8 David Foster Wallace Essays You Can Read Online

If you've talked to me for more than five minutes, you probably know that I'm a huge fan of author and essayist David Foster Wallace . In my opinion, he's one of the most fascinating writers and thinkers that has ever lived, and he possessed an almost supernatural ability to articulate the human experience.

Listen, you don't have to be a pretentious white dude to fall for DFW. I know that stigma is out there, but it's just not true. David Foster Wallace's writing will appeal to anyone who likes to think deeply about the human experience. He really likes to dig into the meat of a moment — from describing state fair roller coaster rides to examining the mind of a detoxing addict. His explorations of the human consciousness are incredibly astute, and I've always felt as thought DFW was actually mapping out my own consciousness.

Contrary to what some may think, the way to become a DFW fan is not to immediately read Infinite Jest . I love Infinite Jest. It's one of my favorite books of all-time. But it is also over 1,000 pages long and extremely difficult to read. It took me seven months to read it for the first time. That's a lot to ask of yourself as a reader.

My recommendation is to start with David Foster Wallace's essays . They are pure gold. I discovered DFW when I was in college, and I would spend hours skiving off my homework to read anything I could get my hands on. Most of what I read I got for free on the Internet.

So, here's your guide to David Foster Wallace on the web. Once you've blown through these, pick up a copy of Consider the Lobster or A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again .

1. "This is Water" Commencement Speech

Technically this is a speech, but it will seriously revolutionize the way you think about the world and how you interact with it. You can listen to Wallace deliver it at Kenyon College , or you can read this transcript . Or, hey, do both.

2. "Consider the Lobster"

This is a classic. When he goes to the Maine Lobster Festival to do a report for Gourmet , DFW ends up taking his readers along for a deep, cerebral ride. Asking questions like "Do lobsters feel pain?" Wallace turns the whole celebration into a profound breakdown on the meaning of consciousness. (Don't forget to read the footnotes!)

2. "Ticket to the Fair"

Another episode of Wallace turning journalism into something more. Harper 's sent DFW to report on the state fair, and he emerged with this masterpiece. The Harper's subtitle says it all: "Wherein our reporter gorges himself on corn dogs, gapes at terrifying rides, savors the odor of pigs, exchanges unpleasantries with tattooed carnies, and admires the loveliness of cows."

3. "Federer as Religious Experience"

DFW was obviously obsessed with tennis, but you don't have to like or know anything about the sport to be drawn in by his writing. In this essay, originally published in the sports section of The New York Times , Wallace delivers a profile on Roger Federer that soon turns into a discussion of beauty with regard to athleticism. It's hypnotizing to read.

4. "Shipping Out: On the (nearly lethal) comforts of a luxury cruise"

Later published as "A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again" in the collection of the same name, this essay is the result of Harper's sending Wallace on a luxury cruise. Wallace describes how the cruise sends him into a depressive spiral, detailing the oddities that make up the strange atmosphere of an environment designed for ultimate "fun."

5. "E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction"

This is definitely in the running for my favorite DFW essay. (It's so hard to choose.) Fiction writers! Television! Voyeurism! Loneliness! Basically everything I love comes together in this piece as Wallace dives into a deep exploration of how humans find ways to look at each other. Though it's a little long, it's endlessly fascinating.

6. "String Theory"

"You are invited to try to imagine what it would be like to be among the hundred best in the world at something. At anything. I have tried to imagine; it's hard."

Originally published in Esquire , this article takes you deep into the intricate world of professional tennis. Wallace uses tennis (and specifically tennis player Michael Joyce) as a vehicle to explore the ideas of success, identity, and what it means to be a professional athlete.

7. "9/11: The View from the Midwest"

Written in the days following 9/11, this article details DFW and his community's struggle to come to terms with the attack.

8. "Tense Present: Democracy, English, and the Wars Over Usage "

If you're a language nerd like me, you'll really dig this one. A self-proclaimed "snoot" about grammar, Wallace dives into the world of dictionaries, exploring all of the implications of how language is used, how we understand and define grammar, and how the "Democratic Spirit" fits into the tumultuous realms of English.

Images: cocoparisienne /Pixabay; werner22brigette /Pixabay; StartupStockPhotos /Pixabay; PublicDomainPIctures /Pixabay

Subscribe to our newsletter

25 great articles and essays by david foster wallace, life and love, this is water, hail the returning dragon, clothed in new fire, words and writing, tense present, deciderization 2007, laughing with kafka, the nature of the fun, fictional futures and the conspicuously young, e unibus pluram: television and u.s. fiction, what words really mean, films, music and the media, david lynch keeps his head, signifying rappers, big red son, see also..., 150 great articles and essays.

Shipping Out

Ticket to the fair, consider the lobster, the string theory, federer as religious experience, tennis, trigonometry, tornadoes, the weasel, twelve monkeys and the shrub, 9/11: the view from the midwest, just asking, a supposedly fun thing i'll never do again, consider the lobster and other essays.

About The Electric Typewriter We search the net to bring you the best nonfiction, articles, essays and journalism

The best free cultural &

educational media on the web

- Online Courses

- Certificates

- Degrees & Mini-Degrees

- Audio Books

30 Free Essays & Stories by David Foster Wallace on the Web

in e-books , Literature | February 22nd, 2012 10 Comments

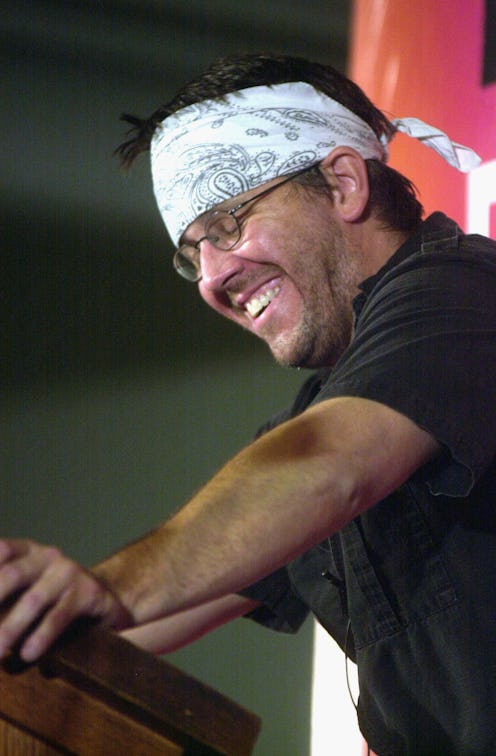

Image by Steve Rhodes, via Wikimedia Commons

We started the week expecting to publish one David Foster Wallace post . Then, because of the 50th birthday celebration, it turned into two . And now three. We spent some time tracking down free DFW stories and essays available on the web, and they’re all now listed in our collection, 800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices . But we didn’t want them to escape your attention. So here they are — 23 pieces published by David Foster Wallace between 1989 and 2011, mostly in major U.S. publications like The New Yorker , Harper’s , The Atlantic , and The Paris Review . Enjoy, and don’t miss our other collections of free writings by Philip K. Dick and Neil Gaiman .

- “9/11: The View From the Midwest” (Rolling Stone, October 25, 2001)

- “All That” (New Yorker, December 14, 2009)

- “An Interval” (New Yorker, January 30, 1995)

- “Asset” (New Yorker, January 30, 1995)

- “Backbone” An Excerpt from The Pale King (New Yorker, March 7, 2011)

- “Big Red Son” from Consider the Lobster & Other Essays

- “Brief Interviews with Hideous Men” (The Paris Review, Fall 1997)

- “Consider the Lobster” (Gourmet, August 2004)

- “David Lynch Keeps His Head” (Premiere, 1996)

- “Everything is Green” (Harpers, September 1989)

- “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction” (The Review of Contemporary Fiction, June 22, 1993)

- “Federer as Religious Experience” (New York Times, August 20, 2006)

- “Good People” (New Yorker, February 5, 2007)

- “Host” (The Atlantic, April 2005)

- “Incarnations of Burned Children” (Esquire, April 21, 2009)

- “Laughing with Kafka” (Harper’s, January 1998)

- “Little Expressionless Animals” (The Paris Review, Spring 1988)

- “On Life and Work” (Kenyon College Commencement address, 2005)

- “Order and Flux in Northampton” (Conjunctions, 1991)

- “Rabbit Resurrected” (Harper’s, August 1992)

- “ Several Birds” (New Yorker, June 17, 1994)

- “Shipping Out: On the (nearly lethal) comforts of a luxury cruise” (Harper’s, January 1996)

- “Tennis, trigonometry, tornadoes A Midwestern boyhood” (Harper’s, December 1991)

- “Tense Present: Democracy, English, and the wars over usage” (Harper’s, April 2001)

- “The Awakening of My Interest in Annular Systems” (Harper’s, September 1993)

- “The Compliance Branch” (Harper’s, February 2008)

- “The Depressed Person” (Harper’s, January 1998)

- “The String Theory” (Esquire, July 1996)

- “The Weasel, Twelve Monkeys And The Shrub” (Rolling Stone, April 2000)

- “Ticket to the Fair” (Harper’s, July 1994)

- “Wiggle Room” (New Yorker, March 9, 2009)

Related Content:

Free Philip K. Dick: Download 13 Great Science Fiction Stories

Neil Gaiman’s Free Short Stories

Read 17 Short Stories From Nobel Prize-Winning Writer Alice Munro Free Online

10 Free Stories by George Saunders, Author of Tenth of December , “The Best Book You’ll Read This Year”

by OC | Permalink | Comments (10) |

Related posts:

Comments (10), 10 comments so far.

I got another free DFW essay for you: Big Red Son http://www.hachettebookgroup.com/books_9780316156110_ChapterExcerpt(1) .htm

Thanks very much. I added it to the list.

Appreciate it, Dan

Thanks very much for this information regarding essays and stories

Hi Dan. It’s a bit late for this, but I just remembered another link you might want to add. You can hear DFW giving the full unabridged Kenyon commencement speech (which you link to in your list) at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M5THXa_H_N8 (it’s in 2 parts). Or download the full audio from http://www.mediafire.com/?file41t3kfml6q6 Thanks for all your hard work!

This is excellent, thanks so much. Will these links be up permanently? I want to avoid the trouble of downloading the stuff I don’t have time to get to now.

Just thought I’d mention that ‘Little Expressionless Animals” cuts off about 2/3rds of the way through, requiring you to purchase the issue ($40) for the chance to read the rest.

Kind of a bummer.

Don’t forget “Tracy Austin Serves Up a Bubbly Life Story” (review of Tracy Austin’s Beyond Center Court: My Story): http://www.mendeley.com/research/tracy-austin-serves-up-bubbly-life-story-review-tracy-austins-beyond-center-court-story

Also, just to let you know, the link to “Big Red Son” is broken.

There’s also a ton of other here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Foster_Wallace_bibliography

You can add “Good Old Neon” to your list if you like:

http://kalamazoo.coop/sites/default/files/Good%20Old%20Neon.pdf

There’s a bunch of articles with broken links, notably those from Harper’s Magazine. Has anybody saved them and would be so kind to share them?

Add a comment

Leave a reply.

Name (required)

Email (required)

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

- 1,700 Free Online Courses

- 200 Online Certificate Programs

- 100+ Online Degree & Mini-Degree Programs

- 1,150 Free Movies

- 1,000 Free Audio Books

- 150+ Best Podcasts

- 800 Free eBooks

- 200 Free Textbooks

- 300 Free Language Lessons

- 150 Free Business Courses

- Free K-12 Education

- Get Our Daily Email

Free Courses

- Art & Art History

- Classics/Ancient World

- Computer Science

- Data Science

- Engineering

- Environment

- Political Science

- Writing & Journalism

- All 1500 Free Courses

- 1000+ MOOCs & Certificate Courses

Receive our Daily Email

Free updates, get our daily email.

Get the best cultural and educational resources on the web curated for you in a daily email. We never spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

FOLLOW ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Free Movies

- 1150 Free Movies Online

- Free Film Noir

- Silent Films

- Documentaries

- Martial Arts/Kung Fu

- Free Hitchcock Films

- Free Charlie Chaplin

- Free John Wayne Movies

- Free Tarkovsky Films

- Free Dziga Vertov

- Free Oscar Winners

- Free Language Lessons

- All Languages

Free eBooks

- 700 Free eBooks

- Free Philosophy eBooks

- The Harvard Classics

- Philip K. Dick Stories

- Neil Gaiman Stories

- David Foster Wallace Stories & Essays

- Hemingway Stories

- Great Gatsby & Other Fitzgerald Novels

- HP Lovecraft

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Free Alice Munro Stories

- Jennifer Egan Stories

- George Saunders Stories

- Hunter S. Thompson Essays

- Joan Didion Essays

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez Stories

- David Sedaris Stories

- Stephen King

- Golden Age Comics

- Free Books by UC Press

- Life Changing Books

Free Audio Books

- 700 Free Audio Books

- Free Audio Books: Fiction

- Free Audio Books: Poetry

- Free Audio Books: Non-Fiction

Free Textbooks

- Free Physics Textbooks

- Free Computer Science Textbooks

- Free Math Textbooks

K-12 Resources

- Free Video Lessons

- Web Resources by Subject

- Quality YouTube Channels

- Teacher Resources

- All Free Kids Resources

Free Art & Images

- All Art Images & Books

- The Rijksmuseum

- Smithsonian

- The Guggenheim

- The National Gallery

- The Whitney

- LA County Museum

- Stanford University

- British Library

- Google Art Project

- French Revolution

- Getty Images

- Guggenheim Art Books

- Met Art Books

- Getty Art Books

- New York Public Library Maps

- Museum of New Zealand

- Smarthistory

- Coloring Books

- All Bach Organ Works

- All of Bach

- 80,000 Classical Music Scores

- Free Classical Music

- Live Classical Music

- 9,000 Grateful Dead Concerts

- Alan Lomax Blues & Folk Archive

Writing Tips

- William Zinsser

- Kurt Vonnegut

- Toni Morrison

- Margaret Atwood

- David Ogilvy

- Billy Wilder

- All posts by date

Personal Finance

- Open Personal Finance

- Amazon Kindle

- Architecture

- Artificial Intelligence

- Beat & Tweets

- Comics/Cartoons

- Current Affairs

- English Language

- Entrepreneurship

- Food & Drink

- Graduation Speech

- How to Learn for Free

- Internet Archive

- Language Lessons

- Most Popular

- Neuroscience

- Photography

- Pretty Much Pop

- Productivity

- UC Berkeley

- Uncategorized

- Video - Arts & Culture

- Video - Politics/Society

- Video - Science

- Video Games

Great Lectures

- Michel Foucault

- Sun Ra at UC Berkeley

- Richard Feynman

- Joseph Campbell

- Jorge Luis Borges

- Leonard Bernstein

- Richard Dawkins

- Buckminster Fuller

- Walter Kaufmann on Existentialism

- Jacques Lacan

- Roland Barthes

- Nobel Lectures by Writers

- Bertrand Russell

- Oxford Philosophy Lectures

Receive our newsletter!

Open Culture scours the web for the best educational media. We find the free courses and audio books you need, the language lessons & educational videos you want, and plenty of enlightenment in between.

Great Recordings

- T.S. Eliot Reads Waste Land

- Sylvia Plath - Ariel

- Joyce Reads Ulysses

- Joyce - Finnegans Wake

- Patti Smith Reads Virginia Woolf

- Albert Einstein

- Charles Bukowski

- Bill Murray

- Fitzgerald Reads Shakespeare

- William Faulkner

- Flannery O'Connor

- Tolkien - The Hobbit

- Allen Ginsberg - Howl

- Dylan Thomas

- Anne Sexton

- John Cheever

- David Foster Wallace

Book Lists By

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Ernest Hemingway

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Allen Ginsberg

- Patti Smith

- Henry Miller

- Christopher Hitchens

- Joseph Brodsky

- Donald Barthelme

- David Bowie

- Samuel Beckett

- Art Garfunkel

- Marilyn Monroe

- Picks by Female Creatives

- Zadie Smith & Gary Shteyngart

- Lynda Barry

Favorite Movies

- Kurosawa's 100

- David Lynch

- Werner Herzog

- Woody Allen

- Wes Anderson

- Luis Buñuel

- Roger Ebert

- Susan Sontag

- Scorsese Foreign Films

- Philosophy Films

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

©2006-2024 Open Culture, LLC. All rights reserved.

- Advertise with Us

- Copyright Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Find anything you save across the site in your account

5 David Foster Wallace Essays You Should Read Before Seeing The End of the Tour

By Lauren Larson

The End of the Tour could have been terrible; Jason Segel plays David Foster Wallace, and Jesse Eisenberg plays the douchey journalist charged with profiling him. But The End of the Tour is not terrible. It turns out Jason Segel is great at acting, and Jesse Eisenberg is great at being a douchebag.

So you’re really excited to see Segel put How I Met Your Mother behind him at last, but you’re harboring a dark secret: You’ve never read anything by David Foster Wallace. You lie and say you "found Infinite Jest and The Pale King positively resplendent." You say things like, “I admire Wallace’s fiction, but I much prefer his essays.” It’s alright. Everyone does it. Lying about having read David Foster Wallace is an American tradition. Like making up words to describe wine.

You'll like The End of the Tour whether you're a Wallace disciple or a flailing literary newborn, but a little primer never hurts. Here are five nuggets of Wallace brilliance that you can read before The End of the Tour comes out on July 31. Go forth, young man, and ooze pretension.

Ticket to the Fair

In 1993, a year before Infinite Jest was published, Wallace headed back to his native Illinois on assignment from Harper’s , to write about the Illinois State Fair. Ticket to the Fair is Wallace at his most readable. He’s just wandering around describing the height of Americana, like so:

The horses' faces are long and somehow suggestive of coffins. The racers are lanky, velvet over bone. The draft and show horses are mammoth and spotlessly groomed, and more or less odorless: the acrid smell in here is just the horses' pee: All their muscles are beautiful; the hides enhance them. They make farty noises when they sigh, heads hanging over the short doors. They're not for petting, though.

Read it here.

Consider the Lobster

The titular essay of Wallace’s collection Consider the Lobster began as a story for Gourmet . Following the tradition of sending Wallace to a mega-American event (see above) Gourmet sent Wallace to the Maine Lobster Festival. Every sentence of the essay is solid gold, and you will learn more about lobsters and life than you ever thought possible. As with all of Wallace’s writing, one must never skip the footnotes. Case in point, this tiny drama in note 11:

The short version regarding why we were back at the airport after already arriving the previous night involves lost luggage and a miscommunication about where and what the local National Car Rental franchise was—Dick came out personally to the airport and got us, out of no evident motive but kindness. (He also talked nonstop the entire way, with a very distinctive speaking style that can be described only as manically laconic; the truth is that I now know more about this man than I do about some members of my own family.)

9/11: The View From the Midwest

With the totally unnecessary caveat that this 2001 essay in Rolling Stone was “written very fast and in what probably qualifies as shock,” Wallace really, really effectively describes how most of the country experienced 9/11, or the Horror. A somber, great read, with little moments like this:

Mrs. T. has coffee on, but another sign of Crisis is that if you want some you have to get it yourself – usually it just sort of appears.

Roger Federer as Religious Experience

In 2008, when Roger Federer as Religious Experience ran in the Times , Federer mania was at its peak and Wallace was on the scene to explain it. Further proof that Wallace could write about literally anything in a nuanced way:

Nadal and Federer now warm each other up for precisely five minutes; the umpire keeps time. There’s a very definite order and etiquette to these pro warm-ups, which is something that television has decided you’re not interested in seeing.

Shipping Out: On the (Nearly Lethal) Comforts of a Luxury Cruise

Shipping Out , originally published in Harper’s in 1996, is the cornerstone of Wallace’s collection A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again . Many writers have tried and failed to describe the misery of luxury cruises as well as Wallace does. (Though an honorable mention goes to Tina Fey’s honeymoon in Bossypants .) Enjoy this tour of every neurotic man’s personal hell:

For the first two nights, who’s feeling seasick and who’s not and who’s not now but was a little while ago or isn’t feeling it yet but thinks it’s maybe coming on, etc. is a big topic of conversation at Table 64 in the Five-Star Caravelle Restaurant. Discussing nausea and vomiting while eating intricately prepared gourmet foods doesn’t seem to bother anybody.

Oh, to be blessed with a seat at Table 64. Read more here.

Related: John Jeremiah Sullivan Reviews The Pale King

Also Related:

This content can also be viewed on the site it originates from.

20% off $250 spend w/ Wayfair coupon code

Military Members save 15% Off - Michaels coupon

Enjoy 30% Off w/ ASOS Promo Code

eBay coupon for +$5 Off sitewide

Enjoy Peacock Premium for Only $1.99/Month Instead of $5.99

$100 discount on your next Samsung purchase* in 2024

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

The Last Essay I Need to Write about David Foster Wallace

Mary k. holland on closing the “open question” of wallace’s misogyny.

Feature photo by Steve Rhodes .

David Foster Wallace’s work has long been celebrated for audaciously reorienting fiction toward empathy, sincerity, and human connection after decades of (supposedly) bleak postmodern assertions that all had become nearly impossible. Linguistically rich and structurally innovative, his work is also thematically compelling, mounting brilliant critiques of liberal humanism’s masked oppressions, the soul-killing dangers of technology and American narcissism, and the increasing impotence of our culture of irony.

Wallace spoke and wrote movingly about our need to cultivate self-awareness in order to more fully see and respect others, and created formal methods that construct the reader-writer relationship with such piercing intimacy that his fans and critics feel they know and love him. A year after his death by suicide, as popular and critical attention to him and his work began to build into the industry of Wallace studies that exists today, he was first outed as a misogynist who stalked, manipulated, and physically attacked women.

In her 2009 memoir, Lit , Mary Karr spends less than four pages narrating the several years in which Wallace pursued her, leading to a brief romantic relationship that ended in vicious arguments and “his pitching my coffee table at me.” Unlike her accounts of the relationship nearly a decade later, Karr’s tone here notably remains clever and humorous throughout. She also follows each disclosure of Wallace’s ferocity with a confession of her own regrettable behavior: regarding his “temper fits” she admits to “sentences I had to apologize for” and assures us—twice—that “no doubt he was richly provoked.” After describing the coffee-table incident, she notes parenthetically that “years later, we’ll accept each other’s longhand apologies for the whole debacle,” as if having a piece of furniture thrown at you makes you as guilty as having thrown it.

Three years later D.T. Max published his biography of Wallace, in which he divulged more shocking details about the relationship with Karr—that Wallace tried to buy a gun to kill her husband, that he tried to push her from a moving car—while also dropping enough details about Wallace’s sex life and professed attitudes toward women to make him sound like one of his own hideous men. Wallace called female fans at his readings “audience pussy”; wondered to Jonathan Franzen whether “his only purpose on earth was ‘to put my penis in as many vaginas as possible’”; picked up vulnerable women in his recovery groups; admitted to a “fetish for conquering young mothers,” like Orin in Infinite Jest ; and “affected not to care that some of the women were his students.”

In a 2016 anthology dedicated to the late author, one of those students, Suzanne Scanlon, published a short story about a student having a manipulative, emotionally abusive sexual affair with her professor (called “D-,” “Author,” and “a self-identified Misogynist”), using characteristic formal elements of “Octet” and “Brief Interviews” and dominated by the narrative voice popularized by David Foster Wallace.

None of these accounts had any visible impact on fans’ or readers’ love of Wallace’s writing or on critics’ readings and opinions of his work. Rather, one writer, Rebecca Rothfeld, confessed in 2013 that Max’s record of (some of) Wallace’s misogynistic acts and statements could not shake her “faith in [his] fundamental goodness, intelligence, and likeability” because his “work seemed more real to me than his behavior did.” Critic Amy Hungerford took the opposite stance in 2016, proclaiming her decision to stop reading and teaching Wallace’s work, but without mentioning his abusive treatment of women or the question of how that behavior presses us to re-read the same in his work.

Another writer, Deirdre Coyle, explained her discomfort at reading Wallace not in terms of the author’s own behavior—which she gives no sign of being aware of—but because of sexual and misogynistic violence perpetrated on her by men she sees as very much like Wallace (“Small liberal arts colleges are breeding grounds for these guys”) and in terms of patriarchy in general (“It’s hard to distinguish my reaction to Wallace from my reaction to patriarchy.” Any woman who has been violated, talked over, and condescended to by this kind of man, the kind who thinks his pseudo-feminism allows him to enlighten her about her own experiences of male oppression and sexual violation, cannot help but sympathize with Coyle.

But in rejecting Wallace because of other men’s sexual violence and misogyny in general, she shifts the argument away from questions about how these function in the fiction and how Wallace’s biography might force us to re-read that fiction, and allows for the kind of circular rebuttal that a (male) Wallace critic offered a year later: not all male readers of Wallace are misogynists; therefore, women should listen to the good ones and read more Wallace; let me tell you why.

These pre-#MeToo reactions to Karr’s and Max’s reports of Wallace’s abuse of women clarify what is at stake as readers, critics, and teachers consider this biographical information in the context of Wallace’s work. For, while Wimsatt and Beardsley’s argument against the intentional fallacy is compelling and important, its goal is to protect the sanctity of the text against the undue influence of our assumptions about the person who wrote it. Arguments defending the importance of Wallace’s beautiful empathizing fiction in spite of his abuse of women threaten to do the opposite.

Like Rothfeld, whose admiration for Wallace’s fiction renders his own misogynistic acts less “real,” David Hering argues that “the biographical revelation of unsavoury details about Wallace’s own relationships” leads to an equation between Wallace and misogyny that “does a fundamental disservice to the kind of urgent questions Wallace asks in his work about communication, empathy, and power”—as if Wallace’s real abuse of real women is not worth contemplating in comparison with his writing about how fictional men treat fictional women. Hering’s use of the euphemism “unsavoury” to describe behavior ranging from exploitation to physical attacks, like his description of Wallace’s work regarding gender as “troublesome,” illustrates another widespread problem with nearly all critical treatments of this topic so far: an unwillingness to say, or perhaps even see, that what we are talking about in the fiction and in the author’s life is gender-motivated violence, stalking, physical abuse, even, in the case of Karr’s husband, plotting to murder.

In the wake of the October 2017 resurgence of Burke’s #MeToo movement, we see a curious split between Wallace-studies critics and others in their reactions to these allegations. Not only does Hering’s response downplay the severity of Wallace’s behavior and its relevance to his work; it also asserts Hering’s “belief” that Wallace’s work “dramatize[s]” misogyny, rather than expressing it—without offering a text-based argument or pointing to the critical work that had already done this analysis and found exactly the opposite to be true.

He also relies on a technique used by memoirists, bloggers, and critics alike in their attempts to save Wallace from his own biography: he converts an example of male domination of women into a universal human dilemma, erasing the elements of gender and power entirely, by reading Wallace’s silencing of his female interviewer’s voice in Brief Interviews as “embody[ing] the richness of Wallace’s work—its focus on the difficulty and importance of communication and empathy, and its illustration of the poisonous things that happen when dialogue breaks down.” Such a reading ignores the fact that when dialogue breaks down between an entitled man and a pressured woman , the things that can happen go beyond metaphorically poisonous to physically sickening and injurious—as so many of the stories in that collection illustrate.

Given the same platform and the same task—celebrating Wallace around what would have been his 56th birthday—critic Clare Hayes-Brady offered “Reading David Foster Wallace in 2018,” mere months after the social media flood of women’s testimonies about sexual violence had begun. It does not mention #MeToo or the public allegations that had been made about Wallace, raising the question of what “in 2018” refers to. When asked several months later “what’s changed?” in Wallace studies, after the public (but not critical) backlash had begun, Hayes-Brady falls back on the same generalizing technique used by Hering. She reframes accusations of misogyny as an entirely academic development, beneficial to Wallace studies and unrelated to #MeToo outcry against perpetrators of sexual violence (“a coincidence of timing”). She equates “flaws in his writing both technical and also moral and ethical,” as if women had been up in arms across Twitter over Wallace’s exhausting sentence structures.

When directly asked if Wallace was a misogynist, she replies “yes, but in the way everyone is, including me,” as if we neither have nor need a separate word for men who do not just live unavoidably in our misogynistic culture but also willfully perpetrate selfish, cruel, and violent acts of misogyny against women. That is, rather than responding humanely to indisputable evidence that our beloved writer was not the saint he would have liked us to think he was (and that we would have liked to believe him to be), Wallace critics—including me, in my silence at that time—refused to allow #MeToo to force the reckoning that was so clearly required. We did so by denying the relevance of his personal behavior to his fiction and to our work, or—worse—by participating in that age-old rape culture enabler: refusing to believe women’s testimony.

Those outside literary studies reacted quite differently to the renewed attention #MeToo brought to these accusations. After Junot Díaz was publicly accused on May 4, 2018, of sexually abusing women, causing immediate public protest, Mary Karr responded by reminding us on Twitter of the abuse she had reported nearly a decade earlier, prompting a series of blog articles and interviews that supported Karr by recounting the allegations made by Karr and Max. They also began to reveal the misogyny that had shaped and stifled public reception of those allegations.

Whitney Kimball pointed out that Max described Wallace’s violent treatment of Karr as beneficial to his creative output and part of what made him “fascinating”; that in praising the “quite remarkable” “craftsmanship” of one of Wallace’s letters, Max notes only in passing that the letter is Wallace’s apology for planning to buy a gun to kill Karr’s husband. Megan Garber noted the misogyny of an interviewer asking Max why “his feelings for [Karr] created such trouble for Wallace”—an example of what Kate Manne calls “himpathy,” or empathizing with a male perpetrator of sexual violence rather than the victim.

#MeToo also began to make the misogyny of Wallace’s work more visible to his readers. Devon Price describes how reading about Wallace’s abuses against women caused them to revisit Wallace’s work and see its gender violence for the first time. Tellingly, Price also realizes that one of the reasons they were depressed when they fell in love with Wallace’s work is that they were then in a physically, emotionally, and sexually abusive relationship. Price’s realization points to another common reason why readers are blind to or defensive about the misogyny in Wallace’s work and behavior, and to a key way in which the #MeToo movement can allow reading and literary studies to illuminate misogyny in synergistic ways: we are often blind to misogyny and sexual abuse, in fiction and in others’ behavior, because we are living in it unaware. And the awareness of the spectrum of sexual abuse brought by #MeToo testimonies reveals misogyny not just in the fiction that we read, but in our own lives—one revelation causing the other.

To date, no new criticism has emerged that directly considers the implications to his work of Wallace’s now widely reported misogyny and violence toward women. But the recent publication of Adrienne Miller’s memoir In the Land of Men (2020), which describes her years-long relationship with Wallace while she was literary editor at Esquire , makes a compelling, if unwitting, argument for the necessity of such biographically informed criticism. Miller documents the connection between Wallace’s life and work in excruciating detail, recounting extended scenes between them in which Wallace speaks and acts nearly identically to the misogynists of Brief Interviews , an identification he encourages by telling her that “some of the interviews were ‘actual conversations I had when I had to break up with people.’”

But though Miller lays out the “sexism” of Wallace’s fiction, especially Jest and Brief Interviews , more baldly than any of us Wallace scholars has so far, she remains, even from the vantage point of twenty years later and post-#MeToo, unable or unwilling to identify Wallace’s treatment of her as abusive or misogynistic. In fact, most shocking about the memoir is not its record of Wallace’s behavior but its methodical and steadfast refusal to acknowledge the gender violence of that behavior, and Miller’s disturbing pattern of normalizing, apologizing for, and denying it.

Ultimately, she attempts to redirect us from the question of whether her relationship with Wallace qualifies as abuse or sexual harassment by asking, “Who looks to the artist’s life for moral guidance anyway?” and “What are we to do with the art of profoundly compromised men?” But rather than neatly pivoting from Wallace’s culpability, these questions reveal important reasons why we must consider the lives of such men in conversation with their art. For these men are not merely passively “compromised” but aggressively compromis ing , in ways that our misogynistic culture obscures, and which savvy investigation of their art and lives can illuminate. And “moral” investigation is particularly indicated by the work of Wallace, who declared himself a maverick writer willing to return literature to earnestness and “love” (“Interview with David Foster Wallace” 1993), who wrote fiction that quizzes us on ethics and human value (“Octet” 1999), and who delivered a beloved commencement speech arguing the importance of recognizing one’s inherent narcissism in order to extend care to others.

What does it mean that this artist could not produce in his life the mutually respecting empathy he all but preached in his work (or, most clearly, in his statements about it)? What does it mean that a man and a body of work that claimed feminism in theory primarily produced a stream of abusive relationships between men and women in life and art? What can we learn about the blindness of both men and women to their participation in misogyny and rape culture, despite their professions of awareness of both? How might reading Wallace’s fiction in the contexts of biographical information about him and women’s narratives about their experiences of sexual violence enable us to better understand—and interrupt—the powerful hold misogyny and rape culture have on our society, our art, and our critical practices?

_____________________________________________________________________

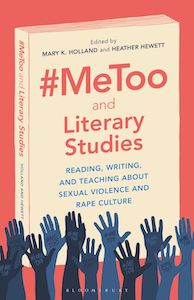

Excerpted from #MeToo and Literary Studies: Reading, Writing, and Teaching about Sexual Violence and Rape Culture , edited by Mary K. Holland & Heather Hewett. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury Academic. © 2021 by Mary K. Holland & Heather Hewett.

Mary K. Holland

Previous article, next article.

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Find anything you save across the site in your account

David Foster Wallace’s Perfect Game

By John Jeremiah Sullivan

“Tennis” is a wonderful word in the sense that it never really existed. That is, although the game is French to the core—not one but two of France’s early kings died at the tennis courts, and the Republic was born on one, with the Tennis Court Oath—the French never called it that, tennis. They called it jeu de paume , the “game of the palm,” or “handball,” if we want to be less awkwardly literal about it. (Originally they had played it with the bare hand, then came gloves, then paddles, then rackets.) When the French would go to serve, they often said, Tenez !, the French word for “take it,” meaning “coming at you, heads up.” We preserve this custom of warning the opponent in our less lyrical way by stating the score just before we toss up the ball. It was the Italians who, having overheard the French make these sounds, began calling the game “ten-ez” by association. A lovely detail in that it suggests a scene, a Florentine ear at the fence or the entryway, listening. They often built those early courts in the forest, in clearings. The call in the air. Easy to think of Benjy in “The Sound and the Fury,” hearing the golfers shout “Caddy!” and assuming they mean his sister, only here the word moves between languages, out of France via the transnational culture of the aristocratic court and into Italy. There it enters European literature around the thirteen-fifties, the time of Petrarch’s “Phisicke Against Fortune.” In considering the anxiety that consumes so much of human experience, he writes, “And what is the cause hereof, but only our own lightness & daintiness: for we seem to be good for nothing else, but to be tossed hither & thither like a Tennise bal, being creatures of very short life, of infinite carefulness, & yet ignorant unto what shore to sail with our ship.”

A metaphor for human existence, then, and for fate: “We are merely the stars’ tennis-balls,” in John Webster’s “Duchess of Malfi,” “struck and banded / Which way please them.” That is one tradition. In another, tennis becomes a symbol of frivolity, of a different kind of “lightness.” Grown men playing with balls. The history of the game’s being used that way is twined up with an anecdote from the reign of Henry V, the powerful young king who had once been Shakespeare’s reckless Prince Hal. According to one early chronicler, “The Dauphin, thinking King Henry to be given to such plays and light follies . . . sent to him a tun of tennis-balls.” King Henry’s imagined reply at the battle of Agincourt was rendered into verse, probably by the poet-monk John Lydgate, around 1536:

Some hard tennis balls I have hither brought Of marble and iron made full round. I swear, by Jesu that me dear bought, They shall beat the walls to the ground.

That story flowers into a couplet of Shakespeare’s “Henry V,” circa 1599. The package from the Dauphin arrives. Henry’s uncle, the Duke of Exeter, takes it. “What treasure, uncle?” the king asks. “Tennis-balls, my liege,” Exeter answers. “And we understand him well,” Henry says (a line meant to echo an earlier one, said under very different circumstances, Hal’s equally famous “I know you all and will awhile uphold”):

How he comes o’er us with our wilder days Not measuring what use we made of them.

A more eccentric instance of tennis-as-metaphor pops up in Shakespeare’s “Pericles,” where the tennis court is compared with the ocean. It occurs in the part of the play that scholars now believe was written by a tavern-keeper named George Wilkins. Pericles has just been tossed half dead onto the Greek shore and is discovered by three fishermen. He says,

A man whom both the waters and the wind, In that vast tennis-court, hath made the ball For them to play upon, entreats you pity him.

These lines may cause some modern readers to recall David Foster Wallace’s “Derivative Sport in Tornado Alley,” an essay about learning to play the game in the central Midwest, where extreme winds are an almost constant factor, but where Wallace succeeded, he tells us, in part because of a “weird robotic detachment” from the “unfairnesses of wind and weather.”

David Foster Wallace wrote about tennis because life gave it to him—he had played the game well at the junior level—and because he was a writer who in his own way made use of wilder days, turning relentlessly in his work to the stuff of his own experience. But the fact of the game in his biography came before any thought of its use as material. At least I assume that’s the case. It can be amazing how early in life some writers figure out what they are and start to see their lives as stories that can be controlled. It is perhaps not far-fetched to imagine Wallace’s noticing early on that tennis is a good sport for literary types and purposes. It draws the obsessive and brooding. It is perhaps the most isolating of games. Even boxers have a corner, but in professional tennis it is a rules violation for your coach to communicate with you beyond polite encouragement, and spectators are asked to keep silent while you play. Your opponent is far away, or, if near, is indifferently hostile. It may be as close as we come to physical chess, or a kind of chess in which the mind and body are at one in attacking essentially mathematical problems. So, a good game not just for writers but for philosophers, too. The perfect game for Wallace.

He wrote about it in fiction, essays, journalism, and reviews; it may be his most consistent theme at the surface level. Wallace himself drew attention, consciously or not, to both his love for the game and its relevance to how he saw the world. He knew something, too, about the contemporary literature of the sport. The close attention to both physics and physical detail that energizes the opening of his 1996 Esquire _ piece on a then-young Michael Joyce (a promising power baseliner who became a sought-after coach and helped Maria Sharapova win two of her Grand Slam titles) echoes clearly the first lines of John McPhee’s “Levels of the Game” _(one of the few tennis books I can think of that give as much pleasure as the one you’re holding): “Arthur Ashe, his feet apart, his knees slightly bent, lifts a tennis ball into the air. The toss is high and forward. If the ball were allowed to drop, it would, in Ashe’s words, ‘make a parabola.’ ”

For me, the cumulative effect of Wallace’s tennis-themed nonfiction is a bit like being presented with a mirror, one of those segmented mirrors they build and position in space, only this one is pointed at a writer’s mind. The game he writes about is one that, like language, emphasizes the closed system, makes a fetish of it (“Out!”). He seems both to exult and to be trapped in its rules, its cruelties. He loves the game but yearns to transcend it. As always in Wallace’s writing, Wittgenstein is the philosopher who most haunts the approach, the Wittgenstein who told us that reality is inseparable from language (“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world”), and that language is inseparable from game (both being at root “part of an activity, a form of life”).

From such a description a reader might conclude that the writer under discussion was dry and abstract, and in the end only using the sport, in a convenient, manipulative way, to say other things, which he deemed more significant—but that is not the writer you’ll meet in the following pages. This is instead one who can transpose on-court sensations into his prose. In those paragraphs that describe how growing up in a windy country shaped his game, briefly allowing him to excel over more talented opponents who tended to get frustrated in unpredictable conditions, he tells us that he was “able to use the currents kind of the way a pitcher uses spit. I could hit curves way out into cross-breezes that’d drop the ball just fair; I had a special wind-serve that had so much spin the ball turned oval in the air and curved left to right. . . .” In reviewing Tracy Austin’s autobiography, he finds a way, despite his disappointment with the book, to say something about athletic greatness and mediocrity, and what truly differentiates them, remembering how as a player he would often “get divided, paralyzed. As most ungreat athletes do. Freeze up, choke. Lose our focus. Become self-conscious. Cease to be wholly present in our wills and choices and movements.” Unlike the great, who become so in part because it would never occur to them not to be “totally present.” Their “blindness and dumbness,” in other words, are not “the price of the gift” but “its essence,” and are even the gift itself. The writer, existing only in reflection, is of all beings most excluded from the highest realms.

Possibly Wallace’s finest tennis piece, certainly his most famous, is “Federer Both Flesh and Not,” an essay first published in 2006 in the Times ’ short-lived sports magazine Play . The greatest tennis writer of his generation was writing about the greatest player of his generation. The sentence needs no qualifiers. Federer himself later remarked, in a question-and-answer forum, that he was astonished at what a “comprehensive” piece Wallace had produced, despite the fact that Federer had spent only “20 min with him in the ATP office.” But I doubt Wallace wanted more face time than that. He had come to Wimbledon in search of not the man Roger Federer but rather the being Federer seemed to become when he competed. What Wallace wanted to see occurred only as spectacle. In that respect and others, it is interesting to compare the Federer piece with the profile Wallace had written precisely a decade before, about Michael Joyce. I tend to prefer the earlier piece, for its thick description and subtleties, while recognizing the greatness of the later one. In the Joyce piece, Wallace had written about a nobody, a player no one had heard of and who was never going to make it on the tour. That was the subtext, and at times the text, of the essay: you could be that _ good and still not be good enough. The essay was about agony. In Federer, though, he had a player who offered him a different subject: transcendence. What it actually looked like. An athlete who appeared “to be exempt, at least in part, from certain physical laws.” One can see exactly what Wallace means in footage of the point he breaks down so beautifully—a “sixteen-stroke point” that reads as dramatically as a battle scene—which occurred in the second set of Federer’s 2006 Wimbledon final match against Rafael Nadal, a point that ends with a backhand one can replay infinite times and somehow come no closer to comprehending, struck from about an inch inside the baseline with some kind of demented spin that causes the ball to slip _over the net and vanish. Nadal never touches it. Wallace is able not only to give us the moment but to let us see the strategic and geometric intelligence that went into setting it up, the ability Federer had (has, as of this writing) to “hypnotize” opponents through shot selection.

The key sentences in the Federer essay, to my mind, occur in the paragraph that mentions “evolution.” In discussing the “power baseline” style that has defined the game in the modern era—two heavy hitters standing back and blasting wrist-fracturing ground strokes at each other—Wallace writes that “it is not, as pundits have publicly feared for years, the evolutionary endpoint of tennis. The player who’s shown this to be true is Roger Federer.” One imagines his writing this sentence with something almost like gratitude. It had taken genius to break through the brutal dictates of the power game and bring back an all-court style, to bring back art. And Federer, as Wallace emphasizes, did this from “within” the power game; he did it while handling shots that were moving at hurricane force. Inside the wind tunnel of modern tennis, he crafted a style that seemed made for a butterfly, yet was crushingly effective. What a marvelous subject, and figure, for a twenty-first-century novelist, a writer working in a form that is also (perpetually?) said to be at the end of its evolution, and an artist who similarly, when at his best, showed new ways forward.

