What is dark tourism and why is it so popular?

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

Dark tourism is a type of tourism that has received increasing attention in recent years. TV shows, such as Chernobyl and The Dark Tourist, have introduced the concept of dark tourism to the minds of motives of many tourists around the world. But what is dark tourism? Is dark tourism ethical? How can you be a ‘good’ dark tourist?

In this post I will define the concept of dark tourism, explain why dark tourism is so popular and provide a few examples of dark tourism sites. I will also discuss the ethics of dark tourism, which are somewhat controversial.

What is dark tourism?

Dark tourism definitions

The dark tourism spectrum, why is dark tourism so popular, dark tourism documentary, dark fun factories , dark exhibitions , dark dungeons , dark resting places, dark shrines , dark conflict sites , dark camps of genocide, dark disasters, the ethics of dark tourism, dark tourism at auschwitz, dark tourism at chernobyl, dark tourism at hiroshima, dark tourism at the 9/11 memorial, dark tourism at the killing fields, dark tourism at bikini atoll, dark tourism in berlin, dark tourism at robben island, dark tourism in rwanda, dark tourism at oradur sur glane, dark tourism in pompeii, dark tourism at sedlec ossuary, dark tourism at the island of the dolls, dark tourism: key takeaways, dark tourism: faqs, dark tourism: a conclusion.

Dark tourism, also known as black tourism, thanatourism or grief tourism, is tourism that is associated with death or tragedy.

The act of dark tourism is somewhat controversial, with some viewing it as an act of respect and others as unethical practice.

Popular dark tourism attractions include Auschwitz, Chernobyl and Ground Zero. Lesser known dark tourism attractions might include cemeteries, zombie-themed events or historical museums.

Dark Tourism started to gain academic attention in the early 90s, but it is only recently that it has sparked the interest of the media and the general public.

An early definition defined by John Lennon and Malcolm Foley , define dark tourism as “the representation of inhuman acts, and how these are interpreted for visitors”.

In a more recent publication, Kevin Fox Gotham defines dark tourism as “the circulation of people to places characterized by distress, atrocity, or sadness and pain. As a more specific component of dark tourism, “disaster tourism” denotes situations where the tourism product is generated within, and from, the aftermath of a major disaster or traumatic event”.

Dark tourism has become the subject of academic debate more and more in recent years, most notably for its critiques and assessment of associated impacts.

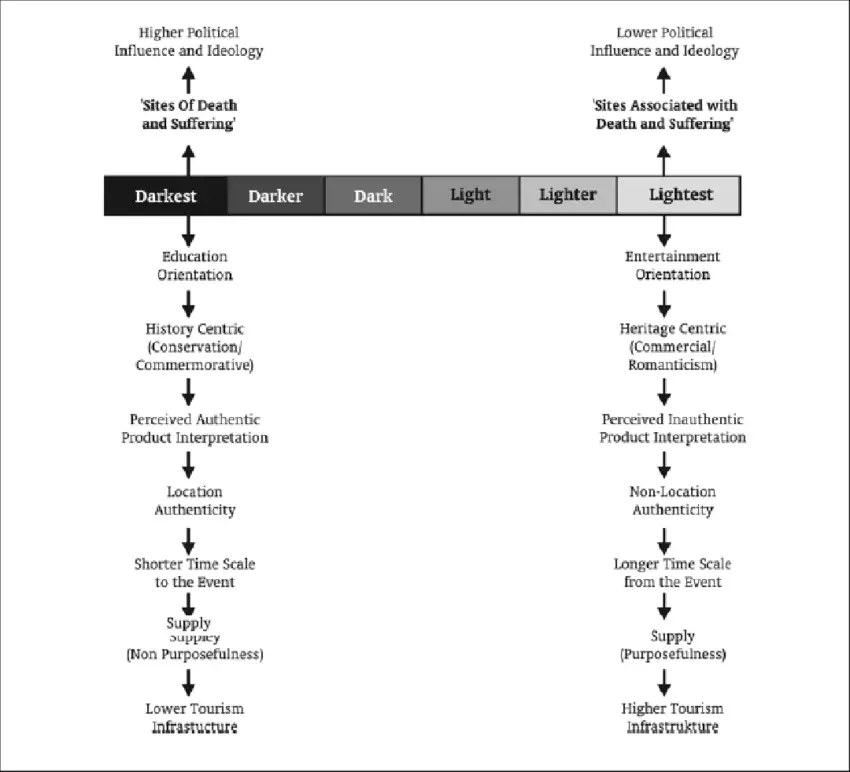

Dark tourism encompasses many different ‘dark’ activities. These can range from visiting an attraction such as the London Dungeons, where people are seen laughing and joking (did you know it finishes with a height-restricted ride that imitates people being hung!?), to tourists racing to the scenes of a disaster to provide help and relief. Naturally these are two very different ends of the dark tourism spectrum.

To help us understand the dark tourism sector better, we can organise activities according to the dark tourism spectrum.

On one end of the spectrum (the darkest end) we have extreme or serious dark tourism activities. These are activities which often involve an educational element, such as learning about a Nuclear disaster or a ship wreck. Activities on this end of the scale are associated with an authentic experience, whereby the tourist visits an actual historical site or speaks with people who were involved. Examples might include visiting the Berlin Wall or Tuol Sleng and the Killing Fields in Cambodia.

On the other end of the spectrum, activities tend to be of a more commercial nature. A Jack the Ripper themed funfair ride or a comical play based around the Black Plague are effectively romanticised versions of dark events or times in history. The intention is for the tourist to have fun and enjoy themselves, rather than to be educated about said historical reference.

The question is, why is dark tourism so popular? Why do we choose to visit places of death and tragedy? What is it that attracts us to such sorrow?

For many, it is purely the possibility of being able to emotionally absorb oneself in a place of tragedy. It is important for people to engage and immerse themselves in past history and culture . By visiting dark tourism sites, we are able to give ourselves time to reflect on history.

Dark tourism has close ties with educational tourism. Particularly in cases of darkest/darker tourism. For many people, this is a dominant, if not their main, motivation for being a dark tourist. Whilst dark tourism may not be a happy leisure experience, many people enjoy the educational aspect that comes with it. I know that I have certainly enjoyed visiting famous cemeteries and learning more about WW2 during my travels to Berlin and Poland .

Visitors of dark tourism sites are from a wide socio-demographic group. Motivations stem from educational purposes, the desire to understand past affairs, etc. Whilst other motivations stem from the desire to experience something different or new.

I recently watched a series on Netflix called The Dark Tourist. In this show, journalist David Farrier focuses on dark tourism and tourist behaviour towards popular dark tourism sites that are historically associated with death and/or tragedy.

In each episode, David travels to a different dark tourism destination. Some of these sites I have visited before and others I have now added to my bucket list. If you’re interested in learning more about dark tourism attractions around the world then this is a great show to watch!

If reading is more your thing, there are also a couple of really great books on dark tourism. Two of my favourites are Don’t Go There: From Chernobyl to North Korea—one man’s quest to lose himself and find everyone else in the world’s strangest places and The Dark Tourist: Sightseeing in the world’s most unlikely holiday destinations. Both books are comical repertoires of the authors’ adventures and mishaps when visiting dark tourism attractions around the world. This makes for some great like, leisurely reading over a glass of wine or a cup of tea!

Types of dark tourism

According to Stone (2006), there are seven main types of dark tourism sites.

Fun factories are essentially play centres. Whilst these are usually associated with children, they can also be aimed at adults. There are, for example, escape rooms which evolve around a dark theme, zombie chases or theatrical activities that all take place in dark fun factories.

There are many different dark exhibitions throughout the world. I visited several during my travels to Berlin that were focussed on the Holocaust. I visited exhibitions on the Khmer Rouge Regime in Cambodia. I have been to exhibitions about the Vietnam War and many more.

Dark exhibitions are a good opportunity for tourists to learn about the dark histories or events of a destination in a respectful way.

Many destinations open their historical dungeons for public viewing. These may be in their original state or they may have been altered for tours. The London Dungeons, for example, have become rather ‘Disneyfied’, in the way that they encompass live actors, sensory activities and rides.

There are some really interesting cemeteries that I have visited throughout the world. Whilst visiting a graveyard might not be at the top of every tourists list, you might be surprised at just how busy these places can be! Some famous cemeteries that I have visited include the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, the Recoleta Cemetery in Argentina and Lenin’s Mausoleum in Moscow. Did you know the Taj Mahal is also a dark resting place? Yep, I’ve been there too.

