- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

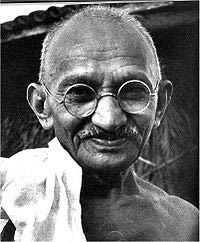

Mahatma Gandhi

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 6, 2019 | Original: July 30, 2010

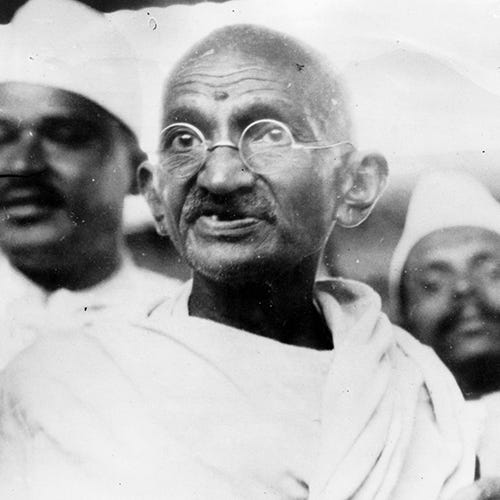

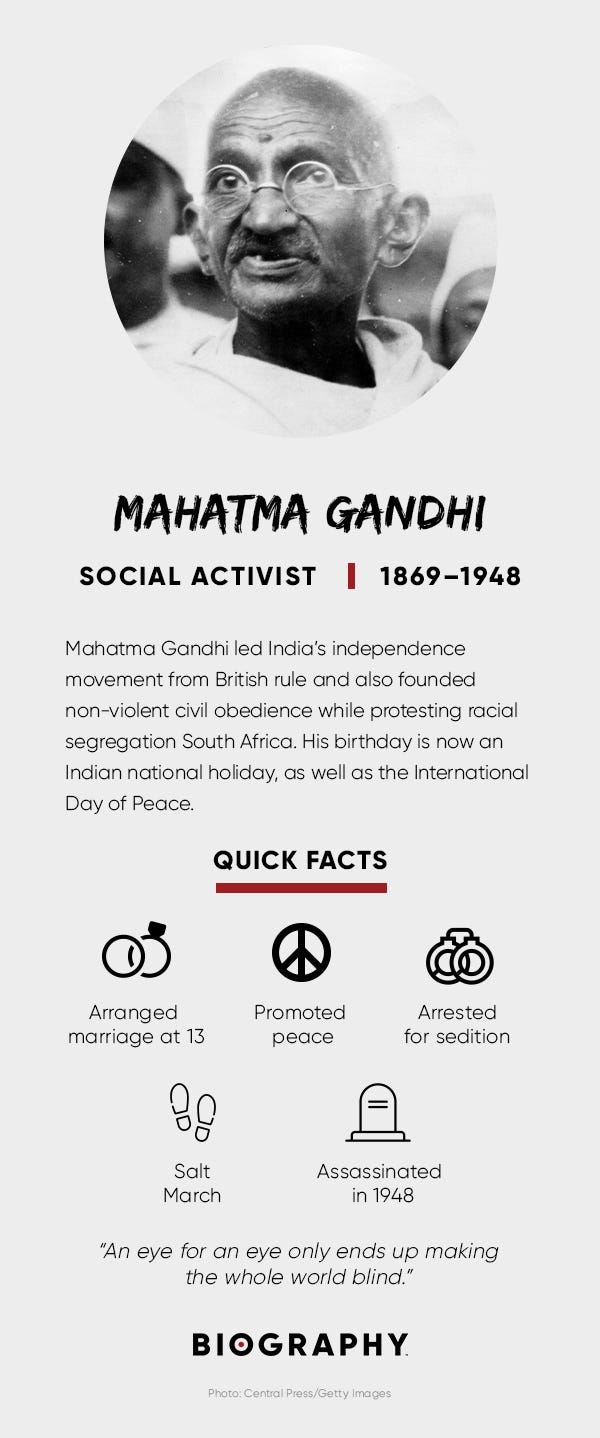

Revered the world over for his nonviolent philosophy of passive resistance, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was known to his many followers as Mahatma, or “the great-souled one.” He began his activism as an Indian immigrant in South Africa in the early 1900s, and in the years following World War I became the leading figure in India’s struggle to gain independence from Great Britain. Known for his ascetic lifestyle–he often dressed only in a loincloth and shawl–and devout Hindu faith, Gandhi was imprisoned several times during his pursuit of non-cooperation, and undertook a number of hunger strikes to protest the oppression of India’s poorest classes, among other injustices. After Partition in 1947, he continued to work toward peace between Hindus and Muslims. Gandhi was shot to death in Delhi in January 1948 by a Hindu fundamentalist.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, at Porbandar, in the present-day Indian state of Gujarat. His father was the dewan (chief minister) of Porbandar; his deeply religious mother was a devoted practitioner of Vaishnavism (worship of the Hindu god Vishnu), influenced by Jainism, an ascetic religion governed by tenets of self-discipline and nonviolence. At the age of 19, Mohandas left home to study law in London at the Inner Temple, one of the city’s four law colleges. Upon returning to India in mid-1891, he set up a law practice in Bombay, but met with little success. He soon accepted a position with an Indian firm that sent him to its office in South Africa. Along with his wife, Kasturbai, and their children, Gandhi remained in South Africa for nearly 20 years.

Did you know? In the famous Salt March of April-May 1930, thousands of Indians followed Gandhi from Ahmadabad to the Arabian Sea. The march resulted in the arrest of nearly 60,000 people, including Gandhi himself.

Gandhi was appalled by the discrimination he experienced as an Indian immigrant in South Africa. When a European magistrate in Durban asked him to take off his turban, he refused and left the courtroom. On a train voyage to Pretoria, he was thrown out of a first-class railway compartment and beaten up by a white stagecoach driver after refusing to give up his seat for a European passenger. That train journey served as a turning point for Gandhi, and he soon began developing and teaching the concept of satyagraha (“truth and firmness”), or passive resistance, as a way of non-cooperation with authorities.

The Birth of Passive Resistance

In 1906, after the Transvaal government passed an ordinance regarding the registration of its Indian population, Gandhi led a campaign of civil disobedience that would last for the next eight years. During its final phase in 1913, hundreds of Indians living in South Africa, including women, went to jail, and thousands of striking Indian miners were imprisoned, flogged and even shot. Finally, under pressure from the British and Indian governments, the government of South Africa accepted a compromise negotiated by Gandhi and General Jan Christian Smuts, which included important concessions such as the recognition of Indian marriages and the abolition of the existing poll tax for Indians.

In July 1914, Gandhi left South Africa to return to India. He supported the British war effort in World War I but remained critical of colonial authorities for measures he felt were unjust. In 1919, Gandhi launched an organized campaign of passive resistance in response to Parliament’s passage of the Rowlatt Acts, which gave colonial authorities emergency powers to suppress subversive activities. He backed off after violence broke out–including the massacre by British-led soldiers of some 400 Indians attending a meeting at Amritsar–but only temporarily, and by 1920 he was the most visible figure in the movement for Indian independence.

Leader of a Movement

As part of his nonviolent non-cooperation campaign for home rule, Gandhi stressed the importance of economic independence for India. He particularly advocated the manufacture of khaddar, or homespun cloth, in order to replace imported textiles from Britain. Gandhi’s eloquence and embrace of an ascetic lifestyle based on prayer, fasting and meditation earned him the reverence of his followers, who called him Mahatma (Sanskrit for “the great-souled one”). Invested with all the authority of the Indian National Congress (INC or Congress Party), Gandhi turned the independence movement into a massive organization, leading boycotts of British manufacturers and institutions representing British influence in India, including legislatures and schools.

After sporadic violence broke out, Gandhi announced the end of the resistance movement, to the dismay of his followers. British authorities arrested Gandhi in March 1922 and tried him for sedition; he was sentenced to six years in prison but was released in 1924 after undergoing an operation for appendicitis. He refrained from active participation in politics for the next several years, but in 1930 launched a new civil disobedience campaign against the colonial government’s tax on salt, which greatly affected Indian’s poorest citizens.

A Divided Movement

In 1931, after British authorities made some concessions, Gandhi again called off the resistance movement and agreed to represent the Congress Party at the Round Table Conference in London. Meanwhile, some of his party colleagues–particularly Mohammed Ali Jinnah, a leading voice for India’s Muslim minority–grew frustrated with Gandhi’s methods, and what they saw as a lack of concrete gains. Arrested upon his return by a newly aggressive colonial government, Gandhi began a series of hunger strikes in protest of the treatment of India’s so-called “untouchables” (the poorer classes), whom he renamed Harijans, or “children of God.” The fasting caused an uproar among his followers and resulted in swift reforms by the Hindu community and the government.

In 1934, Gandhi announced his retirement from politics in, as well as his resignation from the Congress Party, in order to concentrate his efforts on working within rural communities. Drawn back into the political fray by the outbreak of World War II , Gandhi again took control of the INC, demanding a British withdrawal from India in return for Indian cooperation with the war effort. Instead, British forces imprisoned the entire Congress leadership, bringing Anglo-Indian relations to a new low point.

Partition and Death of Gandhi

After the Labor Party took power in Britain in 1947, negotiations over Indian home rule began between the British, the Congress Party and the Muslim League (now led by Jinnah). Later that year, Britain granted India its independence but split the country into two dominions: India and Pakistan. Gandhi strongly opposed Partition, but he agreed to it in hopes that after independence Hindus and Muslims could achieve peace internally. Amid the massive riots that followed Partition, Gandhi urged Hindus and Muslims to live peacefully together, and undertook a hunger strike until riots in Calcutta ceased.

In January 1948, Gandhi carried out yet another fast, this time to bring about peace in the city of Delhi. On January 30, 12 days after that fast ended, Gandhi was on his way to an evening prayer meeting in Delhi when he was shot to death by Nathuram Godse, a Hindu fanatic enraged by Mahatma’s efforts to negotiate with Jinnah and other Muslims. The next day, roughly 1 million people followed the procession as Gandhi’s body was carried in state through the streets of the city and cremated on the banks of the holy Jumna River.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi was the primary leader of India’s independence movement and also the architect of a form of non-violent civil disobedience that would influence the world. He was assassinated by Hindu extremist Nathuram Godse.

(1869-1948)

Who Was Mahatma Gandhi?

Mahatma Gandhi was the leader of India’s non-violent independence movement against British rule and in South Africa who advocated for the civil rights of Indians. Born in Porbandar, India, Gandhi studied law and organized boycotts against British institutions in peaceful forms of civil disobedience. He was killed by a fanatic in 1948.

Early Life and Education

Indian nationalist leader Gandhi (born Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi) was born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, Kathiawar, India, which was then part of the British Empire.

Gandhi’s father, Karamchand Gandhi, served as a chief minister in Porbandar and other states in western India. His mother, Putlibai, was a deeply religious woman who fasted regularly.

Young Gandhi was a shy, unremarkable student who was so timid that he slept with the lights on even as a teenager. In the ensuing years, the teenager rebelled by smoking, eating meat and stealing change from household servants.

Although Gandhi was interested in becoming a doctor, his father hoped he would also become a government minister and steered him to enter the legal profession. In 1888, 18-year-old Gandhi sailed for London, England, to study law. The young Indian struggled with the transition to Western culture.

Upon returning to India in 1891, Gandhi learned that his mother had died just weeks earlier. He struggled to gain his footing as a lawyer. In his first courtroom case, a nervous Gandhi blanked when the time came to cross-examine a witness. He immediately fled the courtroom after reimbursing his client for his legal fees.

Gandhi’s Religion and Beliefs

Gandhi grew up worshiping the Hindu god Vishnu and following Jainism, a morally rigorous ancient Indian religion that espoused non-violence, fasting, meditation and vegetarianism.

During Gandhi’s first stay in London, from 1888 to 1891, he became more committed to a meatless diet, joining the executive committee of the London Vegetarian Society, and started to read a variety of sacred texts to learn more about world religions.

Living in South Africa, Gandhi continued to study world religions. “The religious spirit within me became a living force,” he wrote of his time there. He immersed himself in sacred Hindu spiritual texts and adopted a life of simplicity, austerity, fasting and celibacy that was free of material goods.

Gandhi in South Africa

After struggling to find work as a lawyer in India, Gandhi obtained a one-year contract to perform legal services in South Africa. In April 1893, he sailed for Durban in the South African state of Natal.

When Gandhi arrived in South Africa, he was quickly appalled by the discrimination and racial segregation faced by Indian immigrants at the hands of white British and Boer authorities. Upon his first appearance in a Durban courtroom, Gandhi was asked to remove his turban. He refused and left the court instead. The Natal Advertiser mocked him in print as “an unwelcome visitor.”

Nonviolent Civil Disobedience

A seminal moment occurred on June 7, 1893, during a train trip to Pretoria, South Africa, when a white man objected to Gandhi’s presence in the first-class railway compartment, although he had a ticket. Refusing to move to the back of the train, Gandhi was forcibly removed and thrown off the train at a station in Pietermaritzburg.

Gandhi’s act of civil disobedience awoke in him a determination to devote himself to fighting the “deep disease of color prejudice.” He vowed that night to “try, if possible, to root out the disease and suffer hardships in the process.”

From that night forward, the small, unassuming man would grow into a giant force for civil rights. Gandhi formed the Natal Indian Congress in 1894 to fight discrimination.

Gandhi prepared to return to India at the end of his year-long contract until he learned, at his farewell party, of a bill before the Natal Legislative Assembly that would deprive Indians of the right to vote. Fellow immigrants convinced Gandhi to stay and lead the fight against the legislation. Although Gandhi could not prevent the law’s passage, he drew international attention to the injustice.

After a brief trip to India in late 1896 and early 1897, Gandhi returned to South Africa with his wife and children. Gandhi ran a thriving legal practice, and at the outbreak of the Boer War, he raised an all-Indian ambulance corps of 1,100 volunteers to support the British cause, arguing that if Indians expected to have full rights of citizenship in the British Empire, they also needed to shoulder their responsibilities.

In 1906, Gandhi organized his first mass civil-disobedience campaign, which he called “Satyagraha” (“truth and firmness”), in reaction to the South African Transvaal government’s new restrictions on the rights of Indians, including the refusal to recognize Hindu marriages.

After years of protests, the government imprisoned hundreds of Indians in 1913, including Gandhi. Under pressure, the South African government accepted a compromise negotiated by Gandhi and General Jan Christian Smuts that included recognition of Hindu marriages and the abolition of a poll tax for Indians.

Return to India

In 1915 Gandhi founded an ashram in Ahmedabad, India, that was open to all castes. Wearing a simple loincloth and shawl, Gandhi lived an austere life devoted to prayer, fasting and meditation. He became known as “Mahatma,” which means “great soul.”

Opposition to British Rule in India

In 1919, with India still under the firm control of the British, Gandhi had a political reawakening when the newly enacted Rowlatt Act authorized British authorities to imprison people suspected of sedition without trial. In response, Gandhi called for a Satyagraha campaign of peaceful protests and strikes.

Violence broke out instead, which culminated on April 13, 1919, in the Massacre of Amritsar. Troops led by British Brigadier General Reginald Dyer fired machine guns into a crowd of unarmed demonstrators and killed nearly 400 people.

No longer able to pledge allegiance to the British government, Gandhi returned the medals he earned for his military service in South Africa and opposed Britain’s mandatory military draft of Indians to serve in World War I.

Gandhi became a leading figure in the Indian home-rule movement. Calling for mass boycotts, he urged government officials to stop working for the Crown, students to stop attending government schools, soldiers to leave their posts and citizens to stop paying taxes and purchasing British goods.

Rather than buy British-manufactured clothes, he began to use a portable spinning wheel to produce his own cloth. The spinning wheel soon became a symbol of Indian independence and self-reliance.

Gandhi assumed the leadership of the Indian National Congress and advocated a policy of non-violence and non-cooperation to achieve home rule.

After British authorities arrested Gandhi in 1922, he pleaded guilty to three counts of sedition. Although sentenced to a six-year imprisonment, Gandhi was released in February 1924 after appendicitis surgery.

He discovered upon his release that relations between India’s Hindus and Muslims devolved during his time in jail. When violence between the two religious groups flared again, Gandhi began a three-week fast in the autumn of 1924 to urge unity. He remained away from active politics during much of the latter 1920s.

Gandhi and the Salt March

Gandhi returned to active politics in 1930 to protest Britain’s Salt Acts, which not only prohibited Indians from collecting or selling salt—a dietary staple—but imposed a heavy tax that hit the country’s poorest particularly hard. Gandhi planned a new Satyagraha campaign, The Salt March , that entailed a 390-kilometer/240-mile march to the Arabian Sea, where he would collect salt in symbolic defiance of the government monopoly.

“My ambition is no less than to convert the British people through non-violence and thus make them see the wrong they have done to India,” he wrote days before the march to the British viceroy, Lord Irwin.

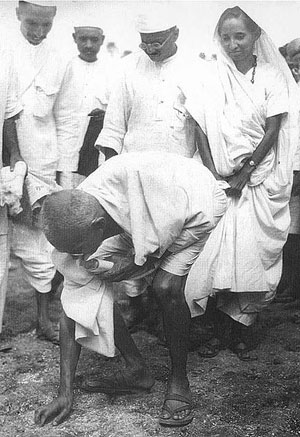

Wearing a homespun white shawl and sandals and carrying a walking stick, Gandhi set out from his religious retreat in Sabarmati on March 12, 1930, with a few dozen followers. By the time he arrived 24 days later in the coastal town of Dandi, the ranks of the marchers swelled, and Gandhi broke the law by making salt from evaporated seawater.

The Salt March sparked similar protests, and mass civil disobedience swept across India. Approximately 60,000 Indians were jailed for breaking the Salt Acts, including Gandhi, who was imprisoned in May 1930.

Still, the protests against the Salt Acts elevated Gandhi into a transcendent figure around the world. He was named Time magazine’s “Man of the Year” for 1930.

Gandhi was released from prison in January 1931, and two months later he made an agreement with Lord Irwin to end the Salt Satyagraha in exchange for concessions that included the release of thousands of political prisoners. The agreement, however, largely kept the Salt Acts intact. But it did give those who lived on the coasts the right to harvest salt from the sea.

Hoping that the agreement would be a stepping-stone to home rule, Gandhi attended the London Round Table Conference on Indian constitutional reform in August 1931 as the sole representative of the Indian National Congress. The conference, however, proved fruitless.

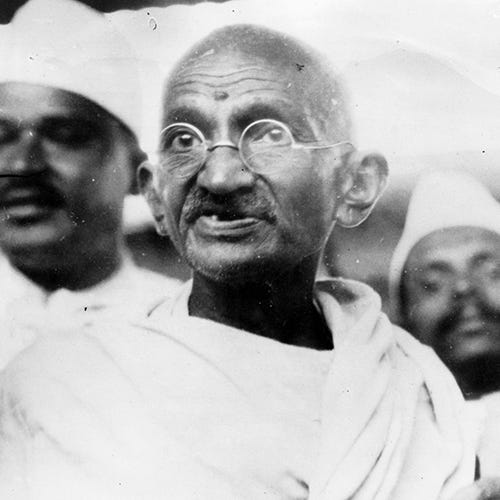

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S MAHATMA GANDHI FACT CARD

Protesting "Untouchables" Segregation

Gandhi returned to India to find himself imprisoned once again in January 1932 during a crackdown by India’s new viceroy, Lord Willingdon. He embarked on a six-day fast to protest the British decision to segregate the “untouchables,” those on the lowest rung of India’s caste system, by allotting them separate electorates. The public outcry forced the British to amend the proposal.

After his eventual release, Gandhi left the Indian National Congress in 1934, and leadership passed to his protégé Jawaharlal Nehru . He again stepped away from politics to focus on education, poverty and the problems afflicting India’s rural areas.

India’s Independence from Great Britain

As Great Britain found itself engulfed in World War II in 1942, Gandhi launched the “Quit India” movement that called for the immediate British withdrawal from the country. In August 1942, the British arrested Gandhi, his wife and other leaders of the Indian National Congress and detained them in the Aga Khan Palace in present-day Pune.

“I have not become the King’s First Minister in order to preside at the liquidation of the British Empire,” Prime Minister Winston Churchill told Parliament in support of the crackdown.

With his health failing, Gandhi was released after a 19-month detainment in 1944.

After the Labour Party defeated Churchill’s Conservatives in the British general election of 1945, it began negotiations for Indian independence with the Indian National Congress and Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s Muslim League. Gandhi played an active role in the negotiations, but he could not prevail in his hope for a unified India. Instead, the final plan called for the partition of the subcontinent along religious lines into two independent states—predominantly Hindu India and predominantly Muslim Pakistan.

Violence between Hindus and Muslims flared even before independence took effect on August 15, 1947. Afterwards, the killings multiplied. Gandhi toured riot-torn areas in an appeal for peace and fasted in an attempt to end the bloodshed. Some Hindus, however, increasingly viewed Gandhi as a traitor for expressing sympathy toward Muslims.

Gandhi’s Wife and Kids

At the age of 13, Gandhi wed Kasturba Makanji, a merchant’s daughter, in an arranged marriage. She died in Gandhi’s arms in February 1944 at the age of 74.

In 1885, Gandhi endured the passing of his father and shortly after that the death of his young baby.

In 1888, Gandhi’s wife gave birth to the first of four surviving sons. A second son was born in India 1893. Kasturba gave birth to two more sons while living in South Africa, one in 1897 and one in 1900.

Assassination of Mahatma Gandhi

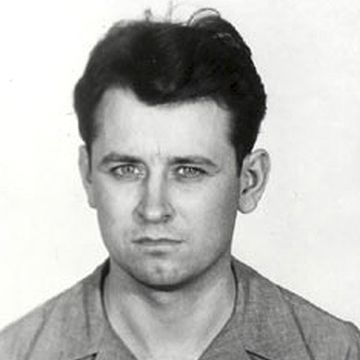

On January 30, 1948, 78-year-old Gandhi was shot and killed by Hindu extremist Nathuram Godse, who was upset at Gandhi’s tolerance of Muslims.

Weakened from repeated hunger strikes, Gandhi clung to his two grandnieces as they led him from his living quarters in New Delhi’s Birla House to a late-afternoon prayer meeting. Godse knelt before the Mahatma before pulling out a semiautomatic pistol and shooting him three times at point-blank range. The violent act took the life of a pacifist who spent his life preaching nonviolence.

Godse and a co-conspirator were executed by hanging in November 1949. Additional conspirators were sentenced to life in prison.

Even after Gandhi’s assassination, his commitment to nonviolence and his belief in simple living — making his own clothes, eating a vegetarian diet and using fasts for self-purification as well as a means of protest — have been a beacon of hope for oppressed and marginalized people throughout the world.

Satyagraha remains one of the most potent philosophies in freedom struggles throughout the world today. Gandhi’s actions inspired future human rights movements around the globe, including those of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. in the United States and Nelson Mandela in South Africa.

Martin Luther King

"],["

Winston Churchill

Nelson Mandela

"]]" tml-render-layout="inline">

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Mahatma Gandhi

- Birth Year: 1869

- Birth date: October 2, 1869

- Birth City: Porbandar, Kathiawar

- Birth Country: India

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Mahatma Gandhi was the primary leader of India’s independence movement and also the architect of a form of non-violent civil disobedience that would influence the world. Until Gandhi was assassinated in 1948, his life and teachings inspired activists including Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela.

- Civil Rights

- Astrological Sign: Libra

- University College London

- Samaldas College at Bhavnagar, Gujarat

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- As a young man, Mahatma Gandhi was a poor student and was terrified of public speaking.

- Gandhi formed the Natal Indian Congress in 1894 to fight discrimination.

- Gandhi was assassinated by Hindu extremist Nathuram Godse, who was upset at Gandhi’s tolerance of Muslims.

- Gandhi's non-violent civil disobedience inspired future world leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela.

- Death Year: 1948

- Death date: January 30, 1948

- Death City: New Delhi

- Death Country: India

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Mahatma Gandhi Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/political-figures/mahatma-gandhi

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: September 4, 2019

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- An eye for an eye only ends up making the whole world blind.

- Victory attained by violence is tantamount to a defeat, for it is momentary.

- Religions are different roads converging to the same point. What does it matter that we take different roads, so long as we reach the same goal? In reality, there are as many religions as there are individuals.

- The weak can never forgive. Forgiveness is the attribute of the strong.

- To call woman the weaker sex is a libel; it is man's injustice to woman.

- Truth alone will endure, all the rest will be swept away before the tide of time.

- A man is but the product of his thoughts. What he thinks, he becomes.

- There are many things to do. Let each one of us choose our task and stick to it through thick and thin. Let us not think of the vastness. But let us pick up that portion which we can handle best.

- An error does not become truth by reason of multiplied propagation, nor does truth become error because nobody sees it.

- For one man cannot do right in one department of life whilst he is occupied in doing wrong in any other department. Life is one indivisible whole.

- If we are to reach real peace in this world and if we are to carry on a real war against war, we shall have to begin with children.

Assassinations

The Manhunt for John Wilkes Booth

Indira Gandhi

Alexei Navalny

Martin Luther King Jr.

James Earl Ray

Malala Yousafzai

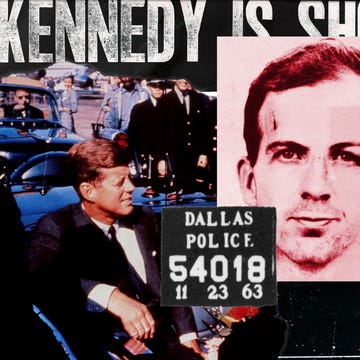

Who Killed JFK? You Won’t Believe Us Anyway

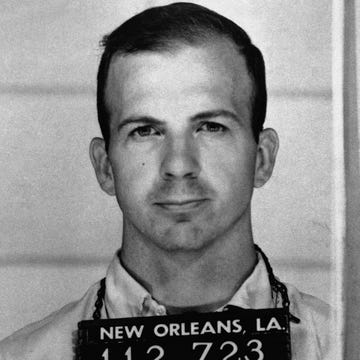

Lee Harvey Oswald

John F. Kennedy

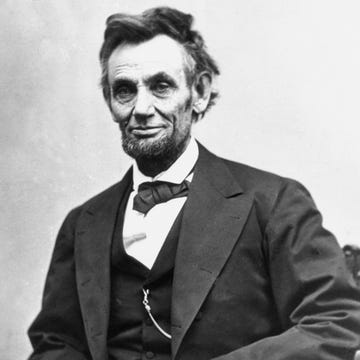

Abraham Lincoln

Talk to our experts

1800-120-456-456

- Mahatma Gandhi Biography and Political Career

Biography of Mahatma Gandhi (Father of Nation)

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi , more popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi . His birth place was in the small city of Porbandar in Gujarat (October 2, 1869 - January 30, 1948). Mahatma Gandhi's father's name was Karamchand Gandhi, and his mother's name was Putlibai Gandhi. He was a politician, social activist, Indian lawyer, and writer who became the prominent Leader of the nationwide surge movement against the British rule of India. He came to be known as the Father of The Nation. October 2, 2023, marks Gandhi Ji’s 154th birth anniversary , celebrated worldwide as International Day of Non-Violence, and Gandhi Jayanti in India.

Gandhi Ji was a living embodiment of non-violent protests (Satyagraha) to achieve independence from the British Empire's clutches and thereby achieve political and social progress. Gandhi Ji is considered ‘The Great Soul’ or ‘ The Mahatma ’ in the eyes of millions of his followers worldwide. His fame spread throughout the world during his lifetime and only increased after his demise. Mahatma Gandhi , thus, is the most renowned person on earth.

Education of Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi's education was a major factor in his development into one of the finest persons in history. Although he attended a primary school in Porbandar and received awards and scholarships there, his approach to his education was ordinary. Gandhi joined Samaldas College in Bhavnagar after passing his matriculation exams at the University of Bombay in 1887.

Gandhiji's father insisted he become a lawyer even though he intended to be a docto. During those days, England was the centre of knowledge, and he had to leave Smaladas College to pursue his father's desire. He was adamant about travelling to England despite his mother's objections and his limited financial resources.

Finally, he left for England in September 1888, where he joined Inner Temple, one of the four London Law Schools. In 1890, he also took the matriculation exam at the University of London.

When he was in London, he took his studies seriously and joined a public speaking practice group. This helped him get over his nervousness so he could practise law. Gandhi had always been passionate about assisting impoverished and marginalised people.

Mahatma Gandhi During His Youth

Gandhi was the youngest child of his father's fourth wife. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was the dewan Chief Minister of Porbandar, the then capital of a small municipality in western India (now Gujarat state) under the British constituency.

Gandhi's mother, Putlibai, was a pious religious woman.Mohandas grew up in Vaishnavism, a practice followed by the worship of the Hindu god Vishnu, along with a strong presence of Jainism, which has a strong sense of non-violence.Therefore, he took up the practice of Ahimsa (non-violence towards all living beings), fasting for self-purification, vegetarianism, and mutual tolerance between the sanctions of various castes and colours.

His adolescence was probably no stormier than most children of his age and class. Not until the age of 18 had Gandhi read a single newspaper. Neither as a budding barrister in India nor as a student in England nor had he shown much interest in politics. Indeed, he was overwhelmed by terrifying stage fright each time he stood up to read a speech at a social gathering or to defend a client in court.

In London, Gandhiji's vegetarianism missionary was a noteworthy occurrence. He became a member of the executive committee in joined the London Vegetarian Society. He also participated in several conferences and published papers in its journal. Gandhi met prominent Socialists, Fabians, and Theosophists like Edward Carpenter, George Bernard Shaw, and Annie Besant while dining at vegetarian restaurants in England.

Political Career of Mahatma Gandhi

When we talk about Mahatma Gandhi’s political career, in July 1894, when he was barely 25, he blossomed overnight into a proficient campaigner . He drafted several petitions to the British government and the Natal Legislature signed by hundreds of his compatriots. He could not prevent the passage of the bill but succeeded in drawing the attention of the public and the press in Natal, India, and England to the Natal Indian's problems.

He still was persuaded to settle down in Durban to practice law and thus organised the Indian community. The Natal Indian Congress was founded in 1894, and he became the unwearying secretary. He infused a solidarity spirit in the heterogeneous Indian community through that standard political organisation. He gave ample statements to the Government, Legislature, and media regarding Indian Grievances.

Finally, he got exposed to the discrimination based on his colour and race, which was pre-dominant against the Indian subjects of Queen Victoria in one of her colonies, South Africa.

Mahatma Gandhi spent almost 21 years in South Africa. But during that time, there was a lot of discrimination because of skin colour. Even on the train, he could not sit with white European people. But he refused to do so, got beaten up, and had to sit on the floor. So he decided to fight against these injustices, and finally succeeded after a lot of struggle.

It was proof of his success as a publicist that such vital newspapers as The Statesman, Englishman of Calcutta (now Kolkata) and The Times of London editorially commented on the Natal Indians' grievances.

In 1896, Gandhi returned to India to fetch his wife, Kasturba (or Kasturbai), their two oldest children, and amass support for the Indians overseas. He met the prominent leaders and persuaded them to address the public meetings in the centre of the country's principal cities.

Unfortunately for him, some of his activities reached Natal and provoked its European population. Joseph Chamberlain, the colonial secretary in the British Cabinet, urged Natal's government to bring the guilty men to proper jurisdiction, but Gandhi refused to prosecute his assailants. He said he believed the court of law would not be used to satisfy someone's vendetta.

Political Teacher of Mahatma Gandhi

Gopal Krishna Gokhale was one of the prominent political teachers and mentors of Mahatma Gandhi. Gokhale, a renowned Indian nationalist leader, played a significant role in shaping Gandhi's political ideology and approach to leadership. He emphasized the importance of nonviolence, constitutional methods, and constructive work in achieving social and political change. Gandhi referred to Gokhale as his political guru and credited him with influencing many of his principles and strategies in the Indian freedom struggle. Gokhale's teachings and guidance had a profound impact on Gandhi's development as a leader and advocate for India's independence.

Death of Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi's death was a tragic event and brought clouds of sorrow to millions of people. On the 29th of January, a man named Nathuram Godse came to Delhi with an automatic pistol. About 5 pm in the afternoon of the next day, he went to the Gardens of Birla house, and suddenly, a man from the crowd came out and bowed before him.

Then Godse fired three bullets at his chest and stomach, who was Mahatma Gandhi. Gandhi was in such a posture that he to the ground. During his death, he uttered: “Ram! Ram!” Although someone could have called the doctor in this critical situation during that time, no one thought of that, and Gandhiji died within half an hour.

How Shaheed Day is Celebrated at Gandhiji’s Samadhi (Raj Ghat)?

As Gandhiji died on January 30, the government of India declared this day as ‘Shaheed Diwas’.

On this day, the President, the Vice-President, the Prime Minister, and the Defence Minister every year gather at the Samadhi of Mahatma Gandhi at the Raj Ghat memorial in Delhi to pay tribute to Indian martyrs and Mahatma Gandhi, followed by a two-minute silence.

On this day, many schools host events where students perform plays and sing patriotic songs. Martyrs' Day is also observed on March 23 to honour the lives and sacrifices of Sukhdev Thapar, Shivaram Rajguru, and Bhagat Singh.

Gandhi believed it was his duty to defend India's rights. Mahatma Gandhi had a significant role in attaining India's independence from the British. He had an impact on many individuals and locations outside India. Gandhi also influenced Martin Luther King, and as a result, African-Americans now have equal rights. Peacefully winning India's independence, he altered the course of history worldwide.

FAQs on Mahatma Gandhi Biography and Political Career

1. What was people's reaction after Nathuram Godse killed Mahatma Gandhi?

When Nathuram Godse killed Mahatma Gandhi, people shouted to kill Nathuram. After killing Mahatma Gandhi, Nathuram Godse tried to kill himself but could not do so since the police seized his weapons and took him to jail. After that, Gandhiji's body was laid in the garden with a white cloth covered on his face. All the lights were turned off in honour of him. Then on the radio, honourable Prime minister Pandit Nehru Ji declared sadly that the Nation's Father was no more.

2. How vegetarianism impacted Mahatma Gandhi’s time in London?

During the three years he spent in England, he was in a great dilemma with personal and moral issues rather than academic ambitions.

The sudden transition from Porbandar's half-rural atmosphere to London's cosmopolitan life was not an easy task for him. And he struggled powerfully and painfully to adapt himself to Western food, dress, and etiquette, and he felt awkward.

His vegetarianism became a continual source of embarrassment and was like a curse to him; his friends warned him that it would disrupt his studies, health, and well-being. Fortunately, he came across a vegetarian restaurant and a book providing a well-defined defence of vegetarianism.

His missionary zeal for vegetarianism helped draw the pitifully shy youth out of his shell and gave him a new and robust personality. He also became a member of the London Vegetarian Society executive committee, contributing articles to its journal and attending conferences.

3. Who was the first person to write a biography of Mahatma Gandhi (Father of The Nation)?

Christian missionary Joseph Doke had written the first biography of Bapu. The best part is that Gandhiji had still not acquired the status of Mahatma when this biography was written.

4. Who was Gandhiji’s favorite writer?

Gandhiji’s favorite writer was Leo Tolstoy.

5. What is Mahatma Gandhi’s date of birth?

Mahatma Gandhi's date of birth is October 2, 1869. We celebrate every year on October 2nd as Mahatma Gandhi Jayanti.

6. Which are the famous Mahatma Gandhi books?

Mahatma Gandhi authored several influential books and writings that have left a lasting impact on the world. Some of his famous books include:

Autobiography

Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule

Satyagraha in South Africa

Young India

The Essential Gandhi

These books reflect Gandhi's deep commitment to nonviolence, truth, and social justice, making them essential reads for those interested in his life and principles.

Biography Online

Mahatma Gandhi Biography

Mahatma Gandhi was a prominent Indian political leader who was a leading figure in the campaign for Indian independence. He employed non-violent principles and peaceful disobedience as a means to achieve his goal. He was assassinated in 1948, shortly after achieving his life goal of Indian independence. In India, he is known as ‘Father of the Nation’.

“When I despair, I remember that all through history the ways of truth and love have always won. There have been tyrants, and murderers, and for a time they can seem invincible, but in the end they always fall. Think of it–always.”

Short Biography of Mahatma Gandhi

Around this time, he also studied the Bible and was struck by the teachings of Jesus Christ – especially the emphasis on humility and forgiveness. He remained committed to the Bible and Bhagavad Gita throughout his life, though he was critical of aspects of both religions.

Gandhi in South Africa

On completing his degree in Law, Gandhi returned to India, where he was soon sent to South Africa to practise law. In South Africa, Gandhi was struck by the level of racial discrimination and injustice often experienced by Indians. In 1893, he was thrown off a train at the railway station in Pietermaritzburg after a white man complained about Gandhi travelling in first class. This experience was a pivotal moment for Gandhi and he began to represent other Indias who experienced discrimination. As a lawyer he was in high demand and soon he became the unofficial leader for Indians in South Africa. It was in South Africa that Gandhi first experimented with campaigns of civil disobedience and protest; he called his non-violent protests satyagraha . Despite being imprisoned for short periods of time, he also supported the British under certain conditions. During the Boer war, he served as a medic and stretcher-bearer. He felt that by doing his patriotic duty it would make the government more amenable to demands for fair treatment. Gandhi was at the Battle of Spion serving as a medic. An interesting historical anecdote, is that at this battle was also Winston Churchill and Louis Botha (future head of South Africa) He was decorated by the British for his efforts during the Boer War and Zulu rebellion.

Gandhi and Indian Independence

After 21 years in South Africa, Gandhi returned to India in 1915. He became the leader of the Indian nationalist movement campaigning for home rule or Swaraj .

Gandhi also encouraged his followers to practise inner discipline to get ready for independence. Gandhi said the Indians had to prove they were deserving of independence. This is in contrast to independence leaders such as Aurobindo Ghose , who argued that Indian independence was not about whether India would offer better or worse government, but that it was the right for India to have self-government.

Gandhi also clashed with others in the Indian independence movement such as Subhas Chandra Bose who advocated direct action to overthrow the British.

Gandhi frequently called off strikes and non-violent protest if he heard people were rioting or violence was involved.

In 1930, Gandhi led a famous march to the sea in protest at the new Salt Acts. In the sea, they made their own salt, in violation of British regulations. Many hundreds were arrested and Indian jails were full of Indian independence followers.

“With this I’m shaking the foundations of the British Empire.”

– Gandhi – after holding up a cup of salt at the end of the salt march.

However, whilst the campaign was at its peak some Indian protesters killed some British civilians, and as a result, Gandhi called off the independence movement saying that India was not ready. This broke the heart of many Indians committed to independence. It led to radicals like Bhagat Singh carrying on the campaign for independence, which was particularly strong in Bengal.

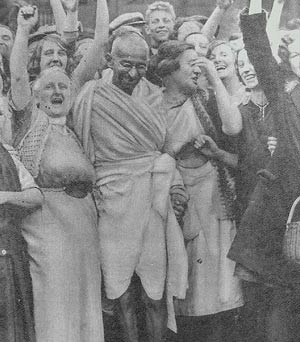

In 1931, Gandhi was invited to London to begin talks with the British government on greater self-government for India, but remaining a British colony. During his three month stay, he declined the government’s offer of a free hotel room, preferring to stay with the poor in the East End of London. During the talks, Gandhi opposed the British suggestions of dividing India along communal lines as he felt this would divide a nation which was ethnically mixed. However, at the summit, the British also invited other leaders of India, such as BR Ambedkar and representatives of the Sikhs and Muslims. Although the dominant personality of Indian independence, he could not always speak for the entire nation.

Gandhi’s humour and wit

During this trip, he visited King George in Buckingham Palace, one apocryphal story which illustrates Gandhi’s wit was the question by the king – what do you think of Western civilisation? To which Gandhi replied

“It would be a good idea.”

Gandhi wore a traditional Indian dress, even whilst visiting the king. It led Winston Churchill to make the disparaging remark about the half naked fakir. When Gandhi was asked if was sufficiently dressed to meet the king, Gandhi replied

“The king was wearing clothes enough for both of us.”

Gandhi once said he if did not have a sense of humour he would have committed suicide along time ago.

Gandhi and the Partition of India

After the war, Britain indicated that they would give India independence. However, with the support of the Muslims led by Jinnah, the British planned to partition India into two: India and Pakistan. Ideologically Gandhi was opposed to partition. He worked vigorously to show that Muslims and Hindus could live together peacefully. At his prayer meetings, Muslim prayers were read out alongside Hindu and Christian prayers. However, Gandhi agreed to the partition and spent the day of Independence in prayer mourning the partition. Even Gandhi’s fasts and appeals were insufficient to prevent the wave of sectarian violence and killing that followed the partition.

Away from the politics of Indian independence, Gandhi was harshly critical of the Hindu Caste system. In particular, he inveighed against the ‘untouchable’ caste, who were treated abysmally by society. He launched many campaigns to change the status of untouchables. Although his campaigns were met with much resistance, they did go a long way to changing century-old prejudices.

At the age of 78, Gandhi undertook another fast to try and prevent the sectarian killing. After 5 days, the leaders agreed to stop killing. But ten days later Gandhi was shot dead by a Hindu Brahmin opposed to Gandhi’s support for Muslims and the untouchables.

Gandhi and Religion

Gandhi was a seeker of the truth.

“In the attitude of silence the soul finds the path in a clearer light, and what is elusive and deceptive resolves itself into crystal clearness. Our life is a long and arduous quest after Truth.”

Gandhi said his great aim in life was to have a vision of God. He sought to worship God and promote religious understanding. He sought inspiration from many different religions: Jainism, Islam, Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism and incorporated them into his own philosophy.

On several occasions, he used religious practices and fasting as part of his political approach. Gandhi felt that personal example could influence public opinion.

“When every hope is gone, ‘when helpers fail and comforts flee,’ I find that help arrives somehow, from I know not where. Supplication, worship, prayer are no superstition; they are acts more real than the acts of eating, drinking, sitting or walking. It is no exaggeration to say that they alone are real, all else is unreal.”

– Gandhi Autobiography – The Story of My Experiments with Truth

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography of Mahatma Gandhi” , Oxford, UK. www.biographyonline.net 12th Jan 2011. Last updated 1 Feb 2020.

The Essential Gandhi

The Essential Gandhi: An Anthology of His Writings on His Life, Work, and Ideas at Amazon

Gandhi: An Autobiography – The Story of My Experiments With Truth at Amazon

Related pages

Indian men and women involved in the Independence Movement.

- Nehru Biography

He stood out in his time in history. Non violence as he practised it was part of his spiritual learning usedvas a political tool. How can one say he wasn’t a good lawyer or he wasn’t a good leader when he had such a following and he was part of the negotiations thar brought about Indian Independance? I just dipped into this ti find out about the salt march.:)

- February 09, 2019 9:31 AM

- By Lakmali Gunawardena

mahatma gandhi was a good person but he wasn’t all good because when he freed the indian empire the partition grew between the muslims and they fought .this didn’t happen much when the british empire was in control because muslims and hindus had a common enemy to unite against.

I am not saying the british empire was a good thing.

- January 01, 2019 3:24 PM

- By marcus carpenter

Dear very nice information Gandhi ji always inspired us thanks a lot.

- October 01, 2018 1:40 PM

FATHER OF NATION

- June 03, 2018 8:34 AM

Gandhi was a lawyer who did not make a good impression as a lawyer. His success and influence was mediocre in law religion and politics. He rose to prominence by chance. He was neither a good lawyer or a leader circumstances conspired at a time in history for him to stand out as an astute leader both in South Africa and in India. The British were unable to control the tidal wave of independence in all the countries they ruled at that time. Gandhi was astute enough to seize the opportunity and used non violence as a tool which had no teeth but caused sufficient concern for the British to negotiate and hand over territories which they had milked dry.

- February 09, 2018 2:30 PM

- By A S Cassim

By being “astute enough to seize the opportunity” and not being pushed down/ defeated by an Empire, would you agree this is actually the reason why Gandhi made a good impression as a leader? Also, despite his mediocre success and influence as you mentioned, would you agree the outcome of his accomplishments are clearly a demonstration he actually was relevant to law, religion and politics?

- November 23, 2018 12:45 AM

Culture History

Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948) was a key leader in India’s struggle for independence against British rule. He is renowned for his philosophy of nonviolent resistance, advocating civil disobedience as a powerful force for social and political change. Gandhi’s efforts played a pivotal role in India gaining independence in 1947. He is often referred to as the “Father of the Nation” in India.

Early Life and Education

Mahatma Gandhi’s early life and education laid the foundation for his transformative journey as a leader of India’s struggle for independence. Born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, a coastal town in the state of Gujarat, India, Gandhi was named Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. His birth into a modest family of the Vaishya, or business caste, was characterized by a strong influence of religious and moral values.

Gandhi’s father, Karamchand Gandhi, served as the diwan, or chief minister, of Porbandar. Despite his official position, Karamchand was known for his simplicity and integrity. These traits left a lasting impression on the young Gandhi, instilling in him a sense of duty and a commitment to truthfulness from an early age. Gandhi’s mother, Putlibai, was deeply religious and played a significant role in shaping his spiritual development.

Growing up in a devout Hindu household, Gandhi was exposed to the teachings of the Bhagavad Gita, the Ramayana, and other religious texts. The concept of ahimsa, or nonviolence, was ingrained in his upbringing, setting the stage for the principles that would later define his philosophy of resistance. His early exposure to the Jain principle of ‘live and let live’ also contributed to the formation of his nonviolent worldview.

In 1876, at the age of six, Gandhi entered primary school. A reserved and somewhat timid child, he struggled with the early years of formal education. His difficulties in expressing himself verbally and his fear of public speaking marked the beginning of a personal journey to overcome these challenges, ultimately leading him to become one of the most influential communicators in history.

At the age of thirteen, Gandhi was married to Kasturba Makhanji, also known as Ba. This early marriage was a common practice in his community, and Gandhi and Kasturba would go on to have four children together. This aspect of Gandhi’s life reflected the traditions and societal norms prevalent in 19th-century India.

In 1888, at the age of 18, Gandhi left India to pursue legal studies in London. This marked a significant departure from his cultural and familial environment, exposing him to Western thought and lifestyle. Studying law was not merely a career choice for Gandhi; it was a means to gain a deeper understanding of justice and to empower himself to address the injustices he would later encounter.

His time in London was transformative, not only academically but also culturally and spiritually. Gandhi embraced vegetarianism and delved into various religious and philosophical texts, including the Bible and works by Tolstoy and Thoreau. It was during this period that he developed a keen interest in social and political issues, setting the stage for his future activism.

After completing his legal studies, Gandhi faced a dilemma. He was offered a position to practice law in London, but he chose a different path. In 1893, Gandhi accepted an offer to work in South Africa, setting the stage for a pivotal chapter in his life. Little did he know that his experiences in South Africa would shape his philosophy of resistance and pave the way for his leadership in India’s struggle for independence.

Gandhi’s experiences in South Africa were marked by the harsh realities of racial discrimination. His confrontation with the deeply entrenched prejudices against Indians, particularly in the province of Natal, became a catalyst for his activism. The incident on a train journey from Durban to Pretoria, where he was ejected from a first-class compartment due to his skin color, became a turning point. This injustice fueled Gandhi’s resolve to fight against racial discrimination through nonviolent means.

In 1894, Gandhi founded the Natal Indian Congress in South Africa, aimed at addressing the rights and grievances of the Indian community. Over the next two decades, he led numerous campaigns against discriminatory laws such as the Asiatic Registration Act, which required all Indians to register and carry passes. These early struggles in South Africa laid the groundwork for the development of his philosophy of Satyagraha, or truth-force.

The concept of Satyagraha emphasized the power of truth and nonviolence in confronting injustice. It was not merely a political strategy but a way of life for Gandhi. This philosophy, influenced by his deep spiritual convictions, formed the core of his approach to social and political change.

Gandhi’s early activism in South Africa brought him into contact with a diverse array of people, both Indian and non-Indian, who would become instrumental in shaping his understanding of humanity and justice. The struggles in South Africa also honed his skills as a leader and strategist, setting the stage for his return to India in 1915 as a seasoned activist and leader.

South Africa Years

Mahatma Gandhi’s years in South Africa were transformative, laying the groundwork for his philosophy of nonviolent resistance and shaping his identity as a leader. Arriving in South Africa in 1893 to work as a lawyer, Gandhi’s initial experiences were marked by the harsh realities of racial discrimination, sparking a personal and political awakening.

Gandhi’s first significant confrontation with discrimination occurred during a train journey from Durban to Pretoria in 1893. Despite holding a first-class ticket, he was ejected from the compartment due to his Indian heritage. This incident became a catalyst for his activism, prompting him to challenge the unjust treatment of Indians in South Africa.

In response to the discriminatory laws targeting the Indian community, Gandhi founded the Natal Indian Congress in 1894. This organization became a platform for advocating the rights of Indians and opposing oppressive legislation. One of the early campaigns led by Gandhi was against the Asiatic Registration Act of 1906, which required all Indians, including women and children, to register and carry passes at all times. This marked the beginning of Gandhi’s engagement in civil disobedience and nonviolent resistance.

Gandhi’s approach to activism in South Africa was rooted in his evolving philosophy of Satyagraha. The term, meaning “truth-force” or “soul-force,” encapsulated his belief in the transformative power of nonviolence and the pursuit of truth. Satyagraha became more than a political tool; it was a way of life for Gandhi, emphasizing moral courage, self-discipline, and a commitment to justice.

The year 1906 proved to be a pivotal moment in Gandhi’s South African journey. In protest against the oppressive Asiatic Registration Act, he organized a gathering of Indians in Johannesburg. During this meeting, he introduced the practice of taking a collective vow to resist unjust laws through nonviolent means. This marked the formal inception of Satyagraha as a method of protest.

Gandhi’s commitment to nonviolence was further tested during the Bambatha Rebellion in 1906. The British colonial authorities called on Indians to assist in suppressing the Zulu uprising, a request that Gandhi initially supported. However, as the violence escalated, he realized the contradiction between advocating nonviolence and participating in armed conflict. This realization deepened his commitment to the principles of Satyagraha.

The years in South Africa also saw Gandhi’s emergence as a leader who transcended narrow communal boundaries. He recognized the need for unity among different racial and religious groups facing oppression. Gandhi’s efforts extended beyond the Indian community, as he sought alliances with other marginalized groups, including black South Africans. His engagement with various communities laid the foundation for his later endeavors to bridge religious and ethnic divides in India.

Gandhi’s philosophy of Satyagraha gained international attention during the Indian community’s struggle against the repressive Transvaal Asiatic Ordinance in 1908. Through nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience, Gandhi and his followers protested the imposition of fingerprinting and registration. The campaign garnered support not only within South Africa but also from sympathizers worldwide, marking Gandhi’s emergence as a global figure.

As Gandhi’s influence grew, he faced challenges and opposition from both the British authorities and some members of the Indian community. His commitment to nonviolence and truth often clashed with the prevailing attitudes and expectations. However, Gandhi’s unwavering conviction and personal sacrifices, including imprisonment, solidified his position as a symbol of resistance.

The culmination of Gandhi’s efforts in South Africa was the conclusion of negotiations with the British government in 1914. The agreement, known as the Gandhi–Smuts Agreement, marked a significant victory for the Indian community, securing certain rights and recognition. Having achieved his objectives, Gandhi decided to return to India in 1915, bringing with him the lessons and principles forged during his years in South Africa.

Philosophy of Nonviolence (Ahimsa)

Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence, or Ahimsa, stands as one of the most influential and enduring contributions to the principles of social and political change. Rooted in ancient Indian philosophies, particularly Jainism and Hinduism, Gandhi elevated Ahimsa to a guiding force in his life and activism. This philosophy went beyond mere abstention from physical violence; it encompassed a profound commitment to truth, love, and the pursuit of justice.

Ahimsa, in its broadest sense, is the principle of avoiding harm or violence to any living being, both in thought and action. For Gandhi, it was not just a moral principle but a dynamic force capable of transforming individuals and societies. His interpretation of Ahimsa went beyond the passive avoidance of violence; it involved active engagement in the pursuit of justice through nonviolent means.

The roots of Gandhi’s commitment to nonviolence can be traced back to his childhood and upbringing. Growing up in a devout Hindu household, he was exposed to the teachings of the Bhagavad Gita, which extolled the virtues of selfless action and the renunciation of the fruits of one’s actions. The Gita also emphasized the concept of Dharma, or righteous duty, which played a pivotal role in shaping Gandhi’s understanding of ethical behavior.

Gandhi’s engagement with Jainism, particularly its emphasis on nonviolence and the interconnectedness of all life, further deepened his commitment to Ahimsa. The Jain principle of ‘live and let live’ resonated with him, laying the groundwork for the expansive scope of his philosophy. Gandhi’s interpretation of Ahimsa was not limited to personal conduct; it extended to social, economic, and political realms.

The practical application of Gandhi’s philosophy began during his years in South Africa, where he confronted racial discrimination and injustice. The incident on a train in 1893, when he was forcibly removed from a first-class compartment due to his Indian heritage, marked a turning point. Instead of responding with violence or hatred, Gandhi chose to resist the injustice through nonviolent means. This event planted the seed of his philosophy of Satyagraha, which became synonymous with his broader commitment to Ahimsa.

Satyagraha, meaning “truth-force” or “soul-force,” was Gandhi’s method of nonviolent resistance. It involved the pursuit of truth through nonviolence, emphasizing the transformative power of love and compassion. Central to Satyagraha was the idea that the opponent is not an enemy to be defeated but a person with whom one seeks understanding and reconciliation.

Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence manifested in various campaigns and movements, each designed to challenge oppressive systems and bring about positive change. The Champaran and Kheda movements in India, where he championed the cause of indigo farmers and peasants affected by crop failure, respectively, showcased his commitment to social justice through nonviolent action. In both cases, he urged the people to resist injustice peacefully, promoting the idea that the power of truth and nonviolence could overcome the might of oppressive regimes.

The Salt March of 1930 became an iconic demonstration of Gandhi’s philosophy in action. In protest against the British monopoly on salt, Gandhi led a 240-mile march to the Arabian Sea, symbolically producing salt from seawater. The act, while seemingly minor, highlighted the broader issues of colonial exploitation and economic injustice. The Salt March exemplified the power of nonviolent resistance to mobilize people, capture global attention, and inspire similar movements worldwide.

Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence extended beyond the political sphere to encompass personal and interpersonal relationships. His commitment to Ahimsa influenced his lifestyle choices, including vegetarianism, and his advocacy for simplicity and self-sufficiency. Gandhi believed that individuals should strive to align their lives with the principles of nonviolence, fostering harmony with both humanity and the natural world.

The concept of “Sarvodaya,” meaning the welfare of all, was another expression of Gandhi’s commitment to nonviolence. He envisioned a society where the well-being of every individual was considered, emphasizing social and economic equality. The pursuit of Sarvodaya required a rejection of violence and exploitation in all its forms, urging people to live in harmony and mutual respect.

Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence faced challenges and criticisms, both from within and outside the independence movement. Some questioned the efficacy of nonviolence in the face of brutal repression, while others argued that it was an impractical ideal. Gandhi acknowledged the difficulties but remained steadfast in his belief that nonviolence was not a sign of weakness but a potent force capable of transforming societies.

The Quit India movement of 1942 marked another crucial moment for Gandhi’s philosophy. As the call for immediate independence echoed, he emphasized nonviolent non-cooperation as the means to achieve it. The movement faced severe repression from the British authorities, leading to the arrest of Gandhi and many other Congress leaders. The sacrifices made during this period underscored the resilience and enduring power of nonviolence as a force for change.

Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence was not limited to political activism; it sought to address the root causes of conflict and injustice. His efforts to unite Hindus and Muslims, as well as his advocacy for the rights of the untouchables (Dalits), demonstrated a commitment to social harmony and inclusivity. Gandhi believed that true nonviolence required addressing the underlying prejudices and inequalities within society.

In the aftermath of India’s independence in 1947, Gandhi continued to advocate for communal harmony and worked towards preventing the violence that accompanied the partition. His commitment to nonviolence was tested in the face of deep-rooted religious animosities, and he resorted to fasting as a means of urging people to embrace peace and unity.

On January 30, 1948, Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated by Nathuram Godse, a Hindu nationalist who opposed Gandhi’s conciliatory stance towards Muslims. Gandhi’s death was a tragic irony, as the apostle of nonviolence fell victim to violence. However, his legacy endured, inspiring subsequent generations of leaders and movements committed to nonviolent resistance.

Return to India and Nationalist Movement

Mahatma Gandhi’s return to India in 1915 marked a pivotal moment in the country’s struggle for independence and set the stage for his leadership in the nationalist movement. Having honed his skills and philosophy of nonviolence in South Africa, Gandhi brought a unique perspective and a steadfast commitment to Satyagraha, or truth-force, to the Indian political landscape. His return coincided with a time of heightened nationalist fervor, and Gandhi quickly emerged as a central figure in shaping the course of India’s fight against British colonial rule.

Upon his return, Gandhi was greeted by a country grappling with socio-economic challenges and aspirations for self-governance. The First World War had created economic hardships, and the demands for greater Indian participation in governance were growing louder. Gandhi’s initial foray into Indian politics involved addressing the issues of indigo farmers in Champaran and peasants in Kheda, where he applied his philosophy of nonviolent resistance to champion the causes of the oppressed.

The Champaran Satyagraha of 1917 saw Gandhi leading a campaign against the exploitative practices of British indigo planters. Through nonviolent protests and civil disobedience, he sought justice for the indigo farmers who were burdened with unfair taxation. The success of this movement not only improved the conditions of the farmers but also showcased the potential of nonviolent resistance in achieving social and economic justice.

Gandhi’s involvement in the Kheda Satyagraha later in 1918 further solidified his position as a leader committed to the welfare of the common people. In Kheda, he supported the peasants who were facing crop failures due to floods. Advocating for the waiver of land revenue, he used nonviolent means to draw attention to the plight of the farmers. The British administration, under the influence of his principled resistance, eventually relented, granting relief to the affected peasants.

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919 became a turning point that galvanized the Indian populace against British rule. The brutal killing of hundreds of unarmed civilians by British troops in Amritsar on April 13, 1919, shocked the nation and intensified the demand for self-rule. Gandhi, deeply disturbed by the massacre, called for a nationwide protest and non-cooperation with the British government.

The Non-Cooperation Movement launched by Gandhi in 1920 aimed at boycotting British institutions, courts, schools, and products. It represented a significant departure from conventional forms of political agitation, emphasizing nonviolence and non-cooperation as the means to achieve political objectives. Millions of Indians participated in the movement, making it a powerful expression of the collective will for independence.

However, in 1922, the Non-Cooperation Movement faced an abrupt end when a violent incident occurred in the town of Chauri Chaura. A group of protestors turned violent, resulting in the death of police officers. In response to the escalation of violence, Gandhi, true to his commitment to nonviolence, decided to call off the movement, acknowledging that the people were not yet fully prepared for the path of nonviolent resistance.

The suspension of the Non-Cooperation Movement led to a period of reflection and strategic reevaluation for Gandhi. During this time, he delved into constructive programs aimed at socio-economic upliftment. He advocated for self-reliance, Khadi (hand-spun cloth), and the removal of untouchability. The emphasis on constructive work was not only a response to the setbacks in political agitation but also a reflection of Gandhi’s belief that true independence required the transformation of individuals and society.

In 1930, Gandhi launched one of the most iconic episodes of the nationalist movement—the Salt March. In protest against the British monopoly on salt, he embarked on a 240-mile march from Sabarmati Ashram to the Arabian Sea, symbolically producing salt from seawater. The Salt March captured the imagination of the nation and the world, becoming a symbol of nonviolent resistance against unjust colonial laws.

The civil disobedience that accompanied the Salt March marked the beginning of the broader Civil Disobedience Movement. Indians across the country defied the salt laws, boycotted British goods, and refused to pay taxes. The movement, characterized by its nonviolent nature, aimed to exert economic and political pressure on the British government. Although it led to mass arrests, including that of Gandhi, and widespread repression, it significantly intensified the demand for independence.

The Round Table Conferences in London, held in 1930-1932, provided a platform for negotiations between Indian leaders and the British government. Gandhi, representing the Indian National Congress, attended the conferences with the hope of finding a constitutional solution for India’s future. However, the discussions failed to produce a consensus, and the gap between the Indian National Congress and the British government widened.

The Quit India movement of 1942 marked another crucial chapter in the nationalist movement. Frustrated by the failure of negotiations and inspired by the global context of World War II, Gandhi called for the immediate withdrawal of British colonial rule. The movement received widespread support, with millions participating in strikes, protests, and acts of civil disobedience. The British response was harsh, leading to the arrest of Gandhi and other Congress leaders.

The Quit India movement, while facing severe repression, demonstrated the resilience of the Indian people’s desire for freedom. It also highlighted the changing dynamics of global politics, with the British government recognizing the need for post-war reforms. The post-war period witnessed a weakened British Empire and a recognition that continued colonial rule was unsustainable.

India’s independence in 1947 was a culmination of decades of struggle, sacrifice, and determination. The partition of India into two independent nations, India and Pakistan, brought about communal tensions and mass migrations. Gandhi, deeply distressed by the communal violence, undertook fasts and walked through riot-torn areas, urging people to embrace peace and unity. His efforts were a testament to his commitment to inter-religious harmony and his belief in nonviolence as a means of resolving conflicts.

On January 30, 1948, Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated by Nathuram Godse, a Hindu nationalist who opposed Gandhi’s conciliatory stance towards Muslims. His death was a tragic end to a life dedicated to nonviolence and the pursuit of truth. However, Gandhi’s legacy endured, influencing global movements for civil rights and inspiring leaders committed to justice through peaceful means.

Champaran and Kheda Satyagraha

Mahatma Gandhi’s involvement in the Champaran and Kheda Satyagrahas during the early years of his return to India marked the beginning of his leadership in the country’s struggle for independence. These two movements were pivotal in shaping Gandhi’s approach to nonviolent resistance and establishing the foundations of Satyagraha as a potent force for social and economic justice.

The Champaran Satyagraha of 1917 was Gandhi’s first major campaign in India. It unfolded in the Champaran district of Bihar, where indigo farmers faced oppressive conditions imposed by British indigo planters. The farmers were compelled to cultivate indigo on a portion of their land, a crop that yielded significant profits for the planters but left the farmers in abject poverty.

Gandhi’s involvement in Champaran was a response to the plight of these farmers, who were burdened with exorbitant taxes and forced labor. The British authorities had imposed the ‘Tinkathia’ system, requiring a certain portion of land to be dedicated to indigo cultivation. This system left the farmers with minimal land for their own sustenance, and they were often forced to grow indigo against their will.

Upon arriving in Champaran, Gandhi immersed himself in understanding the grievances of the indigo farmers. His approach was not confrontational but investigative, seeking to comprehend the issues at the grassroots level. He held meetings with the farmers, heard their stories, and documented the injustices they faced.

The Champaran Satyagraha, unlike conventional agitations, was characterized by its nonviolent and cooperative nature. Gandhi emphasized the importance of truth and nonviolence in confronting oppression. He urged the farmers to withhold payment of taxes and to resist the unjust demands peacefully. This approach was a precursor to Gandhi’s philosophy of Satyagraha, where the pursuit of truth through nonviolent means became a powerful tool for social and political change.

Gandhi’s call for nonviolent resistance in Champaran resonated with the masses. The farmers, inspired by his leadership and philosophy, began to withhold payments to the planters. The British authorities responded with arrests and legal action against Gandhi, but he remained steadfast in his commitment to nonviolence and the pursuit of justice.

The success of the Champaran Satyagraha was multi-faceted. Through negotiations and legal battles, Gandhi was able to secure concessions for the indigo farmers. The ‘Tinkathia’ system was abolished, and the farmers gained more control over their land. The Champaran movement showcased the effectiveness of nonviolent resistance in challenging oppressive policies and was a harbinger of Gandhi’s future campaigns.

Following the triumph in Champaran, Gandhi turned his attention to the Kheda district in Gujarat. The Kheda Satyagraha of 1918 was prompted by the economic distress faced by peasants due to crop failures and a devastating famine. The British administration, insensitive to the plight of the farmers, insisted on the collection of land revenue, exacerbating the suffering of the already distressed population.

In Kheda, Gandhi applied the lessons learned from Champaran, emphasizing nonviolent resistance and the power of collective action. He called for a boycott of the payment of land revenue as a form of protest against the unjust policies of the British government. The movement gained momentum as peasants, both Hindu and Muslim, united under the banner of nonviolent resistance.

Gandhi’s approach in Kheda was characterized by constructive work alongside the Satyagraha. He encouraged villagers to focus on self-reliance, urging them to cultivate their own food and adopt measures to withstand the economic hardships imposed by the British policies. This emphasis on constructive work became a recurring theme in Gandhi’s philosophy, reflecting his belief that true independence required socio-economic transformation at the grassroots level.

The British administration, faced with the resilience of the Kheda Satyagrahis, entered into negotiations with Gandhi. Despite the severe economic conditions, the peasants stood firm in their commitment to nonviolence. Eventually, a settlement known as the ‘Kheda Pact’ was reached. The British agreed to suspend the collection of land revenue in Kheda for a year, providing much-needed relief to the distressed farmers.

The Champaran and Kheda Satyagrahas were instrumental in shaping Gandhi’s evolving philosophy of nonviolent resistance. These movements were not merely protests against specific grievances; they were experiments in the application of Satyagraha as a method of social and economic change. Gandhi’s emphasis on nonviolence, truth, and the empowerment of the oppressed became defining features of his leadership style.

The success of Champaran and Kheda also demonstrated the potential of nonviolent resistance in awakening the collective conscience of the masses. The movements were not driven by a desire for revenge or retaliation; rather, they sought to transform the oppressor by appealing to a shared sense of humanity and justice. This approach marked a departure from conventional forms of political agitation, setting Gandhi apart as a leader committed to principles that transcended mere political objectives.

The Champaran and Kheda Satyagrahas laid the groundwork for Gandhi’s subsequent involvement in larger national movements. The lessons learned from these early campaigns informed his strategies during the Non-Cooperation Movement, the Civil Disobedience Movement, and the Quit India movement. The emphasis on nonviolence, constructive work, and the pursuit of truth became integral components of the broader struggle for India’s independence.

Non-Cooperation Movement

The Non-Cooperation Movement, launched by Mahatma Gandhi in 1920, was a watershed moment in India’s struggle for independence. This movement marked a departure from conventional forms of political agitation, as it advocated nonviolent non-cooperation with British authorities as a means to achieve political objectives. The Non-Cooperation Movement, with its emphasis on nonviolence, mass participation, and constructive work, reshaped the dynamics of India’s fight against colonial rule.

The backdrop of the Non-Cooperation Movement was a nation disillusioned by the aftermath of World War I and seeking avenues for greater participation in governance. The Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919, where British troops killed hundreds of unarmed civilians in Amritsar, had intensified the demand for self-rule. The oppressive Rowlatt Act, enacted by the British government, further fueled resentment and discontent among Indians.

Mahatma Gandhi, who had already established himself as a leader during the Champaran and Kheda Satyagrahas, recognized the need for a more expansive and inclusive movement. The Non-Cooperation Movement was conceived as a response to the growing discontent and the desire for Indians to assert their rights. Gandhi believed that nonviolent non-cooperation would be a potent weapon to express popular discontent and compel the British government to address Indian demands for self-governance.

Launched on August 1, 1920, the Non-Cooperation Movement had a broad agenda. It called for the non-cooperation with British institutions, including educational, legislative, and administrative bodies. Indians were urged to boycott government schools, colleges, and offices. The movement also advocated the surrender of titles and honors bestowed by the British government, encouraging Indians to resign from government jobs and the army.

One of the central elements of the Non-Cooperation Movement was the boycott of foreign goods. Indians were asked to discard foreign-made clothes, especially British textiles, and embrace Khadi—the hand-spun, handwoven fabric symbolizing self-reliance and resistance to economic exploitation. The spinning wheel, or charkha, became an iconic symbol of the movement, representing the economic independence and self-sufficiency that Gandhi envisioned.

The call for nonviolent non-cooperation resonated across the length and breadth of the country. The movement garnered widespread support from various sections of society, cutting across religious, caste, and economic lines. The participation of women in large numbers also added a new dimension to the struggle for independence. The involvement of all segments of society reflected the inclusive nature of the Non-Cooperation Movement.