- All topics A-Z

- Grammar

- Vocabulary

- Speaking

- Reading

- Listening

- Writing

- Pronunciation

- Virtual Classroom

- Worksheets by season

- 600 Creative Writing Prompts

- Warmers, fillers & ice-breakers

- Coloring pages to print

- Flashcards

- Classroom management worksheets

- Emergency worksheets

- Revision worksheets

- Resources we recommend

- Copyright 2007-2021 пїЅ

- Submit a worksheet

- Mobile version

Essay Writing: A complete guide for students and teachers

P LANNING, PARAGRAPHING AND POLISHING: FINE-TUNING THE PERFECT ESSAY

Essay writing is an essential skill for every student. Whether writing a particular academic essay (such as persuasive, narrative, descriptive, or expository) or a timed exam essay, the key to getting good at writing is to write. Creating opportunities for our students to engage in extended writing activities will go a long way to helping them improve their skills as scribes.

But, putting the hours in alone will not be enough to attain the highest levels in essay writing. Practice must be meaningful. Once students have a broad overview of how to structure the various types of essays, they are ready to narrow in on the minor details that will enable them to fine-tune their work as a lean vehicle of their thoughts and ideas.

In this article, we will drill down to some aspects that will assist students in taking their essay writing skills up a notch. Many ideas and activities can be integrated into broader lesson plans based on essay writing. Often, though, they will work effectively in isolation – just as athletes isolate physical movements to drill that are relevant to their sport. When these movements become second nature, they can be repeated naturally in the context of the game or in our case, the writing of the essay.

THE ULTIMATE NONFICTION WRITING TEACHING RESOURCE

- 270 pages of the most effective teaching strategies

- 50+ digital tools ready right out of the box

- 75 editable resources for student differentiation

- Loads of tricks and tips to add to your teaching tool bag

- All explanations are reinforced with concrete examples.

- Links to high-quality video tutorials

- Clear objectives easy to match to the demands of your curriculum

Planning an essay

The Boys Scouts’ motto is famously ‘Be Prepared’. It’s a solid motto that can be applied to most aspects of life; essay writing is no different. Given the purpose of an essay is generally to present a logical and reasoned argument, investing time in organising arguments, ideas, and structure would seem to be time well spent.

Given that essays can take a wide range of forms and that we all have our own individual approaches to writing, it stands to reason that there will be no single best approach to the planning stage of essay writing. That said, there are several helpful hints and techniques we can share with our students to help them wrestle their ideas into a writable form. Let’s take a look at a few of the best of these:

BREAK THE QUESTION DOWN: UNDERSTAND YOUR ESSAY TOPIC.

Whether students are tackling an assignment that you have set for them in class or responding to an essay prompt in an exam situation, they should get into the habit of analyzing the nature of the task. To do this, they should unravel the question’s meaning or prompt. Students can practice this in class by responding to various essay titles, questions, and prompts, thereby gaining valuable experience breaking these down.

Have students work in groups to underline and dissect the keywords and phrases and discuss what exactly is being asked of them in the task. Are they being asked to discuss, describe, persuade, or explain? Understanding the exact nature of the task is crucial before going any further in the planning process, never mind the writing process .

BRAINSTORM AND MIND MAP WHAT YOU KNOW:

Once students have understood what the essay task asks them, they should consider what they know about the topic and, often, how they feel about it. When teaching essay writing, we so often emphasize that it is about expressing our opinions on things, but for our younger students what they think about something isn’t always obvious, even to themselves.

Brainstorming and mind-mapping what they know about a topic offers them an opportunity to uncover not just what they already know about a topic, but also gives them a chance to reveal to themselves what they think about the topic. This will help guide them in structuring their research and, later, the essay they will write . When writing an essay in an exam context, this may be the only ‘research’ the student can undertake before the writing, so practicing this will be even more important.

RESEARCH YOUR ESSAY

The previous step above should reveal to students the general direction their research will take. With the ubiquitousness of the internet, gone are the days of students relying on a single well-thumbed encyclopaedia from the school library as their sole authoritative source in their essay. If anything, the real problem for our students today is narrowing down their sources to a manageable number. Students should use the information from the previous step to help here. At this stage, it is important that they:

● Ensure the research material is directly relevant to the essay task

● Record in detail the sources of the information that they will use in their essay

● Engage with the material personally by asking questions and challenging their own biases

● Identify the key points that will be made in their essay

● Group ideas, counterarguments, and opinions together

● Identify the overarching argument they will make in their own essay.

Once these stages have been completed the student is ready to organise their points into a logical order.

WRITING YOUR ESSAY

There are a number of ways for students to organize their points in preparation for writing. They can use graphic organizers , post-it notes, or any number of available writing apps. The important thing for them to consider here is that their points should follow a logical progression. This progression of their argument will be expressed in the form of body paragraphs that will inform the structure of their finished essay.

The number of paragraphs contained in an essay will depend on a number of factors such as word limits, time limits, the complexity of the question etc. Regardless of the essay’s length, students should ensure their essay follows the Rule of Three in that every essay they write contains an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

Generally speaking, essay paragraphs will focus on one main idea that is usually expressed in a topic sentence that is followed by a series of supporting sentences that bolster that main idea. The first and final sentences are of the most significance here with the first sentence of a paragraph making the point to the reader and the final sentence of the paragraph making the overall relevance to the essay’s argument crystal clear.

Though students will most likely be familiar with the broad generic structure of essays, it is worth investing time to ensure they have a clear conception of how each part of the essay works, that is, of the exact nature of the task it performs. Let’s review:

Common Essay Structure

Introduction: Provides the reader with context for the essay. It states the broad argument that the essay will make and informs the reader of the writer’s general perspective and approach to the question.

Body Paragraphs: These are the ‘meat’ of the essay and lay out the argument stated in the introduction point by point with supporting evidence.

Conclusion: Usually, the conclusion will restate the central argument while summarising the essay’s main supporting reasons before linking everything back to the original question.

ESSAY WRITING PARAGRAPH WRITING TIPS

● Each paragraph should focus on a single main idea

● Paragraphs should follow a logical sequence; students should group similar ideas together to avoid incoherence

● Paragraphs should be denoted consistently; students should choose either to indent or skip a line

● Transition words and phrases such as alternatively , consequently , in contrast should be used to give flow and provide a bridge between paragraphs.

HOW TO EDIT AN ESSAY

Students shouldn’t expect their essays to emerge from the writing process perfectly formed. Except in exam situations and the like, thorough editing is an essential aspect in the writing process.

Often, students struggle with this aspect of the process the most. After spending hours of effort on planning, research, and writing the first draft, students can be reluctant to go back over the same terrain they have so recently travelled. It is important at this point to give them some helpful guidelines to help them to know what to look out for. The following tips will provide just such help:

One Piece at a Time: There is a lot to look out for in the editing process and often students overlook aspects as they try to juggle too many balls during the process. One effective strategy to combat this is for students to perform a number of rounds of editing with each focusing on a different aspect. For example, the first round could focus on content, the second round on looking out for word repetition (use a thesaurus to help here), with the third attending to spelling and grammar.

Sum It Up: When reviewing the paragraphs they have written, a good starting point is for students to read each paragraph and attempt to sum up its main point in a single line. If this is not possible, their readers will most likely have difficulty following their train of thought too and the paragraph needs to be overhauled.

Let It Breathe: When possible, encourage students to allow some time for their essay to ‘breathe’ before returning to it for editing purposes. This may require some skilful time management on the part of the student, for example, a student rush-writing the night before the deadline does not lend itself to effective editing. Fresh eyes are one of the sharpest tools in the writer’s toolbox.

Read It Aloud: This time-tested editing method is a great way for students to identify mistakes and typos in their work. We tend to read things more slowly when reading aloud giving us the time to spot errors. Also, when we read silently our minds can often fill in the gaps or gloss over the mistakes that will become apparent when we read out loud.

Phone a Friend: Peer editing is another great way to identify errors that our brains may miss when reading our own work. Encourage students to partner up for a little ‘you scratch my back, I scratch yours’.

Use Tech Tools: We need to ensure our students have the mental tools to edit their own work and for this they will need a good grasp of English grammar and punctuation. However, there are also a wealth of tech tools such as spellcheck and grammar checks that can offer a great once-over option to catch anything students may have missed in earlier editing rounds.

Putting the Jewels on Display: While some struggle to edit, others struggle to let go. There comes a point when it is time for students to release their work to the reader. They must learn to relinquish control after the creation is complete. This will be much easier to achieve if the student feels that they have done everything in their control to ensure their essay is representative of the best of their abilities and if they have followed the advice here, they should be confident they have done so.

WRITING CHECKLISTS FOR ALL TEXT TYPES

ESSAY WRITING video tutorials

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Teach Essay Writing

Last Updated: June 26, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD . Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014. There are 12 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 88,748 times.

Teaching students how to write an essay is a big undertaking, but this is a crucial process for any high school or college student to learn. Start by assigning essays to read and then encourage students to choose an essay topic of their own. Spend class time helping students understand what makes a good essay. Then, use your assignments to guide students through writing their essays.

Choosing Genres and Topics

- Narrative , which is a non-fiction account of a personal experience. This is a good option if you want your students to share a story about something they did, such as a challenge they overcame or a favorite vacation they took. [2] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Expository , which is when you investigate an idea, discuss it at length, and make an argument about it. This might be a good option if you want students to explore a specific concept or a controversial subject. [3] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Descriptive , which is when you describe a person, place, object, emotion, experience, or situation. This can be a good way to allow your students to express themselves creatively through writing. [4] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Argumentative or persuasive essays require students to take a stance on a topic and make an argument to support that stance. This is different from an expository essay in that students won't be discussing a concept at length and then taking a position. The goal of an argumentative essay is to take a position right away and defend it with evidence. [5] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Make sure to select essays that are well-structured and interesting so that your students can model their own essays after these examples. Include essays written by former students, if you can, as well as professionally written essays.

Tip : Readers come in many forms. You can find readers that focus on a specific topic, such as food or pop culture. You can also find reader/handbook combos that will provide general information on writing along with the model essays.

- For example, for each of the essays you assign your students, you could ask them to identify the author's main point or focus, the structure of the essay, the author's use of sources, and the effect of the introduction and conclusion.

- Ask the students to create a reverse outline of the essay to help them understand how to construct a well-written essay. They'll identify the thesis, the main points of the body paragraphs, the supporting evidence, and the concluding statement. Then, they'll present this information in an outline. [8] X Research source

- For example, if you have assigned your students a narrative essay, then encourage them to choose a story that they love to tell or a story they have always wanted to tell but never have.

- If your students are writing argumentative essays, encourage them to select a topic that they feel strongly about or that they'd like to learn more about so that they can voice their opinion.

Explaining the Parts of an Essay

- For example, if you read an essay that begins with an interesting anecdote, highlight that in your class discussion of the essay. Ask students how they could integrate something like that into their own essays and have them write an anecdotal intro in class.

- Or, if you read an essay that starts with a shocking fact or statistic that grabs readers' attention, point this out to your students. Ask them to identify the most shocking fact or statistic related to their essay topic.

- For example, you could provide a few model thesis statements that students can use as templates and then ask them to write a thesis for their topic as an in-class activity or have them post it on an online discussion board.

Tip : Even though the thesis statement is only 1 sentence, this can be the most challenging part of writing an essay for some students. Plan to spend a full class session on writing thesis statements and review the information multiple times as well.

- For example, you could spend a class session going over topic sentences, and then look at how the authors of model essays have used topic sentences to introduce their claims. Then, identify where the author provides support for a claim and how they expand on the source.

- For example, you might direct students to a conclusion in a narrative essay that reflects on the significance of an author's experience. Ask students to write a paragraph where they reflect on the experience they are writing about and turn it in as homework or share it on class discussion board.

- For an expository or argumentative essay, you might show students conclusions that restate the most important aspect of a topic or that offer solutions for the future. Have students write their own conclusions that restate the most important parts of their subject or that outline some possible solutions to the problem.

Guiding Students Through the Writing Process

- Try giving students a sample timeline for how to work on their essays. For example, they might start brainstorming a topic, gathering sources (if required), and taking notes 4 weeks before the paper is due.

- Then, students might begin drafting 2 weeks before the paper is due with a goal of having a full draft 1 week before the essay's due date.

- Students could then plan to start revising their drafts 5 days before the essay is due. This will provide students with ample time to read through their papers a few times and make changes as needed.

- Freewriting, which is when you write freely about anything that comes to mind for a set amount of time, such as 10, 15, or 20 minutes.

- Clustering, which is when you write your topic or topic idea on a piece of paper and then use lines to connect that idea to others.

- Listing, which is when you make a list of any and all ideas related to a topic and ten read through it to find helpful information for your paper.

- Questioning, such as by answering the who, what, when, where, why, and how of their topic.

- Defining terms, such as identifying all of the key terms related to their topic and writing out definitions for each one.

- For example, if your students are writing narrative essays, then it might make the most sense for them to describe the events of a story chronologically.

- If students are writing expository or argumentative essays, then they might need to start by answering the most important questions about their topic and providing background information.

- For a descriptive essay, students might use spatial reasoning to describe something from top to bottom, or organize the descriptive paragraphs into categories for each of the 5 senses, such as sight, sound, smell, taste, and feel.

- For example, if you have just gone over different types of brainstorming strategies, you might ask students to choose 1 that they like and spend 10 minutes developing ideas for their essay.

- Try having students post a weekly response to a writing prompt or question that you assign.

- You may also want to create a separate discussion board where students can post ideas about their essay and get feedback from you and their classmates.

- You could also assign specific parts of the writing process as homework, such as requiring students to hand in a first draft as a homework assignment.

- For example, you might suggest reading the paper backward 1 sentence at a time or reading the paper out loud as a way to identify issues with organization and to weed out minor errors. [21] X Trustworthy Source University of North Carolina Writing Center UNC's on-campus and online instructional service that provides assistance to students, faculty, and others during the writing process Go to source

- Try peer-review workshops that ask students to review each others' work. Students can work in pairs or groups during the workshop. Provide them with a worksheet, graphic organizer, or copy of the assignment rubric to guide their peer-review.

Tip : Emphasize the importance of giving yourself at least a few hours away from the essay before you revise it. If possible, it is even better to wait a few days. After this time passes, it is often easier to spot errors and work out better ways of describing things.

Community Q&A

- Students often need to write essays as part of college applications, for assignments in other courses, and when applying for scholarships. Remind your students of all the ways that improving their essay writing skills can benefit them. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/essay_writing/index.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/essay_writing/narrative_essays.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/essay_writing/expository_essays.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/essay_writing/descriptive_essays.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/essay_writing/argumentative_essays.html

- ↑ https://wac.colostate.edu/jbw/v1n2/petrie.pdf

- ↑ https://www.uww.edu/learn/restiptool/improve-student-writing

- ↑ https://twp.duke.edu/sites/twp.duke.edu/files/file-attachments/reverse-outline.original.pdf

- ↑ https://www.niu.edu/citl/resources/guides/instructional-guide/brainstorming.shtml

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/faculty-resources/tips-on-teaching-writing/situating-student-writers/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/faculty-resources/tips-on-teaching-writing/in-class-writing-exercises/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/revising-drafts/

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Oct 13, 2017

Did this article help you?

Jul 11, 2017

Jan 26, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

- Utility Menu

- Writing Center

- Writing Program

- Guides to Teaching Writing

The Harvard Writing Project publishes resource guides for faculty and teaching fellows that help them integrate writing into their courses more effectively — for example, by providing ideas about effective assignment design and strategies for responding to student writing.

A list of current HWP publications for faculty and teaching fellows is provided below. Most of the publications are available for download as PDF files. If you would like to be added to the Bulletin mailing list or to receive printed copies of any of the guides listed below, email James Herron at [email protected].

HARVARD WRITING PROJECT BRIEF GUIDES TO TEACHING WRITING

OTHER HARVARD WRITING PROJECT TEACHING GUIDES

- Pedagogy Workshops

- Advice for Teaching Fellows

- HarvardWrites Instructor Toolkit

- Additional Resources for Teaching Fellows

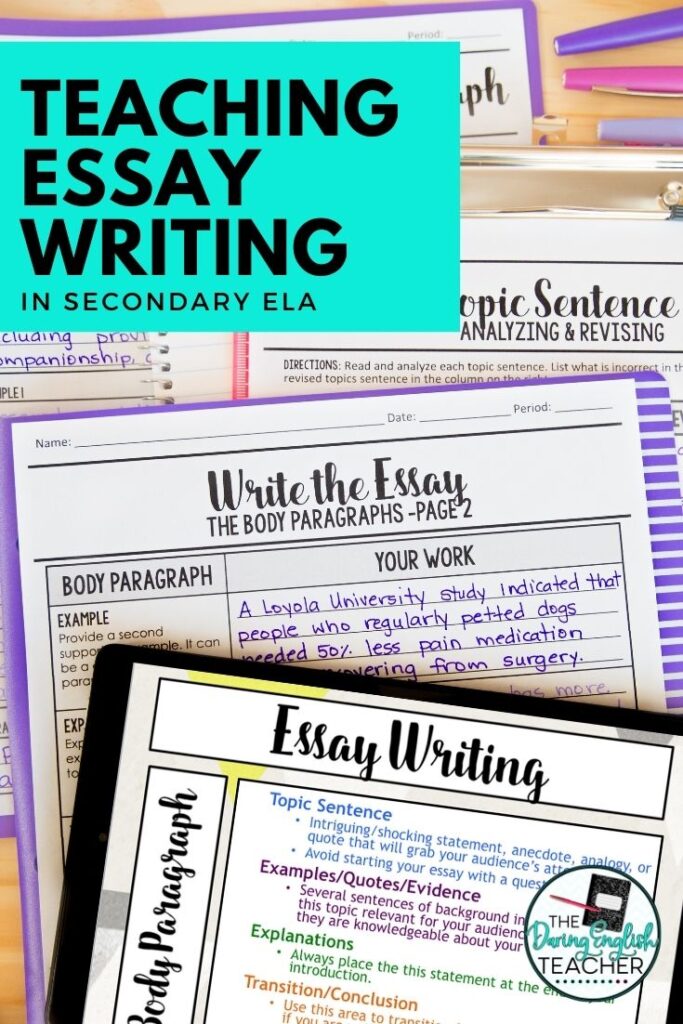

How to Teach Essay Writing in Secondary ELA

Teaching students how to write a multi-paragraph essay is a process, and it isn’t something that can be taught in one class period, nor is it a skill that we should expect our incoming students to know. Before I even assign my students a multi-paragraph essay, I first take several weeks to teach paragraph writing, and I typically do this with my short story unit.

However, once my students are ready to make the jump from paragraphs to an essay, I still continue to break down my writing instruction. When I teach essay writing in my high school English students, I break it down paragraph-by-paragraph to encourage them to be the best writer they can be. All of the lessons that I will refer to throughout this blog post are included in this print and digital essay writing teaching unit .

Teach Essay Writing in Middle School and High School ELA

Start with brainstorming.

I am a huge fan of group brainstorming, especially since I usually have some EL and SPED students mainstreamed in my college prep English classes. I usually dedicate an entire class period to brainstorming where students gather ideas, paragraph topics, and supporting quotes. You can read more about group brainstorming in this blog post where I discuss brainstorming with my students and I teach them how to brainstorm an essay.

Outline the essay

After brainstorming, I move my students to the outlining phase of the writing process. This step is essential because it helps students organize their papers and stay on topic. Ever since I started dedicating an entire class period to in-class essay outlining, I’ve noticed a significant improvement in my students’ essays. You can read more about how I teach essay outlining in this blog post . When we focus on outlining the essay, I make sure that we focus on all of the essential components of an essay: thesis statement, topic sentences, and evidence.

Write the thesis statement

After the class has completed the brainstorming and outlining, I then move on to direct instruction for essay writing. Since students have already outlined their main ideas, they can start working on their thesis statement. I use my introduction and thesis statement lesson to help students write a meaningful thesis statement. I also look at examples of good thesis statements with my students and have students turn in their draft thesis statements to me before moving on.

Write the introduction

Once students have a solid working thesis statement (and I say working because it is possible for it to change throughout this process), I then have them move on to the introduction. Using the same introduction and thesis writing lesson, I then have my students work on drafting a hook and background information to complete their introduction. Now that students are in high school, I don’t accept a question as an acceptable hook. However, if my students get stuck, especially some of my lower students, I have them write their questions and then help them turn them into a statement.

Also, I’ve noticed that students sometimes have a hard time jumping on the hook. They tend to get stuck there, and when this happens, I have them jump right into the background information. In doing so, students get started writing, and they can go back to the hook later.

Topic Sentences

When I complete essay outlining with my students before the drafting process, I typically have them outline each paragraph with a topic sentence and then the quotes they want to use. Once we move from the introduction to the body paragraphs, I have them work on their topic sentence first. I use my topic sentences and body paragraphs essay writing lesson with my students at this point in the essay. Once students have a good topic sentence for their body paragraph, they write the rest of their body paragraph.

Write the body paragraphs

The next step in the writing process, especially for the first essay of the school year, is for students to write out the rest of their body paragraphs. If they’ve done their outlining correctly, they have a good idea about what they want to include in their body paragraphs. In this step, I really emphasize that my students need to provide support and analysis. They should be providing more explanation than simply restating their quotes.

Write the conclusion

Once students have their introduction and body paragraphs complete, I then have them move on to writing the conclusion. At this step, I teach conclusion writing to my students and have them restate the thesis and add a general thought to the end of the paragraph. At this point, I emphasize that students should not be adding in any new information. Also, one way to help students rephrase their thesis statement is to have them rewrite it in two sentences since a thesis statement is typically a one-sentence statement.

Complete peer editing

Provide time for essay revisions

Once students revise their essays and turn them in, I still like to provide students with some time to revise their essays after I grade them. This is where true learning and growth happen. It is when a student thinks they are done but then goes back to try to improve their essay. In this blog post about essay revisions , you can read more about how I conduct them in the classroom.

An entire year of writing instruction

What if I told you that you could have all of your writing instruction for the ENTIRE SCHOOL YEAR planned and ready to go? I’m talking about all the major writing strands and peer editing to grading rubrics. Just imagine how much time and stress you’ll save!

It almost sounds too good to be true, right?

It’s not! My Ultimate Writing Bundle is your one-stop shop for all of your writing instruction needs! Plus, your students will thrive with the built-in scaffolding and consistency throughout the year!

Join the Daring English Teacher community!

Subscribe to receive freebies, teaching ideas, and my latest content by email.

I won’t send you spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

Built with ConvertKit

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Four Strategies for Effective Writing Instruction

- Share article

(This is the first post in a two-part series.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What is the single most effective instructional strategy you have used to teach writing?

Teaching and learning good writing can be a challenge to educators and students alike.

The topic is no stranger to this column—you can see many previous related posts at Writing Instruction .

But I don’t think any of us can get too much good instructional advice in this area.

Today, Jenny Vo, Michele Morgan, and Joy Hamm share wisdom gained from their teaching experience.

Before I turn over the column to them, though, I’d like to share my favorite tool(s).

Graphic organizers, including writing frames (which are basically more expansive sentence starters) and writing structures (which function more as guides and less as “fill-in-the-blanks”) are critical elements of my writing instruction.

You can see an example of how I incorporate them in my seven-week story-writing unit and in the adaptations I made in it for concurrent teaching.

You might also be interested in The Best Scaffolded Writing Frames For Students .

Now, to today’s guests:

‘Shared Writing’

Jenny Vo earned her B.A. in English from Rice University and her M.Ed. in educational leadership from Lamar University. She has worked with English-learners during all of her 24 years in education and is currently an ESL ISST in Katy ISD in Katy, Texas. Jenny is the president-elect of TexTESOL IV and works to advocate for all ELs:

The single most effective instructional strategy that I have used to teach writing is shared writing. Shared writing is when the teacher and students write collaboratively. In shared writing, the teacher is the primary holder of the pen, even though the process is a collaborative one. The teacher serves as the scribe, while also questioning and prompting the students.

The students engage in discussions with the teacher and their peers on what should be included in the text. Shared writing can be done with the whole class or as a small-group activity.

There are two reasons why I love using shared writing. One, it is a great opportunity for the teacher to model the structures and functions of different types of writing while also weaving in lessons on spelling, punctuation, and grammar.

It is a perfect activity to do at the beginning of the unit for a new genre. Use shared writing to introduce the students to the purpose of the genre. Model the writing process from beginning to end, taking the students from idea generation to planning to drafting to revising to publishing. As you are writing, make sure you refrain from making errors, as you want your finished product to serve as a high-quality model for the students to refer back to as they write independently.

Another reason why I love using shared writing is that it connects the writing process with oral language. As the students co-construct the writing piece with the teacher, they are orally expressing their ideas and listening to the ideas of their classmates. It gives them the opportunity to practice rehearsing what they are going to say before it is written down on paper. Shared writing gives the teacher many opportunities to encourage their quieter or more reluctant students to engage in the discussion with the types of questions the teacher asks.

Writing well is a skill that is developed over time with much practice. Shared writing allows students to engage in the writing process while observing the construction of a high-quality sample. It is a very effective instructional strategy used to teach writing.

‘Four Square’

Michele Morgan has been writing IEPs and behavior plans to help students be more successful for 17 years. She is a national-board-certified teacher, Utah Teacher Fellow with Hope Street Group, and a special education elementary new-teacher specialist with the Granite school district. Follow her @MicheleTMorgan1:

For many students, writing is the most dreaded part of the school day. Writing involves many complex processes that students have to engage in before they produce a product—they must determine what they will write about, they must organize their thoughts into a logical sequence, and they must do the actual writing, whether on a computer or by hand. Still they are not done—they must edit their writing and revise mistakes. With all of that, it’s no wonder that students struggle with writing assignments.

In my years working with elementary special education students, I have found that writing is the most difficult subject to teach. Not only do my students struggle with the writing process, but they often have the added difficulties of not knowing how to spell words and not understanding how to use punctuation correctly. That is why the single most effective strategy I use when teaching writing is the Four Square graphic organizer.

The Four Square instructional strategy was developed in 1999 by Judith S. Gould and Evan Jay Gould. When I first started teaching, a colleague allowed me to borrow the Goulds’ book about using the Four Square method, and I have used it ever since. The Four Square is a graphic organizer that students can make themselves when given a blank sheet of paper. They fold it into four squares and draw a box in the middle of the page. The genius of this instructional strategy is that it can be used by any student, in any grade level, for any writing assignment. These are some of the ways I have used this strategy successfully with my students:

* Writing sentences: Students can write the topic for the sentence in the middle box, and in each square, they can draw pictures of details they want to add to their writing.

* Writing paragraphs: Students write the topic sentence in the middle box. They write a sentence containing a supporting detail in three of the squares and they write a concluding sentence in the last square.

* Writing short essays: Students write what information goes in the topic paragraph in the middle box, then list details to include in supporting paragraphs in the squares.

When I gave students writing assignments, the first thing I had them do was create a Four Square. We did this so often that it became automatic. After filling in the Four Square, they wrote rough drafts by copying their work off of the graphic organizer and into the correct format, either on lined paper or in a Word document. This worked for all of my special education students!

I was able to modify tasks using the Four Square so that all of my students could participate, regardless of their disabilities. Even if they did not know what to write about, they knew how to start the assignment (which is often the hardest part of getting it done!) and they grew to be more confident in their writing abilities.

In addition, when it was time to take the high-stakes state writing tests at the end of the year, this was a strategy my students could use to help them do well on the tests. I was able to give them a sheet of blank paper, and they knew what to do with it. I have used many different curriculum materials and programs to teach writing in the last 16 years, but the Four Square is the one strategy that I have used with every writing assignment, no matter the grade level, because it is so effective.

‘Swift Structures’

Joy Hamm has taught 11 years in a variety of English-language settings, ranging from kindergarten to adult learners. The last few years working with middle and high school Newcomers and completing her M.Ed in TESOL have fostered stronger advocacy in her district and beyond:

A majority of secondary content assessments include open-ended essay questions. Many students falter (not just ELs) because they are unaware of how to quickly organize their thoughts into a cohesive argument. In fact, the WIDA CAN DO Descriptors list level 5 writing proficiency as “organizing details logically and cohesively.” Thus, the most effective cross-curricular secondary writing strategy I use with my intermediate LTELs (long-term English-learners) is what I call “Swift Structures.” This term simply means reading a prompt across any content area and quickly jotting down an outline to organize a strong response.

To implement Swift Structures, begin by displaying a prompt and modeling how to swiftly create a bubble map or outline beginning with a thesis/opinion, then connecting the three main topics, which are each supported by at least three details. Emphasize this is NOT the time for complete sentences, just bulleted words or phrases.

Once the outline is completed, show your ELs how easy it is to plug in transitions, expand the bullets into detailed sentences, and add a brief introduction and conclusion. After modeling and guided practice, set a 5-10 minute timer and have students practice independently. Swift Structures is one of my weekly bell ringers, so students build confidence and skill over time. It is best to start with easy prompts where students have preformed opinions and knowledge in order to focus their attention on the thesis-topics-supporting-details outline, not struggling with the rigor of a content prompt.

Here is one easy prompt example: “Should students be allowed to use their cellphones in class?”

Swift Structure outline:

Thesis - Students should be allowed to use cellphones because (1) higher engagement (2) learning tools/apps (3) gain 21st-century skills

Topic 1. Cellphones create higher engagement in students...

Details A. interactive (Flipgrid, Kahoot)

B. less tempted by distractions

C. teaches responsibility

Topic 2. Furthermore,...access to learning tools...

A. Google Translate description

B. language practice (Duolingo)

C. content tutorials (Kahn Academy)

Topic 3. In addition,...practice 21st-century skills…

Details A. prep for workforce

B. access to information

C. time-management support

This bare-bones outline is like the frame of a house. Get the structure right, and it’s easier to fill in the interior decorating (style, grammar), roof (introduction) and driveway (conclusion). Without the frame, the roof and walls will fall apart, and the reader is left confused by circuitous rubble.

Once LTELs have mastered creating simple Swift Structures in less than 10 minutes, it is time to introduce complex questions similar to prompts found on content assessments or essays. Students need to gain assurance that they can quickly and logically explain and justify their opinions on multiple content essays without freezing under pressure.

Thanks to Jenny, Michele, and Joy for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones are not yet available). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

- Race & Racism in Schools

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Facing Gender Challenges in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech in the Classroom

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in Schools

- Teaching English-Language Learners

- Reading Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- Entering the Teaching Profession

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in Schools

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

How To Teach Argumentative Essay Writing

Teaching argumentative essay writing can be a real challenge. In addition to teaching writing, you’re also teaching skills like research and refutation. Luckily, this post includes the tips you need for effectively teaching argumentative essay writing.

I have great news for any of you gearing up to teach argumentative essay writing. Those students of yours love to argue. (Don’t believe me? Just ask their parents!) Students love to stand up for their opinion, proving their view is correct. The challenge, then, is getting them to look at the whole picture, find supporting evidence and understand the opposing viewpoints. Only then can they craft an argument that is both factually strong and persuasive. Overall, it’s about moving them beyond the blinders of their opinions and taking a more sound evidence-based approach.

Teaching argumentative essay writing doesn’t have to be such a painful experience for both you and your students. Follow the steps and strategies below to learn how to approach the dreaded argumentative essay more easily.

The Challenge with Teaching Argumentative Essay Writing

Why is teaching argumentative essay writing so difficult, you ask? I’ve been there. The truth is, when teaching argumentative essay writing, you’re teaching more than writing . You’re also teaching research skills and encouraging critical thought and analysis. You also need to explain how to evaluate sources and evidence and the difference between fact and opinion. In many ways, you’re teaching tolerance and perspective. (The list goes on.)

Long story short, it makes sense that it’s a challenge. The key is to not rush into it. Take it step-by-step, building upon what students already know.

Moving Beyond Persuasion

The good news? Many of your students have a foundational knowledge of persuasive writing that you can use as a springboard for teaching argumentative essay writing. However, it’s important to note that, while many use the terms interchangeably, they’re not quite the same. The main difference? Factual evidence. Your students might be used to persuasive writing, meaning writing to convince the reader of a claim rooted in their personal opinion . While it’s likely that students will argue something they are in favor of, argumentative essay writing involves using claims supported by factual evidence. Additionally, a hallmark of the argumentative essay is addressing the opposing viewpoint, a step that many students are unfamiliar with– and find rather challenging.

Consider the following steps as you move from persuasion to argumentative essay writing:

Step 1: Start with Casual Augmentation

Engage your students in a low-stakes debate before formally teaching argumentative essay writing. This approach will help get students in the right mindset as you begin to lay the foundation for effective argumentation. Don’t even mention the word essay at this point. Keep it fun and casual to break the ice.

There are many ways to approach casual argumentation in class. You can begin with an anticipation guide of controversial yet appropriate statements. After students fill it out, foster a group discussion in which students share their thoughts regarding each statement. Encourage them to move beyond simple opinions by asking why to get them to dig deeper as they support their stance.

To get your students up and moving, consider playing a game like Four Corners to get them to take a stance on a topic. Regardless of which activity you choose, spend time discussing the students’ stances. Small debates are likely to unfold right then and there.

Step 2: Add In Evidence, But Still Keep It Casual

You’ve causally engaged students in basic argumentation. However, before moving into a full-blown argumentative essay, dip students’ toes into the world of supporting evidence. Use the same activity above or write a simple yet controversial topic on the board for them to take a stance on. This time, give students a chance to gather supporting evidence. It might be worth quickly reviewing what makes a sound piece of evidence (research, studies, statistics, expert quotes, etc.). Then, once they pick their stance, allow five to ten minutes to gather the best piece of supportive evidence they can find. After, give them another five to ten minutes to work with the others in their corner/on their side to determine the strongest two or three pieces of evidence to share with the class. Once each team does this, have them take turns sharing their stance and supporting evidence. I like to leave room at the end for “final words” where they can respond to a point made by the other side.

During this simple activity, begin to unpack the importance of solid and relevant supporting evidence.

Step 3: Bring in the Opposing Viewpoints

Don’t stop there. One of the most challenging aspects of argumentative writing for students to grasp is acknowledging and responding to the opposition. They are often blinded by their experiences, perspectives, and opinions that they neglect the opposing side altogether.

Here’s what you can do: Repeat either activity above with a slight twist. Once students pick their side, switch it up. Instead of supporting the side they chose, ask them to research the other side and find the best supporting evidence to bring back to the class. Therefore, students will engage in a casual debate, supporting an opposing viewpoint. (For a simpler, more independent version of this, write a controversial statement on the board, have students take a stance, and then find evidence for the opposing side, putting it all into a written response.) While many students might complain at first, you’d be surprised how quickly they get into the task. Activities like these lay the groundwork for making evidence-based claims. Additionally, students will begin to recognize the role of perspective in argumentation.

Step 4: Introduce the Argumentative Essay

Now it’s time to introduce the argumentative essay. Many students will be tempted to jump right into writing. Therefore, make it clear that argumentative essay writing involves deeply investigating a topic before writing.

Next, explain how argumentative writing aims to take a stance on a topic and back it up with substantial supporting evidence. Additionally, include how argumentative essay writing requires acknowledging the opposing viewpoint. As for persuasion, explain that it must work in coordination with collected evidence rather than being rooted solely in one’s opinion.

When introducing the argumentative essay, it helps to outline the essay structure, showing students where it is both similar and different from the essays they are used to:

- Begin with an introductory paragraph. This is where the students will hook their readers and provide a summary of the issue, any relative background information, and a well-defined claim. (This is a great place to explain that claim is another word for a thesis statement used in argumentative writing.)

- Then comes the logically organized body paragraphs, each unpacking evidential support of the claim. While students are used to using body paragraphs to support their claim, remind them one body paragraph must reference and refute the opposing side.

- Finally comes the conclusion. Students are no strangers to writing conclusions. However, they should be moving beyond simply restating the thesis at the secondary level. Guide them through readdressing it in a way that acknowledges the presented evidence and leaves the author with something to think about.

Students will likely recognize the similarity between this and the traditional five-paragraph essay. Therefore, focus your teaching on the newer elements thrown into the mix that truly make it an argumentative essay.

Teacher Tip.

Incorporate various mentor texts to help students grasp the elements of argumentative essay writing. There are tons you can pull offline written by students and experts alike. ( The New York Times Learning Network has some great mentor text resources!) The more interesting your students find the subject matter, the better. Controversial topics always stir up an engaging conversation as well.

Teaching the Argumentative Essay Writing Process

Remember, students can quickly fall into old habits, neglecting some of the most imperative aspects of argumentative writing. Take it slow, walking students through the following steps – trust me, you’ll be thankful you did when it comes time to read a pile of these essays:

- Choose a topic. I recommend providing a list of argumentative essay writing topics for students to choose from. This prevents students’ classic “I can’t think of anything” roadblock. However, encourage students to choose a topic they are interested in or feel passionate about. With that said, I always give the option of letting students convince me (ha!) to let them use a topic they came up with if not on the list.

- Start the research. This is where students begin gathering evidence and is an opportunity to review what constitutes strong evidence in the first place.

- Understand the opposing side: Students are always confused about why I have them start here. One reason? It’s more challenging for students to see the other side, so this gets it out of the way first. Another? Some students never took the time to understand the other side, and in some cases, they switch their stance before writing their argument. It’s better to do so now than after you’ve done all your research and drafting. Lastly, I explain how understanding the opposing side can help guide your research for your side.

- Make a claim. While students may have an idea of their claim, the strongest claims are driven by evidence . Therefore, remind students that a claim is a statement that can be supported with evidence and reasoning and debated. Playing a quick game of two truths and an opinion (a spin on two truths and a lie) can reinforce the notion of facts vs. opinions.

- Write the body paragraphs. Each body paragraph should focus on supporting the claim with specific evidence. However, don’t forget to rebut the opposition! While they find it challenging, students learn to love this part. (After all, they love being right.) However, their instinct tends to be just to prove the other side wrong without using evidence as to why.

- Round out the intro and the conclusion, put it all together, and voila! An argumentative essay is born.

More Tips for Teaching Argumentative Essay Writing

- Begin with what they know: Build on the well-known five-paragraph essay model. Start with something students know. Many are already familiar with the classic five-paragraph essay, right? Use that as a reference point, noting out where they will add new elements, such as opposing viewpoints and rebuttal.

- Use mentor texts: Mentor texts help give students a frame of reference when learning a new genre of writing. However, don’t stop at reading the texts. Instead, have students analyze them, looking for elements such as the authors’ claims, types of evidence, and mentions of the opposing side. Additionally, encourage students to discuss where the author made the most substantial arguments and why.

- In [ARTICLE NAME/STUDY], the author states…

- According to…,

- This shows/illustrates/explains…

- This means/confirms/suggests…

- Opponents of this idea claim/maintain that… however…

- Those who disagree/are against these ideas may say/ assert that… yet…

- On the other hand…

- This is not to say that…

- Provide clear guidelines: I love using rubrics, graphic organizers, and checklists to help students stay on track throughout the argumentative essay writing process. Use these structured resources to help them stay on track every step of the way– and makes grading much easier for you .

The bottom line? Teaching argumentative essay writing is a skill that transcends the walls of our classrooms. The art of making and supporting a sound, evidence-based argument is a real-life skill. If our goal as teachers is to prepare students to be skilled, active, and engaged citizens of the 21st century, effectively teaching argumentative essay writing is a must. So, what are you waiting for? Teach those kids how to argue the write way.

1 thought on “How To Teach Argumentative Essay Writing”

This is very helpful. I am preparing to teach my student how to write an argumentative essay. This help me know that I am on the right path and to change how I organize some things in a different way. I really like how you recommended they pick out the elements of the writing. This will help them focus on the parts they dislike doing the most. Thanks for the writing.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Visit our sister organization:

THE LEARNING CURVE

a magazine devoted to gaining skills and knowledge.

THE LEARNING AGENCY LAB ’S LEARNING CURVE COVERS THE FIELD OF EDUCATION AND THE SCIENCE OF LEARNING. READ ABOUT METACOGNITIVE THINKING OR DISCOVER HOW TO LEARN BETTER THROUGH OUR ARTICLES, MANY OF WHICH HAVE INSIGHTS FROM EXPERTS WHO STUDY LEARNING.

How To Teach Writing To Anyone

- March 19, 2020

Writing is a key skill. The ability to put words down on paper is a critical skill for success in college and career, but few students graduate high school as proficient writers. Less than a third of high school seniors are proficient writers, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). Low-income, and Black and Hispanic students fare far worse and less than 15 percent scoring proficient.

So how can students learn to write better? What tools do they need to become better at making an argument on paper? In this document, we’re largely focused on argumentative writing, which is central to, well, just about every aspect of modern life, from emails to workplace memos to empowered citizens.

Teaching argumentative writing involves teaching both argumentation and writing. This means there’s research on how to teach writing, there’s research on how to teach argumentation, and there’s research on the intersection of the two.

Earlier research in this topic often referred to it as “persuasive” writing. More recent research seems to prefer and use the term “argumentative” writing. One reason why is that “argumentative” is seen as a broader term. Persuasion is a particular goal that argumentative writing might have. But argumentative writing is seen to encompass many possible goals: persuasion, but also analysis, collaborative problem-solving, and conceptual clarity.

Main takeaways

There are important nuances further below, but the general picture of best practice based on experimental and quasi-experimental research looks something like the following:

- Students need sufficient foundational skills and knowledge (in spelling, typing, content-specific knowledge) and may be taught some of this knowledge in the course of writing . This means that educators in early grades should work on building basic skills in hand-writing, spelling, and typing, and that educators in later grades spend some time focusing on sentence-building skills and incorporate content learning into writing assignments.

- Students benefit from a writing environment where they write and edit frequently using word processing software on long pieces of writing that generate student interest. Although students in early grades may by predominantly writing by hand, as they move on to late elementary school and middle school they should transition to typing, which enables more rapid editing. Although work on basic transcription and sentence-building skills is vital, educators also need to assign longer pieces of work as students progress.

- Students benefit from clear writing purposes and from having well-defined goals for improvement. This suggests that educators choose writing assignments that have larger purposes beyond simply being submitted for a grade—student writing that is published, displayed, or otherwise shared can improve student motivation. It also suggests that educators carefully structure the revision process. For instance, revision goals like “come up with two more reasons in favor of your argument and one reason in favor of an opposing argument” help students meaningfully revise their papers.

- Students benefit from instruction on models of good and bad writing, and through explicit strategies in the writing process: for example, pre-writing techniques, ways of organizing the material, making their reasoning explicit. Educators must correct misperceptions of what writing that focus on the product of writing (instead of the process). And they must be explicit about the strategies that good writers use to ultimately create solid writing.

- Students benefit from guidance in genre-specific practices (for instance, diagrams that help students “fill out” both sides of an argument, character sheets that help students flesh out the characters in their narratives, etc.). Educators can’t assume that skill in one genre of writing will necessarily transfer to others; students have to be taught about the expectations and norms of the writing community.

- Students benefit from collaborating with each other: editing, receiving feedback, and editing again, or even working in groups to co-write material. Providing feedback to others seems to provide as much or more benefit to writing skill as editing one’s own paper. Educators should focus on teaching students how to edit judiciously and provide feedback in a supportive way.

Learning to Write

There is also an increasing recognition of the discipline- and genre-specific nature of writing. It’s not about teaching a single, relatively discrete skill — “writing” — but about teaching ways writing in science , ways of writing in history , ways of writing in literature. Writing in any genre is not a fully transferable skill—it requires contextual knowledge (about the purpose and the audience of the work), content knowledge (about the subject of the work), and writing process knowledge.

Methods and Approaches

Experimental and quasi-experimental work in this area has been the subject of many meta-analyses, with slightly differing emphases. These are fairly comprehensive quantitative summaries of the work in this area, but a substantial number of the underlying studies have methodological problems of one sort or another: e.g., no random assignment, no controlling for the Hawthorne effect, no measures of whether the intervention was implemented with fidelity, or simply no descriptions of the control condition.

More recent studies tend to be of higher quality, and also result in higher effect sizes than older studies (suggesting that earlier studies may have been understating the effect of some of the proposed interventions).

Meta-analyses look at broad swaths of different studies and group studies into categories to be able to calculate the effects of individual types of interventions. These categories are not always mutually exclusive. For instance, the distinction between “writing process” models (which focus on the process of writing — prewriting, organizing, drafting, editing, revising, etc.), “self-regulation” models (which focus on setting writing goals and teaching students to monitor their writing and editing to achieve those goals), and “peer writing” models (where student co-write and edit each others work) can overlap substantially. In other cases, single categories encompass quite a diverse set of practices. For instance, the “strategy instruction” model includes interventions involving pre-writing activities, peer writing, persuasive writing structures, etc.

Another complexity is how writing outcomes are measured. Rubric-based instruction may help students improve their writing when measured by the rubric, but not necessarily when evaluated through other means.

Research evaluating the popular 6+1 trait writing model, for example, shows little improvement in student outcomes when those outcomes are not measured with the 6+1 writing rubric.

Main Takeaways About Learning To Write

Teachers don’t assign enough writing..

The survey’s results, however, suggest some improvements in teacher practice compared to 40 years ago. Compared to an assessment made in 1979-80, teachers are giving students more questions that ask for more original analysis, they’re incorporating more research-backed strategies like process writing, explicit strategy instruction, and collaborative writing in the curriculum, and they use technology more often.

These findings dovetail with another recent large-scale survey of 361 high school teachers across several disciplines. Again, the main finding is that students don’t compose texts that are long enough (most writing practice asks students to compose texts one-paragraph in length or less), and that few writing assignments as students for analysis and interpretation. Moreover, most teachers say they are not prepared to teach writing (71% say they had either no or minimal college-level training in the subject in their teacher preparation programs).

Although experts argue that argumentative writing should happen across all disciplines, English teachers have often shouldered the main responsibility for teaching writing skills of all sorts (at least as judged by the surveys mentioned earlier). This emphasis, however, clashes with a tradition of emphasizing the literary tradition in English language arts classes (e.g., fiction and narrative), rather than argumentation. One way of providing students with more opportunities to write is to have teachers across many disciplines assign writing tasks. This has been a common aim of several reforms.

Time and expertise seem to be the main obstacles to teachers assigning more writing. Teacher workloads are high, while providing meaningful feedback on long pieces of writing takes considerable effort. Teachers report simply not having enough time to assign long pieces of writing, provide feedback on them, and providing lots of opportunities for revision.

Many teachers also report not being very confident in their ability to teach writing, not having the training or experience to teach writing well, or both. This lack of expertise (or at least lack of confidence) also likely discourages teachers from assigning more challenging pieces of writing.

Research has also revealed a number of best practices. The following best practices all improve student outcomes, and are listed in approximate order of effect size (largest to smallest) based on several recent meta-analyses of existing studies

Explicit strategy instruction helps students.

That said, authors of the survey view the overall amount of class time spent on research-backed strategies to be insufficient: for instance, about 3 minutes out of every 50 minute English class period would be devoted to one of the most support strategies—explicit writing strategy instruction.

Teachers should illustrate each strategy and facilitate students’ independent use of each strategy over time. For instance, a pre-writing activity like brainstorming might be initially presented to the students: the teacher can explain what the strategy is, why writers do it, and present a model of the practice to students. Then, the teacher would have students practice brainstorming in small groups, with occasional teacher guidance. After that, students would brainstorm on their own, while the teacher would provide occasional support. Finally, the teacher would encourage students to use brainstorming completely independently (revisiting aspects of the strategy if needed).

Self-regulation strategies can improve outcomes.

The most popular self-regulation strategy is the SRSD (self-regulation and strategy development) model. This integrates both explicit strategy instruction and self-regulation strategies into a classroom context. Teachers don’t just introduce a strategy—they track student progress towards mastery in using the strategy over time, aiming to motivate students and build self-confidence. The SRSD approach uses mnemonics, graphic organizers, and other scaffolds, in addition to developing prior knowledge about specific writing genres as students are taught them. Evidence suggests that the program is one of the most effective classroom programs, but outcome measures stop short of long trajectories (stopping at six months).

Process Writing improves student outcomes. Process writing involves getting students involved in pre-writing, organizing, drafting, revising, re-drafting, and editing their papers. It’s about engaging students in a relatively long-term writing process involving multiple drafts, rounds of peer and/or teacher feedback, and a finalized product. It’s also helpful to have students explain why they made their edits.

Process writing seems to be a key part of many successful writing interventions (such as SRSD), but the evidence on the efficacy of process writing alone is somewhat contradictory.

Most meta-analyses that evaluate process writing as a separate category of intervention find that process writing is a best practice and has substantial effect sizes. This effect, however, seems modulated by professional development — when teachers are not taught how to use process writing approaches effectively, the benefit disappears. A meta-analysis that focused solely on process writing found modest effects for students of average ability, but no significant effects on writing outcomes for struggling writers, which contrasts with qualitative research suggesting the benefits of process writing for struggling writers in particular. Many of the studies in the process-writing-specific meta-analysis also had weak study designs making the claim that process writing doesn’t help struggling writers at best preliminary.

Feedback Drives Achievement.

For feedback to be effective, students must be motivated to use feedback to improve and they must know how to use the feedback effectively. The first is a challenge of classroom culture. The second is a challenge of student knowledge.

Surveys suggest that many students feel like they don’t have enough guidance on what to do with the feedback they receive. One study at the undergraduate level suggests that the main factor influencing whether students implemented changes based on feedback was whether the problem described by the feedback was understood. Problem understanding increased when teachers identified where the problem was, proposed some solutions, and gave a summary of the students’ work.

Even generic automated feedback to scientific arguments can improve students subsequent arguments (e.g., feedback that reads something like “You haven’t provided enough evidence for your argument. You should add more evidence.” The effects, however, were most pronounced for students that had high scores to begin with, suggesting that receptiveness to feedback may also be playing a role.

One of the values of outside feedback (from either peers or teachers) is that students are more likely to make deeper, meaning-related changes in response to outside feedback than they are when making individual revisions.

Peer Collaboration Can Make A Difference.

Peer feedback offers several proposed benefits . Students often perceive peer feedback as more understandable (and therefore, more actionable) than teacher feedback. Students often feel that teacher feedback is insufficient or unhelpful, and, in higher education at least, students report that peers provide more (and more helpful) feedback. Peer feedback is also a way of providing more overall feedback to students (on early or intermediate drafts of a piece of writing, for instance), as it requires less teacher time. Some reports even suggest that peer feedback encourages students to redouble their efforts because of the social pressure to do well on the assignment.

There are, however, also some challenges to peer feedback. Peers can offer valuable feedback, but it’s not quite up to the standards of expert feedback. For instance, in a study where peers used a predefined assessment guideline, peer and expert feedback was structurally comparable, although peers suggested fewer changes, gave more positive judgments and gave less evidential support for their negative judgments.

Another challenge is to develop a classroom culture where feedback is perceived to be helpful and non-threatening. In one study , English Language Learners report liking peer feedback, but also being concerned about hurting their partners feelings or lacking enough knowledge to be helpful. In that study, students preferred online forms of feedback over face-to-face feedback.

Teaching students how to give valuable feedback is a critical step. Not only does this make the peer feedback more valuable for the writer, but it also helps the peer reviewer develop their own revision skills. For instance, a teacher might give peer reviewers some questions to guide their revision process. Questions like: Is the piece suitable for the intended audience—does it use the right tone, the right kinds of vocabulary words and text complexity? Is the overall structure of the argument clear? Etc.

In some cases, learning to provide peer feedback seems to have more benefits to students than receiving feedback. In a study from 2009, one group of students gave feedback on written work throughout the semester while the other group received feedback. Both groups improved over the course of the semester, but the givers improved more than the receivers when they had no prior experience in giving peer feedback.

Foundational skills and knowledge enable students to engage deeply with the material.

Students also need to know genre-specific writing structures and topic-specific vocabulary. For instance, young children have a better understanding of the narrative genre compared to other genres of writing (argumentative writing, scientific reports, poems). When students don’t know enough about the genre expectations, they can’t produce work that’s recognizably within the genre (e.g., when asked for a science report or an argument, they might produce something that’s more like a story).

Genre learning is something that continues throughout careers and later schooling (e.g., imagine learning about the “business case” genre, the “legal memo” genre or the “economic theory paper” genre); it’s part of the overall development of meta-cognitive knowledge. Explicitness about genre expectations also helps marginalized groups (who may not be as familiar with the genres they’re asked to produce) participate more fully.

Word processing lets students edit and revise more easily.

The commonly accepted explanation is that word processing makes editing and organizing a paper easier, and so encourages revision.

Although seventy-five percent of teachers report having students turn in their final draft through a computer, less than half of students use word processing for drafting, editing, and collaborating on written work. This is particularly notable given the presumed mechanism behind the advantage of using word processors over paper-and-pencil to draft and edit: word processors make editing and re-organizing far easier.

More Frequent Practice. Perhaps the simplest intervention that seems to improve writing outcomes is more practice (especially given the evidence on the little amount of practice that students typically get at long-form writing). Establishing writing routines (for example, having students write for fifteen minutes more a day than they currently do) and ensuring that the writing tasks are interesting to students — that the writing has some larger relevance or purpose — seem like important keys to having students write more.

Multiple drafts improve essay quality.

Writing can also improve reading..

Researchers have proposed several explanations for the deep relationship between reading and writing. They both involve common processes. Spelling, for example, helps students read and write. Sentence-combining helps students write complex sentences and comprehend more complex sentences. The writer also has to re-organize what she’s read, leading to deeper reflection of the material. And finally, writing provides insight into what a writer might be thinking, which helps students interpret written work.

Evaluations of programs that integrate reading and writing programs show positive writing outcomes. These programs typically involve professional development and peer collaboration on reading and writing assignments. Part of the explanation may be that reading helps students anticipate what readers may believe as they write. Reading texts that students will write about also increases their prior knowledge of the issues.

Grammar instruction is important but not that helpful for more advanced writers.

Research on common practices among exceptional writing teachers largely complement or confirm the best practices listed above. Exceptional teachers:

- Are excited about teaching writing, making it clear to students that they enjoy the subject and enjoy teaching the subject.

- Publish student work by sharing it with others, displaying it on walls, or publishing it in collections.

- Encourage students to try hard and attribute success to effort (a component of the SRSD approach).