This piece was drawn from the introduction to “String Theory: David Foster Wallace on Tennis,” which is out May 10th from Library of America.

David Foster Wallace on Writing, Self-Improvement, and How We Become Who We Are

By maria popova.

In late 1999, David Foster Wallace (February 21, 1962–September 12, 2008) — poignant contemplator of death and redemption , tragic prophet of the meaning of life , champion of intelligent entertainment , admonisher against blind ambition , advocate of true leadership — called the office of the prolific writer-about-writing Bryan A. Garner and, declining to be put through to Garner himself, grilled his secretary about her boss. Wallace was working on an extensive essay about Garner’s work and his newly released Dictionary of Modern American Usage . A few weeks later, Garner received a hefty package in the mail — the manuscript of Wallace’s essay, titled “Tense Present,” which was famously rejected by The New Republic and The New York Review of Books , then finally published by Harper’s and included in the 2005 anthology Consider the Lobster and Other Essays . Garner later wrote of the review, “a long, laudatory piece”: “It changed my literary life in ways that a book review rarely can.”

Over the course of the exchange, the two struck up a friendship and began an ongoing correspondence, culminating in Garner’s extensive interview with Wallace, conducted on February 3, 2006, in Los Angeles — the kind of conversation that reveals as much about its subject matter, in this case writing and language, as it does about the inner workings of its subject’s psyche. Five years after Wallace’s death, their conversation was published in Quack This Way: David Foster Wallace & Bryan A. Garner Talk Language and Writing ( public library ).

Wallace begins at the beginning, responding to Garner’s request to define good writing:

In the broadest possible sense, writing well means to communicate clearly and interestingly and in a way that feels alive to the reader. Where there’s some kind of relationship between the writer and the reader — even though it’s mediated by a kind of text — there’s an electricity about it.

Wallace, who by the time of the interview had fifteen years of teaching writing and literature under his belt, considers how one might learn this delicate craft:

In my experience with students—talented students of writing — the most important thing for them to remember is that someone who is not them and cannot read their mind is going to have to read this. In order to write effectively, you don’t pretend it’s a letter to some individual you know, but you never forget that what you’re engaged in is a communication to another human being. The bromide associated with this is that the reader cannot read your mind. The reader cannot read your mind . That would be the biggest one. Probably the second biggest one is learning to pay attention in different ways. Not just reading a lot, but paying attention to the way the sentences are put together, the clauses are joined, the way the sentences go to make up a paragraph.

This act of paying attention, Wallace argues, is a matter of slowing oneself down. Echoing Mary Gordon’s case for writing by hand , he tells Garner:

The writing writing that I do is longhand. . . . The first two or three drafts are always longhand. . . . I can type very much faster than I can write. And writing makes me slow down in a way that helps me pay attention.

In a sentiment that brings to mind Susan Sontag’s beautiful Letter to Borges , in which she defines writing as an act of self-transcendence, Wallace argues for the craft as an antidote to selfishness and self-involvement, and at the same time a springboard for self-improvement:

One of the things that’s good about writing and practicing writing is it’s a great remedy for my natural self-involvement and self-centeredness. . . . When students snap to the fact that there’s such a thing as a really bad writer, a pretty good writer, a great writer — when they start wanting to get better — they start realizing that really learning how to write effectively is, in fact, probably more of a matter of spirit than it is of intellect. I think probably even of verbal facility. And the spirit means I never forget there’s someone on the end of the line, that I owe that person certain allegiances, that I’m sending that person all kinds of messages, only some of which have to do with the actual content of what it is I’m trying to say.

Wallace argues that one of the most important points of awareness, and one of the most shocking to aspiring writers, can be summed up thusly:

“I am not, in and of myself, interesting to a reader. If I want to seem interesting, work has to be done in order to make myself interesting.”

(Vonnegut only compounded the terror when he memorably admonished , “The most damning revelation you can make about yourself is that you do not know what is interesting and what is not.” )

Wallace weighs the question of talent, erring on the side of grit as the quality that sets successful writers apart:

There’s a certain amount of stuff about writing that’s like music or math or certain kinds of sports. Some people really have a knack for this. . . . One of the exciting things about teaching college is you see a couple of them every semester. They’re not always the best writers in the room because the other part of it is it takes a heck of a lot of practice. Gifted, really really gifted writers pick stuff up quicker, but they also usually have a great deal more ego invested in what they write and tend to be more difficult to teach. . . . Good writing isn’t a science. It’s an art, and the horizon is infinite. You can always get better.

Despite the prevalence of mindless language usage , Wallace — not one to miss an opportunity to poke some fun at then-President George Bush — makes a case for a yang to the yin of E.B. White’s assertion that the writer’s responsibility is “to lift people up, not lower them down,” arguing that part of that responsibility is also having faith in the reader’s capacities and sensitivities:

Regardless of whom you’re writing for or what you think about the current debased state of the English language, right? — in which the President says things that would embarrass a junior-high-school student — the fact remains that … the average person you’re writing for is an acute, sensitive, attentive, sophisticated reader who will appreciate adroitness, precision, economy, and clarity. Not always, but I think the vast majority of the time.

Learning to write well, with elegance and sensitivity, shouldn’t be reserved for those trying to have a formal career in writing — it also, Wallace points out, immunizes us against the laziness of clichés and vogue expressions :

A vogue word … becomes trendy because a great deal of listening, talking, and writing for many people takes place below the level of consciousness. It happens very fast. They don’t pay it very much attention, and they’ve heard it a lot. It kind of enters into the nervous system. They get the idea, without it ever being conscious, that this is the good, current, credible way to say this, and they spout it back. And for people outside, say, the corporate business world or the advertising world, it becomes very easy to make fun of this kind of stuff. But in fact, probably if we look carefully at ourselves and the way we’re constantly learning language . . . a lot of us are very sloppy in the way that we use language. And another advantage of learning to write better, whether or not you want to do it for a living, is that it makes you pay more attention to this stuff. The downside is stuff begins bugging you that didn’t bug you before. If you’re in the express lane and it says, “10 Items or Less,” you will be bugged because less is actually inferior to fewer for items that are countable. So you can end up being bugged a lot of the time. But it is still, I think, well worth paying attention. And it does help, I think . . . the more attention one pays, the more one is immune to the worst excesses of vogue words, slang, you know. Which really I think on some level for a lot of listeners or readers, if you use a whole lot of it, you just kind of look like a sheep—somebody who isn’t thinking, but is parroting.

He returns to the question of good writing and the deliberate practice it takes to master:

Writing well in the sense of writing something interesting and urgent and alive, that actually has calories in it for the reader — the reader walks away having benefited from the 45 minutes she put into reading the thing — maybe isn’t hard for a certain few. I mean, maybe John Updike’s first drafts are these incredible . . . Apparently Bertrand Russell could just simply sit down and do this. I don’t know anyone who can do that. For me, the cliché that “Writing that appears effortless takes the most work” has been borne out through very unpleasant experience.

In a sentiment that Anne Lamott memorably made, urging that perfectionism is the great enemy of creativity , and Neil Gaiman subsequently echoed in his 8 rules of writing , where he asserted that “perfection is like chasing the horizon,” Wallace adds:

Like any art, probably, the more experience you have with it, the more the horizon of what being really good is . . . the more it recedes. . . . Which you could say is an important part of my education as a writer. If I’m not aware of some deficits, I’m not going to be working hard to try to overcome them. . . . Like any kind of infinitely rich art, or any infinitely rich medium, like language, the possibilities for improvement are infinite and so are the possibilities for screwing up and ceasing to be good in the ways you want to be good.

Reflecting on the writers he sees as “models of incredibly clear, beautiful, alive, urgent, crackling-with-voltage prose” — he lists William Gass, Don DeLillo, Cynthia Ozick, Louise Erdrich, and Cormac McCarthy — Wallace makes a beautiful case for the gift of encountering, of arriving in the work of that rare writer who not only shares one’s sensibility but also offers an almost spiritual resonance. (For me, those writers include Rebecca Solnit , Dani Shapiro , Susan Sontag , Carl Sagan , E.B White , Anne Lamott , Virginia Woolf .) Wallace puts it elegantly:

If you spend enough time reading or writing, you find a voice, but you also find certain tastes. You find certain writers who when they write, it makes your own brain voice like a tuning fork, and you just resonate with them. And when that happens, reading those writers … becomes a source of unbelievable joy. It’s like eating candy for the soul. And I sometimes have a hard time understanding how people who don’t have that in their lives make it through the day.

Echoing Kandinsky’s thoughts on the spiritual element in art , he adds:

Lucky people develop a relationship with a certain kind of art that becomes spiritual, almost religious, and doesn’t mean, you know, church stuff, but it means you’re just never the same.

But perhaps his most important point is that the act of finding our purpose and finding ourselves is not an A-to-B journey but a dynamic act, one predicated on continually, cyclically getting lost — something we so often, and with such spiritually toxic consequences, forget in a culture where the first thing we ask a stranger is “So, what do you do?” Wallace tells Garner:

I don’t think there’s a person alive who doesn’t have certain passions. I think if you’re lucky, either by genetics or you just get a really good education, you find things that become passions that are just really rich and really good and really joyful, as opposed to the passion being, you know, getting drunk and watching football. Which has its appeals, right? But it is not the sort of calories that get you through your 20s, and then your 30s, and then your 40s, and, “Ooh, here comes death,” you know, the big stuff. . . . It’s also true that we go through cycles. . . . These are actually good — one’s being larval. . . . But I think the hard thing to distinguish among my friends is who . . . who’s the 45-year-old who doesn’t know what she likes or what she wants to do? Is she immature? Or is she somebody who’s getting reborn over and over and over again? In a way, that’s rather cool.

Quack This Way is excellent in its entirety, brimming with the very spiritual resonance discussed above. Complement it with this compendium of famous writers’ wisdom on the craft , including Kurt Vonnegut ’s 8 rules for writing with style , Henry Miller ’s 11 commandments , Susan Sontag ’s synthesized wisdom , Chinua Achebe on the writer’s responsibility , Nietzsche ’s 10 rules for writers , and Jeanette Winterson on reading and writing .

— Published August 11, 2014 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2014/08/11/david-foster-wallace-quack-this-way/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, art books creativity culture david foster wallace interview writing, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

What Would Bale Do

An ongoing exploration of the dark and gritty reboot

The Beginner’s Guide to David Foster Wallace: Five Things to Read, for Free

The Best David Foster Wallace Books (or Stories or Essays) to Try Reading

Perhaps you want to see the new David Foster Wallace movie , but you aren’t sure why. You know that you like him, or that you might like him, that you are supposed to like him. Or maybe you just like Jason Segal and Jesse Eisenberg. Maybe you just think that the movie looks really good, or really sad, or you just want to understand why people are talking about it so much.

Maybe the only thing you know about David Foster Wallace is that someone made a video about fish and he narrated it , and that it’s one of your favorite motivational YouTube videos. Or maybe not.

Regardless, DFW is one of those authors who can be extremely inaccessible, especially if you haven’t ever read anything by him. It can feel like trying to start reading graphic novels or listening to Joy Division: you don’t know where to start and none of it makes any sense.

So here you go. Five things by David Foster Wallace that are both readable and that will give you a good idea of who he is and why he matters. And they’re free.

1. Consider the Lobster

I recommend one starts with the essay “Consider the Lobster,” published in Gourmet Magazine in 2004. If you don’t like this essay, then you won’t like David Foster Wallace. But chances are that you will like it. It’s fun, informative, intelligent and bizarre. It’s also non-fiction and not too long. And it gives you an idea of how wild his footnotes can be.

You can find it in more than one place online, but it’s most fun to read it in the format that was originally published, footnotes and all.

2. The Depressed Person

Unlike “Consider the Lobster,” this story is definitely not fun. And its footnotes are even more out of control.

But it’s a good way to understand both his fiction and the man himself. It’s a story about depression and suicide, published in Harper’s in 1998, about ten years before he eventually took his own life.

Here it is.

3. Brief Interviews with Hideous Men

After reading “The Depressed Person,” you might be completely disinterested in trying to read another short story by Wallace. Well, try this one out. It’s one among many fictional brief interviews with unnamed men, and this one is arguably the best.

This Brief Interview is actually the twentieth in the series , but there is no need to read the first nineteen in order to read this one. The only thing linking these is their style and that their subject matter is hideous men.

You should note that, if you like this, both it and “The Depressed Person” are collected, along with the other interviews, in Brief Interviews with Hideous Men.

4. 9/11: The View from the Midwest

Would you like to try another essay? Maybe? You might be reluctant, as the title of this one definitely doesn’t promise much laughter.

Surprisingly, there are a few laughs to be had in this reflection on September 11th. It also might remind you of things you had forgotten from that day, as it brings you back to the bizarre state of shared nationwide grief. It was also, as the author says at the beginning, “Written very fast and in what probably qualifies as shock” for Rolling Stone.

5. Shipping Out: On the (nearly lethal) comforts of a luxury cruise

Here’s another one published in Harper’s. It’s also an essay, but with the same amused first person narrator who accompanied us to the Maine Lobster Festival. This time he’s on a cruise ship, and it’s amazing.

“I’ve seen nearly naked a lot of people I’d prefer not to have seen nearly naked.” Trust me. You definitely want to read this essay.

Extra Credit: Infinite Jest

No, you won’t find this one for free, other than at your local library, where there will probably be a waiting list. But after you make it through the three essays and two short stories above, you might crave more, and this is one of the many books that will be waiting for you.

I would recommend sticking with reading his collected essays and stories from your local libraries and bookstores. Not that Infinite Jest is bad. I just don’t know, because no one has ever read it.

Enjoy reading this? Check out Happy Black Friday 2015 from David Foster Wallace or Books by D. F. Lovett

Share this:, leave a reply cancel reply, discover more from what would bale do.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now.

Javascript is not enabled in your browser. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser

The Best American Essays 2007

Paperback (2007 ed.)

- $19.95

- SHIP THIS ITEM Qualifies for Free Shipping Instant Purchase

Available within 2 business hours

- Want it Today? Check Store Availability

Related collections and offers

Product details, about the author, read an excerpt, table of contents.

Date of Birth:

Date of Death:

Place of Birth:

Place of Death: