Pioneering Photographs of Gay Life in the 1960s

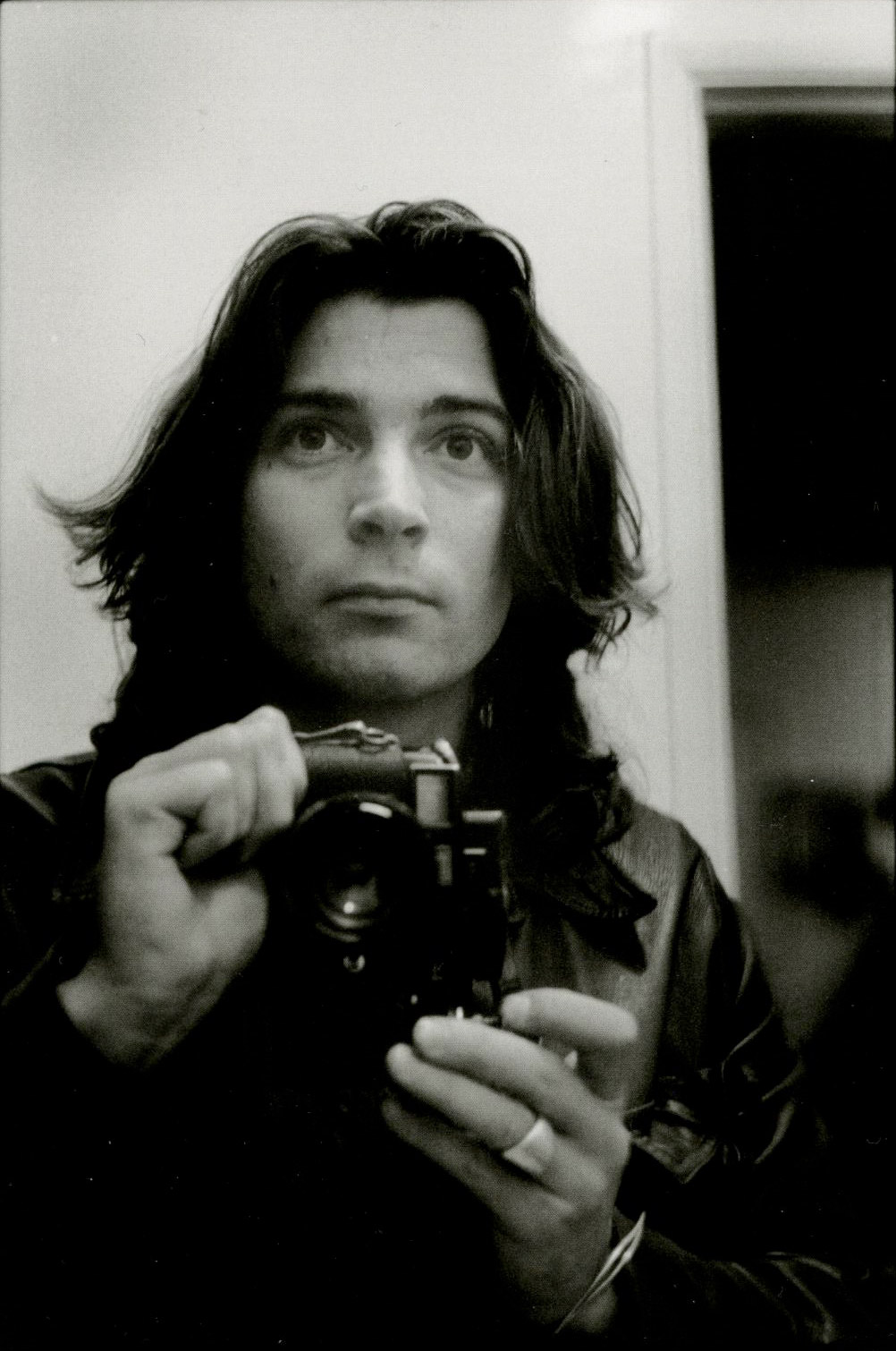

“I was 19, vulnerable, young and putting my own identity together,” says photographer Anthony Friedkin when reflecting on his first project, The Gay Essay , which documents gay culture in Los Angeles and San Francisco between 1969-1972. What started, as a self-assigned project for a young photographer growing up in Hollywood has now become one of the most authentic portraits of gay life in America from this period.

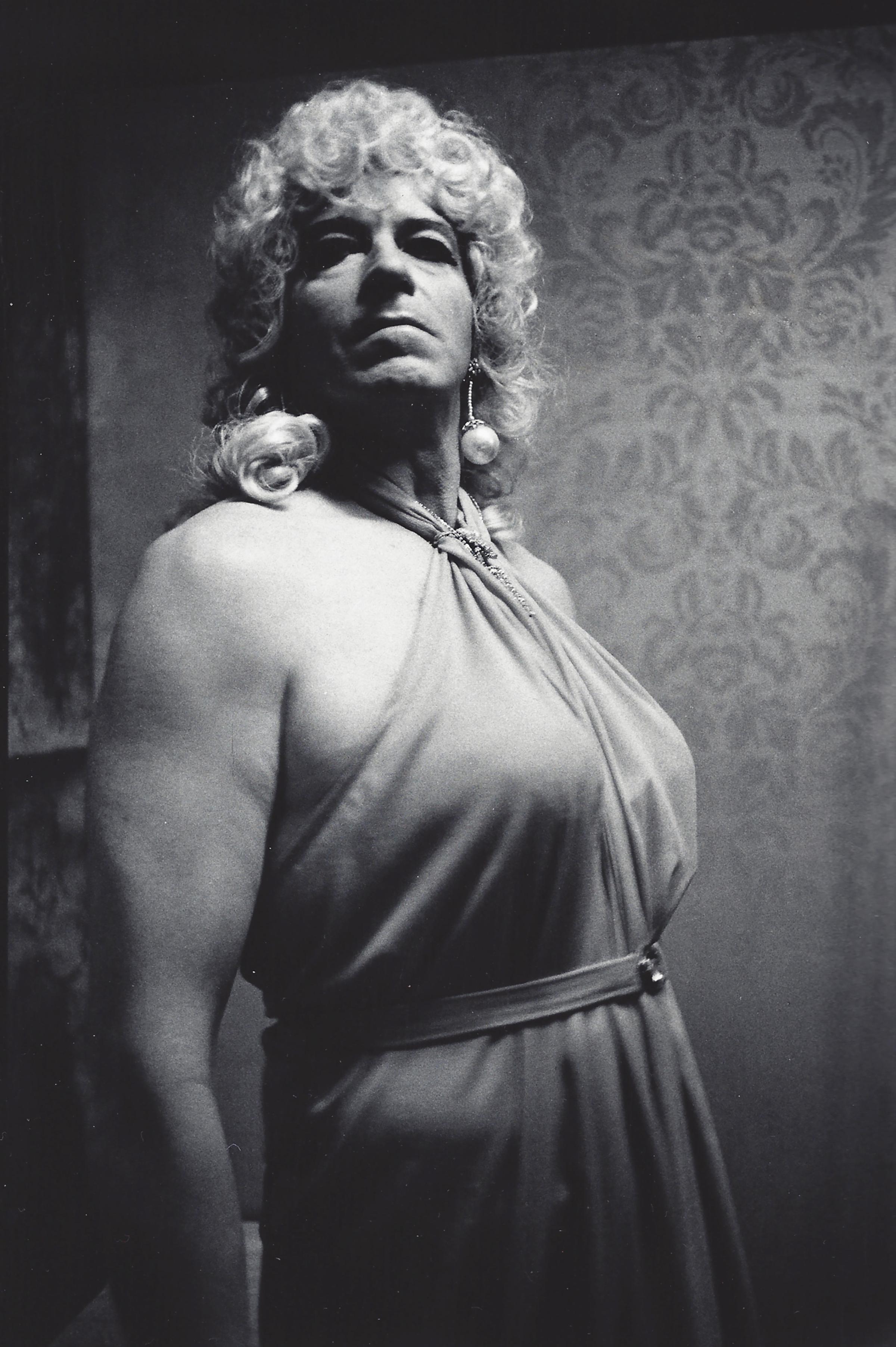

In 1969, the same year as the Stonewall riots in New York City, a gay cultural revolution was growing in America. At the time, most depictions of gay men and women in mainstream media were found in salacious newspaper and tabloid articles, all of them reported from a murky distance. LIFE’s two-part series Homosexuality in America from 1964, featured dark and shadowy photographs by Bill Eppridge. They capture a dark tension and fear that Friedkin’s work moves past with a tender intimacy.

While growing up in Hollywood, Freidkin’s parents worked in the film industry and had close friends that led full openly gay lives. He saw that world as a “refuge” and a place where gays were “allowed to be themselves” more than in any other place.

But The Gay Essay really began while he explored the Los Angeles Gay Community Services Center where he met Morris Kight and Don Kilhefner, two men who ran the programs there and founded the Gay Liberation Front in Los Angeles in 1969 where they mobilized the community against the LAPD’s harassment of homosexuals. They acted as Freidkin’s guides. “They just helped me all around,” he recalls. “They especially helped me in learning how to listen, and really allowing people’s energy to come to me and through the lens of my camera.”

For Friedkin, the goal was to move past many stereotypes and deepen the representation of gay individuals of all types. “It was more about my desire to create a great set of pictures with a heartfelt determination to honor gay people, respect them and their freedom,” he says. “In The Gay Essay I wanted to celebrate the gays that were living openly,” especially at a time, in the early days of the gay movement, following the Stonewall riots. “It upset me tremendously to see the ways gays were being treated,” he adds. “I had friends that got beat up in bars. I was furious about it. Even now, when I look through the book, it gets very emotional for me.”

All along, Friedkin worked slowly, closely documenting hustlers, teens at Trouper’s Hall, drag performers and the first parades in West Hollywood. He also recorded the violence of vice cops at the time. “I was kind of like a racehorse with blinders on and a Leica around my neck,” he says. “I was just going to do this for me as the way I wanted to do it. In a way I think it was probably good that I had a certain innocence in that way that I didn’t overly academically try to predetermine what it was I might do, or why I should do it. I just wanted to go out and become part of it, and be it. I really, really wanted to come out on the other side of this with a very admirable, important set of photographs.”

As a photographer making work since the age of eight, he admired Henri Cartier-Bresson and developed exercises to try and capture what Cartier-Bresson termed as the “decisive moment”. “I used to pack my ears with wax and cotton and all kinds of stuff so I would go deaf. I would do that so I could just look at the world that was changing and moving around me in the sense of the ‘decisive moment’ and just look for moments amongst people, places, things, light that would strike me strong enough to want to make a photograph of it.” He was drawn to the work of many photographers documenting the social landscape of the 1960s with humanistic intent for change. “I was educated to the worlds of W. Eugene Smith, Robert Frank, Bruce Davidson and Danny Lyon,” he says. “I think by really committing yourself to something and really trying to understand it deeply, than the photographs themselves become more intimate and have more depth to them.”

It took many years for his photographs to be seen. “When I first did this, a lot of the American publications wouldn’t go near it,” he says. “They were afraid they’d lose their advertisers, because of the idea of showing two men kissing each other and showing intimacy toward each other. It was just mind-blowing to them. They were so afraid.”

In 2014, The Gay Essay was first shown in its entirety at the De Young Museum in San Francisco and was published as a book by the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco and Yale University Press.

At a time of when photography’s ability to affect social change is in question, Friedkin’s work shows that taking the slow route and connecting with subjects will usually make the most lasting impression, even 40 years later. Today, as he looks back on his life’s work, Freidkin feels proud. “Everything I love about photography is in the gay essay: the sense of the event, capturing the soul of the people, the journey, the process, the unknowns,” he says. “And then really making sense out of it and putting it together, it gives me great strength actually.”

Anthony Friedkin ‘s The Gay Essay is on view at Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York City until March 4.

Paul Moakley is the Deputy Director of Photography and Visual Enterprise at TIME. Follow him on Twitter .

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Why We're Spending So Much Money Now

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- Breaker Sunny Choi Is Heading to Paris

- Why TV Can’t Stop Making Silly Shows About Lady Journalists

- The Case for Wearing Shoes in the House

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

You May Also Like

- Current Issue

- All Articles

- Best Sellers

- New Releases

- Print and Book Bundles

- Coming Soon

- Limited Editions

- Women Photographers

- Portfolios and Sets

- Women’s History Month

- Back Issues

- Aperture PhotoBook Club

- Aperture Conversations

- Member Events

- Online Resources

- Internships

- Professional Development

- Educational Publications

- Portfolio Prize

- PhotoBook Awards

- Creator Labs Photo Fund

- Connect Council

- Patron Circle

- Annual Fund

- Capital Campaign

- Corporate Opportunities

- Planned Giving

- Vision & Justice Book Series

The Photographers Who Envisioned Queer History and Resistance

An exhibition showcases artists and collectives that built queer image cultures with lasting influence.

Lola Flash, Clit Club Series , ca. 1989–90 Courtesy ART+Positive Archives

On the evening of February 9, 2023, in a standing-room-only presentation for a raucous audience at the LGBT Center in Manhattan, Joan E. Biren (JEB) did something for the first and last time in thirty-nine years: a live performance of her Lesbian Images in Photography: 1850–the present (1979–1985). The Dyke Show , as it is more popularly called, is a slideshow comprised of hundreds of portraits, documentary images, and erotic photography by artists ranging from Alice Austen to Tee Corinne. Images on which to build, 1970s–1990s , an exhibition curated by Ariel Goldberg and currently on view at the Leslie-Lohman Museum in New York includes a digitized version of The Dyke Show and seeks to carry on the ambition, enthusiasm, and intergenerational through lines of JEB’s work.

The exhibition is overwhelming—in the best way—in its six distinct but inextricably connected sections. These include photography by Lola Flash alongside ART+ Positive (a small artist collective dedicated to fighting AIDS phobia); documentary images from the vast archive of artist and educator Diana Solís; a selection of images of African American lesbians from the Lesbian Herstory Archives; snapshots, correspondence, and newsletters that showcase sundry trans networks; and Electric Blanket , a slideshow installation of images related to HIV/AIDS, from portraits of dead loved ones to photo essays to protest slogans and statistics.

Images on which to build , which was originally presented at the 2022 FotoFocus Biennial in Cincinnati, showcases artists and collectives that participated in, and ultimately built, robust trans and queer image cultures with lasting influence. The title card for each section looks and feels like a vintage activist button, reminding us that these projects were never only “art for art’s sake.” And neither is this exhibition. Indeed, in form and content, Goldberg’s mission is in keeping with their predecessors’: the work is offered in the spirit of education, inspiration, and interconnection.

I recently spoke with Goldberg, who exudes passion and purpose. “When I started to approach people, my tenor was one of humility,” they told me. “I never thought I was discovering anyone; I was simply bridging the gaps of historical erasure for all those artists and culture workers who have been ignored by incomplete photographic histories.” The result of their gap-filling is a sort of interstellar vastness as moving as it is galvanizing.

Kerry Manders: What was the impetus for this exhibition?

Ariel Goldberg: The fire—fueled by anger and disbelief—really started in 2015 when I was finishing my book The Estrangement Principle about the label “queer art” and asking: what’s my queer lineage in photography?

I knew it had to be deeper than Robert Mapplethorpe and his Hasselblad. I was starting with how modes of representation are contested in queer history, reading Isaac Julien and Kobena Mercer, thinking about Lyle Ashton Harris and others who were pushing back against an elite white gay male history. I wanted to learn about everything that doesn’t assimilate into the commercial fine art world.

The fire was also ignited when I read Sophie Hackett’s article on The Dyke Show by JEB [Joan E. Biren] in the “Queer” 2015 issue of Aperture . That gave me a concrete example of what we could find if only we looked.

Manders: Your mission was to recover and re-present those artists.

Goldberg: I started this research in part because I wanted to experience the slideshows that I was told I can’t see anymore because they were live events. You can reconstruct historical multimedia projects like The Dyke Show if you are devoted to the long process and move at the speed of trust with the people who made them.

Manders: Can you give us a snapshot of this moment in time on which your exhibition focuses? How do you differentiate it from what came before?

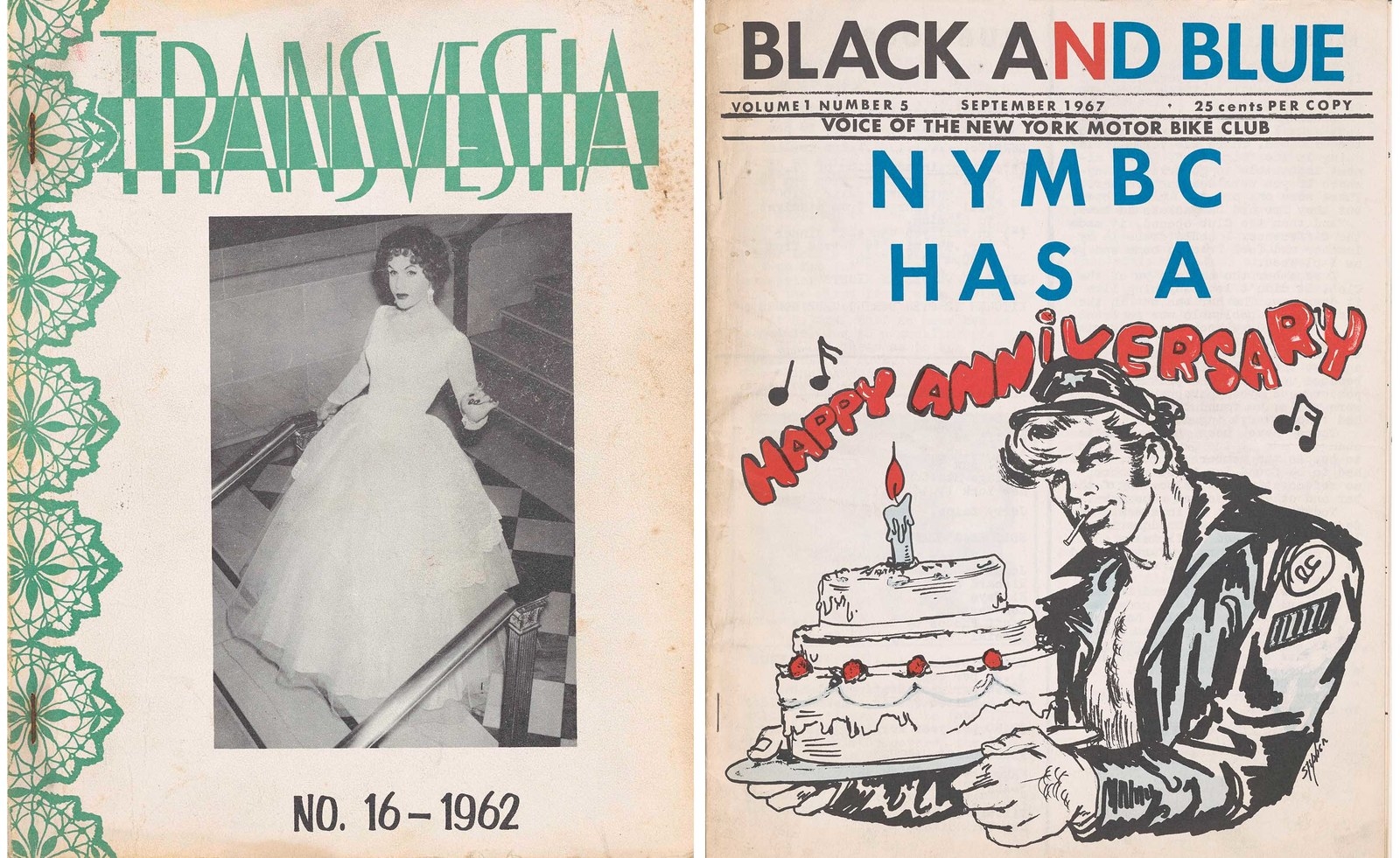

Goldberg: The late ’70s through the late ’90s is a very important moment in trans and queer history because that was when people were coming out and taking that risk in perpetuity: they were not going back in the closet. Right before this, visual records of trans and queer life most often belonged to the state—like arrest records—or were tabloid-y, sensationalized news stories of gender “discovery.” There were criminalizing narratives, or even outright destruction—families destroying personal archives of their queer relatives and even people destroying their own archives for fear of discovery. Even Diane Arbus’s photograph of Stormé DeLarverie was too controversial for Harper’s Bazaar to publish in 1961.

Manders: Where and how did you find these artists? Can you pull back the curtains on the “making of” this exhibition?

Goldberg: It’s multifaceted—there’s no template. My methods depend on the person I’m researching. I do the maximum amount of research I can before engaging in dialogue with an artist or archivist.

The artist Nicole Marroquin, whom I met at a Magnum Foundation event, introduced me to Diana Solís. Ever since, I leave each conversation with Diana—and the many artists and scholars working with them—with more names of people and events to look up, more books and articles to read. I remember the first time I visited Chicago, Nicole said I must read this book Chicanas Movidas , and has since shared articles in English on the Encuentro Feminista Latinoamericana y del Caribe. I still have a lot of learning to do about Chicago social movement history, Chicana, Mexicana histories of the Midwest, and Latin American feminist history if I’m to even fathom Solís’s work.

I apply to get travel funds that are available through archives to go to personal papers. I basically riffle through boxes and boxes of stuff. I try to zoom out and understand who was supporting the photographers’ work. Especially when I was just beginning in JEB’s papers, I started to see repeated names like Tee Corinne and Morgan Gwenwald, and patterns of relationships.

Manders: That’s lovely. You built this exhibition via a network of relationships you found in the archives, which you then translate in your curatorial choices. Interconnection and overlap are key elements of the show.

Goldberg: Yes! When I was working with Diana Solís on the edit of their photographs, I remember getting excited when I saw, in the background of a photograph taken at Mujeres Latinas en Acción, matted photographs on the wall behind the table where a group of women were having a meeting. That group included Diana’s mother, their friend Diane Ávila, and her mother, too. When I asked whose photos were on the wall, Solís responded it was their own work and likely their students’ work from the photography class they were teaching at Mujeres in the late 1970s.

The late ’70s through the late ’90s is a very important moment in trans and queer history because that was when people were coming out and taking that risk in perpetuity: they were not going back in the closet.

This scene is what I am hoping to achieve with the exhibition broadly: creating a space for people to gather and make connections about photography and art’s critical role in organizing across generations. At the openings in Cincinnati and New York, artists and archivists from different cities were getting to meet and appreciate each other through the varied contexts of each other’s work.

The goal was not only about finding material, but also about meeting and connecting people who were not already acquainted. Personally, the ongoing power of this work is the relationships and mentorships I’ve been lucky to cultivate through this process.

Manders: That makes me think of one of the various resonances of the exhibition title—images on which to build relationships . This exhibition seems to be as much about community as it is about art.

Goldberg: Aldo Hernández, one of the organizers of ART+ Positive, reminded me that their work was about communities and collectivities, not about individuals and careers. It was about organizing and doing as much as you could with what little you had. He once said to me, “Oh, we were foam core queens!” And I thought, That kind of sums it up, getting work out there in the ways that were most affordable and easiest to schlep around.

One of my design challenges was to honor the Lesbian Herstory Archives foam core exhibition boards alongside framed archival ink-jet prints. I wanted to show that these practical materials traveled. They’ve been to student centers and volunteer-run archives. That ding on the corner of the foam core board—that wear and tear—is filled with the love of the previous audiences receiving the work.

Related Items

Aperture 229

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Manders: What have you learned in the process of curating this exhibition? What are some crucial takeaways?

Goldberg: The first, most beautiful lesson is that organizing as image makers takes so many different forms.

On the one hand, I’m looking back. I’m doing all this inspiring time travel and celebrating the ways in which our predecessors came together and solved problems. AIDS activists learned the science for treatment—and tirelessly fought for the funding.

On the other hand, I’m thinking in the present tense. We are in a horrifying conservative backlash right now that could really be immobilizing. How can I work and pay my rent, but also bring my skills to all the amazing grassroots organizing happening right now, from prison abolition, defunding the police, affordable housing, canceling student debt, Palestine—all of which are interconnected struggles—to the current onslaught of anti-trans legislation? How can I be of service?

Manders: Now you’re reminding me of the rest of the quotation from which you borrowed your title. In an early review of JEB’s Dyke Show, Carol Seajay claimed these were “Images on which to build a future.” This exhibition, like the image cultures it showcases, is as interested in doing as it is in being.

Goldberg: A lot of trans and queer image making was all about self-determination beyond representation.

For example, Loren Rex Cameron, who was a part of the FTM support group in San Francisco, took pictures of people at different stages of transitioning, and those pictures played a part in educating people about hormones and surgeries. His photographs give us a way to understand how people were using photography to share non-pathologizing transgender medicine and build stronger movements.

The “doing” also speaks to how I wanted to share materials about the joy of gathering! I don’t want to lose that aspect of it. I’ve learned that didactic projects are also about community building and fun . Look at ART+Positive’s Queer Beauty series that Lola Flash photographed: people were spelling the phrase with their naked bodies! This isn’t dry material! Enjoyment in education is part of the work.

Manders: I’m struck by the breadth of this exhibition—the fullness of your curatorial essay and exhibition text and even acknowledgments. We’ve joked about our shared “maximalist tendencies.” It’s not an inability to edit but, instead, a commitment to community, pedagogy, and material history.

Goldberg: Captions are a great metaphor for my work. I felt inspired to begin research for this exhibition while I was working on my photo history book Just Captions: Ethics of Trans and Queer Image Cultures . The caption is my rallying call to learn the names of people who appear in images. To then ask questions about how they were showing up for movements. Beyond the literal, I think of captions as an expandable poetic space, as curiosity for multiple narratives. The show demonstrates how people were supporting and making culture. The columns in the exhibition space are wheat pasted with a single flyer or newsletter page from each of the six sections of the show. The Electric Blanket slideshow call for photographs, Rupert Raj’s Metamorphosis , which was the inspiration for Lou Sullivan’s FTM Newsletter . I want to show how these projects addressed their audiences. Wherever possible, I included a review of the slideshow or exhibit, in part to prove the work was recognized in feminist, trans, and queer communities.

Manders: That makes me curious about the echoes and reverberations of these image cultures. How do we see their influence in the years after? And today?

Goldberg: We see the influence of these image cultures where artists are distributing their work in unconventional, non-institutional ways that also foreground material struggles and support their peers. Publishing hard-to-find materials online, with captions, for example, and making it freely accessible, as Sky Syzygy’s Gender.Network website does.

I am excited by contemporary work that tries to understand, through photographs, the texture of the lives that we’re now celebrating, as opposed to relying on iconicity and fantasies. If we insist on context as part of the work, we can resist the erasure of material struggles that often happens when queer culture is appropriated into mainstream culture. The exhibition highlights inherited strategies of practical resistance, ways to fight the violence and stigma and discrimination that come with a denial of queer and trans life and history. Image makers and archivists in the timeframe I’m looking at realized that they have skills in documenting and preserving queer history and organizing, and needed to put those skills to use.

Manders: Can you give us a contemporary example of that formula in action?

Goldberg: Here’s one that was really moving: this student, Avery Camp, is in a class I’m teaching at the New School, and we went to the archives at the LGBT Community Center in New York to look at periodicals. Their assignment was to make a newsletter, message, poster, or sign. Avery made a flyer with information about how to volunteer for the Trevor Project , which is currently dealing with a high volume of calls and a lack of volunteers.

I asked the museum to distribute Camp’s flyer at the exhibition. J. Soto, director of engagement and inclusion at Leslie-Lohman, printed it in a handbill size for visitors to take and spread the word. That’s the legacy right there. You don’t need a lot of people to get something done. It’s not that complicated. Let’s do something now .

Images on which to build, 1970s–1990s is on view at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York, through July 30, 2023.

You May Also Like

What Christopher Gregory-Rivera Discovered in Puerto Rico’s State Secrets

Annie Ernaux Inspires an Exhibition about Fleeting Encounters

Naomieh Jovin’s Photo Collages of Haitian American Life

How One Photographer Documented Ghana’s Transformations

In Public Spaces, Tender Photographs about Love and Friendship

How Kishin Shinoyama Found Fame and Controversy

A Photographer Deconstructs Masculinity and Colonialism

12 Essential Photobooks by Women Photographers

A Mother’s Relentless Quest to Find her Missing Son

Picturing Warmth and Belonging in Muslim Communities

17 Powerful Pictures From LGBT History

"Our society didn’t just change naturally, it changed because people got politically active."

BuzzFeed News Photo Essay Editor

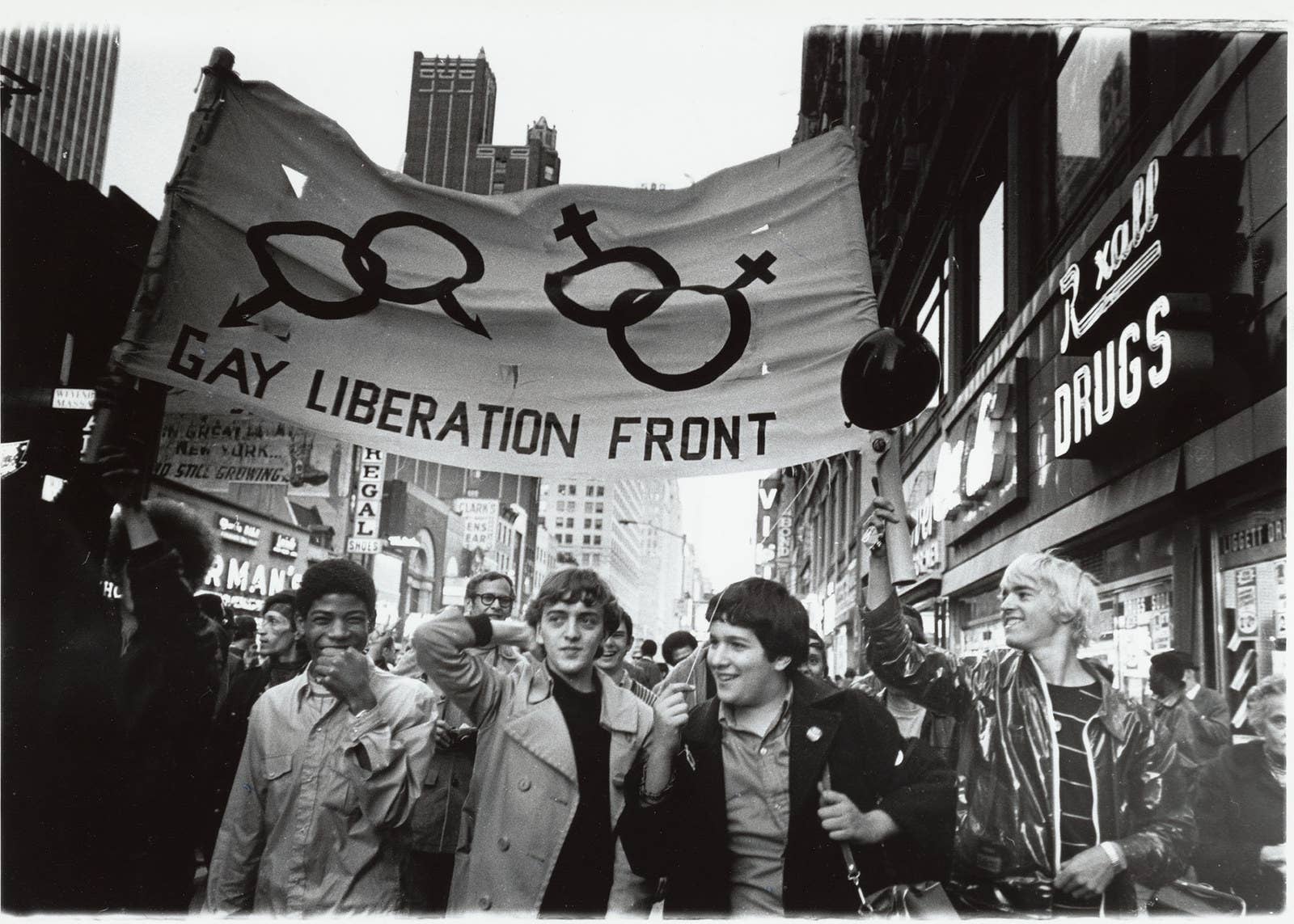

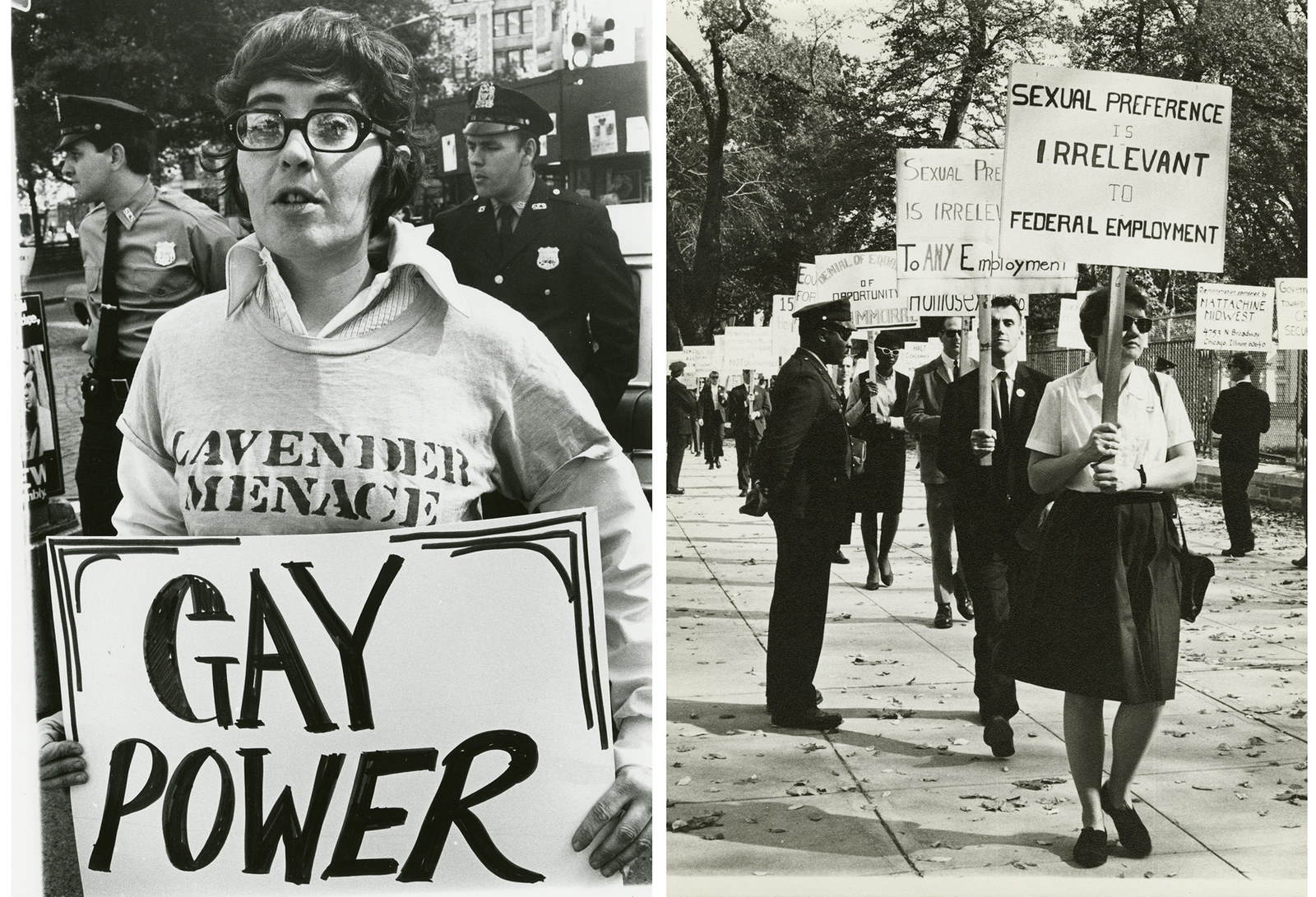

Photo by Diana Davies: Gay Liberation Front marches on Times Square, New York, 1970.

In the 1960s and '70s, amid a climate of political upheaval and civil rights activism, LGBT communities across the US were uniting for visibility and change. Events like the 1969 Stonewall riots , which saw LGBT activists rise up against discrimination in New York City , helped to galvanize this movement by bringing together a generation of queer young people under a banner of pride. And the work of photojournalists such as Kay Tobin Lahusen and Diana Davies brought this movement to the masses through their groundbreaking photography.

A new exhibition at the New York Public Library titled Love & Resistance: Stonewall 50 brings together the work of these two influential photographers, as well as periodicals, flyers, and first-person narratives from this pivotal moment in LGBT history.

The show is curated by Jason Baumann, the NYPL's assistant director of collection development. BuzzFeed News spoke with Baumann, who coordinates the library's LGBT initiatives, about how photography helped to shape the modern LGBT movement as well as the lasting legacy of Stonewall, 50 years after the riots.

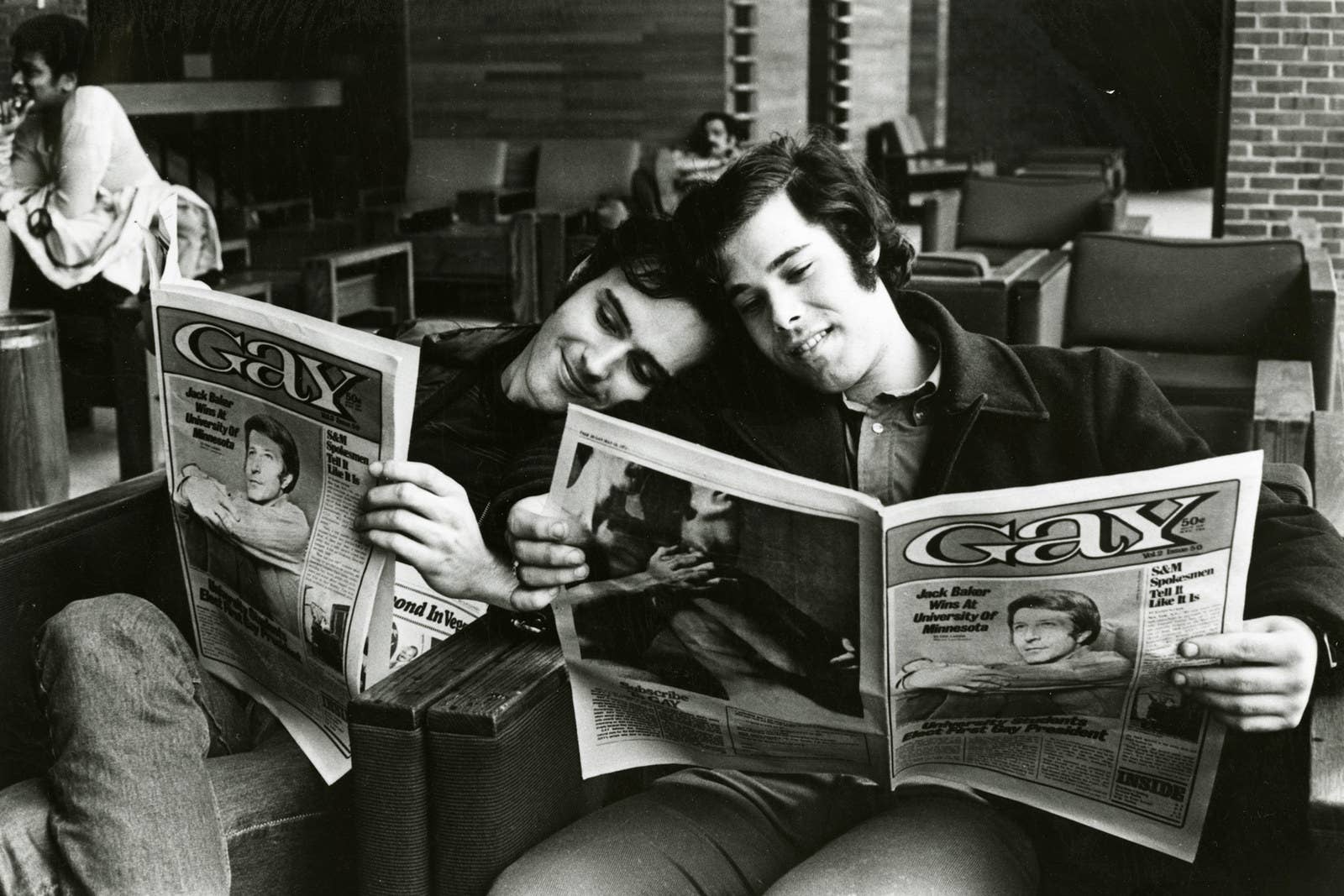

Photo by Kay Tobin Lahusen: Men reading Gay magazine, 1971.

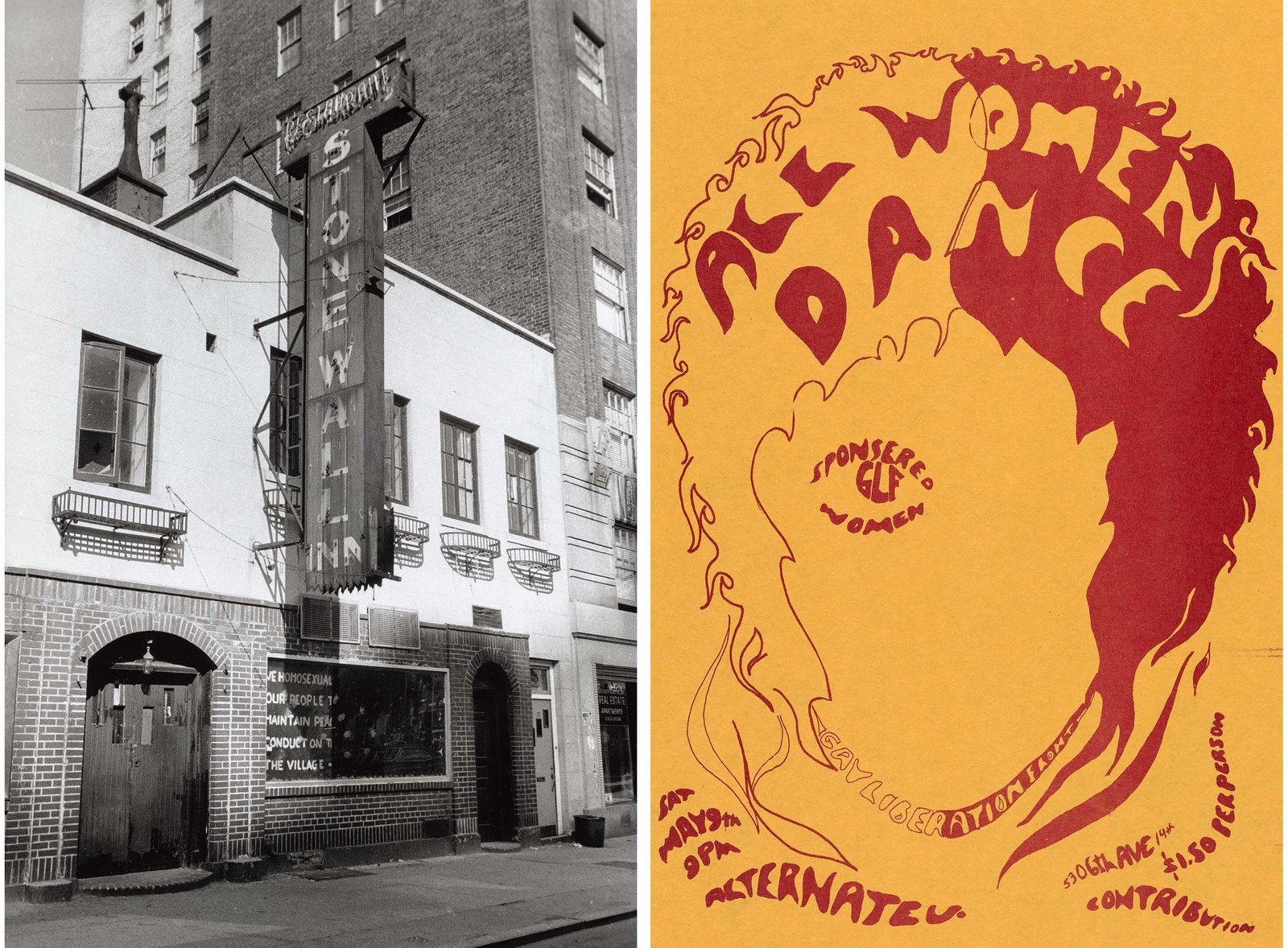

Left: Photo by Diana Davies: Stonewall Inn, 1969. Right: “All Women’s Dance” New York, Gay Liberation Front, 1970.

Who were Kay Tobin Lahusen and Diana Davies?

Jason Baumann: Kay was one of the first LGBT photojournalists in the United States documenting LGBT political communities. She started her career photographing for a magazine called the Ladder in the early 1960s, which was the main magazine for lesbians in the US at that time. Before Kay, the magazine depicted people mostly through cartoons; if they were photographed, it was in silhouette or from behind to protect the identity of the people in the pictures.

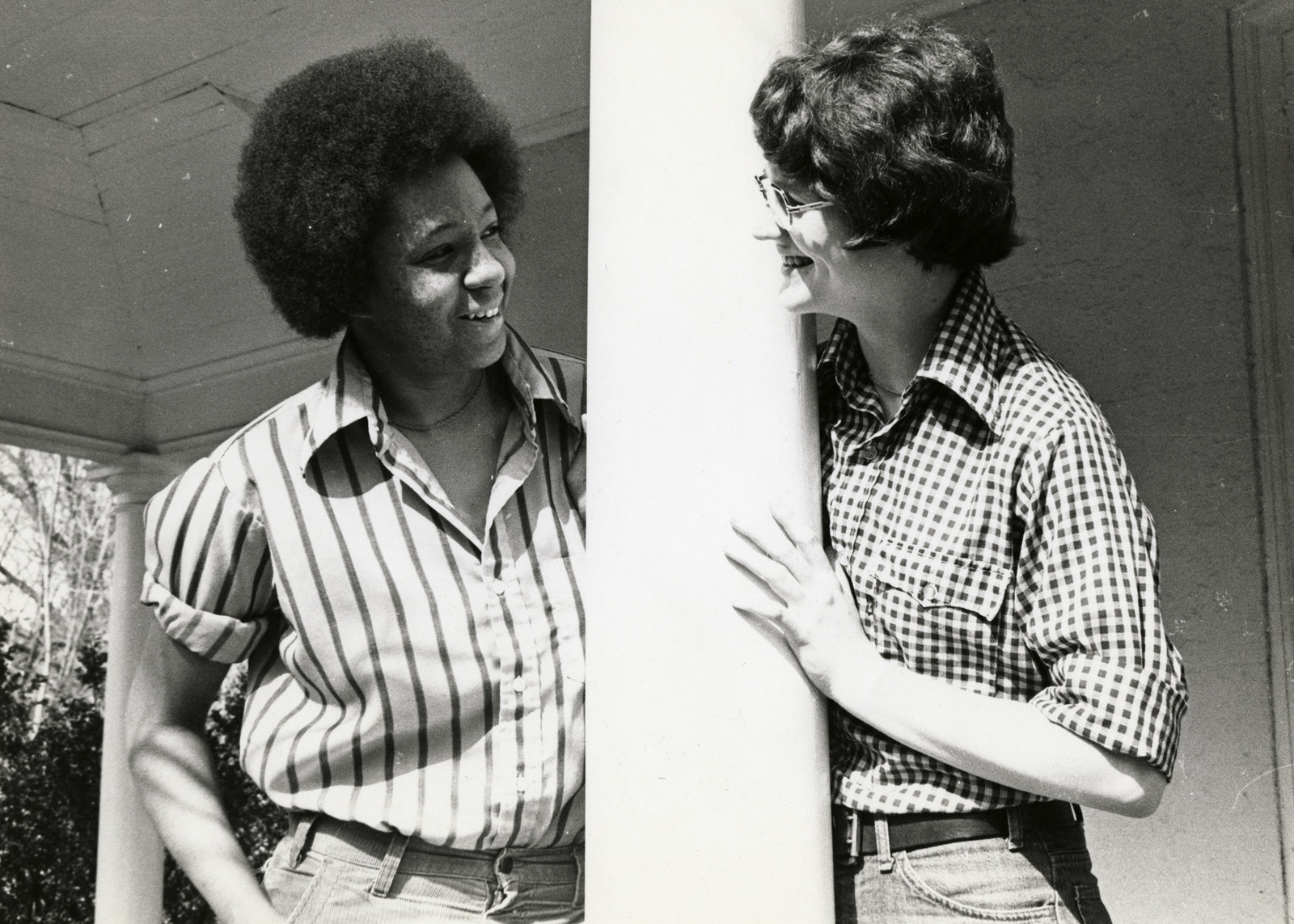

She broke with this by placing out lesbians on the cover. A lot of these pictures are some of the first positive images of lesbians in American culture. There simply weren’t images of lesbians being depicted as smiling, happy, well-adjusted people before Kay made them. By the 1970s, she was documenting essentially all of the major activity and demonstrations that were happening.

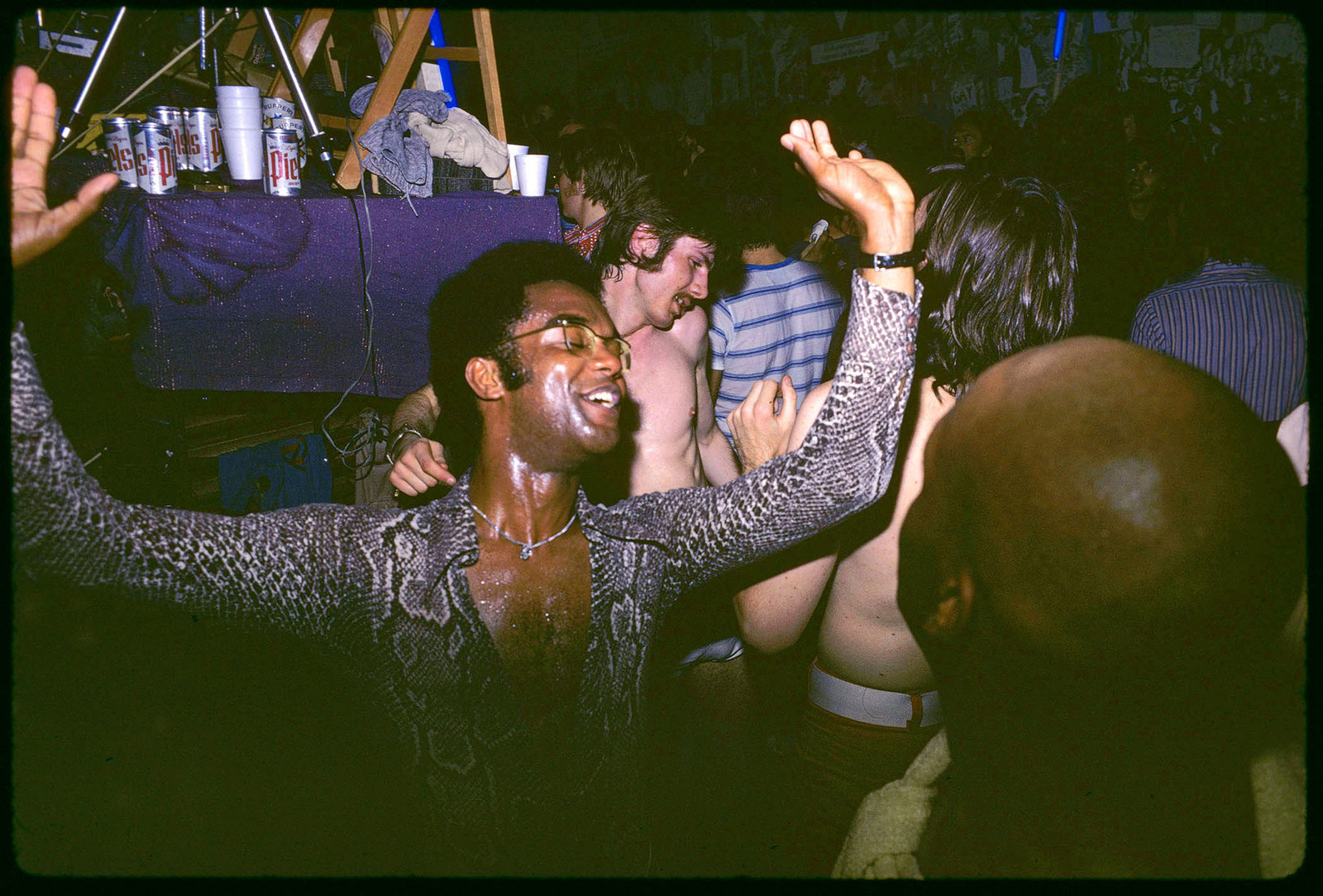

Photo by Dance at Gay Activists Alliance Firehouse, 1971

Left: Photo by Diana Davies: “Ida,” member of the Gay Liberation Front and Lavender Menace, 1970. Right: Photo by Kay Tobin Lahusen, Ernestine Eckstein, and Barbara Gittings: Third White House picket, 1965.

Diana was another photographer who honed her craft in the 1960s, documenting the antiwar movements, the civil rights movements, as well as the jazz and blues music scenes. Then in ’69 she became part of this organization called the Gay Liberation Front and began documenting gay, lesbian, and transgender activists in New York City and around the country.

How was photography weaponized as a tool for LGBT activism?

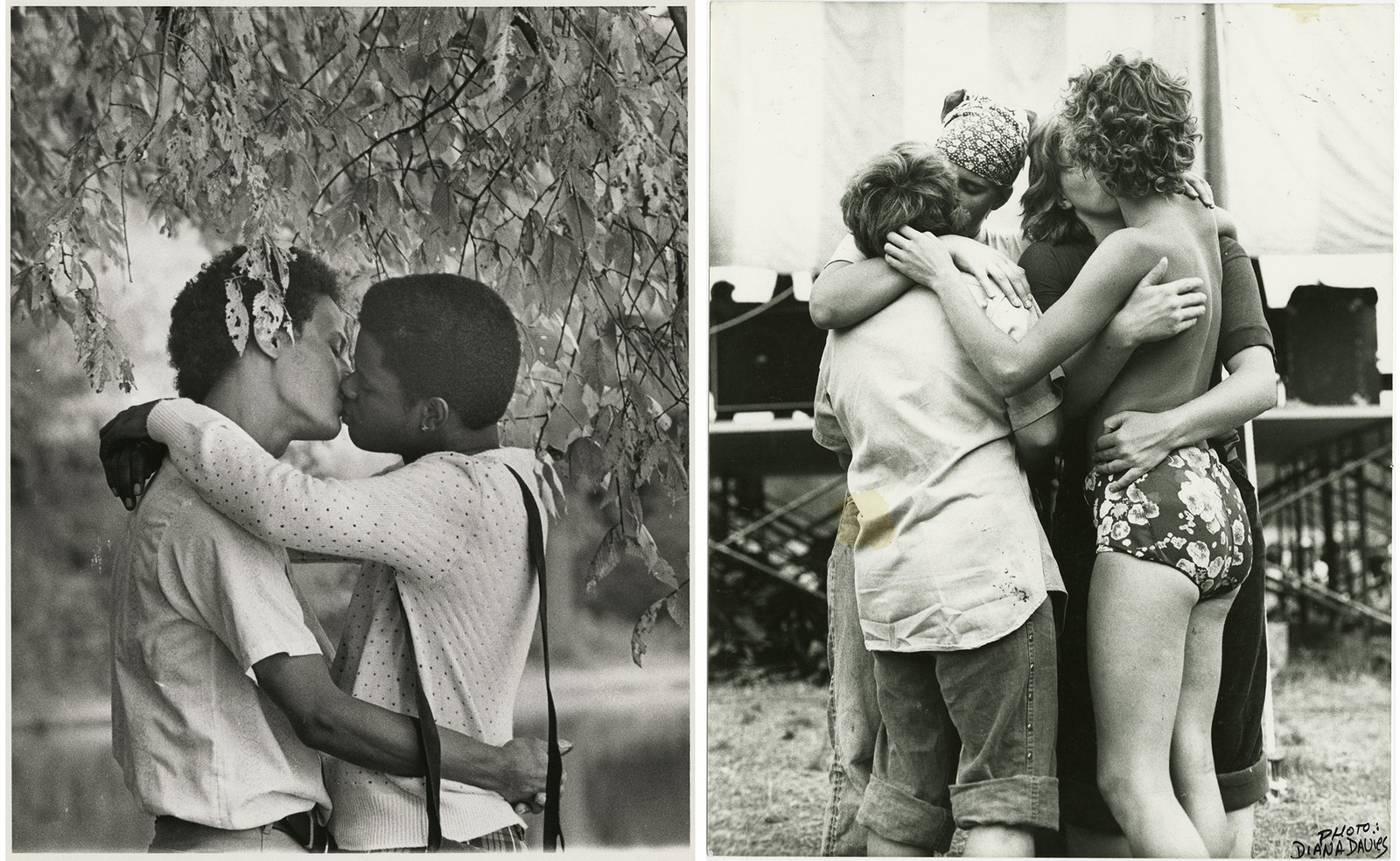

JB: The exhibition and the book have this section on “love” that I think are most telling in this regard. You have these images that are always shot from behind or in silhouette — so you’re depicting the person but also protecting their identity at the same time. This was due to the fact that homosexuality was illegal in the United States during this era. In New York, you could serve three months in prison and in some states you could be sentenced to life in prison. You could be institutionalized, subjected to electric shock treatment, you could lose your job — so very few people are willing to be publicly depicted in this way.

Left: Photo by Kay Tobin Lahusen: Men kissing under a tree, 1977. Right: Photo by Diana Davies: Women embracing at Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, 1976.

Post-Stonewall you have a real emergence as part of gay liberation of trying to document these people’s lives. These photographers were a part of a movement of gay visibility with the objective of taking back public space. Part of the oppression faced by gay and transgender people in the ‘60s was being denied access to public space. A bar could be shut down if they had gay patrons, you could be arrested for cross-dressing during the time. So part of creating these images was to depict these individuals as full human beings.

Photo by Kay Tobin Lahusen: Nancy Tucker and her partner in butch-femme T-shirts, 1970.

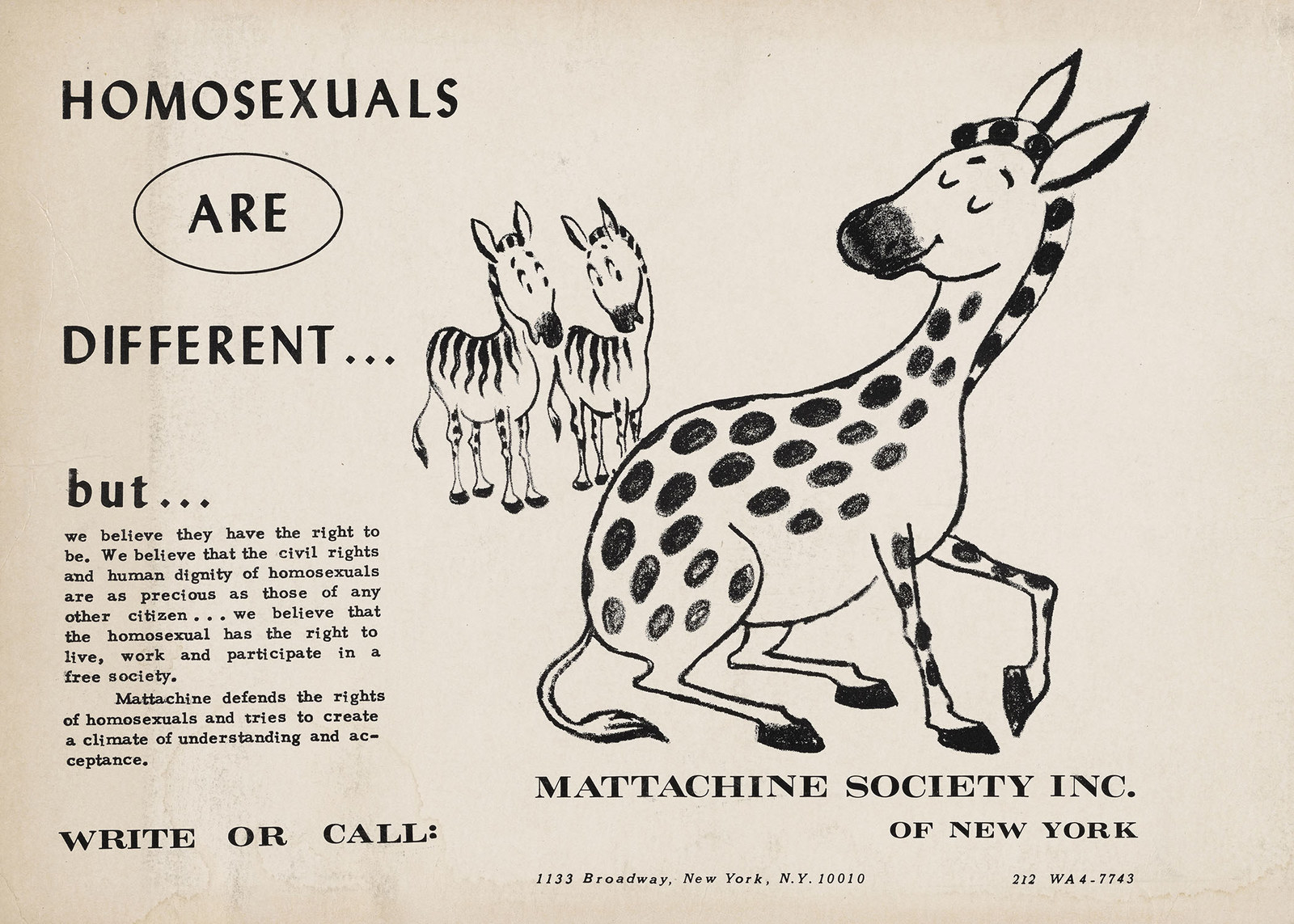

“Homosexuals Are Different…” Mattachine Society of New York, 1960s.

What are some of the misconceptions about the Stonewall riots?

JB: The Stonewall Inn was a Mafia-controlled bar at the time that operated in the Village and was often raided by police. The riots happened at the end of June 1969, when the bar was raided one evening as part of a state crackdown on drinking establishments that did not have their liquor license — as well as the fact that the bar was serving gay and transgender people, who were considered criminal clientele at the time.

During the raid a lot of the clientele began to fight back, but what most overlook is that a lot of those who were fighting back were the people on the streets at the time: disenfranchised queer youths who were living on the streets of New York City and in the Village, many of whom had been kicked out by their families, had difficulty finding jobs because they were gender nonconforming, and this really became the core of the people who fought back against the police that night.

Photo by Diana Davies: Demonstration at City Hall, New York (from left: Sylvia Rivera, Marsha P. Johnson, Jane Vercaine, Barbara Deming, Kady Vandeurs, Carol Grosberg, and others), 1973.

Photo by Kay Tobin Lahusen: Jamen Butler, left, and Tom Malim, 1971.

Many of the people who were participating in the Stonewall riots were younger people — youths who were influenced by American counterculture, antiwar movements, and who had very different expectations of what activism was about compared to older generations. This was a different ideological framework that was much more confrontational and influenced by anarchism, Marxism, and civil rights protests.

The problem with Stonewall is that people want to believe that this was the beginning of this movement, but it really wasn’t. Stonewall wasn't the first of these riots — there were a number of similar riots across the US in the 1960s as well as demonstrations and activism. Stonewall was more of a turning point in that movement. It’s when this became a mass movement — from groups of 10 to 20 people in every state to thousands of people coming out of the closet to change American society.

Left: Transvestia no. 16, Los Angeles : Chevalier Publications, 1962. Right: Black and Blue vol. 1, no. 5, New York Motor Bike Club, September 1967.

Photo by Kay Tobin Lahusen: Germantown couple on porch, 1977.

What do you hope people will take away from this exhibit?

JB: I’d like people to realize that this was a civil rights movement. That our society didn’t just change naturally, it changed because people got politically active.

I think that’s the trouble with how the story of Stonewall gets told — this idea that there was this riot at a bar, then magically there were gay rights. What’s not told is that there was this intensive civil rights activism that took place over the course of 50 years in the United States and that’s why society changed. I also want people to come away feeling empowered, knowing that people before them have made a difference in their society and that they can make a difference too.

Photo by Diana Davies: Martha Shelley sells Gay Liberation Front paper during Weinstein Hall demonstration, 1970.

Love & Resistance: Stonewall 50 is on view at the New York Public Library from Feb. 14to July 13, 2019. To learn more, visit nypl.org .

Topics in this article.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

January 17, 2017 1:45 PM EST. “I was 19, vulnerable, young and putting my own identity together,” says photographer Anthony Friedkin when reflecting on his first project, The Gay Essay, which ...

Kerry Manders is a writer based in Toronto. Tags Queer 1990s 1970s 1980s JEB (Joan E. Biren) Diana Solís Kerry Manders. The exhibition "Images on which to build, 1970s–1990s" showcases artists and collectives that built trans and queer image cultures with lasting influence.

Left: Photo by Diana Davies: “Ida,” member of the Gay Liberation Front and Lavender Menace, 1970. Right: Photo by Kay Tobin Lahusen, Ernestine Eckstein, and Barbara Gittings: Third White House picket, 1965. Diana was another photographer who honed her craft in the 1960s, documenting the antiwar movements, the civil rights movements, as well ...