An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Yale J Biol Med

- v.93(4); 2020 Sep

Focus: Sex & Reproduction

A case for girl-child education to prevent and curb the impact of emerging infectious diseases epidemics, shadrack frimpong.

a Department of Epidemiology of Microbial Diseases, Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, CT

b Department of Pediatrics, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT

Elijah Paintsil

Not only do epidemics such as HIV/AIDS, Ebola Virus Disease (EVD), and the current Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) cause the loss of millions of lives, but they also cost the global economy billions of dollars. Consequently, there is an urgent need to formulate interventions that will help control their spread and impact when they emerge. The education of young girls and women is one such historical approach. They are usually the vulnerable targets of disease outbreaks – they are most likely to be vehicles for the spread of epidemics due to their assigned traditional roles in resource-limited countries. Based on our work and the work of others on educational interventions, we propose six critical components of a cost-effective and sustainable response to promote girl-child education in resource-limited settings.

Introduction

“Study after study has taught us that there is no tool for development more effective than the education of girls. No other policy is as likely to raise economic productivity, lower infant and maternal mortality, or improve nutrition and promote health – including the prevention of HIV/AIDS.”

Kofi A. Annan, former Secretary-General, United Nations [ 1 ].

As it has been the case of HIV/AIDS and, most recently, the Ebola Virus Disease (EVD), the ongoing Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a stark reminder of a painful reality: epidemics will continue to be the bane of human existence. Consequently, there is an urgent need to critically assess the literature of approaches that have previously mitigated outbreaks and design robust interventions to fight these emerging outbreaks. One such method is the education of young people, especially girls and women. The fact that education is an essential social determinant of health has been well documented [ 2 ]. Early childhood education provides access to higher-income earning potentials, reducing one’s likelihood of getting infected by disease during an epidemic [ 3 ]. The benefits of education in improving health outcomes are high in children and young people, who often depend on their parents and guardians for their livelihoods, including financial resources to access education [ 1 , 3 ]. For instance, a study in Ghana found that the higher the level of education a mother has, the better the child’s chances of survival [ 4 ]. Also, according to UNICEF, young boys and girls who have higher education levels usually have more knowledge about infectious diseases, are less likely to get infected, and tend to adopt behaviors and attitudes that prevent them from being infected [ 1 ]. These health-related benefits of education become even more critical in epidemics such as HIV/AIDS and EVD. Indeed, several studies from around the world have confirmed that HIV infection rates are at least twice as high among adolescents who drop out of primary school than those who stay in school [ 3 ]. The 2014 West African EVD outbreak killed over 11,000 people, left many children orphaned, and exposed to malnutrition, hunger, and preventable deaths [ 5 ]. Deeply affected by the negative repercussions of the lack of quality education, young girls and women in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) usually must contend with power dynamics, traditional roles, and social inequities in communities [ 1 ]. While the global community has made significant headway over the years to leverage access to education as a tool to enhance health outcomes for young girls and women, there still exist gaps in addressing health challenges for this vulnerable population in many LMICs across the globe [ 3 ]. Prior educational interventions have often failed to adequately engage the communities in which they operate or are not financially sustainable without long-term donor support [ 3 ]. Consequently, they crumble during epidemics when donor funding becomes limited, schools close, and teachers and administrators die or become sick. Financially sustainable and community-driven educational interventions for young girls can help to address these challenges and improve health outcomes in LMICs and help curb epidemics.

Impact of Global Educational Efforts on Improving Health Outcomes

Given the limited resources available for tackling the myriads of global health challenges, we must assess prospective educational interventions in the light of rigorous evidence before implementing them. Consequently, we ask: how exactly have global education efforts to improve health performed so far? Evidence from published literature sheds some light. In a study of eight sub-Saharan African countries, Gupta et al . found that females who had eight or more years of schooling were 13% more likely to avoid sex before age 18 compared to their peers with less education [ 6 ]. Also, in Zimbabwe, studies have confirmed that among 15-18-year-old adolescent girls, those who drop out of school are about five times more likely to have HIV than their colleagues who stay in school [ 1 ]. Evidence from surveys in Malawi, Haiti, Uganda, and Zambia further corroborates these findings by showing a secure link between higher education and fewer sexual partners [ 7 ]. The general observation here is that these outcomes are not limited to one country. Indeed, Kirby et al. also found that, in 11 countries, women with some form of schooling were about five times more likely to have used condoms during sexual encounters than uneducated women in similar backgrounds and settings [ 8 ]. These findings underscored global commitments such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) related to HIV/AIDS, Education and Girls; the Dakar Framework for Action related to Girls’ Education; and the current Sustainable Development Goals (SDG #4) to promote inclusive and equitable quality education for all [ 1 ]. Based on these initiatives, many LMICs have made commitments to improving girl-child education. In Ghana, the early 2000s was the era of media campaigns dubbed “send your girl child to school” [ 9 ].

Similarly, many other African governments, with the help of international partners, joined these laudable efforts by providing hundreds of millions of dollars to establish schools for girls and to embark on public education programs in rural communities [ 9 ]. A natural follow-up question would be; how have these educational commitments and interventions affected health outcomes so far? In a recent systematic review, Psaki et al . concluded that, even though investments in schooling may yield positive ripple outcomes for sexual and reproductive health, these effects may not be as pronounced as expected [ 10 ]. In a similar light, Mensch et al . also concluded in their review that, while improvements in women’s educational outcomes such as grade attainment have helped to improve health in several places, the effect may be overestimated [ 11 ]. Regardless, these two studies highlight the critical roles that educational quality and an intervention’s implementation level (community versus national) might play in the synthesis of these outcomes and the conclusions they reported.

The “Ever-Widening Gap” Burden of Epidemics

Although there is a wealth of evidence that education is essential for preventive health in the population, the global community failed to meet the MDG #3 of equal access to education for girls by 2015. Why then are educational efforts still failing to address the health challenges of young girls and women, as we have observed in the HIV/AIDS epidemic and, most recently, the EVD crisis [ 12 ]?

The answer to this question may stem from the challenges of financial sustainability and community engagement that these epidemics expose. This answer corroborates the caveats that Mensch et al . (2019) and Psaki et al . (2019) highlighted. For instance, during the HIV/AIDS and recent EVD outbreaks, many young girls had to drop out of school to provide and care for their families who were sick and dying, consequently increasing their risk of exposure to these lethal viruses [ 13 ]. In these situations, when parents or guardians died, these girls dropped out of school due to default in payment of school fees. In 2003, there were as many as 15 million AIDS orphans [ 1 ], and the 2014 West African EVD outbreak left tens of thousands of orphans in its wake [ 14 ]. Faced with a compounded challenge of affording their nutritional and accommodation needs, they engaged in risky transactional sex as a means of survival [ 14 ].

In some cases, these were non-consensual sexual encounters. Evidence from the Children’s Ebola Recovery Assessment of 617 girls in Sierra Leone found that many young girls who had dropped out of school ended up in Ebola-quarantined households where they became subjects of rape and other forms of sexual assault [ 15 ]. Moreover, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) reported that many young girls in the Democratic Republic of Congo encountered rape and sexual attacks from members of armed groups in communities such as North Kivu and Ituri [ 16 ].

Beyond issues of gender-based violence and school drop-outs, epidemics also weaken the capacity and quality of educational systems. In many countries that are hard-hit by HIV/AIDS and EVD, many teachers died, and the few that survived also had to suspend their teaching roles to cater for their sick and dying family members [ 1 ]. In 2000, at the peak of the HIV/AIDS crisis, about 815 of primary school teachers (45% of trained teachers) in Zambia died from the disease, and close to 8% of the 300 teachers in the Central African Republic also died [ 1 , 17 ]. These teacher shortages are prevalent in rural areas where schools lose staff. Teachers who are affected by disease outbreaks migrate to urban areas for better healthcare for themselves or concerned family members in their care [ 1 ]. In Malawi, the student-teacher ratio in many schools jumped to about 96 to 1 due to AIDS-related illnesses [ 18 ].

Making a Case for Sustainable Education Models

Worldwide, 13 out of the 15 countries where over 30% of school-aged girls are out of school, are in Sub-Saharan Africa [ 19 ]. Yet, this same population of girls remains the most vulnerable during pandemics when schools are closed. In a recent comprehensive report, the Malala Fund forecasted that there is a high likelihood that more than 10 million secondary school-aged girls in LMICs may not return to school after the COVID-19 pandemic [ 20 ]. There is a need for educational interventions for young girls that can withstand the financial shortfalls and the capacity-weakening effects on educational systems that pandemics cause. An organization that implements such interventions is Cocoa360, a nonprofit in rural Western Ghana which transforms communities by using revenues from existing community resources such as cocoa, to finance educational and health outcomes ( Figure 1 ). The details concerning Cocoa360’s model and its impact have already been discussed in a separate publication [ 21 ]. Herein, we draw on published evidence and our own experiences with Cocoa360 to propose six general components ( Figure 2 ) that should be considered in insulating educational models from epidemics:

Cocoa360’s Innovation: “Farm-for-Impact” Model.

General Components of Sustainable Educational Models.

Active community engagement : In a review of interventions that improve girls’ education and gender equality, Unterhalter et al . highlight the effectiveness of programs that focused on shifting gender norms and encouraging inclusion through community involvement [ 22 ]. This finding matches our experience and shared belief that the currency for successful interventions in sub-Saharan Africa is a strong community engagement. Working together with community leaders and members enables external project partners to appreciate cultural nuances and local contexts that need to be considered before, during, and after the implementation process. In many rural communities, community leaders and members coordinate mutual support such as construction labor, contribute resources such as land, and are willing to engage in initiatives that will help financially sustain the intended interventions over the long term. For an education model to be sustainable, it would similarly need to include the inputs and perspectives of the residents and their leaders right from the planning phase, throughout the implementation phase, and post-implementation evaluation efforts as well. Cocoa360, a nonprofit organization in rural Western Ghana, provides an example of how to solicit and successfully engage a community. As a community-based organization, Cocoa360 transforms rural communities by using revenues from existing community resources such as cocoa to finance educational and health outcomes [ 21 ].

From our experience with community engagement, the following are essential ingredients for successful community engagement: (1) Community “knocking” – this is the first step in entering a community. Use this period to share your concept and vision about the project with community elders, usually, the chief, for their acceptance and input; (2) Shared leadership – the community should be involved in the governance of the project right from the start. Cocoa360 collaborated with their partner communities to establish a local decision-making body called the Village Committee (VC) [ 21 ]. This group comprises some of the community’s respected citizens from diverse religious, ethnic, and occupational backgrounds. The VC serves as a link between Cocoa360 and the broader community and ensures that Cocoa360’s operations, including those at its Tarkwa Breman Girls School and Tarkwa Breman Community Clinic, reflect the needs and cultural standards of the community and its members [ 21 ]. This alignment is especially important because many such rural communities still do not prioritize girl-child education due to persisting cultural beliefs; (3) Community education – the community should be reminded continually of the components, their role in the project’s successes, and challenges. Such educational efforts will deepen buy-in and ensure the continued success of the program; (4) Shared successes – the project’s progress should be celebrated with the community in such a way that they know and feel that their contributions matter; and (5) Sustainability plan – the community should be involved in formulating strategies that will ensure project longevity.

Zero tuition costs : Efforts to eliminate tuition costs and make education compulsory in many countries have helped increase educational access for young girls, significantly reduced their vulnerability to child marriages, and many sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV/AIDS. For instance, eliminating tuition fees has been found to reduce child marriages in eight countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, including Ghana, Ethiopia, and Rwanda, despite the challenges encountered in the implementation of this policy [ 23 ]. Additionally, the government of Ghana’s Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education (FCUBE), which aimed to provide tuition-free education for all students in public primary schools, has led to a marked increase in enrollment rates [ 24 ]. In countries such as Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania, eliminating tuition fees has helped to improve school enrollment and student attendance rates, particularly for young girls [ 3 ]. In Uganda, the government’s efforts at easing the burden of tuition led to a 30% increase in girls’ enrollment in school with an almost double effect for the poorest economic fifth of girls [ 3 ]. In a systematic review of 35 studies from 75 reports, Baird et al . also substantiated such findings of the impact of financial incentives on educational outcomes [ 25 ]. They found that both conditional and unconditional cash transfer programs improved the likelihood of school attendance and enrollment compared to programs without cash transfers [ 25 ]. With that said, it is essential to note that zero tuition costs come at a cost to a nation. In response, several governments have devised ways of domestically financing such interventions via taxation and innovative funding models [ 26 ]. Public-private partnerships models for funding primary and secondary education should be encouraged.

Zero non-tuition expenses through community-led revenue generation : As Koski et al . have shown, removing the cost of tuition alone would not be enough to reduce child marriage since other barriers to school enrollment may persist [ 23 ]. In Ghana, despite the FCUBE, there are still gender disparities in educational access. Many young girls are not benefitting from the scheme, and these probably may be due to financial difficulties related to the cost of textbooks, school uniforms, and transportation, which disproportionately plague marginalized households in rural communities [ 24 ]. Stack et al . found in a study in rural Western Ghana that in the face of financial challenges, 44.5% of heads of households, typically males, opted for the male child against 27.7% who chose the female child. Of these, 26.5% stated that it would depend on the specific circumstances, while 1.3% refused to answer [ 27 ]. Thus, the contribution of non-tuition expenses towards school attendance is not trivial. Community and private initiatives could take this burden off parents and heads of households. A thriving community initiative like this is the Cocoa360’s “farm-for-impact” model. Community members assist with work on a community-run cocoa farm in exchange for tuition-free education and subsidized healthcare. The revenues from the farm are applied to finance educational and healthcare services in rural communities in Ghana [ 21 ]. Evidence from meta-analysis and systematic reviews has suggested approaches such as Conditional Cash Transfers and bonuses as effective incentives for increasing girls’ school enrollment in developing countries [ 1 , 28 ]. While successful, these approaches rely on external funding to meet non-tuition expenses, which may not always be available. On the other hand, interventions like Cocoa360’s “farm-for-impact” model seek to consistently keep communities at the forefront of decision making and revenue-generation.

Consequently, they provide a much better independent pathway to self-support the education of their daughters when donor funding becomes limited or ceases [ 21 ]. The process of community-led revenue generation and decision making further imbues a strong sense of communal ownership, which can translate into educational outcomes. For instance, preliminary findings from Cocoa360 show that the school attendance rate is 98%, compared to the national rural attendance rate of about 70% for similar schools under the Ghana government’s Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education (FCUBE) program [ 21 ].

School-based food and nutrition initiatives : Epidemics such as HIV/AIDS and EVD cause many young girls to drop out of school when their parents and guardians are affected or die. Consequently, they end up resorting to transactional sex to obtain support for food and accommodation [ 1 ]. Even for families that remain intact without any deaths during outbreaks, school-based food programs may ease the burden of feeding. This challenge occurs because many families are generally in great need of food during epidemics, as many farmers fall sick and agricultural productivity and output may suffer as a result. Indeed, the World Food Program (WFP) found that in some places, when families were incentivized with food rations for sending their daughters to school, enrollment of girls in school tripled [ 29 ].

Health-centric and school-based curriculum : The instruction of health habits, hygiene, and sanitary conditions and local cultural contexts and their impact on health behaviors should not just be a footnote in educational programs. Instead, they should receive the same attention as math and reading. Right from an early age, schools should provide students with age-appropriate health education that will arm them with the knowledge, skills, and tools to take care of their health and be aware of risky health behaviors. In South Africa, such health-centric and life skills-based curricula have helped to improve young people’s odds of using condoms during sex [ 30 ]. Synthesis of established evidence also shows that school-based sexual health education has the potential to improve condom use among young people in Sub-Saharan Africa and to reduce the prevalence of Sexually Transmitted Infections such as Chlamydia [ 31 ]. Such comprehensive approaches to education can be achieved by ensuring that they are theory-driven, address social determinants like social norms, improve cognitive-behavioral skills, train facilitators like teachers, and include schools, families, and communities [ 32 ].

Safe and protected learning spaces : While schools serve as nurturing grounds for student learning, they can also expose young girls to gender-based violence (GBV) and negatively impact the attainment of educational objectives [ 33 ]. Several studies have reported a high prevalence of GBV, such as sexual harassment, unsolicited advances, touching, groping, and sexual assaults [ 34 , 35 ]. For instance, a Human Rights Watch (HRW) study in South African schools revealed that teachers raped young girls in empty classrooms, lavatories, and dormitories [ 35 ]. In Dodowa, Ghana, similar findings of sexual assault of young girls in schools have also been documented [ 34 ]. Such instances of school-based GBV make schools less attractive places for young girls, who consequently struggle to concentrate on their academics and may, therefore, drop out [ 36 ]. For other deterred girls, they may not enroll at all. Schools pursuing sustainable educational models should strive to make their learning environments safe for young girls by working with community leaders, teachers, students, and related government stakeholders to implement preventive and punitive measures for perpetrators. Evidence from systematic reviews highlights the role of interventions such as life skills training programs and positive peer relationship training approaches to promote self-esteem and to reduce bullying and rape [ 37 ]. Activities such as drama and arts can also help young people evaluate their gender roles and the steps they can take to ensure that their study spaces are safe and conducive to learning [ 1 ]. Successfully achieving this goal would require seeing boys as crucial partners to the solution, rather than external opponents.

Education has proven to be an effective intervention for improving health outcomes and reducing the spread and impact of epidemics. While the global community has made significant progress in leveraging quality girl-child education as a tool to enhance health in LMICs, challenges such as financial bottlenecks continue to impede such efforts, especially during outbreaks. Sustainable educational models that prioritize active community engagement, abolish tuition and non-tuition expenses, incorporate school-based food programs, infuse health-centric and skill-based curriculum, and promote safe learning spaces are much needed. Successful implementation of such efforts would significantly improve educational access and health outcomes for young girls and, consequently, provide long-lasting approaches to fight the spread and impact of epidemics when they emerge.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Priya Bhirgoo for her assistance with helpful comments and edits.

SF is the founder of Cocoa360.

- Girls H. IV/AIDS, and Education [Internet]. UNICEF; 2004. [cited 2020 Mar 3]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/publications/files/Girls_HIV_AIDS_and_Education_(English)_rev.pdf

- Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities . Lancet . 2005. March; 365 ( 9464 ):1099–104. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS01406736(05)711466/fulltext 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- UNAIDS Fight AIDS [Internet]. 2006. May [cited 2020 Mar 3]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/jc1185-educategirls_en_0.pdf

- Quansah E, Ohene LA, Norman L, Mireku MO, Karikari TK. Social Factors Influencing Child Health in Ghana . PLoS One . 2016. January; 11 ( 1 ):e0145401. 10.1371/journal.pone.0145401 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Decroo T, Fitzpatrick G, Amone J. What was the effect of the West African Ebola outbreak on health program performance, and did programs recover? Public Health Action . 2017; 7 ( Suppl 1 ):S1–S2. 10.5588/pha.17.0029 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mahy M, Gupta N. Sexual Initiation Among Adolescent Girls and Boys: Trends and Differentials in Sub-Saharan Africa [Internet] . Archives of Sexual Behavior . Kluwer Academic Publishers-Plenum Publishers; 2003. [cited 2020 Mar 3]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1021841312539 [ PubMed ]

- Gregson S, Nyamukapa CA, Garnett GP, Wambe M, Lewis JJ, Mason PR, et al. HIV infection and reproductive health in teenage women orphaned and made vulnerable by AIDS in Zimbabwe . AIDS Care . 2005. October; 17 ( 7 ):785–94. 10.1080/09540120500258029 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kirby D, Short L, Collins J, Rugg D, Kolbe L, Howard M, et al. School-based programs to reduce sexual risk behaviors: a review of effectiveness . Public Health Rep . 1994. May-Jun; 109 ( 3 ):339–60. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wolf S, Mccoy DC, Godfrey EB. Barriers to school attendance and gender inequality: empirical evidence from a sample of Ghanaian schoolchildren . Res Comp Int Educ . 2016; 11 ( 2 ):178–93. 10.1177/1745499916632424 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Psaki SR, Chuang EK, Melnikas AJ, Wilson DB, Mensch BS. Causal effects of education on sexual and reproductive health in low and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis . SSM Popul Health . 2019. May; 8 :100386. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100386 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mensch BS, Chuang EK, Melnikas AJ, Psaki SR. Evidence for causal links between education and maternal and child health: systematic review . Trop Med Int Health . 2019. May; 24 ( 5 ):504–22. 10.1111/tmi.13218 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Menéndez C, Lucas A, Munguambe K, Langer A. Ebola crisis: the unequal impact on women and children’s health [Internet]. Lancet Glob Health . 2015. March; 3 ( 3 ):e130. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(15)70009-4/fulltext 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70009-4 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ngegba MP, Mansaray DA. Perception of students on the impact of Ebola virus disease. International Journal of Advanced Biological Research [Internet]. 2016. [cited 2020 Mar 9]:119–28. Available from: http://scienceandnature.org/IJABR_Vol6(1)2016/IJABR_V6(1)16-18.pdf

- The impact of Ebola on education in Sierra Leone [Internet]. World Bank Blogs . [cited 2020 Mar 3]. Available from: https://blogs.worldbank.org/education/impact-ebola-education-sierra-leone

- Children RI. Teenage Pregnancies in Ebola-Affected Sierra Leone [Internet]. World Vision . 2015. [cited 2020 Mar 3]. Available from: https://www.worldvision.org/about-us/media-center/children-report-increased-exploitation-teenage-pregnancies-ebola-affected-sierra-leone

- New Ebola outbreak hits women and girls hardest in the Democratic Republic of the Congo [Internet] . United Nations Population Fund . 2018. [cited 2020 Mar 3]. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/news/new-ebola-outbreak-hits-women-and-girls-hardest-democratic-republic-congo

- UNESCO Education for All - The Quality Imperative [Internet] . Global Education Monitoring Report . 2004. [cited 2020 Mar 3]. Available from: https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/report/2005/education-all-quality-imperative

- Africa Bureau Brief United States Agency for International Development Bureau for Africa, Office of Sustainable Development ; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Patel N, Jesse G. African states’ varying progress toward gender equality in education [Internet] . Brookings . Brookings; 2019. [cited 2020 Jun 8]. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2019/06/13/african-states-varying-progress-towardgender-equality-in-education/

- Malala Fund Girls’ Education and COVID-19 ; 2020. April [cited 2020 Jun 8]. Available from: https://downloads.ctfassets.net/0oan5gk9rgbh/6TMYLYAcUpjhQpXLDgmdIa/dd1c2ad08886723cbad85283d479de09/GirlsEducationandCOVID19_MalalaFund_04022020.pdf

- Frimpong S, Russell A, Handy F. Re-Imagining Community Development: The Cocoa360 Model. Research Handbook on Community Development [Internet]. [cited 2020 Mar 3]; Available from: https://www.e-elgar.com/shop/gbp/research-handbook-on-community-development-9781788118460.html

- Unterhalter E, North A, Arnot M, Lloyd C, Moletsane L, Murphy-Graham E, et al. Interventions to enhance girls’ education and gender equality. Education Rigorous Literature Review . Department for International Development; 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- Koski A, Strumpf EC, Kaufman JS, Frank J, Heymann J, Nandi A. The impact of eliminating primary school tuition fees on child marriage in sub-Saharan Africa: A quasi-experimental evaluation of policy changes in 8 countries . PLoS One . 2018. May; 13 ( 5 ):e0197928. 10.1371/journal.pone.0197928 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nudzor HP. Taking education for all goals in sub-Saharan Africa to the task . Manage Educ . 2015; 29 ( 3 ):105–11. 10.1177/0892020615584105 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baird S, Ferreira FH, Özler B, Woolcock M. Conditional, unconditional and everything in between a systematic review of the effects of cash transfer programs on schooling outcomes . J Dev Effect . 2014; 6 ( 1 ):1–43. 10.1080/19439342.2014.890362 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marcum-Mullins W. Conditional Cash Transfers for Education: A Comparative Analysis between the funder and country. International Development, Community, and Environment . IDCE; 2017. p. 102. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stack R. The Effects of an NGO Development Project on the Rural Community of Tarkwa Bremen in Western Ghana [Internet] . ScholarlyCommons . 2017. [cited 2020 Mar 3]. Available from: https://repository.upenn.edu/sire/47/

- Saavedra JE, Garcia S. Impacts of Conditional Cash Transfer Programs on Educational Outcomes in Developing Countries A Meta-analysis . RAND Labor and Population; 2012. pp. 1–63. 10.7249/WR921-1 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- HIV/AIDS & Children Bringing hope to a generation, Food aid to help orphans and other vulnerable children . Rome: World Food Programme; 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Reddy P. Programming for HIV prevention in South African schools . Washington (D.C.): Horizons Research Summary, Population Council; 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sani AS, Abraham C, Denford S, Ball S. School-based sexual health education interventions to prevent STI/HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis . BMC Public Health . 2016. October; 16 ( 1 ):1069. 10.1186/s12889-016-3715-4 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Peters LW, Kok G, Ten Dam GT, Buijs GJ, Paulussen TG. Effective elements of school health promotion across behavioral domains: a systematic review of reviews . BMC Public Health . 2009. June; 9 ( 1 ):182. 10.1186/1471-2458-9-182 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- RTI International RTI [Internet]. Literature Review on the Intersection of Safe Learning Environments and Educational Achievement . U.S. Agency for International Development . 2013. [cited 2020 Jun 8]. Available from: http://www.ungei.org/resources/files/Safe_Learning_and_Achievement_FINAL.pdf

- Afenyadu D, Lakshmi G. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health behavior in Dodowa, Ghana . Washington (D.C.): Centre for Development and Population Activities; 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Scared at School Sexual Violence Against Girls in South African Schools [Internet]. Human Rights Watch . 2009. [cited 2020 Mar 3]. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/report/2001/03/01/scared-school/sexual-violence-against-girls-south-african-schools

- Leach F, Dunne M, Salvi F. A global review of current issues and approaches in policy, programming, and implementation responses to School-Related Gender-Based Violence (SRGBV) for the Education Sector . UNESCO; 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- Xu T, Tomokawa S, Gregorio ER, Jr, Mannava P, Nagai M, Sobel H. School-based interventions to promote adolescent health: A systematic review in low- and middle-income countries of WHO Western Pacific Region . PLoS One . 2020. March; 15 ( 3 ):e0230046. 10.1371/journal.pone.0230046 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- High contrast

- Press Centre

Search UNICEF

Girls' education, gender equality in education benefits every child..

- Girls' education

- Available in:

Investing in girls’ education transforms communities, countries and the entire world. Girls who receive an education are less likely to marry young and more likely to lead healthy, productive lives. They earn higher incomes, participate in the decisions that most affect them, and build better futures for themselves and their families.

Girls’ education strengthens economies and reduces inequality. It contributes to more stable, resilient societies that give all individuals – including boys and men – the opportunity to fulfil their potential.

But education for girls is about more than access to school. It’s also about girls feeling safe in classrooms and supported in the subjects and careers they choose to pursue – including those in which they are often under-represented.

When we invest in girls’ secondary education

- The lifetime earnings of girls dramatically increase

- National growth rates rise

- Child marriage rates decline

- Child mortality rates fall

- Maternal mortality rates fall

- Child stunting drops

Why are girls out of school?

Despite evidence demonstrating how central girls’ education is to development, gender disparities in education persist.

Around the world, 129 million girls are out of school, including 32 million of primary school age, 30 million of lower-secondary school age, and 67 million of upper-secondary school age. In countries affected by conflict, girls are more than twice as likely to be out of school than girls living in non-affected countries.

Worldwide, 129 million girls are out of school.

Only 49 per cent of countries have achieved gender parity in primary education. At the secondary level, the gap widens: 42 per cent of countries have achieved gender parity in lower secondary education, and 24 per cent in upper secondary education.

The reasons are many. Barriers to girls’ education – like poverty, child marriage and gender-based violence – vary among countries and communities. Poor families often favour boys when investing in education.

In some places, schools do not meet the safety, hygiene or sanitation needs of girls. In others, teaching practices are not gender-responsive and result in gender gaps in learning and skills development.

Gender equality in education

Gender-equitable education systems empower girls and boys and promote the development of life skills – like self-management, communication, negotiation and critical thinking – that young people need to succeed. They close skills gaps that perpetuate pay gaps, and build prosperity for entire countries.

Gender-equitable education systems can contribute to reductions in school-related gender-based violence and harmful practices, including child marriage and female genital mutilation .

Gender-equitable education systems help keep both girls and boys in school, building prosperity for entire countries.

An education free of negative gender norms has direct benefits for boys, too. In many countries, norms around masculinity can fuel disengagement from school, child labour, gang violence and recruitment into armed groups. The need or desire to earn an income also causes boys to drop out of secondary school, as many of them believe the curriculum is not relevant to work opportunities.

UNICEF’s work to promote girls’ education

UNICEF works with communities, Governments and partners to remove barriers to girls’ education and promote gender equality in education – even in the most challenging settings.

Because investing in girls’ secondary education is one of the most transformative development strategies, we prioritize efforts that enable all girls to complete secondary education and develop the knowledge and skills they need for life and work.

This will only be achieved when the most disadvantaged girls are supported to enter and complete pre-primary and primary education. Our work:

- Tackles discriminatory gender norms and harmful practices that deny girls access to school and quality learning.

- Supports Governments to ensure that budgets are gender-responsive and that national education plans and policies prioritize gender equality.

- Helps schools and Governments use assessment data to eliminate gender gaps in learning.

- Promotes social protection measures, including cash transfers, to improve girls’ transition to and retention in secondary school.

- Focuses teacher training and professional development on gender-responsive pedagogies.

- Removes gender stereotypes from learning materials.

- Addresses other obstacles, like distance-related barriers to education, re-entry policies for young mothers, and menstrual hygiene management in schools.

More from UNICEF

1 in 3 adolescent girls from the poorest households has never been to school

Let’s shape tech to be transformative

Gender-responsive digital pedagogies: A guide for educators

Stories of suffering and hope: Afghanistan and Pakistan

Catherine Russell reflects on her first field visit as UNICEF's Executive Director

Where are the girls and why it matters as schools reopen?

School closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic risk reversing the massive gains to girls’ education

Advancing Girls' Education and Gender Equality through Digital Learning

This brief note highlights how UNICEF will advance inclusive and transformative digital technology to enhance girls’ learning and skills development for work and life.

Reimagining Girls' Education: Solutions to Keep Girls Learning in Emergencies

This resource presents an empirical overview of what works to support learning outcomes for girls in emergencies.

e-Toolkit on Gender Equality in Education

This course aims to strengthen the capacity of UNICEF's education staff globally in gender equality applied to education programming.

Fixing the Broken Promise of Education for All

This report draws on national studies to examine why millions of children continue to be denied the fundamental right to primary education.

GirlForce: Skills, Education and Training for Girls Now

This report discusses persistent barriers girls face in the transition from education to the workforce, and how gender gaps in employment outcomes persist despite girls’ gains in education.

UNICEF Gender Action Plan (2022-2025)

This plan specifies how UNICEF will promote gender equality across the organization’s work, in alignment with the UNICEF Strategic Plan.

Global Partnership for Education

This partnership site provides data and programming results for the only global fund solely dedicated to education in developing countries.

United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative

UNGEI promotes girls’ education and gender equality through policy advocacy and support to Governments and other development actors.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Browse content in A - General Economics and Teaching

- Browse content in A1 - General Economics

- A11 - Role of Economics; Role of Economists; Market for Economists

- Browse content in A2 - Economic Education and Teaching of Economics

- A22 - Undergraduate

- Browse content in B - History of Economic Thought, Methodology, and Heterodox Approaches

- B4 - Economic Methodology

- Browse content in B5 - Current Heterodox Approaches

- B54 - Feminist Economics

- Browse content in C - Mathematical and Quantitative Methods

- Browse content in C1 - Econometric and Statistical Methods and Methodology: General

- C11 - Bayesian Analysis: General

- C12 - Hypothesis Testing: General

- C14 - Semiparametric and Nonparametric Methods: General

- C15 - Statistical Simulation Methods: General

- C18 - Methodological Issues: General

- Browse content in C2 - Single Equation Models; Single Variables

- C20 - General

- C21 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions

- C23 - Panel Data Models; Spatio-temporal Models

- C26 - Instrumental Variables (IV) Estimation

- Browse content in C3 - Multiple or Simultaneous Equation Models; Multiple Variables

- C31 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions; Social Interaction Models

- C32 - Time-Series Models; Dynamic Quantile Regressions; Dynamic Treatment Effect Models; Diffusion Processes; State Space Models

- C33 - Panel Data Models; Spatio-temporal Models

- C36 - Instrumental Variables (IV) Estimation

- Browse content in C4 - Econometric and Statistical Methods: Special Topics

- C41 - Duration Analysis; Optimal Timing Strategies

- C42 - Survey Methods

- C43 - Index Numbers and Aggregation

- Browse content in C5 - Econometric Modeling

- C50 - General

- C51 - Model Construction and Estimation

- C52 - Model Evaluation, Validation, and Selection

- C53 - Forecasting and Prediction Methods; Simulation Methods

- C58 - Financial Econometrics

- Browse content in C6 - Mathematical Methods; Programming Models; Mathematical and Simulation Modeling

- C68 - Computable General Equilibrium Models

- Browse content in C7 - Game Theory and Bargaining Theory

- C72 - Noncooperative Games

- Browse content in C8 - Data Collection and Data Estimation Methodology; Computer Programs

- C80 - General

- C81 - Methodology for Collecting, Estimating, and Organizing Microeconomic Data; Data Access

- C82 - Methodology for Collecting, Estimating, and Organizing Macroeconomic Data; Data Access

- C83 - Survey Methods; Sampling Methods

- Browse content in C9 - Design of Experiments

- C90 - General

- C91 - Laboratory, Individual Behavior

- C93 - Field Experiments

- Browse content in D - Microeconomics

- Browse content in D0 - General

- D02 - Institutions: Design, Formation, Operations, and Impact

- D03 - Behavioral Microeconomics: Underlying Principles

- D04 - Microeconomic Policy: Formulation; Implementation, and Evaluation

- Browse content in D1 - Household Behavior and Family Economics

- D10 - General

- D11 - Consumer Economics: Theory

- D12 - Consumer Economics: Empirical Analysis

- D13 - Household Production and Intrahousehold Allocation

- D14 - Household Saving; Personal Finance

- D19 - Other

- Browse content in D2 - Production and Organizations

- D21 - Firm Behavior: Theory

- D22 - Firm Behavior: Empirical Analysis

- D23 - Organizational Behavior; Transaction Costs; Property Rights

- D24 - Production; Cost; Capital; Capital, Total Factor, and Multifactor Productivity; Capacity

- Browse content in D3 - Distribution

- D30 - General

- D31 - Personal Income, Wealth, and Their Distributions

- D33 - Factor Income Distribution

- D39 - Other

- Browse content in D4 - Market Structure, Pricing, and Design

- D40 - General

- Browse content in D5 - General Equilibrium and Disequilibrium

- D50 - General

- D52 - Incomplete Markets

- D57 - Input-Output Tables and Analysis

- Browse content in D6 - Welfare Economics

- D60 - General

- D61 - Allocative Efficiency; Cost-Benefit Analysis

- D62 - Externalities

- D63 - Equity, Justice, Inequality, and Other Normative Criteria and Measurement

- D64 - Altruism; Philanthropy

- Browse content in D7 - Analysis of Collective Decision-Making

- D70 - General

- D71 - Social Choice; Clubs; Committees; Associations

- D72 - Political Processes: Rent-seeking, Lobbying, Elections, Legislatures, and Voting Behavior

- D73 - Bureaucracy; Administrative Processes in Public Organizations; Corruption

- D74 - Conflict; Conflict Resolution; Alliances; Revolutions

- Browse content in D8 - Information, Knowledge, and Uncertainty

- D80 - General

- D81 - Criteria for Decision-Making under Risk and Uncertainty

- D82 - Asymmetric and Private Information; Mechanism Design

- D83 - Search; Learning; Information and Knowledge; Communication; Belief; Unawareness

- D84 - Expectations; Speculations

- D85 - Network Formation and Analysis: Theory

- Browse content in D9 - Micro-Based Behavioral Economics

- D90 - General

- D91 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making

- D92 - Intertemporal Firm Choice, Investment, Capacity, and Financing

- Browse content in E - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Browse content in E0 - General

- E01 - Measurement and Data on National Income and Product Accounts and Wealth; Environmental Accounts

- Browse content in E1 - General Aggregative Models

- E10 - General

- E17 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E2 - Consumption, Saving, Production, Investment, Labor Markets, and Informal Economy

- E20 - General

- E21 - Consumption; Saving; Wealth

- E22 - Investment; Capital; Intangible Capital; Capacity

- E23 - Production

- E24 - Employment; Unemployment; Wages; Intergenerational Income Distribution; Aggregate Human Capital; Aggregate Labor Productivity

- E25 - Aggregate Factor Income Distribution

- E26 - Informal Economy; Underground Economy

- Browse content in E3 - Prices, Business Fluctuations, and Cycles

- E31 - Price Level; Inflation; Deflation

- E32 - Business Fluctuations; Cycles

- Browse content in E4 - Money and Interest Rates

- E43 - Interest Rates: Determination, Term Structure, and Effects

- E44 - Financial Markets and the Macroeconomy

- Browse content in E5 - Monetary Policy, Central Banking, and the Supply of Money and Credit

- E50 - General

- Browse content in E6 - Macroeconomic Policy, Macroeconomic Aspects of Public Finance, and General Outlook

- E61 - Policy Objectives; Policy Designs and Consistency; Policy Coordination

- E62 - Fiscal Policy

- Browse content in F - International Economics

- Browse content in F0 - General

- F02 - International Economic Order and Integration

- Browse content in F1 - Trade

- F10 - General

- F11 - Neoclassical Models of Trade

- F12 - Models of Trade with Imperfect Competition and Scale Economies; Fragmentation

- F13 - Trade Policy; International Trade Organizations

- F14 - Empirical Studies of Trade

- F15 - Economic Integration

- F16 - Trade and Labor Market Interactions

- F17 - Trade Forecasting and Simulation

- F18 - Trade and Environment

- Browse content in F2 - International Factor Movements and International Business

- F21 - International Investment; Long-Term Capital Movements

- F22 - International Migration

- F23 - Multinational Firms; International Business

- F24 - Remittances

- Browse content in F3 - International Finance

- F31 - Foreign Exchange

- F32 - Current Account Adjustment; Short-Term Capital Movements

- F33 - International Monetary Arrangements and Institutions

- F34 - International Lending and Debt Problems

- F35 - Foreign Aid

- F36 - Financial Aspects of Economic Integration

- Browse content in F4 - Macroeconomic Aspects of International Trade and Finance

- F40 - General

- F41 - Open Economy Macroeconomics

- F42 - International Policy Coordination and Transmission

- F43 - Economic Growth of Open Economies

- F47 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in F5 - International Relations, National Security, and International Political Economy

- F50 - General

- F51 - International Conflicts; Negotiations; Sanctions

- F53 - International Agreements and Observance; International Organizations

- F55 - International Institutional Arrangements

- Browse content in F6 - Economic Impacts of Globalization

- F61 - Microeconomic Impacts

- F62 - Macroeconomic Impacts

- F63 - Economic Development

- F66 - Labor

- Browse content in G - Financial Economics

- Browse content in G0 - General

- G01 - Financial Crises

- G02 - Behavioral Finance: Underlying Principles

- Browse content in G1 - General Financial Markets

- G10 - General

- G11 - Portfolio Choice; Investment Decisions

- G12 - Asset Pricing; Trading volume; Bond Interest Rates

- G14 - Information and Market Efficiency; Event Studies; Insider Trading

- G15 - International Financial Markets

- G18 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G2 - Financial Institutions and Services

- G20 - General

- G21 - Banks; Depository Institutions; Micro Finance Institutions; Mortgages

- G22 - Insurance; Insurance Companies; Actuarial Studies

- G23 - Non-bank Financial Institutions; Financial Instruments; Institutional Investors

- G28 - Government Policy and Regulation

- G29 - Other

- Browse content in G3 - Corporate Finance and Governance

- G30 - General

- G31 - Capital Budgeting; Fixed Investment and Inventory Studies; Capacity

- G32 - Financing Policy; Financial Risk and Risk Management; Capital and Ownership Structure; Value of Firms; Goodwill

- G33 - Bankruptcy; Liquidation

- G34 - Mergers; Acquisitions; Restructuring; Corporate Governance

- G38 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G5 - Household Finance

- G50 - General

- G51 - Household Saving, Borrowing, Debt, and Wealth

- Browse content in H - Public Economics

- Browse content in H0 - General

- H00 - General

- Browse content in H1 - Structure and Scope of Government

- H10 - General

- H11 - Structure, Scope, and Performance of Government

- Browse content in H2 - Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H21 - Efficiency; Optimal Taxation

- H22 - Incidence

- H23 - Externalities; Redistributive Effects; Environmental Taxes and Subsidies

- H24 - Personal Income and Other Nonbusiness Taxes and Subsidies; includes inheritance and gift taxes

- H25 - Business Taxes and Subsidies

- H26 - Tax Evasion and Avoidance

- Browse content in H3 - Fiscal Policies and Behavior of Economic Agents

- H31 - Household

- Browse content in H4 - Publicly Provided Goods

- H40 - General

- H41 - Public Goods

- H42 - Publicly Provided Private Goods

- H43 - Project Evaluation; Social Discount Rate

- H44 - Publicly Provided Goods: Mixed Markets

- Browse content in H5 - National Government Expenditures and Related Policies

- H50 - General

- H51 - Government Expenditures and Health

- H52 - Government Expenditures and Education

- H53 - Government Expenditures and Welfare Programs

- H54 - Infrastructures; Other Public Investment and Capital Stock

- H55 - Social Security and Public Pensions

- H56 - National Security and War

- H57 - Procurement

- Browse content in H6 - National Budget, Deficit, and Debt

- H60 - General

- H63 - Debt; Debt Management; Sovereign Debt

- Browse content in H7 - State and Local Government; Intergovernmental Relations

- H70 - General

- H72 - State and Local Budget and Expenditures

- H73 - Interjurisdictional Differentials and Their Effects

- H75 - State and Local Government: Health; Education; Welfare; Public Pensions

- H77 - Intergovernmental Relations; Federalism; Secession

- Browse content in H8 - Miscellaneous Issues

- H81 - Governmental Loans; Loan Guarantees; Credits; Grants; Bailouts

- H83 - Public Administration; Public Sector Accounting and Audits

- H87 - International Fiscal Issues; International Public Goods

- Browse content in I - Health, Education, and Welfare

- Browse content in I0 - General

- I00 - General

- Browse content in I1 - Health

- I10 - General

- I11 - Analysis of Health Care Markets

- I12 - Health Behavior

- I13 - Health Insurance, Public and Private

- I14 - Health and Inequality

- I15 - Health and Economic Development

- I18 - Government Policy; Regulation; Public Health

- Browse content in I2 - Education and Research Institutions

- I20 - General

- I21 - Analysis of Education

- I22 - Educational Finance; Financial Aid

- I23 - Higher Education; Research Institutions

- I24 - Education and Inequality

- I25 - Education and Economic Development

- I26 - Returns to Education

- I28 - Government Policy

- I29 - Other

- Browse content in I3 - Welfare, Well-Being, and Poverty

- I30 - General

- I31 - General Welfare

- I32 - Measurement and Analysis of Poverty

- I38 - Government Policy; Provision and Effects of Welfare Programs

- Browse content in J - Labor and Demographic Economics

- Browse content in J0 - General

- J08 - Labor Economics Policies

- Browse content in J1 - Demographic Economics

- J10 - General

- J11 - Demographic Trends, Macroeconomic Effects, and Forecasts

- J12 - Marriage; Marital Dissolution; Family Structure; Domestic Abuse

- J13 - Fertility; Family Planning; Child Care; Children; Youth

- J14 - Economics of the Elderly; Economics of the Handicapped; Non-Labor Market Discrimination

- J15 - Economics of Minorities, Races, Indigenous Peoples, and Immigrants; Non-labor Discrimination

- J16 - Economics of Gender; Non-labor Discrimination

- J17 - Value of Life; Forgone Income

- J18 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J2 - Demand and Supply of Labor

- J20 - General

- J21 - Labor Force and Employment, Size, and Structure

- J22 - Time Allocation and Labor Supply

- J23 - Labor Demand

- J24 - Human Capital; Skills; Occupational Choice; Labor Productivity

- J26 - Retirement; Retirement Policies

- J28 - Safety; Job Satisfaction; Related Public Policy

- Browse content in J3 - Wages, Compensation, and Labor Costs

- J30 - General

- J31 - Wage Level and Structure; Wage Differentials

- J32 - Nonwage Labor Costs and Benefits; Retirement Plans; Private Pensions

- J38 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J4 - Particular Labor Markets

- J42 - Monopsony; Segmented Labor Markets

- J43 - Agricultural Labor Markets

- J44 - Professional Labor Markets; Occupational Licensing

- J45 - Public Sector Labor Markets

- J46 - Informal Labor Markets

- Browse content in J6 - Mobility, Unemployment, Vacancies, and Immigrant Workers

- J60 - General

- J61 - Geographic Labor Mobility; Immigrant Workers

- J63 - Turnover; Vacancies; Layoffs

- J64 - Unemployment: Models, Duration, Incidence, and Job Search

- J65 - Unemployment Insurance; Severance Pay; Plant Closings

- J68 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J8 - Labor Standards: National and International

- J81 - Working Conditions

- J88 - Public Policy

- Browse content in K - Law and Economics

- K0 - General

- Browse content in K1 - Basic Areas of Law

- K10 - General

- K11 - Property Law

- K14 - Criminal Law

- K2 - Regulation and Business Law

- Browse content in K3 - Other Substantive Areas of Law

- K31 - Labor Law

- K36 - Family and Personal Law

- Browse content in K4 - Legal Procedure, the Legal System, and Illegal Behavior

- K42 - Illegal Behavior and the Enforcement of Law

- Browse content in L - Industrial Organization

- Browse content in L0 - General

- L00 - General

- Browse content in L1 - Market Structure, Firm Strategy, and Market Performance

- L10 - General

- L11 - Production, Pricing, and Market Structure; Size Distribution of Firms

- L14 - Transactional Relationships; Contracts and Reputation; Networks

- L15 - Information and Product Quality; Standardization and Compatibility

- L16 - Industrial Organization and Macroeconomics: Industrial Structure and Structural Change; Industrial Price Indices

- Browse content in L2 - Firm Objectives, Organization, and Behavior

- L20 - General

- L21 - Business Objectives of the Firm

- L22 - Firm Organization and Market Structure

- L25 - Firm Performance: Size, Diversification, and Scope

- L26 - Entrepreneurship

- Browse content in L3 - Nonprofit Organizations and Public Enterprise

- L31 - Nonprofit Institutions; NGOs; Social Entrepreneurship

- L33 - Comparison of Public and Private Enterprises and Nonprofit Institutions; Privatization; Contracting Out

- Browse content in L4 - Antitrust Issues and Policies

- L43 - Legal Monopolies and Regulation or Deregulation

- Browse content in L5 - Regulation and Industrial Policy

- L51 - Economics of Regulation

- L52 - Industrial Policy; Sectoral Planning Methods

- Browse content in L6 - Industry Studies: Manufacturing

- L60 - General

- L66 - Food; Beverages; Cosmetics; Tobacco; Wine and Spirits

- Browse content in L7 - Industry Studies: Primary Products and Construction

- L70 - General

- Browse content in L8 - Industry Studies: Services

- L80 - General

- L86 - Information and Internet Services; Computer Software

- Browse content in L9 - Industry Studies: Transportation and Utilities

- L90 - General

- L91 - Transportation: General

- L92 - Railroads and Other Surface Transportation

- L94 - Electric Utilities

- L95 - Gas Utilities; Pipelines; Water Utilities

- L96 - Telecommunications

- L97 - Utilities: General

- Browse content in M - Business Administration and Business Economics; Marketing; Accounting; Personnel Economics

- Browse content in M1 - Business Administration

- M13 - New Firms; Startups

- Browse content in M5 - Personnel Economics

- M50 - General

- M51 - Firm Employment Decisions; Promotions

- M53 - Training

- Browse content in N - Economic History

- Browse content in N0 - General

- N00 - General

- Browse content in N1 - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics; Industrial Structure; Growth; Fluctuations

- N17 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N2 - Financial Markets and Institutions

- N20 - General, International, or Comparative

- N22 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- Browse content in N3 - Labor and Consumers, Demography, Education, Health, Welfare, Income, Wealth, Religion, and Philanthropy

- N35 - Asia including Middle East

- N37 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N4 - Government, War, Law, International Relations, and Regulation

- N47 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N5 - Agriculture, Natural Resources, Environment, and Extractive Industries

- N55 - Asia including Middle East

- N56 - Latin America; Caribbean

- N57 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N7 - Transport, Trade, Energy, Technology, and Other Services

- N77 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N9 - Regional and Urban History

- N97 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in O - Economic Development, Innovation, Technological Change, and Growth

- Browse content in O1 - Economic Development

- O10 - General

- O11 - Macroeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O12 - Microeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O13 - Agriculture; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Other Primary Products

- O14 - Industrialization; Manufacturing and Service Industries; Choice of Technology

- O15 - Human Resources; Human Development; Income Distribution; Migration

- O16 - Financial Markets; Saving and Capital Investment; Corporate Finance and Governance

- O17 - Formal and Informal Sectors; Shadow Economy; Institutional Arrangements

- O18 - Urban, Rural, Regional, and Transportation Analysis; Housing; Infrastructure

- O19 - International Linkages to Development; Role of International Organizations

- Browse content in O2 - Development Planning and Policy

- O20 - General

- O21 - Planning Models; Planning Policy

- O22 - Project Analysis

- O23 - Fiscal and Monetary Policy in Development

- O24 - Trade Policy; Factor Movement Policy; Foreign Exchange Policy

- O25 - Industrial Policy

- Browse content in O3 - Innovation; Research and Development; Technological Change; Intellectual Property Rights

- O30 - General

- O31 - Innovation and Invention: Processes and Incentives

- O33 - Technological Change: Choices and Consequences; Diffusion Processes

- O38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in O4 - Economic Growth and Aggregate Productivity

- O40 - General

- O41 - One, Two, and Multisector Growth Models

- O43 - Institutions and Growth

- O47 - Empirical Studies of Economic Growth; Aggregate Productivity; Cross-Country Output Convergence

- Browse content in O5 - Economywide Country Studies

- O50 - General

- O52 - Europe

- O53 - Asia including Middle East

- O54 - Latin America; Caribbean

- O55 - Africa

- O57 - Comparative Studies of Countries

- Browse content in P - Economic Systems

- Browse content in P1 - Capitalist Systems

- P16 - Political Economy

- P18 - Energy: Environment

- Browse content in P2 - Socialist Systems and Transitional Economies

- P20 - General

- P21 - Planning, Coordination, and Reform

- P23 - Factor and Product Markets; Industry Studies; Population

- Browse content in P3 - Socialist Institutions and Their Transitions

- P31 - Socialist Enterprises and Their Transitions

- P36 - Consumer Economics; Health; Education and Training; Welfare, Income, Wealth, and Poverty

- P37 - Legal Institutions; Illegal Behavior

- Browse content in P4 - Other Economic Systems

- P45 - International Trade, Finance, Investment, and Aid

- P46 - Consumer Economics; Health; Education and Training; Welfare, Income, Wealth, and Poverty

- P48 - Political Economy; Legal Institutions; Property Rights; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Regional Studies

- Browse content in P5 - Comparative Economic Systems

- P51 - Comparative Analysis of Economic Systems

- P52 - Comparative Studies of Particular Economies

- Browse content in Q - Agricultural and Natural Resource Economics; Environmental and Ecological Economics

- Browse content in Q0 - General

- Q01 - Sustainable Development

- Q02 - Commodity Markets

- Browse content in Q1 - Agriculture

- Q10 - General

- Q11 - Aggregate Supply and Demand Analysis; Prices

- Q12 - Micro Analysis of Farm Firms, Farm Households, and Farm Input Markets

- Q13 - Agricultural Markets and Marketing; Cooperatives; Agribusiness

- Q14 - Agricultural Finance

- Q15 - Land Ownership and Tenure; Land Reform; Land Use; Irrigation; Agriculture and Environment

- Q16 - R&D; Agricultural Technology; Biofuels; Agricultural Extension Services

- Q17 - Agriculture in International Trade

- Q18 - Agricultural Policy; Food Policy

- Q19 - Other

- Browse content in Q2 - Renewable Resources and Conservation

- Q20 - General

- Q22 - Fishery; Aquaculture

- Q25 - Water

- Browse content in Q3 - Nonrenewable Resources and Conservation

- Q32 - Exhaustible Resources and Economic Development

- Q34 - Natural Resources and Domestic and International Conflicts

- Browse content in Q4 - Energy

- Q41 - Demand and Supply; Prices

- Q42 - Alternative Energy Sources

- Browse content in Q5 - Environmental Economics

- Q50 - General

- Q51 - Valuation of Environmental Effects

- Q53 - Air Pollution; Water Pollution; Noise; Hazardous Waste; Solid Waste; Recycling

- Q54 - Climate; Natural Disasters; Global Warming

- Q56 - Environment and Development; Environment and Trade; Sustainability; Environmental Accounts and Accounting; Environmental Equity; Population Growth

- Q57 - Ecological Economics: Ecosystem Services; Biodiversity Conservation; Bioeconomics; Industrial Ecology

- Q58 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R - Urban, Rural, Regional, Real Estate, and Transportation Economics

- Browse content in R0 - General

- R00 - General

- Browse content in R1 - General Regional Economics

- R10 - General

- R11 - Regional Economic Activity: Growth, Development, Environmental Issues, and Changes

- R12 - Size and Spatial Distributions of Regional Economic Activity

- R13 - General Equilibrium and Welfare Economic Analysis of Regional Economies

- R14 - Land Use Patterns

- Browse content in R2 - Household Analysis

- R20 - General

- R22 - Other Demand

- R23 - Regional Migration; Regional Labor Markets; Population; Neighborhood Characteristics

- R28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R3 - Real Estate Markets, Spatial Production Analysis, and Firm Location

- R31 - Housing Supply and Markets

- R32 - Other Spatial Production and Pricing Analysis

- Browse content in R4 - Transportation Economics

- R41 - Transportation: Demand, Supply, and Congestion; Travel Time; Safety and Accidents; Transportation Noise

- Browse content in R5 - Regional Government Analysis

- R51 - Finance in Urban and Rural Economies

- R53 - Public Facility Location Analysis; Public Investment and Capital Stock

- Browse content in Y - Miscellaneous Categories

- Browse content in Y1 - Data: Tables and Charts

- Y10 - Data: Tables and Charts

- Browse content in Z - Other Special Topics

- Browse content in Z1 - Cultural Economics; Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology

- Z10 - General

- Z12 - Religion

- Z13 - Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology; Social and Economic Stratification

- Z18 - Public Policy

- About The World Bank Economic Review

- About the World Bank

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction, 4. discussion, 6. conclusion.

- < Previous

What We Learn about Girls’ Education from Interventions That Do Not Focus on Girls

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

David K Evans, Fei Yuan, What We Learn about Girls’ Education from Interventions That Do Not Focus on Girls, The World Bank Economic Review , Volume 36, Issue 1, February 2022, Pages 244–267, https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhab007

- Permissions Icon Permissions

What is the best way to improve access and learning outcomes for girls? This review brings together evidence from 267 educational interventions in 54 low- and middle-income countries – regardless of whether the interventions specifically target girls – and identifies their impacts on girls. To improve access and learning, general interventions deliver average gains for girls that are comparable to girl-targeted interventions. General interventions have similar impacts for girls as for boys. Taken together, these findings suggest that many educational gains for girls may be achieved through nontargeted programs. Many of the most effective interventions to improve access for girls relax household-level constraints (such as cash transfer programs), and many of the most effective interventions to improve learning for girls involve improving the pedagogy of teachers. Girl-targeted interventions may make the most sense when addressing constraints that are unique to, or most pronounced for, girls.

Investing in girls’ education has been called “the world's best investment” ( Sperling and Winthrop 2015 ). But how can policymakers do so most effectively? Evidence on what works to improve the quality of education is accumulating at an unprecedented rate ( World Bank 2018b ). 1 In recent years, hundreds of impact evaluations in low- and middle-income countries have demonstrated the effectiveness – or lack thereof – of a range of interventions at improving education outcomes, for girls and boys ( Evans and Popova 2016 ; J-PAL 2017 ). Reviews that examine the most effective ways to boost girls’ education tend to focus on interventions that target girls – for example, building girls’ latrines at schools or providing scholarships for girls – potentially missing large educational benefits for girls from interventions that are not gender-specific ( Unterhalter et al. 2014 ; Sperling and Winthrop 2015 ; Haberland, McCarthy, and Brady 2018 ). 2

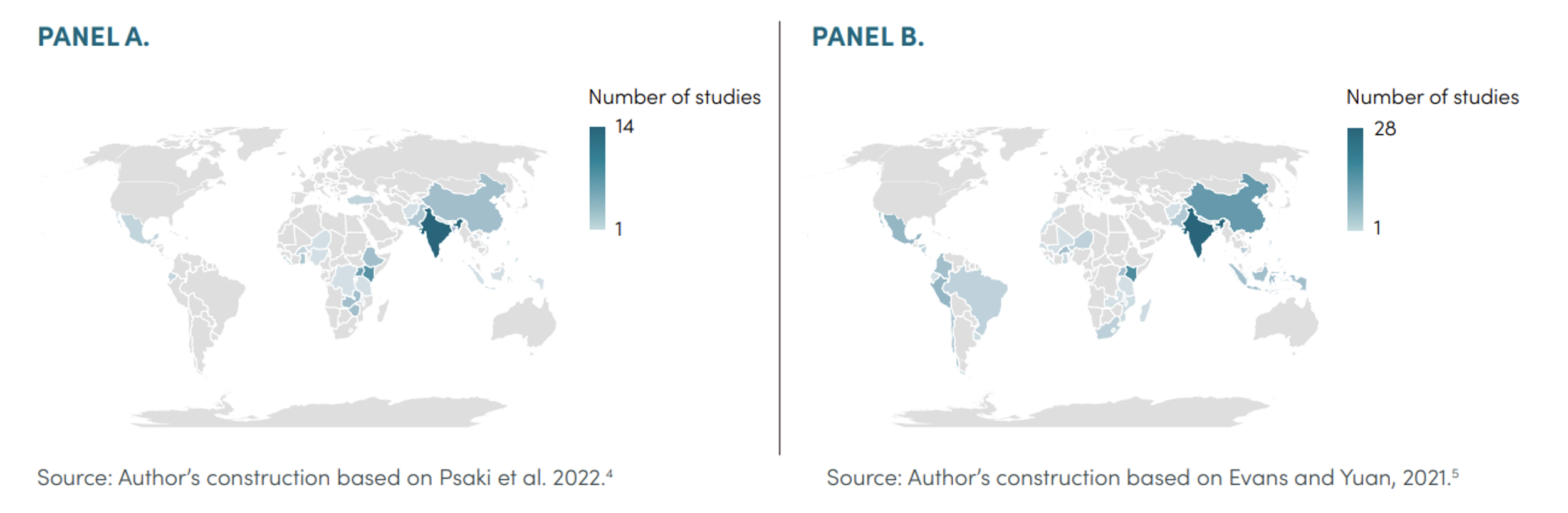

This paper reports the results of a systematic review identifying the most effective interventions to improve girls’ access to education and learning outcomes within an evidence base that includes both girl-targeted and general education interventions. The study poses three research questions: (1) Are girl-targeted interventions more effective for girls’ outcomes than general interventions? (2) For general, non-targeted interventions, do impacts on girls tend to be larger? and (3) In absolute terms, what are the most effective interventions for girls?

To answer these questions, the study collected and examined a large database of education studies with access or learning outcomes for students. It categorized the studies as either evaluating girl-targeted or non-targeted (i.e., general) interventions and identified all studies that reported gender-differentiated impacts. Only one in three studies of interventions not targeted to girls report disaggregated impacts by gender, so a first implication of this work is that in order to understand how best to improve girls' education, studies should consistently report impacts for girls. For those studies that did not report gender-differentiated impacts, the study contacted their authors asking them either to run the additional gender-differentiated analysis or to share the data. The effects of different programs were then standardized to increase comparability of effect sizes across studies. Ultimately, the effects for girls from 175 studies were synthesized. (The full list of studies is available in S1 of the supplementary online appendix .)

The study finds that general, nontargeted interventions perform similarly to girl-targeted interventions on average to increase both girls’ access to school and their learning in school. General interventions tend to have similar effects for girls and for boys. (The evidence suggests that if anything, girls benefit slightly more from general interventions, although the differences are not statistically significant.) In examining the most and least effective interventions for girls’ education, the study finds that girls’ access to school is more responsive to changes in costs, distance, and sanitation conditions; while girls’ learning is more likely to be improved by structured pedagogy and interventions that help teachers to teach at the right level. Later sections of the paper discuss the implications for inequality between boys and girls, cost-effectiveness of programs, and what circumstances lend themselves to general versus targeted interventions.

General, nontargeted interventions may be more politically palatable for scaling up by national governments – since constituents have both daughters and sons. 3 General interventions offer a wider array of evaluated interventions, giving policy makers a richer menu of options among nontargeted interventions to improve girls’ education. In countries where boys also struggle to achieve quality education, general interventions can simultaneously improve girls’ learning while benefitting boys as well. None of this suggests that programs will not benefit from considering gender issues in their design. For programs with a per-pupil expenditure (like cash transfers or scholarships), targeted versions will be significantly less costly for the simple reason that they will only need to budget for the cost of transfers or scholarships to girls (and not to boys). Some investments in quality, like pedagogical programs delivered through teachers, may be less sensitive to the number of beneficiary students.

This analysis is subject to certain limitations. First, there are far more general interventions than girl-targeted interventions. Second, not all general studies report gender-disaggregated results, although those results were obtained from the authors whenever possible, including for many studies that did not initially report them. Third, this study focuses on access to school and on learning outcomes, whereas some girl-targeted interventions may focus on other outcomes. Fourth, many of the interventions included in this review focus on primary education, and as girls reach adolescence, they may face more gender-specific constraints.

Bearing those caveats in mind, these results suggest that to achieve access and quality, especially in primary education, specifically targeting girls may not always be necessary to help those girls succeed. If policy makers want to help girls learn, one strategy will be to make schools better for all children.

The project gathered a large collection of studies that report education outcomes, either access or learning. For each of the studies, the project identified whether or not they separately report impacts for boys and girls. For studies that separately report impacts for boys and girls, this project extracted those data, standardized the estimates, and used them to compare the impacts for boys versus girls and across programs for girls. For studies that do not separately report, the researchers contacted the authors and asked them either to share the data or to provide the separate estimates themselves. This section reports on each step in detail.

Literature Search

The study began with a large database of education impact evaluations compiled for Evans and Popova (2016) and subsequently updated it. The database consists of 495 studies that were cited in 10 recent systematic reviews of evidence on what works to improve learning and access in low- and middle-income countries. 4 All the reviews were published or made publicly available between 2013 and 2015, and the studies included were conducted between 1980 and 2015. Another systematic review of interventions with a special focus on access outcomes came out in 2017 ( J-PAL 2017 ); its references added four studies to the database.

To increase the coverage of studies that were published (either as working papers or peer-reviewed articles) after 2015, the researchers conducted an additional literature search between October 2017 and January 2018. They searched Google Scholar and the websites of major institutions that conduct research related to low- and middle-income countries for working papers or research reports that were published between 2015 and 2017 containing the keywords “evidence,” “education,” “access,” “learning,” “enrollment,” “dropout,” “attendance,” or “score.” The same search terms were applied to several economics and education journals, which are listed in S2 of the supplementary online appendix . These two additional searches yielded 19 new studies. In total, 518 papers were reviewed.

Inclusion Criteria

The project included studies of education interventions (such as teacher professional development and providing textbooks), health interventions (such as providing deworming drugs and micronutrients), and safety net interventions (such as cash transfers). The present study only included studies that took place in preprimary, primary, and secondary schools in low- or middle-income countries, according to the World Bank definition ( World Bank 2020 ). To be included, studies had to be published – either as a working paper or a journal article – between 1980 and 2017 and had to report at least one of the following education outcomes: access outcomes (enrollment, dropout, or attendance) or learning outcomes (composite test score or any subject score). Nonacademic skill development programs for adolescents were not included.