Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 13 May 2021

Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Surapon Nochaiwong ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1100-7171 1 , 2 ,

- Chidchanok Ruengorn ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7927-1425 1 , 2 ,

- Kednapa Thavorn ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4738-8447 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ,

- Brian Hutton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5662-8647 3 , 4 , 5 ,

- Ratanaporn Awiphan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3628-0596 1 , 2 ,

- Chabaphai Phosuya 1 ,

- Yongyuth Ruanta ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4184-0308 1 , 2 ,

- Nahathai Wongpakaran ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8365-2474 6 &

- Tinakon Wongpakaran ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9062-3468 6

Scientific Reports volume 11 , Article number: 10173 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

54k Accesses

298 Citations

117 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Post-traumatic stress disorder

To provide a contemporary global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population amid the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. We searched electronic databases, preprint databases, grey literature, and unpublished studies from January 1, 2020, to June 16, 2020 (updated on July 11, 2020), with no language restrictions. Observational studies using validated measurement tools and reporting data on mental health issues among the general population were screened to identify all relevant studies. We have included information from 32 different countries and 398,771 participants. The pooled prevalence of mental health issues amid the COVID-19 pandemic varied widely across countries and regions and was higher than previous reports before the COVID-19 outbreak began. The global prevalence estimate was 28.0% for depression; 26.9% for anxiety; 24.1% for post-traumatic stress symptoms; 36.5% for stress; 50.0% for psychological distress; and 27.6% for sleep problems. Data are limited for other aspects of mental health issues. Our findings highlight the disparities between countries in terms of the poverty impacts of COVID-19, preparedness of countries to respond, and economic vulnerabilities that impact the prevalence of mental health problems. Research on the social and economic burden is needed to better manage mental health problems during and after epidemics or pandemics. Systematic review registration : PROSPERO CRD 42020177120.

Similar content being viewed by others

Public mental health problems during COVID-19 pandemic: a large-scale meta-analysis of the evidence

Xuerong Liu, Mengyin Zhu, … Zhiyi Chen

Mental disorders following COVID-19 and other epidemics: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Candi M. C. Leung, Margaret K. Ho, … Michael Y. Ni

Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder after infectious disease pandemics in the twenty-first century, including COVID-19: a meta-analysis and systematic review

Kai Yuan, Yi-Miao Gong, … Lin Lu

Introduction

After the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the rapid worldwide spread of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) to be a pandemic, there has been a dramatic rise in the prevalence of mental health problems both nationally and globally 1 , 2 , 3 . Early international evidence and reviews have reported the psychological effects of the COVID-19 outbreak on patients and healthcare workers, particularly those in direct contact with affected patients 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 . Besides patients with COVID-19, negative emotions and psychosocial distress may occur among the general population due to the wider social impact and public health and governmental response, including strict infection control, quarantine, physical distancing, and national lockdowns 2 , 9 , 10 .

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, several mental health and psychosocial problems, for instance, depressive symptoms, anxiety, stress, post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS), sleep problems, and other psychological conditions are of increasing concern and likely to be significant 5 , 10 , 11 . Public psychological consequences can arise through direct effects of the COVID-19 pandemic that are sequelae related to fear of contagion and perception of danger 2 . However, financial and economic issues also contribute to mental health problems among the general population in terms of indirect effects 12 , 13 . Indeed, economic shutdowns have disrupted economies worldwide, particularly in countries with larger domestic outbreaks, low health system preparedness, and high economic vulnerability 14 , 15 , 16 .

The COVID-19 pandemic may affect the mental health of the general population differently based on national health and governmental policies implemented and the public resilience and social norms of each country. Unfortunately, little is known about the global prevalence of mental health problems in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous systematic reviews have been limited by the number of participants included, and attention has been focussed on particular conditions and countries, with the majority of studies being conducted in mainland China 5 , 8 , 11 , 17 , 18 . To the best of our knowledge, evidence on mental health problems among the general population worldwide has not been comprehensively documented in the current COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, a systematic review and meta-analysis at a global level is needed to provide robust and contemporary evidence to inform public health policies and long-term responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

As such, we have performed a rigorous systematic review and meta-analysis of all available observational studies to shed light on the effects of the global COVID-19 pandemic on mental health problems among the general population. We aimed to: (1) summarise the prevalence of mental health problems nationally and globally, and (2) describe the prevalence of mental health problems by each WHO region, World Bank income group, and the global index and economic indices responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

This systematic review and meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines 19 and reported in line with the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement (Appendix, Table S1 ) 20 . The pre-specified protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO: CRD42020177120).

Search strategy

We searched electronic databases in collaboration with an experienced medical librarian using an iterative process. PubMed, Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, Scopus, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Library were used to identify all relevant abstracts. As the WHO declared the COVID-19 outbreak to be a public health emergency of international concern on January 30, 2020, we limited the search from January 1, 2020, to June 16, 2020, without any language restrictions. The main keywords used in the search strategy included “coronavirus” or “COVID-19” or “SARS-CoV-2”, AND “mental health” or “psychosocial problems” or “depression” or “anxiety” or “stress” or “distress” or “post-traumatic stress symptoms” or “suicide” or “insomnia” or “sleep problems” (search strategy for each database is provided in the Appendix, Table S2 ). Relevant articles were also identified from the reference lists of the included studies and previous systematic reviews. To updated and provide comprehensive, evidence-based data during the COVID-19 pandemic, grey literature from Google Scholar and the preprint reports from medRxiv, bioRxiv, and PsyArXiv were supplemented to the bibliographic database searches. A targeted manual search of grey literature and unpublished studies was performed through to July 11, 2020.

Study selection and data screening

We included observational studies (cross-sectional, case–control, or cohort) that (1) reported the occurrence or provided sufficient data to estimate the prevalence of mental health problems among the general population, and (2) used validated measurement tools for mental health assessment. The pre-specified protocol was amended to permit the inclusion of studies the recruited participants aged 12 years or older and college students as many colleges and universities were closed due to national lockdowns. We excluded studies that (1) were case series/case reports, reviews, or studies with small sample sizes (less than 50 participants); (2) included participants who had currently confirmed with the COVID-19 infection; and (3) surveyed individuals under hospital-based settings. If studies had overlapping participants and survey periods, then the study with the most detailed and relevant information was used.

Eligible titles and abstracts of articles identified by the literature search were screened independently by two reviewers (SN and CR). Then, potentially relevant full-text articles were assessed against the selection criteria for the final set of included studies. Potentially eligible articles that were not written in English were translated before the full-text appraisal. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion.

The primary outcomes were key parameters that reflect the global mental health status during the COVID-19 pandemic, including depression, anxiety, PTSS, stress, psychological distress, and sleep problems (insomnia or poor sleep). To deliver more evidence regarding the psychological consequences, secondary outcomes of interest included psychological symptoms, suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, loneliness, somatic symptoms, wellbeing, alcohol drinking problems, obsessive–compulsive symptoms, panic disorder, phobia anxiety, and adjustment disorder.

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers (SN and YR) independently extracted the pre-specified data using a standardised approach to gather information on the study characteristics (the first author’s name, study design [cross-sectional survey, longitudinal survey, case–control, or cohort], study country, article type [published article, short report/letters/correspondence, or preprint reporting data], the data collection period), participant characteristics (mean or median age of the study population, the proportion of females, proportion of unemployment, history of mental illness, financial problems, and quarantine status [never, past, or current]), and predefined outcomes of interest (including assessment outcome definitions, measurement tool, and diagnostic cut-off criteria). For international studies, data were extracted based on the estimates within each country. For studies that had incomplete data or unclear information, the corresponding author was contacted by email for further clarification. The final set of data was cross-checked by the two reviewers (RA and CP), and discrepancies were addressed through a discussion.

Two reviewers (SN and CR) independently assessed and appraised the methodological quality of the included studies using the Hoy and colleagues Risk of Bias Tool-10 items 21 . A score of 1 (no) or 0 (yes) was assigned to each item. The higher the score, the greater the overall risk of bias of the study, with scores ranging from 0 to 10. The included studies were then categorised as having a low (0–3 points), moderate (4–6 points), or high (7 or 10 points) risk of bias. A pair of reviewers (RA and CP) assessed the risk of bias of each study. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Data synthesis and statistical methods

A two-tailed P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We used Stata software version 16.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) for all analyses and generated forest plots of the summary pooled prevalence. Inter-rater agreements between reviewers for the study selection and risk of bias assessment were tested using the kappa (κ) coefficient of agreement 22 . Based on the crude information data, we recalculated and estimated the unadjusted prevalence of mental health and psychological problems using the crude numerators and denominators reported by each of the included studies. Unadjusted pooled prevalence with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was reported for each WHO regions (Africa, America, South-East Asia, Europe, Eastern Mediterranean, and Western Pacific) and World Bank income group (low-, lower-middle-, upper-middle-, and high-income).

We employed the variance of the study-specific prevalence using the Freeman–Tukey double arcsine methods for transforming the crude data before pooling the effect estimates with a random-effect model to account for the effects of studies with extreme (small or large) prevalence estimates 23 . Heterogeneity was evaluated using the Cochran’s Q test, with a p value of less than 0.10 24 . The degree of inconsistency was quantified using I 2 values, in which a value greater than 60–70% indicated the presence of substantial heterogeneity 25 .

Pre-planned subgroup analyses were performed based on the participant (i.e., age, the proportion of female sex, the proportion of unemployment, history of mental illness, financial problems, and quarantine status) and study characteristics (article type, study design, data collection, and sample size). To explore the inequality and poverty impacts across countries, subgroup analyses based on the global index and economic indices responses to the COVID-19 pandemic were performed, including (1) human development index (HDI) 2018 (low, medium, high, and very high) 26 ; (2) gender inequality index 2018 (below vs above world average [0.439]) 27 ; (3) the COVID-19-government response stringency index during the survey (less- [less than 75%], moderate- [75–85%], and very stringent [more than 85%]) according to the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker reports 28 ; (4) the preparedness of countries in terms of hospital beds per 10,000 people, 2010–2018 (low, medium–low, medium, medium–high, and high) 15 ; (5) the preparedness of countries in terms of current health expenditure (% of gross domestic product [GDP] 2016; low, medium–low, medium, medium–high, and high) 15 ; (6) estimated percent change of real GDP growth based on the International Monetary Fund, April 2020 (below vs above world average [− 3.0]) 29 ; (7) the resilience of countries’ business environment based on the 2020 global resilience index reports (first-, second-, third-, and fourth-quartile) 30 ; and (8) immediate economic vulnerability in terms of inbound tourism expenditure (% of GDP 2016–2018; low, medium–low, medium, medium–high, and high) 15 .

To address the robustness of our findings, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by restricting the analysis to studies with a low risk of bias (Hoy and Colleagues-Tool, 0–3 points). Furthermore, a random-effects univariate meta-regression analysis was used to explore the effect of participant and study characteristics, and the global index and economic indices responses to the COVID-19 pandemic as described above on the prevalence estimates.

The visual inspection of funnel plots was performed when there was sufficient data and tested for asymmetry using the Begg’s and Egger’s tests for each specific. A P value of less than 0.10 was considered to indicate statistical publication bias 31 , 32 . If the publication bias was detected by the Begg’s and Egger’s regression test, the trim and fill method was then performed to calibrate for publication bias 33 .

Initially, the search strategy retrieved 4642 records. From these, 2682 duplicate records were removed, and 1960 records remained. Based on the title and abstract screening, we identified 498 articles that seemed to be relevant to the study question (the κ statistic for agreement between reviewers was 0.81). Of these, 107 studies fulfilled the study selection criteria and were included in the meta-analysis (Appendix, Figure S1 ). The inter-rater agreement between reviewers on the study selection and data extraction was 0.86 and 0.75, respectively. The reference list of all included studies in this review is provided in the Appendix, Table S3 .

Characteristics of included studies

In total, 398,771 participants from 32 different countries were included. The mean age was 33.5 ± 9.5 years, and the proportion of female sex was 60.9% (range, 16.0–51.6%). Table 1 summarises the characteristics of all the included studies according to World Bank income group, the global index of COVID-19 pandemic preparedness, and economic vulnerability indices. The included studies were conducted in the Africa (2 studies 34 , 35 [1.9%], n = 723), America (12 studies 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 [11.2%], n = 18,440), South-East Asia (10 studies 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 [9.4%], n = 11,953), Europe (27 studies 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 [25.2%], n = 148,430), Eastern Mediterranean (12 studies 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 [11.2%], n = 23,396), and Western Pacific WHO regions (44 studies 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 , 108 , 109 , 110 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 , 120 , 121 , 122 , 123 , 124 , 125 , 126 , 127 , 128 , 129 , 130 , 131 , 132 , 133 , 134 , 135 , 136 , 137 , 138 , 139 , 140 [41.1%], n = 195,829). Most of the included studies were cross-sectional (96 studies, 89.7%), used an online-based survey (101 studies, 95.3%), conducted in mainland China (34 studies, 31.8%), and were conducted in countries with upper-middle (49 studies, 45.8%) and high-incomes (44 studies, 41.1%). Detailed characteristics of the 107 included studies, measurement tools for evaluating the mental health status and psychological consequences, and the diagnostic cut-off criteria are described in Appendix, Table S4 . Of the 107 included studies, 76 (71.0%) had a low risk, 31 (29.0%) had a moderate risk, and no studies had a high risk of bias (Appendix, Table S5 ).

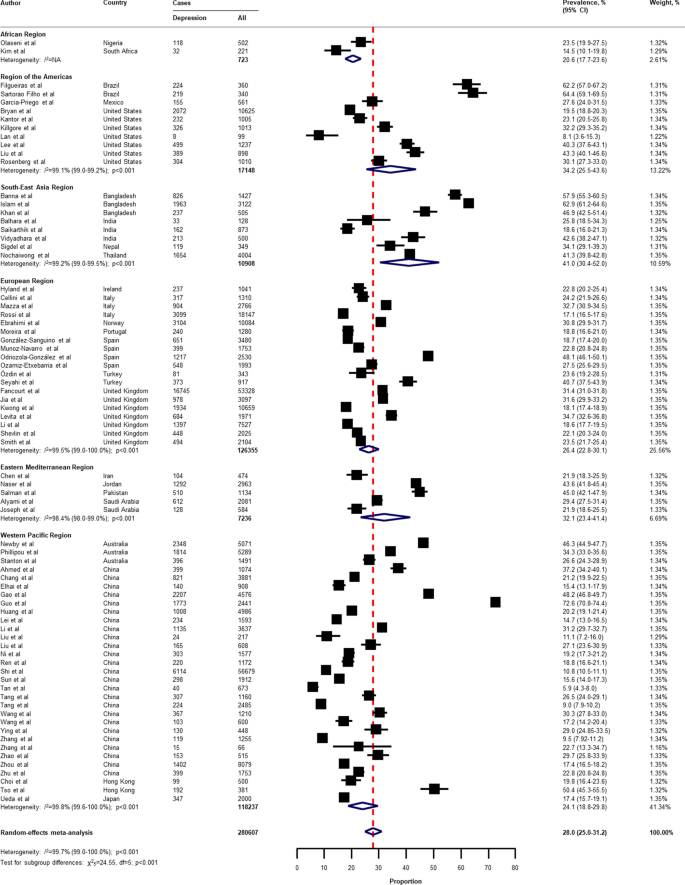

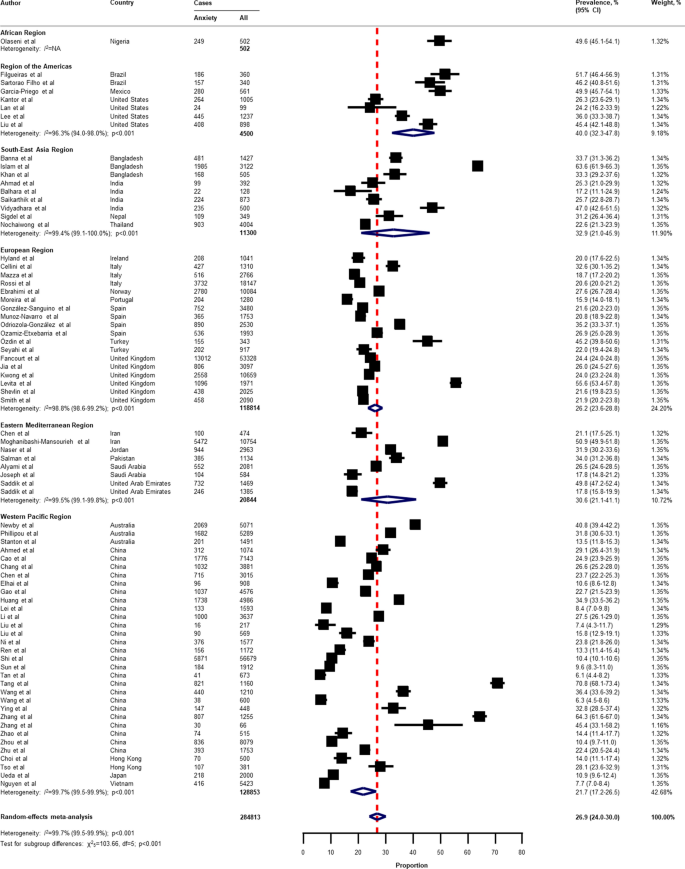

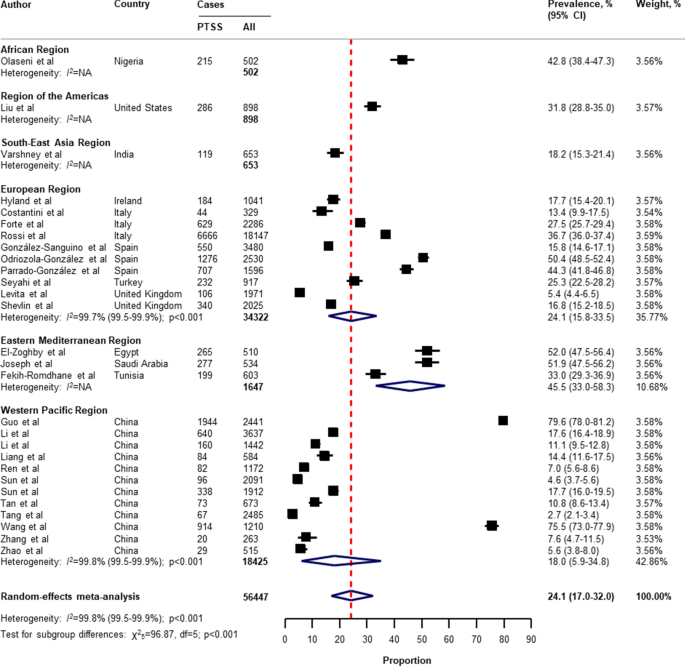

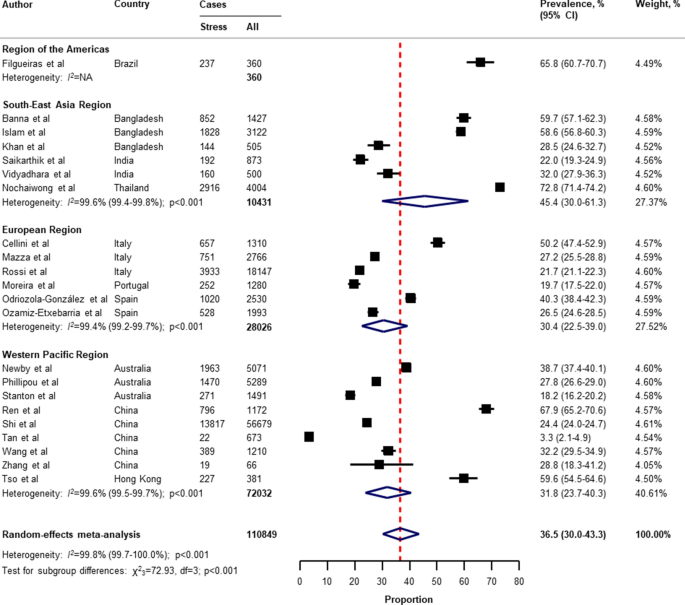

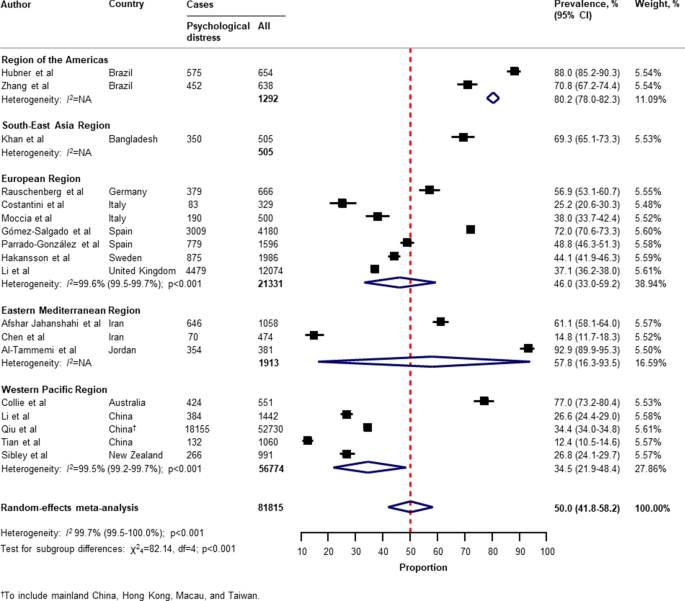

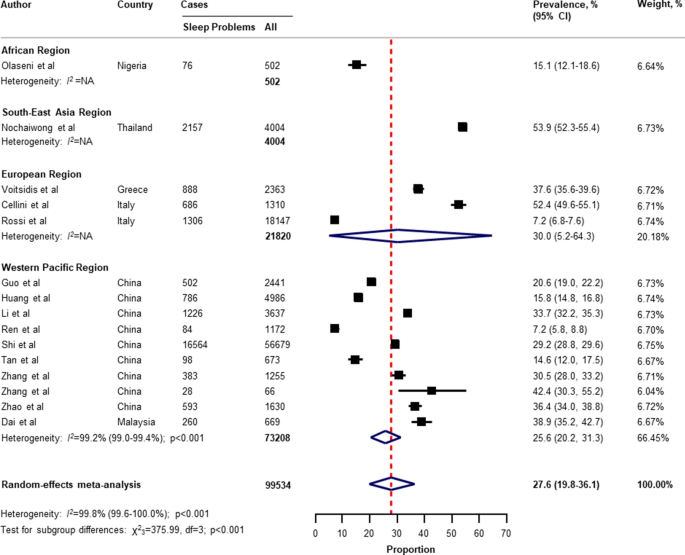

Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population amid the COVID-19 pandemic

Table 2 presents a summary of the results of the prevalence of mental health problems among the general population amid the COVID-19 pandemic by WHO region and World Bank country groups. With substantial heterogeneity, the global prevalence was 28.0% (95% CI 25.0–31.2) for depression (75 studies 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 57 , 58 , 60 , 61 , 64 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 87 , 88 , 91 , 93 , 96 , 97 , 99 , 101 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 , 108 , 109 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 116 , 117 , 119 , 120 , 122 , 124 , 125 , 126 , 127 , 129 , 130 , 131 , 132 , 133 , 134 , 136 , 138 , 139 , 140 , n = 280,607, Fig. 1 ); 26.9% (95% CI 24.0–30.0) for anxiety (75 studies 35 , 37 , 38 , 40 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 46 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 57 , 58 , 60 , 61 , 64 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 71 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 87 , 88 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 104 , 105 , 107 , 108 , 109 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117 , 119 , 120 , 122 , 124 , 125 , 126 , 129 , 130 , 131 , 132 , 133 , 134 , 136 , 138 , 139 , 140 , n = 284,813, Fig. 2 ); 24.1% (95% CI 17.0–32.0) for PTSS (28 studies 35 , 44 , 56 , 59 , 62 , 64 , 66 , 69 , 75 , 78 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 106 , 109 , 110 , 111 , 119 , 123 , 124 , 125 , 127 , 131 , 135 , 138 , n = 56,447, Fig. 3 ); 36.5% (95% CI 30.0–43.3) for stress (22 studies 37 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 57 , 58 , 71 , 73 , 75 , 76 , 80 , 114 , 117 , 119 , 120 , 122 , 125 , 129 , 131 , 136 , n = 110,849, Fig. 4 ); 50.0% (95% CI 41.8–58.2) for psychological distress (18 studies 39 , 47 , 52 , 59 , 63 , 65 , 70 , 72 , 78 , 79 , 85 , 86 , 88 , 102 , 110 , 118 , 121 , 128 , n = 81,815, Fig. 5 ); and 27.6% (95% CI 19.8–36.1) for sleep problems (15 studies 35 , 53 , 58 , 80 , 84 , 103 , 106 , 107 , 109 , 119 , 120 , 125 , 134 , 136 , 137 , n = 99,534, Fig. 6 ). The prevalence of mental health problems based on different countries varied (Appendix, Table S6 ), from 14.5% (South Africa) to 63.3% (Brazil) for depressive symptoms; from 7.7% (Vietnam) to 49.9% (Mexico) for anxiety; from 10.5% (United Kingdom) to 52.0% (Egypt) for PTSS; from 19.7% (Portugal) to 72.8% (Thailand) for stress; from 23.9% (China) to Jordan (92.9%) for psychological distress; from 9.2% (Italy) to 53.9% (Thailand) for sleep problems.

Pooled prevalence of depression among the general population amid the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, CI confidence interval, df degree of freedom, NA not applicable. References are listed according to WHO region in the appendix, Table S3 .

Pooled prevalence of anxiety among the general population amid the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, CI confidence interval, df degree of freedom, NA not applicable. References are listed according to WHO region in the appendix, Table S3 .

Pooled prevalence of PTSS among the general population amid the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, CI confidence interval, df degree of freedom, NA not applicable, PTSS post-traumatic stress symptoms. References are listed according to WHO region in the appendix, Table S3 .

Pooled prevalence of stress among the general population amid the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, CI confidence interval, df degree of freedom, NA not applicable. References are listed according to WHO region in the appendix, Table S3 .

Pooled prevalence of psychological distress among the general population amid the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, CI confidence interval, df degree of freedom, NA not applicable. References are listed according to WHO region in the appendix, Table S3 .

Pooled prevalence of sleep problems among the general population amid the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, CI confidence interval, df degree of freedom, NA not applicable. References are listed according to WHO region in the appendix, Table S3 .

With respect to the small number of included studies and high degree of heterogeneity, the pooled secondary outcome prevalence estimates are presented in Appendix, Table S7 . The global prevalence was 16.4% (95% CI 4.8–33.1) for suicide ideation (4 studies 36 , 41 , 53 , 124 , n = 17,554); 53.8% (95% CI 42.4–63.2) for loneliness (3 studies 41 , 44 , 45 , n = 2921); 30.7% (95% CI 2.1–73.3) for somatic symptoms (3 studies 53 , 69 , 134 , n = 7230); 28.6% (95% CI 9.2–53.6) for low wellbeing (3 studies 53 , 68 , 97 , n = 15,737); 50.5% (95% CI 49.2–51.7) for alcohol drinking problems (2 studies 97 , 114 , n = 6145); 6.4% (95% CI 5.5–7.4) for obsessive–compulsive symptoms (2 studies 73 , 134 , n = 2535); 25.7% (95% CI 23.7–27.8) for panic disorder (1 study 74 , n = 1753); 2.4% (95% CI 1.6–3.4) for phobia anxiety (1 study 134 , n = 1255); 22.8% (95% CI 22.1–23.4) for adjustment disorder (1 study 80 , n = 18,147); and 1.2% (95% CI 1.0–1.4) for suicide attempts (1 study 36 , n = 10,625).

Subgroup analyses, sensitivity analyses, meta-regression analyses, and publication bias

In the subgroup analyses (Appendix, Table S8 , Table S9 , Table S10 , Table S1 , Table S12 ), the prevalence of mental health problems was higher in countries with a low to medium HDI (for depression, anxiety, PTSS, and psychological distress), high HDI (for sleep problems), high gender inequality index (for depression and PTSS), very stringent government response index (for PTSS and stress), less stringent government response index (for sleep problems), low to medium hospital beds per 10,000 people (for depression, anxiety, PTSS, stress, psychological distress, and sleep problems), low to medium current health expenditure (for depression, PTSS, and psychological distress), estimated percent change of real GDP growth 2020 below − 3.0 (for psychological distress), low resilience (fourth-quartile) of business environment (for depression, anxiety, and PTSS), medium resilience (second-quartile) of business environment (for psychological distress, and sleep problems), high economic vulnerability-inbound tourism expenditure (for psychological distress, sleep problems), article type-short communication/letter/correspondence (for stress), cross-sectional survey (for PTSS and psychological distress), longitudinal survey (for anxiety and stress), non-mainland China (for depression, anxiety, and psychological distress), sample size of less than 1000 (for psychological distress), sample size of more than 5000 (for PTSS), proportion of females more than 60% (for stress and sleep problems), and measurement tools (for depression, anxiety, stress, and sleep problems). However, several pre-planned subgroup analyses based on participant characteristics and secondary outcomes reported could not be performed due to limited data in the included studies.

Findings from the sensitivity analysis were almost identical to the main analysis (Appendix, Table S14 ). The pooled prevalence by restricting the analysis to studies with a low risk of bias was 28.6% (95% CI 25.1–32.3) for depression, 27.4% (95% CI 24.1–30.8) for anxiety, 30.2% (95% CI 20.3–41.1) for PTSS, 40.1% (95% CI 32.5–47.9) for stress, 45.4% (95% CI 32.0–59.2) for psychological distress, and 27.7% (95% CI 19.4–36.9) for sleep problems.

On the basis of univariate meta-regression, the analysis was suitable for the primary outcomes (Appendix, Table S15 ). The increased prevalence of mental health problems was associated with the WHO region (for depression, anxiety, and psychological distress), female gender inequality index (for depression and anxiety), the COVID-19-government response stringency index during the survey (for sleep problems), hospital beds per 10,000 people (for depression and anxiety), immediate economic vulnerability-inbound tourism expenditure (for sleep problems), study design (cross-sectional vs longitudinal survey; for stress), surveyed country (mainland China vs non-mainland China; for depression and psychological distress), and risk of bias (for PTSS).

The visual inspection of the funnel plots, and the p values tested for asymmetry using the Begg’s and Egger’s tests for each prevalence outcome, indicated no evidence of publication bias related to the sample size (Appendix, Table S16 , and Figure S2 ).

This study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first systematic review and meta-analysis on the overall global prevalence of mental health problems and psychosocial consequences among the general population amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, our findings indicate wide variability in the prevalence of mental health problems and psychosocial consequences across countries, particularly in relation to different regions, the global index of COVID-19 pandemic preparedness, inequalities, and economic vulnerabilities indices.

Two reports examined the global prevalence of common mental health disorders among adults prior to the COVID-19 outbreak. The first study was based on 174 surveys across 63 countries from 1980 to 2013. The estimated lifetime prevalence was 29.1% for all mental disorders, 9.6% for mood disorders, 12.9% for anxiety disorders, and 3.4% for substance use disorder 141 . Another report which was conducted as part of the Global Health Estimates by WHO in 2015, showed that the global estimates of depression and anxiety were 4.4% and 3.6% (more common among females than males), respectively 142 . Despite the different methodological methods used, our findings show that the pooled prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic is higher than before the outbreak.

Previous studies on the prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic have had substantial heterogeneity. Three systematic reviews reported the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among the general population (mainly in mainland China). The first of these by Salari et al. 11 , was based on 17 included studies (from ten different countries in Asia, Europe, and the Middle East), the pooled prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress were 33.7% (95% CI 27.5–40.6), 31.9% (95% CI 27.5–36.7), and 29.6% (95% CI 24.3–35.4), respectively. A review by Luo et al. 8 , which included 36 studies from seven different countries, reported a similar overall prevalence of 27% (95% CI 22–33) for depression and 32% (95% CI 25–39) for anxiety. However, a review by Ren et al. 17 , which focussed on only the Chinese population (8 included studies), found that the pooled prevalence was 29% (95% CI 16–42) and 24% (95% CI 16–32), respectively. Nevertheless, previous systematic reviews have been mainly on investigating the prevalence of PTSS, psychological distress, and sleep problems among the patients or healthcare workers that are limited to the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. With regard to the general population, a review by Cénat et al. 143 , found that the pooled prevalence of PTSS, psychological distress, and insomnia were 22.4% (95% CI 7.6–50.3; 9 included studies), 10.2% (95% CI 4.6–21.0; 10 included studies), and 16.5% (95% CI 8.4–29.7; 8 included studies), respectively.

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we updated and summarised the global prevalence of mental health problems and psychosocial consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic using information from 32 different countries, and 398,771 participants. A range of problems, including depression, anxiety, PTSS, stress, psychological distress, and sleep problems were reported. The global prevalence of our findings was in line with the previous reviews mentioned above in terms of depression (28.0%; 95% CI 25.0–31.2), anxiety (26.9%; 95% CI 24.0–30.0), and stress (36.5%; 95% CI 30.0–43.3). Interestingly, our findings highlight the poverty impacts of COVID-19 in terms of inequalities, the preparedness of countries to respond, and economic vulnerabilities on the prevalence of mental health problems across countries. For instance, our results suggest that countries with a low or medium HDI had a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety compared to countries with a high or very high HDI (Appendix, Table S8 , and Table S9 ). The prevalence of depression was higher among countries with a gender inequality index of 0.439 or greater (39.6% [95% CI 30.3–49.3] vs 26.2% [95% CI 23.1–29.3]; P = 0.020; Appendix, Table S8 ). Likewise, the prevalence of depression and anxiety was higher among countries with low hospital beds per 10,000 people (Appendix, Table S8 , and Table S9 ). Our findings suggest that the poverty impacts of COVID-19 are likely to be quite significant and related to the subsequent risk of mental health problems and psychosocial consequences. Although we performed a comprehensive review by incorporating articles published together with preprint reports, there was only limited data available on Africa, low-income groups, and secondary outcomes of interest (psychological distress, suicide ideation, suicide attempts, loneliness, somatic symptoms, wellbeing, alcohol drinking problems, obsessive–compulsive symptoms, panic disorder, phobia anxiety, and adjustment disorder).

Strengths and limitations of this review

From a methodological point of view, we used a rigorous and comprehensive approach to establish an up-to-date overview of the evidence-based information on the global prevalence of mental health problems amid the COVID-19 pandemic, with no language restrictions. The systematic literature search was extensive, comprising published peer-reviewed articles and preprints reporting data to present all relevant literature, minimise bias, and up to date evidence. Our findings expanded and addressed the limitations of the previous systematic reviews, such as having a small sample size and number of included studies, considered more aspects of mental health circumstance, and the generalisability of evidence at a global level 5 , 6 , 11 , 17 , 18 . To address biases from different measurement tools of assessment and the cultural norms across countries, we summarised the prevalence of mental health problems and psychosocial consequences using a random-effects model to estimate the pooled data with a more conservative approach. Lastly, the sensitivity analyses were consistent with the main findings, suggesting the robustness of our findings. As such, our data can be generalised to individuals in the countries where the included studies were conducted.

There were several limitations to this systematic review and meta-analysis. First, despite an advanced comprehensive search approach, data for some geographical regions according to the WHO regions and World Bank income groups, for instance, the Africa region, as well as the countries in the low-income group, were limited. Moreover, the reporting of key specific outcomes, such as suicide attempts and ideation, alcohol drinking or drug-dependence problems, and stigma towards COVID-19 infection were also limited. Second, a subgroup analysis based on participant characteristics (that is, age, sex, unemployment, history of mental illness, financial problems, and quarantine status), could not be performed as not all of the included studies reported this data. Therefore, the global prevalence of mental health problems and psychosocial consequences amid the COVID-19 pandemic cannot be established. Third, it should be noted that different methods, for example, face-to-face interviews or paper-based questionnaires, may lead to different prevalence estimates across the general population. Due to physical distancing, the included studies in this review mostly used online surveys, which can be prone to information bias and might affect the prevalence estimates of our findings. Fourth, a high degree of heterogeneity between the included studies was found in all outcomes of interest. Even though we performed a set of subgroup analyses concerning the participant characteristics, study characteristics, the global index, and economic indices responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, substantial heterogeneity persisted. However, the univariate meta-regression analysis suggested that the WHO region, gender inequality index, COVID-19-government response stringency index during the survey, hospital beds, immediate economic vulnerability (inbound tourism expenditure), study design, surveyed country (mainland China vs non-mainland China), and risk of bias were associated with an increased prevalence of mental health problems and psychosocial consequences amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, we underline that the diagnostic cut-off criteria used were not uniform across the measurement tools in this review, and misclassification remains possible. The genuine variation in global mental health circumstances across countries cannot be explained by our analyses. Indeed, such variation might be predisposed by social and cultural norms, public resilience, education, ethnic differences, and environmental differences among individual study populations.

Implications for public health and research

Despite the limitations of our findings, this review provides the best available evidence that can inform the epidemiology of public mental health, implement targeted initiatives, improving screening, and reduce the long-term consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly among low-income countries, or those with high inequalities, low preparedness, and high economic vulnerability. Our findings could be improved by further standardised methods and measurement tools of assessment. There is a need for individual country-level data on the mental health problems and psychosocial consequences after the COVID-19 pandemic to track and monitor public health responses. There are a number network longitudinal surveys being conducted in different countries that aim to improve our understanding of the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic 144 . To promote mental wellbeing, such initiatives could also be advocated for by public health officials and governments to increase awareness and provide timely proactive interventions in routine practice.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this systematic review and meta-analysis provides a more comprehensive global overview and evidence of the prevalence of mental health problems among the general population amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The results of this study reveal that the mental health problems and psychosocial consequences amid the COVID-19 pandemic are a global burden, with differences between countries and regions observed. Moreover, equality and poverty impacts were found to be factors in the prevalence of mental health problems. Studies on the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health status among the general population at a global level is needed. Given the high burden of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic, an improvement of screening systems and prevention, prompt multidisciplinary management, and research on the social and economic burden of the pandemic, are crucial.

Data sharing

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Mahase, E. Covid-19: WHO declares pandemic because of “alarming levels” of spread, severity, and inaction. BMJ 368 , m1036 (2020).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Pfefferbaum, B. & North, C. S. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 383 , 510–512 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Burki, T. K. Coronavirus in China. Lancet Respir. Med. 8 , 238 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Chen, Q. et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry 7 , e15–e16 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Vindegaard, N. & Benros, M. E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav. Immun. 89 , 531–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048 (2020).

Pappa, S. et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 88 , 901–907 (2020).

Salazar de Pablo, G. et al. Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physical and mental health of health care workers: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 275 , 48–57 (2020).

Luo, M., Guo, L., Yu, M., Jiang, W. & Wang, H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 291 , 113190 (2020).

Brooks, S. K. et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395 , 912–920 (2020).

Kaufman, K. R., Petkova, E., Bhui, K. S. & Schulze, T. G. A global needs assessment in times of a global crisis: world psychiatry response to the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Open 6 , e48 (2020).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Salari, N. et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob. Health 16 , 57 (2020).

Article Google Scholar

Kawohl, W. & Nordt, C. COVID-19, unemployment, and suicide. Lancet Psychiatry 7 , 389–390 (2020).

Frasquilho, D. et al. Mental health outcomes in times of economic recession: a systematic literature review. BMC Public Health 16 , 115 (2016).

World Bank. Global Economic Prospects, June 2020 (World Bank, 2020).

Book Google Scholar

Kovacevic, M. & Jahic, A. COVID-19 and Human Development: Exploring Global Preparedness and Vulnerability (Human Development Report Office, UNDP, 2020).

Google Scholar

Conceicao, P. et al. COVID-19 and Human Development: Assessing the Crisis, Envisioning the Recovery (Human Development Report Office, UNDP, 2020).

Ren, X. et al. Mental health during the Covid-19 outbreak in China: a meta-analysis. Psychiatr. Q. 91 (4), 1033–1045. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-020-09796-5 (2020).

Rogers, J. P. et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 7 , 611–627 (2020).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J. & Altman, D. G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339 , b2535 (2009).

Stroup, D. F. et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 283 , 2008–2012 (2000).

Hoy, D. et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 65 , 934–939 (2012).

Viera, A. J. & Garrett, J. M. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam. Med. 37 , 360–363 (2005).

PubMed Google Scholar

Nyaga, V. N., Arbyn, M. & Aerts, M. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health 72 , 39 (2014).

Cochran, W. G. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics 10 , 101–129 (1954).

Higgins, J. P. & Thompson, S. G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 21 , 1539–1558 (2002).

Human Development Report Office. Human Development Report 2019–Beyond Income, Beyond Averages, Beyond Today: Inequalities in Human DEVELOPMENT in the 21st century (United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2019).

Human Development Report Office. 2020 Human Development Persepctives: Tackling Social Norms–A game changer for gender inequalities (United National Development Programme (UNDP), 2020).

Hale, T. et al. Variation in government responses to COVID-19. Version 6.0. Blavatnik School of Government Working Paper. https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/covidtracker (2020).

International Monetary Fund (IMF). World Economic Outlook (April 2020), Real GDP growth Annual percent change . Accessed 29 July 2020. https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD (2020).

FM Global. 2020 FM Global Resilience Index: Make a Resilient Decision . Accessed 30 July 2020. https://www.fmglobal.com/research-and-resources/tools-and-resources/resilienceindex (2020).

Begg, C. B. & Mazumdar, M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50 , 1088–1101 (1994).

Article CAS PubMed MATH Google Scholar

Egger, M., Davey Smith, G., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315 , 629–634 (1997).

Duval, S. & Tweedie, R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 56 , 455–463 (2000).

Kim, A. W., Nyengerai, T. & Mendenhall, E. Evaluating the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in urban South Africa: perceived risk of COVID-19 infection and childhood trauma predict adult depressive symptoms. medRxiv. 2020.2006.2013.20130120 (2020).

Olaseni, A., Akinsola, O., Agberotimi, S. & Oguntayo, R. Psychological distress experiences of Nigerians amid COVID-19 pandemic. PsyArXiv May 6. 1031234/osfio/9v78y (2020).

Bryan, C., Bryan, A. O. & Baker, J. C. Associations among state-level physical distancing measures and suicidal thoughts and behaviors among U.S. adults during the early COVID-19 pandemic. PsyArXiv May 29 . 1031234/osfio/9bpr4 (2020).

Filgueiras, A. & Stults-Kolehmainen, M. Factors linked to changes in mental health outcomes among Brazilians in quarantine due to COVID-19. medRxiv. 2020.2005.2012.20099374 (2020).

Garcia-Priego, B. A. et al. Anxiety, depression, attitudes, and internet addiction during the initial phase of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic: a cross-sectional study in Mexico. medRxiv. 2020.2005.2010.20095844 (2020).

Hubner, C. v. K., Bruscatto, M. L. & Lima, R. D. Distress among Brazilian university students due to the Covid-19 pandemic: survey results and reflections. medRxiv. 2020.2006.2019.20135251 (2020).

Kantor, B. N. & Kantor, J. Mental health outcomes and associations during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey of the US general population. medRxiv. 2020.2005.2026.20114140 (2020).

Killgore, W. D. S., Cloonan, S. A., Taylor, E. C. & Dailey, N. S. Loneliness: a signature mental health concern in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 290 , 113117 (2020).

Lan, F.-Y., Suharlim, C., Kales, S. N. & Yang, J. Association between SARS-CoV-2 infection, exposure risk and mental health among a cohort of essential retail workers in the United States. medRxiv. 2020.2006.2008.20125120 (2020).

Lee, S. A., Jobe, M. C. & Mathis, A. A. Mental health characteristics associated with dysfunctional coronavirus anxiety. Psychol. Med. 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172000121X (2020).

Liu, C. H., Zhang, E., Wong, G. T. F., Hyun, S. & Hahm, H. C. Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical implications for U.S. young adult mental health. Psychiatry Res. 290 , 113172 (2020).

Rosenberg, M., Luetke, M., Hensel, D., Kianersi, S. & Herbenick, D. Depression and loneliness during COVID-19 restrictions in the United States, and their associations with frequency of social and sexual connections. medRxiv. 2020.2005.2018.20101840 (2020).

Sartorao Filho, C. I. et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health of medical students: a cross-sectional study using GAD-7 and PHQ-9 questionnaires. medRxiv. 2020.2006.2024.20138925 (2020).

Zhang, S. X., Wang, Y., Afshar Jahanshahi, A., Li, J. & Haensel Schmitt, V. G. Mental distress of adults in Brazil during the COVID-19 crisis. medRxiv. 2020.2004.2018.20070896 (2020).

Ahmad, A., Rahman, I. & Agarwal, M. Factors influencing mental health during COVID-19 outbreak: an exploratory survey among Indian population. medRxiv. 2020.2005.2003.20081380 (2020).

Balhara, Y. P. S., Kattula, D., Singh, S., Chukkali, S. & Bhargava, R. Impact of lockdown following COVID-19 on the gaming behavior of college students. Indian J. Public Health. 64 , S172-176 (2020).

Banna, H. A. et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of the adult population in Bangladesh: a nationwide cross-sectional study. PsyArXiv May 24 . 1031234/osfio/chw5d. (2020).

Islam, M. S. et al. Psychological eesponses during the COVID-19 outbreak among university students in Bangladesh. PsyArXiv June 2 . 1031234/osfio/cndz7. (2020).

Khan, A. H. et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health & wellbeing among home-quarantined Bangladeshi students: a cross-sectional pilot study. PsyArXiv May 15 . 1031234/osfio/97s5r. (2020).

Nochaiwong, S. et al. Mental health circumstances among health care workers and general public under the pandemic situation of COVID-19 (HOME-COVID-19). Medicine (Baltimore) 99 , e20751 (2020).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Saikarthik, J., Saraswathi, I. & Siva, T. Assessment of impact of COVID-19 outbreak & lockdown on mental health status & its associated risk and protective factors in adult Indian population. medRxiv. 2020.2006.2013.20130153 (2020).

Sigdel, A. et al. Depression, anxiety and depression-anxiety comorbidity amid COVID-19 pandemic: an online survey conducted during lockdown in Nepal. medRxiv. 2020.2004.2030.20086926 (2020).

Varshney, M., Parel, J. T., Raizada, N. & Sarin, S. K. Initial psychological impact of COVID-19 and its correlates in Indian Community: an online (FEEL-COVID) survey. PLoS ONE 15 , e0233874 (2020).

Vidyadhara, S., Chakravarthy, A., Pramod Kumar, A., Sri Harsha, C. & Rahul, R. Mental health status among the South Indian pharmacy students during Covid-19 pandemic quarantine period: a cross-sectional study. medRxiv. 2020.2005.2008.20093708 (2020).

Cellini, N., Canale, N., Mioni, G. & Costa, S. Changes in sleep pattern sense of time and digital media use during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. J. Sleep Res. 29 , e13074 (2020).

Costantini, A. & Mazzotti, E. Italian validation of CoViD-19 Peritraumatic Distress Index and preliminary data in a sample of general population. Riv. Psichiatr. 55 , 145–151 (2020).

Ebrahimi, O., Hoffart, A. & Johnson, S. U. The mental health impact of non-pharmacological interventions aimed at impeding viral transmission during the COVID-19 pandemic in a general adult population and the factors associated with adherence to these mitigation strategies. PsyArXiv May 9 . 1031234/osfio/kjzsp. (2020).

Fancourt, D., Steptoe, A. & Bu, F. Trajectories of depression and anxiety during enforced isolation due to COVID-19: longitudinal analyses of 59,318 adults in the UK with and without diagnosed mental illness. medRxiv. 2020.2006.2003.20120923 (2020).

Forte, G., Favieri, F., Tambelli, R. & Casagrande, M. COVID-19 pandemic in the Italian population: validation of a post-traumatic stress disorder questionnaire and prevalence of PTSD symptomatology. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 , 4151 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gómez-Salgado, J., Andrés-Villas, M., Domínguez-Salas, S., Díaz-Milanés, D. & Ruiz-Frutos, C. Related health factors of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 , 3947 (2020).

Article PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

González-Sanguino, C. et al. Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain Behav. Immun. 87 , 172–176 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Håkansson, A. Changes in gambling behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: a web survey study in Sweden. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 , 4013 (2020).

Hyland, P. et al. Anxiety and depression in the Republic of Ireland during the COVID-19 pandemic. PsyArXiv April 22. 1031234/osfio/8yqxr. (2020).

Jia, R. et al. Mental health in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: early observations. medRxiv. 2020.2005.2014.20102012 (2020).

Kwong, A. S. F. et al. Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in two longitudinal UK population cohorts. medRxiv. 2020.2006.2016.20133116 (2020).

Levita, L. et al. Impact of Covid-19 on young people aged 13–24 in the UK- preliminary findings. PsyArXiv June 30. 1031234/osfio/uq4rn. (2020).

Li, L. Z. & Wang, S. Prevalence and predictors of general psychiatric disorders and loneliness during COVID-19 in the United Kingdom: results from the Understanding Society UKHLS. medRxiv. 2020.2006.2009.20120139 (2020).

Mazza, C. et al. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: immediate psychological responses and associated factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 , 3165 (2020).

Moccia, L. et al. Affective temperament, attachment style, and the psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak: an early report on the Italian general population. Brain Behav. Immun. 87 , 75–79 (2020).

Moreira, P. S. et al. Protective elements of mental health status during the COVID-19 outbreak in the Portuguese population. medRxiv. 2020.2004.2028.20080671 (2020).

Munoz-Navarro, R., Cano-Vindel, A., Schmitz, F., Cabello, R. & Fernandez-Berrocal, P. Emotional distress and associated sociodemographic risk factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in Spain. medRxiv. 2020.2005.2030.20117457 (2020).

Odriozola-González, P., Planchuelo-Gómez, Á., Irurtia, M. J. & de Luis-García, R. Psychological effects of the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown among students and workers of a Spanish university. Psychiatry Res. 290 , 113108 (2020).

Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N., Idoiaga Mondragon, N., Dosil Santamaría, M. & Picaza Gorrotxategi, M. Psychological symptoms during the two stages of lockdown in response to the COVID-19 outbreak: an investigation in a sample of citizens in Northern Spain. Front. Psychol. 11 , 1491 (2020).

Özdin, S. & Bayrak Özdin, Ş. Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: the importance of gender. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 66 , 504–511 (2020).

Parrado-González, A. & León-Jariego, J. C. Covid-19: factors associated with emotional distress and psychological morbidity in Spanish population. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 94 , e202006058 (2020).

Rauschenberg, C. et al. Social isolation, mental health and use of digital interventions in youth during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationally representative survey. PsyArXiv June 29 . 1031234/osfio/v64hf (2020).

Rossi, R. et al. COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. An N = 18147 web-based survey. medRxiv. 2020.2004.2009.20057802 (2020).

Seyahi, E., Poyraz, B. C., Sut, N., Akdogan, S. & Hamuryudan, V. The psychological state and changes in the routine of the patients with rheumatic diseases during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Turkey: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Rheumatol. Int. 40 , 1229–1238 (2020).

Shevlin, M. et al. Anxiety, depression, traumatic stress, and COVID-19 related anxiety in the UK general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. PsyArXiv April 18. 1031234/osfio/hb6nq (2020).

Smith, L. E. et al. Factors associated with self-reported anxiety, depression, and general health during the UK lockdown; a cross-sectional survey. medRxiv. 2020.2006.2023.20137901 (2020).

Voitsidis, P. et al. Insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic in a Greek population. Psychiatry Res. 289 , 113076 (2020).

Afshar Jahanshahi, A., Mokhtari Dinani, M., Nazarian Madavani, A., Li, J. & Zhang, S. X. The distress of Iranian adults during the Covid-19 pandemic: more distressed than the Chinese and with different predictors. medRxiv. 2020.2004.2003.20052571 (2020).

Al-Tammemi, A. a. B., Akour, A. & Alfalah, L. Is it just about physical health? An internet-based cross-sectional study exploring the psychological impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on university students in Jordan using Kessler psychological distress scale. medRxiv. 2020.2005.2014.20102343 (2020).

Alyami, H. S. et al. Depression and anxiety during 2019 coronavirus disease pandemic in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. medRxiv. 2020.2005.2009.20096677 (2020).

Chen, J. et al. The curvilinear relationship between the age of adults and their mental health in Iran after its peak of COVID-19 cases. medRxiv. 2020.2006.2011.20128132 (2020).

El-Zoghby, S. M., Soltan, E. M. & Salama, H. M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and social support among adult Egyptians. J. Community Health 45 , 689–695 (2020).

Fekih-Romdhane, F., Ghrissi, F., Abbassi, B., Cherif, W. & Cheour, M. Prevalence and predictors of PTSD during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from a Tunisian community sample. Psychiatry Res. 290 , 113131 (2020).

Joseph, R., Alshayban, D., Lucca, J. M. & Alshehry, Y. A. The immediate psychological response of the general population in Saudi Arabia during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. medRxiv. 2020.2006.2019.20135533 (2020).

Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, A. Assessing the anxiety level of Iranian general population during COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J. Psychiatr. 51 , 102076 (2020).

Naser, A. Y. et al. Mental health status of the general population, healthcare professionals, and university students during 2019 coronavirus disease outbreak in Jordan: a cross-sectional study. Brain Behav. 10 (8), e01730. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1730 (2020).

Saddik, B. et al. Assessing the influence of parental anxiety on childhood anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Arab Emirates. medRxiv. 2020.2006.2011.20128371 (2020).

Saddik, B. et al. Increased levels of anxiety among medical and non-medical university students during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Arab Emirates. medRxiv. 2020.2005.2010.20096933 (2020).

Salman, M. et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on Pakistani university students and how they are coping. medRxiv. 2020.2005.2021.20108647 (2020).

Ahmed, M. Z. et al. Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated psychological problems. Asian J. Psychiatr. 51 , 102092 (2020).

Cao, W. et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 287 , 112934 (2020).

Chang, J., Yuan, Y. & Wang, D. Mental health status and its influencing factors among college students during the epidemic of COVID-19. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 40 , 171–176 (2020).

Chen, S. H. et al. Public anxiety and its influencing factors in the initial outbreak of COVID-19. Fudan Univ. J. Med. Sci. 47 , 385–391 (2020).

Choi, E. P. H., Hui, B. P. H. & Wan, E. Y. F. Depression and anxiety in Hong Kong during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 , 3740 (2020).

Collie, A. et al. Psychological distress among people losing work during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. medRxiv. 2020.2005.2006.20093773 (2020).

Dai, H., Zhang, S. X., Looi, K. H., Su, R. & Li, J. Health condition and test availability as predictors of adults' mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv. 2020.2006.2021.20137000 (2020).

Elhai, J. D., Yang, H., McKay, D. & Asmundson, G. J. G. COVID-19 anxiety symptoms associated with problematic smartphone use severity in Chinese adults. J. Affect. Disord. 274 , 576–582 (2020).

Gao, J. et al. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE 15 , e0231924 (2020).

Guo, J., Feng, X. L., Wang, X. H. & van IJzendoorn, M. H. Coping with COVID-19: exposure to COVID-19 and negative impact on livelihood predict elevated mental health problems in Chinese adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 , 3857 (2020).

Huang, Y. & Zhao, N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 288 , 112954 (2020).

Lei, L. et al. Comparison of prevalence and associated factors of anxiety and depression among people affected by versus people unaffected by quarantine during the COVID-19 epidemic in Southwestern China. Med. Sci. Monit. 26 , e924609 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Insomnia and psychological reactions during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. J Clin. Sleep Med. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8524 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Psychological distress among health professional students during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychol. Med. 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720001555 (2020).

Liang, L. et al. The effect of COVID-19 on youth mental health. Psychiatr. Q. 91 (3), 841–852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-020-09744-3 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Online mental health survey in a medical college in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Front. Psychiatry 11 , 459 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Psychological status and behavior changes of the public during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Infect. Dis. Poverty 9 , 58 (2020).

Newby, J., O'Moore, K., Tang, S., Christensen, H. & Faasse, K. Acute mental health responses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. medRxiv. 2020.2005.2003.20089961 (2020).

Nguyen, H. T. et al. Fear of COVID-19 scale-associations of its scores with health literacy and health-related behaviors among medical students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 , 4164 (2020).

Ni, M. Y. et al. Mental health, risk factors, and social media use during the COVID-19 epidemic and cordon sanitaire among the community and health professionals in Wuhan, China: cross-sectional survey. JMIR Ment. Health 7 , e19009 (2020).

Phillipou, A. et al. Eating and exercise behaviors in eating disorders and the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: initial results from the COLLATE project. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 53 , 1158–1165 (2020).

Qiu, J. et al. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr. 33 , e100213 (2020).

Ren, Y. et al. Letter to the Editor “A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China”. Brain Behav. Immun. 87 , 132–133 (2020).

Shi, L. et al. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms among the general population in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 3 , e2014053 (2020).

Sibley, C. G. et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and nationwide lockdown on trust, attitudes toward government, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 75 , 618–630 (2020).

Stanton, R. et al. Depression, anxiety and stress during COVID-19: associations with changes in physical activity, sleep, tobacco and alcohol use in Australian adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 , 4065 (2020).

Sun, L. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of acute posttraumatic stress symptoms during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China. medRxiv. 2020.2003.2006.20032425 (2020).

Sun, S., Goldberg, S. B., Lin, D., Qiao, S. & Operario, D. Psychiatric symptoms, risk, and protective factors among university students in quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. medRxiv. 2020.2007.2003.20144931 (2020).

Tan, W. et al. Is returning to work during the COVID-19 pandemic stressful? A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain Behav. Immun. 87 , 84–92 (2020).

Tang, F. et al. COVID-19 related depression and anxiety among quarantined respondents. Psychol. Health 36 (2), 164–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2020.1782410 (2020).

Tang, W. et al. Prevalence and correlates of PTSD and depressive symptoms one month after the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic in a sample of home-quarantined Chinese university students. J. Affect. Disord. 274 , 1–7 (2020).

Tian, F. et al. Psychological symptoms of ordinary Chinese citizens based on SCL-90 during the level I emergency response to COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 288 , 112992 (2020).

Tso, I. F. & Sohee, P. Alarming levels of psychiatric symptoms and the role of loneliness during the COVID-19 epidemic: a case study of Hong Kong. PsyArXiv published online June 27. 1031234/osfio/wv9y2 (2020).

Ueda, M., Stickley, A., Sueki, H. & Matsubayashi, T. Mental health status of the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional national survey in Japan. medRxiv. 2020.2004.2028.20082453 (2020).

Wang, C. et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 , 1729 (2020).

Wang, Y., Di, Y., Ye, J. & Wei, W. Study on the public psychological states and its related factors during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in some regions of China. Psychol. Health Med. 26 (1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.1746817 (2020).

Ying, Y. et al. Mental health status among family members of health care workers in Ningbo, China during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak: a Cross-sectional Study. medRxiv. 2020.2003.2013.20033290 (2020).

Zhang, W. R. et al. Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychother. Psychosom. 89 , 242–250 (2020).

Zhang, Y. & Ma, Z. F. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and quality of life among local residents in Liaoning Province, China: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 , 2381 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Zhang, H., Ma, X. & Di, Q. Mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemics and the mitigation effects of exercise: a longitudinal study of college students in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 , 3722 (2020).

Zhao, X., Lan, M., Li, H. & Yang, J. Perceived stress and sleep quality among the non-diseased general public in China during the 2019 coronavirus disease: a moderated mediation model. Sleep Med. S1389–9457 (1320), 30224–30220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.021 (2020).

Zhao, Y., An, Y., Tan, X. & Li, X. Mental health and its influencing factors among self-isolating ordinary citizens during the beginning epidemic of COVID-19. J. Loss Trauma https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.15322020.11761592 (2020).

Zhou, S. J. et al. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 29 , 749–758 (2020).

Zhu, S. et al. The immediate mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic among people with or without quarantine managements. Brain Behav.. Immun. 87 , 56–58 (2020).

Steel, Z. et al. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. Int. J. Epidemiol. 43 , 476–493 (2014).

World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates (World Health Organization, 2017).

Cénat, J. M. et al. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 295 , 113599 (2021).

COVID-MINDS Network. COVID-MINDS network: global mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic , https://www.covidminds.org/ (2020).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the research assistances and all staff of Pharmacoepidemiology and Statistics Research Center (PESRC), Chiang Mai, Thailand. This work reported in this manuscript was partially supported by a grant by the Chiang Mai University, Thailand. The funder of the study had no role in the study design collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit it for publication.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Pharmaceutical Care, Faculty of Pharmacy, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, 50200, Thailand

Surapon Nochaiwong, Chidchanok Ruengorn, Ratanaporn Awiphan, Chabaphai Phosuya & Yongyuth Ruanta

Pharmacoepidemiology and Statistics Research Center (PESRC), Faculty of Pharmacy, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, 50200, Thailand

Surapon Nochaiwong, Chidchanok Ruengorn, Kednapa Thavorn, Ratanaporn Awiphan & Yongyuth Ruanta

Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, ON, K1H 8L6, Canada

Kednapa Thavorn & Brian Hutton

Institute of Clinical and Evaluative Sciences, ICES uOttawa, Ottawa, ON, K1Y 4E9, Canada

School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, K1G 5Z3, Canada

Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, 50200, Thailand

Nahathai Wongpakaran & Tinakon Wongpakaran

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

S.N. conceived the study and, together with C.R., K.T., R.A., C.P., and Y.R. developed the protocol. S.N. and C.R. did the literature search, selected the studies. S.N. and Y.R. extracted the relevant information. S.N. synthesised the data. S.N. wrote the first draft of the paper. K.T., B.H., N.W., and T.W. critically revised successive drafts of the paper. All authors approved the final draft of the manuscript. SN is the guarantor of the study.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Surapon Nochaiwong .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary figures and tables., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Nochaiwong, S., Ruengorn, C., Thavorn, K. et al. Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 11 , 10173 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89700-8

Download citation

Received : 11 January 2021

Accepted : 29 April 2021

Published : 13 May 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89700-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Enhancing mental wellbeing by changing mindsets results from two randomized controlled trials.

- Carina Schreiber

- Marijke Schotanus-Dijkstra

BMC Psychology (2024)

Protocol for a pilot cluster randomised controlled trial of a multicomponent sustainable return to work IGLOo intervention

- Oliver Davis

- Jeremy Dawson

- Fehmidah Munir

Pilot and Feasibility Studies (2024)

The global prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disorder among patients coping with Post COVID-19 syndrome (long COVID): a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Niloofar Seighali

- Abolfazl Abdollahi

- Mahmood Bakhtiyari

BMC Psychiatry (2024)

Effectiveness of gamified digital interventions in mental health prevention and health promotion among adults: a scoping review

- Leona Aschentrup

- Pia Anna Steimer

- Kamil J. Wrona

BMC Public Health (2024)

The relationships between perceived mental illness prevalence, mental illness stigma, and attitudes toward help-seeking

- Alexander Chang

- Paul Handal

Current Psychology (2024)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Disclaimer » Advertising

- HealthyChildren.org

Selection Criteria

Search strategy, data extraction, risk of bias and applicability, data synthesis and analysis, parent ratings, teacher ratings, youth self-reports, combined rating scales, additional clinician tools, neuropsychological tests, biospecimen, neuroimaging, variation in diagnostic accuracy with clinical setting or patient subgroup, measures for diagnostic performance, available tools, importance of the comparator sample, clinical implications, future research, conclusions, acknowledgments, tools for the diagnosis of adhd in children and adolescents: a systematic review.

FUNDING: The work is based on research conducted by the Southern California Evidence-based Practice Center under contract to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Rockville, MD (Contract 75Q80120D00009). The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) funded the research (PCORI Publication No. 2023-SR-03). The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors, who are responsible for its contents; the findings and conclusions do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ or PCORI, its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee. Therefore, no statement in this report should be construed as an official position of PCORI, AHRQ or of the US Department of Health and Human Services.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES: The authors have indicated they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- CME Quiz Close Quiz

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Bradley S. Peterson , Joey Trampush , Morah Brown , Margaret Maglione , Maria Bolshakova , Mary Rozelle , Jeremy Miles , Sheila Pakdaman , Sachi Yagyu , Aneesa Motala , Susanne Hempel; Tools for the Diagnosis of ADHD in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2024; e2024065854. 10.1542/peds.2024-065854

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Correct diagnosis is essential for the appropriate clinical management of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents.

This systematic review provides an overview of the available diagnostic tools.

We identified diagnostic accuracy studies in 12 databases published from 1980 through June 2023.

Any ADHD tool evaluation for the diagnosis of ADHD, requiring a reference standard of a clinical diagnosis by a mental health specialist.

Data were abstracted and critically appraised by 1 reviewer and checked by a methodologist. Strength of evidence and applicability assessments followed Evidence-based Practice Center standards.

In total, 231 studies met eligibility criteria. Studies evaluated parental ratings, teacher ratings, youth self-reports, clinician tools, neuropsychological tests, biospecimen, EEG, and neuroimaging. Multiple tools showed promising diagnostic performance, but estimates varied considerably across studies, with a generally low strength of evidence. Performance depended on whether ADHD youth were being differentiated from neurotypically developing children or from clinically referred children.

Studies used different components of available tools and did not report sufficient data for meta-analytic models.

A valid and reliable diagnosis of ADHD requires the judgment of a clinician who is experienced in the evaluation of youth with and without ADHD, along with the aid of standardized rating scales and input from multiple informants across multiple settings, including parents, teachers, and youth themselves.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most prevalent neurodevelopmental conditions in youth. Its prevalence has remained constant at ∼5.3% worldwide over the years, and diagnostic criteria have remained constant when based on rigorous diagnostic procedures. 1 Clinical diagnoses, however, have increased steadily over time, 2 and currently, ∼10% of US children receive an ADHD diagnosis. 3 Higher rates of clinical compared with research-based diagnoses are because of an increasing clinician recognition of youth who have ADHD symptoms that are functionally impairing but do not fully meet formal diagnostic criteria. 4 The higher diagnostic rates over time in clinical samples also results from youth receiving a diagnosis incorrectly. Some youth, for example, are misdiagnosed as having ADHD when they have symptoms of other disorders that overlap with ADHD symptoms, such as difficulty concentrating, which occurs in many other conditions. 5 Moreover, ADHD is more than twice as likely to be diagnosed in boys than in girls, 3 in lower-income families, 6 and in white compared with nonwhite youth 7 ; differences that derive at least in part from diagnostic and cultural biases. 8 , – 11

Improving clinical diagnostic accuracy is essential to ensure that youth who truly have ADHD benefit from receiving treatment without delay. Similarly, youth who do not have ADHD should not be diagnosed since an incorrect diagnosis risks exposing them to unbeneficial treatments. 12 , 13 Clinician judgement alone, however, especially by nonspecialist clinicians, is poor in diagnosing ADHD 14 compared with expert, research-grade diagnoses made by mental health clinicians. 15 Accurately diagnosing ADHD is difficult because diagnoses are often made using subjective clinical impressions, and putative diagnostic tools have a confusing, diverse, and poorly described evidence base that is not widely accessible. The availability of valid diagnostic tools would especially help to reduce misdiagnoses from cultural biases and symptom overlap with ADHD. 12 , 16 , – 19

This review summarizes evidence for the performance of tools for children and adolescents with ADHD. We did not restrict to a set of known diagnostic tools but instead explored the range of available diagnostic tools, including machine-learning assisted and virtual reality-based tools. The review aimed to assess how diagnostic performance varies by clinical setting and patient characteristics.

The review aims were developed in consultation with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the topic nominator American Academy of Pediatrics, key informants, a technical expert panel (TEP), and public input. The TEP reviewed the protocol and advised on key outcomes. Subgroup analyses and key outcomes were prespecified. The review is registered in PROSPERO (CRD42022312656) and the protocol is available on the AHRQ Web site as part of a larger evidence report on ADHD. The systematic review followed Methods of the (AHRQ) Evidence-based Practice Center Program. 20

Population: age <18 years.

Interventions: any ADHD tool for the diagnosis of ADHD.