There are many shrines throughout the world which are popular tourist attractions, perhaps the most famous being the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. Shrines are especially popular in Asian countries.

Sites of conflict often become dark tourism sites once peace has been restored and a reasonable period of time has passed. One of the most interesting conflict sites that I have visited was Vietnam, where I learned all about the Vietnam War. The D-Day Beaches in France were also very interesting.

There are several areas of genocide which are popular with tourists. Whilst this is obviously a sad history, many people choose to visit sites such as Auschwitz or Karaganda, Kazakhstan to learn more about the history.

I think that Stone has missed out a key type of dark tourism in his list- disaster sites- so I will add this in below.

Disaster sites, whether in the immediate aftermath or after some time has passed, are popular with dark tourists. A subset of dark tourism, disaster tourism has increased in popularity in recent years. The recent documentary on Chernobyl, which was ranked the most highly user rated TV series ever, has helped raise awareness of disaster tourism amongst the public and tourism to this area has since increased significantly. I have written a detailed post on this topic, you can click here to read it: Disaster tourism: What, why and where .

There are a variety of types of disaster tourism that falls under the pillar of dark tourism, which include:

- Holocaust tourism

- Disaster tourism

- Grave tourism

- Cold war tourism

- Nuclear tourism

- Prison and persecution site tourism

Whilst each of these concepts are a type of tourism in their own right, they do share many similarities and are therefore classified together under the umbrella term of dark tourism.

So, is it really ethical to visit sites of death and tragedy? Or to photograph those who continue to sorrow for all that is lost? Or to take a selfie in a site of sadness? Many people do indeed question the ethics of taking part in dark tourism.

Take the response to the recent influx of Instagram photos taken in Chernobyl, for instance. There has been outrage, as shown in this newspaper article , at so-called ‘influencers’ and their inappropriate photographs taken at the historical nuclear site, where people have dressed up as scientists or posed in their underwear.

Whilst I think that most of us would agree that this is not sustainable tourist behaviour , there are a range of views as to what is appropriate and what is not when taking part in dark tourism.

As a general guide, however, here is a list of some of the behaviours demonstrated by dark tourists, which have been deemed offensive or inappropriate:

- Photographing people in moments of sorrow

- Smiling and laughing around those experiencing hardship

- Treating people as if they are museum exhibits

- Making inappropriate remarks

- Wearing disrespectful clothes

- Using inappropriate language

- Committing to disaster tourism for personal gain (e.g. personal satisfaction, to enhance CV etc)

- Making money from others’ hardships

- Talking loudly about unrelated issues

- Showing general signs of disrespect

Dark tourism destinations

There are a wide range of disaster tourism destinations (more than one would have imagined!), many of which would be overlooked as a dark tourism destination.

Below I have listed a few examples of dark tourism destinations, all of which demonstrate the different types of dark tourism as listed above.

Following the largest and most deadly Nazi concentration camp, Auschwitz was turned into a memorial after the end of WWII. Auschwitz has been deemed the very epitome of all dark tourism.

Today, the memorial site is estimated to have welcomed almost 50 million tourists over its time. The tourist numbers have, in fact, become so high in recent years that the government have limited how many tickets to the area can be sold to tourists each day. I was caught out by this on my trip there a couple of years ago so my tip is to book ahead!

Chernobyl has been regarded as one of the worst nuclear disasters in History and I learnt a lot about this when I watched the recent documentary that was shown on TV.

Chernobyl is a very popular destination for dark tourism, however unlike Auschwitz, this destination remains a hazard and is to date a dangerous site to visit due to the radiation levels still pertinent.

It is interesting to read in a recent article published this month that booking numbers have increased by 30% in the last 3 months following the recent tv series on the disaster.

Hiroshima preserves the memory of the worlds first nuclear attack. An atomic bomb at Hiroshima killed more people in one instant than any other killing in history.

Hiroshima continues to promote itself as a symbol of peace rather than that of a devastated city.

In 2016, the number of visitors reached over 12 million. Over 11 million were domestic tourists , 323,000 were students on school trips, and 1,176,000 were international visitors.

Following one of the worlds worst terrorist attacks, the 9/11 memorial site is one of the world’s top dark tourism attractions and is one of the most visited sites of any kind.

Within the first 2 years of the memorial opening, over 10 million visitors arrived and a couple years later the total figure rose to over 23 million.

The Killing Fields are a collection of (more than 300) sites in Cambodia where over a million people were killed and buried by the Khmer Rouge regime.

This is a popular tourism attractions and often considered a ‘right of passage’ when backpacking around South East Asia. It is an educational and sorrowful site, highlighting an important time in Cambodia’s history.

One recent article has expressed the issues faced with the high volume of tourists visiting the Killing Fields. This is due to the number of tourists ‘leaving their mark’ and graffiting on prison walls.

Bikini Atoll is associated mainly with the nuclear testing programme that the United States of America conducted.

Unlike natural disasters, tourists could not flock to Bikini Atoll immediately after, and even to this day, Bikini Atoll remains an extremely hazardous place to visit despite the US granting its safety in 1997.

It is argued that disaster tourists are putting themselves at risk by travelling to Bikini Atoll. There is still a significant level of radiation in the area and the extent of the damage caused below sea level has not been determined.

This particular disaster is categorised as nuclear tourism under the umbrella of dark tourism.

Berlin was the capital of the socialist single party regime of the former GDR. Now it is referred to the as ‘fall of the Berlin Wall’.

Berlin is home to a number of Holocaust and WW2 exhibitions and is popular with educational tourists. I took a student group there a few years ago and I would definitely recommend it for anybody studying tourism or history.

There are other countries that similar experiences too, including dark tourism in Vienna .

Robben Island can be observed as a form of Prison and persecution site tourism. In fact the prison has been recognised and preserved as a UNWTO World Heritage Site.

Prior to its conservation, the Island was a standing prison during the colonial wars, particularly dominante by successive colonial powers (Dutch and British).

Nowadays, the prison is a tourist site welcoming thousands of tourists each year. The tour guides are mostly ex-inmates, providing the tourist with an authentic account of what the prison was like when it was in operation as well as a much needed source of employment for the staff member.

We visited during our trip to South Africa and found it very interesting and educational. I learnt a lot about Nelson Mandela and the history of Apartheid.

Rwanda is a small country in Central Africa and the place where one of the most tragic and largest genocides took place in 1994.

This is now a dark tourism site which is visited by many tourists each year.

One of the most interesting and unusual dark tourism sites that I have visited is Oradur Sur Glane .

In 1944, 642 villagers were massacred in Oradur Sur Glane. Shortly after the war, General Charles de Gaulle declared Oradour should never be rebuilt and instead it should remain a stark memorial to Nazi cruelty. It is fascinating (and eerie) because everything remains untouched to this day.

Have you ever watched the film Pompeii’?, If so then you will know exactly the history behind the city and what happened.

Pompeii has received an enormous amount of visitors and this may be the result of its publicity following its recent film. Before the film was released, Pompeii was attracted on average 2 million visitors annually, a number that remained very steady from 2002 onwards. However, following the release of the film, tourist numbers staggered upwards reaching over 3.5 million.

Another place that I have visited that was particularly memorable was the bone church known as Sedlec Ossuary.

We took a day trip from Prague to visit this unusual attraction, which was eerie and fascinating at the same time!

You can find out a bit more about the bone church in this video.

South of Mexico City, Don Julian Santana begun to hang dolls from treess and buildings as a protection against evil spirits. Today, the Island is known as ‘Island of the Dolls’. Dubbed as the ‘scariest place in Mexico’, it has now become a popular attraction with thrill-seeking dark tourists.

However, it has come to recent attention that the Island has been duplicated to fool tourists into believing they are visiting the original Island.

Now that we know a bit more about the concept of dark tourism, lets summarise the key points:

- Dark tourism involves visiting places associated with death, tragedy, and suffering.

- Dark tourism is a controversial form of tourism that raises ethical concerns.

Dark tourism has been around for centuries, but the term “dark tourism” was only coined in the 1990s.

- Some of the most popular dark tourism destinations include Auschwitz, Ground Zero, and the Killing Fields in Cambodia.

- Dark tourism can be educational and help people understand and appreciate history.

- Dark tourism can also be seen as exploitative and disrespectful to the victims and their families.

- Responsible tourism practices should be followed when engaging in dark tourism.

- The motivations for engaging in dark tourism vary, including curiosity, historical interest, and a desire to pay respects to the victims.

- Dark tourism can have positive economic impacts on local communities.

- Overall, dark tourism is a complex and nuanced form of tourism that requires careful consideration and reflection.

Lastly, lets finish off this article by answering some of the most commonly asked questions on this topic.

Dark tourism refers to travel to places that are associated with death, tragedy, and suffering.

What are some examples of dark tourism destinations?

Examples of dark tourism destinations include Auschwitz, Ground Zero, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, and the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone.

Is dark tourism ethical?

The ethics of dark tourism are debated. Some people argue that it can be educational and help preserve historical memory, while others believe that it can be exploitative and disrespectful to the victims and their families.

What are some of the motivations for engaging in dark tourism?

Some people are motivated by curiosity, historical interest, a desire to pay respects to the victims, or a desire to challenge their own perceptions and beliefs.

Are there any risks associated with dark tourism?

Some dark tourism destinations may have physical or psychological risks, such as exposure to radiation or disturbing images.

How can I engage in responsible dark tourism?

Responsible dark tourism involves being respectful of the victims and their families, supporting local communities, and being aware of the impact of your visit.

Is dark tourism a new phenomenon?

Can dark tourism be beneficial for local economies?

Yes, dark tourism can bring economic benefits to local communities through increased tourism and job opportunities.

Can dark tourism be educational?

Yes, dark tourism can be educational and help people understand and appreciate history and its impact on society.

Should children be allowed to engage in dark tourism?

Whether children should be allowed to engage in dark tourism depends on the age of the child and the destination being visited. Parents should carefully consider the potential risks and impact on the child’s emotional well-being.

Dark tourism is an interesting concept that has reaped increased attention from both academics and the public in recent years. Whether you are visiting a cemetery, taking part in a zombie race or providing relief after a natural disaster, the opportunities to take part in dark tourism activities are far ranging.

It is fairly clear that there are a number of different types of tourism that all fall under the umbrella of dark tourism. And with the different types of dark tourism, comes a variety of different tourist motivations to visit.

However, despite the different motivations, there are still unresolved ethical concerns that need addressing. From inappropriate selfies to taking photos of people who are grieving, there are differing opinions on whether dark tourism is right or wrong.

If you enjoyed this article, I am sure you will love these too:

- What Sustainable Tourism Is + Why It Is The Most Important Consideration Right Now

- The Shocking Truth About Sex tourism

- What is sports tourism and why it is so big?

- What is responsible tourism and why does it matter?

- What is ethical tourism and why is it important?

Liked this article? Click to share!

Dark Tourist

Hasanthika sirisena.

184 pp. 5.5 x 8.5 6 b&w illus. Pub Date: December, 2021

Subjects: Creative Nonfiction

Series: 21st Century Essays

Imprint: Mad Creek

- Book Description

- About the Author

- Table of Contents

Finalist for the 2022 LAMBDA literary award in bisexual nonfiction

Winner of the 2021 Gournay Prize .

“Sirisena’s searching spirit leaves readers with plenty to dig into.” — Publishers Weekly

Read an excerpt from the book on Lit Hub .

“Hasanthika Sirisena does what I love most as a reader of nonfiction—she challenges, disrupts, and reinvents the form. This astute book knits seemingly disparate events of the personal, political, and cultural persuasion into a cohesive quilt. An insightful storyteller who examines disability, queerness, her Sinhalese roots, as well as ‘great love under duress,’ Sirisena is also a critic at heart who scrupulously dissects political upheaval.” —Anjali Enjeti, The Millions

“Intuitively arranged. …The complexity and breadth of Dark Tourist complements Sirisena’s own take on meaning-making and art. … [It] works as a collection not because of its tight cohesion but because of its moments of rupture and surprise.” —Ilana Masad, BOMB

“Shimmers with honesty, vulnerability, and circumspection.”— Kirkus

“The essays of Dark Tourist ring with depth and unexpected associations, and Hasanthika Sirisena writes them as if her life depended on it. With an insistent and probing style, she examines art and illness, exclusion and familial bonds, violence and pride, teasing out the many ways these subjects ricochet off one another over the course of a well-observed life.” —Elena Passarello, author of Animals Strike Curious Poses

“ Amidst the contexts of immigration, war, illness, and the comforts to be found in art, Sirisena invites us to pay closer attention to what we see and admire. These brilliant pieces offer portraits of courage for those whose ambitions have been sobered by grief. With lyricism and wit, Sirisena’s voice resounds with piercing beauty.” —Wendy S. Walters, author of Multiply/Divide: On the American Real and Surreal

Dark tourism—visiting sites of war, violence, and other traumas experienced by others— takes different forms in Hasanthika Sirisena’s stunning excavation of the unexpected places (and ways) in which personal identity and the riptides of history meet. The 1961 plane crash that left a nuclear warhead buried near her North Carolina hometown, juxtaposed with reflections on her father’s stroke. A visit to Jaffna in Sri Lanka—the country of her birth, yet where she is unmistakably a foreigner—to view sites from the recent civil war, already layered over with the narratives of the victors. A fraught memory of her time as a young art student in Chicago that is uneasily foundational to her bisexual, queer identity today. The ways that life-changing impairments following a severe eye injury have shaped her thinking about disability and self-worth.

Deftly blending reportage, cultural criticism, and memoir, Sirisena pieces together facets of her own sometimes-fractured self to find wider resonances with the human universals of love, sex, family, and art—and with language’s ability to both fail and save us. Dark Tourist becomes then about finding a home, if not in the world, at least within the limitless expanse of the page.

Hasanthika Sirisena (she/they) is a writer and cartoonist and a faculty member at the Vermont College of Fine Arts. She is the author of the short story collection The Other One .

Acknowledgments

Part I Loss . . .

Broken Arrow

In the Presence of God I Make This Vow

Pretty Girl Murdered

Confessions of a Dark Tourist

Abecedarian for the Abeyance of Loss

Amblyopia: A Medical History

Part II . . . and Recovery

Soft Target

The Answer Key

Six Drawing Lessons

Punctum, Studium, and The Beatles’ “A Day in the Life”

Related Titles:

How to Make a Slave and Other Essays

Jerald Walker

On Our Way Home from the Revolution

Reflections on Ukraine

Sonya Bilocerkowycz

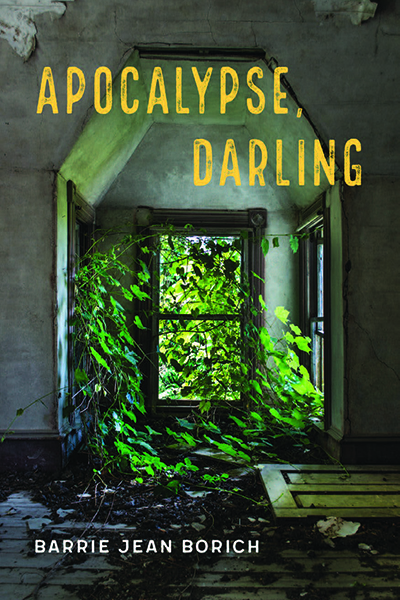

Apocalypse, Darling

Barrie Jean Borich

Dark tourism: motivations and visit intentions of tourists

International Hospitality Review

ISSN : 2516-8142

Article publication date: 8 July 2021

Issue publication date: 14 June 2022

The overall purpose of this study is to utilize the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) in combination with four dark tourism constructs (dark experience, engaging entertainment, unique learning experience, and casual interest) to gain a better understanding of behaviors and intentions of tourists who have visited or plan to visit a dark tourism location.

Design/methodology/approach

A total of 1,068 useable questionnaires was collected via Qualtrics Panels for analysis purposes. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was used to verify satisfactory reliability and validity regarding the measurement of model fit. With adequate model fit, structural equation modeling was employed to determine positive and negative relationships between TPB and dark tourism constructs. In all, 11 hypotheses statements were tested within this study.

Results of this study indicate that tourists are curious, interested, and intrigued by dark experiences with paranormal activity, resulting in travel choices made for themselves based on personal beliefs and preferences, with minimal outside influence from others. It was determined that dark experience was the most influential of the dark tourism constructs tested in relationship to attitudes and subjective norm.

Research limitations/implications

The data collected for this study were collected using Qualtrics Panels with self-reporting participants. The actual destination visited by survey participants was also not factored into the results of this research study.

Originality/value

This study provides a new theoretical research model that merges TPB and dark tourism constructs and established that there is a relationship between TPB constructs and dark tourism.

Dark tourism

- Thanatourism

- Motivations

- Theory of planned behaviour

Lewis, H. , Schrier, T. and Xu, S. (2022), "Dark tourism: motivations and visit intentions of tourists", International Hospitality Review , Vol. 36 No. 1, pp. 107-123. https://doi.org/10.1108/IHR-01-2021-0004

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Heather Lewis, Thomas Schrier and Shuangyu Xu

Published in International Hospitality Review . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Introduction

Dark tourism is defined as the act of tourists traveling to sites of death, tragedy, and suffering ( Foley and Lennon, 1996 ). This past decade marks a significant growth of dark tourism with increasing number of dark tourists ( Lennon and Foley, 2000 ; Martini and Buda, 2018 ). More than 2.1 million tourists visited Auschwitz Memorial in 2018 (visitor numbers, 2019), and 3.2 million tourists visited the Ground Zero 9/11 Memorial annually (a year in review, 2017). Despite of the increasing popularity, there is still limited understanding of dark tourism as a multi-faceted phenomenon ( Biran et al. , 2011 ) . Some research has looked into the motivations and experience of dark tourists ( Poria et al. , 2004 ; Poria et al. , 2006 ). However, most were based on conceptual frameworks and arguments with little empirical data, even less have examined tourist visit intentions to dark tourism sites ( Zhang et al. , 2016 ), let alone the association between dark tourists' motivations and visit intentions. Many scholars suggested the pressing needs for empirical research into dark tourism from tourist perspectives to understand their motivations and experiences ( Seaton and Lennon, 2004 ; Sharpley and Stone, 2009 ; Zhang et al. , 2016 ). Of the limited empirical dark tourism studies, most were case studies with historical battlefields and concentration camps being the hot spots ( Le and Pearce, 2011 ; Lennon and Foley, 1999 ; Miles, 2002 ). Still, a comprehensive understanding of dark tourists' motivations and their intentions to visit is lacking.

As such, this study was conducted to understand both the motivations and visit intentions of tourists to dark tourism destinations. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) constructs ( attitudes, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control) and the four dark tourism dimensions (i.e. dark experience, engaging entertainment, unique learning experience, and casual interest ) were utilized to address the following objectives: (1) examine the motivations of dark tourists; (2) investigate the intentions of the dark tourists to visit a dark tourism destination in the next 12 months; and (3) explore the association between the motivations and visit intentions of dark tourists. The dark tourism dimensions utilized for this study were adapted supported by previous dark tourism studies ( Biran et al. , 2014 ; Bissell, 2009 ; Lam and Hsu, 2006 ; Molle and Bader, 2014 ). While many studies have utilized TPB in the past, this study will utilize the TPB to focus attention on why travelers are motivated to visit dark tourism locations specifically.

Literature review

Travels associated with death dates back for centuries ( Dale and Robinson, 2011 ). Early examples of dark tourism include Roman gladiator games, guided tours to watch hangings in England, and pilgrimages to medieval executions ( Stone, 2006 ). Even today, many tourists are fascinated with and thus visited sites of death and tragedy such as the John F. Kennedy's death site in Dallas, Texas, and the Ground Zero 9/11 Memorial in New York ( Foley and Lennon, 1996 ; Strange and Kempa, 2003 ). Abandoned prisons and sites of punishment and incarcerations are also popular attractions among dark tourists (e.g., Pentridge in Melbourne, Australia; Foley and Lennon, 1996 ). However, the term dark tourism did not get introduced to the research community until 1996 which ignited many later research efforts on this topic ( Light, 2017 ).

Dark tourism is defined as the act of tourists traveling to sites of death, tragedy, and suffering ( Foley and Lennon, 1996 ). Many scholars also came up with other terms and labels to describe such phenomenon including thanatourism ( Seaton, 1996 ), disaster tourism ( Rojek, 1993 ), black spot tourism ( Rojek, 1993 ), morbid tourism ( Blom, 2000 ) and even phoenix tourism ( Powell et al. , 2018 ). Mowatt and Chancellor (2011) suggested that despite of different names, at the heart of the concept is travel to places of death that are often linked to violence ( Robb, 2009 ). Many researchers use the term dark tourism and thanatourism interchangeably, while more tend to use dark tourism as an umbrella term for any form of tourism that is somehow related to death, suffering, atrocity, tragedy or crime ( Light, 2017 ). Given the standard use of the term dark tourism in the practice and scholarship of tourism, such a term will be used throughout this manuscript.

Dark tourism research in this past two decades mainly covers six themes including the discussion on definition, concepts, and typologies; the associated ethical issues; the political and ideological dimensions; the nature of demand for dark tourism locations; site management; and the methods used for research ( Light, 2017 ). The area of terminology and definitions undoubtedly dominates in the dark tourism literature ( Zhang et al. , 2016 ). While in the area of exploring the nature of demand for dark tourism locations, the relatively limited research concentrated in four aspects – both the motivations and experiences of dark tourists, the relationship between visiting and sense of identity, and new approaches to theorizing the consumption of dark tourism ( Light, 2017 ).

Research addressing dark tourists' motivations were relatively slow. Many early studies simply postulate and propose tourists' motivations to visit dark tourism sites, with a lack of empirical research to support ( Light, 2017 ). As such, many studies in the past decade examined dark tourists' motivations through different case studies, with concentration camps or historical battlefields being the hot spots ( Lennon and Foley, 1999 ; Miles, 2002 ). Research reveals that tourists visit dark tourism destinations for a wide variety of reasons, such as curiosity ( Biran et al. , 2014 ; Isaac and Cakmak, 2014 ), desire for education and learning about what happened at the site ( Kamber et al. , 2016 ; Yan et al. , 2016 ), interest in history or death ( Yankholmes and McKercher, 2015 ; Raine, 2013 ), connecting with one's personal or family heritage ( Mowatt and Chancellor, 2011 ; Le and Pearce, 2011 ). Drawing from literature, four common themes (i.e. dark experience, engaging entertainment, unique learning experience, casual interest) emerged, served as the foundational pillars for this study, and were discussed below.

The motivation construct

Dark experience.

Raine's (2013) dark tourist spectrum study of tourists visiting burial grounds and graveyards concluded that mourners and pilgrims had personal and spiritual connections to the different sites being studied. Mourners visited specific gravesites and usually would perform meditations for the dead. Pilgrims had a personal connection to specific burial sites in some way, whether it is a religious connection to the individual or they served as a personal hero ( Raine, 2013 ). Death rites are often performed as a ritual not necessarily to mark the passing of the deceased but rather to heal the wounds of families, communities, societies, and/or nations by the deceased's passing ( Bowman and Pezzullo, 2009 ).

Additionally, Raine's (2013) study discovered another subset of tourists—the morbidly curious and thrill seekers. Those classified as morbidly curious or thrill seekers were visiting burial sites to confront and experience death. Whether a mourner or pilgrim or the morbidly curious thrill seeker, the tourists had a strong connection to the dead they were there to visit which could categorize them as seeking a dark experience.

To take dark tourism to the extreme, Miller and Gonzalez (2013) completed a study on death tourism. Death tourism occurs when individuals travel to a location to end their lives, often through a means of assisted medical suicide. It was determined that this is still a taboo topic for some countries where it is not legalized, however it is gaining more publicity. It was determined that death tourism is typically the result of one of four reasons; the primary reason death tourism is planned is because of assisted suicide being illegal in the traveler's home country ( Miller and Gonzalez, 2013 ). While death tourism does not directly apply to this particular study, it is an offspring of dark tourism and is a tourist activity that is related to dark experience.

Dark Experience will have a positive relationship with Attitudes

Dark Experience will have a positive relationship with Subjective Norm

Engaging Entertainment

Engaging Entertainment will have a positive relationship with Attitudes

Engaging Entertainment will have a positive relationship with Subjective Norm

Unique learning experience

Unique Learning Experience will have a positive relationship with Attitudes

Unique Learning Experience will have a positive relationship with Subjective Norm

Casual interest

Casual Interest will have a positive relationship with Attitudes

Casual Interest will have a positive relationship with Subjective Norm

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

Behavioral intention, defined as an individual's anticipated or planned future behavior ( Swan, 1981 ), has been suggested as a central factor that correlates strongly with observed behavior ( Baloglu, 2000 ). Many believed that intentions serve as an immediate antecedent to actual behavior ( Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975 ; Konu and Laukkanen, 2010 ). Fishbein and Ajzen developed the Theory of planned behavior (TPB) base on three constructs: attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) has been widely used in tourism research ( Ajzen and Driver, 1992 ; Han et al. , 2010 ; Han and Kim, 2010 ; Lam and Hsu, 2004 , 2006 ). TPB suggests that individuals are more likely to engage in behaviors that are believed to be achievable ( Armitage and Conner, 2001 ). Ajzen (1991) suggested that attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control are important to predict intention. Perceived behavioral control is what influences the tourists' intentions and their perception of their ability to perform a specific behavior.

Lam and Hsu (2004) utilized the TPB to examine motivations of travelers from mainland China to Hong Kong and found that attitude, perceived behavioral control, and past behaviors were directly related to travel intentions. In another study examining the visit intentions of Taiwanese travelers to Hong Kong, Lam and Hsu (2006) found that a positive association between visit frequency and re-visit intention.

Cheng et al. (2006) used the TPB to examine the negative word-of-mouth communication on visit intentions of Chinese consumers to high-class Chinese restaurants. It was determined from their study that the TPB constructs were positively impacted by negative word-of-mouth indicating that the TPB effectively measured consumer communication intention. Similarly, Han and Kim (2010) modified the TPB in the investigation of customers' intention to revisit environmentally friendly hotels and found that past behavior was a significant predictor of intention–the more customers stay at a green hotel, the more likely they intend to revisit. It can be concluded from previous research efforts that the TPB can be utilized to effectively measure behavioral intentions of tourists successfully.

Motivation and intentions

Attitudes will have a positive relationship with Intention

Subjective Norm will have a negative relationship with Intention

Perceived Behavioral Control will have a positive relationship with Intention

Methodology

Survey instrument.

A survey questionnaire was developed to collect information on the socio-demographic background, motivation construct, and planned behavior construct from tourists. Socio-demographic data queried were age in years (continuous), gender (3 categories, male, female and prefer not to answer), level of education (9 categories, from less than high school degree to doctoral degree), marital status (5 categories, from single to widow/widower), personal annual income (12 categories, from less than $20,000 to more than $200,000). Tourists' home residence state and country were also collected.

A dark tourism motivation construct was developed based on previous studies ( Biran et al. , 2014 ; Bissell, 2009 ; Lam and Hsu, 2006 ; Molle and Bader, 2014 ), and used to query previous visit and potential visit separately using a five-point Likert scale (“1 = extremely unimportant”; “5 = extremely important”). This motivation construct consists of 33 item statements from four dimensions ( Table 1 ) which include engaging entertainment, dark experience , unique learning experience , and casual interest . Dark experience consisted of nine statements, related to death, fascination with abnormal and/or bizarre events and destinations, and emotional experiences with a connection to death (e.g., “to travel”, “to have some entertainment”). Engaging entertainment was measured using ten statements that inquire about the personal or emotional connection to the destination they have visited or wish to visit in the future (e.g., “to witness the act of death and dying”, “to experience paranormal activity”). Unique learning experience focused on learning about the history of the destination being visited or trying something that is different and out of the ordinary (eight items, e.g., “to try something new”, “to increase knowledge”). Casual interest focuses on individuals who want to visit a dark tourism destination for the entertainment value but want to have a relaxing time while doing so (six items, “special tour promotions”, “natural scenery”).

The planned behavior construct queried on four dimensions (i.e., attitudes , subjective norms , perceived behavioral control , and behavioral intentions ) associated with visiting dark tourism destinations, with a total of 16 item statements ( Table 2 ). Five item statements were used to measure dark tourists' attitudes (e.g., “visiting a dark tourism destination is enjoyable”, “visiting a dark tourism destination is pleasant”) and behavioral intentions (e.g., “I will visit a dark tourism destination in the next 12 months”, “I would revisit the most recent dark tourism destination I visited again in the future”) respectively, using a five-point Likert scale (“1 = Strongly disagree”; “5 = Strongly agree”). Dark tourists' perceived behavioral control was measured by three item statements (e.g., “I am in control of whether or not I visit a dark tourism destination”, “If wanted, I could easily afford to visit a dark tourism destination”), using the same five-point Likert scale (“1 = Strongly disagree”; “5 = Strongly agree”). For subjective norms dimension, each of the three item statements was measured by a different five-point Likert scale. The statement that “most people I know would choose a dark tourism destination for vacation purposes” uses the scale in which “1 = strongly disagree”, “5 = strongly agree”. One item statement asks individuals to rate on whether “people who are important to me think I ____ choose a dark tourism destination to visit” “1 = definitely should not”, “5 = definitely should”). Another statement asks individuals to rate whether “people who are important to me would ___ of my visit to a dark tourism destination” “1 = definitely disapprove”, “5 = definitely approve”).

Sampling and procedure

To increase the reliability and validity of the survey, a pilot study was conducted. A small group of industry professionals from all over the country currently working at dark tourism destinations and other academic researchers were invited to critique the initial draft of the survey. Forty-one individuals took the survey instrument and provided feedback (e.g., some wording issues). After revisions from the pilot study were completed, the survey was launched, and data was collected.

Qualtrics, a web-based survey software company with access to an electronic database of survey candidates, was used to administer this questionnaire to participants. A total of 44,270 invitations were randomly sent to Qualtrics panel participants requesting participation in this study. Qualification of participants was completed by requesting all survey recipients answer the following questions: (1) Have you visited a dark tourism location within the past 24 months? and (2) Do you plan to visit a dark tourism location within the next 12 months? A statement was provided to all participants explaining what consisted of a dark tourism location to ensure participants were not taking the survey based on experiences of activities like haunted houses or haunted hayrides. Only 3,907 individuals were eligible to complete the survey, and a total of 1,068 participants did complete the survey, which yields a response rate of 27.3%. Altogether 651 out of 1,068 individuals had previously visited a dark tourism destination within the last 24 months while the remaining 417 individuals plan to visit a dark tourism destination within the next 12 months.

Data analysis included descriptive statistics, reliability tests, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and structural equation modeling (SEM). Descriptive statistics were used to outline respondents' characteristics (e.g., demographic composition). CFA was utilized to evaluate the measurement model, demonstrate adequate model fit, and ensure satisfactory levels of reliability and validity of underlying variables and their respective factors. Factor loadings greater than 0.70 indicated that the constructs are appropriately represented and considered acceptable ( Hair et al. , 2010 ). Cronbach's alphas were computed to test the internal reliability of items comprising each dimension of the dark tourism motivation construct ( dark experience , engaging entertainment , unique learning experience , casual interest ) and the planned behavior construct ( attitudes , subjective norm , perceived behavioral control ), respectively. A cutoff value of 0.7 was utilized to determine “good” reliability ( Peterson, 1994 , p. 381).

To confirm measurement model validity, the chi-squared ( x 2 ) statistic, Root-Mean-Square-Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) values were reviewed. Cutoff criteria used to determine “good fit” were RMSEA score < 0.08 ( Byrne, 1998 ), CFI scores > 0.90 ( Kline, 2005 ), SRMR < 0.08 to indicate a good fit ( Hu and Bentler, 1999 ).

Overwhelmingly, many tourists who had either visited a dark tourism location or plan to visit a dark tourism destination were female (65.4%). Additionally, the majority of participants were 25–34 years of age (44.2%) with the next largest age groups being 35–44 years (21%) and 18–24 years (20.9%). Most had either a 4-years Bachelor's degree from college (30.5%) or at least some college education but did not finish their degree (25.3%). 54.5% of the survey participants were married and 37.6% were single. As for income, the largest percentage (19.5%) had an individual annual income ranging from $20,001-$40,000. A full table of demographic characteristics of the participants can be seen in Table 3 .

Partial disaggregation of measurement model

SEM was utilized to investigate the relationships among dark tourism construct, the planned behavior construct and behavioral intentions. Like the CFA testing, the SEM also uses the chi-squared ( x 2 ) , RMSEA, SRMR, and CFI to determine overall model fit and relationships for this study. After further testing for convergent and discriminant validity, it was determined that all constructs met the composite reliability 0.70 or greater standard regarding the 3-parcel hypothesized model ( Table 4 ) ( Hair et al. , 2010 ).

There are several ways to parcel variables into groupings. For purposes of this study, the variables were parceled using the item-to-construct method since the SEM model was large in size and the goal was to have parcels balanced in terms of difficulty and discrimination ( Little et al. , 2002 ). To develop the parcels, standardized regression weights were evaluated, and the three highest scores served as anchors to each of the three parcels with the highest values associated to parcel 1, next highest to parcel 2, and then the next highest to parcel 3. The remainder of variables were placed into the parcels continuing with the 4th highest value placed into the 3rd parcel and repeating the process in inverted order until all variables were assigned into parcels. Once the variables for each construct were placed into appropriate parcel groupings, averages of the questions associated to the new parceled variables were calculated prior to the CFA and SEM analysis. The attitude and behavioral intention constructs had five variable questions, while subjective norm and perceived behavioral control only had three questions. In those situations, one individual variable question served as the parcel item. Table 2 shows the variables and the parcels in which they were grouped.

Additionally, the average variance extracted was calculated and proved to be less than the composite reliability for each construct indicating convergent reliability of the constructs. The average variance extracted was greater than the 0.50 standard for Dark Experience, Engaging Entertainment, Unique Learning Experience, Attitude, and Subjective Norm constructs. Behavioral Intention (0.49) and Casual Interest (0.48) had values that were borderline acceptable regarding convergent validity. The only construct that did not meet the standards of convergent validity testing was Perceived Behavioral Control (0.23). When testing for divergent validity, all square-root of average variance extracted calculations were greater than the inter-construct correlations indicating divergent validity was present in this study. Partial disaggregation of the variables resulted in a much stronger overall model fit. The RMSEA value was 0.08 indicating a strong model fit and the CFI (0.891) value was acceptable indicating a good model fit. The SRMR value (0.06, Table 4 ) also showed a strong model fit.

Hypothesis testing

Overall, most of the relationships between the dark tourism construct and the TPB constructs were significant. Results show that dark experience has a positive significant relationship with both attitudes (0.434) regarding tourists visiting a dark tourism destination and subjective norms (0.242, Table 5 ). Casual interest has a positive significant relationship with both attitudes (0.404) and subjective norm (0.330). Both engaging entertainment (−0.080; −0.217) and unique learning experience (0.152; −0.247) are not significantly associated with neither attitudes nor subjective norms . Results show that both attitudes (0.396) and perceived behavioral control (0.716) have a significant positive relationship with behavioral intention .

SEM testing was completed on the data. In addition to the significant and insignificant relationships indicated by the SEM testing, to answer some of the specific research questions asked by this study one must review the distinct question factor loadings to get those answers. A full set of the factor loadings of survey questions asked regarding dark tourism and TPB constructs are in Table 1 . A visualization of all hypothesis testing results is in Table 5 as well as on Figure 1 .

It can be concluded from the findings of this research that dark experience has a positive relationship with attitudes regarding tourists visiting a dark tourism location, indicating that Hypothesis 1 was fully supported. Tourists seek specific characteristics when choosing to visit a dark tourism destination. Akin to findings from Bissell (2009) , the reasons for visiting: I want to try something new and out of the ordinary as well as I am fascinated with abnormal and bizarre events were strong. Alone these two variables do not constitute wanting to experience dark tourism but suggest a curiosity about dark tourism and a desire for new experiences ( Seaton and Lennon, 2004 ). Individuals answered favorably to all questions related to interest in experiencing paranormal activity. Although Sharpley (2005) suggested “fascination with death” as a potential motive for tourists to visit dark tourism destinations, questions specifically related to death (i.e., to witness the act of death and dying , to satisfy personal curiosity about how the victims died ) , reveal that fascination with death and dying was not a strong motivating factor for the tourists' who participated in this research study. The positive relationships of dark experience with attitudes ( H1 ) and subjective norm ( H2 ) , respectively, implies that tourists are seeking experiences that satisfy curiosity or they are seeking interaction with the paranormal. Tourists seek a fun and enjoyable tourist experience by visiting dark tourism destinations, and do not feel pressured by societal norms of their friends and family, which may prevent them from visiting dark tourism destinations.

The engaging entertainment dimension regarding both attitude ( H3 ) and subjective ( H4 ) was not supported in this study, which is interesting considering the questions in this dimension were developed to determine the importance of the tourists connecting with the information presented at the destination while still having an enjoyable experience.

Like Raine (2013) , this study considered the unique learning experience dimension to include individuals who are hobbyists and are typically visiting these destinations solely for educational purposes and to not engage with the destination as a dark tourism site. To present an alternative consideration to the construct of unique learning experience, Seaton (1996) determined that the more attached a person was to a destination, the less likely they would be fascinated with death, resulting in the tourists not viewing the dark tourism destination as being “dark”. This thought process may be a possibility of explanation for why the relationships were negative between unique learning experience and the TPB constructs, resulting in both Hypothesis 5 and 6 not being supported. Farmaki (2013) strengthens this argument by determining that many tourists visit museums for the purpose of education, but museums will incorporate the concept of death to enhance the tourist experience.

Results from this study also indicate that participants of this study were not traveling to dark tourism destinations for educational purposes. Additionally, results indicate that individuals who were perhaps traveling for the purposes of unique learning experience had negative feelings or experiences with subjective norms, lending to the belief that their family and friends were not supportive of their choice to visit a dark tourism destination.

Raine (2013) discovered a group of tourists she classified as sightseers and passive recreationalists. These tourists can be themed as “incidental” as they were likely not seeking a dark tourism destination related to death and burials, but instead were looking for a destination to escape from everyday life. These statements can easily be supported by this research study as Hypotheses 7 and 8 were both positively supported in relationship to casual interest and attitudes ( H7 ) and subjective norm ( H8 ). The questions asked in this study specifically relate to value of tours, special promotions, and enjoying time with friends and family.

Individuals were seeking attitudinal experiences through their visits to dark tourism destinations, supporting Hypothesis 9 . Unlike the results from Lam and Hsu (2004) , subjective norms do play a role in behavioral intentions. This study found that the influence of societal norms and pressures do influence tourists' intention to visit dark tourism destinations, lending to Hypothesis 10 not being supported as expected. Regarding perceived behavioral control, when tourists feel capable and in control of their tourism choices, it will positively impact their behavioral intention or likelihood of visiting a dark tourism destination, supporting Hypothesis 11 .

Practical implications

Practitioners working in tourism industries and communities of dark tourism destinations can greatly benefit from the results of this study. Managers of dark tourism destinations must realize that visitors are attracted to these locations for many different reasons ( Bissell, 2009 ) and not just for fascination of death or paranormal activity. While this research does not focus specifically on individual motivating factors that influence behavior to visit, overarching attributes were determined to influence behavioral intentions more than others. The significant positive relationships found in this study between dark experience, unique learning experience, and casual interest suggest dark tourism destination managers offer a variety of tours and services to visitors and should be sensitive in how they display or present information so it does not come across as being offensive to tourists in the event they have strong emotional ties to the destination or individual(s) who may have been a victim at the destination.

Due to the broad nature of this study and its data collection efforts, the dark tourism locations visited by participants varied greatly. It can be concluded from the data that the use of television and contemporary media featuring dark tourism locations does positively influence tourists' behavioral intention to visit. Variables related to dark tourism destinations featured on television shows were more strongly favored in relationship to the dark experience construct than engaging entertainment. This indicates that tourists are curious about what they have seen on television or mass media and want to experience similar. Managers of dark tourism destinations featured on television shows should effectively market their locations as such to increase interest and tourism traffic to their destination. If paranormal tours are not currently being offered this would be a recommendation (if applicable) to generate more tourism interest.

Additionally, due to the increased popularity and reliance on websites and social media platforms for information, practitioners should register their location on dark tourism websites and registries so more curious travelers can easily locate them. Utilizing TripAdvisor.com and other similar travel websites is another option for practitioners to generate tourism interest to their destination. Making information readily available and easy to locate for tourists will continue to strengthen the relationship between perceived behavioral control and behavioral intention. Additionally, considering societal norms had a positive relationship with dark tourism constructs within this study, practitioners could market their destination as being taboo to tourists wanting to satisfy their rebellious curiosity.

Limitations and future research

This study has several limitations. Since the data was collected using Qualtrics Panels, potential participants are asked to self-report and assess whether they are eligible dark tourists for this study, based on given definition of dark tourism. Such self-assessment may not always be precise. If adopting this survey method, future research may consider asking participations to provide the specific dark tourism destination type that they have visited in the past 24 months, to help further confirm their eligibility for study participation. It is also recommended that if time and resources permit, future research consider collecting data on-site at dark tourism destinations. Also, this research study did not take into consideration the type of dark tourism destination visited by the respondents. Dark tourism destinations vary in the levels of violence and death that are associated with them ( Seaton, 1996 ; Stone, 2006 ). Future research can investigate additional motivational factors of tourists to visit dark tourism destinations with varying levels of darkness associated to them.

Most of the previous studies are case studies with historical battlefields and concentration camps being the hot spot for tourist activity. It is important and yet lacking to explore the general pattern of the association between motivations and visit intentions to dark tourism sites in general. Ryan and Kohli (2006) suggested there are differences between dark tourism destinations created by natural disasters (e.g., earthquakes in Sichuan, China; Biran et al. , 2014 ) and those that were sites of death at the hand of man (e.g., Auschwitz concentration camp). Moreover, Zhang et al. (2016) were among the few that explored the associated between motivation and association, but only on college students at one specific site. Although this study is inclusive of different dark tourist groups and dark tourism sites, future research may consider factoring in such difference in dark tourism destinations while exploring dark tourist motivations and visit intensions.

Conclusions

This study serves as exploratory research examining the association between tourist motivations and visit intentions and paves the way for future research in dark tourism. This study contributes to the dark tourism literature by proposing a new theoretical framework linking and extending dark tourism motivation construct with the Planned Behavior Construct. Study results can also benefit practitioners in dark tourism sector.

Graphic representation of theoretical framework and hypothesis testing results

Factor loadings for dark tourism variables

Partial disaggregation parcel groupings of TPB variables

Demographic characteristics of survey participants

CFAs of nested models

Full-data set hypothesis testing results

Ajzen , I. ( 1991 ), “ The theory of planned behavior ”, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , Vol. 50 , pp. 179 - 211 .

Ajzen , I. and Driver , B.L. ( 1992 ), “ Application of the theory of planned behavior to leisure choice ”, Journal of Leisure Research , Vol. 24 No. 3 , pp. 207 - 224 .

Alegre , J. and Cladera , M. ( 2009 ), “ Analysing the effect of satisfaction and previous visits on tourist intentions to return ”, European Journal of Marketing , Vol. 43 Nos 5-6 , pp. 670 - 685 , doi: 10.1108/03090560910946990 .

Armitage , C.J. and Conner , M. ( 2001 ), “ Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analytic review ”, British Journal of Social Psychology , Vol. 40 , pp. 471 - 499 .

Baloglu , S. ( 2000 ), “ A path analytic model of visitation intention involving information sources, socio-psychological motivations, and destination image ”, Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing , Vol. 8 No. 3 , pp. 81 - 90 , doi: 10.1300/j073v08n03_05 .

Biran , A. , Poria , Y. and Oren , G. ( 2011 ), “ Sought experiences at dark heritage sites ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 38 , pp. 820 - 841 , doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2010.12.001 .

Biran , A. , Liu , W. , Li , G. and Eichhorn , V. ( 2014 ), “ Consuming post-disaster destinations: the case of Sichuan, China ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 47 , pp. 1 - 17 .

Bissell , L.J. ( 2009 ), Understanding Motivation and Perception at Two Dark Tourism Attractions in Winnipeg, MB , Thesis , University of Manitoba , Print .

Blom , T. ( 2000 ), “ Morbid tourism: a postmodern market niche with an example from Althorp ”, Norsk-Geografisk Tidsskrift--Norwegian Journal of Geography , Vol. 54 No. 1 , pp. 29 - 36 .

Bowman , M. and Pezzullo , P. ( 2009 ), “ What's so ‘dark’ about dark tourism?: death, tours, and performance ”, Tourist Studies , Vol. 9 No. 3 , pp. 187 - 202 .

Byrne , B.M. ( 1998 ), Structural Equation Modeling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming , Lawrence Erlbaum , Mahwah, NJ .

Cheng , S. , Lam , T. and Hsu , C. ( 2006 ), “ Negative word-of-mouth communication intention: an application of the theory of planned behavior ”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research , Vol. 30 No. 1 , pp. 95 - 116 .

Conner , M. and Abraham , C. ( 2001 ), “ Conscientiousness and the theory of planned behavior: toward a more complete model of the antecedents of intentions and behavior ”, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , Vol. 27 No. 11 , pp. 1547 - 1561 , doi: 10.1177/01461672012711014 .

Crompton , J.L. ( 1979 ), “ Motivations for pleasure vacation ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 6 No. 4 , pp. 408 - 424 .

Dale , C. and Robinson , N. ( 2011 ), “ Research themes for tourism ”, Dark Tourism , CABI , pp. 205 - 2017 .

Farmaki , A. ( 2013 ), “ Dark tourism revisited: a supply/demand conceptualisation ”, International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research , Vol. 7 No. 3 , pp. 281 - 292 .

Fishbein , M. and Ajzen , I. ( 1975 ), Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research , Addison-Wesley , Reading, MA .

Foley , M. and Lennon , J. ( 1996 ), “ JFK and dark tourism: a fascination with assassination ”, International Journal of Heritage Studies , Vol. 2 No. 4 , pp. 198 - 211 .

Hair , J.F. , Black , W.C. , Babin , B.J. and Anderson , R.E. ( 2010 ), Multivariate Data Analysis , 7th ed. , Prentice Hall , Upper Saddle River, NJ .

Han , H. and Kim , Y. ( 2010 ), “ An investigation of green hotel customers' decision formation: developing an extended model of the theory of planned behavior ”, International Journal of Hospitality Management , Vol. 29 , pp. 659 - 668 .

Han , H. , Hsu , L. and Sheu , C. ( 2010 ), “ Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to green hotel choice: testing the effect of environmental friendly activities ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 31 , pp. 325 - 334 .

Hu , L. and Bentler , P.M. ( 1999 ), “ Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis conventional criteria versus new alternatives ”, Structural Equation Modeling , Vol. 6 , pp. 1 - 55 .

Isaac , R.K. and Çakmak , E. ( 2014 ), “ Understanding visitor's motivation at sites of death and disaster: the case of former transit camp Westerbork, The Netherlands ”, Current Issues in Tourism , Vol. 17 No. 2 , pp. 164 - 179 , doi: 10.1080/13683500.2013.776021 .

Kamber , M. , Karafotias , T. and Tsitoura , T. ( 2016 ), “ Dark heritage tourism and the Sarajevo siege ”, Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change , Vol. 14 No. 3 , pp. 255 - 269 , doi: 10.1080/14766825.2016.1169346 .

Kline , R.B. ( 2005 ), Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling , 2nd ed. , Guilford Publications .

Kim , Y.H. , Kim , M. and Goh , B.K. ( 2011 ), “ An examination of food tourist’s behavior: using the modified theory of reasoned action ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 32 , pp. 1159 - 1165 .

Konu , H. and Laukkanen , T. ( 2010 ), “ Predictors of tourists’ wellbeing holiday intentions in Finland ”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management , Vol. 17 No. 1 , pp. 144 - 149 , doi: 10.1375/JHTM.17.1.144 .

Lam , T. and Hsu , C. ( 2004 ), “ Theory of planned behavior: potential travelers from China ”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research , Vol. 28 No. 4 , pp. 463 - 482 .

Lam , T. and Hsu , C. ( 2006 ), “ Predicting behavioral intention of choosing a travel destination ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 27 , pp. 589 - 599 .

Le , D.T. and Pearce , D.G. ( 2011 ), “ Segmenting visitors to battlefield sites: international visitors to the former demilitarized zone in Vietnam ”, Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing , Vol. 28 No. 4 , pp. 451 - 463 , doi: 10.1080/10548408.2011.571583 .

Lennon , J. and Foley , M. ( 1999 ), “ Interpretation of the unimaginable: the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C. and ‘dark tourism’ ”, Journal of Travel Research , Vol. 38 , pp. 46 - 50 .

Lennon , J. and Foley , M. ( 2000 ), Dark Tourism: The Attraction of Death and Disaster , Cengage Learning EMEA , Andover, Hampshire .

Light , D. ( 2017 ), “ Progress in dark tourism and thanatourism research: an uneasy relationship with heritage tourism ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 61 , pp. 275 - 301 , doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.01.011 .

Little , T.D. , Cunningham , W.A. and Shahar , G. ( 2002 ), “ To parcel or not to parcel: exploring the question, weighing the merits ”, Structural Equation Modeling , Vol. 9 No. 2 , pp. 151 - 173 .

Martini , A. and Buda , D.M. ( 2018 ), “ Dark tourism and affect: framing places of death and disaster ”, Current Issues in Tourism , Vol. 23 No. 6 , pp. 679 - 692 , doi: 10.1080/13683500.2018.1518972 .

Miles , W. ( 2002 ), “ Auschwitz: museum interpretation and darker tourism ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 29 No. 4 , pp. 1175 - 1178 .

Miller , D. and Gonzalez , C. ( 2013 ), “ When death is the destination: the business of death-tourism--despite legal and social implications ”, International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research , Vol. 7 No. 3 , pp. 293 - 306 .

Molle , A. and Bader , C. ( 2014 ), “ Paranormal science from America to Italy: a case of cultural homogenisation ”, The Ashgate Research Companion to Paranormal Cultures , Ashgate , London , pp. 121 - 138 .

Mowatt , R.A. and Chancellor , C.H. ( 2011 ), “ Visiting death and life ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 38 No. 4 , pp. 1410 - 1434 , doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2011.03.012 .

Peterson , R.A. ( 1994 ), “ A meta-analysis of Cronbach's coefficient alpha ”, Journal of Consumer Research , Vol. 21 No. 2 , pp. 381 - 391 .

Poria , Y. , Butler , R. and Airey , D. ( 2004 ), “ Links between tourists, heritage, and reasons for visiting heritage sites ”, Journal of Travel Research , Vol. 43 , pp. 19 - 28 .

Poria , Y. , Reichel , A. and Biran , A. ( 2006 ), “ Heritage site perceptions and motivations to visit ”, Journal of Travel Research , Vol. 44 , pp. 318 - 326 .

Powell , R. , Kennell , J. and Barton , C. ( 2018 ), “ Dark cities: a dark tourism index for Europe's tourism cities, based on the analysis of DMO websites ”, International Journal of Tourism Cities , Vol. 4 No. 1 , pp. 4 - 21 , doi: 10.1108/ijtc-09-2017-0046 .

Raine , R. ( 2013 ), “ A dark tourist spectrum ”, International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research , Vol. 7 No. 3 , pp. 242 - 256 .

Robb , E.M. ( 2009 ), “ Violence and recreation: vacationing in the realm of dark tourism ”, Anthropology and Humanism , Vol. 34 No. 1 , pp. 51 - 60 .

Rojek , C. ( 1993 ), Ways of Escape: Modern Transformations in Leisure and Travel , Palgrave Macmillan .

Ryan , C. and Kohli , R. ( 2006 ), “ The Buried Village, New Zealand: an example of dark tourism? ”, Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research , Vol. 11 No. 3 , pp. 211 - 226 .

Seaton , A. ( 1996 ), “ Guided by the dark: from thanatopsis to thanatourism ”, International Journal of Heritage Studies , Vol. 2 No. 4 , pp. 234 - 244 .

Seaton , A. and Lennon , J.J. ( 2004 ), “ Thanatourism in the early 21st century: moral panics, ulterior motives and ulterior desires ”, in Singh , T. (Ed.), New Horizons in Tourism: Strange Experiences and Stranger Practices , CABI Publishing , Cambridge, MA , pp. 63 - 82 .

Sharpley , R. ( 2005 ), “ Travels to the edge of darkness: towards a typology of ‘dark tourism’ ”, in Aicken , M. , Page , S. and Ryan , C. (Eds), Taking Tourism to the Limits: Issues, Concepts, and Managerial Perspectives , Elsevier , pp. 215 - 226 .

Sharpley , R. and Stone , P. ( 2009 ), The Darker Side of Travel: The Theory and Practice of Dark Tourism , Channel View Publications , Bristol .

Stone , P.R. ( 2006 ), “ A Dark Tourism Spectrum: towards a typology of death and macabre related tourist sites, attractions and exhibitions ”, Tourism: An Interdisciplinary International Journal , Vol. 54 No. 2 , pp. 145 - 160 .

Strange , C. and Kempa , M. ( 2003 ), “ Shades of dark tourism: alcatraz and robben island ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 30 No. 2 , pp. 386 - 405 .

Swan , J. ( 1981 ), “ Disconfirmation of expectations and satisfaction with a retail service ”, Journal of Retailing , Vol. 57 No. 3 , pp. 49 - 66 .

Vazquez , D. and Xu , X. ( 2009 ), “ Investigating linkages between online purchase behaviour variables ”, International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management , Vol. 37 No. 5 , pp. 408 - 419 , doi: 10.1108/09590550910954900 .

Yan , B. , Zhang , J. , Zhang , H. , Lu , S. and Guo , Y. ( 2016 ), “ Investigating the motivation–experience relationship in a dark tourism space: a case study of the Beichuan earthquake relics, China ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 53 , pp. 108 - 121 , doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.09.014 .

Yankholmes , A. and McKercher , B. ( 2015 ), “ Understanding visitors to slavery heritage sites in Ghana ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 51 , pp. 22 - 32 , doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.04.003 .

Yoon , Y. and Uysal , M. ( 2005 ), “ An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: a structural model ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 26 No. 1 , pp. 45 - 56 , doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2003.08.016 .

Zhang , H. , Yang , Y. , Zheng , C. and Zhang , J. ( 2016 ), “ Too dark to revisit? The role of past experiences and intrapersonal constraints ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 54 , pp. 452 - 464 , doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.01.002 .

Further reading

Krisjanous , J. ( 2016 ), “ An exploratory multimodal discourse analysis of dark tourism websites: communicating issues around contested sites ”, Journal of Destination Marketing and Management , Vol. 5 No. 4 , pp. 341 - 350 , doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.07.005 .

Lennon , J. ( 2005 ), “ Journeys in understanding what is dark tourism? ”, The Sunday Observer , Vol. 23 October , available at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/travel/2005/oct/23/darktourism.observerscapesection .

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

What you should know about the rise of dark tourism

(Hint: It’s not all bad)

From the Roman Colosseum, where death was a spectator sport, to Halloween’s ancient origins in a Celtic festival of the dead, people have been drawn to death and tragedy for centuries.

But it wasn’t until the 1990s that a group of academics who were studying sites associated with the assassination of JFK gave this fascination with the macabre a name: dark tourism.

In more recent years, so-called dark tourism sites such as the National September 11 Memorial & Museum in New York City and Auschwitz-Birkenau, the former Nazi death camp in southern Poland, have noticed an increase in visitors. And since HBO aired its popular miniseries about the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster, tour operators have reported an uptick in the number of visitors to the Chernobyl exclusion zone.

So what exactly is dark tourism?

According to IUPUI associate professor of tourism Suosheng Wang, the term dark tourism describes the phenomenon of people traveling to sites of death and disaster, whether man-made or natural. It is also known as “milking the macabre,” the “dark side of tourism,” “thanatourism” and “tragedy tourism.”

Though dark tourism can seem like a particularly irksome form of voyeurism, it’s not that straightforward, Wang said.

“We cannot simply say dark tourism is a good or bad thing, which wholly depends on how dark tourism is organized and how the local communities think of developing dark tourism at dark sites,” Wang said. “On one hand, the original purpose of dark tourism sites is for visitors to memorialize the victims and receive education to ensure the ‘never again’ hope. This is why most of these sites are presented as sites of remembrance for heritage, education or history.”

On the other hand, after a disaster, dark tourism can put local people in a painful or uncomfortable situation, he said. When one’s hometown is turned into a site of tragic disaster, it serves as a constant reminder of the tragedy and can prevent one from moving beyond the disaster.

“In the transition from a place of past disaster to a place as a dark tourism destination, death is presented as entertainment,” Wang said. “Such dissonance is an integral and unavoidable characteristic of dark tourism, and the stigma of death and tragedy may be distasteful to the local residents.”

One reason Wang said we’ve seen a rise in dark tourism is because the number of disasters in the world is increasing too.

This means that developing a better understanding of dark tourism has become increasingly important as well, because it can play a crucial role in disaster recovery efforts – particularly in developing countries, where dark tourism can stimulate and empower a community in mourning, he said.

It’s complicated, however, because although dark tourism can be a much-needed driver of economic recovery for sites of past disasters, there’s a fine line to walk between memorializing the dead and exploiting human suffering for financial gain.