An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PLoS Comput Biol

- v.9(7); 2013 Jul

Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review

Marco pautasso.

1 Centre for Functional and Evolutionary Ecology (CEFE), CNRS, Montpellier, France

2 Centre for Biodiversity Synthesis and Analysis (CESAB), FRB, Aix-en-Provence, France

Literature reviews are in great demand in most scientific fields. Their need stems from the ever-increasing output of scientific publications [1] . For example, compared to 1991, in 2008 three, eight, and forty times more papers were indexed in Web of Science on malaria, obesity, and biodiversity, respectively [2] . Given such mountains of papers, scientists cannot be expected to examine in detail every single new paper relevant to their interests [3] . Thus, it is both advantageous and necessary to rely on regular summaries of the recent literature. Although recognition for scientists mainly comes from primary research, timely literature reviews can lead to new synthetic insights and are often widely read [4] . For such summaries to be useful, however, they need to be compiled in a professional way [5] .

When starting from scratch, reviewing the literature can require a titanic amount of work. That is why researchers who have spent their career working on a certain research issue are in a perfect position to review that literature. Some graduate schools are now offering courses in reviewing the literature, given that most research students start their project by producing an overview of what has already been done on their research issue [6] . However, it is likely that most scientists have not thought in detail about how to approach and carry out a literature review.

Reviewing the literature requires the ability to juggle multiple tasks, from finding and evaluating relevant material to synthesising information from various sources, from critical thinking to paraphrasing, evaluating, and citation skills [7] . In this contribution, I share ten simple rules I learned working on about 25 literature reviews as a PhD and postdoctoral student. Ideas and insights also come from discussions with coauthors and colleagues, as well as feedback from reviewers and editors.

Rule 1: Define a Topic and Audience

How to choose which topic to review? There are so many issues in contemporary science that you could spend a lifetime of attending conferences and reading the literature just pondering what to review. On the one hand, if you take several years to choose, several other people may have had the same idea in the meantime. On the other hand, only a well-considered topic is likely to lead to a brilliant literature review [8] . The topic must at least be:

- interesting to you (ideally, you should have come across a series of recent papers related to your line of work that call for a critical summary),

- an important aspect of the field (so that many readers will be interested in the review and there will be enough material to write it), and

- a well-defined issue (otherwise you could potentially include thousands of publications, which would make the review unhelpful).

Ideas for potential reviews may come from papers providing lists of key research questions to be answered [9] , but also from serendipitous moments during desultory reading and discussions. In addition to choosing your topic, you should also select a target audience. In many cases, the topic (e.g., web services in computational biology) will automatically define an audience (e.g., computational biologists), but that same topic may also be of interest to neighbouring fields (e.g., computer science, biology, etc.).

Rule 2: Search and Re-search the Literature

After having chosen your topic and audience, start by checking the literature and downloading relevant papers. Five pieces of advice here:

- keep track of the search items you use (so that your search can be replicated [10] ),

- keep a list of papers whose pdfs you cannot access immediately (so as to retrieve them later with alternative strategies),

- use a paper management system (e.g., Mendeley, Papers, Qiqqa, Sente),

- define early in the process some criteria for exclusion of irrelevant papers (these criteria can then be described in the review to help define its scope), and

- do not just look for research papers in the area you wish to review, but also seek previous reviews.

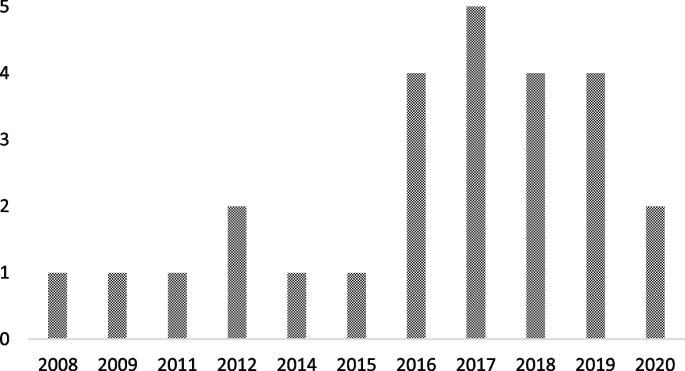

The chances are high that someone will already have published a literature review ( Figure 1 ), if not exactly on the issue you are planning to tackle, at least on a related topic. If there are already a few or several reviews of the literature on your issue, my advice is not to give up, but to carry on with your own literature review,

The bottom-right situation (many literature reviews but few research papers) is not just a theoretical situation; it applies, for example, to the study of the impacts of climate change on plant diseases, where there appear to be more literature reviews than research studies [33] .

- discussing in your review the approaches, limitations, and conclusions of past reviews,

- trying to find a new angle that has not been covered adequately in the previous reviews, and

- incorporating new material that has inevitably accumulated since their appearance.

When searching the literature for pertinent papers and reviews, the usual rules apply:

- be thorough,

- use different keywords and database sources (e.g., DBLP, Google Scholar, ISI Proceedings, JSTOR Search, Medline, Scopus, Web of Science), and

- look at who has cited past relevant papers and book chapters.

Rule 3: Take Notes While Reading

If you read the papers first, and only afterwards start writing the review, you will need a very good memory to remember who wrote what, and what your impressions and associations were while reading each single paper. My advice is, while reading, to start writing down interesting pieces of information, insights about how to organize the review, and thoughts on what to write. This way, by the time you have read the literature you selected, you will already have a rough draft of the review.

Of course, this draft will still need much rewriting, restructuring, and rethinking to obtain a text with a coherent argument [11] , but you will have avoided the danger posed by staring at a blank document. Be careful when taking notes to use quotation marks if you are provisionally copying verbatim from the literature. It is advisable then to reformulate such quotes with your own words in the final draft. It is important to be careful in noting the references already at this stage, so as to avoid misattributions. Using referencing software from the very beginning of your endeavour will save you time.

Rule 4: Choose the Type of Review You Wish to Write

After having taken notes while reading the literature, you will have a rough idea of the amount of material available for the review. This is probably a good time to decide whether to go for a mini- or a full review. Some journals are now favouring the publication of rather short reviews focusing on the last few years, with a limit on the number of words and citations. A mini-review is not necessarily a minor review: it may well attract more attention from busy readers, although it will inevitably simplify some issues and leave out some relevant material due to space limitations. A full review will have the advantage of more freedom to cover in detail the complexities of a particular scientific development, but may then be left in the pile of the very important papers “to be read” by readers with little time to spare for major monographs.

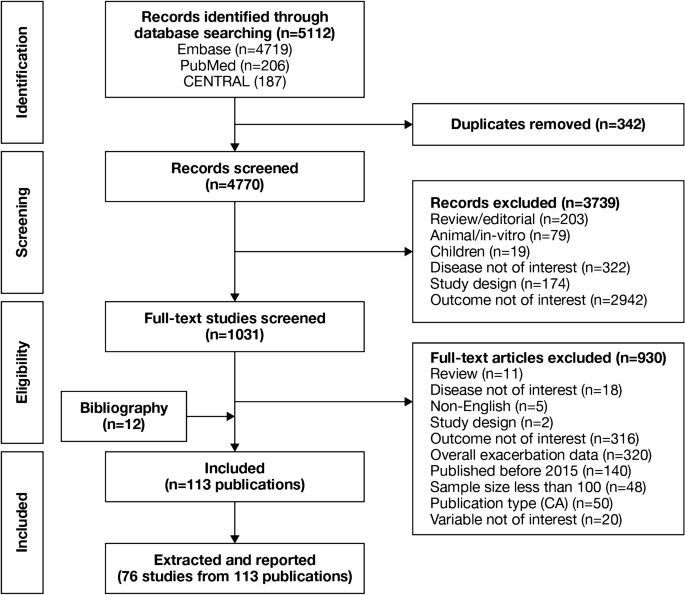

There is probably a continuum between mini- and full reviews. The same point applies to the dichotomy of descriptive vs. integrative reviews. While descriptive reviews focus on the methodology, findings, and interpretation of each reviewed study, integrative reviews attempt to find common ideas and concepts from the reviewed material [12] . A similar distinction exists between narrative and systematic reviews: while narrative reviews are qualitative, systematic reviews attempt to test a hypothesis based on the published evidence, which is gathered using a predefined protocol to reduce bias [13] , [14] . When systematic reviews analyse quantitative results in a quantitative way, they become meta-analyses. The choice between different review types will have to be made on a case-by-case basis, depending not just on the nature of the material found and the preferences of the target journal(s), but also on the time available to write the review and the number of coauthors [15] .

Rule 5: Keep the Review Focused, but Make It of Broad Interest

Whether your plan is to write a mini- or a full review, it is good advice to keep it focused 16 , 17 . Including material just for the sake of it can easily lead to reviews that are trying to do too many things at once. The need to keep a review focused can be problematic for interdisciplinary reviews, where the aim is to bridge the gap between fields [18] . If you are writing a review on, for example, how epidemiological approaches are used in modelling the spread of ideas, you may be inclined to include material from both parent fields, epidemiology and the study of cultural diffusion. This may be necessary to some extent, but in this case a focused review would only deal in detail with those studies at the interface between epidemiology and the spread of ideas.

While focus is an important feature of a successful review, this requirement has to be balanced with the need to make the review relevant to a broad audience. This square may be circled by discussing the wider implications of the reviewed topic for other disciplines.

Rule 6: Be Critical and Consistent

Reviewing the literature is not stamp collecting. A good review does not just summarize the literature, but discusses it critically, identifies methodological problems, and points out research gaps [19] . After having read a review of the literature, a reader should have a rough idea of:

- the major achievements in the reviewed field,

- the main areas of debate, and

- the outstanding research questions.

It is challenging to achieve a successful review on all these fronts. A solution can be to involve a set of complementary coauthors: some people are excellent at mapping what has been achieved, some others are very good at identifying dark clouds on the horizon, and some have instead a knack at predicting where solutions are going to come from. If your journal club has exactly this sort of team, then you should definitely write a review of the literature! In addition to critical thinking, a literature review needs consistency, for example in the choice of passive vs. active voice and present vs. past tense.

Rule 7: Find a Logical Structure

Like a well-baked cake, a good review has a number of telling features: it is worth the reader's time, timely, systematic, well written, focused, and critical. It also needs a good structure. With reviews, the usual subdivision of research papers into introduction, methods, results, and discussion does not work or is rarely used. However, a general introduction of the context and, toward the end, a recapitulation of the main points covered and take-home messages make sense also in the case of reviews. For systematic reviews, there is a trend towards including information about how the literature was searched (database, keywords, time limits) [20] .

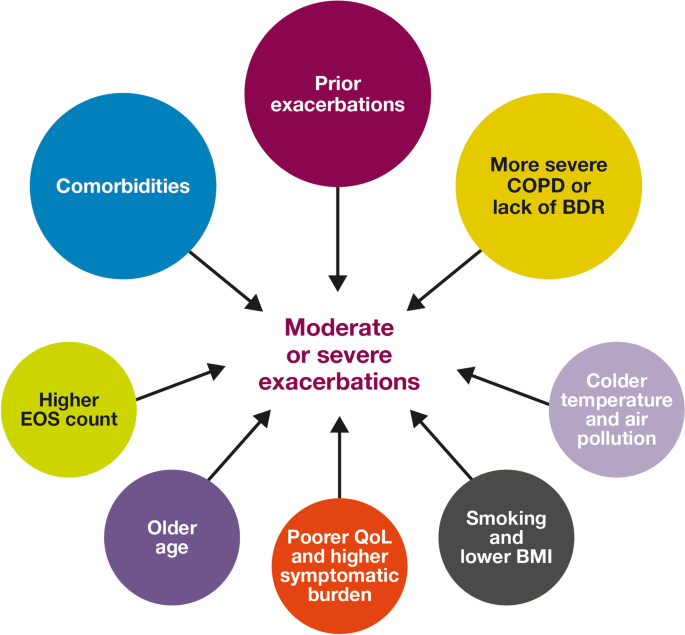

How can you organize the flow of the main body of the review so that the reader will be drawn into and guided through it? It is generally helpful to draw a conceptual scheme of the review, e.g., with mind-mapping techniques. Such diagrams can help recognize a logical way to order and link the various sections of a review [21] . This is the case not just at the writing stage, but also for readers if the diagram is included in the review as a figure. A careful selection of diagrams and figures relevant to the reviewed topic can be very helpful to structure the text too [22] .

Rule 8: Make Use of Feedback

Reviews of the literature are normally peer-reviewed in the same way as research papers, and rightly so [23] . As a rule, incorporating feedback from reviewers greatly helps improve a review draft. Having read the review with a fresh mind, reviewers may spot inaccuracies, inconsistencies, and ambiguities that had not been noticed by the writers due to rereading the typescript too many times. It is however advisable to reread the draft one more time before submission, as a last-minute correction of typos, leaps, and muddled sentences may enable the reviewers to focus on providing advice on the content rather than the form.

Feedback is vital to writing a good review, and should be sought from a variety of colleagues, so as to obtain a diversity of views on the draft. This may lead in some cases to conflicting views on the merits of the paper, and on how to improve it, but such a situation is better than the absence of feedback. A diversity of feedback perspectives on a literature review can help identify where the consensus view stands in the landscape of the current scientific understanding of an issue [24] .

Rule 9: Include Your Own Relevant Research, but Be Objective

In many cases, reviewers of the literature will have published studies relevant to the review they are writing. This could create a conflict of interest: how can reviewers report objectively on their own work [25] ? Some scientists may be overly enthusiastic about what they have published, and thus risk giving too much importance to their own findings in the review. However, bias could also occur in the other direction: some scientists may be unduly dismissive of their own achievements, so that they will tend to downplay their contribution (if any) to a field when reviewing it.

In general, a review of the literature should neither be a public relations brochure nor an exercise in competitive self-denial. If a reviewer is up to the job of producing a well-organized and methodical review, which flows well and provides a service to the readership, then it should be possible to be objective in reviewing one's own relevant findings. In reviews written by multiple authors, this may be achieved by assigning the review of the results of a coauthor to different coauthors.

Rule 10: Be Up-to-Date, but Do Not Forget Older Studies

Given the progressive acceleration in the publication of scientific papers, today's reviews of the literature need awareness not just of the overall direction and achievements of a field of inquiry, but also of the latest studies, so as not to become out-of-date before they have been published. Ideally, a literature review should not identify as a major research gap an issue that has just been addressed in a series of papers in press (the same applies, of course, to older, overlooked studies (“sleeping beauties” [26] )). This implies that literature reviewers would do well to keep an eye on electronic lists of papers in press, given that it can take months before these appear in scientific databases. Some reviews declare that they have scanned the literature up to a certain point in time, but given that peer review can be a rather lengthy process, a full search for newly appeared literature at the revision stage may be worthwhile. Assessing the contribution of papers that have just appeared is particularly challenging, because there is little perspective with which to gauge their significance and impact on further research and society.

Inevitably, new papers on the reviewed topic (including independently written literature reviews) will appear from all quarters after the review has been published, so that there may soon be the need for an updated review. But this is the nature of science [27] – [32] . I wish everybody good luck with writing a review of the literature.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to M. Barbosa, K. Dehnen-Schmutz, T. Döring, D. Fontaneto, M. Garbelotto, O. Holdenrieder, M. Jeger, D. Lonsdale, A. MacLeod, P. Mills, M. Moslonka-Lefebvre, G. Stancanelli, P. Weisberg, and X. Xu for insights and discussions, and to P. Bourne, T. Matoni, and D. Smith for helpful comments on a previous draft.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the French Foundation for Research on Biodiversity (FRB) through its Centre for Synthesis and Analysis of Biodiversity data (CESAB), as part of the NETSEED research project. The funders had no role in the preparation of the manuscript.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 8, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, what is your plagiarism score.

How To Find A-Grade Literature For Review

Sourcing, evaluating and organising.

By: David Phair (PhD) and Peter Quella (PhD) | January 2022

As we’ve discussed previously on our blog and YouTube channel, the first step of the literature review process is to source high-quality , relevant resources for your review, and to catalogue these pieces of literature in a systematic way so that you can digest and synthesise all the content efficiently.

In this article, we’ll look discuss 6 important things to keep in mind for the initial stage of your literature review so that you can source high-quality, relevant resources, quickly and efficiently. Let’s get started!

Overview: Literature Review Sourcing

- Develop and follow a clear literature search strategy

- Understand and use different types of literature correctly

- Carefully evaluate the quality of your potential sources

- Use a reference manager and a literature catalogue

- Read as broadly and comprehensively as possible

- Keep your golden thread front of mind throughout the process

1. Have a clear literature search strategy

As with any task in the research process, you need to have a clear plan of action before you get started, or you’ll end up wasting a lot of time and energy. So, before you begin your literature review , it’s useful to develop a simple search strategy . Broadly speaking, a good literature search strategy should include the following steps:

Step one – Clearly identify your golden thread

Your golden thread consists of your research aims , research objectives and research questions . These three components should be tightly aligned to form the focus of your research. If you’re unclear what your research aims and research questions are, you’re not going to have a clear direction when trying to source literature. As a result, you’re going to waste a lot of time reviewing irrelevant resources.

So, make sure that you have clarity regarding your golden thread before you start searching for literature. Of course, your research aims, objectives and questions may evolve or shift as a result of the literature review process (in fact, this is quite common), but you still need to have a clear focus to get things started.

Step two – Develop a keyword/keyphrase list

Once you’ve clearly articulated your golden thread in terms of the research aims, objectives and questions, the next step is to develop a list of keywords or keyphrases, based on these three elements (the golden thread). You’ll also want to include synonyms and alternative spellings (for example, American vs British English) in your list.

For example, if your research aims and research questions involve investigating organisational trust , your keyword list might include:

- Organisational trust

- Organizational trust (US spelling)

- Consumer trust

- Brand trust

- Online trust

When it comes to brainstorming keywords, the more the better . Don’t hold back at this stage. You’ll quickly find out which ones are useful, and which aren’t when you start searching. So, it’s best to just go as broad as possible here to ensure you cast a wide net.

Step three – Identify the relevant databases

Now that you’ve got a comprehensive set of keywords, the next step is to identify which literature databases will be most useful and relevant for your particular study. There are hundreds, if not thousands of databases out there, and they are often subject or discipline-specific . For example, within the medicine space, Medline is a popular one.

To identify relevant databases, it’s best to speak to your research advisor/supervisor, Grad Coach or a librarian at your university library. Oftentimes, a quick chat with a skilled librarian can yield tremendous insight. Don’t be shy to ask – chances are, they’ll be thrilled that you asked!

At this stage, you might be asking, “why not just use Google Scholar?”. Of course, an academic search engine like Google Scholar will be useful in terms of getting started and finding a broad range of resources, but it won’t always present every possible resource or the best quality resources. It also has limited filtering options compared to some of the specialist databases, so you shouldn’t rely purely on Google Scholar.

Step four – Use Boolean operators to refine your search

Once you’ve identified your keywords and databases, it’s time to start searching for literature – hooray! However, you’ll quickly find that there is a seemingly endless number of journal articles to sift through, and you have limited time to work through the literature. So, you’ll need to get smart about how you use these databases – enter Boolean operators.

Boolean operators are special characters that allow you to refine your search. Common operators include:

- AND – only show results that contain both X and Y

- OR – show results that contain X or Y

- NOT – show results that include X, but not Y

These operators are incredibly useful, especially when there are topics that are very similar to yours but are not relevant . For example, if you’re researching something about the growth of apples, you’ll want to exclude all literature related to Apple, the company. Boolean operators allow you to cut out the irrelevant content and improve the signal to noise ratio in your search.

Need a helping hand?

2. Use different types of literature correctly

Once you start searching for literature, you’ll quickly notice that there are different “types” of resources that come up. It’s important to understand the different types of literature available to you and how to use each of them appropriately.

Generally speaking, you’ll find three categories of literature:

Primary literature

Secondary literature

Tertiary literature

Primary literature refers to journal articles , typically peer reviewed, which document a study that was undertaken, where data were collected and analysed, and findings were discussed. For example, a journal article that involves the collection and analysis of survey data to identify differences in personality between two groups of people.

Primary literature should, ideally, form the foundation of your literature review – the bread and butter, so to speak. You’ll likely refer to many of the arguments made and findings identified in these types of articles to build your own arguments throughout your literature review. You’ll also rely on these types of articles for theoretical models and frameworks, which may form the foundation of your own proposed framework, depending on the nature of your research.

Lastly, primary literature can be a useful source of measurement scales for quantitative studies. For example, many journal articles will include a copy of the survey measures they used at the end of the article, which will typically be reliable and valid. You can either use these “as is” or as a foundation for your own survey measures .

So, long story short, you’ll need a good stockpile of these types of resources. They are, admittedly, more “dense” and challenging to digest than the other types of literature, but taking the time to work through them will pay off greatly.

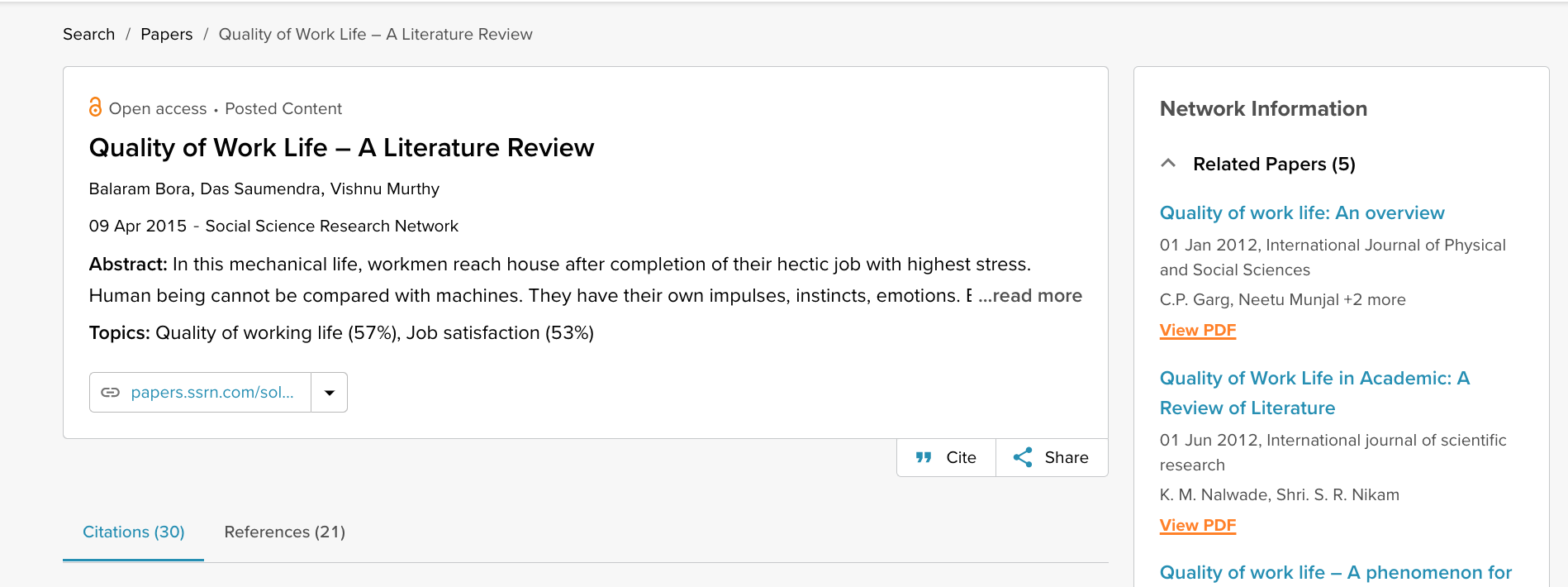

Secondary literature refers to journal articles that summarise and integrate the findings from primary literature. For example, you’ll likely find “review of the literature” type journal articles which provide an overview of the current state of the research (at the time of publication, of course).

Secondary literature is very useful for orienting yourself with regards to the current state of knowledge and identifying key researchers , seminal works and so on. In other words, they’re a good tool to make sure you’ve got a broad, comprehensive view of what all is out there. They’re not going to give you the level of detail that primary literature will (and they’ll likely be a bit outdated), but they’ll point you in the right direction.

In practical terms, it’s a good idea to start by reviewing secondary literature-type articles to help you get a bird’s eye view of the landscape and then dive deeper into the primary literature to get a grasp of the specifics and to bring your knowledge up to date with the most current studies.

The final category of literature refers to sources that would be considered less academic and scientifically rigorous in nature, but up to date and highly relevant. For example, sources such as current industry and country reports published by management consulting groups, news articles, blog posts and so on.

While these sources are not as credible and trustworthy as journal articles (especially peer-reviewed ones), they can provide very up to date information , whereas academic research tends to roll out quite slowly. Therefore, they can be very useful for contextualising your research topic and/or demonstrating a current trend. Quite often, you’d cite these types of sources in your introduction chapter rather than your literature review chapter, but you may still have use for them in the latter.

In summary, it’s important to understand the three different types of literature – primary, secondary and tertiary, and use them appropriately in your dissertation, thesis or research project.

3. Carefully evaluate the quality of your sources

As we’ve alluded to, not all literature is created equally. Not only does literature vary in terms of type (i.e., primary vs secondary), it also varies in terms of overall quality .

Simply put, all sources exist on a quality spectrum . On the high end of the spectrum are peer-reviewed articles published in popular, credible journals. Next are journal articles that are not peer-reviewed, or that are published in lower quality or lesser-known journals. In the middle are sources like textbooks and reports by professional organisations (e.g., management consulting firms). On the low end are sources like newspapers, blog posts and social media posts.

As you can probably see, this loosely reflects the categories we mentioned previously (primary, secondary and tertiary literature), so there is once again a trade-off between quality and recency . Therefore, you need to carefully evaluate the quality of each potential source and let this inform how you use it in your literature review. Importantly, this doesn’t mean that you can’t include a newspaper article or blog post as a source – it just means that you shouldn’t rely too heavily on these types of courses as the core of your argument.

When evaluating journal articles, you can consider their citation count (i.e., the number of other articles that reference them) as a quality indicator. But keep in mind that citation count is a product of many factors , including the popularity of the article, the popularity of the research field and most importantly, time. In other words, it’s natural for newer articles to have lower citation counts. This is useful to keep in mind, as you ideally want to focus on more recent literature (published within the last 3-5 years) in your literature review.

In summary, aim to focus on higher-quality literature , especially when you’re building core arguments in your literature review. You don’t, for example, want to make an argument regarding the importance and novelty of your research (i.e., its justification) based on some blogger’s opinion.

4. Use a reference manager and literature catalogue

As you review the literature and build your collection of potential sources, you’ll need a way to stay on top of all the details. To this end, it’s essential that you make use of both a reference manager and a literature catalogue . Let’s take a look at each of these.

The reference manager

Reference management software helps you store the reference information for each of your articles and manages the citation and reference list building task as you write up your actual literature review chapter. In other words, a reference manager ensures that your citations and reference list are correctly formatted in the reference style required by your university – e.g., Harvard, APA , MLA, etc.

Using a reference manager saves you the hassle of trying to manually type out your in-text citations and reference list, which you’re bound to mess up in some way. A simple comma out of place, incorrect italicisation or boldfacing can result in you losing marks, and that’s highly likely when you’re dealing with a large number of references. So, it just makes sense to use a piece of software for this task.

The good news is that there are loads of options , many of which are free . For new researchers, we usually recommend Mendeley or Zotero . So, don’t waste your time trying to manage your references manually – get yourself a reference manager ASAP.

The literature catalogue

The second tool you’ll need is a literature catalogue. This is simply an Excel document that you can easily compile yourself (or download our free one here ), where you list and categorise all your literature. You might doubt whether it’s really necessary to have a separate catalogue when you’ve already logged your reference data in a reference manager, but trust us, you’re going to need it. It’s quite common that throughout the literature review process, you’ll review hundreds of articles , so it’s simply impossible that you’ll remember all the details.

What makes a literature catalogue extremely powerful is that you can store as much information as you want for each piece of literature that you include (whereas a reference manager only includes basic fields). Typically, you would include things like:

- Title of the article

- One-line summary of the research

- Key findings and takeaways

- Context (i.e. where did it take place)

- Useful quotes

- Methodology (e.g. qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods)

- Category (you can customise as many categories as makes sense for you)

- Quality of resource

- Type of literature (e.g. primary, secondary or tertiary)

These are just some examples – ultimately you need to customise your catalogue to suit your needs. But, as you can see, the more detailed you get, the more useful your catalogue will become when it’s time to synthesise the research and write up your literature. For example, you could quickly filter the catalogue to display all papers that support a certain hypothesis, that argue in a specific direction, or that were written at a certain time.

5. Read widely (and efficiently)

As we’ve discussed in other posts , the purpose of the literature review chapter is to present and synthesise the current state of knowledge in relation to your research aims, objectives and research questions. To do this, you’ll need to read as broadly and comprehensively as possible. You’ll need to demonstrate to your marker that you “know your stuff” and have a strong understanding of the relevant literature.

Ideally, your literature review should include an eclectic mix of research that features multiple perspectives . In other words, you need to avoid getting tunnel vision and running down one narrow stream of literature. Ideally, you want to highlight both the agreements and disagreements in the literature to show that you’ve got a well-balanced view of the situation.

If your topic is particularly novel and there isn’t a lot of literature available, you can focus your efforts on adjacent literature . For example, if you’re researching factors that cultivate organisational trust in Germany, but there’s very little literature on this, you can draw on US and UK-based studies to form your theoretical foundation. Similarly, if you’re investigating an occurrence in an under-researched industry, you can look at other industries for literature.

As you read each journal article, be sure to scan the reference list for further reading (this technique is called “snowballing”). By doing this, you will quickly identify key literature within a topic area and fast-track your literature review process. You can also check which articles have cited any given article using Google Scholar, which will give you a “forward view” in terms of the progress of the literature.

Given that you’ll need to work through a large amount of literature, it’s useful to adopt a “strategic skimming ” approach when you’re initially assessing articles, so that you don’t need to read the entire journal article . In practical terms, this means you can focus on just the title and abstract at first, and if the article seems relevant based on those, you can jump to the findings section and limitations section. These sections will give you a solid indicator as to whether the resource is relevant to your study, which you can then shortlist for full reading.

6. Keep your golden thread front of mind

Your golden thread (i.e., your research aims, objectives and research questions) needs to guide every decision you make throughout your dissertation, thesis, or research project. This is especially true in the literature review stage, as the golden thread should act as a litmus test for relevance whenever you’re reviewing potential articles or resources. In other words, if an article doesn’t relate to your golden thread, its probably not worth spending time on.

Keep in mind that your research aims, objectives and research questions may evolve as a result of the literature review process. For example, you may find that after reviewing the literature in more depth, your topic focus is not as novel as you originally thought, or that there’s an adjacent area that is more deserving of investigation. This is perfectly natural, so don’t be surprised if your focus shifts somewhat during the review process. Just remember to update your literature review in this case and be sure to update any previous chapters so that your document has a consistent focus throughout.

Wrapping up

In this article, we covered 6 pointers to help you find and evaluate high-quality resources for your literature review. To recap:

- Understand and use different types of literature for the right purpose

If you have any questions, please feel free to leave a comment . Alternatively, if you’d like hands-on help with your literature review, be sure to check out our 1-on-1 private coaching services here.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling Udemy Course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

this is very helpful to any researcher, I am learning this for the benefit of myself and overs as a library staff

Of course this is useful to most of researchers. I have learnt a lot issues which are relevant to teaching research. Surely they will enjoy my research sessions.

Thank you. Very clear and concise

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How To Write A Literature Review - A Complete Guide

Table of Contents

A literature review is much more than just another section in your research paper. It forms the very foundation of your research. It is a formal piece of writing where you analyze the existing theoretical framework, principles, and assumptions and use that as a base to shape your approach to the research question.

Curating and drafting a solid literature review section not only lends more credibility to your research paper but also makes your research tighter and better focused. But, writing literature reviews is a difficult task. It requires extensive reading, plus you have to consider market trends and technological and political changes, which tend to change in the blink of an eye.

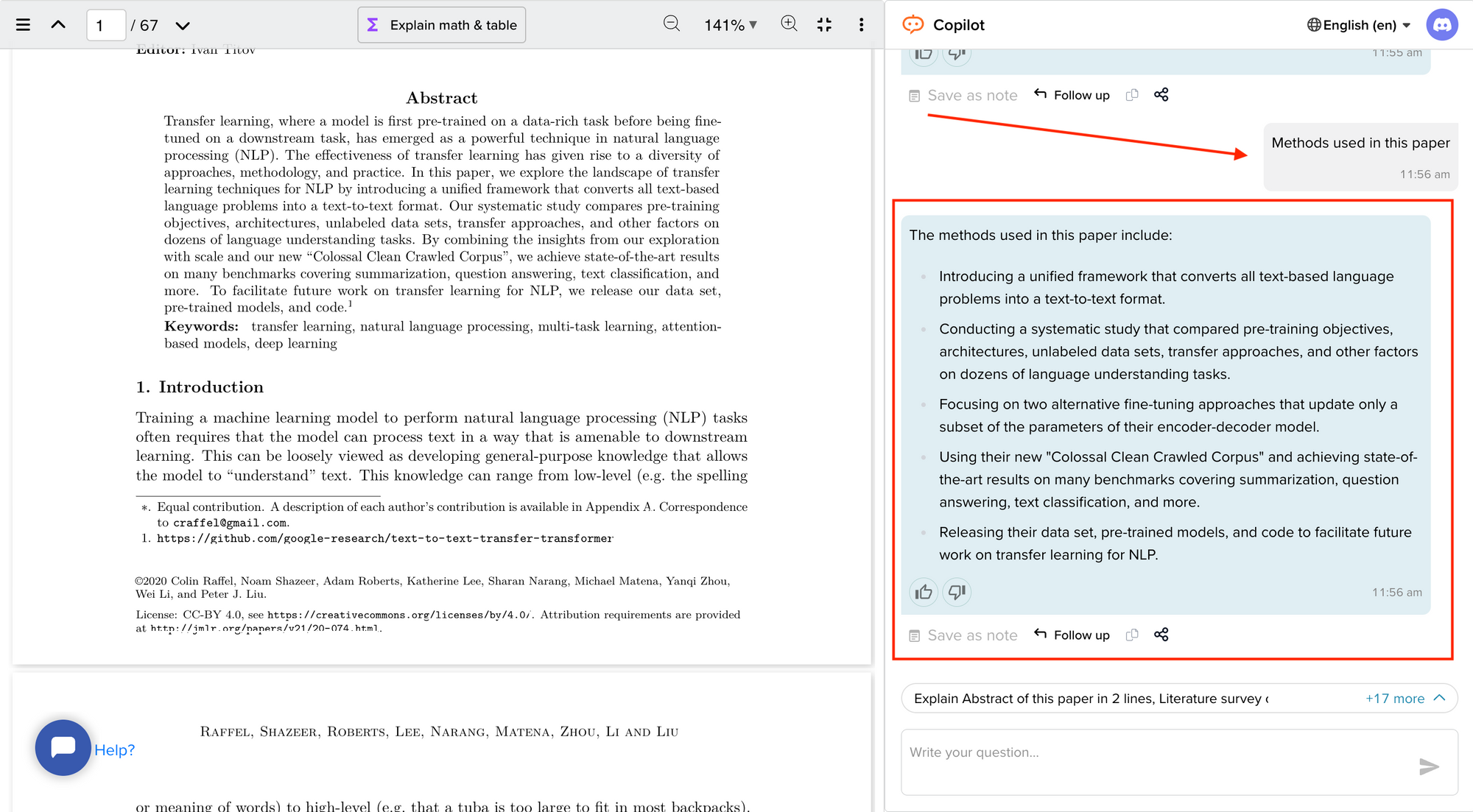

Now streamline your literature review process with the help of SciSpace Copilot. With this AI research assistant, you can efficiently synthesize and analyze a vast amount of information, identify key themes and trends, and uncover gaps in the existing research. Get real-time explanations, summaries, and answers to your questions for the paper you're reviewing, making navigating and understanding the complex literature landscape easier.

In this comprehensive guide, we will explore everything from the definition of a literature review, its appropriate length, various types of literature reviews, and how to write one.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a collation of survey, research, critical evaluation, and assessment of the existing literature in a preferred domain.

Eminent researcher and academic Arlene Fink, in her book Conducting Research Literature Reviews , defines it as the following:

“A literature review surveys books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated.

Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have explored while researching a particular topic, and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within a larger field of study.”

Simply put, a literature review can be defined as a critical discussion of relevant pre-existing research around your research question and carving out a definitive place for your study in the existing body of knowledge. Literature reviews can be presented in multiple ways: a section of an article, the whole research paper itself, or a chapter of your thesis.

A literature review does function as a summary of sources, but it also allows you to analyze further, interpret, and examine the stated theories, methods, viewpoints, and, of course, the gaps in the existing content.

As an author, you can discuss and interpret the research question and its various aspects and debate your adopted methods to support the claim.

What is the purpose of a literature review?

A literature review is meant to help your readers understand the relevance of your research question and where it fits within the existing body of knowledge. As a researcher, you should use it to set the context, build your argument, and establish the need for your study.

What is the importance of a literature review?

The literature review is a critical part of research papers because it helps you:

- Gain an in-depth understanding of your research question and the surrounding area

- Convey that you have a thorough understanding of your research area and are up-to-date with the latest changes and advancements

- Establish how your research is connected or builds on the existing body of knowledge and how it could contribute to further research

- Elaborate on the validity and suitability of your theoretical framework and research methodology

- Identify and highlight gaps and shortcomings in the existing body of knowledge and how things need to change

- Convey to readers how your study is different or how it contributes to the research area

How long should a literature review be?

Ideally, the literature review should take up 15%-40% of the total length of your manuscript. So, if you have a 10,000-word research paper, the minimum word count could be 1500.

Your literature review format depends heavily on the kind of manuscript you are writing — an entire chapter in case of doctoral theses, a part of the introductory section in a research article, to a full-fledged review article that examines the previously published research on a topic.

Another determining factor is the type of research you are doing. The literature review section tends to be longer for secondary research projects than primary research projects.

What are the different types of literature reviews?

All literature reviews are not the same. There are a variety of possible approaches that you can take. It all depends on the type of research you are pursuing.

Here are the different types of literature reviews:

Argumentative review

It is called an argumentative review when you carefully present literature that only supports or counters a specific argument or premise to establish a viewpoint.

Integrative review

It is a type of literature review focused on building a comprehensive understanding of a topic by combining available theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence.

Methodological review

This approach delves into the ''how'' and the ''what" of the research question — you cannot look at the outcome in isolation; you should also review the methodology used.

Systematic review

This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research and collect, report, and analyze data from the studies included in the review.

Meta-analysis review

Meta-analysis uses statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects than those derived from the individual studies included within a review.

Historical review

Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, or phenomenon emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and identify future research's likely directions.

Theoretical Review

This form aims to examine the corpus of theory accumulated regarding an issue, concept, theory, and phenomenon. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories exist, the relationships between them, the degree the existing approaches have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested.

Scoping Review

The Scoping Review is often used at the beginning of an article, dissertation, or research proposal. It is conducted before the research to highlight gaps in the existing body of knowledge and explains why the project should be greenlit.

State-of-the-Art Review

The State-of-the-Art review is conducted periodically, focusing on the most recent research. It describes what is currently known, understood, or agreed upon regarding the research topic and highlights where there are still disagreements.

Can you use the first person in a literature review?

When writing literature reviews, you should avoid the usage of first-person pronouns. It means that instead of "I argue that" or "we argue that," the appropriate expression would be "this research paper argues that."

Do you need an abstract for a literature review?

Ideally, yes. It is always good to have a condensed summary that is self-contained and independent of the rest of your review. As for how to draft one, you can follow the same fundamental idea when preparing an abstract for a literature review. It should also include:

- The research topic and your motivation behind selecting it

- A one-sentence thesis statement

- An explanation of the kinds of literature featured in the review

- Summary of what you've learned

- Conclusions you drew from the literature you reviewed

- Potential implications and future scope for research

Here's an example of the abstract of a literature review

Is a literature review written in the past tense?

Yes, the literature review should ideally be written in the past tense. You should not use the present or future tense when writing one. The exceptions are when you have statements describing events that happened earlier than the literature you are reviewing or events that are currently occurring; then, you can use the past perfect or present perfect tenses.

How many sources for a literature review?

There are multiple approaches to deciding how many sources to include in a literature review section. The first approach would be to look level you are at as a researcher. For instance, a doctoral thesis might need 60+ sources. In contrast, you might only need to refer to 5-15 sources at the undergraduate level.

The second approach is based on the kind of literature review you are doing — whether it is merely a chapter of your paper or if it is a self-contained paper in itself. When it is just a chapter, sources should equal the total number of pages in your article's body. In the second scenario, you need at least three times as many sources as there are pages in your work.

Quick tips on how to write a literature review

To know how to write a literature review, you must clearly understand its impact and role in establishing your work as substantive research material.

You need to follow the below-mentioned steps, to write a literature review:

- Outline the purpose behind the literature review

- Search relevant literature

- Examine and assess the relevant resources

- Discover connections by drawing deep insights from the resources

- Structure planning to write a good literature review

1. Outline and identify the purpose of a literature review

As a first step on how to write a literature review, you must know what the research question or topic is and what shape you want your literature review to take. Ensure you understand the research topic inside out, or else seek clarifications. You must be able to the answer below questions before you start:

- How many sources do I need to include?

- What kind of sources should I analyze?

- How much should I critically evaluate each source?

- Should I summarize, synthesize or offer a critique of the sources?

- Do I need to include any background information or definitions?

Additionally, you should know that the narrower your research topic is, the swifter it will be for you to restrict the number of sources to be analyzed.

2. Search relevant literature

Dig deeper into search engines to discover what has already been published around your chosen topic. Make sure you thoroughly go through appropriate reference sources like books, reports, journal articles, government docs, and web-based resources.

You must prepare a list of keywords and their different variations. You can start your search from any library’s catalog, provided you are an active member of that institution. The exact keywords can be extended to widen your research over other databases and academic search engines like:

- Google Scholar

- Microsoft Academic

- Science.gov

Besides, it is not advisable to go through every resource word by word. Alternatively, what you can do is you can start by reading the abstract and then decide whether that source is relevant to your research or not.

Additionally, you must spend surplus time assessing the quality and relevance of resources. It would help if you tried preparing a list of citations to ensure that there lies no repetition of authors, publications, or articles in the literature review.

3. Examine and assess the sources

It is nearly impossible for you to go through every detail in the research article. So rather than trying to fetch every detail, you have to analyze and decide which research sources resemble closest and appear relevant to your chosen domain.

While analyzing the sources, you should look to find out answers to questions like:

- What question or problem has the author been describing and debating?

- What is the definition of critical aspects?

- How well the theories, approach, and methodology have been explained?

- Whether the research theory used some conventional or new innovative approach?

- How relevant are the key findings of the work?

- In what ways does it relate to other sources on the same topic?

- What challenges does this research paper pose to the existing theory

- What are the possible contributions or benefits it adds to the subject domain?

Be always mindful that you refer only to credible and authentic resources. It would be best if you always take references from different publications to validate your theory.

Always keep track of important information or data you can present in your literature review right from the beginning. It will help steer your path from any threats of plagiarism and also make it easier to curate an annotated bibliography or reference section.

4. Discover connections

At this stage, you must start deciding on the argument and structure of your literature review. To accomplish this, you must discover and identify the relations and connections between various resources while drafting your abstract.

A few aspects that you should be aware of while writing a literature review include:

- Rise to prominence: Theories and methods that have gained reputation and supporters over time.

- Constant scrutiny: Concepts or theories that repeatedly went under examination.

- Contradictions and conflicts: Theories, both the supporting and the contradictory ones, for the research topic.

- Knowledge gaps: What exactly does it fail to address, and how to bridge them with further research?

- Influential resources: Significant research projects available that have been upheld as milestones or perhaps, something that can modify the current trends

Once you join the dots between various past research works, it will be easier for you to draw a conclusion and identify your contribution to the existing knowledge base.

5. Structure planning to write a good literature review

There exist different ways towards planning and executing the structure of a literature review. The format of a literature review varies and depends upon the length of the research.

Like any other research paper, the literature review format must contain three sections: introduction, body, and conclusion. The goals and objectives of the research question determine what goes inside these three sections.

Nevertheless, a good literature review can be structured according to the chronological, thematic, methodological, or theoretical framework approach.

Literature review samples

1. Standalone

2. As a section of a research paper

How SciSpace Discover makes literature review a breeze?

SciSpace Discover is a one-stop solution to do an effective literature search and get barrier-free access to scientific knowledge. It is an excellent repository where you can find millions of only peer-reviewed articles and full-text PDF files. Here’s more on how you can use it:

Find the right information

Find what you want quickly and easily with comprehensive search filters that let you narrow down papers according to PDF availability, year of publishing, document type, and affiliated institution. Moreover, you can sort the results based on the publishing date, citation count, and relevance.

Assess credibility of papers quickly

When doing the literature review, it is critical to establish the quality of your sources. They form the foundation of your research. SciSpace Discover helps you assess the quality of a source by providing an overview of its references, citations, and performance metrics.

Get the complete picture in no time

SciSpace Discover’s personalized suggestion engine helps you stay on course and get the complete picture of the topic from one place. Every time you visit an article page, it provides you links to related papers. Besides that, it helps you understand what’s trending, who are the top authors, and who are the leading publishers on a topic.

Make referring sources super easy

To ensure you don't lose track of your sources, you must start noting down your references when doing the literature review. SciSpace Discover makes this step effortless. Click the 'cite' button on an article page, and you will receive preloaded citation text in multiple styles — all you've to do is copy-paste it into your manuscript.

Final tips on how to write a literature review

A massive chunk of time and effort is required to write a good literature review. But, if you go about it systematically, you'll be able to save a ton of time and build a solid foundation for your research.

We hope this guide has helped you answer several key questions you have about writing literature reviews.

Would you like to explore SciSpace Discover and kick off your literature search right away? You can get started here .

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. how to start a literature review.

• What questions do you want to answer?

• What sources do you need to answer these questions?

• What information do these sources contain?

• How can you use this information to answer your questions?

2. What to include in a literature review?

• A brief background of the problem or issue

• What has previously been done to address the problem or issue

• A description of what you will do in your project

• How this study will contribute to research on the subject

3. Why literature review is important?

The literature review is an important part of any research project because it allows the writer to look at previous studies on a topic and determine existing gaps in the literature, as well as what has already been done. It will also help them to choose the most appropriate method for their own study.

4. How to cite a literature review in APA format?

To cite a literature review in APA style, you need to provide the author's name, the title of the article, and the year of publication. For example: Patel, A. B., & Stokes, G. S. (2012). The relationship between personality and intelligence: A meta-analysis of longitudinal research. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(1), 16-21

5. What are the components of a literature review?

• A brief introduction to the topic, including its background and context. The introduction should also include a rationale for why the study is being conducted and what it will accomplish.

• A description of the methodologies used in the study. This can include information about data collection methods, sample size, and statistical analyses.

• A presentation of the findings in an organized format that helps readers follow along with the author's conclusions.

6. What are common errors in writing literature review?

• Not spending enough time to critically evaluate the relevance of resources, observations and conclusions.

• Totally relying on secondary data while ignoring primary data.

• Letting your personal bias seep into your interpretation of existing literature.

• No detailed explanation of the procedure to discover and identify an appropriate literature review.

7. What are the 5 C's of writing literature review?

• Cite - the sources you utilized and referenced in your research.

• Compare - existing arguments, hypotheses, methodologies, and conclusions found in the knowledge base.

• Contrast - the arguments, topics, methodologies, approaches, and disputes that may be found in the literature.

• Critique - the literature and describe the ideas and opinions you find more convincing and why.

• Connect - the various studies you reviewed in your research.

8. How many sources should a literature review have?

When it is just a chapter, sources should equal the total number of pages in your article's body. if it is a self-contained paper in itself, you need at least three times as many sources as there are pages in your work.

9. Can literature review have diagrams?

• To represent an abstract idea or concept

• To explain the steps of a process or procedure

• To help readers understand the relationships between different concepts

10. How old should sources be in a literature review?

Sources for a literature review should be as current as possible or not older than ten years. The only exception to this rule is if you are reviewing a historical topic and need to use older sources.

11. What are the types of literature review?

• Argumentative review

• Integrative review

• Methodological review

• Systematic review

• Meta-analysis review

• Historical review

• Theoretical review

• Scoping review

• State-of-the-Art review

12. Is a literature review mandatory?

Yes. Literature review is a mandatory part of any research project. It is a critical step in the process that allows you to establish the scope of your research, and provide a background for the rest of your work.

But before you go,

- Six Online Tools for Easy Literature Review

- Evaluating literature review: systematic vs. scoping reviews

- Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review

- Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

- Library Homepage

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide: Strategies to Finding Sources

- Literature Reviews?

- Strategies to Finding Sources

- Keeping up with Research!

- Evaluating Sources & Literature Reviews

- Organizing for Writing

- Writing Literature Review

- Other Academic Writings

Useful Tool to Develop your Topic

Watch this video about Concept Mapping to become a Research Pro!

- Mind Mapping (also known as Concept Mapping) A helpful handout to show step by step how to create a concept map to map out a topic.

The Research Process

![selecting articles for literature review Interative Litearture Review Research Process image (Planning, Searching, Organizing, Analyzing and Writing [repeat at necessary]](https://libapps.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/64450/images/ResearchProcess.jpg)

Planning : Before searching for articles or books, brainstorm to develop keywords that best describe your research question.

Searching : While searching take note of what other keywords are used to describe your topic and use them to do more searches

♠ Most articles include a keyword section

♠ Key concepts names may change through time so make sure to check for variations

Organizing : Start organizing your results by categories/key concepts or any organizing principle that make sense for you. This will help you later when you are ready to analyze your findings

Analyzing : While reading, start making notes of key concepts and commonalities and disagreement among the research articles you find.

♠ Create a spreadsheet document to record what articles you are finding useful and why.

♠ Create fields to write summaries of articles or quotes for future citing and paraphrasing .

Writing : Synthesize your findings. Use your own voice to explain to your readers what you learned about the literature your search; its weaknesses and strengths; what is missing or ignored

Repeat : at any given time of the process you can go back to a previous step as necessary

Advanced Searching

- Boolean Searching (AND, OR, NOT): Words that help you connect your terms in a logical way for the system understand you

- Proximity Searching (N/# or W/#): It allows you to search for two or more words that occur within a specified number of words (or fewer) of each other in the databases.

- Limiters/Filters : These are options available on the advanced page to let you control what type of document you want to search (articles), dates, language, peer-review, etc...

- Question mark (?) or a pound sign (#) for wildcard: useful when you don't know how something is spelled out, e.g. if you are looking about articles about color, if you want to find articles with the spelling colour (British English), you can use colo?r to find either spelling.

- Asterisk (*) for truncation: useful for getting results with keywords with multiple endings, e.g. comput* for computer, computers, computing , etc.

- UC Library Search Explained! Check the Search tips to better used our library catalog and articles search system

- EBSCOhost Searching Tips An useful guide about how to best search EBSCOhost databases

- ProQuest Database Search Tips An useful guide about how to best search ProQuest databases

- Are you working on an emerging topic? You are not likely to find many sources, which is good because you are trying to prove that this is a topic that needs more research. But, it is not enough to say that you found few or no articles on your topic in your field. You need to look broadly to other disciplines (also known as triangulation ) to see if your research topic has been studied from other perspectives as a way to validate the uniqueness of your research question.

- Are you working on something that has been studied extensively? Then you are going to find many sources and you will want to limit how far you want to look back. Use limiters to eliminate research that may be dated and opt to search for resources published within the last 5-10 years.

- Want to keep track of your searches , send alerts to your email when new articles in your topic are available? Create an account in any of our databases!

Following the Citation Trail!

Many databases today have special featured that show you how many times an article was cited by and by who and offer you links to those articles.

See below some recommended resources: