An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Yale J Biol Med

- v.84(3); 2011 Sep

Focus: Education — Career Advice

How to write your first research paper.

Writing a research manuscript is an intimidating process for many novice writers in the sciences. One of the stumbling blocks is the beginning of the process and creating the first draft. This paper presents guidelines on how to initiate the writing process and draft each section of a research manuscript. The paper discusses seven rules that allow the writer to prepare a well-structured and comprehensive manuscript for a publication submission. In addition, the author lists different strategies for successful revision. Each of those strategies represents a step in the revision process and should help the writer improve the quality of the manuscript. The paper could be considered a brief manual for publication.

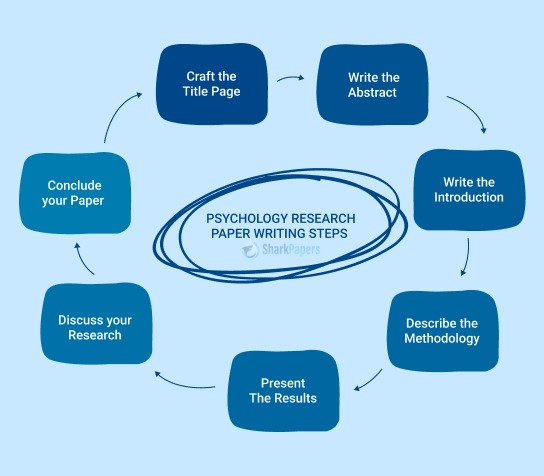

It is late at night. You have been struggling with your project for a year. You generated an enormous amount of interesting data. Your pipette feels like an extension of your hand, and running western blots has become part of your daily routine, similar to brushing your teeth. Your colleagues think you are ready to write a paper, and your lab mates tease you about your “slow” writing progress. Yet days pass, and you cannot force yourself to sit down to write. You have not written anything for a while (lab reports do not count), and you feel you have lost your stamina. How does the writing process work? How can you fit your writing into a daily schedule packed with experiments? What section should you start with? What distinguishes a good research paper from a bad one? How should you revise your paper? These and many other questions buzz in your head and keep you stressed. As a result, you procrastinate. In this paper, I will discuss the issues related to the writing process of a scientific paper. Specifically, I will focus on the best approaches to start a scientific paper, tips for writing each section, and the best revision strategies.

1. Schedule your writing time in Outlook

Whether you have written 100 papers or you are struggling with your first, starting the process is the most difficult part unless you have a rigid writing schedule. Writing is hard. It is a very difficult process of intense concentration and brain work. As stated in Hayes’ framework for the study of writing: “It is a generative activity requiring motivation, and it is an intellectual activity requiring cognitive processes and memory” [ 1 ]. In his book How to Write a Lot: A Practical Guide to Productive Academic Writing , Paul Silvia says that for some, “it’s easier to embalm the dead than to write an article about it” [ 2 ]. Just as with any type of hard work, you will not succeed unless you practice regularly. If you have not done physical exercises for a year, only regular workouts can get you into good shape again. The same kind of regular exercises, or I call them “writing sessions,” are required to be a productive author. Choose from 1- to 2-hour blocks in your daily work schedule and consider them as non-cancellable appointments. When figuring out which blocks of time will be set for writing, you should select the time that works best for this type of work. For many people, mornings are more productive. One Yale University graduate student spent a semester writing from 8 a.m. to 9 a.m. when her lab was empty. At the end of the semester, she was amazed at how much she accomplished without even interrupting her regular lab hours. In addition, doing the hardest task first thing in the morning contributes to the sense of accomplishment during the rest of the day. This positive feeling spills over into our work and life and has a very positive effect on our overall attitude.

Rule 1: Create regular time blocks for writing as appointments in your calendar and keep these appointments.

2. start with an outline.

Now that you have scheduled time, you need to decide how to start writing. The best strategy is to start with an outline. This will not be an outline that you are used to, with Roman numerals for each section and neat parallel listing of topic sentences and supporting points. This outline will be similar to a template for your paper. Initially, the outline will form a structure for your paper; it will help generate ideas and formulate hypotheses. Following the advice of George M. Whitesides, “. . . start with a blank piece of paper, and write down, in any order, all important ideas that occur to you concerning the paper” [ 3 ]. Use Table 1 as a starting point for your outline. Include your visuals (figures, tables, formulas, equations, and algorithms), and list your findings. These will constitute the first level of your outline, which will eventually expand as you elaborate.

The next stage is to add context and structure. Here you will group all your ideas into sections: Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion/Conclusion ( Table 2 ). This step will help add coherence to your work and sift your ideas.

Now that you have expanded your outline, you are ready for the next step: discussing the ideas for your paper with your colleagues and mentor. Many universities have a writing center where graduate students can schedule individual consultations and receive assistance with their paper drafts. Getting feedback during early stages of your draft can save a lot of time. Talking through ideas allows people to conceptualize and organize thoughts to find their direction without wasting time on unnecessary writing. Outlining is the most effective way of communicating your ideas and exchanging thoughts. Moreover, it is also the best stage to decide to which publication you will submit the paper. Many people come up with three choices and discuss them with their mentors and colleagues. Having a list of journal priorities can help you quickly resubmit your paper if your paper is rejected.

Rule 2: Create a detailed outline and discuss it with your mentor and peers.

3. continue with drafts.

After you get enough feedback and decide on the journal you will submit to, the process of real writing begins. Copy your outline into a separate file and expand on each of the points, adding data and elaborating on the details. When you create the first draft, do not succumb to the temptation of editing. Do not slow down to choose a better word or better phrase; do not halt to improve your sentence structure. Pour your ideas into the paper and leave revision and editing for later. As Paul Silvia explains, “Revising while you generate text is like drinking decaffeinated coffee in the early morning: noble idea, wrong time” [ 2 ].

Many students complain that they are not productive writers because they experience writer’s block. Staring at an empty screen is frustrating, but your screen is not really empty: You have a template of your article, and all you need to do is fill in the blanks. Indeed, writer’s block is a logical fallacy for a scientist ― it is just an excuse to procrastinate. When scientists start writing a research paper, they already have their files with data, lab notes with materials and experimental designs, some visuals, and tables with results. All they need to do is scrutinize these pieces and put them together into a comprehensive paper.

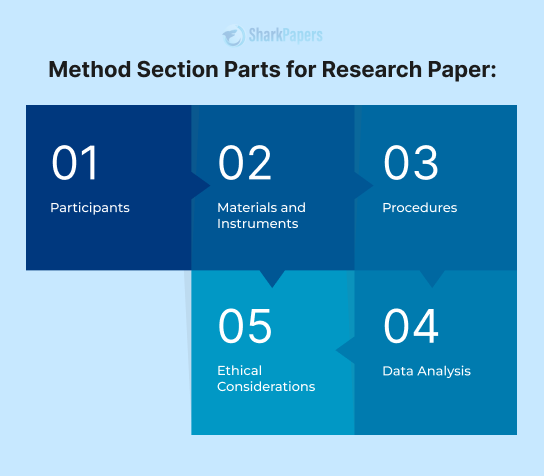

3.1. Starting with Materials and Methods

If you still struggle with starting a paper, then write the Materials and Methods section first. Since you have all your notes, it should not be problematic for you to describe the experimental design and procedures. Your most important goal in this section is to be as explicit as possible by providing enough detail and references. In the end, the purpose of this section is to allow other researchers to evaluate and repeat your work. So do not run into the same problems as the writers of the sentences in (1):

1a. Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation. 1b. To isolate T cells, lymph nodes were collected.

As you can see, crucial pieces of information are missing: the speed of centrifuging your bacteria, the time, and the temperature in (1a); the source of lymph nodes for collection in (b). The sentences can be improved when information is added, as in (2a) and (2b), respectfully:

2a. Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation at 3000g for 15 min at 25°C. 2b. To isolate T cells, mediastinal and mesenteric lymph nodes from Balb/c mice were collected at day 7 after immunization with ovabumin.

If your method has previously been published and is well-known, then you should provide only the literature reference, as in (3a). If your method is unpublished, then you need to make sure you provide all essential details, as in (3b).

3a. Stem cells were isolated, according to Johnson [23]. 3b. Stem cells were isolated using biotinylated carbon nanotubes coated with anti-CD34 antibodies.

Furthermore, cohesion and fluency are crucial in this section. One of the malpractices resulting in disrupted fluency is switching from passive voice to active and vice versa within the same paragraph, as shown in (4). This switching misleads and distracts the reader.

4. Behavioral computer-based experiments of Study 1 were programmed by using E-Prime. We took ratings of enjoyment, mood, and arousal as the patients listened to preferred pleasant music and unpreferred music by using Visual Analogue Scales (SI Methods). The preferred and unpreferred status of the music was operationalized along a continuum of pleasantness [ 4 ].

The problem with (4) is that the reader has to switch from the point of view of the experiment (passive voice) to the point of view of the experimenter (active voice). This switch causes confusion about the performer of the actions in the first and the third sentences. To improve the coherence and fluency of the paragraph above, you should be consistent in choosing the point of view: first person “we” or passive voice [ 5 ]. Let’s consider two revised examples in (5).

5a. We programmed behavioral computer-based experiments of Study 1 by using E-Prime. We took ratings of enjoyment, mood, and arousal by using Visual Analogue Scales (SI Methods) as the patients listened to preferred pleasant music and unpreferred music. We operationalized the preferred and unpreferred status of the music along a continuum of pleasantness. 5b. Behavioral computer-based experiments of Study 1 were programmed by using E-Prime. Ratings of enjoyment, mood, and arousal were taken as the patients listened to preferred pleasant music and unpreferred music by using Visual Analogue Scales (SI Methods). The preferred and unpreferred status of the music was operationalized along a continuum of pleasantness.

If you choose the point of view of the experimenter, then you may end up with repetitive “we did this” sentences. For many readers, paragraphs with sentences all beginning with “we” may also sound disruptive. So if you choose active sentences, you need to keep the number of “we” subjects to a minimum and vary the beginnings of the sentences [ 6 ].

Interestingly, recent studies have reported that the Materials and Methods section is the only section in research papers in which passive voice predominantly overrides the use of the active voice [ 5 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. For example, Martínez shows a significant drop in active voice use in the Methods sections based on the corpus of 1 million words of experimental full text research articles in the biological sciences [ 7 ]. According to the author, the active voice patterned with “we” is used only as a tool to reveal personal responsibility for the procedural decisions in designing and performing experimental work. This means that while all other sections of the research paper use active voice, passive voice is still the most predominant in Materials and Methods sections.

Writing Materials and Methods sections is a meticulous and time consuming task requiring extreme accuracy and clarity. This is why when you complete your draft, you should ask for as much feedback from your colleagues as possible. Numerous readers of this section will help you identify the missing links and improve the technical style of this section.

Rule 3: Be meticulous and accurate in describing the Materials and Methods. Do not change the point of view within one paragraph.

3.2. writing results section.

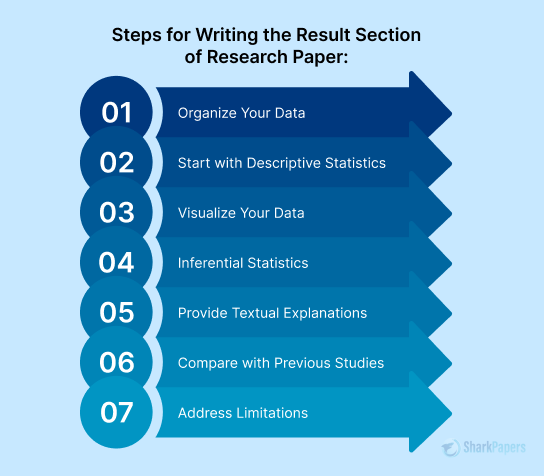

For many authors, writing the Results section is more intimidating than writing the Materials and Methods section . If people are interested in your paper, they are interested in your results. That is why it is vital to use all your writing skills to objectively present your key findings in an orderly and logical sequence using illustrative materials and text.

Your Results should be organized into different segments or subsections where each one presents the purpose of the experiment, your experimental approach, data including text and visuals (tables, figures, schematics, algorithms, and formulas), and data commentary. For most journals, your data commentary will include a meaningful summary of the data presented in the visuals and an explanation of the most significant findings. This data presentation should not repeat the data in the visuals, but rather highlight the most important points. In the “standard” research paper approach, your Results section should exclude data interpretation, leaving it for the Discussion section. However, interpretations gradually and secretly creep into research papers: “Reducing the data, generalizing from the data, and highlighting scientific cases are all highly interpretive processes. It should be clear by now that we do not let the data speak for themselves in research reports; in summarizing our results, we interpret them for the reader” [ 10 ]. As a result, many journals including the Journal of Experimental Medicine and the Journal of Clinical Investigation use joint Results/Discussion sections, where results are immediately followed by interpretations.

Another important aspect of this section is to create a comprehensive and supported argument or a well-researched case. This means that you should be selective in presenting data and choose only those experimental details that are essential for your reader to understand your findings. You might have conducted an experiment 20 times and collected numerous records, but this does not mean that you should present all those records in your paper. You need to distinguish your results from your data and be able to discard excessive experimental details that could distract and confuse the reader. However, creating a picture or an argument should not be confused with data manipulation or falsification, which is a willful distortion of data and results. If some of your findings contradict your ideas, you have to mention this and find a plausible explanation for the contradiction.

In addition, your text should not include irrelevant and peripheral information, including overview sentences, as in (6).

6. To show our results, we first introduce all components of experimental system and then describe the outcome of infections.

Indeed, wordiness convolutes your sentences and conceals your ideas from readers. One common source of wordiness is unnecessary intensifiers. Adverbial intensifiers such as “clearly,” “essential,” “quite,” “basically,” “rather,” “fairly,” “really,” and “virtually” not only add verbosity to your sentences, but also lower your results’ credibility. They appeal to the reader’s emotions but lower objectivity, as in the common examples in (7):

7a. Table 3 clearly shows that … 7b. It is obvious from figure 4 that …

Another source of wordiness is nominalizations, i.e., nouns derived from verbs and adjectives paired with weak verbs including “be,” “have,” “do,” “make,” “cause,” “provide,” and “get” and constructions such as “there is/are.”

8a. We tested the hypothesis that there is a disruption of membrane asymmetry. 8b. In this paper we provide an argument that stem cells repopulate injured organs.

In the sentences above, the abstract nominalizations “disruption” and “argument” do not contribute to the clarity of the sentences, but rather clutter them with useless vocabulary that distracts from the meaning. To improve your sentences, avoid unnecessary nominalizations and change passive verbs and constructions into active and direct sentences.

9a. We tested the hypothesis that the membrane asymmetry is disrupted. 9b. In this paper we argue that stem cells repopulate injured organs.

Your Results section is the heart of your paper, representing a year or more of your daily research. So lead your reader through your story by writing direct, concise, and clear sentences.

Rule 4: Be clear, concise, and objective in describing your Results.

3.3. now it is time for your introduction.

Now that you are almost half through drafting your research paper, it is time to update your outline. While describing your Methods and Results, many of you diverged from the original outline and re-focused your ideas. So before you move on to create your Introduction, re-read your Methods and Results sections and change your outline to match your research focus. The updated outline will help you review the general picture of your paper, the topic, the main idea, and the purpose, which are all important for writing your introduction.

The best way to structure your introduction is to follow the three-move approach shown in Table 3 .

Adapted from Swales and Feak [ 11 ].

The moves and information from your outline can help to create your Introduction efficiently and without missing steps. These moves are traffic signs that lead the reader through the road of your ideas. Each move plays an important role in your paper and should be presented with deep thought and care. When you establish the territory, you place your research in context and highlight the importance of your research topic. By finding the niche, you outline the scope of your research problem and enter the scientific dialogue. The final move, “occupying the niche,” is where you explain your research in a nutshell and highlight your paper’s significance. The three moves allow your readers to evaluate their interest in your paper and play a significant role in the paper review process, determining your paper reviewers.

Some academic writers assume that the reader “should follow the paper” to find the answers about your methodology and your findings. As a result, many novice writers do not present their experimental approach and the major findings, wrongly believing that the reader will locate the necessary information later while reading the subsequent sections [ 5 ]. However, this “suspense” approach is not appropriate for scientific writing. To interest the reader, scientific authors should be direct and straightforward and present informative one-sentence summaries of the results and the approach.

Another problem is that writers understate the significance of the Introduction. Many new researchers mistakenly think that all their readers understand the importance of the research question and omit this part. However, this assumption is faulty because the purpose of the section is not to evaluate the importance of the research question in general. The goal is to present the importance of your research contribution and your findings. Therefore, you should be explicit and clear in describing the benefit of the paper.

The Introduction should not be long. Indeed, for most journals, this is a very brief section of about 250 to 600 words, but it might be the most difficult section due to its importance.

Rule 5: Interest your reader in the Introduction section by signalling all its elements and stating the novelty of the work.

3.4. discussion of the results.

For many scientists, writing a Discussion section is as scary as starting a paper. Most of the fear comes from the variation in the section. Since every paper has its unique results and findings, the Discussion section differs in its length, shape, and structure. However, some general principles of writing this section still exist. Knowing these rules, or “moves,” can change your attitude about this section and help you create a comprehensive interpretation of your results.

The purpose of the Discussion section is to place your findings in the research context and “to explain the meaning of the findings and why they are important, without appearing arrogant, condescending, or patronizing” [ 11 ]. The structure of the first two moves is almost a mirror reflection of the one in the Introduction. In the Introduction, you zoom in from general to specific and from the background to your research question; in the Discussion section, you zoom out from the summary of your findings to the research context, as shown in Table 4 .

Adapted from Swales and Feak and Hess [ 11 , 12 ].

The biggest challenge for many writers is the opening paragraph of the Discussion section. Following the moves in Table 1 , the best choice is to start with the study’s major findings that provide the answer to the research question in your Introduction. The most common starting phrases are “Our findings demonstrate . . .,” or “In this study, we have shown that . . .,” or “Our results suggest . . .” In some cases, however, reminding the reader about the research question or even providing a brief context and then stating the answer would make more sense. This is important in those cases where the researcher presents a number of findings or where more than one research question was presented. Your summary of the study’s major findings should be followed by your presentation of the importance of these findings. One of the most frequent mistakes of the novice writer is to assume the importance of his findings. Even if the importance is clear to you, it may not be obvious to your reader. Digesting the findings and their importance to your reader is as crucial as stating your research question.

Another useful strategy is to be proactive in the first move by predicting and commenting on the alternative explanations of the results. Addressing potential doubts will save you from painful comments about the wrong interpretation of your results and will present you as a thoughtful and considerate researcher. Moreover, the evaluation of the alternative explanations might help you create a logical step to the next move of the discussion section: the research context.

The goal of the research context move is to show how your findings fit into the general picture of the current research and how you contribute to the existing knowledge on the topic. This is also the place to discuss any discrepancies and unexpected findings that may otherwise distort the general picture of your paper. Moreover, outlining the scope of your research by showing the limitations, weaknesses, and assumptions is essential and adds modesty to your image as a scientist. However, make sure that you do not end your paper with the problems that override your findings. Try to suggest feasible explanations and solutions.

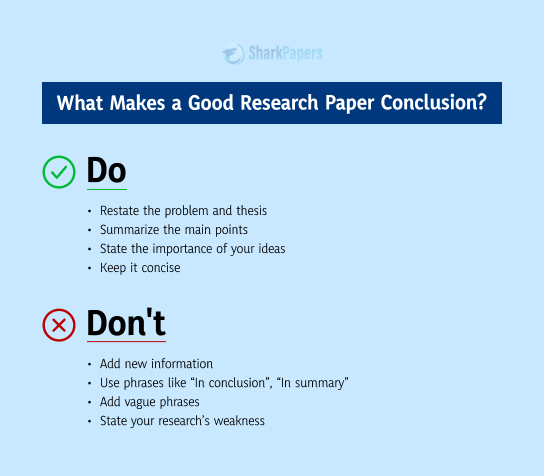

If your submission does not require a separate Conclusion section, then adding another paragraph about the “take-home message” is a must. This should be a general statement reiterating your answer to the research question and adding its scientific implications, practical application, or advice.

Just as in all other sections of your paper, the clear and precise language and concise comprehensive sentences are vital. However, in addition to that, your writing should convey confidence and authority. The easiest way to illustrate your tone is to use the active voice and the first person pronouns. Accompanied by clarity and succinctness, these tools are the best to convince your readers of your point and your ideas.

Rule 6: Present the principles, relationships, and generalizations in a concise and convincing tone.

4. choosing the best working revision strategies.

Now that you have created the first draft, your attitude toward your writing should have improved. Moreover, you should feel more confident that you are able to accomplish your project and submit your paper within a reasonable timeframe. You also have worked out your writing schedule and followed it precisely. Do not stop ― you are only at the midpoint from your destination. Just as the best and most precious diamond is no more than an unattractive stone recognized only by trained professionals, your ideas and your results may go unnoticed if they are not polished and brushed. Despite your attempts to present your ideas in a logical and comprehensive way, first drafts are frequently a mess. Use the advice of Paul Silvia: “Your first drafts should sound like they were hastily translated from Icelandic by a non-native speaker” [ 2 ]. The degree of your success will depend on how you are able to revise and edit your paper.

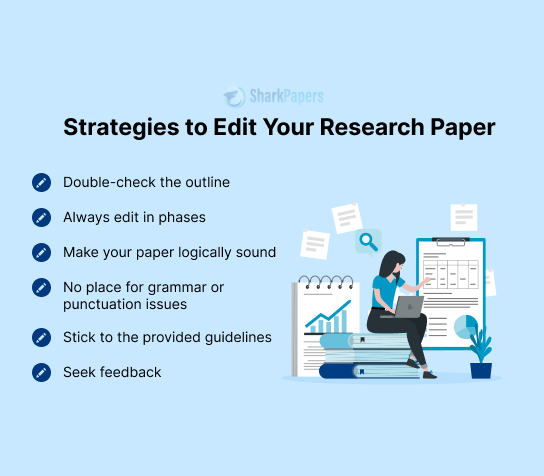

The revision can be done at the macrostructure and the microstructure levels [ 13 ]. The macrostructure revision includes the revision of the organization, content, and flow. The microstructure level includes individual words, sentence structure, grammar, punctuation, and spelling.

The best way to approach the macrostructure revision is through the outline of the ideas in your paper. The last time you updated your outline was before writing the Introduction and the Discussion. Now that you have the beginning and the conclusion, you can take a bird’s-eye view of the whole paper. The outline will allow you to see if the ideas of your paper are coherently structured, if your results are logically built, and if the discussion is linked to the research question in the Introduction. You will be able to see if something is missing in any of the sections or if you need to rearrange your information to make your point.

The next step is to revise each of the sections starting from the beginning. Ideally, you should limit yourself to working on small sections of about five pages at a time [ 14 ]. After these short sections, your eyes get used to your writing and your efficiency in spotting problems decreases. When reading for content and organization, you should control your urge to edit your paper for sentence structure and grammar and focus only on the flow of your ideas and logic of your presentation. Experienced researchers tend to make almost three times the number of changes to meaning than novice writers [ 15 , 16 ]. Revising is a difficult but useful skill, which academic writers obtain with years of practice.

In contrast to the macrostructure revision, which is a linear process and is done usually through a detailed outline and by sections, microstructure revision is a non-linear process. While the goal of the macrostructure revision is to analyze your ideas and their logic, the goal of the microstructure editing is to scrutinize the form of your ideas: your paragraphs, sentences, and words. You do not need and are not recommended to follow the order of the paper to perform this type of revision. You can start from the end or from different sections. You can even revise by reading sentences backward, sentence by sentence and word by word.

One of the microstructure revision strategies frequently used during writing center consultations is to read the paper aloud [ 17 ]. You may read aloud to yourself, to a tape recorder, or to a colleague or friend. When reading and listening to your paper, you are more likely to notice the places where the fluency is disrupted and where you stumble because of a very long and unclear sentence or a wrong connector.

Another revision strategy is to learn your common errors and to do a targeted search for them [ 13 ]. All writers have a set of problems that are specific to them, i.e., their writing idiosyncrasies. Remembering these problems is as important for an academic writer as remembering your friends’ birthdays. Create a list of these idiosyncrasies and run a search for these problems using your word processor. If your problem is demonstrative pronouns without summary words, then search for “this/these/those” in your text and check if you used the word appropriately. If you have a problem with intensifiers, then search for “really” or “very” and delete them from the text. The same targeted search can be done to eliminate wordiness. Searching for “there is/are” or “and” can help you avoid the bulky sentences.

The final strategy is working with a hard copy and a pencil. Print a double space copy with font size 14 and re-read your paper in several steps. Try reading your paper line by line with the rest of the text covered with a piece of paper. When you are forced to see only a small portion of your writing, you are less likely to get distracted and are more likely to notice problems. You will end up spotting more unnecessary words, wrongly worded phrases, or unparallel constructions.

After you apply all these strategies, you are ready to share your writing with your friends, colleagues, and a writing advisor in the writing center. Get as much feedback as you can, especially from non-specialists in your field. Patiently listen to what others say to you ― you are not expected to defend your writing or explain what you wanted to say. You may decide what you want to change and how after you receive the feedback and sort it in your head. Even though some researchers make the revision an endless process and can hardly stop after a 14th draft; having from five to seven drafts of your paper is a norm in the sciences. If you can’t stop revising, then set a deadline for yourself and stick to it. Deadlines always help.

Rule 7: Revise your paper at the macrostructure and the microstructure level using different strategies and techniques. Receive feedback and revise again.

5. it is time to submit.

It is late at night again. You are still in your lab finishing revisions and getting ready to submit your paper. You feel happy ― you have finally finished a year’s worth of work. You will submit your paper tomorrow, and regardless of the outcome, you know that you can do it. If one journal does not take your paper, you will take advantage of the feedback and resubmit again. You will have a publication, and this is the most important achievement.

What is even more important is that you have your scheduled writing time that you are going to keep for your future publications, for reading and taking notes, for writing grants, and for reviewing papers. You are not going to lose stamina this time, and you will become a productive scientist. But for now, let’s celebrate the end of the paper.

- Hayes JR. In: The Science of Writing: Theories, Methods, Individual Differences, and Applications. Levy CM, Ransdell SE, editors. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1996. A new framework for understanding cognition and affect in writing; pp. 1–28. [ Google Scholar ]

- Silvia PJ. How to Write a Lot. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Whitesides GM. Whitesides’ Group: Writing a Paper. Adv Mater. 2004; 16 (15):1375–1377. [ Google Scholar ]

- Soto D, Funes MJ, Guzmán-García A, Warbrick T, Rotshtein T, Humphreys GW. Pleasant music overcomes the loss of awareness in patients with visual neglect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009; 106 (14):6011–6016. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hofmann AH. Scientific Writing and Communication. Papers, Proposals, and Presentations. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zeiger M. Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers. 2nd edition. San Francisco, CA: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Martínez I. Native and non-native writers’ use of first person pronouns in the different sections of biology research articles in English. Journal of Second Language Writing. 2005; 14 (3):174–190. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodman L. The Active Voice In Scientific Articles: Frequency And Discourse Functions. Journal Of Technical Writing And Communication. 1994; 24 (3):309–331. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tarone LE, Dwyer S, Gillette S, Icke V. On the use of the passive in two astrophysics journal papers with extensions to other languages and other fields. English for Specific Purposes. 1998; 17 :113–132. [ Google Scholar ]

- Penrose AM, Katz SB. Writing in the sciences: Exploring conventions of scientific discourse. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Swales JM, Feak CB. Academic Writing for Graduate Students. 2nd edition. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hess DR. How to Write an Effective Discussion. Respiratory Care. 2004; 29 (10):1238–1241. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Belcher WL. Writing Your Journal Article in 12 Weeks: a guide to academic publishing success. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Single PB. Demystifying Dissertation Writing: A Streamlined Process of Choice of Topic to Final Text. Virginia: Stylus Publishing LLC; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Faigley L, Witte SP. Analyzing revision. Composition and Communication. 1981; 32 :400–414. [ Google Scholar ]

- Flower LS, Hayes JR, Carey L, Schriver KS, Stratman J. Detection, diagnosis, and the strategies of revision. College Composition and Communication. 1986; 37 (1):16–55. [ Google Scholar ]

- Young BR. In: A Tutor’s Guide: Helping Writers One to One. Rafoth B, editor. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook Publishers; 2005. Can You Proofread This? pp. 140–158. [ Google Scholar ]

How to Write a Biology Research Paper: A Comprehensive Guide

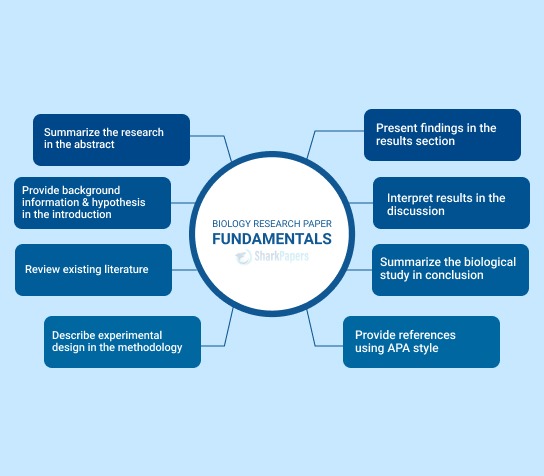

In academic circles, mastering the art of writing a biology research paper is imperative. This guide offers you a holistic approach to tackle this challenging task. You'll find detailed insights into planning, structuring, and executing your paper, ensuring that you engage your audience with well-researched, credible data. From the initial steps to the final submission, we'll walk you through each process, dissecting the complex parts to provide a manageable roadmap. We’ll cover topics from starting a biology research paper to its outline, body, and conclusion, all while keeping your academic goals in focus. So let's dive in!

How to Start a Biology Research Paper

When commencing a biology research paper, your first task is to select a topic that interests both you and your readers. The topic should be relevant to the study of biology and present opportunities for you to showcase your findings. A well-chosen topic will make the research process smoother and help you craft a paper that resonates with your audience. Remember, the success of your paper largely depends on your initial groundwork, so make it count. Check out recent science journals for research publication inspiration.

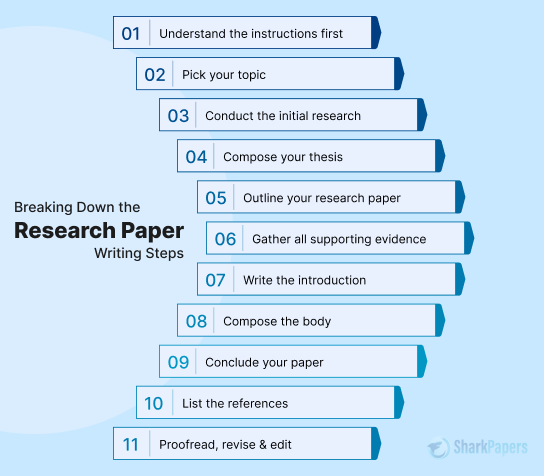

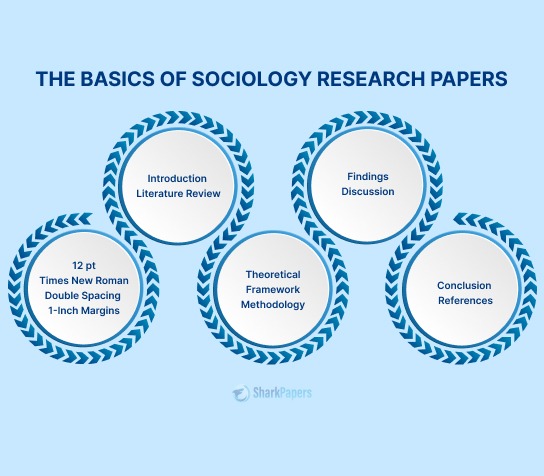

How to Structure a Biology Research Paper

After picking your topic, the next step is planning the structure of your biology research paper. The structure should comprise of an introduction, body, and conclusion. It's crucial to create an outline before diving into the writing process, as this helps to organize your thoughts and findings. The outline should cover each section of the paper, from the introduction to the conclusion, including the arguments, experimental procedures, and vital information you intend to include.

Understanding the Biology Research Paper Outline

A biology research paper outline serves as your blueprint. It guides you through the writing process, making sure you don't drift off-topic. Your outline should include the thesis statement, the main points for your arguments, the experimental procedures to be followed, and the data you'll collect. It's also the space to decide how you'll present your research findings to your readers in a comprehensible manner. With a well-prepared outline, you'll find that writing your paper becomes significantly easier.

How to End a Biology Research Paper

Concluding a biology research paper effectively involves summarizing your key findings and stating their implications. It's not just about restating what you've already said; it's a final opportunity to leave a lasting impression on your audience. Your conclusion should reiterate your thesis statement and provide a summary of the key points made in the paper's body. It's essential to also discuss the significance of your findings and how they contribute to existing scientific research.

Submitting to Science Journals for Research Publication

After completing your paper, the final step is to submit it to reputable science journals for research publication. Peer-reviewed journals are the gold standard in the scientific community. Your paper will undergo rigorous review, ensuring it meets the academic and scientific criteria of the journal. The process may require revisions, but don't be disheartened. These are steps to ensure that your research is robust, accurate, and worthy of academic recognition.

A Comprehensive Research

The term 'comprehensive research' implies the exhaustive and detailed nature of your study. Make sure your research is thorough and leaves no stone unturned. This will lend credibility and depth to your biology research paper, enhancing its value in academic circles.

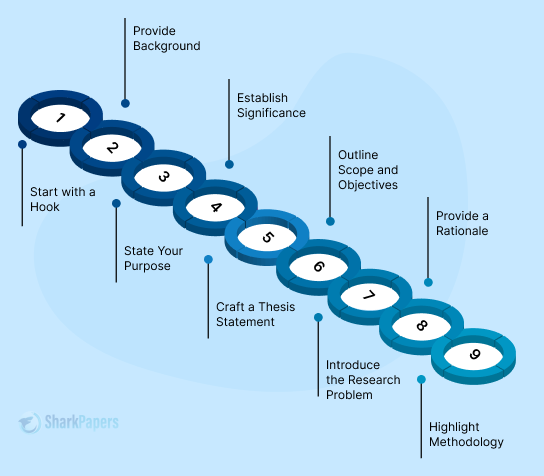

Introduction of Biology Research Paper

The introduction sets the tone for your biology research paper. It's where you outline the objective, the research question, and the thesis statement. Make it engaging enough to captivate your readers but academic enough to convey the paper’s significance.

Body of Biology Research Paper

The body is where you present your findings, experimental procedures, and analysis. Structure it logically, using headings and subheadings to guide the reader through your arguments and data. Consistency and clarity are key to keeping your audience engaged.

Conclusion of Biology Research Paper

In your conclusion, make sure to tie all your findings back to your research question and thesis statement. A compelling conclusion will summarize the research, restate the importance of your study, and suggest potential avenues for future research.

Dos and Don'ts

- Do conduct a thorough literature review.

- Do create an exhaustive outline.

- Don't use jargon without explaining it.

- Don't ignore formatting guidelines.

Final Thoughts

Completing a biology research paper is a complex yet rewarding academic exercise. It's a chance to contribute to the scientific community and showcase your ability to conduct research, analyze data, and articulate your findings. With careful planning, diligent research, and thoughtful writing, you can create a paper that not only meets academic standards but also serves as a meaningful addition to existing scientific literature.

Useful Resources: https://techthanos.com/ways-of-using-chatgpt-in-the-classroom/

Loading metrics

Open Access

Ten simple rules for structuring papers

Affiliations Optimize Science, Mill Valley, California, United States of America, Janelia Research Campus, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Ashburn, Virginia, United States of America

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, United States of America

- Brett Mensh,

- Konrad Kording

Published: September 28, 2017

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005619

- See the preprint

- Reader Comments

9 Nov 2017: The PLOS Computational Biology Staff (2017) Correction: Ten simple rules for structuring papers. PLOS Computational Biology 13(11): e1005830. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005830 View correction

Citation: Mensh B, Kording K (2017) Ten simple rules for structuring papers. PLoS Comput Biol 13(9): e1005619. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005619

Editor: Scott Markel, Dassault Systemes BIOVIA, UNITED STATES

Copyright: © 2017 Mensh, Kording. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Good scientific writing is essential to career development and to the progress of science. A well-structured manuscript allows readers and reviewers to get excited about the subject matter, to understand and verify the paper’s contributions, and to integrate these contributions into a broader context. However, many scientists struggle with producing high-quality manuscripts and are typically untrained in paper writing. Focusing on how readers consume information, we present a set of ten simple rules to help you communicate the main idea of your paper. These rules are designed to make your paper more influential and the process of writing more efficient and pleasurable.

Introduction

Writing and reading papers are key skills for scientists. Indeed, success at publishing is used to evaluate scientists [ 1 ] and can help predict their future success [ 2 ]. In the production and consumption of papers, multiple parties are involved, each having their own motivations and priorities. The editors want to make sure that the paper is significant, and the reviewers want to determine whether the conclusions are justified by the results. The reader wants to quickly understand the conceptual conclusions of the paper before deciding whether to dig into the details, and the writer wants to convey the important contributions to the broadest audience possible while convincing the specialist that the findings are credible. You can facilitate all of these goals by structuring the paper well at multiple scales—spanning the sentence, paragraph, section, and document.

Clear communication is also crucial for the broader scientific enterprise because “concept transfer” is a rate-limiting step in scientific cross-pollination. This is particularly true in the biological sciences and other fields that comprise a vast web of highly interconnected sub-disciplines. As scientists become increasingly specialized, it becomes more important (and difficult) to strengthen the conceptual links. Communication across disciplinary boundaries can only work when manuscripts are readable, credible, and memorable.

The claim that gives significance to your work has to be supported by data and by a logic that gives it credibility. Without carefully planning the paper’s logic, writers will often be missing data or missing logical steps on the way to the conclusion. While these lapses are beyond our scope, your scientific logic must be crystal clear to powerfully make your claim.

Here we present ten simple rules for structuring papers. The first four rules are principles that apply to all the parts of a paper and further to other forms of communication such as grants and posters. The next four rules deal with the primary goals of each of the main parts of papers. The final two rules deliver guidance on the process—heuristics for efficiently constructing manuscripts.

Principles (Rules 1–4)

Writing is communication. Thus, the reader’s experience is of primary importance, and all writing serves this goal. When you write, you should constantly have your reader in mind. These four rules help you to avoid losing your reader.

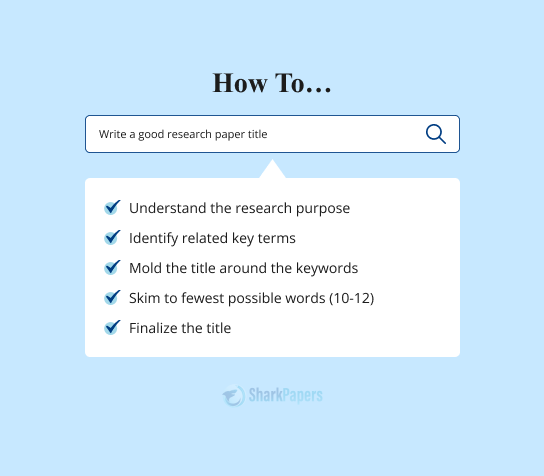

Rule 1: Focus your paper on a central contribution, which you communicate in the title

Your communication efforts are successful if readers can still describe the main contribution of your paper to their colleagues a year after reading it. Although it is clear that a paper often needs to communicate a number of innovations on the way to its final message, it does not pay to be greedy. Focus on a single message; papers that simultaneously focus on multiple contributions tend to be less convincing about each and are therefore less memorable.

The most important element of a paper is the title—think of the ratio of the number of titles you read to the number of papers you read. The title is typically the first element a reader encounters, so its quality [ 3 ] determines whether the reader will invest time in reading the abstract.

The title not only transmits the paper’s central contribution but can also serve as a constant reminder (to you) to focus the text on transmitting that idea. Science is, after all, the abstraction of simple principles from complex data. The title is the ultimate refinement of the paper’s contribution. Thinking about the title early—and regularly returning to hone it—can help not only the writing of the paper but also the process of designing experiments or developing theories.

This Rule of One is the most difficult rule to optimally implement because it comes face-to-face with the key challenge of science, which is to make the claim and/or model as simple as the data and logic can support but no simpler. In the end, your struggle to find this balance may appropriately result in “one contribution” that is multifaceted. For example, a technology paper may describe both its new technology and a biological result using it; the bridge that unifies these two facets is a clear description of how the new technology can be used to do new biology.

Rule 2: Write for flesh-and-blood human beings who do not know your work

Because you are the world’s leading expert at exactly what you are doing, you are also the world’s least qualified person to judge your writing from the perspective of the naïve reader. The majority of writing mistakes stem from this predicament. Think like a designer—for each element, determine the impact that you want to have on people and then strive to achieve that objective [ 4 ]. Try to think through the paper like a naïve reader who must first be made to care about the problem you are addressing (see Rule 6) and then will want to understand your answer with minimal effort.

Define technical terms clearly because readers can become frustrated when they encounter a word that they don’t understand. Avoid abbreviations and acronyms so that readers do not have to go back to earlier sections to identify them.

The vast knowledge base of human psychology is useful in paper writing. For example, people have working memory constraints in that they can only remember a small number of items and are better at remembering the beginning and the end of a list than the middle [ 5 ]. Do your best to minimize the number of loose threads that the reader has to keep in mind at any one time.

Rule 3: Stick to the context-content-conclusion (C-C-C) scheme

The vast majority of popular (i.e., memorable and re-tellable) stories have a structure with a discernible beginning, a well-defined body, and an end. The beginning sets up the context for the story, while the body (content) advances the story towards an ending in which the problems find their conclusions. This structure reduces the chance that the reader will wonder “Why was I told that?” (if the context is missing) or “So what?” (if the conclusion is missing).

There are many ways of telling a story. Mostly, they differ in how well they serve a patient reader versus an impatient one [ 6 ]. The impatient reader needs to be engaged quickly; this can be accomplished by presenting the most exciting content first (e.g., as seen in news articles). The C-C-C scheme that we advocate serves a more patient reader who is willing to spend the time to get oriented with the context. A consequent disadvantage of C-C-C is that it may not optimally engage the impatient reader. This disadvantage is mitigated by the fact that the structure of scientific articles, specifically the primacy of the title and abstract, already forces the content to be revealed quickly. Thus, a reader who proceeds to the introduction is likely engaged enough to have the patience to absorb the context. Furthermore, one hazard of excessive “content first” story structures in science is that you may generate skepticism in the reader because they may be missing an important piece of context that makes your claim more credible. For these reasons, we advocate C-C-C as a “default” scientific story structure.

The C-C-C scheme defines the structure of the paper on multiple scales. At the whole-paper scale, the introduction sets the context, the results are the content, and the discussion brings home the conclusion. Applying C-C-C at the paragraph scale, the first sentence defines the topic or context, the body hosts the novel content put forth for the reader’s consideration, and the last sentence provides the conclusion to be remembered.

Deviating from the C-C-C structure often leads to papers that are hard to read, but writers often do so because of their own autobiographical context. During our everyday lives as scientists, we spend a majority of our time producing content and a minority amidst a flurry of other activities. We run experiments, develop the exposition of available literature, and combine thoughts using the magic of human cognition. It is natural to want to record these efforts on paper and structure a paper chronologically. But for our readers, most details of our activities are extraneous. They do not care about the chronological path by which you reached a result; they just care about the ultimate claim and the logic supporting it (see Rule 7). Thus, all our work must be reformatted to provide a context that makes our material meaningful and a conclusion that helps the reader to understand and remember it.

Rule 4: Optimize your logical flow by avoiding zig-zag and using parallelism

Avoiding zig-zag..

Only the central idea of the paper should be touched upon multiple times. Otherwise, each subject should be covered in only one place in order to minimize the number of subject changes. Related sentences or paragraphs should be strung together rather than interrupted by unrelated material. Ideas that are similar, such as two reasons why we should believe something, should come one immediately after the other.

Using parallelism.

Similarly, across consecutive paragraphs or sentences, parallel messages should be communicated with parallel form. Parallelism makes it easier to read the text because the reader is familiar with the structure. For example, if we have three independent reasons why we prefer one interpretation of a result over another, it is helpful to communicate them with the same syntax so that this syntax becomes transparent to the reader, which allows them to focus on the content. There is nothing wrong with using the same word multiple times in a sentence or paragraph. Resist the temptation to use a different word to refer to the same concept—doing so makes readers wonder if the second word has a slightly different meaning.

The components of a paper (Rules 5–8)

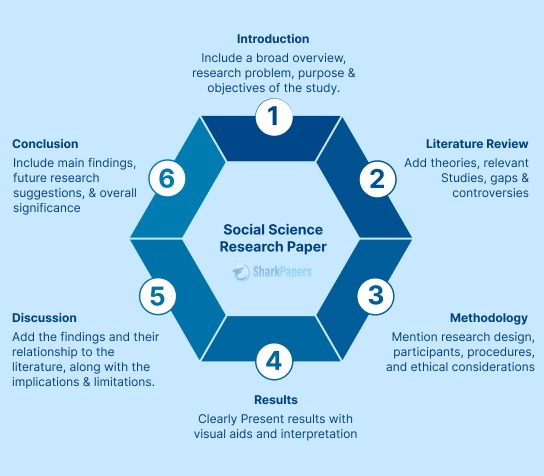

The individual parts of a paper—abstract, introduction, results, and discussion—have different objectives, and thus they each apply the C-C-C structure a little differently in order to achieve their objectives. We will discuss these specialized structures in this section and summarize them in Fig 1 .

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Note that the abstract is special in that it contains all three elements (Context, Content, and Conclusion), thus comprising all three colors.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005619.g001

Rule 5: Tell a complete story in the abstract

The abstract is, for most readers, the only part of the paper that will be read. This means that the abstract must convey the entire message of the paper effectively. To serve this purpose, the abstract’s structure is highly conserved. Each of the C-C-C elements is detailed below.

The context must communicate to the reader what gap the paper will fill. The first sentence orients the reader by introducing the broader field in which the particular research is situated. Then, this context is narrowed until it lands on the open question that the research answered. A successful context section sets the stage for distinguishing the paper’s contributions from the current state of the art by communicating what is missing in the literature (i.e., the specific gap) and why that matters (i.e., the connection between the specific gap and the broader context that the paper opened with).

The content (“Here we”) first describes the novel method or approach that you used to fill the gap or question. Then you present the meat—your executive summary of the results.

Finally, the conclusion interprets the results to answer the question that was posed at the end of the context section. There is often a second part to the conclusion section that highlights how this conclusion moves the broader field forward (i.e., “broader significance”). This is particularly true for more “general” journals with a broad readership.

This structure helps you avoid the most common mistake with the abstract, which is to talk about results before the reader is ready to understand them. Good abstracts usually take many iterations of refinement to make sure the results fill the gap like a key fits its lock. The broad-narrow-broad structure allows you to communicate with a wider readership (through breadth) while maintaining the credibility of your claim (which is always based on a finite or narrow set of results).

Rule 6: Communicate why the paper matters in the introduction

The introduction highlights the gap that exists in current knowledge or methods and why it is important. This is usually done by a set of progressively more specific paragraphs that culminate in a clear exposition of what is lacking in the literature, followed by a paragraph summarizing what the paper does to fill that gap.

As an example of the progression of gaps, a first paragraph may explain why understanding cell differentiation is an important topic and that the field has not yet solved what triggers it (a field gap). A second paragraph may explain what is unknown about the differentiation of a specific cell type, such as astrocytes (a subfield gap). A third may provide clues that a particular gene might drive astrocytic differentiation and then state that this hypothesis is untested (the gap within the subfield that you will fill). The gap statement sets the reader’s expectation for what the paper will deliver.

The structure of each introduction paragraph (except the last) serves the goal of developing the gap. Each paragraph first orients the reader to the topic (a context sentence or two) and then explains the “knowns” in the relevant literature (content) before landing on the critical “unknown” (conclusion) that makes the paper matter at the relevant scale. Along the path, there are often clues given about the mystery behind the gaps; these clues lead to the untested hypothesis or undeveloped method of the paper and give the reader hope that the mystery is solvable. The introduction should not contain a broad literature review beyond the motivation of the paper. This gap-focused structure makes it easy for experienced readers to evaluate the potential importance of a paper—they only need to assess the importance of the claimed gap.

The last paragraph of the introduction is special: it compactly summarizes the results, which fill the gap you just established. It differs from the abstract in the following ways: it does not need to present the context (which has just been given), it is somewhat more specific about the results, and it only briefly previews the conclusion of the paper, if at all.

Rule 7: Deliver the results as a sequence of statements, supported by figures, that connect logically to support the central contribution

The results section needs to convince the reader that the central claim is supported by data and logic. Every scientific argument has its own particular logical structure, which dictates the sequence in which its elements should be presented.

For example, a paper may set up a hypothesis, verify that a method for measurement is valid in the system under study, and then use the measurement to disprove the hypothesis. Alternatively, a paper may set up multiple alternative (and mutually exclusive) hypotheses and then disprove all but one to provide evidence for the remaining interpretation. The fabric of the argument will contain controls and methods where they are needed for the overall logic.

In the outlining phase of paper preparation (see Rule 9), sketch out the logical structure of how your results support your claim and convert this into a sequence of declarative statements that become the headers of subsections within the results section (and/or the titles of figures). Most journals allow this type of formatting, but if your chosen journal does not, these headers are still useful during the writing phase and can either be adapted to serve as introductory sentences to your paragraphs or deleted before submission. Such a clear progression of logical steps makes the paper easy to follow.

Figures, their titles, and legends are particularly important because they show the most objective support (data) of the steps that culminate in the paper’s claim. Moreover, figures are often viewed by readers who skip directly from the abstract in order to save time. Thus, the title of the figure should communicate the conclusion of the analysis, and the legend should explain how it was done. Figure making is an art unto itself; the Edward Tufte books remain the gold standard for learning this craft [ 7 , 8 ].

The first results paragraph is special in that it typically summarizes the overall approach to the problem outlined in the introduction, along with any key innovative methods that were developed. Most readers do not read the methods, so this paragraph gives them the gist of the methods that were used.

Each subsequent paragraph in the results section starts with a sentence or two that set up the question that the paragraph answers, such as the following: “To verify that there are no artifacts…,” “What is the test-retest reliability of our measure?,” or “We next tested whether Ca 2+ flux through L-type Ca 2+ channels was involved.” The middle of the paragraph presents data and logic that pertain to the question, and the paragraph ends with a sentence that answers the question. For example, it may conclude that none of the potential artifacts were detected. This structure makes it easy for experienced readers to fact-check a paper. Each paragraph convinces the reader of the answer given in its last sentence. This makes it easy to find the paragraph in which a suspicious conclusion is drawn and to check the logic of that paragraph. The result of each paragraph is a logical statement, and paragraphs farther down in the text rely on the logical conclusions of previous paragraphs, much as theorems are built in mathematical literature.

Rule 8: Discuss how the gap was filled, the limitations of the interpretation, and the relevance to the field

The discussion section explains how the results have filled the gap that was identified in the introduction, provides caveats to the interpretation, and describes how the paper advances the field by providing new opportunities. This is typically done by recapitulating the results, discussing the limitations, and then revealing how the central contribution may catalyze future progress. The first discussion paragraph is special in that it generally summarizes the important findings from the results section. Some readers skip over substantial parts of the results, so this paragraph at least gives them the gist of that section.

Each of the following paragraphs in the discussion section starts by describing an area of weakness or strength of the paper. It then evaluates the strength or weakness by linking it to the relevant literature. Discussion paragraphs often conclude by describing a clever, informal way of perceiving the contribution or by discussing future directions that can extend the contribution.

For example, the first paragraph may summarize the results, focusing on their meaning. The second through fourth paragraphs may deal with potential weaknesses and with how the literature alleviates concerns or how future experiments can deal with these weaknesses. The fifth paragraph may then culminate in a description of how the paper moves the field forward. Step by step, the reader thus learns to put the paper’s conclusions into the right context.

Process (Rules 9 and 10)

To produce a good paper, authors can use helpful processes and habits. Some aspects of a paper affect its impact more than others, which suggests that your investment of time should be weighted towards the issues that matter most. Moreover, iteratively using feedback from colleagues allows authors to improve the story at all levels to produce a powerful manuscript. Choosing the right process makes writing papers easier and more effective.

Rule 9: Allocate time where it matters: Title, abstract, figures, and outlining

The central logic that underlies a scientific claim is paramount. It is also the bridge that connects the experimental phase of a research effort with the paper-writing phase. Thus, it is useful to formalize the logic of ongoing experimental efforts (e.g., during lab meetings) into an evolving document of some sort that will ultimately steer the outline of the paper.

You should also allocate your time according to the importance of each section. The title, abstract, and figures are viewed by far more people than the rest of the paper, and the methods section is read least of all. Budget accordingly.

The time that we do spend on each section can be used efficiently by planning text before producing it. Make an outline. We like to write one informal sentence for each planned paragraph. It is often useful to start the process around descriptions of each result—these may become the section headers in the results section. Because the story has an overall arc, each paragraph should have a defined role in advancing this story. This role is best scrutinized at the outline stage in order to reduce wasting time on wordsmithing paragraphs that don’t end up fitting within the overall story.

Rule 10: Get feedback to reduce, reuse, and recycle the story

Writing can be considered an optimization problem in which you simultaneously improve the story, the outline, and all the component sentences. In this context, it is important not to get too attached to one’s writing. In many cases, trashing entire paragraphs and rewriting is a faster way to produce good text than incremental editing.

There are multiple signs that further work is necessary on a manuscript (see Table 1 ). For example, if you, as the writer, cannot describe the entire outline of a paper to a colleague in a few minutes, then clearly a reader will not be able to. You need to further distill your story. Finding such violations of good writing helps to improve the paper at all levels.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005619.t001

Successfully writing a paper typically requires input from multiple people. Test readers are necessary to make sure that the overall story works. They can also give valuable input on where the story appears to move too quickly or too slowly. They can clarify when it is best to go back to the drawing board and retell the entire story. Reviewers are also extremely useful. Non-specific feedback and unenthusiastic reviews often imply that the reviewers did not “get” the big picture story line. Very specific feedback usually points out places where the logic within a paragraph was not sufficient. It is vital to accept this feedback in a positive way. Because input from others is essential, a network of helpful colleagues is fundamental to making a story memorable. To keep this network working, make sure to pay back your colleagues by reading their manuscripts.

This paper focused on the structure, or “anatomy,” of manuscripts. We had to gloss over many finer points of writing, including word choice and grammar, the creative process, and collaboration. A paper about writing can never be complete; as such, there is a large body of literature dealing with issues of scientific writing [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ].

Personal style often leads writers to deviate from a rigid, conserved structure, and it can be a delight to read a paper that creatively bends the rules. However, as with many other things in life, a thorough mastery of the standard rules is necessary to successfully bend them [ 18 ]. In following these guidelines, scientists will be able to address a broad audience, bridge disciplines, and more effectively enable integrative science.

Acknowledgments

We took our own advice and sought feedback from a large number of colleagues throughout the process of preparing this paper. We would like to especially thank the following people who gave particularly detailed and useful feedback:

Sandra Aamodt, Misha Ahrens, Vanessa Bender, Erik Bloss, Davi Bock, Shelly Buffington, Xing Chen, Frances Cho, Gabrielle Edgerton, multiple generations of the COSMO summer school, Jason Perry, Jermyn See, Nelson Spruston, David Stern, Alice Ting, Joshua Vogelstein, Ronald Weber.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 4. Carter M (2012) Designing Science Presentations: A Visual Guide to Figures, Papers, Slides, Posters, and More: Academic Press.

- 6. Schimel J (2012) Writing science: how to write papers that get cited and proposals that get funded. USA: OUP.

- 7. Tufte ER (1990) Envisioning information. Graphics Press.

- 8. Tufte ER The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Graphics Press.

- 9. Lisberger SG (2011) From Science to Citation: How to Publish a Successful Scientific Paper. Stephen Lisberger.

- 10. Simons D (2012) Dan's writing and revising guide. http://www.dansimons.com/resources/Simons_on_writing.pdf [cited 2017 Sep 9].

- 11. Sørensen C (1994) This is Not an Article—Just Some Thoughts on How to Write One. Syöte, Finland: Oulu University, 46–59.

- 12. Day R (1988) How to write and publish a scientific paper. Phoenix: Oryx.

- 13. Lester JD, Lester J (1967) Writing research papers. Scott, Foresman.

- 14. Dumont J-L (2009) Trees, Maps, and Theorems. Principiae. http://www.treesmapsandtheorems.com/ [cited 2017 Sep 9].

- 15. Pinker S (2014) The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century. Viking Adult.

- 18. Strunk W (2007) The elements of style. Penguin.

Biology Research: Getting Started: Writing & Citing

- Grant Proposals

- Research Design/Methods

- Finding Articles

- Writing & Citing

- Research Tips

- Background Information

Writing/Publishing

Links to Writing and Style Guides

- APA Style and Grammar Guidelines This comprehensive site from the American Psychological Association offers advice on topics that include paper formatting, in-text citations, references, and bias-free language.

- Ecological Society of America Style format for the journals Ecology, Ecological Applications, Ecological Monographs

Other Resources

- Conducting and Writing a Literature Review How to find and put together background information on your topic

- Guidelines for Effective Professional and Academic Writing A concise guide from the University of Florida/Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

- How to Write Scientific Reports A comprehensive guide from the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill's Writing Center

- Materials and Methods An example of how to write up what was done and how it was done in your research.

- Poster and Presentation Resources Advice on presenting academic research and an extensive list of poster resources

- Writing in the Disciplines: Biology Examples of citing your sources from the University of Richmond Writing Center, from Bates College Department of Biology.

Selected Literature Review Books

Health and Sciences Librarian

Literature Review Tutorial

- Literature Reviews: An Overview for Graduate Students What is a literature review? What purpose does it serve in research? What should you expect when writing one? This tutorial from North Carolina State University answers these questions.

Creating Your Bibliography

- RefWorks Bibliographic management tools, such as RefWorks, allow you to organize and manage citations for your bibliography, and work with Microsoft Word to allow insertion of citations as you write a paper.

- RefWorks Information See the RefWorks for Biology page for more information.

- << Previous: Finding Articles

- Next: RefWorks >>

- Last Updated: Feb 1, 2024 1:56 PM

- URL: https://libguides.jsu.edu/bioresearch

- CSI Library Home

- CSI Library

- Writing a Research Paper

- Other Books...recent acquisitions new items!

- Live-Streaming Media

- Statistical Resources

- Citation Style Guides

- Detecting Fake News

- What is Plagiarism? Why Cite? What are the consequences?

- Scholarly Communications

- Jobs and Careers new e-titles!

- Evaluate Journals

- RefWorks - Citation Manager

- Off-Campus Access

Tools to Help You Write Your Research Paper

Find Articles

- JSTOR This link opens in a new window Full text access to complete back runs of scholarly journals across the humanities, social sciences, and sciences. Coverage for most journals does not include the last 3-5 years. Users can search across the entire database or limit their search to journals in specific subject disciplines. Click here for a search tutorial . Many scholarly eBooks are also available on the platform. Coverage Dates: 1665 to present

- Nature Publishing Group List of Journals Nature Publishing Group (NPG) is a publisher of high impact scientific and medical information in print and online. NPG publishes journals, online databases, and services across the life, physical, chemical and applied sciences and clinical medicine. CSI subscribes to a selected list of these titles. Please see our Journal Search on the home page to check for any particular title.

- National Science Digital Library This link opens in a new window The NSDL provides access to resources in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education and research. It includes labs, lectures, readings, games, and full course outlines. Most resources in the library adhere to principles of Open Educational Resource (OER) access.

- ScienceDirect This link opens in a new window Abstracts of scholarly literature in science, technology, and medicine with full text available for articles published after 1995. Core subjects include physics, chemistry, engineering, biology, environmental science, health and medicine. Also provides coverage of a number of titles in the social sciences and humanities (particularly management, economics, psychology, and linguistics). Please note that the Library does not subscribe to all journals in ScienceDirect. Subscribed content is marked by a green "full text available" icon.

- Science Magazine This link opens in a new window Weekly peer-reviewed general science journal published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science covering news, research, and commentary in all areas of the sciences. Full text is available for all issues published since 1997. Issues from 1880 to 2002 are available through JSTOR .

- SpringerLink eBooks and Journals This link opens in a new window Over 20,000 full text ebooks and reference works, and 2,500 journals published by Springer. Core focus is science, technology, and medicine but includes some titles in the social sciences and humanities.

- Wiley Online Library This link opens in a new window Multidisciplinary database offering full text access to select scholarly journals in the fields of life, health and physical sciences, social science and the humanities. For TUTORIALS, click here Coverage Dates: 1997 to present

Books about Research Methods

- << Previous: Statistical Resources

- Next: Citation Style Guides >>

Facebook Twitter Instagram

- URL: https://library.csi.cuny.edu/biology

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 12:53 PM

- Where do I find biology resources in the library?

- What if I can't find what I'm looking for?

- How do I know if my source is a "scholarly" source?

- How do I paraphrase something?

Literature Review Basics

- Literature Review Step-by-Step

- Common Questions about Literature Reviews

- How do I craft a basic citation?

- What is citation tracing?

- How do I use Zotero for citation management?

- Who do I contact for help?

This video will provide a short introduction to literature reviews.

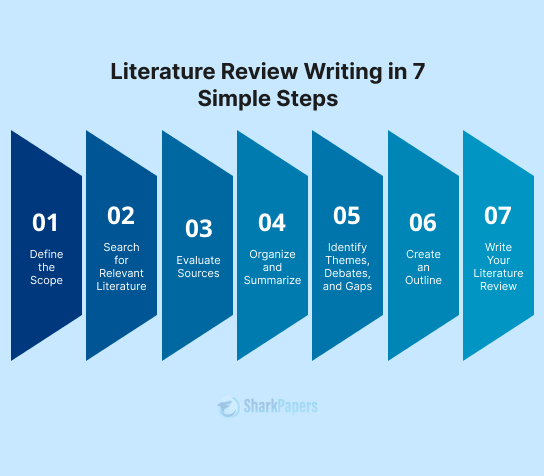

Steps For Writing a Literature Review

Recommended steps for writing a literature review:

- Review what a literature review is, and is not

- Review your assignment and seek clarification from your instructor if needed

- Narrow your topic

- Search and gather literature resources.

- Read and analyze literature resources

- Write the literature review

- Review appropriate Citation and Documentation Style for your assignment and literature review

Common Questions

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a type of scholarly, researched writing that discusses the already published information on a narrow topic .

What is the purpose of a writing literature review?

Writing a literature review improves your personal understanding of a topic, and demonstrates your knowledge and ability to make connections between concepts and ideas. The literature review is a service to your reader, summarizing past ideas about a topic, bringing them up to date on the latest research, and making sure they have all any background information they need to understand the topic.

What is "the literature"?

This already published information- called the literature- can be from primary information sources such as speeches, interviews, and reports, or from secondary information sources such as peer-reviewed journal articles, dissertations, and books. These type of sources are probably familiar to you from previous research projects you’ve done in your classes.

Is a literature review it's own paper?

You can write a literature review as a standalone paper , or as part of a larger research paper . When a standalone paper, the literature review acts as a summary, or snapshot, of what has been said and done about a topic in the field so far. When part of the a larger paper, a literature review still acts as a snapshot, but the prior information it provides can also support the new information, research, or arguments presented later in the paper.

Does a literature review contain an argument?

No, a literature review does NOT present an argument or new information. The literature review is a foundation that summarizes and synthesizes the existing literature in order for you and your readers to understand what has already been said and done about your topic.

- << Previous: How do I paraphrase something?

- Next: How do I craft a basic citation? >>

- Last Updated: Mar 29, 2024 11:34 AM

- URL: https://fhsuguides.fhsu.edu/biology

BIOLOGY JUNCTION

Test And Quizzes for Biology, Pre-AP, Or AP Biology For Teachers And Students

How to Write an Excellent Biology Research Paper

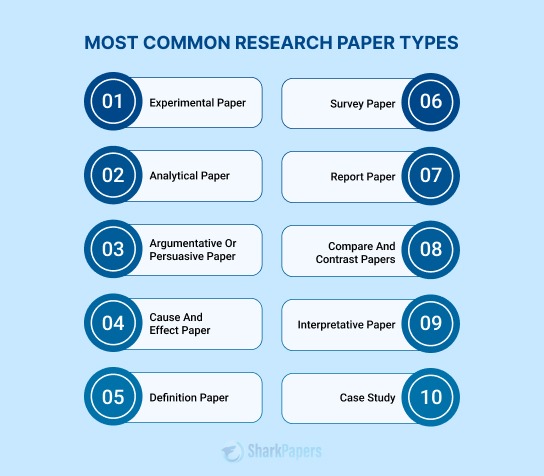

A good example of a biology research paper is not hard to find. The trick, however, is not to find it, but to understand how it was created. Writing such an assignment requires precision, dedication, and an understanding of the rules and expectations of such a paper. And many students are forced to seek biology homework help from various homework help websites like writance.com/pay-for-essay and many others. So, here is a quick guide on how to write a biology research paper. Read, learn, apply, and enjoy the results!

Choose a Topic

Before considering other questions, such as what methods are best to use, asking for paper writing helpfrom an essay helper, or how to format a biology research paper, you need to choose a topic.A title or a thesis statement are not the same as a topic. You choose a general theme for your paper by selecting a topic. It ought to be limited enough to maintain a focused objective. But it shouldn’t be overly constrained. If not, it will be difficult for you to do research and locate the needed sources. Our recommendation applies to selecting a topic for research papers on human resources, technology, or history as well. Pick something you are already familiar with to investigate it more thoroughly.

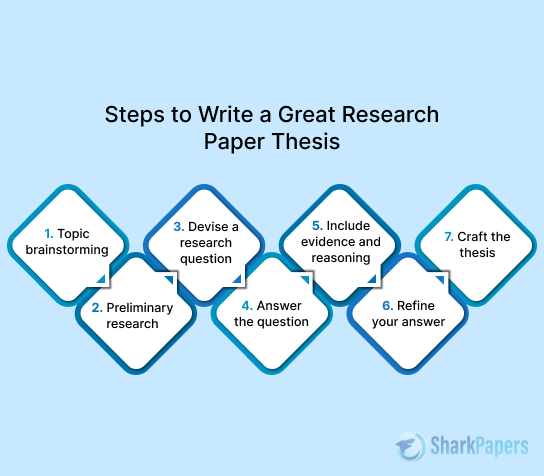

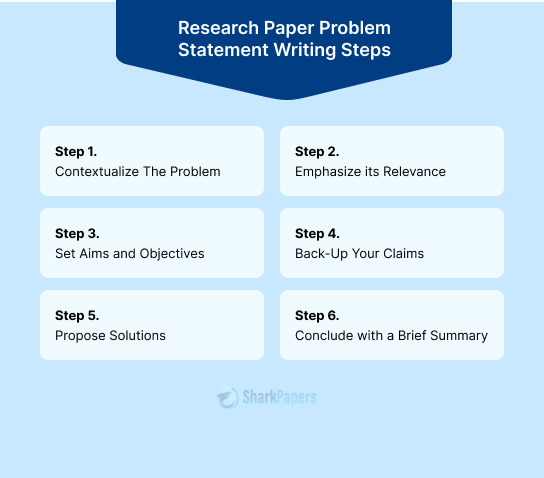

Thesis Statement Definition

The thesis statement is what you can write once you have your topic selected. A thesis statement encapsulates your work’s definition and main goal. Here, you describe the goal of your research—what you hope to learn, demonstrate, or test. You present reasons for why your research is important and what results you want to achieve from the assigned assignment.

You will never find a biology research paper example without a clear thesis statement in the work’s introduction. You must follow these examples and briefly state your work’s goal in the final paragraph of your introduction. The two key components of any introduction are the thesis statement and the overarching theme of your work.

The logical next step for you is to conduct research on your subject. It’s best to finish this step before beginning the outlining process. Make sure your study has application in your field throughout this phase. In other words, you should check to determine if other researchers have conducted similar studies and if you have any original research to offer. If you can’t, you should probably switch topics.