Seeing through another's eyes

Research shows how we use others’ viewpoints to make decisions.

Everyday life is full of situations that require us to take others' perspectives -- for example, when showing a book to a child, we intuitively know how to hold it so that they can see it well, even if it is harder to see for ourselves. Or when performing before an audience, we often can't help but picture how we will look to the other people.

New research published on 21 February in Current Biology has provided the first direct evidence that we can do this because we spontaneously form mental images of how the world looks to the other person, so that we can virtually see through their eyes and make judgements as if it was what we were seeing.

The study, led by Eleanor Ward, Dr Giorgio Ganis and Dr Patric Bach at the University of Plymouth, focused on a mental rotation task commonly used in psychology, where participants are asked whether a rotated letter on computer screen is presented in its standard form (e.g. "R") or mirror-inverted form ("?"). Usually, the more a letter is rotated away from the person judging it, the longer it takes to decide its form. The reason for this is that people first have to mentally rotate the object back to its upright orientation before being able to judge its form, and this rotation takes longer the more the letter is oriented away.

But the new study reveals that people can bypass this mental rotation when another person is introduced. The study shows that even when items are oriented away from participants, their decision times are surprisingly fast if the item appears upright to the other person and is therefore easily identifiable from their perspective. In contrast, if the letter appears upside down for the other person, even relatively easy judgements become harder for the participants.

Lead author Eleanor Ward, PhD student in the University of Plymouth School of Psychology explained: "This study shows that what we see can be overridden by what another person sees if it helps us to make a judgement. People do not need to mentally rotate an object if they already 'see' the object in the usual upright orientation from the eyes of another.

"People did this even though we did not give them instructions about the extra person introduced and they viewed them completely passively. They still used the extra set of eyes, which suggests it is a process that occurs spontaneously."

You can try out the task in this short demo video here: http://www.psy.plymouth.ac.uk/research/actionprediction/Shared/VPT_demo.mp4

Importantly, the study did not find the same speeding up of judgments when an inanimate object (a lamp) was introduced instead of a person, even though the lamp was roughly the same size and was oriented towards the letter in the same way as the person's. This makes sense as a lamp can't 'see' so participants would not construct an image of how the world looks to an inanimate object.

Eleanor continued: "Imagine you're in a car and you see a pedestrian crossing the road, and a bus is travelling at speed towards the crossing. Suddenly you realize the driver hasn't seen the pedestrian and could hit them, so you beep your horn. How did you make this split-second decision? Our study suggests you automatically put yourself in the bus driver's shoes and saw the scene through their eyes."

Dr Patric Bach, who is the head of the Action Prediction Lab where the research was carried out, added: "Perspective taking is an important part of social cognition. It helps us understand how the world looks from another's point of view. It is important for many everyday activities in which we need interact with other people. It helps us to empathize with them, or to work out what they are thinking.

"Our study provides new insights that people can do this because they very quickly and spontaneously form a mental image of how the world looks to another person. As soon as we have such a mental image, it is easy to put ourselves in the other person's place and to predict how they will behave."

- Child Psychology

- Public Health

- World Development

- Popular Culture

- Legal Issues

- Psychopathology

- Social cognition

- Psychologist

Story Source:

Materials provided by University of Plymouth . Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference :

- Eleanor Ward, Giorgio Ganis, Patric Bach. Spontaneous Vicarious Perception of the Content of Another’s Visual Perspective . Current Biology , 2019; DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.01.046

Cite This Page :

Explore More

- Humans and Earth's Deep Subsurface Fluid Flow

- Holographic Displays: An Immersive Future

- Harvesting Energy Where River Meets Sea

- Making Diamonds at Ambient Pressure

- Eruption of Mega-Magnetic Star

- Clean Fuel Generation With Simple Twist

- Bioluminescence in Animals 540 Million Years Ago

- Fossil Frogs Share Their Skincare Secrets

- Fussy Eater? Most Parents Play Short Order Cook

- Precise Time Measurement: Superradiant Atoms

Trending Topics

Strange & offbeat.

2.1 Why Is Research Important?

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how scientific research addresses questions about behavior

- Discuss how scientific research guides public policy

- Appreciate how scientific research can be important in making personal decisions

Scientific research is a critical tool for successfully navigating our complex world. Without it, we would be forced to rely solely on intuition, other people’s authority, and blind luck. While many of us feel confident in our abilities to decipher and interact with the world around us, history is filled with examples of how very wrong we can be when we fail to recognize the need for evidence in supporting claims. At various times in history, we would have been certain that the sun revolved around a flat earth, that the earth’s continents did not move, and that mental illness was caused by possession ( Figure 2.2 ). It is through systematic scientific research that we divest ourselves of our preconceived notions and superstitions and gain an objective understanding of ourselves and our world.

The goal of all scientists is to better understand the world around them. Psychologists focus their attention on understanding behavior, as well as the cognitive (mental) and physiological (body) processes that underlie behavior. In contrast to other methods that people use to understand the behavior of others, such as intuition and personal experience, the hallmark of scientific research is that there is evidence to support a claim. Scientific knowledge is empirical : It is grounded in objective, tangible evidence that can be observed time and time again, regardless of who is observing.

While behavior is observable, the mind is not. If someone is crying, we can see behavior. However, the reason for the behavior is more difficult to determine. Is the person crying due to being sad, in pain, or happy? Sometimes we can learn the reason for someone’s behavior by simply asking a question, like “Why are you crying?” However, there are situations in which an individual is either uncomfortable or unwilling to answer the question honestly, or is incapable of answering. For example, infants would not be able to explain why they are crying. In such circumstances, the psychologist must be creative in finding ways to better understand behavior. This chapter explores how scientific knowledge is generated, and how important that knowledge is in forming decisions in our personal lives and in the public domain.

Use of Research Information

Trying to determine which theories are and are not accepted by the scientific community can be difficult, especially in an area of research as broad as psychology. More than ever before, we have an incredible amount of information at our fingertips, and a simple internet search on any given research topic might result in a number of contradictory studies. In these cases, we are witnessing the scientific community going through the process of reaching a consensus, and it could be quite some time before a consensus emerges. For example, the explosion in our use of technology has led researchers to question whether this ultimately helps or hinders us. The use and implementation of technology in educational settings has become widespread over the last few decades. Researchers are coming to different conclusions regarding the use of technology. To illustrate this point, a study investigating a smartphone app targeting surgery residents (graduate students in surgery training) found that the use of this app can increase student engagement and raise test scores (Shaw & Tan, 2015). Conversely, another study found that the use of technology in undergraduate student populations had negative impacts on sleep, communication, and time management skills (Massimini & Peterson, 2009). Until sufficient amounts of research have been conducted, there will be no clear consensus on the effects that technology has on a student's acquisition of knowledge, study skills, and mental health.

In the meantime, we should strive to think critically about the information we encounter by exercising a degree of healthy skepticism. When someone makes a claim, we should examine the claim from a number of different perspectives: what is the expertise of the person making the claim, what might they gain if the claim is valid, does the claim seem justified given the evidence, and what do other researchers think of the claim? This is especially important when we consider how much information in advertising campaigns and on the internet claims to be based on “scientific evidence” when in actuality it is a belief or perspective of just a few individuals trying to sell a product or draw attention to their perspectives.

We should be informed consumers of the information made available to us because decisions based on this information have significant consequences. One such consequence can be seen in politics and public policy. Imagine that you have been elected as the governor of your state. One of your responsibilities is to manage the state budget and determine how to best spend your constituents’ tax dollars. As the new governor, you need to decide whether to continue funding early intervention programs. These programs are designed to help children who come from low-income backgrounds, have special needs, or face other disadvantages. These programs may involve providing a wide variety of services to maximize the children's development and position them for optimal levels of success in school and later in life (Blann, 2005). While such programs sound appealing, you would want to be sure that they also proved effective before investing additional money in these programs. Fortunately, psychologists and other scientists have conducted vast amounts of research on such programs and, in general, the programs are found to be effective (Neil & Christensen, 2009; Peters-Scheffer, Didden, Korzilius, & Sturmey, 2011). While not all programs are equally effective, and the short-term effects of many such programs are more pronounced, there is reason to believe that many of these programs produce long-term benefits for participants (Barnett, 2011). If you are committed to being a good steward of taxpayer money, you would want to look at research. Which programs are most effective? What characteristics of these programs make them effective? Which programs promote the best outcomes? After examining the research, you would be best equipped to make decisions about which programs to fund.

Link to Learning

Watch this video about early childhood program effectiveness to learn how scientists evaluate effectiveness and how best to invest money into programs that are most effective.

Ultimately, it is not just politicians who can benefit from using research in guiding their decisions. We all might look to research from time to time when making decisions in our lives. Imagine that your sister, Maria, expresses concern about her two-year-old child, Umberto. Umberto does not speak as much or as clearly as the other children in his daycare or others in the family. Umberto's pediatrician undertakes some screening and recommends an evaluation by a speech pathologist, but does not refer Maria to any other specialists. Maria is concerned that Umberto's speech delays are signs of a developmental disorder, but Umberto's pediatrician does not; she sees indications of differences in Umberto's jaw and facial muscles. Hearing this, you do some internet searches, but you are overwhelmed by the breadth of information and the wide array of sources. You see blog posts, top-ten lists, advertisements from healthcare providers, and recommendations from several advocacy organizations. Why are there so many sites? Which are based in research, and which are not?

In the end, research is what makes the difference between facts and opinions. Facts are observable realities, and opinions are personal judgments, conclusions, or attitudes that may or may not be accurate. In the scientific community, facts can be established only using evidence collected through empirical research.

NOTABLE RESEARCHERS

Psychological research has a long history involving important figures from diverse backgrounds. While the introductory chapter discussed several researchers who made significant contributions to the discipline, there are many more individuals who deserve attention in considering how psychology has advanced as a science through their work ( Figure 2.3 ). For instance, Margaret Floy Washburn (1871–1939) was the first woman to earn a PhD in psychology. Her research focused on animal behavior and cognition (Margaret Floy Washburn, PhD, n.d.). Mary Whiton Calkins (1863–1930) was a preeminent first-generation American psychologist who opposed the behaviorist movement, conducted significant research into memory, and established one of the earliest experimental psychology labs in the United States (Mary Whiton Calkins, n.d.).

Francis Sumner (1895–1954) was the first African American to receive a PhD in psychology in 1920. His dissertation focused on issues related to psychoanalysis. Sumner also had research interests in racial bias and educational justice. Sumner was one of the founders of Howard University’s department of psychology, and because of his accomplishments, he is sometimes referred to as the “Father of Black Psychology.” Thirteen years later, Inez Beverly Prosser (1895–1934) became the first African American woman to receive a PhD in psychology. Prosser’s research highlighted issues related to education in segregated versus integrated schools, and ultimately, her work was very influential in the hallmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional (Ethnicity and Health in America Series: Featured Psychologists, n.d.).

Although the establishment of psychology’s scientific roots occurred first in Europe and the United States, it did not take much time until researchers from around the world began to establish their own laboratories and research programs. For example, some of the first experimental psychology laboratories in South America were founded by Horatio Piñero (1869–1919) at two institutions in Buenos Aires, Argentina (Godoy & Brussino, 2010). In India, Gunamudian David Boaz (1908–1965) and Narendra Nath Sen Gupta (1889–1944) established the first independent departments of psychology at the University of Madras and the University of Calcutta, respectively. These developments provided an opportunity for Indian researchers to make important contributions to the field (Gunamudian David Boaz, n.d.; Narendra Nath Sen Gupta, n.d.).

When the American Psychological Association (APA) was first founded in 1892, all of the members were White males (Women and Minorities in Psychology, n.d.). However, by 1905, Mary Whiton Calkins was elected as the first female president of the APA, and by 1946, nearly one-quarter of American psychologists were female. Psychology became a popular degree option for students enrolled in the nation’s historically Black higher education institutions, increasing the number of Black Americans who went on to become psychologists. Given demographic shifts occurring in the United States and increased access to higher educational opportunities among historically underrepresented populations, there is reason to hope that the diversity of the field will increasingly match the larger population, and that the research contributions made by the psychologists of the future will better serve people of all backgrounds (Women and Minorities in Psychology, n.d.).

The Process of Scientific Research

Scientific knowledge is advanced through a process known as the scientific method . Basically, ideas (in the form of theories and hypotheses) are tested against the real world (in the form of empirical observations), and those empirical observations lead to more ideas that are tested against the real world, and so on. In this sense, the scientific process is circular. The types of reasoning within the circle are called deductive and inductive. In deductive reasoning , ideas are tested in the real world; in inductive reasoning , real-world observations lead to new ideas ( Figure 2.4 ). These processes are inseparable, like inhaling and exhaling, but different research approaches place different emphasis on the deductive and inductive aspects.

In the scientific context, deductive reasoning begins with a generalization—one hypothesis—that is then used to reach logical conclusions about the real world. If the hypothesis is correct, then the logical conclusions reached through deductive reasoning should also be correct. A deductive reasoning argument might go something like this: All living things require energy to survive (this would be your hypothesis). Ducks are living things. Therefore, ducks require energy to survive (logical conclusion). In this example, the hypothesis is correct; therefore, the conclusion is correct as well. Sometimes, however, an incorrect hypothesis may lead to a logical but incorrect conclusion. Consider this argument: all ducks are born with the ability to see. Quackers is a duck. Therefore, Quackers was born with the ability to see. Scientists use deductive reasoning to empirically test their hypotheses. Returning to the example of the ducks, researchers might design a study to test the hypothesis that if all living things require energy to survive, then ducks will be found to require energy to survive.

Deductive reasoning starts with a generalization that is tested against real-world observations; however, inductive reasoning moves in the opposite direction. Inductive reasoning uses empirical observations to construct broad generalizations. Unlike deductive reasoning, conclusions drawn from inductive reasoning may or may not be correct, regardless of the observations on which they are based. For instance, you may notice that your favorite fruits—apples, bananas, and oranges—all grow on trees; therefore, you assume that all fruit must grow on trees. This would be an example of inductive reasoning, and, clearly, the existence of strawberries, blueberries, and kiwi demonstrate that this generalization is not correct despite it being based on a number of direct observations. Scientists use inductive reasoning to formulate theories, which in turn generate hypotheses that are tested with deductive reasoning. In the end, science involves both deductive and inductive processes.

