Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A Case Study and Exploration of Causes and Interventions

- First Online: 02 March 2019

Cite this chapter

- Bijal Chheda-Varma 5

3200 Accesses

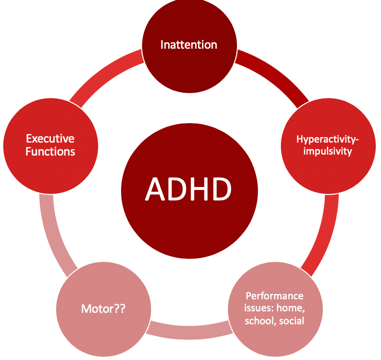

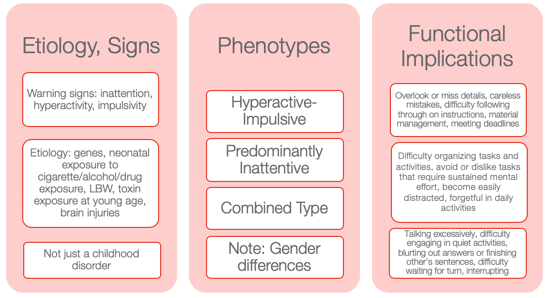

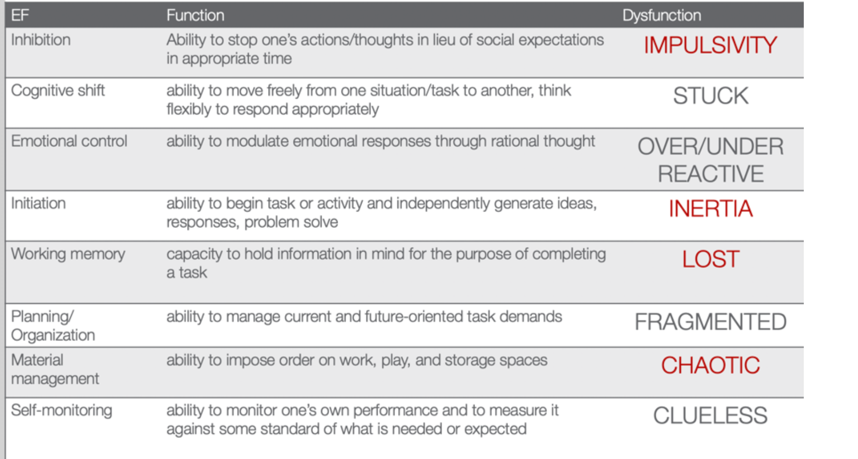

The male to female ratio of ADHD is 4:1. This chapter on ADHD provides a wide perspective on understanding, diagnosis and treatment for ADHD. It relies on a neurodevelopmental perspective of ADHD. Signs and symptoms of ADHD are described through the DSM-V criteria. A case example (K, a patient of mine) is illustrated throughout the chapter to provide context and illustrations, and demonstrates the relative merits of “doing” (i.e. behavioural interventions) compared to cognitive insight, or medication alone. Finally, a discussion of the Cognitive Behavioral Modification Model (CBM) for the treatment of ADHD provides a snapshot of interventions used by clinicians providing psychological help.

- Neuro-developmental disorders

- Behaviour modification

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Alderson, R. M., Hudec, K. L., Patros, C. H. G., & Kasper, L. J. (2013). Working memory deficits in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): An examination of central executive and storage/rehearsal processes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122 (2), 532–541. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0031742 .

Arcia, E., & Conners, C. K. (1998). Gender differences in ADHD? Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 19 (2), 77–83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004703-199804000-00002 .

Barkley, R. A. (1990). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment . New York: Guildford.

Google Scholar

Barkley, R. A. (1997). ADHD and the nature of self-control . New York: Guilford Press.

Barkley, R. A. (2000). Commentary on the multimodal treatment study of children with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 28 (6), 595–599. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005139300209 .

Article Google Scholar

Barkley, R., Knouse, L., & Murphy, K. Correction to Barkley et al. (2011). Psychological Assessment [serial online]. June 2011; 23 (2), 446. Available from: PsycINFO, Ipswich, MA. Accessed December 11, 2014.

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders . New York, NY: International Universities Press.

Brown, T. E. (2005). Attention deficit disorder: The unfocused mind in children and adults . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Brown, T. (2013). A new understanding of ADHD in children and adults . New York: Routledge.

Chacko, A., Kofler, M., & Jarrett, M. (2014). Improving outcomes for youth with ADHD: A conceptual framework for combined neurocognitive and skill-based treatment approaches. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-014-0171-5 .

Chronis, A., Jones, H. A., Raggi, V. L. (2006, August). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 26 (4), 486–502. ISSN 0272-7358. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.002 .

Curatolo, P., D’Agati, E., & Moavero, R. (2010). The neurobiological basis of ADHD. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 36 , 79. http://doi.org/10.1186/1824-7288-36-79 . http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272735806000031 .

Curtis, D. (2010). ADHD symptom severity following participation in a pilot, 10-week, manualized, family-based behavioral intervention. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 32 , 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317107.2010.500526 .

De Young, R. (2014). Using the Stroop effect to test our capacity to direct attention: A tool for navigating urgent transitions. http://www.snre.umich.edu/eplab/demos/st0/stroopdesc.html .

Depue, B. E., Orr, J. M., Smolker, H. R., Naaz, F., & Banich, M. T. (2015). The organization of right prefrontal networks reveals common mechanisms of inhibitory regulation across cognitive, emotional, and motor processes. Cerebral Cortex (New York, NY: 1991), 26 (4), 1634–1646.

D’Onofrio, B. M., Van Hulle, C. A., Waldman, I. D., Rodgers, J. L., Rathouz, P. J., & Lahey, B. B. (2007). Causal inferences regarding prenatal alcohol exposure and childhood externalizing problems. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 1296–1304 [PubMed].

DSM-V. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders . American Psychological Association.

Eisenberg, D., & Campbell, B. (2009). Social context matters. The evolution of ADHD . http://evolution.binghamton.edu/evos/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/eisenberg-and-campbell-2011-the-evolution-of-ADHD-artice-in-SF-Medicine.pdf .

Gizer, I. R., Ficks, C., & Waldman, I. D. (2009). Hum Genet, 126 , 51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-009-0694-x .

Hinshaw, S. P., & Scheffler, R. M. (2014). The ADHD explosion: Myths, medication, money, and today’s push for performance . New York: Oxford University Press.

Kapalka, G. M. (2008). Efficacy of behavioral contracting with students with ADHD . Boston: American Psychological Association.

Kapalka, G. (2010). Counselling boys and men with ADHD . New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Book Google Scholar

Knouse, L. E., et al. (2008, October). Recent developments in psychosocial treatments for adult ADHD. National Institute of Health, 8 (10), 1537–1548. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737175.8.10.1537 .

Laufer, M., Denhoff, E., & Solomons, G. (1957). Hyperkinetic impulse disorder in children’s behaviour problem. Psychosomatic Medicine, 19, 38–49.

Raggi, V. L., & Chronis, A. M. (2006). Interventions to address the academic impairment of children and adolescents with ADHD. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 9 (2), 85–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-006-0006-0 .

Ramsay, J. R. (2011). Cognitive behavioural therapy for adult ADHD. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management, 18 (11), 526–536.

Retz, W., & Retz-Junginger, P. (2014). Prediction of methylphenidate treatment outcome in adults with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience . https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-014-0542-4 .

Safren, S. A., Otto, M. W., Sprich, S., Winett, C. L., Wilens, T. E., & Biederman, J. (2005, July). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for ADHD in medication-treated adults with continued symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43 (7), 831–842. ISSN 0005-7967. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2004.07.001 . http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0005796704001366 .

Sibley, M. H., Kuriyan, A. B., Evans, S. W., Waxmonsky, J. G., & Smith, B. H. (2014). Pharmacological and psychosocial treatments for adolescents with ADHD: An updated systematic review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 34 (3), 218–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.02.001 .

Simchon, Y., Weizman, A., & Rehavi, M. (2010). The effect of chronic methylphenidate administration on presynaptic dopaminergic parameters in a rat model for ADHD. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 20 (10), 714–720. ISSN 0924-977X. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2010.04.007 . http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0924977X10000891 .

Swanson, J. M., & Castellanos, F. X. (2002). Biological bases of ADHD: Neuroanatomy, genetics, and pathophysiology. In P. S. Jensen & J. R. Cooper (Eds.), Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: State if the science, best practices (pp. 7-1–7-20). Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute.

Toplak, M. E., Connors, L., Shuster, J., Knezevic, B., & Parks, S. (2008, June). Review of cognitive, cognitive-behavioral, and neural-based interventions for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Clinical Psychology Review, 28 (5), 801–823. ISSN 0272-7358. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.008 . http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272735807001870 .

Wu, J., Xiao, H., Sun, H., Zou, L., & Zhu, L.-Q. (2012). Role of dopamine receptors in ADHD: A systematic meta-analysis. Molecular Neurobiology, 45 , 605–620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-012-8278-5 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Foundation for Clinical Interventions, London, UK

Bijal Chheda-Varma

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

UCL, London, UK

John A. Barry

Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust, Wymondham, UK

Roger Kingerlee

Change, Grow, Live, Dagenham/Southend, Essex, UK

Martin Seager

Community Interest Company, Men’s Minds Matter, London, UK

Luke Sullivan

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Chheda-Varma, B. (2019). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A Case Study and Exploration of Causes and Interventions. In: Barry, J.A., Kingerlee, R., Seager, M., Sullivan, L. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Male Psychology and Mental Health. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04384-1_15

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04384-1_15

Published : 02 March 2019

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-04383-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-04384-1

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Volume 14 Supplement 11

Current situation and challenges for mental health focused on treatment and care in Japan and the Philippines - highlights of the training program by the National Center for Global Health and Medicine

- Meeting report

- Open access

- Published: 03 August 2020

- Crystal Amiel Estrada 1 ,

- Masahide Usami 2 ,

- Naoko Satake 3 ,

- Ernesto Gregorio Jr 4 ,

- Cynthia Leynes 5 ,

- Norieta Balderrama 5 ,

- Japhet Fernandez de Leon 6 ,

- Rhodora Andrea Concepcion 7 ,

- Cecile Tuazon Timbalopez 8 ,

- Noa Tsujii 9 ,

- Ikuhiro Harada 10 ,

- Jiro Masuya 11 ,

- Hiroaki Kihara 12 ,

- Kazuhiro Kawahara 13 ,

- Yuta Yoshimura 2 ,

- Yuuki Hakoshima 2 &

- Jun Kobayashi 14

BMC Proceedings volume 14 , Article number: 11 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

194k Accesses

7 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

Background and purpose

Mental health has emerged as an important public health concern in recent years. With a high proportion of children and adolescents affected by mental disorders, it is important to ensure that they are provided with proper care and treatment. With the goal of sharing the activities and good practices on child and adolescent mental health promotion, care, and treatment in Japan and the Philippines, the National Center for Global Health and Medicine conducted a training program on the promotion of mental health focused on treatment and care in Japan and the Philippines in September and November 2019.

Key highlights

The training program comprised of a series of lectures, site visits, and round table discussions in Japan and the Philippines. The lectures and site visits focused on the current situation of child and adolescent psychiatry, diagnosis of childhood mental disorders, abuse, health financing for mental disorders, pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and disaster child psychiatry in both countries. Round table discussions provided an opportunity to explore the similarities and differences between the two countries in terms of the themes discussed during the lectures.

The training program identified the need to collaborate with other professionals to improve the diagnosis of mental disorders in children and adolescents and to increase the workforce capable of addressing mental health issues among children and adolescents. It also emphasized the importance of cooperation between government efforts during and after disasters to ensure that affected children and their families are provided with the care and support that they need.

Introduction

Current situation of mental health in the western pacific region.

Globally, an estimated 10 to 20% of children and adolescents are affected by mental health problems [ 1 ], with more than half occurring before the age of 14 [ 2 ]. In the Western Pacific Region, mental disorders rank third in the leading causes of disability-adjusted life years (DALY) among children [ 3 ] and the prevalence of suicide attempts is high [ 4 ]. Nevertheless, despite these alarming statistics, the figures may still be underreported due to stigma and taboo which affect help seeking and reporting of mental health problems.

The Mental Health Action Plan of the World Health Organization highlighted the importance of mental health promotion especially in the early stages of life [ 5 ]. Association of South East Asian Countries (ASEAN) countries have reported that mental health education towards students was focused on coping skills whereas teacher training focused on mental illness knowledge and how to provide support to students. Despite these mental health education thrusts, there is limited medical and psychological care available in schools, thus leading to an increased interest in creating an environment that can provide mental health support to students [ 6 ].

Background and aim of the training program

Mental health has emerged as an important public health concern in recent years. In the Philippines, the Philippine Mental Health Act came into force in 2019, and it is expected that the general public will be more concerned about mental health services and rights of patients and their families. However, there are only five government hospitals with psychiatric facilities for children, 84 general hospitals with psychiatric units, 46 outpatient facilities, and only 2.0 mental health professionals per 100,000 people [ 7 ].

The population of the Philippines is estimated to be at 100,981,437 [ 8 ]. Over the past 20 years, infant mortality has decreased [ 9 ] and about a third of the entire population are under 14 years old [ 10 ]. About 27% of children under 5 years are malnourished.

Children with mental health problems are also a cause of concern in the Philippines [ 11 ]. An assessment of the Philippine mental health system reported a 16% prevalence of mental disorders among children [ 12 ]. In addition, the latest Global School-based Student Health Survey found that 16.8% of students aged 13 to 17 attempted suicide one or more times during the 12 months before the survey [ 13 ]. More recent initiatives on establishing the landscape of mental health problems include a nationwide mental health survey being conducted by the Department of Health. This is the first nationwide baseline study that will establish the prevalence of mental disorders in the Philippines. The study is ongoing and the results will be made available by the end of the year.

Despite mental health problems being a cause of concern among children and adolescents in the Philippines, health facilities and human resources for mental health remain limited. Currently, there are only 60 child psychiatrists in the Philippines, with the majority practicing in urban areas such as the National Capital Region. In addition, there are only 11 inpatient and 11 outpatient facilities for children and adolescents, while only 0.28 beds in the mental hospitals are allocated for children and adolescents [ 7 ]. With the focus on mental health increasing in the Philippines, it is expected that the medical treatment and mental health promotion needs of children and adolescents in the Philippines will increase in the future.

In Japan, the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGM) shares the Japanese experience in promoting public health practices and medical technology advancement to developing countries. In conjunction with this, the Department of Psychiatry and Child and Adolescent Psychiatry of Kohnodai Hospital conducts training programs focusing on child and adolescent health. In 2017, Kohnodai Hospital co-created a training program for children’s mental health in disaster-affected areas in the Philippines [ 14 ]. Continuing its thrust on improving child and adolescent mental health, Kohnodai Hospital conducted another training program in partnership with the Philippine Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. This training focused on identifying the current situation and challenges for the promotion of mental health focused on treatment and care in Japan and the Philippines.

The objective of this training was to share the activities and good practices on child and adolescent mental health promotion, care, and treatment in Japan and the Philippines through a series of field visits and discussions. In addition, the training aimed to create a multi-institutional network for childcare such as medical care, health, education, as well as a network of medical staff of various types of occupations between the two countries.

Outline of the training program

Training content.

The current program was composed of a training in the Philippines and in Japan. The first training was conducted in Manila, Philippines from September 11 to 13, 2019 (Table 1 ). Seven Japanese mental health professionals, one social worker, and one public health researcher were dispatched to the Philippines as part of the program. The Japanese experts, engaged in providing mental health promotion, care, and management to children and adolescents, discussed with Philippine experts common mental health issues, diagnostic techniques, and practices and protocols. In addition, site visits to mental health facilities in the Philippines were conducted as part of the program.

The second training was held in Ichikawa, Japan from November 5 to 7, 2019 (Table 2 ). The participants from the Philippines - composed of four child psychiatrists and a researcher - visited government institutions providing mental health services to children and adolescents. The activities of government institutions that provide assistance related to mental health care to children and their families, including its relationship to the community, were also presented during the training.

Participants

Nine health experts from Kohnodai Hospital, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, and University of the Ryukyus and 31 participants coming from different Philippine health, academic, government, and non-government institutions attended the first training in the Philippines. The second training was attended by five Philippine health experts from the University of the Philippines Manila College of Medicine, College of Public Health, National Center for Mental Health, and the Lung Center of the Philippines. Table 3 summarizes the profile of the participants in both training programs.

Training outcome: field observations and round table discussion

Diagnosis and prevalence of mental health problems.

In Japan, increasing cases of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), futoukou (school refusal), and child abuse are issues of major concern. In the Philippines, child abuse, ADHD, and adjustment disorder were the top primary mental health diagnoses.

Similarities were identified in both countries in terms of trend, screening, and diagnosis of neurodevelopmental disorders. In Japan, a significant increase in cases of ADHD and ASD has been noted in recent years. In 1975, the rate of autism was recorded at 1 in 5000 but it was found to be at 1 in 100 in a more recent survey [ 15 ]. Likewise, the Philippines has reported an increase in cases of ASD, from 500,000 cases in 2008 to 1,000,000 in 2018 [ 16 ]. In both countries, initial identification of neurodevelopmental disorders is conducted in schools. When cases are identified, the schools refer the children to hospitals for diagnosis. However, the limited number of available CAPs poses a constraint.

Japan and the Philippines also identified suicide and gaming disorders as major social issues. In the Philippines, common circumstances which are correlated with mental health issues among youth are: too much academic pressure with great difficulty balancing time and excessive use of digital devices engaging in network gaming and social media. Excessive digital device and social media use can lead to depression, breakdown of personal connectedness, and cyberbullying. The Philippines, being one of the most active users of social media sites [ 17 ], is at risk of adolescent addiction and depression. In Japan, First Person Shooting (FPS) games are popular and may pose a dangerous threat to young children.

Psychological abuse in younger children is the most common type of abuse in Japan. Younger children experience higher rates of abuse, with most deaths due to abuse perpetrated by mothers. Neighbors were found to be the most frequent to report cases of child abuse to child counseling centers. Child abuse cases in Japan can be reported to a hotline which is available 24 h a day, 7 days a week and cases are mainly handled by the child counseling center. Currently, child counseling centers are facing difficulties in coping with rapidly increasing cases of child abuse. The number of staff in child counseling centers has increased, but the addition of child counseling centers is an urgent issue since there are few specialized hospitals that can treat children’s mental health problems such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) due to child abuse.

There are more cases of online child sexual exploitation and substance abuse in the Philippines when compared to Japan. The Philippines has been identified as one of the top sources of child pornography material [ 18 ]. While cases of antisocial behavior have been decreasing recently in Japan, the Philippines has reported that it is an emerging social issue in the country. In the Philippines, an increasing trend in sexual abuse has been observed [ 18 ]. Physical abuse is likely to be underreported because corporal punishment is a commonly accepted method of disciplining Filipino children. Psychological abuse is the least recognized and reported, even though a national baseline study found that 3 of 5 children experience it [ 19 ].

The Women and Child Protection Unit (WCPUs) provide medical and psychosocial care to abused women and children in the Philippines. Trauma-informed psychosocial processing which is based on the principle of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and other therapies are utilized to treat the children brought to the CPU. There are 106 WCPUs distributed in 55 provinces across the country providing 24 h a day, 7 days a week consultation, but there is a lack of mental health professionals in all these WCPUs. Not all WCPUs have a psychiatrist, but it has been proposed to have at least one psychiatrist or psychologist for each CPU. In the meantime, social workers are being trained to process cases being handled by the CPU to address the effects of trauma. More severe cases are referred to the psychologist or psychiatrist of the unit or other government hospitals. For example, the WCPU of the National Center for Mental Health (NCMH), established in 2010, is currently headed by a general psychiatrist with two to three psychiatry residents rotating every 3 months. Most of the cases the WCPU of the NCMH cater to are victims of sexual and physical abuse.

Both countries have identified key strategies in addressing child abuse. In Japan, the national policy focused on service-oriented strategies with three key points: 1) preventing child abuse by conducting home visits; 2) early detection through a regional council for child abuse and child consultation center; and 3) by protection and independent support for abused children. Meanwhile, the Philippine Plan of Action to End Violence Against Children (PPAEVAC) focused on strengthening the administrative aspect of child abuse prevention through the following strategies: development of a national database on child abuse; conduct and utilization of relevant researches on violence against children in all settings; advocacy for laws and policies relevant to violence against children; and strengthening the capacity of Local Councils for the Protection of Children (LPCs).

Schools also play a role in preventing child abuse. The Department of Education of the Philippines has issued DepEd Order no. 40 s. 2012, also known as the Child Protection Policy. This department order describes the policy and guidelines on protecting children in school from bullying, violence, exploitation, discrimination, and abuse [ 20 ]. In Japan, when cases of abuse are discovered, the school principal handles the case.

Human resources for mental health

The lack of child psychiatrists is common in both countries. In Japan, there are 361 accredited doctors by the Japan Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Association as of June 2019. The number of child and adolescent psychiatrists in Japan are fewer when compared with the US and Europe. As of this writing, there are only 60 child psychiatrists and eight fellows in training in the Philippines, with most of the child psychiatrists practicing in Manila. Compounding the severe lack of child psychiatrists in the Philippines is the decision of some child psychiatrists to practice their profession overseas. As a response to the inadequate number of child psychiatrists in both countries, pediatricians are being trained on how to deal with patients with depression or suicidal ideation or behaviors.

Child and adolescent psychiatrists in both countries also need to go through general psychiatry for three to 4 years before they can proceed to child and adolescent psychiatry (CAP). In Japan, there is no curriculum for CAP but the certification to practice as a CAP is being administered by the Japanese Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Society (JSCAP). The curriculum for the subspecialization of CAP in the Philippines is developed and administered by the Philippine Psychiatric Association (PAP) through the Philippine Society of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (PSCAP). In order to be a recognized fellow, psychiatrists must pass a written and oral examination. However, the two countries differ in terms of training programs for child and adolescent psychiatry. In Japan, there is no national training program for CAPs, while there are three training programs for CAPs in the Philippines.

There is also a lack of psychologists in both countries. There are no child psychologists in Japan but there are many adult psychologists working in the field of child psychology. The Philippines also faces the challenge of having very few child psychologists in the country.

In addition to the lack of child psychiatrists and psychologists in both countries, Japan and the Philippines also lack teachers who can teach children with special needs (SPED teachers). Japan also faces increasing cases of futoukou , or children who refuse to go to school. School refusal is a complex problem and is possibly caused by several factors such as school bullying, trauma, and relationship issues. Meanwhile, in the Philippines, teachers who encounter children with behavioral problems conduct home visits to determine what kind of support, e.g. referral, the children and their family need. Some children drop out of school due to conduct problems.

Some differences in terms of the availability of mental health workers in the school setting were also noted. In Japan, all schools have a school nurse, majority have a school counselor, and some schools even have a social worker. The guidance counselors and teachers play a major role in detecting mental health problems among students and are trained to deal with mental health issues. In contrast, most of the public schools in the Philippines have nurses assigned at the division level (i.e. one nurse provides school health services for several schools). In addition, due to a lack of guidance counselors in public schools, some schools assign a school guidance teacher. However, private schools have their own school nurse and guidance counselor.

Health financing

In Japan, the national health insurance provides 100% subsidy for inpatient and outpatient medical expenses of children below junior high school age (i.e. below 15 years old) care. After junior high school, medical expenses are partially subsidized by the government (70%) and the remaining costs will be out-of-pocket (30%). However, children sometimes need to wait for 3 months to a year to see a specialist due to the overcrowding of hospital CAP units. Financial resources from the welfare section of local governments are also available to provide support to families.

In the Philippines, majority of individuals with mental health disorders pay mostly or entirely out-of-pocket for services and medicines. However, inpatient care at government hospitals is free since the care and treatment of individuals with major mental disorders such as bipolar disorder, depression, and psychosis are covered by the national health insurance [ 7 ]. Nevertheless, the Philippine Health Insurance only reimburses the first week of confinement and it is selective about the diseases it covers. Moreover, it does not cover child mental health. Upon discharge from an inpatient facility, patients can avail of free medicines from the Department of Health’s Medicine Access Program. Patients can also apply to the Philippine Charity Sweepstakes Office (PCSO) which can cover at least 3 months’ worth of free medication provided that the medical doctor will give the medical abstract. Discounts can also be applied for persons with disability (PWDs) when they purchase medicines. Outpatient cases are not subsidized by the government and patients need to pay 100% of the cost from their own pocket.

Pharmacotherapy

The same medications for ADHD, depression, and childhood depression are available in both Japan and the Philippines. Drugs for ADHD such as methylphenidate (MPH) and atomoxetine (ATX) and drugs for ASD such as risperidone (RSP) and aripiprazole (APZ) are being used in both countries. However, more medicines are available in Japan. For example, drugs such as amphetamine, guanfacine (GXR) and lisdexamfetamine (LDX) for the treatment of ADHD and pimozide for ASD are available in Japan but not in the Philippines. Unlike Japan, the Philippines does not use psychostimulants as first line drugs for ADHD treatment.

The Philippines follows the UK National Institute for Health and Care Guidelines (NICE) Clinical Guideline for Autism management for pharmacological treatment. It also emphasizes that treatment requires multidisciplinary action. The environment may play a role why children are exhibiting challenging behaviors hence it is recommended to address environmental factors prior to recommending medication.

In contrast with the Philippines, where off-label use of medicines is not commonly practiced, the off-label use of psychotropic drugs among children in Japan is common. Almost all Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA)-approved drugs are authorized for use among children in Japan. The off-label use of antipsychotics is not associated with patient refusal of the prescription; rather, the most common factor for patient refusal of medications was the belief that antidepressant use causes more harm than good. Glucose and prolactin monitoring are infrequent in children initiated with antipsychotic therapy [ 21 ]. Concern in the use of antipsychotics in pediatric patients in Japan is also limited but there is a need for psychiatrists to routinely monitor the metabolic condition of patients. Additionally, standard educational programs and practice guidelines that provide evidence-based support to psychiatrists for prescription of psychotropic drugs are needed in Japan.

Both countries reported that a special license is needed by psychiatrists to prescribe certain stimulants such as methylphenidate. However, the prescription rate of MPH in Japan is lower than that in other countries, which may be associated with the restriction policy for prescribing stimulants in Japan.

Psychosocial intervention

Both countries employed multidisciplinary teams to manage cases. The team is composed of child psychiatrists, social workers, nurses, and occupational therapists. For child abuse cases in both Japan and the Philippines, social workers serve as case managers.

Japanese CAPs are trained on different forms of psychotherapy during their training. Trauma-focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT), adapted from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), is widely used for abused children in Japan. In the Philippines, some social workers are trained to conduct CBT-based therapy for child abuse cases.

Charging fees for psychotherapy are unclear for both countries. Psychotherapy provided by public Japanese facilities are free. In the Philippines, government hospitals with psychiatric facilities do not charge consultation fee. In some of these hospitals, there is an initial expense for the payment of a hospital ID. Expenses for laboratory examinations are paid for by the patient.

Disaster child psychiatry

In times of disasters, children experience a wide range of mental and behavioral disturbances such as sleeplessness, fear, anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder [ 22 ]. In Japan, children who were affected by the GEJE experienced long-term sleep disruption [ 23 ], with children from the affected Fukushima area exhibiting increasing numbers of suicide, child abuse, bullying, and absenteeism. Suicide risk and psychological symptoms were also observed among junior high school students 5 years after the GEJE. Children with evacuation experience and living in temporary housing had externalization symptoms. Economic disparities, the parents’ mental state and less social support may affect the children. In the Japanese experts’ experience, care for disabled children after disasters is also a challenge; children with ASD have difficulty adjusting to the crowded evacuation centers.

Evacuation centers in the Philippines are usually crowded after a disaster and this in turn, affect the mental health of the children and their family. Adding to this problem is the lack of mental health services for children in the Philippines after disasters. Due to the small number of practicing child psychiatrists in the country, adult psychiatrists have also been trained on how to deal with trauma of children after disasters and they examine child patients in some cases. Psychologists also help out during disasters. The Philippine Psychiatric Association also train people to process the trauma that children have experienced.

In the Philippines, where more than 90% of the total population identify as Christians, religion plays a major role in the social fabric and has become an important pathway for psychosocial support. Faith-based organizations have established mental health and psychosocial support services (MHPSS) especially during times of disasters, such as when Typhoon Haiyan struck in 2013 [ 24 ].

Mental health problems can impact children long after the disaster [ 25 ], hence providing mental health support is vital [ 26 ]. Following traumatic experiences such as disasters, schools, especially teachers, can play a key role in maintaining the well-being of children and adolescents [ 27 , 28 ]. Psychological first aid is described as a “ humane, supportive response to a fellow human being who is suffering and who may need support ” [ 29 ]. In Japan and the Philippines, teachers undergo training on psychological first aid (PFA) and are being trained to identify children who are traumatized. Teachers are also trained on some play sessions and storytelling they can use with the children to help them deal with their trauma. In terms of psychological preparedness, Japan does not have psychological preparedness in schools. In the Philippines, while psychological preparedness is not integrated in the curriculum, some schools conduct trainings on psychological preparedness for teachers and students alike.

Differences were also observed in terms of government response to disasters. Concerted efforts by the Japanese government facilitated an efficient response to the needs of the population affected by the disaster. The Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, which occurred in 1995, was the first disaster that focused on the need for mental health care for affected individuals. Interest in volunteer activities spiked in the aftermath of this disaster. In 2011, Kokoronokea (mental healthcare in Japanese) team provided medical support specializing psychiatry during the Great East Japan Earthquake (GEJE) and in 2013 the Disaster Psychiatric Assistance Team (DPAT) was established from this experience. The importance of providing support for carers or supporters and collaborating with educational institutions and school counselors were also vital lessons that Japan learned from the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake. In contrast, the Philippine experience during the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan in 2013 highlighted the need for better coordination among non- government organizations as well as between these organizations and the government.

The activities of the training program held in Japan and the Philippines successfully provided an opportunity to share the current situation on the care, diagnosis, and management of mental disorders in children and adolescents in the Philippines and Japan. In addition, the training program enabled Japanese and Philippine experts to identify similarities and differences and sharing of best practices between the two countries. The importance of creating partnerships with the religious sector was also highlighted. The training program is expected to create more opportunities for exchanging best practices on child and adolescent mental health promotion and care among countries in the future.

Clinical implication and recommendation

Based on the outcome of the roundtable discussions, it is recommended to collaborate with the societies of other practitioners such as pediatricians, psychologists, teachers, and social workers to improve the identification and diagnosis of mental disorders. In addition, training other practitioners in identifying cases of mental disorders among children and adolescents can help ease the lack of child and adolescent psychiatrists in both countries.

Further studies on pharmacotherapy dosages specific to Asian setting needs to be done. In addition, developing clinical guidelines and protocols at the country or regional levels for treating children with mental disorders is also recommended. A standard system for availing of psychotherapy including its payment schemes will also be beneficial to children and families who avail of these services.

Cooperation between government efforts pre, during and post disasters is necessary to ensure that affected children and their families are provided with the needed and appropriate care and support. It is also important to provide long-term support to ensure the well-being of children and adolescents. Likewise, psychosocial preparedness needs to be integrated into school and community activities to equip the population with the knowledge and skills that are needed before, during, and after a disaster.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Aripiprazole

Autism spectrum disorder

Association of South East Asian Nations

Atomoxetine

Child and adolescent psychiatry

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Disability-adjusted life years

Disaster Psychiatric Assistance Team

First Person Shooting

Great East Japan Earthquake

Japanese Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Society

Lisdexamfetamine

Local Councils for the Protection of Children

Mental Health Gap

Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Services

Methylphenidate

National Center for Global Health and Medicine

Philippine Psychiatric Association

Philippine Charity Sweepstakes Office

Psychological first aid

Philippine Plan of Action to End Violence Against Children

Philippine Society of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Persons with disability

Risperidone

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy

Women and Child Protection Unit

Child and adolescent mental health [Internet]. World Health Organization. [cited 2020 Mar 06.]. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/maternal-child/child_adolescent/en/ .

Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s world mental health survey initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6:168–76.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Baranne ML, Falissard B. Global burden of mental disorders among children aged 5–14 years. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2018;12(1):19.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Uddin R, Burton NW, Maple M, Khan SR, Khan A. Suicidal ideation, suicide planning, and suicide attempts among adolescents in 59 low-income and middle-income countries: a population-based study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019;3(4):223–33.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

World Health Organization. Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020 [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2013 [cited 2020 Mar 10]. Available from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/89966/9789241506021_eng.pdf;jsessionid=3E09FA457C31F4CAF837E14AD6FD2B18?sequence=1 .

Nishio A, Kakimoto M, Bernardo TM, Kobayashi J. Current situation and comparison of school mental health in ASEAN countries. Pediatr Int. 2020;62(4):438–43.

Mental Health Atlas 2017 Member State Profile Philippines [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2017 [cited 2020 Jan 24]. Available from https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/atlas/profiles-2017/PHL.pdf?ua=1 .

Philippine Statistics Authority. Highlights of the Philippine Population 2015 Census of Population [Internet]. Philippine Statistics Authority. 2016 [cited 2020 Mar 10]. Available from: https://psa.gov.ph/content/highlights-philippine-population-2015-census-population .

2017 National Demographic and Health Survey Key Findings [Internet]. Philippine Statistics Authority; 2017 [cited 2020 Jan 24]. Available from: http://www.psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/2017%20PHILIPPINES%20NDHS%20KEY%20FINDINGS_092518.pdf .

The World Factbook: Philippines [Internet]. Central Intelligence Agency. Central Intelligence Agency; 2018 [cited 2020 Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rp.html#field-anchor-people-and-society-population-distribution .

Cagande C. Child Mental Health in the Philippines. Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;3(1). https://doi.org/10.2174/2210676611303010003 .

WHO-AIMS Report on Mental Health System in the Philippines [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2007 [cited 2020 Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/philippines_who_aims_report.pdf .

NCDs | Global school-based student health survey (GSHS) [Internet]. World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 2019 [cited 2020 Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/gshs/PIH2015_fact_sheet.pdf .

Usami M, Lomboy MF, Satake N, Estrada CA, Kodama M, Gregorio ER Jr, Suzuki Y, Uytico RB, Molon MP, Harada I, Yamamoto K. Addressing challenges in children’s mental health in disaster-affected areas in Japan and the Philippines–highlights of the training program by the National Center for Global Health and Medicine. In: BMC proceedings; 2018. (Vol. 12, No. 14, pp. 1-8). BioMed Central.

Google Scholar

Weintraub K. Autism counts. Nature. 2011;479(7371):22.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lambatin LO. DOH6: Persons with autism rising [Internet]. PIA News. Philippine Information Agency; 2018 [cited 2020 Mar 09]. Available from: https://pia.gov.ph/news/articles/1006481 .

Pond R, Leeding G, Ryan Dubras W-DD. Digital 2020: 3.8 billion people use social media [Internet]. We Are Social. 2020 [cited 2020 Mar 10]. Available from: https://wearesocial.com/blog/2020/01/digital-2020-3-8-billion-people-use-social-media .

UNICEF Philippines. A Systematic Literature Review of the Drivers of Violence Affecting Children in the Philippines [Internet]. UNICEF Philippines; 2016 [cited 23 March 2020]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/philippines/media/506/file/National%20Baseline%20Study%20on%20Violence%20Against%20Children%20in%20the%20Philippines:%20Systematic%20literature%20review%20of%20drivers%20of%20violence%20affecting%20children%20(executive%20summary).pdf .

Council for the Welfare of Children, UNICEF Philippines. National Baseline Study on Violence Against Children: Philippines Executive Summary [Internet]. 2016 [cited 23 March 2020]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/philippines/media/491/file/National%20Baseline%20Study%20on%20Violence%20Against%20Children%20in%20the%20Philippines:%20Results%20(executive%20summary).pdf .

Department of Education. DepEd Order No. 40 s. 2012 Child Protection Policy [Internet]. Department of Education [cited 10 Mar 2020]. Available from https://www.deped.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/DO_s2012_40.pdf .

Okumura Y, Usami M, Okada T, Saito T, Negoro H, Tsujii N, Fujita J, Iida J. Glucose and prolactin monitoring in children and adolescents initiating antipsychotic therapy. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacology. 2018;28(7):454–62.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kar N. Psychological impact of disasters on children: review of assessment and interventions. World J Pediatr. 2009;5(1):5–11.

Usami M, Iwadare Y, Ushijima H, Inazaki K, Tanaka T, Kodaira M, Watanabe K, Kawahara K, Morikawa M, Kontani K, Murakami K. Did kindergarteners who experienced the great East Japan earthquake as infants develop traumatic symptoms? Series of questionnaire-based cross-sectional surveys: a concise and informative title: traumatic symptoms of kindergarteners who experienced disasters as infants. Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;44:38–44.

Psychosocial Support and Children’s Rights Resource Center (PSTCRRC) and Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Network (MHPSSN). Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Philippines: Minimal Response Matrix and Mapping: Final Report [Internet]. July 2014 [cited 2020 Jun 23]. Available from: https://www.alnap.org/system/files/content/resource/files/main/mhpss-philippines-mapping-final-version.pdf .

Kar N. Psychosocial issues following a natural disaster in a developing country: a qualitative longitudinal observational study. Int J Disaster Med. 2006;4(4):169–76.

Article Google Scholar

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Children's Mental Health & Disasters [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020 [cited 2020 Mar 09]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/childrenindisasters/features/disasters-mental-health.html .

Pfefferbaum B, Shaw JA. Practice parameter on disaster preparedness. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(11):1224–38.

Mutch C. The role of schools in disaster preparedness, response and recovery: what can we learn from the literature? Pastoral Care Educ. 2014;32(1):5–22.

Psychological first aid: Guide for field workers [Internet]. World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 2011 [cited 2020 Mar 09]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44615/9789241548205_eng.pdf?sequence=1 .

Download references

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deepest appreciation to the Philippine Society of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, National Center for Mental Health, Philippine General Hospital, Department of Education in the Philippines, Ichikawa City Education Center, Ichikawa City Child Care Support Section, and Ichikawa Child Consultation Center in Japan.

This program was funded by the International Promotion of Japan’s Healthcare Technologies and Services in 2019 conducted by the National Center for Global Health and Medicine under the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan. Publication of this article was sponsored by the National Center for Global Health and Medicine grant (30–3).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, College of Public Health University of the Philippines Manila SEAMEO TROPMED Philippines Regional Centre for Public Health, Hospital Administration, Environmental and Occupational Health, Manila, Philippines

Crystal Amiel Estrada

Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Kohnodai Hospital, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Ichikawa, Japan

Masahide Usami, Yuta Yoshimura & Yuuki Hakoshima

Department of Psychiatry, National Center Hospital of Neurology and Psychiatry, Kodaira, Japan

Naoko Satake

Department of Health Promotion and Education, College of Public Health University of the Philippines Manila, SEAMEO TROPMED Philippines Regional Centre for Public Health, Hospital Administration, Environmental and Occupational Health, Manila, Philippines

Ernesto Gregorio Jr

College of Medicine, University of the Philippines Manila, Manila, Philippines

Cynthia Leynes & Norieta Balderrama

West Visayas State University Medical Center, Iloilo, Philippines

Japhet Fernandez de Leon

Lung Center of the Philippines, Quezon City, Philippines

Rhodora Andrea Concepcion

National Center for Mental Health, Mandaluyong City, Philippines

Cecile Tuazon Timbalopez

Department of Neuropsychiatry, Kindai University Faculty of Medicine, Osakasayama, Osaka, Japan

Office of Social Work Service, Kohnodai Hospital, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Ichikawa, Japan

Ikuhiro Harada

Department of Psychiatry, Tokyo Medical University, Tokyo, Japan

Jiro Masuya

Department of Neuropsychiatry, Kanazawa Medical, Ishikawa, Japan

Hiroaki Kihara

Department of Neuropsychiatry, Faculty of Life Sciences, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan

Kazuhiro Kawahara

Department of Global Health, Graduate School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of the Ryukyus, Okinawa, Japan

Jun Kobayashi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MU, NS, YH, JK, ERG, and CL planned the training program. MU, NS, YH, IH, NT, HK, KK, NB, RAC, JFDL, and CL delivered presentations as part of the training program. All authors (CAE, MU, NS, ERG, CL, NB, JFDL, RAC, CT, NT, IH, JM, HK, KK, YY, YH, JK) participated in the field visits and roundtable discussions. CAE, UM, NS, NB, ERG, NT, RAC, CT, JFDL, NB, and CL contributed to the manuscript. All the authors had read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Masahide Usami .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Estrada, C.A., Usami, M., Satake, N. et al. Current situation and challenges for mental health focused on treatment and care in Japan and the Philippines - highlights of the training program by the National Center for Global Health and Medicine. BMC Proc 14 (Suppl 11), 11 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12919-020-00194-0

Download citation

Published : 03 August 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12919-020-00194-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental health

- Training programs

- Health promotion

- Philippines

BMC Proceedings

ISSN: 1753-6561

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Philippine E-Journals

Home ⇛ leaps: miriam college faculty research journal ⇛ vol. 25 no. 1 (2005), the education of children with adhd.

Ma. Paz A. Manaligod

Discipline: Education , Child Development , Cognitive Learning

Research studies have found that the prevalence of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) ADHD ranges from 3% -- 5% of the school-age population. Children with ADHD are more likely to develop depression or anxiety, exhibit disruptive behavior, and have poorer school performance, and more learning disabilities than do unaffected children of the same age. However, when ADHD is effectively managed, the characteristics may be used to the person’s advantage, creating a significant contrast. The design of this study, involves a descriptive survey to determine the relevant policies; existing institutional programs; and existing intervention strategies of teachers and parents. On the basis of existing educational programs, the study intends to surface an emerging model in the education of children with ADHD.

The study shows that concrete steps have been undertaken by the different educational institutions to respond to the needs of students with ADHD. These measures have been classified into four (4) models of intervention, consisting of 10 institutional programs.

The study proposes a model program that include significant elements that will ensure the educational success of students with ADHD. The emerging model emphasizes, among others an inclusive environment and an individualized educational program.

Nonetheless, the success of any educational program is anchored on the strong partnership between the school and the family. This partnership in the education of children with ADHD is a complex and continuing process that comes in different forms. Despite the modest role it presently plays in the Philippine setting, the fact remains that this partnership is very crucial in the educational success of students with ADHD.

Note: Kindly Login or Register to gain access to this article.

Share Article:

ISSN 0116-7235 (Print)

- Citation Generator

- ">Indexing metadata

- Print version

Copyright © 2024 KITE E-Learning Solutions | Exclusively distributed by CE-Logic | Terms and Conditions

- [email protected]

How Increased ADHD Awareness Benefits Filipino Society

In the pursuit of a more understanding and inclusive society, acknowledging and addressing the needs and challenges of individuals with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is crucial. The quest for increased ADHD awareness in Filipino society is not just about fostering empathy, but about dismantling misconceptions that have long shadowed the true essence of this neurodevelopmental disorder.

ADHD, characterized by a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity, transcends more than just an inability to sit still or a proclivity for distraction. It’s a complex disorder that significantly impacts the lives of individuals, their families, and the communities they interact with.

As per recent data, the prevalence of ADHD among Filipino children is around 7.7% , although the exact figure might be higher due to under-diagnosis. The significance of ADHD awareness extends from the corridors of educational institutions to the broader spectrum of social interactions and professional life.

Understanding ADHD is the first step towards creating a supportive environment for individuals to thrive despite the challenges they face due to their neurodivergence.

Understanding ADHD

What Does ADHD Entail?

Delving deeper into ADHD, the symptoms can be broadly categorized into two types: inattentiveness and hyperactivity/impulsivity. Individuals may experience challenges like difficulty in maintaining focus, being easily distracted, forgetfulness, fidgeting, restlessness, and impulsiveness. These symptoms often manifest before the age of 12 and can continue into adulthood, affecting daily functioning and quality of life.

Misconceptions and Challenges in the Philippines

The road towards understanding ADHD in the Philippines is frequently met with bumps of misconceptions. Common myths surrounding ADHD include beliefs that it’s a result of poor parenting, lack of discipline, or merely a phase that a child will outgrow.

These misconceptions, often rooted in a lack of awareness and understanding, contribute to the stigma and discrimination that individuals with ADHD might face in various facets of their lives.

In the educational sphere, children with ADHD may typically be wrongly labeled as lazy, naughty, or unintelligent. In reality, with the right support, individuals with ADHD can excel academically and in other areas of life.

Moreover, the lack of trained professionals and resources for accurate diagnosis and management of ADHD poses a significant challenge.

The ripple effect of these misconceptions and challenges underscores the dire need for increased ADHD awareness in Filipino society.

By shedding light on what ADHD truly is and debunking the myths surrounding it, a more empathetic and inclusive society can be fostered where individuals with ADHD are recognized for their potential and not defined by their disorder.

The Path to Early Diagnosis and Intervention

The journey towards understanding and supporting individuals with ADHD begins with awareness. The increased ADHD awareness in Filipino society is a stepping stone towards early diagnosis and intervention.

When ADHD is identified early , appropriate strategies and interventions can be initiated, which are instrumental in helping individuals manage their symptoms and improve their quality of life.

Fostering a Supportive Society

Awareness morphs into understanding, which in turn, cultivates a supportive environment. When society is well-informed about ADHD, the misconceptions fade away, giving rise to empathy and support.

This change in societal attitude is essential for creating conducive learning and working environments for individuals with ADHD. It also helps in alleviating the self-stigma that individuals with ADHD might experience, enabling them to seek help and thrive.

Historical Stigma Surrounding ADHD in the Philippines

The historical perspective on ADHD in the Philippines is tinted with misconceptions and lack of understanding.

Traditionally, behaviors associated with ADHD were often misattributed to lack of discipline, defiance, or merely a phase of childhood. This misinterpretation frequently led to a culture of blame, where parents or the individuals themselves were blamed for the symptoms of ADHD.

Real-life Encounters with Stigma

Let’s consider the story of Jose, a bright young boy with ADHD, who was often reprimanded by teachers for his inability to sit still or pay attention in class. His parents faced criticism from relatives and friends, who believed that stricter parenting would ‘cure’ his behaviors. These attitudes exacerbated Jose’s challenges and discouraged him from seeking help.

The Spiral of Misconceptions

The lack of ADHD awareness in the Philippines has historically perpetuated a cycle of stigma and misinformation. When society is uninformed about the true nature of ADHD, the stereotypes continue to thrive, pushing individuals with ADHD further into the shadows.

This lack of awareness not only hampers the accurate identification and management of ADHD, but also fosters a hostile environment where individuals with ADHD are misunderstood and unsupported.

Campaigns Breeding Awareness

The tide of change is gradually sweeping across the archipelago with various initiatives and campaigns aimed at increasing ADHD awareness in the Philippines . Schools, healthcare institutions, and community centers are now becoming platforms for disseminating accurate information about ADHD and its management.

Champions of Change: Organizations and Advocates

Numerous organizations and dedicated advocates are leading the charge in promoting increased ADHD awareness in Filipino society. Their relentless efforts are educating the masses and combating the prevailing stigma around ADHD.

By providing resources, organizing awareness campaigns, and fostering supportive communities, these advocates are making significant strides in transforming societal attitudes towards ADHD.

Unlocking Doors: Academic and Employment Accommodations

With the augmenting ADHD awareness, the landscape of academic and employment accommodations for individuals with ADHD is evolving. Schools are now more equipped with the knowledge and tools to support students with ADHD.

Similarly, employers are becoming more understanding and providing conducive work environments that cater to the diverse needs of their employees, including those with ADHD.

Building Bridges: Familial and Societal Understanding

The ripple effect of increased ADHD awareness in Filipino society is also felt within the familial circles. Families are now more understanding and equipped to support their loved ones with ADHD.

This enhanced understanding is the cornerstone for building a more inclusive and supportive society where individuals with ADHD can thrive without prejudice.

The Unending Journey: Sustaining ADHD Awareness

The journey towards a society that fully understands and supports individuals with ADHD is unending. The gains achieved through increased ADHD awareness need to be sustained and built upon.

Continuous efforts from all stakeholders, including government bodies, educational institutions , and the general public, are crucial for this cause.

Your Role in the Larger Picture

You, as a reader, also have a significant role to play. By participating in ADHD awareness campaigns, sharing accurate information, and supporting individuals with ADHD, you contribute to a more empathetic and understanding society.

Together, we can work towards a future where ADHD is understood, accepted, and supported in every facet of Filipino society.

Conclusion: Reflecting on the Journey

The journey through the facets of ADHD awareness in the Philippines reveals a significant narrative. The narrative of evolving societal understanding, support mechanisms, and the collective effort to foster a conducive environment for individuals with ADHD.

The key takeaway resonates with the critical role of increased ADHD awareness in Filipino society in bridging gaps and nurturing a more inclusive and supportive milieu.

A Call to Action: Be the Change

The dialogue on ADHD doesn’t end here. It continues with you, the reader. By sharing this blog and spreading the word, you become part of a larger movement.

A movement aimed at vanquishing stigma, fostering understanding, and creating a Filipino society that not only acknowledges ADHD but supports and empowers individuals affected by it.

The time to act is now. Share this blog, talk about ADHD, and let’s collectively contribute to a more informed and inclusive society.

Resources and Additional Reading

For those seeking to delve deeper into the realm of ADHD awareness and support, numerous resources are available. Here are some organizations and campaigns that are pivotal in promoting ADHD awareness in the Philippines:

- ADHD Society of the Philippines

- ADHD Awareness Month : Observed every October, it’s a concerted campaign to raise awareness, provide resources and support for individuals with ADHD and their families.

Engage with these resources, expand your understanding, and be a beacon of support and awareness in your community. Together, we can make a significant difference in the lives of individuals with ADHD in the Philippines.

Your Support is Our Strength: Join Us Today!

Our community thrives on the support and involvement of people like you. Don’t miss the chance to be part of something meaningful.

Maria Redillas

Maria is an accomplished digital marketing professional, specializing in content marketing and SEO. Her commitment to staying ahead in the industry is evidenced by her multiple certifications. She is always eager for new opportunities where she can apply her expertise and drive further growth and engagement.

No Comment! Be the first one.

Leave a reply cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

You Might Also Like

Meet Reclaim AI: The AI Assistant Protecting Your Time & Sanity

Beginner’s Guide to Figma: Master the Essentials for Efficient Design

Mangools for Beginners: Simplifying SEO

Beyond Brainstorms: Creative Applications for FigJam

Our site uses cookies. By using this site, you agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use .

Cathleen Rui Lin Lau Case Manager, Twinkle Intervention Center , Singapore

Guo Hui Xie EdD, Board-Certified Educational Therapist Special Needs Consultancy & Services, Singapore

..................................................

Education Journals

European Journal of Education Studies

European Journal Of Physical Education and Sport Science

European Journal of F oreign Language Teaching

European Journal of English Language Teaching

European Journal of Alternative Education Studies

European Journal of Open Education and E-learning Studies

European Journal of Literary Studies

European Journal of Applied Linguistics Studies

..................................................

Public Health Journals

European Journal of Public Health Studies

European Journal of Fitness, Nutrition and Sport Medicine Studies

European Journal of Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation Studies

Social Sciences Journals

European Journal of Social Sciences Studies

European Journal of Economic and Financial Research

European Journal of Management and Marketing Studies

European Journal of Human Resource Management Studies

European Journal of Political Science Studies

Literature, Language and Linguistics Journals

European Journal of Literature, Language and Linguistics Studies

European Journal of Multilingualism and Translation Studies

- Other Journals

- ##Editorial Board##

- ##Indexing and Abstracting##

- ##Author's guidelines##

- ##Covered Research Areas##

- ##Announcements##

- ##Related Journals##

- ##Manuscript Submission##

A CASE STUDY OF A CHILD WITH ATTENTION DEFICIT/HYPERACIVITY DISORDER (ADHD) AND MATHEMATICS LEARNING DIFFICULTY (MLD)

This is a case study of a male child, EE, aged 8+ years, who was described as rather disruptive in class during lesson. For past years, his parents, preschool and primary school teachers noted his challenging behavior and also complained that the child showed a strong dislike for mathematics and Chinese language – both are examinable academic subjects. As a result of the disturbing condition, EE was referred to an educational therapist at a private intervention center for a diagnostic assessment. The child was identified with Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)-Combined subtype. This aim of this paper is to discuss about the effects of ADHD on mathematics learning and how to avoid misdiagnosis or over-diagnosis of a behavioral-cum-learning disorder.

Article visualizations:

Aiken, L.R. (1972). Research on attitudes toward mathematics. Arithmetic Teacher, 19, 229-234.

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Anastopulos, A.D., Spisto, M.A., & Maher, M.C. (1994). The WISC-III freedom from distractibility factor: Its utility in identifying children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychological Assessment, 6(4), 368-371.

Brown, V.L., Cronin, M.E., & McEntire, E. (1994). Test of Mathematical Abilities (2nd ed.): Examiner’s manual. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Brown, V.L., & McEntire, E. (1984). Test of Mathematical Abilities (TOMA): A method for assessing mathematical aptitudes and attitudes. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Brummitt-Yale, J. (2017). What is diagnostic assessment? - Definition & examples. Retrieved on 15 February, 2020, from: https://study.com/academy/lesson/what-is-diagnostic-assessment-definition-examples.html.

Chia, K.H. (2008). Educating the whole child in a child with special needs: What we know and understand and what we can do. ASCD Review, 14, 25-31.

Chia, K.H. (2012). Psychogogy. Singapore: Pearson Education.

Code, W., Merchant, S., Maciejewski, W., Thomas, M., & Lo, J. (2016). The Mathematics Attitudes and Perceptions Survey: An instrument to assess expert-like views and dispositions among undergraduate mathematics students. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology (21 pages). Retrieved on 14 February, 2020, from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0020739X.2015.1133854.

Cooijmans, P. (n.d.). IQ and real-life functioning. Retrieved 15 February, 2020, from: https://paulcooijmans.com/intelligence/iq_ranges.html.

DB.net (2018) Difference between ability and skill. Retrieved on 29 December, 2019, from: http://www.differencebetween.net/language/difference-between-ability-and-skill/#ixzz5WS3m4ldH.

Dunn, W. (1999). Sensory Profile. San Antonio, CA: The Psychological Corporation.

DuPaul, G.J., Power, T.J., Anastopoulos, A.D., & Reid, R. (1998). ADHD Rating Scale IV: Checklists, norms, and clinical interpretation. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Flanagan, D.P., & McGrew, K.S. (1997). A cross-battery approach to assessing and interpreting cognitive abilities: Narrowing the gap between practice and cognitive science. In D.P. Flanagan, J. Genshaft, and P.L. Harrison (Eds.), Contemporary intellectual assessment: theories, tests, and issues (Chapter 8). New York, NY: Guilford press.

Flanagan, D.P., Ortiz, S.O., & Alfonso, V.C. (2007). Use of the cross-battery approach in the assessment of diverse individuals. In A.S. Kaufman and N.L. Kaufman (Series Eds.), Essentials of cross-battery assessment second edition (pp.146-205). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Gilliam, J.E. (2006). Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (2nd Edition). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Harrier, L.K., & DeOrnellas, K. (2005). Performance of children diagnosed with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder on selected planning and reconstitution tests. Applied Neuropsychology, 12 (2), 106-119.

Julita (2011) Difference Between ability and skill. DifferenceBetween.net. Retrieved on 23 December, 2019, from: http://www.differencebetween.net/language/difference-between-ability-and-skill/.

Kaufman, A.S. (1994). Intelligence testing with the WISC-III. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Kennedy, D. (2019). The ADHD symptoms that complicate and exacerbate a math learning disability. Retrieved on 28 December, 2019, from: https://www.additudemag.com/math-learning-disabilities-dyscalculia-adhd/?utm_source=eletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=treatment_january_2020&utm_content=010220&goal=0_d9446392d6-793865f9f5-297687009.

Kulm, G. (1980). Research on mathematics attitude. In J. Shumway (Ed.), Research in mathematics education (pp.356-387). Reston, VA: The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, Inc.

Low, K. (2016). The challenges of building math skills with ADHD. Retrieved on 12 February, 2020, from: https://www.verywellmind.com/adhd-and-math-skills-20804.

Newman, R.M. (1998). Gifted and math learning disabled. Retrieved on 16 December, 2019, from: http://www.dyscalculia.org/EDu561.html.

Newman, R.M. (1999). The dyscalculia syndrome. Retrieved on 16 December, 2019, from: http://www.dyscalculia.org/thesis.html.

Pearson, N.A., Patton, J.R., & Mruzek, D.W. (2006). Adaptive Behavior Diagnostic Scale. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Renfrew, C. (2019). Renfrew Language Scales (5th Ed.). London, UK: Routledge (Taylor & Francis).

Riccio, C.A., Cohen, M.J., Hall, J., & Ross, C.M. (1997). The third and fourth factors of the WISC-III: What they don’t measure. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 15, 27-39.

Rosenfeld, C. (2019). ADHD and math: 3 struggles for students with ADHD (and how to help). Retrieved 14 December, 2019, from: https://www.ectutoring.com/adhd-and-math.

Sandhu, I.K. (2019). The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Fourth Edition (WISC–IV). Retrieved on 19 December, 2019, from: http://www.brainy-child.com/expert/WISC_IV.shtml.

Sattler, J.M. (1982). Assessment of children's intelligence and special abilities (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Watkins, M.W., Kush, J.C., & Glutting, J.J. (1997). Discriminant and predictive validity of the WISC-III ACID profile among children with learning disabilities. Psychology in the Schools, 34, 309-319.

Wechsler, D. (2003). The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (4th ed.): Examiner’s manual, San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

Copyright © 2015 - 2023. European Journal of Special Education Research (ISSN 2501 - 2428) is a registered trademark of Open Access Publishing Group . All rights reserved.

This journal is a serial publication uniquely identified by an International Standard Serial Number ( ISSN ) serial number certificate issued by Romanian National Library ( Biblioteca Nationala a Romaniei ). All the research works are uniquely identified by a CrossRef DOI digital object identifier supplied by indexing and repository platforms.

All the research works published on this journal are meeting the Open Access Publishing requirements and can be freely accessed, shared, modified, distributed and used in educational, commercial and non-commercial purposes under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0) .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being

- v.12(sup1); 2017

ADHD: a critical update for educational professionals

Sanne te meerman.

a Department of Special Needs Education and Child Care , University of Groningen , Groningen, the Netherlands

Laura Batstra

Hans grietens, allen frances.

b Department of Psychiatry , School of Medicine, Duke University , NC, USA

A medical approach towards behavioural problems could make professionals without a medical background, like teachers and other educational professionals feel inapt. In this article, we raise six scientifically grounded considerations regarding ADHD, currently the most prevalent childhood psychiatric diagnosis. These “need to knows” show just how misguided and potentially stigmatizing current conceptualizations of unruly behaviour have become. Some examples are given of how teachers are misinformed, and alternative ways of reporting about neuropsychological research are suggested. A reinvigorated conceptual understanding of ADHD could help educational institutions to avoid the expensive outsourcing of behavioural problems that could also—and justifiably better—be framed as part of education’s primary mission of professionalized socialization.

Introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the syndromes defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). In the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ) it is described as a neuro-developmental disorder with a persistent behavioural pattern of severe inattention and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity. The behaviours must be uncharacteristic for the developmental age of the child, be manifest in different settings (for example at home and at school), have started before the age of 12, be present for at least 6 months, and interfere with social and academic performance.