Hansen's Disease (Leprosy)

CDC has not issued a travel advisory for Florida, or any other state, due to Hansen’s disease (leprosy).

Hansen’s disease, also known as leprosy, is very rare in the United States, with less than 200 cases reported per year. Most people with Hansen’s disease in the U.S. became infected in a country where it is more common. In the past, leprosy was feared as a highly contagious, devastating disease, but now we know that it’s hard to spread and it’s easily treatable.

- Hansen’s disease does not spread easily from person to person. You cannot get leprosy through casual contact such as shaking hands, sitting next to, or talking to someone who has the disease.

- Prolonged, close contact with someone with untreated Hansen’s disease over many months is needed to become infected. Around 95% of all people cannot become sick because they are naturally immune.

- Leprosy can be cured with antibiotic treatment. Once someone starts treatment for Hansen’s disease, they can no longer spread the disease to other people.

CDC and the National Hansen’s Disease Program (NHDP) are continuously monitoring for exposures of all reported cases.

Hansen’s disease (also known as leprosy) is an infection caused by slow-growing bacteria called Mycobacterium leprae . It can affect the nerves, skin, eyes, and lining of the nose (nasal mucosa). With early diagnosis and treatment, the disease can be cured. People with Hansen’s disease can continue to work and lead an active life during and after treatment.

Leprosy was once feared as a highly contagious and devastating disease, but now we know it doesn’t spread easily and treatment is very effective. However, if left untreated, the nerve damage can result in crippling of hands and feet, paralysis, and blindness.

Bust the Myths, Learn the Facts

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

International Textbook of Leprosy

Search form, clinical diagnosis of leprosy, contributing authors.

- Head, Training Department

- Schieffelin Institute of Health Research & Leprosy Centre

- Vellore, Tamil Nadu 632006, India

- Principal, College of Health Sciences

- Chitwan Medical College and Teaching Hospital (CMCTH)

- CMC Road, Bharatpur-10, Chitwan

- Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology

- Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER)

- Chandigarh, 160012

Kumar B, Uprety S, & Dogra S. (2017) Chapter 2.1. Clinical Diagnosis of Leprosy. In Scollard DM, & Gillis TP. (Eds.), International Textbook of Leprosy. American Leprosy Missions, Greenville, SC. https://doi.org/10.1489/itl.2.1

Introduction

Leprosy, which is caused by the Mycobacterium leprae (see Chapter 5.1 ), is a disease of low contagion that presents with protean manifestations. In its usual presentation, it is a chronic disease whose slow clinical progression is often punctuated by hypersensitivity reactions (lepra reactions; see Chapter 2.2 ). The disease ranges from a singular patch or single nerve thickening to the diffuse involvement of the skin, multiple nerves, and even the internal organs. The neurological involvement (see Chapter 2.5 ) in leprosy results in sensory-motor deficits leading to deformities and disability (see Chapter 4.1 ). These deformities lead to stigmatization (see Chapter 4.5 ) and the socioeconomic-emotional isolation of leprosy patients.

A lack of awareness about the signs and symptoms of the disease makes the diagnosis of leprosy very challenging, especially for practitioners in areas of low endemicity. In the UK, the clinical diagnosis of leprosy was not suspected in 80% or more of patients on their first visit, and the diagnostic delay averaged 1.8 years [1] . Hence, it is imperative to recognize, classify, and appropriately treat the disease to prevent complications that are more difficult to manage.

The clinical recognition of the subtle signs of leprosy is of great value in its diagnosis, as that recognition clinches the diagnosis in most of the cases. Laboratory tests (see Chapter 7.1 ) are often unavailable in highly endemic nations and polymerase chain reaction (PCR; see Chapter 7.2 ) is currently not adequately reliable. As a result, slit-skin smears (SSS) and histopathology (see Chapter 2.4 ) are simple but important investigative tools in the diagnosis of leprosy. The WHO expert committee on leprosy has defined a case of leprosy as an individual who has one of the following cardinal signs of leprosy but who has not received a full course of multi-drug therapy (MDT) for the type of leprosy identified [2] :

- A definite loss of sensation in a pale (hypopigmented) or reddish skin patch

- A thickened or enlarged peripheral nerve with a loss of sensation and/or weakness in the muscles supplied by the nerve

- The presence of acid-fast bacilli in an SSS

The diagnosis of leprosy is often complicated by what have been defined as the ‘spectral’ manifestations of the disease, which are due to the variability in the type and strength of the body’s immune response (see Chapter 6.2 ) to M. leprae . A strong cell-mediated immune response leads to a milder form of presentation, whereas a weaker cell-mediated immune response leads to a more severe form of the disease. This spectral presentation has resulted in the development of several classification systems for leprosy, two of the most important being the Ridley and Jopling classification (see Chapter 2.4 ) and the WHO classification.

In 1966, Ridley and Jopling [3] proposed a classification system for leprosy (shown in Table 1). This classification was developed for research purposes and is still used in clinical practice in many parts of the world, including the U.S. and most European countries. The Ridley-Jopling system classifies leprosy as an immune-mediated spectral disease with tuberculoid leprosy (TT) at one end of the spectrum and lepromatous leprosy (LL) at the other end. These two ends of the spectrum are considered to be clinically stable. Immunologically, strong cell-mediated immunity (CMI) correlates with the TT type and weak CMI correlates with the LL type of the disease. Between these two ends lies the clinically unstable borderline spectrum, which can be further subdivided into borderline tuberculoid (BT), mid-borderline (BB), and borderline lepromatous (BL), of which BB is the least stable. Leprosy as a disease frequently undergoes changes in clinical presentation depending on the immune status of the individual. If the disease is moving up the spectrum, i.e., towards TT, it is upgrading, and if the disease is moving down the spectrum, i.e., towards LL, it is downgrading. Hence, the Ridley-Jopling classification helps correlate the disease pathophysiology with the clinical features and describes leprosy as a spectral disease from a clinical, immunological, and histopathological perspective. The Ridley-Jopling classification, however, does not include the indeterminate and pure neuritic forms of leprosy.

The WHO classification system (1981), which is an operational classification system, was developed to simplify the institution of chemotherapy (Table 1). The WHO classifies leprosy as multibacillary (MB) or paucibacillary (PB) leprosy. This distinction was initially made on the basis of SSS positivity, in which patients with a bacillary index (BI; see Chapter 2.4 ) of more than 2 are treated as MB and the rest as PB. The BI is directly related to the bacterial load, and it denotes the total number of bacilli, regardless of their shape and staining (Table 2; see Chapter 2.4 ).

The current WHO classification of leprosy as MB or PB is simply based on the total number of leprosy lesions in a given individual. Initially, for feasibility and operational purposes, all of the patients who had SSS positivity were regarded as MB. However, when SSS was applied globally, quality control issues emerged. Hence, in 1998, SSS was omitted as a basis for the distinction between MB and PB leprosy.

The sensitivity and specificity of the WHO classification has been reported to be around 90% [4] . Nerve involvement is not part of the WHO’s clinical classification. In India, the number of nerves involved, along with the number of skin lesions, is taken into consideration in the classification of leprosy into PB and MB cases. This classification system was developed by the National Leprosy Eradication Program (NLEP) of the Government of India, the Global Alliance for Leprosy Elimination, and the WHO (Table 3) [5] . Single nerve involvement is labeled PB; more nerve involvement is labeled MB [5] .

Indian classification

The Indian classification was accepted and adopted in India in 1955 [6] . The aim of the Indian system was to include all levels of leprosy workers from grass-root workers to researchers. The Indian classification includes six groups: (i) tuberculoid, (ii) borderline, (iii) lepromatous, (iv) indeterminate, (v) pure neuritic, and (vi) maculoanesthetic. In 1981, the Indian classification was modified and accepted by the Indian Association of Leprologists (IAL) and the new five-group classification was named the New IAL classification of leprosy [7] . Maculoanesthetic leprosy was later removed from this classification.

Clinical Features of Leprosy

Detecting the clinical features of leprosy in a patient requires a meticulous approach. The presentation is subtle in many patients, especially in the indeterminate and tuberculoid portions of the spectrum. The patient should be fully exposed and observed under adequate lighting to detect the clinical signs of leprosy.

According to the Eighth Report of the WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy, leprosy should be suspected in people with any of the following symptoms and signs [2] :

- Pale or reddish patch(es) on the skin

- Loss, or decrease, of feeling in the skin patch(es)

- Numbness or tingling of hands, feet

- Painful or tender nerves

- Swelling of or nodules on the face or earlobes

- Painless wounds or burns on the hands or feet

The various clinical types of leprosy are described below.

Indeterminate leprosy (I)

The earliest clinical presentation in leprosy often is in the form of an ill-defined hypopigmented macule or patch, situated on the lateral / outer aspect of the thigh, face, and extensor aspect of the limbs. The color, however, may vary within the same individual or between individuals depending on skin type. In fair-skinned patients, the lesions may be erythematous, and in dark-skinned patients, they may be coppery brown. The body hair appears normal on these lesions, but the macule may be slightly dry as compared to the surrounding skin. This initial clinical presentation is known as indeterminate leprosy and is observed as the first sign of the disease in about 20–80% of the patients, often in the examination of family contacts of an index case. However, it is generally believed that the CMI response against M . leprae is not well developed in this early presentation.

There might be single or multiple lesions, no more than 3–4 cm wide, with a smooth surface that might occasionally have a slightly creased or wrinkled appearance. The larger lesions are fairly well defined, whereas the smaller lesions have an indefinite border that fades imperceptibly into the surrounding skin (Figure 1). The number of lesions depends on the CMI of the patient, which is genetically determined (see Chapter 8.1 ). Patients with a stronger CMI usually present with few skin lesions, have a strong tendency to self heal without treatment, and have a higher tendency to evolve towards the TT or BT forms of leprosy. Patients with a weaker CMI usually present with multiple skin lesions and, without treatment, they have a higher tendency to evolve towards the BB, BL, or LL forms of leprosy.

Sensory loss is unusual in indeterminate leprosy. However, patients commonly present with a loss of thermal sensation, i.e., an inability to differentiate between hot and cold water in a test tube. Hyperalgesia may often precede the detection of skin lesions. The slit-skin smear (SSS) is usually negative.

The absolute confirmation of the diagnosis of indeterminate leprosy is a demonstration of acid-fast bacilli in Fite-stained sections in a biopsy; perineurovascular infiltration (see Chapter 2.4 ) is highly suggestive. The histamine test is very useful in the diagnosis of indeterminate leprosy in fair-skinned individuals. The triphasic skin reaction known as the triple response of Lewis is not observed in the leprosy lesion. The triple response depends on the local response to histamine, which is in the form of erythema, wheal, and flare. For the response to completely manifest itself, the integrity of the sympathetic system should be well preserved, which is not true in the leprous lesion.

The common differentials (see Chapter 2.3 ) for lesions of indeterminate leprosy are pityriasis alba, a hypochromic variant of P. versicolor , early vitiligo, post inflammatory hypopigmentation, and a hypopigmented variant of polymorphic light eruption.

In our experience with the prognosis of indeterminate leprosy, three out of four indeterminate cases heal on their own and the rest become ‘determinate’ and enter the clinical spectrum of leprosy. However, when the clinical suspicion is doubtful and the histology is inconclusive, the patient should be kept under close supervision. There should be no hurry to label the patient as a case of leprosy, as the disease is often associated with severe social stigma. The key features of indeterminate leprosy are summarized in Table 4.

Tuberculoid Leprosy (TT)

Tuberculoid leprosy forms one end of the spectrum in the Ridley-Jopling classification. The CMI is high in patients with tuberculoid leprosy and the lepromin test is reactive. Due to the high CMI (see Chapter 6.2 ), lesions may heal on their own in the majority of patients [8] . The symptoms in TT might be cutaneous or neural or both.

Cutaneous lesions in TT do not number more than 3, are up to 10cm in diameter, and are well defined. The lesions are rarely very large. The lesions may occur on any part of the body, but often there is a predilection for exposed/uncovered areas of the body. The lesions are in the form of erythematous papules or plaques with a well-defined outer border (Figure 2A). Less commonly in early stages, clinical presentation is in the form a macular lesion. The macular lesions are hypopigmented but can also be erythematous. Erythema of the lesion may not be well appreciated in dark skinned individuals in whom the lesions may appear to have coppery hue. The lesions are hypopigmented and never depigmented, having dry mild scaly surface and well defined borders (Figure 2B). They may have papular lesions on the outer edges [9] , [10] . Plaques often show central flattening or clearing, which gives the lesion annular morphology. In case of such presentations, the border slopes towards the inner margin and is abrupt on the outer margin. These characteristics are due to the central clearance and peripheral spread of the disease activity [10] . Often, there is an enlarged nerve at the border of the macule or plaque. Light palpation around the border of the lesion helps to detect this subtle clinical sign, which may otherwise be missed.

Neural involvement in TT is uncommon and usually occurs as a result of the extension of the infection through cutaneous superficial branches. Hence, the nerve involvement is usually patchy, unilateral, and asymmetrical. The neural symptoms can present as pain, sensory loss, tingling, and muscle weakness or paralysis. Nerve pain may be the first presentation of TT [11] . Very rarely, TT may present solely as anesthetic areas without changes of skin color or peripheral nerve enlargement [11] .

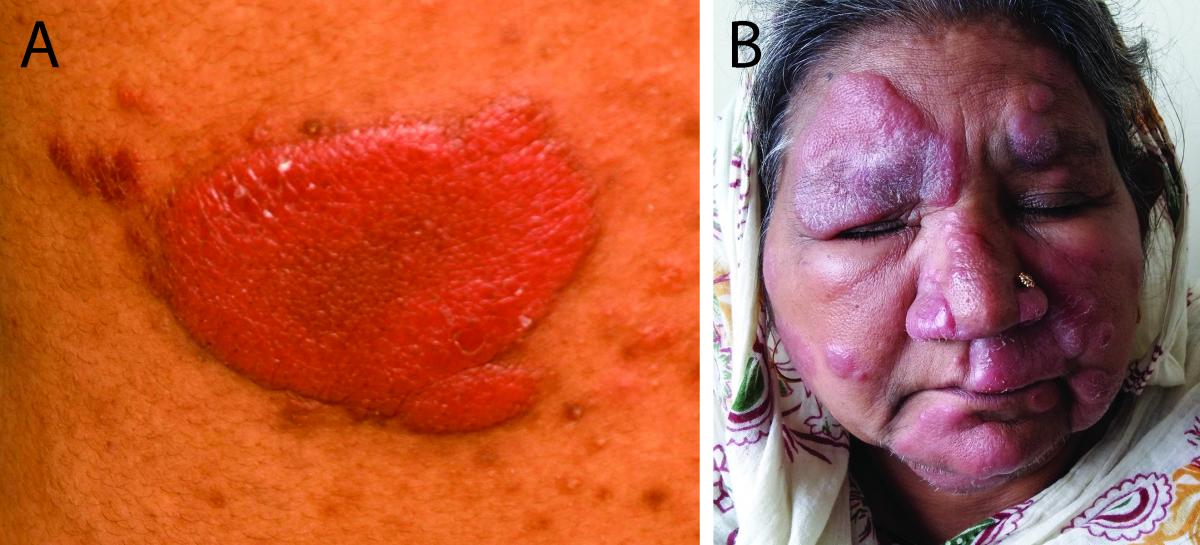

FIG 2A TT leprosy, with well-defined, erythematous, hairless, dry, anesthetic plaque.

FIG 2B Maculoanesthetic BT leprosy, hypopigmented, hypoesthetic, dry patch with loss of appendages.

The lesion is often completely anesthetic. First the temperature sensitivity is lost, followed by pain and finally the loss of tactile sensitivity. On the face, the sensory impairment is difficult to demonstrate because of the rich sensory innervations that may compensate for the damaged nerves. In an individual lesion, the sensory loss is more marked in the center than in the periphery. Due to the involvement of autonomic nerves, the surface is dry and sweating is lost. Well-organized epithelioid granulomas are characteristic histopathologic findings (see Chapter 2.4 ) in a skin biopsy of the lesion, but acid-fast organisms are difficult to demonstrate in Fite-stained sections and skin smears are usually negative. The lesions are often dry to the touch, and the lesions may be devoid of hair [9] .

There might be nodular swellings along the course of thickened nerves (see Chapter 2.3 ), which may be caused by localized nerve abscesses. The nerve abscess formation is more common in the tuberculoid portion of the leprosy spectrum. The type of abscess seen in TT is a ‘cold abscess’ with scanty lepra bacilli, whereas in the rest of the spectrum the abscess is of the inflammatory type with a large number of inflammatory cells and plenty of degenerating bacilli [12] . The nerve abscess may be present in the nerve trunk and can occasionally be very large in size, mimicking a tumor. The nerve abscess may find its way out of the sheath and produce swelling beside the nerve. It might also rupture through the skin, producing a discharging sinus. Eventually, the abscess may calcify and the calcification can spread over long stretches of the nerve, which can be detected by X-rays [12] .

The common differentials (see Chapter 2.3 ) of tuberculoid leprosy are often the lesions which show annular morphology such as tinea, subacute lupus erythematosus (SCLE), annular sarcoid, syphilis, and a herald patch of pityriasis rosea. Clinical examination and histopathology secure the diagnosis. The sweat test demonstrates anhidrosis and the complete triple response is not seen in the histamine test [13] .

The prognosis is good, as a TT lesion can even self-heal. However, nerve damage-related disability can occur. The key features of TT are summarized in Table 5.

Borderline Leprosy

Globally, the borderline form contributes the majority of the disease burden due to leprosy. Immunologically, the disease is unstable and may either upgrade to the tuberculoid portion of the spectrum with treatment, or downgrade to the lepromatous portion of the spectrum if untreated. The CMI in BL ranges between the tuberculoid and lepromatous poles. This immunological instability is reflected in the variability of clinical features seen in this spectrum. This immunological instability increases the tendency to develop lepra reactions (see Chapter 2.2 ) and 30% of the patients with BL are at risk of developing type I reactions (Figures 3A, 3B) [9] . This risk translates to a higher chance of developing crippling deformities in the borderline cases.

FIG 3 BT leprosy in reaction.

- BT leprosy in reaction. Erythematous, indurated, succulent, shiny plaque. Note the finger like projection (pseudopodia) and satellite lesions.

- BT leprosy in reaction (face) showing downgrading to BL. Multiple succulent erythematous, edematous, shiny plaques can be observed.

The skin lesions also vary in numbers and morphology as we move from BT to the BL type of the disease. Skin lesions in BT are clinically closer to skin lesions in TT, and the lesions in BL are closer to those in LL. Skin lesions are fewer in number, asymmetrical, better defined, dry, and less shiny and smooth, with an absence of appendages in the BT spectrum. As the disease downgrades, skin lesions become more numerous and ill-defined and are shiny in appearance. Loss of appendages is prominent higher up in the BT spectrum. However, the loss of sensation in BT is never as severe as that seen in TT. The loss of sensation in the limbs tends to become more symmetrical in the extremities if the disease progresses from BT to BL.

The involvement of the nerves is prominent in borderline lesions. The nerve involvement is asymmetrical and seen in fewer nerves in BT lesions. With numerous nerves involved, the nerve involvement becomes more symmetrical towards the BL portion of the spectrum. The borderline portion of the disease spectrum is extremely unstable and can move towards any pole. But, when left untreated, the disease has a tendency to deteriorate and move towards the lepromatous end of the spectrum [13] . The key features of BL are summarized in Table 5.

Borderline tuberculoid (BT)

Lesions in BT often resemble those in TT, but are more numerous, larger in size, and less well defined. Unlike TT, where the outer margin is well defined, lesions in BT have an outer margin that at places slopes towards the surrounding skin. BT lesions are characterized by ‘finger like’ extensions, known as pseudopodia. There may be satellite lesions surrounding the plaque (Figure 3A). The lesions are often dry, scaly, hypoesthetic plaques with a loss of appendages and decreased sweating (Figures 3C–3F); however, these features are not as prominent as those seen in TT. In the maculoanesthetic presentation of BT, there are pale macules with decreased sensation, mostly on the face, lateral aspect of extremities, buttocks, and scapulae. These are large and asymmetrical hypopigmented lesions with well-defined edges and a dry surface with decreased sweating [14] .

The nerves are asymmetrically and irregularly thickened in BT leprosy. The patient may present with anesthesia and motor deficits. The nerves are severely involved in episodes of reaction in BT [14] . During a reaction episode, the nerve function may deteriorate rapidly and the patient may present for the first time because of the nerve function impairment. In the absence of prompt treatment, this reaction might lead to paralysis, followed by deformity and disability (Figure 3G).

FIG 3 BT leprosy.

- BT leprosy. Hypopigmented, hypoesthetic, dry plaque with well-defined outer border and loss of appendages. Enlarged greater auricular nerve can be observed on the neck.

- BT leprosy on the leg. Hypopigmented to coppery brown, hypoesthetic, dry patch with decreased hair density.

- BT Leprosy on nape of neck – large, hypigmented to erythematous plaque with central clearing and elevated borders. Xerosis, wrinkling, and loss of hair can be seen.

- BT leprosy on the nape of neck. Erythematous, well-defined, dry plaque with well-defined outer border and loss of appendages. Satellite lesions can be observed surrounding the large plaque.

- BT leprosy in type 1 reaction presenting with ulnar nerve abscess and subsequent deformity in the form of ulnar clawing.

Fite staining for AFB is often positive and the BI ranges between 0 and 2+ in skin smears.

Borderline borderline (BB)

BB is the most immunologically unstable portion of the borderline spectrum [9] . Patients quickly move either towards the lepromatous or the tuberculoid poles. Dimorphous lesions, i.e., lesions characteristic of both the tuberculoid and lepromatous types, are seen in this part of the spectrum. Skin lesions, which are in the form of infiltrated papules, plaques, and even nodules at times, tend to be symmetric. The characteristic lesion of BB leprosy is an annular plaque with a well-demarcated ‘punched-out’ inner margin and a sloping outer margin, giving a ‘swiss cheese’ appearance (Figures 4A, 4B).

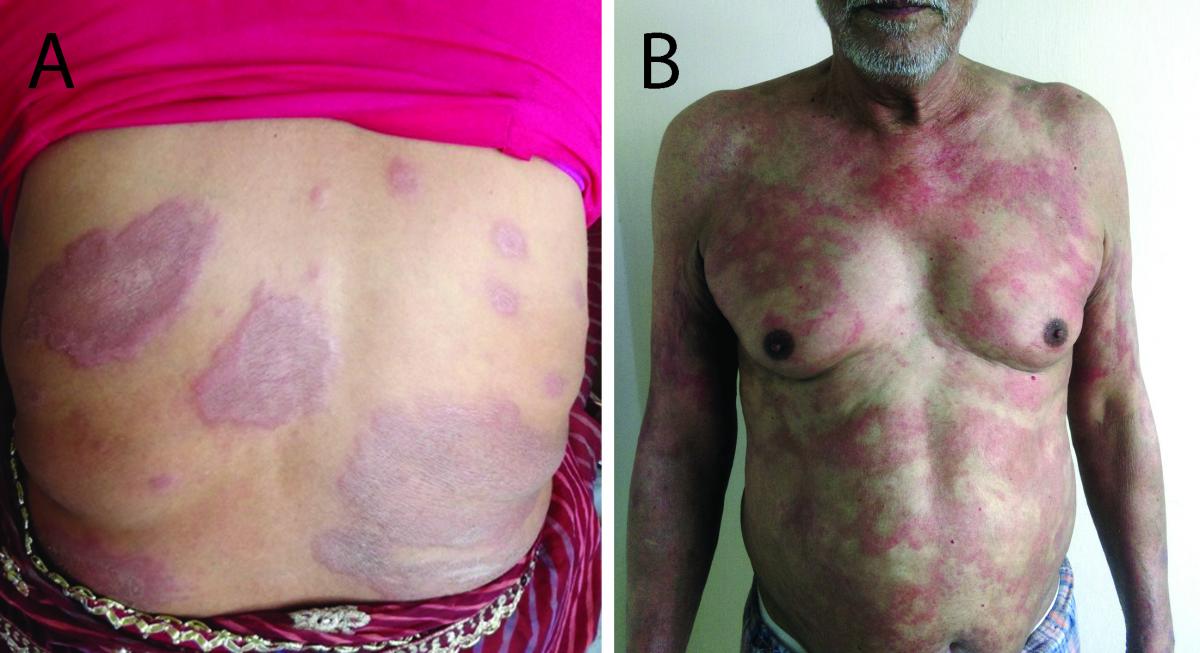

FIG 4 BB leprosy.

- BB leprosy. Multiple erythematous, dry plaques, some of them show the hallmark annular morphology with a ‘punched out’ inner edge giving the ‘Swiss cheese’ appearance. Note the presence of well-defined plaque reminiscent of the Tuberculoid spectrum, suggesting downgrading.

- BB leprosy. Multiple, symmetrically distributed erythematous, ill-defined annular plaques with some of the plaques showing a ‘punched out’ inner margin.

The nerve involvement is variable in BB. If downgrading from BT, there may be asymmetrical nerve thickening, and if upgrading from BL, the nerve thickening may be more symmetrical. Nerve involvement may be severe in the case of type 1 reactions. On histopathology, the Fite stain for AFB is positive. On microscopy, BI on SSS usually ranges between 2+ and 4+ [15] .

Borderline Lepromatous (BL)

Lesions in BL are multiple and there is an increased tendency for symmetry. Lesions often begin as hypopigmented to coppery-hued macules that are multiple in number, more symmetrical in distribution, and smaller in size and that have indistinct borders that merge into the intervening normal skin [16] . A decrease in appendages and sweating, which are features of the disease in the BT and TT spectrums, are not prominently seen in BL. With time, the macules undergo induration/infiltration beginning from the center and forming plaques and nodules. Often the lesions in BL have downgraded from the higher spectrum, which is evident due to the presence of lesions of variable morphology and large size (Figures 5A, 5B).

FIG 5 BL leprosy.

- BL leprosy downgraded from BT. Multiple well-defined dry plaques with decreased appendages. Lesions show symmetry in their distribution.

- BL leprosy. Multiple ill-defined, but distinct erythematous maculo-plaque lesions with a tendency to symmetry in their distribution.

In BL, the peripheral nerve trunks are thickened and tend to be symmetrical. The nerve damage is not as severe as that seen in BT, and the corresponding anesthesia and paresis is usually not seen in the early stages of the disease. Symmetrical anesthesia involving hands and feet is seen later in the course of the disease. Severe nerve deficits can occur in the case of reactional episodes.

Patients may manifest with type 1 reactions (reversal reaction; see Chapter 2.2 ) after starting treatment (Figures 5C, 5D). Type 2 reactions (see Chapter 2.2 ) or erythema nodosum leprosum affect about 10% of patients in BL. The lepromin reaction is almost always negative. Fite staining for AFB is strongly positive and BI can reach 6+ with globi [15] .

- BL leprosy in type 1 reaction. The pre-existing lesions appear as erythematous, indurated, shiny lesions.

- BL leprosy in type 1 reaction. The pre-existing lesions appear as erythematous, indurated, shiny lesions. Crops of new lesions appear on previously un-involved skin. The face appears edematous.

Lepromatous Leprosy (LL)

The CMI is severely impaired in LL. This impairment results in the uncontrolled multiplication and dissemination of lepra bacilli. LL can appear de novo due to the highly anergic state of the individual or may downgrade from the BT or BL spectrum in the absence of treatment. LL with a de novo appearance is called polar lepromatous leprosy (LLp), and when a result of downgrading, it is called subpolar lepromatous leprosy (LLs) [14] . The subpolar group can regain its lost CMI and upgrade in the spectrum [17] . Fite stains reveal large numbers of acid-fast bacilli and globi. Also, bacteriologically, the subpolar group clears earlier than the polar group after therapy.

The cutaneous lesions of LL are multiple with bilateral symmetrical distribution over the arms, legs, buttocks, face, and trunk. Warm areas of the body such as the axillae, groin, perineum, and hairy scalp of the body are relatively spared, as lepra bacilli favor the cooler areas of the body. Often these areas of the body have been described as ‘immune zones’ in leprosy. But the sparing of these areas has nothing to do with immunity per se and simply occurs due to the temperature preference of lepra bacilli. Clinically, the LL disease may present with any of the stages described below or with a mix of these lesions.

Early macular stage

During the initial phase of presentation, lesions are often in the form of many macules. In light-colored individuals, the macules are slightly erythematous, and in darker individuals, the macules may be hypopigmented to mildly erythematous with a coppery hue. These macules are indistinct and coalesce with one another; they have indistinct borders and merge inconspicuously in the surrounding skin. There is little difference in texture between these macules and the surrounding normal skin; however, they have a shiny appearance and exhibit the impairment of sweating. There is no loss of sensations and the skin appendages are almost normal. (Note that the macules seen in BT lesions are anesthetic, have dry texture, and exhibit an absence of appendages and a lack of sweating.)

Infiltrated stage

In due course, if left untreated, the macular lesions progress to develop induration. Due to minimal infiltration and a shiny appearance, the lesions are often better visualized in oblique lighting. The minimal infiltration of these lesions is better appreciated by pinching the lesions rather than by simple inspection/palpation of the lesions. The infiltration is more marked on the face and the ear lobules. The infiltration of the ear lobules is better seen by standing behind the patient (Figures 6A, 6B).

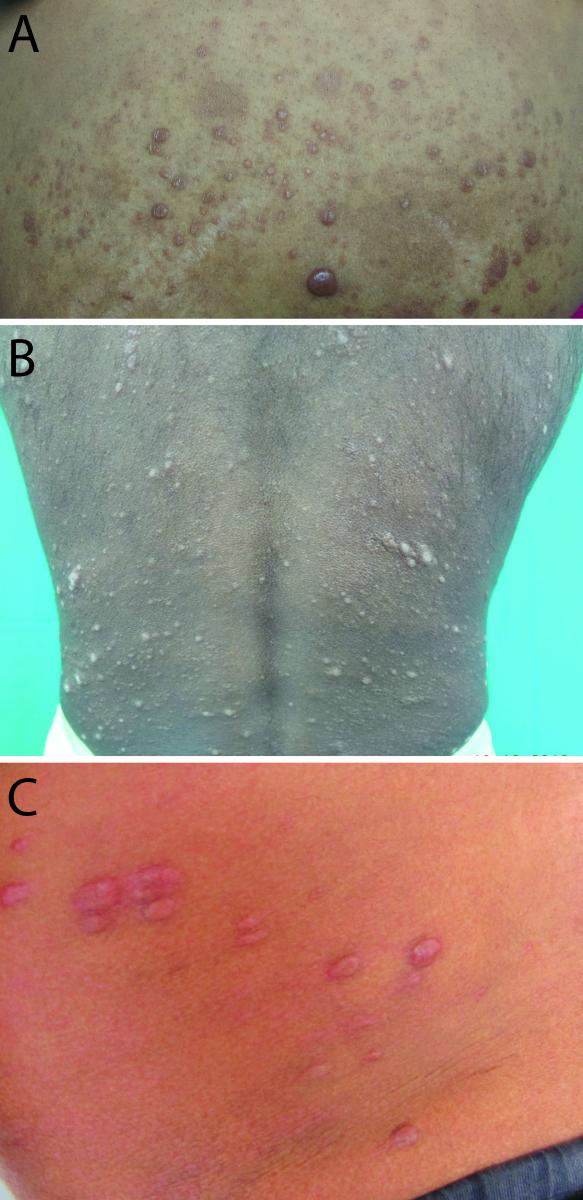

FIG 6 LL leprosy.

- LL leprosy. Diffuse infiltration of the face. Slit-skin smear was highly positive.

- LL leprosy. Thickening, infiltration and nodulation of the ear.

Late nodulo-plaque stage

If left untreated, the infiltration increases and the macules progress to form papules, nodules, and even plaques. Even with increasing infiltration, the characteristics of the lesions remain essentially the same, i.e., they have ill-defined outer borders that merge into the surrounding skin. The nodules make their first appearance on the ear lobes and, as the disease spreads, appear anywhere on the body. They are commonly seen over the buttocks and extremities, especially over the elbows, fingers, joints, and genitals. These nodules, and occasionally the areas of thick induration, may break down to produce ulcers, especially during episodes of type 2 reaction (Figure 6C) [12] . These repeated episodes of ulceration and healing, when the ear cartilage is involved, lead to what has been described as the ‘rat-bitten’ appearance of the ears. These ulcers are rich in lepra bacilli and the patient is highly infectious. The ulcers are more commonly found in the nose, mouth, and throat (see Chapter 2.4 ) due to the breaking down of the mucous membranes. Involvement of the nose results in nasal stuffiness, crusting, and epistaxis. A history of epistaxis is often an early pointer for LL but has to be specifically sought in the patient’s history. The involvement of the upper respiratory tract is seen in about 80% of patients. Progressive induration, thickening, and nodulation of the face accentuate the skin folds, producing classic ‘leonine facies’. The nodules are initially movable over the underlying subcutaneous tissue, but later they become fixed.

An untreated patient with LL has leonine facies, thickening and nodulations of ear lobes, and a broad and swollen nose, which may be a collapsed thinning of eyebrows (superciliary madarosis) and eyelashes (ciliary madarosis), and may have characteristic facies leprosa (Figure 6D). ‘Facies leprosa’ is characterized by the resorption of the nasal bone, anterior nasal spine, supra-incisive alveolar region, and anterior alveolar process of the maxilla, with associated sensory or motor damage depending on the type of nerve(s) involved.

- LL leprosy in type 2 reaction. There are multiple erythematous nodules on the face showing central necrosis.

- LL leprosy. The bridge of the nose is collapsed and the eyebrows are lost.

Early in LL progression there may be no nerve thickening, in contrast to the BT or TT types, where nerve thickening is predominant even early in the course of the disease. If patients are diagnosed and treated early, they may have no residual nerve thickening, but the same may not be true of the nerve deficit. The peripheral nerves (see Chapter 2.5 ) are the first to be affected, and they become firm, hard, and eventually fibrotic at the sites of predilection, i.e., where the nerves are closer to the surface (ulnar groove, radial groove, neck of fibula, and radial styloid). The well known ‘glove and stocking’ anesthesia is a late manifestation of LL. With time, the peripheral anesthesia becomes extensive and there is almost complete anhidrosis of the limbs. The dry skin appears ichthyotic, which may be further worsened by clofazimine administered as part of MDT (Figure 6E). Before the development of frank anesthesia, the digits may appear to have fusiform swelling and are hypersensitive to even minor stimuli or trauma. The patient often experiences severe neuralgic pain, even at the slightest touch. This sensitivity is followed by frank anesthesia, which is bilaterally symmetrical, although it may develop earlier in one limb than the other. The anesthesia may be patchy at first. Testing for anesthesia should be performed for pain, temperature, and light touch using a pin, hot and cold water, and a wisp of cotton. Sensory examination of leprosy patients should be done for all three components, as there might be a loss of only one aspect (dissociated anesthesia). Thermal sensation is the first to be affected, followed by touch and then pain. This outcome is of grave consequence because the patient, now unable to perceive sensations, has repetitive traumatic ulcerations that are slow to heal. This insensitivity leads to chronic non-healing ulcers and resorption of the fingers and toes. Also, trophic ulcers develop at pressure-bearing sites. There might be a secondary infection of these ulcers, which may further lead to cellulitis or osteomyelitis.

- LL leprosy. Severe, dry, plate-like ichthyotic scales observed on the lower legs in an LL patient on treatment. The ichthyosis in leprosy may be attributed to the disease itself or the clofazimine therapy, secondarily to the settling of pedal edema and nutritional deficiency.

Damage to the motor neurons leads to muscle weakness, wasting, and paralysis. The damage also results in classic deformities, such as the claw hand deformity (due to the involvement of the median and ulnar nerves), ape thumb deformity (due to the involvement of the median nerve), wrist drop (due to the involvement of the radial nerve), foot drop (due to the involvement of the lateral popliteal nerve), and facial palsy (facial nerve palsy).

As a result of hematogenous dissemination, LL can affect several organ systems apart from the skin, including the eyes, bones, oral cavity, testes, reticulo-endothelial system, muscles, and bones. They can be affected directly by LL or secondarily in reaction episodes.

The prognosis of LL in the absence of treatment is poor. The disease progressively worsens and affects the entire body. The patient is left with many non-healing ulcers and several deformities. Even with the institution of treatment, remission is often punctuated by several episodes of type 2 reactions. Death from leprosy is mainly due to superadded infections, severe and recurrent type 2 reactions, amyloidosis, and renal failure. The key features of LL are summarized in Table 5.

Rare Variants of Leprosy

Histoid leprosy.

Histoid leprosy was first described by Wade in 1960. The term was coined after the classic histopathological appearance of histoid lesions, which have histiocytes that form interlacing bands, curlicules, and whorls. Histoid leprosy was initially reported to manifest after the failure of long-term dapsone mono-therapy, irregular therapy, or inadequate therapy. However, it is now well known that histoid leprosy develops de-novo as well [18] , [19] . Histoid leprosy is considered by some to be a subtype of lepromatous leprosy, whereas others consider it to be an independent type [18] . It is characterized by a very high lesional bacillary load but with a relative absence of globi. The CMI and humoral immunity are probably higher than those found in LL. There is an increased expression of CD36 by the keratinocytes, and increased CD4 cells and B cells surround the histoid granuloma [19] . This increase in inflammatory cells surrounding the granuloma may explain the containment of most of the lepra bacilli to the lesional skin in histoid leprosy [19] .

Clinically, the lesions appear as firm, erythematous, shiny, smooth, hemispheric, round to oval non-tender nodules on the background of normal skin located on the face, back, buttocks, and extremities as well as over bony prominences. When localized on the face, they have a characteristic centrofacial distribution. Occasionally, the lesions may appear pedunculated or ulcerated [20] . The nodules may be superficially or deeply placed on the skin, or subcutaneous. Lesions may manifest as plaques and pads that are well defined and scaly, especially around pressure points such as elbows (Figures 7A–7C). Rare presentations include xanthomatous lesions, umbilicated nodules resembling molluscum contagiosum, and scrotal sinus [20] . Two types of histoid facies can be seen. In one subgroup, the facies resembles that of LL, in which patients have an old, wrinkled, atrophic face with scanty eyebrows and depressed nasal changes with scant histoid lesions on face. In the next subgroup, patients have histoid lesions on apparently normal skin with no nasal or ocular changes.

FIG 7 Histoid leprosy.

- Histoid leprosy. Nodules and noduloplaque lesions; some of the lesions show central umibilication.

- Histoid leprosy. Multiple nodules and noduloplaque lesions distributed on normal-appearing skin on back.

- Histoid leprosy. Multiple well-defined, dome-shaped, hemispherical nodules on normal-appearing skin.

Reaction episodes are considered to be uncommon in histoid leprosy; however, episodes of ENL have been observed [20] .

The differential diagnosis (see Chapter 2.3 ) includes progressive nodular histiocytosis, conventional leprosy nodules, molluscum contagiosum, and neurofibromas. The histoid lesions show a high BI and have a typical histopathological appearance.

Pure Neuritic Leprosy (PNL)

PNL is a variant of leprosy characterized by the isolated involvement of peripheral nerve trunks in the absence of skin lesions. This form of leprosy is more common in Nepal, Brazil and India [18] , [19] , [21] , [22] . Seven percent (7%) of total leprosy cases in Nepal and 4.3% of total leprosy cases in India are diagnosed as PNL [18] , [19] , [22] . The clinical features of this variant of leprosy include nerve thickening, pain, tenderness, and sensory-motor impairment. Sensory neuropathy is more predominant in PNL, with a loss of heat and pain sensitivities [23] . Occasionally, PNL may present with nerve abscesses. Mononeuritis is the most common presentation and is asymmetric in nature [19] , [23] , [24] . Nerve trunks in the upper limb are more commonly involved [19] . The nerve trunks commonly involved are the ulnar nerve, superficial radial nerve, sural nerve, common peroneal nerve, and posterior tibial nerve. PNL can have a spectral presentation ranging from TT to LL. Clinically, PNL is likely to be TT if only one or two nerve trunks are thickened and borderline if there are several thickened nerves.

The diagnosis of PNL is clinched by histopathological, bacteriological, and immunological evaluation. In difficult situations, a nerve biopsy serves as the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of PNL [25] . However, the nerve biopsy needs to be approached with caution.

Lucio’s leprosy

A diffuse form of polar LL, now known as diffuse leprosy of Lucio and Latapi (LuLp), was first described by Lucio and Alvardo in 1852 and further elaborated by Latapi and Zamora in 1948. It is common in Mexico (23% of leprosy cases) and Costa Rica, but very rare in other countries. However, it has been reported in Argentina, Brazil, and India. This form of leprosy has been associated with both M. leprae and a newly described organism in the M. leprae complex, Mycobacterium lepromatosis [26] , [27] .

LuLp is characterized by a diffuse infiltration of the skin, which in the initial period might go unnoticed. There is diffuse infiltration of the face and hands that may mimic a “myxedema”-like appearance, often giving the impression of a “moon face” or “healthy look”, and imaginatively called Lepra bonita (beautiful leprosy). The skin of the extremities may appear edematous, is smooth and devoid of hair, and may have violaceous erythema, especially on the hands and feet. As the disease progresses, the infiltration persists but the skin becomes thinner and atrophic and, consequently, the patient appears to have prematurely aged. The lower limbs appear xerotic and have ichthyosiform changes; the earlobes become saggy and stretched; and the face and trunk often have telangiectasia with a rosacea-like appearance. Hair loss is observed and involves the eyebrows, eyelashes, and body hair. Occasionally, the scalp may be involved, in which case the hair loss may mimic alopecia areata.

Nasal mucosa is involved insidiously with an initial congestive phase in which the mucosa is swollen with numerous telangiectasia. This phase is followed by the formation of microsanguineous crusts. In an advanced stage, the symptoms are similar to those observed in LL, with nasal obstruction and epistaxis followed finally by the ulceration of the septum, leading to a deformed ‘saddle-nose’ appearance. The involvement of the larynx is rare and may present as dysphonia and rarely as a respiratory obstruction.

Pan-neuritis is observed and somehow the equilibrium of muscles is preserved due to which “claw hand” deformity is usually not seen, even though there is atrophy of the lumbricals and the interosseus muscles [28] . Due to pan-neuritis, there is generalized hypoesthesia and hypohidrosis. In advanced stage there can be systemic involvement, with infiltrations of the spleen and liver leading to hepatosplenomegaly. Ocular involvement can occur and often there is madarosis with exaggerated shining of the eyes, known as “children eyes” [28] .

A peculiar phenomenon that characterizes LuLp is the lucio phenomenon (see Chapter 2.2 ). It is often the onset of lucio phenomenon that unmasks lucio leprosy. Lucio phenomenon is akin to Type 2 lepra reaction and is characterized by well-defined, angular, jagged, purpuric lesions evolving into ulcerations and spreading in ascending fashion and healing with atrophic white scarring.

Leprosy is a disease that has spectral presentation; it is also a great mimicker. Some points to consider when making a diagnosis of leprosy are the following:

- An ill-defined, normo-anesthetic, hypopigmented to erythematous patch situated on the face or the outer aspect of arms and legs may often be the presenting feature of indeterminate leprosy.

- Leprosy lesions are characterized by macules, papules, and plaques that are hypopigmented to erythematous, often hypo-anesthetic, dry lesions with scanty hair.

- As the lesions progress from the Tuberculoid to the Lepromatous spectrum, they become more numerous in number and gain symmetry in distribution.

- Patients suspected of having leprosy should always be fully exposed and examined in a well-lit room.

- A nerve examination is an integral part of assessing patients with leprosy and should never be skipped. Nerves should be examined for their thickness and tenderness, and a sensory examination of cutaneous lesions has to be performed.

- The pure neuritic variant of leprosy can present with isolated neural involvement in the absence of cutaneous involvement.

- Histoid leprosy is a rare variant of leprosy presenting as erythematous, non-tender, hemispherical or pedunculated nodules, which can be mistaken for nodular histiocytosis, molluscum contagiosum, xanthoma, or neurofibroma.

- Lucio leprosy is another rare variant of leprosy caused by Mycobacterium lepromatous , which is characterized by the diffuse infiltration of the skin that can often be mistaken for myxedema.

- ^ Lockwood DN, Reid AJ. 2001. The diagnosis of leprosy is delayed in the United Kingdom. QJM 94: 207–212.

- a , b WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy. 2012. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy: eighth report. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- ^ Ridley DS, Jopling WH. 1966. Classification of leprosy according to immunity. A five-group system. Int J Lepr Mycobact Dis 34: 255–273.

- ^ Croft RP, Smith WCS, Nicholls P, Richardus JH. 1998. Sensitivity and specificity of methods of classification of leprosy without use of skin-smear examination. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis 66: 445–450.

- a , b WHO Leprosy Elimination Group (WHO). 2000. Guide to eliminate leprosy as a public health problem [Internet]. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved 5 May 2015 from http://www.who.int/lep/resources/Guide_Int_E.pdf

- ^ National Leprosy Eradication Program (NLEP). 2013. Training manual for medical officer [Internet]. Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, New Delhi, India. Retrieved 5 May 2014 from http://clinicalestablishments.nic.in/WriteReadData/50.pdf

- ^ All India Leprosy Workers Conference. 1955. Classification of leprosy adopted by the Indian Association of Leprologists. Lepr India 27: 93–95.

- ^ Indian Association of Leprologists. 1982. Clinical, Histopathological and immunological features of the five type classification approved by the Indian Association of Leprologists. Lepr India 54: 22–32.

- a , b , c , d Walker SL, Lockwood DNJ. 2006. The clinical and immunological features of leprosy. Br Med Bull 77–78: 103–121.

- a , b Pfaltzgraff RE, Bryceson ADM. 1985. A clinical leprosy, p 134–176. In Hastings RC (ed), Leprosy. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, Scotland.

- a , b Pereira Junior AC, Do Nascimento LV. 1982. Indeterminate Hansen’s disease. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am 10: 159–164.

- a , b , c Languillon J. 1986. Clinical and developmental aspects of tuberculoid leprosy. Acta Leprol 4: 197–199.

- a , b Dharmendra. 1978. Leprosy Vol I, p 52–59. Kothari Medical Publishing House, Bombay.

- a , b , c Talhari C, Talhari S, Penna GO. 2015. Clinical aspects of leprosy. Clin Dermatol 33: 26–37.

- a , b Sehgal VN. 1987. Reactions in leprosy. Clinical aspects. Int J Dermatol 26: 278–285.

- ^ Sehgal VN, Joginder. 1990. Slit-skin smear in leprosy. Int J Dermatol 29: 9–16.

- ^ Ramos-e-Silva M, Rebello PF. 2001. Leprosy. Recognition and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol 2: 203–211.

- a , b , c , d Kaur I, Dogra S, De D, Saikia UN. 2009. Histoid leprosy: a retrospective study of 40 cases from India. Br J Dermatol 160: 305–310.

- a , b , c , d , e , f , g Nair SP, Kumar GN. 2013. Tropical medicine rounds: a clinical and histopathological study of histoid leprosy. Int J Dermatol 52: 580–586.

- a , b , c Rollier R, Rollier B. 1986. Clinical and developmental aspects of lepromatous leprosy. Acta Leprol 4: 193–195.

- ^ Dharmendra. 1978. Leprosy Vol I, p 61–65. Kothari Medical Publishing House, Bombay.

- a , b Kar BR, Job CK. 2005. Reversal reaction and Mitsuda conversion in polar lepromatous leprosy: a case report. Lepr Rev 76: 258–262.

- a , b Noordeen SK. 1972. Epidemiology of polyneuritic type of leprosy. Lepr India 44: 90–96.

- ^ Dongre VV, Ganapati R, Chulawala RG. 1976. A study of mono-neuritic lesions in a leprosy clinic. Lepr India 48: 132–137.

- ^ Kumar B, Kaur I, Dogra S, Kumaran MS. 2004. Pure neuritic leprosy in India: an appraisal. Int J Lepr Mycobact Dis 72: 284–290.

- ^ Han XY, Seo YH, Sizer KC, Schoberle T, May GS, Spencer JS, Li W, Nair RG. 2008. A new Mycobacterium species causing diffuse lepromatous leprosy. Am J Clin Pathol 130: 856–864.

- ^ Scollard DM. 2016 Sep 7. Infection with Mycobacterium lepromatosis . Am J Trop Med Hyg 95 (3):500–501.

- a , b Jurado F, Rodriguez O, Novales J, Navarrete G, Rodriguez M. 2015. Lucio’s leprosy: a clinical and therapeutic challenge. Clin Dermatol 33: 66–78.

- Printer-friendly version

- PDF version

Got any suggestions?

We want to hear from you! Send us a message and help improve Slidesgo

Top searches

Trending searches

suicide prevention

8 templates

46 templates

tropical rainforest

29 templates

spring season

34 templates

american football

16 templates

32 templates

World Leprosy Day

World leprosy day presentation, free google slides theme and powerpoint template.

Get creative with this new template we're releasing today and raise awareness about Hansen's disease, also called leprosy. It's one of the oldest diseases known by humans and there are treatments that can cure it, but it's still a serious disease with catastrophic consequences for the affected. We have used some illustrations, some wavy shapes on the backgrounds and other abstract elements that are slightly influenced by the Memphis graphic style. Prepare a slideshow for World Leprosy Day!

Features of this template

- 100% editable and easy to modify

- 35 different slides to impress your audience

- Contains easy-to-edit graphics such as graphs, maps, tables, timelines and mockups

- Includes 500+ icons and Flaticon’s extension for customizing your slides

- Designed to be used in Google Slides and Microsoft PowerPoint

- 16:9 widescreen format suitable for all types of screens

- Includes information about fonts, colors, and credits of the resources used

How can I use the template?

Am I free to use the templates?

How to attribute?

Attribution required If you are a free user, you must attribute Slidesgo by keeping the slide where the credits appear. How to attribute?

Related posts on our blog.

How to Add, Duplicate, Move, Delete or Hide Slides in Google Slides

How to Change Layouts in PowerPoint

How to Change the Slide Size in Google Slides

Related presentations.

Premium template

Unlock this template and gain unlimited access

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis

- v.2012; 2012

Leprosy: An Overview of Pathophysiology

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease, is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae , a microorganism that has a predilection for the skin and nerves. The disease is clinically characterized by one or more of the three cardinal signs: hypopigmented or erythematous skin patches with definite loss of sensation, thickened peripheral nerves, and acid-fast bacilli detected on skin smears or biopsy material. M. leprae primarily infects Schwann cells in the peripheral nerves leading to nerve damage and the development of disabilities. Despite reduced prevalence of M. leprae infection in the endemic countries following implementation of multidrug therapy (MDT) program by WHO to treat leprosy, new case detection rates are still high-indicating active transmission. The susceptibility to the mycobacteria and the clinical course of the disease are attributed to the host immune response, which heralds the review of immunopathology of this complex disease.

1. Introduction

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease, is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae , a microorganism that has a predilection for the skin and nerves. Though nonfatal, leprosy is one of the most common causes of nontraumatic peripheral neuropathy worldwide. The disease has been known to man since time immemorial. DNA taken from the shrouded remains of a man discovered in a tomb next to the old city of Jerusalem shows him to be the earliest human proven to have suffered from leprosy. The remains were dated by radiocarbon methods to 1–50 A.D. [ 1 ]. The disease probably originated in Egypt and other Middle Eastern countries as early as 2400 BCE. An apparent lack of knowledge about its treatment facilitated its spread throughout the world. Mycobacterium leprae , the causative agent of leprosy, was discovered by G. H. Armauer Hansen in Norway in 1873, making it the first bacterium to be identified as causing disease in humans [ 2 , 3 ]. Over the past 20 years, the WHO implementation of MDT has rendered leprosy a less prevalent infection in 90% of its endemic countries with less than one case per 10,000 population. Though, it continues to be a public health problem in countries like Brazil, Congo, Madagascar, Mozambique, Nepal, and Tanzania [ 4 ].

2. Mycobacterium leprae

M. leprae , an acid-fast bacillus is a major human pathogen. In addition to humans, leprosy has been observed in nine-banded armadillo and three species of primates [ 5 ]. The bacterium can also be grown in the laboratory by injection into the footpads of mice [ 6 ]. Mycobacteria are known for their notoriously slow growth. With the doubling time of 14 days, M. leprae has not yet been successfully cultured in vitro [ 7 , 8 ]. The genome of M. leprae has been sequenced in totality [ 9 ]. It presents with less than 50% coding capacity with a large number of pseudogenes. The remaining M. leprae genes help to define the minimal gene set necessary for in vivo survival of this mycobacterial pathogen as well as genes potentially required for infection and pathogenesis seen in leprosy.

M. lepromatosis is a newly identified mycobacterium which is described to cause disseminated leprosy whose significance is still not clearly understood [ 10 , 11 ].

3. Genetic Determinants of Host Response

Human genetic factors influence the acquisition of leprosy and the clinical course of disease [ 12 ]. Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) association studies showed a low lymphotoxin- α (LTA)-producing allele as a major genetic risk factor for early onset leprosy [ 13 ]. Other SNPs to be associated with disease and/or the development of reactions in several genes, such as vitamin D receptor (VDR), TNF- α , IL-10, IFN- γ , HLA genes, and TLR1 are also suggested [ 14 – 17 ]. Linkage studies have identified polymorphic risk factors in the promoter region shared by two genes: PARK2, coding for an E3-ubiquitin ligase designated Parkin, and PACRG [ 18 ]. A study also suggests that NOD2 genetic variants are associated with susceptibility to leprosy and the development of reactions (type I and type II) [ 19 ].

4. Transmission

Two exit routes of M. leprae from the human body often described are the skin and the nasal mucosa. Lepromatous cases show large numbers of organisms deep in the dermis, but whether they reach the skin surface in sufficient numbers is doubtful [ 20 ]. Although there are reports of acid-fast bacilli being found in the desquamating epithelium of the skin, there are reports that no acid-fast bacilli were found in the epidermis, even after examining a very large number of specimens from patients and contacts [ 21 ]. However, fairly large numbers of M. leprae were found in the superficial keratin layer of the skin of lepromatous leprosy patients, suggesting that the organism could exit along with the sebaceous secretions [ 22 ]. The quantity of bacilli from nasal mucosal lesions in lepromatous leprosy ranges from 10,000 to 10,000,000 [ 23 ]. Majority of lepromatous patients show leprosy bacilli in their nasal secretions as collected through blowing the nose [ 24 ]. Nasal secretions from lepromatous patients could yield as much as 10 million viable organisms per day [ 25 ].

The entry route of M. leprae into the human body is also not definitively known. The skin and the upper respiratory tract are most likely; however, recent research increasingly favours the respiratory route [ 26 , 27 ].

5. Incubation Period

Measuring the incubation period in leprosy is difficult because of the lack of adequate immunological tools and slow onset of the disease. The minimum incubation period reported is as short as a few weeks and this is based on the very occasional occurrence of leprosy among young infants [ 28 ]. The maximum incubation period reported is as long as 30 years, or over, as observed among war veterans known to have been exposed for short periods in endemic areas but otherwise living in nonendemic areas. It is generally agreed that the average incubation period is between three and ten years [ 29 ].

6. Risk Factors

Those living in endemic areas with poor conditions such as inadequate bedding, contaminated water, and insufficient diet, or other diseases that compromise immune function are at highest risk for acquiring M. leprae infection. There has been concern that coinfection with HIV might exacerbate the pathogenesis of leprosy lesions and/or lead to increased susceptibility to leprosy as it is seen with tuberculosis. However, HIV infection has not been reported to increase susceptibility to leprosy, impact on immune response to M. leprae , or to have a significant effect on the pathogenesis of neural or skin lesions to date [ 30 , 31 ]. On the contrary, initiation of antiretroviral treatment has been reported to be associated with activation of subclinical M. leprae infection and exacerbation of existing leprosy lesions (type I reaction) likely as part of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome [ 32 – 34 ].

7. Interaction of M. leprae with Schwann Cells and Macrophages

Schwann cells (SCs) are a major target for infection by M. leprae leading to injury of the nerve, demyelination, and consequent disability. Binding of M. leprae to SCs induces demyelination and loss of axonal conductance [ 35 ]. It has been shown that M. leprae can invade SCs by a specific laminin-binding protein of 21 kDa in addition to PGL-1 [ 36 , 37 ]. PGL-1, a major unique glycoconjugate on the M. leprae surface, binds laminin-2, which explains the predilection of the bacterium for peripheral nerves [ 37 ]. The identification of the M. leprae -targeted SC receptor, dystroglycan (DG), suggests a role for this molecule in early nerve degeneration [ 38 ]. Mycobacterium leprae -induced demyelination is a result of direct bacterial ligation to neuregulin receptor, ErbB2 and Erk1/2 activation, and subsequent MAP kinase signaling and proliferation [ 39 ].

Macrophages are one of the most abundant host cells to come in contact with mycobacteria. Phagocytosis of M. leprae by monocyte-derived macrophages can be mediated by complement receptors CR1 (CD35), CR3 (CD11b/CD18), and CR4 (CD11c/CD18) and is regulated by protein kinase [ 40 , 41 ]. Nonresponsiveness towards M. leprae seems to correlate with a Th2 cytokine profile.

8. Disease Classification

Leprosy is classified within two poles of the disease with transition between the clinical forms [ 42 ]. Clinical, histopathological, and immunological criteria identify five forms of leprosy: tuberculoid polar leprosy (TT), borderline tuberculoid (BT), midborderline (BB), borderline lepromatous (BL), and lepromatous polar leprosy (LL). Patients were divided into two groups for therapeutic purposes: paucibacillary (TT, BT) and multibacillary (midborderline (BB), BL, LL) [ 43 ]. It was recommended later that the classification is to be based on the number of skin lesions, less than or equal to five for paucibacillary (PB) and greater than five for the multibacillary (MB) form.

9. Clinical Features ( Table 1 )

Clinical features of leprosy.

9.1. Indeterminate Leprosy

Indeterminate (I) is a prelude to the determinate forms of leprosy [ 44 , 45 ]. It is characterized by an ill-defined, bizarre hypopigmented macule(s) with a smooth or scaly surface. The sensations over the macule may or may not be impaired. The nerve proximal to the patch may or may not be thickened.

9.2. Polyneuritic Leprosy

Manifesting with only neural signs without any evidence of skin lesions, polyneuritic leprosy mostly well recognized in the Indian subcontinent. The affected nerves are thickened, tender, or both. Localized involvement of the nerves may form nerve abscesses [ 46 ].

9.3. Histoid Leprosy

Histoid leprosy is relatively uncommon, distinct clinical, and bacteriologic and histopathologic expression of multibacillary leprosy [ 47 ]. It may occur as a primary manifestation of the disease or in consequence to secondary drug resistance to dapsone following irregular and inadequate monotherapy. It manifests as numerous cutaneous nodules and plaques primarily over the back, buttocks, face, and bony prominences.

10. Histopathological Reactions

Histopathologically, skin lesions from tuberculoid patients are characterized by inflammatory infiltrate containing well-formed granulomas with differentiated macrophages, epithelioid and giant cells, and a predominance of CD4 + T cells at the lesion site, with low or absent bacteria. Patients show a vigorous-specific immune response to M. leprae with a Th1 profile, IFN- γ production, and a positive skin test (lepromin or Mitsuda reaction).

Lepromatous patients present with several skin lesions with a preponderance of CD8 + T cells in situ, absence of granuloma formation, high bacterial load, and a flattened epidermis [ 48 ]. The number of bacilli from a newly diagnosed lepromatous patient can reach 10 12 bacteria per gram of tissue. Patients with LL leprosy have a CD4 : CD8 ratio of approximately 1 : 2 with a predominant Th2 type response and high titers of anti- M. leprae antibodies. Cell-mediated immunity against M. leprae is either modest or absent, characterized by negative skin test and diminished lymphocyte proliferation [ 49 , 50 ].

11. Leprosy Reactions

Leprosy reactions are the acute episodes of clinical inflammation occurring during the chronic course of disease. They pose a challenging problem because they increase morbidity due to nerve damage even after the completion of treatment. They are classified as type I (reversal reaction; RR) or type II (erythema nodosum leprosum; ENL) reactions. Type I reaction occurs in borderline patients (BT, midborderline and BL) whereas ENL only occurs in BL and LL forms. Reactions are interpreted as a shift in patients' immunologic status. Chemotherapy, pregnancy, concurrent infections, and emotional and physical stress have been identified as predisposing conditions to reactions [ 51 ]. Both types of reactions have been found to cause neuritis, representing the primary cause of irreversible deformities.

Type I reaction is characterized by edema and erythema of existing skin lesions, the formation of new skin lesions, neuritis, additional sensory and motor loss, and edema of the hands, feet, and face, but systemic symptoms are uncommon. The presence of an inflammatory infiltrate with a predominance of CD4 + T cells, differentiated macrophages and thickened epidermis have been observed in RR. Type II reaction is characterized by the appearance of tender, erythematous, subcutaneous nodules located on apparently normal skin, and is frequently accompanied by systemic symptoms, such as fever, malaise, enlarged lymph nodes, anorexia, weight loss, arthralgia, and edema. Additional organs including the testes, joints, eyes, and nerves may also be affected. There may be significant leukocytosis that typically recedes after the reactional state. Presence of high levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF- α , IL-6, and IL-1 β in the sera of ENL patients suggests that these pleiotropic inflammatory cytokines may be at least partially responsible for the clinical manifestations of a type II reaction [ 52 , 53 ].

12. Immunology of Leprosy Reactions

Type I reaction is a naturally occurring delayed-type hypersensitivity response to M. leprae . Clinically, it is characterized by “upgrading” of the clinical picture towards the tuberculoid pole, including a reduction in bacillary load. Immunologically, it is characterized by the development of strong skin test reactivity as well as lymphocyte responsiveness and a predominant Th1 response [ 54 , 55 ]. RR episodes have been associated with the infiltration of IFN- γ and TNF-secreting CD4 + lymphocytes in skin lesions and nerves, resulting in edema and painful inflammation [ 56 , 57 ]. Immunologic markers like CXCL10 are described as a potential tool for discriminating RR [ 58 ]. A significant increase in FoxP3 staining was observed in RR patients compared with ENL and patients with nonreactional leprosy, implying a role for regulatory T cells in RR [ 59 ].

Pathogenesis of type II reaction is thought to be related to the deposition of immune complexes [ 60 ]. Increased levels of TNF- α , IL-1 β , IFN- γ , and other cytokines in type II reactions are observed [ 61 – 63 ]. In addition, C-reactive protein, amyloid A protein, and α -1 antitrypsin have also been reported to be elevated in ENL patients' sera [ 64 ]. A massive infiltrate of polymorphonuclear cells (PMN) in the lesions is only observed during ENL and some patients present with high numbers of neutrophils in the blood as well. Neutrophils may contribute to the bulk of TNF production that is associated with tissue damage in leprosy. More recently, microarray analysis demonstrated that the mechanism of neutrophil recruitment in ENL involves the enhanced expression of E-selectin and IL-1 β , likely leading to neutrophil adhesion to endothelial cells; again, an effect of thalidomide on PMN function was observed since this drug inhibited the neutrophil recruitment pathway [ 65 ]. Altogether, the data highlight some of the possible mechanisms for thalidomide's efficacy in treating type II reaction. TNF- α may augment the immune response towards the elimination of the pathogen and/or mediate the pathologic manifestations of the disease. TNF- α can be induced following stimulation of cells with total, or components of M. leprae , namely, lipoarabinomannan (the mycobacteria “lipopolysaccharide-” like component) a potent TNF inducer [ 66 ]. In addition, mycolyl-arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan complex of Mycobacterium species, the protein-peptidoglycan complex, and muramyl dipeptide all elicit significant TNF- α release [ 66 ].

share this!

April 15, 2024

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies . Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

written by researcher(s)

A young Black scientist discovered a pivotal leprosy treatment in the 1920s—but an older colleague took the credit

by Mark M. Lambert, The Conversation

Hansen's disease, also called leprosy, is treatable today—and that's partly thanks to a curious tree and the work of a pioneering young scientist in the 1920s. Centuries prior to her discovery, sufferers had no remedy for leprosy's debilitating symptoms or its social stigma.

This young scientist, Alice Ball , laid fundamental groundwork for the first effective leprosy treatment globally. But her legacy still prompts conversations about the marginalization of women and people of color in science today.

As a bioethicist and historian of medicine , I've studied Ball's contributions to medicine, and I'm pleased to see her receive increasing recognition for her work, especially on a disease that remains stigmatized .

Who was Alice Ball?

Alice Augusta Ball, born in Seattle, Washington, in 1892, became the first woman and first African American to earn a master's degree in science from the College of Hawaii in 1915, after completing her studies in pharmaceutical chemistry the year prior.

After she finished her master's degree, the college hired her as a research chemist and instructor, and she became the first African American with that title in the chemistry department.

Impressed by her master's thesis on the chemistry of the kava plant , Dr. Harry Hollmann with the Leprosy Investigation Station of the U.S. Public Health Service in Hawaii recruited Ball. At the time, leprosy was a major public health issue in Hawaii .

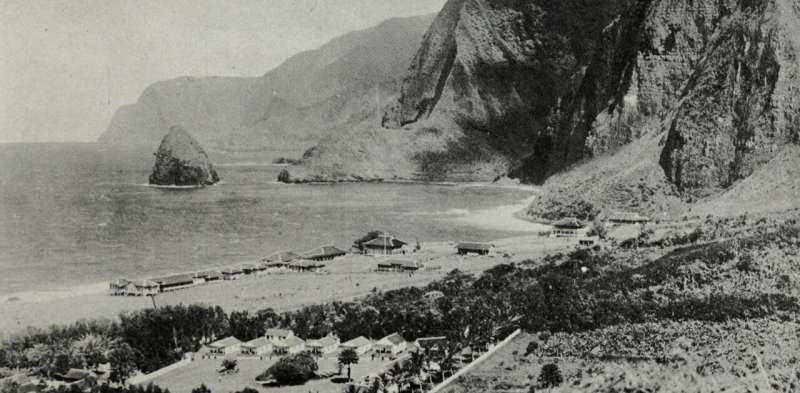

Doctors now understand that leprosy, also called Hansen's disease, is minimally contagious. But in 1865, the fear and stigma associated with leprosy led authorities in Hawaii to implement a mandatory segregation policy, which ultimately isolated those with the disease on a remote peninsula on the island of Molokai . In 1910, over 600 leprosy sufferers were living in Molokai .

This policy overwhelmingly affected Native Hawaiians, who accounted for over 90% of all those exiled to Molokai .

The significance of chaulmoogra oil

Doctors had attempted to use nearly every remedy imaginable to treat leprosy, even experimenting with dangerous substances such as arsenic and strychnine . But the lone consistently effective treatment was chaulmoogra oil.

Chaulmoogra oil is derived from the seeds of the chaulmoogra tree . Health practitioners in India and Burma had been using this oil for centuries as a treatment for various skin diseases. But there were limitations with the treatment, and it had only marginal effects on leprosy.

The oil is very thick and sticky, which makes it hard to rub into the skin. The drug is also notoriously bitter, and patients who ingested it would often start vomiting. Some physicians experimented with injections of the oil, but this produced painful pustules .

The Ball Method

If researchers could harness chaulmoogra's curative potential without the nasty side effects, the tree's seeds could revolutionize leprosy treatment. So, Hollmann turned to Ball. In a 1922 article , Hollmann documents how the 23-year-old Ball discovered how to chemically adapt chaulmoogra into an injection that had none of the side effects.

The Ball Method, as Hollmann called her discovery, transformed chaulmoogra oil into the most effective treatment for leprosy until the introduction of sulfones in the late 1940s .

In 1920, the Ball Method successfully treated 78 patients in Honolulu. A year later, it treated 94 more, with the Public Health Service noting that the morale of all the patients drastically improved. For the first time, there was hope for a cure.

Tragically, Ball did not have the opportunity to revel in this achievement , as she passed away within a year at only 24, likely from exposure to chlorine gas in the lab.

Ball's legacy, lost and found

Ball's death meant she didn't have the opportunity to publish her research. Arthur Dean, chair of the College of Hawaii's chemistry department, took over the project.

Dean mass-produced the treatment and published a series of articles on chaulmoogra oil. He renamed Ball's method the "Dean Method," and he never credited Ball for her work .

Ball's other colleagues did attempt to protect Ball's legacy. A 1920 article in the Journal of the American Medical Association praises the Ball Method, while Hollmann clearly credits Ball in his own 1922 article .

Ball is described at length in a 1922 article in volume 15, issue 5 , of Current History, an academic publication on international affairs. That feature is excerpted in a June 1941 issue of Carter G. Woodson's "Negro History Bulletin," referring to Ball's achievement and untimely death.

Joseph Dutton , a well-regarded religious volunteer at the leprosy settlements on Molokai, further referenced Ball's work in a 1932 memoir broadly published for a popular audience.

Historians such as Paul Wermager later prompted a modern reckoning with Ball's poor treatment by Dean and others, ensuring that Ball received proper credit for her work. Following Wermager's and others' work, the University of Hawaii honored Ball in 2000 with a bronze plaque , affixed to the last remaining chaulmoogra tree on campus.

In 2019, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine added Ball's name to the outside of its building. Ball's story was even featured in a 2020 short film, " The Ball Method ."

The Ball Method represents both a scientific achievement and a history of marginalization. A young woman of color pioneered a medical treatment for a highly stigmatizing disease that disproportionately affected an already disenfranchised Indigenous population.

In 2022, then-Gov. David Ige declared Feb. 28 Alice Augusta Ball Day in Hawaii. It was only fitting that the ceremony took place on the Mānoa campus in the shade of the chaulmoogra tree.

Provided by The Conversation

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Deer are expanding north, and that's not good for caribou: Scientists evaluate the reasons why

29 minutes ago

Warming Arctic reduces dust levels in parts of the planet, study finds

Freeze casting—a guide to creating hierarchically structured materials

Scientists replace fishmeal in aquaculture with microbial protein derived from soybean processing wastewater

Advanced cell atlas opens new doors in biomedical research

Cocaine is an emerging contaminant of concern in the Bay of Santos (Brazil), says researcher

Study says it's likely a warmer world made deadly Dubai downpours heavier

Study shows the longer spilled oil lingers in freshwater, the more persistent compounds it produces

IRIS beamline at BESSY II gets a new nanospectroscopy end station

2 hours ago

The secret to saving old books could be gluten-free glues

Relevant physicsforums posts, cover songs versus the original track, which ones are better.

4 hours ago

Interesting anecdotes in the history of physics?

20 hours ago

Great Rhythm Sections in the 21st Century

Apr 24, 2024

Biographies, history, personal accounts

Apr 23, 2024

History of Railroad Safety - Spotlight on current derailments

Apr 21, 2024

For WW2 buffs!

Apr 20, 2024

More from Art, Music, History, and Linguistics

Related Stories

Dung beetles found to work together to drag dung balls over objects in their path

Jan 24, 2024

High-tech soccer ball unveiled for Euro 2024 promises more accurate offside decisions

Nov 15, 2023

Science uncovers the secret to superb shots in soccer

Sep 8, 2022

Stabilize those stability ball workouts

Jun 11, 2018

Ancient ballcourt in Mexico suggests game was played in the highlands earlier than thought

Mar 16, 2020

Want to watch the sun safely with a large group? Get a disco ball

Oct 10, 2023

Recommended for you

Saturday Citations: Irrationality modeled; genetic basis for PTSD; Tasmanian devils still endangered

Saturday Citations: Listening to bird dreams, securing qubits, imagining impossible billiards

Apr 13, 2024

Saturday Citations: AI and the prisoner's dilemma; stellar cannibalism; evidence that EVs reduce atmospheric CO₂

Apr 6, 2024

Saturday Citations: 100-year-old milk, hot qubits and another banger from the Event Horizon Telescope project

Mar 30, 2024

Saturday Citations: An anemic galaxy and a black hole with no influence. Also: A really cute bug

Mar 23, 2024

Saturday Citations: The volcanoes of Mars; Starship launched; 'Try our new menu item,' say Australian researchers

Mar 16, 2024

Let us know if there is a problem with our content

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Leprosy is an age-old disease and is described in the literature of ancient civilizations. It is a chronic infectious disease which is caused by a type of bacteria called Mycobacterium leprae. The disease affects the skin, the peripheral nerves, mucosa of the upper respiratory tract, and the eyes. Leprosy is curable and treatment in the early ...

Leprosy is a disease with myriad different presentations, largely due to the broad immune response towards the M. leprae strain. Ridley-Jopling classification system covers the entire depth of the clinical feature. From an intense immune response with a small number of tuberculoid organisms to a minor response with an elevated number of ...

The most common clinical presentation of leprosy is hypopigmented or erythematous patches that exhibit associated loss of sensation (Figure 2). Neural involvement occurs very early in the process and assessing for altered sensation can expedite the diagnosis. Clinical findings are determined by the type of immune response mounted by the patient.

Leprosy is not spread by touch, since the mycobacteria are incapable of crossing intact skin. Living near people with leprosy is associated with increased transmission. Among household contacts, the relative risk for leprosy is increased 8- to 10-fold in multibacillary and 2- to 4-fold in paucibacillary forms.