HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY article

The future of coaching: a conceptual framework for the coaching sector from personal craft to scientific process and the implications for practice and research.

- 1 CoachHub GmbH, Berlin, Germany

- 2 Henley Business School, University of Reading, Reading, United Kingdom

This conceptual paper explores the development of coaching, as an expression of applied positive psychology. It argues that coaching is a positive psychology dialogue which has probably existed since the emergence of sophisticated forms of language, but only in the past few 1000years, has evidence emerged of its use as a deliberate practice to enhance learning. In the past 50years, this dialectic tool has been professionalised, through the emergence of professional bodies, and the introduction of formal training and certification. In considering the development of the coaching industry, we have used Rostow’s model of sector development to reflect on future possible pathways and the changes in the coaching industry with the clothing sector, to understand possible futures. We have offered a five-stage model to conceptualise this pathway of development. Using this insight, we have further reviewed past research and predicted future pathways for coaching research, based on a new ten-phase model of coaching research.

Introduction

Coaching is often considered an applied aspect of positive psychology. Both emerged from humanistic psychology, with its focus on the flourishing of the individual, and how individuals, teams and society can create the right conditions for this to be achieved. In this paper, we explore the nature of coaching, as an applied aspect of positive psychology, the journey so far and where practice and research may be heading over the coming 30years.

It would seem only prudent at the start of this paper that we note the challenges of predicting the future direction of any industry and of research in general. We acknowledge the future is ‘trumpet-shaped’, emerging from the point of singularity (now) to multiple possible futures. Any attempt to accurately ‘predict’ the future is challenged by inevitable unforeseen events, their timing and the interaction between foreseen and unforeseen events. We have tried to improve our predictions by drawing on a previously published framework, which we have adapted. However, we ask the reader to note this is just one possible future.

What Is Coaching?

The clear link between coaching as lived positive psychology has been focused on by many writers ( Lomas et al., 2014 ). However, just how much of a driving force positive psychology was in the maturation of coaching is yet to be discussed. In order to establish the role positive psychology played in the maturation of the coaching sector, this section will review their shared historical roots and focus on the influence positive psychology research had on the evolution of coaching definitions.

Coaching and positive psychology’s histories are dynamic and rooted across multiple disciplines, yet they are both born out of the Human Potential Movement of the 1960s. This led to the popularisation of personal and professional growth and development, through pioneers such as Werber Erhard. Brock’s (2010) review of the development of coaching notes the humanistic tradition and the work of Carl Rogers’ of particular significance. Rogers’ focus on the relation and the needs of the clients’ and the potential to find their own way forward have become central features of coaching. Coaching rise coincided with a shift in the perspective about illness and wellbeing. This was the move from the medical model that focused on pathologies to the wellbeing model, which encouraged greater attention towards what individual’s strengths.

Interestingly, coaching psychology (CP) launched in the same year as positive psychology. Atad and Grant (2021) described how coaching psychology was a ‘grassroots’ movement, led by founders of the Coaching Psychology Unit at the University of Sydney and the Special Interest Group in Coaching Psychology in the British Psychological Society (BPS) including psychologists like Stephen Palmer, Jonathan Passmore and Alison Whybrow.

While positive psychology and coaching psychology both focus on the cultivation of optimal functioning and wellbeing ( Green and Palmer, 2019 ), often through the use of personal strengths development, Atad and Grant (2021) reported key differences. The first is that approaches like solutions-focused cognitive-behavioural coaching also aim to help clients define and attain practical solutions to problems. A second difference is the characteristics of the interventions used in each discipline. In coaching psychology interventions, the coach-coachee relationship is central to the coachees development of self-regulated change, whereas Positive Psychology Interventions (PPI’s) typically apply a self-help format.

Since its foundation, positive psychology (PP), the ‘ scientific study of positive human functioning and flourishing intra-personally (e.g. , biologically, emotionally, cognitively ) , inter-personally (e.g. , relationally ) , and collectively (e.g. , institutionally, culturally, and globally )’ ( Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000 ; Oades et al., 2017 ), has grown into a field of applied science ( Atad and Grant, 2021 ).

The field covers an array of topics, most commonly focused on life satisfaction, happiness, motivation, achievement, optimism and organisational citizenship and fairness ( Rusk and Water, 2013 ). Gable and Haidt (2005 , p. 103) defined positive psychology as ‘ The study of the conditions and processes that contribute to the flourishing ( wellbeing ) or optimal functioning of people, groups, and institutions ’. A vast number of PPI’s have been developed and validated ( Donaldson et al., 2014 ), with the aim to enhance subjective or psychological wellbeing or to cultivate positive feelings, behaviours, or cognitions ( Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009 ).

Strength development is viewed as a key process in positive psychology due to the shift from a deficit-based approach towards human functioning: a move from ‘what’s wrong and how can we fix it’, to ‘what’s right and how can we strengthen it’. McQuaid (2017 , p. 285–284) simply describes strengths as, ‘ the things you are good at and enjoy doing ’, which is reflective of Linley and Harrington’s (2006) definition of strengths as ‘ a natural capacity for behaving, thinking, or feeling in a way that allows optimal functioning and performance in the pursuit of valued outcomes ’. Strength-based interventions that aim to promote the awareness, cultivation and application of personal strengths have been reported to have many positive individual and organisational outcomes ( McQuaid, 2017 ). Strengths research is one of the most integrated concepts from positive psychology into coaching psychology.

Interestingly, coaching psychology (CP) also launched in the same year as positive psychology. Atad and Grant (2021) described how coaching psychology was a ‘grassroots’ movement, led by founders of the Coaching Psychology Unit at the University of Sydney and the Special Interest Group in Coaching Psychology in the BPS in the United Kingdom. CP also experienced its own rapid growth in research and practice ( Green and Palmer, 2019 ), which is discussed below.

At the heart of coaching, noted by multiple coaching writers, was its facilitative nature ( Passmore and Lai, 2019 ). Coaching pioneer John Whitmore’s working with Graham Alexander and Alan Fine in the later 1970s and 1980s, and informed by the work of Tim Gallwey (1986) , focused on the self-awareness and personal responsibility which coaching created. This led to Whitmore (1992) defining coaching as having the potential to maximise a person’s performance by adopting a facilitation approach to learning rather than teaching.

This has direct parallels with Deci and Ryan’s (1985) work on self-determination theory (SDT). SDT identifies the conditions that elicit and sustain motivation, focusing on self-regulated intrinsic motivation. These include the needs for competence, autonomy and relatedness ( Deci and Ryan, 1985 ). While Whitmore never formally engaged with SDT Whitmore’s definition of coaching can be seen as a direct application of Deci and Ryan’s (1985) SDT theory and therefore an early indicator of coaching as an applied aspect of positive psychology.

In Brock’s (2010) reflection on the common themes, the facilitative nature of coaching is the strongest similarity across definitions. Brock (2010) also emphasised the interpersonal interactive process that places the coaching relationship at the centre of the facilitation and essential for positive behavioural change. This perspective was maintained in later definitions, which introduced the purpose of coaching to drive positive behavioural changes ( Passmore and Lai, 2019 ) For example, Lai (2014) reported that this was driven by the reflective process between coaches and coachees and continuous dialogue and negotiations that aimed to help coachees’ achieve personal or professional goals.

In summary, in spite of the complementary nature of PP and CP, the fields remain sisters as opposed to fully integrated areas of practice, with coaching psychology drawing from the well of positive psychology, alongside wells of neuroscience and industrial and organisational psychology.

A Conceptual Model for Coaching Development

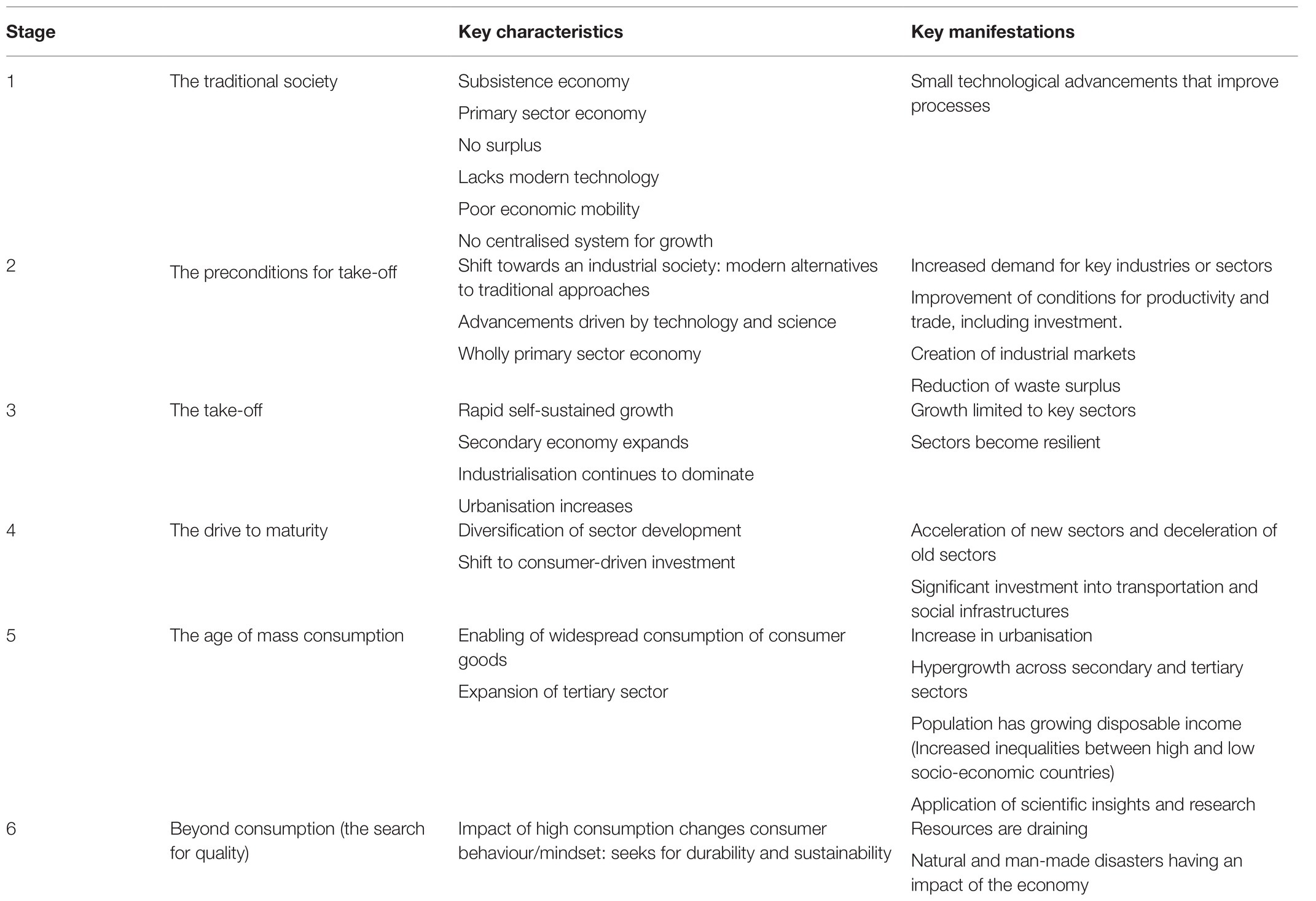

To date, little has been written about the development of the coaching sector, as a specific industry. This may reflect in part the relative immaturity of the industry, but a wider review of industrial literature reveals the categorisation of sector development is limited. One of the few conceptual models is Rostow’s (1959) generalised model of the six stages of economic growth. This offered a linear model of development, which reviews traditional society; the preconditions for take-off; the take-off; the drive to maturity; the age of high mass consumption; and beyond consumption (the search for quality). The model is summarised in Table 1 .

Table 1 . Rostow’s stages of economic growth.

Rostow argued that these stages captured the dynamic nature of economic growth, reflecting the nature of consumption, saving, investment and the social trends that impact it. Rostow’s framework offered insight into the triggers for change at each stage. However, as a generalised model, it is unlikely that all industries or sectors follow the same pathway. Some may never take-off, and others remain as mass consumption. It is also important to note that Rostow’s model is based on observations from a predominantly Western economic perspective situated within a capitalist economic model of growth.

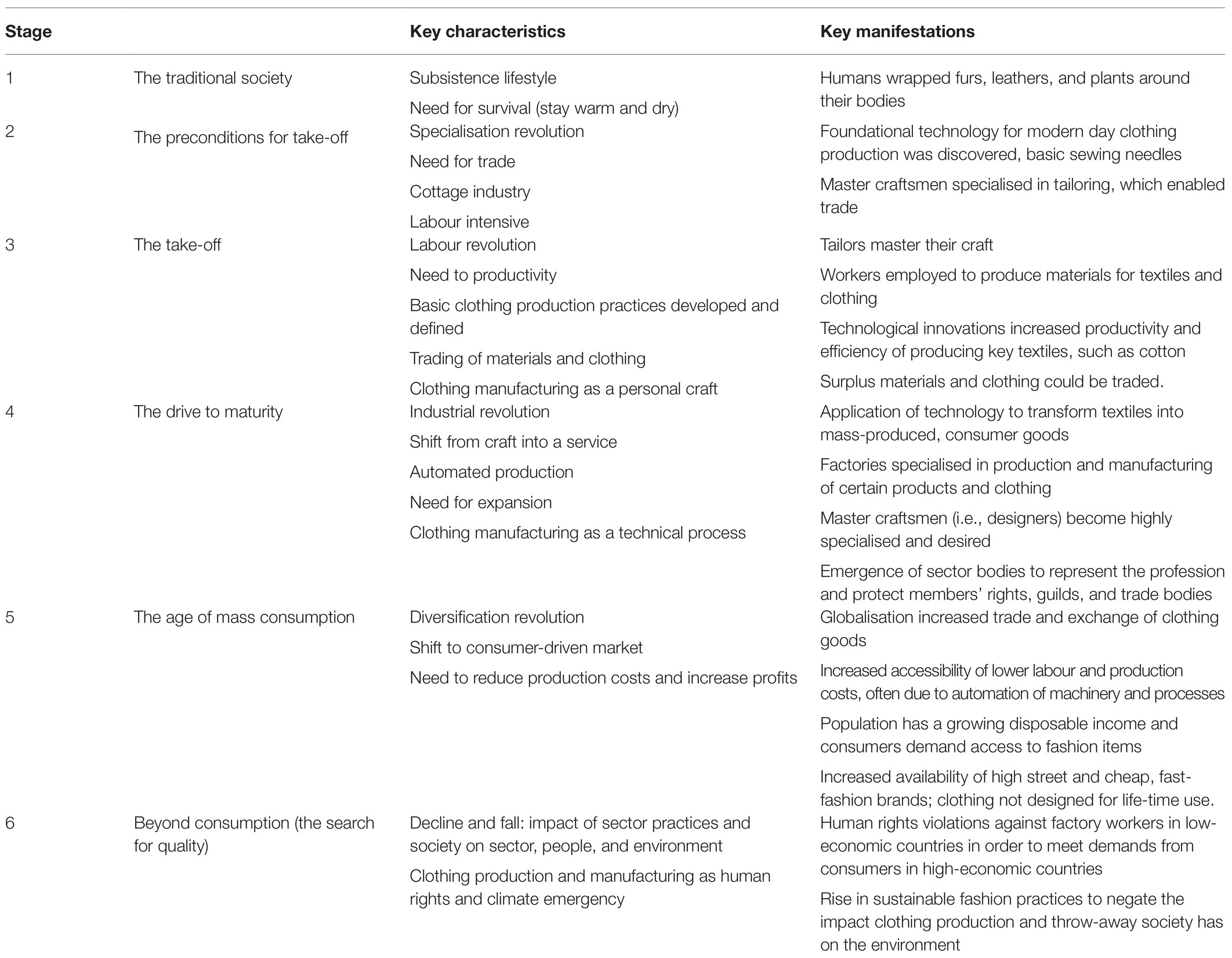

We believe this model provides a heuristic guide, a map, for those observing the development of coaching, and offers an opportunity to predict, based on trends in other industries, how coaching may develop over the coming few decades. In undertaking an analysis of the model, it may be helpful to explore it through a specific sector. The example we selected was clothing manufacture, as being a process which like language, dates back to the prehistory, but which has also changed and developed over the centuries.

The Clothing Sector

The clothing sector has undergone a transformation over the past 10,000years. We might start by considering ‘the sector’ at the time of the Neolithic Revolution, as humans transitioned from hunter gathers to farmers. In hunter-gatherer societies, clothing was primarily a form of protection: protection from cold, plants, animals and battles with fellow tribes. Although given evidence from modern day hunter-gatherer societies, there are also limited examples of parts of clothing being used for status, for example Native American head-wear ( Grinnell, 2008 ). As humans settled, this too started evolve with the emergence of greater status divisions and the development in manufacturing of items, allowing greater differentiation of objects. In the earliest period, most people will have collected the raw materials, engaging as a group in killing an animal. They will have prepared the materials in small groups, stripping the flesh and processing the hide and finished the item will individuals sewing to weaving items together to form the clothing.

As food surpluses emerged as a result of the shift towards settled farming, specialisms started to also emerge. Clothing production shifted from the collective task for small groups and individuals, to the one or more specialists, such as a tailor. This process of specialisation continued with the emergence of training and the development of trades: where individuals could progress over several years of training form apprentice through journeyman to master craftsman. Alongside, this came trade bodies and guilds in the 12th and 13th centuries, to represent the profession and to protect members rights ( Ogilvie, 2011 ). The industrial revolution brought further change with production moving from cottage industries, small shops or upstairs of building used as part home and part clothing ‘factory’ to formal factory production using mechanisation to increase consistency and reduce costs. This process has continued with continued development of automation and over the past 30 years through the digital revolution, which has witnessed a shift from individual’s controlling machines to machines controlling machines. Table 2 summarises the transformation of the clothing sector and demonstrates how Rostow’s model could be applied.

Table 2 . Model of clothing sector development based on Rostow’s model.

Coaching: The Future of Research and Practice

We argue that coaching can learn from the evolution of these other sectors and from the wider conceptual model proposed by Rostow, to better understand the future direction of the coaching and its implications for practice and research.

We start by suggesting that coaching is likely to have a prehistory past. While some argue that coaching was born in 1974 ( Carter-Scott, 2010 ), we believe it is almost certain hunter gathers will have engaged in the use of listening, questioning and encouraging reflective practice to help fellow members of their tribe to improve their hunting skills or their sewing. There is some evidence from Maori people, in New Zealand, that such questioning styles have been used for centuries to aid learning ( Stewart, 2020 ). However, the spoken word leaves no trace for archaeologists to confirm the development of these practices.

While the clothing sector developed in full sight, leaving traces for archaeologists in graves and wall paintings, coaching remained a hidden communication form, until its emergence in societies where written records documented different forms of learning. At that moment, the Socratic form was born. It is often this moment which until now has been regarded as the birth of the positive psychology practice of coaching. It has taken a further 2,500years for coaching to move from a learning technique used by teachers to a specialisation increasingly concentrated in the hands of the few, which requires training, credentials, supervision and ongoing membership of a professional body. While there is good evidence of individuals using coaching in the 1910s ( Trueblood, 1911 ), 1920’s ( Huston, 1924 ; Griffith, 1926 ) and 1930’s ( Gordy, 1937 ; Bigelow, 1938 ), the journey of professionalisation started during the 1980s and 1990s, with the emergence of formal coach training programmes and the formation of professional bodies, such as the European Mentoring and Coaching Council in 1992 and International Coaching Federation in 1995. The trigger for this change is difficult to exactly identify, but the growth of the human potential movement during the 1960s and 1970s and its focus on self-actualisation, combined with the growing wealth held by organisations and individuals meant a demand for such ‘services’ started to emerge from managers and leaders as part of the wider trends in professional development which started in the 1980’s.

This trend of professionalisation has continued for the last three decade. The number of coaches has grown to exceed some 70,000 individuals who are members of professional bodies and industry, although given data from recent studies which reveal that over 30% of coaches have no affiliations, we estimate over 100,000 people earn some or all of their income from coaching ( Passmore, 2021 ). In terms of scale, the industry is estimated to be worth $2.849 billion U.S. dollars (International Coaching Federation, 2020), but in many respects, it has remained a cottage industry, dominated by sole traders and small collectives, with little consolidation of services by larger providers, with little use of technology and science to drive efficiencies or improve outcomes.

Given model and recent developments in technology and the growth of coaching science over the past 10years is coaching reaching a tipping point? Is coaching about to enter the next phase of sector development? Is coaching about to begin the transition from professional service delivered by a limited number of high-cost specialists to an industrial process capable of being delivering low-cost coaching for the many with higher standards in product (service) consistency?

What makes this change likely? There are three factors in our view propelling coaching towards its next stage in development. Firstly, the growth of online communications platforms, such as Microsoft Teams, Zoom and Google Hangout, are enabling individuals to connect with high-quality audio and video images. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic during 2020–21 has seen the development these platforms now reach almost universal adoption. At the same time, a growing number of employees have switched from ‘always in the office’ modes of working to either working from home or hybrid working, working 2, 3 or 4days a week from home ( Owen, 2021 ). Such models provide lower costs for employers, and evidence suggests many employees favour the flexibility working from home provides.

Secondly, the period 2010–2020 witnessed a growth in the science connected with positive psychology and coaching, proving practitioners with a good understanding of the theory and research. Access to this research has been enhanced by an increasing move to Open Access journals, the emergence of research platforms, such as ResearchGate, sharing published papers and tools such as Sci-Hub, granting access to published science, alongside search tools such as Google Scholar allowing efficient discovery of relevant material by practitioners, as well as academics with access to university library databases. In combination, these online tools are democratising the science of coaching and are stimulating the next phase of development.

The third factor is the growth of investor interest in digital platforms, which have seen significant growth during the 2010–2020 period, enabling start-ups to secure the investment need for the development of products, from online mental health (Headspace) to online learning (Lyra Learning - LinkedIn Learning).

The next phase we predict will be an emergence, growth and ultimately domination of coaching by online large-scale platforms, who offer low-cost and on-demand access to coaching services informed by science, in multiple languages and to a consistently high-quality standard. Echoing the changes in clothing production, with mechanisation using machines like Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, and Arkwright’s spinning machine which revolutionised clothing production.

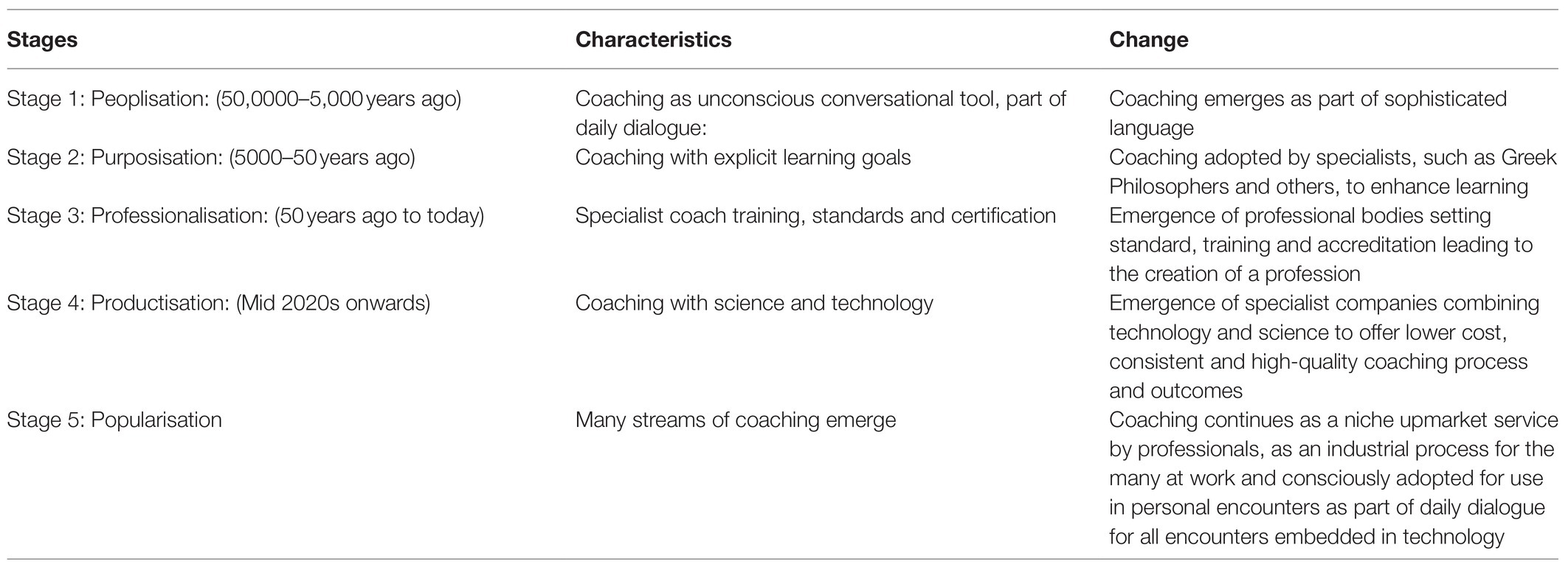

We have developed Rostow’s model and propose a 5P’s model for the coaching industry development. This is summarised in Table 3 . A journey from unconscious practice used by hunter-gatherer societies, through formal use in learning, to specialisation and professionalisation, to the deployment of technology and onwards towards a more conscious use across society of positive psychology approaches, including coaching as a tool to enhance self-awareness and self-responsibility, embedded in technology.

Table 3 . 5P’s model of coaching industry development.

It is worth noting that across sectors the move from one stage to the next created disruption and negative consequences in uncontrolled markets. In agriculture, shifts in production, such as land enclosures, and introduction of mechanisation led to landlessness and starvation, in clothing manufacturing production disruptions lead to low pay and exploitation. These changes also stimulated agricultural revolts and the emergence of Luddites, as workers affected by change pushed back against these change in their daily work patterns, income levels or status.

In coaching, we can see similar push back from some in coaching, who fear the negative impacts of research and technology, as coaching starts to move away from being a cottage industry, where fee rates are unrelated to training, qualifications or other measurable indicators ( Passmore et al., 2017 ) towards providing greater consistency, evidence driven practice. Such push back is likely not only to be from individuals but also guilds (professional bodies) wo see their power being undermined by the rise of large-scale, Google-LinkedIn, providers, who’s income, corporate relationships and global reach will shift the power balance in the industry.

Given this awareness of the risks of change, it is beholden on the new technology firms to be sensitive to the needs of all stakeholders. We advocate a Green Ocean strategy ( Passmore and Mir, 2020 ). Under such a strategy, the focus is on collaboration, seeking sustainable win-win outcomes, which benefit all stakeholders, and take at their heart environmental considerations and ethical management, balancing such needs against the drive for quarterly revenues.

The Implications for Positive Psychology - Coaching Research

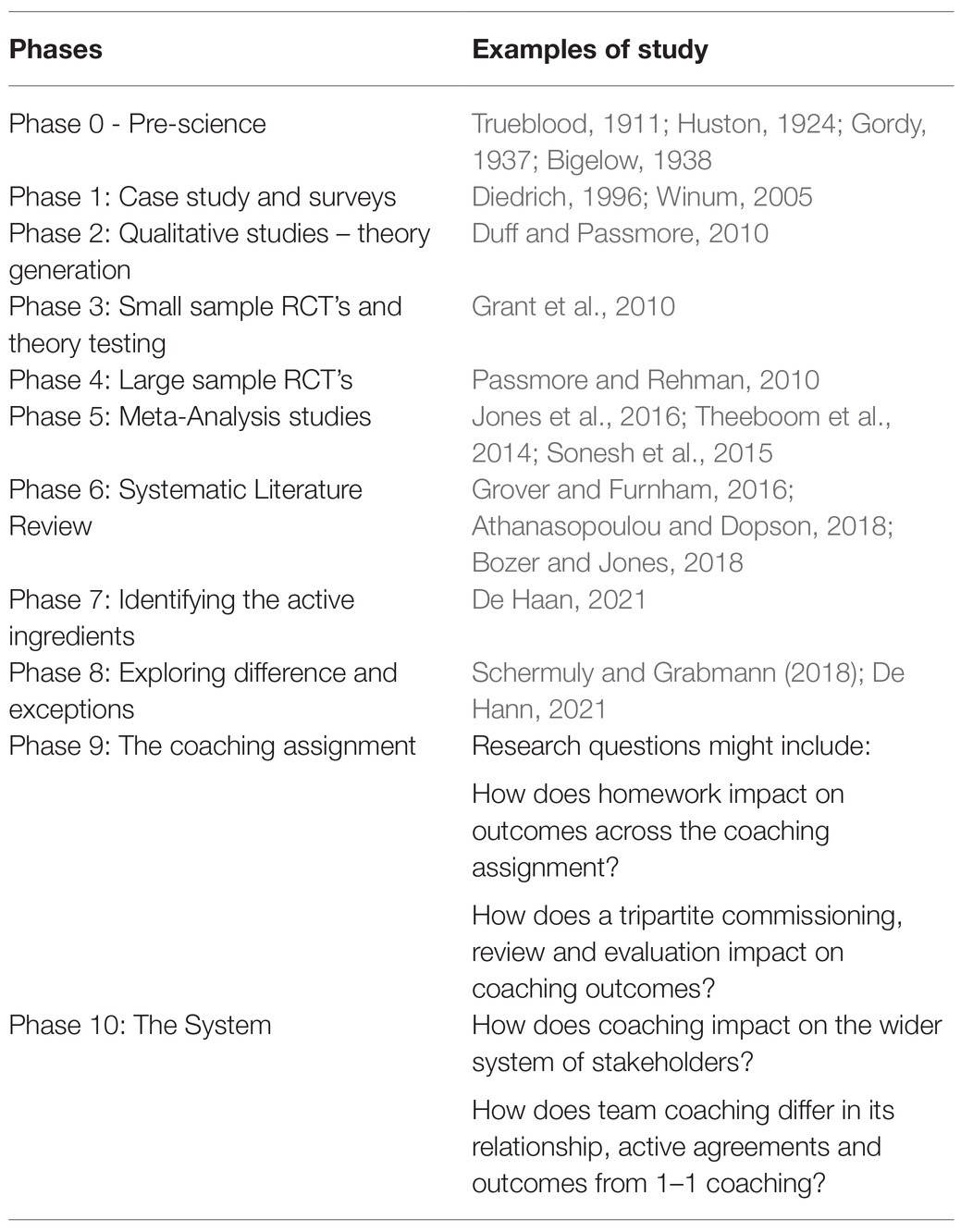

In previous papers, we have proposed a model reviewing the journey of positive psychology coaching research ( Passmore and Fillery-Travis, 2011 ). This offered a series of broad phases, noting the journey of published papers from case studies to more scientific methods, such as randomised control trials, between the 1980s and 2010. The past decade, 2011–21, has witnessed a continued development along the scientific pathway, thanks to the work of researchers such as Anthony Grant, Rebecca Jones, Erik de Haan and Carsten Schermuly.

Specifically, the publication of randomised control trials has grown from a handful of papers in 2011 to several dozen by 2021, while still limited in comparison to areas of practice such as motivational interviewing ( Passmore and Leach, 2021 ), the expanded data set has provided evidence for systematic literature reviews and combination studies, such as meta-analysis. These papers have provided evidence that coaching works, with an effect size broadly similar to other organisational interventions, as well as giving insights at to the most important ingredients of the coaching process.

It is this blossoming of higher quality, quantitative studies, which has led us to believe the science in coaching is maturing. While much work still needs to be done over the coming decade, the insights to date can be used to inform practice at a scale leading to Stage 4 in our 5P coaching sector model.

The coming decade may see opportunities for greater collaboration between coach service providers, as these organisations increase in scale and profitability, and university researchers, keen to access large data sets enabled by the greater use of technology and the global scale of the new coach service providers.

Reflecting these industry changes and the proliferation of research, we have also updated the research journey model, reflecting these developments. We suggested the emergence of new phase of research exploring individual, exceptions and negative effects of coaching ( Passmore, 2016 ; Passmore and Theeboom, 2016 ). This has started to happen with work by Schermuly and Grabmann (2018) and De Hann (2021) . We have linked research papers to the model of coach development in Table 4 and have extended it to create 10 phases.

Table 4 . 10-phase model of coaching research.

The emergence of large coaching providers, operating on digital platforms, with the ability to collect, hold and analyses large volumes of data, the opportunity exists to significantly step up the quantity and quality of research including RCT’s and exploring exceptions and specific presenting issues, ingredients and tools. Of specific interest will be questions including: How does the coach (or client) personality impact on the relationship and outcomes? What roles does similarity in terms of race, gender or sector background have on outcomes? What factors contribute to client trust? How significant is empathy as a factor and in want types of coaching is it most valued? What role do discovery meetings, contracting, external support networks and ‘homework’ play in successful coaching assignments?

Over the next 20years, we can start to unpick these aspects with the help of big data, and unlike some aspects of technological research, let us argue in favour now of sharing knowledge through Open Access, so everyone can gain, and the quality of each and every coaching conversation can be enhanced.

In this paper, we have explored coaching as an expression of positive psychology. We have offered two conceptual frameworks, one for research and one for practice. We hope these frameworks will stimulate further discussion by coaching and positive psychology communities. Our view is that the coaching has become an ‘industry’ and is following a pathway of development similar to many other industries. Recent technological developments, combined with a quickening pace in coaching research, will move coaching from a ‘cottage industry’ towards a fully mechanised process, enhancing accessibility, consistency and reducing cost. This will start with platforms and is likely to lead towards a growing use of automation. This scale provides opportunities for more data, more research and a deeper understanding of the intervention, creating a virtuous circle of development. This too will stimulate the continued development of coaching research pathways considering the assignment and the wider system.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

Authors JP and REK were employed by company CoachHub GmbH.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Atad, O. I., and Grant, A. M. (2021). How does coach training change coaches in training? Differential effects for novice and experienced skilled helpers. Coach. Int. J. Theory Practice. Res. 14, 3–19. doi: 10.1080/17521882.2019.1707246

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Athanasopoulou, A., and Dopson, S. (2018). A systematic review of executive coaching outcomes: is it the journey or the destination that matters the most? Leadersh. Q. 29, 70–88. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.11.004

Bigelow, B. (1938). Building an effective training program for field salesmen. Personnel 14, 142–150.

Google Scholar

Bozer, G., and Jones, R. J. (2018). Understanding the factors that determine workplace coaching effectiveness: a systematic literature review. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 27, 342–361. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2018.1446946

Brock, V. (2010). The secret history of coaching. Available at: http://vikkibrock.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/emcc-2010-secret-of-coaching-history-paper-brock.pdf

Carter-Scott, C. (2010). Transformational Life Coaching. New York: Health Coaching Inc.

De Haan, E. (2021). What Works in Executive Coaching: Understanding Outcomes Through Quantitative Research and Practice-Based Evidence. London & New York: Routledge.

De Hann, E. (2021). The case against coaching. Coach. Psychol. 17, 7–13.

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1985). “Cognitive Evaluation Theory,” in Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination” in Human Behavior. Springer, Boston, MA.

Diedrich, R. C. (1996). An iterative approach to executive coaching. Consult. Psychol. J. 48, 61–66. doi: 10.1037/1061-4087.48.2.61

Donaldson, S. I., Dollwet, M., and Rao, M. A. (2014). Happiness, excellence, and optimal human functioning revisited: examining the peer-reviewed literature linked to positive psychology. J. Posit. Psychol. 10, 185–195. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2014.943801

Duff, M., and Passmore, J. (2010). Ethics in coaching: an ethical decision-making framework for coaching psychologists. Int. Coach. Psychol. Rev. 5, 140–151.

Gable, S. L., and Haidt, J. (2005). What (and why) is positive psychology? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 9, 103–1110. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.103

Gallwey, T. (1986). The Inner Game of Tennis. London: Pan Macmillan.

Gordy, C. (1937). Everyone gets a share of the profits. Fact. Manag. Maintenance 95, 82–83.

Grant, A. M., Green, S., and Rynsaardt, J. (2010). Developmental coaching for high school teachers: executive coaching goes to school. Consult. Psychol. J. 62, 151–168. doi: 10.1037/a0019212

Green, S., and Palmer, S. (2019). Positive Psychology Coaching in Practice. Hove: Routledge.

Griffith, C. R. (1926). Psychology of Coaching: A Study of Coaching Methods From the Point of View of Psychology. New York: Charles Scribner’s and Sons.

Grinnell, G. B. (2008). The Cheyenne Indians: Their History and Lifeways. New York: World Wisdom.

Grover, S., and Furnham, A. (2016). Coaching as a developmental intervention in organisations: a systematic review of its effectiveness and the mechanisms underlying it. PLoS One 11:e0159137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159137

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Huston, R. E. (1924). Debate coaching in high school. Q. J. Speech Educ. 10, 127–143. doi: 10.1080/00335632409379481

Jones, R. J., Woods, S., and Guillaume, Y. (2016). The effectiveness of workplace coaching: a meta-analysis of learning and performance outcomes from coaching. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 89, 249–277. doi: 10.1111/joop.12119

Lai, Y. (2014). Enhancing Evidence-Based Coaching Through the Development of a Coaching Psychology Competency Framework: Focus on the Coaching Relationship. Guildford, U.K.: School of Psychology, University of Surrey

Linley, P. A., and Harrington, S. (2006). Playing to your strengths. Psychologist 19, 86–89.

Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., and Ivtzan, I. (2014). Applied Positive Psychology. London: Sage.

McQuaid, M. (2017). Positive psychology coaching. Organ. Superv. Coach. 24, 283–296. doi: 10.1007/s11613-017-0510-8

Oades, L. G., Steger, M. F., Delle Fave, A., and Passmore, J. (2017). The Psychology of Positivity and Strengths-Based Approaches At Work. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

Ogilvie, S. (2011). Institutions and European Trade: Merchant Guilds 1000–1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Owen, J. (2021). Smart Working: The Ultimate Handbook for Remote and Hybrid Teams. London: Bloomsbury.

Passmore, J. (2016). Coaching Research: The Evidence from Qualitative, Quantitative & Mixed Methods Studies. 17th June, 2016. Association for Coaching. London, UK: Royal Society of Chemistry.

Passmore, J. (2021). The global coaching survey 2021. Henley on thames: henley business school & EMCC. Available at: https://www.henley.ac.uk/business/coaching/research

Passmore, J., Brown, H., and Csigas, Z. (2017). The state of play in European coaching & mentoring. Henley Business School.

Passmore, J., and Fillery-Travis, A. (2011). A critical review of executive coaching research: A decade of progress and what’s to come. Coach. Int. J. Theory Practice Res. 4, 70–88. doi: 10.1080/17521882.2011.596484

Passmore, J., and Lai, Y.-L. (2019). Coaching psychology: exploring definitions and research contribution to practice? International Coaching Psychology Review. 14, 69–83.

Passmore, J., and Leach, S. (2021). Third Wave Cognitive Behavioural Coaching: Contextual, Behavioural and Neuroscience Approaches for Evidence-Based Coaches Luminate.

Passmore, J., and Mir, K. (2020). Green Ocean Thinking . Coaching at Work. September Online .

Passmore, J., and Rehman, H. (2010). Coaching as a learning methodology – a mixed methods study in driver development using a randomised controlled trial and thematic analysis. Int. Coach. Psychol. Rev. 7, 166–184.

Passmore, J., and Theeboom, T. (2016). “Coaching psychology: a journey of development in research,” in Coaching Psychology: Meta-Theoretical Perspectives and Applications in Multi-Cultural Contexts. eds. L. E. Van Zyl, M. W. Stander, and A. Oodendal (New York, NY: Springer), 27–46.

Rusk, R. D., and Water, L. E. (2013). Tracing the size, reach, impact, and breadth of positive psychology. J. Posit. Psychol. 8, 207–221. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2013.777766

Schermuly, C., and Grabmann, C. (2018). A literature review on negative effects of coaching – what we know and what we need to know. Coach. Int. J. Theory Prcatice Res. 12, 39–66. doi: 10.1080/17521882.2018.1528621

Seligman, M. E., and Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: an introduction. Am. Psychol. 55, 5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

Sin, N. L., and Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions a practice-friendly meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 65, 467–487. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20593

Sonesh, S. C., Coultas, C. W., Marlow, S. L., Lacerenza, C. N., Reyes, D., and Salas, E. (2015). Coaching in the wild: identifying factors that lead to success. Consult. Psychol. J. 67, 189–217. doi: 10.1037/cpb0000042

Stewart, C. (2020). Maori Philosophy: Indigenous Thinking for Aotearoa. London: Bloomsbury.

Theeboom, T., Beersma, B., and van Vianen, A. E. (2014). Does coaching work? A meta-analysis on the effects of coaching on individual level outcomes in an organizational context. J. Posit. Psychol. 9, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2013.837499

Trueblood, T. C. (1911). Coaching a debating team. Public Speak. Rev. 1, 84–85.

Whitmore, J. (1992). Coaching for Performance. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Winum, P. C. (2005). Effectiveness of a high-potential African American executive: The anatomy of a coaching engagement. Consult. Psychol. J. 57, 71–89. doi: 10.1037/1065-9293.57.1.71

Keywords: positive psychology, coaching research, coaching practice, democratisation of coaching, coaching trends

Citation: Passmore J and Evans-Krimme R (2021) The Future of Coaching: A Conceptual Framework for the Coaching Sector From Personal Craft to Scientific Process and the Implications for Practice and Research. Front. Psychol . 12:715228. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.715228

Received: 26 May 2021; Accepted: 18 October 2021; Published: 10 November 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Passmore and Evans-Krimme. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jonathan Passmore, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

75 Coaching and Well-being: A Brief Review of Existing Evidence, Relevant Theory, and Implications for Practitioners

Gordon B. Spence, Coaching Psychology Unit, School of Psychology, University of Sydney

Anthony M. Grant, Coaching Psychology Unit, School of Psychology, University of Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Published: 01 August 2013

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Whilst scholarly interest in coaching has increased dramatically in the past decade, the further maturation of the field will continue to depend upon the degree to which knowledge is developed along both theoretical and empirical lines. In this chapter both domains are explored. After providing a brief introduction to coaching, the first section summarizes findings from the empirical coaching literature, which suggest that coaching can positively impact human functioning and well-being across several different contexts. Having reviewed evidence that supports the efficacy of coaching, the second section focuses on an important related question: Why does coaching work? To help answer this question, self-determination theory is introduced and presented as a useful theoretical lens for understanding how a coaching process might yield beneficial effects, for grounding coaching practice in firm foundations and also for generating highly valuable research questions.

This chapter is about coaching and its influence on human functioning and well-being. The chapter is presented in two sections. In the first section coaching is defined and accompanied by a brief description of its essential practices, along with a review of what is currently known empirically about its impact on human functioning and well-being. Having reviewed some evidence that supports the efficacy of coaching, the second section will focus on the important question: Why does coaching work? In proposing an answer to this question we will draw upon self-determination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985 ), a metatheory of human functioning that we believe helps to theoretically ground the practice of coaching. We hope that this discussion will provide both a good general introduction to the field in its current state and stimulate an understanding of why coaching effectively contributes to well-being.

What is Coaching?

Coaching is an action-oriented, collaborative process that seeks to facilitate goal attainment, self-directed learning, and/or enhance performance in the coachee's personal or professional life (Spence & Grant, 2007 ). The articulation of goals is central to the coaching process and these are generally set in a way that stretches an individual's current capacities or performance (Grant & Greene, 2001 ). In essence, the coaching process facilitates goal attainment by helping individuals to: (1) identify desired outcomes, (2) establish specific goals, (3) enhance motivation by identifying strengths and building self-efficacy, (4) identify resources and formulate action plans, (5) monitor and evaluate progress, and (6) modify action plans (where necessary). As shown in Fig. 75.1 , this monitor–evaluate–modify process constitutes a cycle of self-regulated behavior that is key to creating intentional behavior change (Carver & Scheier, 1998 ). The role of the coach is to facilitate the coachee's movement through this self-regulatory cycle, by helping the coachee to develop specific action plans and then to monitor and to evaluate their progression toward those goals.

Generic cycle of self-regulation.

Much of a coach's skill lies in being able to accelerate goal attainment by helping individuals develop and implement solutions to the ongoing challenges faced during goal striving. Regardless of whether coaching occurs as brief, informal “on-the-fly” coaching (lasting, say, 10 minutes) or more lengthy, formal sessions (sometimes lasting up to 2 hours or more), considerable emphasis is placed on the coach to act as the facilitator (rather than the provider) of solutions. Increasingly this has led coaches to adopt the use of solution-focused and strengths-based techniques, which can assist coachees to tap into their personal strengths and resources (Berg & Szabo, 2005 ).

Is coaching effective? What the research says

The first appearance of coaching in the peer-reviewed literature occurs in Gorby's ( 1937 ) report of senior staff coaching junior employees on how to reduce waste, and Bigelow's ( 1938 ) article on how best to implement a sales coaching program. Despite its long history, the coaching literature is still relatively small, although it has grown significantly in recent years.

According to Grant ( 2010 ), in the 62 years between 1937 and 1999 only 93 papers on coaching were published, compared to 542 since 2000. However, of the 616 papers published since 1980, the vast majority have been opinion pieces, descriptive articles or theoretical discussions. Furthermore, of the 179 empirical papers published in this period, many are surveys (e.g., Coutu & Kauffman, 2009 ; Douglas & McCauley, 1999 ), descriptive studies about executive coaching (e.g., Bono, Purvanova, Towler, & Peterson, 2009 ), or research into the characteristics of coach training schools (e.g., Grant & O’Hara, 2006 ). As such, most of the extant empirical coaching literature comprises contextual or survey-based investigations, with little research focused on determining the efficacy of coaching as a methodology for creating purposeful positive change and enhancing well-being. Nevertheless, a brief overview of this literature follows and will be drawn from four areas: workplace/executive coaching; life coaching; health coaching and coaching within educational settings.

Workplace and executive coaching

Although coaching is widely used in the workplace, only two randomized controlled studies of workplace coaching have been reported. In the first, Deviney ( 1994 ) examined the efficacy of supervisors acting as internal workplace coaches and found no changes in supervisors’ feedback skills following a multiple-rater feedback intervention and coaching from their managers over a 9-week period. In the other study, Duijts, Kant, van den Brandt, and Swaen ( 2008 ) examined the effectiveness of coaching as a means of reducing work absence due to psychosocial health complaints. Whilst no decrease in absenteeism was observed, there was significantly lower burnout along with improvements in health, life satisfaction, and psychological well-being. These results suggest that coaching might enhance employee well-being.

There have been some quasi-experimental studies in the workplace using pre-test and post-test comparisons and non-randomized allocation to an intervention or control group. For example, Gyllensten and Palmer ( 2005 ) found that coaching was associated with lower levels of anxiety and workplace stress (compared with a control group), whilst Evers, Brouwers, and Tomic ( 2006 ) reported that executive coaching enhanced participants’ self-efficacy and self-perceived ability to set personal goals. In addition, Barrett ( 2007 ) found that group coaching was effective for reducing burnout but not for improving productivity.

Finally, one study reported on the effectiveness of executive coaching (using a randomized controlled design). In this, participants received 360-degree feedback followed by four sessions of executive coaching. Coaching was found to reduce stress and depression, improve goal attainment, and increase resilience (Grant, Curtayne, & Burton, 2009 ).

Life coaching

Given that commercial life coach training schools first emerged in the early 1990s, it is surprising that comparatively few outcome studies have been conducted on life coaching. In the first published study, Grant ( 2003a ) used a within-subjects (pre–post) design to explore the efficacy of a group-based, solution-focused cognitive behavioral (SF-CB) life coaching program (n = 20). The results indicated that life coaching was associated with enhanced mental health, quality of life, and goal attainment. In a partial replication of this study, Green, Oades, and Grant ( 2006 ) tested the same SF-CB coaching program using a randomized controlled (pre–post) design and found that group life coaching was associated with increases in goal striving, well-being and hope, with some gains maintained at 30 weeks.

Extending this line of research, Spence and Grant ( 2007 ) compared the efficacy of individualized professional one-to-one coaching to peer coaching with an adult community sample (n = 63) over a 10-week period. The results indicated that coachees of professional coaches were more engaged in the coaching process and reported greater goal commitment and goal progression compared to peer coachees and controls. Whilst these participants also reported greater levels of environmental mastery, other facets of well-being did not change.

Finally, life coaching has also been found to be effective with young adults. Using a sample of 56 female high school students (mean age 16 years), Green, Grant, and Rynsaardt ( 2007 ) found that participation in SF-CB life coaching was associated with significant increases in levels of cognitive hardiness and hope, and significant decreases in depression.

Health coaching

The use of coaching in health-related settings is steadily increasing and may prove a useful way of enhancing patient self-management and better utilization of healthcare resources (for a discussion see Kreitzer et al., 2008 ). Health coaching is a patient-centered process that consists of setting health-related goals, identifying obstacles to change, and mobilizing support and resources to enable change (Palmer, Tubbs, & Whybrow, 2003 ). It is typically a multifaceted intervention incorporating cognitive, behavioral and lifestyle change strategies, and includes the teaching of coping skills (Grey et al., 2009 ). A review of this literature reveals that health coaching is being used to address a variety of concerns in an array of settings. For example, Linden, Butterworth, and Prochaska ( 2010 ) provided chronically ill patients with telephone-based health coaching informed by motivational interviewing principles (Miller & Rollnick, 2002 ) and found that it increased their self-efficacy, lifestyle change scores and perceived health status.

In another study, Grey et al. ( 2009 ) explored the difference between general health education and coping skills-based health coaching with inner city youth at risk for type II diabetes. Results indicated that both groups showed some improvement in anthropometric measures, lipids, and depressive symptoms over 12 months, but students who received health coaching showed a greater improvement on indicators of metabolic risk than students who received education only. This confirmed earlier results reported by Spence, Cavanagh, and Grant ( 2008 ) who found that health goal attainment was greater when participants received coaching, compared to a directive, health education-only intervention.

Not all health coaching studies have reported such successes. Gorczynski, Morrow, and Irwin ( 2008 ) reported on the impact of coaching on physical activity participation, self-efficacy, social support, and perceived behavioral control among physically inactive youth. Whilst physical activity significantly increased for one participant, the other participants’ activity levels remained unchanged. No significant changes were found across the other study variables. Similarly, an internet-based health coaching study conducted by Leveille et al. ( 2009 ) reported mixed findings. In investigating the efficacy of coaching aimed at enhancing communication between patients and their primary care physician, results showed that while coached patients received more information from their physicians there was no difference in the detection or management of screened conditions, symptom ratings, and quality of life between the coaching and non-coaching groups.

It appears that whilst life coaching and organizational coaching tend to be effective, health coaching is less so. This is perhaps unsurprising given that such behaviors tend to be anchored by decades of habit. Furthermore, it is difficult to determine whether the health coaching reported in the literature accurately reflects coaching (i.e., a client-centered process aimed at facilitating self-directed learning), or whether it is being utilized as an alternative way to deliver expert information.

Although health coaching for health-related behavior change may not be consistently effective, the use of workplace or executive coaching in health settings to change non-health-related behaviors has been more successful. For example, Taylor ( 1997 ) found that solution-focused coaching enhanced resilience in medical students, whilst Gattellari et al. ( 2005 ) reported that peer coaching by general practitioners improved the coachees’ ability to make informed decisions about prostate-specific antigen screening. Also, Miller, Yahbe, Moyers, Martinez, and Pirritanol ( 2004 ) used a coaching program to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing skills and found that coaching with feedback was superior to training-only. Finally, Yu, Collins, Cavanagh, White, and Fairbrother ( 2008 ) found coaching was associated with significantly greater proactivity, core performance, goal-attainment, self-insight, motivation, positive affect and autonomy for 17 managers in a large teaching hospital.

Coaching in educational settings

Whilst there is now a considerable amount of literature regarding coaching in educational settings much of it is student-focused and directed towards enhancing student learning, or overcoming literacy or learning difficulties (e.g., Merriman & Codding, 2008 ). We will not review this literature here, rather, we will focus on an emerging literature related to teacher-focused coaching (for a review see Denton & Hasbrouck, 2009 ). It should be noted that the term “coaching” in educational settings refers to a very broad range of applications, indicating technical or instructional coaching to increase the instructional skills of teachers (e.g., Brown, Reumann-Moore, Hugh, Du Plessis, & Christman, 2006 ) and reflective practice coaching, which is “a process in which teachers explore the thinking behind their practices” (Garmston, Linder, & Whitaker, 1993 , p. 57).

Whilst little has been reported on the use of coaching to directly increase the well-being or happiness of students or teachers, it has been applied to facilitating professional development and enhancing leadership within educational settings. Much of this work has been conducted using peer coaching with both novice (Jenkins, Garn, & Jenkins, 2005 ; Suleyman, 2006 ) and experienced educators (Johnson, 2009 ). However, as in commercial organizations, some senior management in educational settings also engage in developmental coaching of subordinates (MacKenzie & Marnik, 2008 ). These coaching interventions can be relatively sophisticated with senior school leaders receiving coaching skills training within the context of a structured coaching program, and often incorporate ongoing supervision and impact evaluation (for an example see Simkins, Coldwell, Caillau, Finlayson, & Morgan, 2006 ). Globally, the use of professional coaches and consultants for leadership and professional development within educational settings has been increasing, with some studies yielding encouraging results (Allan, 2007 ; Contreras, 2009 ).

On the basis of the findings presented, coaching appears to be a promising methodology for facilitating goal attainment and enhancing well-being across a variety of domains. Whilst some of this evidence has been generated through the use of robust scientific methods, there is a pressing need for more research in each of the domains outlined; research that seeks to understand (1) the specific impact of coaching across domains, and (2) what processes coaching activates to generate these effects.

How Does Coaching Impact Well-Being?

Using self-determination theory to understand coaching efficacy.

As outlined in the previous section, a growing body of empirical evidence indicates that coaching impacts an array of positive psychological characteristics, including various dimensions of subjective and psychological well-being (e.g., positive affect and environmental mastery). Whilst such findings are encouraging, there are two reasons that this work should be interpreted cautiously. First, the empirical coaching literature is still relatively small with few replications and considerable methodological variability. Second, most of the coaching research conducted to date has lacked firm theoretical foundations and occurred in the absence of clearly articulated, coherent research agendas. As a result, the evidence-base for coaching would best be described as disparate, largely atheoretical, and primarily comprised of “one-off” findings. Clearly, it is not yet a mature field of study.

These observations are not intended as criticisms of the field or those working within it. Rather, they are brief reflections on the current state of coaching research and serve as a reminder that maturation takes time and occurs via the steady accumulation of rigorous empirical work. Whilst we hope that dedicating the remainder of this chapter to SDT (Deci & Ryan, 1985 ) might provide a new perspective from which to formulate coaching research questions and so stimulate further empirical work, our primary aim is to introduce a well-researched theory of human motivation and goal-directed behavior that can both inform the practice of coaching and help to understand its beneficial effects.

Coaching and well-being

What makes coaching an intervention that can influence well-being and happiness? Numerous explanations could be proposed to answer this question. One might be that coaching enhances well-being simply because it focuses on the subjective concerns of individuals and provides a helpful collaborator (i.e., the coach) to assist with resolving those concerns. According to this view, coaching would enhance well-being via the experience of being genuinely supported. A second explanation might be that coaching enhances well-being by providing coachees with rare opportunities to reflect on and (re)discover their personal strengths and capacities. From this perspective, well-being is enhanced through feelings of mastery that build over time. Alternatively, it could be argued that coaching enhances well-being by helping coachees to think deeply about their goals and encouraging them to use values and interests—rather than external inducements or introjects—as a basis for choosing commitments in life. According to this view, it is the developing sense of self-authorship and volition that would lead one to feel good.