Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Drama — Film Review: Lady Bird

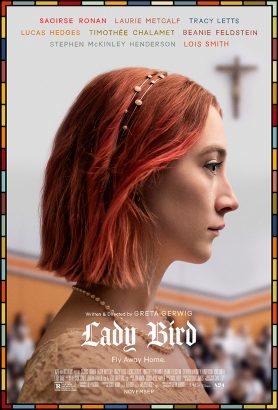

Film Review: Lady Bird

- Categories: Drama Movie Review

About this sample

Words: 1127 |

Published: Dec 12, 2018

Words: 1127 | Pages: 2 | 6 min read

Table of contents

Subject and symbolic messages of the film "lady bird", the movie is filled with insights about much more than money, works cited.

- Gerwig, G. (2018). Lady Bird (Motion picture). United States: A24.

- Gleiberman, O. (2017, September 3). Telluride Film Review: Greta Gerwig's 'Lady Bird'. Variety.

- Jenkins, M. (2017, November 2). 'Lady Bird' Is a Sensational Film About the Awkwardness of Growing Up. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/11/lady-bird-is-a-sensational-film-about-the-awkwardness-of-growing-up/544663/

- Kaufman, A. (2018, January 17). Director Greta Gerwig on the making of 'Lady Bird'. Los Angeles Times.

- Kohn, E. (2017, September 3). 'Lady Bird' Review: Greta Gerwig Delivers a Love Letter to Sacramento & Youthful Indiscretions — TIFF. IndieWire.

- Kroll, J. (2017, September 1). Film Review: 'Lady Bird'. Variety.

- Lee, B. (2018, February 23). 'Lady Bird': Best Picture Oscar Nominee: Everything You Need to Know. The Hollywood Reporter. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/lady-bird-best-picture-oscar-nominee-1087256

- Lewis, H. (2017, November 10). Greta Gerwig and Saoirse Ronan on How They Found the Voice of 'Lady Bird'. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/10/movies/greta-gerwig-lady-bird-interview.html

- Roeper, R. (2017, November 1). ‘Lady Bird’: Greta Gerwig’s directorial debut a flat-out triumph. Chicago Sun-Times.

- Scott, A. O. (2017, November 2). Review: In ‘Lady Bird,’ a Portrait of the Artist as a Young Woman. The New York Times.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature Entertainment

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 640 words

2 pages / 934 words

2 pages / 983 words

2 pages / 922 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Julius Caesar is filled with instances of foreshadowing, where subtle hints and clues are dropped throughout the text that suggest the events to come. Foreshadowing is a literary device used to create tension, build [...]

Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet is a timeless play that has captivated audiences for centuries. One of the key elements that contributes to the enduring appeal of the play is the effective use of dramatic irony. Dramatic irony [...]

Alfonso Cuaron's Roma is a Mexican drama film that follows the life of Cleo, a maid who works for a middle-class family in Mexico City during the 1970s. The film has received numerous accolades, including a Golden Lion award at [...]

In June 1943, Los Angeles saw a series of riots known as the Zoot Suit Riots involving American sailors and Mexican American youths. The riots were named after the Zoot suits, which were baggy suits worn during World War II. [...]

There are thousands if not millions of people constantly fighting for their beliefs every single day, however, they have commonly been considered as godless people or sinners by others. This is the case for the one and only, [...]

If i was asked about my favorite film, i would think for a rather long time about the answer. There are many well-rounded films that are released every week, so choosing best of them would be a complicated task. However, if i [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Her Identity of Place: On Greta Gerwig’s “Lady Bird” (2017)

When you are 18, your identity resides in the past. Where you are from, where you went to school, and who your parents are. You simply haven’t lived long enough to accumulate a string of accomplishments, nor have you had the opportunity to make enough life choices to define you. So, when you are uprooted at 18 and transplanted to a university—‘Where are you from? Where did you go to school?’—these are the questions asked. They serve as a shallow introduction—a way of establishing your place—of defining you—within these new surrounds.

Lady Bird is directed by Greta Gerwig, and I was familiar with her performance in Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha (2012), which is one of the most cinematically unattractive films I have ever seen. Shot in dingy black and white for no other reason than to evoke French New Wave, the film is typical Baumbach insomuch that you can almost hear him whispering, ‘ This is a Noah Baumbach film. Expect it to be intellectual with lots of literary namedropping .’ His films are sciolistic in some way or other, but admittedly there was something about Frances Ha that made me enjoy it, despite its weaknesses. Perhaps that something is Greta Gerwig’s performance as the ambitious yet vulnerable Frances.

Lady Bird stars Saoirse Ronan as Christine, a high school senior who prefers to be called Lady Bird, rather than her birth name. The reason is never explained but we can gather that she doesn’t like her ordinary life and so this is her attempt to differentiate herself. ‘Do I look like someone from Sacramento?’ she asks. ‘I hate California.’ Her mother Marion (Laurie Metcalf) works double shifts as a nurse and she takes her daughter’s words as a slight. ‘You have a great life,’ she informs. But Lady Bird, in midst of her longing, doesn’t see it. ‘I wish I could live through something. I want to go to the East Coast,’ she says. ‘I want to live where there are writers.’ ‘You can’t even pass your driver’s test,’ Marion reminds. (Gerwig, who is from California and attended university in New York, based Lady Bird on her own experience.)

The film captures adolescent perspective well. Lady Bird, who attends Catholic school, lands a role in a play but insists she doesn’t like it because everyone who auditioned got a part. What is the specialness in that? She meets her first romance—a boy named Danny (Lucas Hedges) whom she learns is gay, and has sex for the first time with a pretentious narcissist named Kyle (Timothée Chalamet) who uses words like ‘baller’ to define her. She laughs and eats unconsecrated Communion wafers with her best friend Julie (Beanie Feldstein), and she associates briefly with the rich, popular girl (Odeya Rush) who has no ambitions other than to live out her life in Sacramento and have kids. Nothing extraordinary happens to Lady Bird, but the film isn’t really about any of these things insomuch as it is about Lady Bird’s relationship with her mother.

Laurie Metcalf is most outstanding in this film—she is caring, warm, yet stubborn and headstrong. It is clear that she loves her daughter but has a hard time showing it. Rather than using supportive words, she feels that working double shifts as a nurse to support the household is enough. Likewise, Lady Bird is a bit of an ungrateful asshole. She feels shame for her parents’ lack of money and has moments of elitism where she looks down on them. Yet, she still longs for her mother’s approval. When the two go shopping for a prom dress, Lady Bird is deflated when her mother does not love the same dress as she. ‘You think it might be too pink?’ Marion asks. Then, in an honest moment, Lady Bird admits that she seeks her mother’s approval—that her mother’s opinion is important. ‘Do you like me?’ Lady Bird asks. ‘Of course I love you,’ Marion replies. ‘Yes, but do you like me?’

Greta Gerwig sets her film in 2002, aligning it with the technology and history of that time. Adolescents use terms like ‘cell phone’ (in 2022, the word ‘cell’ has long been dropped from the vernacular) and the Iraq War casts a pall over the television screens. Gerwig’s directorial skill is shown via her use of small conversational moments. Often, we are given glimpses of exchanges without knowing the full back story, thus adding realism. (‘I admire your mom. She let me move in when my parents kicked me out,’ says her brother’s girlfriend, Shelly.) After all, it is not important for an audience to know everything. Yet, the film’s lack is reflected in the rather conventional use of cinematography and standard shots. Lady Bird is assuredly more driven by character than image. While not a great film, Lady Bird offers a good depiction of a mother and daughter relationship—the tension, the struggle and ultimate affection.

Meanwhile, Lady Bird applies to college on the East Coast. With fantasies of attending Ivy League, she is not the best of students, and so she is put on a waiting list for a New York school. The film ends poetically with Lady Bird privately reading some of her mother’s hand written letters, which her father (Tracy Letts) secretly stashed into her bag before her departure. ‘Don’t tell her you saw them,’ he says. ‘She was worried you would judge her writing.’ We don’t know exactly what the letters say, other than that they are hand written in pencil. It appears that Marion put much effort into writing them—‘Dear Christine,’ one letter says. ‘Dear Lady Bird,’ says another. It is evident that Marion cares what her daughter thinks—that both mother and daughter want to be seen and understood and valued by the other. Just neither knows how to express it. That Greta Gerwig chose for the audience to not know the full details of the letters shows a subversion of cliché on her part.

In just the short time in New York, Lady Bird drops her alias and introduces herself as Christine. She finds herself marveling over past childhood scenes, where she is driving for the first time in Sacramento. She stops into a church on a Sunday and momentarily witnesses a mass. A religious person could claim she was missing her faith, but this is more about her self-acceptance. It goes beyond homesickness, as that would be too easy. Rather, Christine realizes who she is, her past, her parents, her life—that all of it is hers and not necessarily bad. What is life but the people and places that have shaped us?

Several reviewers have mentioned that they were disappointed in the ending, as we are not provided any perfect bow-tie resolution. Instead, it is a one-way conversation—Christine leaving a message for her mother: ‘Mom, did you feel emotional the first time that you drove in Sacramento? I did. All those bends I’ve known my whole life, and stores, and the whole thing. But I wanted to tell you I love you. Thank you.’ Who knows if she would have left these words had she not seen her mother’s letters. Both conversations—Christine’s message and her mother’s letters—take place one-way. Yet we know that this mother and daughter pair will someday speak and doubtlessly they will fight. Some things are ever certain. Cherish what we remember. Who is to say that is not the perfect resolution?

If you enjoyed this review of Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird, consider supporting us and get patron-only content on our Patreon page . This will help the growth of this site, the automachination YouTube channel , and the ArtiFact Podcast . Recent episodes include a survey of photography from Josef Sudek to Laura Makabresku , an examination of Abstract Expressionism as depicted in Kurt Vonnegut’s Bluebeard , and a debunking of Internet sciolists such as Jordan B. Peterson and Christopher Langan.

More from Jessica Schneider: The Human Intrusion: Michelangelo Antonioni’s “Red Desert” (1964) , Charlie Parker & The Drive For Greatness In Damien Chazelle’s “Whiplash” (2014) , So Much Is Delicate: C. Scott Willis’s “The Woodmans” (2010)

Begin typing your search above and press return to search. Press Esc to cancel.

Privacy Overview

Lady Bird and Struggling with My Identity

Jtube: Better Off Ted

Sidney poitier and the jewish waiter who taught him how to read.

Funny Stuff

Funny Passover Jokes

Jtube: different strokes: conversion.

Our weekly email is chockful of interesting and relevant insights into Jewish history, food, philosophy, current events, holidays and more...

Who we are versus how we wish the world would see us.

Note: Spoilers ahead.

“Do I look like I'm from Sacramento?” Lady Bird asks her mother in the opening line of the film.

“You are from Sacramento,” she replies.

Right from the start the major Oscar-contending film, Lady Bird, begins drilling home its theme. Christine “Lady Bird” McPherson is struggling with what every teenager struggles with: Identity. Who we are versus how we wish the world would see us.

Lady Bird hates so much about her life. She hates her given name, Christine, insisting everyone call her Lady Bird. She hates that she lives in Sacramento, she hates that her family is poor, and she hates that she’s bad at math. She’s willing to do just about anything to escape from this identity. Early on she demonstrates this with a casual leaping from a speeding car. Why? To protest her mother’s objections to her applying to an out of state college. You’d think the lesson of a broken arm would teach her that one can’t run from their identity so easily. But Lady Bird is fierce and determined.

It takes the journey of this film for Lady Bird to come to appreciate where she came from. Her journey in some ways paralleled my journey in wrestling with my Jewish identity. My journey to becoming a baal teshuva , one who becomes Jewishly observant later in life, has been five years in the making. It’s been a journey of benchmarks, tiny decisions to continue further on the path and loads of conflict.

I spent a good chunk of my life running away from Judaism. I used to take a lot of pleasure in arguing with religious people, tearing them down to make them feel wrong. I remember a sleep over when I was in 8 th grade where my friends Patrick, Jeremy, and I lambasted my friend Steven for having any sort of faith. Needless to say, Steven didn’t remain religious much longer.

I felt becoming religious was a capitulation of the identity I had built. The people I respected and looked up to were all intellectuals who criticized Judeo-Christian values as ignorant and destructive. What’s funny is the first book I was introduced to when I first started to dabble in Torah learning was Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzato’s classic work, The Path of the Just . In the introduction, he comments, “ The study of [piety] and reading of works of this kind have become the province of those whose minds lack subtlety and who are mentally sluggish… This has given rise to the prevalent idea that anyone striving for piety is suspected of being dull-witted.” I think it was the fact that Luzzato directly addressed my view on religious people that allowed me to set aside apprehensions and to continue on.

Like Lady Bird, I struggled with my changing identity. During the first years of my increased observance I would hide my performance of mitzvot from my friends and family. Leaving work early on Friday to go to a Shabbos dinner in the Pico community, I’d tell people I was going to a networking event in Beverly Hills. I refused to wear a kippah in public, so I’d wait for the coast to be clear and surreptitiously cover my head with my sleeve or nearby napkin while saying a blessing before eating or drinking.

Then one evening there was a major shift in the way I viewed my Jewish identity. It was my 31 st birthday and I was in Tess’s apartment. Tess grew up Mormon but she had walked away from the Church because she always felt looked down upon. Despite that, she still wouldn’t mess around with a guy she didn’t see the potential of having a serious relationship with. That night she’d taken me out to dinner and we ended up alone at her place to watch a movie I know she has no interest in. We started chatting about old relationships and I brought up my last one, a girl named Alexis.

“Was she nice?” “Yeah. Sweet too.” “So what happened?”

For some reason I decided to tell the truth, knowingly dashing any hope for a tryst with Tess. “She wasn’t Jewish. And I only seriously date Jewish now.”

It was the first time I had articulated that decision. Our romantic tension immediately dissipated.

The moment parallels a scene at the end of the film. Lady Bird has gotten in to a New York school and attends her first college party. She taps some random guy on the arm and asks, "Do you believe in God?"

He bluntly replies, "No."

She asks why not and he answers, "Really? Uh, it's ridiculous."

Then she shoots back, "People call each other by names that their parents made up for them, but they won't believe in God."

He asks her for her name and for the first time she answers, "Christine," the name her parents gave her, not Lady Bird. After some further turmoil, she then she calls home, with a newfound appreciation for where she came from.

No matter how thin my connection ran, deep down I always respected the values Judaism had brought to the world. The sanctity of life, the importance to question and think, to make the world a better place. These were ideals I received from parents and would hold onto despite my rejection of an “organized religion”.

“If I don’t know myself, I don’t know anything.” Rabbi Noah Weinberg

I also knew that before I could completely part from my religion, I would need to take a look at it from an adult perspective and challenge it as strongly as I had challenged Steven in 8 th grade. Not from a place of looking for contradictions and deficiencies so I could declare my independence with a clear conscience, but from a place of genuinely trying to understand the other perspective. When I finally did that, I got some good answers. So I asked more questions and continued to get good answers.

And in discovering those answers I also discovered a part of who I really am: a questioner who isn’t satisfied with blindly doing anything. I may have taken a different road than my parents, but it’s the values and ideals they instilled in me that lead me here.

RECOMMENDED NEXT READ

- Human Interest

- Torah Portion

- Ways to Wisdom

- Holocaust Studies

- Prayer & Kabbalah

- Ask the Rabbi

- Legacy Giving

- Shabbat Times

- Aish World Center

- Israel Programs

- Weekly Torah Portion

- Prayer and Kabbalah

- Western Wall Camera

- Jewish Name & Birthday

- Candle Lighting Times

- One-on-One Learning

- Submit Articles

- Contact Aish

- Privacy Policy

The Psychology Times

Independent voice for psychology in louisiana.

Lady Bird: A Review

Lady Bird: A Review by Alvin G. Burstein

Lady Bird is a coming of age story, a bildungsroman. We follow its protagonist, a teen-ager discontent with herself and her situation, beset with a vague yearning to change her life and herself, as she struggles to free herself from what she feels confining her. The film opens with an epigraph displayed on the screen: Anybody who talks about California hedonism has never spent a Christmas in Sacramento. That is where Lady Bird lives, and, moreover, on the wrong side of the tracks. Living with her are her father who is unsuccessful in fending off unemployment, her critical and controlling mother who works double shifts as she scrabbles to make ends meet, a brother, who is tattooed and decked with body piercings, and the brother’s live-in girlfriend.

Lady Bird dreams of becoming someone, leaving home, going to an Ivy League college. Her grades, alas, are mediocre and its financial demands overwhelming. She steals looks at a classmate’s paper during a math exam and hooks the instructor’s grade book so that she can finagle a B in the class. She lies to classmates about where she lives, representing her home as being in an upscale neighborhood. She steals fashion magazines that she cannot afford to buy.

The film is a brilliant debut effort by Greta Gerwig, who wrote the story and directed the film. Gerwig leavens the grimness of Lady Bird’s struggle with genuinely comic elements. The director makes the young girl sympathetic—no, loveable— because of her wit, her self-awareness, and the universal and urgent nature of her adolescent struggles with self-esteem.

The film opens with Lady Bird riding with her mother in an auto while they listen to a recording of The Grapes of Wrath, an elegant bit of foreshadowing. That book ends with the mother of the Oakie family shooing the men away and supporting her daughter, whose infant child has just died, to nurse—literally— an elderly starving man. The novel ends with a reference to the daughter’s “mysterious smile.”

Lady Bird and her mother both weep as the reading ends, but begin to squabble when Lady Bird wants to move on to another tape. The fighting escalates, and the daughter jumps out of the moving car, breaking her arm.

A 1989 publication by the SUNY Freud Museum, Sigmund Freud and Art, cataloguing and describing Freud’s collection, contains a chapter by Ellen Handler Spitz, Psychoanalysis and the Legacy of Antiquities. Spit draws our attention to the head of Demeter owned by Freud, and reminds us of the story of Demeter, the goddess of harvest and of the cycle of birth and death, and her daughter Persephone. In the Greek myth, Persephone is kidnapped into marriage by the king of the underworld. Demeter, distraught, searches for her lost daughter. When, after much effort, she finds her, only to learn that during her captivity Persephone has swallowed six pomegranate seeds, and thus can only spend half of each year with her mother, returning to the underworld for the other half.

Spitz suggests this tale is as figural for psychoanalysis as is the more famous one of Oedipus, the latter with its emphasis on the tension between fathers and sons. Spitz explores various interpretations of the Demeter myth and argues for its potential to counterbalance the patriarchal focus in psychoanalytic practice and theory. At a minimum, she sees the Demeter myth as central in directing our attention to mother-daughter relationships, especially as they relate to issues of birth and loss, and of separation and reunion.

Lady Bird ultimately leaves home and mother. Do they find each other again? Yes and no. You will have to see the film to decide.

Share this:

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Greta Gerwig’s Exquisite, Flawed “Lady Bird”

By Richard Brody

That Greta Gerwig is a brilliant writer has been clear since the very start of her movie career, because the films in which she first starred, such as “Hannah Takes the Stairs” and “Yeast,” were already her feats of writing. Her dialogue in those films was mostly improvised, but it’s vastly superior to the texts of many acclaimed screenwriters. Other films that she has written, “ Frances Ha ” and “ Mistress America ,” are as readable as they are watchable. And her new film, “Lady Bird”—the first feature that she has directed alone, the first to be fully scripted, the first to be made on a substantial budget with a large and professional cast and crew—is full of exquisite dialogue. The experience of watching it for review is the experience of scribbling in the dark as fast as humanly possible, not only to be able to quote it and describe it but, above all, to be able to savor it.

In “Lady Bird,” Gerwig tells a coming-of-age story for a young woman in Sacramento, set between the fall of 2002 and the fall of 2003, that’s loosely autobiographical, cognate with very general aspects of her life. Gerwig, like the film’s protagonist, Christine “Lady Bird” McPherson (played by Saoirse Ronan), grew up in Sacramento, attended a Catholic high school, and went to New York for college. But what’s most significantly personal about “Lady Bird” isn’t the setup but the details—the emotional world of its characters, the touches of whimsy and grace with which she creates it.

The very title is a story in itself—when Christine is asked for her given name, she says “Lady Bird” and explains, “It was given by myself to myself.” Her fierce struggle to be called by this name is the struggle over what she got from, or is given by, her parents. Marion McPherson (Laurie Metcalf) is a nurse who puts in long hours at work and seems to do the bulk of the housework; she’s also extraordinarily frank about the difficulties that she and her family endure, and her frankness puts her into bitter conflict with her daughter. Lady Bird wants, above all, to leave Sacramento, to go to college on the East Coast—if not in New York, then “in Connecticut or New Hampshire, where writers live in the woods.” Marion insists that the family can hardly afford for her to attend a state school, so Lady Bird asks her easygoing and good-humored father, Larry (Tracy Letts), to complete a financial-aid application for her without telling Marion. He does so—but when the secret gets out, it drives a seemingly irreparable wedge between Lady Bird and her mother.

“Lady Bird” takes its protagonist through adolescent solipsism to recognition and gratitude, through the hazards of friendship complicated by matters of self-image and self-imagination, through openhearted but uncertain fumblings of romance, through the unresolved and ever-mounting tensions of family life and the acknowledgment of its hard material practicalities, to a radiant reconciliation with her family, her home town, and herself. Lady Bird’s fine-grained perceptions come with a delicate meter of social distinctions and, with it, the desire for the pleasures, the sense of freedom, that money can buy—money that her parents don’t have. All the relationships in the film are tempered and conditioned by money. There’s Lady Bird’s friendship with Julie (Beanie Feldstein), who lives in a modest apartment with her single mother, and her sweet romance with Danny (Lucas Hedges), whose grandmother lives in her “dream house,” and who invites her to his family’s Thanksgiving feast. There’s Lady Bird’s next romance, with the rocker Kyle (Timothée Chalamet), who claims to “hate money” but lives a life of comfort on his family’s dime while attending a costly private school. And there’s Lady Bird’s effort to curry friendship with the school’s wealthy queen bee, Jenna (Odeya Rush), by pretending to be a rich kid herself, tossing out seemingly oblivious remarks with a self-conscious self-control.

Gerwig doesn’t romanticize the McPhersons’ genteel frustrations; she shows that they wear on Lady Bird as well. When Marion chastises Lady Bird for being demanding after Larry loses his job, Lady Bird responds with a smart but immature tantrum, insisting that Marion give her “a number”—tell her how much it costs to raise her: “I’m gonna get older and make a lot of money and write you a check and never speak to you again.” (Marion’s retort is both admirably calm and decisively cutting: “I doubt you’ll get that good of a job.”) Later, speaking of Larry’s depression (and trying to uncouple it from his job insecurity), Marion tells Lady Bird, “Money isn’t life’s report card. Being successful doesn’t mean that you’re happy.” Lady Bird responds, “But he’s not happy.” It’s a brilliant exchange: just as money doesn’t guarantee happiness, it’s no bar to it, either. On the contrary, Lady Bird has a vision of herself—of style and of freedom of action—that will take money to foster and sustain. In her sour retorts, there’s a ring of truth.

The movie is filled with insights about much more than money—for instance, in one series of riffs played mainly for comedy but shadowed with terror, a male math teacher, young and perky, flirts with Julie, never stepping openly out of bounds but clearly grooming a curiosity, even a desire, that hints at grave possibilities. The character of Lady Bird is impulsive, ardent, spontaneous. She disrupts and lampoons a school assembly about abortion; she plays a reckless practical joke on the school’s principal, a nun (Lois Smith); she declares with a curtly decisive frankness when she doesn’t want sex and when she does.

Nonetheless, Lady Bird’s volatile temperament comes through more in the writing and the drama than in the performance; Ronan doesn’t quite display the text’s sudden and mercurial energy. Metcalf, playing a character of taut and measured precision, steals the film with her precise inflections and focussed glances. In general, Gerwig favors precision in “Lady Bird.” If the films in which she came up flaunt ambiguity and the impenetrable, opaque idiosyncrasies of people (a reason why John Cassavetes is a hero to this generation of filmmakers), here she focusses her emotions within tight limits, the better for them to ring out and harmonize with a piercing, poignant clarity.

This air of restraint is conspicuous throughout the film, and the price of that clarity is freedom—Gerwig’s own as well as that of the actors. “Lady Bird,” daring, distinctive, and personal in text and theme, is recognizably conventional in texture and style. The bulk of the film is, in effect, pictures of actors acting—acting with skill and care, imagination and vigor, but with no more originality of tone or temperament than Gerwig brings to the direction of the film—at least, to most of the direction of the film. Her attention to the nuanced glances of characters adds extra psychological and comedic dimensions to the dialogue and the action. But for a movie that’s as deeply devoted as “Lady Bird” is to a sense of place, to a tribute to that place, it seems to inhabit that place so thinly, offering snippets of prominent sites without much proximity to them. The movie is nearly devoid of vistas, lacking moments between scenes when nothing special but vision and motion are happening, lacking even the walking and talking in places that the characters frequent. (The tendency is clear from the start, when a scene of Lady Bird and Julie visiting their dream houses seems nearly detached from the streets around them.) It’s also devoid of narrative vistas—its scenes are cut tightly to fit and leave the characters, and the actors, little in the way of comings and goings, of space to breathe, to look, to be. (As I watched the film, I yearned to see what went on between the characters just after each scene, between each transition.)

Gerwig’s restrained direction emerges from the very ideas in the film. The aesthetic of “Lady Bird,” its emotional and dramatic legibility, is a realism of morality, an utterly uncynical but clear-eyed sense of the responsibilities that come with the kind of money that it takes to make such a film, the kind of stylistic and tonal expectations that a movie of this sort creates and should fulfill in order for it to take its place in the field—and for Gerwig to take her apt place there along with it. There’s nobody in the film who performs with the freedom or the originality that Gerwig herself offers as an actor—in part, because Gerwig doesn’t give her actors an open narrative framework or production environment akin to the ones that have given rise to her own most original performances (including “Nights and Weekends,” from 2008, which she co-directed). “Lady Bird” isn’t a film that is stuck in conventions; it’s one that borrows them, but from within, not quoting them but treating them, too, with a sort of practical respect for a mature art that’s akin to the very reconciliations that are built into the story itself.

Nonetheless, two scenes, occurring late in “Lady Bird,” are among the most thrillingly directed of recent moments, and suggest with a clarion intensity that her directorial imagination reaches beyond the film’s primary mode of practical drama. To avoid spoilers, let’s just say that one is a scene of Marion driving by herself, and the other is a scene featuring flashbacks from Lady Bird’s point of view. These scenes, composed of disparate elements, rich in subjectivity, conjuring drama and emotion with simple but bold devices of editing, rise very high as cinematic music. These brief moments are the movie’s greatest exhilarations; even more than the copious and generously imagined drama that gives rise to them, they suggest the wider and freer inspirations of the directorial career that, if there’s any justice in the industry, Gerwig is launched on.

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Anthony Lane

By Helen Rosner

Film Review: Lady Bird

Rachel attenborough reviews 2018 film lady bird (written and directed by greta gerwig).

Lady Bird likely needs little introduction. Garnishing almost universal critical praise, Greta Gerwig’s directorial debut, starring Saoirse Ronan, tells the story of eccentric adolescent Christine ‘Lady Bird’ McPherson, growing up on the (literal) wrong side of the tracks in Sacramento, as she wiles away her final school days and prepares to go to college. It is a beautifully shot, heartfelt, coming-of-age drama and a love letter to the importance and power of female relationships. I’ve been a fan of Gerwig’s since her first feature Frances Ha and I knew I was going to love Lady Bird before I’d even bought my popcorn. The script is witty and heart-breaking and sharply observant. Growing up in the suburbs and, like Lady Bird, going to an all-girls school, I could relate with warm nostalgia to the fierce friendships and chasing boys, to the giddy joy and the crushing fear that comes with growing-up. I was also excited by the clear feminist love at the heart of the film; Lady Birds’ core relationships are with her hard-working mother Marion and her best friend Julie. Both relationships are rocky, both are challenging, both are worth it. In Lady Bird , boys are selfish and fleeting, men though dependable are dependants. There’s no denying this a film by women, staring women, about women. I was therefore surprised when Lady Bird lost all five of the Oscars it was nominated for. With the pro-feminist energies around Hollywood at the moment; surely this was the year when such an openly female-led production would triumph? On reflection, my own fandom may have clouded my judgement. The film of course, isn’t perfect. Gerwig’s naiveté behind the camera is sometimes apparent and at just over an hour and a half Lady Bird wilts slightly in comparison to the Academy’s ultimate choice for ‘Best Picture’; Guillermo del Toro’s reimagined Beauty and the Beast love story The Shape of Water. Yet I personally found Lady Bird ’s flaws part of its charm and in a time when Gerwig is still, in the 90 th year of the Academy Awards only the 5 th woman to ever be nominated for Best Director, I think its important to acknowledge the influence of this film and the scope of its accomplishments. Lady Bird may be a narrow, quirky, simple story but its unassuming honesty and genuine humour made it a film I can’t wait to watch again.

Rachel is currently studying for her MSt in Women’s Studies with research specialising in the construction of female identities and sexualities in Twentieth and Twenty-First Century literature. Having studied English with Drama and Education at Cambridge for her undergraduate degree, she is interested in promoting both emerging and reclaimed areas of women’s stories and histories, with particular focus on Young Adult fiction and autobiographical writing.

Return to Blogs.

- Reflections

Brighton and Hove Psychotherapy

March 13, 2018 by Brighton & Hove Psychotherapy Leave a Comment

Lady Bird: a Psychotherapist’s Perspective on Key Themes

Warning – This article contains spoilers for anyone who has not seen the movie Lady Bird.

A critical success, this film about a mother and daughter relationship falls into the ‘coming of age’ genre, however it is also so much more than this in considering the systemic and unconscious processes at work that make this film both poignant and painful to watch.

There are many key themes present relating to those clients bring to psychotherapy, however I would like to pick out a couple that stood out for me which are perhaps better posed as questions we can imagine that the protagonist of Lady Bird – Christine) – is unconsciously grappling with:

What is my desire?

How do i leave my family.

These two questions whilst posed separately, are in reality interconnected, as it is through desire that we leave the family. However, in a family where the roles are blurred, and for a young woman whose desire has always had to be curtailed to cope with her mother’s envy, the two questions are complex and the unconscious conflict immense. The unconscious imposition on Christine is that the must not be thought about – as is the case with any young women whose mother envies her.

From the opening scenes, we see a mother who struggles to see her daughter as separate to her – Christine is as though an extension of her mother. She clearly loves her daughter, but also invests her own unfulfilled desires into her which places enormous pressure on Christine. This is suffocating for Lady Bird, to the extent that in an early scene, she flings herself from the car to escape the literal confines of being with her mother – a both literally and symbolically powerful moment: existence is impossible with her mother and hurling herself from a moving vehicle is less a thought-out action of leaving, than a murderous gesture – self destructive to her and to her mother.

As the film unfolds, the usual twists and turns of teenage experience are interspaced and amplified by the complexities of Lady Bird’s family. Her father is impotent – he loses his job and cannot separate mother and daughter. However, what he does know is that Lady Bird must leave, and he facilitates this through making financial arrangements for her university education, without involving his wife to whom he seems to be unable to stand up against (or to come alongside). This arrangement is pragmatically what Lady Bird needs, however, psychically it further undermines her autonomy and blurs any clarity of who she is in the family and who she is in relation to her mother. Her father can only facilitate her escaping his wife’s clutches by acting secretly.

An Envious Mother

Lady Bird understands, like so many of us who have had envious mothers, that she needs to ‘split off’ (disavow) her desire and that it can only be met secretly, if at all. Or she can turn it into something destructive. Both choices aim to unconsciously protect her relationship with her mother.

She gets in with the exciting, but bad crowd and swaps her boyfriend (who it turns out is gay meaning he cannot provide her with an exit from the family) for an aloof boy who, like his friends, is nihilistic in his outlook on life. Neither her gay boyfriend, nor her disinterested one, will help her leave her family, as neither contain her true desire. Here Lady Bird seems to be asking herself less about her own desire and more about that of others: who am I for others and what do they want from me? A question she asks herself repeatedly in the relationship to her mother for it is the only question she knows how to pose.

Owning her Desire

There are two scenes in the film which fill us with hope for Lady Bird: the first when she owns her wish to go to the school prom and be with her old friends, thereby stepping away from her less nihilistic friends who are ‘too cool’ for school, but who in reality actually have no idea about what they want, other than to rebel. To rebel is an expression of anger and frustration but it is ultimately impotent in nature as it is not borne out of desire. Rebellious teenagers don’t actually want to leave; that takes a revolutionary.

The second scene of hope is at the end of the film where Lady Bird is at an unnamed university in New York. Lady Bird’s father has slipped a pile of discarded attempts at a letter her mother tried to write to her into her suitcase which she finds. This is significant, as Lady Bird’s father is finally able to help mother and daughter separate: he encourages his daughter to leave but provides her with the evidence her mother loves her; he assumes his rightful position as his wife’s husband by consoling her at the airport when she, as a result of her struggle to let her daughter have her own desire and individuate, misses her daughter’s departure.

To Individuate or Rebel?

Towards the finale, there is a perfectly ordinary scene with Lady Bird, at what me must assume is her first party in New York, she drinks, meets a guy and they end up at his or hers. She then becomes ill and the next scene is at a hospital where we learn she has drunk far too much. This scene is a reminder of the powerful unconscious forces at play in Lady Bird – whether she can find a way to individuate and own her desire or create distance from her internalised mother through self-destructive acts (think back to the hurling herself from the car).

Ultimately the viewer is left with hope as she seems to have enough psychic distance to claim her birth name – Christine – and to find ways to be like her parents (visiting a local church), without having to be defined by being them, or not being them.

Christine makes a call home to speak to her mother but she gets the answerphone. The message here? That her mother and family can survive her going and that they can too move on with their lives. She is free.

Sam Jahara is a UKCP registered psychotherapist, certified transactional analyst and clinical supervisor . She works with clients and supervisees in Hove and Lewes.

Face to Face and Online Therapy Help Available Now

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Hove Clinic 49 Church Road, Hove, East Sussex, BN3 2BE

Lewes Clinic Star Brewery, Studio 22, 1 Castle Ditch Lane, Lewes, BN7 1YJ

Privacy Overview

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Youth in revolt: is Lady Bird the first truly feminist teen movie?

Greta Gerwig’s film packs in John Hughes-style teenage angst. But its focus on self-determination and female bonds – rather than validation by boyfriend – sets it apart

- Warning: this articles contains spoilers for Lady Bird

The teen movie is an often raucous affair: embryonic sexual stirrings, combative parent/child relationships and the heart-tugging turbulence of post-adolescent friendship – which is why it is surprising to find Greta Gerwig’s directorial debut, Lady Bird, such a quiet and understated film. But there is perhaps something about Gerwig’s delicacy of touch that lends clarity to one of the film’s most resounding themes: its unapologetic feminism.

The central character (Saoirse Ronan) – unsatisfied with her comparatively drab given name, Christine – precociously assumes the alias Lady Bird. She dresses in thrift-shop clothes, has clumsily dyed pink hair and dreams of leaving what she deems the cultural wasteland of Sacramento, California, and her claustrophobic Catholic high-school – to study at a pricey liberal arts college on the US east coast.

Lady Bird is in many ways a feminist recalibration of the sort of genre tropes associated with the teen film. It seemingly has more in common with John Hughes’s hormonal outings in the 1980s than the 90s second wave ( Clueless , 10 Things I Hate About You ), or even more contemporary takes on the genre ( Easy A , The To Do List). Lady Bird has something of the everydayness of Molly Ringwald’s various incarnations – minus the ramped-up passivity and recursive romantic trajectories that freighted many of Hughes’s films. Lady Bird has two love interests: Danny (Lucas Hedges), a sweet fellow-member of her school’s drama programme and Kyle (Timothée Chalamet), a disaffected musician of Jordan Catalano proportions. She breaks up with the former after discovering him making out with a boy in a toilet cubicle, and tires of the latter on seeing through his calculated pseudo-rebel persona.

Lady Bird regards neither romantic breakdown as a treatise on her general worth: how she values herself is almost entirely self-determined, a bullish sense of her potential. She comforts Danny on his struggle to come out, pressing his head to her chest and tenderly raking through his hair – an instinct to nurture men perhaps inherited from her mother, who tiptoes around her father as he struggles with depression. On learning Kyle is not a virgin (though he insinuated he was), after first having sex with him (or anyone), she exclaims: “I was on top! Who the fuck is on top their first time!” Virginity is often a preoccupation in Hughes’s films, and notably for Ringwald’s characters – but unlike in The Breakfast Club or Sixteen Candles, Lady Bird’s virginity is not symbolic of her failure to engage with life, nor her apparent innocence; like her short-lived relationships with men, sex is not something she structures her identity around, rather a thing that happens.

Lady Bird’s more romantic subplot comes from her relationship with her best friend Julie: Julie and Lady Bird drift apart following Lady Bird’s dalliance with a more popular girl, a relationship that is severed when she makes a cruel comment at the expense of Julie’s mother. Teen films often reinforce the notion women can only find fulfilment via a conventional heterosexual coupling, usually advanced by the man. Lady Bird subverts that, and the film’s romantic apex is found in Lady Bird and Julie’s reconciliation. Lady Bird ditches Kyle and the cool girl en-route to the prom to return to Julie: they slow-dance under pastel-coloured streamers then walk home holding their shoes.

But Lady Bird’s most significant relationship is surely with her mother Marion: the roundly wonderful Laurie Metcalf . Maternal love is depicted with a necessary brutality: Marion perpetually chastises Lady Bird, telling her she’s unlikely to get into the east-coast college of her dreams on account of her poor work ethic and bad grades. (Lady Bird throws herself out of a moving car in response.) It is understood she is fostering in her daughter the grit and resolve required to exist in the world, a strength she vividly inhabits. And Lady Bird, with her steely sense of a right to exist and an entitlement to pursue her ambitions, seems not to have fallen too far from the tree. Lady Bird makes it to college in New York: at a party a co-ed asks her name, and after a pause, she answers: “Christine.”

- Young people

- Greta Gerwig

- Saoirse Ronan

- Laurie Metcalf

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Competitions

First ten pages: lady bird (2017).

By Travis Maiuro · March 8, 2018

Screenplay by: Greta Gerwig

Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird captures the quarrelsome, I-can’t-stand-you-but-I-love- you bond between mother and daughter. It’s a dynamic that blends humor and sadness. But Lady Bird is also a lesson in nostalgia — not only because it’s set in 2003, but also in the way Gerwig portrays her hometown of Sacramento almost as a character itself in the script, looking back on it with clear fondness. The script is an incredibly confident and unique take on growing up.

ESTABLISHING TONE AND/OR GENRE

Page one finds Lady Bird and her mother, Marion, waking up in a motel room together, sharing the same bed. The first image of the two is probably the most peaceful we will ever see them when they’re in the same room. The tone here is quiet and funny in a real way — like Lady Bird nitpicking at her mother making the bed, and mom giving her a very “mom” type of retort.

In the next scene, the tone opens up a bit, and we begin to see just what type of movie this is supposed to be.

Marion and Lady Bird begin to do what they’re best at — and what they’ll be doing for much of the movie: bickering. Their rapid back and forth is honest but funny and it’s clear we’re supposed to be enjoying this, finding the humor in it. Their arguing continues for another two pages until, on page 4, Lady Bird does this:

The moment is borderline slapstick and probably one of the only “big” comedic moments in the script, as the rest of the humor is more grounded in tone. Though, the immediate next scene opens with what turns out to be the punchline of the previous scene:

From this we also gather that the tone won’t be a tame coming-of-age movie, so to speak.

INTRODUCING THE MAIN CHARACTERS

From the above pages, we see that we are introduced to Lady Bird and her mother right away. Their dynamic is fiery, antagonistic, and humorous. It’s also raw and realistic, which turns out to be one of Lady Bird’s defining strengths. Through their back-and-forth dynamic, Gerwig wastes no time in letting us know the type of women Lady Bird and Marion are. We learn how Lady Bird feels about her hometown Sacramento and her desire to leave. Marion almost plays the “straight man” to Lady Bird, constantly providing the reality check that brings her daughter’s spirits down.

In the pages that follow, we meet her best friend JULIE, who also goes to Catholic school with Lady Bird.

Right after meeting Julie — and how she and Lady Bird both bond over their shared dreams about living in the “nice” part of Sacramento — we meet Lady Bird’s adopted brother. Despite the slice-of-life feel of the script, it’s incredibly efficient writing. Scenes are succinct, clearly — we’ve already met all of our main characters by page 9. (The only one missing, Larry, Lady Bird’s DAD, is introduced on page 11.)

THE WORLD OF THE STORY

These opening pages showcase our characters in what will become the story’s world: Immaculate Heart of Mary, streets of Sacramento, etc. Page 6 sets up in further detail what will become part of the story’s world: theatre.

We, and Lady Bird, learn that the school has a theatre arts program inside of SISTER SARAH-JOAN’s office (which will also become part of the story’s world, as we’ll return to it later on — Sister Sarah-Joan’s conversations with Lady Bird are some of the funniest of the movie).

The first ten pages efficiently do what they’re supposed to do: they reveal that Lady Bird’s story will take place within the confines of Catholic school/high school and suburbia. The stage has been set for a coming of age story.

Coming of age. Growing up. Those are the fairly obvious themes. But these first ten pages also establish themes of longing (Lady Bird’s longing to move away from Sacramento, her longing of what she sees as a better life when she looks at the fancier houses), individuality (which Lady Bird has no problem embracing… clearly), home, nostalgia, what it means to be a family, and financial security. It’s quite a lot to take in in just ten opening pages, but Gerwig manages it deftly.

Having Lady Bird talk about college with her mother and then Julie works because, well, she’s a senior in high school, of course she’d be talking about college. But it also works on a technical standpoint because it allows a natural way for the money issue to be brought up.

Much of the script features Lady Bird in every scene, but page 10 finds the script briefly checking in on Marion. This scene is important because it shows (doesn’t tell) what Marion does for a living and goes on to show her driving through Sacramento — home.

We learn Marion has to work night shifts in order to support the family, which adds even more weight to the theme of financial security. And Gerwig drawing attention to Marion’s drive home is important because we’ll later see Lady Bird do the same thing: driving through the theme of home, the theme of nostalgia.

THE DRAMATIC SITUATION

One could argue that the film’s dramatic situation could be summed up with Lady Bird’s very first line seen on page 1: “Do you think I look like I’m from Sacramento?” She wants to get out. She wants to go to college in New York — but money is an issue. She also wants to be herself because she’s perfectly happy being herself, as we see in the scene with Sister Sarah-Joan. Joining the theatre program allows her to be herself, while also maybe helping with potential scholarships for school, because, hey, you never know — might look good on the application.

But yes, more than anything, the dramatic situation is established right off the bat: Lady Bird’s love/hate relationship with her home Sacramento. And through this, the film’s other, perhaps deeper, dramatic situation reveals itself: Lady Bird’s relationship with her mother. It seems too cold to also characterize that as a “love/hate” relationship because it’s so much more than that. It’s a love story. Will they or won’t they find solid ground? Will they or won’t they see eye to eye? Will their love stay strong?

Travis Maiuro previously taught the craft of writing while pursuing his MFA in Screenwriting from the University of Texas at Austin. He also writes about movies here .

Download Free Trending Scripts

Breaking Bad

Poor Things

Raiders of the Lost Ark

Mr. and Mrs. Smith

Stranger Things

Oppenheimer

Next related article.

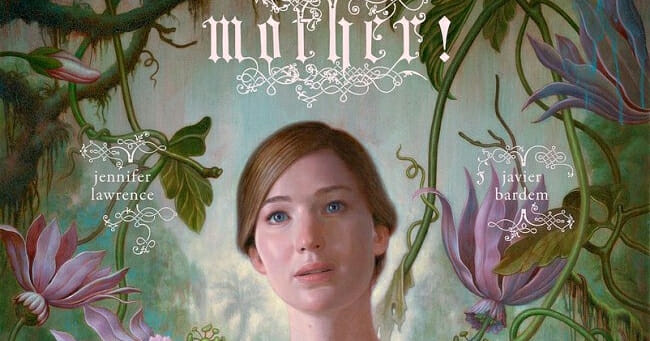

First Ten Pages: Mother! (2017)

Danielle Karagannis · January 17, 2018

Recent Articles

A brief history of film noir.

Martin Keady · April 17, 2024

Moving Monologue: The Best Movie Monologues That Leave Audiences Speechless

Ken Miyamoto from ScreenCraft · April 15, 2024

What Is the Wilhelm Scream?

Ken Miyamoto from ScreenCraft · April 10, 2024

Launch Pad Prose Competition

Deadline: April 20th, 2024

Moonshot Pilot Accelerator

Deadline: April 21st, 2024

Deadline: May 20th, 2024

More Related Articles

First Ten Pages: Zombieland (2009)

Danielle Karagannis · July 10, 2018

First Ten Pages: I, Tonya (2017)

Danielle Karagannis · March 11, 2018

First Ten Pages Breakdown: The Lost Boys (1987)

Anthony Faust · December 8, 2017

© 2024 The Script Lab - An Industry Arts Company

Sign up for the TSL Newsletter

and get $50 off Final Draft 12

Stay up to date on the latest scripts & screenwriting articles.

Lady Bird Essay

Music and Coming-of-Age in Lady Bird

In her coming-of-age film, Lady Bird, Greta Gerwig uses music to illustrate the drama of growing up. Sudden musical cuts emphasize the contrasts between the unrealistic dreams of her teenage protagonist, Christine McPherson, and her family’s financial reality. Musical repetition underscores her transformation from adolescence to adulthood.

During scene changes, Gerwig juxtaposes youthfully idealistic scenes with serious, family scenes. On Thanksgiving, for example, Reel Big Fish’s “Snoop Dog, Baby,” plays loudly over Lady Bird and her friends laughing and dancing around the kitchen. The music cuts abruptly, mid-lyric, as her friends’ car pulls away, and the scene jumps to a more meaningful conversation between Lady Bird and Shelly. Shelly tells Lady Bird that Marion missed her at Thanksgiving dinner, and explains the challenges of her relationship with her own mother. The contrast between the two scenes–loud, carefree kids versus a deeper conversation about family–is emphasized through volume and intensity, with the transition from loud giggling and a fast-paced song to crickets and Shelly’s quiet speaking voice. It reflects the film’s larger theme: Lady Bird grappling with the guilt of turning a blind eye to her family’s feelings and sacrifices in order to have teenage fun. This theme reoccurs later when Justin Timberlake’s “Cry Me A River” plays at Jenna’s party. Mid-lyric, the song cuts while the scene switches to Lady Bird in the bathroom the next day, inspecting a bottle of pills. A moment later, Lady Bird asks her mother, Marion, whether her father’s depressed. Yet again, music adds excitement to the loud party scene, while the quiet absence of music heightens the drama in the intimate family scene. Throughout the film, Lady Bird switches back and forth between adolescent concerns–friends, boys, and college–grown-up responsibilities–family, finances, and the limits of her dreams. Music dramatizes the contrast: the music-filled experiences she wants to have versus the silence of stark realism in her mother’s presence.

The film also demonstrates Lady Bird’s growing maturity with song repetition. “Crash Into Me” by the Dave Matthews Band plays twice. First, Lady Bird and Julie listen to it while crying over heartbreaks; later, Kyle plays it in the car with Lady Bird on their way to prom. When Kyle says he hates the song, she disagrees and then ditches him to head to prom with Julie. The song plays again over a montage of them at the dance. In this scene, she speaks her deeper truth for the first time and realizes her priorities have been wrong. She had been putting boys first and ignoring Julie, her only true and consistent friend. The second time the song plays, Julie and Lady Bird have reconciled, and they are finally comfortable in their own skins. The song is a symbolic reminder of their loyalty to each other–they’ve both cried and danced to it. Similarly, John Hartford’s “This Eve of Parting” plays twice: first, over a montage of Sacramento as Marion drives home from work; second, at the end of the film as Lady Bird leaves for college. The same song paints two very different scenes: the first, a mother who dreams only of a healthy and financially stable home, which she reaches at the song’s end; the second, a daughter leaving that home to realize her dream of heading to college on the East Coast. Over lyrics like “when both our minds are warped with parting,” the two head off in entirely different directions. The song underscores the film’s broader arc–Lady Bird’s transition from carefree teenager to independent young adult.

Works Cited

Lady Bird . Directed by Greta Gerwig, Universal Studios, A24, Focus Features. 2017.

Thompson, Kristin, and David Bordwell. Film History: An Introduction . New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994.

- April 13 Legacy Day Unites Community

- April 12 Baseball Defeated by DeLaSalle During Exclusive Night Game

- April 5 Ammanuel Challenges Students on Shoe Competition

The Spectrum

ARTS & CULTURE

Lady Bird Holds Important Life Lessons

Coming of age film speaks to teenagers

Jenna Thrasher , Staff Writer | April 17, 2020

- Jenna Thrasher

The movie, Lady Bird , changed my life when it first came out two years ago, and it feels even more relevant today. This coming of age film addresses a lot of topics that we might all be dealing with right now: arguing with parents, applying for college, feeling out of place, falling in love, etc. Saoirse Ronan plays Christine “Lady Bird” McPherson, a senior at a Catholic High School. Lady Bird is desperate to leave her hometown of Sacramento, which she has dubbed the “Midwest of California,” and head to the East Coast, where she believes culture lives.

The film is centered around the complex yet loving relationship between Lady Bird and her mother, portrayed by Laurie Metcalf. The theme of class struggle is the main point of tension between Lady Bird and her mother. Lady Bird describes herself as someone who “lives on the wrong side of the tracks,” amidst her wealthy peers at school. There are few films that truly explore mother-daughter relationships, especially ones that can resonate with an audience through the power of empathy.

This movie changed my life when it first came out two years ago, and it feels even more relevant and powerful today. To be completely honest, most of the teen movies of the past decade have been kind of cheesy. I haven’t found any ones that I’ve been able to empathize with or appreciate. Lady Bird is the complete opposite because it is extremely sophisticated in the way it is vulnerable to the audience. It does not shy away from awkward, heart-breaking, or unpleasant scenes.

The film does not end in a particularly satisfying way; not everything is wrapped up into a neat little bow. However, the lesson that Lady Bird learns is one that we can all take into our own lives: appreciating where we come from. Like Lady Bird, I too want to leave home for New York. However, in wanting that escape, I have sometimes forgotten to enjoy Minnesota. As teenagers, we are all so close to becoming adults, going off to college, and “starting” our own lives that we forget that there is beauty in living in the present.

- movie review

Swift & Kelce: In Their Lover Era

Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour is Hitting the Big Screen

Squeeze in More Summer at State Fair

Books That Play With Time

Band & Orchestra Concert Review

Art-A-Whirl Proves Successful

Edina Art Fair Stirs Excitement

Writing Club Fosters Expression

Daisy Jones & the 6 Sparks Nostalgia

The News of The Blake School Since 1916

Comments (1)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Jim Mahoney • Apr 20, 2020 at 11:21 am

Incredible film. Laurie Metcalf is terrific (and often heartbreaking) as Lady Bird’s mother. Greta Gerwig is an amazing filmmaker who embraces complexity and builds resonant and believable characters– I also recommend Little Women (also starring Ronan). Thanks, Jenna!

Religion and Politics

A Project of the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics

Washington University in St. Louis

The Hopeful, Ordinary Catholicism of Lady Bird

- --> --> -->

- Email Email -->

(A24) Saoirse Ronan stars in the film Lady Bird .

A Catholic movie is almost instantly recognizable, even to people who have never stepped inside a church. Crucifixes, clerical collars, and the host are familiar props, as are ceremonies such as Communion and the procession. Think of Carl Theodor Dreyer’s iconic and sublime The Passion of Joan of Arc from 1928, or more recently, the wild horror of The Exorcist and the melodrama of The Passion of the Christ . All of them trade in a language that, accurately or not, reflects a popular understanding of the religion.

“Catholic characters, spaces, and rituals have been stock features in popular films since the silent picture era,” writes the University of Utah historian Colleen McDannell. “An intensely visual religion with a well-defined ritual and authority system, Catholicism lends itself to the drama and pageantry—the iconography—of film.”

Catholicism’s presence in films goes beyond the visuals. Such a rich theological and historical tradition can bear grand themes: loss, redemption, mystery, grace. The best recent example is Pawel Pawlikowski’s sublime Ida , where the washed-out, grayscale color palette illuminates the ripped and guilty edges of post-Holocaust Christianity.

Lady Bird , Greta Gerwig’s directorial debut, is a different kind of Catholic film. The story follows a young woman who calls herself Lady Bird (played by Saoirse Ronan), about to graduate from a Catholic high school in Sacramento. The movie has been nominated for several Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Director.

Everything about the movie seems small. Sacramento feels claustrophobic, the school is unremarkable, and even Christine’s self-chosen name, Lady Bird, feels like exactly the sort of thing a teenager doesn’t realize sounds silly. Gerwig the director doesn’t dramatize, however: The chapel settings and nuns’ habits are as ordinary and undramatic as everything else about the world Lady Bird is desperate to escape. Her teachers—many of them members of religious orders—are neither stereotypical scolds nor sinister figures. Instead, they are presented as normal, kind people with lives of their own and extraordinary patience for the teenagers they work with.

The film is a coming-of-age tale for a young woman deciding who she wants to be, and often hurting people in the process. Lady Bird’s mother, played by Laurie Metcalf, feels the rejection keenly, saying, “Whatever we give you, it’s never enough. It’s never enough.” The fact that Lady Bird is in Catholic school at all is a signal of how cherished she is. Her family has scrimped to send her there because her mother says the local high school is dangerous. But the school’s uniforms don’t quite do their job of obscuring class. On and off campus, everyone can still see the wealthy students’ expensive cars and nice haircuts and large houses.

Lady Bird tries and fails to join this world. She spends Thanksgiving with her first boyfriend’s large, wealthy family, and later tries to join a clique led by a popular girl, Jenna, who hems her skirts a good 5 inches too short and spends her afternoons in her parents’ backyard pool. The jig is up when Jenna tries to stop by Lady Bird’s house and finds that she lied about which side of the tracks she lives on. When Lady Bird asks if they can still be friends, Jenna says that as long as Lady Bird is still dating one of her friends, “I guess I’ll see you around.” Lady Bird doesn’t understand yet that this is not acceptance, much less friendship.

To understand how the movie would be perceived by Catholics, I called Sister Rose Pacatte, a nun who writes a popular review series called “Sister Rose at the Movies” for Patheos . She’s also the founding director of the Pauline Center for Media Studies, an arm of the Daughters of St. Paul. I asked her what made Lady Bird different from other movies with strong Catholic settings, and she said, “Because it was real.” She reminded me of a scene where Lady Bird and a pal are lounging on the floor at school, with their feet up against the wall, snacking on the (unconsecrated) Communion wafers. “They’re kids,” she said. “Of course, they’re doing that. It’s totally authentic.”

That authenticity, she went on to say, is the real quality that makes the movie Catholic. She told me that she went to a screening of Annabelle: Creation , a horror movie about a demon-infested doll who takes advantage of a botched exorcism to find a human host. After the screening, she asked the director if he’d brought on a consultant or a priest to make the film accurate to exorcism rituals, or if he’d just watched a bunch of other exorcism films. It was the latter. The Bible pages papering the walls in the movie, a trope that appeared in both The Omen and The Body , had tipped her off.

It’s a similar tendency towards making things “look right” that constantly trips up Lady Bird. She wants to go to the East Coast college her family can’t afford because it seems like what college is supposed to be like. “I want to go where culture is,” she says. “New York, or at least Connecticut or New Hampshire where writers live in the woods.” Her bedroom walls are covered in quotes and drawings, and she runs for class president mostly just because she can. One of her teachers puts it very nicely as suggests Lady Bird try out for the school play: “You seem to have a performative streak.”

Yet despite all this longing for something—anything—to happen, Lady Bird is totally blind to the fact that, right around her, all the time, important things are happening. Her mother works double shifts at a mental health center where one of her teachers seeks help. Her father loses his job and income in a blow that’s compounded by having to compete on the job market with his son. Her first boyfriend is coming to terms with his own homosexuality, and what his family will think—an agony she doesn’t see until he breaks down sobbing in her arms. Lady Bird herself wears a pink cast throughout the movie, which she earned when she jumped out of a moving car to end a fight with her mother. The stories are there. She just doesn’t know how to recognize them.

Even in the grand, religious chapel where she and the other students have their assemblies, she isn’t paying attention. Surrounded by symbols of sacrifice and grace in the form of stained glass, crucifixes, altars, and worn wooden pews, she and her classmates whisper and one reaches over during prayer to pull another’s hair. To anyone who spends a lot of time around teenagers, it’s pretty much perfect.

It’s not until the end of the movie that you see the perception start to shift for Lady Bird. She’s made it to New York, where no one around her gets why Sacramento felt small and stifling. No one knows her mom called her Christine, so there’s no reason to call herself Lady Bird. Isolated and bewildered, she gets dangerously drunk at a dorm room party.

When she wakes up in a hospital recovery room, she sees a small boy with a bandage on his head, sitting in his mother’s arms. It’s as if she can suddenly see all the injuries that were invisible to her before: her family and friends and teachers who had their own struggles. She walks home through the city, stopping in a church to listen to the choir sing something she’s heard probably hundreds of times before. You can see her hearing it for the first time.

What’s unique about this moment is that it’s not about the church or the choir. The movie doesn’t proselytize. Gerwig, who grew up Unitarian Universalist but attended Catholic school, appears to have too much respect for Catholicism, and religious tradition in general, to let Lady Bird or the audience off that easy. Instead, she shows a young woman learning why the adults around her were working so very, very hard to be nice. The symbolic touchpoints of the religion that were in the background the whole time—forgiveness, grace, and compassion, as well as their mirrors of guilt, shame, and self-flagellation—make sense only once they’re no longer background noise.

In an interview with Terry Gross on NPR, Gerwig said that one of her inspirations for the film was reading about the lives of saints, especially their imperfections. She says, “I was always interested in who they were as people and that they both were these people who were divinely inspired, but they were also kind of just annoying teenagers.”

Ultimately, Lady Bird is a love song to growing up and to growing out of your own selfishness. She isn’t a saint, but neither is anyone else. They’re all just trying to be good, which is as difficult as ever.

Xarissa Holdaway works at Postlight, a digital product studio in New York City.

R&P Newsletter

Sign up to receive our newsletter and occasional announcements.

America's Education News Source

Copyright 2024 The 74 Media, Inc

- Cyberattack

- absenteeism

- Future of High School

- Artificial Intelligence

- science of reading

Inside ‘Lady Bird’: Greta Gerwig Says She Wanted to Write a Different Kind of Love Letter to Catholic School — and It Might Just Win Her an Oscar

Untangle Your Mind!

Sign up for our free newsletter and start your day with clear-headed reporting on the latest topics in education.

74 Million Reasons to Give

Support The 74’s year-end campaign with a tax-exempt donation and invest in our future.

Most Popular

Nearly a third of north carolina child care providers to close within months, a cautionary ai tale: why ibm’s dazzling watson supercomputer made a lousy tutor, improving america’s schools: why it’s long past time to rethink curriculum, there’s already a solution to the stem crisis: it’s in high schools, school success stories: here’s what happened when charters teamed up with hbcus.

Leading up to the 90th Academy Awards, The 74 shares three education films that have been nominated for Oscars.

I t’s easy for filmmakers to make fun of Catholic school. That’s why writer and director Greta Gerwig decided to do something very different.

Gerwig has said that her film Lady Bird may be the only cinematic love letter to Catholic education. It’s the story about a year in the life of high school senior Christine (Lady Bird) McPherson, documenting her triumphs and travails as she goes to class, applies to college, and fights and makes up with the people she loves.

The film has already received a slew of awards, including several Oscar nominations for writing, acting, directing, and best picture.

“Why do you think a movie about a 17-year-old pink-haired girl in a Catholic school in Sacramento is resonating with so many people?” Stephen Colbert asked Lady Bird ’s lead actress, Saoirse Ronan.

“You’re watching this person figure themselves out,” Ronan responded. “It’s human. It’s genderless, in a way.”

Gerwig is not Catholic, but she attended St. Francis Catholic high school in Sacramento, California, which served as the inspiration for Lady Bird’s all-girls school, Immaculate Heart (nicknamed by students Immaculate Fart).

Gerwig said she loved her Catholic school experience, especially the teachers, both religious and lay people, who showed such care for their students. “There were priests and nuns who were just compassionate and funny and empathetic and thoughtful, and they really engaged with the students as people, not figureheads,” Gerwig said in an interview with Religion News Service .

This inspiration is evident in the film, particularly in exchanges with principal Sister Sarah Joan, who notices Lady Bird’s need for identity and attention in a way other characters don’t. (“You can’t do anything unless you’re the center of attention, can you?” Lady Bird’s best friend, Julie, yells at her during one heated fight after school.)

Sister Sarah Joan sits Lady Bird down in her office after reading her college essay, complimenting her on the careful, loving way she’s written about her hometown.

“Sure, I guess I pay attention,” says Lady Bird, who has spent much of the film talking about how eager she is to escape Sacramento for a more “cultured” place on the East Coast.

“Don’t you think maybe they are the same thing, love and attention?” Sister Sarah Joan asks.

While a love letter, the film offers subtle critiques of Catholic school. Dialogue around the LGBT community was stifled in the Catholic community in 2002, the year in which the movie is set. In one scene, Lady Bird finds herself holding her former boyfriend, Danny, as he sobs, begging her not to tell anyone he’s gay. Gerwig said she doesn’t remember anyone who was openly gay in her school. “You couldn’t be. You would be beaten up, or worse,” she said. “Thank God that’s changed.”

Another central tension in the film is the struggle for female identity in a patriarchal church. A montage of a back-to-school Mass kicks off the movie, coupled with a voice-over from a priest reciting the Sign of the Cross, “In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.”

“As a teenage girl, you think: ‘Well, where am I in those people? I’m not a father, son, or holy spirit.’ I guess you could strive to be the Virgin Mary, but that seems to be off to the side, not the main event, somehow. It’s a feeling of ‘Where do I fit in this patriarchal structure?’ ” Gerwig said in the film’s production notes. “Lady Bird is running into this problem and railing against it.”

Lady Bird tries on several identities throughout the film: changing her name, dyeing her hair, taking up acting, ditching her best friend for the popular girl in school, returning to her best friend in an epic prom-night reunion, writing her boyfriends’ names on her wall, painting over those names, going off to college, denying that she’s from Sacramento, and then calling her parents when a church choir reminds her how much she misses home.

“Senior year burns brightly and is also disappearing as quickly as it emerges,” Gerwig said. “There is a certain vividness in worlds that are coming to an end. … This is true for both parents and children. It is something beautiful that you never appreciated and ends just as you come to understand it.”

Watch the trailer:

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Articles by Kate Stringer

We want our stories to be shared as widely as possible — for free.

Please view The 74's republishing terms.

By Kate Stringer

This story first appeared at The 74 , a nonprofit news site covering education. Sign up for free newsletters from The 74 to get more like this in your inbox.

On The 74 Today

Philadelphia, Here I Come!

Brian friel, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.