- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- French Abstracts

- Portuguese Abstracts

- Spanish Abstracts

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About International Journal for Quality in Health Care

- About the International Society for Quality in Health Care

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Contact ISQua

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Primacy of the research question, structure of the paper, writing a research article: advice to beginners.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Thomas V. Perneger, Patricia M. Hudelson, Writing a research article: advice to beginners, International Journal for Quality in Health Care , Volume 16, Issue 3, June 2004, Pages 191–192, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzh053

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Writing research papers does not come naturally to most of us. The typical research paper is a highly codified rhetorical form [ 1 , 2 ]. Knowledge of the rules—some explicit, others implied—goes a long way toward writing a paper that will get accepted in a peer-reviewed journal.

A good research paper addresses a specific research question. The research question—or study objective or main research hypothesis—is the central organizing principle of the paper. Whatever relates to the research question belongs in the paper; the rest doesn’t. This is perhaps obvious when the paper reports on a well planned research project. However, in applied domains such as quality improvement, some papers are written based on projects that were undertaken for operational reasons, and not with the primary aim of producing new knowledge. In such cases, authors should define the main research question a posteriori and design the paper around it.

Generally, only one main research question should be addressed in a paper (secondary but related questions are allowed). If a project allows you to explore several distinct research questions, write several papers. For instance, if you measured the impact of obtaining written consent on patient satisfaction at a specialized clinic using a newly developed questionnaire, you may want to write one paper on the questionnaire development and validation, and another on the impact of the intervention. The idea is not to split results into ‘least publishable units’, a practice that is rightly decried, but rather into ‘optimally publishable units’.

What is a good research question? The key attributes are: (i) specificity; (ii) originality or novelty; and (iii) general relevance to a broad scientific community. The research question should be precise and not merely identify a general area of inquiry. It can often (but not always) be expressed in terms of a possible association between X and Y in a population Z, for example ‘we examined whether providing patients about to be discharged from the hospital with written information about their medications would improve their compliance with the treatment 1 month later’. A study does not necessarily have to break completely new ground, but it should extend previous knowledge in a useful way, or alternatively refute existing knowledge. Finally, the question should be of interest to others who work in the same scientific area. The latter requirement is more challenging for those who work in applied science than for basic scientists. While it may safely be assumed that the human genome is the same worldwide, whether the results of a local quality improvement project have wider relevance requires careful consideration and argument.

Once the research question is clearly defined, writing the paper becomes considerably easier. The paper will ask the question, then answer it. The key to successful scientific writing is getting the structure of the paper right. The basic structure of a typical research paper is the sequence of Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion (sometimes abbreviated as IMRAD). Each section addresses a different objective. The authors state: (i) the problem they intend to address—in other terms, the research question—in the Introduction; (ii) what they did to answer the question in the Methods section; (iii) what they observed in the Results section; and (iv) what they think the results mean in the Discussion.

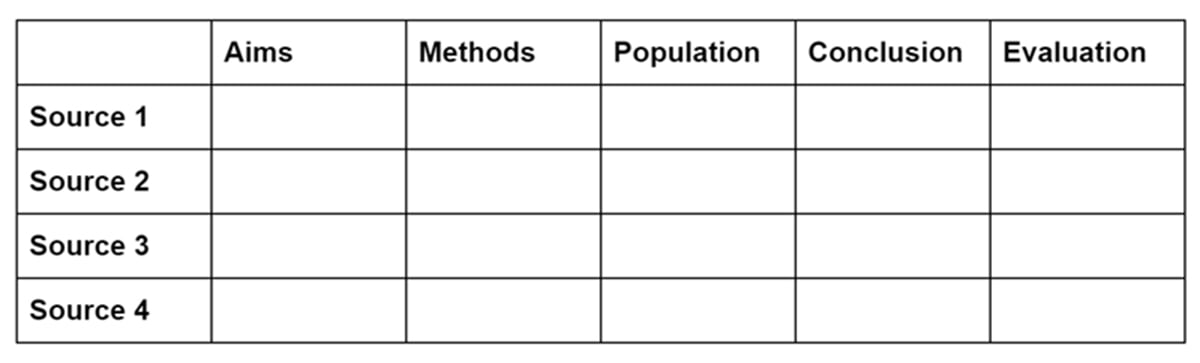

In turn, each basic section addresses several topics, and may be divided into subsections (Table 1 ). In the Introduction, the authors should explain the rationale and background to the study. What is the research question, and why is it important to ask it? While it is neither necessary nor desirable to provide a full-blown review of the literature as a prelude to the study, it is helpful to situate the study within some larger field of enquiry. The research question should always be spelled out, and not merely left for the reader to guess.

Typical structure of a research paper

The Methods section should provide the readers with sufficient detail about the study methods to be able to reproduce the study if so desired. Thus, this section should be specific, concrete, technical, and fairly detailed. The study setting, the sampling strategy used, instruments, data collection methods, and analysis strategies should be described. In the case of qualitative research studies, it is also useful to tell the reader which research tradition the study utilizes and to link the choice of methodological strategies with the research goals [ 3 ].

The Results section is typically fairly straightforward and factual. All results that relate to the research question should be given in detail, including simple counts and percentages. Resist the temptation to demonstrate analytic ability and the richness of the dataset by providing numerous tables of non-essential results.

The Discussion section allows the most freedom. This is why the Discussion is the most difficult to write, and is often the weakest part of a paper. Structured Discussion sections have been proposed by some journal editors [ 4 ]. While strict adherence to such rules may not be necessary, following a plan such as that proposed in Table 1 may help the novice writer stay on track.

References should be used wisely. Key assertions should be referenced, as well as the methods and instruments used. However, unless the paper is a comprehensive review of a topic, there is no need to be exhaustive. Also, references to unpublished work, to documents in the grey literature (technical reports), or to any source that the reader will have difficulty finding or understanding should be avoided.

Having the structure of the paper in place is a good start. However, there are many details that have to be attended to while writing. An obvious recommendation is to read, and follow, the instructions to authors published by the journal (typically found on the journal’s website). Another concerns non-native writers of English: do have a native speaker edit the manuscript. A paper usually goes through several drafts before it is submitted. When revising a paper, it is useful to keep an eye out for the most common mistakes (Table 2 ). If you avoid all those, your paper should be in good shape.

Common mistakes seen in manuscripts submitted to this journal

Huth EJ . How to Write and Publish Papers in the Medical Sciences , 2nd edition. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1990 .

Browner WS . Publishing and Presenting Clinical Research . Baltimore, MD: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 1999 .

Devers KJ , Frankel RM. Getting qualitative research published. Educ Health 2001 ; 14 : 109 –117.

Docherty M , Smith R. The case for structuring the discussion of scientific papers. Br Med J 1999 ; 318 : 1224 –1225.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1464-3677

- Print ISSN 1353-4505

- Copyright © 2024 International Society for Quality in Health Care and Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

How To Write A Research Paper

Step-By-Step Tutorial With Examples + FREE Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | March 2024

For many students, crafting a strong research paper from scratch can feel like a daunting task – and rightly so! In this post, we’ll unpack what a research paper is, what it needs to do , and how to write one – in three easy steps. 🙂

Overview: Writing A Research Paper

What (exactly) is a research paper.

- How to write a research paper

- Stage 1 : Topic & literature search

- Stage 2 : Structure & outline

- Stage 3 : Iterative writing

- Key takeaways

Let’s start by asking the most important question, “ What is a research paper? ”.

Simply put, a research paper is a scholarly written work where the writer (that’s you!) answers a specific question (this is called a research question ) through evidence-based arguments . Evidence-based is the keyword here. In other words, a research paper is different from an essay or other writing assignments that draw from the writer’s personal opinions or experiences. With a research paper, it’s all about building your arguments based on evidence (we’ll talk more about that evidence a little later).

Now, it’s worth noting that there are many different types of research papers , including analytical papers (the type I just described), argumentative papers, and interpretative papers. Here, we’ll focus on analytical papers , as these are some of the most common – but if you’re keen to learn about other types of research papers, be sure to check out the rest of the blog .

With that basic foundation laid, let’s get down to business and look at how to write a research paper .

Overview: The 3-Stage Process

While there are, of course, many potential approaches you can take to write a research paper, there are typically three stages to the writing process. So, in this tutorial, we’ll present a straightforward three-step process that we use when working with students at Grad Coach.

These three steps are:

- Finding a research topic and reviewing the existing literature

- Developing a provisional structure and outline for your paper, and

- Writing up your initial draft and then refining it iteratively

Let’s dig into each of these.

Need a helping hand?

Step 1: Find a topic and review the literature

As we mentioned earlier, in a research paper, you, as the researcher, will try to answer a question . More specifically, that’s called a research question , and it sets the direction of your entire paper. What’s important to understand though is that you’ll need to answer that research question with the help of high-quality sources – for example, journal articles, government reports, case studies, and so on. We’ll circle back to this in a minute.

The first stage of the research process is deciding on what your research question will be and then reviewing the existing literature (in other words, past studies and papers) to see what they say about that specific research question. In some cases, your professor may provide you with a predetermined research question (or set of questions). However, in many cases, you’ll need to find your own research question within a certain topic area.

Finding a strong research question hinges on identifying a meaningful research gap – in other words, an area that’s lacking in existing research. There’s a lot to unpack here, so if you wanna learn more, check out the plain-language explainer video below.

Once you’ve figured out which question (or questions) you’ll attempt to answer in your research paper, you’ll need to do a deep dive into the existing literature – this is called a “ literature search ”. Again, there are many ways to go about this, but your most likely starting point will be Google Scholar .

If you’re new to Google Scholar, think of it as Google for the academic world. You can start by simply entering a few different keywords that are relevant to your research question and it will then present a host of articles for you to review. What you want to pay close attention to here is the number of citations for each paper – the more citations a paper has, the more credible it is (generally speaking – there are some exceptions, of course).

Ideally, what you’re looking for are well-cited papers that are highly relevant to your topic. That said, keep in mind that citations are a cumulative metric , so older papers will often have more citations than newer papers – just because they’ve been around for longer. So, don’t fixate on this metric in isolation – relevance and recency are also very important.

Beyond Google Scholar, you’ll also definitely want to check out academic databases and aggregators such as Science Direct, PubMed, JStor and so on. These will often overlap with the results that you find in Google Scholar, but they can also reveal some hidden gems – so, be sure to check them out.

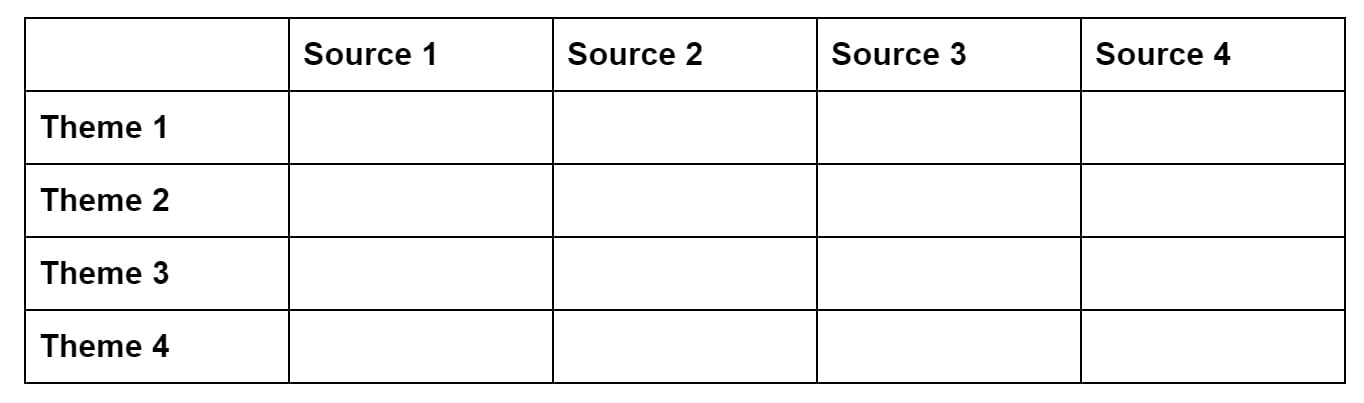

Once you’ve worked your way through all the literature, you’ll want to catalogue all this information in some sort of spreadsheet so that you can easily recall who said what, when and within what context. If you’d like, we’ve got a free literature spreadsheet that helps you do exactly that.

Step 2: Develop a structure and outline

With your research question pinned down and your literature digested and catalogued, it’s time to move on to planning your actual research paper .

It might sound obvious, but it’s really important to have some sort of rough outline in place before you start writing your paper. So often, we see students eagerly rushing into the writing phase, only to land up with a disjointed research paper that rambles on in multiple

Now, the secret here is to not get caught up in the fine details . Realistically, all you need at this stage is a bullet-point list that describes (in broad strokes) what you’ll discuss and in what order. It’s also useful to remember that you’re not glued to this outline – in all likelihood, you’ll chop and change some sections once you start writing, and that’s perfectly okay. What’s important is that you have some sort of roadmap in place from the start.

At this stage you might be wondering, “ But how should I structure my research paper? ”. Well, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution here, but in general, a research paper will consist of a few relatively standardised components:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Methodology

Let’s take a look at each of these.

First up is the introduction section . As the name suggests, the purpose of the introduction is to set the scene for your research paper. There are usually (at least) four ingredients that go into this section – these are the background to the topic, the research problem and resultant research question , and the justification or rationale. If you’re interested, the video below unpacks the introduction section in more detail.

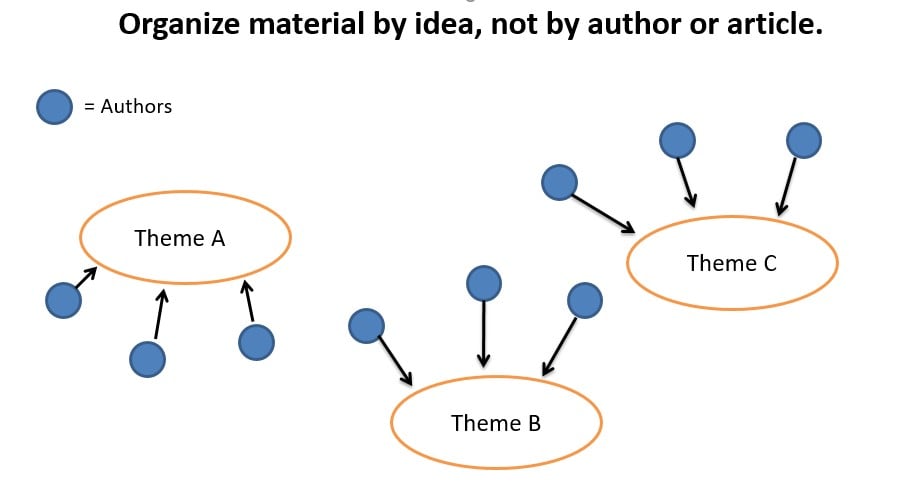

The next section of your research paper will typically be your literature review . Remember all that literature you worked through earlier? Well, this is where you’ll present your interpretation of all that content . You’ll do this by writing about recent trends, developments, and arguments within the literature – but more specifically, those that are relevant to your research question . The literature review can oftentimes seem a little daunting, even to seasoned researchers, so be sure to check out our extensive collection of literature review content here .

With the introduction and lit review out of the way, the next section of your paper is the research methodology . In a nutshell, the methodology section should describe to your reader what you did (beyond just reviewing the existing literature) to answer your research question. For example, what data did you collect, how did you collect that data, how did you analyse that data and so on? For each choice, you’ll also need to justify why you chose to do it that way, and what the strengths and weaknesses of your approach were.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that for some research papers, this aspect of the project may be a lot simpler . For example, you may only need to draw on secondary sources (in other words, existing data sets). In some cases, you may just be asked to draw your conclusions from the literature search itself (in other words, there may be no data analysis at all). But, if you are required to collect and analyse data, you’ll need to pay a lot of attention to the methodology section. The video below provides an example of what the methodology section might look like.

By this stage of your paper, you will have explained what your research question is, what the existing literature has to say about that question, and how you analysed additional data to try to answer your question. So, the natural next step is to present your analysis of that data . This section is usually called the “results” or “analysis” section and this is where you’ll showcase your findings.

Depending on your school’s requirements, you may need to present and interpret the data in one section – or you might split the presentation and the interpretation into two sections. In the latter case, your “results” section will just describe the data, and the “discussion” is where you’ll interpret that data and explicitly link your analysis back to your research question. If you’re not sure which approach to take, check in with your professor or take a look at past papers to see what the norms are for your programme.

Alright – once you’ve presented and discussed your results, it’s time to wrap it up . This usually takes the form of the “ conclusion ” section. In the conclusion, you’ll need to highlight the key takeaways from your study and close the loop by explicitly answering your research question. Again, the exact requirements here will vary depending on your programme (and you may not even need a conclusion section at all) – so be sure to check with your professor if you’re unsure.

Step 3: Write and refine

Finally, it’s time to get writing. All too often though, students hit a brick wall right about here… So, how do you avoid this happening to you?

Well, there’s a lot to be said when it comes to writing a research paper (or any sort of academic piece), but we’ll share three practical tips to help you get started.

First and foremost , it’s essential to approach your writing as an iterative process. In other words, you need to start with a really messy first draft and then polish it over multiple rounds of editing. Don’t waste your time trying to write a perfect research paper in one go. Instead, take the pressure off yourself by adopting an iterative approach.

Secondly , it’s important to always lean towards critical writing , rather than descriptive writing. What does this mean? Well, at the simplest level, descriptive writing focuses on the “ what ”, while critical writing digs into the “ so what ” – in other words, the implications. If you’re not familiar with these two types of writing, don’t worry! You can find a plain-language explanation here.

Last but not least, you’ll need to get your referencing right. Specifically, you’ll need to provide credible, correctly formatted citations for the statements you make. We see students making referencing mistakes all the time and it costs them dearly. The good news is that you can easily avoid this by using a simple reference manager . If you don’t have one, check out our video about Mendeley, an easy (and free) reference management tool that you can start using today.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. To recap, the three steps to writing a high-quality research paper are:

- To choose a research question and review the literature

- To plan your paper structure and draft an outline

- To take an iterative approach to writing, focusing on critical writing and strong referencing

Remember, this is just a b ig-picture overview of the research paper development process and there’s a lot more nuance to unpack. So, be sure to grab a copy of our free research paper template to learn more about how to write a research paper.

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Yale J Biol Med

- v.84(3); 2011 Sep

Focus: Education — Career Advice

How to write your first research paper.

Writing a research manuscript is an intimidating process for many novice writers in the sciences. One of the stumbling blocks is the beginning of the process and creating the first draft. This paper presents guidelines on how to initiate the writing process and draft each section of a research manuscript. The paper discusses seven rules that allow the writer to prepare a well-structured and comprehensive manuscript for a publication submission. In addition, the author lists different strategies for successful revision. Each of those strategies represents a step in the revision process and should help the writer improve the quality of the manuscript. The paper could be considered a brief manual for publication.

It is late at night. You have been struggling with your project for a year. You generated an enormous amount of interesting data. Your pipette feels like an extension of your hand, and running western blots has become part of your daily routine, similar to brushing your teeth. Your colleagues think you are ready to write a paper, and your lab mates tease you about your “slow” writing progress. Yet days pass, and you cannot force yourself to sit down to write. You have not written anything for a while (lab reports do not count), and you feel you have lost your stamina. How does the writing process work? How can you fit your writing into a daily schedule packed with experiments? What section should you start with? What distinguishes a good research paper from a bad one? How should you revise your paper? These and many other questions buzz in your head and keep you stressed. As a result, you procrastinate. In this paper, I will discuss the issues related to the writing process of a scientific paper. Specifically, I will focus on the best approaches to start a scientific paper, tips for writing each section, and the best revision strategies.

1. Schedule your writing time in Outlook

Whether you have written 100 papers or you are struggling with your first, starting the process is the most difficult part unless you have a rigid writing schedule. Writing is hard. It is a very difficult process of intense concentration and brain work. As stated in Hayes’ framework for the study of writing: “It is a generative activity requiring motivation, and it is an intellectual activity requiring cognitive processes and memory” [ 1 ]. In his book How to Write a Lot: A Practical Guide to Productive Academic Writing , Paul Silvia says that for some, “it’s easier to embalm the dead than to write an article about it” [ 2 ]. Just as with any type of hard work, you will not succeed unless you practice regularly. If you have not done physical exercises for a year, only regular workouts can get you into good shape again. The same kind of regular exercises, or I call them “writing sessions,” are required to be a productive author. Choose from 1- to 2-hour blocks in your daily work schedule and consider them as non-cancellable appointments. When figuring out which blocks of time will be set for writing, you should select the time that works best for this type of work. For many people, mornings are more productive. One Yale University graduate student spent a semester writing from 8 a.m. to 9 a.m. when her lab was empty. At the end of the semester, she was amazed at how much she accomplished without even interrupting her regular lab hours. In addition, doing the hardest task first thing in the morning contributes to the sense of accomplishment during the rest of the day. This positive feeling spills over into our work and life and has a very positive effect on our overall attitude.

Rule 1: Create regular time blocks for writing as appointments in your calendar and keep these appointments.

2. start with an outline.

Now that you have scheduled time, you need to decide how to start writing. The best strategy is to start with an outline. This will not be an outline that you are used to, with Roman numerals for each section and neat parallel listing of topic sentences and supporting points. This outline will be similar to a template for your paper. Initially, the outline will form a structure for your paper; it will help generate ideas and formulate hypotheses. Following the advice of George M. Whitesides, “. . . start with a blank piece of paper, and write down, in any order, all important ideas that occur to you concerning the paper” [ 3 ]. Use Table 1 as a starting point for your outline. Include your visuals (figures, tables, formulas, equations, and algorithms), and list your findings. These will constitute the first level of your outline, which will eventually expand as you elaborate.

The next stage is to add context and structure. Here you will group all your ideas into sections: Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion/Conclusion ( Table 2 ). This step will help add coherence to your work and sift your ideas.

Now that you have expanded your outline, you are ready for the next step: discussing the ideas for your paper with your colleagues and mentor. Many universities have a writing center where graduate students can schedule individual consultations and receive assistance with their paper drafts. Getting feedback during early stages of your draft can save a lot of time. Talking through ideas allows people to conceptualize and organize thoughts to find their direction without wasting time on unnecessary writing. Outlining is the most effective way of communicating your ideas and exchanging thoughts. Moreover, it is also the best stage to decide to which publication you will submit the paper. Many people come up with three choices and discuss them with their mentors and colleagues. Having a list of journal priorities can help you quickly resubmit your paper if your paper is rejected.

Rule 2: Create a detailed outline and discuss it with your mentor and peers.

3. continue with drafts.

After you get enough feedback and decide on the journal you will submit to, the process of real writing begins. Copy your outline into a separate file and expand on each of the points, adding data and elaborating on the details. When you create the first draft, do not succumb to the temptation of editing. Do not slow down to choose a better word or better phrase; do not halt to improve your sentence structure. Pour your ideas into the paper and leave revision and editing for later. As Paul Silvia explains, “Revising while you generate text is like drinking decaffeinated coffee in the early morning: noble idea, wrong time” [ 2 ].

Many students complain that they are not productive writers because they experience writer’s block. Staring at an empty screen is frustrating, but your screen is not really empty: You have a template of your article, and all you need to do is fill in the blanks. Indeed, writer’s block is a logical fallacy for a scientist ― it is just an excuse to procrastinate. When scientists start writing a research paper, they already have their files with data, lab notes with materials and experimental designs, some visuals, and tables with results. All they need to do is scrutinize these pieces and put them together into a comprehensive paper.

3.1. Starting with Materials and Methods

If you still struggle with starting a paper, then write the Materials and Methods section first. Since you have all your notes, it should not be problematic for you to describe the experimental design and procedures. Your most important goal in this section is to be as explicit as possible by providing enough detail and references. In the end, the purpose of this section is to allow other researchers to evaluate and repeat your work. So do not run into the same problems as the writers of the sentences in (1):

1a. Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation. 1b. To isolate T cells, lymph nodes were collected.

As you can see, crucial pieces of information are missing: the speed of centrifuging your bacteria, the time, and the temperature in (1a); the source of lymph nodes for collection in (b). The sentences can be improved when information is added, as in (2a) and (2b), respectfully:

2a. Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation at 3000g for 15 min at 25°C. 2b. To isolate T cells, mediastinal and mesenteric lymph nodes from Balb/c mice were collected at day 7 after immunization with ovabumin.

If your method has previously been published and is well-known, then you should provide only the literature reference, as in (3a). If your method is unpublished, then you need to make sure you provide all essential details, as in (3b).

3a. Stem cells were isolated, according to Johnson [23]. 3b. Stem cells were isolated using biotinylated carbon nanotubes coated with anti-CD34 antibodies.

Furthermore, cohesion and fluency are crucial in this section. One of the malpractices resulting in disrupted fluency is switching from passive voice to active and vice versa within the same paragraph, as shown in (4). This switching misleads and distracts the reader.

4. Behavioral computer-based experiments of Study 1 were programmed by using E-Prime. We took ratings of enjoyment, mood, and arousal as the patients listened to preferred pleasant music and unpreferred music by using Visual Analogue Scales (SI Methods). The preferred and unpreferred status of the music was operationalized along a continuum of pleasantness [ 4 ].

The problem with (4) is that the reader has to switch from the point of view of the experiment (passive voice) to the point of view of the experimenter (active voice). This switch causes confusion about the performer of the actions in the first and the third sentences. To improve the coherence and fluency of the paragraph above, you should be consistent in choosing the point of view: first person “we” or passive voice [ 5 ]. Let’s consider two revised examples in (5).

5a. We programmed behavioral computer-based experiments of Study 1 by using E-Prime. We took ratings of enjoyment, mood, and arousal by using Visual Analogue Scales (SI Methods) as the patients listened to preferred pleasant music and unpreferred music. We operationalized the preferred and unpreferred status of the music along a continuum of pleasantness. 5b. Behavioral computer-based experiments of Study 1 were programmed by using E-Prime. Ratings of enjoyment, mood, and arousal were taken as the patients listened to preferred pleasant music and unpreferred music by using Visual Analogue Scales (SI Methods). The preferred and unpreferred status of the music was operationalized along a continuum of pleasantness.

If you choose the point of view of the experimenter, then you may end up with repetitive “we did this” sentences. For many readers, paragraphs with sentences all beginning with “we” may also sound disruptive. So if you choose active sentences, you need to keep the number of “we” subjects to a minimum and vary the beginnings of the sentences [ 6 ].

Interestingly, recent studies have reported that the Materials and Methods section is the only section in research papers in which passive voice predominantly overrides the use of the active voice [ 5 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. For example, Martínez shows a significant drop in active voice use in the Methods sections based on the corpus of 1 million words of experimental full text research articles in the biological sciences [ 7 ]. According to the author, the active voice patterned with “we” is used only as a tool to reveal personal responsibility for the procedural decisions in designing and performing experimental work. This means that while all other sections of the research paper use active voice, passive voice is still the most predominant in Materials and Methods sections.

Writing Materials and Methods sections is a meticulous and time consuming task requiring extreme accuracy and clarity. This is why when you complete your draft, you should ask for as much feedback from your colleagues as possible. Numerous readers of this section will help you identify the missing links and improve the technical style of this section.

Rule 3: Be meticulous and accurate in describing the Materials and Methods. Do not change the point of view within one paragraph.

3.2. writing results section.

For many authors, writing the Results section is more intimidating than writing the Materials and Methods section . If people are interested in your paper, they are interested in your results. That is why it is vital to use all your writing skills to objectively present your key findings in an orderly and logical sequence using illustrative materials and text.

Your Results should be organized into different segments or subsections where each one presents the purpose of the experiment, your experimental approach, data including text and visuals (tables, figures, schematics, algorithms, and formulas), and data commentary. For most journals, your data commentary will include a meaningful summary of the data presented in the visuals and an explanation of the most significant findings. This data presentation should not repeat the data in the visuals, but rather highlight the most important points. In the “standard” research paper approach, your Results section should exclude data interpretation, leaving it for the Discussion section. However, interpretations gradually and secretly creep into research papers: “Reducing the data, generalizing from the data, and highlighting scientific cases are all highly interpretive processes. It should be clear by now that we do not let the data speak for themselves in research reports; in summarizing our results, we interpret them for the reader” [ 10 ]. As a result, many journals including the Journal of Experimental Medicine and the Journal of Clinical Investigation use joint Results/Discussion sections, where results are immediately followed by interpretations.

Another important aspect of this section is to create a comprehensive and supported argument or a well-researched case. This means that you should be selective in presenting data and choose only those experimental details that are essential for your reader to understand your findings. You might have conducted an experiment 20 times and collected numerous records, but this does not mean that you should present all those records in your paper. You need to distinguish your results from your data and be able to discard excessive experimental details that could distract and confuse the reader. However, creating a picture or an argument should not be confused with data manipulation or falsification, which is a willful distortion of data and results. If some of your findings contradict your ideas, you have to mention this and find a plausible explanation for the contradiction.

In addition, your text should not include irrelevant and peripheral information, including overview sentences, as in (6).

6. To show our results, we first introduce all components of experimental system and then describe the outcome of infections.

Indeed, wordiness convolutes your sentences and conceals your ideas from readers. One common source of wordiness is unnecessary intensifiers. Adverbial intensifiers such as “clearly,” “essential,” “quite,” “basically,” “rather,” “fairly,” “really,” and “virtually” not only add verbosity to your sentences, but also lower your results’ credibility. They appeal to the reader’s emotions but lower objectivity, as in the common examples in (7):

7a. Table 3 clearly shows that … 7b. It is obvious from figure 4 that …

Another source of wordiness is nominalizations, i.e., nouns derived from verbs and adjectives paired with weak verbs including “be,” “have,” “do,” “make,” “cause,” “provide,” and “get” and constructions such as “there is/are.”

8a. We tested the hypothesis that there is a disruption of membrane asymmetry. 8b. In this paper we provide an argument that stem cells repopulate injured organs.

In the sentences above, the abstract nominalizations “disruption” and “argument” do not contribute to the clarity of the sentences, but rather clutter them with useless vocabulary that distracts from the meaning. To improve your sentences, avoid unnecessary nominalizations and change passive verbs and constructions into active and direct sentences.

9a. We tested the hypothesis that the membrane asymmetry is disrupted. 9b. In this paper we argue that stem cells repopulate injured organs.

Your Results section is the heart of your paper, representing a year or more of your daily research. So lead your reader through your story by writing direct, concise, and clear sentences.

Rule 4: Be clear, concise, and objective in describing your Results.

3.3. now it is time for your introduction.

Now that you are almost half through drafting your research paper, it is time to update your outline. While describing your Methods and Results, many of you diverged from the original outline and re-focused your ideas. So before you move on to create your Introduction, re-read your Methods and Results sections and change your outline to match your research focus. The updated outline will help you review the general picture of your paper, the topic, the main idea, and the purpose, which are all important for writing your introduction.

The best way to structure your introduction is to follow the three-move approach shown in Table 3 .

Adapted from Swales and Feak [ 11 ].

The moves and information from your outline can help to create your Introduction efficiently and without missing steps. These moves are traffic signs that lead the reader through the road of your ideas. Each move plays an important role in your paper and should be presented with deep thought and care. When you establish the territory, you place your research in context and highlight the importance of your research topic. By finding the niche, you outline the scope of your research problem and enter the scientific dialogue. The final move, “occupying the niche,” is where you explain your research in a nutshell and highlight your paper’s significance. The three moves allow your readers to evaluate their interest in your paper and play a significant role in the paper review process, determining your paper reviewers.

Some academic writers assume that the reader “should follow the paper” to find the answers about your methodology and your findings. As a result, many novice writers do not present their experimental approach and the major findings, wrongly believing that the reader will locate the necessary information later while reading the subsequent sections [ 5 ]. However, this “suspense” approach is not appropriate for scientific writing. To interest the reader, scientific authors should be direct and straightforward and present informative one-sentence summaries of the results and the approach.

Another problem is that writers understate the significance of the Introduction. Many new researchers mistakenly think that all their readers understand the importance of the research question and omit this part. However, this assumption is faulty because the purpose of the section is not to evaluate the importance of the research question in general. The goal is to present the importance of your research contribution and your findings. Therefore, you should be explicit and clear in describing the benefit of the paper.

The Introduction should not be long. Indeed, for most journals, this is a very brief section of about 250 to 600 words, but it might be the most difficult section due to its importance.

Rule 5: Interest your reader in the Introduction section by signalling all its elements and stating the novelty of the work.

3.4. discussion of the results.

For many scientists, writing a Discussion section is as scary as starting a paper. Most of the fear comes from the variation in the section. Since every paper has its unique results and findings, the Discussion section differs in its length, shape, and structure. However, some general principles of writing this section still exist. Knowing these rules, or “moves,” can change your attitude about this section and help you create a comprehensive interpretation of your results.

The purpose of the Discussion section is to place your findings in the research context and “to explain the meaning of the findings and why they are important, without appearing arrogant, condescending, or patronizing” [ 11 ]. The structure of the first two moves is almost a mirror reflection of the one in the Introduction. In the Introduction, you zoom in from general to specific and from the background to your research question; in the Discussion section, you zoom out from the summary of your findings to the research context, as shown in Table 4 .

Adapted from Swales and Feak and Hess [ 11 , 12 ].

The biggest challenge for many writers is the opening paragraph of the Discussion section. Following the moves in Table 1 , the best choice is to start with the study’s major findings that provide the answer to the research question in your Introduction. The most common starting phrases are “Our findings demonstrate . . .,” or “In this study, we have shown that . . .,” or “Our results suggest . . .” In some cases, however, reminding the reader about the research question or even providing a brief context and then stating the answer would make more sense. This is important in those cases where the researcher presents a number of findings or where more than one research question was presented. Your summary of the study’s major findings should be followed by your presentation of the importance of these findings. One of the most frequent mistakes of the novice writer is to assume the importance of his findings. Even if the importance is clear to you, it may not be obvious to your reader. Digesting the findings and their importance to your reader is as crucial as stating your research question.

Another useful strategy is to be proactive in the first move by predicting and commenting on the alternative explanations of the results. Addressing potential doubts will save you from painful comments about the wrong interpretation of your results and will present you as a thoughtful and considerate researcher. Moreover, the evaluation of the alternative explanations might help you create a logical step to the next move of the discussion section: the research context.

The goal of the research context move is to show how your findings fit into the general picture of the current research and how you contribute to the existing knowledge on the topic. This is also the place to discuss any discrepancies and unexpected findings that may otherwise distort the general picture of your paper. Moreover, outlining the scope of your research by showing the limitations, weaknesses, and assumptions is essential and adds modesty to your image as a scientist. However, make sure that you do not end your paper with the problems that override your findings. Try to suggest feasible explanations and solutions.

If your submission does not require a separate Conclusion section, then adding another paragraph about the “take-home message” is a must. This should be a general statement reiterating your answer to the research question and adding its scientific implications, practical application, or advice.

Just as in all other sections of your paper, the clear and precise language and concise comprehensive sentences are vital. However, in addition to that, your writing should convey confidence and authority. The easiest way to illustrate your tone is to use the active voice and the first person pronouns. Accompanied by clarity and succinctness, these tools are the best to convince your readers of your point and your ideas.

Rule 6: Present the principles, relationships, and generalizations in a concise and convincing tone.

4. choosing the best working revision strategies.

Now that you have created the first draft, your attitude toward your writing should have improved. Moreover, you should feel more confident that you are able to accomplish your project and submit your paper within a reasonable timeframe. You also have worked out your writing schedule and followed it precisely. Do not stop ― you are only at the midpoint from your destination. Just as the best and most precious diamond is no more than an unattractive stone recognized only by trained professionals, your ideas and your results may go unnoticed if they are not polished and brushed. Despite your attempts to present your ideas in a logical and comprehensive way, first drafts are frequently a mess. Use the advice of Paul Silvia: “Your first drafts should sound like they were hastily translated from Icelandic by a non-native speaker” [ 2 ]. The degree of your success will depend on how you are able to revise and edit your paper.

The revision can be done at the macrostructure and the microstructure levels [ 13 ]. The macrostructure revision includes the revision of the organization, content, and flow. The microstructure level includes individual words, sentence structure, grammar, punctuation, and spelling.

The best way to approach the macrostructure revision is through the outline of the ideas in your paper. The last time you updated your outline was before writing the Introduction and the Discussion. Now that you have the beginning and the conclusion, you can take a bird’s-eye view of the whole paper. The outline will allow you to see if the ideas of your paper are coherently structured, if your results are logically built, and if the discussion is linked to the research question in the Introduction. You will be able to see if something is missing in any of the sections or if you need to rearrange your information to make your point.

The next step is to revise each of the sections starting from the beginning. Ideally, you should limit yourself to working on small sections of about five pages at a time [ 14 ]. After these short sections, your eyes get used to your writing and your efficiency in spotting problems decreases. When reading for content and organization, you should control your urge to edit your paper for sentence structure and grammar and focus only on the flow of your ideas and logic of your presentation. Experienced researchers tend to make almost three times the number of changes to meaning than novice writers [ 15 , 16 ]. Revising is a difficult but useful skill, which academic writers obtain with years of practice.

In contrast to the macrostructure revision, which is a linear process and is done usually through a detailed outline and by sections, microstructure revision is a non-linear process. While the goal of the macrostructure revision is to analyze your ideas and their logic, the goal of the microstructure editing is to scrutinize the form of your ideas: your paragraphs, sentences, and words. You do not need and are not recommended to follow the order of the paper to perform this type of revision. You can start from the end or from different sections. You can even revise by reading sentences backward, sentence by sentence and word by word.

One of the microstructure revision strategies frequently used during writing center consultations is to read the paper aloud [ 17 ]. You may read aloud to yourself, to a tape recorder, or to a colleague or friend. When reading and listening to your paper, you are more likely to notice the places where the fluency is disrupted and where you stumble because of a very long and unclear sentence or a wrong connector.

Another revision strategy is to learn your common errors and to do a targeted search for them [ 13 ]. All writers have a set of problems that are specific to them, i.e., their writing idiosyncrasies. Remembering these problems is as important for an academic writer as remembering your friends’ birthdays. Create a list of these idiosyncrasies and run a search for these problems using your word processor. If your problem is demonstrative pronouns without summary words, then search for “this/these/those” in your text and check if you used the word appropriately. If you have a problem with intensifiers, then search for “really” or “very” and delete them from the text. The same targeted search can be done to eliminate wordiness. Searching for “there is/are” or “and” can help you avoid the bulky sentences.

The final strategy is working with a hard copy and a pencil. Print a double space copy with font size 14 and re-read your paper in several steps. Try reading your paper line by line with the rest of the text covered with a piece of paper. When you are forced to see only a small portion of your writing, you are less likely to get distracted and are more likely to notice problems. You will end up spotting more unnecessary words, wrongly worded phrases, or unparallel constructions.

After you apply all these strategies, you are ready to share your writing with your friends, colleagues, and a writing advisor in the writing center. Get as much feedback as you can, especially from non-specialists in your field. Patiently listen to what others say to you ― you are not expected to defend your writing or explain what you wanted to say. You may decide what you want to change and how after you receive the feedback and sort it in your head. Even though some researchers make the revision an endless process and can hardly stop after a 14th draft; having from five to seven drafts of your paper is a norm in the sciences. If you can’t stop revising, then set a deadline for yourself and stick to it. Deadlines always help.

Rule 7: Revise your paper at the macrostructure and the microstructure level using different strategies and techniques. Receive feedback and revise again.

5. it is time to submit.

It is late at night again. You are still in your lab finishing revisions and getting ready to submit your paper. You feel happy ― you have finally finished a year’s worth of work. You will submit your paper tomorrow, and regardless of the outcome, you know that you can do it. If one journal does not take your paper, you will take advantage of the feedback and resubmit again. You will have a publication, and this is the most important achievement.

What is even more important is that you have your scheduled writing time that you are going to keep for your future publications, for reading and taking notes, for writing grants, and for reviewing papers. You are not going to lose stamina this time, and you will become a productive scientist. But for now, let’s celebrate the end of the paper.

- Hayes JR. In: The Science of Writing: Theories, Methods, Individual Differences, and Applications. Levy CM, Ransdell SE, editors. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1996. A new framework for understanding cognition and affect in writing; pp. 1–28. [ Google Scholar ]

- Silvia PJ. How to Write a Lot. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Whitesides GM. Whitesides’ Group: Writing a Paper. Adv Mater. 2004; 16 (15):1375–1377. [ Google Scholar ]

- Soto D, Funes MJ, Guzmán-García A, Warbrick T, Rotshtein T, Humphreys GW. Pleasant music overcomes the loss of awareness in patients with visual neglect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009; 106 (14):6011–6016. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hofmann AH. Scientific Writing and Communication. Papers, Proposals, and Presentations. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zeiger M. Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers. 2nd edition. San Francisco, CA: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Martínez I. Native and non-native writers’ use of first person pronouns in the different sections of biology research articles in English. Journal of Second Language Writing. 2005; 14 (3):174–190. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodman L. The Active Voice In Scientific Articles: Frequency And Discourse Functions. Journal Of Technical Writing And Communication. 1994; 24 (3):309–331. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tarone LE, Dwyer S, Gillette S, Icke V. On the use of the passive in two astrophysics journal papers with extensions to other languages and other fields. English for Specific Purposes. 1998; 17 :113–132. [ Google Scholar ]

- Penrose AM, Katz SB. Writing in the sciences: Exploring conventions of scientific discourse. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Swales JM, Feak CB. Academic Writing for Graduate Students. 2nd edition. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hess DR. How to Write an Effective Discussion. Respiratory Care. 2004; 29 (10):1238–1241. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Belcher WL. Writing Your Journal Article in 12 Weeks: a guide to academic publishing success. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Single PB. Demystifying Dissertation Writing: A Streamlined Process of Choice of Topic to Final Text. Virginia: Stylus Publishing LLC; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Faigley L, Witte SP. Analyzing revision. Composition and Communication. 1981; 32 :400–414. [ Google Scholar ]

- Flower LS, Hayes JR, Carey L, Schriver KS, Stratman J. Detection, diagnosis, and the strategies of revision. College Composition and Communication. 1986; 37 (1):16–55. [ Google Scholar ]

- Young BR. In: A Tutor’s Guide: Helping Writers One to One. Rafoth B, editor. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook Publishers; 2005. Can You Proofread This? pp. 140–158. [ Google Scholar ]

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Paper

Definition:

Research Paper is a written document that presents the author’s original research, analysis, and interpretation of a specific topic or issue.

It is typically based on Empirical Evidence, and may involve qualitative or quantitative research methods, or a combination of both. The purpose of a research paper is to contribute new knowledge or insights to a particular field of study, and to demonstrate the author’s understanding of the existing literature and theories related to the topic.

Structure of Research Paper

The structure of a research paper typically follows a standard format, consisting of several sections that convey specific information about the research study. The following is a detailed explanation of the structure of a research paper:

The title page contains the title of the paper, the name(s) of the author(s), and the affiliation(s) of the author(s). It also includes the date of submission and possibly, the name of the journal or conference where the paper is to be published.

The abstract is a brief summary of the research paper, typically ranging from 100 to 250 words. It should include the research question, the methods used, the key findings, and the implications of the results. The abstract should be written in a concise and clear manner to allow readers to quickly grasp the essence of the research.

Introduction

The introduction section of a research paper provides background information about the research problem, the research question, and the research objectives. It also outlines the significance of the research, the research gap that it aims to fill, and the approach taken to address the research question. Finally, the introduction section ends with a clear statement of the research hypothesis or research question.

Literature Review

The literature review section of a research paper provides an overview of the existing literature on the topic of study. It includes a critical analysis and synthesis of the literature, highlighting the key concepts, themes, and debates. The literature review should also demonstrate the research gap and how the current study seeks to address it.

The methods section of a research paper describes the research design, the sample selection, the data collection and analysis procedures, and the statistical methods used to analyze the data. This section should provide sufficient detail for other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the research, using tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data. The findings should be presented in a clear and concise manner, with reference to the research question and hypothesis.

The discussion section of a research paper interprets the findings and discusses their implications for the research question, the literature review, and the field of study. It should also address the limitations of the study and suggest future research directions.

The conclusion section summarizes the main findings of the study, restates the research question and hypothesis, and provides a final reflection on the significance of the research.

The references section provides a list of all the sources cited in the paper, following a specific citation style such as APA, MLA or Chicago.

How to Write Research Paper

You can write Research Paper by the following guide:

- Choose a Topic: The first step is to select a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. Brainstorm ideas and narrow down to a research question that is specific and researchable.

- Conduct a Literature Review: The literature review helps you identify the gap in the existing research and provides a basis for your research question. It also helps you to develop a theoretical framework and research hypothesis.

- Develop a Thesis Statement : The thesis statement is the main argument of your research paper. It should be clear, concise and specific to your research question.

- Plan your Research: Develop a research plan that outlines the methods, data sources, and data analysis procedures. This will help you to collect and analyze data effectively.

- Collect and Analyze Data: Collect data using various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. Analyze data using statistical tools or other qualitative methods.

- Organize your Paper : Organize your paper into sections such as Introduction, Literature Review, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion. Ensure that each section is coherent and follows a logical flow.

- Write your Paper : Start by writing the introduction, followed by the literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. Ensure that your writing is clear, concise, and follows the required formatting and citation styles.

- Edit and Proofread your Paper: Review your paper for grammar and spelling errors, and ensure that it is well-structured and easy to read. Ask someone else to review your paper to get feedback and suggestions for improvement.

- Cite your Sources: Ensure that you properly cite all sources used in your research paper. This is essential for giving credit to the original authors and avoiding plagiarism.

Research Paper Example

Note : The below example research paper is for illustrative purposes only and is not an actual research paper. Actual research papers may have different structures, contents, and formats depending on the field of study, research question, data collection and analysis methods, and other factors. Students should always consult with their professors or supervisors for specific guidelines and expectations for their research papers.

Research Paper Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health among Young Adults

Abstract: This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults. A literature review was conducted to examine the existing research on the topic. A survey was then administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Introduction: Social media has become an integral part of modern life, particularly among young adults. While social media has many benefits, including increased communication and social connectivity, it has also been associated with negative outcomes, such as addiction, cyberbullying, and mental health problems. This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults.

Literature Review: The literature review highlights the existing research on the impact of social media use on mental health. The review shows that social media use is associated with depression, anxiety, stress, and other mental health problems. The review also identifies the factors that contribute to the negative impact of social media, including social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Methods : A survey was administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The survey included questions on social media use, mental health status (measured using the DASS-21), and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and regression analysis.

Results : The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Discussion : The study’s findings suggest that social media use has a negative impact on the mental health of young adults. The study highlights the need for interventions that address the factors contributing to the negative impact of social media, such as social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Conclusion : In conclusion, social media use has a significant impact on the mental health of young adults. The study’s findings underscore the need for interventions that promote healthy social media use and address the negative outcomes associated with social media use. Future research can explore the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health. Additionally, longitudinal studies can investigate the long-term effects of social media use on mental health.

Limitations : The study has some limitations, including the use of self-report measures and a cross-sectional design. The use of self-report measures may result in biased responses, and a cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality.

Implications: The study’s findings have implications for mental health professionals, educators, and policymakers. Mental health professionals can use the findings to develop interventions that address the negative impact of social media use on mental health. Educators can incorporate social media literacy into their curriculum to promote healthy social media use among young adults. Policymakers can use the findings to develop policies that protect young adults from the negative outcomes associated with social media use.

References :

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive medicine reports, 15, 100918.

- Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., … & James, A. E. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among US young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 1-9.

- Van der Meer, T. G., & Verhoeven, J. W. (2017). Social media and its impact on academic performance of students. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 16, 383-398.

Appendix : The survey used in this study is provided below.

Social Media and Mental Health Survey

- How often do you use social media per day?

- Less than 30 minutes

- 30 minutes to 1 hour

- 1 to 2 hours

- 2 to 4 hours

- More than 4 hours

- Which social media platforms do you use?

- Others (Please specify)

- How often do you experience the following on social media?

- Social comparison (comparing yourself to others)

- Cyberbullying

- Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

- Have you ever experienced any of the following mental health problems in the past month?

- Do you think social media use has a positive or negative impact on your mental health?

- Very positive

- Somewhat positive

- Somewhat negative

- Very negative

- In your opinion, which factors contribute to the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Social comparison

- In your opinion, what interventions could be effective in reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Education on healthy social media use

- Counseling for mental health problems caused by social media

- Social media detox programs

- Regulation of social media use

Thank you for your participation!

Applications of Research Paper

Research papers have several applications in various fields, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research papers contribute to the advancement of knowledge by generating new insights, theories, and findings that can inform future research and practice. They help to answer important questions, clarify existing knowledge, and identify areas that require further investigation.

- Informing policy: Research papers can inform policy decisions by providing evidence-based recommendations for policymakers. They can help to identify gaps in current policies, evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, and inform the development of new policies and regulations.

- Improving practice: Research papers can improve practice by providing evidence-based guidance for professionals in various fields, including medicine, education, business, and psychology. They can inform the development of best practices, guidelines, and standards of care that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- Educating students : Research papers are often used as teaching tools in universities and colleges to educate students about research methods, data analysis, and academic writing. They help students to develop critical thinking skills, research skills, and communication skills that are essential for success in many careers.

- Fostering collaboration: Research papers can foster collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and policymakers by providing a platform for sharing knowledge and ideas. They can facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations and partnerships that can lead to innovative solutions to complex problems.

When to Write Research Paper

Research papers are typically written when a person has completed a research project or when they have conducted a study and have obtained data or findings that they want to share with the academic or professional community. Research papers are usually written in academic settings, such as universities, but they can also be written in professional settings, such as research organizations, government agencies, or private companies.

Here are some common situations where a person might need to write a research paper:

- For academic purposes: Students in universities and colleges are often required to write research papers as part of their coursework, particularly in the social sciences, natural sciences, and humanities. Writing research papers helps students to develop research skills, critical thinking skills, and academic writing skills.

- For publication: Researchers often write research papers to publish their findings in academic journals or to present their work at academic conferences. Publishing research papers is an important way to disseminate research findings to the academic community and to establish oneself as an expert in a particular field.

- To inform policy or practice : Researchers may write research papers to inform policy decisions or to improve practice in various fields. Research findings can be used to inform the development of policies, guidelines, and best practices that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- To share new insights or ideas: Researchers may write research papers to share new insights or ideas with the academic or professional community. They may present new theories, propose new research methods, or challenge existing paradigms in their field.

Purpose of Research Paper

The purpose of a research paper is to present the results of a study or investigation in a clear, concise, and structured manner. Research papers are written to communicate new knowledge, ideas, or findings to a specific audience, such as researchers, scholars, practitioners, or policymakers. The primary purposes of a research paper are:

- To contribute to the body of knowledge : Research papers aim to add new knowledge or insights to a particular field or discipline. They do this by reporting the results of empirical studies, reviewing and synthesizing existing literature, proposing new theories, or providing new perspectives on a topic.

- To inform or persuade: Research papers are written to inform or persuade the reader about a particular issue, topic, or phenomenon. They present evidence and arguments to support their claims and seek to persuade the reader of the validity of their findings or recommendations.

- To advance the field: Research papers seek to advance the field or discipline by identifying gaps in knowledge, proposing new research questions or approaches, or challenging existing assumptions or paradigms. They aim to contribute to ongoing debates and discussions within a field and to stimulate further research and inquiry.

- To demonstrate research skills: Research papers demonstrate the author’s research skills, including their ability to design and conduct a study, collect and analyze data, and interpret and communicate findings. They also demonstrate the author’s ability to critically evaluate existing literature, synthesize information from multiple sources, and write in a clear and structured manner.

Characteristics of Research Paper

Research papers have several characteristics that distinguish them from other forms of academic or professional writing. Here are some common characteristics of research papers:

- Evidence-based: Research papers are based on empirical evidence, which is collected through rigorous research methods such as experiments, surveys, observations, or interviews. They rely on objective data and facts to support their claims and conclusions.

- Structured and organized: Research papers have a clear and logical structure, with sections such as introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. They are organized in a way that helps the reader to follow the argument and understand the findings.

- Formal and objective: Research papers are written in a formal and objective tone, with an emphasis on clarity, precision, and accuracy. They avoid subjective language or personal opinions and instead rely on objective data and analysis to support their arguments.

- Citations and references: Research papers include citations and references to acknowledge the sources of information and ideas used in the paper. They use a specific citation style, such as APA, MLA, or Chicago, to ensure consistency and accuracy.

- Peer-reviewed: Research papers are often peer-reviewed, which means they are evaluated by other experts in the field before they are published. Peer-review ensures that the research is of high quality, meets ethical standards, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- Objective and unbiased: Research papers strive to be objective and unbiased in their presentation of the findings. They avoid personal biases or preconceptions and instead rely on the data and analysis to draw conclusions.

Advantages of Research Paper

Research papers have many advantages, both for the individual researcher and for the broader academic and professional community. Here are some advantages of research papers:

- Contribution to knowledge: Research papers contribute to the body of knowledge in a particular field or discipline. They add new information, insights, and perspectives to existing literature and help advance the understanding of a particular phenomenon or issue.

- Opportunity for intellectual growth: Research papers provide an opportunity for intellectual growth for the researcher. They require critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity, which can help develop the researcher’s skills and knowledge.

- Career advancement: Research papers can help advance the researcher’s career by demonstrating their expertise and contributions to the field. They can also lead to new research opportunities, collaborations, and funding.

- Academic recognition: Research papers can lead to academic recognition in the form of awards, grants, or invitations to speak at conferences or events. They can also contribute to the researcher’s reputation and standing in the field.

- Impact on policy and practice: Research papers can have a significant impact on policy and practice. They can inform policy decisions, guide practice, and lead to changes in laws, regulations, or procedures.

- Advancement of society: Research papers can contribute to the advancement of society by addressing important issues, identifying solutions to problems, and promoting social justice and equality.

Limitations of Research Paper

Research papers also have some limitations that should be considered when interpreting their findings or implications. Here are some common limitations of research papers:

- Limited generalizability: Research findings may not be generalizable to other populations, settings, or contexts. Studies often use specific samples or conditions that may not reflect the broader population or real-world situations.

- Potential for bias : Research papers may be biased due to factors such as sample selection, measurement errors, or researcher biases. It is important to evaluate the quality of the research design and methods used to ensure that the findings are valid and reliable.

- Ethical concerns: Research papers may raise ethical concerns, such as the use of vulnerable populations or invasive procedures. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines and obtain informed consent from participants to ensure that the research is conducted in a responsible and respectful manner.

- Limitations of methodology: Research papers may be limited by the methodology used to collect and analyze data. For example, certain research methods may not capture the complexity or nuance of a particular phenomenon, or may not be appropriate for certain research questions.

- Publication bias: Research papers may be subject to publication bias, where positive or significant findings are more likely to be published than negative or non-significant findings. This can skew the overall findings of a particular area of research.

- Time and resource constraints: Research papers may be limited by time and resource constraints, which can affect the quality and scope of the research. Researchers may not have access to certain data or resources, or may be unable to conduct long-term studies due to practical limitations.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

A Beginner's Guide to Starting the Research Process

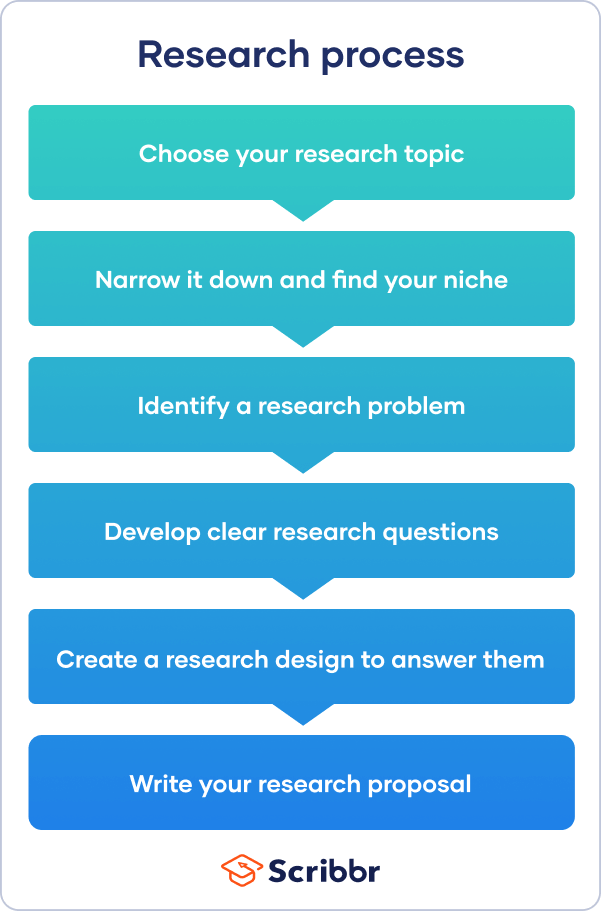

When you have to write a thesis or dissertation , it can be hard to know where to begin, but there are some clear steps you can follow.