- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Quantitative Research in Communication

- Mike Allen - University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee, USA

- Scott Titsworth - Ohio University, USA

- Stephen K. Hunt - Illinois State University, USA

- Description

Written for communication students, Quantitative Research in Communication provides practical, user-friendly coverage of how to use statistics, how to interpret SPSS printouts, how to write results, and how to assess whether the assumptions of various procedures have been met. Providing a strong conceptual orientation to techniques and procedures that range from the "moderately basic" to "highly advanced," the book provides practical tips and suggestions for quantitative communication scholars of all experience levels. In addition to important foundational information, each chapter that covers a specific statistical procedure includes suggestions for interpreting, explaining, and presenting results; realistic examples of how the procedure can be used to answer substantive questions in communication; sample SPSS printouts; and a detailed summary of a published communication journal article using that procedure.

· Engaged Research application boxes stimulate thought and discussion, illustrating how particular research methods can be used to answer very practical, civic-minded questions.

· Realistic examples at the beginning of each chapter show how the chapter's procedure could be used to answer a substantive research question.

· Examples and application activities geared toward the emerging trend of service learning encourage students to do projects oriented toward their community or campus.

· Summaries of journal articles demonstrate how to write statistical results in APA style and illustrate how real researchers use statistical procedures in a wide variety of contexts, such as tsunami warnings, date requests, and anti-drug public service announcements.

· How to Decipher Figures show students how to "read" the statistical shorthand presented in the quantitative results of an article and also, by implication, show them how to write up results .

Quantitative Research in Communication is ideal for courses in Quantitative Methods in Communication, Statistical Methods in Communication, Advanced Research Methods (undergraduate), and Introduction to Research Methods (Graduate) in departments of communication, educational psychology, psychology, and mass communication.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

This is an excellent book. My students love it.

I particularly like the chapter on meta-analysis as this is one topic that most of the books on survey that I have been using do not discuss.

For instructors

Select a purchasing option, related products.

This title is also available on SAGE Knowledge , the ultimate social sciences online library. If your library doesn’t have access, ask your librarian to start a trial .

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.5: Quantitative Methods

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 184632

- Scott T. Paynton & Laura K. Hahn with Humboldt State University Students

- Humboldt State University

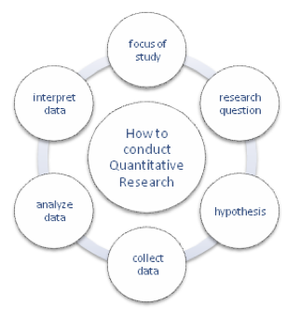

Steps for Doing Quantitative Research

Rhetorical research methods have been being developed since the Classical Period. As the transition was made to seeing communication from a social scientific perspective, scholars began studying communication using the methods established from the physical sciences. Thus, quantitative methods represent the steps of using the Scientific Method of research.

- Decide on a focus of study based primarily on your interests. What do you want to discover or answer?

- Develop a research question(s) to keep your research focused.

- Develop a hypothesis(es). A hypothesis states how a researcher believes the subjects under study will or will not communicate based on certain variables. For example, you may have a research question that asks, “Does the gender of a student impact the number of times a college professor calls on his/her students?” From this, you might form two hypotheses: “Instructors call on female students less often then male students.” and “Instructors call on students of their same sex.”

- Collect data in order to test hypotheses. In our example, you might observe various college classrooms in order to count which students professors call on more frequently.

- Analyze the data by processing the numbers using statistical programs like SPSS that allow quantitative researchers to detect patterns in communication phenomena. Analyzing data in our example would help us determine if there are any significant differences in the ways in which college professors call on various students.

- Interpret the data to determine if patterns are significant enough to make broad claims about how humans communicate? Simply because professors call on certain students a few more times than other students may or may not indicate communicative patterns of significance.

- Share the results with others. Through the sharing of research we continue to learn more about the patterns and rules that guide the ways we communicate.

The term quantitative refers to research in which we can quantify, or count, communication phenomena . Quantitative methodologies draw heavily from research methods in the physical sciences explore human communication phenomena through the collection and analysis of numerical data. Let’s look at a simple example. What if we wanted to see how public speaking textbooks represent diversity in their photographs and examples. One thing we could do is quantify these to come to conclusions about these representations. For quantitative research, we must determine which communicative acts to count? How do we go about counting them? Is there any human communicative behavior that would return a 100% response rate like the effects of gravity in the physical sciences? What can we learn by counting acts of human communication?

Suppose you want to determine what communicative actions illicit negative responses from your professors. How would you go about researching this? What data would you count? In what ways would you count them? Who would you study? How would you know if you discovered anything of significance that would tell us something important about this? These are tough questions for researchers to answer, particularly in light of the fact that, unlike laws in the physical sciences, human communication is varied and unpredictable.

Nevertheless, there are several quantitative methods researchers use to study communication in order to reveal patterns that help us predict and control our communication. Think about polls that provide feedback for politicians. While people do not all think the same, this type of research provides patterns of thought to politicians who can use this information to make policy decisions that impact our lives. Let’s look at a few of the more frequent quantitative methods of communication research.

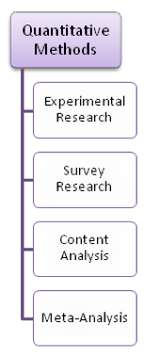

Types of Quantitative Methods

There are many ways researchers can quantify human communication. Not all communication is easily quantified, but much of what we know about human communication comes from quantitative research.

- Experimental Research is the most well-established quantitative methodology in both the physical and social sciences. This approach uses the principles of research in the physical sciences to conduct experiments that explore human behavior. Researchers choose whether they will conduct their experiments in lab settings or real-world settings. Experimental research generally includes a control group (the group where variables are not altered) and the experimental group(s) (the group in which variables are altered). The groups are then carefully monitored to see if they enact different reactions to different variables.

To determine if students were more motivated to learn by participating in a classroom game versus attending a classroom lecture, the researchers designed an experiment. They wanted to test the hypothesis that students would actually be more motivated to learn from the game. Their next question was, “do students actually learn more by participating in games?” In order to find out the answers to these questions they conducted the following experiment. In a number of classes instructors were asked to proceed with their normal lecture over certain content (control group), and in a number of other classes, instructors used a game that was developed to teach the same content (experimental group). The students were issued a test at the end of the semester to see which group did better in retaining information, and to find out which method most motivated students to want to learn the material. It was determined that students were more motivated to learn by participating in the game, which proved the hypothesis. The other thing that stood out was that students who participated in the game actually remembered more of the content at the end of the semester than those who listened to a lecture. You might have hypothesized these conclusions yourself, but until research is done, our assumptions are just that (Hunt, Lippert & Paynton).

Case In Point

Quantitative methods in action.

Wendy S. Zabada-Ford (2003) conducted survey research of 253 customers to determine their expectations and experiences with physicians, dentists, mechanics, and hairstylists. Her article, “Research Communication Practices of Professional Service Providers: Predicting Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty” researched the perceptions of customers’ personalized service as related to their expectations in order to predict their satisfaction with the actual service they received. In this study, the goal was to be able to predict the behavior of customers based on their expectations before entering a service-provider context.

Michael T. Stephenson’s (2003) article, “Examining Adolescents’ Responses to Anti-marijuana PSAs” examined how adolescents respond to anti-marijuana public service announcements in the U.S. On the surface, this study may fit into the “understanding” part of the continuum of intended outcomes. However, this research can be used to alter and change messages, such as PSAs, to produce behavioral change in the culture. In this case, the change would be to either keep adolescents from smoking marijuana, or to get them to stop this behavior if they are currently engaged in it.

- Survey Research is used to ask people a number of questions about particular topics. Surveys can be online, mailed, handed out, or conducted in interview format. After researchers have collected survey data, they represent participants’ responses in numerical form using tables, graphs, charts, and/or percentages. On our campus, anonymous survey research was done to determine the drinking and drug habits of our students. This research demonstrated that the percentage of students who frequently use alcohol or drugs is actually much lower than what most students think. The results of this research are now used to educate students that not everyone engages in heavy drinking or drug use, and to encourage students to more closely align their behaviors with what actually occurs on campus, not with what students perceive happens on campus. It is important to remember that there is a possibility that people do not always tell the truth when they answer survey questions. We won’t go into great detail here due to time, but there are sophisticated statistical analyses that can account for this to develop an accurate representation of survey responses.

- Content Analysis . Researchers use content analysis to count the number of occurrences of their particular focus of inquiry. Communication researchers often conduct content analyses of movies, commercials, television shows, magazines, etc., to count the number of occurrences of particular phenomena in these contexts to explore potential effects. Harmon, for example, used content analysis in order to demonstrate how the portrayal of blackness had changed within Black Entertainment Television (BET). She did this by observing the five most frequently played films from the time the cable network was being run by a black owner, to the five most frequently played films after being sold to white-owned Viacom, Inc. She found that the portrayal, context and power of the black man changes when a white man versus a black man is defining it. Content analysis is extremely effective for demonstrating patterns and trends in various communication contexts. If you would like to do a simple content analysis, count the number of times different people are represented in photos in your textbooks. Are there more men than women? Are there more caucasians represented than other groups? What do the numbers tell you about how we represent different people?

- Meta-Analysis . Do you ever get frustrated when you hear about one research project that says a particular food is good for your health, and then some time later, you hear about another research project that says the opposite? Meta-analysis analyzes existing statistics found in a collection of quantitative research to demonstrate patterns in a particular line of research over time. Meta-analysis is research that seeks to combine the results of a series of past studies to see if their results are similar, or to determine if they show us any new information when they are looked at in totality. The article, Impact of Narratives on Persuasion in Health Communication: A Meta-Analysis examined past research regarding narratives and their persuasiveness in health care settings. The meta-analysis revealed that in-person and video narratives had the most persuasive impacts while written narratives had the least (Shen, Sheer, Li).

Outcomes of Quantitative Methodologies

Because it is unlikely that Communication research will yield 100% certainty regarding communicative behavior, why do Communication researchers use quantitative approaches? First, the broader U.S. culture values the ideals of quantitative science as a means of learning about and representing our world. To this end, many Communication researchers emulate research methodologies of the physical sciences to study human communication phenomena. Second, you’ll recall that researchers have certain theoretical and methodological preferences that motivate their research choices. Those who understand the world from an Empirical Laws and/or Human Rules Paradigm tend to favor research methods that test communicative laws and rules in quantitative ways.

Even though Communication research cannot produce results with 100% accuracy, quantitative research demonstrates patterns of human communication. In fact, many of your own interactions are based on a loose system of quantifying behavior. Think about how you and your classmates sit in your classrooms. Most students sit in the same seats every class meeting, even if there is not assigned seating. In this context, it would be easy for you to count how many students sit in the same seat, and what percentage of the time they do this. You probably already recognize this pattern without having to do a formal study. However, if you wanted to truly demonstrate that students communicatively manifest territoriality to their peers, it would be relatively simple to conduct a quantitative study of this phenomenon. After completing your research, you could report that X% of students sat in particular seats X% of times. This research would not only provide us with an understanding of a particular communicative pattern of students, it would also give us the ability to predict, to a certain degree, their future behaviors surrounding space issues in the classroom.

Quantitative research is also valuable for helping us determine similarities and/or differences among groups of people or communicative events. Representative examples of research in the areas of gender and communication (Berger; Slater), culture and communication (McCann, Ota, Giles, & Caraker; Hylmo & Buzzanell), as well as ethnicity and communication (Jiang Bresnahan, Ohashi, Nebashi, Wen Ying, Shearman; Murray-Johnson) use quantitative methodologies to determine trends and patterns of communicative behavior for various groups. While these trends and patterns cannot be applied to all people, in all contexts, at all times, they help us understand what variables play a role in influencing the ways we communicate.

While quantitative methods can show us numerical patterns, what about our personal lived experiences? How do we go about researching them, and what can they tell us about the ways we communicate? Qualitative methods have been established to get at the “essence” of our lived experiences, as we subjectively understand them.

Contributions and Affiliations

- Survey of Communication Study. Authored by : Scott T Paynton and Linda K Hahn. Provided by : Humboldt State University. Located at : en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Survey_of_Communication_Study/Preface. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Guide to Communication Research Methodologies: Quantitative, Qualitative and Rhetorical Research

Overview of Communication

Communication research methods, quantitative research, qualitative research, rhetorical research, mixed methodology.

Students interested in earning a graduate degree in communication should have at least some interest in understanding communication theories and/or conducting communication research. As students advance from undergraduate to graduate programs, an interesting change takes place — the student is no longer just a repository for knowledge. Rather, the student is expected to learn while also creating knowledge. This new knowledge is largely generated through the development and completion of research in communication studies. Before exploring the different methodologies used to conduct communication research, it is important to have a foundational understanding of the field of communication.

Defining communication is much harder than it sounds. Indeed, scholars have argued about the topic for years, typically differing on the following topics:

- Breadth : How many behaviors and actions should or should not be considered communication.

- Intentionality : Whether the definition includes an intention to communicate.

- Success : Whether someone was able to effectively communicate a message, or merely attempted to without it being received or understood.

However, most definitions discuss five main components, which include: sender, receiver, context/environment, medium, and message. Broadly speaking, communication research examines these components, asking questions about each of them and seeking to answer those questions.

As students seek to answer their own questions, they follow an approach similar to most other researchers. This approach proceeds in five steps: conceptualize, plan and design, implement a methodology, analyze and interpret, reconceptualize.

- Conceptualize : In the conceptualization process, students develop their area of interest and determine if their specific questions and hypotheses are worth investigating. If the research has already been completed, or there is no practical reason to research the topic, students may need to find a different research topic.

- Plan and Design : During planning and design students will select their methods of evaluation and decide how they plan to define their variables in a measurable way.

- Implement a Methodology : When implementing a methodology, students collect the data and information they require. They may, for example, have decided to conduct a survey study. This is the step when they would use their survey to collect data. If students chose to conduct a rhetorical criticism, this is when they would analyze their text.

- Analyze and Interpret : As students analyze and interpret their data or evidence, they transform the raw findings into meaningful insights. If they chose to conduct interviews, this would be the point in the process where they would evaluate the results of the interviews to find meaning as it relates to the communication phenomena of interest.

- Reconceptualize : During reconceptualization, students ask how their findings speak to a larger body of research — studies related to theirs that have already been completed and research they should execute in the future to continue answering new questions.

This final step is crucial, and speaks to an important tenet of communication research: All research contributes to a better overall understanding of communication and moves the field forward by enabling the development of new theories.

In the field of communication, there are three main research methodologies: quantitative, qualitative, and rhetorical. As communication students progress in their careers, they will likely find themselves using one of these far more often than the others.

Quantitative research seeks to establish knowledge through the use of numbers and measurement. Within the overarching area of quantitative research, there are a variety of different methodologies. The most commonly used methodologies are experiments, surveys, content analysis, and meta-analysis. To better understand these research methods, you can explore the following examples:

Experiments : Experiments are an empirical form of research that enable the researcher to study communication in a controlled environment. For example, a researcher might know that there are typical responses people use when they are interrupted during a conversation. However, it might be unknown as to how frequency of interruption provokes those different responses (e.g., do communicators use different responses when interrupted once every 10 minutes versus once per minute?). An experiment would allow a researcher to create these two environments to test a hypothesis or answer a specific research question. As you can imagine, it would be very time consuming — and probably impossible — to view this and measure it in the real world. For that reason, an experiment would be perfect for this research inquiry.

Surveys : Surveys are often used to collect information from large groups of people using scales that have been tested for validity and reliability. A researcher might be curious about how a supervisor sharing personal information with his or her subordinate affects way the subordinate perceives his or her supervisor. The researcher could create a survey where respondents answer questions about a) the information their supervisors self-disclose and b) their perceptions of their supervisors. The data collected about these two variables could offer interesting insights about this communication. As you would guess, an experiment would not work in this case because the researcher needs to assess a real relationship and they need insight into the mind of the respondent.

Content Analysis : Content analysis is used to count the number of occurrences of a phenomenon within a source of media (e.g., books, magazines, commercials, movies, etc.). For example, a researcher might be interested in finding out if people of certain races are underrepresented on television. They might explore this area of research by counting the number of times people of different races appear in prime time television and comparing that to the actual proportions in society.

Meta-Analysis : In this technique, a researcher takes a collection of quantitative studies and analyzes the data as a whole to get a better understanding of a communication phenomenon. For example, a researcher might be curious about how video games affect aggression. This researcher might find that many studies have been done on the topic, sometimes with conflicting results. In their meta-analysis, they could analyze the existing statistics as a whole to get a better understanding of the relationship between the two variables.

Qualitative research is interested in exploring subjects’ perceptions and understandings as they relate to communication. Imagine two researchers who want to understand student perceptions of the basic communication course at a university. The first researcher, a quantitative researcher, might measure absences to understand student perception. The second researcher, a qualitative researcher, might interview students to find out what they like and dislike about a course. The former is based on hard numbers, while the latter is based on human experience and perception.

Qualitative researchers employ a variety of different methodologies. Some of the most popular are interviews, focus groups, and participant observation. To better understand these research methods, you can explore the following examples:

Interviews : This typically consists of a researcher having a discussion with a participant based on questions developed by the researcher. For example, a researcher might be interested in how parents exert power over the lives of their children while the children are away at college. The researcher could spend time having conversations with college students about this topic, transcribe the conversations and then seek to find themes across the different discussions.

Focus Groups : A researcher using this method gathers a group of people with intimate knowledge of a communication phenomenon. For example, if a researcher wanted to understand the experience of couples who are childless by choice, he or she might choose to run a series of focus groups. This format is helpful because it allows participants to build on one another’s experiences, remembering information they may otherwise have forgotten. Focus groups also tend to produce useful information at a higher rate than interviews. That said, some issues are too sensitive for focus groups and lend themselves better to interviews.

Participant Observation : As the name indicates, this method involves the researcher watching participants in their natural environment. In some cases, the participants may not know they are being studied, as the researcher fully immerses his or herself as a member of the environment. To illustrate participant observation, imagine a researcher curious about how humor is used in healthcare. This researcher might immerse his or herself in a long-term care facility to observe how humor is used by healthcare workers interacting with patients.

Rhetorical research (or rhetorical criticism) is a form of textual analysis wherein the researcher systematically analyzes, interprets, and critiques the persuasive power of messages within a text. This takes on many forms, but all of them involve similar steps: selecting a text, choosing a rhetorical method, analyzing the text, and writing the criticism.

To illustrate, a researcher could be interested in how mass media portrays “good degrees” to prospective college students. To understand this communication, a rhetorical researcher could take 30 articles on the topic from the last year and write a rhetorical essay about the criteria used and the core message argued by the media.

Likewise, a researcher could be interested in how women in management roles are portrayed in television. They could select a group of popular shows and analyze that as the text. This might result in a rhetorical essay about the behaviors displayed by these women and what the text says about women in management roles.

As a final example, one might be interested in how persuasion is used by the president during the White House Correspondent’s Dinner. A researcher could select several recent presidents and write a rhetorical essay about their speeches and how they employed persuasion during their delivery.

Taking a mixed methods approach results in a research study that uses two or more techniques discussed above. Often, researchers will pair two methods together in the same study examining the same phenomenon. Other times, researchers will use qualitative methods to develop quantitative research, such as a researcher who uses a focus group to discuss the validity of a survey before it is finalized.

The benefit of mixed methods is that it offers a richer picture of a communication phenomenon by gathering data and information in multiple ways. If we explore some of the earlier examples, we can see how mixed methods might result in a better understanding of the communication being studied.

Example 1 : In surveys, we discussed a researcher interested in understanding how a supervisor sharing personal information with his or her subordinate affects the way the subordinate perceives his or her supervisor. While a survey could give us some insight into this communication, we could also add interviews with subordinates. Exploring their experiences intimately could give us a better understanding of how they navigate self-disclosure in a relationship based on power differences.

Example 2 : In content analysis, we discussed measuring representation of different races during prime time television. While we can count the appearances of members of different races and compare that to the composition of the general population, that doesn’t tell us anything about their portrayal. Adding rhetorical criticism, we could talk about how underrepresented groups are portrayed in either a positive or negative light, supporting or defying commonly held stereotypes.

Example 3 : In interviews, we saw a researcher who explored how power could be exerted by parents over their college-age children who are away at school. After determining the tactics used by parents, this interview study could have a phase two. In this phase, the researcher could develop scales to measure each tactic and then use those scales to understand how the tactics affect other communication constructs. One could argue, for example, that student anxiety would increase as a parent exerts greater power over that student. A researcher could conduct a hierarchical regression to see how each power tactic effects the levels of stress experienced by a student.

As you can see, each methodology has its own merits, and they often work well together. As students advance in their study of communication, it is worthwhile to learn various research methods. This allows them to study their interests in greater depth and breadth. Ultimately, they will be able to assemble stronger research studies and answer their questions about communication more effectively.

Note : For more information about research in the field of communication, check out our Guide to Communication Research and Scholarship .

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Why Submit?

- About Human Communication Research

- About International Communication Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Final thoughts, acknowledgments.

- < Previous

Quantitative criticalism for social justice and equity-oriented communication research

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Youllee Kim, Quantitative criticalism for social justice and equity-oriented communication research, Human Communication Research , Volume 50, Issue 2, April 2024, Pages 162–172, https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqad048

- Permissions Icon Permissions

An increasing number of communication researchers have noted the potential of quantitative criticalism (QuantCrit) or the use of quantitative approaches to pursue social justice and equity agenda. Nonetheless, how to achieve the goals and ideals of QuantCrit in communication studies still largely remains uncharted terrain. This article offers five concrete suggestions for how researchers can bring critical consciousness to quantitative communication research: (a) broadening and diversifying the scope of communication research, (b) (re)framing research questions with a social justice orientation, (c) critiquing dominant narratives and centering the counternarratives, (d) incorporating intersectionality to address marginalization, and (e) employing statistical methods that illuminate interdependence, systems, and power dynamics. This article seeks to enrich the discussion on ways to embrace QuantCrit in communication research to revitalize perspectives and means for identifying and addressing inequalities, and eventually to advance transformative scholarship.

A scholar’s research paradigm, or the lens through which researchers view the world, has implications for the research questions they propose, their ways of knowing, and the methodological choices they make ( Kuhn, 1962 ). Traditionally, the predominant research paradigms, such as postpositivist and critical paradigms, tended to claim their own ways of conducting research based on distinctive research goals and questions. However, the paradigmatic boundary has started to be challenged by scholars who seek greater possibilities of what their overlap can explore, explain, and achieve ( Curtis et al., 2022 ; Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016a ; Suter, 2018 ). The term quantitative criticalism (QuantCrit) describes research efforts that use quantitative approaches, which have generally been grounded in a postpositivist paradigm, to identify and challenge socially perpetuated injustices and inequalities ( Stage & Wells, 2014a ). Allowing researchers to reimagine the possibilities of quantitative approaches, QuantCrit has implications for social justice and equity research, which has been thought of as located within the critical paradigm ( Stage, 2007 ).

When properly employed, QuantCrit approaches provide communication researchers with the capacity to use scientific practices to investigate and challenge dominant ideologies, power dynamics, and systemic oppression that are at play in different levels (e.g., intrapersonal, interpersonal, societal, etc.) and contexts (e.g., family, health, political, etc.) of communication. Within the last few decades, communication scholars have shown a growing interest in employing quantitative methods to pursue social justice and equity agenda ( Scharrer & Ramasubramanian, 2021 ). Both across different disciplines and within the field of communication, there is a general consensus on what QuantCrit should strive for. Nevertheless, the question of how we should achieve the ideals and aims of QuantCrit still largely remains unanswered, leaving quantitative researchers with inadequate guidelines for critical reflection. In this article, I aim to elaborate on how communication researchers can employ quantitative methods to conduct critical research. This article contributes to theory development and the expansion of communication research by proposing QuantCrit as a way of inquiry through which communication scholars can reflect on the types of questions they ask, interrogate their decisions during the research process, and seek to transform our world.

To this end, I begin this article with an overview of different paradigms and an introduction to QuantCrit. I then make five suggestions on how communication researchers can bring critical consciousness to quantitative research: (a) broaden and diversify the scope of communication research, (b) (re)frame research questions with a social justice orientation, (c) critique the dominant narratives and center the counternarratives, (d) incorporate intersectionality to address marginalization, and (e) employ statistical methods that illuminate interdependence, systems, and power dynamics. For each suggestion, I critically review exemplary studies and/or tweak existing studies with a critical lens.

Research paradigms and quantitative criticalism (QuantCrit)

Multiple research paradigms exist, each of which involves four, interrelated philosophical components: ontology, epistemology, axiology, and methodology ( Crotty, 2003 ). At the highest level, ontological assumptions about the nature of reality lead to an epistemological stance or a way of knowing. Axiology refers to the assumptions regarding ethics and value systems, which shape the aim and process of research. Ontological, epistemological, and axiological choices and assumptions have tended to guide methodology or the way in which researchers collect and evaluate evidence ( Guba, 1990 ). Building on different philosophical components, research paradigms have traditionally claimed distinctive boundaries from one another.

To provide bases for QuantCrit, I first review aspects of postpositivist and critical paradigms as they have developed in communication studies. The philosophical root of postpositivism is positivism, which is grounded in the assumption that a single, objective reality exists. From positivists’ point of view, all scientific inquiries should be value-free to discover the Truth that is unbiased ( Crotty, 2003 ). More prevalent in communication studies are postpositivist views, which dismiss the notion of a single reality (one Truth), but maintain that truths about the world can be revealed through research ( Corman, 2005 ). Though acknowledging that researchers’ value systems might influence the questions they ask, postpositivists still try to reduce the subjectivity in data collection and analysis processes as much as possible. With the aim of explaining, predicting, and controlling the phenomena of interest, communication research that is situated within the postpositivist paradigm has conventionally employed quantitative approaches in which researchers test hypotheses with numerical data ( Miller, 2005 ).

Evolved from the German Frankfurt School, the critical paradigm has grown to embrace different perspectives under the critical canon such as race, feminist, queer, disability, and decolonial theories (e.g., Crenshaw, 1991 ; Goodley, 2013 ; Watson, 2005 ). Philosophical assumptions underlying the critical paradigm are not always unitary, but there are commonalities among the variants of critical theory. While some critical scholars favor more objective views of reality and see the social structures as relatively fixed, most critical scholars today hold an assumption that what can be known about the world is socially constructed (see Miller [2005] for further discussion of different positions held by critical theorists). The belief that we cannot separate ourselves from our knowledge inevitably influences critical scholar’s inquiry. Understanding reality within power relations, critical scholars are committed to using their work as a form of criticism that identifies, evaluates, and challenges systems of power, thereby stimulating social change and transformation ( Morrow & Brown, 1994 ). For critical scholars, research is a value-laden activity that should advocate for the oppressed and disadvantaged. Although critical research in many disciplines including communication has often been conducted with data that are qualitative and in-depth in nature, there is nothing about critical inquiry itself that is inherently opposed to quantitative approaches to research, which presents an opportunity for QuantCrit scholarship ( Stage & Wells, 2014a ).

In advocating for QuantCrit, I note Deetz’s (2001) perspective that emphasizes the fluid and integrative nature of knowledge production. Ontological, epistemological, and axiological assumptions of different paradigms provide meaningful distinctions that help us understand how and why research is conducted and interpreted. Yet, these higher-order philosophical assumptions should not impose limits on methodological assumptions about generating knowledge ( Morgan, 2007 ). Isolating knowledge production within a certain paradigm results in polarizing different types of knowledge and disconnecting our understanding of the phenomenon under study, rather than meaningfully advancing scholarship ( Droser, 2017 ). QuantCrit deconstructs assumptions that certain types of research inquiry are tied to particular methodologies and subsequent practical procedures at the level of data collection and analysis. I suggest that the value of identifying and addressing injustices and inequalities can be a place of common ground where researchers with different methodological approaches build a more inclusive and comprehensive base of knowledge for socially just purposes. Any research method can be used for socially just purposes, and QuantCrit maximizes the potential of quantitative research or the ‘power of numbers’ ( Scharrer & Ramasubramanian, 2021 , p. 2) to identify inequalities and raise awareness, to propose and test solutions, or to otherwise pursue social justice and equity agenda.

Along with increasing scholarly attention, QuantCrit scholarship has faced critiques and challenges. One critique is relevant to the history of ethical violations and perpetuation of existing prejudices by scientific research (see Cokley & Awad [2013] and Scharrer & Ramasubramanian [2021] for the discussion of specific examples). In a sense, QuantCrit is a call to prove the value of quantitative research in promoting social justice and equity notwithstanding the historical scientific misconduct. In addition to minimizing the potential risks of harm associated with research, QuantCrit researchers should foreground ethical considerations to ensure that the processes as well as products of research reduce social inequalities and improve the social contexts in which their research is grounded.

Another critique relates to epistemological tensions between the paradigms, such that certain elements of quantitative methodologies, including researcher objectivity and emphasis on generalizability, seem at odds with a critical paradigm ( McLaren, 2017 ). QuantCrit researchers have addressed these tensions by pointing out that quantitative approaches that claim to be objective are in fact value-laden and not free from researchers’ potential bias ( Stage, 2007 ). QuantCrit researchers are encouraged to reflect on their own positionality as researchers and the values they hold, which help them understand the power afforded and constrained in the assumptions and choices they make in research. Importantly, QuantCrit researchers should maintain methodological rigor and high levels of statistical expertise while maintaining a critical stance ( Stage & Wells, 2014b ). Researchers inexperienced with a critical scholarship may fail to appreciate the potential of research in transforming the current status quo, while researchers without a high level of statistical expertise may not know how to accurately analyze quantitative data to their fullest potential ( Curtis et al., 2022 ).

Concerns have also arisen regarding the meaning of critical inquiry ( Stage & Wells, 2014a ). Some critical scholars have argued that to be critical, the methods must be directly transformative or at least engage with the community of interest. Although there is value in action-oriented critical research, QuantCrit embraces a broader conceptualization of critical inquiry, one that, regardless of the method, reveals inequality and attends to the experiences of marginalized individuals ( Stage & Wells, 2014b ). By adopting this broader understanding of critical inquiry, QuantCrit allows for many different ways to utilize quantitative approaches for social change and transformation, ranging from raising awareness and offering critique based on quantitative evidence to examining the causal logic of interventions and assessing unintentional consequences of interventions for social justice.

With an aim of offering concrete guidelines for the integration of QuantCrit in communication studies, I next turn to articulate five suggestions for how researchers can infuse critical consciousness into quantitative communication research. Before proceeding further, I note two important points. First, for each suggestion, I introduce example studies that illustrate the main point of the suggestion while acknowledging that the discussed studies often entail features that may also relate to other suggestions. Second, a single QuantCrit study may not always incorporate all five suggestions. Instead, I ask QuantCrit researchers to strive for building a program of research involving multiple studies that incorporate different sets of suggestions that, together, support social justice and equity goals.

Broadening and diversifying the scope of communication research

One way to promote critical consciousness in quantitative research is to broaden and diversify the scope of research to be more inclusive of often marginalized populations and their communication practices. Although being inclusive of members from diverse backgrounds does not always guarantee social justice, diversity and inclusion are critical components of social justice ( Cokley & Awad, 2013 ). Putting conscious efforts in research toward examining diverse population groups and cultural contexts not only broadens our understanding of human communication but also helps avoid generalizing the findings from one group (e.g., WEIRD samples; “people from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic societies.” Henrich et al., 2010 , p. 61) to other humans with different lived experiences.

In broadening the scope of communication research, QuantCrit researchers should examine neglected communication phenomena in relation to systems of power and oppression. For instance, interpersonal communication research has mostly been conducted with WEIRD samples, which resulted in not only silencing discussions of race and power but also limiting our capability to draw transferable insights regarding people and topics that have been traditionally marginalized ( Afifi & Cornejo, 2020 ). In addition, research examining interpersonal communication of non-WEIRD populations has tended to locate them in relation to the WEIRD population by highlighting the differences in interracial communication encounters, and thus largely ignoring intracultural stories or interpersonal communication among romantic partners, families, and friends within the non-WEIRD population groups ( Houston, 2002 ).

Kam et al. (2017) is noteworthy in that researchers examined interpersonal communication among a marginalized population, but it also showcases why studying a marginalized population is not sufficient to make the research critical. One example of an understudied group in communication is Spanish-speaking families and especially child language brokers in these families who translate the English language and interpret cultural practices for their English-limited parents ( Kam et al., 2017 ). Based on the data from low-income, Spanish-speaking mother–child dyads, Kam et al. (2017) found that child language brokers in families in which mothers and children share communal coping views were less likely to experience depressive symptoms than in families where mothers deny the responsibility of stress ownership and coping behaviors. Furthermore, Kam et al. (2017) tested empirical constructs, such as close ties to family (i.e., familismo ) and respect for family (i.e., respeto ) rooted in the values and realities of Latino/a families, as predictors of different coping styles.

Despite the study’s many insights, the nature of Kam et al. (2017) is descriptive and predictive, and not critical. Critical research should attend to issues of power and critique the status quo to pursue social justice ( Suter, 2016 ). To propose and answer questions from a critical stance, future studies may examine how the unequal power dynamics and the systems of oppression faced by immigrants, such as exclusionary immigration policies, economic hardships, and racial discrimination, shape the experience of language brokering in immigrant families. In doing so, quantitative approaches can enable researchers to examine and compare multiple structural factors that contribute to negative (or positive) consequences of language brokering.

In media effects studies, for a different example, prior research on the impact of media representations of minorities mostly focused on the majority members while only a few studies examined the effects of exposure to stereotypical media content on minorities themselves ( Mastro, 2009 ; Riles et al., 2022 ). In Saleem et al. (2019) , for a notable exception, exposure to negative news coverage of Muslims decreased Muslim Americans’ strength of identification as Americans, but not as Muslims, which in turn, reduced their trust in the U.S. government. Similarly, Saleem and Ramasubramanian (2019) demonstrated that Muslim Americans who viewed negative media representations of Muslims, compared to a control video, were less likely to desire acceptance by other Americans and more likely to avoid interactions with non-Muslim Americans.

Although the above-mentioned studies did not explicitly adopt the critical lens to research, Saleem et al. (2019) interpreted their findings with a critical consciousness, highlighting that a broader social context like the hegemonic power of mainstream media that transcends individual, personal experiences (e.g., everyday experience of discrimination) should be accounted for in research on stigmatized minorities. In addition to calling for more balanced representations of minority groups in mainstream media, Saleem and Ramasubramanian (2019) emphasized that their findings can serve as a basis to develop minority group members’ critical media literacy skills that help challenge negative media images. As evidenced in these examples, the integration of QuantCrit approaches can begin as early as when choosing the communication phenomenon of interest and continue throughout the research process to expose and challenge inequity when interpreting the study findings.

(Re)framing research questions with a social justice and equity orientation

The second suggestion for communication researchers seeking to embrace QuantCrit in their work is to consider (re)framing research questions with more explicit intentionality toward social justice and equity. In rejecting the notion that quantitative research is value-free and politically neutral, QuantCrit researchers can take an ethical position and propose research questions with social justice goals. Without establishing social justice orientations in research questions, quantitative research that examines marginalized populations may as well perpetuate existing power dynamics by making individuals accountable for the inequalities.

To discuss examples of quantitative communication studies that adopt research questions with a social justice orientation, I first turn to the field of health communication. Many health interventions take the form of persuasive communication that targets individuals’ psychological processes to change personal health behaviors (e.g., Fishbein & Cappella, 2006 ). The success of health communication campaigns has thus generally been evaluated based on the extent to which interventions influence individuals’ cognitions, emotions, and engagement with the recommended behavior ( Dutta-Bergman, 2005 ). With critical inquiry, quantitative researchers can go beyond examining interventions’ effects on individual-level changes and explore interventions’ effects on reducing health disparities at a societal level.

Launched by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2011, the Testing Makes Us Stronger (TMUS) campaign serves as a good example. To address disproportionate rates of HIV transmission in the Black/African American population in the United States, the TMUS campaign aimed to increase HIV testing among Black or African American men who have sex with men (BMSM). Prior studies that evaluated the campaign effectiveness mostly focused on the campaign’s influence on individual-level attitude and behavior change (e.g., Badal et al., 2019 ). When the research question centers on understanding individual-level outcomes, such findings can be the basis to document the success of the TMUS campaign.

Nevertheless, a question with a social justice orientation may illuminate a different side of the story. A QuantCrit researcher may ask, “Will the campaign aiming to increase HIV testing among BMSM reduce disproportionate rates of HIV transmission in the Black or African American population?” Even though the campaign increased BMSM’s HIV testing rates, there existed a continuous rise of HIV transmissions within the BMSM community, thus bringing into question the success of the TMUS campaign ( Hawkins, 2020 ). Importantly, socioeconomic issues associated with poverty including homelessness, lack of access to health care, and food insecurity, directly and indirectly, increase the risk of contracting HIV among BMSM ( Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2019 ). Additionally, culturally constructed barriers, such as homophobia and HIV-related stigma, may affect other stages of the HIV care continuum, challenging individuals to seek appropriate care after being tested positive for HIV ( Arnold et al., 2014 ). Critical inquiry can guide researchers to be more attentive to systemic inequities and cultural influences in which health problems are embedded. With the capability to examine macrolevel, large-scale patterns with numerical data, quantitative approaches are well-positioned to provide clear and convincing answers to critical questions asked at the societal level.

While the above example centers on health communication, QuantCrit researchers can ask questions that advocate for social transformation across any subdiscipline of communication. For instance, from Asch’s (1955) research on group conformity to Noelle-Neumann’s (1991) spiral of silence theory, robust literature indicates that people tend to remain silent when their opinions do not seem to match with that of the majority. Of course, this is not always true. Although fewer in number, some researchers have investigated why certain minorities still express their opinions in such contexts ( Morrison & Miller, 2008 ). Exploring the possibility that minorities can challenge the existing social norms entails reframing research questions, which can be an initial step toward social justice-oriented research.

By reframing research questions to examine the phenomenon of minority opinion expression, most (non-QuantCrit) prior research has examined self- (e.g., need for uniqueness; Blanton & Christie, 2003 ) and group- (e.g., motivation to improve the group with which they identify; Rios, 2012 ) oriented motivation, as well as personality traits (e.g., low trait communication apprehension; Neuwirth et al., 2007 ), as contributors for minority opinion expression. In these works, the term minority is usually defined as a vocal minority whose attitudes differ from those of most other group members. In comparison, a QuantCrit researcher may be more interested in individuals from historically marginalized groups who might or might not be vocal minorities in a given context. Research questions can then be framed to examine how and why marginalized individuals challenge systemic inequality factors to have their voices heard. Instead of examining individuals’ motivations or personality traits, a QuantCrit researcher can investigate how social exclusion measured at the group level (e.g., Chakravarty & D’Ambrosio, 2006 ) or network level (e.g., Parks, 1977 ) interfere with marginalized individuals’ willingness to express their opinion. A QuantCrit researcher can also test the dominant group members’ cultural privilege as a prominent contributor to systemic inequality. Considering how a research question shapes the decision-making in the subsequent research process, proposing a social justice-oriented question is an integral step for QuantCrit research.

Critiquing dominant narratives and centering the counternarratives

QuantCrit researchers can offer alternate perspectives to formulate narratives and provide tools to test narrative effects. Narratives shape reality because they have the power to either silence or give a voice to individuals, and thus legitimize (or delegitimize) the status quo ( Nelson, 2001 ). Because much scientific inquiry has been pursued through the voices of WEIRD cultures, the lived experiences of marginalized populations and their narratives have often been ignored ( Kanazawa, 2020 ). The concept of counternarratives, or narratives that reflect the perspectives of those who have been historically marginalized, emerged to resist dominant narratives ( Bamberg, 2014 ). Counternarratives empower marginalized populations to contest existing systematic oppression and create their own narratives ( Saldanha et al., 2022 ).

In the mainstream media, majority groups occupy dominant narratives and are assumed to be normative while those of minoritized groups are largely silenced or depicted as problematic ( Larson, 2006 ). Researchers studying media effects have noted that even the ostensibly positive portrayals of marginalized individuals can intensify marginalization and oppression. For example, media messages showing people with disabilities performing physically impressive or strenuous activities are often considered inspirational, but could be insulting to those with disabilities ( Ramasubramanian & Banjo, 2020 ). Such a message—termed a supercrip narrative —contributes to the dominant narrative that disability is something to overcome through individual efforts.

In this context, quantitative approaches can contribute to critiquing dominant narratives and centering the counternarratives in several ways. Even though not all alternative narratives serve to resist existing systemic oppression from a critical point of view, opening alternative ways to spur dialog can be a reasonable starting point. For instance, supercrip narratives may have other kinds of positive influences beyond inspiring the able-bodied audience. Bartsch et al. (2016) showed that empathic feelings evoked by supercrip narratives increased stronger positive attitudes and behavior intentions toward people with disabilities ( Bartsch et al., 2016 ). The task for QuantCrit researchers, then, is to investigate which message features within a particular supercrip narrative stereotype people with disabilities while other features facilitate positive intergroup outcomes. QuantCrit research can also assess the potential harm of supercrip narratives and create messages with careful consideration of possible impacts on all who might be influenced by the messages. Because counternarratives need to reflect the perspectives of marginalized populations and empower them for social transformation, it is imperative that QuantCrit researchers examine the impacts of messages on people with disabilities themselves, such as their sense of self-identity, social belonging, and empowerment.

To more actively interrogate dominant narratives, QuantCrit researchers may redefine success in the messages they create. In supercrip narratives, success is judged on the ability to conform to the norms of the able-bodied majority ( Silva & Howe, 2012 ). In the counternarrative, success could be defined as how well people live with a disability rather than defy it. Being successful could also be based on the extent to which people with disabilities self-advocate for accommodations, educate others about disability, and engage in disability activism ( Kimball et al., 2016 ). By capitalizing on quantitative analyses’ capacity to test the message effects, QuantCrit researchers are well-positioned to find answers for how narratives can be written in ways that avoid stigmatizing language and promote social identities preferred by the marginalized group.

For a different example of the dominant narrative, we can turn to health communication during the COVID-19 pandemic. With many health communication efforts advocating mask-wearing as an effective COVID-19 preventive behavior, those who do not wear masks were often regarded as noncompliant and disruptive (e.g., Lehmann & Lehmann, 2021 ). As a way to challenge this dominant narrative, QuantCrit research can examine structural influences that may limit individuals’ ability to wear masks. When there were shortages of masks during the pandemic, many laypersons used scarves and bandanas, which have long been associated with stereotypes regarding gang affiliation, violence, and criminality. Because these stereotypes are particularly relevant to certain racialized groups, the decision to wear face coverings can be dangerous and even deadly for some individuals ( MacLin & Herrera, 2006 ).

Although not explicitly employing the critical perspective, Webber et al. (2022) resisted the dominant narratives that largely ignore systematic influence by proposing experiences of racism as a critical determinant of mask-wearing behaviors for people of color. Through a cross-sectional survey data, Webber et al. (2022) showed that Black, Latinx, and Asian individuals who experienced more racism perceived more barriers to wearing masks. Furthermore, for Black and Asian participants, perceived barriers inhibited intentions to wear a mask in public. As in Webber et al. (2022) , acknowledging structural barriers faced by minoritized groups (e.g., race-based discrimination) can be a way to compose counternarratives. Quantitative research findings that reveal the influence of structural barriers on individuals’ health behaviors are invaluable because they can further inform health communication efforts to advocate structural approaches to health promotion, shifting from individual approaches. By constructing and disseminating counternarratives through research, QuantCrit researchers can contribute to addressing the historical inequities that are disproportionally experienced by marginalized populations.

Incorporating intersectionality to address marginalization

QuantCrit researchers are tasked to consider inequality and unfairness entrenched in everyday communication phenomena. A way of thinking about multiple identities and their relationships to power, intersectionality ( Crenshaw, 1991 ), can be a lens through which communication research assesses how social structures and inequitable systems of power characterize individuals’ everyday experiences. Even though intersectional approaches have often employed qualitative methods to illuminate sociohistorical forces of marginalization and to contextualize phenomena under study (e.g., Bowleg, 2008 ), several researchers have argued that intersectionality is not tied to a particular method ( Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016b ). While there are many ways of engaging in intersectionality scholarship, McCall’s (2005) conceptualization of three different intersectional approaches (i.e., anticategorical, intracategorical, and intercategorical) is particularly relevant in employing intersectionality in quantitative research. Conceptualized as existing on a continuum, the three approaches are distinguished based on how they understand and use analytical categories to explore the complexity of intersectionality.

On one end, there exists the anticategorical approach, which argues that any form of categorization essentializes and perpetuates differences and inequalities between groups. The anticategorical approach critiques and deconstructs social categories on the basis that they fail to appreciate the rich diversity and irreducible complexity of social life. While the anticategorical approach allows for assessing the specificity of discrimination as experienced at individual intersections, it poses a greater challenge to quantitative research by delegitimizing the provisional division of individuals into social categories, which serves as the basic premises to examine whether and why one social group is worse off than another ( Bauer et al., 2021 ). Falling in the middle of the continuum, the intracategorical approach acknowledges categories and focuses on a subpopulation at one or more marginalized intersectional locations. This approach analyzes complex social processes operating at a particular intersection by examining within-group differences. On the other end of the continuum lies the intercategorical approach, which adopts existing analytical categories to reveal inequalities that exist among social groups. The intercategorical approach investigates inequalities across different intersections (i.e., between-group differences). In the following section, I showcase how QuantCrit communication research can adopt intracategorical and intercateogrical intersectional approaches to address the influence of social structural factors on communication experience. 1

With its focus on Black women’s intersectional experience, Davis and Afifi (2019) present one example of the intracategorical approach. The study builds on the notion that the embodied representation of the oppression that Black women in the United States experience cannot be explained based on one social status location (e.g., either race or gender ). The Strong Black Woman Collective Theory claims that images of strong Black women, which have mostly been thought of as oppressive and detrimental to Black women’s well-being, can be functional as Black women collectively affirm strength in each other and promote solidarity to confront oppressive forces ( Davis, 2015 ). Drawn from prior research that identified strength as a defining aspect of Black women’s communication behavior, Davis and Afifi developed a new scale to measure strength regulation, or “the extent to which Black women reinforce the communication and overall embodiment of SBW [Strong Black Women] in themselves and others” (p. 3). They were then able to demonstrate the positive influence of Black women’s strength regulation on confronting hostile outsiders. The development of the strength regulation scale is enlightening, especially considering that existing measures would not accurately capture the unique lived intracategorical intersectional experiences of marginalized Black Women.

Regarding the intercategorical approach, Mora’s (2018) study provides a commendable example. The study attended to a media character Gloria Pritchett in the American Broadcasting Company’s family sitcom series Modern Family whose embodied Latinidad is simultaneously gendered and classed. Mora conceptualized intersected, social identity prototypes in Gloria Pritchett and demonstrated that her prototypical traits as a strong and confident Latina (i.e., ethnicity and gender) and American middle-classness (i.e., ethnicity and social class) predicted the character likability, whereas as the Latina spitfire trope (i.e., ethnicity and gender) predicted dislike toward the character. To test whether the audience-character likability depends on how the audience felt toward various social identities, the study recruited participants from multiple ethnicities, genders, and social classes. By testing a multiple regression model with a three-way interaction, Mora demonstrated that the likability toward Gloria Pritchett was higher when participants had strong gender, social class, and ethnic identities and when they had weaker ethnic and gender identities but a stronger social class identity. The findings that the likability of Gloria Pritchett depends on the various intersected social identities of the character and audience suggest that audiences do not understand the character exclusively in racial or ethnic terms even if the mainstream media primarily frames Gloria Pritchett in terms of race (i.e., Latinidad). Through the intercategorical approach, this study quantitatively demonstrated how the lived experience of the audience that is differentially racialized, gendered, and/or classed matters to understanding the media character.

In reviewing quantitative research that explicitly adopts or closely connects with the intersectional approach, I note a few concrete strategies for future intersectionality research. First, QuantCrit researchers should become familiar with critical scholarship that addresses socio-historical and structural inequality ( Few-Demo et al., 2014 ; Suter, 2018 ). In-depth, qualitative research findings can offer inspiration throughout the research process, but especially when determining the intersectional marginalization of focus. Second, QuantCrit researchers need to identify multiple disadvantages experienced by marginalized people. In employing the intersectional lens, it is critical to provide a rationale for the conceptualization and operationalization of social identities as they relate to various forms of inequality. Third, QuantCrit researchers may develop new scales or modify existing scales to capture intersectional experience. Marginalized populations often score worse on measures developed and normed on the majority (e.g., WEIRD Americans) because such assessments fail to capture the familial strengths and contextual resources of marginalized populations ( Curtis et al., 2022 ). Finally, intersectionality can be incorporated into any stage of research. Ideally, intersectional approaches could inform critical decision-makings at the beginning of a study, such as when proposing a research question; yet, QuantCrit researchers can also employ the intersectional lens when interpreting research findings.

Employing statistical methods that illuminate interdependence, systems, and power dynamics

Different statistical methods offer different capacities to embrace QuantCrit, due in large part to how social processes are captured (or not) by the assumptions and logic of each analysis technique (Scott & Siltanen, 2017). In this section, I discuss three techniques of quantitative analysis—multilevel modeling, social network analysis, and spatial analysis—that are easily compatible with QuantCrit given their capability to illuminate interdependence, systems, and power dynamics. For each analytical technique, I explain its logic and the assumptions on which the analysis is built, and I discuss how communication researchers can bring critical consciousness when employing the proposed analysis techniques. It should be noted that researchers’ goals of applying the techniques and ways of interpreting the analysis results make a study critically oriented, not a particular statistical method per se. I caution that without researchers’ critical consciousness, analysis techniques described here could inadvertently be used to undermine the goals of QuantCrit research. Moreover, I stress that many other statistical methods can be employed in QuantCrit research to pursue social justice and equity goals; more examples of statistical methods for QuantCrit research are available elsewhere (e.g., Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016b ; Evans et al., 2020 ; Scott & Siltanen, 2017 ).

Multilevel modeling could be used to reveal the interdependence of individuals’ experiences who are nested within groups (e.g., neighborhood, county, and state; Snijders & Bosker, 2012 ). My intention here is to highlight the implications of examining cross-level interactions in multilevel modeling for social justice and equity-oriented communication research. Examining interaction effects helps investigate multiplicative effects that may reveal inequalities and marginalization over and above additive effects of multiple explanatory variables ( Scott & Siltanen, 2017 ). Even though various statistical models can examine interaction effects (e.g., ANOVA, regression, etc.), multilevel models are especially promising for QuantCrit research because they take into account various higher-level contexts and thus allow for assessing cross-level interactions.

The call for creating cross-level theory and research in the communication field is not new ( Slater et al., 2006 ). Communication infrastructure theory (CIT; Kim & Ball-Rokeach, 2006a ) offers an example of communication theory that considers cross-level interaction effects. Grounded in the ecological perspective that emphasizes how organisms interact with their environment, the CIT theorizes that each community has a communication infrastructure comprised of a neighborhood storytelling network embedded in a communication action context ( Kim & Ball-Rokeach, 2006a ). Many quantitative studies on the CIT measured the extent to which individuals are integrated into a neighborhood storytelling network and predicted its impact on civic engagement in various contexts; however, the influence of a communication action context has rarely been considered. Notably, Kim and Ball-Rokeach (2006b ) referred to census data to examine two aspects of communication action context: ethnic heterogeneity and residential stability. In a multilevel model predicting civic engagement outcomes, Kim and Ball-Rokeach assessed the effects of individual-level variables (i.e., the extent to which participants are integrated into a neighborhood storytelling network), neighborhood-level effects (i.e., ethnic heterogeneity and residential stability of the census tract in which each participant resides), and cross-level interactions between the two. Study findings demonstrated the cross-level interaction effects such that the connectedness with a neighborhood storytelling network was particularly important in predicting civic engagement in heterogeneous and unstable areas. Kim and Ball-Rokeach discussed that ethnically fragmented and unstable neighborhoods make it challenging for residents to generate and accumulate neighborhood stories, which in turn, result in heavy reliance on a neighborhood storytelling network for civic engagement. Cross-level interaction effects in this study illuminate the need to address social systems and associated inequalities that shape individuals’ everyday experiences. QuantCrit researchers may capture multiple forms of structural discrimination by incorporating various types of contextual-level information, such as inequality indexes, social norms, and public policies.

In addition to multilevel modeling, statistical techniques like social network analysis and spatial analysis are particularly attentive to structural influences. Social network analysis includes the means by which to examine the pattern of relationships (i.e., ties) among a set of actors (i.e., nodes), actors’ positions within the system of relationships, and the characteristics of a system based on the relationships within it ( Wasserman & Faust, 1994 ). Drawing on the assumption that network structure has significant implications on the outcomes of interest, social network analysis adopts the interdependent view of social processes over an individualist view ( Smith, 2014 ). In comparison to a non-relational study design where the data typically capture individuals’ attributes, social network analysis requires the collection and analysis of relational data that capture dyadic ties between actors ( Wasserman & Faust, 1994 ).

With its focus on social interaction as a potential driver of individual- and aggregate-level outcomes, social network analysis can provide valuable insights into QuantCrit research, including understanding the structure of a network that influences actors’ capacity to (un)thrive, uncovering the influences of social interaction on population-level inequalities, and examining the diffusion (or centralization of) innovations like new ideas and technologies within the network. Importantly, social network analysis can be utilized to design and implement “network interventions” ( Valente, 2012 , p. 49). Based on social network analysis of the data collected from households ( N = 3,763) in 10 different communities in Namibia, Smith (2009) recommended network interventions to address HIV for a majority of communities, with suggestions that varied based on each community’s characteristics. Because the higher network centrality score indicates that more community members participate in a particular social group, health campaigns in such communities should work with the centralized social group, such as a local church. In other cases, social network analysis identified individuals with centralized positions, who can act as opinion leaders or super diffusers to spread health information ( Smith, 2009 ). Some other strategies that can be implemented in network interventions include identifying and targeting vulnerable populations ( Pagkas-Bather et al., 2020 ) and promoting peer-to-peer education ( Hunter et al., 2019 ), which could all be means for QuantCrit researchers to drive social justice and equity-oriented change.

Whereas social network analysis understands the phenomena from a relational perspective, spatial analysis adopts a geographical perspective to examine data in a spatial context. The underlying assumption of spatial analysis is that the geographical area one lives in affects one’s access to resources and opportunities as well as exposure to risks. Spatial data refer to data for which locational attributes serve as critical sources of information, which can be collected from various sources such as geometric data that map the spatial information and geographic information that captures the latitude and longitude of a location ( Downey, 2006 ). In social science, spatial analysis has increasingly been utilized to understand spatial relationships and patterns, engaging with concepts like location, proximity, boundaries, and neighborhood effects ( Goodchild & Donald, 2004 ). Of particular relevance to QuantCrit research is the use of spatial analysis to reveal the importance of neighborhood effects and spatial patterns of inequality and marginalization.