Home Blog Education How to Prepare Your Scientific Presentation

How to Prepare Your Scientific Presentation

Since the dawn of time, humans were eager to find explanations for the world around them. At first, our scientific method was very simplistic and somewhat naive. We observed and reflected. But with the progressive evolution of research methods and thinking paradigms, we arrived into the modern era of enlightenment and science. So what represents the modern scientific method and how can you accurately share and present your research findings to others? These are the two fundamental questions we attempt to answer in this post.

What is the Scientific Method?

To better understand the concept, let’s start with this scientific method definition from the International Encyclopedia of Human Geography :

The scientific method is a way of conducting research, based on theory construction, the generation of testable hypotheses, their empirical testing, and the revision of theory if the hypothesis is rejected.

Essentially, a scientific method is a cumulative term, used to describe the process any scientist uses to objectively interpret the world (and specific phenomenon) around them.

The scientific method is the opposite of beliefs and cognitive biases — mostly irrational, often unconscious, interpretations of different occurrences that we lean on as a mental shortcut.

The scientific method in research, on the contrary, forces the thinker to holistically assess and test our approaches to interpreting data. So that they could gain consistent and non-arbitrary results.

The common scientific method examples are:

- Systematic observation

- Experimentation

- Inductive and deductive reasoning

- Formation and testing of hypotheses and theories

All of the above are used by both scientists and businesses to make better sense of the data and/or phenomenon at hand.

The Evolution of the Scientific Method

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , ancient thinkers such as Plato and Aristotle are believed to be the forefathers of the scientific method. They were among the first to try to justify and refine their thought process using the scientific method experiments and deductive reasoning.

Both developed specific systems for knowledge acquisition and processing. For example, the Platonic way of knowledge emphasized reasoning as the main method for learning but downplayed the importance of observation. The Aristotelian corpus of knowledge, on the contrary, said that we must carefully observe the natural world to discover its fundamental principles.

In medieval times, thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas, Roger Bacon, and Andreas Vesalius among many others worked on further clarifying how we can obtain proven knowledge through observation and induction.

The 16th–18th centuries are believed to have given the greatest advances in terms of scientific method application. We, humans, learned to better interpret the world around us from mechanical, biological, economic, political, and medical perspectives. Thinkers such as Galileo Galilei, Francis Bacon, and their followers also increasingly switched to a tradition of explaining everything through mathematics, geometry, and numbers.

Up till today, mathematical and mechanical explanations remain the core parts of the scientific method.

Why is the Scientific Method Important Today?

Because our ancestors didn’t have as much data as we do. We now live in the era of paramount data accessibility and connectivity, where over 2.5 quintillions of data are produced each day. This has tremendously accelerated knowledge creation.

But, at the same time, such overwhelming exposure to data made us more prone to external influences, biases, and false beliefs. These can jeopardize the objectivity of any research you are conducting.

Scientific findings need to remain objective, verifiable, accurate, and consistent. Diligent usage of scientific methods in modern business and science helps ensure proper data interpretation, results replication, and undisputable validity.

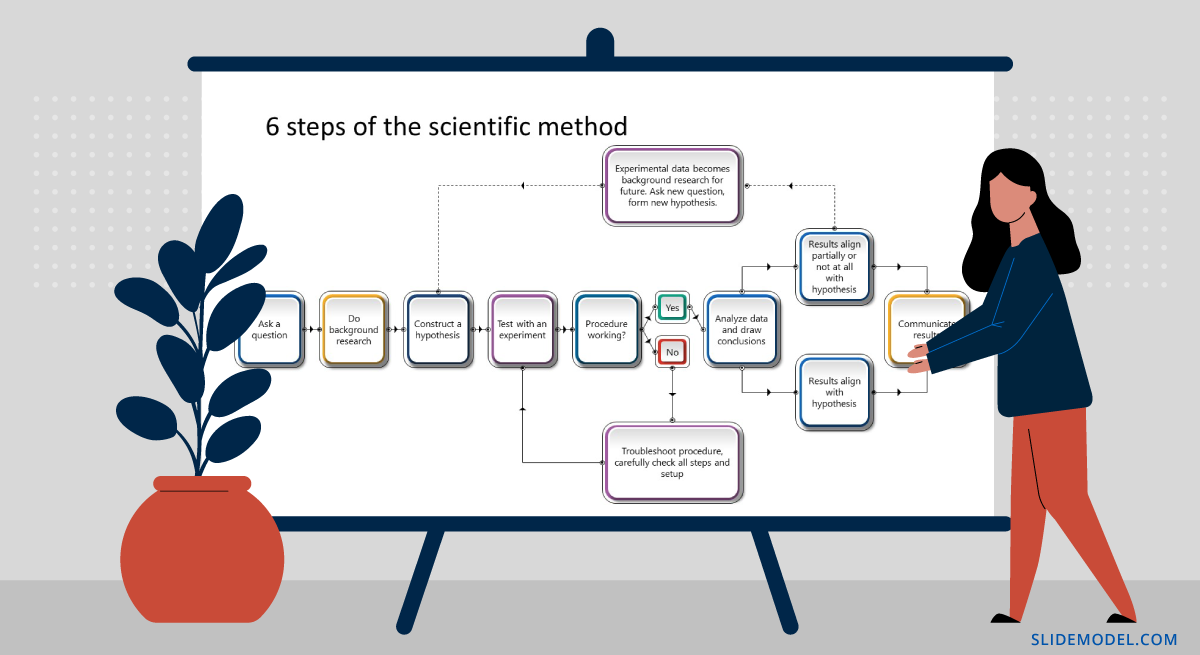

6 Steps of the Scientific Method

Over the course of history, the scientific method underwent many interactions. Yet, it still carries some of the integral steps our ancestors used to analyze the world such as observation and inductive reasoning. However, the modern scientific method steps differ a bit.

1. Make an Observation

An observation serves as a baseline for your research. There are two important characteristics for a good research observation:

- It must be objective, not subjective.

- It must be verifiable, meaning others can say it’s true or false with this.

For example, This apple is red (objective/verifiable observation). This apple is delicious (subjective, harder-to-verify observation).

2. Develop a Hypothesis

Observations tell us about the present or past. But the goal of science is to glean in the future. A scientific hypothesis is based on prior knowledge and produced through reasoning as an attempt to descriptive a future event.

Here are characteristics of a good scientific hypothesis:

- General and tentative idea

- Agrees with all available observations

- Testable and potentially falsifiable

Remember: If we state our hypothesis to indicate there is no effect, our hypothesis is a cause-and-effect relationship . A hypothesis, which asserts no effect, is called a null hypothesis.

3. Make a Prediction

A hypothesis is a mental “launchpad” for predicting the existence of other phenomena or quantitative results of new observations.

Going back to an earlier example here’s how to turn it into a hypothesis and a potential prediction for proving it. For example: If this apple is red, other apples of this type should be red too.

Your goal is then to decide which variables can help you prove or disprove your hypothesis and prepare to test these.

4. Perform an Experiment

Collect all the information around variables that will help you prove or disprove your prediction. According to the scientific method, a hypothesis has to be discarded or modified if its predictions are clearly and repeatedly incompatible with experimental results.

Yes, you may come up with an elegant theory. However, if your hypothetical predictions cannot be backed by experimental results, you cannot use them as a valid explanation of the phenomenon.

5. Analyze the Results of the Experiment

To come up with proof for your hypothesis, use different statistical analysis methods to interpret the meaning behind your data.

Remember to stay objective and emotionally unattached to your results. If 95 apples turned red, but 5 were yellow, does it disprove your hypothesis? Not entirely. It may mean that you didn’t account for all variables and must adapt the parameters of your experiment.

Here are some common data analysis techniques, used as a part of a scientific method:

- Statistical analysis

- Cause and effect analysis (see cause and effect analysis slides )

- Regression analysis

- Factor analysis

- Cluster analysis

- Time series analysis

- Diagnostic analysis

- Root cause analysis (see root cause analysis slides )

6. Draw a Conclusion

Every experiment has two possible outcomes:

- The results correspond to the prediction

- The results disprove the prediction

If that’s the latter, as a scientist you must discard the prediction then and most likely also rework the hypothesis based on it.

How to Give a Scientific Presentation to Showcase Your Methods

Whether you are doing a poster session, conference talk, or follow-up presentation on a recently published journal article, most of your peers need to know how you’ve arrived at the presented conclusions.

In other words, they will probe your scientific method for gaps to ensure that your results are fair and possible to replicate. So that they could incorporate your theories in their research too. Thus your scientific presentation must be sharp, on-point, and focus clearly on your research approaches.

Below we propose a quick framework for creating a compelling scientific presentation in PowerPoint (+ some helpful templates!).

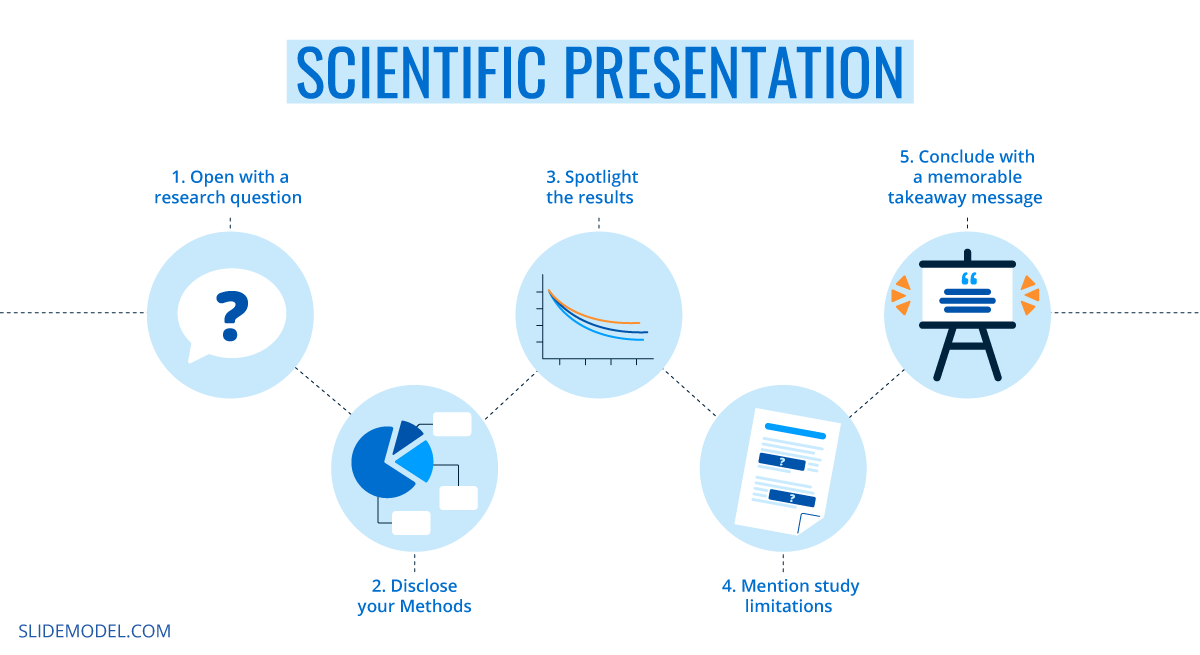

1. Open with a Research Question

Here’s how to start a scientific presentation with ease: share your research question. On the first slide, briefly recap how your thought process went. Briefly state what was the underlying aim of your research: Share your main hypothesis, mention if you could prove or disprove them.

It might be tempting to pack a lot of ideas into your first slide but don’t. Keep the opening of your presentation short to pique the audience’s initial interest and set the stage for the follow-up narrative.

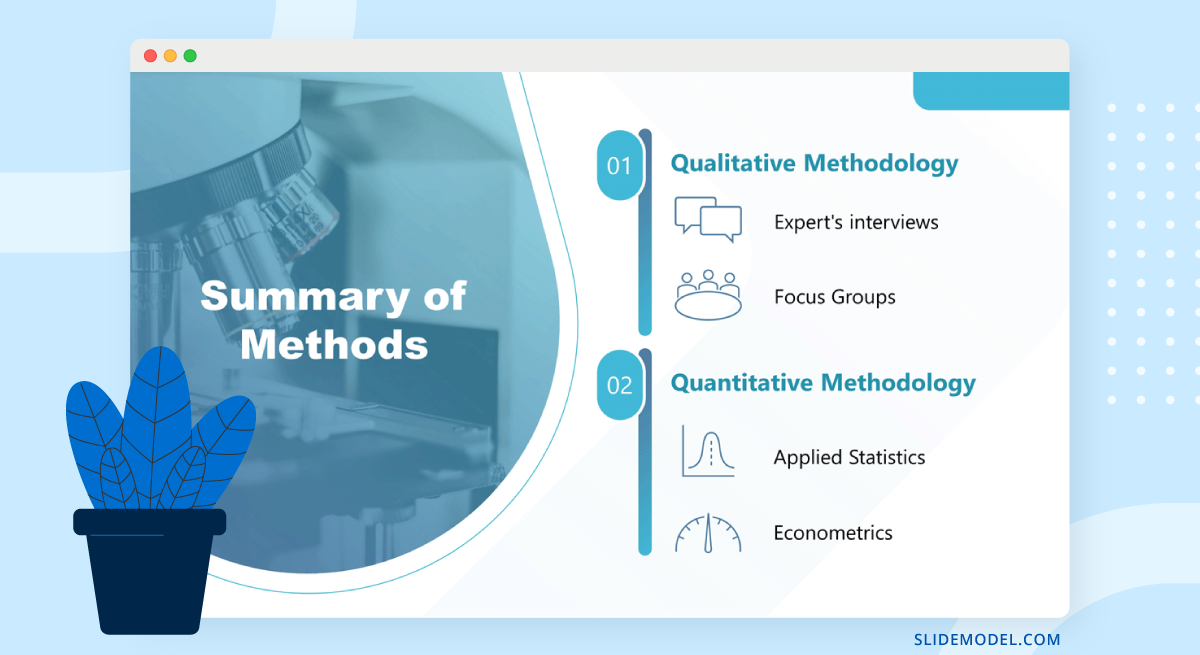

2. Disclose Your Methods

Whether you are doing a science poster presentation or conference talk, many audience members would be curious to understand how you arrived at your results. Deliver this information at the beginning of your presentation to avoid any ambiguities.

Here’s how to organize your science methods on a presentation:

- Do not use bullet points or full sentences. Use diagrams and structured images to list the methods

- Use visuals and iconography to use metaphors where possible.

- Organize your methods by groups e.g. quantifiable and non-quantifiable

Finally, when you work on visuals for your presentation — charts, graphs, illustrations, etc. — think from the perspective of a subject novice. Does the image really convey the key information around the subject? Does it help break down complex ideas?

3. Spotlight the Results

Obviously, the research results will be your biggest bragging right. However, don’t over-pack your presentation with a long-winded discussion of your findings and how revolutionary these may be for the community.

Rather than writing a wall of text, do this instead:

- Use graphs with large axis values/numbers to showcase the findings in great detail

- Prioritize formats that are known to everybody (e.g. odds ratios, Kaplan Meier curves, etc.)

- Do not include more than 5 lines of plain text per slide

Overall, when you feel that the results slide gets too cramped, it’s best to move the data to a new one.

Also, as you work on organizing data on your scientific presentation PowerPoint template , think if there are obvious limitations and gaps. If yes, make sure you acknowledge them during your speech.

4. Mention Study Limitations

The scientific method mandates objectivity. That’s why every researcher must clearly state what was excluded from their study. Remember: no piece of scientific research is truly universal and has certain boundaries. However, when you fail to personally state those, others might struggle to draw the line themselves and replicate your results. Then, if they fail to do so, they’d question the viability of your research.

5. Conclude with a Memorable Takeaway Message

Every experienced speaker will tell you that the audience best retains the information they hear first and last. Most people will attend more than one scientific presentation during the day.

So if you want the audience to better remember your talk, brainstorm a take-home message for the last slide of your presentation. Think of your last slide texts as an elevator pitch — a short, concluding message, summarizing your research.

To Conclude

Today we have no shortage of research and scientific methods for testing and proving our hypothesis. However, unlike our ancestors, most scientists experience deeper scrutiny when it comes to presenting and explaining their findings to others. That’s why it’s important to ensure that your scientific presentation clearly relays the aim, vector, and thought process behind your research.

Like this article? Please share

Education, Presentation Ideas, Presentation Skills, Presentation Tips Filed under Education

Related Articles

Filed under Google Slides Tutorials • March 22nd, 2024

How to Share a Google Slides Presentation

Optimize your presentation delivery as we explore how to share a Google Slides presentation. A must-read for traveling presenters.

Filed under Presentation Ideas • February 15th, 2024

How to Create a 5 Minutes Presentation

Master the art of short-format speeches like the 5 minutes presentation with this article. Insights on content structure, audience engagement and more.

Filed under Design • January 24th, 2024

How to Plan Your Presentation Using the 4W1H & 5W1H Framework

The 4W1H and 5W1H problem-solving frameworks can benefit presenters who look for a creative outlook in presentation structure design. Learn why here.

Leave a Reply

This website uses cookies to improve your user experience. By continuing to use the site, you are accepting our use of cookies. Read the ACS privacy policy.

- ACS Publications

10 Keys to an Engaging Scientific Presentation

- May 31, 2018

What makes an engaging scientific presentation? Georgia Tech Professor Will Ratcliff uses a method based on the style of nature documentary presenter David Attenborough. Ratcliff’s approach looks to capture an audience’s natural curiosity by using engaging visuals and simple storytelling techniques. Here are his 10 keys to an engaging scientific presentation: 1) Be an Entertainer First: […]

What makes an engaging scientific presentation? Georgia Tech Professor Will Ratcliff uses a method based on the style of nature documentary presenter David Attenborough. Ratcliff’s approach looks to capture an audience’s natural curiosity by using engaging visuals and simple storytelling techniques.

Here are his 10 keys to an engaging scientific presentation:

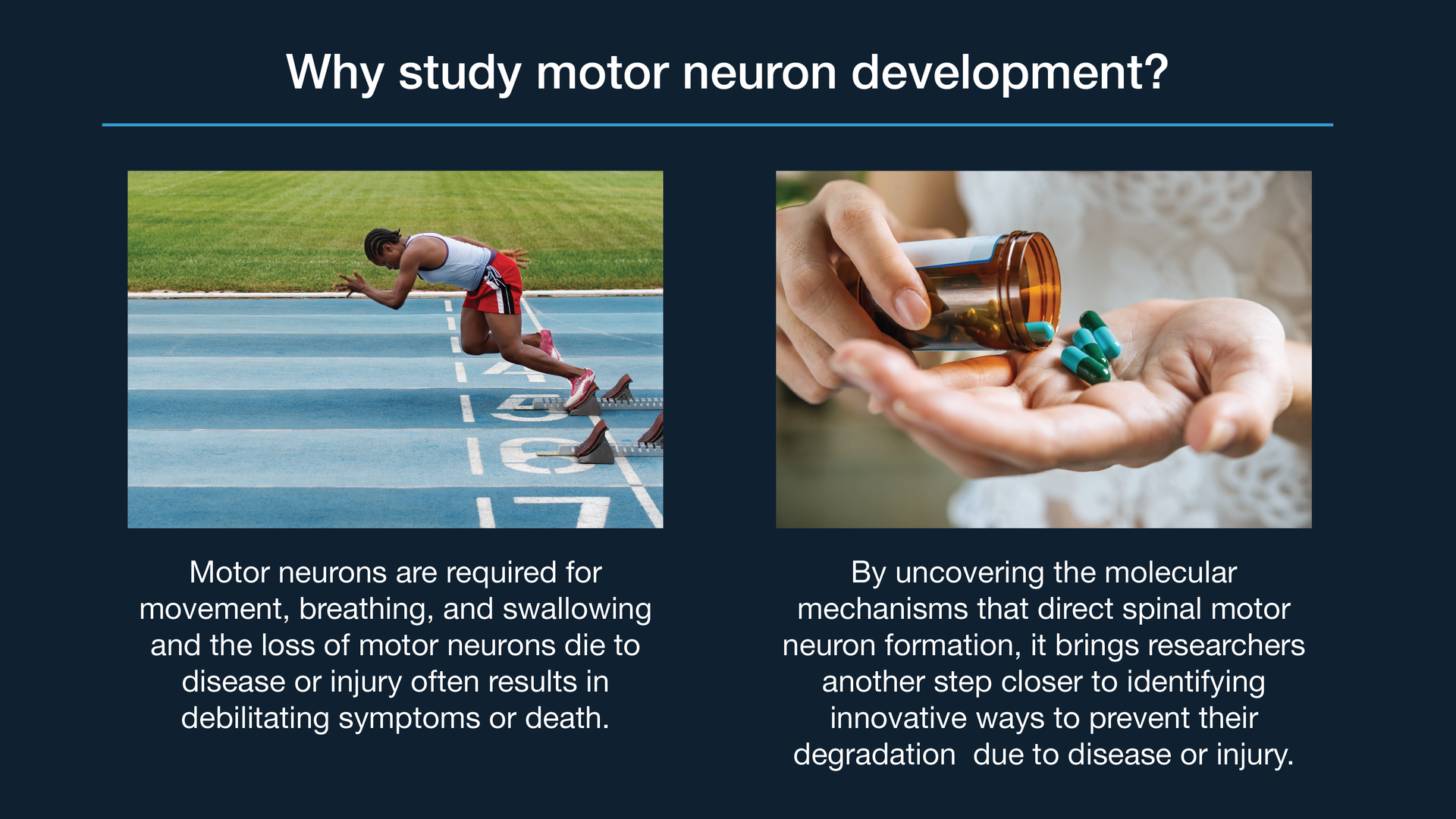

1) Be an Entertainer First : Before your science can wow your audience, they have to understand it. Before they can understand it, you must engage them with what you’re saying. Look at your presentation from your audience’s perspective and think about how they’ll relate to your material. Focus on presenting your science in a way that engages and entertains as it explains.

2) Be a Storyteller, Not a Lecturer : Don’t assume that your audience knows your field. Tell the story of your science: identify the big picture backdrop, your specific research questions, how you answer those questions, and how it affects the way we now think about the big picture.

3) Prioritize Clarity : If the audience doesn’t understand every word you use, they’ll stop paying attention, and you may never win them back. Your goal is to never lose their attention in the first place, so make an effort to be clear and have a simple narrative arc to your talk.

4) Mind Your Transitions: The easiest place to lose your audience’s focus is when you move from one slide to another. Practice the transitions in your talk to make sure the link between the ideas of one slide and the next remains clear.

5) Keep Complete Sentences Out of Your Slides: Keep the text in your slides to a minimum. Instead, use compelling visual to hold your audience’s attention while you speak.

6) Animations Are Your Friend: You can use animations to reveal new details on your slide as they become relevant to what you are saying. That way you get to control what your audience is seeing, minimizing distraction and putting laser pointers out of a job. Note: never use silly and unnecessary animations, like spinning or scrolling text, this will just annoy your audience.

7) Get Excited: If you’re not excited and energetic about your work, your audience won’t be either.

8) Look at the Audience: Don’t stare at the floor, the ceiling, or your slides while you’re presenting. Look directly at your audience, or if you’re nervous, toward the back of the lecture hall. This will help you connect with your audience.

9) Be Wary of Jokes: Scientific talks are serious by nature and you have more to lose than to gain. If a joke is poorly timed or if you misjudge an audience, you risk alienating them. Play it safe and find other ways to be entertaining unless you know your audience well.

10) Leave the Laser Pointer at Home: Laser pointers are distracting. If you feel you need one to guide your audience through a slide, that’s a sign your slide is too cluttered.

Want More Tips on Giving an Engaging Scientific Presentation? Check Out: 3 Elements of a Great Scientific Talk

Want the latest stories delivered to your inbox each month.

- Enterprise Custom Courses

- Build Your Own Courses

- Help Center

- Clinical Trial Recruitment

- Pharmaceutical Marketing

- Health Department Resources

- Patient Education

- Research Presentation

- Remote Monitoring

- Health Literacy & SciComm

- Student Education & Higher Ed

- Individual Learning

- Member Directory

- Community Chats on Slack

- SciComm Program

- The Story-Driven Method

- The Instructional Method

How to Create an Engaging Science Presentation: A Quick Guide

We’ve all been there – rushing to put slides together for an upcoming talk, filling them with bullet points and text that we want to remember to cover. We aren’t sure exactly what the audience will want to know or how much detail to include, so we default to putting ALL the details in that might be needed. But such efforts often result in presentations that are too long, too confusing, and difficult for both ourselves and our audiences to navigate.

Today I gave a workshop to public health graduate students about how to create more engaging science presentations and talks. I’ve summarized the main takeaways below. I hope this quick guide will be useful to you as you prepare for your next science talk or presentation!

The best science talks start with a process of simplifying – peeling back the layers of information and detail to get at the one core idea that you want to communicate. Over the course of your talk, you may present 2-3 key messages that relate to, demonstrate, provide examples of or underpin this idea. (Three is a nice round number of messages or takeaways that your audience will be able to remember!) But stick to one big idea. Trying to communicate too much in a presentation or talk will overwhelm your audience, and they may walk away without a good memory of any of the ideas you presented.

Once you’ve settled on your one big idea, you can develop a theme that will pervade every aspect of your talk. This theme might be a defining element of your big idea and something that can tie all of your data or talking points together. Your theme should inform the examples, anecdotes and analogies that you use to make the science concepts you present more accessible. It should also inform your slides’ very design – the colors, visuals, layout and content flow.

If you have trouble identifying your big idea and your theme, you can try using what scientist and science author Randy Olson calls the “Dobzhansky Template.” Fill in the blanks of this statement: “ Nothing in [your talk topic, research topic or big idea] makes sense, except in the light of [your theme!] .”

Here’s an example for you: “Nothing in the creation of engaging science talks makes sense except in the light of people’s need for personal connection .” With this statement, I’m identifying a key aspect, a unifying theme, for my talk (or blog post) on how to create engaging science talks. We all crave personal connection. Yes, even to the speakers of science talks we listen to! What does this mean in terms of what we want or expect from these speakers? It means we want storytelling . We want to hear their stories, know their background, hear about their struggles and triumphs! We want to be able to step into their shoes and see what they saw. We want to interact with them.

Tell a Story

Narratives engage more than facts. By telling a story , using suspense and characters to pull people through your presentation, you will capture and keep their attention for longer. People also remember information presented in a story format better than they do information presented as disparate facts or bullet points.

“Story is a pull strategy. If your story is good enough, people—of their own free will—come to the conclusion they can trust you and the message you bring.” – Annette Simmons

Storytelling is a powerful science communication tool. In storytelling, both the storyteller and the listener or reader contribute to the story’s meaning through their interpretations, feelings and emotions. Liz Neeley, former executive director of The Story Collider, once said: “Science communicators frequently fail to understand that a feeling is almost never conquered with a fact.”

Stories are exciting. They elicit emotions. They help foster a personal connection between the storyteller and the listener, and a connection between the listener and the topic, characters or ideas presented in the story.

But what IS a story? As humans, we excel at recognizing a story when we hear one, but defining a story’s key characteristics is more difficult than you might think. If you ask anyone to explain what makes for a good story, they likely will have a hard time explaining it.

In her fantastic book Wired for Story , Lisa Cron starts by explaining what a story is NOT.

It is not plot – that is just what happens in the story.

It is not characters , although characters are critical components of storytelling, even if they are not human or even alive. Cells and molecules could be the characters of your next science talk!

It is not suspense or conflict , although these elements get us closer to what defines a good story. But just because your talk builds suspense does not necessarily make it an engaging story. What if we don’t identify with your characters?

The truth is that the key defining element of story is internal change . Think of how every Aesop’s fable communicates a moral or lesson that the main character learned from some journey. As Lisa Cron writes, “A story is how what happens affects someone who is trying to achieve what turns out to be a difficult goal, and how he or she changes as a result.” The key here is the part about “how he or she changes.” A great story calls characters to a great adventure, but the adventure doesn’t leave them just as they were before. The adventure – like a scientific discovery that took years of experimentation (and failure) in the lab – leads to an internal change, in perspective or knowledge or behavior, as a result of conflicts overcome.

This is the secret of storytelling. A story asks characters to change and grow, and so the scientists in our stories must change and grow, discover new things about themselves and overcome challenges that force them to adopt new perspectives. So if you are giving a science talk about your own research, this might look like telling stories about your own struggles, growths and changes in perspective as you made your journey to discovery!

How can you bring a story of internal change to your next science presentation or talk?

What is one of the most common mistakes people make when creating slides to accompany a science talk? They use WAY too much text, and they use visuals as an afterthought. Worse yet, they use visuals that are copyrighted without attribution. They use stock imagery that reinforces stereotypes. They use visuals pasted from a Google search that don’t help the viewer understand or interpret what is said or written on the slides.

Visuals can be a powerful tool to advance audience learning or engagement during your science talks. You can use visuals to provide concrete examples of concepts you are talking about. You can use imagery that sparks thought or emotion. You can use visuals that reinforce your BIG idea or the theme of your talk, in a way that will make your talk more memorable for them. Yes, you might need to use a scientific figure, graph, chart or data visualization here and there if you are giving a more technical scientific talk, and that’s ok as long as you also talk the audience through this visual. Don’t assume they can listen to you talk about something different while also taking the time to interpret the message in this graphic or visualization – they can’t.

The same goes for text. You are demanding way too much brainpower of your audience to expect them to listen to you while also reading your slides. And if you are saying the same things as are written on your slides, they will grow bored. Simple visual aids used the right way, however, can delight your audience and help them better understand what you are saying.

Consider working with a professional artist or designer to create visuals for the slides of your next science talk! They excel at creating visuals that capture people’s attention, curiosity and emotions. And if you do this, your visuals will perfectly match what you are trying to communicate in words, boosting learning and understanding.

Foster Interaction

A good science talk or presentation gives the audience opportunities to interact with you! This could be through questions, activities, discussions or thought experiments. Let the audience explore your data or interpretations with you. They will be more engaged and likely trust you more as a result, because they felt heard .

Personalize!

Most great science speakers make themselves vulnerable in a way – they tell personal stories of struggles, growth and discovery. Personal stories are engaging. They also help the audience care about what the speaker has to say.

It can be scary to talk about yourself, especially for a scientist who has been trained to focus solely on the data. But the humans listening to your talk or presentation crave human connection. They will also grab hold of anything that helps them better relate to you. Give them that in the form of personal stories of obstacles overcome, of personal lessons learned, of work-life balance, of your fears and passions. Better yet, tell personal stories that reinforce your theme and show the power of your big idea!

Do you have other strategies for how you make your science talks and presentations more engaging? Let me know in the comments below!

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

About the author: paige jarreau.

Related Posts

Una actividad práctica para ayudarte a comunicar la ciencia de forma culturalmente relevante

The Power of SciComm in Combatting Mental Health Stigma

Make your scicomm more culturally relevant: a practice activity.

Communicating About Postpartum Depression

Science Communication and Genetic Counselling

Creating Analogies: Elevate Your Science with a Lifeology Course

This page has been archived and is no longer updated

Oral Presentation Structure

Finally, presentations normally include interaction in the form of questions and answers. This is a great opportunity to provide whatever additional information the audience desires. For fear of omitting something important, most speakers try to say too much in their presentations. A better approach is to be selective in the presentation itself and to allow enough time for questions and answers and, of course, to prepare well by anticipating the questions the audience might have.

As a consequence, and even more strongly than papers, presentations can usefully break the chronology typically used for reporting research. Instead of presenting everything that was done in the order in which it was done, a presentation should focus on getting a main message across in theorem-proof fashion — that is, by stating this message early and then presenting evidence to support it. Identifying this main message early in the preparation process is the key to being selective in your presentation. For example, when reporting on materials and methods, include only those details you think will help convince the audience of your main message — usually little, and sometimes nothing at all.

The opening

- The context as such is best replaced by an attention getter , which is a way to both get everyone's attention fast and link the topic with what the audience already knows (this link provides a more audience-specific form of context).

- The object of the document is here best called the preview because it outlines the body of the presentation. Still, the aim of this element is unchanged — namely, preparing the audience for the structure of the body.

- The opening of a presentation can best state the presentation's main message , just before the preview. The main message is the one sentence you want your audience to remember, if they remember only one. It is your main conclusion, perhaps stated in slightly less technical detail than at the end of your presentation.

In other words, include the following five items in your opening: attention getter , need , task , main message , and preview .

Even if you think of your presentation's body as a tree, you will still deliver the body as a sequence in time — unavoidably, one of your main points will come first, one will come second, and so on. Organize your main points and subpoints into a logical sequence, and reveal this sequence and its logic to your audience with transitions between points and between subpoints. As a rule, place your strongest arguments first and last, and place any weaker arguments between these stronger ones.

The closing

After supporting your main message with evidence in the body, wrap up your oral presentation in three steps: a review , a conclusion , and a close . First, review the main points in your body to help the audience remember them and to prepare the audience for your conclusion. Next, conclude by restating your main message (in more detail now that the audience has heard the body) and complementing it with any other interpretations of your findings. Finally, close the presentation by indicating elegantly and unambiguously to your audience that these are your last words.

Starting and ending forcefully

Revealing your presentation's structure.

To be able to give their full attention to content, audience members need structure — in other words, they need a map of some sort (a table of contents, an object of the document, a preview), and they need to know at any time where they are on that map. A written document includes many visual clues to its structure: section headings, blank lines or indentations indicating paragraphs, and so on. In contrast, an oral presentation has few visual clues. Therefore, even when it is well structured, attendees may easily get lost because they do not see this structure. As a speaker, make sure you reveal your presentation's structure to the audience, with a preview , transitions , and a review .

The preview provides the audience with a map. As in a paper, it usefully comes at the end of the opening (not too early, that is) and outlines the body, not the entire presentation. In other words, it needs to include neither the introduction (which has already been delivered) nor the conclusion (which is obvious). In a presentation with slides, it can usefully show the structure of the body on screen. A slide alone is not enough, however: You must also verbally explain the logic of the body. In addition, the preview should be limited to the main points of the presentation; subpoints can be previewed, if needed, at the beginning of each main point.

Transitions are crucial elements for revealing a presentation's structure, yet they are often underestimated. As a speaker, you obviously know when you are moving from one main point of a presentation to another — but for attendees, these shifts are never obvious. Often, attendees are so involved with a presentation's content that they have no mental attention left to guess at its structure. Tell them where you are in the course of a presentation, while linking the points. One way to do so is to wrap up one point then announce the next by creating a need for it: "So, this is the microstructure we observe consistently in the absence of annealing. But how does it change if we anneal the sample at 450°C for an hour or more? That's my next point. Here is . . . "

Similarly, a review of the body plays an important double role. First, while a good body helps attendees understand the evidence, a review helps them remember it. Second, by recapitulating all the evidence, the review effectively prepares attendees for the conclusion. Accordingly, make time for a review: Resist the temptation to try to say too much, so that you are forced to rush — and to sacrifice the review — at the end.

Ideally, your preview, transitions, and review are well integrated into the presentation. As a counterexample, a preview that says, "First, I am going to talk about . . . , then I will say a few words about . . . and finally . . . " is self-centered and mechanical: It does not tell a story. Instead, include your audience (perhaps with a collective we ) and show the logic of your structure in view of your main message.

This page appears in the following eBook

Topic rooms within Scientific Communication

Within this Subject (22)

- Communicating as a Scientist (3)

- Papers (4)

- Correspondence (5)

- Presentations (4)

- Conferences (3)

- Classrooms (3)

Other Topic Rooms

- Gene Inheritance and Transmission

- Gene Expression and Regulation

- Nucleic Acid Structure and Function

- Chromosomes and Cytogenetics

- Evolutionary Genetics

- Population and Quantitative Genetics

- Genes and Disease

- Genetics and Society

- Cell Origins and Metabolism

- Proteins and Gene Expression

- Subcellular Compartments

- Cell Communication

- Cell Cycle and Cell Division

© 2014 Nature Education

- Press Room |

- Terms of Use |

- Privacy Notice |

Visual Browse

Reference management. Clean and simple.

5 tips for giving a good scientific presentation

What is a scientific presentation?

What is the objective of a scientific presentation, why is giving scientific presentations necessary, how to give a scientific presentation, tip 1: prepare during the days leading up to your talk, tip 2: deal with presentation nerves by practicing simple exercises, tip 3: deliver your talk with intention, tip 4: be adaptable and willing to adjust your presentation, tip 5: conclude your talk and manage questions confidently, concluding thoughts, other sources to help you give a good scientific presentation, frequently asked questions about giving scientific presentations, related articles.

You have made the slides for your scientific presentation. Now, you need to prepare to deliver your talk. But, giving an oral scientific presentation can be nerve-wracking. How do you ensure that you deliver your talk well, and leave a good impression on the audience?

Mastering the skill of giving a good scientific presentation will stand you in good stead for the rest of your career, as it may lead to new collaborations or even new employment opportunities.

In this guide, you’ll find everything you need to know to give a good oral scientific presentation, including

- Why giving scientific presentations is important for your career;

- How to prepare before giving a scientific presentation;

- How to keep the audience engaged and deliver your talk with confidence.

The following tips are a product of our research into the literature on giving scientific presentations as well as our own experiences as scientists in giving and attending talks. We advise on how to make a scientific presentation in another post.

A scientific presentation is a talk or poster where you describe the findings of your research to others. An oral presentation usually involves presenting slides to an audience. You may give an oral scientific presentation at a conference, give an invited seminar at another institution, or give a talk as part of an interview. A PhD thesis defense is one type of scientific presentation.

➡️ Read about how to prepare an excellent thesis defense

The objective of a scientific presentation is to communicate the science such that the audience:

- Learns something new;

- Leaves with a clear understanding of the key message of your research;

- Has confidence in you and your work;

- Remembers you afterward for the right reasons.

As a scientist, one of your responsibilities is disseminating your scientific knowledge by giving presentations. Communicating your research to others is an altruistic act, as it is an opportunity to teach others about your research findings, and the knowledge you have gained while researching your topic.

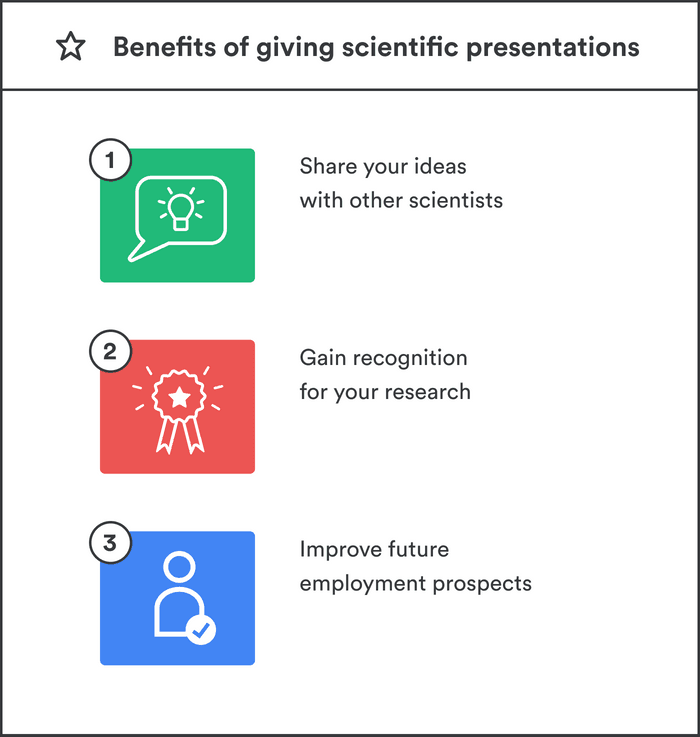

Giving scientific presentations confers many career benefits , such as:

- Having the opportunity to share your ideas and to have insightful conversations with other scientists. For example, a thoughtful question may create a new direction for your research.

- Gaining recognition for your work and generating excitement for your research program can help you to forge new collaborations and to obtain more citations of your papers. It's your chance to impress some of the biggest names in your field, build your reputation as a scientist, and get more people interested in your work.

- Improving your future employment prospects by getting presentation experience in high-stakes settings and by having talks listed on your academic CV.

➡️ Learn how to write an academic CV

You might have just 10 minutes for your talk. But those 10 minutes are your golden ticket. To make them shine, you'll need to put in some homework. You need to think about the story you want to tell , create engaging slides , and practice how you're going to deliver it.

Why all this effort? Because the rewards are potentially huge. Imagine speaking to the top names in your field, boosting your visibility, and getting more eyes on your work. It's more than just a talk; it's your chance to showcase who you are and what you do.

Here we share 5 tips for giving effective scientific presentations.

- Prepare adequately for your talk on the days leading up to it

- Deal with presentation nerves

- Deliver your talk with intention

- Be adaptable

- Conclude your talk with confidence

You should prepare for your talk with the seriousness it deserves and recognize the potential it holds for your career advancement. Here are our suggestions:

- Rehearse your talk multiple times to ensure smooth flow. Know the order of your slides and key transitions without memorizing every word. Practice your speech as though you are discussing with friendly and attentive listeners.

- Record your speech and listen back to yourself giving your talk while doing household chores or while going for a walk. This will help you remember the important points of your talk and feel more comfortable with the flow of it on the day.

- Anticipate potential questions that may arise during your talk, write down your responses to those questions, and practice them aloud.

- Back up your presentation in cloud storage and on a USB key. Bring your laptop with you on the day of your talk, if needed.

- Know the time and location of your talk. Familiarize yourself with the room, if you can. Introduce yourself to the moderator before the session begins.

- Giving a talk is a performance, so preparing yourself physically and mentally is essential. Prioritize good sleep and hydration, and eat healthy, nourishing food on the day of your talk. Plan your attire to be both professional and comfortable.

It’s natural to feel nervous before your talk, but you want to harness that energy to present your work with confidence. Here are some ways to manage your stress levels:

- Remember that your audience want to listen to you and learn from you. Believe that your audience will be kind, friendly, and interested, rather than bored and skeptical.

- Breathing slow and deep before your talk calms the mind and nervous system. Psychologist Amy Cuddy recommends practicing open, confident postures while sitting and standing to help you get into a positive frame of mind.

- Fight off impostor syndrome with positive affirmations. You’ve got this! Remember that you know more about your research than anyone else in the room and you are giving your talk to teach others about it.

Giving your talk with confidence is crucial for your credibility as a scientist. Focusing on your delivery helps ensure that your audience remembers and believes what you say. Here are some techniques to try:

- Before beginning, remember your professional goals and the benefits of giving your presentation. Start with a smile and exhale deeply.

- Memorize a simple opening. After the moderator introduces you, pause and take a breath. Welcome the audience, thank them for coming, and introduce yourself. You don’t need to read the title of your talk. But briefly, say something like, “today I’m going to talk to you about why [topic] is important and [what I hope you will learn from this talk]” in 1-2 sentences. Preparing your opening will settle your nerves and prevent you from starting your talk on a tangential topic, ensuring you stay on time.

- Project confidence outwardly, even if you feel nervous. Stand up tall with your shoulders back and make eye contact with individuals in the audience. Move your focus around the room, so everyone in the audience feels included.

- Maintain open body language and face the audience as much as possible, not your slides.

- Project your voice as much as you can so that people at the back of the room can hear you. Enunciate your words, avoid mumbling, and don’t trail off awkwardly.

- Varying your vocal delivery and intonation will make your talk more interesting and help the audience pay attention, particularly when you want to emphasize key points or transitions.

- Pausing for dramatic effect at crucial moments can help you relax and remember your message, as well as being an effective engagement device.

- A laser pointer can be off-putting for the audience if you are prone to having a shaky hand when nervous. Use a laser pointer only to emphasize information on the slide while providing an explanation. If you design your slides thoughtfully , you won’t need to use a laser pointer.

Not all parts of your talk may go according to plan. Here are some ways to adapt to hitches during your talk:

- Handle talk disruptions gracefully. If you make a mistake, or a technical issue occurs during your talk, remember that it’s okay to skip something and move on without apologizing.

- If you forget to mention something but the audience hasn’t noticed, don’t point it out! They don’t need to know.

- As you give your talk, be time-conscious, and watch the moderator for signals that the time is about to expire. If you realize you won’t have time to discuss all your slides, skip the less important ones. Adjust your presentation on the fly to finish on time, prioritizing content as needed.

- If you run out of time completely, just stop. You don’t have to give a conclusion, but you do need to stop on time! Practicing your talk should prevent this situation.

The ending of your talk is important for emphasizing your key message and ensuring the audience leave with a positive impression of you and your work. Here are some pointers.

- Conclude your talk with a memorized closing statement that summarizes the key take-home message of your research. After making your closing statement, end your talk with a simple “Thank you”. Then pause and wait for the applause. You don’t need to ask if the audience has questions because the moderator will call for questions on your behalf.

- When you receive a question, pause, then repeat the question. This ensures the whole audience understands the question and gives you time to calmly consider your answer.

- In a talk on attaining confidence in your scientific presentations, Michael Alley suggests that if you don’t know the answer to the question, then emphasize what you do know. Say something like, “Although I can’t fully answer your question, I can say [this about the topic].”

- Approach the Q&A with interest rather than anxiety by reframing it as an opportunity to further share your knowledge. Being curious, instead of feeling fearful, can help you shine during what might be the most stressful part of your presentation.

Communicating your research effectively is a key skill for early career scientists to learn. Taking ample time to prepare and practice your presentation is an investment in your scientific development.

But here's the good part: all that effort pays off. Think of your talk as not just a presentation, but as a way to show off what you and your research are all about. Giving a compelling scientific presentation will raise your professional profile as a scientist, lead to more citations of your work, and may even help you obtain a future academic job.

But most importantly of all, giving talks contributes to science, and sharing your knowledge is an act of generosity to the scientific community.

➡️ Questions to ask yourself before you make your talk

➡️ How to give a great scientific talk

1) Have a positive mindset. To help with nerves, breathe deeply and keep in mind that you are an authority on your topic. 2) Be prepared. Have a short list of points for each slide and know the key transition points of your talk. Practice your talk to ensure it flows smoothly. 3) Be well-rested before your talk and eat a light meal on the day of your presentation. A talk is a performance. 4) Project your voice and vary your vocal intonation and pitch to retain the interest of the audience. Take pauses at key moments, for emphasis. 5) Anticipate questions that audience members could ask, and prepare answers for them.

The goal of a scientific presentation is that the audience remembers the key outcomes of your research and that they leave with a good impression of you and your science.

Take a moment to exhale deeply and collect your thoughts after the moderator has introduced you. Don’t read your talk's title. Instead, introduce yourself, thank the audience for attending, and provide a warm welcome. Then say something along the lines of, "Today I'm going to talk to you about why [topic] is important and [what I hope you will learn from this presentation].” A rehearsed opening will ensure that you start your talk on a confident note.

Prepare a memorable closing statement that emphasizes the key message of your talk. Then end with a simple “Thank you”.

Preparation is key. Practice many times to familiarize yourself with the content of your presentation. Before giving your talk, breathe slowly and deeply, and remind yourself that you are the expert on your topic. When giving your talk, stand up tall and use open body language. Remember to project your voice, and make eye contact with members of the audience.

- Google Slides Presentation Design

- Pitch Deck Design

- Powerpoint Redesign

- Other Design Services

- Design Tips

- Guide & How to's

How to prepare a scientific presentation

Putting together a scientific presentation might be a pretty challenging undertaking. However, with careful preparation and planning, it can turn into a rewarding experience.

In this article, we’ll discuss the purpose, presentation methods, and structure of an excellent scientific ppt, as well as share essential tips on how to introduce a scientific presentation, so dive in!

What’s a scientific presentation

A scientific presentation is a formal way to share an observation, propose a hypothesis, show and explain the findings of a study, or summarize what has been discovered or is still to be studied on the subject.

Professional scientific presentations aid in disseminating research and raise peers’ awareness of novel approaches, findings, or issues. They make conferences memorable for both the audience and the presenter.

Presentation methods

The three major presentation methods that are frequently used at large conferences include platform (oral), poster, and lecture presentations. Although appearing seemingly different at times, they all have the same requirements and difficulties for successful execution, and their main prerequisite is you, the presenter.

An effective presenter should have led the research, taken part in the analysis, and written the abstract and manuscript, which means the presenter should be fully knowledgeable about the topic at hand.

Scientific presentation structure

For the majority of scientific presentations, it is advisable to follow the traditional structure:

Title → Introduction/Background → Methods → Results → Discussion → Conclusion → Acknowledgements.

1. Introduction

The main elements that make up the introduction include the background of the study, the research problem, the significance of the research, the research objectives, research questions, and/or hypotheses.

The background is the premise upon which the study’s problem is built. It usually consists of one or two sentences.

After the background usually comes the research problem, which is made up of one or two sentences with clear statements. These can be anything from conflicting findings to a knowledge gap your scientific presentation PowerPoint addresses.

The justification part should briefly outline how the findings will contribute to the problem’s solution. It can also discuss the possible implications of the study in not more than two sentences.

Next comes the purpose of the study, which has to outline your goals and relate to the study’s title.

You may wrap up the introduction by listing the objectives of your study, research questions, or hypotheses. The study’s objectives describe the specific steps that must be taken to accomplish the goal. Please note that the objective can be turned into a research question and a research question, in turn, into a hypothesis.

2. Methodology

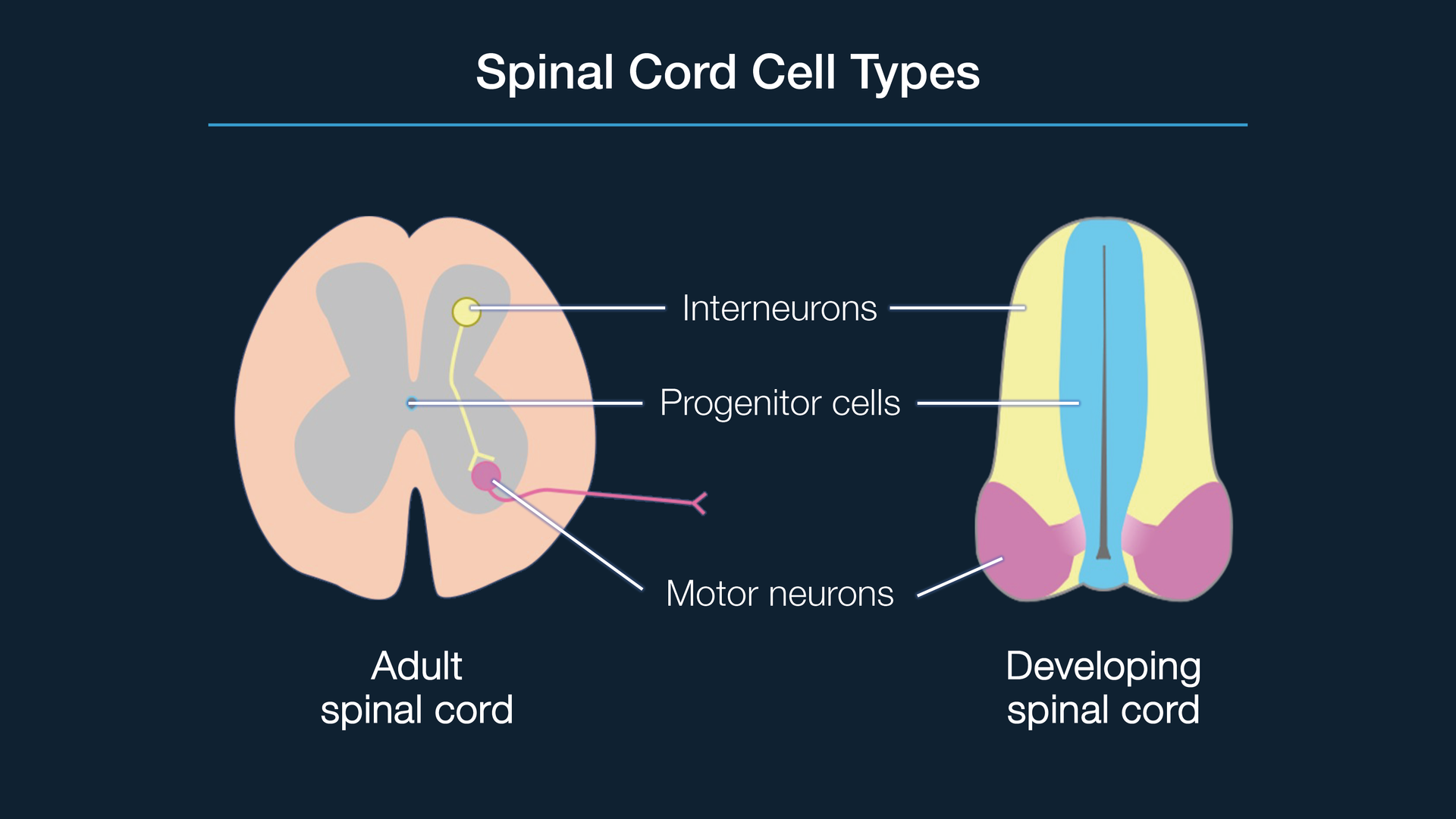

This section of your presentation should include a relevant study area map. It is recommended that you adequately describe the research design and use diagrams like flowcharts whenever possible.

Additionally, explain the procedures for obtaining the data for each objective, research question, and hypothesis. Finally, state the statistical analysis procedures used.

3. Results and discussion

An oral presentation will always include both the results and the discussion. However, the slides will only contain the results.

You can use tables and figures together, but they shouldn’t be applied to the same data set.

The results of your scientific PowerPoint presentation have to be organized in the same order as the objectives, research questions, and hypotheses. Still, describing and discussing the obtained results should be done off-head.

During your presentation, explain the findings in the tables and figures, pointing out any patterns. Also, discuss the results by assigning reasons to patterns, comparing the results with earlier research, and offering interpretations and implications for your findings.

4. Conclusion

Your presentation’s final section should offer closing remarks on the study’s key findings, not restate the results. Discuss the findings and their implications and make recommendations for additional research briefly and concisely.

If you include in-text references in your slides, always provide external references on a separate slide.

Prepare your title slide before beginning the research’s introduction section. Your name, your institution or department, the title of the presentation, and its date should all be included on the title slide.

Last but not least, your second slide should include the scientific presentation outline.

3 things to pay attention to when creating a scientific presentation

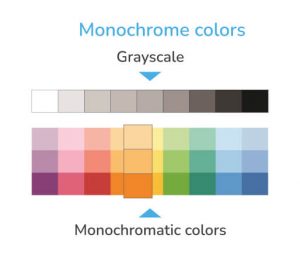

Color is a powerful tool for setting a pattern. It can make it easier for the reader or the audience to follow you and comprehend the connection between the subjects you are presenting.

According to our design experts, you have to create a natural flow of information and emphasize information that the reader has to see first (e.g., title or main image). Secondary data has to be less prominent, not to take priority. This all can be achieved through colors. Striking colors will quickly grab the audience’s attention. Meanwhile, a grayscale will be more discreet, making it ideal for secondary information.

Pro tip: Select one or two primary colors for your presentation, then use them repeatedly on the slides.

2. Typography

Font selection is crucial for the overall success of your presentation. Therefore, make sure your text is simple to see and read even if the person is sitting a considerable distance from the screen. Separate paragraphs and headings and stick with three different fonts at most (e.g., Helvetica, Gotham).

Remember that your audience will be looking at the slides while you are speaking, so avoid putting too much text on them.

Pro tip: Use a different font for your headline but ensure it doesn’t create the “comic sans” effect.

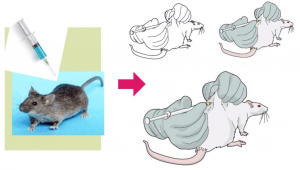

Visual aids such as charts, graphs, and images are indispensable for effectively conveying information and grabbing the audience’s attention, but you must choose them carefully.

Make sure to move from this to this:

Pro tip: If there’s a diagram, chart, or other visual that you don’t plan to walk your audience through, cut it.

Here’s a good scientific presentation example to follow:

Now that you know how to make a scientific presentation and what to pay attention to when creating one, let’s move on to the scientific presentation tips from the best designers of our professional presentation services .

Top 10 tips on how to present a scientific paper

Tip #1: Know your audience

View the presentation as a dialogue with the audience rather than a monologue, and always consider the interests and expertise of your audience. This will help you tailor your scientific presentation to their level of knowledge and interests.

Tip #2: Make use of PowerPoint

PowerPoint is an excellent tool for presenting scientific research if appropriately used. Generally, this involves inserting a lot of relevant visuals and minimum words with a font size of 24 points and above.

Tip #3: Tell your audience about your research rather than its background

Focus on discussing the research that you are directly contributing to. The background information should only include the bare minimum. People don’t attend conferences to hear a review of previous work. They do so to learn about new and intriguing research, so use the allotted time to your advantage.

Tip #4: Practice and rehearse

Always practice your presentation of science thoroughly before giving it to anyone. By doing so, you’ll gain a better understanding of the material and make sure your presentation flows smoothly.

Tip #5: Keep to the time limit

A basic rule of thumb is to keep your presentation to 80% of the allotted time. If you are given 55 minutes to deliver your presentation, prepare 45 minutes worth of information: 15 minutes for introduction, 25 for the main aspects of your presentation, 5 to summarize and conclude, and leave the last ten for a Q&A session.

A well-done abstract, a set of carefully chosen viewgraphs, a brief “cheat sheet,” and an outline (perhaps placed in the corner of each viewgraph) should all help you stay on track throughout your presentation.

Tip #6: Don’t read from the slides

Reading from slides is commonplace in various fields, but do you really find it interesting to hear someone read their conference presentation? If reading is an absolute must, then our experts advise you to do it in such a way that no one in the audience notices it. Writing your text in a conversational tone and reading with emotion, conviction, and variations in tone is a great trick to achieve that.

Tip #7: Summarize the key points

Reiterate your main message and briefly touch on your main points in your conclusion. By doing so, you can ensure that your audience will remember the most crucial details of your presentation.

Tip #8: Use effective communication techniques

When delivering your presentation, use appropriate body language and effective communication techniques. These include maintaining eye contact with the audience, speaking clearly and at a reasonable volume, and conveying enthusiasm about your work. Remember, genuine enthusiasm accounts for 90% of a speaker’s success.

Tip #9: Engage the audience

Always ask questions and use polls or other interactive tools to interact with your audience and encourage discussion.

Tip #10: Dress for success

When preparing to give a scientific presentation, dress up professionally. This will help convey two crucial messages: you respect your audience and are willing to conform.

Wrapping up

Following the above science presentation structure and tips, you can create clear, informative, and engaging slides that effectively communicate your message to the audience. However, if you’re still wondering how to start a scientific presentation or need a PowerPoint makeover , don’t hesitate to contact our dedicated design experts!

At SlidePeak, we know that building a visually captivating presentation may be a real challenge for researchers and scientists. That’s why we’ve developed several services, including presentation redesign and creation from scratch by qualified scientific, technical, and medical designers who can make your work stand out both in science and creativity.

With over a decade of experience in presentation design, SlidePeak is trusted by thousands of researchers and scientists worldwide. So, submit your scientific presentation order today, and let dedicated experts turn your ideas into professional slides that will help you make an impact!

#ezw_tco-2 .ez-toc-widget-container ul.ez-toc-list li.active::before { background-color: #ededed; } Table of contents

- Presenting techniques

- 50 tips on how to improve PowerPoint presentations in 2022-2023 [Updated]

- Keynote VS PowerPoint

- Types of presentations

- Present financial information visually in PowerPoint to drive results

Crafting an engaging presentation script

- Business Slides

Franchise presentation: what it is and how to create an effective one

Annual report design templates and tips: how to tell a great story with financial data in 2023

Introduction

Presentation methods, delivering a presentation, study methods, discussion: transform, acknowledgements, how to prepare and deliver a scientific presentation : teaching course presentation at the 21st european stroke conference, lisboa, may 2012.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Andrei V. Alexandrov , Michael G. Hennerici; How to Prepare and Deliver a Scientific Presentation : Teaching Course Presentation at the 21st European Stroke Conference, Lisboa, May 2012 . Cerebrovasc Dis 1 April 2013; 35 (3): 202–208. https://doi.org/10.1159/000346077

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Background: A scientific presentation is a professional way to share your observation, introduce a hypothesis, demonstrate and interpret the results of a study, or summarize what is learned or to be studied on the subject. Presentation Methods: Commonly, presentations at major conferences include podium (oral, platform), poster or lecture, and if selected one should be prepared to PRESENT: P lan from the start (place integral parts of the presentation in logical sequence); R educe the amount of text and visual aids to the bare minimum; E lucidate (clarify) methods; S ummarize results and key messages; E ffectively deliver; N ote all shortcomings, and T ransform your own and the current thinking of others. We provide tips on how to achieve this. Presentation Results: After disclosing conflicts, if applicable, start with a brief summary of what is known and why it is required to investigate the subject. State the research question or the purpose of the lecture. For original presentations follow a structure: Introduction, Methods, Results, Conclusions. Invest a sufficient amount of time or poster space in describing the study methods. Clearly organize and deliver the results or synopsis of relevant studies. Include absolute numbers and simple statistics before showing advanced analyses. Remember to present one point at a time. Stay focused. Discuss study limitations. In a lecture or a podium talk or when standing by your poster, always think clearly, have a logical plan, gain audience attention, make them interested in your subject, excite their own thinking about the problem, listen to questions and carefully weigh the evidence that would justify the punch-line. Conclusions: Rank scientific evidence in your presentation appropriately. What may seem obvious may turn erroneous or more complex. Rehearse your presentation before you deliver it at a conference. Challenge yourself to dry runs with your most critically thinking colleagues. When the time comes, ace it with a clear mind, precise execution and fund of knowledge.

Over time communication standards between -scientists have evolved along with improved scientific method, increasing scrutiny of analyses and upholding to the highest level of evidence anything we call research. Scientific presentation is a professional way of sharing your observation, introducing a hypothesis, demonstrating and interpreting the results of a study, or -summarizing what has been learned or is to be studied on the subject. Professional presentations help disseminate research, make peers aware of novel approaches, findings or problems. These presentations make conferences memorable for both presenters and the audience. Anyone can recall the most exciting and most boring, the most clear and most convoluted, the most ‘-seriously?!' and the most ‘wow!!' presentations. Most presentations, however, fall in the in-between level of ‘so what?', ‘I did not quite get it …', or ‘maybe'. This means that all the work the authors have put in did not result in a paradigm shift, -advancement, or even ‘well, this is good to know' kind of an impact. We struggle to shape up our young presenters to make their science clear and visible, their presence known and their own networks grow.

Having initially struggled in preparing and delivering presentations ourselves, and having seen the many baby steps of our trainees now accomplished or shy of a track record, we have put together these suggestions on how to start, organize and accomplish what at first sight looks like a daunting task: presenting in front of people, many of whom may have expertise way beyond your own or who are scrutinizing every bit of data and ready to shred any evidence you might have to pieces. Unfortunately, there is no other way to advance science and become recognized than to survive this campaign from conception of a project to publication. This campaign has its own (often interim and hopefully not singular) culmination in a scientific presentation. This presentation also comes with question and answer sessions and importantly, with you and the audience possibly coming out of it with new messages, new thinking and even energy for breakthroughs, no matter how small or large the leap would be. So let's explore how to prepare and deliver a scientific presentation.

Currently, the common types of presentations at major conferences include podium (oral, platform), poster or lecture. Although seemingly different and at times some being more desirable over others, they all share the same prerequisites and challenges for successful execution. We will examine common threads and identify unique aspects of each type of these presentations. However, the first prerequisite for any scientific presentation (successful or not) is you, the presenter.

An effective presenter should have led the study, participated in the analysis and drafting of the abstract and manuscript, i.e. the presenter should know the subject of his or her talk inside out. One should therefore be prepared to PRESENT:

P lan from the start (place integral parts of the presentation in logical sequence);

R educe the amount of text and visual aids to the bare minimum;

E lucidate (clarify) methods;

S ummarize results and key messages;

E ffectively deliver;

N ote all shortcomings, and

T ransform your own and the current thinking of others.

So, as the scuba-diving instructors say: plan the dive, and dive the plan. The most important parts of scientific presentations should follow the logic of delivering the key messages. For the original presentations (platforms or posters), it is easy to simply follow the accepted abstracts, most often structured following the IMRaD principle: Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion (Conclusions).

Lecture format, content and logical flow of information often depend on the topic choice, which should be appropriate to the level of audience [ 1 ], time allotment and the target audience. Most competitive conferences offer short times even for invited lecturers as experts are expected to demonstrate cutting edge science, which assumes that the audience is already knowledgeable and the expert is capable of delivering information that sparks new thinking. The suggestion here to both novice and experienced speakers is to quickly summarize why the subject of presentation is important (catch audience attention [ 2,3 ]), where we are now (show the landscape of completed studies that established the common knowledge or conundrums, equipoise, etc.) and to move then to the latest advancements (this may include just-in publications, ongoing or planned future research or the most provocative take on the evidence out there).

Turning back to original presentations, advice is available on how to write abstracts following the IMRaD principle [ 4 ] and how to draft subsequent manuscripts [ 5 ]. We cannot stress enough the need to quickly follow-up the abstract submission with drafting the full manuscript. If the authors complete a manuscript before the presentation at a conference, the presenter will have a luxury of material to work with to compile either a set of slides for the podium or text and illustrations for the poster. If a manuscript was drafted and reviewed by coauthors, the challenge for a presenter is going to be a good one: trim down most sentences as both slides and posters benefit from short statements (not even full sentences) and large font sizes so that text can be easily read from a distance. Put yourself into the audience: your slides should be readable from the last row of a large room or a huge ballroom and your poster should be still readable from at least 2 m. The latter will allow better poster viewing by several people during guided poster tours or when a small group gathers spontaneously to view it.

This logically brings us to the second step: use bare minimum of any type of information to deliver your -presentation. Minimum text, minimum lines, minimum images, graphs, i.e. provide only the essential information as the audience attention span is short. Brevity, however, should not compromise quality: you should always stride to have the highest quality visual aids since these leave an impression on the audience [ 6 ] and good quality graphics are attributes of effective presentations [ 3 ].

At the same time, we cannot overemphasize the need to stick to time limits set for a specific presentation. Presenters should test their presentation in ‘real life' at home to their friends or at work in front of colleagues and ask for criticism. It is better to get criticism from members of the department (including your boss) than in a huge auditorium. Use a simple rule: an average talking time is 1 min per slide in oral presentations. You can then see how little you really can allocate to each slide if you load your talk with the most complicated visual presentation of data.

Let's go to the specifics. The ‘Introduction' slide usually includes a very brief description of background and should explicitly state the research question. Call it ‘Introduction and Study Purpose'. Adding a separate slide for study aims lengthens the talk. Fewer slides also reduce the chance of making an error when advancing them on the podium that can send presenters into further time deficit and stress, a commonplace even with those who know how to right-click.

Methods should have bullet points, not necessarily full sentences since you will be speaking over slides projecting or in front of the poster to connect brief statements showing behind you. The basic rule is not to read your slides or poster, nor tell the audience to read what the slide or poster says. Think of your slides or display material as a reminder to yourself of what you are supposed to say in detail and leave the noncritical words out of the slide and off the poster as it is an even easier source to pack with unreadable information. When you develop a presentation imagine you are a novice to the field who would like to be educated and taken on a journey while seeing and hearing the presentation. What can I learn in these few minutes? As the presenter, also think ‘what can I pass to the audience in these few minutes?' Further advice on how to plan, focus and arrange material to support key messages is available [ 7,8 ].

Results are the key part of any scientific presentation, podium, poster or lecture, and the most time, space and careful ascertainment should be allotted to this section as is necessary and feasible. It is vital to pack your presentation with data that support your key messages. Remember, a picture is worth a thousand words but show only quint-essential images or graphs. If appropriate include statistics and make this easy in structure, i.e. use formats or values known by everybody such as odds ratios, Kaplan Meier curves, etc. (do not forget to include these data in the abstract as abstracts without data, numbers and calculations are often low rated or rejected). After presenting data, show what you think of that or what the limitations are since you thought more about this than the audience, at least through preparation of your own presentation.

The last two concluding paragraphs (poster), comments (this section of a lecture), or slides (podium) are supposed to cover study limitations and conclusions. These should be the most carefully thought through, strategically worded and evidence-based part of your presentation. Your reputation depends on the quality of data interpretation. Also, think about a take-home message with the main message you want to be remembered. When practicing your presentations, deliver your talk to your nonmedical spouse, boyfriend or girlfriend: by the end of your presentation he or she should be able to repeat the take home message with best-prepared presentations.

After conclusions, an ‘Acknowledgements' slide is nice to have at the end showing whom you are grateful to, but it will not rescue a hopeless presentation. The ‘thanks to my colleagues' should not come at the expense of time, quality and content of your scientific presentation. There is no need to thank multiple people like they often do at the Oscars. You have to rationally consider who and when to acknowledge if their functions were important to your work but they were not listed among coauthors. If you received funding to support your work, it is very important where appropriate or at the end of the presentation to acknowledge your sponsors or grant providers (such as NIH Institute and grant number, MRC grant, INSERM or DFG labels, etc.). The higher the scientific level of the grant donors, the more your presentation will be recognized.

While preparing any part of your presentation, remind yourself to check whether the included material is any good and worthy of inclusion. You can simply ask, ‘am I wasting time during the oral presentation or space in the poster by including this and that?' The answer lies in checking if this material is directly related to the study aim, data obtained, or in support of conclusions drawn.

Table 1 summarizes how you should structure the sequence of slides for the podium presentation. If you are only given 8 min to present + 2 min for questions (10 min total), you can see that with 8 mandatory slides you are already at the limit of 1 min per slide. In due course, we will give you tips on how to reallocate time within your presentation to expand the Methods and, most importantly, the Results section as needed.

Basic structure for a podium presentation of an original paper

Always clarify study methods. Posters offer a greater freedom since you can show details of your experimental setup or the methodology of your study design. A podium presentation often requires abbreviated mention of key elements of design, scales, inclusion/exclusion criteria, intervention or dependent variables and outcomes. This requires diligent work with your coauthors and biostatisticians to make sure that you are brief but clear and sufficient.

A well-assembled Methods section will lead to a shorter Results summary since your clear statement of the study aim and key methodology logically leads to audience anticipation of the primary end-point findings. There are key messages and delivered data points that distinguish effective and clear presentations from those resulting in confusion and further guesswork.

Effective presenters capture audience attention and stay focused on key messages [ 1,2,3,6,7,8 ]. A study was performed at scientific conferences asking reviewers to identify the best features of effective presentations [ 3 . ]The most frequent comments on best features of presentations with respect to ‘content' were identifying a key concept (43% of presentations) and relevance (43%). Best features in evaluations of ‘slides' were clarity (50%), graphics (27.3%) and readability of the text and font size (23%). Finally, best features in ‘presentation style' were clarity (59%), pace (52%), voice (48%), engaging with the audience (43%), addressing questions (34%) and eye contact (28%) [ 3 ].

Here are some tips on how to avoid forcing yourself to rush during a talk. Before you start (usually in the intermission or just before your session) familiarize yourself with the podium and learn how to advance slides and operate the pointer or point with the mouse. If you stumble at the beginning, you start your presentation with a time deficit.

Get to the podium while you are being introduced and start right away (it is the responsibility of the moderator to properly announce you, your team and the title of the talk and it is the responsibility of the conference organizers to have your title slide showing during the moderator's announcement). Do not read or repeat your study title. Thank the moderators and while the title slide is showing you may consider briefly thanking your coauthors/mentor here in just a few seconds.

Show the ‘Conflicts of Interest' slide next and disclose if any conflicts are related to the study subject. If they exist, conflicts should be acknowledged briefly but clearly. Do not show a slide with several conflicts and tell the audience ‘here are my conflicts' and switch to the next slide. It is important to simply say, ‘pertinent to this study I have …' or ‘this study includes an off-label or investigational use of …'. Now you are logically ready to turn to the subject of your presentation.

Start with a brief summary of what is known and why is it important to investigate the subject. This -introduces the audience to the subject of research and starts the flow of logic. If you are facing a challenge to present a complex study within in a short allotted period of time (such as 8 min for podium or a just a few minutes during a guided poster tour), do not waste time. You may cut to the chase and simply say why you did the study. Coming with straight forward messages, which are authentic and concerned about the scientific question, gets you more credit with the audience than careful orchestration of a perceived equipoise. However, we have digressed.

For an effective message delivery, identify two people towards opposite far ends of the audience and speak as if you are personally talking to one of them at a time and alternate between them. If lights shining in your face are too bright, still look towards the back of the room (or from time to time directly into the camera if your talk is being shown on monitors in a large ballroom) and do not bury your head into the podium or notes that you might have brought with you. The nonverbal part of any presentation and the presenter's body language are also important [ 6 ]. At all cost avoid bringing notes with you to any scientific presentation since you should have practiced your talk enough to remember it or you should be familiar with the subject of your lecture to the point that even if you have just been woken up, you can still maintain an intelligent conversation. Do not count on ‘it will come to me' - practice your talk! Further advice on effective presenting skill is available [ 2 ].