Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- April 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 4 CURRENT ISSUE pp.255-346

- March 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 3 pp.171-254

- February 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 2 pp.83-170

- January 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 1 pp.1-82

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Substance Use Disorders and Addiction: Mechanisms, Trends, and Treatment Implications

- Ned H. Kalin , M.D.

Search for more papers by this author

The numbers for substance use disorders are large, and we need to pay attention to them. Data from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health ( 1 ) suggest that, over the preceding year, 20.3 million people age 12 or older had substance use disorders, and 14.8 million of these cases were attributed to alcohol. When considering other substances, the report estimated that 4.4 million individuals had a marijuana use disorder and that 2 million people suffered from an opiate use disorder. It is well known that stress is associated with an increase in the use of alcohol and other substances, and this is particularly relevant today in relation to the chronic uncertainty and distress associated with the COVID-19 pandemic along with the traumatic effects of racism and social injustice. In part related to stress, substance use disorders are highly comorbid with other psychiatric illnesses: 9.2 million adults were estimated to have a 1-year prevalence of both a mental illness and at least one substance use disorder. Although they may not necessarily meet criteria for a substance use disorder, it is well known that psychiatric patients have increased usage of alcohol, cigarettes, and other illicit substances. As an example, the survey estimated that over the preceding month, 37.2% of individuals with serious mental illnesses were cigarette smokers, compared with 16.3% of individuals without mental illnesses. Substance use frequently accompanies suicide and suicide attempts, and substance use disorders are associated with a long-term increased risk of suicide.

Addiction is the key process that underlies substance use disorders, and research using animal models and humans has revealed important insights into the neural circuits and molecules that mediate addiction. More specifically, research has shed light onto mechanisms underlying the critical components of addiction and relapse: reinforcement and reward, tolerance, withdrawal, negative affect, craving, and stress sensitization. In addition, clinical research has been instrumental in developing an evidence base for the use of pharmacological agents in the treatment of substance use disorders, which, in combination with psychosocial approaches, can provide effective treatments. However, despite the existence of therapeutic tools, relapse is common, and substance use disorders remain grossly undertreated. For example, whether at an inpatient hospital treatment facility or at a drug or alcohol rehabilitation program, it was estimated that only 11% of individuals needing treatment for substance use received appropriate care in 2018. Additionally, it is worth emphasizing that current practice frequently does not effectively integrate dual diagnosis treatment approaches, which is important because psychiatric and substance use disorders are highly comorbid. The barriers to receiving treatment are numerous and directly interact with existing health care inequities. It is imperative that as a field we overcome the obstacles to treatment, including the lack of resources at the individual level, a dearth of trained providers and appropriate treatment facilities, racial biases, and the marked stigmatization that is focused on individuals with addictions.

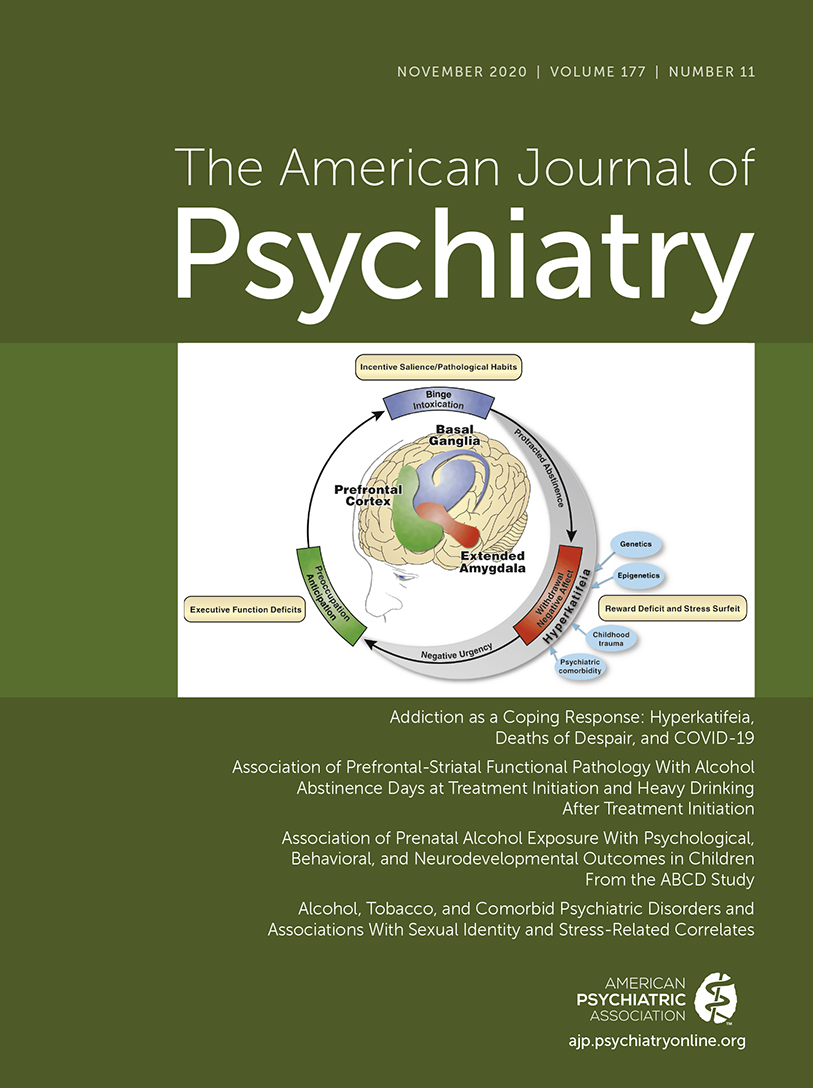

This issue of the Journal is focused on understanding factors contributing to substance use disorders and their comorbidity with psychiatric disorders, the effects of prenatal alcohol use on preadolescents, and brain mechanisms that are associated with addiction and relapse. An important theme that emerges from this issue is the necessity for understanding maladaptive substance use and its treatment in relation to health care inequities. This highlights the imperative to focus resources and treatment efforts on underprivileged and marginalized populations. The centerpiece of this issue is an overview on addiction written by Dr. George Koob, the director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), and coauthors Drs. Patricia Powell (NIAAA deputy director) and Aaron White ( 2 ). This outstanding article will serve as a foundational knowledge base for those interested in understanding the complex factors that mediate drug addiction. Of particular interest to the practice of psychiatry is the emphasis on the negative affect state “hyperkatifeia” as a major driver of addictive behavior and relapse. This places the dysphoria and psychological distress that are associated with prolonged withdrawal at the heart of treatment and underscores the importance of treating not only maladaptive drug-related behaviors but also the prolonged dysphoria and negative affect associated with addiction. It also speaks to why it is crucial to concurrently treat psychiatric comorbidities that commonly accompany substance use disorders.

Insights Into Mechanisms Related to Cocaine Addiction Using a Novel Imaging Method for Dopamine Neurons

Cassidy et al. ( 3 ) introduce a relatively new imaging technique that allows for an estimation of dopamine integrity and function in the substantia nigra, the site of origin of dopamine neurons that project to the striatum. Capitalizing on the high levels of neuromelanin that are found in substantia nigra dopamine neurons and the interaction between neuromelanin and intracellular iron, this MRI technique, termed neuromelanin-sensitive MRI (NM-MRI), shows promise in studying the involvement of substantia nigra dopamine neurons in neurodegenerative diseases and psychiatric illnesses. The authors used this technique to assess dopamine function in active cocaine users with the aim of exploring the hypothesis that cocaine use disorder is associated with blunted presynaptic striatal dopamine function that would be reflected in decreased “integrity” of the substantia nigra dopamine system. Surprisingly, NM-MRI revealed evidence for increased dopamine in the substantia nigra of individuals using cocaine. The authors suggest that this finding, in conjunction with prior work suggesting a blunted dopamine response, points to the possibility that cocaine use is associated with an altered intracellular distribution of dopamine. Specifically, the idea is that dopamine is shifted from being concentrated in releasable, functional vesicles at the synapse to a nonreleasable cytosolic pool. In addition to providing an intriguing alternative hypothesis underlying the cocaine-related alterations observed in substantia nigra dopamine function, this article highlights an innovative imaging method that can be used in further investigations involving the role of substantia nigra dopamine systems in neuropsychiatric disorders. Dr. Charles Bradberry, chief of the Preclinical Pharmacology Section at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, contributes an editorial that further explains the use of NM-MRI and discusses the theoretical implications of these unexpected findings in relation to cocaine use ( 4 ).

Treatment Implications of Understanding Brain Function During Early Abstinence in Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder

Developing a better understanding of the neural processes that are associated with substance use disorders is critical for conceptualizing improved treatment approaches. Blaine et al. ( 5 ) present neuroimaging data collected during early abstinence in patients with alcohol use disorder and link these data to relapses occurring during treatment. Of note, the findings from this study dovetail with the neural circuit schema Koob et al. provide in this issue’s overview on addiction ( 2 ). The first study in the Blaine et al. article uses 44 patients and 43 control subjects to demonstrate that patients with alcohol use disorder have a blunted neural response to the presentation of stress- and alcohol-related cues. This blunting was observed mainly in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, a key prefrontal regulatory region, as well as in subcortical regions associated with reward processing, specifically the ventral striatum. Importantly, this finding was replicated in a second study in which 69 patients were studied in relation to their length of abstinence prior to treatment and treatment outcomes. The results demonstrated that individuals with the shortest abstinence times had greater alterations in neural responses to stress and alcohol cues. The authors also found that an individual’s length of abstinence prior to treatment, independent of the number of days of abstinence, was a predictor of relapse and that the magnitude of an individual’s neural alterations predicted the amount of heavy drinking occurring early in treatment. Although relapse is an all too common outcome in patients with substance use disorders, this study highlights an approach that has the potential to refine and develop new treatments that are based on addiction- and abstinence-related brain changes. In her thoughtful editorial, Dr. Edith Sullivan from Stanford University comments on the details of the study, the value of studying patients during early abstinence, and the implications of these findings for new treatment development ( 6 ).

Relatively Low Amounts of Alcohol Intake During Pregnancy Are Associated With Subtle Neurodevelopmental Effects in Preadolescent Offspring

Excessive substance use not only affects the user and their immediate family but also has transgenerational effects that can be mediated in utero. Lees et al. ( 7 ) present data suggesting that even the consumption of relatively low amounts of alcohol by expectant mothers can affect brain development, cognition, and emotion in their offspring. The researchers used data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study, a large national community-based study, which allowed them to assess brain structure and function as well as behavioral, cognitive, and psychological outcomes in 9,719 preadolescents. The mothers of 2,518 of the subjects in this study reported some alcohol use during pregnancy, albeit at relatively low levels (0 to 80 drinks throughout pregnancy). Interestingly, and opposite of that expected in relation to data from individuals with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, increases in brain volume and surface area were found in offspring of mothers who consumed the relatively low amounts of alcohol. Notably, any prenatal alcohol exposure was associated with small but significant increases in psychological problems that included increases in separation anxiety disorder and oppositional defiant disorder. Additionally, a dose-response effect was found for internalizing psychopathology, somatic complaints, and attentional deficits. While subtle, these findings point to neurodevelopmental alterations that may be mediated by even small amounts of prenatal alcohol consumption. Drs. Clare McCormack and Catherine Monk from Columbia University contribute an editorial that provides an in-depth assessment of these findings in relation to other studies, including those assessing severe deficits in individuals with fetal alcohol syndrome ( 8 ). McCormack and Monk emphasize that the behavioral and psychological effects reported in the Lees et al. article would not be clinically meaningful. However, it is feasible that the influences of these low amounts of alcohol could interact with other predisposing factors that might lead to more substantial negative outcomes.

Increased Comorbidity Between Substance Use and Psychiatric Disorders in Sexual Identity Minorities

There is no question that victims of societal marginalization experience disproportionate adversity and stress. Evans-Polce et al. ( 9 ) focus on this concern in relation to individuals who identify as sexual minorities by comparing their incidence of comorbid substance use and psychiatric disorders with that of individuals who identify as heterosexual. By using 2012−2013 data from 36,309 participants in the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III, the authors examine the incidence of comorbid alcohol and tobacco use disorders with anxiety, mood disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The findings demonstrate increased incidences of substance use and psychiatric disorders in individuals who identified as bisexual or as gay or lesbian compared with those who identified as heterosexual. For example, a fourfold increase in the prevalence of PTSD was found in bisexual individuals compared with heterosexual individuals. In addition, the authors found an increased prevalence of substance use and psychiatric comorbidities in individuals who identified as bisexual and as gay or lesbian compared with individuals who identified as heterosexual. This was most prominent in women who identified as bisexual. For example, of the bisexual women who had an alcohol use disorder, 60.5% also had a psychiatric comorbidity, compared with 44.6% of heterosexual women. Additionally, the amount of reported sexual orientation discrimination and number of lifetime stressful events were associated with a greater likelihood of having comorbid substance use and psychiatric disorders. These findings are important but not surprising, as sexual minority individuals have a history of increased early-life trauma and throughout their lives may experience the painful and unwarranted consequences of bias and denigration. Nonetheless, these findings underscore the strong negative societal impacts experienced by minority groups and should sensitize providers to the additional needs of these individuals.

Trends in Nicotine Use and Dependence From 2001–2002 to 2012–2013

Although considerable efforts over earlier years have curbed the use of tobacco and nicotine, the use of these substances continues to be a significant public health problem. As noted above, individuals with psychiatric disorders are particularly vulnerable. Grant et al. ( 10 ) use data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions collected from a very large cohort to characterize trends in nicotine use and dependence over time. Results from their analysis support the so-called hardening hypothesis, which posits that although intervention-related reductions in nicotine use may have occurred over time, the impact of these interventions is less potent in individuals with more severe addictive behavior (i.e., nicotine dependence). When adjusted for sociodemographic factors, the results demonstrated a small but significant increase in nicotine use from 2001–2002 to 2012–2013. However, a much greater increase in nicotine dependence (46.1% to 52%) was observed over this time frame in individuals who had used nicotine during the preceding 12 months. The increases in nicotine use and dependence were associated with factors related to socioeconomic status, such as lower income and lower educational attainment. The authors interpret these findings as evidence for the hardening hypothesis, suggesting that despite the impression that nicotine use has plateaued, there is a growing number of highly dependent nicotine users who would benefit from nicotine dependence intervention programs. Dr. Kathleen Brady, from the Medical University of South Carolina, provides an editorial ( 11 ) that reviews the consequences of tobacco use and the history of the public measures that were initially taken to combat its use. Importantly, her editorial emphasizes the need to address health care inequity issues that affect individuals of lower socioeconomic status by devoting resources to develop and deploy effective smoking cessation interventions for at-risk and underresourced populations.

Conclusions

Maladaptive substance use and substance use disorders are highly prevalent and are among the most significant public health problems. Substance use is commonly comorbid with psychiatric disorders, and treatment efforts need to concurrently address both. The papers in this issue highlight new findings that are directly relevant to understanding, treating, and developing policies to better serve those afflicted with addictions. While treatments exist, the need for more effective treatments is clear, especially those focused on decreasing relapse rates. The negative affective state, hyperkatifeia, that accompanies longer-term abstinence is an important treatment target that should be emphasized in current practice as well as in new treatment development. In addition to developing a better understanding of the neurobiology of addictions and abstinence, it is necessary to ensure that there is equitable access to currently available treatments and treatment programs. Additional resources must be allocated to this cause. This depends on the recognition that health care inequities and societal barriers are major contributors to the continued high prevalence of substance use disorders, the individual suffering they inflict, and the huge toll that they incur at a societal level.

Disclosures of Editors’ financial relationships appear in the April 2020 issue of the Journal .

1 US Department of Health and Human Services: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality: National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2018. Rockville, Md, SAMHSA, 2019 ( https://www.samhsa.gov/data/nsduh/reports-detailed-tables-2018-NSDUH ) Google Scholar

2 Koob GF, Powell P, White A : Addiction as a coping response: hyperkatifeia, deaths of despair, and COVID-19 . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1031–1037 Link , Google Scholar

3 Cassidy CM, Carpenter KM, Konova AB, et al. : Evidence for dopamine abnormalities in the substantia nigra in cocaine addiction revealed by neuromelanin-sensitive MRI . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1038–1047 Link , Google Scholar

4 Bradberry CW : Neuromelanin MRI: dark substance shines a light on dopamine dysfunction and cocaine use (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1019–1021 Abstract , Google Scholar

5 Blaine SK, Wemm S, Fogelman N, et al. : Association of prefrontal-striatal functional pathology with alcohol abstinence days at treatment initiation and heavy drinking after treatment initiation . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1048–1059 Abstract , Google Scholar

6 Sullivan EV : Why timing matters in alcohol use disorder recovery (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1022–1024 Abstract , Google Scholar

7 Lees B, Mewton L, Jacobus J, et al. : Association of prenatal alcohol exposure with psychological, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental outcomes in children from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1060–1072 Link , Google Scholar

8 McCormack C, Monk C : Considering prenatal alcohol exposure in a developmental origins of health and disease framework (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1025–1028 Abstract , Google Scholar

9 Evans-Polce RJ, Kcomt L, Veliz PT, et al. : Alcohol, tobacco, and comorbid psychiatric disorders and associations with sexual identity and stress-related correlates . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1073–1081 Abstract , Google Scholar

10 Grant BF, Shmulewitz D, Compton WM : Nicotine use and DSM-IV nicotine dependence in the United States, 2001–2002 and 2012–2013 . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1082–1090 Link , Google Scholar

11 Brady KT : Social determinants of health and smoking cessation: a challenge (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1029–1030 Abstract , Google Scholar

- Cited by None

- Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders

- Addiction Psychiatry

- Transgender (LGBT) Issues

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Health Education Research

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction.

- < Previous

Understanding reasons for drug use amongst young people: a functional perspective

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Annabel Boys, John Marsden, John Strang, Understanding reasons for drug use amongst young people: a functional perspective, Health Education Research , Volume 16, Issue 4, August 2001, Pages 457–469, https://doi.org/10.1093/her/16.4.457

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This study uses a functional perspective to examine the reasons young people cite for using psychoactive substances. The study sample comprised 364 young poly-drug users recruited using snowball-sampling methods. Data on lifetime and recent frequency and intensity of use for alcohol, cannabis, amphetamines, ecstasy, LSD and cocaine are presented. A majority of the participants had used at least one of these six drugs to fulfil 11 of 18 measured substance use functions. The most popular functions for use were using to: relax (96.7%), become intoxicated (96.4%), keep awake at night while socializing (95.9%), enhance an activity (88.5%) and alleviate depressed mood (86.8%). Substance use functions were found to differ by age and gender. Recognition of the functions fulfilled by substance use should help health educators and prevention strategists to make health messages about drugs more relevant and appropriate to general and specific audiences. Targeting substances that are perceived to fulfil similar functions and addressing issues concerning the substitution of one substance for another may also strengthen education and prevention efforts.

The use of illicit psychoactive substances is not a minority activity amongst young people in the UK. Results from the most recent British Crime Survey show that some 50% of young people between the ages of 16 and 24 years have used an illicit drug on at least one occasion in their lives (lifetime prevalence) ( Ramsay and Partridge, 1999 ). Amongst 16–19 and 20–24 year olds the most prevalent drug is cannabis (used by 40% of 16–19 year olds and 47% of 20–24 year olds), followed by amphetamine sulphate (18 and 24% of the two age groups respectively), LSD (10 and 13%) and ecstasy (8 and 12%). The lifetime prevalence for cocaine hydrochloride (powder cocaine) use amongst the two age groups is 3 and 9%, respectively. Collectively, these estimates are generally comparable with other European countries ( European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 1998 ) and the US ( Johnston et al ., 1997 , 2000 ).

The widespread concern about the use of illicit drugs is reflected by its high status on health, educational and political agendas in many countries. The UK Government's 10-year national strategy on drug misuse identifies young people as a critical priority group for prevention and treatment interventions ( Tackling Drugs to Build a Better Britain 1998 ). If strategies to reduce the use of drugs and associated harms amongst the younger population are to be developed, particularly within the health education arena, it is vital that we improve our understanding of the roles that both licit and illicit substances play in the lives of young people. The tendency for educators, practitioners and policy makers to address licit drugs (such as alcohol) separately from illegal drugs may be unhelpful. This is partly because young illicit drug users frequently drink alcohol, and may have little regard for the illicit and licit distinction established by the law. To understand the roles that drug and alcohol use play in contemporary youth culture, it is necessary to examine the most frequently used psychoactive substances as a set.

It is commonplace for young drug users to use several different psychoactive substances. The terms `poly-drug' or `multiple drug' use have been used to describe this behaviour although their exact definitions vary. The term `poly-drug use' is often used to describe the use of two or more drugs during a particular time period (e.g. over the last month or year). This is the definition used within the current paper. However, poly-drug use could also characterize the use of two or more psychoactive substances so that their effects are experienced simultaneously. We have used the term `concurrent drug use' to denote this pattern of potentially more risky and harmful drug use ( Boys et al. 2000a ). Previous studies have reported that users often use drugs concurrently to improve the effects of another drug or to help manage its negative effects [e.g. ( Power et al ., 1996 ; Boys et al. 2000a ; Wibberley and Price, 2000 )].

The most recent British Crime Survey found that 5% of 16–29 year olds had used more than one drug in the last month ( Ramsay and Partridge, 1999 ). Given that 16% of this age band reported drug use in the month prior to interview, this suggests that just under a third of these individuals had used more than one illicit substance during this time period. With alcohol included, the prevalence of poly-drug use is likely to be much higher.

There is a substantial body of literature on the reasons or motivations that people cite for using alcohol, particularly amongst adult populations. For example, research on heavy drinkers suggested that alcohol use is related to multiple functions for use ( Edwards et al ., 1972 ; Sadava, 1975 ). Similarly, research with a focus on young people has sought to identify motives for illicit drug use. There is evidence that for many young people, the decision to use a drug is based on a rational appraisal process, rather than a passive reaction to the context in which a substance is available ( Boys et al. 2000a ; Wibberley and Price, 2000 ). Reported reasons vary from quite broad statements (e.g. to feel better) to more specific functions for use (e.g. to increase self-confidence). However, much of this literature focuses on `drugs' as a generic concept and makes little distinction between different types of illicit substances [e.g. ( Carman, 1979 ; Butler et al ., 1981 ; Newcomb et al ., 1988 ; Cato, 1992 ; McKay et al ., 1992 )]. Given the diverse effects that different drugs have on the user, it might be proposed that reasons for use will closely mirror these differences. Thus stimulant drugs (such as amphetamines, ecstasy or cocaine) will be used for reasons relating to increased nervous system arousal and drugs with sedative effects (such as alcohol or cannabis), with nervous system depression. The present study therefore selected a range of drugs commonly used by young people with stimulant, sedative or hallucinogenic effects to examine this issue further.

The phrase `instrumental drug use' has been used to denote drug use for reasons specifically linked to a drug's effects ( WHO, 1997 ). Examples of the instrumental use of amphetamine-type stimulants include vehicle drivers who report using to improve concentration and relieve tiredness, and people who want to lose weight (particularly young women), using these drugs to curb their appetite. However, the term `instrumental substance use' seems to be used when specific physical effects of a drug are exploited and does not encompass use for more subtle social or psychological purposes which may also be cited by users. In recent reports we have described a `drug use functions' model to help understand poly-substance use phenomenology amongst young people and how decisions are made about patterns of consumption ( Boys et al ., 1999a , b , 2000a ). The term `function' is intended to characterize the primary or multiple reasons for, or purpose served by, the use of a particular substance in terms of the actual gains that the user perceives that they will attain. In the early, 1970s Sadava suggested that functions were a useful means of understanding how personality and environmental variables impacted on patterns of drug use ( Sadava, 1975 ). This work was confined to functions for cannabis and `psychedelic drugs' amongst a sample of college students. To date there has been little research that has examined the different functions associated with the range of psychoactive substances commonly used by young poly-drug users. It is unclear if all drugs with similar physical effects are used for similar purposes, or if other more subtle social or psychological dimensions to use are influential. Work in this area will help to increase understanding of the different roles played by psychoactive substances in the lives of young people, and thus facilitate health, educational and policy responses to this issue.

Previous work has suggested that the perceived functions served by the use of a drug predict the likelihood of future consumption ( Boys et al ., 1999a ). The present study aims to develop this work further by examining the functional profiles of six substances commonly used by young people in the UK.

Patterns of cannabis, amphetamine, ecstasy, LSD, cocaine hydrochloride and alcohol use were examined amongst a sample of young poly-drug users. Tobacco use was not addressed in the present research.

Sampling and recruitment

A snowball-sampling approach was employed for recruitment of participants. Snowball sampling is an effective way of generating a large sample from a hidden population where no formal sampling frame is available ( Van Meter, 1990 ). A team of peer interviewers was trained to recruit and interview participants for the study. We have described this procedure in detail elsewhere and only essential features are described here ( Boys et al. 2000b ). Using current or ex-drug users to gather data from hidden populations of drug using adults has been found to be successful ( Griffiths et al ., 1993 ; Power, 1995 ).

Study participants

Study participants were current poly-substance users with no history of treatment for substance-related disorders. We excluded people with a treatment history on the assumption that young people who have had substance-related problems requiring treatment represent a different group from the general population of young drug users. Inclusion criteria were: aged 16–22 years and having used two or more illegal substances during the past 90 days. During data collection, the age, gender and current occupation of participants were recorded and monitored to ensure that sufficient individuals were recruited to the groups to permit subgroup analyses. If an imbalance was observed in one of these variables, the interviewers were instructed to target participants with specific characteristics (e.g. females under the age of 18) to redress this imbalance.

Study measures

Data were collected using a structured interviewer-administered questionnaire developed specifically for the study. In addition to recording lifetime substance use, questions profiled consumption patterns of six substances in detail. Data were collected between August and November 1998. Interviews were audiotaped with the interviewee's consent. This enabled research staff to verify that answers had been accurately recorded on the questionnaire and that the interview had been conducted in accordance with the research protocol. Research staff also checked for consistency across different question items (e.g. the total number of days of drug use in the past 90 days should equal or exceed the number of days of cannabis use during the same time period). On the few occasions where inconsistencies were identified that could not be corrected from the tape, the interviewer was asked to re-contact the interviewee to verify the data.

Measures of lifetime use, consumption in the past year and past 90 days were based on procedures developed by Marsden et al . ( Marsden et al ., 1998 ). Estimated intensity of consumption (amount used on a typical using day) was recorded verbatim and then translated into standardized units at the data entry stage.

Functions for substance use scale

The questionnaire included a 17-item scale designed to measure perceived functions for substance use. This scale consisted of items developed in previous work ( Boys et al ., 1999a ) in addition to functions derived from qualitative interviews ( Boys et al ., 1999b ), new literature and informal discussions with young drug users. Items were drawn from five domains (Table I ).

Participants were asked if they had ever used a particular drug in order to fulfil each specific function. Those who endorsed the item were then invited to rate how frequently they had used it for this purpose over the past year, using a five-point Likert-type scale (`never' to `always'; coded 0–4). One item differed between the function scales used for the stimulant drugs and for alcohol and cannabis. For the stimulant drugs (amphetamines, cocaine and ecstasy) the item `have you ever used [named drug] to help you to lose weight' was used, for cannabis and alcohol this item was replaced with `have you ever used [drug] to help you to sleep?'. (The items written in full as they appeared in the questionnaire are shown in Table III , together with abbreviations used in this paper.)

Statistical procedures

The internal reliability of the substance use functions scales for each of the six substances was judged using Chronbach's α coefficient. Chronbach's α is a statistic that reflects the extent to which each item in a measurement scale is associated with other items. Technically it is the average of correlations between all possible comparisons of the scale items that are divided into two halves. An α coefficient for a scale can range from 0 (no internal reliability) to 1 (complete reliability). Analyses of categorical variables were performed using χ 2 statistic. Differences in scale means were assessed using t -tests.

The sample consisted of 364 young poly-substance users (205 males; 56.3%) with a mean age of 19.3 years; 69.8% described their ethnic group as White-European, 12.6% as Black and 10.1% were Asian. Just over a quarter (27.5%) were unemployed at the time of interview; a third were in education, 28.8% were in full-time work and the remainder had part-time employment. Estimates of monthly disposable income (any money that was spare after paying for rent, bills and food) ranged from 0 to over £1000 (median = £250).

Substance use history

The drug with the highest lifetime prevalence was cannabis (96.2%). This was followed by amphetamine sulphate (51.6%), cocaine hydrochloride (50.5%) (referred to as cocaine hereafter) and ecstasy (48.6%). Twenty-five percent of the sample had used LSD and this was more common amongst male participants (χ 2 [1] = 9.68, P < 0.01). Other drugs used included crack cocaine (25.5%), heroin (12.6%), tranquillizers (21.7%) and hallucinogenic mushrooms (8.0%). On average, participants had used a total of 5.2 different psychoactive substances in their lives (out of a possible 14) (median = 4.0, mode = 3.0, range 2–14). There was no gender difference in the number of different drugs ever used.

Table II profiles use of the six target drugs over the past year, and the frequency and intensity of use in the 90 days prior to interview.

There were no gender differences in drug use over the past year or in the past 90 days with the exception of amphetamines. For this substance, females who had ever used this drug were more likely to have done so during the past 90 days than males (χ 2 [1] = 4.14, P < 0.05). The mean number of target drugs used over the past 90 days was 3.2 (median = 3.0, mode = 3.0, range 2–6). No gender differences were observed. Few differences were also observed in the frequency and intensity of use. Males reported drinking alcohol more frequently during the three months prior to interview ( t [307] = 2.48, P < 0.05) and using cannabis more intensively on a `typical using day' ( t [337] = 3.56, P < 0.001).

Perceived functions for substance use

There were few differences between the functions endorsed for use of each drug `ever' and those endorsed for use during `the year prior to interview'. This section therefore concentrates on data for the year prior to interview. We considered that in order to use a drug for a specific function, the user must have first hand knowledge of the drug's effects before making this decision. Consequently, functions reported by individuals who had only used a particular substance on one occasion in their lives (i.e. with no prior experience of the drug at the time they made the decision to take it) were excluded from the analyses. Table III summarizes the proportion of the sample who endorsed each of the functions for drugs used in the past year. Roman numerals have been used to indicate the functions with the top five average scores. Table III also shows means for the total number of different items endorsed by individual users and the internal reliability of the function scales for each substance using Chronbach's α coefficients. There were no significant gender differences in the total number of functions endorsed for any of the six substances.

The following sections summarize the top five most popular functions drug-by-drug together with any age or gender differences observed in the items endorsed.

Cannabis use ( n = 345)

Overall the most popular functions for cannabis use were to `RELAX' (endorsed by 96.8% of people who had used the drug in the last year), to become `INTOXICATED' (90.7%) and to `ENHANCE ACTIVITY' (72.8%). Cannabis was also commonly used to `DECREASE BOREDOM' (70.1%) and to `SLEEP' (69.6%) [this item was closely followed by using to help `FEEL BETTER' (69.0%)]. Nine of the 17 function items were endorsed by over half of those who had used cannabis on more than one occasion in the past year. There were no significant gender differences observed, with the exception of using to `KEEP GOING', where male participants were significantly more likely to say that they had used cannabis to fulfil this function in the past year (χ 2 [1] = 6.10, P < 0.05).

There were statistically significant age differences on four of the function variables: cannabis users who reported using this drug in the past year to help feel `ELATED/EUPHORIC' or to help `SLEEP' were significantly older than those who had not used cannabis for these purposes (19.6 versus 19.0; t [343] = 3.32, P < 0.001; 19.4 versus 19.0; t [343] = 2.01, P < 0.05). In contrast, those who had used cannabis to `INCREASE CONFIDENCE' and to `STOP WORRYING' tended to be younger than those who did not (19.0 versus 19.4; t [343] = –2.26, P < 0.05; 19.1 versus 19.5; t [343] = –1.99, P < 0.05).

Amphetamines ( n = 160)

Common functions for amphetamine use were to `KEEP GOING' (95.6%), to `STAY AWAKE' (91.3%) or to `ENHANCE ACTIVITY' (66.2%). Using to help feel `ELATED/EUPHORIC' (60.6%) and to `ENJOY COMPANY' (58.1%) were also frequently mentioned. Seven of the 17 function items were endorsed by over half of participants who had used amphetamines in the past year. As with cannabis, gender differences were uncommon: females were more likely to use amphetamines to help `LOSE WEIGHT' than male participants (χ 2 [1] = 21.67, P < 0.001).

Significant age differences were found on four function variables. Individuals who reported using amphetamines in the past year to feel `ELATED/EUPHORIC' were significantly older than those who did not (19.9 versus 19.0; t [158] = 2.87, P < 0.01). In contrast, participants who used amphetamines to `STOP WORRYING' (18.8 versus 19.8; t [158] = –2.77, P < 0.01), to `DECREASE BOREDOM' (19.2 versus 19.9; t [158] = –2.39, P < 0.05) or to `ENHANCE ACTIVITY' (19.3 versus 20.1; t [158] = –2.88, P < 0.01) were younger than those who had not.

Ecstasy ( n = 157)

The most popular five functions for using ecstasy were similar to those for amphetamines. The drug was used to `KEEP GOING' (91.1%), to `ENHANCE ACTIVITY' (79.6%), to feel `ELATED/EUPHORIC' (77.7%), to `STAY AWAKE' (72.0%) and to get `INTOXICATED' (68.2%). Seven of the 17 function items were endorsed by over half of those who had used ecstasy in the past year. Female users were more likely to use ecstasy to help `LOSE WEIGHT' than male participants (Fishers exact test, P < 0.001).

As with the other drugs discussed above, participants who reported using ecstasy to feel `ELATED/EUPHORIC' were significantly older than those who did not (19.8 versus 18.9; t [155] = 2.61, P < 0.01). In contrast, those who had used ecstasy to `FEEL BETTER' (19.3 versus 20.0; t [155] = –2.29, P < 0.05), to `INCREASE CONFIDENCE' (19.2 versus 19.9; t [155] = –2.22, P < 0.05) and to `STOP WORRYING' (19.0 versus 19.9; t [155] = –2.96, P < 0.01) tended to be younger.

LSD ( n = 58)

Of the six target substances examined in this study, LSD was associated with the least diverse range of functions for use. All but two of the function statements were endorsed by at least some users, but only five were reported by more than 50%. The most common purpose for consuming LSD was to get `INTOXICATED' (77.6%). Other popular functions included to feel `ELATED/EUPHORIC' and to `ENHANCE ACTIVITY' (both endorsed by 72.4%), and to `KEEP GOING' and to `ENJOY COMPANY' (both endorsed by 58.6%). Unlike the other substances examined, no gender or age differences were observed.

Cocaine ( n = 168)

In common with ecstasy and amphetamines, the most widely endorsed functions for cocaine use were to help `KEEP GOING' (84.5%) and to help `STAY AWAKE' (69.0%). Consuming cocaine to `INCREASE CONFIDENCE' and to get `INTOXICATED' (both endorsed by 66.1%) were also popular. However, unlike the other stimulant drugs, 61.9% of the cocaine users reported using to `FEEL BETTER'. Ten of the 17 function items were endorsed by over half of those who had used cocaine in the past year.

Gender differences were more common amongst functions for cocaine use than the other substances surveyed. More males reported using cocaine to `IMPROVE EFFECTS' of other drugs (χ 2 [1] = 4.00, P < 0.05); more females used the drug to help `STAY AWAKE' (χ 2 [1] = 12.21, P < 0.001), to `LOSE INHIBITIONS' (χ 2 [1] = 9.01, P < 0.01), to `STOP WORRYING' (χ 2 [1] = 8.11, P < 0.01) or to `ENJOY COMPANY' of friends (χ 2 [1] = 4.34, P < 0.05). All participants who endorsed using cocaine to help `LOSE WEIGHT' were female.

Those who had used cocaine to `FEEL BETTER' (18.9 versus 19.8; t [166] = –3.06, P < 0.01), to `STOP WORRYING' (18.6 versus 19.7; t [166] = –3.86, P < 0.001) or to `DECREASE BOREDOM' (18.9 versus 19.6; t [166] = –2.52, P < 0.05) were significantly younger than those who did not endorse these functions. Similar to the other drugs, participants who had used cocaine to feel `ELATED/EUPHORIC' in the past year tended to be older than those who had not (19.6 versus 18.7; t [166] = 3.16, P < 0.01).

Alcohol ( n = 312)

The functions for alcohol use were the most diverse of the six substances examined. Like LSD, the most commonly endorsed purpose for drinking was to get `INTOXICATED' (89.1%). Many used alcohol to `RELAX' (82.7%), to `ENJOY COMPANY' (74.0%), to `INCREASE CONFIDENCE' (70.2%) and to `FEEL BETTER' (69.9%). Overall, 11 of the 17 function items were endorsed by over 50% of those who had drunk alcohol in the past year. Male participants were more likely to report using alcohol in combination with other drugs either to `IMPROVE EFFECTS' of other drugs (χ 2 [1] = 4.56, P < 0.05) or to ease the `AFTER EFFECTS' of other substances (χ 2 [1] = 7.07, P < 0.01). More females than males reported that they used alcohol to `DECREASE BOREDOM' (χ 2 [1] = 4.42, P < 0.05).

T -tests revealed significant age differences on four of the function variables: those who drank to feel `ELATED/EUPHORIC' were significantly older (19.7 versus 19.0; t [310] = 3.67, P < 0.001) as were individuals who drank to help them to `LOSE INHIBITIONS' (19.6 versus 19.0; t [310] = 2.36, P < 0.05). In contrast, participants who reported using alcohol just to get `INTOXICATED' (19.2 versus 20.3; t [310] = –3.31, P < 0.001) or to `DECREASE BOREDOM' (19.2 versus 19.6; t [310] = –2.25, P < 0.05) were significantly younger than those who did not.

Combined functional drug use

The substances used by the greatest proportion of participants to `IMPROVE EFFECTS' from other drugs were cannabis (44.3%), alcohol (41.0%) and amphetamines (37.5%). It was also common to use cannabis (64.6%) and to a lesser extent alcohol (35.9%) in combination with other drugs in order to help manage `AFTER EFFECTS'. Amphetamines, ecstasy, LSD and cocaine were also used for these purposes, although to a lesser extent. Participants who endorsed the combination drug use items were asked to list the three main drugs with which they had combined the target substance for these purposes. Table IV summarizes these responses.

Overall functions for drug use

In order to examine which functions were most popular overall, a dichotomous variable was created for each different item to indicate if one or more of the six target substances had been used to fulfil this purpose during the year prior to interview. For example, if an individual reported that they had used cannabis to relax, but their use of ecstasy, amphetamines and alcohol had not fulfilled this function, then the variable for `RELAX' was scored `1'. Similarly if they had used all four of these substances to help them to relax in the past year, the variable would again be scored as `1'. A score of `0' indicates that none of the target substances had been used to fulfil a particular function. Table V summarizes the data from these new variables.

Over three-quarters of the sample had used at least one target substance in the past year for 11 out of the 18 functions listed. The five most common functions for substance use overall were to `RELAX' (96.7%); `INTOXICATED' (96.4%); `KEEP GOING' (95.9%); `ENHANCE ACTIVITY' (88.5%) and `FEEL BETTER' (86.8%). Despite the fact that `SLEEP' was only relevant to two substances (alcohol and cannabis), it was still endorsed by over 70% of the total sample. Using to `LOSE WEIGHT' was only relevant to the stimulant drugs (amphetamines, ecstasy and cocaine), yet was endorsed by 17.3% of the total sample (almost a third of all female participants). Overall, this was the least popular function for recent substance use, followed by `WORK' (32.1%). All other items were endorsed by over 60% of all participants.

Gender differences were identified in six items. Females were significantly more likely to have endorsed the following: using to `INCREASE CONFIDENCE' (χ 2 [1] = 4.41, P < 0.05); `STAY AWAKE' (χ 2 [1] = 5.36, P < 0.05), `LOSE INHIBITIONS' (χ 2 [1] = 4.48, P < 0.05), `ENHANCE SEX' (χ 2 [1] = 5.17, P < 0.05) and `LOSE WEIGHT' (χ 2 [1] = 29.6, P < 0.001). In contrast, males were more likely to use a substance to `IMPROVE EFFECTS' of another drug (χ 2 [1] = 11.18, P < 0.001).

Statistically significant age differences were identified in three of the items. Those who had used at least one of the six target substances in the last year to feel `ELATED/EUPHORIC' (19.5 versus 18.6; t [362] = 4.07, P < 0.001) or to `SLEEP' (19.4 versus 18.9; t [362] = 2.19, P < 0.05) were significantly older than those who had not used for this function. In contrast, participants who had used in order to `STOP WORRYING' tended to be younger (19.1 versus 19.7; t [362] = –2.88, P < 0.01).

This paper has examined psychoactive substance use amongst a sample of young people and focused on the perceived functions for use using a 17-item scale. In terms of the characteristics of the sample, the reported lifetime and recent substance use was directly comparable with other samples of poly-drug users recruited in the UK [e.g. ( Release, 1997 )].

Previous studies which have asked users to give reasons for their `drug use' overall instead of breaking it down by drug type [e.g. ( Carman, 1979 ; Butler et al ., 1981 ; Newcomb et al ., 1988 ; Cato, 1992 ; McKay et al ., 1992 )] may have overlooked the dynamic nature of drug-related decision making. A key finding from the study is that that with the exception of two of the functions for use scale items (using to help sleep or lose weight), all of the six drugs had been used to fulfil all of the functions measured, despite differences in their pharmacological effects. The total number of functions endorsed by individuals for use of a particular drug varied from 0 to 15 for LSD, and up to 17 for cannabis, alcohol and cocaine. The average number ranged from 5.9 (for LSD) to 9.0 (for cannabis). This indicates that substance use served multiple purposes for this sample, but that the functional profiles differed between the six target drugs.

We have previously reported ( Boys et al. 2000b ) that high scores on a cocaine functions scale are strongly predictive of high scores on a cocaine-related problems scale. The current findings support the use of similar function scales for cannabis, amphetamines, LSD and ecstasy. It remains to be seen whether similar associations with problem scores exist. Future developmental work in this area should ensure that respondents are given the opportunity to cite additional functions to those included here so that the scales can be further extended and refined.

Recent campaigns that have targeted young people have tended to assume that hallucinogen and stimulant use is primarily associated with dance events, and so motives for use will relate to this context. Our results support assumptions that these drugs are used to enhance social interactions, but other functions are also evident. For example, about a third of female interviewees had used a stimulant drug to help them to lose weight. Future education and prevention efforts should take this diversity into account when planning interventions for different target groups.

The finding that the same functions are fulfilled by use of different drugs suggests that at least some could be interchangeable. Evidence for substituting alternative drugs to fulfil a function when a preferred drug is unavailable has been found in other studies [e.g. ( Boys et al. 2000a )]. Prevention efforts should perhaps focus on the general motivations behind use rather than trying to discourage use of specific drug types in isolation. For example, it is possible that the focus over the last decade on ecstasy prevention may have contributed inadvertently to the rise in cocaine use amongst young people in the UK ( Boys et al ., 1999c ). It is important that health educators do not overlook this possibility when developing education and prevention initiatives. Considering functions that substance use can fulfil for young people could help us to understand which drugs are likely to be interchangeable. If prevention programmes were designed to target a range of substances that commonly fulfil similar functions, then perhaps this could address the likelihood that some young people will substitute other drugs if deterred from their preferred substance.

There has been considerable concern about the perceived increase in the number of young people who are using cocaine in the UK ( Tackling Drugs to Build a Better Britain 1998 ; Ramsay and Partridge, 1999 ; Boys et al. 2000b ). It has been suggested that, for a number of reasons, cocaine may be replacing ecstasy and amphetamines as the stimulant of choice for some young people ( Boys et al ., 1999c ). The results from this study suggest that motives for cocaine use are indeed similar to those for ecstasy and amphetamine use, e.g. using to `keep going' on a night out with friends, to `enhance an activity', `to help to feel elated or euphoric' or to help `stay awake'. However, in addition to these functions which were shared by all three stimulants, over 60% of cocaine users reported that they had used this drug to `help to feel more confident' in a social situation and to `feel better when down or depressed'. Another finding that sets cocaine aside from ecstasy and amphetamines was the relatively common existence of gender differences in the function items endorsed. Female cocaine users were more likely to use to help `stay awake', `lose inhibitions', `stop worrying', `enjoy company of friends' or to help `lose weight'. This could indicate that women are more inclined to admit to certain functions than their male counterparts. However, the fact that similar gender differences were not observed in the same items for the other five substances, suggests this interpretation is unlikely. Similarly, the lack of gender differences in patterns of cocaine use (both frequency and intensity) suggests that these differences are not due to heavier cocaine use amongst females. If these findings are subsequently confirmed, this could point towards an inclination for young women to use cocaine as a social support, particularly to help feel less inhibited in social situations. If so, young female cocaine users may be more vulnerable to longer-term cocaine-related problems.

Many respondents reported using alcohol or cannabis to help manage effects experienced from another drug. This has implications for the choice of health messages communicated to young people regarding the use of two or more different substances concurrently. Much of the literature aimed at young people warns them to avoid mixing drugs because the interactive effects may be dangerous [e.g. ( HIT, 1996 )]. This `Just say No' type of approach does not take into consideration the motives behind mixing drugs. In most areas, drug education and prevention work has moved on from this form of communication. A more sophisticated approach is required, which considers the functions that concurrent drug use is likely to have for young people and tries to amend messages to make them more relevant and acceptable to this population. Further research is needed to explore the motivations for mixing different combinations of drugs together.

Over three-quarters of the sample reported using at least one of the six target substances to fulfil 11 out of the 18 functions. These findings provide strong evidence that young people use psychoactive drugs for a range of distinct purposes, not purely dependent on the drug's specific effects. Overall, the top five functions were to `help relax', `get intoxicated', `keep going', `enhance activity' and `feel better'. Each of these was endorsed by over 85% of the sample. Whilst all six substances were associated to a greater or lesser degree with each of these items, there were certain drugs that were more commonly associated with each. For example, cannabis and alcohol were popular choices for relaxation or to get intoxicated. In contrast, over 90% of the amphetamine and ecstasy users reported using these drugs within the last year to `keep going'. Using to enhance an activity was a common function amongst users of all six substances, endorsed by over 70% of ecstasy, cannabis and LSD users. Finally, it was mainly alcohol and cannabis (and to a lesser extent cocaine) that were used to `feel better'.

Several gender differences were observed in the combined functions for recent substance use. These findings indicate that young females use other drugs as well as cocaine as social supports. Using for specific physical effects (weight loss, sex or wakefulness) was also more common amongst young women. In contrast, male users were significantly more likely to report using at least one of the target substances to try to improve the effects of another substance. This indicates a greater tendency for young males in this sample to mix drugs than their female counterparts. Age differences were also observed on several function items: participants who had used a drug to `feel elated or euphoric' or to `help sleep' tended to be older and those who used to `stop worrying about a problem' were younger. If future studies confirm these differences, education programmes and interventions might benefit from tailoring their strategies for specific age groups and genders. For example, a focus on stress management strategies and coping skills with a younger target audience might be appropriate.

Some limitations of the study need to be acknowledged. The sample for this study was recruited using a snowball-sampling methodology. Although it does not yield a random sample of research participants, this method has been successfully used to access hidden samples of drug users [e.g. ( Biernacki, 1986 ; Lenton et al ., 1997 )]. Amongst the distinct advantages of this approach are that it allows theories and models to be tested quantitatively on sizeable numbers of subjects who have engaged in a relatively rare behaviour.

Further research is now required to determine whether our observations may be generalized to other populations (such as dependent drug users) and drug types (such as heroin, tranquillizers or tobacco) or if additional function items need to be developed. Future studies should also examine if functions can be categorized into primary and subsidiary reasons and how these relate to changes in patterns of use and drug dependence. Recognition of the functions fulfilled by substance use could help inform education and prevention strategies and make them more relevant and acceptable to the target audiences.

Structure of functions scales

Profile of substance use over the past year and past 90 days ( n = 364)

Proportion (%) of those who have used [substance] more than once, who endorsed each functional statement for their use in the past year

Combined functional substance use reported by the sample over the past year

Percentage of participants who reported having used at least one of the target substances to fulfil each of the different functions over the past year ( n = 364)

We gratefully acknowledge research support from the Health Education Authority (HEA). The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the HEA. We would also like to thank the anonymous referees for helpful comments and suggestions on an earlier draft of this paper.

Biernacki, P. (1986) Pathways from Heroin Addiction: Recovery without Treatment . Temple University Press, Philadelphia, PA.

Boys, A., Marsden, J., Griffiths, P., Fountain, J., Stillwell, G. and Strang, J. ( 1999 ) Substance use among young people: the relationship between perceived functions and behavioural intentions. Addiction , 94 , 1043 –1050.

Boys, A., Marsden, J., Fountain, J., Griffiths, P., Stillwell, G. and Strang, J. ( 1999 ) What influences young people's use of drugs? A qualitative study of decision-making. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy , 6 , 373 –389.

Boys, A., Marsden, J. and Griffiths. P. ( 1999 ) Reading between the lines: is cocaine becoming the stimulant of choice for urban youth? Druglink , 14 , 20 –23.

Boys, A., Fountain, J., Marsden, J., Griffiths, P., Stillwell, G. and Strang, J. (2000a) Drug Decisions: A Qualitative Study of Young People , Drugs and Alcohol . Health Education Authority, London.

Boys, A., Marsden, J., Griffiths, P. and Strang, J. ( 2000 ) Drug use functions predict cocaine-related problems. Drug and Alcohol Review , 19 , 181 –190.

Butler, M. C., Gunderson, E. K. E. and Bruni, J. R. ( 1981 ) Motivational determinants of illicit drug use: an assessment of underlying dimensions and their relationship to behaviour. International Journal of the Addictions , 16 , 243 –252.

Carman, R. S. ( 1979 ) Motivations for drug use and problematic outcomes among rural junior high school students. Addictive Behaviors , 4 , 91 –93.

Cato, B. M. ( 1992 ) Youth's recreation and drug sensations: is there a relationship? Journal of Drug Education , 22 , 293 –301.

Edwards, G., Chandler, J. and Peto, J. ( 1972 ) Motivation for drinking among men in a London suburb, Psychological Medicine , 2 , 260 –271.

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (1998) Annual Report on the State of the Drugs Problem in the European Union . EMCDDA, Lisbon.

Griffiths, P., Gossop, M., Powis, B. and Strang, J. ( 1993 ) Reaching hidden populations of drug users by privileged access interviewers: methodological and practical issues. Addiction , 88 , 1617 –1626.

HIT (1996) Chill Out: A Clubber's Guide—The Second Coming . HIT, Liverpool.

Johnston, L. D., O'Malley, P. M. and Bachman J. G. (1997) National Survey Results on Drug Use from the Monitoring the Future Study , 1975–1996: Secondary School Students . US DHHS, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Rockville, MD.

Johnston, L. D., O'Malley, P. M. and Bachman J. G. (2000) The Monitoring the Future National Results on Adolescent Drug Use: Overview of Key Findings 1999 . US DHHS, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Rockville, MD.

Lenton, S., Boys, A. and Norcross, K. ( 1997 ) Raves, drugs and experience: drug use by a sample of people who attend raves in Western Australia. Addiction , 92 , 1327 –1337.

Marsden, J., Gossop, M., Stewart, D., Best, D., Farrell, M., Edwards, C., Lehmann, P. and Strang, J. ( 1998 ) The Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP): a brief instrument for assessing treatment outcome. Addiction , 93 , 1857 –1867.

McKay, J. R., Murphy, R. T., McGuire, J., Rivinus, T. R. and Maisto, S. A. ( 1992 ) Incarcerated adolescents' attributions for drug and alcohol use. Addictive Behaviors , 17 , 227 –235.

Newcomb. M. D., Chou, C.-P., Bentler, P. M. and Huba, G. J. ( 1988 ) Cognitive motivations for drug use among adolescents: longitudinal tests of gender differences and predictors of change in drug use. Journal of Counselling Psychology , 35 , 426 –438.

Power, R. ( 1995 ) A model for qualitative action research amongst illicit drug users. Addiction Research , 3 , 165 –181.

Power, R., Power, T. and Gibson, N. ( 1996 ) Attitudes and experience of drug use amongst a group of London teenagers. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy , 3 , 71 –80.

Ramsay, M. and Partridge, S. (1999) Drug Misuse Declared in 1998: Results from the British Crime Survey . Home Office, London.

Release (1997) Release Drugs and Dance Survey: An Insight into the Culture . Release, London.

Sadava, S. ( 1975 ) Research approaches in illicit drug use: a critical review. Genetic Psychology Monographs , 91 , 3 –59.

Tackling Drugs to Build a Better Britain (1998) The Government's 10-year Strategy on Drug Misuse. Central Drugs Co-ordinating Unit, London.

Van Meter, K. M. (1990) Methodological and design issues: techniques for assessing the representatives of snowball samples. In Lambert, E. Y. (ed.), The Collection and Interpretation of Data from Hidden Populations . US DHHS, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Rockville, MD, pp. 31–33.

Wibberley, C. and Price, J. ( 2000 ) Patterns of psycho-stimulant drug use amongst `social/operational users': implications for services. Addiction Research , 8 , 95 –111.

WHO (1997) Amphetamine-type Stimulants: A Report from the WHO Meeting on Amphetamines , MDMA and other Psychostimulants , Geneva, 12–15 November 1996. Programme on Substance Abuse, Division of Mental Health and Prevention of Substance Abuse, WHO, Geneva.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1465-3648

- Print ISSN 0268-1153

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Research Reports

Cannabis (Marijuana) Research Report

Common comorbidities with substance use disorders research report.

Heroin Research Report

Inhalants Research Report

MDMA (Ecstasy) Abuse Research Report

Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report

Methamphetamine Research Report

Misuse of Prescription Drugs Research Report

Prescription Opioids and Heroin Research Report

Substance Use in Women Research Report

Tobacco, Nicotine, and E-Cigarettes Research Report

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 30 October 2020

“College fields of study and substance use”

- Wei-Lin Chen 1 &

- Jen-Hao Chen 2

BMC Public Health volume 20 , Article number: 1631 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

7433 Accesses

3 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Numerous studies have documented factors that are associated with substance use behaviors among college-aged individuals. However, relatively few studies have considered the heterogeneity of the college experience by field of study (i.e., college major) and how that educational context might affect students’ health behaviors differently. Drawing from theories and prior research, this study investigates whether college majors are associated with different substance use behaviors, both during college and upon graduation.

The study analyzed longitudinal data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 97 ( N = 1031), specifically data on individuals who obtained a bachelor’s degree, to examine the associations between college fields of study and trajectories of three substance use behaviors: smoking, heavy alcohol use, and marijuana use.

The results indicate that social science and business majors were associated with more substance use behaviors than arts and humanities and STEM majors. However, social science majors were associated with a faster decrease in substance use behaviors over time. Importantly, the differences we found in mean levels of substance use behaviors and trajectories were not explained by demographic characteristics, family SES background, childhood health conditions, and employment experience. Further analysis that examined college major and each substance use behavior individually suggests that the associations were stronger for heavy alcohol use and marijuana use. Moreover, we found the associations were more pronounced in men than women.

Conclusions

The study finds that not all college majors show the same level of engagement in substance use behaviors over time, and that the associations also vary by (1) the specific substance use behavior examined and (2) by gender. These findings suggest it is important to consider that the different learning and educational contexts that college majors provide may also be more or less supportive of certain health behaviors, such as substance use. Practical implications are discussed.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Substance use is an important public health concern in the United States. National surveys consistently show that substance use peaks during emerging adulthood [ 1 ]. Although college students may show less substance use than non-students in the same age range [ 2 ], it remains true that smoking, heavy alcohol use, and illicit drug use are not uncommon [ 3 , 4 , 5 ] among college students and are considered pressing health issues [ 6 ]. O’Mally and Johnston’s [ 7 ] influential study shows a high prevalence of heavy alcohol use and smoking among college students, with only a slight improvement from 1980 to late 1990. Even the most recent national survey data suggest that substance use remains a pressing health concern of the college-age population. The national Monitoring the Future 2018 survey indicates that among full-time college students in the United States, 15.3% have used cigarette, 29% are heavy alcohol users, and 24.7% have used marijuana during the past 30 days [ 4 ].

Moreover, research makes clear that substance use during the college years has significant consequences for learning and health. College students who are heavy alcohol users are more likely to get injured [ 8 ], have lower academic performance and drop out of college at higher rates [ 9 ], and demonstrate poor working memory [ 10 ]. Marijuana can impair neuropsychological functioning and thus affect individuals’ learning and work performance [ 11 ]. Smoking is associated with lower cognitive function among college students, including a lower level of verbal or auditory competence [ 12 ]. Because so many college students use substances and their negative impact on physical health and learning can be significant, it is critical to investigate and understand the factors that relate to students’ substance use behaviors.

There are many prior studies that contribute to our understanding of the risk and protective factors that may promote or deter substance use among college students [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]. While a full review of the extant studies of substance use among college studies is beyond the scope of this research, it is useful to briefly summarize factors that have been shown to relate to college students’ substance use. Furthermore, studies using large-samples suggest that substance use behaviors (such as heavy alcohol use, smoking, marijuana use) among college students tend to co-occur [ 17 , 18 ], suggesting the need to investigate substance use behaviors simultaneously. Following Ham and Hope’s [ 19 ] approach in their influential systematic review of problematic drinking among college students, we classify previously identified risk and protective factors of substance use at three levels: individual, interpersonal, and contextual. First, substance use varies by individual demographic characteristics and personality factors. For example, studies consistently find that men have a higher likelihood of substance use than women [ 13 , 20 ] and that African American and Hispanic students have lower rates of substance use [ 13 , 20 , 21 ] than white students. Other studies find that certain personality traits appear to be associated with substance use among college students. For example, sensation seeking is related to heavy alcohol use [ 22 , 23 ].

However, individual factors offer little help in prevention and intervention. Therefore, in recent years, research has moved to investigate the role of interpersonal and contextual factors on college students’ substance use. For example, living with parents during college is associated with lower levels of substance use [ 2 ]. In contrast, two systematic literature reviews of problematic drinking and smoking suggest that living on campus appear to correlate with increased alcohol consumption and smoking [ 24 , 25 ]. In contrast, low academic performance, often measured by GPA, is associated with alcohol or illicit drug use. Heavy alcohol or drug use may impact cognitive functioning, which contributes to poorer grades. Evidence also shows that working part-time during college is associated with more substance use [ 26 , 27 ]. Membership in fraternities and sororities is found to be associated with substance use [ 28 , 29 ]. Finally, several studies start to pay attention to the educational context. In a systematic literature review by Carter and colleagues [ 25 ], they conclude that full-time college students, especially for those in 4-year college, display a greater engagement in heavy alcohol use. Cranford and colleagues [ 30 ] analyze a probability sample of students and find that undergraduates are associated with a higher likelihood of heavy alcohol use and marijuana use (but not smoking) than graduate students.

Although prior studies have investigated a wide range of individual, interpersonal, and contextual factors that relate to substance use among college students, the role of college major has received relatively little attention. This is a curious oversight because college education, by nature, is more heterogeneous than secondary education. Even within the same college, majors vary on curricula, expectations, learning environment, and level of professionalization. In addition, majors differ on whether and how much they expect students to learn specialized knowledge, gain hands-on experience, and collaborate on group projects [ 31 , 32 ]. Because a student’s academic experience differs so much by major and is so central to life during the college years, it is reasonable to believe that college major may affect students’ likelihood of engaging in substance use behaviors as they emerge into adulthood. In other words, some of the differences that exist across majors may be more or less protective against, or supportive of, students’ substance use. This study aims to addresses this key, relatively unexplored question: Does a student’s college major predict his/her likelihood of substance use during and after college?

Based on prior studies, there are strong empirical and theoretical reasons to believe that engaging in a health risk behavior, such as substance use, may vary by college major. First, only some majors expose students to knowledge of human health and physiology, which may produce differences in health literacy by major [ 33 ]. Differences in health literacy may, in turn, lead to differences in health behaviors. Second, the undergraduate socialization model conceptualizes college as the primary socialization field for young adults’ development [ 34 , 35 ]. Students are socialized into the norms of their major and participate in activities and social interactions that promote their success in related professional fields. Social learning theory posits that individuals learn from various forms of interaction with peers and colleagues, which highlights the importance of how students’ interactions in their major may affect how they learn health behaviors, such as substance use [ 36 , 37 , 38 ]. For example, health-related majors may be trained to avoid smoking and drug use because they will likely work in smoke-free and drug-free workplaces when they graduate. In contrast, business majors might be socialized to be more tolerant toward smoking and heavy alcohol use because those behaviors occur in the social interactions that graduates have with their clients. In these and other ways, college majors provide a different environment and socialization that may affect health behaviors.

Despite these reasons to believe that a student’s choice of college major may affect their substance use, there is limited empirical evidence on this research question. Of the studies that do exist on the substance use behaviors of college students, many rely on surveys at a single college or university (e.g.), [ 39 , 40 , 41 ]. Even fewer studies exist that consider college major as an influential factor in substance use behaviors over time. Finally, to our knowledge, it appears that no study exists that examines this question with the benefit of a large-scale, national sample with longitudinal data. This study aims to address these limitations by using a large-scale, longitudinal dataset to investigate whether and how engagement in substance use behaviors (i.e., smoking, heavy alcohol use, and marijuana use) varies by college major.

National Longitudinal Survey of youth 1997

This study used data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 (NLSY97), a nationally representative sample of youths who were born between 1980 and 1984. The NLSY97 began by interviewing 8984 respondents who were 12 to 18 years old in 1997–1998 (round 1). Respondents were followed every year until 2013–2014 (round 16). After that, respondents were followed every 2 years [ 42 ]. The NLSY97 aims to understand U.S. youths’ transition from school to work and into adulthood [ 43 ]. The NLSY97’s detailed information on college education, together with the large-scale, longitudinal national sample, provide a rare opportunity to examine college majors and substance use over time.

We used transcript data in the NLSY97 to identify when a respondent started college and when s/he received a college degree. College transcripts provide the most accurate information on when individuals started college and whether they received a bachelor’s degree. We limited the study to respondents who obtained a bachelor’s degree between 2001 and 2011 because no college transcript data was collected after 2011. After excluding any individual whose college major could not be identified or was missing, we were left with a sample of 1099 youths who completed college, obtained their degree between 2001 and 2011, and whose college major was known. A small proportion of youth in our sample had missing values on the variables of interest for health behaviors (i.e., smoking, heavy alcohol use, and marijuana use). For each youth, three rounds of data were used in the analysis: the wave when the respondent entered college, the wave when the respondent finished college, and the wave after college completion. The final sample for longitudinal analysis included 1031 youth.

Classification of college major