Global Education

By Hannah Ritchie, Veronika Samborska, Natasha Ahuja, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Max Roser

A good education offers individuals the opportunity to lead richer, more interesting lives. At a societal level, it creates opportunities for humanity to solve its pressing problems.

The world has gone through a dramatic transition over the last few centuries, from one where very few had any basic education to one where most people do. This is not only reflected in the inputs to education – enrollment and attendance – but also in outcomes, where literacy rates have greatly improved.

Getting children into school is also not enough. What they learn matters. There are large differences in educational outcomes : in low-income countries, most children cannot read by the end of primary school. These inequalities in education exacerbate poverty and existing inequalities in global incomes .

On this page, you can find all of our writing and data on global education.

Key insights on Global Education

The world has made substantial progress in increasing basic levels of education.

Access to education is now seen as a fundamental right – in many cases, it’s the government’s duty to provide it.

But formal education is a very recent phenomenon. In the chart, we see the share of the adult population – those older than 15 – that has received some basic education and those who haven’t.

In the early 1800s, fewer than 1 in 5 adults had some basic education. Education was a luxury; in all places, it was only available to a small elite.

But you can see that this share has grown dramatically, such that this ratio is now reversed. Less than 1 in 5 adults has not received any formal education.

This is reflected in literacy data , too: 200 years ago, very few could read and write. Now most adults have basic literacy skills.

What you should know about this data

- Basic education is defined as receiving some kind of formal primary, secondary, or tertiary (post-secondary) education.

- This indicator does not tell us how long a person received formal education. They could have received a full program of schooling, or may only have been in attendance for a short period. To account for such differences, researchers measure the mean years of schooling or the expected years of schooling .

Despite being in school, many children learn very little

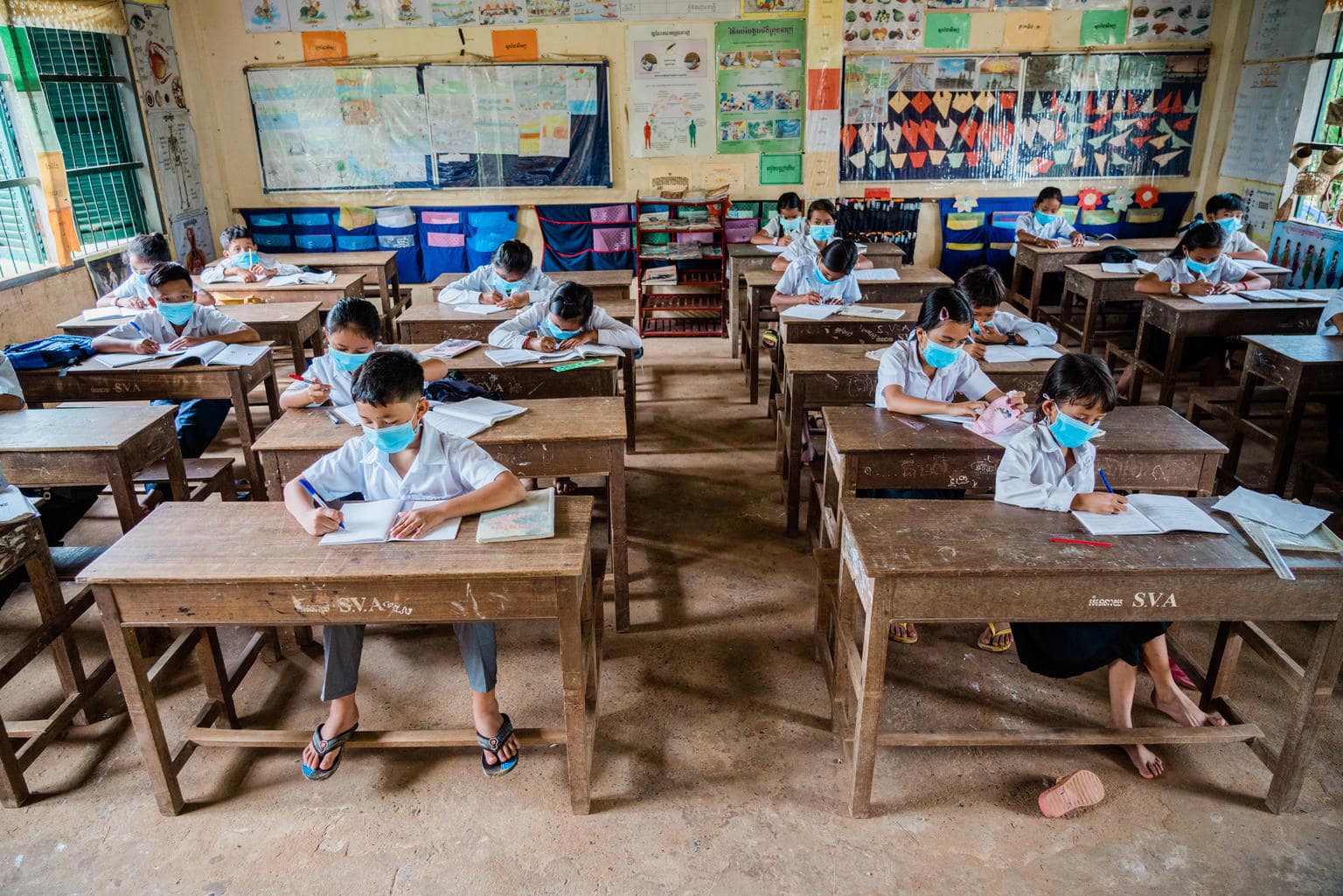

International statistics often focus on attendance as the marker of educational progress.

However, being in school does not guarantee that a child receives high-quality education. In fact, in many countries, the data shows that children learn very little.

Just half – 48% – of the world’s children can read with comprehension by the end of primary school. It’s based on data collected over a 9-year period, with 2016 as the average year of collection.

This is shown in the chart, where we plot averages across countries with different income levels. 1

The situation in low-income countries is incredibly worrying, with 90% of children unable to read by that age.

This can be improved – even among high-income countries. The best-performing countries have rates as low as 2%. That’s more than four times lower than the average across high-income countries.

Making sure that every child gets to go to school is essential. But the world also needs to focus on what children learn once they’re in the classroom.

Millions of children learn only very little. How can the world provide a better education to the next generation?

Research suggests that many children – especially in the world’s poorest countries – learn only very little in school. What can we do to improve this?

- This data does not capture total literacy over someone’s lifetime. Many children will learn to read eventually, even if they cannot read by the end of primary school. However, this means they are in a constant state of “catching up” and will leave formal education far behind where they could be.

Children across the world receive very different amounts of quality learning

There are still significant inequalities in the amount of education children get across the world.

This can be measured as the total number of years that children spend in school. However, researchers can also adjust for the quality of education to estimate how many years of quality learning they receive. This is done using an indicator called “learning-adjusted years of schooling”.

On the map, you see vast differences across the world.

In many of the world’s poorest countries, children receive less than three years of learning-adjusted schooling. In most rich countries, this is more than 10 years.

Across most countries in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa – where the largest share of children live – the average years of quality schooling are less than 7.

- Learning-adjusted years of schooling merge the quantity and quality of education into one metric, accounting for the fact that similar durations of schooling can yield different learning outcomes.

- Learning-adjusted years is computed by adjusting the expected years of school based on the quality of learning, as measured by the harmonized test scores from various international student achievement testing programs. The adjustment involves multiplying the expected years of school by the ratio of the most recent harmonized test score to 625. Here, 625 signifies advanced attainment on the TIMSS (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study) test, with 300 representing minimal attainment. These scores are measured in TIMSS-equivalent units.

Hundreds of millions of children worldwide do not go to school

While most children worldwide get the opportunity to go to school, hundreds of millions still don’t.

In the chart, we see the number of children who aren’t in school across primary and secondary education.

This number was around 260 million in 2019.

Many children who attend primary school drop out and do not attend secondary school. That means many more children or adolescents are missing from secondary school than primary education.

Access to basic education: almost 60 million children of primary school age are not in school

The world has made a lot of progress in recent generations, but millions of children are still not in school.

The gender gap in school attendance has closed across most of the world

Globally, until recently, boys were more likely to attend school than girls. The world has focused on closing this gap to ensure every child gets the opportunity to go to school.

Today, these gender gaps have largely disappeared. In the chart, we see the difference in the global enrollment rates for primary, secondary, and tertiary (post-secondary) education. The share of children who complete primary school is also shown.

We see these lines converging over time, and recently they met: rates between boys and girls are the same.

For tertiary education, young women are now more likely than young men to be enrolled.

While the differences are small globally, there are some countries where the differences are still large: girls in Afghanistan, for example, are much less likely to go to school than boys.

Research & Writing

Talent is everywhere, opportunity is not. We are all losing out because of this.

Access to basic education: almost 60 million children of primary school age are not in school, interactive charts on global education.

This data comes from a paper by João Pedro Azevedo et al.

João Pedro Azevedo, Diana Goldemberg, Silvia Montoya, Reema Nayar, Halsey Rogers, Jaime Saavedra, Brian William Stacy (2021) – “ Will Every Child Be Able to Read by 2030? Why Eliminating Learning Poverty Will Be Harder Than You Think, and What to Do About It .” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 9588, March 2021.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

BibTeX citation

Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license . You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Our World in Data is free and accessible for everyone.

Help us do this work by making a donation.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

How dating sites automate sexual racism

Forget ‘doomers.’ Warming can be stopped, top climate scientist says

Finding middle way out of Gaza war

How covid taught america about inequity in education.

Harvard Correspondent

Remote learning turned spotlight on gaps in resources, funding, and tech — but also offered hints on reform

“Unequal” is a multipart series highlighting the work of Harvard faculty, staff, students, alumni, and researchers on issues of race and inequality across the U.S. This part looks at how the pandemic called attention to issues surrounding the racial achievement gap in America.

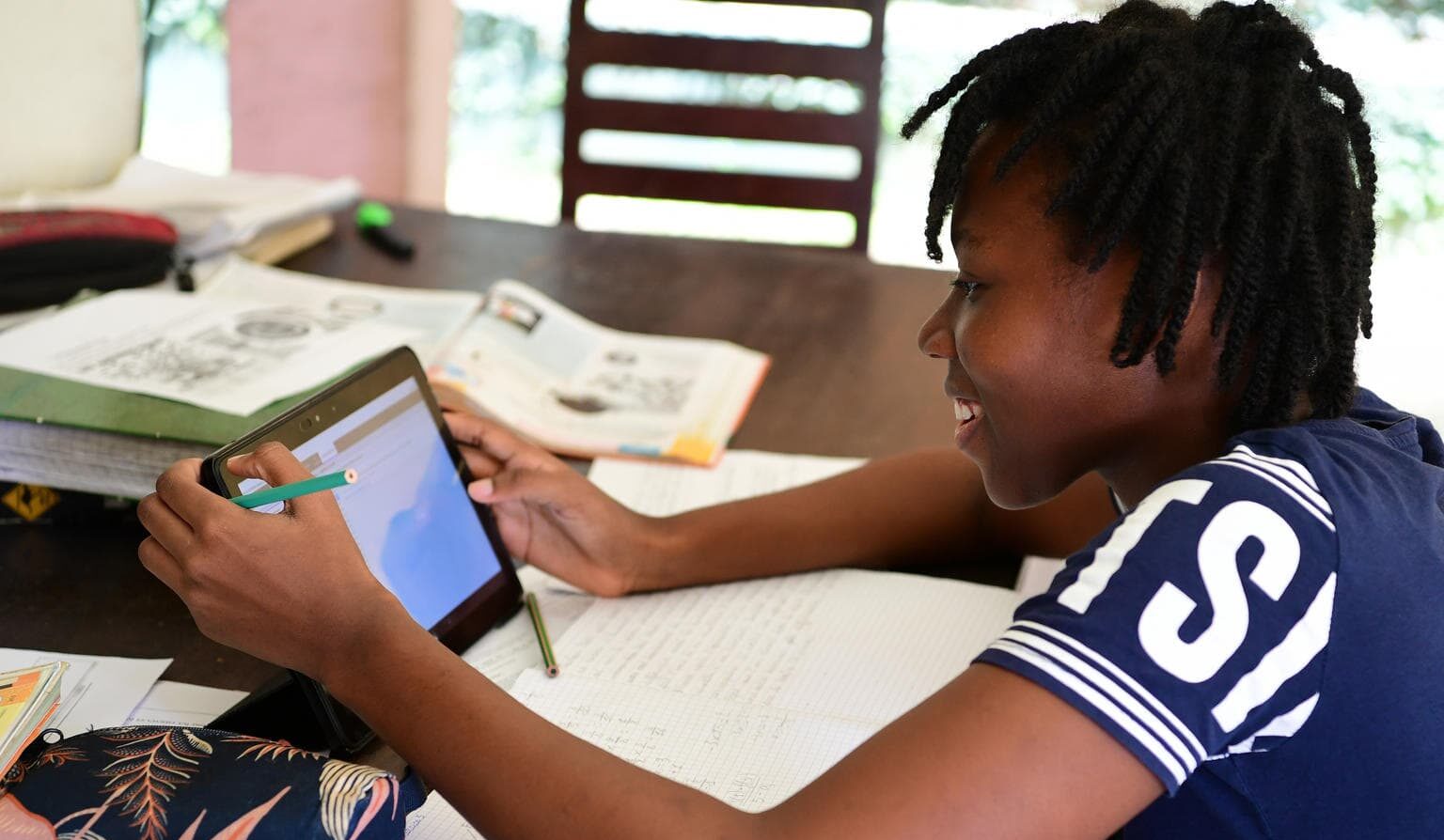

The pandemic has disrupted education nationwide, turning a spotlight on existing racial and economic disparities, and creating the potential for a lost generation. Even before the outbreak, students in vulnerable communities — particularly predominately Black, Indigenous, and other majority-minority areas — were already facing inequality in everything from resources (ranging from books to counselors) to student-teacher ratios and extracurriculars.

The additional stressors of systemic racism and the trauma induced by poverty and violence, both cited as aggravating health and wellness as at a Weatherhead Institute panel , pose serious obstacles to learning as well. “Before the pandemic, children and families who are marginalized were living under such challenging conditions that it made it difficult for them to get a high-quality education,” said Paul Reville, founder and director of the Education Redesign Lab at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (GSE).

Educators hope that the may triggers a broader conversation about reform and renewed efforts to narrow the longstanding racial achievement gap. They say that research shows virtually all of the nation’s schoolchildren have fallen behind, with students of color having lost the most ground, particularly in math. They also note that the full-time reopening of schools presents opportunities to introduce changes and that some of the lessons from remote learning, particularly in the area of technology, can be put to use to help students catch up from the pandemic as well as to begin to level the playing field.

The disparities laid bare by the COVID-19 outbreak became apparent from the first shutdowns. “The good news, of course, is that many schools were very fast in finding all kinds of ways to try to reach kids,” said Fernando M. Reimers , Ford Foundation Professor of the Practice in International Education and director of GSE’s Global Education Innovation Initiative and International Education Policy Program. He cautioned, however, that “those arrangements don’t begin to compare with what we’re able to do when kids could come to school, and they are particularly deficient at reaching the most vulnerable kids.” In addition, it turned out that many students simply lacked access.

“We’re beginning to understand that technology is a basic right. You cannot participate in society in the 21st century without access to it,” says Fernando Reimers of the Graduate School of Education.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

The rate of limited digital access for households was at 42 percent during last spring’s shutdowns, before drifting down to about 31 percent this fall, suggesting that school districts improved their adaptation to remote learning, according to an analysis by the UCLA Center for Neighborhood Knowledge of U.S. Census data. (Indeed, Education Week and other sources reported that school districts around the nation rushed to hand out millions of laptops, tablets, and Chromebooks in the months after going remote.)

The report also makes clear the degree of racial and economic digital inequality. Black and Hispanic households with school-aged children were 1.3 to 1.4 times as likely as white ones to face limited access to computers and the internet, and more than two in five low-income households had only limited access. It’s a problem that could have far-reaching consequences given that young students of color are much more likely to live in remote-only districts.

“We’re beginning to understand that technology is a basic right,” said Reimers. “You cannot participate in society in the 21st century without access to it.” Too many students, he said, “have no connectivity. They have no devices, or they have no home circumstances that provide them support.”

The issues extend beyond the technology. “There is something wonderful in being in contact with other humans, having a human who tells you, ‘It’s great to see you. How are things going at home?’” Reimers said. “I’ve done 35 case studies of innovative practices around the world. They all prioritize social, emotional well-being. Checking in with the kids. Making sure there is a touchpoint every day between a teacher and a student.”

The difference, said Reville, is apparent when comparing students from different economic circumstances. Students whose parents “could afford to hire a tutor … can compensate,” he said. “Those kids are going to do pretty well at keeping up. Whereas, if you’re in a single-parent family and mom is working two or three jobs to put food on the table, she can’t be home. It’s impossible for her to keep up and keep her kids connected.

“If you lose the connection, you lose the kid.”

“COVID just revealed how serious those inequities are,” said GSE Dean Bridget Long , the Saris Professor of Education and Economics. “It has disproportionately hurt low-income students, students with special needs, and school systems that are under-resourced.”

This disruption carries throughout the education process, from elementary school students (some of whom have simply stopped logging on to their online classes) through declining participation in higher education. Community colleges, for example, have “traditionally been a gateway for low-income students” into the professional classes, said Long, whose research focuses on issues of affordability and access. “COVID has just made all of those issues 10 times worse,” she said. “That’s where enrollment has fallen the most.”

In addition to highlighting such disparities, these losses underline a structural issue in public education. Many schools are under-resourced, and the major reason involves sources of school funding. A 2019 study found that predominantly white districts got $23 billion more than their non-white counterparts serving about the same number of students. The discrepancy is because property taxes are the primary source of funding for schools, and white districts tend to be wealthier than those of color.

The problem of resources extends beyond teachers, aides, equipment, and supplies, as schools have been tasked with an increasing number of responsibilities, from the basics of education to feeding and caring for the mental health of both students and their families.

“You think about schools and academics, but what COVID really made clear was that schools do so much more than that,” said Long. A child’s school, she stressed “is social, emotional support. It’s safety. It’s the food system. It is health care.”

“You think about schools and academics” … but a child’s school “is social, emotional support. It’s safety. It’s the food system. It is health care,” stressed GSE Dean Bridget Long.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

This safety net has been shredded just as more students need it. “We have 400,000 deaths and those are disproportionately affecting communities of color,” said Long. “So you can imagine the kids that are in those households. Are they able to come to school and learn when they’re dealing with this trauma?”

The damage is felt by the whole families. In an upcoming paper, focusing on parents of children ages 5 to 7, Cindy H. Liu, director of Harvard Medical School’s Developmental Risk and Cultural Disparities Laboratory , looks at the effects of COVID-related stress on parent’ mental health. This stress — from both health risks and grief — “likely has ramifications for those groups who are disadvantaged, particularly in getting support, as it exacerbates existing disparities in obtaining resources,” she said via email. “The unfortunate reality is that the pandemic is limiting the tangible supports [like childcare] that parents might actually need.”

Educators are overwhelmed as well. “Teachers are doing a phenomenal job connecting with students,” Long said about their performance online. “But they’ve lost the whole system — access to counselors, access to additional staff members and support. They’ve lost access to information. One clue is that the reporting of child abuse going down. It’s not that we think that child abuse is actually going down, but because you don’t have a set of adults watching and being with kids, it’s not being reported.”

The repercussions are chilling. “As we resume in-person education on a normal basis, we’re dealing with enormous gaps,” said Reville. “Some kids will come back with such educational deficits that unless their schools have a very well thought-out and effective program to help them catch up, they will never catch up. They may actually drop out of school. The immediate consequences of learning loss and disengagement are going to be a generation of people who will be less educated.”

There is hope, however. Just as the lockdown forced teachers to improvise, accelerating forms of online learning, so too may the recovery offer options for educational reform.

The solutions, say Reville, “are going to come from our community. This is a civic problem.” He applauded one example, the Somerville, Mass., public library program of outdoor Wi-Fi “pop ups,” which allow 24/7 access either through their own or library Chromebooks. “That’s the kind of imagination we need,” he said.

On a national level, he points to the creation of so-called “Children’s Cabinets.” Already in place in 30 states, these nonpartisan groups bring together leaders at the city, town, and state levels to address children’s needs through schools, libraries, and health centers. A July 2019 “ Children’s Cabinet Toolkit ” on the Education Redesign Lab site offers guidance for communities looking to form their own, with sample mission statements from Denver, Minneapolis, and Fairfax, Va.

Already the Education Redesign Lab is working on even more wide-reaching approaches. In Tennessee, for example, the Metro Nashville Public Schools has launched an innovative program, designed to provide each student with a personalized education plan. By pairing these students with school “navigators” — including teachers, librarians, and instructional coaches — the program aims to address each student’s particular needs.

“This is a chance to change the system,” said Reville. “By and large, our school systems are organized around a factory model, a one-size-fits-all approach. That wasn’t working very well before, and it’s working less well now.”

“Students have different needs,” agreed Long. “We just have to get a better understanding of what we need to prioritize and where students are” in all aspects of their home and school lives.

“By and large, our school systems are organized around a factory model, a one-size-fits-all approach. That wasn’t working very well before, and it’s working less well now,” says Paul Reville of the GSE.

Already, educators are discussing possible responses. Long and GSE helped create The Principals’ Network as one forum for sharing ideas, for example. With about 1,000 members, and multiple subgroups to address shared community issues, some viable answers have begun to emerge.

“We are going to need to expand learning time,” said Long. Some school systems, notably Texas’, already have begun discussing extending the school year, she said. In addition, Long, an internationally recognized economist who is a member of the National Academy of Education and the MDRC board, noted that educators are exploring innovative ways to utilize new tools like Zoom, even when classrooms reopen.

“This is an area where technology can help supplement what students are learning, giving them extra time — learning time, even tutoring time,” Long said.

Reimers, who serves on the UNESCO Commission on the Future of Education, has been brainstorming solutions that can be applied both here and abroad. These include urging wealthier countries to forgive loans, so that poorer countries do not have to cut back on basics such as education, and urging all countries to keep education a priority. The commission and its members are also helping to identify good practices and share them — globally.

Innovative uses of existing technology can also reach beyond traditional schooling. Reimers cites the work of a few former students who, working with Harvard Global Education Innovation Initiative, HundrED , the OECD Directorate for Education and Skills , and the World Bank Group Education Global Practice, focused on podcasts to reach poor students in Colombia.

They began airing their math and Spanish lessons via the WhatsApp app, which was widely accessible. “They were so humorous that within a week, everyone was listening,” said Reimers. Soon, radio stations and other platforms began airing the 10-minute lessons, reaching not only children who were not in school, but also their adult relatives.

Share this article

You might like.

Sociologist’s new book finds algorithms that suggest partners often reflect stereotypes, biases

Michael Mann points to prehistoric catastrophes, modern environmental victories

Educators, activists explore peacebuilding based on shared desires for ‘freedom and equality and independence’ at Weatherhead panel

College accepts 1,937 to Class of 2028

Students represent 94 countries, all 50 states

Pushing back on DEI ‘orthodoxy’

Panelists support diversity efforts but worry that current model is too narrow, denying institutions the benefit of other voices, ideas

We use cookies. Read more about them in our Privacy Policy.

- Accept site cookies

- Reject site cookies

Search results:

- Afghanistan

- Africa (African Union)

- African Union

- American Samoa

- Antigua and Barbuda

- Bolivia (Plurinational State of)

- Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- British Virgin Islands

- Brunei Darussalam

- Burkina Faso

- Cayman Islands

- Central Africa (African Union)

- Central African Republic

- Channel Islands

- China, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

- China, Macao Special Administrative Region

- China, Taiwan Province of China

- Cook Islands

- Côte d'Ivoire

- Democratic People's Republic of Korea

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Dominican Republic

- Eastern Africa (African Union)

- El Salvador

- Equatorial Guinea

- Falkland Islands (Malvinas)

- Faroe Islands

- French Guiana

- French Polynesia

- Guinea-Bissau

- Humanitarian Action Countries

- Iran (Islamic Republic of)

- Isle of Man

- Kosovo (UNSCR 1244)

- Lao People's Democratic Republic

- Liechtenstein

- Marshall Islands

- Micronesia (Federated States of)

- Netherlands (Kingdom of the)

- New Caledonia

- New Zealand

- North Macedonia

- Northern Africa (African Union)

- Northern Mariana Islands

- OECD Fragile Contexts

- Papua New Guinea

- Philippines

- Puerto Rico

- Republic of Korea

- Republic of Moldova

- Russian Federation

- Saint Barthélemy

- Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha

- Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Saint Lucia

- Saint Martin (French part)

- Saint Pierre and Miquelon

- Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- Sao Tome and Principe

- Saudi Arabia

- Sierra Leone

- Sint Maarten

- Solomon Islands

- South Africa

- South Sudan

- Southern Africa (African Union)

- State of Palestine

- Switzerland

- Syrian Arab Republic

- Timor-Leste

- Trinidad and Tobago

- Turkmenistan

- Turks and Caicos Islands

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United Republic of Tanzania

- United States

- Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of)

- Virgin Islands U.S.

- Wallis and Futuna

- Western Africa (African Union)

Search countries

Search for data in 245 countries

- SDG Progress Data

- Child Marriage

- Immunization

- Benchmarking child-related SDGs

- Maternal and Newborn Health Disparities

- Continuity of essential health services

- Country profiles

- Interactive data visualizations

- Journal articles

- Publications

- Data Warehouse

Education overview

- Current status

- Available data

- Recent resources

- Notes on the data

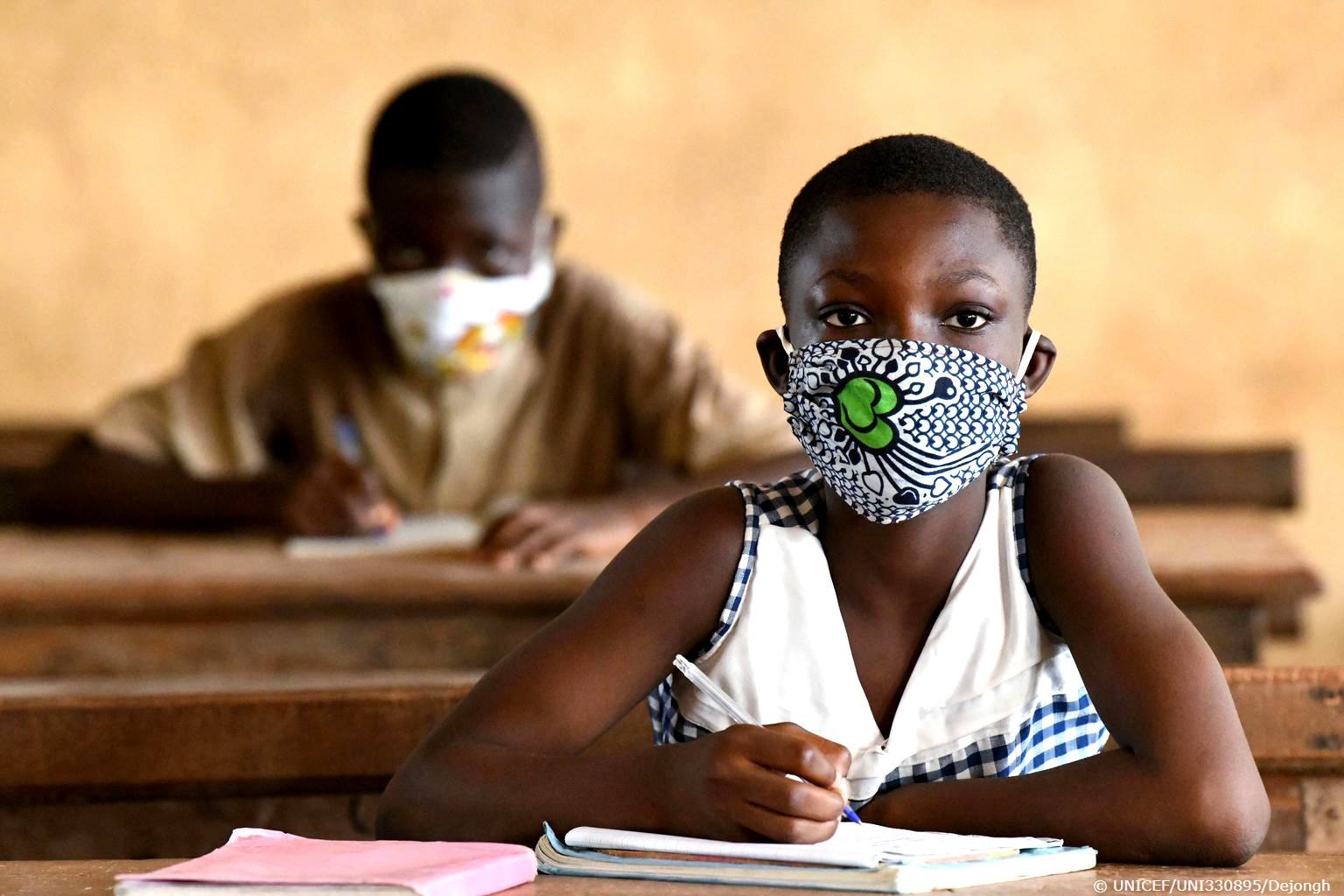

Education is vital to meeting the Sustainable Development Goals

Every child learns. The Sustainable Development Goals are interdependent and achieving SDG4 – ensuring inclusive and equitable education for all by 2030 – will have transformative effects on other goals. SDG4 spans a spectrum of education levels, from pre-primary to youth and adult education. It emphasizes learning outcomes, skills acquisition, and equity in both development and emergency settings. UNICEF advocates high-quality, child-friendly basic education for all, in line with the ambition of the Global Education 2030 Agenda. To meet the vision brought forth by the Education 2030 Framework of Action and SDG4, UNICEF released its own Education Strategy 2019–2030 , ‘Every Child Learns’, outlining three distinct goals: (1) Equitable access to learning opportunities; (2) Improved learning and skills for all; and (3) Improved learning and protection for children in emergencies and fragile contexts.

Education data

Are children really learning exploring foundational skills in the midst of a learning crisis.

The State of Global Education: From crisis to recovery

Education for children with disabilities

Ensuring equal access to education in future crises: Findings of the new Remote Learning Readiness Index

Education disrupted: The second year of the COVID-19 pandemic and school closures

How are children progressing through school? An Education Pathway Analysis

Which children have internet access at home? Insights from household survey data (blog post)

How many children and young people have internet access at home?

Georgia education fact sheets

What Have We Learnt? Findings from a survey of ministries of education on national responses to COVID-19

EduView Dashboard

COVID-19: Are children able to continue learning during school closures?

Promising practices for equitable remote learning: Emerging lessons from COVID-19 education responses in 127 countries

Guidelines for adapting the Foundational Learning Module to non-multiple indicator cluster household surveys

MICS – Education Analysis for Global Learning and Equity

A Future Stolen: Young and out-of-school

Fixing the Broken Promise of Education for All – Findings from the Global Initiative on Out-of-School Children

Suriname education fact sheets

UNICEF strategic plan country and regional education profiles

Lao PDR education country report

Notes on the Data

Definition of indicators.

Gender parity index – The ratio of female-to-male values of a given indicator. A GPI of 1 indicates parity between the sexes.

Literacy rate – Total number of literate persons in a given age group, expressed as a percentage of the total population in that age group. The adult literacy rate measures literacy among persons aged 15 years and older, and the youth literacy rate measures literacy among persons aged 15 to 24 years.

Out-of-school population – Total number of primary or lower secondary-school-age children who are not enrolled in primary (ISCED 1) or secondary (ISCED 2 and 3) education.

Pre-primary school gross enrolment ratio – Number of children enrolled in pre-primary school, regardless of age, expressed as a percentage of the total number of children of official pre-primary school age.

Primary school gross enrolment ratio – Number of children enrolled in primary school, regardless of age, expressed as a percentage of the total number of children of official primary school age.

Primary school net attendance ratio – Number of children attending primary or secondary school who are of official primary school age, expressed as a percentage of the total number of children of official primary school age. Because of the inclusion of primary-school-age children attending secondary school, this indicator can also be referred to as a primary adjusted net attendance ratio.

Primary school net enrolment ratio – Number of children enrolled in primary or secondary school who are of official primary school age, expressed as a percentage of the total number of children of official primary school age. Because of the inclusion of primary-school-age children enrolled in secondary school, this indicator can also be referred to as a primary adjusted net enrolment ratio.

Secondary school net attendance ratio – Number of children attending secondary or tertiary school who are of official secondary school age, expressed as a percentage of the total number of children of official secondary school age. Because of the inclusion of secondary-school-age children attending tertiary school, this indicator can also be referred to as a secondary adjusted net attendance ratio.

Secondary school net enrolment ratio – Number of children enrolled in secondary school who are of official secondary school age, expressed as a percentage of the total number of children of official secondary school age. Secondary net enrolment ratio does not include secondary-school-age children enrolled in tertiary education, owing to challenges in age reporting and recording at that level.

Survival rate to last primary grade – Percentage of children entering the first grade of primary school who eventually reach the last grade of primary school.

Related Topics

- Pre-primary education

- Primary education

- Secondary education

- Learning and skills

- Remote learning and digital connectivity

Join our community

Receive the latest updates from the UNICEF Data team

- Don’t miss out on our latest data

- Get insights based on your interests

The dataset you are about to download is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license.

Sorry, we did not find any matching results.

We frequently add data and we're interested in what would be useful to people. If you have a specific recommendation, you can reach us at [email protected] .

We are in the process of adding data at the state and local level. Sign up on our mailing list here to be the first to know when it is available.

Search tips:

• Check your spelling

• Try other search terms

• Use fewer words

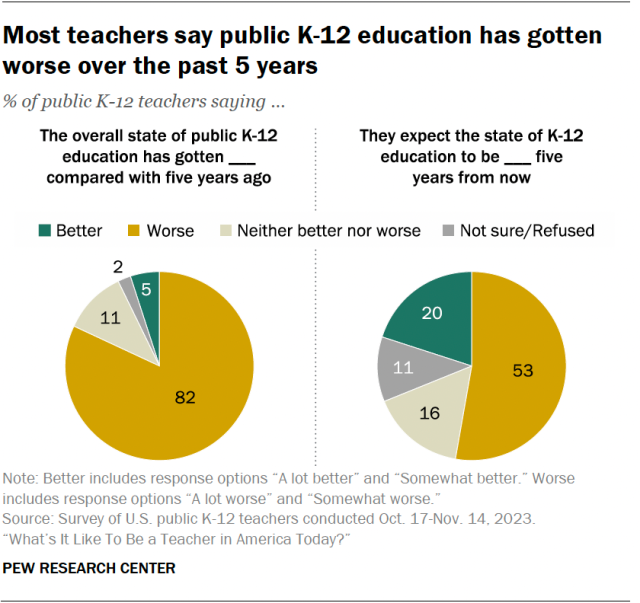

What are the outcomes of the education system? How much did COVID-19 disrupt learning?

Eighth-grade math and reading proficiency fell between 2019 and 2022 to the lowest rates in at least 15 years..

The share of eighth graders at or above a proficient reading level dropped from 34% to 31%. For math, it dropped from 34% to 26%.

The public-school student-teacher ratio dropped from 15.9 in fall 2019 to 15.4 in fall 2020 and remained unchanged in 2021.

This is partly due to declining school enrollment during the pandemic . Several factors affect the student-teacher ratio, including class sizes, the number of classes educators teach, and the number of special education teachers.

Public schools spent an average of $16,280 per student in the 2020–2021 school year, more than any previous year after adjusting for inflation.

This was up 3.5% from the previous school year, the largest single-year increase since 1988-1989. Expenditures in 2019-2020 and 2020-2021 included funds allocated through pandemic relief legislation such as the CARES Act . Many factors influence per-pupil spending, including salaries, benefits, and supplies across functions such as instruction, administration, and operations and maintenance.

Of the students who started high school in 2011, 24% completed a four-year college degree by 2021. Another 13% had enrolled in a four-year college within one year of high school graduation but had not completed their degree.

Among Black and Hispanic students who entered high school in 2011, the percentage who earned a four-year degree by 2021 was lower than the overall student rate — less than 15% for either group.

The median student loan balance per household decreased between 2019 and 2022, but it dropped most for Black-led households, falling 25% to $27,070 in 2022.

However, prior to 2022, it had been increasing faster for Black-led households than households overall. Black-led household student loan balances rose 66% between 2010 and 2019, compared to 41% for all families.

Forty-eight percent of the population ages 25 and older has a college degree.

Asian Americans have the nation’s highest levels of education; as of 2022, two-thirds had at least an associate degree.

Get facts first

Unbiased, data-driven insights in your inbox each week

You are signed up for the facts!

On average, people whose highest level of education is a bachelor’s degree earned $1,493 per week in 2023, roughly 66% more than workers with a high school diploma.

Earnings for workers with some college or an associate degree have fallen since 2000, while increasing for all other educational attainment categories. Earnings for people without a high school diploma are up most, $708 per week (up 11%), but remain $462 per week (39%), lower than overall median earnings.

Continue exploring the State of the Union

What is the state of the military, and how are us veterans faring.

Infrastructure

What does America spend on transportation and infrastructure? Is infrastructure improving?

Explore more of usafacts, related articles, how many black male teachers are there in the us, how many us children receive a free or reduced-price school lunch, which states have the highest and lowest adult literacy rates, what role do schools play in addressing youth mental health, related data, head start funding.

$10.61 billion

College enrollment rate

High school dropout rate, average public school teacher salary, data delivered to your inbox.

Keep up with the latest data and most popular content.

SIGN UP FOR THE NEWSLETTER

The World Bank Group is the largest financier of education in the developing world, working in 90 countries and committed to helping them reach SDG4: access to inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning opportunities for all by 2030.

Education is a human right, a powerful driver of development, and one of the strongest instruments for reducing poverty and improving health, gender equality, peace, and stability. It delivers large, consistent returns in terms of income, and is the most important factor to ensure equity and inclusion.

For individuals, education promotes employment, earnings, health, and poverty reduction. Globally, there is a 9% increase in hourly earnings for every extra year of schooling . For societies, it drives long-term economic growth, spurs innovation, strengthens institutions, and fosters social cohesion. Education is further a powerful catalyst to climate action through widespread behavior change and skilling for green transitions.

Developing countries have made tremendous progress in getting children into the classroom and more children worldwide are now in school. But learning is not guaranteed, as the 2018 World Development Report (WDR) stressed.

Making smart and effective investments in people’s education is critical for developing the human capital that will end extreme poverty. At the core of this strategy is the need to tackle the learning crisis, put an end to Learning Poverty , and help youth acquire the advanced cognitive, socioemotional, technical and digital skills they need to succeed in today’s world.

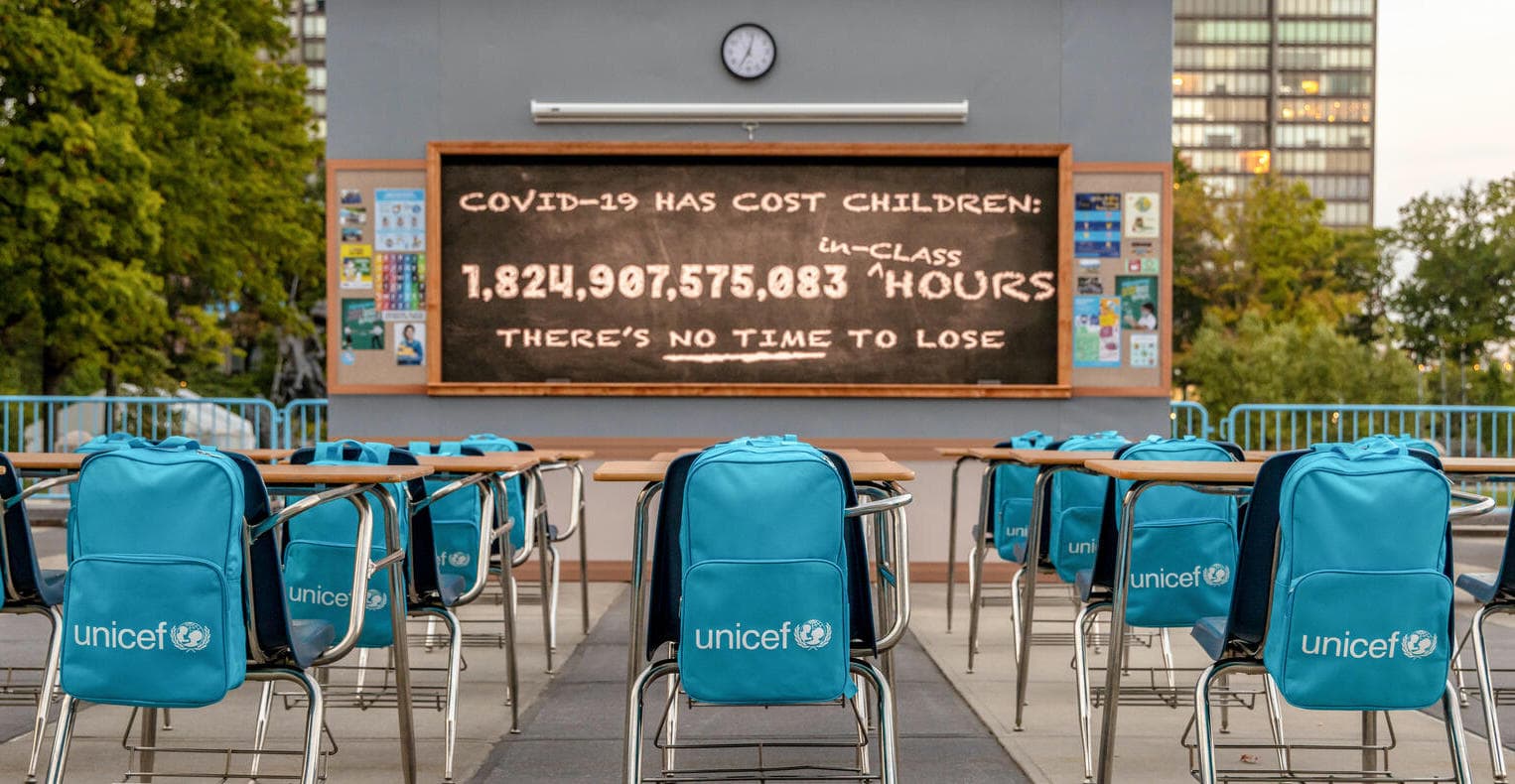

In low- and middle-income countries, the share of children living in Learning Poverty (that is, the proportion of 10-year-old children that are unable to read and understand a short age-appropriate text) increased from 57% before the pandemic to an estimated 70% in 2022.

However, learning is in crisis. More than 70 million more people were pushed into poverty during the COVID pandemic, a billion children lost a year of school , and three years later the learning losses suffered have not been recouped . If a child cannot read with comprehension by age 10, they are unlikely to become fluent readers. They will fail to thrive later in school and will be unable to power their careers and economies once they leave school.

The effects of the pandemic are expected to be long-lasting. Analysis has already revealed deep losses, with international reading scores declining from 2016 to 2021 by more than a year of schooling. These losses may translate to a 0.68 percentage point in global GDP growth. The staggering effects of school closures reach beyond learning. This generation of children could lose a combined total of US$21 trillion in lifetime earnings in present value or the equivalent of 17% of today’s global GDP – a sharp rise from the 2021 estimate of a US$17 trillion loss.

Action is urgently needed now – business as usual will not suffice to heal the scars of the pandemic and will not accelerate progress enough to meet the ambitions of SDG 4. We are urging governments to implement ambitious and aggressive Learning Acceleration Programs to get children back to school, recover lost learning, and advance progress by building better, more equitable and resilient education systems.

Last Updated: Mar 25, 2024

The World Bank’s global education strategy is centered on ensuring learning happens – for everyone, everywhere. Our vision is to ensure that everyone can achieve her or his full potential with access to a quality education and lifelong learning. To reach this, we are helping countries build foundational skills like literacy, numeracy, and socioemotional skills – the building blocks for all other learning. From early childhood to tertiary education and beyond – we help children and youth acquire the skills they need to thrive in school, the labor market and throughout their lives.

Investing in the world’s most precious resource – people – is paramount to ending poverty on a livable planet. Our experience across more than 100 countries bears out this robust connection between human capital, quality of life, and economic growth: when countries strategically invest in people and the systems designed to protect and build human capital at scale, they unlock the wealth of nations and the potential of everyone.

Building on this, the World Bank supports resilient, equitable, and inclusive education systems that ensure learning happens for everyone. We do this by generating and disseminating evidence, ensuring alignment with policymaking processes, and bridging the gap between research and practice.

The World Bank is the largest source of external financing for education in developing countries, with a portfolio of about $26 billion in 94 countries including IBRD, IDA and Recipient-Executed Trust Funds. IDA operations comprise 62% of the education portfolio.

The investment in FCV settings has increased dramatically and now accounts for 26% of our portfolio.

World Bank projects reach at least 425 million students -one-third of students in low- and middle-income countries.

The World Bank’s Approach to Education

Five interrelated pillars of a well-functioning education system underpin the World Bank’s education policy approach:

- Learners are prepared and motivated to learn;

- Teachers are prepared, skilled, and motivated to facilitate learning and skills acquisition;

- Learning resources (including education technology) are available, relevant, and used to improve teaching and learning;

- Schools are safe and inclusive; and

- Education Systems are well-managed, with good implementation capacity and adequate financing.

The Bank is already helping governments design and implement cost-effective programs and tools to build these pillars.

Our Principles:

- We pursue systemic reform supported by political commitment to learning for all children.

- We focus on equity and inclusion through a progressive path toward achieving universal access to quality education, including children and young adults in fragile or conflict affected areas , those in marginalized and rural communities, girls and women , displaced populations, students with disabilities , and other vulnerable groups.

- We focus on results and use evidence to keep improving policy by using metrics to guide improvements.

- We want to ensure financial commitment commensurate with what is needed to provide basic services to all.

- We invest wisely in technology so that education systems embrace and learn to harness technology to support their learning objectives.

Laying the groundwork for the future

Country challenges vary, but there is a menu of options to build forward better, more resilient, and equitable education systems.

Countries are facing an education crisis that requires a two-pronged approach: first, supporting actions to recover lost time through remedial and accelerated learning; and, second, building on these investments for a more equitable, resilient, and effective system.

Recovering from the learning crisis must be a political priority, backed with adequate financing and the resolve to implement needed reforms. Domestic financing for education over the last two years has not kept pace with the need to recover and accelerate learning. Across low- and lower-middle-income countries, the average share of education in government budgets fell during the pandemic , and in 2022 it remained below 2019 levels.

The best chance for a better future is to invest in education and make sure each dollar is put toward improving learning. In a time of fiscal pressure, protecting spending that yields long-run gains – like spending on education – will maximize impact. We still need more and better funding for education. Closing the learning gap will require increasing the level, efficiency, and equity of education spending—spending smarter is an imperative.

- Education technology can be a powerful tool to implement these actions by supporting teachers, children, principals, and parents; expanding accessible digital learning platforms, including radio/ TV / Online learning resources; and using data to identify and help at-risk children, personalize learning, and improve service delivery.

Looking ahead

We must seize this opportunity to reimagine education in bold ways. Together, we can build forward better more equitable, effective, and resilient education systems for the world’s children and youth.

Accelerating Improvements

Supporting countries in establishing time-bound learning targets and a focused education investment plan, outlining actions and investments geared to achieve these goals.

Launched in 2020, the Accelerator Program works with a set of countries to channel investments in education and to learn from each other. The program coordinates efforts across partners to ensure that the countries in the program show improvements in foundational skills at scale over the next three to five years. These investment plans build on the collective work of multiple partners, and leverage the latest evidence on what works, and how best to plan for implementation. Countries such as Brazil (the state of Ceará) and Kenya have achieved dramatic reductions in learning poverty over the past decade at scale, providing useful lessons, even as they seek to build on their successes and address remaining and new challenges.

Universalizing Foundational Literacy

Readying children for the future by supporting acquisition of foundational skills – which are the gateway to other skills and subjects.

The Literacy Policy Package (LPP) consists of interventions focused specifically on promoting acquisition of reading proficiency in primary school. These include assuring political and technical commitment to making all children literate; ensuring effective literacy instruction by supporting teachers; providing quality, age-appropriate books; teaching children first in the language they speak and understand best; and fostering children’s oral language abilities and love of books and reading.

Advancing skills through TVET and Tertiary

Ensuring that individuals have access to quality education and training opportunities and supporting links to employment.

Tertiary education and skills systems are a driver of major development agendas, including human capital, climate change, youth and women’s empowerment, and jobs and economic transformation. A comprehensive skill set to succeed in the 21st century labor market consists of foundational and higher order skills, socio-emotional skills, specialized skills, and digital skills. Yet most countries continue to struggle in delivering on the promise of skills development.

The World Bank is supporting countries through efforts that address key challenges including improving access and completion, adaptability, quality, relevance, and efficiency of skills development programs. Our approach is via multiple channels including projects, global goods, as well as the Tertiary Education and Skills Program . Our recent reports including Building Better Formal TVET Systems and STEERing Tertiary Education provide a way forward for how to improve these critical systems.

Addressing Climate Change

Mainstreaming climate education and investing in green skills, research and innovation, and green infrastructure to spur climate action and foster better preparedness and resilience to climate shocks.

Our approach recognizes that education is critical for achieving effective, sustained climate action. At the same time, climate change is adversely impacting education outcomes. Investments in education can play a huge role in building climate resilience and advancing climate mitigation and adaptation. Climate change education gives young people greater awareness of climate risks and more access to tools and solutions for addressing these risks and managing related shocks. Technical and vocational education and training can also accelerate a green economic transformation by fostering green skills and innovation. Greening education infrastructure can help mitigate the impact of heat, pollution, and extreme weather on learning, while helping address climate change.

Examples of this work are projects in Nigeria (life skills training for adolescent girls), Vietnam (fostering relevant scientific research) , and Bangladesh (constructing and retrofitting schools to serve as cyclone shelters).

Strengthening Measurement Systems

Enabling countries to gather and evaluate information on learning and its drivers more efficiently and effectively.

The World Bank supports initiatives to help countries effectively build and strengthen their measurement systems to facilitate evidence-based decision-making. Examples of this work include:

(1) The Global Education Policy Dashboard (GEPD) : This tool offers a strong basis for identifying priorities for investment and policy reforms that are suited to each country context by focusing on the three dimensions of practices, policies, and politics.

- Highlights gaps between what the evidence suggests is effective in promoting learning and what is happening in practice in each system; and

- Allows governments to track progress as they act to close the gaps.

The GEPD has been implemented in 13 education systems already – Peru, Rwanda, Jordan, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Mozambique, Islamabad, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Sierra Leone, Niger, Gabon, Jordan and Chad – with more expected by the end of 2024.

(2) Learning Assessment Platform (LeAP) : LeAP is a one-stop shop for knowledge, capacity-building tools, support for policy dialogue, and technical staff expertise to support student achievement measurement and national assessments for better learning.

Supporting Successful Teachers

Helping systems develop the right selection, incentives, and support to the professional development of teachers.

Currently, the World Bank Education Global Practice has over 160 active projects supporting over 18 million teachers worldwide, about a third of the teacher population in low- and middle-income countries. In 12 countries alone, these projects cover 16 million teachers, including all primary school teachers in Ethiopia and Turkey, and over 80% in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Vietnam.

A World Bank-developed classroom observation tool, Teach, was designed to capture the quality of teaching in low- and middle-income countries. It is now 3.6 million students.

While Teach helps identify patterns in teacher performance, Coach leverages these insights to support teachers to improve their teaching practice through hands-on in-service teacher professional development (TPD).

Our recent report on Making Teacher Policy Work proposes a practical framework to uncover the black box of effective teacher policy and discusses the factors that enable their scalability and sustainability.

Supporting Education Finance Systems

Strengthening country financing systems to mobilize resources for education and make better use of their investments in education.

Our approach is to bring together multi-sectoral expertise to engage with ministries of education and finance and other stakeholders to develop and implement effective and efficient public financial management systems; build capacity to monitor and evaluate education spending, identify financing bottlenecks, and develop interventions to strengthen financing systems; build the evidence base on global spending patterns and the magnitude and causes of spending inefficiencies; and develop diagnostic tools as public goods to support country efforts.

Working in Fragile, Conflict, and Violent (FCV) Contexts

The massive and growing global challenge of having so many children living in conflict and violent situations requires a response at the same scale and scope. Our education engagement in the Fragility, Conflict and Violence (FCV) context, which stands at US$5.35 billion, has grown rapidly in recent years, reflecting the ever-increasing importance of the FCV agenda in education. Indeed, these projects now account for more than 25% of the World Bank education portfolio.

Education is crucial to minimizing the effects of fragility and displacement on the welfare of youth and children in the short-term and preventing the emergence of violent conflict in the long-term.

Support to Countries Throughout the Education Cycle

Our support to countries covers the entire learning cycle, to help shape resilient, equitable, and inclusive education systems that ensure learning happens for everyone.

The ongoing Supporting Egypt Education Reform project , 2018-2025, supports transformational reforms of the Egyptian education system, by improving teaching and learning conditions in public schools. The World Bank has invested $500 million in the project focused on increasing access to quality kindergarten, enhancing the capacity of teachers and education leaders, developing a reliable student assessment system, and introducing the use of modern technology for teaching and learning. Specifically, the share of Egyptian 10-year-old students, who could read and comprehend at the global minimum proficiency level, increased to 45 percent in 2021.

In Nigeria , the $75 million Edo Basic Education Sector and Skills Transformation (EdoBESST) project, running from 2020-2024, is focused on improving teaching and learning in basic education. Under the project, which covers 97 percent of schools in the state, there is a strong focus on incorporating digital technologies for teachers. They were equipped with handheld tablets with structured lesson plans for their classes. Their coaches use classroom observation tools to provide individualized feedback. Teacher absence has reduced drastically because of the initiative. Over 16,000 teachers were trained through the project, and the introduction of technology has also benefited students.

Through the $235 million School Sector Development Program in Nepal (2017-2022), the number of children staying in school until Grade 12 nearly tripled, and the number of out-of-school children fell by almost seven percent. During the pandemic, innovative approaches were needed to continue education. Mobile phone penetration is high in the country. More than four in five households in Nepal have mobile phones. The project supported an educational service that made it possible for children with phones to connect to local radio that broadcast learning programs.

From 2017-2023, the $50 million Strengthening of State Universities in Chile project has made strides to improve quality and equity at state universities. The project helped reduce dropout: the third-year dropout rate fell by almost 10 percent from 2018-2022, keeping more students in school.

The World Bank’s first Program-for-Results financing in education was through a $202 million project in Tanzania , that ran from 2013-2021. The project linked funding to results and aimed to improve education quality. It helped build capacity, and enhanced effectiveness and efficiency in the education sector. Through the project, learning outcomes significantly improved alongside an unprecedented expansion of access to education for children in Tanzania. From 2013-2019, an additional 1.8 million students enrolled in primary schools. In 2019, the average reading speed for Grade 2 students rose to 22.3 words per minute, up from 17.3 in 2017. The project laid the foundation for the ongoing $500 million BOOST project , which supports over 12 million children to enroll early, develop strong foundational skills, and complete a quality education.

The $40 million Cambodia Secondary Education Improvement project , which ran from 2017-2022, focused on strengthening school-based management, upgrading teacher qualifications, and building classrooms in Cambodia, to improve learning outcomes, and reduce student dropout at the secondary school level. The project has directly benefited almost 70,000 students in 100 target schools, and approximately 2,000 teachers and 600 school administrators received training.

The World Bank is co-financing the $152.80 million Yemen Restoring Education and Learning Emergency project , running from 2020-2024, which is implemented through UNICEF, WFP, and Save the Children. It is helping to maintain access to basic education for many students, improve learning conditions in schools, and is working to strengthen overall education sector capacity. In the time of crisis, the project is supporting teacher payments and teacher training, school meals, school infrastructure development, and the distribution of learning materials and school supplies. To date, almost 600,000 students have benefited from these interventions.

The $87 million Providing an Education of Quality in Haiti project supported approximately 380 schools in the Southern region of Haiti from 2016-2023. Despite a highly challenging context of political instability and recurrent natural disasters, the project successfully supported access to education for students. The project provided textbooks, fresh meals, and teacher training support to 70,000 students, 3,000 teachers, and 300 school directors. It gave tuition waivers to 35,000 students in 118 non-public schools. The project also repaired 19 national schools damaged by the 2021 earthquake, which gave 5,500 students safe access to their schools again.

In 2013, just 5% of the poorest households in Uzbekistan had children enrolled in preschools. Thanks to the Improving Pre-Primary and General Secondary Education Project , by July 2019, around 100,000 children will have benefitted from the half-day program in 2,420 rural kindergartens, comprising around 49% of all preschool educational institutions, or over 90% of rural kindergartens in the country.

In addition to working closely with governments in our client countries, the World Bank also works at the global, regional, and local levels with a range of technical partners, including foundations, non-profit organizations, bilaterals, and other multilateral organizations. Some examples of our most recent global partnerships include:

UNICEF, UNESCO, FCDO, USAID, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation: Coalition for Foundational Learning

The World Bank is working closely with UNICEF, UNESCO, FCDO, USAID, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation as the Coalition for Foundational Learning to advocate and provide technical support to ensure foundational learning. The World Bank works with these partners to promote and endorse the Commitment to Action on Foundational Learning , a global network of countries committed to halving the global share of children unable to read and understand a simple text by age 10 by 2030.

Australian Aid, Bernard van Leer Foundation, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Canada, Echida Giving, FCDO, German Cooperation, William & Flora Hewlett Foundation, Conrad Hilton Foundation, LEGO Foundation, Porticus, USAID: Early Learning Partnership

The Early Learning Partnership (ELP) is a multi-donor trust fund, housed at the World Bank. ELP leverages World Bank strengths—a global presence, access to policymakers and strong technical analysis—to improve early learning opportunities and outcomes for young children around the world.

We help World Bank teams and countries get the information they need to make the case to invest in Early Childhood Development (ECD), design effective policies and deliver impactful programs. At the country level, ELP grants provide teams with resources for early seed investments that can generate large financial commitments through World Bank finance and government resources. At the global level, ELP research and special initiatives work to fill knowledge gaps, build capacity and generate public goods.

UNESCO, UNICEF: Learning Data Compact

UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank have joined forces to close the learning data gaps that still exist and that preclude many countries from monitoring the quality of their education systems and assessing if their students are learning. The three organizations have agreed to a Learning Data Compact , a commitment to ensure that all countries, especially low-income countries, have at least one quality measure of learning by 2025, supporting coordinated efforts to strengthen national assessment systems.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS): Learning Poverty Indicator

Aimed at measuring and urging attention to foundational literacy as a prerequisite to achieve SDG4, this partnership was launched in 2019 to help countries strengthen their learning assessment systems, better monitor what students are learning in internationally comparable ways and improve the breadth and quality of global data on education.

FCDO, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation: EdTech Hub

Supported by the UK government’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), in partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the EdTech Hub is aimed at improving the quality of ed-tech investments. The Hub launched a rapid response Helpdesk service to provide just-in-time advisory support to 70 low- and middle-income countries planning education technology and remote learning initiatives.

MasterCard Foundation

Our Tertiary Education and Skills global program, launched with support from the Mastercard Foundation, aims to prepare youth and adults for the future of work and society by improving access to relevant, quality, equitable reskilling and post-secondary education opportunities. It is designed to reframe, reform, and rebuild tertiary education and skills systems for the digital and green transformation.

The “how to” of inclusive education policy design

Including refugees in national education systems

How generative AI can enrich teaching and learning

Areas of focus.

Digital Technologies

Early Childhood Development

Education Data & Measurement

Education Finance

Education in Fragile, Conflict & Violence Contexts

Girls’ Education

Higher Education

Inclusive Education

Initiatives

- Show More +

- Tertiary Education and Skills Program

- Service Delivery Indicators

- Evoke: Transforming education to empower youth

- Global Education Policy Dashboard

- Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel

- Show Less -

Collapse and Recovery: How the COVID-19 Pandemic Eroded Human Capital and What to Do About It

BROCHURES & FACT SHEETS

Publication: Realizing Education's Promise: A World Bank Retrospective – August 2023

Education and Climate Change flyer - November 2022

Learning Losses Brochure - October 2022

World Bank Group Education Fact Sheet - September 2022

STAY CONNECTED

Human Development Topics

Around the bank group.

Find out what the Bank Group's branches are doing in education

Global Education Newsletter - February 2024

What's happening in the World Bank Education Global Practice? Read to learn more.

Human Capital Project

The Human Capital Project is a global effort to accelerate more and better investments in people for greater equity and economic growth.

Impact Evaluations

Research that measures the impact of education policies to improve education in low and middle income countries.

Investing in People for a Livable Planet

Global thought leaders came together to champion investments in people to eradicate poverty on a livable planet.

Additional Resources

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

The alarming state of the American student in 2022

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, robin lake and robin lake director, center on reinventing public education - arizona state university @rbnlake travis pillow travis pillow innovation fellow, center on reinventing public education - arizona state university @travispillow.

November 1, 2022

The pandemic was a wrecking ball for U.S. public education, bringing months of school closures, frantic moves to remote instruction, and trauma and isolation.

Kids may be back at school after three disrupted years, but a return to classrooms has not brought a return to normal. Recent results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) showed historic declines in American students’ knowledge and skills and widening gaps between the highest- and lowest-scoring students.

But even these sobering results do not tell us the whole story.

After nearly three years of tracking pandemic response by U.S. school systems and synthesizing knowledge about the impacts on students, we sought to establish a baseline understanding of the contours of the crisis: What happened and why, and where do we go from here?

This first annual “ State of the American Student ” report synthesizes nearly three years of research on the academic, mental health, and other impacts of the pandemic and school closures.

It outlines the contours of the crisis American students have faced during the COVID-19 pandemic and begins to chart a path to recovery and reinvention for all students—which includes building a new and better approach to public education that ensures an educational crisis of this magnitude cannot happen again.

The state of American students as we emerge from the pandemic is still coming into focus, but here’s what we’ve learned (and haven’t yet learned) about where COVID-19 left us:

1. Students lost critical opportunities to learn and thrive.

• The typical American student lost several months’ worth of learning in language arts and more in mathematics.

• Students suffered crushing increases in anxiety and depression. More than one in 360 U.S. children lost a parent or caregiver to COVID-19.

• Students poorly served before the pandemic were profoundly left behind during it, including many with disabilities whose parents reported they were cut off from essential school and life services.

This deeply traumatic period threatens to reverberate for decades. The academic, social, and mental-health needs are real, they are measurable, and they must be addressed quickly to avoid long-term consequences to individual students, the future workforce, and society.

2. The average effects from COVID mask dire inequities and widely varied impact.

Some students are catching up, but time is running out for others. Every student experienced the pandemic differently, and there is tremendous variation from student to student, with certain populations—namely, Black, Hispanic, and low-income students, as well as other vulnerable populations—suffering the most severe impacts.

The effects were more severe where campuses stayed closed longer. American students are experiencing a K-shaped recovery, in which gaps between the highest- and lowest-scoring students, already growing before the pandemic, are widening into chasms. In the latest NAEP results released in September , national average scores fell five times as much in reading, and four times as much in math, for the lowest-scoring 10 percent of nine-year-olds as they had for the highest-scoring 10 percent.

At the pace of recovery we are seeing today, too many students of all races and income levels will graduate in the coming years without the skills and knowledge needed for college and careers.

3. What we know at this point is incomplete. The situation could be significantly worse than the early data suggest.

The data and stories we have to date are enough to warrant immediate action, but there are serious holes in our understanding of how the pandemic has affected various groups of students, especially those who are typically most likely to fall through the cracks in the American education system.

We know little about students with complex needs, such as those with disabilities and English learners. We still know too little about the learning impacts in non-tested subjects, such as science, civics, and foreign languages. And while psychologists , educators , and the federal government are sounding alarms about a youth mental health crisis, systematic measures of student wellbeing remain hard to come by.

We must acknowledge that what we know at this point is incomplete, since the pandemic closures and following recovery have been so unprecedented in recent times. It’s possible that as we continue to dig into the evidence on the pandemic’s impacts, some student groups or subjects may have not been so adversely affected. Alternatively, the situation could be significantly worse than the early data suggest. Some students are already bouncing back quickly. But for others, the impact could grow worse over time.

In subjects like math, where learning is cumulative, pandemic-related gaps in students’ learning that emerged during the pandemic could affect their ability to grasp future material. In some states, test scores fell dramatically for high schoolers nearing graduation. Shifts in these students’ academic trajectories could affect their college plans—and the rest of their lives. And elevated rates of chronic absenteeism suggest some students who disconnected from school during the pandemic have struggled to reconnect since.

4. The harms students experienced can be traced to a rigid and inequitable system that put adults, not students, first.

• Despite often heroic efforts by caring adults, students and families were cut off from essential support, offered radically diminished learning opportunities, and left to their own devices to support learning.

• Too often, partisan politics, not student needs , drove decision-making.

• Students with complexities and differences too often faced systems immobilized by fear and a commitment to sameness rather than prioritization and problem-solving.

So, what can we do to address the situation we’re in?

Diverse needs demand diverse solutions that are informed by pandemic experiences

Freed from the routines of rigid systems, some parents, communities, and educators found new ways to tailor learning experiences around students’ needs. They discovered learning can happen any time and anywhere. They discovered enriching activities outside class and troves of untapped adult talent.

Some of these breakthroughs happened in public schools—like virtual IEP meetings that leveled power dynamics between administrators and parents advocating for their children’s special education services. Others happened in learning pods or other new environments where families and community groups devised new ways to meet students’ needs. These were exceptions to an otherwise miserable rule, and they can inform the work ahead.

We must act quickly but we must also act differently. Important next steps include:

• Districts and states should immediately use their federal dollars to address the emergent needs of the COVID-19 generation of students via proven interventions, such as well-designed tutoring, extended learning time, credit recovery, additional mental health support, college and career guidance, and mentoring. The challenges ahead are too daunting for schools to shoulder alone. Partnerships and funding for families and community-driven solutions will be critical.

• By the end of the 2022–2023 academic year, states and districts must commit to an honest accounting of rebuilding efforts by defining, adopting, and reporting on their progress toward 5- and 10-year goals for long-term student recovery. States should invest in rigorous studies that document, analyze, and improve their approaches.

• Education leaders and researchers must adopt a national research and development agenda for school reinvention over the next five years. This effort must be anchored in the reality that the needs of students are so varied, so profound, and so multifaceted that a one-size-fits-all approach to education can’t possibly meet them all. Across the country, community organizations who previously operated summer or afterschool programs stepped up to support students during the school day. As they focus on recovery, school system leaders should look to these helpers not as peripheral players in education, but as critical contributors who can provide teaching , tutoring, or joyful learning environments for students and often have trusting relationships with their families.

• Recovery and rebuilding should ensure the system is more resilient and prepared for future crises. That means more thoughtful integration of online learning and stronger partnerships with organizations that support learning outside school walls. Every school system in America should have a plan to keep students safe and learning even when they can’t physically come to school, be equipped to deliver high-quality, individualized pathways for students, and build on practices that show promise.

Our “State of the American Student” report is the first in a series of annual reports the Center on Reinventing Public Education intends to produce through fall of 2027. We hope every state and community will produce similar, annual accounts and begin to define ambitious goals for recovery. The implications of these deeply traumatic years will reverberate for decades unless we find a path not only to normalcy but also to restitution for this generation and future generations of American students.

The road to recovery can lead somewhere new. In five years, we hope to report that out of the ashes of the pandemic, American public education emerged transformed: more flexible and resilient, more individualized and equitable, and—most of all— more joyful.

Related Content

Joao Pedro Azevedo, Amer Hasan, Koen Geven, Diana Goldemberg, Syedah Aroob Iqbal

July 30, 2020

Matthew A. Kraft, Michael Goldstein

May 21, 2020

Dan Silver, Anna Saavedra, Morgan Polikoff

August 16, 2022

Early Childhood Education K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Brad Olsen, John McIntosh

April 3, 2024

Darcy Hutchins, Emily Markovich Morris, Laura Nora, Carolina Campos, Adelaida Gómez Vergara, Nancy G. Gordon, Esmeralda Macana, Karen Robertson

March 28, 2024

Jennifer B. Ayscue, Kfir Mordechay, David Mickey-Pabello

March 26, 2024

- Society ›

- Education & Science

Education worldwide - statistics & facts

Regional differences in higher education, the impact of covid-19, key insights.

Detailed statistics

Educational attainment worldwide 2020, by gender and level

Global adult literacy rate 2000-2022, by gender

Global youth literacy rate 2000-2022, by gender

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Current statistics on this topic.

Education Level & Skills

Educational Institutions & Market

Share of people with tertiary education in OECD countries 2022, by country

Illiteracy rates by world region 2022

Related topics

Education around the world.

- Education in Europe

- Education in China

- Education in Australia

Gender equality

- Gender equality worldwide

- Global status of women

- Gender equality in Europe

Higher education

- Higher education in South Korea

- Higher education in the UK

- Higher education in France

Recommended statistics

- Basic Statistic Educational attainment worldwide 2020, by gender and level

- Basic Statistic Share of OECD population with primary education as highest education level 2021

- Basic Statistic Share of population in OECD countries with secondary education 2022

- Basic Statistic Share of people with tertiary education in OECD countries 2022, by country

- Premium Statistic Education Index - comparison of selected countries 2021

- Premium Statistic Share of population not in education or employment globally2023, by gender and region

- Basic Statistic Pre-education participation rate worldwide 2022, by region

Educational attainment worldwide in 2020, by gender and level

Share of OECD population with primary education as highest education level 2021

Share of population in OECD countries with primary or lower secondary education as highest education level in 2021, by country

Share of population in OECD countries with secondary education 2022

Share of population in OECD countries with upper secondary education as highest education level in 2022

Share of people with tertiary education in OECD and affiliated countries in 2022, by country

Education Index - comparison of selected countries 2021

Education index including inequality* of selected countries in 2021 (in parts per 1,000)

Share of population not in education or employment globally2023, by gender and region

Share of population not in education, training, or employment worldwide in 2023, by gender and region

Pre-education participation rate worldwide 2022, by region

Participation rate in organized learning (one year before official primary entry age) worldwide in 2022, by region

Primary education

- Basic Statistic Number of pupils in primary education worldwide 2000-2020

- Basic Statistic Net enrollment rate in primary school worldwide 2000-2018

- Basic Statistic Lower secondary education net enrollment rate globally 2020, by country development

- Basic Statistic Primary school completion rate worldwide 2000-2020

Number of pupils in primary education worldwide 2000-2020

Number of pupils in primary education worldwide from 2000 to 2020 (in millions)

Net enrollment rate in primary school worldwide 2000-2018

Net enrollment rate in primary school worldwide from 2000 to 2018

Lower secondary education net enrollment rate globally 2020, by country development

Net enrollment rate in primary school worldwide in 2020, by country development status

Primary school completion rate worldwide 2000-2020

Primary school completion rate worldwide from 2000 to 2020

Secondary education

- Basic Statistic Number of pupils in secondary education worldwide 2000-2020

- Basic Statistic Net enrollment rate in secondary school worldwide 2000-2018

- Basic Statistic Secondary school net enrollment rate globally 2020, by level and country development

- Basic Statistic Lower secondary completion rate worldwide 2000-2019

- Premium Statistic Sex ratio in secondary education worldwide 2000-2020, by gender

Number of pupils in secondary education worldwide 2000-2020