- About Grants

Sample Project Outcomes

A key component of an interim or final Research Performance Progress Report (RPPR) is the Project Outcomes summary (Section I). Project Outcomes provide information regarding the cumulative outcomes or findings of the project and are made public through NIH RePORTER.

As noted in the RPPR Instruction Guide , Project Outcome summaries should not exceed half a page and must be written according to the following guidelines:

- Is written for the general public in clear, concise, and comprehensible language

- Is suitable for dissemination to the general public, as the information may be available electronically

- Does not include proprietary, confidential information or trade secrets

Recipients conducting NIH-defined Phase III Clinical Trials must also include results of valid analyses by sex/gender, race, and ethnicity in the Project Outcome Summary (see Example 1 below). For more information on valid analysis, see the Analyses by Sex or Gender, Race and Ethnicity for NIH-defined Phase III Clinical Trials (Valid Analysis) page.

Example 1: Project Outcomes Summary for “The VITamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL (VITAL)”

Note: this example includes the results of valid analyses by sex/gender, race, and ethnicity required for NIH-defined Phase III Clinical Trials.

Project: “The VITamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL (VITAL) Contact PI: JoAnn E. Manson Organization: Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School

The VITAL trial investigated whether taking high-dose vitamin D and/or omega-3 fatty acid supplements daily impacts the risk of cancer or cardiovascular disease among generally healthy midlife and older adults. Study participants were followed for an average of five years.

We found that overall, neither vitamin D supplementation (2000 IU daily) nor omega-3 fatty acid supplementation (1 g daily) reduced the risk of total invasive cancer. However, vitamin D supplementation did result in a 17% overall reduction in cancer death, although this was not statistically significant. With vitamin D supplementation, there were no differences between men and women in the cancer risk findings. However, a small and borderline significant 23% decrease in total cancer incidence was observed among African-American participants. In the overall cohort, advanced cancers (metastatic plus fatal cancers) were significantly decreased. With omega-3 fatty acid supplementation, women had a small nonsignificant reduction in risk of total invasive cancer, while men had no risk reduction.

Taking daily moderate-to-high dose vitamin D supplements did not reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events such as stroke, heart attack, or cardiovascular death. These results were not significantly different when comparing men and women or when comparing participants from different racial or ethnic groups.

Similarly, omega-3 fatty acid supplementation did not result in reduced risk of major cardiovascular events for the overall study population. However, there were some differences by subgroup and the type of cardiovascular event. Among those with lower-than-average fish intake at baseline, omega-3 fatty acid supplementation reduced the risk of major cardiovascular events by 19%. When heart attack was analyzed separately, omega-3 fatty acid supplementation resulted in a 28% reduction in the risk of heart attack (similar reduction in men and women), with the greatest benefit (77% reduction) observed among African-Americans. A significant reduction in heart attack was also observed among those with lower-than-average dietary fish intake and those with two or more risk factors for heart attack.

Example 2: Project Outcomes Summary for “Heart Rate Recovery and Mortality” (R01HL066004)

Project: “Heart Rate Recovery and Mortality” Contact PI: Michael S Lauer, MD Organization: Cleveland Clinic

During exercise, heart rate increases to meet increasing muscle demands for blood. Immediately after exercise, heart rate decreases. We call the decrease in heart rate after exercise “heart rate recovery.” Scientists believe that heart rate recovery reflects the the “autonomic nervous system,” the part of the nervous system that we are not aware of. It regulates “automatic” functions like heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing. It turns out that heart rate falls faster in people who are in good physical shape. In work we did before getting this grant, we found that slower falls in heart rate predicted a higher risk of early death. In this project, we analyzed data from tens of thousands of Cleveland Clinic patients who had exercise tests as part of their routine care. Our technicians recorded heart rate every few minutes during exercise and one minute after exercise. These were some of our main findings:

- We confirmed that heart rate recovery predicts death.

- Heart rate recovery is lower in people with diabetes and in people who have more severe heart disease; even so, low heart rate recovery predicts death in people with diabetes and in people with severe heart disease.

- Heart rate recovery is lower in older adults, and predicts death in older adults.

- Heart rate recovery is lower in people who are poor (in terms of money). We thought this might be true because some scientists think that people who are poor may suffer from problems with their nervous systems. Our finding may help us understand why poor people have higher risks of early death.

- We found that extra heart beats after exercise also predicts death. This finding may shed light on why people with low heart rate recovery have a higher risk of death: their nervous system problems may increase the risk of electrical problems with their hearts.

This page last updated on: October 5, 2022

- Bookmark & Share

- E-mail Updates

- Help Downloading Files

- Privacy Notice

- Accessibility

- National Institutes of Health (NIH), 9000 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, Maryland 20892

- NIH... Turning Discovery Into Health

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

Published on October 12, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on November 21, 2023.

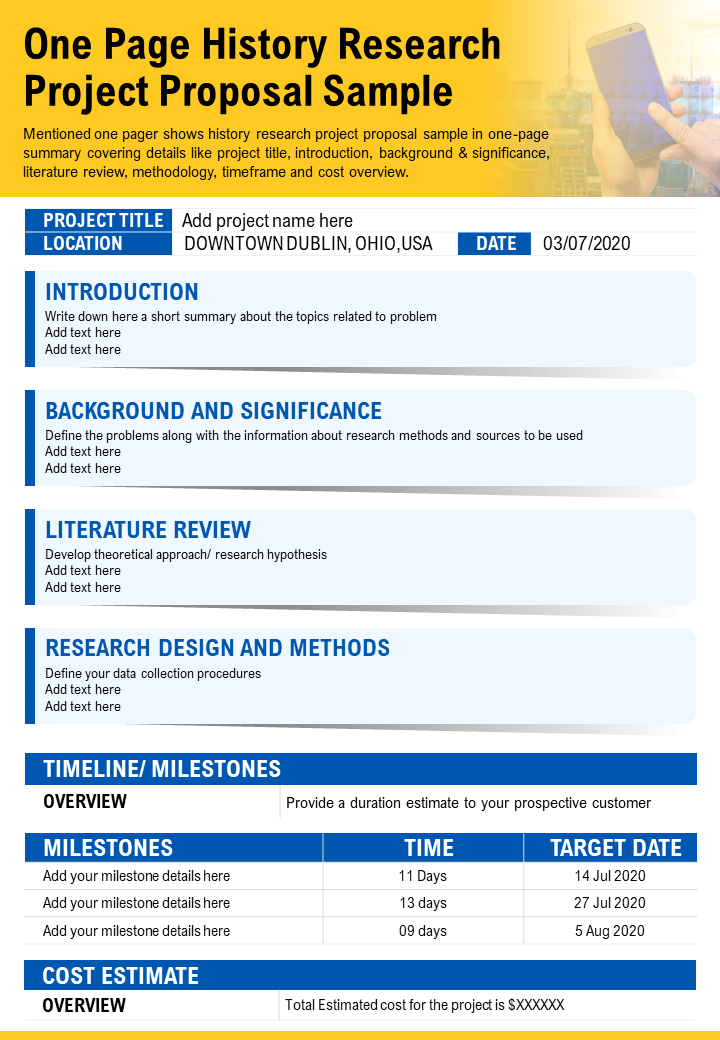

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research.

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organized and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

Table of contents

Research proposal purpose, research proposal examples, research design and methods, contribution to knowledge, research schedule, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research proposals.

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal as part of a grad school application , or prior to starting your thesis or dissertation .

In addition to helping you figure out what your research can look like, a proposal can also serve to demonstrate why your project is worth pursuing to a funder, educational institution, or supervisor.

Research proposal length

The length of a research proposal can vary quite a bit. A bachelor’s or master’s thesis proposal can be just a few pages, while proposals for PhD dissertations or research funding are usually much longer and more detailed. Your supervisor can help you determine the best length for your work.

One trick to get started is to think of your proposal’s structure as a shorter version of your thesis or dissertation , only without the results , conclusion and discussion sections.

Download our research proposal template

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing a research proposal can be quite challenging, but a good starting point could be to look at some examples. We’ve included a few for you below.

- Example research proposal #1: “A Conceptual Framework for Scheduling Constraint Management”

- Example research proposal #2: “Medical Students as Mediators of Change in Tobacco Use”

Like your dissertation or thesis, the proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.

Your introduction should:

- Introduce your topic

- Give necessary background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research questions

To guide your introduction , include information about:

- Who could have an interest in the topic (e.g., scientists, policymakers)

- How much is already known about the topic

- What is missing from this current knowledge

- What new insights your research will contribute

- Why you believe this research is worth doing

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have already done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own.

In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

- Comparing and contrasting the main theories, methods, and debates

- Examining the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches

- Explaining how will you build on, challenge, or synthesize prior scholarship

Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your own project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasize again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Last but not least, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use our free APA citation generator .

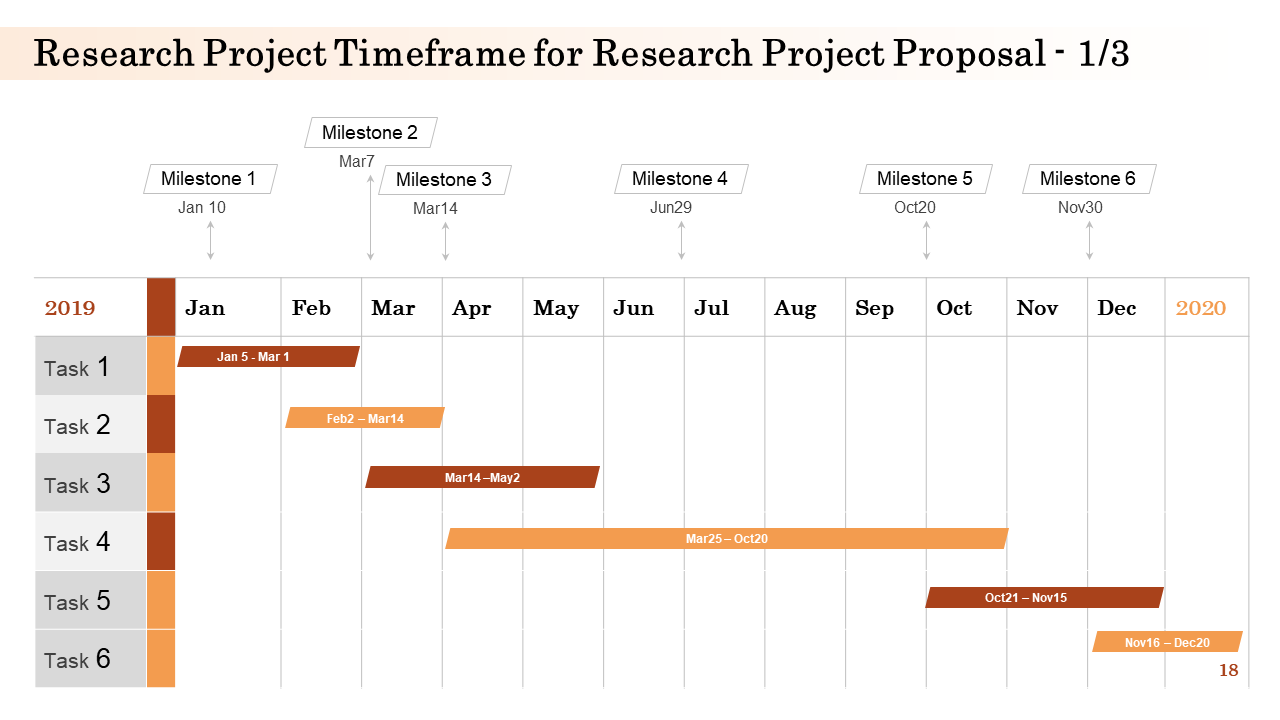

Some institutions or funders require a detailed timeline of the project, asking you to forecast what you will do at each stage and how long it may take. While not always required, be sure to check the requirements of your project.

Here’s an example schedule to help you get started. You can also download a template at the button below.

Download our research schedule template

If you are applying for research funding, chances are you will have to include a detailed budget. This shows your estimates of how much each part of your project will cost.

Make sure to check what type of costs the funding body will agree to cover. For each item, include:

- Cost : exactly how much money do you need?

- Justification : why is this cost necessary to complete the research?

- Source : how did you calculate the amount?

To determine your budget, think about:

- Travel costs : do you need to go somewhere to collect your data? How will you get there, and how much time will you need? What will you do there (e.g., interviews, archival research)?

- Materials : do you need access to any tools or technologies?

- Help : do you need to hire any research assistants for the project? What will they do, and how much will you pay them?

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

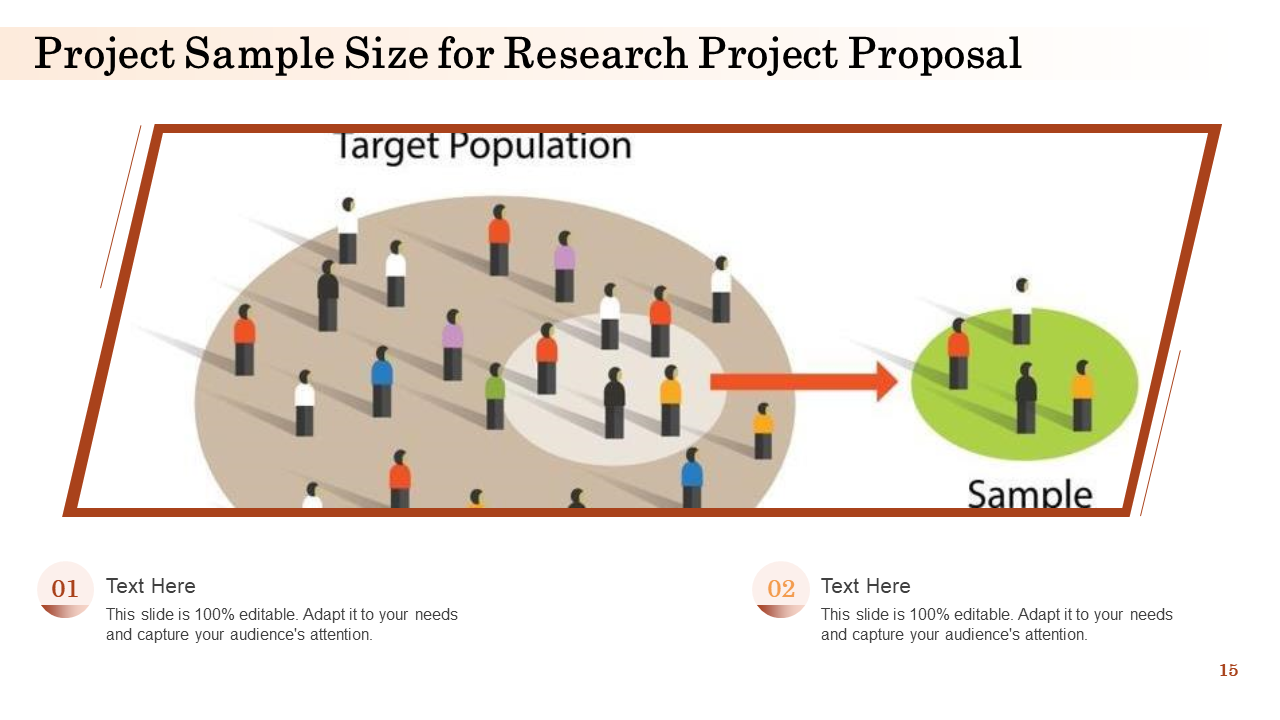

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement .

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

A PhD, which is short for philosophiae doctor (doctor of philosophy in Latin), is the highest university degree that can be obtained. In a PhD, students spend 3–5 years writing a dissertation , which aims to make a significant, original contribution to current knowledge.

A PhD is intended to prepare students for a career as a researcher, whether that be in academia, the public sector, or the private sector.

A master’s is a 1- or 2-year graduate degree that can prepare you for a variety of careers.

All master’s involve graduate-level coursework. Some are research-intensive and intend to prepare students for further study in a PhD; these usually require their students to write a master’s thesis . Others focus on professional training for a specific career.

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

The best way to remember the difference between a research plan and a research proposal is that they have fundamentally different audiences. A research plan helps you, the researcher, organize your thoughts. On the other hand, a dissertation proposal or research proposal aims to convince others (e.g., a supervisor, a funding body, or a dissertation committee) that your research topic is relevant and worthy of being conducted.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, November 21). How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Outcomes 101: A brief guide for conducting an outcomes research project as a surgeon-scientist in training

George q. zhang.

Department of Surgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Caitlin W. Hicks

Department of Vascular Surgery and Endovascular Therapy, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD, USA

1. Introduction

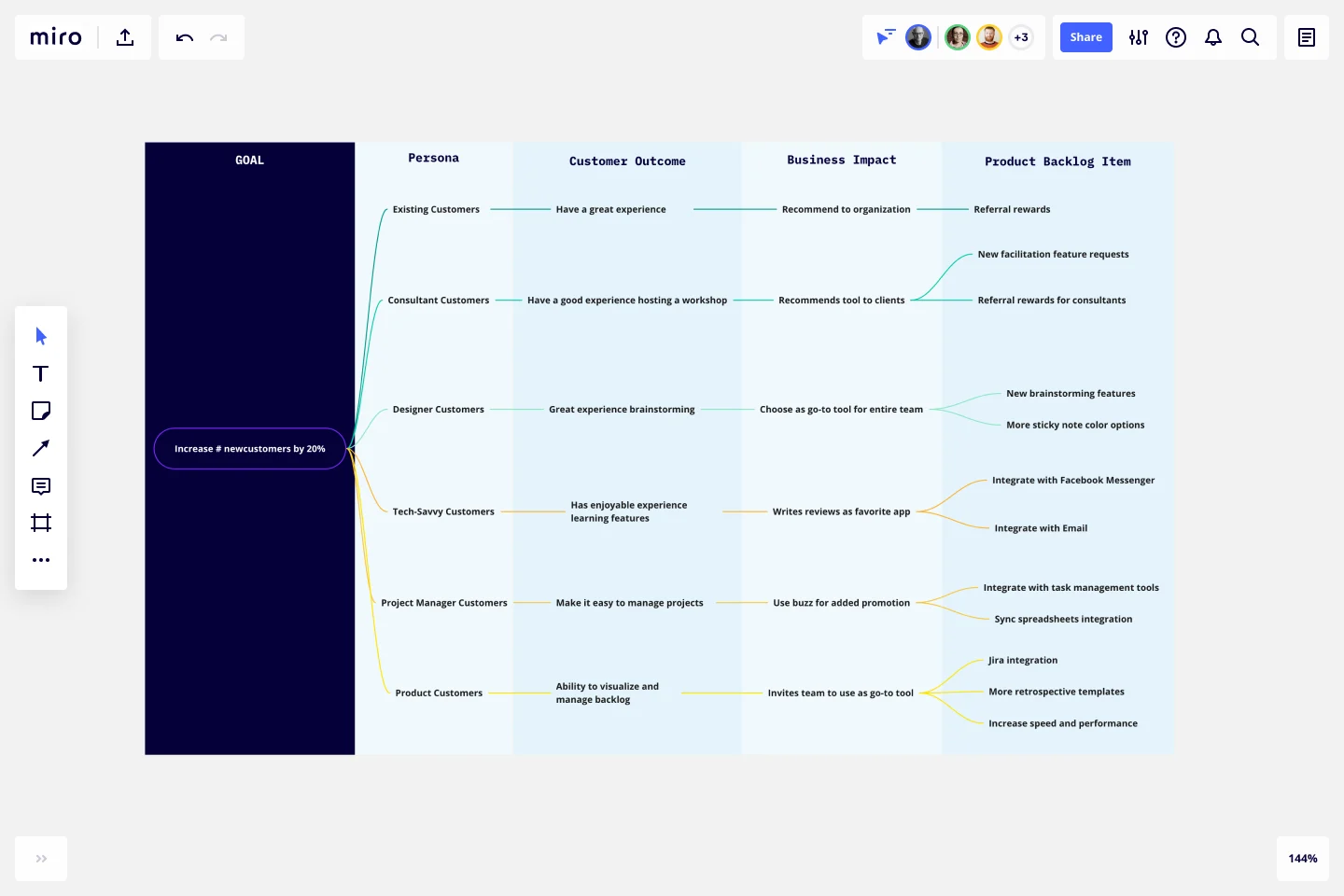

Research has become a major component of many surgical training programs in recent decades as the concept of the surgeon-scientist continues to grow. Surgical residents become involved in research for a variety of reasons, including to gain experience in a field of interest, 1 develop and foster relationships with mentors, 2 and increase competitiveness for future fellowship and employment endeavors. 3 However, these opportunities can often be difficult to obtain for a multitude of reasons, particularly in the context of a demanding clinical workload. 4 Here, we outline the basic steps of conducting a surgical outcomes project in an effort to make this valuable but daunting task more accessible to all trainees who are interested ( Fig. 1 ).

Suggested stepwise workflow for successfully completing a surgical outcomes research project.

1.1. Identify a topic and mentor

The first step to any successful research endeavor is to identify a topic of interest to you. This can be as broad or specific as you like, as long as it is an area that you are willing to devote a significant amount of time and effort into exploring. Finding the right mentor to champion you through a project is equally as important. These steps are interchangeable: you may find yourself approaching a mentor for their expertise and perspective on your own big idea, or be approached by a mentor with a clinical question who needs your help in translating it into a tangible body of work. Either arrangement can mark the start of a fruitful relationship, so long as there is mutual buy-in from both parties. If you don’t have a preexisting mentor, find one. Once you have identified your topic of interest, investigate which faculty are doing research related to that topic and ask them if you can get involved in a project. Positive attributes of a good mentor may include a consistent track record of publications, regular availability, prompt communication, and the endorsement of other trainees who have worked with them in the past. 5 It may take a few tries to find the right mentor-mentee fit, but be persistent and engaged and most faculty will be happy to work with you.

1.2. Identify a specific question and become an expert

Identifying a specific question that is novel, interesting, and achievable using the resources available to you can seem daunting. Some tips to achieve this include keeping up with the latest literature, taking part in educational activities throughout your institution, and approaching your day-to-day clinical activities with a keen eye to the gaps in current practice and clinical understanding. Attending academic meetings, both national and local, can also help you to identify what topics are most pertinent in your field of interest. Additionally, consider the questions you may come up with in the context of the time and experience that you have, data available to you, and expertise of your mentor.

Once you have settled upon a question of interest, fully delve into the field and become an expert in its particular subset of literature. Utilize your mentor to identify landmark papers, trials, and other must-reads in your area of study. Review articles are useful, as they commonly highlight the practice-changing literature in the field. If available to you, institutional librarians can be extraordinarily helpful to the literature review process, as they are experts in navigating the vast and complicated world of academic literature. Be sure to identify key relevant references within these articles not only for your own information, but to save for citations when you begin to write your manuscript. We recommend the use of a citation manager for this, as it can help you stay organized while streamlining the process of making your manuscript submission ready in the future. One important point to note is that you should now have all the resources needed to write your Introduction. This can certainly be done in parallel to the next steps in preparation for data analysis, and can often be easier to execute while the literature review is still fresh in your mind.

1.3. Define your study variables and choose a dataset

Once your question is adequately fleshed out, the next step is to develop a game plan for how exactly it will be answered. Determine what type of study is most suitable for addressing your given hypothesis (cohort studies, case-control studies, qualitative studies, etc.) and what variables you will want to analyze. Develop a primary outcome of interest and consider secondary outcomes that may contribute to your analysis. Additionally, consider what specific populations you would like to include and exclude such that your question can be most directly answered while minimizing bias. These questions should be answered with the help of your mentor, who will be familiar with key outcomes of interest related to the topic you are studying. Of note, your institution or mentor may be able to pair you with methodologists and/or statisticians who are a powerful resource throughout the study development and data acquisition/analysis phases. Use your mentor to understand what help is available, and involve others at an early stage so they can be of greatest benefit.

Choosing a dataset for analysis is another key step. There are a variety of national, regional, and institutional databases that your Department or mentor may have access to. Some may be readily available, while others will require additional steps for you and your mentor to obtain. Alternatively, primary data collection may be required, typically in the form of chart review. Determining what data is most suitable your needs should take into consideration the available variables and their relevance to your question, its completeness and usability, as well as applicability to your field of study (i.e., has it or similar data been used to answer similar questions in the literature before?).

Once you have selected a dataset, it is important to return to your selected variables and refine them in the context of your dataset. In particular, this is a good time to determine what covariates you may want to include in order to best interpret your data. Typical covariates may include demographic (age, sex, race, etc.), comorbidity (e.g. diabetes, coronary artery disease) and specialty-specific clinical factors. This is also a good time to review the literature and circle back with your mentor to ensure that you have all the variables necessary (and expected) for the proposed analysis. Any anticipated critical limitations may warrant revising your initial question or even selecting another dataset that better suits your needs. This process should be repeated as many times as needed to ensure that all key variables are available for your specific analysis. Of note, Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval is required prior to any data use, even for publicly available and deidentified datasets. Your mentor may have a pre-existing IRB protocol that he/she can add you to, or you may need to submit a new one.

1.4. Build your tables

For most surgical outcomes projects, the order of tables follows a standard format. Table 1 is typically used to describe baseline characteristics of your cohort. The primary groups of interest are displayed as columns, and your baseline demographic, clinical, and other relevant characteristics are reported as rows. An additional column may be utilized to compare proportions of characteristics among subgroups (i.e. P-values). Table 2 should reflect the crude outcomes – that is, the proportion of each subgroup with the primary and secondary outcomes. Table 3 should be used to depict adjusted outcomes from your multivariable analyses. These are typically presented as an adjusted odds ratio, 95% confidence interval, and significance of the association. Additional tables can be used for sensitivity or subgroup analyses as needed. There may be some variation to this arrangement depending on the question you are answering, but in general this structure will provide you with a reasonable summary of the data.

Baseline characteristics of Group A vs. Group B in the Example Database (start date-end date).

Crude (unadjusted) outcomes for Group A vs. Group B in the Example Database (start date-end date).

Association (Odds Ratio, 95% CI) * of exposure A with primary outcome in the Example Database (start date-end date).

The inclusion of figures is another important consideration and should be planned out during this phase as well. Remember that they are not simply to look pretty, and should not repeat the data already presented in your tables. Often, they will assist in improving interpretation of your findings and provide additional insight that is best depicted in a graphical manner.

One step that we recommend for any surgical outcomes project is to finalize the shell of all tables (aside from the data values themselves) prior to beginning any data analysis. This might seem counterintuitive, but spending the time to confirm the variables that you plan to include will save significant effort during later steps, when each minor change in methodology or variables of interest will result in major alterations in your results. Reviewing and finalizing blank tables with your mentor will help streamline your workflow during data analysis, such that the next steps will be as simple as filling in the blanks. In our opinion, this is arguably the most critical step to the successful design and execution of a surgical outcomes project.

1.5. Analyze the data

With the right preparation, data analysis should be relatively straightforward to execute. Take the time to ensure your data is clean, such that it is accurate, complete, and consistent to the fullest extent possible, prior to performing critical analyses. Identify and correct any obvious errors in the results that you see. Review your crude (unadjusted) results with your mentor to make sure they make sense in the context of what is already known about the topic you are studying prior to delving into more complicated analytic coding. Interpret the data as you go, and adjust/supplement your analysis plan as needed.

1.6. Write the paper

Similar to data analysis, the act of writing the manuscript should come relatively easy with a strong groundwork. We recommend completing the manuscript in the following sequence: Tables/Figures, Results, Methods, Discussion, Introduction, Abstract.

The Tables and Figures should be already completed at this point, and the Results should serve to highlight the important findings shown in those exhibits. Be careful to not be redundant in the Results section – although you will be reporting a large amount of data, it should still flow naturally for the average academic reader. Additionally, remember that the Results should only report the facts already presented in your Tables and Figures, and should avoid excessive interpretation.

The Methods section is intended to provide an explanation of the procedures used to conduct your study. The first subsection should describe your study cohort, including the database used, type of study, cohort/groups of interest, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and IRB statement. The second should depict your outcomes of interest, and give the reader an idea of what question you are trying to answer. The third should define your covariates of interest, as well as how they were obtained and measured. Finally, an overview of the statistical analyses performed should be provided.

The Discussion may feel like a daunting section to approach, but it can also be broken down in a formulaic manner. Remember that the Discussion is guided by your findings, and aim to structure it around 3–4 key points from your data. Each point should represent a paragraph in your Discussion, summarizing your findings and describing how it compares to the current literature. The goal is to place your data in the context of what is currently known, and to explain how it contributes to our understanding of the topic. The penultimate paragraph is traditionally a Limitations paragraph that describes potential shortcomings of your analysis. Do not hesitate to be critical, and be sure to highlight possible areas of follow-up that could help address your limitations in the future. The last paragraph is simply a Conclusion statement to highlight the take-home messages of your work.

Now that the rest of the paper is complete, take some time to revisit your Introduction. This should already be drafted from the literature review stage, but care should be taken now to ensure that your defined aim at the end is well-aligned with your final study plan.

Lastly, your Abstract should serve as a birds-eye view of your entire work. Briefly describe the Introduction/Background/Aims, Methods, Results, and Conclusion(s), ensuring that the text is succinct, but still understandable and representative. Sometimes an abstract is created as the initial step in communicating your data, such as for a submission to a meeting. In this case, be sure that the abstract is updated to reflect your overall analysis and take-home message.

2. Balancing a clinical workload with research

Oftentimes the major barrier to completing a surgical outcomes research project is lack of time, particularly for clinically busy surgical residents. While we advocate for a strict patient-first approach to clinical duties, there are a number of tricks that can increase your academic productivity. First, think of your project in a step-wise fashion. Each step stands on its own. This makes the task ahead much less daunting, and more easily achievable in a short period of time. Second, make use of down time. The potentially long operating room turnover times can easily be converted into a short work session if you set your mind to it, and may distract from the frustrations caused by inevitable delays. Third, make your work portable. Whether you use a virtual desktop that can be accessed from anywhere or carry a light-weight laptop in your bag, having access to your work in progress will make you much more inclined to be productive. Fourth, set regular meetings with your mentor. Weekly or biweekly check-in meetings will move the project along and keep both of you engaged. Finally, set internal deadlines for yourself. Most people function better with deadlines, and having a goal in mind gives yourself clear milestones and a sense of accomplishment at each step along the way.

3. Conclusion

Conducting a surgical outcomes research project can be a daunting task, particularly in the wake of a busy clinical workload. Careful up-front investment in finding the right mentor, conducting the background research to come up with a novel and feasible question, and preparing and finalizing your analytic plan prior to execution are critical and will make the process as streamlined as possible. There is certainty more than one way to conduct research and be successful at it, but we hope that this guide can provide you with a rough set of guidelines and demonstrate that there is, in fact, some method to the madness. Good luck, and enjoy!

Declaration of competing interest

The authors (GQZ, CWH) declare no relevant conflicts of interest. CWH is support by grants from the NIH/NIDDK (K23DK124515), American College of Surgeons, and Society for Vascular Surgery.

Abbreviations:

Contributor information.

George Q. Zhang, Department of Surgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Caitlin W. Hicks, Department of Vascular Surgery and Endovascular Therapy, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Reporting Research Outcomes

Dawn Atkinson

Chapter Overview

Much of what we are asked to do in academia and in the workplace involves research , which is loosely defined as systematic investigation undertaken with a goal in mind. Indeed, course research can take a wide variety of forms. In a history class, for instance, students might be tasked with researching the circumstances that contributed to a historical event. In a biology class, they might be asked to conduct a laboratory experiment to test a hypothesis. In a business course, they may be presented with a case study of a situation in a company and asked to research ways to respond to it. And in an engineering class, students may be expected to investigate the viability of a particular project or design. Workplace research projects can likewise be varied. An employee working in one organization may conduct an informational interview with someone working in another organization, for example, to determine the effectiveness of a particular product before recommending that it be purchased. A human resources professional might also survey employees to gauge their reaction to a company policy. A safety inspector, in comparison, might conduct a walk-through of a facility to review staff adherence to health and safety regulations.

Regardless of its purpose, a research project must be planned, executed, and reported with care for its findings to be valuable and useful. This chapter addresses these stages, focusing in particular on reporting research outcomes in APA-style reports.

How does an investigator begin a research project?

A research project often begins with a kernel of an idea, a thought about something that has the potential to drive further exploration. Whether the kernel is inspired by an assignment prompt, a piece of reading, a campus problem, a workplace issue, or personal curiosity, the objective is to turn the kernel into a pursuable topic for research. In broad terms, a pursuable topic is

- Manageable, meaning that it is not too broad or narrow.

- Defined in scope, meaning that its focus is delineated.

- Practicable, meaning that it can be investigated in a feasible way.

If you have the opportunity to propose an idea for a research project, also aim to identify a topic that is interesting to you to inspire momentum as you work.

Taking the above information into account, which of the following items, adapted from Reynolds Community College Libraries (2019b, “Sample Topic – Broadening Chart”; 2019c, p. 1), is a pursuable topic for a five- to seven-page research paper? Provide a rationale for your choice(s) in the space provided.

- Global warming

- Should state laws be enacted to ban texting and cellphone use while driving?

- How have government fishing regulations in the United States affected the freshwater fish population?

- What marketing strategies implemented by Publix Super Markets, Inc. have been successful in increasing the company’s sales in the Richmond, Virginia, area since it opened its location in the Short Pump Crossing Shopping Center in 2017?

The quest to identify a pursuable topic might begin with a brainstorming session to ascertain what you know about a subject, what you do not know, and what you wish to discover through research. Brainstorming techniques include the following.

- Listing all the ideas that come to mind about the topic without editing your work.

- Free writing by noting down anything you can think of about the topic.

- Answering who , what , when , where , why , how , and so what questions about the topic.

- Expressing the topic as a problem and creating an outline of its causes, effects, and potential solutions.

- Writing the topic in the center of a page and grouping offshoot ideas around that topic while using lines or arrows to show how the elements are connected (mind mapping).

A brainstorming session may help you to identify areas of interest regarding a topic and narrow the focus of a broad subject area.

To determine whether a topic is pursuable, you might also explore existing research in the area. Have other investigators studied the same topic? What have they found? What methods have they used? What time period, geographic location, or demographic have they focused on? Where have they reported their results? Are these reputable publication outlets? By exploring existing research, you can get a sense of what type of material already exists on the topic and what kind of contribution you might make to the research landscape.

Librarians can also offer invaluable advice about how to explore potential research topics. For instance, they can demonstrate how to efficiently and effectively use Google Scholar, a widely accessible internet search engine that provides access to peer-reviewed journal articles and other sources, as well as library databases , large, searchable online directories of research materials. Additionally, they can help you narrow search terms to maximize productive use of these resources by employing techniques similar to those outlined in Figure 1, from The Learning Portal, College Libraries Ontario (2020).

Figure 1. How to generate a keyword list to search a database

Effective internet and library research largely hinges on defining useful search terms, and librarians have considerable expertise in this area, making them excellent academic support resources.

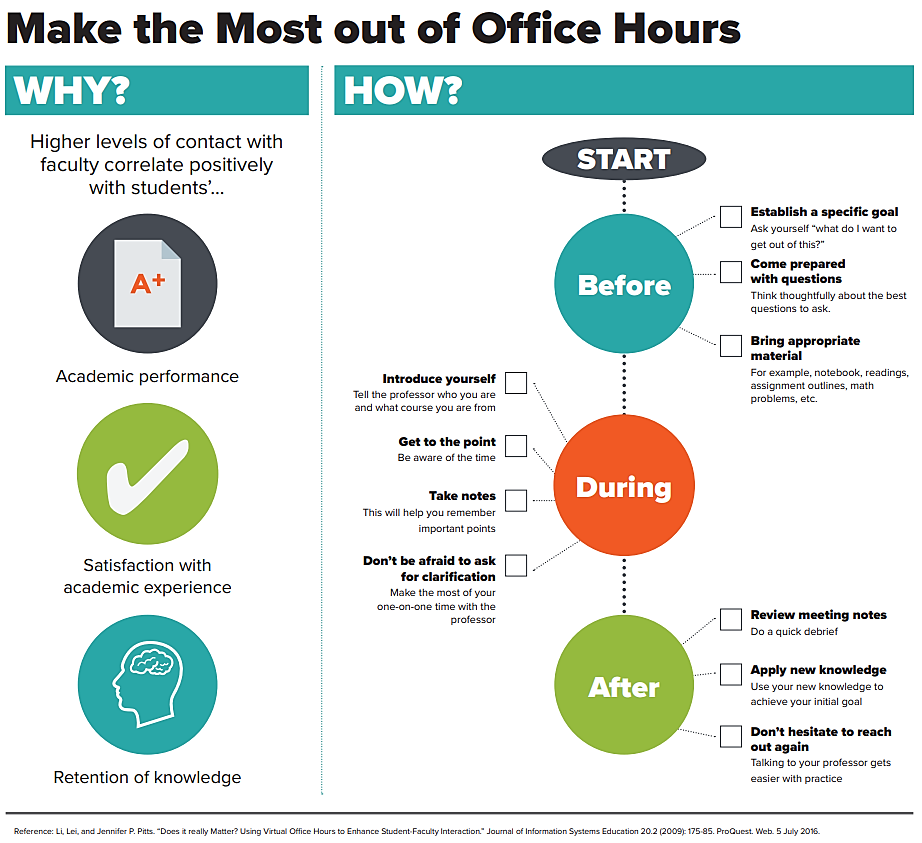

Also remember that your instructor is a valuable academic support resource who can help to resolve questions about assignments and encourage research efforts. Instructors build office hours into their work calendars each week—times when they are available to meet or talk with students—and these are opportunities to discuss research project as they take shape. Follow the guidance in Figure 2 to gain maximum benefit from office hour sessions.

Figure 2. “ Make the Most out of Office Hours ” is licensed under a CC BY NC SA 4.0 International Licens e

Do not hesitate to contact your instructor for help with a research project; after all, instructors were once novice researchers, so they can understand the complex nature of research undertakings.

How does an investigator develop research questions?

Upon identifying a pursuable topic, you might construct one or more research questions , questions a study seeks to answer, to help further define your project’s focus and direction. Depending on the discipline, instructor, or assignment, you might be expected to list the questions in your project deliverable. Alternatively, you might be expected to articulate your answer to the research questions in the form of a thesis statement that establishes your research report’s purpose and direction. Figure 3 illustrates how a research question can be converted into a thesis statement.

Try it yourself.

As Figure 3 explains, a thesis statement is the answer to a research question: it communicates a viewpoint reached as a result of research.

Research questions can determine a project’s agenda, scope, and approaches to data collection and analysis if they are purposefully constructed, so it is worth thinking about them carefully. In broad terms, a research question should precisely specify the focus of an investigation so that it can feasibly be pursued through inquiry. The multipage handout in Figure 4, adapted from the Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo (n.d.a), illustrates the process of moving from a pursuable topic to a research question and further defines the characteristics of effective research questions.

Develop A Research Question

A research question guides your research. It provides boundaries, so that when you gather resources you focus only on information that helps to answer your question. Without this guide, you would simply gather a collection of facts, not knowing when and where to end your search for information.

Where Do I Begin?

Good research questions come from solid research topics. For more information, see our resource Developing and Narrowing a Topic.

From a Topic to a Problem

Once you narrow your topic, you need to think about related problems. The goal of research is to answer questions that help to solve one of these larger problems. Using bicycle lanes in urban areas as our topic, we can start to generate some potential problems:

bicycle lanes in urban areas

Potential problems:

bike lanes are not being used

bike lanes interfere with traffic flow

bike lanes are not consistently integrated into cities

bike lanes are not being respected

Where do I find problems?

Look at current research on your topic in academic articles or reliable web sources. The motivation (or problem) behind others’ research is often discussed in the abstract or introduction.

From a Problem to a Question

Once you find a current problem that can help to motivate your research, you need to develop a question that helps to answer the problem. Let’s use one of the problems above as an example:

bike lanes are not consistently integrated into cities

Potential questions:

how does public perception of safety affect policy toward bike lane infrastructure?

how do economic incentives affect policy-making for bicycle lane infrastructure?

how do municipal level policies affect the design and building of bike lane infrastructure?

Tip: The mistake that most novice researchers make is to attempt to answer a question that’s too big to answer through a single research project. Keep it narrow.

Characteristics of effective research questions

Tip: To better understand disciplinary requirements for your research, talk to your professors and look for resources in your discipline.

Figure 4. The process of moving from a topic to constructing an effective research question

While the initial version of a research question can guide the course of a study, the question may also evolve with the project, so be prepared to adjust it as the research takes shape. The multipage handout in Figure 5, adapted from McLaughlin Library, University of Guelph (n.d.a), reinforces this point and offers a graphic organizer to help with constructing and refining research questions.

Figure 5. A guide to developing research questions

For a research question to be effective, it must be focused, as figures 4 and 5 emphasize.

How does an investigator conduct research?

During the process of identifying a pursuable research topic and question(s), an investigator must also consider what research methods to use. Research methods are means for conducting an investigation, and these should be selected with a study’s purpose in mind. The existing literature, context, scope, discipline, and timeline for a project will also help define what research methods are typical, practical, and useful.

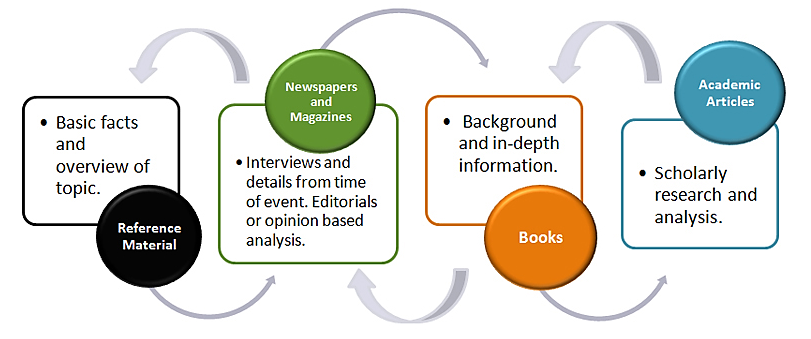

In terms of research approaches and methods, an investigator might use primary or secondary research or both when carrying out a project. Primary research is raw data that an investigator collects or examines firsthand; such information may be gathered, for example, through the use of interviews, questionnaires, experiments, or observations. The “Interviewing for Information” chapter of this textbook and its accompanying reading, “Introduction to Primary Research: Observations, Surveys, and Interviews” (Driscoll, 2011), discuss several of these research methods in detail. The “Conducting Primary Research” section of the Purdue Online Writing Lab ( https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/purdue_owl.html ) provides additional information about primary research. An investigator might decide to use primary research, for instance, to delve into a little studied topic, to gather first-person accounts of situations or events, or to uncover various perspectives on issues. Secondary research comprises previously conducted studies and organized accounts of what others have discovered or said about a topic. Secondary research can be found in journal articles, laboratory reports, governmental reports, trade publications, magazines, and newspapers, among other sources. By reading secondary research, an investigator can get a feel for the existing scholarship on a topic. In addition, a secondary research source can often lead to other useful sources on the same topic via means of its reference list. A librarian can help you search for useful secondary research sources for a project.

Although this chapter discusses research activities in a linear fashion in an effort to be clear, in reality, research processes are typically recursive, meaning they occur in repeated sequences and oftentimes involve different approaches and types of data sources. Textbook writers Hamlin et al. (2017b, p. 43) explain this point with an example. Imagine you are assigned a course research project. You might begin the project by trying to read journal articles on your chosen topic, only to discover you lack the necessary background knowledge to fully understand the articles. To increase your background knowledge, you might consult an encyclopedia or textbook on the topic. You may then encounter a statement in a newspaper editorial that inspires you to return to journal articles to see if existing research supports the statement. Figure 6 illustrates the recursive nature of research and resource use.

Figure 6. “ Cycle of Revolving Research ” is licensed under a CC BY NC SA 4.0 international license

Expect to engage with different sources of information at different times as you undertake a research project.

How does an investigator evaluate research information?

Whether you use primary research, secondary research, or both in a project, you have a responsibility as an ethical technical communicator to evaluate the quality of information you incorporate into a deliverable. Readers use research for various purposes—for example, to find out about new medical treatments, ways to use technology, or means for building structures—and they need accurate information to proceed safely and confidently. Looking at the issue another way, the worth of your own research can be called into question if you rely on questionable or disreputable sources. Evaluating the quality of research information is clearly an important task, as Figure 7, a handout adapted from the Excelsior Online Writing Lab (2020d), makes clear.

Can you think of other tips you might add to the handout?

Figure 7. “ Evaluating a Website ” is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 International license.

EvaluatingAWebsite2019

Although Figure 7 focuses on the trustworthiness of websites, the “Writing Topic Proposals” and “Writing Essays” chapters of this textbook provide additional guidance on how to evaluate the quality of various types of sources.

How does an investigator use research information?

As a research project takes shape and progresses, you will also need to think about the relationship of source information to your research deliverable. That is, what type of information will you use, and how will you use it? The following text, adapted from Hayden and Margolin (2020), discusses this point in further detail.

How to Use a Source: The BEAM Method

Different kinds of sources may be used for various purposes in a paper. The BEAM method, developed by Bizup (2008), may help you identify the usefulness of different types of sources. BEAM stands for B ackground, E xhibit, A rgument, and M ethod.

- Background : using a source to provide general information to explain a topic. For example, using a textbook chapter to explain what it means to interview for information.

- Exhibit : using a source as evidence or as a collection of examples to analyze. For a technical writing assignment, for instance, you might analyze a formal report. For a history paper, you might analyze a historical document. For a sociology paper, you might analyze the data from a study.

- Argument : using a source to engage its argument. For example, you might use an editorial from The New York Times on the value of higher education to refute in your own paper.

- Method : using a source’s way of analyzing an issue to apply to your own issue. For example, you might use a study’s methods, definitions, or conclusions on gentrification in Chicago to apply to your own neighborhood in New York City.

Bizup, J. (2008). BEAM: A rhetorical vocabulary for teaching research-based writing. Rhetoric Review , 27 (1), 72-86. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350190701738858

Using the BEAM method as inspiration, we can create the graphic organizer in Table 1 to guide our efforts to match sources to purposes in a deliverable. Note that the number of source cells can be reduced or increased depending on the research project.

A graphic organizer for matching sources to their purposes in a deliverable

A graphic organizer like the one in Table 1 offers a visual layout of how different types of sources might be used and how they ultimately tie back to a research question.

In addition to determining what types of sources might be useful for what purposes in a deliverable, a researcher also needs to synthesize source information, in other words, combine it purposefully with the objective of creating something new, to make a contribution to the existing field of research. Figure 8, a multipage handout adapted from the Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo (n.d.b), illustrates the process of synthesis in a research project.

Analyzing Your Source

Many assignments ask you to critique and evaluate a source. Sources might include journal articles, books, websites, government documents, portfolios, podcasts, or presentations.

When you critique, you offer both negative and positive analysis of the content, writing, and structure of a source.

When you evaluate , you assess how successful a source is at presenting information, measured against a standard or certain criteria.

Elements of a critical analysis:

opinion + evidence from the article + justification

Your opinion is your thoughtful reaction to the piece.

Evidence from the article offers some proof to back up your opinion.

The justification is an explanation of how you arrived at your opinion or why you think it’s true.

How do you critique and evaluate?

When critiquing and evaluating someone else’s writing/research, your purpose is to reach an informed opinion about a source. In order to do that, try these three steps:

- Read and react to the piece. As you read, take notes. Record what the article means AND how you feel about it. Identify the parts that are worth talking about by asking

- How do you feel?

- What surprised you?

- What left you confused?

- What pleased or annoyed you?

- What was interesting?

- Ask deeper questions based on your reactions above.

- What is the purpose of this text?

- Who is the intended audience?

- What kind of bias is there?

- What was missing?

TIP: See our resource on analysis and synthesis ( Move From Research to Writing: How to Think ) for other examples of questions to ask.

3. Form an assessment.

The questions you asked in the last step should lead you to form an assessment. Here are some assessment/opinion words that might help you build your critique and evaluation:

illogical helpful sophisticated simplistic concise clear interesting undocumented insightful confusing disorganized creative deep superficial powerful not cited unconventional inappropriate interpretation of evidence unsound or discredited methodology traditional unsubstantiated unsupported well-researched easy to understand

4. Write your critique or evaluation using the opinion+ evidence from the text + jusitification model. Here is a sample:

Opinion : This article’s assessment of the power balance in cities is confusing.

Evidence: It first says that the power to shape policy is evenly distributed among citizens, local government, and business (Rajal, 232)

Justification : but then it goes on to focus almost exclusively on business. Next, in a much shorter section, it combines the idea of citizens and local government into a single point of evidence. This leaves the reader with the impression that the citizens have no voice at all. It is not helpful in trying to determine the role of the common voter in shaping public policy.

Sample criteria for critical analysis

Sometimes the assignment will specify what criteria to use when critiquing and evaluating a source. If not, consider the following prompts to approach your analysis. Choose the questions that are most suitable for your source.

- What do you think about the quality of the research? Is it significant?

- Did the author answer the question they set out to? Did the author prove their thesis?

- Did you find contradictions to other things you know?

- What new insight or connections did the author make?

- How does this piece fit within the context of your course, or the larger body of research in the field?

- The structure of an article or book is often dictated by standards of the discipline or a theoretical model. Did the piece meet those standards?

- Did the piece meet the needs of the intended audience?

- Was the material presented in an organized and logical fashion?

- Is the argument cohesive and convincing? Is the reasoning sound? Is there enough evidence?

- Is it easy to read? Is it clear and easy to understand, even if the concepts are sophisticated?

Figure 8. Using synthesis to combine source information and create something new

As this section makes clear, a research project involves more than just gathering data. It calls upon an investigator to use the data in purposeful ways to address research objectives.

How does an investigator track steps in the research process?

Although the research process discussed thus far may seem rather involved, effective preparation can prevent it from becoming overwhelming. A simple tool like the one in Table 2 can help you systematically plan and monitor the progress of a project in order to work confidently toward its conclusion.

Table 2. A tool for tracking steps in the research process

To manage the complexities of research in an orderly manner, use a tool such as this one when undertaking a project.

How does an investigator report research outcomes?

Research outcomes are reported in various types of deliverables, such as infographics and presentations. This chapter concentrates on written reports of research outcomes, focusing in particular on APA-style reports. APA establishes standards for document organization, page design, text construction, and source attribution, as forthcoming sections make clear. This standardization helps bring consistency to APA-style research reports.

Organizing Documents

APA reports are designed for utility so that readers can readily access and use the information contained therein. The body of an APA research report generally follows IMRaD structure, which stands for I ntroduction, M ethod, R esults, and D iscussion. Lab reports similarly follow this structure, as do many journal articles. Using information adapted from Price et al. (2015, pp. 213-221), we can explore the structure of an APA-style research report in further detail.

Constructing the Title Page

An APA-style research report begins with a title page. The title should specifically and concisely communicate the focus and purpose of the investigation, possibly by addressing the study’s research question(s). A clear and informative title, such as “Bilingual, Digital, Audio-Visual Training Modules Improve Technical Knowledge of Feedlot and Dairy Workers” (Reinhardt et al., 2010), immediately alerts readers to a report’s content, helping them determine whether the document is relevant for their needs.

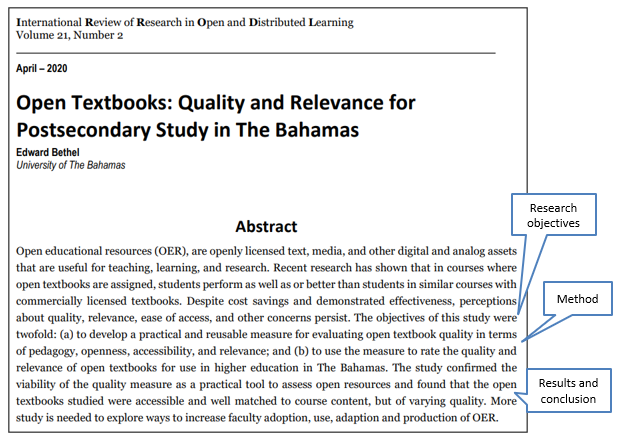

Constructing the Abstract

The abstract is a synopsis of the study, presented on its own separate page, which summarizes the research objectives, the method used to conduct the investigation, the basic results, and the most important conclusions, oftentimes in one concise paragraph of 250 words or fewer. Because an abstract outlines a research report, it is written after the report is complete. Readers use abstracts to determine whether texts are relevant for their needs. Figure 9, adapted from Bethel (2020, p. 61), presents a sample journal article abstract—an abstract is a standard feature of the journal article genre. Notice that the abstract follows IMRaD structure.

Figure 9. A sample abstract from a journal article

An abstract’s strategic location in a journal article—at the top of the article’s first page—efficiently directs readers to useful information.

Although APA style does not require abstracts for student papers, some instructors may assign them regardless. If you are required to compose an abstract for an APA-style report, follow these instructions.

- Start the abstract on its own separate page.

- Double space the page.

- Place the heading Abstract (sans italics) at the top of the page; center the heading and use bold type for it.

- Begin the abstract text on the next line; do not indent the line.

- Insert the keywords list on the line right below the abstract by typing the label Keywords: (italicized), indenting that line, and listing three to five specific keywords that describe the research. (Keywords identify the most important aspects of a paper, again helping readers to discern what texts are relevant for their needs.) or

Figure 10 (Excelsior Online Writing Lab, 2020b, “Abstract”) provides a sample abstract and keywords list for an APA-style student paper.

Figure 10. Abstract and keywords list for an APA-style student paper

If you are required to produce an APA research report for a class, ask your instructor whether an abstract and keywords list is required.

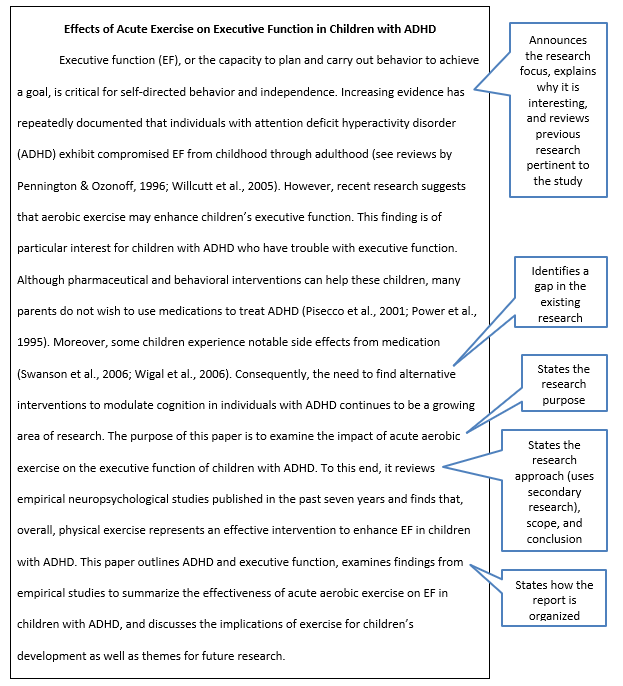

Constructing the Introduction

The introduction section of an APA-style research report sets the context for the rest of the document. It does so by announcing the research focus and explaining why it is interesting, reviewing previous research pertinent to the study, identifying a gap in the previous body of research and establishing how the current study intends to fill the gap, stating the research question(s)/research purpose, and outlining how the rest of the report is organized.

Depending on publication conventions, field of study, or research topic, the literature review segment of an introduction may be incorporated into the introduction proper or presented as its own separate section. A literature review can span several paragraphs or pages, depending on the length and complexity of the research report, and it constitutes a balanced argument for why the research question(s)/research purpose is worth addressing. By the end of the literature review, readers should be convinced that the study’s aims and direction make sense and that the study is a logical next step in extending the existing body of research in the area.

Figure 11, adapted from University of Waterloo (2015, p. 2), provides a sample introduction from an APA-style research report. Integral components of the student’s introduction are highlighted for your reference.

Figure 11. An introduction from a student research report

What is your general impression of the sample introduction? What specific features contribute to its effectiveness/ineffectiveness?

This introduction explains the what , why , how , and so what of the report, giving readers a sense of context for the research study.

Constructing the Method Section

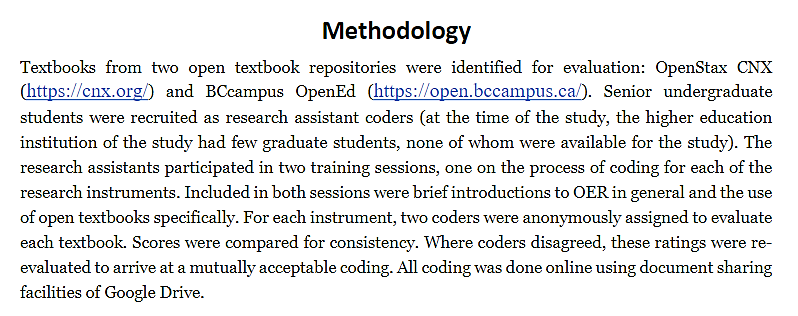

The method section describes how a researcher conducted a study and explains what types of primary and secondary research were used and how. Figure 12, excerpted from the journal article “Open Textbooks: Quality and Relevance for Postsecondary Study in The Bahamas” (Bethel, 2020, p. 66), provides an extract from a method section of a research report. You previously read the abstract for this report in Figure 9.

Figure 12. An extract from the method section of a journal article

As Figure 12 illustrates, the method section should be clear and detailed to facilitate reader understanding; in some cases, the level of detail should allow other researchers to replicate the study by following the procedures outlined.

Constructing the Results Section

The results section presents an investigation’s findings and oftentimes contains illustrations to concisely explain points and illustrate complex concepts. Figure 13, adapted from Excelsior Online Writing Lab (2020e), overviews some of the different types of visuals that might be found in a results section.

Figure 13. An overview of common types of visuals

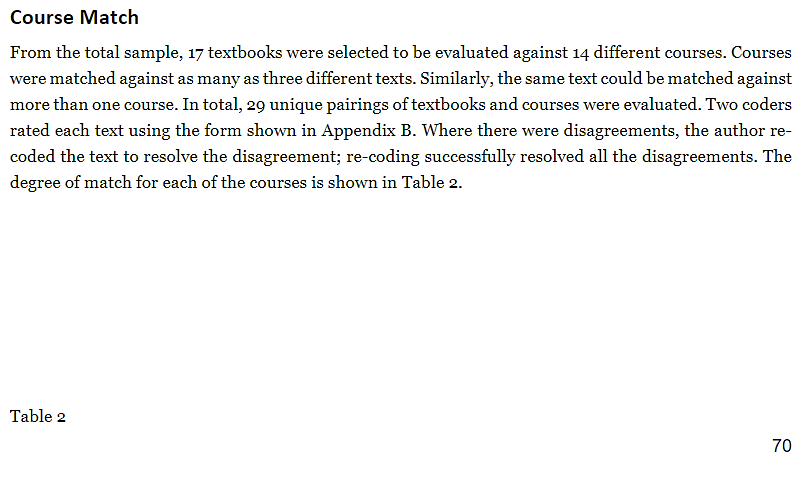

The results section of the Bethel (2020) article on open textbooks contains various types of visuals, as Figure 14, an extract from pages 70 and 71 of the article, illustrates.

Figure 14. An extract from the results section of a journal article

As you review Figure 14, think back to your previous reading about integrating visuals. What change might improve the design of the extract? Provide a rationale for your answer.

The “Designing Documents” and “Integrating Graphic Elements” chapters of this textbook provide further information about the kinds of illustrations that might be found in the results sections of research reports. The APA website ( https://apastyle.apa.org/instructional-aids/handouts-guides ) also provides useful guidance about designing and incorporating visuals.

Constructing the Discussion Section

The discussion section of a research report tells readers what the study’s results mean, draws conclusions based on this interpretation, and may also identify limitations of the research and make suggestions for future investigations. In so doing, the discussion draws connections between the study and existing research discussed in the literature review. Sometimes the results and discussion segments of a report are combined, enabling the writer to discuss both components together; a separate conclusions section may also be included at the end of a report to reinforce the contributions of the research.

Figure 15, adapted from University of Waterloo (2015, p. 7), presents the discussion section of the student research report on children with ADHD that you began reading earlier. What is your general impression of this text? Explain the reason for your response.

Figure 15. Discussion section of a student research report

As Figure 15 illustrates, a discussion section should bring a research report to a logical conclusion.

Constructing the Reference Section

The reference section of a report, which begins on its own separate page, lists the full bibliographic details for sources mentioned in the document. Any source listed in the reference section must have an accompanying in-text citation.

Constructing Appendices

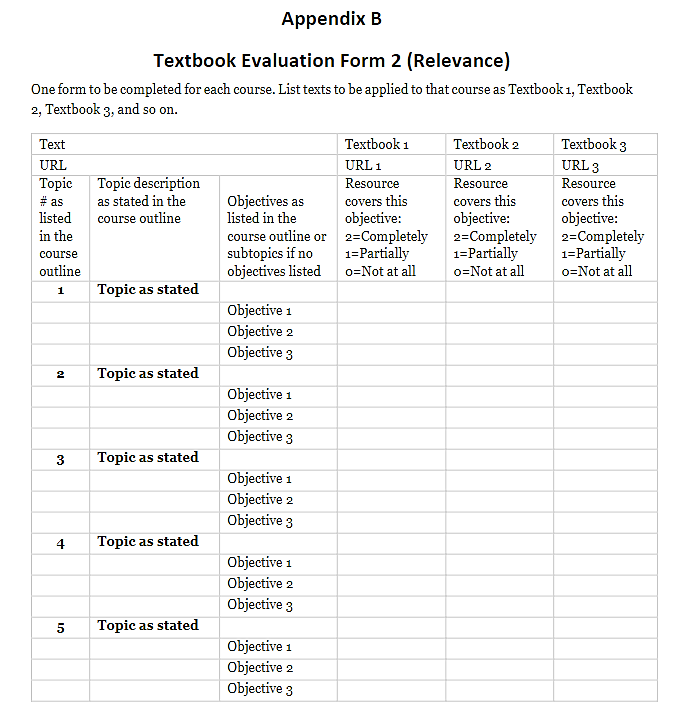

Appendices contain supplementary material that is relevant to the report and may enhance readers’ understanding of its content but that is too lengthy or detailed to be integrated into the report proper. Appendices may not feature in every report; if a report does include them, each appendix is placed on a separate page and is comprised of an individual document or piece of information, such as a map, a list of interview questions, or other material that does not fit neatly into the report. Figure 16, an appendix from the Bethel (2020) article on open textbooks, contains a textbook evaluation instrument presented on its own page (p. 80).

Figure 16. An appendix page from a journal article

If a report contains one appendix, it is labelled Appendix (sans italics). When a report contains more than one appendix, the appendices are lettered in the order in which they are mentioned in the report and labelled with a descriptive tag, as is the appendix in Figure 16.

Designing Pages

APA sets specific formatting standards for student research papers. The template below, adapted from Clackamas Community College Library (2020), Excelsior Online Writing Lab (2020c), and University of Texas Arlington Libraries (2016, “Alphabetizing References”), describes formatting guidelines for APA student papers. The original Clackamas Community College Library (2020) template can be downloaded from http://libguides.clackamas.edu/citing/apa7 .

APA Style Template

Constructing Text

In addition to page design specifications, APA makes recommendations regarding text construction. Conveniently, some of these items overlap with stylistic characteristics common to technical writing. We will explore a number of these items here.

Using Appropriate Verb Tenses in Reports

Writers use different verb tenses in the various sections of reports to describe research stages and outcomes. Figure 17, adapted from Tsai (2017, p. 2), details the circumstances for verb tense use in report sections.

Figure 17. Verb tenses are used for different purposes in research reports

As Figure 17 makes clear, verb tenses point to different conceptual and temporal circumstances in research reports.

Eliminating Contractions (adapted from Schall, 2014c, para. 2)

Contractions—in which an apostrophe is used to contract two words into one by joining parts of them—are considered to be informal, conversational expression. Contractions should not be included in a formal document, such as a report, unless the report writer is quoting something that contains contractions.

Avoiding Commonly Confused Words

Word choice errors may affect the readability of a research report. Here are few sets of commonly confused words that can influence readers’ perceptions of a document.

Amount/Number

- Jagdish was disgusted by the amount of litter on the ground.

- Ali was surprised by the number of mistakes in the report.

Between/Among

- The workshop participants discussed the differences between paraphrasing and summarizing.

- The instructor distributed the tasks among four groups.

- I have less homework this week than I did last week.

- I have fewer pieces of homework this week than I did last week.

Be on the lookout for these commonly confused words when reading and writing research reports.

Avoiding Dangling Modifiers (adapted from Schall, 2014c, paras. 12-13)

Dangling modifiers , descriptive words that seem to dangle off by themselves because they do not accurately describe the words next to them, are a common occurrence in technical writing and are easily overlooked by the writer who assumes the reader will automatically follow the sentence’s meaning. Most often, writers dangle modifiers at the beginnings of sentences. Grammatically, a group of words preceding a sentence’s main subject should directly describe the subject; otherwise, that group of words can become a dangling modifier. The following sentences contain dangling modifiers.

- Using an otoscope, her ears were examined for damage.

- Determining the initial estimates, results from previous tests were used.

Even though these sentences are understandable, grammatically they are unacceptable because the first implies that the ears used the otoscope, while the second implies that the results themselves determined the initial estimates. The words that describe a sentence’s subject must be sensibly related to the subject, and in these two sentences that is not the case. Although here the intended meaning can be discerned with some minimal work, readers often have a hard time sorting out meaning when modifiers are dangled, especially as sentences grow longer. Revision of these sentences to avoid dangling modifiers involves changing the wording slightly and shuffling sentence parts around so the meaning is more logical.

- Her ears were examined for damage with an otoscope.

- Results from previous tests were used to determine the initial estimates.

Because dangling modifiers lead to unintelligible sentences, avoid them.

Referring to Temperature Measurements (adapted from Schall, 2014a, para. 3)

Degree measures of temperature are normally expressed with the ° symbol rather than with the written word, and a space is inserted after the number but not between the symbol and the temperature scale: The sample was heated to 80 °C. Unlike the abbreviations for Fahrenheit and Celsius, the abbreviation for Kelvin (which refers to an absolute scale of temperature) is not preceded by the degree symbol (e.g., 12 K is correct).

Writing about Numbers (adapted from Schall, 2014a, paras. 4-5)

The rules for expressing numbers are as follows.

- The depth to the water at the time of testing was 16.16 feet.

- Express percentages as follows: use the % symbol preceded by a numeral when referring to an exact number, and spell out the word percent (sans italics) when referring to a general size (“a sizable percent of the population”). → Note: this is the APA guideline. General technical writing guidelines recommend using the word percent (sans italics) instead of the symbol (%) in sentences (e.g., 25 percent) and using the symbol (e.g., 25%) in tables to save space.

- For this treatment, the steel was heated 18 different times.

- Fifteen new staff members attended the safety training session.

- Two dramatic changes followed: four samples exploded and thirteen lab technicians resigned.

If you are not sure about when to use numerals versus words, consult the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA, 2020), the definitive source for APA standards. The APA also provides a number of quick reference guides on its website ( https://apastyle.apa.org/instructional-aids/handouts-guides ), including one that covers statistics and numbers.

Using Parentheses (adapted from Schall, 2014b)

In general, parentheses are used to identify material that acts as an aside, but in technical writing the rules for using parentheses can be more nuanced. Parentheses may also be used

- In pulse-jet collectors (Figure 3), bags are supported from a metal cage fastened onto a cell plate at the top of the collector.

- The funnel used for this experiment was 7 in. (17.8 cm) in length.

- The system has three principal components: (1) a cleaning booth, (2) an air reservoir, and (3) an air spray manifold.

- The filtering process involves a 10-mm Dorr-Oliver cyclone (Zefon International).

- Units will be expressed in cubic feet per minute (cfm).

If parentheses enclose a full sentence beginning with a capital letter, then the end punctuation for the sentence falls inside the parentheses.

- Typically, suppliers specify air to cloth ratios of 6:1 or higher. (However, ratios of 4:1 should be used for applications involving silica or feldspathic minerals.)

If the parentheses indicate a citation at the end of a sentence, then the sentence’s end punctuation comes after the parentheses are closed.

- In a study comparing three different building types, respirable dust concentrations were significantly lower in the open-structure building (Hugh et al., 2005).

Finally, if the parentheses appear in the middle of a sentence (as in this example), then any necessary punctuation (such as the comma that appeared just a few words ago) is delayed until the parentheses are closed.

Attributing Sources

In addition to document organization, page design, and text construction specifications, APA also establishes standard conventions for citation and referencing. A writer uses in-text citations to attribute source information within the body of a report and reference list entries to provide the full publication details for the sources cited in text.

Using In-Text Citations

Although other sections of this textbook cover in-text citations in some detail, we will review their construction and conventions for use here to reinforce the importance of source attribution skills to your college and professional careers. Figure 18, a multipage handout adapted from the Robert Gillespie Academic Skills Centre, University of Toronto Mississauga (n.d.a, pp. 5-8), provides an overview of APA in-text citations.

As you review the conventions for APA in-text citations, keep in mind the following punctuation rules, which apply to quotation marks placed at the ends of sentences.

- Place commas and periods inside closing quotation marks.

- Place colons and semicolons outside closing quotation marks.

- Place question marks and exclamation points inside closing quotation marks when they are part of the material being quoted and outside the closing quotation marks when they are not part of the material.

Figure 18. An overview of APA in-text citations

For expanded coverage of APA in-text citations, refer to the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA, 2020) or the APA website

( https://apastyle.apa.org/instructional-aids/handouts-guides ).

The previous figure mentions pairing signal phrases with in-text citations, and you may recall from previous reading that writers use signal phrases to integrate source material into documents in a cohesive way. Signal phrases, in turn, convey various circumstances, as Figure 19, adapted from the Academic Writing Help Centre, Student Academic Success Services, University of Ottawa (2016), points out.

Figure 19. A variety of signal phrases and their circumstances for use

You may use such signal phrases along with in-text citations and accompanying reference list entries to cohesively incorporate source material into a research report.

Constructing References

Reference list entries accompany in-text citations in an APA-style research report. Figure 20, a multipage handout adapted from Reynolds Community College Libraries (2020a), provides an overview of reference formats for various source types.

Figure 20. APA referencing formats for various types of sources

If you require further detail about APA referencing formats, consult the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA, 2020) or the APA website ( https://apastyle.apa.org/instructional-aids/handouts-guides ).

How does an investigator report research in an ethical manner?

Research outcomes must be reported in an ethical manner to be credible and useful. Take into account that ethical considerations affect the development of research reports in numerous ways, as forthcoming paragraphs, which are adapted from Hamlin et al. (2017a, pp. 98-102), explain.

Foregrounding or Downplaying Key Information

A writer’s choices about how to present content in a report can affect readers’ understanding of the relative weight or seriousness of the information. For example, hiding some crucial piece of information in the middle of a long paragraph and burying that paragraph deep in a lengthy document de-emphasizes the information. On the other hand, placing a minor point in a prominent spot—for instance, at the top of a bullet list in a report’s executive summary—tells readers it is crucial.

Omitting Research that Does Not Support a Project Idea

When compiling a report, a writer might discover conflicting data that does not support the research project’s goals. For example, let us imagine the writer’s small company has problems with employee morale. Research shows that bringing in an outside expert, someone who is unfamiliar with the company, has the potential to effect the greatest change in addressing the issue. The writer discovers, however, that hiring such an expert is cost prohibitive. If the writer leaves this information out of the report, its omission encourages the employer to pursue an action that is not feasible.

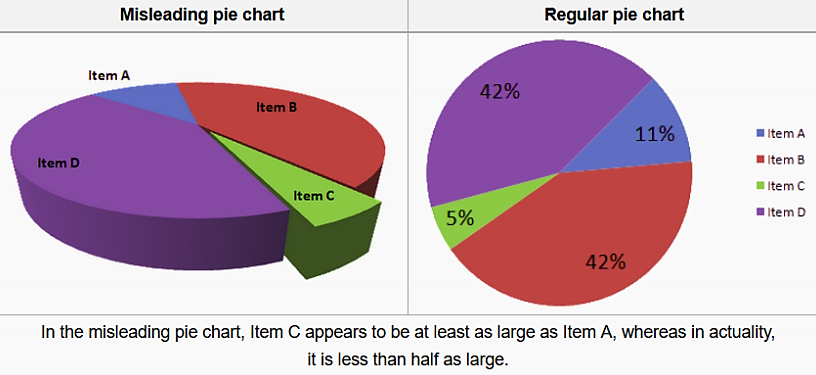

Distorting Visual Information

When writers present information visually in reports, they must be careful not to misrepresent reality. To illustrate this point, consider the pie charts in Figure 21, adapted from Hamlin et al. (2017a, p. 100). The data in each pie chart is identical, but the chart on the left presents information in a misleading way.

Figure 21. Identical data presented two different ways in pie charts

Imagine that these pie charts represent donations received by four candidates running for city council. When looking at the pie chart on the left, the candidate represented by the green slice labeled Item C might think she received more donations than the candidate represented by the blue slice labeled Item A. In fact, if we look at the same data in the differently oriented pie chart on the right, we can see that Item C represents less than half of the donations than those for Item A. Thus, a simple change in perspective can alter the perception of an image.

Relying on Limited Source Information

A thorough research report compiles information from a variety of reliable sources in order to examine a topic from multiple angles. Using a variety of sources helps a report writer avoid the potential bias that can occur when relying on a limited pool of experts. Imagine, for instance, that a writer is composing a report on the real estate market in Central Oregon. The author would be ill-advised to collect data from only one realator’s office. While a particular office might have access to broad data on the real estate market, he/she runs the risk of appearing biased by exclusively selecting material from this one source. Collecting information from multiple brokers would demonstrate thorough and unbiased research.

Documenting Sources in an Inaccurate Manner