For example, case studies, which you will read about in the next section, are heavily weighted on the side of empirical observations. Thus, case studies are closely associated with inductive processes as researchers gather massive amounts of observations and seek interesting patterns (new ideas) in the data. Experimental research, on the other hand, puts great emphasis on deductive reasoning.

We’ve stated that theories and hypotheses are ideas, but what sort of ideas are they, exactly? A theory is a well-developed set of ideas that propose an explanation for observed phenomena. Theories are repeatedly checked against the world, but they tend to be too complex to be tested all at once; instead, researchers create hypotheses to test specific aspects of a theory.

A hypothesis is a testable prediction about how the world will behave if our idea is correct, and it is often worded as an if-then statement (e.g., if I study all night, I will get a passing grade on the test). The hypothesis is extremely important because it bridges the gap between the realm of ideas and the real world. As specific hypotheses are tested, theories are modified and refined to reflect and incorporate the result of these tests Figure 2.5 .

To see how this process works, let’s consider a specific theory and a hypothesis that might be generated from that theory. As you’ll learn in a later chapter, the James-Lange theory of emotion asserts that emotional experience relies on the physiological arousal associated with the emotional state. If you walked out of your home and discovered a very aggressive snake waiting on your doorstep, your heart would begin to race and your stomach churn. According to the James-Lange theory, these physiological changes would result in your feeling of fear. A hypothesis that could be derived from this theory might be that a person who is unaware of the physiological arousal that the sight of the snake elicits will not feel fear.

A scientific hypothesis is also falsifiable , or capable of being shown to be incorrect. Recall from the introductory chapter that Sigmund Freud had lots of interesting ideas to explain various human behaviors ( Figure 2.6 ). However, a major criticism of Freud’s theories is that many of his ideas are not falsifiable; for example, it is impossible to imagine empirical observations that would disprove the existence of the id, the ego, and the superego—the three elements of personality described in Freud’s theories. Despite this, Freud’s theories are widely taught in introductory psychology texts because of their historical significance for personality psychology and psychotherapy, and these remain the root of all modern forms of therapy.

In contrast, the James-Lange theory does generate falsifiable hypotheses, such as the one described above. Some individuals who suffer significant injuries to their spinal columns are unable to feel the bodily changes that often accompany emotional experiences. Therefore, we could test the hypothesis by determining how emotional experiences differ between individuals who have the ability to detect these changes in their physiological arousal and those who do not. In fact, this research has been conducted and while the emotional experiences of people deprived of an awareness of their physiological arousal may be less intense, they still experience emotion (Chwalisz, Diener, & Gallagher, 1988).

Scientific research’s dependence on falsifiability allows for great confidence in the information that it produces. Typically, by the time information is accepted by the scientific community, it has been tested repeatedly.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, Marilyn D. Lovett

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Psychology 2e

- Publication date: Apr 22, 2020

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/2-1-why-is-research-important

© Jan 6, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Science, health, and public trust.

September 8, 2021

Explaining How Research Works

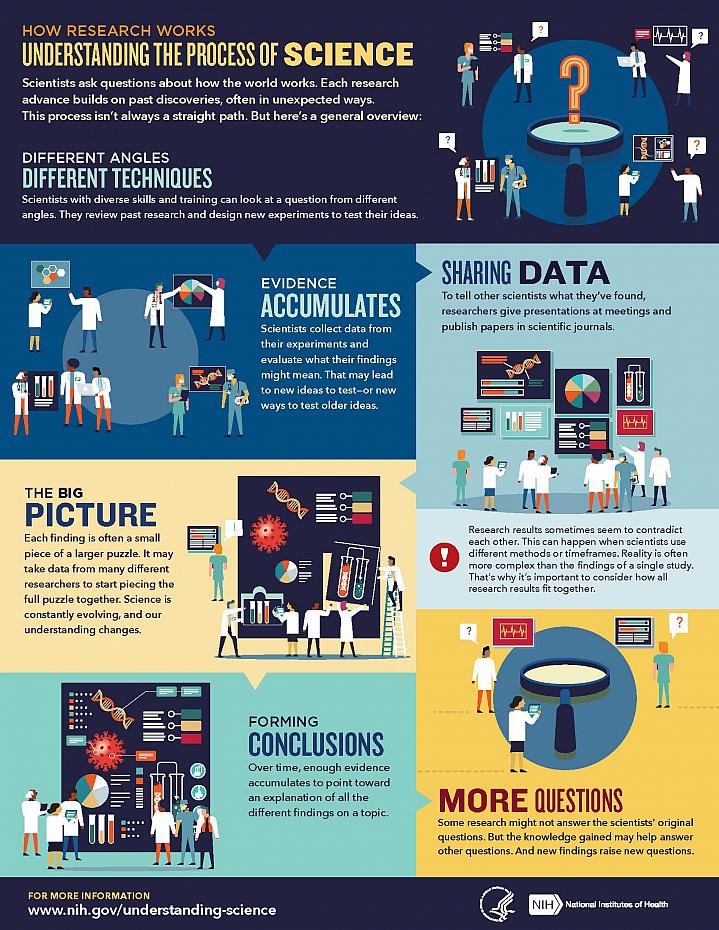

We’ve heard “follow the science” a lot during the pandemic. But it seems science has taken us on a long and winding road filled with twists and turns, even changing directions at times. That’s led some people to feel they can’t trust science. But when what we know changes, it often means science is working.

Explaining the scientific process may be one way that science communicators can help maintain public trust in science. Placing research in the bigger context of its field and where it fits into the scientific process can help people better understand and interpret new findings as they emerge. A single study usually uncovers only a piece of a larger puzzle.

Questions about how the world works are often investigated on many different levels. For example, scientists can look at the different atoms in a molecule, cells in a tissue, or how different tissues or systems affect each other. Researchers often must choose one or a finite number of ways to investigate a question. It can take many different studies using different approaches to start piecing the whole picture together.

Sometimes it might seem like research results contradict each other. But often, studies are just looking at different aspects of the same problem. Researchers can also investigate a question using different techniques or timeframes. That may lead them to arrive at different conclusions from the same data.

Using the data available at the time of their study, scientists develop different explanations, or models. New information may mean that a novel model needs to be developed to account for it. The models that prevail are those that can withstand the test of time and incorporate new information. Science is a constantly evolving and self-correcting process.

Scientists gain more confidence about a model through the scientific process. They replicate each other’s work. They present at conferences. And papers undergo peer review, in which experts in the field review the work before it can be published in scientific journals. This helps ensure that the study is up to current scientific standards and maintains a level of integrity. Peer reviewers may find problems with the experiments or think different experiments are needed to justify the conclusions. They might even offer new ways to interpret the data.

It’s important for science communicators to consider which stage a study is at in the scientific process when deciding whether to cover it. Some studies are posted on preprint servers for other scientists to start weighing in on and haven’t yet been fully vetted. Results that haven't yet been subjected to scientific scrutiny should be reported on with care and context to avoid confusion or frustration from readers.

We’ve developed a one-page guide, "How Research Works: Understanding the Process of Science" to help communicators put the process of science into perspective. We hope it can serve as a useful resource to help explain why science changes—and why it’s important to expect that change. Please take a look and share your thoughts with us by sending an email to [email protected].

Below are some additional resources:

- Discoveries in Basic Science: A Perfectly Imperfect Process

- When Clinical Research Is in the News

- What is Basic Science and Why is it Important?

- What is a Research Organism?

- What Are Clinical Trials and Studies?

- Basic Research – Digital Media Kit

- Decoding Science: How Does Science Know What It Knows? (NAS)

- Can Science Help People Make Decisions ? (NAS)

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

Understanding different research perspectives

Introduction

In this free course, Understanding different research perspectives , you will explore the development of the research process and focus on the steps you need to follow in order to plan and design a HR research project.

The course comprises three parts:

- The first part (Sections 1 and 2) discusses the different perspectives from which an issue or phenomenon can be investigated and outlines how each of these perspectives generates different kinds of knowledge about the issue. It is thus concerned with what it means to ‘know’ in research terms.

- The second part (Sections 3 to 7) identifies the different elements (e.g. methodologies, ethics) of a business research project. In order to produce an effective project, these different elements need to be integrated into a research strategy. The research strategy is your plan of action and will include choices regarding research perspectives and methodologies.

- The third part (Sections 8 to 10) highlights the main methodologies that can be used to investigate a business issue.

This overview of the research perspectives will enable you to take the first steps to develop a work-based project – namely, identifying a research problem and developing the research question(s) you want to investigate.

By the end of this course you should have developed a clear idea of what you want to investigate; in which context you want to do this (e.g. in your organisation, in another organisation, with workers from different organisations); and what are the specific questions you want to address.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course B865 Managing research in the workplace .

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand the different perspectives from which a problem can be investigated

consider the researcher’s involvement in the research process as insider and/or outsider

reflect on the importance of ethical processes in research

understand the development of a research strategy and how this is translated into a research design

identify a research problem to be investigated.

1 Objective and subjective research perspectives

Research in social science requires the collection of data in order to understand a phenomenon. This can be done in a number of ways, and will depend on the state of existing knowledge of the topic area. The researcher can:

- Explore a little known issue. The researcher has an idea or has observed something and seeks to understand more about it (exploratory research).

- Connect ideas to understand the relationships between the different aspects of an issue, i.e. explain what is going on (explanatory research).

- Describe what is happening in more detail and expand the initial understanding (explicatory or descriptive research).

Exploratory research is often done through observation and other methods such as interviews or surveys that allow the researcher to gather preliminary information.

Explanatory research, on the other hand, generally tests hypotheses about cause and effect relationships. Hypotheses are statements developed by the researcher that will be tested during the research. The distinction between exploratory and explanatory research is linked to the distinction between inductive and deductive research. Explanatory research tends to be deductive and exploratory research tends to be inductive. This is not always the case but, for simplicity, we shall not explore the exceptions here.

Descriptive research may support an explanatory or exploratory study. On its own, descriptive research is not sufficient for an academic project. Academic research is aimed at progressing current knowledge.

The perspective taken by the researcher also depends on whether the researcher believes that there is an objective world out there that can be objectively known; for example, profit can be viewed as an objective measure of business performance. Alternatively the researcher may believe that concepts such as ‘culture’, ‘motivation’, ‘leadership’, ‘performance’ result from human categorisation of the world and that their ‘meaning’ can change depending on the circumstances. For example, performance can mean different things to different people. For one it may refer to a hard measure such as levels of sales. For another it may include good relationships with customers. According to this latter view, a researcher can only take a subjective perspective because the nature of these concepts is the result of human processes. Subjective research generally refers to the subjective experiences of research participants and to the fact that the researcher’s perspective is embedded within the research process, rather than seen as fully detached from it.

On the other hand, objective research claims to describe a true and correct reality, which is independent of those involved in the research process. Although this is a simplified view of the way in which research can be approached, it is an important distinction to think about. Whether you think about your research topic in objective or subjective terms will determine the development of the research questions, the type of data collected, the methods of data collection and analysis you adopt and the conclusions that you draw. This is why it is important to consider your own perspective when planning your project.

Subjective research is generally referred to as phenomenological research. This is because it is concerned with the study of experiences from the perspective of an individual, and emphasises the importance of personal perspectives and interpretations. Subjective research is generally based on data derived from observations of events as they take place or from unstructured or semi-structured interviews. In unstructured interviews the questions emerged from the discussion between the interviewer and the interviewee. In semi-structured interviews the interviewer prepares an outline of the interview topics or general questions, adding more as needs emerged during the interview. Structured interviews include the full list of questions. Interviewers do not deviate from this list. Subjective research can also be based on examinations of documents. The researcher will attribute personal interpretations of the experiences and phenomena during the process of both collecting and analysing data. This approach is also referred to as interpretivist research. Interpretivists believe that in order to understand and explain specific management and HR situations, one needs to focus on the viewpoints, experiences, feelings and interpretations of the people involved in the specific situation.

Conversely, objective research tends to be modelled on the methods of the natural sciences such as experiments or large scale surveys. Objective research seeks to establish law-like generalisations which can be applied to the same phenomenon in different contexts. This perspective, which privileges objectivity, is called positivism and is based on data that can be subject to statistical analysis and generalisation. Positivist researchers use quantitative methodologies, which are based on measurement and numbers, to collect and analyse data. Interpretivists are more concerned with language and other forms of qualitative data, which are based on words or images. Having said that, researchers using objectivist and positivist assumptions sometimes use qualitative data while interpretivists sometimes use quantitative data. (Quantitative and qualitative methodologies will be discussed in more detail in the final part of this course.) The key is to understand the perspective you intend to adopt and realise the limitations and opportunities it offers. Table 1 compares and contrasts the perspectives of positivism and interpretivism.

Some textbooks include the realist perspective or discuss constructivism, but, for the purpose of your work-based project, you do not need to engage with these other perspectives. This course keeps the discussion of research perspectives to a basic level.

Search and identify two articles that are based on your research topic. Ideally you may want to identify one article based on quantitative and one based on qualitative methodologies.

Now answer the following questions:

- In what ways are the two studies different (excluding the research focus)?

- Which research perspective do the author/s in article 1 take in their study (i.e. subjective or objective or in other words, phenomenological/interpretivist or positivist)?

- What elements (e.g. specific words, sentences, research questions) in the introduction reveal the approach taken by the authors?

- Which research perspective do the author/s in article 2 take in their study (i.e. subjective or objective, phenomenological/interpretivist or positivist)?

- What elements (e.g. specific words, sentences, research questions) in the introduction and research questions sections reveal the approach taken by the authors?

This activity has helped you to distinguish between objective and subjective research by recognising the type of language and the different ways in which objectivists/positivists and subjectivists/interpretivists may formulate their research aims. It should also support the development of your personal preference on objective or subjective research.

2 The researcher as an outsider or an insider

The researcher’s perspective is not only related to philosophical questions of subjectivity and objectivity but also to the researcher’s position with respect to the subject researched. This is particularly relevant for work-based projects where researchers are looking at their own organisation, group or community. In relation to the researcher’s position, s/he can be an insider or an outsider. Here the term ‘insider’ will include the semi-insider position, and the term ‘outsider’ will include the semi-outsider position. If you belong to the group you want to study, you become an ‘insider-researcher’. For example, if you want to conduct your research project with HR managers and you are a HR manager yourself you will have a common language and a common understanding of the issues associated with doing the same job. While, on one hand, the insider perspective allows special sensitivity, empathy and understanding of the matters, which may not be so clear to an outsider, it may also lead to greater bias or to a research direction that is more important to the researcher. On the other hand, an outsider-researcher would be more detached, less personal, but also less well-informed.

Rabe (2003) suggests that once outsider and insider perspectives in research are examined, three concepts can lead to a better understanding. First, the outsider and insider can be understood by considering the concept of power : there is power involved in the relationship between the researcher and the people and organisations participating in the research. As researchers are gathering data from the research participants, they have the power to represent those participants in any way they choose. The research participants have less power, although they can choose what to say to the researchers. This has different implications for insiders and outsiders. It is obvious that in the case of work-based projects conducted in your organisation, the ways in which you choose to represent your colleagues and your organisation places you in a position of power.

Second, insider and outsider perspectives can be understood in the context of knowledge : the insider has inside knowledge that the outsider does not have. If you conduct research in your organisation, institution or profession you will have access to inside knowledge that an outsider will not be able to gain.

The third way in which the insider/outsider concept can be understood is by considering the role of the researcher in the field of anthropology . In fact, anthropologists approach those being studied (e.g. remote cultures, tribes, social groups) as outsiders. As researchers experience the life of those studied by living with them, they acquire an insider’s perspective. The goal is to obtain both insider and outsider knowledge and to maintain the appropriate detachment. This approach applies to participatory research in general, not only anthropology.

Figure 1 reports the various stages you are expected to follow in order to complete and write up your research report.

3 Deciding what to research

Selecting an appropriate research topic is the first step towards a satisfactory project. For some people, choosing the topic is easy because they have a very specific interest in an area. For example, you might be interested in studying training and development systems in multinational companies (MNCs), or you might have a pressing work issue you want to address, like why the career progression of women in the construction industry is slower than that of men in the same industry. Alternatively, your sponsoring organisation might like you to carry out a specific project that will benefit the organisation itself, for example, it might need a specific HR policy to be developed.

While you may be among those who already have clear ideas, for other learners the process of choosing the research topic can be daunting and frustrating. So how can you generate research ideas? Where should you start? It is easiest to start from your organisational context, if you are currently in employment or if you are volunteering. Is there anything that is bothering you, your colleagues or your department? Is there a HR issue that could be addressed or further developed? Talking about your project with colleagues and family may also help as they may have suggestions that you have not considered.

The following case study describes a process that might help you to identify opportunities in your daily activities that could lead to a suitable topic.

Lucy works as a HR assistant manager for a large manufacturer of confectionery that operates at a national level. The company has three factories and a head office. While the company has a centralised HR function based at the head office, Lucy is based at one of the factories (the largest of the three) that employs 176 workers. The HR department at the factory comprises three HR experts: the manager and two assistants. Their focus is mainly concerned with the training and development of the on-site staff, with the recruitment of factory workers, grievances, disciplinary and day-to-day HR management. It excludes general issues such as salaries, benefits, pensions, recruitment and development of managerial staff and more centralised aspects that are managed by the HR function at head office level.

For some time, Lucy has received feedback through the appraisal system and exit interviews that shop floor workers are dissatisfied by the lack of progression to supervisory level positions within the company. In fact, the company had no career progression plans nor a structured assessment of training needs for factory workers, who make up the majority of employees. Training was provided on-site by supervisors, managers and HR managers and off-site by external consultants when a specific skill or knowledge was needed. Equally employees could request to attend a course by choosing from a list of courses provided on a yearly basis. However, although the company was keen for employees to attend training courses, these were not systematically recorded on the employee file nor did they fit in a wider career plan.

Lucy is doing a part-time postgraduate diploma in HRM at The Open University and she has to complete a research project in order to gain CIPD membership. She has fully considered this issue and thought that it could become a good project. It did not come to her mind immediately but was the result of talks with her HR colleagues and her partner who helped her to see an opportunity where she could not see it.

Lucy talked to supervisors and factory workers and she analysed the organisational documents (appraisal records and exit interview records). Having searched the literature on blue-collar worker career development and training she compiled a loose structure (semi-structured) for interviews to be conducted with shop floor employees. At the end of her course she submitted a project which included the development of an online programme that managed a record system for each employee. The system brought together all the training courses completed as well as the performance records of each employee. It became much easier for managers and supervisors to identify the training courses attended by each employee as well as future training needs.

When people are employed in a job, or on a placement, and are undertaking research in the employing organisation they can be defined as (insider) practitioner–researchers. While the position of insider brings advantages in terms of knowledge and access to information and resources, there may be political issues to consider in undertaking and writing up the project. For example, a controversial or sensitive issue might emerge in the collection of data and the insider researcher has to consider carefully how to present it in their writing. Furthermore, while the organisation or some of its members may initially be willing to collaborate, resistance to full participation may be experienced during some stages of the project. If you are carrying out research in your own organisation it is therefore important to consider, in addition to its feasibility, any political issues likely to emerge and whether your status may affect the process of undertaking the research (Anderson, 2013).

Another way that can help you to identify a topic of investigation is through reading a HR magazine (such as People Management , Personnel Today or HR Magazine ), a journal article or even a newspaper. What topics do they include? Are you interested in any of them? Would the topic appeal to your organisation? Could it be developed into a feasible project?

If you develop an idea, however rudimentary, it is worth writing down the topic and a short sentence that captures some aspects of the topic. For example if the topic is ‘diversity in organisations’, you might want to write a note such as ‘relationship between diversity policy and practices’. From here you can start to develop a map of ideas that will help to identify keywords that can be used to do a more in-depth search of the literature. Figure 2 shows the first step in developing the idea.

The figure shows three general approaches that you might take in developing a research project on diversity in organisations. You may decide to focus on one of these aspects and you could brainstorm it and add elements such as relationships with the various other aspects, national and organisational context, organisational sector, legislation, and aspects of diversity (e.g. age, gender, sexuality, race, etc.). Obviously this is an example but you can apply this process to any topic.

If you have an idea of a topic for your project, take five minutes to think about the possible perspectives from which it can be investigated. Having done this, take a sheet of paper and write the topic in the middle of the page. Alternatively, if you are still uncertain about the topic you want to investigate, you might want to think about the role of the HR practitioner and the various activities associated with this role. As you consider the various aspects of the role of HR practitioner, you may realise that one of these can become your chosen topic.

Starting from this core idea, now draw a mind map or a spider plan focusing on your chosen topic.

Mind mapping gives you a way to illustrate the various elements of an issue or topic and helps to clarify how these elements are linked to each other. A map is a good way to visualise, structure and organise ideas.

Now that you have identified your research topic you can move on to work on the research focus. Activity 3 will help you with this.

Develop a research statement of approximately 600 words explaining your chosen topic, the research problem and how you are thinking of investigating it.

You could start by using the mind map you developed in Activity 2. If you wished, you could do some online research around your topic to get a clearer focus on your own project. You might also read a few sources such as newspaper or magazine articles that are particularly relevant to your topic. These sources may yield some additional aspects for you to investigate. If your topic has been widely researched, try not to feel overwhelmed by the amount of existing information. Focus on one or two articles that appear more closely related to your topic and try to identify the specific area you want to focus on.

Once you have researched the topic, consider the research problem and how this can be investigated. Would you need to interview specific people? Would a questionnaire be more appropriate if you need to access a large number of individuals? Would you need to observe work practices in a specific organisation?

Your statement is a draft research proposal and should include:

- an overview of the topic area with an explanation of why you think this needs to be researched

- the focus of the research and the problem it addresses (and possibly the research questions if you have a clear idea of them at this stage, however, this is not essential if you are still developing the focus of your research)

- how the problem can be investigated (i.e. questionnaire, interviews, secondary data).

You may want to show this proposal to colleagues and other contacts who may be interested in order to gain their feedback about the focus and feasibility.

There is no feedback on this activity.

The next section discusses the ethical issues that need to be considered when doing a research project.

4 Research ethics

Ethics is a fundamental aspect of research and of professional work. Ethics refers to the science of morals and rules of behaviour. It is concerned with the concept of right and wrong conduct in all stages of doing research. However, while the idea of right and wrong conduct may seem straightforward, on reflection you will realise how complex ethics is. Ethics is obviously applied to many aspects of life, not just research, and, in business, topics such as ethics and social responsibility and ethical trading are often brought to people’s attention by the media.

As the meaning of what is ethical behaviour is often subjective and may have controversial elements, think about the following questions and make some notes:

- What does ethics in research mean for you?

- Why is ethical behaviour important for you?

- Why should ethics matter in research?

Research ethics is concerned with the prevention of any harm which may occur during the course of research. This is particularly important if your research involves human participants. Harm refers to psychological as well as physical harm. Human rights and the law must be respected by researchers with regard to the safety and wellbeing of their participants at all times. Research ethics is also concerned with identifying high standards of research conduct and putting them into practice. Cameron and Price (2009) suggest that researcher conduct is guided by a number of different obligations:

- Legal obligations which apply not only to the country in which researchers conduct the project, but also where they collect and store data.

- Professional obligations which are established by professional bodies (e.g. British Psychological Society, The Law Society, CIPD) to guide the conduct of its members.

- Cultural obligations which refer to informal rules regulating the behaviours of people within the society in which they live.

- Personal obligations which include the behavioural choices that individuals make of their own will.

In planning and carrying out a research project researchers should consider their responsibilities to the participants and respondents, to those sponsoring the research, and to the wider research community (Cameron and Price, 2009, p. 121). Before embarking on a research project it is worth identifying all stakeholders and considering your responsibilities towards them.

Generally universities and professional bodies have a list of principles or a code of ethics conduct that governs the research process. The principles to be followed in conducting research with human participants, and which you must follow when collecting data for your research project, are outlined below:

- Informed consent : Potential participants should always be informed in advance, and in understandable terms, of any potential benefits, risks, inconvenience or obligations associated with the research that might reasonably be expected to influence their willingness to participate. This should normally involve the use of an information sheet about the research and what participation will involve, and a signed consent form. Sufficient time shall be allowed for a potential participant to consider their decision from receiving the information sheet to giving their consent. In the case of children (individuals under 16 years of age) informed consent should be given by parents or guardians. An incentive to participate (e.g. a prize or a small payment) should be offered only after consent has been given. Participants should be informed clearly that they have a right to withdraw their consent at any time, that any data that they have provided will be destroyed if they so request and that there will be no resultant adverse consequences.

- Openness and integrity : Researchers should be open and honest about the purpose and content of their research and behave in a professional manner at all times. Covert collection of data should only take place where it is essential to achieve the research results required, where the research objective has strong scientific merit and where there is an appropriate risk management and harm alleviation strategy. Participants should be given opportunities to access the outcomes of research in which they have participated and debriefed, if appropriate, after they have provided data.

- Protection from harm : Researchers must make every effort to minimise the risks of any harm, either physical or psychological. Researchers shall comply with the requirements of the UK Data Protection Act 1998, the Freedom of Information Act 2000 and any other relevant legal frameworks governing the management of personal information in the UK or in any other country in which the research may be conducted. Where research involves children or other vulnerable groups, an appropriate level of disclosure should be obtained from the Disclosure and Barring Service for all researchers in contact with participants.

- Confidentiality : Except where explicit written consent is given, researchers should respect and preserve the confidentiality of participants’ identities and data at all times. The procedures by which this is to be achieved should be specified in the research protocol (an outline of the research topic and strategy).

- Professional codes of practice and ethics : Where the subject of a research project falls within the domain of a professional body with a published code of practice and ethical guidelines, researchers should explicitly state their intention to comply with the code and guidelines in the project protocol. Research within the UK NHS should always be conducted in compliance with an ethical protocol approved by the appropriate NHS Research Ethics Committee.

This guidance has been adapted from, and reflects the principles of, the Open University Research Ethics Guideline. The CIPD’s Code of Professional Conduct provides more information on professional standards in the field of HR.

Look at your research topic mind map and the research statement you wrote for Activity 3. Did you consider ethics? Regardless of whether or not you included ethics in your earlier outline of your research topic, consider what ethical factors could prevent you from conducting a research project on the chosen topic. Write your notes in the space provided below.

Describe at least two types of risks that could be encountered in HR research.

What is informed consent? What factors would you want to know before agreeing to participate in a research study? What should be included in an informed consent form?

This activity added the ethical dimension to the research topic, which was likely to be missed out in a previous outline of the project topic and aim(s). It also compels you to reflect on the specific ethical risks of HR research. There are risks associated with most HR research (e.g. stress can be induced by an interview or questionnaire questions) and it is important to consider them before finalising the research proposal. The activity also encouraged you to consider the elements that should be included in the informed consent form.

The next section considers the research question.

5 Developing research questions

By now you should have a clear direction for your research project. It is now necessary to think about the sorts of questions that you need to formulate in order to define your research project. Will they be ‘what’, ‘how’ or ‘why’ type questions? An important point to bear in mind, as discussed above, is that the wording of a question can be central in defining the scope and direction of the study, including the methodology. Your research question(s) do not necessarily have to be expressed as question(s); they can be statements of purpose. The research question is so called because it is a problem or issue that needs to be solved or addressed. Here are some examples of research questions that focus on different areas of HR. They are expressed as questions but they can easily be changed to research statements if the researcher prefers to present them in that way.

- How do the personal experiences and stories of career development processes among HR professionals in the UK and in Romania differ?

- To what extent do NHS managers engage with age diversity?

- How are organisational recruitment and selection practices influenced by the size of the organisation (e.g. small and medium-sized organisations, large national companies, multinational corporations)?

- In what ways, and for what reasons, does the internal perception of the organisational culture vary in relation to the culture that the organisation portrays in official documents?

- How are absenteeism levels linked to employees’ performance?

The process of producing clearly defined and focused research questions is likely to take some time. You will continue to tweak your research questions in the next few weeks even after you have written your research proposal, read the relevant literature and processed the information. The research questions above are very different but they also have common elements. The next activity invites you to think about research questions, both those in the examples above and your own, which may still be very tentative.

Make notes on the following questions:

- What constitutes a research question?

- What are the main pieces of information that a research question needs to contain?

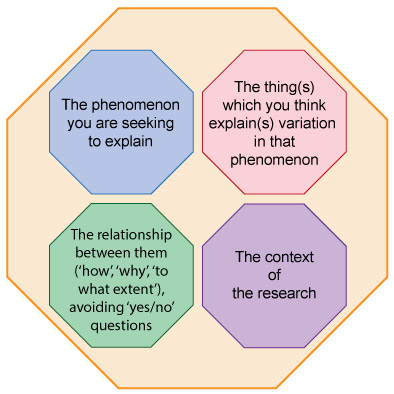

This activity helped you to focus further on your research aims. What you wrote will guide you towards the development of your research questions. Figure 4 shows that research questions can contain a number of elements.

You should now note down possible research questions for your project. You might have only one question or possibly two. You do not need too many questions because you need to be realistic about what you can achieve in the project’s time frame. At the end of this course you will come back to your question(s) and finalise them.

6 Research strategy

A research strategy introduces the main components of a research project such as the research topic area and focus, the research perspective (see Sections 1 and 2), the research design, and the research methods (these are discussed below). It refers to how you propose to answer the research questions set and how you will implement the methodology.

In the first part of this course, you started to identify your research topic, to develop your research statement and you thought about possible research question(s). While you might already have clear research questions or objectives, it is possible that, at this stage, you are uncertain about the most appropriate strategy to implement in order to address those questions. This section looks briefly at a few research strategies you are likely to adopt.

Figure 5 shows the four main types of research strategy: case study, qualitative interviews, quantitative survey and action-oriented research. It is likely that you will use one of the first three; you are less likely to use action-oriented research.

Here is what each of these strategies entails:

- Case Study : This focuses on an in-depth investigation of a single case (e.g. one organisation) or a small number of cases. In case study research generally, information is sought from different sources and through the use of different types of data such as observations, survey, interviews and analysis of documents. Data can be qualitative, quantitative or a mix of both. Case study research allows a composite and multifaceted investigation of the issue or problem.

- Qualitative interviews : There are different types of qualitative interviews (e.g. structured, semi-structured, unstructured) and this is the most widely used method for gathering data. Interviews allow access to rich information. They require extensive planning concerning the development of the structure, decisions about who to interview and how, whether to conduct individual or group interviews, and how to record and analyse them. Interviewees need a wide range of skills, including good social skills, listening skills and communication skills. Interviews are also time-consuming to conduct and they are prone to problems and biases that need to be minimised during the design stage.

- Quantitative survey : This is a widely used method in business research and allows access to significantly high numbers of participants. The availability of online sites enables the wide and cheap distribution of surveys and the organisation of the responses. Although the development of questions may appear easy, to develop a meaningful questionnaire that allows the answering of research questions is difficult. Questionnaires need to appeal to respondents, cannot be too long, too intrusive or too difficult to understand. They also need to measure accurately the issue under investigation. For these reasons it is also advisable, when possible, to use questionnaires that are available on the market and have already been thoroughly validated. This is highly recommended for projects such as the one you need to carry out for this course. When using questionnaires decisions have to be made about the size of the sample and whether and when this is representative of the whole population studied. Surveys can be administered to the whole population (census), for example to all employees of a specific organisation.

- Action-oriented research : This refers to practical business research which is directed towards a change or the production of recommendations for change. Action-oriented research is a participatory process which brings together theory and practice, action and reflection. The project is often carried out by insiders. This is because it is grounded in the need to actively involve participants in order for them to develop ownership of the project. After the project, participants will have to implement the change.

Action-oriented research is not exactly action research, even though they are both grounded in the same assumptions (e.g. to produce change). Action research is a highly complex approach to research, reflection and change which is not always achievable in practice (Cameron and Price, 2009). Furthermore action researchers have to be highly skilled and it is unlikely that for this specific project you will be involved in action research. For these reasons this overview focuses on the less pure action-oriented research strategy. If you are interested in exploring this strategy and action research further, you might want to read Chapter 14 of Cameron and Price (2009).

It is possible for you to choose a strategy that includes the use of secondary data. Secondary data is data that has been collected by other people (e.g. employee surveys, market research data, census). Using secondary data for your research project needs to be justified in that it meets the requirements of the research questions. The use of secondary data has obvious benefits in terms of saving money and time. However, it is important to ascertain the quality of the data and how it was collected; for example, data collected by government agencies would be good quality but it may not necessary meet the needs of your project.

It is important to note that there should be consistency between the perspective (subjective or objective) and the methodology employed. This means that the type of strategy adopted needs to be coherent and that its various elements need to fit in with each other, whether the research is grounded on primary or secondary data.

Now watch this video clip in which Dr Rebecca Hewett, Prof Mark Saunders, Prof Gillian Symon and Prof David Guest discuss the importance of setting the right research question, what strategy they adopted to come up with specific research questions for their projects, and how they refined these initial research questions to focus their research.

Make notes on how you might apply some of these strategies to develop your own research question.

7 Research design

In planning your project you need to think about how you will design and conduct the study as well as how you will present and write up the findings. The design is highly dependent upon the research strategy. It refers to the practical choices regarding how the strategy is implemented in practice. You need to think about what type of data (evidence) would best address the research questions; for example, when considering case study research, questions of design will address the choice of the specific methods of data collection, e.g. if observation, what to observe and how to record it? For how long? Which department or work environment to observe? If interviews are chosen, you need to ask yourself what type? How many? With whom? How long should they be? How will I record them? Where will they be conducted?

The following list (adapted from Cameron and Price, 2009) shows some of the different types of data, or sources of evidence, available to draw on:

- observations

- conversations

- statistics (e.g. government)

- focus groups

- organisational records

- documents (e.g. organisational policies)

- secondary data.

8 Research methodology

The most important methodological choice researchers make is based on the distinction between qualitative and quantitative data. As mentioned previously, qualitative data takes the form of descriptions based on language or images, while quantitative data takes the form of numbers.

Qualitative data is richer and is generally grounded in a subjective and interpretivist perspective. However, while this is generally the case, it is not always so. Qualitative research supports an in-depth understanding of the situation investigated and, due to time constraints, it generally involves a small sample of participants. For this reason the findings are limited to the sample studied and cannot be generalised to other contexts or to the wider population. Popular methods based on qualitative data include semi-structured or unstructured interviews, participant observations and document analysis. Qualitative analysis is generally more time-consuming than quantitative analysis.

Quantitative data, on the other hand, might be easier to collect and analyse and it is based on a large sample of participants. Quantitative methods are based on data that can be ‘objectively’ measured with numbers. The data is analysed through numerical comparisons and statistical analysis. For this reason it appears more ‘scientific’ and may appeal to people who seek clear answers to specific causal questions. Quantitative analysis is often quicker to carry out as it involves the use of software. Owing to the large number of respondents it allows generalisation to a wider group than the research sample. Popular methods based on quantitative data include questionnaires and organisational statistical records among others.

The choice of which methodology to use will depend on your research questions, the formulation of which is consequently informed by your research perspective. Generally, unstructured or semi-structured interviews produce qualitative data and questionnaires produce quantitative data, but such a distinction is not always applicable. In fact, language-based data can often be translated into numbers; for example, by reporting the frequency of certain key words. Questionnaires can produce quantitative as well as qualitative data; for example, multiple choice questions produce quantitative data, while open questions produce qualitative data.

Go back to the two papers you started reading in Activity 1 and read the methodology sections (they may be called methods or something similar) of both papers.

Now answer the following questions.

- What type of method(s) have the author/s in article 1 used to collect data?

- What method of analysis have these author/s used?

- What type of method(s) have the author/s in article 2 used to collect data?

- What methods of analysis have these author/s used?

- How do you think the methods used in both papers address the initial research aims or questions?

- Why do you think the methods used in both papers are appropriate to address these initial research aims or questions?

If you have chosen two papers based on different methodologies, you should reflect on the link between the ways in which the purposes of the studies were developed and the specific methods that the authors chose to address those questions. In the articles there should be a fit between research questions and methodology for collecting and analysing the data. The activity should have helped you to familiarise yourself with processes of planning a research methodology that fits the research question.

This course so far has given you an overview of the research strategy, design and possible methodologies for collecting data. What you have learned should be enough for you to have developed a clear idea of the general research strategy you want to adopt before you move on to develop your methodology for collecting data and review the methods in detail so that you are clear about the benefits and limitations of each before you collect your data.

9 Further development of your research questions

Before you embark on collecting data for your project, it is necessary to have a clear and specific focus for your research – i.e. the research aim, purpose or question(s). Section 5 gave you some examples of research questions. As a research question does not necessarily need to be expressed as a question (it is called a question because it is a problem to be solved), a study can have one general research aim or question and a few secondary aims or questions. It may also have only one research aim or question. In the case of quantitative studies, a few hypotheses might be developed. These will emerge from gaps in the literature but would have to derive from, and be linked to, an overall research purpose. Section 10 discusses research hypotheses.

The clear development of one or more research questions will guide the development of your data collection process and the tool(s) or instrument(s) you will use. Your research question should emerge from a specific need to acquire greater knowledge about a phenomenon or a situation. Such need may be a personal one as well as a contextual and organisational need. Box 1 gives an example of this.

Box 1 An example of how to develop a research question

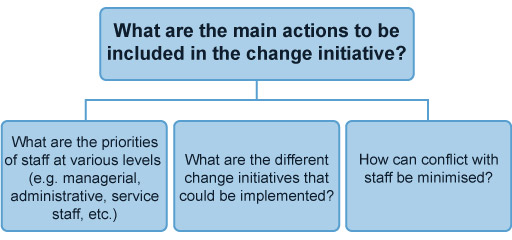

As a consequence of government cuts, your arts organisation has to re-structure and this is causing stress and tension among staff. You are involved in the planning of the change initiative and want to develop an organisational change programme that minimises stress and conflict. In order to do so you need to know more about people’s views, at the various organisational levels.

What type of questions would help you to:

- understand the context

- demonstrate to the various research stakeholders (e.g. organisational members and research participants or supervisor, etc.) what you intend to do.

Perhaps you would like to make some notes of your initial ideas and think about how you could apply this process to developing your own research question.

Reading around the topic will help you to achieve greater focus, as will discussing your initial questions with colleagues or supervisor. In the example above, assuming the literature has been searched and several articles on change management and business restructuring have been read, you are likely to have developed clearer ideas about what you want to investigate and how you want to investigate it. Figure 6 shows what the main research question and the sub-questions or objectives might be:

This example is very well developed and would constitute a much larger project than the work-based project you might be doing. However the development of a general question and more specific questions focusing on different aspects should give you an idea of the relationship between the main question and the sub-questions.

In developing your research questions you also need to be concerned with issues of feasibility in terms of access and time. You do not need to be over ambitious but you need to realistically evaluate how difficult it would be to get the data you are planning in the time you have available before submitting the project at the end of the course. You need to plan a project that is neither too broad nor too narrow in scope and one that can be carried out in the available time.

Revisit your research topic and look back at the notes you have made about the topic (including the mind map you developed earlier in the course). Expand and amend where you need to.

Now think about what you need to do to re-write your statement as a research question and write the question in the space provided below.

Write a maximum of four sub-questions or research objectives that will help you to answer the main research question given above. In formulating the sub-questions make sure you consider the scope and the feasibility of the project. Write your questions in the space provided below.

10 Research hypotheses

For quantitative studies a research question can be further focused into a hypothesis. This is not universally the case – especially in exploratory research when little is known and so it is difficult to develop hypotheses – however it is generally the case in explanatory projects. A hypothesis usually makes a short statement concerning the relationship between two or more aspects or variables; the research thus aims to verify the hypothesis through investigation. According to Verma and Beard (1981, p. 184) ‘in many cases hypotheses are hunches that the researcher has about the existence of relationships between variables’. A hypothesis differs from a research question in several ways. The main difference is that a question is specific and asks about the relationship between different aspects of a problem or issue, whereas a hypothesis suggests a possible answer to the problem, which can then be tested empirically. You will now see how a research question (RQ) may be formulated as a research hypothesis (RH).

- RQ: Does motivation affect employees’ performance?

This is a well-defined research question; it explores the contribution of motivation to the work performance of employees. The question omits other possible causes, such as organisational resources and market conditions. This question could be turned into a research hypothesis by simply changing the emphasis:

- RH: Work motivation is positively related to employees’ performance.

The key elements of a hypothesis are:

- The variables used in a hypothesis must all be empirically measurable (e.g. you need to be able to measure motivation and performance objectively).

- A hypothesis should provide an answer (albeit tentatively) to the question raised by the problem statement.

- A hypothesis should be as simple as possible.

If you are planning to do an explanatory quantitative study, you will need to develop hypotheses. You will develop your hypotheses once you have read and reviewed the literature and have become familiar with previous knowledge about the topic.

In this free course, Understanding different research perspectives , the various perspectives (subjective/objective and interpretivist/positivist) that a researcher can take in investigating a problem have been discussed, as well as the issues that need to be considered in planning the project (ethics, research design, research strategy and research methodology). This fits with the first two stages of the overall research process as shown in Table 2.

The activities in this course have guided you through these first two processes.

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Cinzia Priola.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions ), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence .

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Course Image: © Kristian Sekulic/iStockphoto.com

Figure 2: © Yuri/iStockphoto.com

4. Research Ethics: CIPD’s Code of Professional Conduct: courtesy of Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD)