Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

16.2 Sociological Perspectives on Education

Learning objectives.

- List the major functions of education.

- Explain the problems that conflict theory sees in education.

- Describe how symbolic interactionism understands education.

The major sociological perspectives on education fall nicely into the functional, conflict, and symbolic interactionist approaches (Ballantine & Hammack, 2009). Table 16.1 “Theory Snapshot” summarizes what these approaches say.

Table 16.1 Theory Snapshot

The Functions of Education

Functional theory stresses the functions that education serves in fulfilling a society’s various needs. Perhaps the most important function of education is socialization . If children need to learn the norms, values, and skills they need to function in society, then education is a primary vehicle for such learning. Schools teach the three Rs, as we all know, but they also teach many of the society’s norms and values. In the United States, these norms and values include respect for authority, patriotism (remember the Pledge of Allegiance?), punctuality, individualism, and competition. Regarding these last two values, American students from an early age compete as individuals over grades and other rewards. The situation is quite the opposite in Japan, where, as we saw in Chapter 4 “Socialization” , children learn the traditional Japanese values of harmony and group belonging from their schooling (Schneider & Silverman, 2010). They learn to value their membership in their homeroom, or kumi , and are evaluated more on their kumi ’s performance than on their own individual performance. How well a Japanese child’s kumi does is more important than how well the child does as an individual.

A second function of education is social integration . For a society to work, functionalists say, people must subscribe to a common set of beliefs and values. As we saw, the development of such common views was a goal of the system of free, compulsory education that developed in the 19th century. Thousands of immigrant children in the United States today are learning English, U.S. history, and other subjects that help prepare them for the workforce and integrate them into American life. Such integration is a major goal of the English-only movement, whose advocates say that only English should be used to teach children whose native tongue is Spanish, Vietnamese, or whatever other language their parents speak at home. Critics of this movement say it slows down these children’s education and weakens their ethnic identity (Schildkraut, 2005).

A third function of education is social placement . Beginning in grade school, students are identified by teachers and other school officials either as bright and motivated or as less bright and even educationally challenged. Depending on how they are identified, children are taught at the level that is thought to suit them best. In this way they are prepared in the most appropriate way possible for their later station in life. Whether this process works as well as it should is an important issue, and we explore it further when we discuss school tracking shortly.

Social and cultural innovation is a fourth function of education. Our scientists cannot make important scientific discoveries and our artists and thinkers cannot come up with great works of art, poetry, and prose unless they have first been educated in the many subjects they need to know for their chosen path.

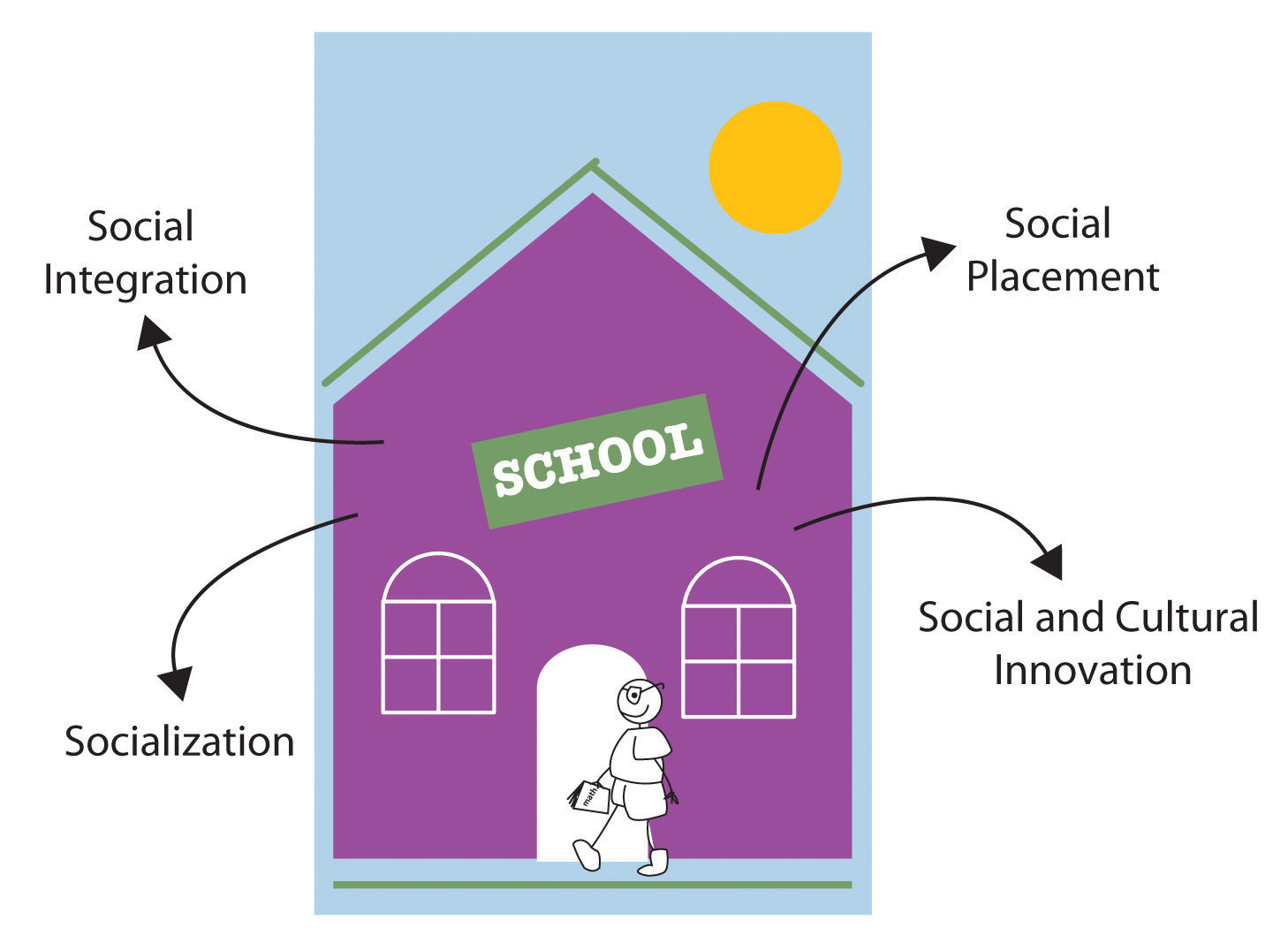

Figure 16.1 The Functions of Education

Schools ideally perform many important functions in modern society. These include socialization, social integration, social placement, and social and cultural innovation.

Education also involves several latent functions, functions that are by-products of going to school and receiving an education rather than a direct effect of the education itself. One of these is child care . Once a child starts kindergarten and then first grade, for several hours a day the child is taken care of for free. The establishment of peer relationships is another latent function of schooling. Most of us met many of our friends while we were in school at whatever grade level, and some of those friendships endure the rest of our lives. A final latent function of education is that it keeps millions of high school students out of the full-time labor force . This fact keeps the unemployment rate lower than it would be if they were in the labor force.

Education and Inequality

Conflict theory does not dispute most of the functions just described. However, it does give some of them a different slant and talks about various ways in which education perpetuates social inequality (Hill, Macrine, & Gabbard, 2010; Liston, 1990). One example involves the function of social placement. As most schools track their students starting in grade school, the students thought by their teachers to be bright are placed in the faster tracks (especially in reading and arithmetic), while the slower students are placed in the slower tracks; in high school, three common tracks are the college track, vocational track, and general track.

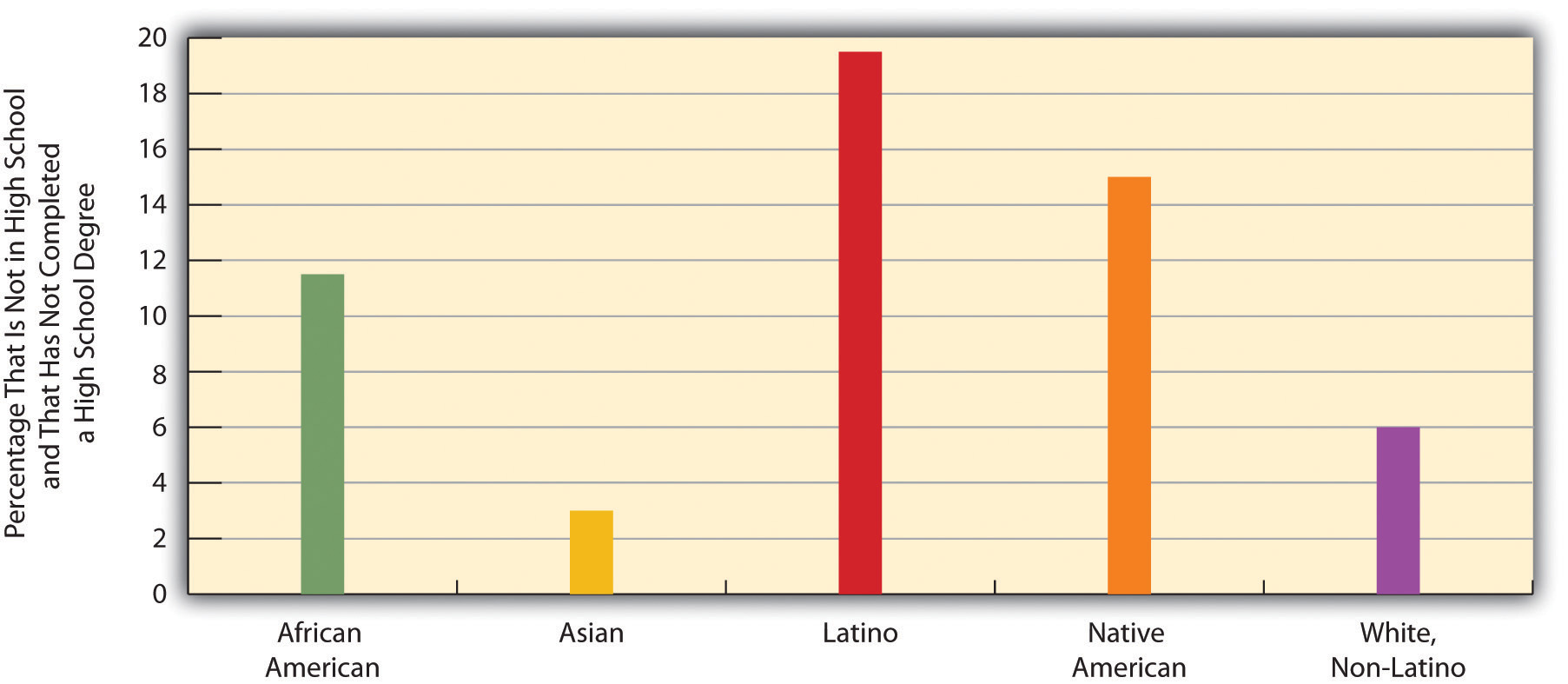

Such tracking does have its advantages; it helps ensure that bright students learn as much as their abilities allow them, and it helps ensure that slower students are not taught over their heads. But, conflict theorists say, tracking also helps perpetuate social inequality by locking students into faster and lower tracks. Worse yet, several studies show that students’ social class and race and ethnicity affect the track into which they are placed, even though their intellectual abilities and potential should be the only things that matter: white, middle-class students are more likely to be tracked “up,” while poorer students and students of color are more likely to be tracked “down.” Once they are tracked, students learn more if they are tracked up and less if they are tracked down. The latter tend to lose self-esteem and begin to think they have little academic ability and thus do worse in school because they were tracked down. In this way, tracking is thought to be good for those tracked up and bad for those tracked down. Conflict theorists thus say that tracking perpetuates social inequality based on social class and race and ethnicity (Ansalone, 2006; Oakes, 2005).

Social inequality is also perpetuated through the widespread use of standardized tests. Critics say these tests continue to be culturally biased, as they include questions whose answers are most likely to be known by white, middle-class students, whose backgrounds have afforded them various experiences that help them answer the questions. They also say that scores on standardized tests reflect students’ socioeconomic status and experiences in addition to their academic abilities. To the extent this critique is true, standardized tests perpetuate social inequality (Grodsky, Warren, & Felts, 2008).

As we will see, schools in the United States also differ mightily in their resources, learning conditions, and other aspects, all of which affect how much students can learn in them. Simply put, schools are unequal, and their very inequality helps perpetuate inequality in the larger society. Children going to the worst schools in urban areas face many more obstacles to their learning than those going to well-funded schools in suburban areas. Their lack of learning helps ensure they remain trapped in poverty and its related problems.

Conflict theorists also say that schooling teaches a hidden curriculum , by which they mean a set of values and beliefs that support the status quo, including the existing social hierarchy (Booher-Jennings, 2008) (see Chapter 4 “Socialization” ). Although no one plots this behind closed doors, our schoolchildren learn patriotic values and respect for authority from the books they read and from various classroom activities.

Symbolic Interactionism and School Behavior

Symbolic interactionist studies of education examine social interaction in the classroom, on the playground, and in other school venues. These studies help us understand what happens in the schools themselves, but they also help us understand how what occurs in school is relevant for the larger society. Some studies, for example, show how children’s playground activities reinforce gender-role socialization. Girls tend to play more cooperative games, while boys play more competitive sports (Thorne, 1993) (see Chapter 11 “Gender and Gender Inequality” ).

Another body of research shows that teachers’ views about students can affect how much the students learn. When teachers think students are smart, they tend to spend more time with them, to call on them, and to praise them when they give the right answer. Not surprisingly these students learn more because of their teachers’ behavior. But when teachers think students are less bright, they tend to spend less time with them and act in a way that leads the students to learn less. One of the first studies to find this example of a self-fulfilling prophecy was conducted by Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson (1968). They tested a group of students at the beginning of the school year and told their teachers which students were bright and which were not. They tested the students again at the end of the school year; not surprisingly the bright students had learned more during the year than the less bright ones. But it turned out that the researchers had randomly decided which students would be designated bright and less bright. Because the “bright” students learned more during the school year without actually being brighter at the beginning, their teachers’ behavior must have been the reason. In fact, their teachers did spend more time with them and praised them more often than was true for the “less bright” students. To the extent this type of self-fulfilling prophecy occurs, it helps us understand why tracking is bad for the students tracked down.

Research guided by the symbolic interactionist perspective suggests that teachers’ expectations may influence how much their students learn. When teachers expect little of their students, their students tend to learn less.

ijiwaru jimbo – Pre-school colour pack – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Other research focuses on how teachers treat girls and boys. Several studies from the 1970s through the 1990s found that teachers call on boys more often and praise them more often (American Association of University Women Educational Foundation, 1998; Jones & Dindia, 2004). Teachers did not do this consciously, but their behavior nonetheless sent an implicit message to girls that math and science are not for girls and that they are not suited to do well in these subjects. This body of research stimulated efforts to educate teachers about the ways in which they may unwittingly send these messages and about strategies they could use to promote greater interest and achievement by girls in math and science (Battey, Kafai, Nixon, & Kao, 2007).

Key Takeaways

- According to the functional perspective, education helps socialize children and prepare them for their eventual entrance into the larger society as adults.

- The conflict perspective emphasizes that education reinforces inequality in the larger society.

- The symbolic interactionist perspective focuses on social interaction in the classroom, on school playgrounds, and at other school-related venues. Social interaction contributes to gender-role socialization, and teachers’ expectations may affect their students’ performance.

For Your Review

- Review how the functionalist, conflict, and symbolic interactionist perspectives understand and explain education. Which of these three approaches do you most prefer? Why?

American Association of University Women Educational Foundation. (1998). Gender gaps: Where schools still fail our children . Washington, DC: American Association of University Women Educational Foundation.

Ansalone, G. (2006). Tracking: A return to Jim Crow. Race, Gender & Class, 13 , 1–2.

Ballantine, J. H., & Hammack, F. M. (2009). The sociology of education: A systematic analysis (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Battey, D., Kafai, Y., Nixon, A. S., & Kao, L. L. (2007). Professional development for teachers on gender equity in the sciences: Initiating the conversation. Teachers College Record, 109 (1), 221–243.

Booher-Jennings, J. (2008). Learning to label: Socialisation, gender, and the hidden curriculum of high-stakes testing. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 29 , 149–160.

Grodsky, E., Warren, J. R., & Felts, E. (2008). Testing and social stratification in American education. Annual Review of Sociology, 34 (1), 385–404.

Hill, D., Macrine, S., & Gabbard, D. (Eds.). (2010). Capitalist education: Globalisation and the politics of inequality . New York, NY: Routledge; Liston, D. P. (1990). Capitalist schools: Explanation and ethics in radical studies of schooling . New York, NY: Routledge.

Jones, S. M., & Dindia, K. (2004). A meta-analystic perspective on sex equity in the classroom. Review of Educational Research, 74 , 443–471.

Oakes, J. (2005). Keeping track: How schools structure inequality (2nd ed.). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom . New York, NY: Holt.

Schildkraut, D. J. (2005). Press “one” for English: Language policy, public opinion, and American identity . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Schneider, L., & Silverman, A. (2010). Global sociology: Introducing five contemporary societies (5th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Thorne, B. (1993). Gender play: Girls and boys in school . New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Utility Menu

Department of Sociology

- Education and Society

Schools and colleges are transforming the lives of individual learners and their families. They play a core role in society. At the same time, they are continuously transformed by politics, markets, and scientific, technological, and cultural change. Sociologists of education and higher education at Harvard are engaged in basic and applied research, both contemporary and historical, and focusing on the United States as well as on cross-national and cross-cultural analyses. The broad array of research in this cluster applies core sociological concepts, such as equity and (in)equality; race and ethnicity; social networks; immigration; stratification; organizations; culture; social mobility; socialization and others to the study of education. The research cluster has links to the Graduate School of Education (GSE), the Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in Education, the Secondary Field in Education Studies and the Mahindra Seminar on Universities: Past, Present and Future.

Affiliated Graduate Students

News related to Education and Society

Manja Klemenčič edits open-access Bloomsbury Handbook

Manja Klemenčič edited the open-access Bloomsbury Handbook of Student Politics and Representation in Higher Education having trained student leaders across the globe to contribute chapters along with established researchers.

Christina Ciocca Eller's recent paper urges college ratings focused on real-life outcomes

Faculty Spotlight: Considering the Impacts of COVID-19 on Higher Education Inequality in the United States

Amid the unprecedented disruption of COVID-19, the 2019-2020 academic year has come to a close for most college and university students in the United States. Yet many are asking: now what? Higher education leaders are offering some answers, speaking to immediate concerns like whether teaching and learning will take place on colleges campuses come the fall, how financial arrangements will be handled, and what scaled-up virtual learning might look like.

... Read more about Faculty Spotlight: Considering the Impacts of COVID-19 on Higher Education Inequality in the United States

Manja Klemencic honored as a Most Favorite Professor in the Harvard Yearbook for the Class of 2020.

Patterson to head Jamaica Education Transformation Commission

Orlando Patterson , John Cowles, Professor of Sociology, has been appointed by the Prime Minister of Jamaica to head the Jamaica Education Transformation Commission 2020,... Read more about Patterson to head Jamaica Education Transformation Commission

Advice to Students: Don't be Afraid to Ask for Help

- Comparative Sociology and Social Change

- Crime and Punishment

- Economic Sociology and Organizations

- Gender and Family

- Health and Population

- Political and Historical Sociology

- Race, Ethnicity and Immigration

- Urban Poverty and the City

Associated Faculty

- Deirdre Bloome

- Christina Ciocca Eller

- Christina Cross

- Emily Fairchild

- Manja Klemenčič

- Maël Lecoursonnais

- Joscha Legewie

Related Publications

Klemenčič, Manja, and Sabine Hoidn . Forthcoming. The Routledge International Handbook of Student-centered Learning and Teaching in Higher Education . 1st ed. Routledge.

co-editor Manja Klemenčič,, ed. 2020. Encyclopedia of International Higher Education Systems and Institutions . 1st ed. Netherlands: Springer. Publisher's Version

Cross, Christina J. 2020. “ Racial/Ethnic Differences in the Association Between Family Structure and Children’s Education ”. Journal of Marriage and Family 81 (2):691-712.

- Our Mission

What Is Education For?

Read an excerpt from a new book by Sir Ken Robinson and Kate Robinson, which calls for redesigning education for the future.

What is education for? As it happens, people differ sharply on this question. It is what is known as an “essentially contested concept.” Like “democracy” and “justice,” “education” means different things to different people. Various factors can contribute to a person’s understanding of the purpose of education, including their background and circumstances. It is also inflected by how they view related issues such as ethnicity, gender, and social class. Still, not having an agreed-upon definition of education doesn’t mean we can’t discuss it or do anything about it.

We just need to be clear on terms. There are a few terms that are often confused or used interchangeably—“learning,” “education,” “training,” and “school”—but there are important differences between them. Learning is the process of acquiring new skills and understanding. Education is an organized system of learning. Training is a type of education that is focused on learning specific skills. A school is a community of learners: a group that comes together to learn with and from each other. It is vital that we differentiate these terms: children love to learn, they do it naturally; many have a hard time with education, and some have big problems with school.

There are many assumptions of compulsory education. One is that young people need to know, understand, and be able to do certain things that they most likely would not if they were left to their own devices. What these things are and how best to ensure students learn them are complicated and often controversial issues. Another assumption is that compulsory education is a preparation for what will come afterward, like getting a good job or going on to higher education.

So, what does it mean to be educated now? Well, I believe that education should expand our consciousness, capabilities, sensitivities, and cultural understanding. It should enlarge our worldview. As we all live in two worlds—the world within you that exists only because you do, and the world around you—the core purpose of education is to enable students to understand both worlds. In today’s climate, there is also a new and urgent challenge: to provide forms of education that engage young people with the global-economic issues of environmental well-being.

This core purpose of education can be broken down into four basic purposes.

Education should enable young people to engage with the world within them as well as the world around them. In Western cultures, there is a firm distinction between the two worlds, between thinking and feeling, objectivity and subjectivity. This distinction is misguided. There is a deep correlation between our experience of the world around us and how we feel. As we explored in the previous chapters, all individuals have unique strengths and weaknesses, outlooks and personalities. Students do not come in standard physical shapes, nor do their abilities and personalities. They all have their own aptitudes and dispositions and different ways of understanding things. Education is therefore deeply personal. It is about cultivating the minds and hearts of living people. Engaging them as individuals is at the heart of raising achievement.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights emphasizes that “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights,” and that “Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms.” Many of the deepest problems in current systems of education result from losing sight of this basic principle.

Schools should enable students to understand their own cultures and to respect the diversity of others. There are various definitions of culture, but in this context the most appropriate is “the values and forms of behavior that characterize different social groups.” To put it more bluntly, it is “the way we do things around here.” Education is one of the ways that communities pass on their values from one generation to the next. For some, education is a way of preserving a culture against outside influences. For others, it is a way of promoting cultural tolerance. As the world becomes more crowded and connected, it is becoming more complex culturally. Living respectfully with diversity is not just an ethical choice, it is a practical imperative.

There should be three cultural priorities for schools: to help students understand their own cultures, to understand other cultures, and to promote a sense of cultural tolerance and coexistence. The lives of all communities can be hugely enriched by celebrating their own cultures and the practices and traditions of other cultures.

Education should enable students to become economically responsible and independent. This is one of the reasons governments take such a keen interest in education: they know that an educated workforce is essential to creating economic prosperity. Leaders of the Industrial Revolution knew that education was critical to creating the types of workforce they required, too. But the world of work has changed so profoundly since then, and continues to do so at an ever-quickening pace. We know that many of the jobs of previous decades are disappearing and being rapidly replaced by contemporary counterparts. It is almost impossible to predict the direction of advancing technologies, and where they will take us.

How can schools prepare students to navigate this ever-changing economic landscape? They must connect students with their unique talents and interests, dissolve the division between academic and vocational programs, and foster practical partnerships between schools and the world of work, so that young people can experience working environments as part of their education, not simply when it is time for them to enter the labor market.

Education should enable young people to become active and compassionate citizens. We live in densely woven social systems. The benefits we derive from them depend on our working together to sustain them. The empowerment of individuals has to be balanced by practicing the values and responsibilities of collective life, and of democracy in particular. Our freedoms in democratic societies are not automatic. They come from centuries of struggle against tyranny and autocracy and those who foment sectarianism, hatred, and fear. Those struggles are far from over. As John Dewey observed, “Democracy has to be born anew every generation, and education is its midwife.”

For a democratic society to function, it depends upon the majority of its people to be active within the democratic process. In many democracies, this is increasingly not the case. Schools should engage students in becoming active, and proactive, democratic participants. An academic civics course will scratch the surface, but to nurture a deeply rooted respect for democracy, it is essential to give young people real-life democratic experiences long before they come of age to vote.

Eight Core Competencies

The conventional curriculum is based on a collection of separate subjects. These are prioritized according to beliefs around the limited understanding of intelligence we discussed in the previous chapter, as well as what is deemed to be important later in life. The idea of “subjects” suggests that each subject, whether mathematics, science, art, or language, stands completely separate from all the other subjects. This is problematic. Mathematics, for example, is not defined only by propositional knowledge; it is a combination of types of knowledge, including concepts, processes, and methods as well as propositional knowledge. This is also true of science, art, and languages, and of all other subjects. It is therefore much more useful to focus on the concept of disciplines rather than subjects.

Disciplines are fluid; they constantly merge and collaborate. In focusing on disciplines rather than subjects we can also explore the concept of interdisciplinary learning. This is a much more holistic approach that mirrors real life more closely—it is rare that activities outside of school are as clearly segregated as conventional curriculums suggest. A journalist writing an article, for example, must be able to call upon skills of conversation, deductive reasoning, literacy, and social sciences. A surgeon must understand the academic concept of the patient’s condition, as well as the practical application of the appropriate procedure. At least, we would certainly hope this is the case should we find ourselves being wheeled into surgery.

The concept of disciplines brings us to a better starting point when planning the curriculum, which is to ask what students should know and be able to do as a result of their education. The four purposes above suggest eight core competencies that, if properly integrated into education, will equip students who leave school to engage in the economic, cultural, social, and personal challenges they will inevitably face in their lives. These competencies are curiosity, creativity, criticism, communication, collaboration, compassion, composure, and citizenship. Rather than be triggered by age, they should be interwoven from the beginning of a student’s educational journey and nurtured throughout.

From Imagine If: Creating a Future for Us All by Sir Ken Robinson, Ph.D and Kate Robinson, published by Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2022 by the Estate of Sir Kenneth Robinson and Kate Robinson.

11.2 Sociological Perspectives on Education

Learning objectives.

- List the major functions of education.

- Explain the problems that conflict theory sees in education.

- Describe how symbolic interactionism understands education.

The major sociological perspectives on education fall nicely into the functional, conflict, and symbolic interactionist approaches (Ballantine & Hammack, 2012). Ballantine, J. H., & Hammack, F. M. (2012). The sociology of education: A systematic analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Table 11.1 "Theory Snapshot" summarizes what these approaches say.

Table 11.1 Theory Snapshot

The Functions of Education

Functional theory stresses the functions that education serves in fulfilling a society’s various needs. Perhaps the most important function of education is socialization . If children are to learn the norms, values, and skills they need to function in society, then education is a primary vehicle for such learning. Schools teach the three Rs (reading, ’riting, ’rithmetic), as we all know, but they also teach many of the society’s norms and values. In the United States, these norms and values include respect for authority, patriotism (remember the Pledge of Allegiance?), punctuality, and competition (for grades and sports victories).

A second function of education is social integration . For a society to work, functionalists say, people must subscribe to a common set of beliefs and values. As we saw, the development of such common views was a goal of the system of free, compulsory education that developed in the nineteenth century. Thousands of immigrant children in the United States today are learning English, US history, and other subjects that help prepare them for the workforce and integrate them into American life.

A third function of education is social placement . Beginning in grade school, students are identified by teachers and other school officials either as bright and motivated or as less bright and even educationally challenged. Depending on how they are identified, children are taught at the level that is thought to suit them best. In this way, they are presumably prepared for their later station in life. Whether this process works as well as it should is an important issue, and we explore it further when we discuss school tracking later in this chapter.

Social and cultural innovation is a fourth function of education. Our scientists cannot make important scientific discoveries and our artists and thinkers cannot come up with great works of art, poetry, and prose unless they have first been educated in the many subjects they need to know for their chosen path.

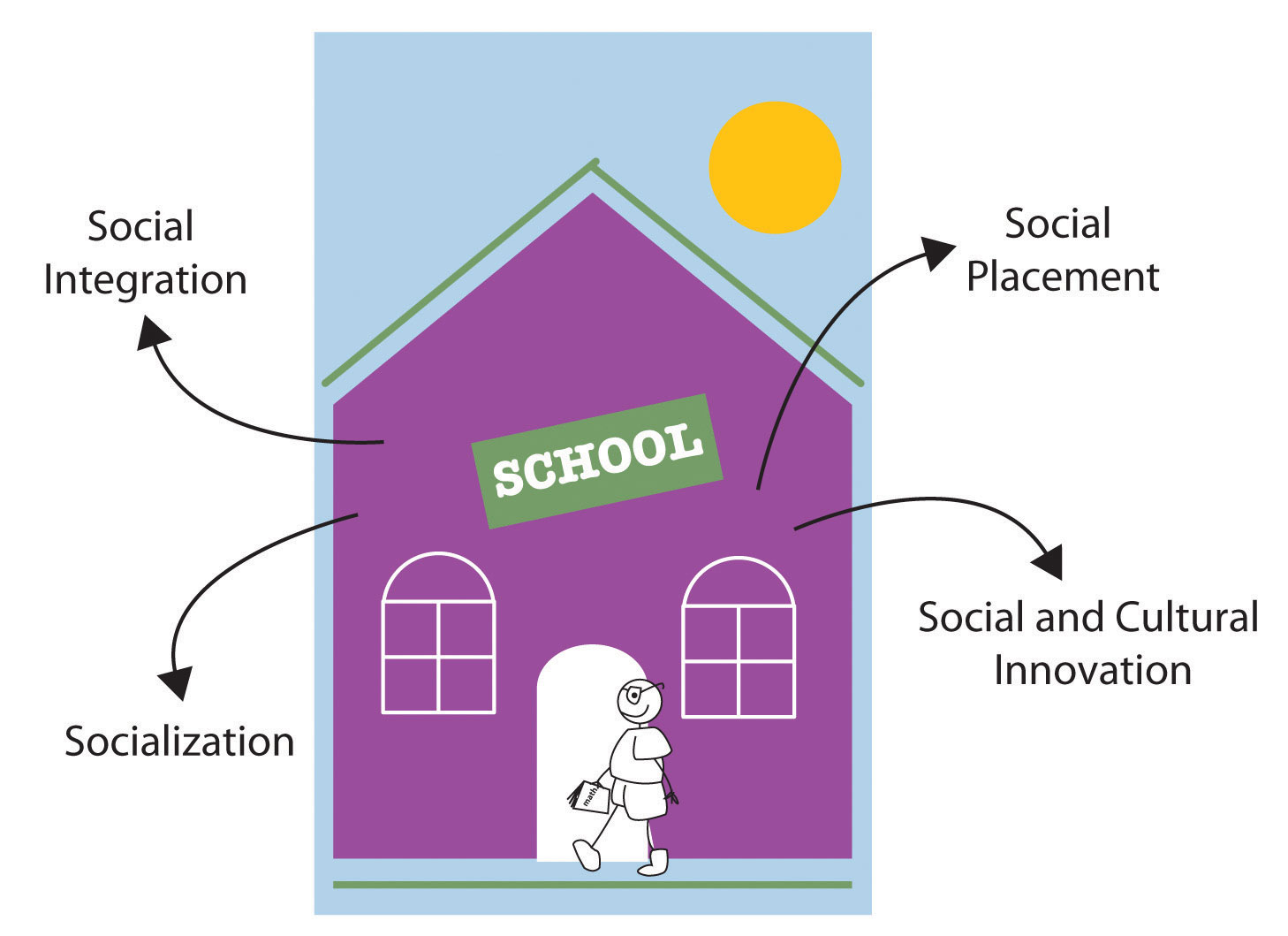

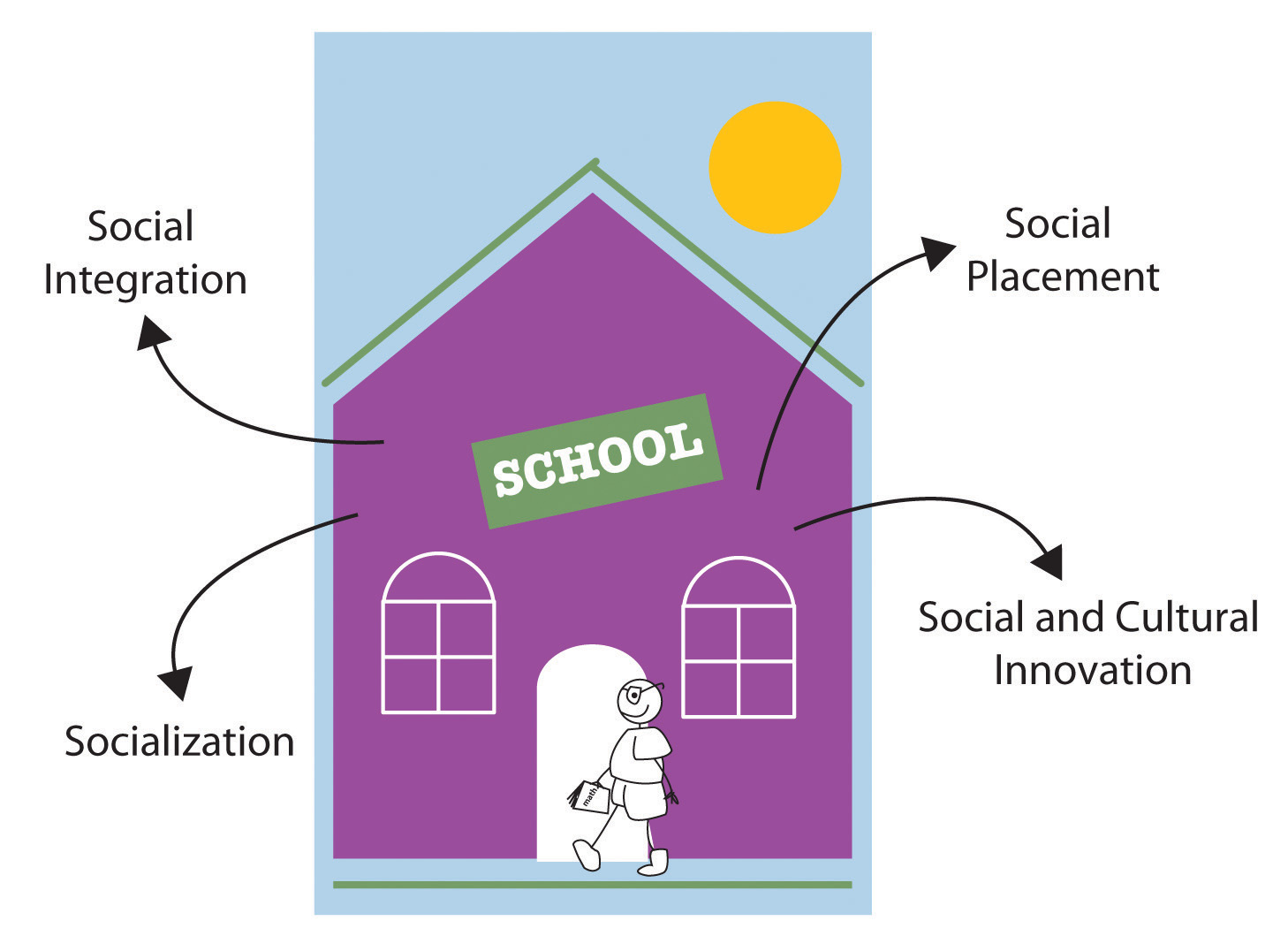

Figure 11.6 The Functions of Education

Schools ideally perform many important functions in modern society. These include socialization, social integration, social placement, and social and cultural innovation.

Education also involves several latent functions, functions that are by-products of going to school and receiving an education rather than a direct effect of the education itself. One of these is child care : Once a child starts kindergarten and then first grade, for several hours a day the child is taken care of for free. The establishment of peer relationships is another latent function of schooling. Most of us met many of our friends while we were in school at whatever grade level, and some of those friendships endure the rest of our lives. A final latent function of education is that it keeps millions of high school students out of the full-time labor force . This fact keeps the unemployment rate lower than it would be if they were in the labor force.

Because education serves so many manifest and latent functions for society, problems in schooling ultimately harm society. For education to serve its many functions, various kinds of reforms are needed to make our schools and the process of education as effective as possible.

Education and Inequality

Conflict theory does not dispute the functions just described. However, it does give some of them a different slant by emphasizing how education also perpetuates social inequality (Ballantine & Hammack, 2012). Ballantine, J. H., & Hammack, F. M. (2012). The sociology of education: A systematic analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. One example of this process involves the function of social placement. When most schools begin tracking their students in grade school, the students thought by their teachers to be bright are placed in the faster tracks (especially in reading and arithmetic), while the slower students are placed in the slower tracks; in high school, three common tracks are the college track, vocational track, and general track.

Such tracking does have its advantages; it helps ensure that bright students learn as much as their abilities allow them, and it helps ensure that slower students are not taught over their heads. But conflict theorists say that tracking also helps perpetuate social inequality by locking students into faster and lower tracks. Worse yet, several studies show that students’ social class and race and ethnicity affect the track into which they are placed, even though their intellectual abilities and potential should be the only things that matter: White, middle-class students are more likely to be tracked “up,” while poorer students and students of color are more likely to be tracked “down.” Once they are tracked, students learn more if they are tracked up and less if they are tracked down. The latter tend to lose self-esteem and begin to think they have little academic ability and thus do worse in school because they were tracked down. In this way, tracking is thought to be good for those tracked up and bad for those tracked down. Conflict theorists thus say that tracking perpetuates social inequality based on social class and race and ethnicity (Ansalone, 2010). Ansalone, G. (2010). Tracking: Educational differentiation or defective strategy. Educational Research Quarterly, 34 (2), 3–17.

Conflict theorists add that standardized tests are culturally biased and thus also help perpetuate social inequality (Grodsky, Warren, & Felts, 2008). Grodsky, E., Warren, J. R., & Felts, E. (2008). Testing and social stratification in American education. Annual Review of Sociology, 34 (1), 385–404. According to this criticism, these tests favor white, middle-class students whose socioeconomic status and other aspects of their backgrounds have afforded them various experiences that help them answer questions on the tests.

A third critique of conflict theory involves the quality of schools. As we will see later in this chapter, US schools differ mightily in their resources, learning conditions, and other aspects, all of which affect how much students can learn in them. Simply put, schools are unequal, and their very inequality helps perpetuate inequality in the larger society. Children going to the worst schools in urban areas face many more obstacles to their learning than those going to well-funded schools in suburban areas. Their lack of learning helps ensure they remain trapped in poverty and its related problems.

In a fourth critique, conflict theorists say that schooling teaches a hidden curriculum A set of values and beliefs learned in school that support the status quo, including the existing social hierarchy. , by which they mean a set of values and beliefs that support the status quo, including the existing social hierarchy (Booher-Jennings, 2008). Booher-Jennings, J. (2008). Learning to label: Socialisation, gender, and the hidden curriculum of high-stakes testing. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 29 , 149–160. Although no one plots this behind closed doors, our schoolchildren learn patriotic values and respect for authority from the books they read and from various classroom activities.

A final critique is historical and concerns the rise of free, compulsory education during the nineteenth century (Cole, 2008). Cole, M. (2008). Marxism and educational theory: Origins and issues. New York, NY: Routledge. Because compulsory schooling began in part to prevent immigrants’ values from corrupting “American” values, conflict theorists see its origins as smacking of ethnocentrism (the belief that one’s own group is superior to another group). They also criticize its intention to teach workers the skills they needed for the new industrial economy. Because most workers were very poor in this economy, these critics say, compulsory education served the interests of the upper/capitalist class much more than it served the interests of workers.

Symbolic Interactionism and School Behavior

Symbolic interactionist studies of education examine social interaction in the classroom, on the playground, and in other school venues. These studies help us understand what happens in the schools themselves, but they also help us understand how what occurs in school is relevant for the larger society. Some studies, for example, show how children’s playground activities reinforce gender-role socialization. Girls tend to play more cooperative games, while boys play more competitive sports (Thorne, 1993) Thorne, B. (1993). Gender play: Girls and boys in school . New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. (see Chapter 4 "Gender Inequality" ).

Applying Social Research

Assessing the Impact of Small Class Size

Do elementary school students fare better if their classes have fewer students rather than more students? It is not easy to answer this important question, because any differences found between students in small classes and those in larger classes might not necessarily reflect class size. Rather, they may reflect other factors. For example, perhaps the most motivated, educated parents ask that their child be placed in a smaller class and that their school goes along with this request. Perhaps teachers with more experience favor smaller classes and are able to have their principals assign them to these classes, while new teachers are assigned larger classes. These and other possibilities mean that any differences found between the two class sizes might reflect the qualities and skills of students and/or teachers in these classes, and not class size itself.

For this reason, the ideal study of class size would involve random assignment of both students and teachers to classes of different size. (Recall that Chapter 1 "Understanding Social Problems" discusses the benefits of random assignment.) Fortunately, a notable study of this type exists.

The study, named Project STAR (Student/Teacher Achievement Ratio), began in Tennessee in 1985 and involved 79 public schools and 11,600 students and 1,330 teachers who were all randomly assigned to either a smaller class (13–17 students) or a larger class (22–25 students). The random assignment began when the students entered kindergarten and lasted through third grade; in fourth grade, the experiment ended, and all the students were placed into the larger class size. The students are now in their early thirties, and many aspects of their educational and personal lives have been followed since the study began.

Some of the more notable findings of this multiyear study include the following:

- While in grades K–3, students in the smaller classes had higher average scores on standardized tests.

- Students who had been in the smaller classes continued to have higher average test scores in grades 4–7.

- Students who had been in the smaller classes were more likely to complete high school and also to attend college.

- Students who had been in the smaller classes were less likely to be arrested during adolescence.

- Students who had been in the smaller classes were more likely in their twenties to be married and to live in wealthier neighborhoods.

- White girls who had been in the smaller classes were less likely to have a teenage birth than white girls who had been in the larger classes.

Why did small class size have these benefits? Two reasons seem likely. First, in a smaller class, there are fewer students to disrupt the class by talking, fighting, or otherwise taking up the teacher’s time. More learning can thus occur in smaller classes. Second, kindergarten teachers are better able to teach noncognitive skills (cooperating, listening, sitting still) in smaller classes, and these skills can have an impact many years later.

Regardless of the reasons, it was the experimental design of Project STAR that enabled its findings to be attributed to class size rather than to other factors. Because small class size does seem to help in many ways, the United States should try to reduce class size in order to improve student performance and later life outcomes.

Sources: Chetty et al., 2011; Schanzenbach, 2006 Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N., Hilger, N., Saez, E., Schanzenbach, D. W., & Yagan, D. (2011). How does your kindergarten classroom affect your earnings? Evidence from Project STAR. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126 , 1593–1660; Schanzenbach, D. W. (2006). What have researchers learned from Project STAR? (Harris School Working Paper—Series 06.06).

Another body of research shows that teachers’ views about students can affect how much the students learn. When teachers think students are smart, they tend to spend more time with these students, to call on them, and to praise them when they give the right answer. Not surprisingly, these students learn more because of their teachers’ behavior. But when teachers think students are less bright, they tend to spend less time with these students and to act in a way that leads them to learn less. Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson (1968) Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom . New York, NY: Holt. conducted a classic study of this phenomenon. They tested a group of students at the beginning of the school year and told their teachers which students were bright and which were not. They then tested the students again at the end of the school year. Not surprisingly, the bright students had learned more during the year than the less bright ones. But it turned out that the researchers had randomly decided which students would be designated bright and less bright. Because the “bright” students learned more during the school year without actually being brighter at the beginning, their teachers’ behavior must have been the reason. In fact, their teachers did spend more time with them and praised them more often than was true for the “less bright” students. This process helps us understand why tracking is bad for the students tracked down.

Other research in the symbolic interactionist tradition focuses on how teachers treat girls and boys. Many studies find that teachers call on and praise boys more often (Jones & Dindia, 2004). Jones, S. M., & Dindia, K. (2004). A meta-analystic perspective on sex equity in the classroom. Review of Educational Research, 74 , 443–471. Teachers do not do this consciously, but their behavior nonetheless sends an implicit message to girls that math and science are not for them and that they are not suited to do well in these subjects. This body of research has stimulated efforts to educate teachers about the ways in which they may unwittingly send these messages and about strategies they could use to promote greater interest and achievement by girls in math and science (Battey, Kafai, Nixon, & Kao, 2007). Battey, D., Kafai, Y., Nixon, A. S., & Kao, L. L. (2007). Professional development for teachers on gender equity in the sciences: Initiating the conversation. Teachers College Record, 109 (1), 221–243.

Key Takeaways

- According to the functional perspective, education helps socialize children and prepare them for their eventual entrance into the larger society as adults.

- The conflict perspective emphasizes that education reinforces inequality in the larger society.

- The symbolic interactionist perspective focuses on social interaction in the classroom, on school playgrounds, and at other school-related venues. Social interaction contributes to gender-role socialization, and teachers’ expectations may affect their students’ performance.

For Your Review

- Review how the functionalist, conflict, and symbolic interactionist perspectives understand and explain education. Which of these three approaches do you most prefer? Why?

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

66 11.2 Sociological Perspectives on Education

Learning objectives.

- List the major functions of education.

- Explain the problems that conflict theory sees in education.

- Describe how symbolic interactionism understands education.

The major sociological perspectives on education fall nicely into the functional, conflict, and symbolic interactionist approaches (Ballantine & Hammack, 2012). Table 11.1 “Theory Snapshot” summarizes what these approaches say.

Table 11.1 Theory Snapshot

The Functions of Education

Functional theory stresses the functions that education serves in fulfilling a society’s various needs. Perhaps the most important function of education is socialization . If children are to learn the norms, values, and skills they need to function in society, then education is a primary vehicle for such learning. Schools teach the three Rs (reading, ’riting, ’rithmetic), as we all know, but they also teach many of the society’s norms and values. In the United States, these norms and values include respect for authority, patriotism (remember the Pledge of Allegiance?), punctuality, and competition (for grades and sports victories).

A second function of education is social integration . For a society to work, functionalists say, people must subscribe to a common set of beliefs and values. As we saw, the development of such common views was a goal of the system of free, compulsory education that developed in the nineteenth century. Thousands of immigrant children in the United States today are learning English, US history, and other subjects that help prepare them for the workforce and integrate them into American life.

A third function of education is social placement . Beginning in grade school, students are identified by teachers and other school officials either as bright and motivated or as less bright and even educationally challenged. Depending on how they are identified, children are taught at the level that is thought to suit them best. In this way, they are presumably prepared for their later station in life. Whether this process works as well as it should is an important issue, and we explore it further when we discuss school tracking later in this chapter.

Social and cultural innovation is a fourth function of education. Our scientists cannot make important scientific discoveries and our artists and thinkers cannot come up with great works of art, poetry, and prose unless they have first been educated in the many subjects they need to know for their chosen path.

Figure 11.6 The Functions of Education

Schools ideally perform many important functions in modern society. These include socialization, social integration, social placement, and social and cultural innovation.

Education also involves several latent functions, functions that are by-products of going to school and receiving an education rather than a direct effect of the education itself. One of these is child care : Once a child starts kindergarten and then first grade, for several hours a day the child is taken care of for free. The establishment of peer relationships is another latent function of schooling. Most of us met many of our friends while we were in school at whatever grade level, and some of those friendships endure the rest of our lives. A final latent function of education is that it keeps millions of high school students out of the full-time labor force . This fact keeps the unemployment rate lower than it would be if they were in the labor force.

Because education serves so many manifest and latent functions for society, problems in schooling ultimately harm society. For education to serve its many functions, various kinds of reforms are needed to make our schools and the process of education as effective as possible.

Education and Inequality

Conflict theory does not dispute the functions just described. However, it does give some of them a different slant by emphasizing how education also perpetuates social inequality (Ballantine & Hammack, 2012). One example of this process involves the function of social placement. When most schools begin tracking their students in grade school, the students thought by their teachers to be bright are placed in the faster tracks (especially in reading and arithmetic), while the slower students are placed in the slower tracks; in high school, three common tracks are the college track, vocational track, and general track.

Such tracking does have its advantages; it helps ensure that bright students learn as much as their abilities allow them, and it helps ensure that slower students are not taught over their heads. But conflict theorists say that tracking also helps perpetuate social inequality by locking students into faster and lower tracks. Worse yet, several studies show that students’ social class and race and ethnicity affect the track into which they are placed, even though their intellectual abilities and potential should be the only things that matter: White, middle-class students are more likely to be tracked “up,” while poorer students and students of color are more likely to be tracked “down.” Once they are tracked, students learn more if they are tracked up and less if they are tracked down. The latter tend to lose self-esteem and begin to think they have little academic ability and thus do worse in school because they were tracked down. In this way, tracking is thought to be good for those tracked up and bad for those tracked down. Conflict theorists thus say that tracking perpetuates social inequality based on social class and race and ethnicity (Ansalone, 2010).

Conflict theorists add that standardized tests are culturally biased and thus also help perpetuate social inequality (Grodsky, Warren, & Felts, 2008). According to this criticism, these tests favor white, middle-class students whose socioeconomic status and other aspects of their backgrounds have afforded them various experiences that help them answer questions on the tests.

A third critique of conflict theory involves the quality of schools. As we will see later in this chapter, US schools differ mightily in their resources, learning conditions, and other aspects, all of which affect how much students can learn in them. Simply put, schools are unequal, and their very inequality helps perpetuate inequality in the larger society. Children going to the worst schools in urban areas face many more obstacles to their learning than those going to well-funded schools in suburban areas. Their lack of learning helps ensure they remain trapped in poverty and its related problems.

In a fourth critique, conflict theorists say that schooling teaches a hidden curriculum , by which they mean a set of values and beliefs that support the status quo, including the existing social hierarchy (Booher-Jennings, 2008). Although no one plots this behind closed doors, our schoolchildren learn patriotic values and respect for authority from the books they read and from various classroom activities.

A final critique is historical and concerns the rise of free, compulsory education during the nineteenth century (Cole, 2008). Because compulsory schooling began in part to prevent immigrants’ values from corrupting “American” values, conflict theorists see its origins as smacking of ethnocentrism (the belief that one’s own group is superior to another group). They also criticize its intention to teach workers the skills they needed for the new industrial economy. Because most workers were very poor in this economy, these critics say, compulsory education served the interests of the upper/capitalist class much more than it served the interests of workers.

Symbolic Interactionism and School Behavior

Symbolic interactionist studies of education examine social interaction in the classroom, on the playground, and in other school venues. These studies help us understand what happens in the schools themselves, but they also help us understand how what occurs in school is relevant for the larger society. Some studies, for example, show how children’s playground activities reinforce gender-role socialization. Girls tend to play more cooperative games, while boys play more competitive sports (Thorne, 1993) (see Chapter 4 “Gender Inequality” ).

Applying Social Research

Assessing the Impact of Small Class Size

Do elementary school students fare better if their classes have fewer students rather than more students? It is not easy to answer this important question, because any differences found between students in small classes and those in larger classes might not necessarily reflect class size. Rather, they may reflect other factors. For example, perhaps the most motivated, educated parents ask that their child be placed in a smaller class and that their school goes along with this request. Perhaps teachers with more experience favor smaller classes and are able to have their principals assign them to these classes, while new teachers are assigned larger classes. These and other possibilities mean that any differences found between the two class sizes might reflect the qualities and skills of students and/or teachers in these classes, and not class size itself.

For this reason, the ideal study of class size would involve random assignment of both students and teachers to classes of different size. (Recall that Chapter 1 “Understanding Social Problems” discusses the benefits of random assignment.) Fortunately, a notable study of this type exists.

The study, named Project STAR (Student/Teacher Achievement Ratio), began in Tennessee in 1985 and involved 79 public schools and 11,600 students and 1,330 teachers who were all randomly assigned to either a smaller class (13–17 students) or a larger class (22–25 students). The random assignment began when the students entered kindergarten and lasted through third grade; in fourth grade, the experiment ended, and all the students were placed into the larger class size. The students are now in their early thirties, and many aspects of their educational and personal lives have been followed since the study began.

Some of the more notable findings of this multiyear study include the following:

- While in grades K–3, students in the smaller classes had higher average scores on standardized tests.

- Students who had been in the smaller classes continued to have higher average test scores in grades 4–7.

- Students who had been in the smaller classes were more likely to complete high school and also to attend college.

- Students who had been in the smaller classes were less likely to be arrested during adolescence.

- Students who had been in the smaller classes were more likely in their twenties to be married and to live in wealthier neighborhoods.

- White girls who had been in the smaller classes were less likely to have a teenage birth than white girls who had been in the larger classes.

Why did small class size have these benefits? Two reasons seem likely. First, in a smaller class, there are fewer students to disrupt the class by talking, fighting, or otherwise taking up the teacher’s time. More learning can thus occur in smaller classes. Second, kindergarten teachers are better able to teach noncognitive skills (cooperating, listening, sitting still) in smaller classes, and these skills can have an impact many years later.

Regardless of the reasons, it was the experimental design of Project STAR that enabled its findings to be attributed to class size rather than to other factors. Because small class size does seem to help in many ways, the United States should try to reduce class size in order to improve student performance and later life outcomes.

Sources: Chetty et al., 2011; Schanzenbach, 2006

Research guided by the symbolic interactionist perspective suggests that teachers’ expectations may influence how much their students learn. When teachers expect little of their students, their students tend to learn less.

ijiwaru jimbo – Pre-school colour pack – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Another body of research shows that teachers’ views about students can affect how much the students learn. When teachers think students are smart, they tend to spend more time with these students, to call on them, and to praise them when they give the right answer. Not surprisingly, these students learn more because of their teachers’ behavior. But when teachers think students are less bright, they tend to spend less time with these students and to act in a way that leads them to learn less. Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson (1968) conducted a classic study of this phenomenon. They tested a group of students at the beginning of the school year and told their teachers which students were bright and which were not. They then tested the students again at the end of the school year. Not surprisingly, the bright students had learned more during the year than the less bright ones. But it turned out that the researchers had randomly decided which students would be designated bright and less bright. Because the “bright” students learned more during the school year without actually being brighter at the beginning, their teachers’ behavior must have been the reason. In fact, their teachers did spend more time with them and praised them more often than was true for the “less bright” students. This process helps us understand why tracking is bad for the students tracked down.

Other research in the symbolic interactionist tradition focuses on how teachers treat girls and boys. Many studies find that teachers call on and praise boys more often (Jones & Dindia, 2004). Teachers do not do this consciously, but their behavior nonetheless sends an implicit message to girls that math and science are not for them and that they are not suited to do well in these subjects. This body of research has stimulated efforts to educate teachers about the ways in which they may unwittingly send these messages and about strategies they could use to promote greater interest and achievement by girls in math and science (Battey, Kafai, Nixon, & Kao, 2007).

Key Takeaways

- According to the functional perspective, education helps socialize children and prepare them for their eventual entrance into the larger society as adults.

- The conflict perspective emphasizes that education reinforces inequality in the larger society.

- The symbolic interactionist perspective focuses on social interaction in the classroom, on school playgrounds, and at other school-related venues. Social interaction contributes to gender-role socialization, and teachers’ expectations may affect their students’ performance.

For Your Review

- Review how the functionalist, conflict, and symbolic interactionist perspectives understand and explain education. Which of these three approaches do you most prefer? Why?

Ansalone, G. (2010). Tracking: Educational differentiation or defective strategy. Educational Research Quarterly, 34 (2), 3–17.

Ballantine, J. H., & Hammack, F. M. (2012). The sociology of education: A systematic analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Battey, D., Kafai, Y., Nixon, A. S., & Kao, L. L. (2007). Professional development for teachers on gender equity in the sciences: Initiating the conversation. Teachers College Record, 109 (1), 221–243.

Booher-Jennings, J. (2008). Learning to label: Socialisation, gender, and the hidden curriculum of high-stakes testing. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 29 , 149–160.

Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N., Hilger, N., Saez, E., Schanzenbach, D. W., & Yagan, D. (2011). How does your kindergarten classroom affect your earnings? Evidence from Project STAR. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126 , 1593–1660.

Cole, M. (2008). Marxism and educational theory: Origins and issues. New York, NY: Routledge.

Grodsky, E., Warren, J. R., & Felts, E. (2008). Testing and social stratification in American education. Annual Review of Sociology, 34 (1), 385–404.

Jones, S. M., & Dindia, K. (2004). A meta-analystic perspective on sex equity in the classroom. Review of Educational Research, 74 , 443–471.

Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom . New York, NY: Holt.

Schanzenbach, D. W. (2006). What have researchers learned from Project STAR? (Harris School Working Paper—Series 06.06).

Thorne, B. (1993). Gender play: Girls and boys in school . New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Social Problems: Continuity and Change Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

IResearchNet

Academic Writing Services

Education in society.

Changes in developed economies and societies stemming from the Industrial Revolution have shifted responsibilities for the education of young people from the family and community to schools. Schools are now a major institution, educating the vast majority of children and youth in the developed world and functioning as a primary engine of change in developing countries. Although education brings about changes in society as a whole as well as in individuals, schools are also influenced by larger social forces. Sociological theories address these central roles that schools play in society from differing perspectives.

The functionalist paradigm emphasizes the role that education plays for society. Emile Durkheim, one of the founders of sociology, was among the first educational researchers to focus on the function schools serve for the larger society. Durkheim (1961) argued that the main goal of education was to socialize individuals so that they share values with the larger society. Ensuring that all students received the same moral education allowed for a more integrated society with less social conflict about wrong behaviors or attitudes. A second important functionalist perspective on education developed in economics through research on human capital (Schultz 1961). The human capital perspective describes education as a set of investments that increase individuals’ knowledge and skills, which in turn improves national labor productivity and economic growth. Education then becomes an important tool for societies to increase the efficiency and size of their economy.

While the functionalist perspective emphasizes the role of education for society as a whole, the conflict paradigm focuses on divisions within society that education maintains or rein forces. Max Weber (2000) was one of the first to argue that education serves dual and potentially conflicting functions for society. First, schools can be an equalizing institution where individuals, regardless of their social status, can gain access to high status jobs through their own talent and hard work. Second, schools can rein force existing status hierarchies by limiting opportunities to individuals from high status backgrounds. In other words, Weber recognized schools’ potential to either facilitate or block social mobility. Weber’s incorporation of the notion of social status into the function of schools in society was extremely influential in shaping sociological research on education. Randall Collins (1979), Samuel Bowles, Herbert Gintis, and others furthered Weber’s ideas on status attainment by arguing that schools socialize individuals to accept their place in an unjust, capitalist society. This work shifted the emphasis found in human capital theory away from schools as providers of skills and training to schools as providers of hollow credentials that are rewarded in the labor market. Critically, these credentials do not represent higher levels of skills, but simply serve as status markers that employers use to sort workers into low and high prestige occupations.

Both historically and when comparing countries today, the structure of a country’s educational system is closely linked to its economic and political history. Developed countries are generally characterized by a history of relatively steady economic growth, a stable political system, and freedom from the devastation of war. This common context enables developed countries to form a cohesive formal schooling system that serves all children until at least the age of 15 or 16. In recent decades, developed nations have incorporated the ideals of equality of educational opportunity and providing opportunities to children from disadvantaged backgrounds into their goals for educational policy.

Though all developed nations provide universal education and many are motivated by similar ideals, the structure of schooling can vary drastically from developed country to developed country (for an overview, see Brint 1998). In Japan, France, and Sweden, the school system is run by a central governmental ministry of education that ensures standardized curricula and funding. Other countries, such as Germany, Canada, and the US, are more decentralized and allow local or regional governments to maintain control over public education. Additionally, the school systems in these nations vary in how they structure opportunities to learn and earn credentials. In his classic article, Ralph Turner (1960) contrasted the English and US school systems, characterizing the former as a “sponsored” system, in which talent is identified in the early years and nurtured in a stratified system. The US system, on the other hand, is a “contest” system, consisting of a series of contests in which all students compete on a level playing field. Though “sponsored” and “contest” systems are ”ideal types,” most developed nations’ school systems reflect aspects of sponsored or contest systems.

In the developing world, many countries have been independent from colonizing powers for approximately only 50 years and do not have the same history of political stability, economic security, and times of peace that privilege developed countries. These instabilities (along with problems related to poverty) affect the ability of developing countries to provide and prioritize universal education. In many developing countries, the school system is inherited in large part from former colonizers and is heavily shaped by the policies of the World Bank. The World Bank promotes a model of schooling that emphasizes primary schools, private spending, balances equity and efficiency, and discourages vocational education. Though the structure and experience World Bank policies provide can improve schooling priorities in developing nations, they sometimes do not recognize that factors unique to a particular country may require modifications. A central question concerning the role of education in developing nations concerns how important education systems are to economic growth. Much of the research on education in developing nations examines this question and generally finds that having a disciplined and educated labor force is a positive and important step in economic development.

Though commonalities in the structure of schooling exist across countries in the developed and developing world, each country is generally unique in the development of its particular educational system. Systems of education not only reflect national values and attitudes, they also play a major role in shaping national culture and social status hierarchy. In the US, the idea of public schooling – or the common school – developed in the early nineteenth century as a response to political and economic shifts in American society (see Parkerson & Parkerson 2001 for a history). Prior to common schooling, the majority of Americans were educated by their families, and only children from wealthier families could afford formal schooling. As the US moved away from a barter and trade economy toward markets where goods were exchanged for cash, white Protestant Americans from the middle and working classes recognized that the fragmented and informal system of schooling was no longer adequate preparation for their children to be competitive in the market driven economy. This realization led these Americans to demand that a quality primary education be made available to their children. The ideal of equality emphasized during the American Revolution meant that there was already growing political support among the Protestant political elite for the idea of public education for white children.

The end result of these forces was the development of the common school. Common schools had two main goals: first, to provide knowledge and skills necessary to being an active member of economic and social life; and second, to create Americans who value the same things – namely, patriotism, achievement, competition, and Protestant moral and religious values. Significantly, these goals were important both to individuals trying to make it in the new economic and social order and to the success of solidifying the young United States into a coherent nation. Religious diversity was not tolerated in the nascent nation, and Catholic immigrants were often seen as threats to the dominant Protestant way of life. Therefore, though common schools were open to all white Americans, the emphasis on Protestant values (which went hand in hand with anti-Catholic attitudes) alienated many Catholics. This religious tension eventually led Catholics to pursue alternative schooling and resulted in the development of Catholic private schools.

Though common schools provided more equitable access to education than the previous informal system, these schools still reflected the values of the ruling elite – white Anglo Saxon Protestants – in US society. In addition to appreciating Protestant values over those of other religions, educating white boys was generally seen as more important than educating white girls as white boys were more likely to benefit from their education upon entry into the formal labor market. Furthermore, African Americans, freed or enslaved, were almost categorically excluded from common schools in the early 1800s as the flawed ”ideal of equality” applied only to white Americans.

Despite the development of the common school, elite white Protestant Americans were able to maintain educational superiority by opting out of the common school system. The elite private and boarding school system began before the American Revolution and flourished during the nineteenth century (at the same time that the common school system was expanding). Though the growing public education system diminished the percentage of secondary students in private schools, private schools maintained an exclusivity that appealed to elite parents eager to pass on status and advantage to their children. In Preparing for Power: America’s Elite Boarding Schools (1985), authors Cookson and Persell explore the admissions process and the demographic characteristics of ”the chosen ones,” America’s most privileged students. Historically, these elite schools tended to have a homogeneous student body in terms of family background, religion, and race, and admission was based not on openly stated academic requirements but on a complicated balance of merit, family wealth, social standing, and an individual’s ability to fit the school’s ideal. Thus, the presentation of self as a person of status – someone with ambition, confidence, and poise – was just as important as academic capacities to gaining access to America’s most elite secondary education. Though these private schools continue to promote an elite social class identity, currently they also face pressure to diversify the racial composition of their student bodies.

While elite private schools have historically allowed privileged Americans to opt out of public schooling, religious schools have offered an important private alternative to non-elite, and sometimes marginalized, Americans throughout the history of the US. Catholic schools were a part of Colonial America and are among some of the oldest educational institutions in the US. In contrast to elite private schools, religious schools had a moral purpose of teaching religious beliefs and producing religious leaders. Beginning in the 1800s, Catholic schools provided an alternative to the public school where children read the Protestant version of the Bible. Today, Catholic schools serve a more diverse student population in terms of race, social class, and religious beliefs. Catholic schools today are known for providing good opportunities to learn and prepare for college (Bryk et al. 1993). Critics suggest that Catholic schools select more promising students, an option not available to public schools.

Though research on elite and Catholic private schools suggests that access to a private versus public education affects students’ academic opportunities, inequalities between schools within the public sector have long plagued the American educational system, with serious implications for children with no choice other than public schooling. As mentioned previously, the common school system generally excluded African American children until after the end of the Civil War and Reconstruction. Though the end of slavery meant that the common school system finally included African American children, they were generally educated in separate facilities (see Orfield & Eaton 1996 for a history). By 1896, the idea of ”separate but equal” schools was officially sanctioned by the Supreme Court through its decision in Plessy v. Ferguson. Racially segregated schools became the norm across the US, though whether this segregation was by law or by practice varied by state and region. Equitable distribution of resources between racially segregated schools never existed; white schools received substantially more financial and academic support. ”Separate but equal” schools were eventually declared inherently unequal in the Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954), and schools were ordered to desegregate ”with all deliberate speed.”

Though Brown is perhaps one of the most widely celebrated Supreme Court decisions, schools in the US have failed to reflect the ideals of desegregation and educational equality put forth in the ruling. Early research in sociology of education recognized that stratification in educational attainment was related to students’ family background, such as race or ethnicity, rather than simply differences in achievement test scores (e.g., Coleman et al. 1966). These differences were social and had to do with the schools’ social context rather than factors that could be affected by redistribution of funding levels alone. Since the Coleman Report (1966) and its political consequences of busing that shocked the nation, educational researchers and policymakers have struggled to know how to provide equality of educational opportunity within a context of socioeconomic inequality.

Beginning around 1980, sociologists of education turned their attention to stratification systems at work within schools. Secondary schools tend to group students in courses or ”tracks” (such as academic, general, or vocational), and through these groupings schools can either reinforce or disrupt the relationship between family background and attainment. Typically, the high school curriculum is organized into sequences of courses in which subject knowledge gained from one course pre pares a student for the next course. Mobility between sequences is restricted and forms the foundation of a stratification system for adolescents. Furthermore, schools tend to provide more resources, such as higher quality instruction, to students in higher level courses, which can have serious consequences for low ability students (Hallinan 1994). The result is that students’ course taking patterns follow a trajectory or sequence of courses over the years of high school in which mobility between course sequences is unusual. This is especially true in mathematics, where mobility into the elite college preparatory classes is nearly impossible after the sequence has begun. Students’ placement in these sequences explains much of why family background is linked to students’ attainment and is strongly related to a variety of

outcomes that indicate students’ basic life chances.

Research on stratification within schools further confirmed the results of Coleman’s earlier analysis on equity in education – schools are more effective at educating students from privileged family backgrounds. Because schools have been idealized as a great equalizing force, understanding why family background is linked strongly to education became the next important goal of sociology of education.

Annette Lareau (1987), building on Pierre Bourdieu’s (1973) idea of cultural capital, offered one explanation of how parents transmit advantages to their children when she found that parents interacted with teachers and schools very differently depending on their social class backgrounds. In addition to conditioning how parents interact with the school, parents’ cultural capital also influences how they socialize their children. Lareau describes middle class parents’ childrearing strategies as ”concerted cultivation” or active fostering of children’s growth through adult organized activities (e.g., soccer, music lessons) and through encouraging critical and original thinking. Working class and poor parents, on the other hand, support their children’s ”natural growth” by providing the conditions necessary for their child’s development, but leaving structure of leisure activities to the children. These different styles have implications for students’ abilities to take advantage of opportunities in schools.

Coleman’s concept of social capital articulated another way that families transmit advantages to their children. In parenting, social capital refers to ”the norms, the social networks, and the relationships between adults and children that are of value for the child’s growing up” and can exist within families and communities (Coleman 1987: 334). Social capital within families taps how close parents and children are and how closely parents are able to monitor their child’s development. For example, Coleman (1988) found that a higher percentage of children from single parent families (who have less social capital in the home) drop out during high school than children from intact families. Social capital in communities is also important, as Coleman et al. (1982) demonstrated: students in Catholic high schools were less likely to drop out compared to their peers in other private and public schools, not because of school related differences (such as quality curriculum), but rather because of the close knit adult relationships surrounding Catholic schools. The cohesive Catholic community allowed adults to better transmit norms about staying in school to teenagers.