- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Findings – Types Examples and Writing Guide

Research Findings – Types Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Findings

Definition:

Research findings refer to the results obtained from a study or investigation conducted through a systematic and scientific approach. These findings are the outcomes of the data analysis, interpretation, and evaluation carried out during the research process.

Types of Research Findings

There are two main types of research findings:

Qualitative Findings

Qualitative research is an exploratory research method used to understand the complexities of human behavior and experiences. Qualitative findings are non-numerical and descriptive data that describe the meaning and interpretation of the data collected. Examples of qualitative findings include quotes from participants, themes that emerge from the data, and descriptions of experiences and phenomena.

Quantitative Findings

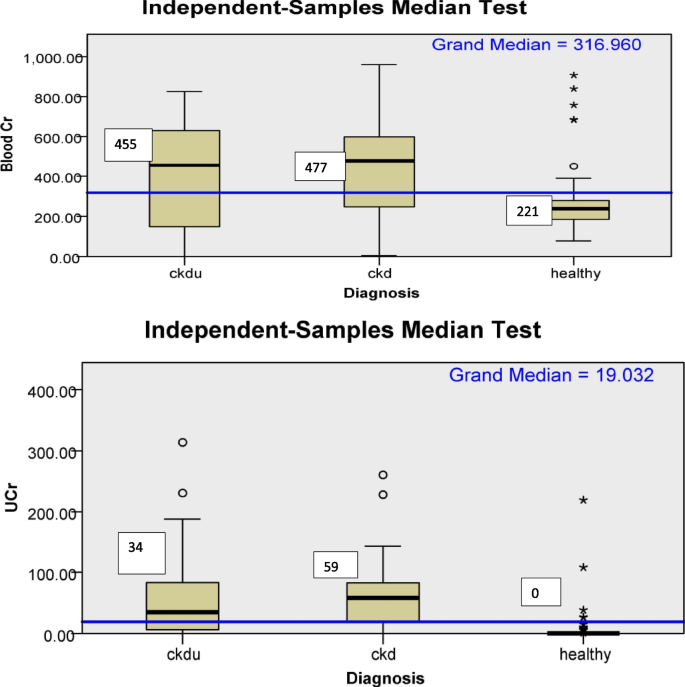

Quantitative research is a research method that uses numerical data and statistical analysis to measure and quantify a phenomenon or behavior. Quantitative findings include numerical data such as mean, median, and mode, as well as statistical analyses such as t-tests, ANOVA, and regression analysis. These findings are often presented in tables, graphs, or charts.

Both qualitative and quantitative findings are important in research and can provide different insights into a research question or problem. Combining both types of findings can provide a more comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon and improve the validity and reliability of research results.

Parts of Research Findings

Research findings typically consist of several parts, including:

- Introduction: This section provides an overview of the research topic and the purpose of the study.

- Literature Review: This section summarizes previous research studies and findings that are relevant to the current study.

- Methodology : This section describes the research design, methods, and procedures used in the study, including details on the sample, data collection, and data analysis.

- Results : This section presents the findings of the study, including statistical analyses and data visualizations.

- Discussion : This section interprets the results and explains what they mean in relation to the research question(s) and hypotheses. It may also compare and contrast the current findings with previous research studies and explore any implications or limitations of the study.

- Conclusion : This section provides a summary of the key findings and the main conclusions of the study.

- Recommendations: This section suggests areas for further research and potential applications or implications of the study’s findings.

How to Write Research Findings

Writing research findings requires careful planning and attention to detail. Here are some general steps to follow when writing research findings:

- Organize your findings: Before you begin writing, it’s essential to organize your findings logically. Consider creating an outline or a flowchart that outlines the main points you want to make and how they relate to one another.

- Use clear and concise language : When presenting your findings, be sure to use clear and concise language that is easy to understand. Avoid using jargon or technical terms unless they are necessary to convey your meaning.

- Use visual aids : Visual aids such as tables, charts, and graphs can be helpful in presenting your findings. Be sure to label and title your visual aids clearly, and make sure they are easy to read.

- Use headings and subheadings: Using headings and subheadings can help organize your findings and make them easier to read. Make sure your headings and subheadings are clear and descriptive.

- Interpret your findings : When presenting your findings, it’s important to provide some interpretation of what the results mean. This can include discussing how your findings relate to the existing literature, identifying any limitations of your study, and suggesting areas for future research.

- Be precise and accurate : When presenting your findings, be sure to use precise and accurate language. Avoid making generalizations or overstatements and be careful not to misrepresent your data.

- Edit and revise: Once you have written your research findings, be sure to edit and revise them carefully. Check for grammar and spelling errors, make sure your formatting is consistent, and ensure that your writing is clear and concise.

Research Findings Example

Following is a Research Findings Example sample for students:

Title: The Effects of Exercise on Mental Health

Sample : 500 participants, both men and women, between the ages of 18-45.

Methodology : Participants were divided into two groups. The first group engaged in 30 minutes of moderate intensity exercise five times a week for eight weeks. The second group did not exercise during the study period. Participants in both groups completed a questionnaire that assessed their mental health before and after the study period.

Findings : The group that engaged in regular exercise reported a significant improvement in mental health compared to the control group. Specifically, they reported lower levels of anxiety and depression, improved mood, and increased self-esteem.

Conclusion : Regular exercise can have a positive impact on mental health and may be an effective intervention for individuals experiencing symptoms of anxiety or depression.

Applications of Research Findings

Research findings can be applied in various fields to improve processes, products, services, and outcomes. Here are some examples:

- Healthcare : Research findings in medicine and healthcare can be applied to improve patient outcomes, reduce morbidity and mortality rates, and develop new treatments for various diseases.

- Education : Research findings in education can be used to develop effective teaching methods, improve learning outcomes, and design new educational programs.

- Technology : Research findings in technology can be applied to develop new products, improve existing products, and enhance user experiences.

- Business : Research findings in business can be applied to develop new strategies, improve operations, and increase profitability.

- Public Policy: Research findings can be used to inform public policy decisions on issues such as environmental protection, social welfare, and economic development.

- Social Sciences: Research findings in social sciences can be used to improve understanding of human behavior and social phenomena, inform public policy decisions, and develop interventions to address social issues.

- Agriculture: Research findings in agriculture can be applied to improve crop yields, develop new farming techniques, and enhance food security.

- Sports : Research findings in sports can be applied to improve athlete performance, reduce injuries, and develop new training programs.

When to use Research Findings

Research findings can be used in a variety of situations, depending on the context and the purpose. Here are some examples of when research findings may be useful:

- Decision-making : Research findings can be used to inform decisions in various fields, such as business, education, healthcare, and public policy. For example, a business may use market research findings to make decisions about new product development or marketing strategies.

- Problem-solving : Research findings can be used to solve problems or challenges in various fields, such as healthcare, engineering, and social sciences. For example, medical researchers may use findings from clinical trials to develop new treatments for diseases.

- Policy development : Research findings can be used to inform the development of policies in various fields, such as environmental protection, social welfare, and economic development. For example, policymakers may use research findings to develop policies aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

- Program evaluation: Research findings can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of programs or interventions in various fields, such as education, healthcare, and social services. For example, educational researchers may use findings from evaluations of educational programs to improve teaching and learning outcomes.

- Innovation: Research findings can be used to inspire or guide innovation in various fields, such as technology and engineering. For example, engineers may use research findings on materials science to develop new and innovative products.

Purpose of Research Findings

The purpose of research findings is to contribute to the knowledge and understanding of a particular topic or issue. Research findings are the result of a systematic and rigorous investigation of a research question or hypothesis, using appropriate research methods and techniques.

The main purposes of research findings are:

- To generate new knowledge : Research findings contribute to the body of knowledge on a particular topic, by adding new information, insights, and understanding to the existing knowledge base.

- To test hypotheses or theories : Research findings can be used to test hypotheses or theories that have been proposed in a particular field or discipline. This helps to determine the validity and reliability of the hypotheses or theories, and to refine or develop new ones.

- To inform practice: Research findings can be used to inform practice in various fields, such as healthcare, education, and business. By identifying best practices and evidence-based interventions, research findings can help practitioners to make informed decisions and improve outcomes.

- To identify gaps in knowledge: Research findings can help to identify gaps in knowledge and understanding of a particular topic, which can then be addressed by further research.

- To contribute to policy development: Research findings can be used to inform policy development in various fields, such as environmental protection, social welfare, and economic development. By providing evidence-based recommendations, research findings can help policymakers to develop effective policies that address societal challenges.

Characteristics of Research Findings

Research findings have several key characteristics that distinguish them from other types of information or knowledge. Here are some of the main characteristics of research findings:

- Objective : Research findings are based on a systematic and rigorous investigation of a research question or hypothesis, using appropriate research methods and techniques. As such, they are generally considered to be more objective and reliable than other types of information.

- Empirical : Research findings are based on empirical evidence, which means that they are derived from observations or measurements of the real world. This gives them a high degree of credibility and validity.

- Generalizable : Research findings are often intended to be generalizable to a larger population or context beyond the specific study. This means that the findings can be applied to other situations or populations with similar characteristics.

- Transparent : Research findings are typically reported in a transparent manner, with a clear description of the research methods and data analysis techniques used. This allows others to assess the credibility and reliability of the findings.

- Peer-reviewed: Research findings are often subject to a rigorous peer-review process, in which experts in the field review the research methods, data analysis, and conclusions of the study. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Reproducible : Research findings are often designed to be reproducible, meaning that other researchers can replicate the study using the same methods and obtain similar results. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

Advantages of Research Findings

Research findings have many advantages, which make them valuable sources of knowledge and information. Here are some of the main advantages of research findings:

- Evidence-based: Research findings are based on empirical evidence, which means that they are grounded in data and observations from the real world. This makes them a reliable and credible source of information.

- Inform decision-making: Research findings can be used to inform decision-making in various fields, such as healthcare, education, and business. By identifying best practices and evidence-based interventions, research findings can help practitioners and policymakers to make informed decisions and improve outcomes.

- Identify gaps in knowledge: Research findings can help to identify gaps in knowledge and understanding of a particular topic, which can then be addressed by further research. This contributes to the ongoing development of knowledge in various fields.

- Improve outcomes : Research findings can be used to develop and implement evidence-based practices and interventions, which have been shown to improve outcomes in various fields, such as healthcare, education, and social services.

- Foster innovation: Research findings can inspire or guide innovation in various fields, such as technology and engineering. By providing new information and understanding of a particular topic, research findings can stimulate new ideas and approaches to problem-solving.

- Enhance credibility: Research findings are generally considered to be more credible and reliable than other types of information, as they are based on rigorous research methods and are subject to peer-review processes.

Limitations of Research Findings

While research findings have many advantages, they also have some limitations. Here are some of the main limitations of research findings:

- Limited scope: Research findings are typically based on a particular study or set of studies, which may have a limited scope or focus. This means that they may not be applicable to other contexts or populations.

- Potential for bias : Research findings can be influenced by various sources of bias, such as researcher bias, selection bias, or measurement bias. This can affect the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Ethical considerations: Research findings can raise ethical considerations, particularly in studies involving human subjects. Researchers must ensure that their studies are conducted in an ethical and responsible manner, with appropriate measures to protect the welfare and privacy of participants.

- Time and resource constraints : Research studies can be time-consuming and require significant resources, which can limit the number and scope of studies that are conducted. This can lead to gaps in knowledge or a lack of research on certain topics.

- Complexity: Some research findings can be complex and difficult to interpret, particularly in fields such as science or medicine. This can make it challenging for practitioners and policymakers to apply the findings to their work.

- Lack of generalizability : While research findings are intended to be generalizable to larger populations or contexts, there may be factors that limit their generalizability. For example, cultural or environmental factors may influence how a particular intervention or treatment works in different populations or contexts.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 30 January 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organisation, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating, and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyse the case.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

Unlike quantitative or experimental research, a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

If you find yourself aiming to simultaneously investigate and solve an issue, consider conducting action research . As its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time, and is highly iterative and flexible.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience, or phenomenon.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews, observations, and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data .

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis, with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results , and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyse its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, January 30). Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved 2 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/case-studies/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, correlational research | guide, design & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, descriptive research design | definition, methods & examples.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved April 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

What is a case study?

Applications for case study research, what is a good case study, process of case study design, benefits and limitations of case studies.

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Case studies

Case studies are essential to qualitative research , offering a lens through which researchers can investigate complex phenomena within their real-life contexts. This chapter explores the concept, purpose, applications, examples, and types of case studies and provides guidance on how to conduct case study research effectively.

Whereas quantitative methods look at phenomena at scale, case study research looks at a concept or phenomenon in considerable detail. While analyzing a single case can help understand one perspective regarding the object of research inquiry, analyzing multiple cases can help obtain a more holistic sense of the topic or issue. Let's provide a basic definition of a case study, then explore its characteristics and role in the qualitative research process.

Definition of a case study

A case study in qualitative research is a strategy of inquiry that involves an in-depth investigation of a phenomenon within its real-world context. It provides researchers with the opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of intricate details that might not be as apparent or accessible through other methods of research. The specific case or cases being studied can be a single person, group, or organization – demarcating what constitutes a relevant case worth studying depends on the researcher and their research question .

Among qualitative research methods , a case study relies on multiple sources of evidence, such as documents, artifacts, interviews , or observations , to present a complete and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. The objective is to illuminate the readers' understanding of the phenomenon beyond its abstract statistical or theoretical explanations.

Characteristics of case studies

Case studies typically possess a number of distinct characteristics that set them apart from other research methods. These characteristics include a focus on holistic description and explanation, flexibility in the design and data collection methods, reliance on multiple sources of evidence, and emphasis on the context in which the phenomenon occurs.

Furthermore, case studies can often involve a longitudinal examination of the case, meaning they study the case over a period of time. These characteristics allow case studies to yield comprehensive, in-depth, and richly contextualized insights about the phenomenon of interest.

The role of case studies in research

Case studies hold a unique position in the broader landscape of research methods aimed at theory development. They are instrumental when the primary research interest is to gain an intensive, detailed understanding of a phenomenon in its real-life context.

In addition, case studies can serve different purposes within research - they can be used for exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes, depending on the research question and objectives. This flexibility and depth make case studies a valuable tool in the toolkit of qualitative researchers.

Remember, a well-conducted case study can offer a rich, insightful contribution to both academic and practical knowledge through theory development or theory verification, thus enhancing our understanding of complex phenomena in their real-world contexts.

What is the purpose of a case study?

Case study research aims for a more comprehensive understanding of phenomena, requiring various research methods to gather information for qualitative analysis . Ultimately, a case study can allow the researcher to gain insight into a particular object of inquiry and develop a theoretical framework relevant to the research inquiry.

Why use case studies in qualitative research?

Using case studies as a research strategy depends mainly on the nature of the research question and the researcher's access to the data.

Conducting case study research provides a level of detail and contextual richness that other research methods might not offer. They are beneficial when there's a need to understand complex social phenomena within their natural contexts.

The explanatory, exploratory, and descriptive roles of case studies

Case studies can take on various roles depending on the research objectives. They can be exploratory when the research aims to discover new phenomena or define new research questions; they are descriptive when the objective is to depict a phenomenon within its context in a detailed manner; and they can be explanatory if the goal is to understand specific relationships within the studied context. Thus, the versatility of case studies allows researchers to approach their topic from different angles, offering multiple ways to uncover and interpret the data .

The impact of case studies on knowledge development

Case studies play a significant role in knowledge development across various disciplines. Analysis of cases provides an avenue for researchers to explore phenomena within their context based on the collected data.

This can result in the production of rich, practical insights that can be instrumental in both theory-building and practice. Case studies allow researchers to delve into the intricacies and complexities of real-life situations, uncovering insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

Types of case studies

In qualitative research , a case study is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on the nature of the research question and the specific objectives of the study, researchers might choose to use different types of case studies. These types differ in their focus, methodology, and the level of detail they provide about the phenomenon under investigation.

Understanding these types is crucial for selecting the most appropriate approach for your research project and effectively achieving your research goals. Let's briefly look at the main types of case studies.

Exploratory case studies

Exploratory case studies are typically conducted to develop a theory or framework around an understudied phenomenon. They can also serve as a precursor to a larger-scale research project. Exploratory case studies are useful when a researcher wants to identify the key issues or questions which can spur more extensive study or be used to develop propositions for further research. These case studies are characterized by flexibility, allowing researchers to explore various aspects of a phenomenon as they emerge, which can also form the foundation for subsequent studies.

Descriptive case studies

Descriptive case studies aim to provide a complete and accurate representation of a phenomenon or event within its context. These case studies are often based on an established theoretical framework, which guides how data is collected and analyzed. The researcher is concerned with describing the phenomenon in detail, as it occurs naturally, without trying to influence or manipulate it.

Explanatory case studies

Explanatory case studies are focused on explanation - they seek to clarify how or why certain phenomena occur. Often used in complex, real-life situations, they can be particularly valuable in clarifying causal relationships among concepts and understanding the interplay between different factors within a specific context.

Intrinsic, instrumental, and collective case studies

These three categories of case studies focus on the nature and purpose of the study. An intrinsic case study is conducted when a researcher has an inherent interest in the case itself. Instrumental case studies are employed when the case is used to provide insight into a particular issue or phenomenon. A collective case study, on the other hand, involves studying multiple cases simultaneously to investigate some general phenomena.

Each type of case study serves a different purpose and has its own strengths and challenges. The selection of the type should be guided by the research question and objectives, as well as the context and constraints of the research.

The flexibility, depth, and contextual richness offered by case studies make this approach an excellent research method for various fields of study. They enable researchers to investigate real-world phenomena within their specific contexts, capturing nuances that other research methods might miss. Across numerous fields, case studies provide valuable insights into complex issues.

Critical information systems research

Case studies provide a detailed understanding of the role and impact of information systems in different contexts. They offer a platform to explore how information systems are designed, implemented, and used and how they interact with various social, economic, and political factors. Case studies in this field often focus on examining the intricate relationship between technology, organizational processes, and user behavior, helping to uncover insights that can inform better system design and implementation.

Health research

Health research is another field where case studies are highly valuable. They offer a way to explore patient experiences, healthcare delivery processes, and the impact of various interventions in a real-world context.

Case studies can provide a deep understanding of a patient's journey, giving insights into the intricacies of disease progression, treatment effects, and the psychosocial aspects of health and illness.

Asthma research studies

Specifically within medical research, studies on asthma often employ case studies to explore the individual and environmental factors that influence asthma development, management, and outcomes. A case study can provide rich, detailed data about individual patients' experiences, from the triggers and symptoms they experience to the effectiveness of various management strategies. This can be crucial for developing patient-centered asthma care approaches.

Other fields

Apart from the fields mentioned, case studies are also extensively used in business and management research, education research, and political sciences, among many others. They provide an opportunity to delve into the intricacies of real-world situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of various phenomena.

Case studies, with their depth and contextual focus, offer unique insights across these varied fields. They allow researchers to illuminate the complexities of real-life situations, contributing to both theory and practice.

Whatever field you're in, ATLAS.ti puts your data to work for you

Download a free trial of ATLAS.ti to turn your data into insights.

Understanding the key elements of case study design is crucial for conducting rigorous and impactful case study research. A well-structured design guides the researcher through the process, ensuring that the study is methodologically sound and its findings are reliable and valid. The main elements of case study design include the research question , propositions, units of analysis, and the logic linking the data to the propositions.

The research question is the foundation of any research study. A good research question guides the direction of the study and informs the selection of the case, the methods of collecting data, and the analysis techniques. A well-formulated research question in case study research is typically clear, focused, and complex enough to merit further detailed examination of the relevant case(s).

Propositions

Propositions, though not necessary in every case study, provide a direction by stating what we might expect to find in the data collected. They guide how data is collected and analyzed by helping researchers focus on specific aspects of the case. They are particularly important in explanatory case studies, which seek to understand the relationships among concepts within the studied phenomenon.

Units of analysis

The unit of analysis refers to the case, or the main entity or entities that are being analyzed in the study. In case study research, the unit of analysis can be an individual, a group, an organization, a decision, an event, or even a time period. It's crucial to clearly define the unit of analysis, as it shapes the qualitative data analysis process by allowing the researcher to analyze a particular case and synthesize analysis across multiple case studies to draw conclusions.

Argumentation

This refers to the inferential model that allows researchers to draw conclusions from the data. The researcher needs to ensure that there is a clear link between the data, the propositions (if any), and the conclusions drawn. This argumentation is what enables the researcher to make valid and credible inferences about the phenomenon under study.

Understanding and carefully considering these elements in the design phase of a case study can significantly enhance the quality of the research. It can help ensure that the study is methodologically sound and its findings contribute meaningful insights about the case.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

Conducting a case study involves several steps, from defining the research question and selecting the case to collecting and analyzing data . This section outlines these key stages, providing a practical guide on how to conduct case study research.

Defining the research question

The first step in case study research is defining a clear, focused research question. This question should guide the entire research process, from case selection to analysis. It's crucial to ensure that the research question is suitable for a case study approach. Typically, such questions are exploratory or descriptive in nature and focus on understanding a phenomenon within its real-life context.

Selecting and defining the case

The selection of the case should be based on the research question and the objectives of the study. It involves choosing a unique example or a set of examples that provide rich, in-depth data about the phenomenon under investigation. After selecting the case, it's crucial to define it clearly, setting the boundaries of the case, including the time period and the specific context.

Previous research can help guide the case study design. When considering a case study, an example of a case could be taken from previous case study research and used to define cases in a new research inquiry. Considering recently published examples can help understand how to select and define cases effectively.

Developing a detailed case study protocol

A case study protocol outlines the procedures and general rules to be followed during the case study. This includes the data collection methods to be used, the sources of data, and the procedures for analysis. Having a detailed case study protocol ensures consistency and reliability in the study.

The protocol should also consider how to work with the people involved in the research context to grant the research team access to collecting data. As mentioned in previous sections of this guide, establishing rapport is an essential component of qualitative research as it shapes the overall potential for collecting and analyzing data.

Collecting data

Gathering data in case study research often involves multiple sources of evidence, including documents, archival records, interviews, observations, and physical artifacts. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of the case. The process for gathering data should be systematic and carefully documented to ensure the reliability and validity of the study.

Analyzing and interpreting data

The next step is analyzing the data. This involves organizing the data , categorizing it into themes or patterns , and interpreting these patterns to answer the research question. The analysis might also involve comparing the findings with prior research or theoretical propositions.

Writing the case study report

The final step is writing the case study report . This should provide a detailed description of the case, the data, the analysis process, and the findings. The report should be clear, organized, and carefully written to ensure that the reader can understand the case and the conclusions drawn from it.

Each of these steps is crucial in ensuring that the case study research is rigorous, reliable, and provides valuable insights about the case.

The type, depth, and quality of data in your study can significantly influence the validity and utility of the study. In case study research, data is usually collected from multiple sources to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case. This section will outline the various methods of collecting data used in case study research and discuss considerations for ensuring the quality of the data.

Interviews are a common method of gathering data in case study research. They can provide rich, in-depth data about the perspectives, experiences, and interpretations of the individuals involved in the case. Interviews can be structured , semi-structured , or unstructured , depending on the research question and the degree of flexibility needed.

Observations

Observations involve the researcher observing the case in its natural setting, providing first-hand information about the case and its context. Observations can provide data that might not be revealed in interviews or documents, such as non-verbal cues or contextual information.

Documents and artifacts

Documents and archival records provide a valuable source of data in case study research. They can include reports, letters, memos, meeting minutes, email correspondence, and various public and private documents related to the case.

These records can provide historical context, corroborate evidence from other sources, and offer insights into the case that might not be apparent from interviews or observations.

Physical artifacts refer to any physical evidence related to the case, such as tools, products, or physical environments. These artifacts can provide tangible insights into the case, complementing the data gathered from other sources.

Ensuring the quality of data collection

Determining the quality of data in case study research requires careful planning and execution. It's crucial to ensure that the data is reliable, accurate, and relevant to the research question. This involves selecting appropriate methods of collecting data, properly training interviewers or observers, and systematically recording and storing the data. It also includes considering ethical issues related to collecting and handling data, such as obtaining informed consent and ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

Analyzing case study research involves making sense of the rich, detailed data to answer the research question. This process can be challenging due to the volume and complexity of case study data. However, a systematic and rigorous approach to analysis can ensure that the findings are credible and meaningful. This section outlines the main steps and considerations in analyzing data in case study research.

Organizing the data

The first step in the analysis is organizing the data. This involves sorting the data into manageable sections, often according to the data source or the theme. This step can also involve transcribing interviews, digitizing physical artifacts, or organizing observational data.

Categorizing and coding the data

Once the data is organized, the next step is to categorize or code the data. This involves identifying common themes, patterns, or concepts in the data and assigning codes to relevant data segments. Coding can be done manually or with the help of software tools, and in either case, qualitative analysis software can greatly facilitate the entire coding process. Coding helps to reduce the data to a set of themes or categories that can be more easily analyzed.

Identifying patterns and themes

After coding the data, the researcher looks for patterns or themes in the coded data. This involves comparing and contrasting the codes and looking for relationships or patterns among them. The identified patterns and themes should help answer the research question.

Interpreting the data

Once patterns and themes have been identified, the next step is to interpret these findings. This involves explaining what the patterns or themes mean in the context of the research question and the case. This interpretation should be grounded in the data, but it can also involve drawing on theoretical concepts or prior research.

Verification of the data

The last step in the analysis is verification. This involves checking the accuracy and consistency of the analysis process and confirming that the findings are supported by the data. This can involve re-checking the original data, checking the consistency of codes, or seeking feedback from research participants or peers.

Like any research method , case study research has its strengths and limitations. Researchers must be aware of these, as they can influence the design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.

Understanding the strengths and limitations of case study research can also guide researchers in deciding whether this approach is suitable for their research question . This section outlines some of the key strengths and limitations of case study research.

Benefits include the following:

- Rich, detailed data: One of the main strengths of case study research is that it can generate rich, detailed data about the case. This can provide a deep understanding of the case and its context, which can be valuable in exploring complex phenomena.

- Flexibility: Case study research is flexible in terms of design , data collection , and analysis . A sufficient degree of flexibility allows the researcher to adapt the study according to the case and the emerging findings.

- Real-world context: Case study research involves studying the case in its real-world context, which can provide valuable insights into the interplay between the case and its context.

- Multiple sources of evidence: Case study research often involves collecting data from multiple sources , which can enhance the robustness and validity of the findings.

On the other hand, researchers should consider the following limitations:

- Generalizability: A common criticism of case study research is that its findings might not be generalizable to other cases due to the specificity and uniqueness of each case.

- Time and resource intensive: Case study research can be time and resource intensive due to the depth of the investigation and the amount of collected data.

- Complexity of analysis: The rich, detailed data generated in case study research can make analyzing the data challenging.

- Subjectivity: Given the nature of case study research, there may be a higher degree of subjectivity in interpreting the data , so researchers need to reflect on this and transparently convey to audiences how the research was conducted.

Being aware of these strengths and limitations can help researchers design and conduct case study research effectively and interpret and report the findings appropriately.

Ready to analyze your data with ATLAS.ti?

See how our intuitive software can draw key insights from your data with a free trial today.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?

Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

Verywell / Colleen Tighe

- Pros and Cons

What Types of Case Studies Are Out There?

Where do you find data for a case study, how do i write a psychology case study.

A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work.

The point of a case study is to learn as much as possible about an individual or group so that the information can be generalized to many others. Unfortunately, case studies tend to be highly subjective, and it is sometimes difficult to generalize results to a larger population.

While case studies focus on a single individual or group, they follow a format similar to other types of psychology writing. If you are writing a case study, we got you—here are some rules of APA format to reference.

At a Glance

A case study, or an in-depth study of a person, group, or event, can be a useful research tool when used wisely. In many cases, case studies are best used in situations where it would be difficult or impossible for you to conduct an experiment. They are helpful for looking at unique situations and allow researchers to gather a lot of˜ information about a specific individual or group of people. However, it's important to be cautious of any bias we draw from them as they are highly subjective.

What Are the Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies?

A case study can have its strengths and weaknesses. Researchers must consider these pros and cons before deciding if this type of study is appropriate for their needs.

One of the greatest advantages of a case study is that it allows researchers to investigate things that are often difficult or impossible to replicate in a lab. Some other benefits of a case study:

- Allows researchers to capture information on the 'how,' 'what,' and 'why,' of something that's implemented

- Gives researchers the chance to collect information on why one strategy might be chosen over another

- Permits researchers to develop hypotheses that can be explored in experimental research

On the other hand, a case study can have some drawbacks:

- It cannot necessarily be generalized to the larger population

- Cannot demonstrate cause and effect

- It may not be scientifically rigorous

- It can lead to bias

Researchers may choose to perform a case study if they want to explore a unique or recently discovered phenomenon. Through their insights, researchers develop additional ideas and study questions that might be explored in future studies.

It's important to remember that the insights from case studies cannot be used to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables. However, case studies may be used to develop hypotheses that can then be addressed in experimental research.

Case Study Examples

There have been a number of notable case studies in the history of psychology. Much of Freud's work and theories were developed through individual case studies. Some great examples of case studies in psychology include:

- Anna O : Anna O. was a pseudonym of a woman named Bertha Pappenheim, a patient of a physician named Josef Breuer. While she was never a patient of Freud's, Freud and Breuer discussed her case extensively. The woman was experiencing symptoms of a condition that was then known as hysteria and found that talking about her problems helped relieve her symptoms. Her case played an important part in the development of talk therapy as an approach to mental health treatment.

- Phineas Gage : Phineas Gage was a railroad employee who experienced a terrible accident in which an explosion sent a metal rod through his skull, damaging important portions of his brain. Gage recovered from his accident but was left with serious changes in both personality and behavior.

- Genie : Genie was a young girl subjected to horrific abuse and isolation. The case study of Genie allowed researchers to study whether language learning was possible, even after missing critical periods for language development. Her case also served as an example of how scientific research may interfere with treatment and lead to further abuse of vulnerable individuals.

Such cases demonstrate how case research can be used to study things that researchers could not replicate in experimental settings. In Genie's case, her horrific abuse denied her the opportunity to learn a language at critical points in her development.

This is clearly not something researchers could ethically replicate, but conducting a case study on Genie allowed researchers to study phenomena that are otherwise impossible to reproduce.

There are a few different types of case studies that psychologists and other researchers might use:

- Collective case studies : These involve studying a group of individuals. Researchers might study a group of people in a certain setting or look at an entire community. For example, psychologists might explore how access to resources in a community has affected the collective mental well-being of those who live there.

- Descriptive case studies : These involve starting with a descriptive theory. The subjects are then observed, and the information gathered is compared to the pre-existing theory.

- Explanatory case studies : These are often used to do causal investigations. In other words, researchers are interested in looking at factors that may have caused certain things to occur.

- Exploratory case studies : These are sometimes used as a prelude to further, more in-depth research. This allows researchers to gather more information before developing their research questions and hypotheses .

- Instrumental case studies : These occur when the individual or group allows researchers to understand more than what is initially obvious to observers.

- Intrinsic case studies : This type of case study is when the researcher has a personal interest in the case. Jean Piaget's observations of his own children are good examples of how an intrinsic case study can contribute to the development of a psychological theory.

The three main case study types often used are intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Intrinsic case studies are useful for learning about unique cases. Instrumental case studies help look at an individual to learn more about a broader issue. A collective case study can be useful for looking at several cases simultaneously.

The type of case study that psychology researchers use depends on the unique characteristics of the situation and the case itself.

There are a number of different sources and methods that researchers can use to gather information about an individual or group. Six major sources that have been identified by researchers are:

- Archival records : Census records, survey records, and name lists are examples of archival records.

- Direct observation : This strategy involves observing the subject, often in a natural setting . While an individual observer is sometimes used, it is more common to utilize a group of observers.

- Documents : Letters, newspaper articles, administrative records, etc., are the types of documents often used as sources.

- Interviews : Interviews are one of the most important methods for gathering information in case studies. An interview can involve structured survey questions or more open-ended questions.

- Participant observation : When the researcher serves as a participant in events and observes the actions and outcomes, it is called participant observation.

- Physical artifacts : Tools, objects, instruments, and other artifacts are often observed during a direct observation of the subject.

If you have been directed to write a case study for a psychology course, be sure to check with your instructor for any specific guidelines you need to follow. If you are writing your case study for a professional publication, check with the publisher for their specific guidelines for submitting a case study.

Here is a general outline of what should be included in a case study.

Section 1: A Case History

This section will have the following structure and content:

Background information : The first section of your paper will present your client's background. Include factors such as age, gender, work, health status, family mental health history, family and social relationships, drug and alcohol history, life difficulties, goals, and coping skills and weaknesses.

Description of the presenting problem : In the next section of your case study, you will describe the problem or symptoms that the client presented with.

Describe any physical, emotional, or sensory symptoms reported by the client. Thoughts, feelings, and perceptions related to the symptoms should also be noted. Any screening or diagnostic assessments that are used should also be described in detail and all scores reported.

Your diagnosis : Provide your diagnosis and give the appropriate Diagnostic and Statistical Manual code. Explain how you reached your diagnosis, how the client's symptoms fit the diagnostic criteria for the disorder(s), or any possible difficulties in reaching a diagnosis.

Section 2: Treatment Plan

This portion of the paper will address the chosen treatment for the condition. This might also include the theoretical basis for the chosen treatment or any other evidence that might exist to support why this approach was chosen.

- Cognitive behavioral approach : Explain how a cognitive behavioral therapist would approach treatment. Offer background information on cognitive behavioral therapy and describe the treatment sessions, client response, and outcome of this type of treatment. Make note of any difficulties or successes encountered by your client during treatment.

- Humanistic approach : Describe a humanistic approach that could be used to treat your client, such as client-centered therapy . Provide information on the type of treatment you chose, the client's reaction to the treatment, and the end result of this approach. Explain why the treatment was successful or unsuccessful.

- Psychoanalytic approach : Describe how a psychoanalytic therapist would view the client's problem. Provide some background on the psychoanalytic approach and cite relevant references. Explain how psychoanalytic therapy would be used to treat the client, how the client would respond to therapy, and the effectiveness of this treatment approach.

- Pharmacological approach : If treatment primarily involves the use of medications, explain which medications were used and why. Provide background on the effectiveness of these medications and how monotherapy may compare with an approach that combines medications with therapy or other treatments.

This section of a case study should also include information about the treatment goals, process, and outcomes.

When you are writing a case study, you should also include a section where you discuss the case study itself, including the strengths and limitiations of the study. You should note how the findings of your case study might support previous research.

In your discussion section, you should also describe some of the implications of your case study. What ideas or findings might require further exploration? How might researchers go about exploring some of these questions in additional studies?

Need More Tips?

Here are a few additional pointers to keep in mind when formatting your case study:

- Never refer to the subject of your case study as "the client." Instead, use their name or a pseudonym.

- Read examples of case studies to gain an idea about the style and format.

- Remember to use APA format when citing references .

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011;11:100.

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011 Jun 27;11:100. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Gagnon, Yves-Chantal. The Case Study as Research Method: A Practical Handbook . Canada, Chicago Review Press Incorporated DBA Independent Pub Group, 2010.

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . United States, SAGE Publications, 2017.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Published: 22 November 2022

Single case studies are a powerful tool for developing, testing and extending theories

- Lyndsey Nickels ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0311-3524 1 , 2 ,

- Simon Fischer-Baum ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6067-0538 3 &

- Wendy Best ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8375-5916 4

Nature Reviews Psychology volume 1 , pages 733–747 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

627 Accesses

5 Citations

26 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Neurological disorders

Psychology embraces a diverse range of methodologies. However, most rely on averaging group data to draw conclusions. In this Perspective, we argue that single case methodology is a valuable tool for developing and extending psychological theories. We stress the importance of single case and case series research, drawing on classic and contemporary cases in which cognitive and perceptual deficits provide insights into typical cognitive processes in domains such as memory, delusions, reading and face perception. We unpack the key features of single case methodology, describe its strengths, its value in adjudicating between theories, and outline its benefits for a better understanding of deficits and hence more appropriate interventions. The unique insights that single case studies have provided illustrate the value of in-depth investigation within an individual. Single case methodology has an important place in the psychologist’s toolkit and it should be valued as a primary research tool.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

55,14 € per year

only 4,60 € per issue

Buy this article

Purchase on Springer Link

Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Microdosing with psilocybin mushrooms: a double-blind placebo-controlled study

Federico Cavanna, Stephanie Muller, … Enzo Tagliazucchi

Adults who microdose psychedelics report health related motivations and lower levels of anxiety and depression compared to non-microdosers

Joseph M. Rootman, Pamela Kryskow, … Zach Walsh

The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence

Joanna Moncrieff, Ruth E. Cooper, … Mark A. Horowitz

Corkin, S. Permanent Present Tense: The Unforgettable Life Of The Amnesic Patient, H. M . Vol. XIX, 364 (Basic Books, 2013).

Lilienfeld, S. O. Psychology: From Inquiry To Understanding (Pearson, 2019).

Schacter, D. L., Gilbert, D. T., Nock, M. K. & Wegner, D. M. Psychology (Worth Publishers, 2019).

Eysenck, M. W. & Brysbaert, M. Fundamentals Of Cognition (Routledge, 2018).

Squire, L. R. Memory and brain systems: 1969–2009. J. Neurosci. 29 , 12711–12716 (2009).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Corkin, S. What’s new with the amnesic patient H.M.? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3 , 153–160 (2002).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Schubert, T. M. et al. Lack of awareness despite complex visual processing: evidence from event-related potentials in a case of selective metamorphopsia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117 , 16055–16064 (2020).

Behrmann, M. & Plaut, D. C. Bilateral hemispheric processing of words and faces: evidence from word impairments in prosopagnosia and face impairments in pure alexia. Cereb. Cortex 24 , 1102–1118 (2014).

Plaut, D. C. & Behrmann, M. Complementary neural representations for faces and words: a computational exploration. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 28 , 251–275 (2011).

Haxby, J. V. et al. Distributed and overlapping representations of faces and objects in ventral temporal cortex. Science 293 , 2425–2430 (2001).

Hirshorn, E. A. et al. Decoding and disrupting left midfusiform gyrus activity during word reading. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113 , 8162–8167 (2016).

Kosakowski, H. L. et al. Selective responses to faces, scenes, and bodies in the ventral visual pathway of infants. Curr. Biol. 32 , 265–274.e5 (2022).

Harlow, J. Passage of an iron rod through the head. Boston Med. Surgical J . https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.11.2.281 (1848).

Broca, P. Remarks on the seat of the faculty of articulated language, following an observation of aphemia (loss of speech). Bull. Soc. Anat. 6 , 330–357 (1861).

Google Scholar

Dejerine, J. Contribution A L’étude Anatomo-pathologique Et Clinique Des Différentes Variétés De Cécité Verbale: I. Cécité Verbale Avec Agraphie Ou Troubles Très Marqués De L’écriture; II. Cécité Verbale Pure Avec Intégrité De L’écriture Spontanée Et Sous Dictée (Société de Biologie, 1892).

Liepmann, H. Das Krankheitsbild der Apraxie (“motorischen Asymbolie”) auf Grund eines Falles von einseitiger Apraxie (Fortsetzung). Eur. Neurol. 8 , 102–116 (1900).

Article Google Scholar

Basso, A., Spinnler, H., Vallar, G. & Zanobio, M. E. Left hemisphere damage and selective impairment of auditory verbal short-term memory. A case study. Neuropsychologia 20 , 263–274 (1982).

Humphreys, G. W. & Riddoch, M. J. The fractionation of visual agnosia. In Visual Object Processing: A Cognitive Neuropsychological Approach 281–306 (Lawrence Erlbaum, 1987).

Whitworth, A., Webster, J. & Howard, D. A Cognitive Neuropsychological Approach To Assessment And Intervention In Aphasia (Psychology Press, 2014).

Caramazza, A. On drawing inferences about the structure of normal cognitive systems from the analysis of patterns of impaired performance: the case for single-patient studies. Brain Cogn. 5 , 41–66 (1986).

Caramazza, A. & McCloskey, M. The case for single-patient studies. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 5 , 517–527 (1988).

Shallice, T. Cognitive neuropsychology and its vicissitudes: the fate of Caramazza’s axioms. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 32 , 385–411 (2015).

Shallice, T. From Neuropsychology To Mental Structure (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1988).

Coltheart, M. Assumptions and methods in cognitive neuropscyhology. In The Handbook Of Cognitive Neuropsychology: What Deficits Reveal About The Human Mind (ed. Rapp, B.) 3–22 (Psychology Press, 2001).

McCloskey, M. & Chaisilprungraung, T. The value of cognitive neuropsychology: the case of vision research. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 34 , 412–419 (2017).

McCloskey, M. The future of cognitive neuropsychology. In The Handbook Of Cognitive Neuropsychology: What Deficits Reveal About The Human Mind (ed. Rapp, B.) 593–610 (Psychology Press, 2001).

Lashley, K. S. In search of the engram. In Physiological Mechanisms in Animal Behavior 454–482 (Academic Press, 1950).

Squire, L. R. & Wixted, J. T. The cognitive neuroscience of human memory since H.M. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 34 , 259–288 (2011).

Stone, G. O., Vanhoy, M. & Orden, G. C. V. Perception is a two-way street: feedforward and feedback phonology in visual word recognition. J. Mem. Lang. 36 , 337–359 (1997).

Perfetti, C. A. The psycholinguistics of spelling and reading. In Learning To Spell: Research, Theory, And Practice Across Languages 21–38 (Lawrence Erlbaum, 1997).

Nickels, L. The autocue? self-generated phonemic cues in the treatment of a disorder of reading and naming. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 9 , 155–182 (1992).

Rapp, B., Benzing, L. & Caramazza, A. The autonomy of lexical orthography. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 14 , 71–104 (1997).

Bonin, P., Roux, S. & Barry, C. Translating nonverbal pictures into verbal word names. Understanding lexical access and retrieval. In Past, Present, And Future Contributions Of Cognitive Writing Research To Cognitive Psychology 315–522 (Psychology Press, 2011).

Bonin, P., Fayol, M. & Gombert, J.-E. Role of phonological and orthographic codes in picture naming and writing: an interference paradigm study. Cah. Psychol. Cogn./Current Psychol. Cogn. 16 , 299–324 (1997).

Bonin, P., Fayol, M. & Peereman, R. Masked form priming in writing words from pictures: evidence for direct retrieval of orthographic codes. Acta Psychol. 99 , 311–328 (1998).

Bentin, S., Allison, T., Puce, A., Perez, E. & McCarthy, G. Electrophysiological studies of face perception in humans. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 8 , 551–565 (1996).

Jeffreys, D. A. Evoked potential studies of face and object processing. Vis. Cogn. 3 , 1–38 (1996).

Laganaro, M., Morand, S., Michel, C. M., Spinelli, L. & Schnider, A. ERP correlates of word production before and after stroke in an aphasic patient. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23 , 374–381 (2011).

Indefrey, P. & Levelt, W. J. M. The spatial and temporal signatures of word production components. Cognition 92 , 101–144 (2004).

Valente, A., Burki, A. & Laganaro, M. ERP correlates of word production predictors in picture naming: a trial by trial multiple regression analysis from stimulus onset to response. Front. Neurosci. 8 , 390 (2014).

Kittredge, A. K., Dell, G. S., Verkuilen, J. & Schwartz, M. F. Where is the effect of frequency in word production? Insights from aphasic picture-naming errors. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 25 , 463–492 (2008).

Domdei, N. et al. Ultra-high contrast retinal display system for single photoreceptor psychophysics. Biomed. Opt. Express 9 , 157 (2018).

Poldrack, R. A. et al. Long-term neural and physiological phenotyping of a single human. Nat. Commun. 6 , 8885 (2015).

Coltheart, M. The assumptions of cognitive neuropsychology: reflections on Caramazza (1984, 1986). Cogn. Neuropsychol. 34 , 397–402 (2017).

Badecker, W. & Caramazza, A. A final brief in the case against agrammatism: the role of theory in the selection of data. Cognition 24 , 277–282 (1986).

Fischer-Baum, S. Making sense of deviance: Identifying dissociating cases within the case series approach. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 30 , 597–617 (2013).

Nickels, L., Howard, D. & Best, W. On the use of different methodologies in cognitive neuropsychology: drink deep and from several sources. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 28 , 475–485 (2011).

Dell, G. S. & Schwartz, M. F. Who’s in and who’s out? Inclusion criteria, model evaluation, and the treatment of exceptions in case series. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 28 , 515–520 (2011).

Schwartz, M. F. & Dell, G. S. Case series investigations in cognitive neuropsychology. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 27 , 477–494 (2010).

Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 112 , 155–159 (1992).

Martin, R. C. & Allen, C. Case studies in neuropsychology. In APA Handbook Of Research Methods In Psychology Vol. 2 Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, And Biological (eds Cooper, H. et al.) 633–646 (American Psychological Association, 2012).

Leivada, E., Westergaard, M., Duñabeitia, J. A. & Rothman, J. On the phantom-like appearance of bilingualism effects on neurocognition: (how) should we proceed? Bilingualism 24 , 197–210 (2021).

Arnett, J. J. The neglected 95%: why American psychology needs to become less American. Am. Psychol. 63 , 602–614 (2008).

Stolz, J. A., Besner, D. & Carr, T. H. Implications of measures of reliability for theories of priming: activity in semantic memory is inherently noisy and uncoordinated. Vis. Cogn. 12 , 284–336 (2005).

Cipora, K. et al. A minority pulls the sample mean: on the individual prevalence of robust group-level cognitive phenomena — the instance of the SNARC effect. Preprint at psyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/bwyr3 (2019).

Andrews, S., Lo, S. & Xia, V. Individual differences in automatic semantic priming. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 43 , 1025–1039 (2017).

Tan, L. C. & Yap, M. J. Are individual differences in masked repetition and semantic priming reliable? Vis. Cogn. 24 , 182–200 (2016).