An Unemployment Crisis after the Onset of COVID-19

Nicolas Petrosky-Nadeau and Robert G. Valletta

Download PDF (115 KB)

FRBSF Economic Letter 2020-12 | May 18, 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic has upended the U.S. labor market, with massive job losses and a spike in unemployment to its highest level since the Great Depression. How long unemployment will remain at crisis levels is highly uncertain and will depend on the speed and success of coronavirus containment measures. Historical patterns of monthly flows in and out of unemployment, adjusted for unique aspects of the coronavirus economy, can help in assessing potential paths of unemployment. Unless hiring rises to unprecedented levels, unemployment could remain severely elevated well into next year.

The wave of initial job losses during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has been massive, with more than 20 million jobs swept away between March and April. This is much larger than losses recorded during similar time frames in any other postwar recession. As a result, the April unemployment rate spiked to the highest level recorded since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

In this Economic Letter , we assess possible paths for unemployment through 2021. Although the initial scale of the crisis is clear, substantial uncertainty surrounds the future path of unemployment. This uncertainty primarily revolves around the success of virus containment measures and how quickly economic activity can recover. Fundamental measurement challenges are also likely to affect the official unemployment rate: some laid-off workers cannot actively search for new jobs because of shelter-in-place restrictions and hence may be counted as out of the labor force, rather than unemployed.

To assess the possible path of the measured unemployment rate through next year, we focus on the underlying monthly flows in and out of unemployment, accounting for historical patterns and unique aspects of the coronavirus economy; our approach and results are described in detail in Petrosky-Nadeau and Valletta (2020). Our analysis suggests that returning to pre-outbreak unemployment levels by sometime in 2021 would require a significantly more rapid pace of hiring than during any past economic recovery.

Initial wave of job losses and unemployment

Even before the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released April employment and unemployment numbers on May 8, the unprecedented scale of job losses due to coronavirus containment measures was clear. About 25 million new unemployment insurance (UI) claims were filed between mid-March, when U.S. containment measures started to spread widely and the BLS monthly survey was conducted, and mid-April when the next month’s BLS survey was conducted. During periods of intensive job loss, weekly reports on new UI claims provide a good measure of job losses because most laid-off workers are eligible for UI benefits. However, the current massive scale of new claims has swamped state UI agencies and likely delayed processing of many claims. As such, the recent surge should be interpreted as a loose lower-bound estimate of initial job losses.

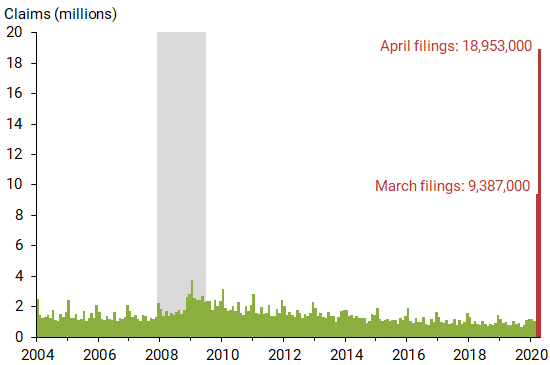

A comparison with the Great Recession of 2007-09 starkly illustrates the severity of the current situation (Figure 1). Initial UI claims during the first month of the COVID-19 crisis were about 10 times larger than claims during the worst periods of the Great Recession.

Figure 1 Monthly initial unemployment insurance claims

Note: Data from the U.S. Department of Labor, not seasonally adjusted (last two data points rounded to nearest thousand; April data through May 2). Gray bar indicates NBER recession dates.

These initial job losses, combined with a likely pronounced reduction in hiring activity, imply a sharp increase in the unemployment rate. Before the April BLS report was released, we projected that the unemployment rate was likely to rise nearly 15 percentage points, from 4.4% in March to 19.0% in April.

Other recent projections of the April unemployment rate span a very wide range (Faria-e-Castro 2020, Wolfers 2020, Coibion, Gorodnichenko, and Weber 2020, and Bick and Blandin 2020). The wide range partly reflects the challenge of measuring unemployment when shelter-in-place restrictions prevent active job search in much of the country. This is evident in the estimates by Coibion et al. (2020) and Bick and Blandin (2020), which differed substantially despite their reliance on careful surveys designed to approximate the official BLS approach.

The official April employment report released on May 8 showed that unemployment rose to 14.7%, a huge increase but below our projection. However, the report also noted a large increase in the number of workers on unpaid absences, likely reflecting virus-related business closures. Counting these workers as unemployed would push the unemployment rate much closer to our 19% projection. We therefore have not modified our prior projections.

Unemployment projections based on labor market flows

Our approach to projecting the unemployment rate relies on the monthly flows between unemployment, employment, and out of the labor force (nonparticipation), similar to Şahin and Patterson (2012). In particular, the monthly change in the unemployment rate reflects the difference between the number who enter unemployment (inflows) and the number who exit unemployment (outflows), with employment and nonparticipation as possible initial or subsequent status. This framework accounts for the key determinants of pandemic-related unemployment, with initial UI claims (inflows through job loss) and depressed hiring (outflows) determining the initial spike in unemployment. Using this approach, we explore different scenarios for unemployment through the end of 2021. For all scenarios, we assume that job losses are most severe in April (about 25 million), then ease substantially in May (7.8 million) and June (2.6 million), before returning to their historical trend in July (1.4 million).

The path of the unemployment rate afterward depends on unemployment outflows, primarily reflected in the pace of hiring among the pool of unemployed individuals. Tremendous uncertainty surrounds the timing and strength of the hiring surge as the economy recovers. If the virus is contained quickly and the economic recovery is vigorous, hiring could rapidly resume, particularly if many businesses and workers have maintained their connections. However, hiring could be slow if virus outbreaks or continued containment measures make employers hesitant based on low demand for their products. We therefore explore a range of hiring scenarios over the coming months.

The first scenario, “historical outflow dynamics,” assumes that the pace of hiring corresponds statistically to the typical recovery from past recessions. Because hiring tends to bounce back slowly following recessions, and given the severity of the current downturn, this scenario is relatively adverse.

Our second scenario, “hiring bounce,” incorporates very strong hiring activity following an assumed end of COVID-19 restrictions in July 2020. This scenario provides a baseline for assessing the pace of hiring required to reverse the initial labor market shock. It assumes a return to pre-outbreak hiring rates by the end of the third quarter of 2020. However, the pace of hiring implied by this scenario is extremely high by historical standards given the vast pool of unemployed individuals. In particular, this scenario requires around 9 million hires from unemployment per month during the third quarter, nearly four times faster than the most robust hiring rate during the recovery from the Great Recession.

Our third scenario, “GDP/hiring forecast,” bases hiring projections on the historical relationship between GDP growth and overall exit rates from unemployment to employment or nonparticipation. This requires a GDP forecast. We rely on a recent San Francisco Fed forecast of GDP growth for 2020-21, specifically the more favorable of two alternatives discussed in qualitative terms in Leduc (2020). It assumes that growth bounces back in the second half of this year and continues at a strong pace next year.

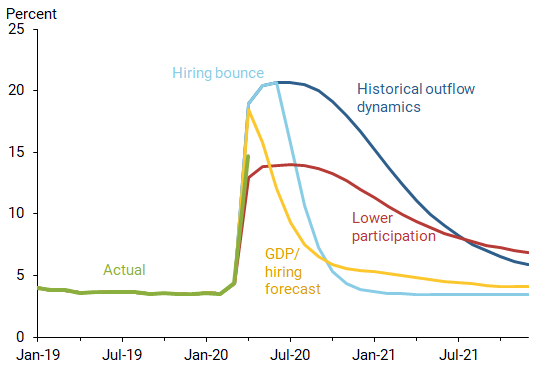

Figure 2 shows the unemployment paths for these scenarios. In the historical outflow dynamics scenario (dark blue line), unemployment quickly peaks around 20% and then stays in double digits through early 2021. By contrast, the hiring bounce scenario (light blue line) reflects a stronger recovery in hiring activity, so the unemployment rate drops much more rapidly. At the end of 2020 most of the job losses have been reversed, and unemployment approaches pre-outbreak levels. For the GDP/hiring forecast scenario (yellow line), unemployment peaks above 18% in the second quarter of 2020, followed by a rapid decline in the third quarter due to underlying limited changes in the hiring rate implied by its historical relationship with GDP growth.

Figure 2 Unemployment rate paths under different scenarios

Incorporating unemployment and nonparticipation ambiguities

As noted earlier, widespread shelter-in-place restrictions may preclude active job searches among laid-off workers, causing them to report themselves as out of the labor force rather than unemployed. Consistent with this, the official labor force participation rate fell 2.5 percentage points to 60.2% in April. We explore the potential impact of these measurement challenges through alternative assumptions about flow rates between different labor market states.

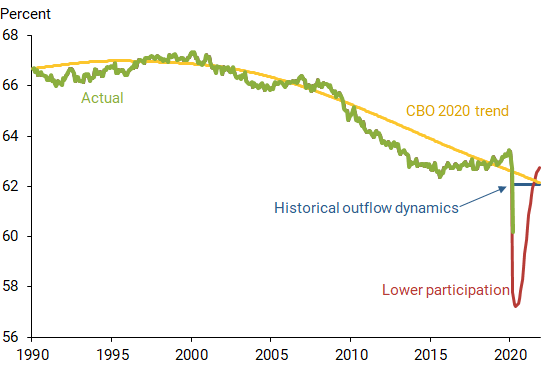

In particular, historical patterns of worker flows from employment to nonparticipation then back into employment during recoveries suggest that nearly half of those workers laid off during the pandemic could leave the labor force upon suffering a job loss. This moderates the initial rise in unemployment, shown as the lower participation scenario (red line) in Figure 2. As individuals return to the labor market during the recovery, lifting the labor force participation rate back toward its previous trend, the pace of return to a pre-outbreak unemployment rate is also muted. In fact, the historical outflow dynamics and lower participation scenarios converge at 8% unemployment in mid-2021. However, these two scenarios imply vastly different trajectories for the labor force participation rate. Figure 3 shows the paths for these scenarios over an extended time frame relative to the trend projected by the Congressional Budget Office (2020).

Figure 3 Labor force participation rate under different scenarios

Conclusions: An uncertain road to recovery

The COVID-19 pandemic has created tremendous labor market disruptions and profound hardship throughout the United States and the world. This is partly reflected in the sudden unprecedented increase in the U.S. unemployment rate in April, the first month for which the full effects of coronavirus containment measures are evident. To get a handle on the severity of the labor market disruption, we assess possible paths for unemployment through the end of 2021. Tremendous uncertainty surrounds unemployment projections over the next few years, so we do not claim that any specific scenario qualifies as “likely.” On the pessimistic side, absent a historically unprecedented burst of hiring, the unemployment rate could remain in double digits through 2021. From a more optimistic perspective, if shutdowns are lifted quickly and employers capitalize on the large pool of available workers by ramping up hiring, the unemployment rate could be back down near its pre-outbreak level by mid-2021.

Uncertainty about the path of the unemployment rate also reflects measurement challenges arising from the ambiguous labor force status of laid-off workers whose active job search is limited by shelter-in-place measures. This may temper the official unemployment rate, but at the expense of a lower labor force participation rate, which is an alternative indicator of labor market dislocation and hardship. Given the implied uncertainty about the measurement of future labor market conditions, it is imperative to closely monitor a wide range of indicators to assess how the U.S. labor market is evolving in response to the COVID-19 shock.

Nicolas Petrosky-Nadeau is a vice president in the Economic Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Robert G. Valletta is a senior vice president in the Economic Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Bick, Alexander, and Adam Blandin. 2020. “Real Time Labor Market Estimates during the 2020 Coronavirus Outbreak.” Manuscript, Arizona State University, April 15.

Coibion, Olivier, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, and Michael Weber. 2020. “Labor Markets During the COVID-19 Crisis: A Preliminary View.” BFI Working Paper, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics, University of Chicago, April 13.

Congressional Budget Office. 2020. “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2020 to 2030.” Report 56020, January 28.

Faria-e-Castro, Miguel. 2020. “Back-of-the-Envelope Estimates of Next Quarter’s Unemployment Rate.” On the Economy, FRB St. Louis blog, March 24.

Leduc, Sylvain. 2020. “FedViews.” FRB San Francisco, April 6.

Petrosky-Nadeau, Nicolas, and Robert G. Valletta. 2020. “Unemployment Paths in a Pandemic Economy.” FRB San Francisco Working Paper 2020-18, May.

Şahin, Ayşegül, and Christina Patterson. 2012. “The Bathtub Model of Unemployment: The Importance of Labor Market Flow Dynamics.” Liberty Street Economics, FRB New York blog, March 28.

Wolfers, Justin. 2020. “The Unemployment Rate Is Probably Around 13%.” New York Times (The Upshot), April 16.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to [email protected]

COVID crisis to push global unemployment over 200 million mark in 2022

Facebook Twitter Print Email

The economic crisis caused by the COVID pandemic is expected to contribute to global unemployment of more than 200 million people next year, with women and youth workers worst-hit, UN labour experts said on Wednesday.

The International Labour Organization ( ILO ) also maintained in a new report that although the world’s nations “will emerge” from the ongoing health crisis, “five years of progress towards the eradication of working poverty have been undone” nonetheless.

The labour market crisis created by the #COVID19 pandemic is far from over. Employment growth will be insufficient to make up for the losses suffered until at least 2023. Check out the new ILO WESO Trends report: https://t.co/frEhP1ktgS pic.twitter.com/CeRaO0O0gm International Labour Organization ilo

“We’ve gone backwards, we’ve gone backwards big time,” said ILO Director-General Guy Ryder. “Working poverty is back to 2015 levels; that means that when the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda was set, we’re back to the starting line.”

The worst-affected regions in the first half of 2021 have been Latin America and the Caribbean, Europe and Central Asia, all victims of uneven recovery.

They’ve seen estimated working-hour losses exceed eight per cent in the first quarter and six per cent in the second quarter, far higher than the global average (of 4.8 and 4.4 per cent respectively).

Women’s roles questioned

Women have been hit “disproportionately” by the crisis, seeing a five per cent employment fall in 2020, compared to 3.9 per cent for men.

“A greater proportion of women also fell out of the labour market, becoming inactive,” ILO said, noting that “additional domestic responsibilities” had resulted from lockdowns which risked a “re-traditionalization” of gender roles.

Youth employment has also continued to suffer the economic downturn, falling 8.7 per cent in 2020, compared with 3.7 per cent for adults.

The most pronounced fall has been in middle-income countries where the consequences of this delay and disruption to the early labour market experience of young people “could last for years”, ILO warned.

$3.20 a day

Pandemic-related disruption has also brought “catastrophic consequences” for the world’s two billion informal sector workers.

Compared to 2019, an additional 108 million workers worldwide are now categorized as “poor” or “extremely poor” – meaning that they and their families live on the equivalent of less than $3.20 per person, per day.

“While signs of economic recovery are appearing as vaccine campaigns are ramped up, the recovery is likely to be uneven and fragile,” Mr Ryder said, as ILO unveiled its forecast that global unemployment will reach 205 million people in 2022, up from 187 million in 2019.

The Geneva-based organization also projected a “jobs gap” increase of 75 million in 2021, which is likely to fall to 23 million in 2022 – if the pandemic subsides.

The related drop in working-hours, which takes into account the jobs gap and those working fewer hours, amounts to the equivalent of 100 million full-time jobs in 2021 and 26 million in 2022.

“This shortfall in employment and working hours comes on top of persistently high pre-crisis levels of unemployment, labour underutilization and poor working conditions,” ILO said in World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2021, (WESO Trends) .

The ILO report maintained that although global employment recovery should accelerate in the second half of 2021, it will likely be an uneven recovery.

Unequal vaccine access is to blame, ILO insisted, in addition to the limited capacity of most developing and emerging economies to support the strong fiscal stimulus measures that have characterised the approach of the world’s wealthiest countries to the COVID-induced downturn.

Decent jobs essential

“Without a deliberate effort to accelerate the creation of decent jobs, and support the most vulnerable members of society and the recovery of the hardest-hit economic sectors, the lingering effects of the pandemic could be with us for years in the form of lost human and economic potential and higher poverty and inequality,” said Mr. Ryder. “We need a comprehensive and co-ordinated strategy, based on human-centred policies, and backed by action and funding. There can be no real recovery without a recovery of decent jobs.”

- global economy

Unemployment among young workers during COVID-19

Subscribe to the economic studies bulletin, stephanie aaronson and stephanie aaronson senior associate director, division of research and statistics - federal reserve board francisca alba francisca alba former research analyst - economic studies.

September 10, 2020

- 10 min read

On June 8, the Business Cycle Dating Committee officially declared that the United States entered a recession in February. Young workers are typically hard hit in recessions, and research suggests that entering the labor market during a recession has a negative impact on future earnings and job prospects. In this post we examine the labor market experience of young workers since the onset of the pandemic and provide some thoughts on policy implications.

While the aggregate unemployment rate increased by 11.2 percentage points between February and April of this year (the local peak), unemployment rates among young workers increased by much more. For example, over the same time period, the unemployment rate for those aged 16-19 increased by 20.9 percentage points. The result is that while young people age 16-29 make up less than a quarter of the labor force, they accounted for about a third of the rise in the unemployment rate between February and April of this year. We also find disparities among young workers by education and by race, with Black and Hispanic workers and workers with lower levels of education experiencing larger increases in unemployment rates between February and April compared to white and college-educated workers. Moreover, we find that while between April and July the unemployment rates for young white 1 , and to a lesser extent Hispanic, workers have retraced a good part of their initial rise, the unemployment rate for young Black workers remains particularly elevated and was little changed in June and July.

That young workers have experienced a greater rise in unemployment during the recession is not surprising, as this is typically the case. However, the extent to which young workers are bearing the brunt of the downturn is unusual. This is partly attributable to the fact that, as is typically the case, younger workers were more likely to be laid off in both April and in May 2 , within industries, compared to their older counterparts. Moreover, this pattern has been exacerbated by the fact that, prior to the pandemic, young workers were more likely to work in service industries that were heavily impacted by social distancing policies required to slow the spread of the virus and reductions in consumer spending.

LABOR FORCE STATISTICS BY AGE:

Figure 1 shows the unemployment rate for five groups by age: 16+ (the aggregate unemployment rate widely reported in the media), 16-19, 20-24, and 25-29. As shown, the aggregate unemployment rate rose 11.2 percentage points between February and April (the local peak). Meanwhile, the unemployment rate for the young increased by about 13 percentage points on average, with the largest increases occurring among the youngest workers. Between April and July the unemployment rate for the young decreased by an average of about 7 percentage points while the aggregate unemployment rate decreased by 4.5 percentage points; although, the unemployment rate for young workers in July still remains 7 percentage points higher, on average, than the aggregate.

However, the pandemic unemployment rate has understated the extent to which workers are losing jobs , as more of those who have lost jobs have chosen to drop out of the labor force than is typically the case during a recession. Our analysis suggests that this dynamic has been particularly prevalent among young workers. Figure 2 displays the labor force participation rate for these same age groups. While the aggregate labor force participation rate decreased by 3.2 percentage points between February and April, the labor force participation rate for those between the ages of 16 and 29 dropped by about 6 percentage points on average. Moreover, these declines were much larger proportionally and relative to the rise in the unemployment rate, and they have been more sustained. Since April, the labor force participation rate for those between the ages of 16 and 29 has increased by an average of about 1.5 percentage points, similar to the increase in the aggregate.

LABOR FORCE STATISTICS BY RACE AND BY EDUCATION:

Overall, the young have been hit hard by the recession, but the impact also varies by race/ethnicity and education. Figure 3 shows the unemployment rate since the start of the recession for young white, Black, and Hispanic workers. The unemployment rate rose more for young Black and Hispanic workers between February and April 3 . Between April and July, young white and Hispanic workers started to make up ground, as their unemployment rate declined by an average of about 7 percentage points. However, unemployment rates for young Black workers only declined by about 2 percentage points.

The disparities by education are also stark. These data, which are reported only for those over the age of 25 (by which time educational attainment is largely complete) show that the unemployment rate for those with a high school degree or less and for those with some college education rose by more than twice as much as for those with a college degree or more between February and April. Interestingly, since then, the unemployment rate for those with less than a college degree have come down—likely as the industries in which they work have recovered—while the unemployment rate for those with a college degree has been fairly flat. That said, the unemployment rates for these lower skilled workers, especially those with a high school degree or less, remain higher than those with a college degree or more.

RECENT UNEMPLOYMENT BY INDUSTRY:

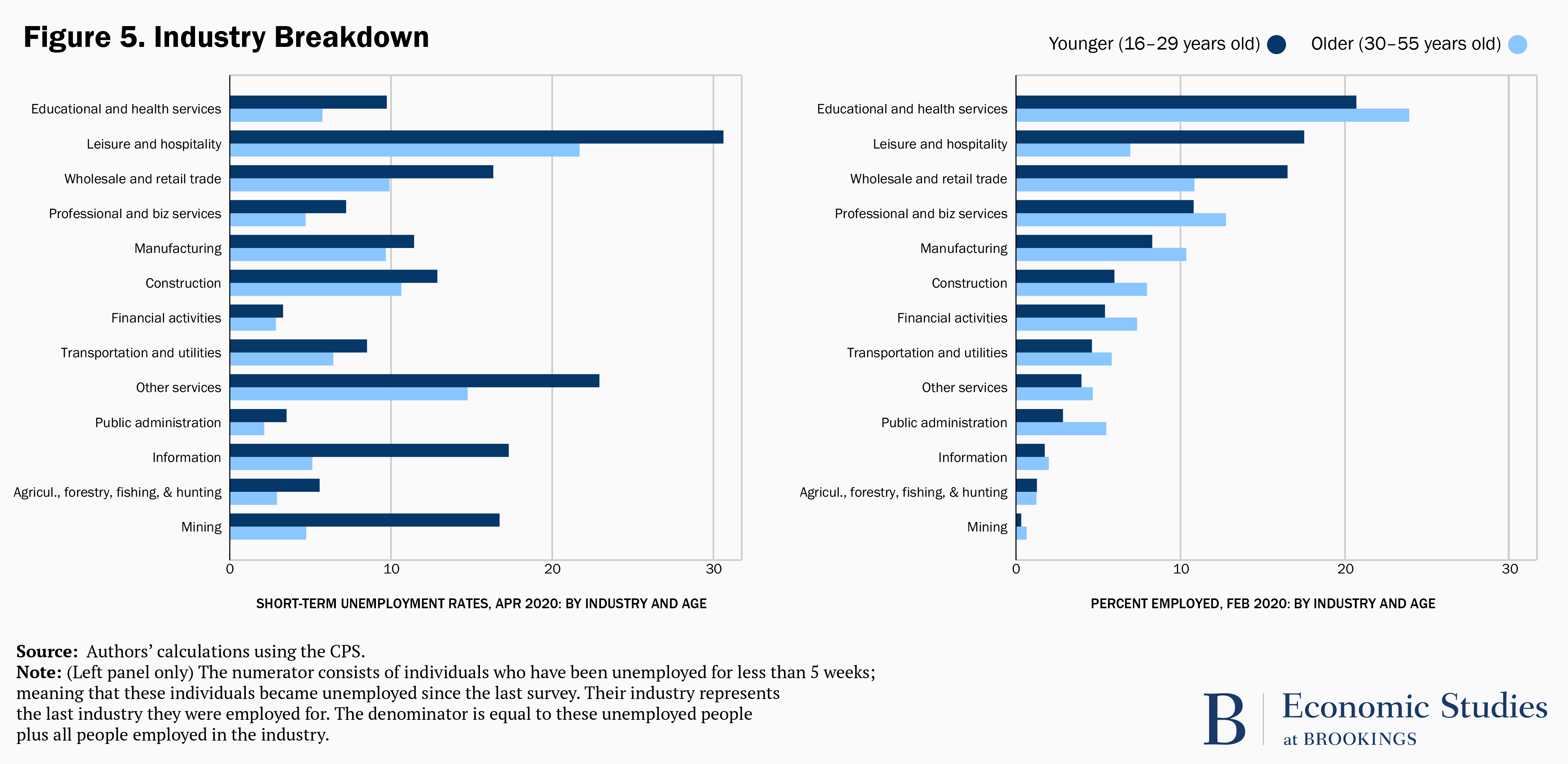

These results raise the question of why young workers have lost their jobs at much higher rates. The left panel of Figure 5 shows that between March and April, young workers were more likely to be laid off than older age workers in almost every industry, although in a few cases the differences are quite small (and the same dynamic is true between April and May). The differences are especially pronounced in mining, information, wholesale and retail trade, information, education and health services, leisure and hospitality, and other services sectors 4 . These dynamics are similar to those typically observed during a recession. Employers may be more likely to layoff young workers for a variety of reasons, which depend on the culture of the industry, the nature of the work, and the cost structure. For instance, firms may have policies of firing the most recent hires first, as a way to retain the morale and support of long-time workers. In industries that require significant firm-specific knowledge, young workers with lower tenure would likely have less of this, which would make separating them from the firm less of a loss.

However, the pandemic appears to have introduced an additional economic challenge for young workers. As the right panel of Figure 5 shows, in February, prior to the significant decline in economic activity due to the pandemic, young workers were significantly more likely to be working in many of the hardest hit industries, including leisure and hospitality (17.5 percent) and wholesale and retail trade (16.5 percent) compared to their older counterparts (7 percent and 10.8 percent respectively). These industries are not especially sensitive to economic downturns , so this is a dynamic that is unique to the pandemic and is different from a typical recession.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS & DISCUSSION:

In this post we provide evidence that the labor market prospects of young workers have been particularly hard hit by the current economic downturn, and this is especially true for young Black and Hispanic workers and young workers with lower levels of education. Our findings are consistent with research done by our colleagues in the Metropolitan Policy Program who find that the most vulnerable workers are disproportionately young and have less formal education .

The particular economic vulnerability of young workers right now points to the need for policy support. To some extent, young workers benefit from the same policies that that aid the wider public. For example, as young workers tend to spend a higher proportion of their income on rent 5 ,they would disproportionately benefit from an extension of the federal eviction moratorium in the next relief package. However, policymakers should also take into consideration the special circumstances of young workers. For instance, simply extending federal unemployment insurance benefits will not provide enough financial support for young workers. Congress must also continue to waive work history requirements , since many young workers have short work histories or are just entering the labor force and would therefore be ineligible for UI benefits otherwise. Similarly, a portion of young college graduates did not receive stimulus payments 6 —a small but significant omission that policymakers should take into account, if they do another round of payments to households.

But the problems young workers currently face go beyond an immediate economic need. The jobs young workers hold are important stepping-stones in their careers , allowing them to learn valuable work skills and make connections, which can improve their future employment prospects. To the extent that industries such as retail trade, and leisure and hospitality undergo significant transformations in response to the pandemic, some young workers might find that traditional pathways into the labor market are unavailable.

For those who get a college degree, research suggests that graduating during a recession can leave a lasting imprint. For instance, nearly 1/3 rd of college graduates who entered the labor market during the Great Recession ended up in jobs that did not require a college education. Although this is often a temporary phenomenon, it can have long-lasting implications. For example, research shows that college graduates who have the lowest predicted earnings (based on college and major) suffer the most during a typical recession: experiencing a loss of 8 percent of cumulative earnings in their first 10 years.

All this means that, as we look beyond the pandemic, young workers will need added support to make sure that they are integrated into the labor force.

Becca Portman contributed to the graphics/data visualization for this blog.

Related Content

Wendy Edelberg, Paige Shevlin

February 4, 2021

Rebecca M. Blank

April 4, 2008

Stephanie Aaronson

July 2, 2020

- We define white/Black as those whose race is white/black and whose ethnicity is not Hispanic. We define Hispanic as any race with Hispanic ethnicity.

- Although we don’t display a figure showing these results. We did run the same analysis for May; the results were similar to April.

- Note that the unemployment rate for young Black workers was increasing before February of 2020. This increase in the Black unemployment rate is unlike the other two groups whose unemployment rates hit a low in February of 2020.

- We calculate the short-term unemployment rate from the Current Population Survey by counting the number of people in an age group and in an industry who became unemployed since the last survey and divide this number by the total amount of people employed and unemployed in that age group and industry. An unemployed person’s industry is the industry in which they were last employed.

- Note that the young group showing up as especially rent-burdened in the linked ACS table includes a range of different household types with differing financial circumstances.

- This group consists of students whose parents claimed them as dependent on their 2019 tax returns, but who graduated in December of 2019 and started to look for work right before the downturn.

Labor & Unemployment

Economic Studies

William A. Galston

March 28, 2024

Joseph W. Kane, Fred Dews

Stefanie Stantcheva

March 27, 2024

An official website of the United States government.

Here’s how you know

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- American Rescue Plan

- Coronavirus Resources

- Disability Resources

- Disaster Recovery Assistance

- Equal Employment Opportunity

- Guidance Search

- Health Plans and Benefits

- Registered Apprenticeship

- International Labor Issues

- Labor Relations

- Leave Benefits

- Major Laws of DOL

- Other Benefits

- Retirement Plans, Benefits and Savings

- Spanish-Language Resources

- Termination

- Unemployment Insurance

- Veterans Employment

- Whistleblower Protection

- Workers' Compensation

- Workplace Safety and Health

- Youth & Young Worker Employment

- Breaks and Meal Periods

- Continuation of Health Coverage - COBRA

- FMLA (Family and Medical Leave)

- Full-Time Employment

- Mental Health

- Office of the Secretary (OSEC)

- Administrative Review Board (ARB)

- Benefits Review Board (BRB)

- Bureau of International Labor Affairs (ILAB)

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)

- Employee Benefits Security Administration (EBSA)

- Employees' Compensation Appeals Board (ECAB)

- Employment and Training Administration (ETA)

- Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA)

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)

- Office of Administrative Law Judges (OALJ)

- Office of Congressional & Intergovernmental Affairs (OCIA)

- Office of Disability Employment Policy (ODEP)

- Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP)

- Office of Inspector General (OIG)

- Office of Labor-Management Standards (OLMS)

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Administration and Management (OASAM)

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Policy (OASP)

- Office of the Chief Financial Officer (OCFO)

- Office of the Solicitor (SOL)

- Office of Workers' Compensation Programs (OWCP)

- Ombudsman for the Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program (EEOMBD)

- Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC)

- Veterans' Employment and Training Service (VETS)

- Wage and Hour Division (WHD)

- Women's Bureau (WB)

- Agencies and Programs

- Meet the Secretary of Labor

- Leadership Team

- Budget, Performance and Planning

- Careers at DOL

- Privacy Program

- Recursos en Español

- News Releases

- Economic Data from the Department of Labor

- Email Newsletter

Please note: As of January 20, 2021, information in some news releases may be out of date or not reflect current policies.

News Release

U.S. Department Of Labor Publishes Guidance on Pandemic Unemployment Assistance

WASHINGTON, DC – The U.S. Department of Labor today announced the publication of Unemployment Insurance Program Letter (UIPL) 16-20 providing guidance to states for implementation of the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program. Under PUA, individuals who do not qualify for regular unemployment compensation and are unable to continue working as a result of COVID-19, such as self-employed workers, independent contractors, and gig workers, are eligible for PUA benefits. This provision is contained in Section 2102 of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES) Act enacted on March 27, 2020.

PUA provides up to 39 weeks of benefits to qualifying individuals who are otherwise able to work and available for work within the meaning of applicable state law, except that they are unemployed, partially unemployed, or unable or unavailable to work due to COVID-19 related reasons, as defined in the CARES Act. Benefit payments under PUA are retroactive, for weeks of unemployment, partial employment, or inability to work due to COVID-19 reasons starting on or after January 27, 2020. The CARES Act specifies that PUA benefits cannot be paid for weeks of unemployment ending after December 31, 2020.

Eligibility for PUA includes those individuals not eligible for regular unemployment compensation or extended benefits under state or federal law or pandemic emergency unemployment compensation (PEUC), including those who have exhausted all rights to such benefits. Covered individuals also include self-employed individuals, those seeking part-time employment, and individuals lacking sufficient work history. Depending on state law, covered individuals may also include clergy and those working for religious organizations who are not covered by regular unemployment compensation.

The UIPL also includes guidance to states about protecting unemployment insurance program integrity. The department is actively working with states to provide benefits only to those who qualify for such benefits.

For more information on UIPLs or previous guidance, please visit: https://wdr.doleta.gov/directives/ .

For department resources on COVID-19, please visit: https://www.dol.gov/coronavirus .

For more information about COVID-19, please visit: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html .

The Employment and Training Administration administers federal job training and dislocated worker programs, federal grants to states for public employment service programs, and unemployment insurance benefits. These services are primarily provided through state and local workforce development systems.

The mission of the department is to foster, promote, and develop the welfare of the wage earners, job seekers, and retirees of the United States; improve working conditions; advance opportunities for profitable employment; and assure work-related benefits and rights.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC)

Pandemic unemployment assistance (pua), pandemic emergency unemployment compensation (peuc), states got more flexibility to pay benefits.

- Frequently Asked Questions

The Bottom Line

- Government & Policy

Federal Pandemic Unemployment Programs: How They Worked

These 3 temporary programs provided extra benefits, including $600 more per week

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/jeanfolgerbio-eb94a21d857648f090a7e73797ac0f4f.jpeg)

More than 10 million Americans applied for unemployment benefits in March 2020—some 6.6 million of them in the week ending March 28 alone. In April 2020, the unemployment rate soared to 14.7%, “the highest rate and the largest over-the-month increase in the history of the data (available back to January 1948),” according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “The number of unemployed persons rose by 15.9 million to 23.1 million in April.”

To put that into perspective, the unemployment rate hit 10% just once during the Great Recession of 2008, the last major financial crisis to grip the United States. The numbers were the most dire since the Great Depression .

Millions of out-of-work Americans depended on unemployment insurance (UI) to help cover rent, groceries, and other expenses. Several new programs were created to help alleviate some of the economic pain caused by COVID-19, thanks to a $2 trillion coronavirus emergency stimulus package called the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act that then-President Donald Trump signed into law on March 27, 2020.

The CARES Act expanded unemployment insurance benefits to many workers affected by COVID-19 through three key programs: the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) program, the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program, and the Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) program. Here is a look at these programs and how they helped unemployed Americans affected by coronavirus.

Key Takeaways

- The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act expanded unemployment insurance benefits to many workers affected by COVID-19, the illness caused by coronavirus, through three key programs.

- The Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) program provided an extra $600 weekly benefit on top of your regular unemployment insurance (UI) if you couldn’t work due to COVID-19.

- The Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program expanded UI eligibility to self-employed workers, freelancers, independent contractors, and part-time workers impacted by the coronavirus pandemic.

- The Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) program extended UI benefits for an extra 13 weeks.

- Most states recommended applying for UI benefits online.

The CARES Act established the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) program to boost benefits for out-of-work Americans. Under this new program, eligible people who collected certain unemployment insurance benefits—including regular unemployment compensation—got an extra $600 in federal benefits each week through July 31, 2020. After a series of extensions, the program expired on Sept. 6, 2021. In total, an additional 40 weeks were added to the original 13 weeks of extended benefits.

FPUC was a flat amount given to people who were receiving unemployment insurance, including those who got a partial unemployment benefit check. This program also applied to people who received benefits under the new Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program, which covered freelancers, independent contractors, and gig workers (see below).

Under the CARES Act, states that waived their usual one-week waiting period for benefits were fully reimbursed by the federal government for benefits paid that week, plus any associated administrative expenses.

Applying for Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation

To apply for Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation, people had to file a claim for regular benefits with the UI program in the state where they worked. Depending on the state, they could file a claim in person, online, or over the phone. When they filed a claim, they had to provide their Social Security number, contact information, and details about their former employment.

Under the FPUC program, states administered an extra $600 weekly payment to eligible people who were receiving regular unemployment benefits (including Unemployment Compensation for Federal Employees and Unemployment Compensation for Ex-Servicemembers), as well those collecting benefits from the following programs:

- Extended benefits

- Short-Time Compensation

- Trade Readjustment Allowances

- Disaster Unemployment Assistance

- Payment under the Self-Employment Assistance program

Due to the massive number of people trying to apply for UI benefits, many states’ UI websites crashed or were very slow. Applicants were advised to watch for updates on the program website, and to be aware that many states had indicated they would backdate claims to the date when applicants first became unemployed.

As the program launched, most states were still waiting for guidance from the U.S. Department of Labor to implement the program (and the other two programs as well). As states started to provide the extra payment, eligible people received retroactive payments. The payments dated back to the applicant’s eligibility date or the date when their state signed an agreement to provide the benefits—whichever was later. All states had executed agreements with the U.S. Department of Labor as of March 28, 2020.

FPUC, PUA, and PEUC were fully federally funded programs. States also received additional administrative funds to operate these programs.

The Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program temporarily extended unemployment benefits to eligible self-employed workers, including:

- Freelancers and independent contractors

- Workers seeking part-time work

- Workers who don’t have a long-enough work history to qualify for state unemployment insurance benefits

- Workers who otherwise wouldn’t qualify for benefits under state or federal law

The program expired on Sept. 6, 2021, along with other employment-related programs that provided COVID relief.

Pandemic Unemployment Assistance Eligibility

To be eligible for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance, applicants had to provide self-certification that they were able to work and available for work, and that they were unemployed, partially employed, or unable or unavailable to work due to one of these COVID-19-related situations:

- They have been diagnosed with COVID-19 or have symptoms of it and are trying to get diagnosed

- A member of their household has been diagnosed with COVID-19

- They are providing care for someone diagnosed with COVID-19

- They are providing care for a child or other household member who can’t go to school or work because it’s closed due to COVID-19

- They are quarantined or have been advised by a healthcare provider to self-quarantine

- They were scheduled to start a job and don’t have a job or can’t reach the job due to COVID-19

- They have become the primary earner for a household because the head of household has died as a direct result of COVID-19

- They had to quit their job as a direct result of COVID-19

- Their place of employment has closed as a direct result of COVID-19

- They meet other criteria set forth by the Secretary of Labor

Workers were not eligible for PUA benefits if they could telework with pay. Also, workers had to be authorized to work to be eligible for PUA, so undocumented workers did not qualify.

Benefit amounts were calculated based on previous earnings, using a formula from the Disaster Unemployment Assistance program under the Stafford Act. PUA had a minimum benefit that was equal to 50% of the state’s average weekly UI benefit (about $190 per week).

Since it could take time for states to be ready to process claims for freelancers, gig workers, and independent contractors, workers were eligible for retroactive benefits and could receive benefits for up to 39 weeks, including any weeks when the worker received regular unemployment insurance.

The program started on Jan. 27, 2020, and was set to expire on Dec. 31, 2020, under the CARES Act. It was extended until March 14, 2021, when the Consolidated Appropriations Act was signed into law on Dec. 27, 2020.

PUA was given new life again, adding 29 more weeks to the program after the Biden administration passed the American Rescue Plan Act , a $1.9 trillion stimulus package, in March 2021. PUA officially expired on Sept. 6, 2021, after a total of 79 weeks.

The Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) program allowed people who had exhausted their regular unemployment benefits to receive up to 13 additional weeks of benefits.

States had to offer flexibility to applicants in meeting PEUC eligibility requirements related to “actively seeking work” if an applicant’s ability to find work was affected by COVID-19. The bill specifies that “a State shall provide flexibility in meeting such [work search] requirements in case of individuals unable to search for work because of COVID-19, including because of illness, quarantine, or movement restriction.”

After a series of extensions, the program also expired on Sept. 6, 2021. In total, an additional 40 weeks were added to the original 13 weeks of extended benefits.

A “non-reduction” rule in the CARES Act prevents states from doing anything to decrease the maximum number of weeks of unemployment insurance or the weekly benefits available under state law as of Jan. 1, 2020.

Federal law allowed considerable flexibility for states to amend their laws to provide unemployment insurance benefits in several COVID-19-related situations. States could, for example, pay benefits when:

- An employer temporarily closes due to COVID-19, preventing employees from going to work

- A person is quarantined and anticipates going back to work after the quarantine is over

- A person stops work due to a risk of COVID-19 exposure or infection, to care for a family member, or to homeschool their children

Under federal law, an employee didn’t have to quit to receive benefits due to COVID-19.

To find out the rules in their state, applicants should check with their state’s unemployment insurance program .

Which pandemic unemployment program covered freelancers and part-time workers?

The Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program covered these categories. Workers had to fit into one of 10 COVID-19-affected categories.

Could people whose workplaces closed temporarily for COVID get unemployment compensation?

The laws allowed states to include these groups in unemployment compensation. The affected workers didn’t have to lose their jobs to be covered.

When did these special programs end?

All three expired on Sept. 6, 2021.

Three special unemployment compensation programs helped workers survive the job loss and financial strain of the coronavirus pandemic in the United States from the end of March 2020 until early September 2021. They included unique features such as covering self-employed workers, freelancers, independent contractors, and part-time workers—and those who left their jobs to care for people affected by COVID-19 or children sent home when schools closed due to the pandemic. They also provided additional payments and a longer time frame for unemployment.

The Washington Post. “ Over 10 Million Americans Applied for Unemployment Benefits in March as Economy Collapsed .”

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “ Unemployment Rises to Record High 14.7 Percent in April 2020 .”

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “ Graphics for Economic News Releases: Civilian Unemployment Rate .”

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “ Labor Force, Employment, and Unemployment, 1929–39: Estimating Methods ,” Page 2, Table 1.

U.S. Department of the Treasury, Office of Inspector General. “ CARES Act .”

Congress.gov, U.S. Congress. “ H.R.748—CARES Act; Summary .”

U.S. Department of Labor. “ U.S. Department of Labor Announces New CARES Act Guidance on Unemployment Insurance for States in Response to COVID-19 Crisis .”

New York State Department of Labor. “ Expiration of Federal Unemployment and Pandemic Benefits .”

U.S. Department of Labor. “ U.S. Department of Labor Announces New Guidance to States on Unemployment Insurance Programs .”

U.S. Department of Labor Blog. “ New COVID-19 Unemployment Benefits: Answering Common Questions .”

U.S. Department of Labor. “ U.S. Department of Labor Publishes Guidance on Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation .”

U.S. Department of Labor. “ Advisory: Unemployment Insurance Program Letter No. 14-20 ,” Pages 3–5 and 8.

U.S. Department of Labor. “ U.S. Department of Labor Issues New Guidance to States on Implementing American Rescue Plan Act Unemployment Insurance Provisions .”

Congress.gov, U.S. Congress. “ H.R.748—CARES Act: Text .”

National Employment Law Project. “ Unemployment Insurance Provisions in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act .”

Congress.gov, U.S. Congress. “ H.R.1319—American Rescue Plan Act of 2021: Text .”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-1203771991-cc630b566ec647b4ad6edf460bc54ce5.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

New COVID-19 Unemployment Benefits: Answering Common Questions

In March 2020, the president signed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act, which provided Americans with new and expanded unemployment insurance (UI) benefits if they’re out of work for reasons related to the pandemic. These benefits were recently updated and extended when the Continued Assistance for Unemployed Workers Act of 2020 (Continued Assistance Act) was signed into law by President Trump on Dec. 27, 2020. The Continued Assistance Act also included a one-time $600 stimulus payment for qualified individuals; however, that payment is not an unemployment benefit and is administered by the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

Here are answers to questions about the unemployment insurance benefits in the new law.

How does the Continued Assistance Act affect unemployment benefits?

* minus the weeks you received regular unemployment benefits and extended benefits

If you are receiving unemployment benefits [state or federal regular unemployment compensation, including Unemployment Compensation for Federal Employees (UCFE), Unemployment Compensation for Ex-Servicemembers (UCX), PEUC, PUA, Extended Benefits (EB), Short-Time Compensation (STC), Trade Readjustment Allowances (TRA), Disaster Unemployment Assistance (DUA), or the Self-Employment Assistance Program (SEA)], you will receive an additional $300 per week as a supplemental amount to unemployment benefits for weeks of unemployment ending by March 14, 2021.

PUA still applies to self-employed workers, gig workers, independent contractors, and other people who don’t usually qualify for unemployment insurance. The PUA program is extended to March 14, 2021. If you receive PUA during the week ending March 14, 2021, have not exhausted all rights to PUA, and are otherwise eligible for PUA benefits, there is a transition period through weeks of unemployment that begin no later than April 5, 2021, for which PUA benefits are payable. No PUA is payable for any week of unemployment beginning after April 5, 2021. In addition, the maximum PUA eligibility has been extended from 39 weeks to 50 weeks (minus the weeks the individual received regular unemployment benefits and Extended Benefits).

Similarly, the PEUC program is extended to March 14, 2021. If you receive PEUC during the week ending March 14, 2021, have not exhausted all rights to PEUC, and are otherwise eligible for PEUC, there is a transition period through weeks of unemployment that begin no later than April 5, 2021, for which PEUC benefits are payable. No PEUC is payable for any week of unemployment beginning after April 5, 2021. In addition, the length of time an eligible individual can receive PEUC has been extended from 13 weeks to 24 weeks.

Note that individuals in states where the Extended Benefits program is available may receive up to 13 weeks of benefits — or up to 20 weeks of benefits if the state is in a high unemployment period — through the EB program. Contact your state unemployment insurance agency for more information .

How many weeks of unemployment insurance benefits am I entitled to?

The amount and duration of benefits you can receive also depends on the law in the state where you last worked . The state will determine your eligibility for any additional federal benefits. Contact your state unemployment insurance agency for more information .

Do I qualify for the additional $300 in federal benefits?

The additional $300/week in Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation is available to claimants receiving unemployment benefits under the state or federal regular unemployment compensation programs (UCFE, UCX, PEUC, PUA, EB, STC, TRA, DUA, and SEA ). The funds are available for any weeks of unemployment beginning after Dec. 26, 2020, and ending on or before March 14, 2021. You don’t need to apply separately to receive this supplemental amount.

Are self-employed, independent contractor and gig workers eligible for assistance?

Self-employed workers, independent contractors, gig economy workers, and people who have not worked long enough to qualify for the other types of unemployment assistance may still qualify for PUA if they are otherwise able to work and available for work within the meaning of the applicable state law and certify that they are unemployed, partially unemployed or unable or unavailable to work for one of the following COVID-19 reasons:

- You have been diagnosed with COVID-19, or have symptoms, and are seeking a medical diagnosis.

- A member of your household has been diagnosed with COVID-19.

- You are caring for a family member of a member of your household who has been diagnosed with COVID-19.

- A child or other person in your household for whom you have primary caregiving responsibility is unable to attend school or another facility that is closed as a direct result of COVID-19 and the school or facility care is required for you to work.

- You cannot reach your job because of a quarantine imposed as a direct result of the COVID-19 public health emergency.

- You cannot reach your job because you have been advised by a healthcare provider to self-quarantine due to concerns related to COVID-19.

- You were scheduled to start a new job and do not have a job or are unable to reach the job as a direct result of the COVID-19 public health emergency.

- You’ve become the main source of income for a household because the head of the household has died as a direct result of COVID-19.

- You had to quit your job as a direct result of COVID-19.

- Your workplace is closed as a direct result of COVID-19.

- You are self-employed, have reportable income and have experienced a significant diminution of services because of the COVID-19 public health emergency.

States must first verify that these workers are not eligible for regular unemployment compensation or Extended Benefits under state or federal law or PEUC. Beginning on Jan. 26, 2021, states must also implement stricter identification verification measures for PUA applicants. Applicants will also be required to provide documentation substantiating employment or self-employment.

What can I do if somebody filed a fraudulent claim using my information?

Contact our Office of Inspector General to report claimant or employer fraud involving unemployment insurance:

Online : www.oig.dol.gov/hotline.htm

Phone : 1-800-347-3756

You can also contact the fraud office for the state where the claim was filed. Check this list to find contact information for your state unemployment insurance fraud office .

Can you help if my state office won’t answer the phone or hasn’t sent my money?

We recognize that a high volume of pandemic-related calls has overwhelmed some states’ call centers and websites, leading to delays. However, the federal government has no authority to intervene in individual claims for benefits, so you should contact the state unemployment insurance office handling your claim. You can locate state office information at www.dol.gov/uicontacts .

Find more information about unemployment insurance generally and more information about unemployment insurance relief during the COVID-19 outbreak , including contact information for your state unemployment insurance office.

Jim Garner is the acting administrator of the Office of Unemployment Insurance in the U.S. Department of Labor’s Employment and Training Administration .

- Unemployment Insurance

- Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation

- Pandemic Unemployment Assistance

- Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation

- Continued Assistance Act

- Employment and Training Administration (ETA)

SHARE THIS:

5 charts that explain how COVID-19 has affected employment in OECD countries

"...the pandemic has presented governments with a chance to address all of these issues as vaccination programmes bring the hope of recovery." Image: UNSPLASH/Gabriella Clare Marino

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Annabel Walker

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Future of Work is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, future of work.

Listen to the article

- Coronavirus and the measures to contain it caused a severe global economic recession.

- Those with less formal education, on low pay, women and the young were more likely to lose their jobs.

- Governments have committed exceptional resources to recovery, offering an opportunity to build a more equitable jobs market.

Covid-19 has had a shattering effect on the world of work and in many countries it continues to do so.

Measures put in place to contain the virus have caused severe economic pain. Lockdowns closed businesses, cost jobs and required billions to isolate at home, away from extended family and friends.

Inequalities in society that predated the pandemic worsened. The gender pay gap has widened , youth unemployment has increased and many employed on insecure contracts have lost their jobs.

But the pandemic has presented governments with a chance to address all of these issues as vaccination programmes bring the hope of recovery. Instead of returning to the life we had before the pandemic, some policy makers think now’s the time to invest in jobs that offer security, better prospects and higher pay.

When will jobs be back?

The pandemic prompted governments and central banks to provide unprecedented stimulus to protect jobs; the OECD estimates that 21 million jobs were saved in this way. But what happens when that safety net is removed?

The OECD's 2021 Employment Outlook suggests that even across the world’s richest countries, the bounce back to pre-pandemic employment rates will be patchy. Israel, for instance, isn’t expected to see jobs return to 2019 levels until 2025, four years after Australia.

Long-term unemployed struggle to find work

The downturn in many OECD economies has resulted in more job seekers being out of work for longer than they might have expected before the pandemic.

That may pose problems for future employment because the longer a person is out of work the harder it is for them to find a job.

Unemployment is higher than in 2019

While unemployment has begun to lessen, it has yet to fall to pre-pandemic levels. Additionally, job losses have been disproportionately higher among the young, those on lower pay and workers in industries most troubled by shutdowns, such as hospitality. These are also traditionally roles with the least protections.

The youth employment gap is growing

The employment gap between people aged 15-to-24 and older workers has been widening for decades, but the past year has seen the chasm deepen. A greater proportion of jobs were lost among young people, who have also been less able to find work.

Youth unemployment and underemployment (when people would like to work for more hours than they do) particularly affects women, those from disadvantaged backgrounds and minority groups. Left unchecked, this could aggravate social exclusion, potentially fuelling unrest, the OECD warns.

Have you read?

6 ways to ensure a fair and inclusive economic recovery from covid-19, how coronavirus has hit employment in g7 economies, when will the covid-19 pandemic end experts explain.

Not everyone can work remotely

Many people took the opportunity to work from home during pandemic lockdowns, swapping an early commute for another hour in bed. Others, especially in lower-paid and labour-intensive industries didn’t have that choice and had to go to work as usual. This affected the less educated to a greater degree than college graduates.

A different future

The economic hit to the global economy from coronavirus was worse even than the 2008 recession, with the OECD estimating that more than 110 million jobs have been lost.

Governments are moving from their initial crisis response into long-term recovery plans. This year support for people seeking work increased in 53% of countries.

However International Monetary Fund (IMF) data indicates economic recovery is affected by the country you call home. Next year’s economic forecast is revised up for developed nations with vaccines, while developing economies, especially in Asia have been downgraded.

The first global pandemic in more than 100 years, COVID-19 has spread throughout the world at an unprecedented speed. At the time of writing, 4.5 million cases have been confirmed and more than 300,000 people have died due to the virus.

As countries seek to recover, some of the more long-term economic, business, environmental, societal and technological challenges and opportunities are just beginning to become visible.

To help all stakeholders – communities, governments, businesses and individuals understand the emerging risks and follow-on effects generated by the impact of the coronavirus pandemic, the World Economic Forum, in collaboration with Marsh and McLennan and Zurich Insurance Group, has launched its COVID-19 Risks Outlook: A Preliminary Mapping and its Implications - a companion for decision-makers, building on the Forum’s annual Global Risks Report.

Companies are invited to join the Forum’s work to help manage the identified emerging risks of COVID-19 across industries to shape a better future. Read the full COVID-19 Risks Outlook: A Preliminary Mapping and its Implications report here , and our impact story with further information.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is asking policy makers to take the long view. In its Global Call to Action the ILO argues jobs recovery plans need to be inclusive, with specific support to help disadvantaged groups. For the recovery to last, policy makers must include excellent training programmes with a focus on investing in well-paid, quality jobs.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Future of Work .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Green job vacancies are on the rise – but workers with green skills are in short supply

Andrea Willige

February 29, 2024

Digital Cooperation Organization - Deemah Al Yahya

Why clear job descriptions matter for gender equality

Kara Baskin

February 22, 2024

Improve staff well-being and your workplace will run better, says this CEO

Explainer: What is a recession?

Stephen Hall and Rebecca Geldard

February 19, 2024

Is your organization ignoring workplace bullying? Here's why it matters

Jason Walker and Deborah Circo

February 12, 2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Analysis of the COVID-19 impacts on employment and unemployment across the multi-dimensional social disadvantaged areas

This is the study of economic impacts in the context of social disadvantage. It specifically considers economic conditions in regions with pre-existing inequalities and examines labor market outcomes in already socially vulnerable areas. The economic outcomes remain relatively unexplored by the studies on the COVID-19 impacts. To fill the gap, we study the relationship between the pandemic-caused economic recession and vulnerable communities in the unprecedented times. More marginalized regions may have broader economic damages related to the pandemic. First, based on a literature review, we delineate areas with high social disadvantage. These areas have multiple factors associated with various dimensions of vulnerability which existed pre-COVID-19. We term these places “ multi-dimensional social disadvantaged areas ”. Second, we compare employment and unemployment rates between areas with high and low disadvantage. We integrate geospatial science with the exploration of social factors associated with disadvantage across counties in Tennessee which is part of coronavirus “red zone” states of the US southern Sunbelt region. We disagree with a misleading label of COVID-19 as the “great equalizer”. During COVID-19, marginalized regions experience disproportionate economic impacts. The negative effect of social disadvantage on pandemic-caused economic outcomes is supported by several lines of evidence. We find that both urban and rural areas may be vulnerable to the broad social and economic damages. The study contributes to current research on economic impacts of the COVID-19 outbreak and social distributions of economic vulnerability. The results can help inform post-COVID recovery interventions strategies to reduce COVID-19-related economic vulnerability burdens.

1. Introduction: social disadvantage

Pandemics create severe disruptions to a functioning society. The economic and social disruptions intersect in complex ways and affect physical and mental health and illness ( Wu et al, 2020 ). Additionally, loss of jobs, wages, housing, or health insurance, as well as disruption to health care, hospital avoidance, postponement of planned medical treatment increase mortality, e.g., premature deaths ( Kiang et al., 2020 ; Petterson et al., 2020 ). The COVID-19, misleadingly labelled the “great equalizer” implies everyone is equally vulnerable to the virus, and that the economic activity of almost everyone is similarly impacted regardless of social status ( Jones & Jones, 2020 ). We set out to answer whether economic vulnerability is equally distributed during the COVID-19-caused economic recession or whether is it based on structural disadvantages? Is the social distribution of economic vulnerability magnified in regions with pre-existing social disparities, thus, creating new forms of inequalities? Knowledge of what areas experience the greater economic burden will help identify the most economically vulnerable communities relevant to post-COVID recovery interventions ( Qian and Fan, 2020 ).

Current studies on the impacts of COVID-19 largely focus on medical aspects including the COVID diagnosis and treatment ( Cai et al., 2020 ; Kass et al., 2020 ; O’Hearn et al., 2021 ; Price-Haywood et al., 2020 ). Non-medical urban research primarily concentrates on the impact of COVID on cities by studying factors related to environmental quality including meteorological parameters, and air and water quality ( Sharifi and Khavarian-Garmsir, 2020 ). COVID-related socio-economic impacts on cities are relatively less well studied, especially during the later stages of the recession.

Many pre-pandemic disparities unfold during COVID-19. To illustrate, residents of Black and Latino communities are suffering disproportionately higher unemployment rates, greater mortality due to the COVID-19 ( Thebault, Tran, & Williams, 2020 ; Wade, 2020 ), higher hospitalizations ( O’Hearn et al., 2021 ) and financial troubles. In contrast, some attributes make persons and communities more resilient. In China’s context, these include higher worker education and family economic status, membership in Communist Party, state-sector employment, and other traditional markers. These factors protect people from the pandemic-related financial stress and diminish its adverse economic effects ( Qian and Fan, 2020 ). Building on these recent studies on economic impacts, this social justice research focuses on areas with pre-existing social disadvantages. We study the role of social disadvantage and its impact on labor market during the COVID.

The distribution of economic vulnerability may potentially be related to COVID-19 conditions including those of economic burdens for people living in the pandemic epicenters ( Creţan and Light, 2020 ). Similarly, socio-economic disruptions create “a characteristic mosaic pattern in the region” ( Krzysztofik et al., 2020 , p. 583). The disruptions are strongly correlated with the spatial distribution of the COVID-19-related health effects. This study is set in Tennessee which is part of coronavirus “red zone” states of the US southern Sunbelt region. It is among the U.S. states with the highest rates of cases per capita, with 137,829 cases per 1 million people, or the 6th highest as of August 13, 2021 ( Worldometers, 2020 ; https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/us/ ). The study seeks to explore the impacts of social disadvantage on economy. The impact is measured by employment and unemployment in unprecedented times in the US context of prolonged disruptions to the health system, society, and economy intersecting in complex ways ( Kiang et al., 2020 ). We answer the following questions: (1) Do communities with high social disadvantage already burdened pre-COVID-19 by the lack of income, healthcare access, lacking resources, have less jobs available during the COVID-19 pandemic? (2) Do these areas simultaneously experience higher unemployment compared with other areas in the context of the pandemic?

The paper is organized as follows: Section 1 introduces the topic, provides the background information on social disadvantage and a brief description of the study implementation. It further discusses the links between employment and unemployment, and coronavirus, respectively, and introduces the study area. Section 2 describes in detail materials and methods used in the study. Section 3 provides the theory and calculations. Section 4 reports the results, and Section 5 offers a discussion. Finally, the paper concludes with conclusions found in Section 6 .

1.1. Background

Certain socio-economic and demographic conditions burden some communities more than others including racial and ethnic minorities, lower-income groups, and rural residents. The conditions include lacking economic opportunities and other inequalities ( Petterson et al., 2020 ) caused by social environment. Prior to the pandemic, it was challenging to live in areas with high social disadvantage where residents already have increased vulnerability to poor health due to greater psychosocial stress such as discrimination, unhealthy behaviors, and poorer health status ( Hajat et al., 2015 ). This is true for poor, marginalized communities elsewhere as spatial segregation of disadvantaged and marginalized communities decreases life opportunities for their members who have limited relationships with broader communities ( Méreiné-Berki et al., 2021 ). Within the context of studying disadvantaged urban communities, a recent work by Creţan et al. (2020) focused on the everyday manifestations of contemporary stigmatization of the urban poor using the case study of the Roma people who have been historically subject to state discrimination, ghettoization, inadequate access to education, housing, and the labor market for many decades in the past in multicultural urban societies of Central and Eastern Europe. The inequalities may persist and even increase if left unaddressed during pandemics ( Wade, 2020 ) leading to stark COVID-19-related health and economic disparities. Indeed, during the COVID-19, economic impacts of the pandemic disproportionately affect marginalized groups. The impact of coronavirus was harsh for those people as many of the already existing disparities unfold during COVID-19: black communities in the United States are disproportionately affected by higher death rates due to the COVID-19 virus ( Thebault et al., 2020 ), unemployment, and financial stress. Other growing COVID-19 research similarly suggests that elsewhere outside of the United States, areas that were disadvantaged prior to the pandemic with high rates of poverty and unemployment tended to be affected the strongest by the COVID-19 with the largest concentration of cases, while other spatially segregated ethnicity-based communities (e.g., the Roma) that have been vulnerable decades prior to COVID-19, saw an increase in the existing discrimination and stigmatization experiencing greater marginalization even during the current COVID-19 pandemic period ( Crețan & Light, 2020 ).