority to provide any feedback and even less, a short list of recommendations to prevent misconduct in research. Nevertheless, here I am. There are many general guidelines and basic rules to prevent, avoid and report misconduct actions [ 3 , 13 , 14 , 15 ], the interested readers can get more information below in the reference list if they want to explore deeper into this. Using these guidelines as the main backbone, a short list of three main recommendations is presented in the lines below.

The first and possibly most important recommendation, despite the previous shared experience; always welcome collaboration after a well-throughout background check. This may sound contradictory, but contemporary science is based on collaboration and the interdisciplinary combination of fields [ 16 ], one bad experience and one “rotten apple” cannot disrupt the development of scientific research. Of course, it is mandatory to be vigilant and to carefully investigate the background interests [ 9 ] and history of each new door that opens along the way. Welcome collaboration cautiously.

A second recommendation, to investigate the institution and location of the new coming collaborations. As stated above, the cultural background [ 8 ], and thus, the location of these new collaboration institutions may play a very important role in the final outcome. Most countries across Europe and in the U.S. have well-defined guidelines [ 3 , 10 ], which varied a lot about each principle and at the end are regulated by each institution research policies. However, there may be regions across the world where policies and regulations concerning misconduct actions and the implications and consequences are yet not well established [ 17 ]. Avoid those.

My third recommendation, and possibly the most relevant of all, do not take for granted that the other researchers are fully aware that some actions may lead to misconduct. My biggest mistake was to believe that other researchers knew or cared about the basic rules of duplication of data, transparency and respect of authorship rights. Ignorance still accounts for a large portion of the research misconduct actions [ 11 , 18 ]. Never assume that others know and respect the broad spectrum of misconduct actions.

Two additional personal recommendations. Stay away from review manuscripts and book chapters, avoid them at all cost. Consider very carefully sharing your manuscript results in the format of an early release preprint online publication.

Conclusions

There is so much to modify in the existing science research environment to avoid situations like this to continue or ever happen again. Young scientists need to be inspired and motivated to produce by example based on principles of integrity, ethical values, transparency and respect, and not by current trend of rejection and extreme pressure. Dealing with the research pressure to secure external funds and to publish in top-tier journals stand as the most common stressors that contribute to research misconduct [ 15 , 19 ]. The same research culture that creates this pressure for publishing and obtaining funds, it also contributes to the behaviour practice of silence that leads to ignore and avoid the topic of misconduct in research. While there is a general concern and scientific journals attempt to take situations like this seriously, there should also be a more open space to share and inform junior and even senior researchers about this kind of predatory stealing research practices.

Manipulation and duplication of data to inflate academic records is a desperate and shameless act, and it truly represents scientific misconduct and fraud. Unfortunately, there is a general trend with an increase in misconduct in research [ 13 ], which ultimately account for the majority of withdrawals in modern scientific publications [ 20 ]. I would like to believe that even good people could do bad things when extreme pressure is received. Nevertheless, would this justify misconduct and fraud? Never!

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Engzell P, Frey A, Verhagen MD (2021) Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic | PNAS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2022376118

Article Google Scholar

Lafollette MC (2000) The evolution of the “scientific misconduct” issue: an historical overview (44535C). Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. https://doi.org/10.1177/153537020022400405

Hesselmann F, Graf V, Schmidt M, Reinhart M (2017) The visibility of scientific misconduct: a review of the literature on retracted journal articles. Curr Sociol 65:814–845. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392116663807

Integrity OOR (2000) Managing allegations of scientific misconduct: a guidance document for editors. J Child Neurol 15:609–613. https://doi.org/10.1177/088307380001500907

Teixeira da Silva JA (2018) The preprint debate: What are the issues? Med J Armed Forces India 74:162–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mjafi.2017.08.002

King A (2020) Fast news or fake news? EMBO Rep 21:e50817. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.202050817

Article CAS Google Scholar

Moore CA (1965) Preprints an old information device with new outlooks. J Chem Docu. https://doi.org/10.1021/c160018a003

Davis MS (2010) The role of culture in research misconduct. Account Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/714906092

Grey A, Bolland MJ, Avenell A et al (2020) Check for publication integrity before misconduct. Nature 577:167–169. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-03959-6

Resnik DB, Rasmussen LM, Kissling GE (2014) An international study of research misconduct policies. Account Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2014.958218

Gunsalus CK, Robinson AD (2018) Nine pitfalls of research misconduct. Nature 557:297–299. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-05145-6

Fanelli D (2010) Do pressures to publish increase scientists’ bias? An empirical support from us states data. PLoS ONE 5:e10271. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010271

Buela-Casal G (2014) Pathological publishing: a new psychological disorder with legal consequences? Eur J Psychol Appl Leg Context. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpal.2014.06.005

Shaw DM, Erren TC (2015) Ten simple rules for protecting research integrity. PLOS Comput Biol 11:e1004388. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004388

Holtfreter K, Reisig MD, Pratt TC, Mays RD (2019) The perceived causes of research misconduct among faculty members in the natural, social, and applied sciences. Stud High Educ. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1593352

Andersen H (2016) Collaboration, interdisciplinarity, and the epistemology of contemporary science. Stud Hist Philos Sci Part A 56:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsa.2015.10.006

Khadilkar SS (2018) Scientific misconduct: a global concern. J Obstet Gynecol India 68:331–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-018-1175-8

Fernández Pinto M (2018) Scientific ignorance: probing the limits of scientific research and knowledge production. Theoria: an international journal for theory. Hist Found Sci 34:195–211

Google Scholar

DuBois JM, Anderson EE, Chibnall J et al (2013) Understanding research misconduct: a comparative analysis of 120 cases of professional wrongdoing. Account Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2013.822248

Fang FC, Steen RG, Casadevall A (2012) Misconduct accounts for the majority of retracted scientific publications | PNAS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1212247109

Download references

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Esther Agnete Jensen, Therese Kronevald, Stina Christensen, Aksel Skovgaard, Morten Juel, Jesper Clausager Madsen and Alonso A. Aguirre for their support and advice. The author would also like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their comments, feedback and improvements.

This research received support from the Department of Clinical Biochemistry at Naestved Hospital, Region Sjaelland.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Naestved Hospital, Ringstedgade 57a, 4700, Naestved, Denmark

Alonzo Alfaro-Núñez

Section for Evolutionary Genomics, GLOBE Institute, University of Copenhagen, Øster Farimagsgade 5, 1353, Copenhagen K, Denmark

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Web of Science Researcher ID H-2972-2019.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Alonzo Alfaro-Núñez .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication.

The author gives full consent for publication.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Alfaro-Núñez, A. Deceiving scientific research, misconduct events are possibly a more common practice than foreseen. Environ Sci Eur 34 , 76 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-022-00659-3

Download citation

Received : 26 April 2022

Accepted : 17 July 2022

Published : 23 August 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-022-00659-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Ethical values

- Transparency

- Scientific fraud

- Research misconduct and respect

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Research misconduct in health and life sciences research: A systematic review of retracted literature from Brazilian institutions

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Nursing, College of Health Sciences, University of Brasilia, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil

Roles Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Statistics, Telecomunicações do Brasil – Telebrás, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil

Contributed equally to this work with: Fábio Zicker, Maria Rita Carvalho Garbi Novaes, César Messias de Oliveira

Roles Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Center for Technological Development in Health, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil

Affiliation Department of Nursing, College of Health Sciences, Health Sciences Education and Research Foundation – ESCS/Fepecs, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil

Affiliation Department of Epidemiology & Public Health, Institute of Epidemiology & Health Care, University College London, London, United Kingdom

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

- Rafaelly Stavale,

- Graziani Izidoro Ferreira,

- João Antônio Martins Galvão,

- Fábio Zicker,

- Maria Rita Carvalho Garbi Novaes,

- César Messias de Oliveira,

- Dirce Guilhem

- Published: April 15, 2019

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214272

- Reader Comments

Measures to ensure research integrity have been widely discussed due to the social, economic and scientific impact of research integrity. In the past few years, financial support for health research in emerging countries has steadily increased, resulting in a growing number of scientific publications. These achievements, however, have been accompanied by a rise in retracted publications followed by concerns about the quality and reliability of such publications.

This systematic review aimed to investigate the profile of medical and life sciences research retractions from authors affiliated with Brazilian academic institutions. The chronological trend between publication and retraction date, reasons for the retraction, citation of the article after the retraction, study design, and the number of retracted publications by author and affiliation were assessed. Additionally, the quality, availability and accessibility of data regarding retracted papers from the publishers are described.

Two independent reviewers searched for articles that had been retracted since 2004 via PubMed, Web of Science, Biblioteca Virtual em Saúde (BVS) and Google Scholar databases. Indexed keywords from Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and Descritores em Ciências da Saúde (DeCS) in Portuguese, English or Spanish were used. Data were also collected from the Retraction Watch website ( www.retractionwatch.com ). This study was registered with the PROSPERO systematic review database (CRD42017071647).

A final sample of 65 articles was retrieved from 55 different journals with reported impact factors ranging from 0 to 32.86, with a median value of 4.40 and a mean of 4.69. The types of documents found were erratum (1), retracted articles (3), retracted articles with a retraction notice (5), retraction notices with erratum (3), and retraction notices (45). The assessment of the Retraction Watch website added 8 articles that were not identified by the search strategy using the bibliographic databases. The retracted publications covered a wide range of study designs. Experimental studies (40) and literature reviews (15) accounted for 84.6% of the retracted articles. Within the field of health and life sciences, medical science was the field with the largest number of retractions (34), followed by biological sciences (17). Some articles were retracted for at least two distinct reasons (13). Among the retrieved articles, plagiarism was the main reason for retraction (60%). Missing data were found in 57% of the retraction notices, which was a limitation to this review. In addition, 63% of the articles were cited after their retraction.

Publications are not retracted solely for research misconduct but also for honest error. Nevertheless, considering authors affiliated with Brazilian institutions, this review concluded that most of the retracted health and life sciences publications were retracted due to research misconduct. Because the number of publications is the most valued indicator of scientific productivity for funding and career progression purposes, a systematic effort from the national research councils, funding agencies, universities and scientific journals is needed to avoid an escalating trend of research misconduct. More investigations are needed to comprehend the underlying factors of research misconduct and its increasing manifestation.

Citation: Stavale R, Ferreira GI, Galvão JAM, Zicker F, Novaes MRCG, Oliveira CMd, et al. (2019) Research misconduct in health and life sciences research: A systematic review of retracted literature from Brazilian institutions. PLoS ONE 14(4): e0214272. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214272

Editor: Angeliki Kerasidou, University of Oxford, UNITED KINGDOM

Received: June 22, 2018; Accepted: March 11, 2019; Published: April 15, 2019