How to Write a Research Paper: Parts of the Paper

- Choosing Your Topic

- Citation & Style Guides This link opens in a new window

- Critical Thinking

- Evaluating Information

- Parts of the Paper

- Writing Tips from UNC-Chapel Hill

- Librarian Contact

Parts of the Research Paper Papers should have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Your introductory paragraph should grab the reader's attention, state your main idea, and indicate how you will support it. The body of the paper should expand on what you have stated in the introduction. Finally, the conclusion restates the paper's thesis and should explain what you have learned, giving a wrap up of your main ideas.

1. The Title The title should be specific and indicate the theme of the research and what ideas it addresses. Use keywords that help explain your paper's topic to the reader. Try to avoid abbreviations and jargon. Think about keywords that people would use to search for your paper and include them in your title.

2. The Abstract The abstract is used by readers to get a quick overview of your paper. Typically, they are about 200 words in length (120 words minimum to 250 words maximum). The abstract should introduce the topic and thesis, and should provide a general statement about what you have found in your research. The abstract allows you to mention each major aspect of your topic and helps readers decide whether they want to read the rest of the paper. Because it is a summary of the entire research paper, it is often written last.

3. The Introduction The introduction should be designed to attract the reader's attention and explain the focus of the research. You will introduce your overview of the topic, your main points of information, and why this subject is important. You can introduce the current understanding and background information about the topic. Toward the end of the introduction, you add your thesis statement, and explain how you will provide information to support your research questions. This provides the purpose and focus for the rest of the paper.

4. Thesis Statement Most papers will have a thesis statement or main idea and supporting facts/ideas/arguments. State your main idea (something of interest or something to be proven or argued for or against) as your thesis statement, and then provide your supporting facts and arguments. A thesis statement is a declarative sentence that asserts the position a paper will be taking. It also points toward the paper's development. This statement should be both specific and arguable. Generally, the thesis statement will be placed at the end of the first paragraph of your paper. The remainder of your paper will support this thesis.

Students often learn to write a thesis as a first step in the writing process, but often, after research, a writer's viewpoint may change. Therefore a thesis statement may be one of the final steps in writing.

Examples of Thesis Statements from Purdue OWL

5. The Literature Review The purpose of the literature review is to describe past important research and how it specifically relates to the research thesis. It should be a synthesis of the previous literature and the new idea being researched. The review should examine the major theories related to the topic to date and their contributors. It should include all relevant findings from credible sources, such as academic books and peer-reviewed journal articles. You will want to:

- Explain how the literature helps the researcher understand the topic.

- Try to show connections and any disparities between the literature.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

More about writing a literature review. . .

6. The Discussion The purpose of the discussion is to interpret and describe what you have learned from your research. Make the reader understand why your topic is important. The discussion should always demonstrate what you have learned from your readings (and viewings) and how that learning has made the topic evolve, especially from the short description of main points in the introduction.Explain any new understanding or insights you have had after reading your articles and/or books. Paragraphs should use transitioning sentences to develop how one paragraph idea leads to the next. The discussion will always connect to the introduction, your thesis statement, and the literature you reviewed, but it does not simply repeat or rearrange the introduction. You want to:

- Demonstrate critical thinking, not just reporting back facts that you gathered.

- If possible, tell how the topic has evolved over the past and give it's implications for the future.

- Fully explain your main ideas with supporting information.

- Explain why your thesis is correct giving arguments to counter points.

7. The Conclusion A concluding paragraph is a brief summary of your main ideas and restates the paper's main thesis, giving the reader the sense that the stated goal of the paper has been accomplished. What have you learned by doing this research that you didn't know before? What conclusions have you drawn? You may also want to suggest further areas of study, improvement of research possibilities, etc. to demonstrate your critical thinking regarding your research.

- << Previous: Evaluating Information

- Next: Research >>

- Last Updated: Feb 13, 2024 8:35 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ucc.edu/research_paper

How to Write a Research Paper

If you already have a headache trying to understand what research paper is all about, we have created an ultimate guide for you on how to write a research paper. You will find all the answers to your questions regarding structure, planning, doing investigation, finding the topic that appeals to you. Plus, you will find out the secret to an excellent paper. Are you at the edge of your seat? Let us start with the basics then.

- What is a Research Paper

- Reasons for Writing a Research Paper

- Report Papers and Thesis Papers

- How to Start a Research Paper

- How to Choose a Topic for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Proposal for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Research Plan

- How to Do Research

- How to Write an Outline for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Thesis Statement for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Research Paper Rough Draft

- How to Write an Introduction for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Body of a Research Paper

- How to Write a Conclusion for a Research Paper

- How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

- How to Revise and Edit a Research Paper

- How to Write a Bibliography for a Research Paper

- What Makes a Good Research Paper

Research Paper Writing Services

What is a research paper.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

You probably know the saying ‘the devil is not as black as he is painted’. This particular saying is absolutely true when it comes to writing a research paper. Your feet are cold even with the thought of this assignment. You have heard terrifying stories from older students. You have never done this before, so certainly you are scared. What is a research paper? How should I start? What are all these requirements about?

Luckily, you have a friend in need. That is our writing service. First and foremost, let us clarify the definition. A research paper is a piece of academic writing that provides information about a particular topic that you’ve researched . In other words, you choose a topic: about historical events, the work of some artist, some social issues etc. Then you collect data on the given topic and analyze it. Finally, you put your analysis on paper. See, it is not as scary as it seems. If you are still having doubts, whether you can handle it yourself, we are here to help you. Our team of writers can help you choose the topic, or give you advice on how to plan your work, or how to start, or craft a paper for you. Just contact us 24/7 and see everything yourself.

5 Reasons for Writing a Research Paper

Why should I spend my time writing some academic paper? What is the use of it? Is not some practical knowledge more important? The list of questions is endless when it comes to a research paper. That is why we have outlined 5 main reasons why writing a research paper is a good thing.

- You will learn how to organize your time

If you want to write a research paper, you will have to learn how to manage your time. This type of assignment cannot be done overnight. It requires careful planning and you will need to learn how to do it. Later, you will be able to use these time-managing skills in your personal life, so why not developing them?

- You will discover your writing skills

You cannot know something before you try it. This rule relates to writing as well. You cannot claim that you cannot write until you try it yourself. It will be really difficult at the beginning, but then the words will come to your head themselves.

- You will improve your analytical skills

Writing a research paper is all about investigation and analysis. You will need to collect data, examine and classify it. These skills are needed in modern life more than anything else is.

- You will gain confidence

Once you do your own research, it gives you the feeling of confidence in yourself. The reason is simple human brain likes solving puzzles and your assignment is just another puzzle to be solved.

- You will learn how to persuade the reader

When you write your paper, you should always remember that you are writing it for someone to read. Moreover, you want this someone to believe in your ideas. For this reason, you will have to learn different convincing methods and techniques. You will learn how to make your writing persuasive. In turns, you will be able to use these methods in real life.

What is the Difference between Report and Thesis Papers?

A common question is ‘what is the difference between a report paper and a thesis paper?’ The difference lies in the aim of these two assignments. While the former aims at presenting the information, the latter aims at providing your opinion on the matter. In other words, in a report paper you have to summarize your findings. In a thesis paper, you choose some issue and defend your point of view by persuading the reader. It is that simple.

A thesis paper is a more common assignment than a report paper. This task will help a professor to evaluate your analytical skills and skills to present your ideas logically. These skills are more important than just the ability to collect and summarize data.

How to Write a Research Paper Step by Step

Research comes from the French word rechercher , meaning “to seek out.” Writing a research paper requires you to seek out information about a subject, take a stand on it, and back it up with the opinions, ideas, and views of others. What results is a printed paper variously known as a term paper or library paper, usually between five and fifteen pages long—most instructors specify a minimum length—in which you present your views and findings on the chosen subject.

It is not a secret that the majority of students hate writing a research paper. The reason is simple it steals your time and energy. Not to mention, constant anxiety that you will not be able to meet the deadline or that you will forget about some academic requirement.

We will not lie to you; a research paper is a difficult assignment. You will have to spend a lot of time. You will need to read, to analyze, and to search for the material. You will probably be stuck sometimes. However, if you organize your work smart, you will gain something that is worth all the effort – knowledge, experience, and high grades.

The reason why many students fail writing a research paper is that nobody explained them how to start and how to plan their work. Luckily, you have found our writing service and we are ready to shed the light on this dark matter.

We have created a step by step guide for you on how to write a research paper. We will dwell upon the structure, the writing tips, the writing strategies as well as academic requirements. Read this whole article and you will see that you can handle writing this assignment and our team of writers is here to assist you.

How to Start a Research Paper?

It all starts with the assignment. Your professor gives you the task. It may be either some general issue or specific topic to write about. Your assignment is your first guide to success. If you understand what you need to do according to the assignment, you are on the road to high results. Do not be scared to clarify your task if you need to. There is nothing wrong in asking a question if you want to do something right. You can ask your professor or you can ask our writers who know a thing or two in academic writing.

It is essential to understand the assignment. A good beginning makes a good ending, so start smart.

Learn how to start a research paper .

Choosing a Topic for a Research Paper

We have already mentioned that it is not enough to do great research. You need to persuade the reader that you have made some great research. What convinces better that an eye-catching topic? That is why it is important to understand how to choose a topic for a research paper.

First, you need to delimit the general idea to a more specific one. Secondly, you need to find what makes this topic interesting for you and for the academia. Finally, you need to refine you topic. Remember, it is not something you will do in one day. You can be reshaping your topic throughout your whole writing process. Still, reshaping not changing it completely. That is why keep in your head one main idea: your topic should be precise and compelling .

Learn how to choose a topic for a research paper .

How to Write a Proposal for a Research Paper?

If you do not know what a proposal is, let us explain it to you. A proposal should answer three main questions:

- What is the main aim of your investigation?

- Why is your investigation important?

- How are you going to achieve the results?

In other words, proposal should show why your topic is interesting and how you are going to prove it. As to writing requirements, they may differ. That is why make sure you find out all the details at your department. You can ask your departmental administrator or find information online at department’s site. It is crucial to follow all the administrative requirements, as it will influence your grade.

Learn how to write a proposal for a research paper .

How to Write a Research Plan?

The next step is writing a plan. You have already decided on the main issues, you have chosen the bibliography, and you have clarified the methods. Here comes the planning. If you want to avoid writer’s block, you have to structure you work. Discuss your strategies and ideas with your instructor. Think thoroughly why you need to present some data and ideas first and others second. Remember that there are basic structure elements that your research paper should include:

- Thesis Statement

- Introduction

- Bibliography

You should keep in mind this skeleton when planning your work. This will keep your mind sharp and your ideas will flow logically.

Learn how to write a research plan .

How to Do Research?

Your research will include three stages: collecting data, reading and analyzing it, and writing itself.

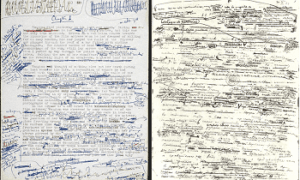

First, you need to collect all the material that you will need for you investigation: films, documents, surveys, interviews, and others. Secondly, you will have to read and analyze. This step is tricky, as you need to do this part smart. It is not enough just to read, as you cannot keep in mind all the information. It is essential that you make notes and write down your ideas while analyzing some data. When you get down to the stage number three, writing itself, you will already have the main ideas written on your notes. Plus, remember to jot down the reference details. You will then appreciate this trick when you will have to write the bibliography.

If you do your research this way, it will be much easier for you to write the paper. You will already have blocks of your ideas written down and you will just need to add some material and refine your paper.

Learn how to do research .

How to Write an Outline for a Research Paper?

To make your paper well organized you need to write an outline. Your outline will serve as your guiding star through the writing process. With a great outline you will not get sidetracked, because you will have a structured plan to follow. Both you and the reader will benefit from your outline. You present your ideas logically and you make your writing coherent according to your plan. As a result, this outline guides the reader through your paper and the reader enjoys the way you demonstrate your ideas.

Learn how to write an outline for a research paper . See research paper outline examples .

How to Write a Thesis Statement for a Research Paper?

Briefly, the thesis is the main argument of your research paper. It should be precise, convincing and logical. Your thesis statement should include your point of view supported by evidence or logic. Still, remember it should be precise. You should not beat around the bush, or provide all the possible evidence you have found. It is usually a single sentence that shows your argument. In on sentence you should make a claim, explain why it significant and convince the reader that your point of view is important.

Learn how to write a thesis statement for a research paper . See research paper thesis statement examples .

Should I Write a Rough Draft for a Research Paper?

Do you know any writer who put their ideas on paper, then never edited them and just published? Probably, no writer did so. Writing a research paper is no exception. It is impossible to cope with this assignment without writing a rough draft.

Your draft will help you understand what you need to polish to make your paper perfect. All the requirements, academic standards make it difficult to do everything flawlessly at the first attempt. Make sure you know all the formatting requirements: margins, words quantity, reference requirements, formatting styles etc.

Learn how to write a rough draft for a research paper .

How to Write an Introduction for a Research Paper?

Let us make it more vivid for you. We have narrowed down the tips on writing an introduction to the three main ones:

- Include your thesis in your introduction

Remember to include the thesis statement in your introduction. Usually, it goes at the end of the first paragraph.

- Present the main ideas of the body

You should tell the main topics you are going to discuss in the main body. For this reason, before writing this part of introduction, make sure you know what is your main body is going to be about. It should include your main ideas.

- Polish your thesis and introduction

When you finish the main body of your paper, come back to the thesis statement and introduction. Restate something if needed. Just make it perfect; because introduction is like the trailer to your paper, it should make the reader want to read the whole piece.

Learn how to write an introduction for a research paper . See research paper introduction examples .

How to Write a Body of a Research Paper?

A body is the main part of your research paper. In this part, you will include all the needed evidence; you will provide the examples and support your argument.

It is important to structure your paragraphs thoroughly. That is to say, topic sentence and the evidence supporting the topic. Stay focused and do not be sidetracked. You have your outline, so follow it.

Here are the main tips to keep in head when writing a body of a research paper:

- Let the ideas flow logically

- Include only relevant information

- Provide the evidence

- Structure the paragraphs

- Make the coherent transition from one paragraph to another

See? When it is all structured, it is not as scary as it seemed at the beginning. Still, if you have doubts, you can always ask our writers for help.

Learn how to write a body of a research paper . See research paper transition examples .

How to Write a Conclusion for a Research Paper?

Writing a good conclusion is important as writing any other part of the paper. Remember that conclusion is not a summary of what you have mentioned before. A good conclusion should include your last strong statement.

If you have written everything according to the plan, the reader already knows why your investigation is important. The reader has already seen the evidence. The only thing left is a strong concluding thought that will organize all your findings.

Never include any new information in conclusion. You need to conclude, not to start a new discussion.

Learn how to write a conclusion for a research paper .

How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper?

An abstract is a brief summary of your paper, usually 100-200 words. You should provide the main gist of your paper in this short summary. An abstract can be informative, descriptive or proposal. Depending on the type of abstract, you need to write, the requirements will differ.

To write an informative abstract you have to provide the summary of the whole paper. Informative summary. In other words, you need to tell about the main points of your work, the methods used, the results and the conclusion of your research.

To write a descriptive abstract you will not have to provide any summery. You should write a short teaser of your paper. That is to say, you need to write an overview of your paper. The aim of a descriptive abstract is to interest the reader.

Finally, to write a proposal abstract you will need to write the basic summary as for the informative abstract. However, the difference is the following: you aim at persuading someone to let you write on the topic. That is why, a proposal abstract should present your topic as the one worth investigating.

Learn how to write an abstract for a research paper .

Should I Revise and Edit a Research Paper?

Revising and editing your paper is essential if you want to get high grades. Let us help you revise your paper smart:

- Check your paper for spelling and grammar mistakes

- Sharpen the vocabulary

- Make sure there are no slang words in your paper

- Examine your paper in terms of structure

- Compare your topic, thesis statement to the whole piece

- Check your paper for plagiarism

If you need assistance with proofreading and editing your paper, you can turn to the professional editors at our service. They will help you polish your paper to perfection.

Learn how to revise and edit a research paper .

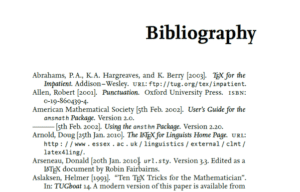

How to Write a Bibliography for a Research Paper?

First, let us make it clear that bibliography and works cited are two different things. Works cited are those that you cited in your paper. Bibliography should include all the materials you used to do your research. Still, remember that bibliography requirements differ depending on the formatting style of your paper. For this reason, make sure you ask you professor all the requirements you need to meet to avoid any misunderstanding.

Learn how to write a bibliography for a research paper .

The Key Secret to a Good Research Paper

Now when you know all the stages of writing a research paper, you are ready to find the key to a good research paper:

- Choose the topic that really interests you

- Make the topic interesting for you even if it is not at the beginning

- Follow the step by step guide and do not get sidetracked

- Be persistent and believe in yourself

- Really do research and write your paper from scratch

- Learn the convincing writing techniques and use them

- Follow the requirements of your assignment

- Ask for help if needed from real professionals

Feeling more confident about your paper now? We are sure you do. Still, if you need help, you can always rely on us 24/7.

We hope we have made writing a research paper much easier for you. We realize that it requires lots of time and energy. We believe when you say that you cannot handle it anymore. For this reason, we have been helping students like you for years. Our professional team of writers is ready to tackle any challenge.

All our authors are experienced writers crafting excellent academic papers. We help students meet the deadline and get the top grades they want. You can see everything yourself. All you need to do is to place your order online and we will contact you. Writing a research paper with us is truly easy, so why do not you check it yourself?

Additional Resources for Research Paper Writing:

- Anthropology Research

- Career Research

- Communication Research

- Criminal Justice Research

- Health Research

- Political Science Research

- Psychology Research

- Sociology Research

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to start your research paper [step-by-step guide]

1. Choose your topic

2. find information on your topic, 3. create a thesis statement, 4. create a research paper outline, 5. organize your notes, 6. write your introduction, 7. write your first draft of the body, 9. write your conclusion, 10. revise again, edit, and proofread, frequently asked questions about starting your research paper, related articles.

Research papers can be short or in-depth, but no matter what type of research paper, they all follow pretty much the same pattern and have the same structure .

A research paper is a paper that makes an argument about a topic based on research and analysis.

There will be some basic differences, but if you can write one type of research paper, you can write another. Below is a step-by-step guide to starting and completing your research paper.

Choose a topic that interests you. Writing your research paper will be so much more pleasant with a topic that you actually want to know more about. Your interest will show in the way you write and effort you put into the paper. Consider these issues when coming up with a topic:

- make sure your topic is not too broad

- narrow it down if you're using terms that are too general

Academic search engines are a great source to find background information on your topic. Your institution's library will most likely provide access to plenty of online research databases. Take a look at our guide on how to efficiently search online databases for academic research to learn how to gather all the information needed on your topic.

Tip: If you’re struggling with finding research, consider meeting with an academic librarian to help you come up with more balanced keywords.

If you’re struggling to find a topic for your thesis, take a look at our guide on how to come up with a thesis topic .

The thesis statement is one of the most important elements of any piece of academic writing. It can be defined as a very brief statement of what the main point or central message of your paper is. Our thesis statement guide will help you write an excellent thesis statement.

In the next step, you need to create your research paper outline . The outline is the skeleton of your research paper. Simply start by writing down your thesis and the main ideas you wish to present. This will likely change as your research progresses; therefore, do not worry about being too specific in the early stages of writing your outline.

Then, fill out your outline with the following components:

- the main ideas that you want to cover in the paper

- the types of evidence that you will use to support your argument

- quotes from secondary sources that you may want to use

Organizing all the information you have gathered according to your outline will help you later on in the writing process. Analyze your notes, check for accuracy, verify the information, and make sure you understand all the information you have gathered in a way that you can communicate your findings effectively.

Start with the introduction. It will set the direction of your paper and help you a lot as you write. Waiting to write it at the end can leave you with a poorly written setup to an otherwise well-written paper.

The body of your paper argues, explains or describes your topic. Start with the first topic from your outline. Ideally, you have organized your notes in a way that you can work through your research paper outline and have all the notes ready.

After your first draft, take some time to check the paper for content errors. Rearrange ideas, make changes and check if the order of your paragraphs makes sense. At this point, it is helpful to re-read the research paper guidelines and make sure you have followed the format requirements. You can also use free grammar and proof reading checkers such as Grammarly .

Tip: Consider reading your paper from back to front when you undertake your initial revision. This will help you ensure that your argument and organization are sound.

Write your conclusion last and avoid including any new information that has not already been presented in the body of the paper. Your conclusion should wrap up your paper and show that your research question has been answered.

Allow a few days to pass after you finished writing the final draft of your research paper, and then start making your final corrections. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill gives some great advice here on how to revise, edit, and proofread your paper.

Tip: Take a break from your paper before you start your final revisions. Then, you’ll be able to approach your paper with fresh eyes.

As part of your final revision, be sure to check that you’ve cited everything correctly and that you have a full bibliography. Use a reference manager like Paperpile to organize your research and to create accurate citations.

The first step to start writing a research paper is to choose a topic. Make sure your topic is not too broad; narrow it down if you're using terms that are too general.

The format of your research paper will vary depending on the journal you submit to. Make sure to check first which citation style does the journal follow, in order to format your paper accordingly. Check Getting started with your research paper outline to have an idea of what a research paper looks like.

The last step of your research paper should be proofreading. Allow a few days to pass after you finished writing the final draft of your research paper, and then start making your final corrections. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill gives some great advice here on how to revise, edit and proofread your paper.

There are plenty of software you can use to write a research paper. We recommend our own citation software, Paperpile , as well as grammar and proof reading checkers such as Grammarly .

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you’re on board with our cookie policy

- A Research Guide

- Research Paper Guide

Research Paper Body Paragraph Structure

Introduction.

- Referrences

- Ways to start paragraph

- Step by step guide

- Research paragraph examples

Learning the basics of a paragraph structure

- Title (cover page).

- Introduction.

- Literature review.

- Research methodology.

- Data analysis.

- Conclusion.

- Reference page.

5 winning ways to start a body paragraph

- Topic Sentence : it should provide a clear focus and introduce the specific aspect you will discuss. For example, “One key factor influencing climate change is…”.

- Opening Statement: grab your readers’ attention with a thought-provoking or surprising statement related to your topic. For instance, “The alarming increase in global temperatures has reached a critical point, demanding immediate action.”

- Quotation: find a relevant quote from a reputable source. It won’t only add credibility to your research but will also engage the reader right from the start.

- Anecdote or example: start your academic paragraph with a funny story or a real-world example that illustrates the significance of your research topic.

- Background information : provide a brief background or context for the topic you are about to discuss. For example, “In recent years, the prevalence of cyber-attacks has skyrocketed, posing a severe threat to individuals, organizations, and even national security.”

A step-by-step guide to starting a concise body paragraph

Step 1: introduce the main point or argument., step 2: provide evidence or examples., step 3: explain and analyze., step 4: connect to the main argument., step 5: review and revise., flawless body paragraph example: how does it look.

- Topic Sentence: Rising global temperatures have significant implications for ecosystems and biodiversity.

- Evidence/Example 1: According to a study by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), global average temperatures have increased by 1.1 degrees Celsius since pre-industrial times (IPCC, 2021). This temperature rise has led to melting polar ice caps and glaciers, rising sea levels, and coastal erosion (Smith et al., 2019).

- Explanation/Analysis 1: The significant increase in global temperatures has caused observable changes in the Earth’s physical environment. The melting of polar ice caps not only contributes to the rise in sea levels but also disrupts marine ecosystems.

- Evidence/Example 2: In addition to the loss of coastal habitats, higher temperatures have also resulted in shifts in the geographical distribution of species. Research by Parmesan and Yohe (2019) indicates that many plant and animal species have altered their ranges and migration patterns in response to changing climate conditions.

- Explanation/Analysis 2: The observed shifts in species distribution highlight the vulnerability of ecosystems to climate change. As temperature zone modification, species that cannot adapt or migrate to suitable habitats may face reduced reproductive success and increased risk of extinction.

- Connect to the main argument: These examples demonstrate that the rising global temperatures associated with climate change have profound implications for ecosystems and biodiversity.

The bottom line

- Writing a Research Paper

- Research Paper Title

- Research Paper Sources

- Research Paper Problem Statement

- Research Paper Thesis Statement

- Hypothesis for a Research Paper

- Research Question

- Research Paper Outline

- Research Paper Summary

- Research Paper Prospectus

- Research Paper Proposal

- Research Paper Format

- Research Paper Styles

- AMA Style Research Paper

- MLA Style Research Paper

- Chicago Style Research Paper

- APA Style Research Paper

- Research Paper Structure

- Research Paper Cover Page

- Research Paper Abstract

- Research Paper Introduction

- Research Paper Body Paragraph

- Research Paper Literature Review

- Research Paper Background

- Research Paper Methods Section

- Research Paper Results Section

- Research Paper Discussion Section

- Research Paper Conclusion

- Research Paper Appendix

- Research Paper Bibliography

- APA Reference Page

- Annotated Bibliography

- Bibliography vs Works Cited vs References Page

- Research Paper Types

- What is Qualitative Research

Receive paper in 3 Hours!

- Choose the number of pages.

- Select your deadline.

- Complete your order.

Number of Pages

550 words (double spaced)

Deadline: 10 days left

By clicking "Log In", you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We'll occasionally send you account related and promo emails.

Sign Up for your FREE account

Get a 50% off

Study smarter with Chegg and save your time and money today!

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Paper

Definition:

Research Paper is a written document that presents the author’s original research, analysis, and interpretation of a specific topic or issue.

It is typically based on Empirical Evidence, and may involve qualitative or quantitative research methods, or a combination of both. The purpose of a research paper is to contribute new knowledge or insights to a particular field of study, and to demonstrate the author’s understanding of the existing literature and theories related to the topic.

Structure of Research Paper

The structure of a research paper typically follows a standard format, consisting of several sections that convey specific information about the research study. The following is a detailed explanation of the structure of a research paper:

The title page contains the title of the paper, the name(s) of the author(s), and the affiliation(s) of the author(s). It also includes the date of submission and possibly, the name of the journal or conference where the paper is to be published.

The abstract is a brief summary of the research paper, typically ranging from 100 to 250 words. It should include the research question, the methods used, the key findings, and the implications of the results. The abstract should be written in a concise and clear manner to allow readers to quickly grasp the essence of the research.

Introduction

The introduction section of a research paper provides background information about the research problem, the research question, and the research objectives. It also outlines the significance of the research, the research gap that it aims to fill, and the approach taken to address the research question. Finally, the introduction section ends with a clear statement of the research hypothesis or research question.

Literature Review

The literature review section of a research paper provides an overview of the existing literature on the topic of study. It includes a critical analysis and synthesis of the literature, highlighting the key concepts, themes, and debates. The literature review should also demonstrate the research gap and how the current study seeks to address it.

The methods section of a research paper describes the research design, the sample selection, the data collection and analysis procedures, and the statistical methods used to analyze the data. This section should provide sufficient detail for other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the research, using tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data. The findings should be presented in a clear and concise manner, with reference to the research question and hypothesis.

The discussion section of a research paper interprets the findings and discusses their implications for the research question, the literature review, and the field of study. It should also address the limitations of the study and suggest future research directions.

The conclusion section summarizes the main findings of the study, restates the research question and hypothesis, and provides a final reflection on the significance of the research.

The references section provides a list of all the sources cited in the paper, following a specific citation style such as APA, MLA or Chicago.

How to Write Research Paper

You can write Research Paper by the following guide:

- Choose a Topic: The first step is to select a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. Brainstorm ideas and narrow down to a research question that is specific and researchable.

- Conduct a Literature Review: The literature review helps you identify the gap in the existing research and provides a basis for your research question. It also helps you to develop a theoretical framework and research hypothesis.

- Develop a Thesis Statement : The thesis statement is the main argument of your research paper. It should be clear, concise and specific to your research question.

- Plan your Research: Develop a research plan that outlines the methods, data sources, and data analysis procedures. This will help you to collect and analyze data effectively.

- Collect and Analyze Data: Collect data using various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. Analyze data using statistical tools or other qualitative methods.

- Organize your Paper : Organize your paper into sections such as Introduction, Literature Review, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion. Ensure that each section is coherent and follows a logical flow.

- Write your Paper : Start by writing the introduction, followed by the literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. Ensure that your writing is clear, concise, and follows the required formatting and citation styles.

- Edit and Proofread your Paper: Review your paper for grammar and spelling errors, and ensure that it is well-structured and easy to read. Ask someone else to review your paper to get feedback and suggestions for improvement.

- Cite your Sources: Ensure that you properly cite all sources used in your research paper. This is essential for giving credit to the original authors and avoiding plagiarism.

Research Paper Example

Note : The below example research paper is for illustrative purposes only and is not an actual research paper. Actual research papers may have different structures, contents, and formats depending on the field of study, research question, data collection and analysis methods, and other factors. Students should always consult with their professors or supervisors for specific guidelines and expectations for their research papers.

Research Paper Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health among Young Adults

Abstract: This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults. A literature review was conducted to examine the existing research on the topic. A survey was then administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Introduction: Social media has become an integral part of modern life, particularly among young adults. While social media has many benefits, including increased communication and social connectivity, it has also been associated with negative outcomes, such as addiction, cyberbullying, and mental health problems. This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults.

Literature Review: The literature review highlights the existing research on the impact of social media use on mental health. The review shows that social media use is associated with depression, anxiety, stress, and other mental health problems. The review also identifies the factors that contribute to the negative impact of social media, including social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Methods : A survey was administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The survey included questions on social media use, mental health status (measured using the DASS-21), and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and regression analysis.

Results : The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Discussion : The study’s findings suggest that social media use has a negative impact on the mental health of young adults. The study highlights the need for interventions that address the factors contributing to the negative impact of social media, such as social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Conclusion : In conclusion, social media use has a significant impact on the mental health of young adults. The study’s findings underscore the need for interventions that promote healthy social media use and address the negative outcomes associated with social media use. Future research can explore the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health. Additionally, longitudinal studies can investigate the long-term effects of social media use on mental health.

Limitations : The study has some limitations, including the use of self-report measures and a cross-sectional design. The use of self-report measures may result in biased responses, and a cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality.

Implications: The study’s findings have implications for mental health professionals, educators, and policymakers. Mental health professionals can use the findings to develop interventions that address the negative impact of social media use on mental health. Educators can incorporate social media literacy into their curriculum to promote healthy social media use among young adults. Policymakers can use the findings to develop policies that protect young adults from the negative outcomes associated with social media use.

References :

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive medicine reports, 15, 100918.

- Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., … & James, A. E. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among US young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 1-9.

- Van der Meer, T. G., & Verhoeven, J. W. (2017). Social media and its impact on academic performance of students. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 16, 383-398.

Appendix : The survey used in this study is provided below.

Social Media and Mental Health Survey

- How often do you use social media per day?

- Less than 30 minutes

- 30 minutes to 1 hour

- 1 to 2 hours

- 2 to 4 hours

- More than 4 hours

- Which social media platforms do you use?

- Others (Please specify)

- How often do you experience the following on social media?

- Social comparison (comparing yourself to others)

- Cyberbullying

- Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

- Have you ever experienced any of the following mental health problems in the past month?

- Do you think social media use has a positive or negative impact on your mental health?

- Very positive

- Somewhat positive

- Somewhat negative

- Very negative

- In your opinion, which factors contribute to the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Social comparison

- In your opinion, what interventions could be effective in reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Education on healthy social media use

- Counseling for mental health problems caused by social media

- Social media detox programs

- Regulation of social media use

Thank you for your participation!

Applications of Research Paper

Research papers have several applications in various fields, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research papers contribute to the advancement of knowledge by generating new insights, theories, and findings that can inform future research and practice. They help to answer important questions, clarify existing knowledge, and identify areas that require further investigation.

- Informing policy: Research papers can inform policy decisions by providing evidence-based recommendations for policymakers. They can help to identify gaps in current policies, evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, and inform the development of new policies and regulations.

- Improving practice: Research papers can improve practice by providing evidence-based guidance for professionals in various fields, including medicine, education, business, and psychology. They can inform the development of best practices, guidelines, and standards of care that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- Educating students : Research papers are often used as teaching tools in universities and colleges to educate students about research methods, data analysis, and academic writing. They help students to develop critical thinking skills, research skills, and communication skills that are essential for success in many careers.

- Fostering collaboration: Research papers can foster collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and policymakers by providing a platform for sharing knowledge and ideas. They can facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations and partnerships that can lead to innovative solutions to complex problems.

When to Write Research Paper

Research papers are typically written when a person has completed a research project or when they have conducted a study and have obtained data or findings that they want to share with the academic or professional community. Research papers are usually written in academic settings, such as universities, but they can also be written in professional settings, such as research organizations, government agencies, or private companies.

Here are some common situations where a person might need to write a research paper:

- For academic purposes: Students in universities and colleges are often required to write research papers as part of their coursework, particularly in the social sciences, natural sciences, and humanities. Writing research papers helps students to develop research skills, critical thinking skills, and academic writing skills.

- For publication: Researchers often write research papers to publish their findings in academic journals or to present their work at academic conferences. Publishing research papers is an important way to disseminate research findings to the academic community and to establish oneself as an expert in a particular field.

- To inform policy or practice : Researchers may write research papers to inform policy decisions or to improve practice in various fields. Research findings can be used to inform the development of policies, guidelines, and best practices that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- To share new insights or ideas: Researchers may write research papers to share new insights or ideas with the academic or professional community. They may present new theories, propose new research methods, or challenge existing paradigms in their field.

Purpose of Research Paper

The purpose of a research paper is to present the results of a study or investigation in a clear, concise, and structured manner. Research papers are written to communicate new knowledge, ideas, or findings to a specific audience, such as researchers, scholars, practitioners, or policymakers. The primary purposes of a research paper are:

- To contribute to the body of knowledge : Research papers aim to add new knowledge or insights to a particular field or discipline. They do this by reporting the results of empirical studies, reviewing and synthesizing existing literature, proposing new theories, or providing new perspectives on a topic.

- To inform or persuade: Research papers are written to inform or persuade the reader about a particular issue, topic, or phenomenon. They present evidence and arguments to support their claims and seek to persuade the reader of the validity of their findings or recommendations.

- To advance the field: Research papers seek to advance the field or discipline by identifying gaps in knowledge, proposing new research questions or approaches, or challenging existing assumptions or paradigms. They aim to contribute to ongoing debates and discussions within a field and to stimulate further research and inquiry.

- To demonstrate research skills: Research papers demonstrate the author’s research skills, including their ability to design and conduct a study, collect and analyze data, and interpret and communicate findings. They also demonstrate the author’s ability to critically evaluate existing literature, synthesize information from multiple sources, and write in a clear and structured manner.

Characteristics of Research Paper

Research papers have several characteristics that distinguish them from other forms of academic or professional writing. Here are some common characteristics of research papers:

- Evidence-based: Research papers are based on empirical evidence, which is collected through rigorous research methods such as experiments, surveys, observations, or interviews. They rely on objective data and facts to support their claims and conclusions.

- Structured and organized: Research papers have a clear and logical structure, with sections such as introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. They are organized in a way that helps the reader to follow the argument and understand the findings.

- Formal and objective: Research papers are written in a formal and objective tone, with an emphasis on clarity, precision, and accuracy. They avoid subjective language or personal opinions and instead rely on objective data and analysis to support their arguments.

- Citations and references: Research papers include citations and references to acknowledge the sources of information and ideas used in the paper. They use a specific citation style, such as APA, MLA, or Chicago, to ensure consistency and accuracy.

- Peer-reviewed: Research papers are often peer-reviewed, which means they are evaluated by other experts in the field before they are published. Peer-review ensures that the research is of high quality, meets ethical standards, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- Objective and unbiased: Research papers strive to be objective and unbiased in their presentation of the findings. They avoid personal biases or preconceptions and instead rely on the data and analysis to draw conclusions.

Advantages of Research Paper

Research papers have many advantages, both for the individual researcher and for the broader academic and professional community. Here are some advantages of research papers:

- Contribution to knowledge: Research papers contribute to the body of knowledge in a particular field or discipline. They add new information, insights, and perspectives to existing literature and help advance the understanding of a particular phenomenon or issue.

- Opportunity for intellectual growth: Research papers provide an opportunity for intellectual growth for the researcher. They require critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity, which can help develop the researcher’s skills and knowledge.

- Career advancement: Research papers can help advance the researcher’s career by demonstrating their expertise and contributions to the field. They can also lead to new research opportunities, collaborations, and funding.

- Academic recognition: Research papers can lead to academic recognition in the form of awards, grants, or invitations to speak at conferences or events. They can also contribute to the researcher’s reputation and standing in the field.

- Impact on policy and practice: Research papers can have a significant impact on policy and practice. They can inform policy decisions, guide practice, and lead to changes in laws, regulations, or procedures.

- Advancement of society: Research papers can contribute to the advancement of society by addressing important issues, identifying solutions to problems, and promoting social justice and equality.

Limitations of Research Paper

Research papers also have some limitations that should be considered when interpreting their findings or implications. Here are some common limitations of research papers:

- Limited generalizability: Research findings may not be generalizable to other populations, settings, or contexts. Studies often use specific samples or conditions that may not reflect the broader population or real-world situations.

- Potential for bias : Research papers may be biased due to factors such as sample selection, measurement errors, or researcher biases. It is important to evaluate the quality of the research design and methods used to ensure that the findings are valid and reliable.

- Ethical concerns: Research papers may raise ethical concerns, such as the use of vulnerable populations or invasive procedures. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines and obtain informed consent from participants to ensure that the research is conducted in a responsible and respectful manner.

- Limitations of methodology: Research papers may be limited by the methodology used to collect and analyze data. For example, certain research methods may not capture the complexity or nuance of a particular phenomenon, or may not be appropriate for certain research questions.

- Publication bias: Research papers may be subject to publication bias, where positive or significant findings are more likely to be published than negative or non-significant findings. This can skew the overall findings of a particular area of research.

- Time and resource constraints: Research papers may be limited by time and resource constraints, which can affect the quality and scope of the research. Researchers may not have access to certain data or resources, or may be unable to conduct long-term studies due to practical limitations.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

How to Write a Research Paper

#scribendiinc

The research paper writing process

In the first article of this two part series, we discussed how to research a term paper . In this article, we will discuss how to write a term or research paper.

Write your thesis statement

After you have spent some time finding your sources and absorbing the information, you should then be able to come up with a thesis statement that tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter. This statement is a road map for the research paper, telling the reader what to expect. It usually consists of a single sentence somewhere in your first paragraph and makes a claim that others might later dispute!

For optimal organization, take the time to write an outline that indicates the main aspects to be discussed. This includes deciding on the order of your sub-topics and which key points you will use as evidence to support your position.

Keep the body of your research paper in good shape

The body is the largest part of a research paper; in it you collect and arrange evidence that will persuade the reader of your argument. It should, therefore, have a logical organization. If the paper is long, it is a good idea to partition the body into sections using headings and sub-headings. This includes using parenthetical citations when referencing another author's work in the body of your text.

Sometimes the beginning isn't the best place to start...

Write the introduction and conclusion of your research paper last in order to ensure accuracy. The introduction is the key to letting your readers know where you are headed and what you hope to accomplish. Remember that while the organization of your research paper may be clear to you, it may not necessarily be clear to your readers. Therefore, the introduction should acquaint them with the journey ahead, making it easier for them to understand what follows and helping to improve their evaluation of your work. Tell your readers in concise terms what the subject of the paper is, what it is that you hope to find out, and how you will go about doing so.

Encapsulating your findings in the conclusion is not the only place in the research paper where you make your voice heard. Your analysis should appear throughout. A common ESL mistake is reciting facts in the body of their essay and then waiting until the conclusion to say what they mean. Good research papers bring data, events, and other material together, interpreting the facts throughout. The conclusion should summarize what you have said in the body and should stress the evidence that supports your analysis.

Don't forget your references

Once your research paper is finished, compile your reference list. This is an alphabetical listing of all the sources you referenced in the body of your paper. If you made notes about your sources, this task should be straightforward. Be sure to follow whatever style guide your professor or school recommends. We have an example APA Reference page and an example MLA Works Cited for your reference.

Edit your research paper to ensure clarity

Once you have the pieces of your research paper in place, it's time to polish, polish, polish! Double-check everything. Ensure you have correctly cited your sources, checked your spelling and grammar, and re-read your paper several times, checking for sense, logical structure, and organization. Readers will judge your paper not only on the quality of research, but also on the quality of the writing.

Ta da! You've done it—your research paper is complete! Just think about what you've learned: not just about your subject, but about the whole investigative process.

Image source: Patrik Goethe/Stocksnap.io

Perfect Your Paper Prior to Submission

Hire an expert academic editor , or get a free sample.

Have You Read?

"The Complete Beginner's Guide to Academic Writing"

Related Posts

Essay Writing: Traffic Signals for the Reader

How to Research a Term Paper

How to Write a Great Thesis Statement

Upload your file(s) so we can calculate your word count, or enter your word count manually.

We will also recommend a service based on the file(s) you upload.

English is not my first language. I need English editing and proofreading so that I sound like a native speaker.

I need to have my journal article, dissertation, or term paper edited and proofread, or I need help with an admissions essay or proposal.

I have a novel, manuscript, play, or ebook. I need editing, copy editing, proofreading, a critique of my work, or a query package.

I need editing and proofreading for my white papers, reports, manuals, press releases, marketing materials, and other business documents.

I need to have my essay, project, assignment, or term paper edited and proofread.

I want to sound professional and to get hired. I have a resume, letter, email, or personal document that I need to have edited and proofread.

Prices include your personal % discount.

Prices include % sales tax ( ).

- Research guides

Writing an Educational Research Paper

Research paper sections, customary parts of an education research paper.

There is no one right style or manner for writing an education paper. Content aside, the writing style and presentation of papers in different educational fields vary greatly. Nevertheless, certain parts are common to most papers, for example:

Title/Cover Page

Contains the paper's title, the author's name, address, phone number, e-mail, and the day's date.

Not every education paper requires an abstract. However, for longer, more complex papers abstracts are particularly useful. Often only 100 to 300 words, the abstract generally provides a broad overview and is never more than a page. It describes the essence, the main theme of the paper. It includes the research question posed, its significance, the methodology, and the main results or findings. Footnotes or cited works are never listed in an abstract. Remember to take great care in composing the abstract. It's the first part of the paper the instructor reads. It must impress with a strong content, good style, and general aesthetic appeal. Never write it hastily or carelessly.

Introduction and Statement of the Problem

A good introduction states the main research problem and thesis argument. What precisely are you studying and why is it important? How original is it? Will it fill a gap in other studies? Never provide a lengthy justification for your topic before it has been explicitly stated.

Limitations of Study

Indicate as soon as possible what you intend to do, and what you are not going to attempt. You may limit the scope of your paper by any number of factors, for example, time, personnel, gender, age, geographic location, nationality, and so on.

Methodology

Discuss your research methodology. Did you employ qualitative or quantitative research methods? Did you administer a questionnaire or interview people? Any field research conducted? How did you collect data? Did you utilize other libraries or archives? And so on.

Literature Review

The research process uncovers what other writers have written about your topic. Your education paper should include a discussion or review of what is known about the subject and how that knowledge was acquired. Once you provide the general and specific context of the existing knowledge, then you yourself can build on others' research. The guide Writing a Literature Review will be helpful here.

Main Body of Paper/Argument

This is generally the longest part of the paper. It's where the author supports the thesis and builds the argument. It contains most of the citations and analysis. This section should focus on a rational development of the thesis with clear reasoning and solid argumentation at all points. A clear focus, avoiding meaningless digressions, provides the essential unity that characterizes a strong education paper.

After spending a great deal of time and energy introducing and arguing the points in the main body of the paper, the conclusion brings everything together and underscores what it all means. A stimulating and informative conclusion leaves the reader informed and well-satisfied. A conclusion that makes sense, when read independently from the rest of the paper, will win praise.

Works Cited/Bibliography

See the Citation guide .

Education research papers often contain one or more appendices. An appendix contains material that is appropriate for enlarging the reader's understanding, but that does not fit very well into the main body of the paper. Such material might include tables, charts, summaries, questionnaires, interview questions, lengthy statistics, maps, pictures, photographs, lists of terms, glossaries, survey instruments, letters, copies of historical documents, and many other types of supplementary material. A paper may have several appendices. They are usually placed after the main body of the paper but before the bibliography or works cited section. They are usually designated by such headings as Appendix A, Appendix B, and so on.

- << Previous: Choosing a Topic

- Next: Find Books >>

- Last Updated: Dec 5, 2023 2:26 PM

- Subjects: Education

- Tags: education , education_paper , education_research_paper

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9.2 Writing Body Paragraphs

Learning objectives.

- Select primary support related to your thesis.

- Support your topic sentences.

If your thesis gives the reader a roadmap to your essay, then body paragraphs should closely follow that map. The reader should be able to predict what follows your introductory paragraph by simply reading the thesis statement.

The body paragraphs present the evidence you have gathered to confirm your thesis. Before you begin to support your thesis in the body, you must find information from a variety of sources that support and give credit to what you are trying to prove.

Select Primary Support for Your Thesis

Without primary support, your argument is not likely to be convincing. Primary support can be described as the major points you choose to expand on your thesis. It is the most important information you select to argue for your point of view. Each point you choose will be incorporated into the topic sentence for each body paragraph you write. Your primary supporting points are further supported by supporting details within the paragraphs.

Remember that a worthy argument is backed by examples. In order to construct a valid argument, good writers conduct lots of background research and take careful notes. They also talk to people knowledgeable about a topic in order to understand its implications before writing about it.

Identify the Characteristics of Good Primary Support

In order to fulfill the requirements of good primary support, the information you choose must meet the following standards:

- Be specific. The main points you make about your thesis and the examples you use to expand on those points need to be specific. Use specific examples to provide the evidence and to build upon your general ideas. These types of examples give your reader something narrow to focus on, and if used properly, they leave little doubt about your claim. General examples, while they convey the necessary information, are not nearly as compelling or useful in writing because they are too obvious and typical.

- Be relevant to the thesis. Primary support is considered strong when it relates directly to the thesis. Primary support should show, explain, or prove your main argument without delving into irrelevant details. When faced with lots of information that could be used to prove your thesis, you may think you need to include it all in your body paragraphs. But effective writers resist the temptation to lose focus. Choose your examples wisely by making sure they directly connect to your thesis.

- Be detailed. Remember that your thesis, while specific, should not be very detailed. The body paragraphs are where you develop the discussion that a thorough essay requires. Using detailed support shows readers that you have considered all the facts and chosen only the most precise details to enhance your point of view.

Prewrite to Identify Primary Supporting Points for a Thesis Statement

Recall that when you prewrite you essentially make a list of examples or reasons why you support your stance. Stemming from each point, you further provide details to support those reasons. After prewriting, you are then able to look back at the information and choose the most compelling pieces you will use in your body paragraphs.

Choose one of the following working thesis statements. On a separate sheet of paper, write for at least five minutes using one of the prewriting techniques you learned in Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .

- Unleashed dogs on city streets are a dangerous nuisance.

- Students cheat for many different reasons.

- Drug use among teens and young adults is a problem.

- The most important change that should occur at my college or university is ____________________________________________.

Select the Most Effective Primary Supporting Points for a Thesis Statement

After you have prewritten about your working thesis statement, you may have generated a lot of information, which may be edited out later. Remember that your primary support must be relevant to your thesis. Remind yourself of your main argument, and delete any ideas that do not directly relate to it. Omitting unrelated ideas ensures that you will use only the most convincing information in your body paragraphs. Choose at least three of only the most compelling points. These will serve as the topic sentences for your body paragraphs.

Refer to the previous exercise and select three of your most compelling reasons to support the thesis statement. Remember that the points you choose must be specific and relevant to the thesis. The statements you choose will be your primary support points, and you will later incorporate them into the topic sentences for the body paragraphs.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

When you support your thesis, you are revealing evidence. Evidence includes anything that can help support your stance. The following are the kinds of evidence you will encounter as you conduct your research:

- Facts. Facts are the best kind of evidence to use because they often cannot be disputed. They can support your stance by providing background information on or a solid foundation for your point of view. However, some facts may still need explanation. For example, the sentence “The most populated state in the United States is California” is a pure fact, but it may require some explanation to make it relevant to your specific argument.

- Judgments. Judgments are conclusions drawn from the given facts. Judgments are more credible than opinions because they are founded upon careful reasoning and examination of a topic.

- Testimony. Testimony consists of direct quotations from either an eyewitness or an expert witness. An eyewitness is someone who has direct experience with a subject; he adds authenticity to an argument based on facts. An expert witness is a person who has extensive experience with a topic. This person studies the facts and provides commentary based on either facts or judgments, or both. An expert witness adds authority and credibility to an argument.

- Personal observation. Personal observation is similar to testimony, but personal observation consists of your testimony. It reflects what you know to be true because you have experiences and have formed either opinions or judgments about them. For instance, if you are one of five children and your thesis states that being part of a large family is beneficial to a child’s social development, you could use your own experience to support your thesis.

Writing at Work

In any job where you devise a plan, you will need to support the steps that you lay out. This is an area in which you would incorporate primary support into your writing. Choosing only the most specific and relevant information to expand upon the steps will ensure that your plan appears well-thought-out and precise.

You can consult a vast pool of resources to gather support for your stance. Citing relevant information from reliable sources ensures that your reader will take you seriously and consider your assertions. Use any of the following sources for your essay: newspapers or news organization websites, magazines, encyclopedias, and scholarly journals, which are periodicals that address topics in a specialized field.

Choose Supporting Topic Sentences

Each body paragraph contains a topic sentence that states one aspect of your thesis and then expands upon it. Like the thesis statement, each topic sentence should be specific and supported by concrete details, facts, or explanations.

Each body paragraph should comprise the following elements.

topic sentence + supporting details (examples, reasons, or arguments)

As you read in Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” , topic sentences indicate the location and main points of the basic arguments of your essay. These sentences are vital to writing your body paragraphs because they always refer back to and support your thesis statement. Topic sentences are linked to the ideas you have introduced in your thesis, thus reminding readers what your essay is about. A paragraph without a clearly identified topic sentence may be unclear and scattered, just like an essay without a thesis statement.

Unless your teacher instructs otherwise, you should include at least three body paragraphs in your essay. A five-paragraph essay, including the introduction and conclusion, is commonly the standard for exams and essay assignments.

Consider the following the thesis statement:

Author J.D. Salinger relied primarily on his personal life and belief system as the foundation for the themes in the majority of his works.

The following topic sentence is a primary support point for the thesis. The topic sentence states exactly what the controlling idea of the paragraph is. Later, you will see the writer immediately provide support for the sentence.

Salinger, a World War II veteran, suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder, a disorder that influenced themes in many of his works.

In Note 9.19 “Exercise 2” , you chose three of your most convincing points to support the thesis statement you selected from the list. Take each point and incorporate it into a topic sentence for each body paragraph.

Supporting point 1: ____________________________________________

Topic sentence: ____________________________________________

Supporting point 2: ____________________________________________

Supporting point 3: ____________________________________________

Draft Supporting Detail Sentences for Each Primary Support Sentence

After deciding which primary support points you will use as your topic sentences, you must add details to clarify and demonstrate each of those points. These supporting details provide examples, facts, or evidence that support the topic sentence.

The writer drafts possible supporting detail sentences for each primary support sentence based on the thesis statement: