Exploring The Rich Diversity Of Human Languages

- Translation & ESL Tutoring

- Computational Linguistics

- Geolinguistics

- Historical Linguistics

- Language Acquisition

- Language Families

- Language & Mind

- Language Policy

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics & Phonology

- Semantics & Pragmatics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation

- Australia & Papua New Guinea

- Central Asia

- East & Southeast Asia

- Oceania & Madagascar

- Russia, Ukraine & the Caucasus

- Southwest Asia & North Africa

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- The Americas

- “Russia Beyond the Russians”

- Old Church Slavonic

- Language, Thought, Culture: A Reassessment

- Recommended Blogs

- Books on Language and Linguistics

- Language Maps

- Sound Recordings and Other Useful Links

- About The Author

- Books by Asya Pereltsvaig

On the Indo-European homeland

Apr 26, 2011 by Asya Pereltsvaig

Lately, I have been posting on the study by Dr. Atkinson from the University of Auckland, New Zealand on the origins on human language. He has also published recently another article (with Russell D. Gray) on the origins of the Indo-European language family.

As with the study on the origins of human language, Atkinson’s research published in Nature applies computational methods derived from evolutionary biology, this time to one of “the most intensively studied, yet still most recalcitrant, problem of historical linguistics”, the problem of the Indo-European homeland. As J. P. Mallory once put it:

“One does not ask ‘where is the Indo-European homeland?’ but rather ‘where do they put it now?'”

Although there is no consensus on where exactly the speakers of Proto-Indo-European lived, the most commonly accepted theory since the 1970s remain the Kurgan Hypothesis, proposed in 1956 by a Lithuanian-American archaeologist Marija Gimbutas. She was one of the first scholars to combine evidence from archeology and linguistics. Specifically, she proposed that the original speakers of Proto-Indo-European were a nomadic tribe in Eastern Ukraine and Southern Russia associated with what archaeologists identify as the “Kurgan culture”, so named after the distinctive Kurgan burial mounds in the Pontic steppe (flatland). According to this theory, speakers of Proto-Indo-European spread on horseback throughout the Pontic-Caspian steppe around 5,000 BCE and into Eastern Europe by the early 3rd millennium BCE.

One strong argument in favor of the Kurgan hypothesis is the fact that Proto-Uralic is the only non-Indo-European language whose lexicon appears to contain loanwords from Proto-Indo-European, such as the words * śata ‘hundred’ and * porćas ‘pig’. For such borrowing from Proto-Indo-European into Proto-Uralic, to be possible Proto-Indo-European must have been spoken in reasonable proximity to Proto-Uralic, which at least some scholars associate with the Pit-Comb Ware culture to the north of the Kurgan culture in the fifth millennium BCE.

But despite its mainstream status, the Kurgan Hypothesis has been challenged by various scholars throughout the years. Even a brief review of all (or most) competing theories will take us too far afield, so I will focus here on the main competitor of the Kurgan hypothesis, the Anatolian theory, advanced by Colin Renfrew, a British archaeologist and archeogeneticist.

Renfrew’s answers to both the “where” and “when” questions are different from Gimbutas’s. According to the Anatolian theory, the speakers of Proto-Indo-European lived before the people of the Kurgan culture, about 7,000 BCE, and their homeland was not in the Pontic steppes but further south, in Anatolia (present-day Turkey), from where they later diffused into Greece, Italy, Sicily, Corsica, the Mediterranean coast of France, Spain, and Portugal, while another group migrated along the fertile river valleys of the Danube and Rhine into Central and North Europe. This course of diffusion is correlated with the spread of agriculture, which can be traced through archaeological remains. One of the main problems facing this theory is the fact that ancient Asia Minor is known to have been inhabited by non-Indo-European people, such as Hattians (later replaced by speakers of Hittite, also an extinct language) and others.

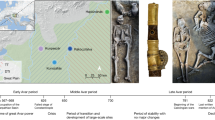

The contribution of Gray and Atkinson’s study is in the additional evidence they provide for the Anatolian hypothesis based on their analysis of a matrix of 87 languages with 2,449 lexical items that produced an estimated age range for the initial Indo-European divergence of between 7,800 and 9,800 years ago (or about 5,800-7,800 BCE).

Yet the two theories, the Kurgan theory and the Anatolian theory, may prove not to be as mutually exclusive as they seem. This becomes especially true as genetic studies are bringing new elements (and new solutions!) to the puzzle. For example, Luca Cavalli-Sforza and Alberto Piazza have suggested that Colin Renfrew’s Anatolian Hypothesis and Marija Gimbutas’s Kurgan Hypothesis need not contradict each other: after all, it is possible -– and genetic studies seem to support this -– that the same people who originated in Asia Minor had first migrated to the area of the Pontic steppes and from there expanded into Central and Northern Europe. A 3,500-year period would have elapsed between the time of the Proto-Indo-European speakers’ sojourn in Anatolia and their appearance in the area of the Kurgans. While Colin Renfrew maintains that the Proto-Indo-Europeans in Anatolia were agriculturalists, it is possible that they could have reverted to a pastoral culture as an adaptation to the environment. Here is how Piazza & Cavalli-Sforza (2006) explain this:

“…if the expansions began at 9,500 years ago from Anatolia and at 6,000 years ago from the Yamnaya culture region, then a 3,500-year period elapsed during their migration to the Volga-Don region from Anatolia, probably through the Balkans. There a completely new, mostly pastoral culture developed under the stimulus of an environment unfavorable to standard agriculture, but offering new attractive possibilities. Our hypothesis is, therefore, that Indo-European languages derived from a secondary expansion from the Yamnaya culture region after the Neolithic farmers, possibly coming from Anatolia and settled there, developing pastoral nomadism.”

Overall, the genetic findings to date provide the strongest support to Gimbutas’s model of Indo-European spread from the southern Russian steppe, and there is little evidence for a similarly massive migration of agriculturalists directly from the Asia Minor.

Like this post? Please pass it on:

Related posts.

Posted on Oct 25, 2015

Posted on Jun 17, 2015

Posted on Apr 2, 2015

Posted on Feb 28, 2015

Like This Post? Please Pass It On:

Subscribe For Updates

We would love to have you back on Languages Of The World in the future. If you would like to receive updates of our newest posts, feel free to do so using any of your favorite methods below:

- Anatolian hypothesis

- Cavalli-Sforza

- homeland problem

- Indo-European

- Kurgan hypothesis

- Proto-Indo-European

About Languages Of The World

USEFUL RESOURCES

Looking for essays for money ? Best custom writing company is here to assist.

Crosswords Zone - The crossword clues and answers database

My Paper Done has 500+ experts on board to help you with writing tasks.

Need to figure out who can write my essay best website ? Essaypro is your solution.

Advertisement

Want to advertise on languages of the world.

If you have a great product or service you'd like to let our targeted audience know about, you can sponsor the development of this site with your promotion.

Copyright © 2024 LanguagesOfTheWorld.info . All Rights Reserved | Privacy Policy

Site created by K&J Web Productions

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Beginnings of Patriarchy in Europe: Reflections on the Kurgan Theory of Marija Gimbutas

An investigation of the beginnings of patriarchy in Europe is more than an intellectual exercise. Its path crosses the boundaries of archaeology, anthropology, gender studies, history, linguistics, mythology, genetics, among other disciplines, and inevitably leads to a constellation of assumptions, interpretations and beliefs about the origin story of European civilization. Patriarchy has been defined as the social arrangement in which men possess structural power by monopolizing high-status positions in important social, economic, legal, and religious institutions (Glick and Fiske 2000:373). As a designation of social structure, it is associated with patrilineal inheritance and a patrilocal system of residence. Patriarchy typically promotes warfare which further intensifies male dominance on every level of society (see Christ 1997:6062). While there is no universal consensus about exactly how and when full-fledged patriarchal institutions were first established in Europe, it is cle...

Related Papers

Feminist Theology

Joan Marler

... of ancient societies is the indolent assumption that they must have resembled our own the existence of a different world is the hardest thing to admit'.50 Marija Gimbutas had a long and esteemed career in archaeology before she was discovered by the Goddess movement. ...

This article surveys literature on history, archaeology, and ethnography, from Lafitau, Morgan, Marx and Engels to Matilda Joslyn Gage and Barbara Mann, Bachofen to Jacquetta Hawkes. It also proposes that patriarchy is a historical development, questions functionalist interpretations of myths (or oral histories) of male takeovers. It looks at the furor over the work of Marija Gimbutas, Eller's charges of "essentialism" and "goddess monotheism," and theories about whether patriarchal social organization originated among foragers or agriculturalists. All the heated rhetoric about "matriarchy" avoids the real issue, which is the existence of cultures that did not enforce a patriarchal double standard or make females legal minors ruled by fathers, brothers, and husbands. Matricultures still exist today in some parts of the world, albeit under threat as all Indigenous cultures are. Whatever terminology we choose to use for them is not the point; it is that they existed and have existed in the past.

Joan, Eahr Amelia. Re-Genesis Encyclopedia: Synthesis of the Spiritual Dark– Motherline, Integral Research, Labyrinth Learning, and Eco–Thealogy. Part I. Revised Edition II, 2018. CIIS Library Database. (RGS.)

A new upheaval throughout east-central Europe caused by Kurgan Wave (or Jamna) from the lower Dnieper–lower Volga steppe. Ethnic shifts: late Baden and Vucedol into Bohemia and central Germany, Bosnia, and the Adriatic coast. Long range wanderings of the Bell Beaker people (probably “Kurganized” * central Europeans) into Western Europe. Formation between Rhine and Dnieper of the Corded Ware complex from the fusion of the globular Amphora, funnel–necked Beaker cultures, and new eastern (Jamna) elements, followed by the wide dispersal of the Corded Pottery carriers to southern Scandinavia, the East Baltic, and areas of the upper Dnieper and upper Volga (CB: 251). war-oriented ‘dominator model,’ sky–thunder god, Indo–European culture. CB: 250-251; COG: 351-401.)

Major social and economic changes took place in Europe within the 4th and 3 millennia BC resulting in the establishment of Bronze Age societies. Gimbutas’ Kurgan Hypothesis remains the most consistently debated explanation of these changes, which she described as ‘a collision of culture’ resulting in radical transformations of ideology and social structure. The peoples from north of the Black Sea (Proto–Indo–European speakers whom Gimbutas named Kurgans) began entering Europe after 4400 BC lived in small bands and, Gimbutas writes, ‘their encroachment on Old Europe cannot be thought of an organized massive invasion of the type we know from historical times’. Nevertheless, when their barrow–type graves appeared in Europe for the first time (primarily containing males with weapons), nearly 700 major habitation sites representing a rich fabric of cultural and technological developments, disintegrated after flourishing undisturbed for many hundreds of years. According to archaeologist, James Mallory, in his landmark In Search of the Indo-Europeans: ‘The Kurgan solution is attractive and has been accepted by many archaeologists and linguists, in part or total’ (MU: 179).

Irene Friesen Wolfstone

Harvey B Smith

Massimo Izzo

For a century a notion of a prehistoric Mother Goddess has infused some perceptions of ancient Europe, whatever the realities of developing archaeological knowledge. With the reverent respect now being given to Marija Gimbutas, and her special vision of a perfect matriarchy in Old Europe, a daughter-goddess is now being made, bearer of a holy spirit in our own time, to be set alongside the wise mother of old.

Old Europe refers to the Neolithic (New Stone Age) and Chalcolithic Age (Copper Age) of Europe or pre-Indo–European period that theoretically flourished and flowered for 2,000 years between 6500 to 4500 BCE. The area includes: the Aegean; Adriatic; central and east Balkans; east-central Europe; Anatolia; Near East central; Mediterranean; Minoan (or Chthonian Crete according to Mara Keller); Thera; Malta; and western Europe reflecting cultural continuities from Upper Paleolithic times, till the onset of its demise beginning with the Kurgan invasions in 4500 BCE. Gimbutas suggests that the area from the Aegean and Adriatic seas and islands, as far north as Czechoslovakia, southern Poland and western Ukraine also reflect contemporaneous patterns in Africa including Egypt as well as Mesopotamia, Syro-Palestine, and the Indus Valley. (COG: vii-x; GGE: 17; MK.)

3400-3000, Wave II of Kurgan/Indo-European Invasions.

Volga steppe region and North Pontic Kurgan intrusions into Old Europe significantly disrupted and dislocated the Karanovo, Vinca, Petresti, and Lengyel cultures. General area is east-central Europe. As a result of these “Kurganized” invasions, Old Europe was subordinated and subsequently hybridized by the horseback riding warriors known as Indo–Europeans or Kurgans, named for their Kurgan long–barrow or ‘pit grave’ burials. Origins of Kurgans include the Volga and the North Pontic or Russian steppe zone, area to the north and east of the Black Sea. The full spectrum of warlike clans incorporated: Indian Aryans; Hittites; Mittani; Luwians; Achaeans and later Dorians, plus Semitic tribes. (CB: 44-5.) They not only came from the north, but also from the southern deserts below Canaan.

RELATED PAPERS

Jeri Studebaker

Živa Antika / Antiquité Vivante

Journal of Indo-European Studies 42, 101-143.

aleksandar bulatovic

Mario Alinei

Some Problems of the Interrelation of Caucasian and Anatolian Bronze Age Cultures,

Giorgi Kavtaradze

The Rule of Mars: Readings on the Origins, History and Impact of Patriarchy, Cristina Biaggi, ed. Manchester, Ct: Knowledge, Ideas & Trends, Inc. pp. 143-154

Miriam Robbins Dexter

The Journal of Indo-European Studies

Axel Kristinsson

in Diane Bolger (ed.), A Companion to Gender Prehistory, First Edition 2013, John Wiley & Sons, p. 413-437

Nona Palincas

SHAMANISTIC SCOPES IN A CHANGING WORLD

Emilia Pasztor

Migration, ancient DNA, and Bronze Age pastoralists from the Eurasian steppes.

David Anthony

Annual Review of Anthropology

Martin B Richards

Ernestine Elster

Jeyakumar Ramasami

Goddesses in Myth, History and Culture. Mary Ann Beavis and Helen Hye-Sook Hwang, eds. (Lytle Creek, CA: Mago Books, 2018). ISBN-13: 978-1976331022; ISBN-10: 1976331021

Mara L Keller

Fowler, C. - Harding, J. - Hofmann, D.: The Oxford Handbook of Neolithic Europe

Svend Hansen

Nikoloz Silagadze

Harald Sverdrup

Timothy Parsons

Carlos Quiles

Karel J Giffen

Transactions of the Philological Society

Colin Renfrew

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

May 1, 2016

12 min read

Farmers vs. Nomads: Whose Lingo Spread the Farthest?

Did the most successful family of languages in history originate in Turkey or the Pontic steppes? New evidence from DNA and evolutionary biology has only heightened the scientific disagreements

By Michael Balter

Mark Allen Miller

“What's in a name?” asked Juliet of Romeo. “That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” A real-life Juliet probably would have spoken to Romeo in an obscure medieval Italian dialect rather than Shakespeare's English. Nevertheless, her word for the sweet-smelling flower would have shared the same linguistic root ( rosa , in modern Italian) as the English version does and indeed as many other languages spoken throughout Europe do— Rose , capitalized in German fashion, or the lowercase French rose . Croatian? An aromatic ruža . To the nearly 60,000 Scots who still speak the ancient Scottish Gaelic, this symbol of passionate love is a ròs .

Why do such geographically diverse languages use similar words for the same flower? All these tongues, along with more than 400 others, belong to the same family of languages—the incredibly far-flung Indo-European language family—and have a common origin. Indo-European languages, which include Greek, Latin, English, Sanskrit, and many languages spoken in Iran and on the Indian subcontinent, are the most dominant linguistic group in the history of humanity. They account for about 7 percent of the world's estimated 6,500 languages but are nonetheless spoken by three billion people—nearly half the world's population. Understanding how, why and when they spread so readily is key to understanding the social, cultural and demographic changes that created today's diverse populations in Europe and much of Asia. As Paul Heggarty, a linguist at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany, puts it: “We have to explain why Indo-European was so outrageously, overpoweringly successful.”

Because words and languages do not fossilize, the task of tracking their movements across time and space was left for more than a century to traditional linguists and a small number of archaeologists. Recently, however, the search for Indo-European origins has gone high tech, as biologists and experts in ancient DNA have gotten into the act. Armed with new theoretical and statistical approaches, these investigators have begun to transform linguistics from a paper-and-pencil exercise into a field that uses powerful computers and methods borrowed from evolutionary biology to trace language origins.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

You might think that this attempt to modernize linguistics would bring researchers closer to an understanding of where and when the Indo-European languages arose. But in many ways, the opposite has happened, and the question is in even greater dispute. Everyone agrees on one key point: the Indo-European languages descend from a common ancestor, a mother tongue called Proto-Indo-European, or PIE. But as to why this particular language produced so many linguistic offspring or where it originated, there is no accord.

Researchers have fallen into two warring camps. One camp, which includes the majority of traditional linguists, argues that Central Asian nomads, who invented the wheel and domesticated the horse, spread the mother tongue throughout Europe and Asia beginning about 6,000 years ago. The other camp, led by British archaeologist Colin Renfrew, credits early farmers from more than 500 miles to the south in what is now Turkey with disseminating the language at some point after they began spreading their agricultural know-how 8,500 years ago.

Over the years first one idea then another has had the upper hand. Evolutionary biologists published a series of studies in 2003 that concluded that the Indo-European family tree originated in the Middle East at least 8,000 years ago, based on the idea that the evolution of words can mimic the evolution of living organisms; their results are consistent with the farmer hypothesis. In the past year or two some linguists, archaeologists and geneticists struck back, using rival computational analyses and samples of DNA from ancient skeletons to support the nomad hypothesis. And so the pendulum continues to swing.

The Horse, of Course

Scholars did not have to wait for high-speed computers to recognize connections among the Indo-European languages. That realization dawned as early as the 1700s, after Europeans had begun to travel far afield. Some of the parallels among widely distributed tongues are now seen as dead giveaways. Thus, the Sanskrit and Latin words for “fire,” agní - and ignis , clearly indicate their Indo-European family ties.

By the 19th century, linguists were sure there must be a common ancestor for all Indo-European languages. “There was a sense of shock that the classical languages of European civilization sprang from the same source as Sanskrit, an exotic language spoken in India, on the other side of the world,” says David Anthony, an archaeologist at Hartwick College and a fierce advocate of PIE's nomadic origin.

So linguists set about reconstructing this ancestral tongue. Sometimes this was not too difficult, especially if the original word had not changed unrecognizably. For example, linguists could take the English word “birch,” the German Birke , the Sanskrit bhūrjá and other Indo-European words for this slender tree and, by applying basic linguistic rules of language change, extrapolate backward to figure out that the PIE root was something like * bherh 1 ǵ - (the asterisk indicates that this is a reconstructed word for which there is no direct evidence). Other reconstructions are not as obvious. Thus, the PIE word for “horse”— áśva - in Sanskrit, híppos in Greek, equus in Latin and ech in Old Irish—was determined to be * h 1 éḱwo (the subscript 1 refers to a sound made in the back of the mouth).

But when some linguists tried to identify the peoples behind the language, things became trickier. These scholars began linking certain cultures with PIE, an approach called linguistic paleontology. They noticed that PIE contained many terms for domesticated animals, such as horses, sheep and cattle, and began postulating a pastoral Indo-European “homeland.”

That approach eventually led to trouble. In the early 20th century German prehistorian Gustaf Kossinna proposed that a group of Central European settlers, who created intricately engraved pottery called Corded Ware starting 5,000 years ago, were in fact the first Indo-Europeans. Kossinna argued that they later spread out of what is today Germany, carrying their language with them. That idea was music to the ears of the Nazis, who resurrected the term “Aryan” (a 19th-century term for Indo-Europeans), along with its connotations of racial superiority.

The Nazi endorsement gave Indo-European studies a bad name for many years. Many researchers give credit to Marija Gimbutas, an archaeologist who died in 1994, for making the subject respectable again, starting in the 1950s. Gimbutas situated the origins of PIE in the so-called Pontic steppes north of the Black Sea. For her, the prime mover of PIE was the Copper Age Kurgan culture, which can first be identified in the archaeological record about 6,000 years ago. After a millennium of roaming the barren steppes—in which the nomads learned how to domesticate the horse—Gimbutas argued, they charged forth into Eastern and Central Europe, imposing their patriarchal culture as well as the strongly enunciated vowels and consonants of their native Indo-European language. More specifically, Gimbutas identified the Yamnaya people, who lived in the Pontic steppes between about 5,600 and 4,300 years ago, as the original PIE speakers.

Other researchers also found evidence to support such a view. In 1989 David Anthony began working in Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan, focusing on horse teeth that had been earlier excavated by Soviet archaeologists. Anthony and his colleagues confirmed previous suggestions that there was bit wear on teeth dated as early as 6,000 years ago, pushing back the earliest evidence for horse domestication—and horse riding—by about 2,000 years. Their studies also provided evidence to link several technological developments—including the use of wheeled vehicles such as chariots—to the Yamnaya people. These finds supported the idea that the steppe pastoralists had the necessary transportation and technology to fan out rapidly from their homeland and spread their language in all directions.

Revolutionary Farmers

The steppe hypothesis, also known as the kurgan hypothesis, after the kurgans, or burial mounds, in which the pastoralists buried their chiefs, was rarely questioned until the 1980s. Then Renfrew put forth a radically different idea, called the Anatolian hypothesis. ( Anatolia , from the Greek for “sunrise,” refers to present-day Turkey.) Renfrew, the dean of British prehistorians, who now sits in the House of Lords, had spent years digging in Greece and was struck by how much the artifacts he unearthed, especially the carved female figurines, resembled those from earlier archaeological sites in Turkey and the Middle East.

Archaeologists already knew that farming spread from the Middle East to Greece first. Renfrew wondered if there might be a continuity of language in addition to culture. Thus, the first PIE speakers, he posited in lectures and a book, might be the farmers who moved from Anatolia to Europe 8,500 years ago, bringing their words along with their agricultural practices.

Traditional linguists, who had spent decades working painstakingly with paper and pencil to reconstruct PIE by tracing modern Indo-European words back to their original roots, were outraged. Most dismissed the Anatolian hypothesis, sometimes with bitter invective. One University of Oxford professor called the idea “rubbish,” and another skeptic declared that “a naive reader would be grossly misled by the simplistic solutions that the author offers.”

Renfrew and his supporters fought back, arguing that the steppe hypothesis cannot explain the broad expansion of PIE from wherever it began across both Europe and Asia. Researchers know that PIE-derived languages were spoken as far west as Ireland and as far east as the Tarim Basin, in what is now northwestern China, and down into India. A key question is how PIE would have gotten from the steppes to East Asia if the kurgan hypothesis were right. Did it spread to the north around the Black and Caspian seas, as in the steppe hypothesis? Renfrew sees no archaeological evidence for this route. Or did PIE take a southerly and earlier path to the east from Anatolia? He thinks it more likely that PIE spread south around the Black Sea from Turkey and then along early trade routes through Iran and Afghanistan.

Thus, Renfrew believes, only an Anatolian origin can account for PIE's simultaneous spread to the east and west because the peninsula offers the best historical evidence of movement between the European and Asian continents. And the only sociotechnological driver powerful enough to propel the language so far in opposite directions, he adds, was the advent of agriculture, which appeared in the Fertile Crescent—just south and east of modern Turkey—roughly 11,000 years ago. This transition of human society from hunter-gatherers into settled farming communities marked the so-called Neolithic Revolution and was “the only big thing that happened on a Europe-wide basis,” Renfrew says. “If you wanted a simple theory for the coming of the Indo-European languages, the Neolithic was the best thing to hang it on.”

Emblematic of the linguists' objections to Renfrew's Anatolian hypothesis is the origins of the word “wheel.” The reconstructed PIE root is * k w ék w lo -, which became cakrá - in Sanskrit, kúklos in Greek and kukäl in Tocharian A, an extinct Indo-European language of the Tarim Basin. The earliest evidence for wheeled vehicles—depictions on tablets from ancient Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq)—dates to about 5,500 years ago. The actual remains of wagons and carts show up in kurgans beginning about 5,000 years ago.

Many linguists have argued that the PIE root for “wheel” could not have arisen until the object was invented, and so PIE cannot be much earlier than 5,500 years—or about 5,000 years after the invention of agriculture. “That doesn't mean the PIE speakers invented wheels,” Anthony says, “but it does mean that they adopted their own words for the various parts of wheeled vehicles.”

But Renfrew and others counter that the word * k w ék w lo - derives from a much earlier root meaning “to turn” or “to roll” and only later was adapted as a name for the wheel. “There was a whole language about rotation before the wheel was invented,” Renfrew says.

Andrew Garrett, a linguist at the University of California, Berkeley, and proponent of the steppe hypothesis, agrees that the PIE word for “wheel” has an earlier derivation, the root *k

w el(h)-, which probably meant “turn” or “roll.” He says that the word * k w ék w lo - was formed by duplicating that root, putting the *k w e- part into the word twice. “It would be as if I saw a wheel for the first time,” adds Garrett's graduate student, Will Chang, “and I called it a ro-roller.” That might seem a point for Renfrew's position, but Garrett argues that while such duplications were common in PIE when forming verbs, they were “extremely rare” when forming nouns, which suggests to him and other linguists that * k w ék w lo - must have developed as a word close to the time wheels were invented.

Contested Evidence

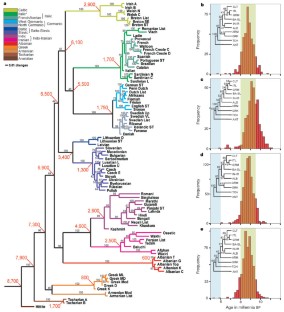

Renfrew's Anatolian hypothesis was facing an uphill battle when, in 2003, a bombshell landed in the middle of the debate from an entirely unexpected direction—the field of evolutionary biology. Russell D. Gray, a biologist who had made his early reputation studying bird cognition, and Quentin D. Atkinson, then his graduate student at the University of Auckland in New Zealand, used state-of-the-art methods from computational biology to date the origins of PIE. Gray and Atkinson adapted an earlier linguistic technique called glottochronology, which compared the proportion of cognates—words with shared roots—in different languages to determine how long ago they diverged. Glottochronology had long been out of favor because it required linguists to assume that words change their form steadily over time—something they knew was not true. Gray and Atkinson employed a new and improved version of glottochronology, along with other statistical techniques used to determine the evolutionary trees of living organisms. Their database included cognates from 87 Indo-European languages, including Hittite, an extinct language that had been spoken in Anatolia.

The results were a slam-dunk for the Anatolian hypothesis. No matter how the pair crunched the numbers, the divergence of Indo-European languages from PIE came out no later than about 8,000 years ago—or nearly 3,000 years before the apparent invention of the wheel. Despite howls of objection from some linguists that words do not change the way that living organisms and genes do, the paper was highly influential and gave a big boost to the Anatolian hypothesis. Gray, who is now co-director of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History (where Heggarty works), says that he and Atkinson were simply bringing linguistics into the 21st century.

Moreover, although Gray and Atkinson found that the initial spread of PIE tracked the spread of farming, they also detected a second divergence 6,500 years ago, which led to the Romance, Celtic and Balto-Slavic languages. The Anatolian and steppe hypotheses “need not be mutually exclusive,” they concluded.

Indeed, subsequent analyses favored the Anatolian hypothesis so strongly that some younger linguists began to call for older linguists to drop their objections. “Traditional linguistic objections to the Anatolian hypothesis are now wearing a little thin,” Heggarty wrote in a June 2014 commentary in Antiquity .

Calls for advocates of the steppe hypothesis to surrender, however, may have been premature. Beginning in 2013, Garrett and Chang launched their own analysis, using Gray's methodology. But the Berkeley researchers made an assumption that Gray's team did not: They “constrained” certain languages to be ancestral to their descendants, based on what they insist is solid historical evidence. Thus, they assumed, for example, that Classical Latin was directly ancestral to Romance languages such as Spanish, French and Italian. Gray and Atkinson, in contrast, allowed for the possibility that some as yet unidentified form of popular Latin spoken in the streets of Roman cities was the true ancestor of the Romance languages.

Garrett and Chang's results, published last year in Language , were also a slam-dunk—but for the steppe hypothesis, not the Anatolian hypothesis. Despite this apparent new life for the steppe hypothesis, Heggarty argues that Garrett's team is wrong to assume that some ancient languages are directly ancestral to others. Even small differences in Classical versus “Vulgar” Latin could throw off Garrett's estimates, Heggarty argues.

Garrett remains unconvinced. “For many of these languages we know quite a bit about the speech communities and the history of the languages,” he says. “Best understood are Greek and Latin. It isn't likely that there are other varieties of Greek and Latin floating around that we don't know about.”

Gray, for his part, calls the Language paper that used his own methods against the Anatolian hypothesis “a lovely piece of work” that really engages with the methods “rather than just saying [that Atkinson and I] are wrong.” Yet since turnabout is fair play, Gray's team has now started recrunching Garrett's data, but letting the data decide whether some languages are ancestral to others rather than assuming it. Although this work is preliminary and still unpublished, Gray and his colleagues are finding that the numbers again come up trumps for the Anatolian hypothesis.

New Clues from DNA

If the words themselves cannot tell us who is right, perhaps more evidence from outside the field of linguistics could help tip the balance. The latest genetic studies, at least, seem to favor the steppe hypothesis. Anthony and an international team of ancient DNA experts sequenced samples of genetic material from 69 Europeans who lived between 8,000 and 3,000 years ago, including nine skeletons from Yamnaya sites in today's Russia, and compared the DNA samples with those from four skeletons of the later Corded Ware culture of Central Europe.

Amazingly, the Corded Ware people, whose culture spread across Europe as far as Scandinavia, could trace three quarters of their ancestry to the Yamnaya people, and this Yamnaya genetic signature is still found in most Europeans today. So the Yamnaya, along with their genes and possibly their language, did indeed sweep out of the steppes in massive numbers, probably about 4,500 years ago. These results are a “smoking gun” that such massive migrations did take place out of the steppelands, says Pontus Skoglund, an ancient DNA expert at Harvard Medical School who was not involved in the paper but works in the laboratory of one of its authors. They “level the playing field” between the two hypotheses, he adds.

Unless, of course, this migration was a “secondary” wave that carried later Indo-European languages with it but not the original mother tongue, Proto-Indo-European. Such an interpretation, the pro-Anatolian researchers counter, would fit with the conclusions of Gray's 2003 study that pointed to the possibility of a later migration out of the steppes.

Will we ever know who is right? New evidence from ancient DNA for the spread of steppe peoples eastward into Siberia around 4,700 years ago could potentially overcome one of Renfrew's key objections to the steppe hypothesis, but it offers no proof about which languages went with them. One thing is sure: researchers will continue to debate the issue in whatever language their ancestors bequeathed them.

Michael Balter is a freelance journalist, whose articles have appeared in Audubon , National Geographic and Science , among other publications.

Indo-European languages: new study reconciles two dominant hypotheses about their origin

Profesor Titular (lingüística, traducción), Universitat Jaume I

Disclosure statement

Kim Schulte has worked on "IE-CoR: A Database on Cognate Relationships in ‘core’ Indo-European vocabulary ", funded by the Department of Linguistic and Cultural Evolution at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

Universitat Jaume I provides funding as a member of The Conversation ES.

View all partners

The languages in the Indo-European family are spoken by almost half of the world’s population. This group includes a huge number of languages, ranging from English and Spanish to Russian, Kurdish and Persian.

Ever since the discovery, over two centuries ago, that these languages belong to the same family, philologists have worked to reconstruct the first Indo-European language (known as Proto-Indo-European) and establish a “language family tree”, where branches represent the evolution and separation of languages over time. This approach draws on phylogenetics – the study of how biological species evolve – which also provides the most appropriate model for describing and quantifying the historical relationships between languages.

Despite numerous studies, many questions still remain as to the origin of Indo-European: where was the original Indo-European language spoken in prehistoric times? How long ago did this language group emerge? How did it spread across Eurasia?

Anatolia or the Pontic Steppe?

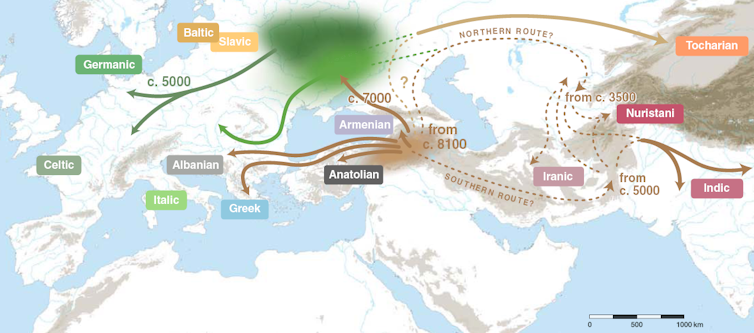

There are two main, though apparently contradictory, established hypotheses. On one side we have the Anatolian Hypothesis , which traces the origins of the Indo-European people to Anatolia, in modern day Turkey, during the Neolithic era. According to this hypothesis, created by British archaeologist Colin Renfrew , Indo-European languages began to spread towards Europe around 9,000 years ago, alongside the expansion of agriculture.

On the other side we have the Steppe Hypothesis , which places the origin of Indo-European languages further north, in the Pontic Steppe . This theory states that Proto-Indo-European language emerged somewhere north of the Black Sea around 5,000 or 6,000 years ago. It is linked to Kurgan culture , known for its distinctive burial mounds and horse breeding practices.

DNA comparison

In order to decide which of these two hypotheses is correct, genetic studies have been carried out to compare DNA found at prehistoric sites with that of modern humans. However, this type of research can only provide indirect clues as to the origins of Indo-European languages, since language, unlike, for example, blood type, is not inherited through genes.

A new study published in Science has approached the question from a different angle by using direct linguistic data to assess the timelines put forward by both hypotheses.

In this project, carried out by over 80 linguists under the direction of Paul Heggarty and Cormac Anderson from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, we applied a new methodology that allowed us to obtain more exact results.

More comprehensive sampling

The samples used in earlier phylogenetic studies were taken from a limited pool of languages. Moreover, some analyses had assumed that modern languages are derived directly from ancient written languages, when they actually come from oral variants that were spoken during the same period – Spanish, for example, did not come from the classical Latin found in Virgil’s works, but from the popular or “vulgar” Latin which was spoken by ordinary people. These shortcomings and assumptions have distorted age estimates for Indo-European language family subgroups such as Germanic, Slavic or Romance.

The new study addresses these issues, eliminating inconsistencies and taking data from a wider range of sources (from 161 languages, to be exact), to provide a more balanced and complete sample set. This data then underwent a Bayesian phylogenetic analysis , a statistical method for establishing the most probable relationships between languages and branches of the family tree.

The study showed, for example, that an Italo-Celtic language family cannot exist, since the Italic and Celtic languages separated several centuries before the separation of the Germanic and Celtic languages, which took place around 5,000 years ago.

An eight thousand year old language family

Regarding the question of the origin of Indo-European languages, calculations based on the new data show that they were first spoken approximately 8,000 years ago.

The results of this research do not line up neatly with either the Anatolian or the Kurgan hypotheses. Instead they suggest that the birthplace of Indo-European languages is somewhere in the south of the Caucasus region. From there, they then expanded in various directions: westward towards Greece and Albania; eastward towards India, and northward towards the Pontic Steppe.

Around three millennia later there was then a second wave of expansion from the Pontic Steppe towards Europe, which gave rise to the majority of the languages that are spoken today in Europe. This hybrid hypothesis, which marries up the two previously established theories, also aligns with the results of the most recent studies in the field of genetic anthropology.

In addition to bringing us closer to solving the centuries-old enigma of the origin of our languages, this research illustrates how disciplines as disparate as genetics and linguistics can complement each other to provide more reliable answers to questions of human prehistory. It is hoped that the same methodology will also serve, in future research, to expand our understanding of how languages and populations spread to other continents.

This article was originally published in Spanish

- The Conversation Europe

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Program Development Officer - Business Processes

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 27 November 2003

Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin

- Russell D. Gray 1 &

- Quentin D. Atkinson 1

Nature volume 426 , pages 435–439 ( 2003 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

491 Citations

107 Altmetric

Metrics details

Languages, like genes, provide vital clues about human history 1 , 2 . The origin of the Indo-European language family is “the most intensively studied, yet still most recalcitrant, problem of historical linguistics” 3 . Numerous genetic studies of Indo-European origins have also produced inconclusive results 4 , 5 , 6 . Here we analyse linguistic data using computational methods derived from evolutionary biology. We test two theories of Indo-European origin: the ‘Kurgan expansion’ and the ‘Anatolian farming’ hypotheses. The Kurgan theory centres on possible archaeological evidence for an expansion into Europe and the Near East by Kurgan horsemen beginning in the sixth millennium BP 7 , 8 . In contrast, the Anatolian theory claims that Indo-European languages expanded with the spread of agriculture from Anatolia around 8,000–9,500 years bp 9 . In striking agreement with the Anatolian hypothesis, our analysis of a matrix of 87 languages with 2,449 lexical items produced an estimated age range for the initial Indo-European divergence of between 7,800 and 9,800 years bp . These results were robust to changes in coding procedures, calibration points, rooting of the trees and priors in the bayesian analysis.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Phylogenomics and the rise of the angiosperms

Network of large pedigrees reveals social practices of Avar communities

Hybrid speciation driven by multilocus introgression of ecological traits

Pagel, M. in Time Depth in Historical Linguistics (eds Renfrew, C., McMahon, A. & Trask, L.) 189–207 (The McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, UK, 2000)

Google Scholar

Gray, R. D. & Jordan, F. M. Language trees support the express-train sequence of Austronesian expansion. Nature 405 , 1052–1055 (2000)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Diamond, J. & Bellwood, P. Farmers and their languages: the first expansions. Science 300 , 597–603 (2003)

Richards, M. et al. Tracing European founder lineage in the Near Eastern mtDNA pool. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 67 , 1251–1276 (2000)

Article CAS Google Scholar

Semoni, O. et al. The genetic legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens in extant Europeans: a Y chromosome perspective. Science 290 , 1155–1159 (2000)

Article ADS Google Scholar

Chikhi, L., Nichols, R. A., Barbujani, G. & Beaumont, M. A. Y genetic data support the Neolithic Demic Diffusion Model. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99 , 11008–11013 (2002)

Gimbutas, M. The beginning of the Bronze Age in Europe and the Indo-Europeans 3500–2500 B.C. J. Indo-Eur. Stud. 1 , 163–214 (1973)

Mallory, J. P. Search of the Indo-Europeans: Languages, Archaeology and Myth (Thames & Hudson, London, 1989)

Renfrew, C. in Time Depth in Historical Linguistics (eds Renfrew, C., McMahon, A. & Trask, L.) 413–439 (The McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, UK, 2000)

Swadesh, M. Lexico-statistic dating of prehistoric ethnic contacts. Proc. Am. Phil. Soc. 96 , 453–463 (1952)

Bergsland, K. & Vogt, H. On the validity of glottochronology. Curr. Anthropol. 3 , 115–153 (1962)

Article Google Scholar

Blust, R. in Time Depth in Historical Linguistics (eds Renfrew, C., McMahon, A. & Trask, L.) 311–332 (The McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, UK, 2000)

Steel, M. A., Hendy, M. D. & Penny, D. Loss of information in genetic distances. Nature 333 , 494–495 (1988)

Swofford, D. L., Olsen, G. J., Waddell, P. J. & Hillis, D. M. in Molecular Systematics (eds Hillis, D., Moritz, C. & Mable, B. K.) 407–514 (Sinauer Associates, Inc, Sunderland, Massachusetts, 1996)

Dixon, R. M. W. The Rise and Fall of Language (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, UK, 1997)

Book Google Scholar

Metropolis, N., Rosenbluth, A. W., Rosenbluth, M. N., Teller, A. H. & Teller, E. Equations of state calculations by fast computing machines. J. Chem. Phys. 21 , 1087–1091 (1953)

Huelsenbeck, J. P., Ronquist, F., Nielsen, R. & Bollback, J. P. Bayesian inference of phylogeny and its impact on evolutionary biology. Science 294 , 2310–2314 (2001)

Huson, D. H. SplitsTree: analyzing and visualizing evolutionary data. Bioinformatics 14 , 68–73 (1998)

Sanderson, M. R8s, Analysis of Rates of Evolution,Version 1.50 (Univ. California, Davis, 2002)

Dyen, I., Kruskal, J. B. & Black, P. FILE IE-DATA1 . Available at 〈 http://www.ntu.edu.au/education/langs/ielex/IE-DATA1 〉 (1997).

Sanderson, M. J. & Donoghue, M. J. Patterns of variation in levels of homoplasy. Evolution 43 , 1781–1795 (1989)

Gamkrelidze, T. V. & Ivanov, V. V. Trends in Linguistics 80: Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans (Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin, 1995)

Rexova, K., Frynta, D. & Zrzavy, J. Cladistic analysis of languages: Indo-European classification based on lexicostatistical data. Cladistics 19 , 120–127 (2003)

Ringe, D., Warnow, T. & Taylor, A. IndoEuropean and computational cladistics. Trans. Philol. Soc. 100 , 59–129 (2002)

Gkiasta, M., Russell, T., Shennan, S. & Steele, J. Neolithic transition in Europe: the radiocarbon record revisited. Antiquity 77 , 45–62 (2003)

Cavalli-Sforza, L. L., Menozzi, P. & Piazza, A. The History and Geography of Human Genes (Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, 1994)

MATH Google Scholar

Holden, C. J. Bantu language trees reflect the spread of farming across sub-Saharan Africa: a maximum-parsimony analysis. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269 , 793–799 (2002)

Barbrook, A. C., Howe, C. J., Blake, N. & Robinson, P. The phylogeny of The Canterbury Tales. Nature 394 , 839 (1998)

McMahon, A. & McMahon, R. Finding families: Quantitative methods in language classification. Trans. Philol. Soc. 101 , 7–55 (2003)

Huelsenbeck, J. P. & Ronquist, F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogeny. Bioinformatics 17 , 754–755 (2001)

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Allan, L. Campbell, L. Chikhi, M. Corballis, N. Gavey, S. Greenhill, J. Hamm, J. Huelsenbeck, G. Nichols, A. Rodrigo, F. Ronquist, M. Sanderson and S. Shennan for useful advice and/or comments on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, 1020, Auckland, New Zealand

Russell D. Gray & Quentin D. Atkinson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Russell D. Gray .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary table (doc 35 kb), rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Gray, R., Atkinson, Q. Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin. Nature 426 , 435–439 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02029

Download citation

Received : 18 July 2003

Accepted : 22 August 2003

Issue Date : 27 November 2003

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02029

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Inferring language dispersal patterns with velocity field estimation.

- Menghan Zhang

Nature Communications (2024)

Machine culture

- Levin Brinkmann

- Fabian Baumann

- Iyad Rahwan

Nature Human Behaviour (2023)

Reliability models in cultural phylogenetics

- Rafael Ventura

Biology & Philosophy (2023)

Valence-dependent mutation in lexical evolution

- Joshua Conrad Jackson

- Kristen Lindquist

- Joseph Watts

Nature Human Behaviour (2022)

An evolutionary view of institutional complexity

- Victor Zitian Chen

- John Cantwell

Journal of Evolutionary Economics (2022)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Study at Cambridge

About the university, research at cambridge.

- Undergraduate courses

- Events and open days

- Fees and finance

- Postgraduate courses

- How to apply

- Postgraduate events

- Fees and funding

- International students

- Continuing education

- Executive and professional education

- Courses in education

- How the University and Colleges work

- Term dates and calendars

- Visiting the University

- Annual reports

- Equality and diversity

- A global university

- Public engagement

- Give to Cambridge

- For Cambridge students

- For our researchers

- Business and enterprise

- Colleges & departments

- Email & phone search

- Museums & collections

- Cambridge Language Sciences

- About overview

- Directory overview

- Academic Staff

- Graduate Students

- Associate Members

- Visiting Scholars

- Editing your profile

- Impact overview

- Policy overview

- Languages, Society and Policy

- Language Analysis in Schools: Education and Research (LASER)

- Is it possible to differentiate multilingual children and children with Developmental Language Disorder (DLD)?

- Refugee Access to Early Childhood Education and Care in the UK

- Modern Languages Educational Policy in the UK

- Multilingualism and Wellbeing in UK

- The Educated Brain seminar series

- What is the value of languages in the UK?

- Improving support for pupils with English as an additional language

- Events overview

- Upcoming Events

- Research Strategy Forum

- Past Events

- Funding overview

- Language Sciences Incubator Fund overview

- Incubator Fund projects

- Eligibility & funding criteria

- Feedback from awardees

- Language Sciences Workshop Fund overview

- Workshops funded

- Language Sciences Impact Fund

- Jobs & Studentships

- Graduate Students overview

- Language Sciences Interdisciplinary Programme overview

- Applying for the Programme

- Sharable Options

- Examples of Research Projects

New evidence supports Anatolia hypothesis for origins of English

Submitted by Administrator on Thu, 30/08/2012 - 11:34

A recent study published in Science , and reported by news agencies including the BBC, backs a hypothesis about the origins of the Indo-European languages (including English) first proposed by the distinguished Cambridge archaeologist Professor Colin Renfrew (Lord Renfrew of Kaimsthorn) in 1987.

Professor Renfrew's Anatolian hypothesis suggested that modern Indo-European languages originated in Anatolia in Neolithic times, and linked their arrival in Europe with the spread of farming. The alternative, and for many years, the more accepted view was that Indo-European languages originated around 3,000 years later in the Steppes of Russia (the Kurgan hypothesis ).

Researchers in New Zealand led by Dr. Quentin Atkinson of the University of Auckland have now applied research techniques used to trace virus epidemics to the study of language evolution. Using very different methods to those used by Professor Renfrew in the 1980s, they tested both the Anatolian and the Kurgan hypotheses, and their findings support the former.

Professor Renfrew comments:

"The hypothesis, which I put forward 25 years ago in my book Archaeology and Language , that the original home of the first Indo-European language was in Anatolia, was based on archaeological evidence that early farming (and the increase in population density that came with it) came to Europe from Anatolia. The argument was that the widespread adoption of a new language required a major economic and demographic change, such as the adoption of farming. Supporting evidence has come through since then that the wide regional distribution of several other language families (including Austronesian and Bantu) came about as the result of early farming dispersals.

The new and impressive finding by Quentin Atkinson and his colleagues is based on the phylogeographic analysis of purely linguistic data, and thus comes to much the same conclusion independently, using very different evidence. This gives striking support to the Anatolian hypothesis.

The traditional view that the homeland of the Proto-Indo-Europeans was in the steppe lands north of the Black Sea derives from the old misconception that the early population of that area were mounted warrior nomad pastoralists, who allegedly invaded Europe around the beginning of the Bronze Age. Few archaeologist now believe that. But this old myth dies hard. In reality, the development of mounted cavalry did not much pre-date the Scythians of the first millennium BC.

Much emphasis is traditionally placed by some Indo-Europeanists on just a few vocabulary terms, such as those for ‘horse’, ‘wheel’, chariot’, ‘cart’ etc. on the very reasonable grounds that these features make their appearance relatively late in the archaeological record. Since there are words for these things in the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European language, that language cannot (they argue) have dispersed before the invention, for instance, of the wheel. But these linguists sometimes use this method of linguistic palaeontology in a rather cumbersome way. They sometimes fail to acknowledge that with the invention of a new concept (e.g. the wheel), the new noun that was invented for it in the by-then different early Indo-European languages was often derived from existing concepts (e.g. ‘to rotate’ for the Latin rota , and similarly for the reconstructed Indo-European * kweklos , related to the Greek kyklos , ‘circle’). Circles and rotation have been known to humans for tens of thousands of years and cannot be used to date Proto-Indo-European!"

Follow the links for more on this item.

http://www.sciencemag.org/content/337/6097/957.abstract?sid=192102e8-a5bc-4744-ac5a-5500338ab381

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-19368988

Cambridge Language Sciences is an Interdisciplinary Research Centre at the University of Cambridge. Our virtual network connects researchers from five schools across the university as well as other world-leading research institutions. Our aim is to strengthen research collaborations and knowledge transfer across disciplines in order to address large-scale multi-disciplinary research challenges relating to language research.

JOIN OUR NETWORK

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

- 01 Jul UK and Ireland Speech Workshop 2024

- 12 Jul 10th Cambridge Conference on Language Endangerment

- 21 Nov Language Sciences Annual Symposium 2024: How can learning a second language be made effortless?

View all events

© 2024 University of Cambridge

- Contact the University

- Accessibility

- Freedom of information

- Privacy policy and cookies

- Statement on Modern Slavery

- Terms and conditions

- University A-Z

- Undergraduate

- Postgraduate

- Research news

- About research at Cambridge

- Spotlight on...

Anatolian hypothesis

The Anatolian hypothesis , also known as the Anatolian theory or the sedentary farmer theory , first developed by British archaeologist Colin Renfrew in 1987, proposes that the dispersal of Proto-Indo-Europeans originated in Neolithic Anatolia . It is the main competitor to the Kurgan hypothesis , or steppe theory, which enjoys more academic favor.

Quotes [ edit ]

- Heaven, Heroes and Happiness: The Indo-European Roots of Western Ideology by Shan M.M. Winn, University Press of America, Lanham-New York-London, 1995. Quoted in Talageri, S. (2000). The Rigveda: A historical analysis. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan.

- Elst, Koenraad (2018). Still no trace of an Aryan invasion: A collection on Indo-European origins .

External links [ edit ]

- History of Asia

Navigation menu

- You are here

- Everything Explained.Today

- A-Z Contents

- Kurgan hypothesis

Predecessors

Arguments for the identification of the Proto-Indo-Europeans as steppe nomads from the Pontic–Caspian region had already been made in the 19th century by the German scholars, Theodor Benfey (1869) and (1870), followed notably by Otto Schrader (1883, 1890). [7] Theodor Poesche had proposed the nearby Pinsk Marshes . In his standard work [8] about PIE and to a greater extent in a later abbreviated version, [9] Karl Brugmann took the view that the urheimat could not be identified exactly by the scholarship of his time, but he tended toward Schrader's view. However, after Karl Penka 's 1883 [10] rejection of non-European PIE origins, most scholars favoured a Northern European origin .

The view of a Pontic origin was still strongly supported, including by the archaeologists V. Gordon Childe [11] and Ernst Wahle . [12] One of Wahle's students was Jonas Puzinas , who became one of Marija Gimbutas's teachers. Gimbutas, who acknowledged Schrader as a precursor, [13] painstakingly marshalled a wealth of archaeological evidence from the territory of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc that was not readily available to Western scholars, revealing a fuller picture of prehistoric Europe.

When it was first proposed in 1956, in The Prehistory of Eastern Europe, Part 1 , Gimbutas's contribution to the search for Indo-European origins was an interdisciplinary synthesis of archaeology and linguistics. The Kurgan model of Indo-European origins identifies the Pontic–Caspian steppe as the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) urheimat , and a variety of late PIE dialects are assumed to have been spoken across this region. According to this model, the Kurgan culture gradually expanded to the entire Pontic–Caspian steppe, Kurgan IV being identified with the Yamnaya culture of around 3000 BC.

The mobility of the Kurgan culture facilitated its expansion over the entire region and is attributed to the domestication of the horse followed by the use of early chariots . The first strong archaeological evidence for the domestication of the horse comes from the Sredny Stog culture north of the Azov Sea in Ukraine , and would correspond to an early PIE or pre-PIE nucleus of the 5th millennium BC. Subsequent expansion beyond the steppes led to hybrid, or in Gimbutas's terms "kurganized" cultures, such as the Globular Amphora culture to the west. From these kurganized cultures came the immigration of Proto-Greeks to the Balkans and the nomadic Indo-Iranian cultures to the east around 2500 BC.

Kurgan culture

Cultural horizon.

Gimbutas defined and introduced the term " Kurgan culture " in 1956 with the intention of introducing a "broader term" that would combine Sredny Stog II , Pit Grave (Yamnaya), and Corded ware horizons (spanning the 4th to 3rd millennia in much of Eastern and Northern Europe). The Kurgan archaeological culture or cultural horizon comprises the various cultures of the Pontic–Caspian steppe in the Copper Age to Early Bronze Age (5th to 3rd millennia BC), identified by similar artifacts and structures, but subject to inevitable imprecision and uncertainty. The eponymous kurgan s (mound graves) are only one among several common features.

Cultures that Gimbutas considered as part of the "Kurgan culture":

- Bug–Dniester (6th millennium)

- Samara (5th millennium)

- Khvalynsk (5th millennium)

- Dnieper–Donets (5th to 4th millennia)

- Sredny Stog (mid-5th to mid-4th millennia)

- Maikop – Deriivka (mid-4th to mid-3rd millennia)

- Yamnaya (Pit Grave)

This is itself a varied cultural horizon, spanning the entire Pontic–Caspian steppe from the mid-4th to the 3rd millennium.

- Usatovo culture (late 4th millennium)

Stages of culture and expansion

Gimbutas's original suggestion identifies four successive stages of the Kurgan culture:

- Kurgan I , Dnieper / Volga region, earlier half of the 4th millennium BC. Apparently evolving from cultures of the Volga basin, subgroups include the Samara and Seroglazovo cultures.

- Kurgan II–III , latter half of the 4th millennium BC. Stone circle s, anthropomorphic stone stelae of deities. Includes the Sredny Stog culture and the Maykop culture of the northern Caucasus .

- Kurgan IV or Pit Grave (Yamnaya) culture, first half of the 3rd millennium BC, encompassing the entire steppe region from the Ural to Romania .

In other publications she proposes three successive "waves" of expansion:

- Wave 1 , predating Kurgan I, expansion from the lower Volga to the Dnieper, leading to coexistence of Kurgan I and the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture . Repercussions of the migrations extend as far as the Balkans and along the Danube to the Vinča culture in Serbia and Lengyel culture in Hungary .

- Wave 2 , mid 4th millennium BC, originating in the Maykop culture and resulting in advances of "kurganized" hybrid cultures into northern Europe around 3000 BC ( Globular Amphora culture , Baden culture , and ultimately Corded Ware culture ). According to Gimbutas this corresponds to the first intrusion of Indo-European languages into western and northern Europe.

- Wave 3 , 3000–2800 BC, expansion of the Pit Grave culture beyond the steppes, with the appearance of the characteristic pit graves as far as modern Romania, Bulgaria, eastern Hungary and Georgia, coincident with the end of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture and Trialeti culture in Georgia .

- 4500–4000: Early PIE . Sredny Stog, Dnieper–Donets and Samara cultures, domestication of the horse ( Wave 1 ).

- 4000–3500: The Pit Grave culture (a.k.a. Yamnaya culture), the prototypical kurgan builders, emerges in the steppe, and the Maykop culture in the northern Caucasus . Indo-Hittite models postulate the separation of Proto-Anatolian before this time.

- 3500–3000: Middle PIE . The Pit Grave culture is at its peak, representing the classical reconstructed Proto-Indo-European society with stone idols , predominantly practicing animal husbandry in permanent settlements protected by hillfort s, subsisting on agriculture, and fishing along rivers. Contact of the Pit Grave culture with late Neolithic Europe cultures results in the "kurganized" Globular Amphora and Baden cultures ( Wave 2 ). The Maykop culture shows the earliest evidence of the beginning Bronze Age , and Bronze weapons and artifacts are introduced to Pit Grave territory. Probable early Satemization .

- 3000–2500: Late PIE . The Pit Grave culture extends over the entire Pontic steppe ( Wave 3 ). The Corded Ware culture extends from the Rhine to the Volga , corresponding to the latest phase of Indo-European unity, the vast "kurganized" area disintegrating into various independent languages and cultures, still in loose contact enabling the spread of technology and early loans between the groups, except for the Anatolian and Tocharian branches, which are already isolated from these processes. The centum–satem break is probably complete, but the phonetic trends of Satemization remain active.

Further expansion during the Bronze Age

See main article: Indo-European migrations . The Kurgan hypothesis describes the initial spread of Proto-Indo-European during the 5th and 4th millennia BC. [14] As used by Gimbutas, the term "kurganized" implied that the culture could have been spread by no more than small bands who imposed themselves on local people as an elite. This idea of PIE and its daughter languages diffusing east and west without mass movement proved popular with archaeologists in the 1970s (the pots-not-people paradigm). [15] The question of further Indo-Europeanization of Central and Western Europe, Central Asia and Northern India during the Bronze Age is beyond the scope of the Kurgan hypothesis, and far more uncertain than the events of the Copper Age, and subject to some controversy. The rapidly developing fields of archaeogenetics and genetic genealogy since the late 1990s have not only confirmed a migratory pattern out of the Pontic Steppe at the relevant time [3] [4] [16] but also suggest the possibility that the population movement involved was more substantial than earlier anticipated and invasive. [16] [17]

Invasion versus diffusion scenarios (1980s onward)

Gimbutas believed that the expansions of the Kurgan culture were a series of essentially-hostile military incursions in which a new warrior culture imposed itself on the peaceful, matrilinear , and matrifocal (but not matriarchal ) cultures of " Old Europe " and replaced it with a patriarchal warrior society, a process visible in the appearance of fortified settlements and hillforts and the graves of warrior-chieftains:

In her later life, Gimbutas increasingly emphasized the authoritarian nature of this transition from the egalitarian society centered on the nature/earth mother goddess ( Gaia ) to a patriarchy worshipping the father/sun/weather god (Zeus, Dyaus ). [18]

J. P. Mallory (in 1989) accepted the Kurgan hypothesis as the de facto standard theory of Indo-European origins, but he distinguished it from an implied "radical" scenario of military invasion. Gimbutas's actual main scenario involved slow accumulation of influence through coercion or extortion, as distinguished from general raiding shortly followed by conquest:

Alignment with Anatolian hypothesis (2000s)

See main article: Anatolian hypothesis .

In the 2000s, Alberto Piazza and Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza tried to align the Anatolian hypothesis with the steppe theory. According to Piazza, "[i]t is clear that, genetically speaking, peoples of the Kurgan steppe descended at least in part from people of the Middle Eastern Neolithic who immigrated there from Anatolia ." According to Piazza and Cavalli-Sforza (2006), the Yamna-culture may have been derived from Middle Eastern Neolithic farmers who migrated to the Pontic steppe and developed pastoral nomadism. Wells agrees with Cavalli-Sforza that there is " some genetic evidence for migration from the Middle East." Nevertheless, the Anatolian hypothesis is incompatible with the linguistic evidence.

Anthony's revised steppe theory (2007)

David Anthony 's The Horse, the Wheel and Language describes his "revised steppe theory". He considers the term "Kurgan culture" so imprecise as to be useless, and instead uses the core Yamnaya culture and its relationship with other cultures as points of reference. [19] He points out:

He does not include the Maykop culture among those that he considers to be Indo-European-speaking and presumes instead that they spoke a Caucasian language .

- Hamangia culture

- Varna culture

- Animal sacrifice

- Revised Kurgan theory

- Germanic substrate hypothesis

- Archaeogenetics of Europe

- Haplogroup R1a

- Lactase persistence

Competing hypotheses

- Armenian hypothesis

- Anatolian hypothesis

- Out of India theory

- Paleolithic continuity theory

Bibliography

- . Anthony . David W. . Bogucki . Peter . Comşa . Eugen . Gimbutas . Marija . Jovanović . Borislav . Mallory . J. P. . Milisaukas . Sarunas . The "Kurgan Culture," Indo-European Origins, and the Domestication of the Horse: A Reconsideration . Current Anthropology . 1986 . 27 . 4 . 291–313 . 10.1086/203441 . 2743045 . 143388176 . 0011-3204.

- Book: Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca . Genes, peoples, and languages . Farrar Straus & Giroux . 2000 . 978-0-86547-529-8 .

- Book: Piazza . Alberto . Cavalli-Sforza . Luigi . Diffusion of genes and languages in human evolution . Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on the Evolution of Language . 2006 . 255–266 . http://www.isrl.uiuc.edu/~amag/langev/paper/piazza06evolang.html.

- Book: Strazny. Philipp. 2000. Dictionary of Historical and Comparative Linguistics. Routledge. 1st. 978-1-57958-218-0.

External links

- Humanjourney.us, The Indo-Europeans

Notes and References

- Book: Renfrew, Colin. Archaeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins. 1990. CUP Archive. 978-0-521-38675-3. 37–38.

- Jones-Bley. Karlene. 2008. Proceedings of the Eighteenth Annual Indo-European Conference, Los Angeles, November 3–4, 2006. Historiographia Linguistica. en. 35. 3. 465–467. 10.1075/hl.35.3.15koe. 0302-5160.

- Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia . Allentoft . etal . 2015 . Nature . 522 . 7555 . 167–172 . 10.1038/nature14507. 26062507 . 2015Natur.522..167A . 4399103 .

- Mathieson . Iain . Lazaridis . Iosif . Rohland . Nadin . Mallick . Swapan . Patterson . Nick . Roodenberg . Songül Alpaslan . Harney . Eadaoin . Stewardson . Kristin . Fernandes . Daniel . Novak . Mario . Sirak . Kendra . 2015. Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians . Nature . en . 528 . 7583 . 499–503 . 10.1038/nature16152 . 1476-4687 . 4918750 . 26595274. 2015Natur.528..499M .

- Narasimhan . Vagheesh M. . Patterson . Nick . Moorjani . Priya . Rohland . Nadin . Bernardos . Rebecca . Mallick . Swapan . Lazaridis . Iosif . Nakatsuka . Nathan . Olalde . Iñigo . Lipson . Mark . Kim . Alexander M. . 2019. The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia . Science . en . 365 . 6457 . eaat7487 . 10.1126/science.aat7487 . 0036-8075 . 6822619 . 31488661.

- Shinde . Vasant . Narasimhan . Vagheesh M. . Rohland . Nadin . Mallick . Swapan . Mah . Matthew . Lipson . Mark . Nakatsuka . Nathan . Adamski . Nicole . Broomandkhoshbacht . Nasreen . Ferry . Matthew . Lawson . Ann Marie . 2019-10-17 . An Ancient Harappan Genome Lacks Ancestry from Steppe Pastoralists or Iranian Farmers . Cell . English . 179 . 3 . 729–735.e10 . 10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.048 . 0092-8674 . 6800651 . 31495572.

- Book: Grünthal. Riho. A Linguistic Map of Prehistoric Northern Europe. Kallio. Petri. 2012 . Société Finno-Ougrienne. 978-952-5667-42-4. 122.

- Karl Brugmann, Grundriss der vergleichenden Grammatik der indogermanischen Sprachen , vol. 1.1, Strassburg 1886, p. 2.

- Karl Brugmann, Kurze vergleichende Grammatik der indogermanischen Sprachen , vol. 1, Strassburg 1902, pp. 22–23.

- Karl Penka, Origines Ariacae: Linguistisch-ethnologische Untersuchungen zur ältesten Geschichte der arischen Völker und Sprachen (Vienna: Taschen, 1883), 68.

- Vere Gordon Childe, The Aryans: A Study of Indo-European Origins (London: Kegan Paul, 1926).

- Ernst Wahle (1932). Deutsche Vorzeit , Leipzig 1932.

- Book: Gimbutas. Marija. The Balts . 1963. Thames & Hudson. London. 38 . https://web.archive.org/web/20131030062207/http://www.vaidilute.com/books/gimbutas/gimbutas-02.html . 2013-10-30.

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th edition, 22:587–588

- Web site: . Facing the ocean . Discover Magazine Blog – Gene Expression . 28 April 2012 . dead . https://web.archive.org/web/20130609041146/http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/gnxp/2012/04/facing-the-ocean/ . 2013-06-09.

- Reich . David . The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years . Science . 15 March 2019. 363 . 6432 . 1230–1234 . 10.1126/science.aav4040 . 30872528 . 6436108 . 2019Sci...363.1230O . free .

- Preston . Douglas . The Skeletons at the Lake . 13 February 2021 . Annals of Science . The New Yorker . December 7, 2020.

- Gimbutas . Marija . 1993-08-01 . The Indo-Europeanization of Europe: the intrusion of steppe pastoralists from south Russia and the transformation of Old Europe . WORD . 44 . 2 . 205–222 . 10.1080/00437956.1993.11435900 . 0043-7956. free . Free PDF download .

- , "Why not a Kurgan Culture?"

This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License . It uses material from the Wikipedia article " Kurgan hypothesis ".

Except where otherwise indicated, Everything.Explained.Today is © Copyright 2009-2024, A B Cryer, All Rights Reserved. Cookie policy .

my.bionity.com

With an accout for my.bionity.com you can always see everything at a glance – and you can configure your own website and individual newsletter.

- My watch list

- My saved searches

- My saved topics

- My newsletter

To use all functions of this page, please activate cookies in your browser.

Encyclopedia

- Kurgan_hypothesis

The Kurgan model of Indo-European origins draws on both archaeology and linguistics to identify specific archaeological cultures with different stages of the Indo-European expansion.

The Kurgan's thesis is the predominant model of Indo-European origins. [1] [2]

Additional recommended knowledge

Daily Visual Balance Check

Guide to balance cleaning: 8 simple steps

How to ensure accurate weighing results every day?

The Kurgan hypothesis originated as a mutual compromise between linguistics and archaeology. The archaeological interpretation of evidence as presented first by Marija Gimbutas, is still considered by historical linguists to give an acceptable approximation to the date at which any set of related Indo-European languages must have started to diverge.