Political Cartoon: Yankee Volunteers Marching Into Dixie Essay

Introduction, works cited.

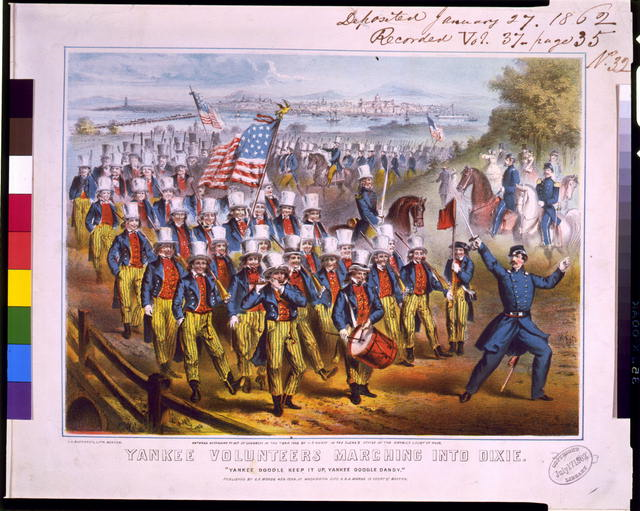

Political cartoons are generally regarded as a hypertrophied imagination of the political or social reality of the particular time epoch. The image that is selected for the analysis is from the pre-1856 epoch of US history, and it represents the imagination of the political and social life as it was imagined by artists. The cartoon that was selected for the analysis is Yankee volunteers marching into Dixie. This is regarded as a music cover 1862 year dated. This is a patriotic, and a bit sarcastic depiction of the Union forces.

The general description of the picture presupposes that the Union forces are marching for opening the Civil War. The troop marches forward, and their dressings are characterized as the Yankee character Brother Jonathan (Brody, 106). The background of the poster depicts the skyline with capitol building. The interpretation of this painting is associated with the events before the civil war and is based on the fact that the Union forces were regarded as the only hope of the democratic development of the further American society.

Because political cartoons were based on the subjective perception of reality, it should be emphasized that the actual importance of the interpretation is associated with the necessity to explain the origins of the artist’s wish to attract attention to the fact of the civil war beginning. By the research by Lent (156), the following statement should be emphasized:

Political prints and satires have, quite appropriately, long been collecting interest for the congressional library. A particularly large group of such works from the late eighteenth century relates to the Revolutionary War period, including historical prints, satires, and allegories by American artists such as Paul Revere and Amos Doolittle, as well as British publishers from across the political spectrum.

In the light of this statement, the historical context of the analyzed poster is mainly associated with the necessity to analyze the sequence of the historic events, as well as the social background and moods of the people and soldiers. Because the poster depicts the very beginning of the Civil War, both sides of the conflict are highly inspired.

The interpretation accuracy may be doubted because the actual importance of the picture was to inspire the audience, and soldiers marching in white top hats look a bit strange. On the other hand, the colors of the US flag were regarded as a patriotic inspiration for everyone who should watch this poster. Therefore, the artist chose to draw the troops in national colors.

From the theoretic perspective of political satire and cartoons, it should be stated that the picture itself was aimed at increasing the level of self-consciousness and patriotism. In the light of this fact, the statement by Winfield and Yoon (234) emphasizes the importance of the political background and the necessity in such cartoons:

As the controversy grew in the United States over the proper form to be given the new government, cartoons and satires became an increasingly vital and ubiquitous component of the national public discourse in the formative years of the young republic. Two of the finest graphic satirists from this period, James Akin and William Charles, are well represented at the Library. For example, a rare impression of Akin’s virulent attack on President Thomas Jefferson for conducting secret negotiations with Spain toward the purchase of West Florida is significant not only as an early presidential satire but also as the earliest-known signed satire by Akin.

Hence, the United States army had to be depicted as a heroic and powerful force. Even though the national forces could not look like this, the authors managed to create the cartoon with a high level of inspiration, and create the necessary mood for motivating people.

The only reason why authors preferred to choose this type of interpretation may be explained by the fact that social advertisement was not developed highly. The national colors were regarded as the only inspirational hook possible for a political cartoon. These colors could be used either as for inspiration or for political sarcasm, however, while the warriors of the Union troops are depicted as dignified people, there is no space for sarcasm

The impact that it might have on the people is linked either with the pride for the dignity of the national troops, or with the irritation and anger of those who were on the opposite side of the barricades. Anyway, the authors reached their goal.

The cartoon analyzed may be regarded from several points, however, the main idea of the image is linked with the inspiration of the target audience. Hence, the interpretation of the cartoon from the perspective of inspiration and motivation may be regarded as the most accurate.

Brody, David and Henretta, James. America: A Concise History: Vol. 1, To 1877 . 4 th edition. New York. 2010.

Lent, John. Animation, Caricature, and Gag and Political Cartoons in the United States . Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004.

Winfield, Betty H., and Doyle Yoon. “Historical Images at a Glance: American Editorial Cartoons.” Newspaper Research Journal 23.4 (2002): 97.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, January 10). Political Cartoon: Yankee Volunteers Marching Into Dixie. https://ivypanda.com/essays/analysis-of-political-cartoon/

"Political Cartoon: Yankee Volunteers Marching Into Dixie." IvyPanda , 10 Jan. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/analysis-of-political-cartoon/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Political Cartoon: Yankee Volunteers Marching Into Dixie'. 10 January.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Political Cartoon: Yankee Volunteers Marching Into Dixie." January 10, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/analysis-of-political-cartoon/.

1. IvyPanda . "Political Cartoon: Yankee Volunteers Marching Into Dixie." January 10, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/analysis-of-political-cartoon/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Political Cartoon: Yankee Volunteers Marching Into Dixie." January 10, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/analysis-of-political-cartoon/.

- "A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court" by Mark Twain

- Friendship in the ‘Because of Winn Dixie’ by Kate Dicamillo

- American Music Bands: Dixie Chicks and The Weavers

- "Dixie": A Racially-Discriminating Song

- "The Contrast” by Royall Tyler

- Explaining Business Model Innovation Processes

- “The Goophered Grapevine” by Charles W. Chesnutt

- Identity Crisis in "Nisei Daughter" by Sone

- Donald Hall: What Makes a Poet Great?

- New York Yankees Franchise in the 1920s and 1930s

- Vietnam War: David Halberstam's "The Making of a Quagmire"

- “The Right Stuff” by Tom Wolfe

- Family Model: Stephanie Coontz’s “What We Really Miss About the 1950s”

- Colonialism Questions: George Washington and Monroe Declaration

- US Southern Command as Command in the Defense Department

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Finance and Business

How to Analyze Political Cartoons

Last Updated: January 16, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was reviewed by Gerald Posner . Gerald Posner is an Author & Journalist based in Miami, Florida. With over 35 years of experience, he specializes in investigative journalism, nonfiction books, and editorials. He holds a law degree from UC College of the Law, San Francisco, and a BA in Political Science from the University of California-Berkeley. He’s the author of thirteen books, including several New York Times bestsellers, the winner of the Florida Book Award for General Nonfiction, and has been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in History. He was also shortlisted for the Best Business Book of 2020 by the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing. There are 8 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 579,573 times.

Political cartoons use imagery and text to comment on a contemporary social issue. They may contain a caricature of a well-known person or an allusion to a contemporary event or trend. [1] X Research source By examining the image and text elements of the cartoon, you can start to understand its deeper message and evaluate its effectiveness.

Examining the Image and Text

Common Symbols in Political Cartoons

Uncle Sam or an eagle for the United States John Bull, Britannia or a lion for the United Kingdom A beaver for Canada A bear for Russia A dragon for China A sun for Japan A kangaroo for Australia A donkey for the US Democratic Party An elephant for the US Republican Party

- Many political cartoonists will include caricatures of well-known politicians, which means they’ll exaggerate their features or bodies for humor, easy identification, or to emphasize a point. For example, an artist might make an overweight politician even larger to emphasize their greed or power.

- For example, if the cartoonist shows wealthy people receiving money while poorer people beg them for change, they’re using irony to show the viewer how wrong they believe the situation to be.

- For example, the stereotype of a fat man in a suit often stands for business interests.

- If you’re analyzing a historical political cartoon, take its time period into account. Was this kind of stereotype the norm for this time? How is the artist challenging or supporting it?

Text in Political Cartoons

Labels might be written on people, objects or places. For example, a person in a suit might be labeled “Congress,” or a briefcase might be labeled with a company’s name.

Text bubbles might come from one or more of the characters to show dialogue. They’re represented by solid circles or boxes around text.

Thought bubbles show what a character is thinking. They usually look like small clouds.

Captions or titles are text outside of the cartoon, either below or above it. They give more information or interpretation to what is happening in the cartoon itself.

- For example, a cartoon about voting might include a voting ballot with political candidates and celebrities, indicating that more people may be interested in voting for celebrities than government officials.

- The effectiveness of allusions often diminishes over time, as people forget about the trends or events.

Analyzing the Issue and Message

- If you need help, google the terms, people, or places that you recognize and see what they’ve been in the news for recently. Do some background research and see if the themes and events seem to connect to what you saw in the cartoon.

- The view might be complex, but do your best to parse it out. For example, an anti-war cartoon might portray the soldiers as heroes, but the government ordering them into battle as selfish or wrong.

- For example, a political cartoon in a more conservative publication will convey a different message, and use different means of conveying it, than one in a liberal publication.

Rhetorical Devices

Pathos: An emotional appeal that tries to engage the reader on an emotional level. For example, the cartoonist might show helpless citizens being tricked by corporations to pique your pity and sense of injustice.

Ethos: An ethical appeal meant to demonstrate the author’s legitimacy as someone who can comment on the issue. This might be shown through the author’s byline, which could say something like, “by Tim Carter, journalist specializing in economics.”

Logos: A rational appeal that uses logical evidence to support an argument, like facts or statistics. For example, a caption or label in the cartoon might cite statistics like the unemployment rate or number of casualties in a war.

- Does it make a sound argument?

- Does it use appropriate and meaningful symbols and words to convey a viewpoint?

- Do the people and objects in the cartoon adequately represent the issue?

Community Q&A

- Keep yourself informed on current events in order to more clearly understand contemporary political cartoons. Thanks Helpful 6 Not Helpful 0

- If you are having trouble discerning the meaning of a political cartoon, try talking with friends, classmates, or colleagues. Thanks Helpful 3 Not Helpful 3

- Historical context: When?

- Intended audience: For who?

- Point of view: Author's POV.

- Purpose: Why?

- Significance: For what reason?

- Political cartoons are oftentimes meant to be funny and occasionally disregard political correctness. If you are offended by a cartoon, think about the reasons why a cartoonist would use certain politically incorrect symbols to describe an issue. Thanks Helpful 14 Not Helpful 2

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://teachinghistory.org/teaching-materials/teaching-guides/21733

- ↑ https://teachinghistory.org/sites/default/files/2018-08/Cartoon_Analysis_0.pdf

- ↑ https://www.metaphorandart.com/articles/exampleirony.html

- ↑ https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/globalconnections/mideast/educators/types/lesson3.html

- ↑ https://www.writerswrite.co.za/the-12-common-archetypes/

- ↑ https://www.lsu.edu/hss/english/files/university_writing_files/item35402.pdf

- ↑ https://www.mindtools.com/axggxkv/paraphrasing-and-summarizing

- ↑ http://www.ysmithcpallen.com/sites/default/files/Analyzing-and-Interpreting-Political-Cartoons1.ppt

About This Article

To analyze political cartoons, start by looking at the picture and identifying the main focus of the cartoon, which will normally be exaggerated for comic effect. Then, look for popular symbols, like Uncle Sam, who represents the United States, or famous political figures. Make note of which parts of the symbols are exaggerated, and note any stereotypes that the artists is playing with. Once you’ve identified the main point, look for subtle details that create the rest of the story. For tips on understanding and recognizing persuasive techniques used in illustration, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Sep 5, 2017

Did this article help you?

Ben Garrison

Jan 1, 2018

Julian Goytia

Nov 4, 2016

Jordy Mc'donald

Oct 29, 2016

Shane Connell

Jun 9, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

The New York Times

The Learning Network | Drawing for Change: Analyzing and Making Political Cartoons

Drawing for Change: Analyzing and Making Political Cartoons

Updated, Nov. 19, 2015 | We have now announced the winners of our 2015 Editorial Cartoon Contest here .

Political cartoons deliver a punch. They take jabs at powerful politicians, reveal official hypocrisies and incompetence and can even help to change the course of history . But political cartoons are not just the stuff of the past. Cartoonists are commenting on the world’s current events all the time, and in the process, making people laugh and think. At their best, they challenge our perceptions and attitudes.

Analyzing political cartoons is a core skill in many social studies courses. After all, political cartoons often serve as important primary sources, showing different perspectives on an issue. And many art, history and journalism teachers take political cartoons one step further, encouraging students to make their own cartoons.

In this lesson, we provide three resources to assist teachers working with political cartoons:

- an extended process for analyzing cartoons and developing more sophisticated interpretations;

- a guide for making cartoons, along with advice on how to make one from Patrick Chappatte, an editorial cartoonist for The International New York Times ;

- a resource library full of links to both current and historic political cartoons.

Use this lesson in conjunction with our Editorial Cartoon Contest or with any political cartoon project you do with students.

Materials | Computers with Internet access. Optional copies of one or more of these two handouts: Analyzing Editorial Cartoons ; Rubric for our Student Editorial Cartoon Contest .

Analyzing Cartoons

While political cartoons are often an engaging and fun source for students to analyze, they also end up frustrating many students who just don’t possess the strategies or background to make sense of what the cartoonist is saying. In other words, understanding a cartoon may look easier than it really is.

Learning how to analyze editorial cartoons is a skill that requires practice. Below, we suggest an extended process that can be used over several days, weeks or even a school year. The strength of this process is that it does not force students to come up with right answers, but instead emphasizes visual thinking and close reading skills. It provides a way for all students to participate, while at the same time building up students’ academic vocabulary so they can develop more sophisticated analyses over time.

Throughout this process, you might choose to alternate student groupings and class formats. For example, sometimes students will work independently, while other times they will work in pairs or small groups. Similarly, students may focus on one single cartoon, or they may have a folder or even a classroom gallery of multiple cartoons.

Open-Ended Questioning

We suggest beginning cartoon analysis using the same three-question protocol we utilize every Monday for our “ What’s Going On in This Picture? ” feature to help students bring to the surface what the cartoon is saying:

- What is going on in this editorial cartoon?

- What do you see that makes you say that?

- What more can you find?

These simple, open-ended questions push students to look closely at the image without pressuring them to come up with a “correct” interpretation. Students can notice details and make observations without rushing, while the cyclical nature of the questions keeps sending them back to look for more details.

As you repeat the process with various cartoons over time, you may want to ask students to do this work independently or in pairs before sharing with the whole class. Here is our editorial cartoon analysis handout (PDF) to guide students analyzing any cartoon, along with one with the above Patrick Chappatte cartoon (PDF) already embedded.

Developing an Academic Vocabulary and a Keener Eye

Once students gain confidence noticing details and suggesting different interpretations, always backed up by evidence, it is useful to introduce them to specific elements and techniques cartoonists use. Examples include: visual symbols, metaphors, exaggeration, distortion, stereotypes, labeling, analogy and irony. Helping students recognize and identify these cartoonists’ tools will enable them to make more sophisticated interpretations.

The Library of Congress (PDF) and TeachingHistory.org (PDF) both provide detailed explanations of what these elements and techniques mean, and how cartoonists use them.

In addition to those resources, three other resources that can help students develop a richer understanding of a cartoon are:

- The SOAPSTone strategy, which many teachers use for analyzing primary sources, can also be used for looking at political cartoons.

- This student handout (PDF) breaks up the analysis into two parts: identifying the main idea and analyzing the method used by the artist.

- The National Archives provides a cartoon analysis work sheet to help students reach higher levels of understanding.

Once students get comfortable using the relevant academic vocabulary to describe what’s going on in a cartoon, we suggest returning to the open-ended analysis questions we started with, so students can become more independent and confident cartoon analysts.

Making an Editorial Cartoon

The Making of an Editorial Cartoon

Patrick Chappatte, an editorial cartoonist for The International New York Times, offers advice on how to make an editorial cartoon while working on deadline.

Whether you are encouraging your students to enter our Student Editorial Cartoon Contest , or are assigning students to make their own cartoons as part of a history, economics, journalism, art or English class, the following guide can help you and your students navigate the process.

Learn from an Editorial Cartoonist

We asked Patrick Chappatte, an editorial cartoonist for The International New York Times, to share with us how he makes an editorial cartoon on deadline, and to offer students advice on how to make a cartoon. Before watching the film above, ask students to take notes on: a) what they notice about the process of making a cartoon, and b) what advice Mr. Chappatte gives students making their own cartoons.

After watching, ask students to share what information they find useful as they prepare to make their own editorial cartoons.

Then, use these steps — a variation on the writing process — to help guide students to make their own cartoons.

Step 1 | Brainstorm: What Is a Topic or Issue You Want to Comment On?

As a professional cartoonist, Mr. Chappatte finds themes that connect to the big news of the day. As a student, you may have access to a wider or narrower range of topics from which to choose. If you are entering a cartoon into our Student Editorial Cartoon Contest, you can pick any topic or issue covered in The New York Times, which not only opens up the whole world to you, but also historical events as well — from pop music to climate change to the Great Depression. If this a class assignment, you may have different instructions.

Step 2 | Make a Point: What Do You Want to Say About Your Topic?

Once you pick an issue, you need to learn enough about your topic to have something meaningful to say. Remember, a political cartoon delivers commentary or criticism on a current issue, political topic or historical event.

For example, if you were doing a cartoon about the deflated football scandal would you want to play up the thought that Tom Brady must have been complicit, or would you present him as a victim of an overzealous N.F.L. commissioner? Considering the Republican primaries , would you draw Donald Trump as a blowhard sucking air out of the room and away from more serious candidates, or instead make him the standard- bearer for a genuine make-America-great-again movement?

You can see examples of how two cartoonists offer differing viewpoints on the same issue in Newspaper in Education’s Cartoons for the Classroom and NPR’s Double Take .

Mr. Chappatte explains that coming up with your idea is the most important step. “How do ideas come? I have no recipe,” he says. “While you start reading about the story, you want to let the other half of your brain loose.”

Strategies he suggests for exploring different paths include combining two themes, playing with words, making a joke, or finding an image that sums up a situation.

Step 3 | Draw: What Are Different Ways to Communicate Your Ideas?

Then, start drawing. Try different angles, test various approaches. Don’t worry too much about the illustration itself; instead, focus on getting ideas on paper.

Mr. Chappatte says, “The drawing is not the most important part. Seventy-five percent of a cartoon is the idea, not the artistic skills. You need to come up with an original point of view. And I would say that 100 percent of a cartoon is your personality.”

Consider using one or more of the elements and techniques that cartoonists often employ, such as visual symbols, metaphors, exaggeration, distortion, labeling, analogy and irony.

Step 4 | Get Feedback: Which Idea Lands Best?

Student cartoonists won’t be able to get feedback from professional editors like Mr. Chappatte does at The International New York Times, but they should seek feedback from other sources, such as teachers, fellow students or even family members. You certainly can ask your audience which sketch they like best, but you can also let them tell you what they observe going on in the cartoon, to see what details they notice, and whether they figure out the ideas you want to express.

Step 5 | Revise and Finalize: How Can I Make an Editorial Cartoon?

Once you pick which draft you’re going to run with, it’s time to finalize the cartoon. Try to find the best tools to match your style, whether they are special ink pens, markers or a computer graphics program.

As you work, remember what Mr. Chappatte said: “It’s easier to be outrageous than to be right on target. You don’t have to shoot hard; you have to aim right. To me the best cartoons give you in one visual shortcut everything of a complex situation; funny and deep, both light and heavy; I don’t do these cartoons every day, not even every week, but those are the best.” That’s the challenge.

Step 6 | Publish: How Can My Editorial Cartoon Reach an Audience?

Students will have the chance to publish their editorial cartoons on the Learning Network on or before Oct. 20, 2015 as part of our Student Contest. We will use this rubric (PDF) to help select winners to feature in a separate post. Students can also enter their cartoons in the Scholastic Arts & Writing Awards new editorial cartoon category for a chance to win a national award and cash prize.

Even if your students aren’t making a cartoon for our contest, the genre itself is meant to have an audience. That audience can start with the teacher, but ideally it shouldn’t end there.

Students can display their cartoons to the class or in groups. Classmates can have a chance to respond to the artist, leading to a discussion or debate. Students can try to publish their cartoons in the school newspaper or other local newspapers or online forums. It is only when political cartoons reach a wider audience that they have the power to change minds.

Where to Find Cartoons

Finding the right cartoons for your students to analyze, and to serve as models for budding cartoonists, is important. For starters, Newspaper in Education provides a new “ Cartoons for the Classroom ” lesson each week that pairs different cartoons on the same current issue. Below, we offer a list of other resources:

- Patrick Chappatte

- Brian McFadden

A Selection of the Day’s Cartoons

- Association of American Editorial Cartoonists

- U.S. News and World Report

Recent Winners of the Herblock Prize, the Thomas Nast Award and the Pulitzer Prize

- Kevin Kallaugher in the Baltimore Sun

- Jen Sorensen in The Austin Chronicle

- Tom Tomorrow in The Nation

- Signe Wilkinson in the Philadelphia Daily News

- Adam Zyglis in The Buffalo News

- Kevin Siers in The Charlotte Observer

- Steve Sack in the Star Tribune

Historical Cartoonists

- Thomas Nast

- Paul Conrad

Other Historical Cartoon Resources

- Library of Congress | It’s No Laughing Matter

- BuzzFeed | 15 Historic Cartoons That Changed The World

Please share your own experiences with teaching using political cartoons in the comments section.

What's Next

- Source Criticism

- Interpretation

- Political Cartoons

How to interpret the meaning of political cartoons

Interpreting a visual source , like a political cartoon, is very different to interpreting words on a page, which is the case with written sources .

Therefore, you need to develop a different set of skills.

What is a 'political cartoon'?

Political cartoons are ink drawings created to provide a humorous or critical opinion about political events at the time of its creation.

They were particularly popular in newspapers and magazines during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. However, they are still used by many newspapers, magazines and websites today.

While political cartoons can be funny, that is usually not their main purpose. They were primarily created to persuade their audience to take a particular view on a historical event.

A successful political cartoon can change someone’s mind so that they ultimately agree with the cartoonist’s point of view.

Further information:

Learn more about the history of the political cartoon with this short YouTube clip:

If you've never seen a political cartoon before, you can see a contemporary one being made below:

How do I understand the meaning of a political cartoon?

Understanding what a historical political cartoon means can be difficult for us because we did not live through the political events the cartoons talk about.

However, all political cartoons rely heavily upon a very simple visual ‘code’ rather than relying solely on words to convey their message.

Once we learn how this visual code works, we can use it to ‘decode’ the specific message of a cartoon.

Political Cartoon Visual Codes

Cartoonists intentionally draw people or characters with physical features that are larger than they naturally are. They do this in order to make a point.

Usually, the point is to highlight something about the character of a person. For example, if a person is drawn with a large, toothy grin, it can be a sign that they have evil intentions and are untrustworthy.

Therefore, when interpreting a cartoon, look for any physical features that seem obviously exaggerated. Then, try to decide what point the creator was trying to make about the person.

If you want to see how a cartoonist uses caricatures, watch the short clip below:

To help their audience understand what each person represents in their drawings, cartoonists often write a name on the major figures. Common names include famous politicians or countries.

So, when you’re interpreting a cartoon, look for the labels. You might need to do some background research to find out who the people are before you continue with your interpretation.

3. Symbolism

Cartoonists use simple objects, or symbols, that the general public would be familiar with. These symbols are used to represent important concepts or ideas.

For example, using a ‘skull and crossbones’ could represent ‘death’ or ‘danger’. While you’re interpreting a cartoon, identify any symbols and try to work out what concept the image is meant to represent.

Here are some common symbols used in political cartoons, along with their common meanings:

4. Captions

Another handy way that cartoonists convey important information to their audience is by providing a written explanation through a speech bubble in the cartoon itself or a caption at the bottom of the image.

These words should help you understand the main historical event or issue that the image is based upon.

5. Analogies

An analogy is a comparison between two different things to highlight a particular similarity in ideas. Through the comparison of a complex political issue with more simplistic, 'everyday' scenarios with which the audience would be more familiar, a cartoonist can more easily convey their message.

Here are some common analogies and what they could mean in political cartoons:

6. Stereotypes

It was very common for cartoonists to represent a particular group of people (usually in a very racist way) using stereotypes.

A stereotype is an over-simplification of what a particular racial group looks like. For example, Chinese people in the 19th century were drawn with a long pony-tail in their hair.

Cartoonists use this so that audiences can readily identify which people group is the target of the cartoon. Getting to know common stereotypes can be quite confronting for us, since they can be very derogatory in nature.

However, once you become familiar with common forms of stereotyping, you can identify the appropriate people group being targeted in a particular cartoon.

Common Stereotypes:

People Group:

Australians

Jewish People

Exaggerated Features:

Pickelhaube (the spiked helmet), gorilla-like body

Long ponytail, narrow eyes, thin moustache, traditional Chinese clothes and hat, two large front teeth

Circular glasses, narrow eyes, toothy grin

Slouch hat, clean-shaven, khaki clothes

Large nose, kippah (Jewish prayer cap)

How do I write an interpretation?

Once you have deconstructed the cartoon, now you can start creating your explanation. To do so, answer the following questions:

- Who or what is represented by the characterisation, stereotypes and symbols?

- Who or what have been labelled?

- What information is provided by the caption?

- What is the political issue being mentioned in the cartoon? (You may need to do some background research to discover this).

- What is the analogy that this cartoon is based upon?

Once you have answered these questions, you are ready to answer the final one:

- What did the cartoonist want the audience to think about the issue?

What do I do with my interpretation?

Identifying the message of a political cartoon shows that you understand the primary source, which means that you can use it as an indirect quote in your historical writing.

Your interpretation can also help you in your analysis and evaluation of the source. For example, identifying the source's message can help you ascertain:

- The purpose of the cartoon

- The motive of the cartoonist

- The relevance of the source to your argument

- The accuracy of the information presented in the image

Frith, J. (31st December, 1941). 'No offence, mum...', The Bulletin.

Demonstrating interpretation of political cartoons in your writing:

The political cartoon by Frith makes a comment on Australia's changing diplomatic relationships between Great Britain and America during the Second World War. The cartoonist does this through the depiction of three main characters. The man on the left is clearly a caricature of Australian prime minister John Curtin, as he was commonly drawn with his distinctive hat and glasses. The woman on the right of the image is meant to symbolise Great Britain. This symbolism is clear due to the use of the Union Jack, the flag of Great Britain, drawn upon her apron. Furthermore, she is depicted as the mythical figure of Britannia, a common representation of Britain. The second woman is meant to be America, as she is drawn with a stereotypical 1940s American hairstyle and clothing. This symbolism is reinforced by the depiction of the stripes of the American flag drawn on her apron. The primary analogy the cartoon uses is the idea of 'holding onto your mother's apron strings', which is used to describe a young child depending on their mother for comfort and security. This analogy is evident in the image caption which explicitly states that Curtin is "shifting to these here apron strings". The overall message of the cartoon is that Curtin is switching Australia's dependence from Great Britain to America for comfort and security. It is meant to be a satirical comment on the childish dependency that Australia demonstrated during the early years of the Second World War.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

A Semiotic Analysis of Political Cartoons

Cynthia Bailey Lee

CSE 271, Spring 2003

Professor Joseph Goguen

June 5, 2003

Political cartoons historically and currently play a significant role in public discourse about serious and important issues. They are also most often funny. This paper presents a formal analysis of political cartoons using methods from classical semiotics, semiotic morphisms, and in particular the study of blends. This includes rigorously addressing questions such as why the humor in political cartoons has a different flavor from most other cartoons, how political cartoons achieve serious commentary and humor, and what literary structures characterize political cartoons’ visual style. A selection of political cartoons are analyzed in detail.

1 Introduction

A cartoon is ``a drawing, representational or symbolic, that makes a satirical, witty, or humorous point.'' [5] This work focuses attention on a particular kind of cartoon, the political cartoon. In addition to the obvious difference in subject matter for political cartoons compared to other types of cartoons, political cartoons constitute a distinct class visually. Also, while most political cartoons are funny in some sense, it is not the sense in which most other cartoons are funny.

The origins of the modern political cartoon can be traced to the 16th century, with drawings used in the theological debates of the Reformation. The cartoon style as such developed in Britain in the 1800's and is distinguished by the use of caricature. [5] Throughout much of the United States' history, political cartoons have held a prominent place. During the Civil War era, Thomas Nast's mastery of the medium was applied very effectively to the defense of Lincoln's policies. Nast is the inventor of Donkey and Elephant signs that remain today the de facto standard signs for the Democratic and Republican parties, respectively. Additionally, his influence is credited with the overthrow of the corrupt ``Boss'' Tweed government of New York City. [5]

To achieve such ambitious practical results as these, political cartoons must strike a delicate balance between telling things that seem real and true, and using wild imagination, exaggeration and humor. The result is to drive home a powerful and relevant message in a pleasant way. Indeed, this is the essence of caricature, or satire, which is the basis for political cartoons' effect. But what does it mean structurally and mathematically to be caricature or satire? The rest of the paper will address this question using methods from classical semiotics, semiotic morphisms and particularly blends.

First, a comment about the interpretation of political cartoons as presented in this paper. This is not a paper about politics, but rather how political thoughts and opinions are expressed through complex signs. In general, the worldview of the artist will be accepted as truth for the sake of analysis. Furthermore, the words used here in the labeling of concepts from the cartoons were chosen with a large amount of arbitrariness, as they are generally unimportant in the analysis.

2 Saussure and Sign Systems

In linguist Ferdinand de Saussure's study of signs, he emphasized the importance of studying whole systems of signs, rather than simply doing individual analysis. He claimed that signs draw meaning and significance from the way they interact with other signs in the system. In particular, he observed that ``concepts...are defined not positively, in terms of their content, but negatively by contrast with other items in the same system'' [1][2](editing and emphasis as given in [3]). This principle is nicely illustrated in the following cartoon (Figure 1).

Figure 1: February 10, 2003 [4]

What strikes one first about the cartoon is the relative difference in size and fuse length of the two ``bombs.'' One also notices a difference in the person depicted as the bombs' ``heads.'' The likeness of George W. Bush acts as a means of further distinguishing these two signs; he lights the fuse of a distant bomb while turning his back on the closer one. Thus he creates a contrast between them, both in terms of a spatial relationship and a mode of interaction. Together these contrasts form part of the core meaning of this cartoon, which is a contrast between nations, a contrast between policies towards nations, and a contradictory matching between nations and policies. But how exactly are these images and signs related to nations and policies? To answer this question, we turn to a structural study of the meaning of complex metaphorical signs known as blending.

3 Blending

The most basic intuition for identifying a blend in this cartoon is to notice that while the images of the bombs play a metaphorical role in describing geopolitical relationships between the United States, North Korea, and Iraq, what is seen cannot be a simple projection from a geopolitical space to a metaphorical ``bombs with fuses'' space. This is because elements of the source space are visible in what is supposed to be the target space! The natural explanation for the coexistence of elements from both the source and target spaces is that a new blended space has been created. Figures 2 and 3a below compare the structures of traditional metaphor theory and blend theory. Figure 3b shows how the blend analysis works for this cartoon.

Figure 2: Traditional Metaphor Analysis

Figures 3a and 3b: Blending Analysis [*]

In the blending theory, the source and target spaces are both called input spaces, since they both contribute to the blended space. Notice that in addition to the blended space, a generic space has been added. The purpose of the generic space is to define at a very high level the nature of the structures internal to the three other spaces. This will become clearer by looking in more detail at the ``bomb'' cartoon example. First, since Iraq and North Korea are really two different conceptual spaces, we amend Figure 3b to include three input spaces, something not generally possible in traditional metaphor analysis (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Amended Blend Analysis

Figures 5: Detail of Blend Analysis

Figure 5 gives the detail of the structures internal to the nodes shown in Figure 4. The three input space structures are found by taking an interpretation of international politics, and knowledge of how bombs and fuses work. Observe that the structure of the three input spaces is strikingly similar. A generalization of this similarity is defined in the generic space, and one particular way of blending the two input spaces, the one shown in the cartoon, is defined in the blended space.

In the blended space, the Bush and the Bomber nodes have been fused to a single Bomber-Bush. This in itself has significance for the meaning that is emergent in the blended space, in other words, is not found in any input space. Since each input space is its own sphere, it is only in the blended space that such a profound and dangerous contradiction between the policies towards Iraq and North Korea, and the immediacy of the danger posed by each can be seen. Also, because the Bomber figure is fused with Bush , and bombers are generally thought of as dangerous and even evil, the fusing of this figure with Bush is particularly unflattering.

Another structural difference between the blended space and the input spaces is that in the blended space there is a loop; the North Korea bomb ``will injure'' Bomber-Bush , who lit the fuse. However, in the input space, war with North Korea ``will injure'' a third party, United States . The ``bombs with fuses'' input space also implicitly assumes that Victim is different from Bomber . President Bush is certainly part of the United States, and as such would be injured if the United States in general were injured, so in an indirect sense the concept of Bush hurting himself can be found in an input space. But a strong, direct conclusion about the self-injury aspect of Bush's neglect of North Korea can only be found in the emergent meaning of the blended space.

This exemplifies how blending theory helps define satire, the genre of humor used in political cartoons. Satire does not seek to create totally new meaning, else it would not be relevant to real events; rather satire reconfigures spaces to emphasize, illustrate, and comment.

4 Semiotic Morphisms

The contribution of semiotic morphisms to the analysis above can be seen in that there is not only structure connecting the conceptual spaces, but also structure within them, and these structures also have inter-relationships. What makes a metaphor or blend work, what defines the quality of the choice of target or input spaces, is the degree to which the mappings between spaces preserve this structure. [8] As discussed above, the relationships between elements in the ``bombs with fuses'' space mirror the important relationships in the North Korea and Iraq spaces, and all are mirrored in the blended space. This is why readers are able to make sense of the metaphor, and why the emergent meaning of the blended space is accepted (because it does not stray too far from known reality). For a formal, explicit listing of the morphisms between the five conceptual spaces, see Appendix A: BOBJ Code for the ``Bombs'' Cartoon.

5 Metonymy and Metonymic Tightening

This cartoon also makes for an interesting study of the use of metonymy. Metonymy is defined as ``a trope in which one word is put for another that suggests it.''[7] An obvious example is the use of caricatures of the leaders of the various countries as representatives for the countries themselves. In other words, Kim Jung Il the man, though no doubt ruthless, is not the real danger to the United States; it is North Korea's advanced weaponry. President Bush is an interesting example because he represents himself directly in terms of policy-making, but in terms of the danger posed by North Korea, also stands in for the United States. Metonymy is widely used in political cartoons, and helps to define their distinctive caricature visual style.

Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner formalized the concept of metonymy in terms of its application to blends. As the last of their six ``optimality principles,'' conditions for successful blends, they define the Metynomic Projection Constraint (or as it has come to be known, Metynomic Tightening) as ``when an element is projected from an input to the blend and a second element from that input is projected because of its metonymic link to the first, shorten the metonymic distance between them in the blend.'' [6]

A classic example is the embodiment of Death in western tradition as a cloaked skeleton. The metaphor of death is garnished with an element that is literally associated with dead things (i.e. a skeleton). [6] In this case, bombs, as a weapon, have a metonymic link to the concept of war and danger.

6 Further Example

Now that the major elements of semiotics, semiotic morphisms and blends have been introduced, we present a brief analysis of a second cartoon for reinforcement.

Figure 6: March 28, 2003 [9]

In this cartoon, we see the conventional stereotype of a family vacation where the children do nothing but ask ``Are we there yet?'' of their embattled parents, combined with U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and the news media. Formally, this corresponds to the following blend diagram:

Figure 7: Detail of Blend Analysis

In this case, the emergent meaning of the blended space derives from a mismatch in the connotations of the Result node in the Family Vacation space and the War space. In a family vacation, one generally assumes that the Destination is something exciting, say Disneyland, to naturally be desired and eagerly awaited by the children. However, in the case of the War Space, one would never hope for the kind of disaster that happened in Vietnam, a Failed, Expensive War . (Note the use of metonymy; Vietnam the country replaces Vietnam the war, which in turn stands for the abstract concept of a disastrous military campaign.) But in the blended space, the eagerness of children to arrive at Destination is fused with the zeal with which reporters ask Rumsfeld about struggles in the war in Iraq, to lead to a grotesque situation where reporters seem to desire horrible things to happen. Indeed, the inappropriateness of this seemingly too-eager attitude is both the ``punch line'' and serious message of the cartoon. Notice that the full effect of this conclusion can only be reached in the blended space, a condition Grady, Oakley, and Coulson call the `` chief diagnostic for the occurrence of blending .'' [10]

7 Reblending

Though more common to non-political cartoons, reblending is a common process by which humor is created. In part, reblending is more common to other types of cartoons because they are more likely to be multi-frame, but this can occasionally be seen in political cartoons such as the one in Figure 8, below.

Figure 8: May 29, 2003 [11]

The essence of reblending is that the reader is led to form one blended space, then given new information that reinterprets the input spaces and creates a different, usually contradictory, blended space. [12] In the first frame above, we have the space of back-patting, blended with the space of Iraqi-US relations, yielding a blend that seems to say Iraqis have love and gratitude for the US. In the second frame, the same two input spaces are reblended to say that Iraqis do not like the US, a direct contradiction of the first blend.

8 Conclusion

In The Literary Mind, Mark Turner argues that complex metaphorical and blending patterns, such as those in the cartoons seen in this paper, are fundamental to the way humans think and reason. [13] Indeed, he argues that almost no thought or reason can take place without these seemingly advanced processes. This may explain the surprising fact that political cartoons, on the surface a not ``serious'' art form, are so successful in helping society to understand and make judgments about the extremely complex interactions at work in political systems. In this paper, the nature of political cartoons' signature caricature-based visual style was linked to metonymy and metonymic tightening. Political cartoon's particular flavor of humor, satire, was understood in terms of the emergent meaning in blended spaces. Finally, the classical semiotic study of contrasts between signs in sign systems was shown to characterize a common practice in political cartoons.

Appendix A: BOBJ Code for the ``Bombs'' Cartoon

In the text of this paper, the mathematical structure of the blends was represented in visual diagrams. For the purposes of very rigorous analysis, a formal language for these structures becomes convenient. Such a language is presented in Joseph Goguen's ``An Introduction to Algebraic Semiotics, with Application to User Interface Design,'' using OBJ3 (now BOBJ). [14] The following is essentially a transcription of Figure 5 using the methods described there. An explanation of these methods is beyond the scope of this paper, though the basic points can be learned by comparing the code below to Figure 5. Note that the objection that the BOBJ interpreter raises to the code below, that Bush-Bomber acts as both Person and People from the generic space, is quite correct and highlights the unusualness of that loop structure.

obj DATA is pr BOOL .

sort Person .

sort People .

op unknown1 : -> Person .

op unknown2 : -> People .

th NKOREA is sorts Process Result . pr DATA .

op conflict-escalation : -> Process .

op war-NKorea : -> Result .

op US : -> People .

op initiates : Person Process -> Bool .

op ends-in : Process Result -> Bool .

op will-injure : Result People -> Bool .

eq ends-in(conflict-escalation, war-NKorea) = true .

eq will-injure(war-NKorea, US) = true .

th IRAQ is sorts Process Result . pr DATA .

op Bush : -> Person .

op war-Iraq : -> Result .

op effects : Result People -> Bool .

eq initiates(Bush, conflict-escalation) = true .

eq ends-in(conflict-escalation, war-Iraq) = true .

th BOMBS-WITH-FUSE is sorts Process Result . pr DATA .

op bomber : -> Person .

op burning-fuse : -> Process .

op bomb-explosion : -> Result .

op victim : -> People .

op lights : Person Process -> Bool .

op injures : Result People -> Bool .

eq lights(bomber, burning-fuse) = true .

eq ends-in(burning-fuse, bomb-explosion) = true .

eq injures(bomb-explosion, victim) = true .

th GENERIC is sorts Process Result . pr DATA .

op person : -> Person .

op process : -> Process .

op result : -> Result .

op people : -> People .

eq initiates(person, process) = true .

eq ends-in(process, result) = true .

eq effects(result, people) = true .

view M1 from GENERIC to NKOREA is

op process to conflict-escalation .

op result to war-NKorea .

op people to US .

op effects to will-injure .

view M2 from GENERIC to IRAQ is

op person to Bush .

op result to war-Iraq .

view M3 from GENERIC to BOMBS-WITH-FUSE is

op person to bomber .

op process to burning-fuse .

op result to bomb-explosion .

op people to victim .

op initiates to lights .

op effects to injures .

th CARTOON is sorts Process Result . pr DATA .

op bomber-BushA : -> Person .

op Hussein-bomb-explode : -> Result .

op Il-bomb-explode : -> Result .

op bomber-BushB : -> People .

eq lights(bomber-BushA, burning-fuse) = true .

eq ends-in(burning-fuse, Hussein-bomb-explode) = true .

eq ends-in(burning-fuse, Il-bomb-explode) = true .

eq will-injure(Il-bomb-explode, bomber-BushB) = true .

view M4 from NKOREA to CARTOON is

op conflict-escalation to burning-fuse .

op war-NKorea to Il-bomb-explode .

op US to bomber-BushB .

view M5 from IRAQ to CARTOON is

op Bush to bomber-BushA .

op war-Iraq to Hussein-bomb-explode .

view M6 from GENERIC to CARTOON is

op person to bomber-BushA .

op result to Hussein-bomb-explode .

op result to Il-bomb-explode .

op people to bomber-BushB .

Bibliography

[1] Saussure, Ferdinand de. Course in General Linguistics (trans. Roy Harris). London: Duckworth. [1916] 1983.

[2] Saussure, Ferdinand de. Course in General Linguistics (trans. Wade Baskin). London: Fontana/Collins. [1916] 1974.

[3] Chandler, Daniel. Semiotics for Beginners . (see also print version, Semiotics: The Basics . Routledge. November 2001.) http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/S4B/semiotic.html .

[4] Cagle, Daryl. Cartoon dated February 10, 2003. Slate. See http://cagle.slate.msn.com/politicalcartoons/ .

[5] Low, David and Williams, R. E. ``Political Cartoon,'' The American Presidency . Grolier. 2000.

[6] Fauconnier, Gilles and Turner, Mark. ``Conceptual Integration Networks,'' Cognitive Science , 22(2) 1998, 133-187.

[7] Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary , © 1996, 1998 MICRA, Inc.

[8] Goguen, Joseph. ``An Introduction to Algebraic Semiotics, with Applications to User Interface Design,'' in Chrystopher Nehaniv, editor, Computation for Metaphors, Analogy and Agents . Springer, Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence, Volume 1562, 1999, pages 242-291.

[9] Cagle, Daryl. Cartoon dated March 28, 2003. Slate. See http://cagle.slate.msn.com/politicalcartoons/ .

[10] Grady, Joseph, Oakley, Todd and Coulson, Seana. ``Blending and Metaphor,'' Metaphor in Cognitive Linguistics , G. Steen and R. Gibbs (eds.). Philadelphia. 1999

[11] Parker, Jeff. Cartoon dated May 29, 2003. Slate. See http://cagle.slate.msn.com/politicalcartoons/ .

[12] Goguen, Joseph. ``Towards a Design Theory for Virtual Worlds: Algebraic semiotics, with information visualization as a case study,'' Proceedings, Conference on Virtual Worlds and Simulation , C. Landauer and K. Bellman (eds.), Society for Modelling and Simulation, 2001, pages 298-303.

[13] Turner, Mark. The Literary Mind. Oxford University Press, New York. 1996.

[14] Goguen, Joseph. ``An Introduction to Algebraic Semiotics, with Applications to User Interface Design,'' Computation for Metaphors, Analogy and Agents , C. Nehaniv (ed), Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence , Volume 1562. Springer, 1999, pages 242-291.

[*] The acronym POTUS means President of the United States.

Analyzing the Purpose and Meaning of Political Cartoons

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources

The decisions students make about social and political issues are often influenced by what they hear, see, and read in the news. For this reason, it is important for them to learn about the techniques used to convey political messages and attitudes. In this lesson, high school students learn to evaluate political cartoons for their meaning, message, and persuasiveness. Students first develop critical questions about political cartoons. They then access an online activity to learn about the artistic techniques cartoonists frequently use. As a final project, students work in small groups to analyze a political cartoon and determine whether they agree or disagree with the author's message.

Featured Resources

It’s No Laughing Matter: Analyzing Political Cartoons : This interactive activity has students explore the different persuasive techniques political cartoonists use and includes guidelines for analysis.

From Theory to Practice

- Question-finding strategies are techniques provided by the teacher, to the students, in order to further develop questions often hidden in texts. The strategies are known to assist learners with unusual or perplexing subject materials that conflict with prior knowledge.

- Use of this inquiry strategy is designed to enhance curiosity and promote students to search for answers to gain new knowledge or a deeper understanding of controversial material. There are two pathways of questioning available to students. Convergent questioning refers to questions that lead to an ultimate solution. Divergent questioning refers to alternative questions that lead to hypotheses instead of answers.

Common Core Standards

This resource has been aligned to the Common Core State Standards for states in which they have been adopted. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, CCSS alignments are forthcoming.

State Standards

This lesson has been aligned to standards in the following states. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, standard alignments are not currently available for that state.

NCTE/IRA National Standards for the English Language Arts

- 1. Students read a wide range of print and nonprint texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works.

- 6. Students apply knowledge of language structure, language conventions (e.g., spelling and punctuation), media techniques, figurative language, and genre to create, critique, and discuss print and nonprint texts.

- 8. Students use a variety of technological and information resources (e.g., libraries, databases, computer networks, video) to gather and synthesize information and to create and communicate knowledge.

- 11. Students participate as knowledgeable, reflective, creative, and critical members of a variety of literacy communities.

Materials and Technology

- Computers with Internet access and printing capability

- Several clips of recent political cartoons from a local newspaper

- Overhead projector or computer with projection capability

- Editorial Cartoon Analysis

- Presentation Evaluation Rubric

Preparation

Student objectives.

Students will

- Develop critical question to explore the artistic techniques used in political cartoons and how these techniques impact a cartoon's message

- Evaluate an author or artist's meaning by identifying his or her point of view

- Identify and explain the artistic techniques used in political cartoons

- Analyze political cartoons by using the artistic techniques and evidence from the cartoon to support their interpretations

Session 2 (may need 2 sessions, depending on computer access)

Sessions 3 and 4.

- Daryl Cagle's Professional Cartoonist Index and The Association of American Editorial Cartoonists: Cartoons for the Classroom both provide additional lesson plans and activities for using political cartoons as a teaching tool. Students can also access these online political cartoons for additional practice in evaluating their meaning, message, and persuasiveness.

- Students can create their own political cartoons, making sure to incorporate a few of the artistic techniques learned in this lesson. Give students an opportunity to share their cartoons with the class, and invite classmates to analyze the cartoonist's message and voice their own opinions about the issue.

- This lesson can be a launching activity for several units: a newspaper unit, a unit on writing persuasive essays, or a unit on evaluating various types of propaganda. The ReadWriteThink lesson "Propaganda Techniques in Literature and Online Political Ads" may be of interest.

Student Assessment / Reflections

Assessment for this lesson is based on the following components:

- The students' involvement in generating critical questions about political cartoons in Lesson 1, and then using what they have learned from an online activity to answer these questions in Lesson 2.

- Class and group discussions in which students practice identifying the techniques used in political cartoons and how these techniques can help them to identify an author's message.

- The students' responses to the self-reflection questions in Lesson 4, whereby they demonstrate an understanding of the purpose of political cartoons and the artistic techniques used to persuade a viewer.

- The final class presentation in which students demonstrate an ability to identify the artistic techniques used in political cartoons, to interpret an author's message, and to support their interpretation with specific details from the cartoon. The Presentation Evaluation Rubric provides a general framework for this assessment.

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

Module 10: Westward Expansion (1800-1860)

Reading political cartoons, learning objectives.

- Identify the different components of a political cartoon

Part One: Analyzing Visual Components

A political cartoon, a type of editorial cartoon, is a cartoon graphic with caricatures of public figures, expressing the artist’s opinion. They typically combine artistic skill, hyperbole, and satire in order to question authority and draw attention to corruption, political violence, or other social ills.

First, we will walk through a political cartoon analysis together.

Worked Example, Southern Ideas of Liberty:

The political cartoon below was published around 1835 by an anonymous author, possibly in Boston. It is a response to the tarring, feathering, and lynching of anti-slavery activists in several southern states. Around 1835, several slave states passed resolutions calling for the North to suppress abolitionist activities and societies, as they were a threat to the slave-labor economy of the South. The image is titled “Southern Ideas of Liberty.”

Figure 1 . 1835 political cartoon titled “Southern Ideas of Liberty.”

In the image, a judge with ass’s ears and a whip, seated on bales of cotton and tobacco with the Constitution underfoot, condemns a White man (an abolitionist) to hanging. The prisoner is roughly dragged by two captors toward a crowd of jubilant men who surround a gallows. In the distance, a cauldron of tar boils over an open fire.

The text below the image reads:

Sentence passed upon one for supporting that clause of our Declaration viz. All men are born free & equal. “Strip him to the skin! give him a coat of Tar & Feathers!! Hang him by the neck, between the Heavens and the Earth!!! as a beacon to warn the Northern Fanatics of their danger!!!!” [1]

What to Look For

The visual components of a political cartoon are the ones you can see in the image. They speak to artistic choice, symbolism, and realism vs. fantasy. What visual elements do you see in the political cartoon above? As you read through the list below, look at the image and think about how each visual element was carefully chosen by the artist to send a message or evoke an emotion.

Who are the people depicted in the cartoon? Are they real historical individuals or are they symbolic of a larger group or movement? Where are the characters in relation to each other?

Often, animals are used in political cartoons in place of people or institutions (like the snake in Ben Franklin’s cartoon on the previous page) – do you see any animals or humans who have been given animal or animal-like features? What are some common traits or characteristics assigned to that animal? What might be the historical context of the animal being used?

Buildings or Furniture

Do you see any buildings in the image? What type of building is it? Is it standing or crumbling? Is there any furniture in the image like a throne, a chair, a table, a carpet, etc? Is it luxurious furniture or is it rough? What might be the purpose of including certain types of furniture?

Look for any other objects in the image like ladders, trees, household items, boats, trains, etc. What do you think they represent? Is it a direct representation or a symbolic representation? How is it being used and by whom?

Do you see any logos, insignias, flags, shapes, or other symbols? What group or person are they connected to? Where are they in the image in relationship to the other visual components? Are they being used to label another component?

Style Choices

This section pertains more to how the artist drew the visual elements, rather than what they drew. Look for elements like exaggeration of features or objects, irony in the way people or objects are depicted in relationship to one another (irony is defined as “a state of affairs or an event that seems deliberately contrary to what one expects”), or the use of analogy comparing a complex situation or issue to a simple one in order to make it easier to understand (i.e., comparing a presidential election to a horse race).

As you can see, analyzing a political cartoon is not always cut and dry. Sometimes, one element can fall into multiple categories or be from different perspectives. Much of this analysis is “could be,” since we do not know what the author’s actual intention was when the cartoon was created. We can only speculate based on what we see and what we know. The following Practice Questions will test your ability to analyze the visual components of a different cartoon.

Answer the questions below based on the cartoon above.

Visual Components

- “Grand Presidential Sweepstakes for 1849.”

- “An Available Candidate.”

- “Cock of the Walk.”

- Figures – who are the people depicted in the cartoon? Are they real historical individuals or are they symbolic of a larger group or movement? Where are the characters in relationship to each other?

- Animals – often, animals are used in political cartoons in place of people or institutions (like the snake in Ben Franklin’s cartoon above) – do you see any animals or humans who have been given animal or animal-like features? What are some common traits or characteristics assigned to that animal? What might be the historical context of the animal being used?

- Buildings and/or Furniture – do you see any buildings in the image? What type of buildings is it? Is it standing or crumbling? Is there any furniture in the image like a throne, a chair, a table, a carpet, etc? Is it luxurious furniture or is it rough? What might be the purpose of including certain types of furniture?

- Objects – look for any other objects in the image like ladders, trees, household items, boats, trains, etc. What do you think they represent? Is it a direct representation or a symbolic representation? How is it being used and by whom?

- Symbols – do you see any logos, insignias, flags, shapes, or other symbols? What group or person are they connected to? Where are they in the image in relationship to the other visual components? Are they being used to label another component?

- Style Choices – this is more about how the artist drew the visual elements, rather than what they drew. Look for elements like exaggeration of features or objects, irony in the way people or objects are depicted in relationship to one another (irony is defined as “a state of affairs or an event that seems deliberately contrary to what one expects”), or the use of analogy, comparing a complex situation or issue to a simple one in order to make it easier to understand (i.e., comparing a presidential election to a horse race).

Part Two: Analyzing Creative Components

The creative components refer to things about the cartoon that you cannot see in the image: the author, the purpose or agenda, the audience, the ideology, and the context. Looking at our example from above (“Southern Ideas of Liberty”), we can run through the creative components for our analysis:

Who was the author/artist? What did they do for a living? What were their political or social beliefs and associations? (i.e., were they a Whig or a Democrat? Abolitionist? Wealthy or working class?)

Purpose/Agenda

Was the piece created to help support or to speak out against a person, institution, or organization? Was it meant to make a logical argument or a more emotional appeal to the audience? What was the author’s agenda in creating the cartoon?

Who is the audience that this piece is targeting? What do you think is the gender, race, socioeconomic status, nationality, and education level of the target audience?

What basic ideals is the cartoon supporting or speaking out against? (i.e., freedom, independence, courage, self-reliance, immorality, dishonesty, greed)

Figure out where and when the cartoon was first published. What type of historical context was the cartoon printed in? What else was going on at the time that could have had an influence on the content of this particular cartoon or on its author or audience? Think about social, cultural, political, economic and military events, even natural disasters or climate events. All of these would have informed the context of the political cartoon you are analyzing.

Out of these five elements, the Purpose or Agenda and the Context are the most important for understanding political cartoons. The purpose or agenda of the cartoon is the most important because it shows what issues were important to people at the time of its creation. If you go to the Library of Congress website and select a decade on the left-hand menu, you can scroll through the cartoons and see which topics have the most material. This can be a good measure of which issues, people, or events were being frequently discussed during that time period.

Context is important because political cartoons are essentially a form of propaganda, which is a medium that is difficult to understand outside of its own time period. For example, many people in the modern era are required to read Virgil’s Iliad in school as an example of Classical literature, but few realize that it was actually written as a propaganda piece to boost the image of the Emperor. Nearly anyone who read the Iliad at the time it was written would be able to recognize it as propaganda because of the literary features, language, and subject matter. Context is sort of like an inside joke, where you “had to be there” to get it. Since we cannot be back in history, our context has to be taken from what we know about the time period from other sources.

Creative Components

You will now analyze the creative components of your own political cartoon which you chose in the activity above. Instead of doing an analysis of all five, you will focus only on the two most important ones mentioned in the paragraph above: Purpose/Agenda and Context .

Using the visual components of your cartoon as supporting evidence, write two brief paragraphs (3-5 sentences) describing the Purpose and Context of your cartoon. This is an open-ended exercise, but you can use the spaces below to jot down your ideas.

- HarpWeek, American Political Prints, 1766-1876. Retrieved June 15, 2021, from https://loc.harpweek.com/LCPoliticalCartoons/DisplayCartoonLarge.asp?MaxID=42&UniqueID=42&Year=1835&YearMark=1830 ↵

- Reading Political Cartoons. Authored by : Lillian Wills for Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Political Cartoon. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Political_cartoon . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- A Society of Patriotic Ladies at Edenton in North Carolina Interactive. Authored by : Dr. Christy Jo Snider. Located at : https://sites.berry.edu/csnider/resources/patriotic-ladies/ . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Southern Ideas of Liberty Political Cartoon. Provided by : Library of Congress. Located at : https://loc.harpweek.com/LCPoliticalCartoons/DisplayCartoonLarge.asp?MaxID=42&UniqueID=42&Year=1835&YearMark=1830 . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Home — Essay Samples — Arts & Culture — Visual Arts — Political Cartoon

Essays on Political Cartoon

The possibilities are virtually endless. Political cartoons are a rich source of material for analysis and commentary on a wide variety of issues, from current events to historical controversies. In this article, we'll explore some of the most compelling and relevant topics for political cartoon essays, and discuss how to choose a topic that will attract readers and engage them in meaningful discussion.

Criteria for choosing a topic

Before we dive into specific topics, it's important to understand what makes a good political cartoon essay topic. First and foremost, the topic should be current and relevant. Political cartoons are often a response to current events, so choosing a topic that is in the news or on people's minds is a good way to ensure that your essay will be timely and interesting. Additionally, the topic should be controversial or thought-provoking. Political cartoons are often designed to provoke a reaction, so choosing a topic that is contentious or divisive can provide a wealth of material for analysis and discussion.

Potential topics

With these criteria in mind, let's explore some potential topics for political cartoon essays. One of the most obvious and timely topics is the current state of politics. With the 2020 presidential election looming, there is no shortage of material for political cartoons. From the candidates themselves to the issues that are dominating the campaign trail, there is a wealth of material to analyze and discuss. For example, you could explore how political cartoons are depicting the candidates and their policies, or how they are commenting on the state of the country as a whole.

Another timely topic for political cartoon essays is the ongoing debate over climate change. With increasing concern over the environment and the impact of human activity on the planet, political cartoons have been a powerful tool for raising awareness and provoking discussion on this issue. You could explore how political cartoons are addressing the issue of climate change, and how they are contributing to the public discourse on this important topic.

In addition to current events, political cartoon essays can also delve into historical topics. For example, you could explore how political cartoons have addressed past events such as wars, social movements, or political scandals. By analyzing how these events were depicted in political cartoons, you can gain insight into how public opinion and discourse have evolved over time.

Approaching the analysis

Once you have identified a potential topic for your political cartoon essay, it's important to consider how to approach the analysis. A good approach is to start by examining a variety of political cartoons on the topic, and identifying common themes or messages. For example, if you are writing about climate change, you might look at how different cartoonists have depicted the issue, and identify recurring symbols or tropes. By doing this, you can gain a deeper understanding of the topic and identify key points for analysis in your essay.

In addition to analyzing the content of political cartoons, it can also be helpful to consider the context in which they were created. For example, you might consider the political climate at the time the cartoons were published, or the audience they were intended for. Understanding the context in which political cartoons were created can provide valuable insights into their meaning and impact.

When writing a political cartoon essay, it's also important to consider the visual elements of the cartoons themselves. Political cartoons often rely on visual symbols and metaphors to convey their message, so it's important to consider how these elements contribute to the overall meaning of the cartoon. For example, you might consider how the use of color, composition, or caricature contributes to the message of the cartoon.