The trends shaping UK higher education in 2023 and beyond

- Education Focused

6 minute read

Forces shaping the UK’s higher education sector and where we’re headed next

Universities are struggling to find growth due to reduced interest in post-graduate degrees, says Kim McLellan, Managing Director at Hunterlodge, who oversees a range of higher education clients.

Universities are struggling to find growth in the UK due to reduced interest in post-graduate (PG) degrees from the home market, says Kim McLellan, Managing Director at Hunterlodge, who oversees a range of higher education clients.

“These challenges go back to 2014-18 when the higher education sector essentially ‘ate its lunch for breakfast,’” says Kim. What I mean by that is, at that time, the undergraduate market was struggling due to population deficits of 18-year-olds, so Higher Education Institutes (HEI’s) began mopping up more and more potential PG students into their Undergraduate (UG) study places.”

“Another big factor impacting PG numbers is that PG study normally tracks the job market. In a buoyant job market, PG goes down. When the job market is tough, PG goes up. Right now, the job market is booming, so universities are facing a hard PG home market. Many businesses are starting to feel the pinch and are sensing that change in the air.”

Kim says he believes this will prove a “short-term blip” and the upward trajectory will return in short order. “For now, HEI’s will need to be more strategic in their approach, work more collaboratively and be more agile in order to pivot and make up revenue losses,” Kim says. “In recent memory, marketing has always been about the 4 Ps – Product, Price, Place, Promotion – and for some reason senior management only listens to marketing about promotion. This is no longer the case.”

“Place has become vital, and many universities have been attempting to fill their PG gap by attracting international students, to middling success, as they experience how volatile international markets can be and the need for international diversification.”

Kim says there are several other higher education trends shaping the UG market too, from the cost-of-living crisis to the rise in online learning. Read on for more.

It’s the Big 4 for a reason

First is the resurgence of the ‘Big 4’ degree subjects – business, psychology, computer science and law – which are seeing disproportionate growth both nationally and internationally, according to Kim. To grow as a university, he says it’s imperative to have a strong provision in at least three of these subjects.

“The smart ones are investing heavily in their product portfolio, but the big problem is that you need to have an equal share of voice between subjects,” Kim says. “You have course leaders saying, what about us? It’s very political. A university can’t act like a business and back the winning horse or horses. Plus, for the sake of their academic and research capabilities, you do need a broad range of subjects. The war is raging between academic prowess and commercial sanity. The point is that those who can manage these forces effectively will come out on top.”

Statistics business Statista found that in the 2020/21 academic year, there were 474,970 enrolments for courses involving business and management studies, making it the most popular subject group in that year, followed by medicine with 339,150 enrolments.

Cost-of-living isn’t going anywhere

Many universities are overlooking the cost-of-living crisis, says Kim, but it’s important that they don’t let the issue slip into the background. A survey by Save the Student, a website that investigates student issues, shows the average student’s maintenance loan falls short of covering their living costs by £439 every month in 2022. He says this is set to get worse.

“My advice to universities would be to discover, what’s their spin?” Kim says. “How does cost-of-living fit with their brand? What are they doing about it for their students? Some universities are smashing it. For example, the University of Northampton is giving free laptops to every student that starts. When students join, they can say, here’s the Wi-Fi, now get on with your studies. It’s simple, smart thinking. In addition, they are dropping accommodation deposits to show their continued support to their students. Others are tapping into their data to better understand whether their students are living at home or looking for private accommodation then altering their advertising.”

Kim wants to see a London university come out as the first to offer free travel cards throughout a student’s study or provide food, heating, accommodation grants – appreciating that it is the most expensive place in the UK to live.

A resurgence of MOOCs

MOOCs (massive open online courses) have been around for a while and are seeing a significant resurgence, says Kim. To entice prospective students to the top of the funnel, universities are now offering MOOCs for free, with many courses are also being modularized to facilitate the “own place, own pace” trend to huge commercial return. According to Statistics Business Research and Markets, the EdTech market could reach $605 billion in value by 2027, up from $254 billion today.

“MOOCs have been around for years in places such as the Open University, but only a few universities have been smart enough to digitize products, especially when it comes to modular delivery,” Kim says. “You could break down a typical MBA, split it into four components—things like leadership, for example—and charge a premium on that six-to-eight-week course.”

The London School of Economics is one institution that Kim thinks has done this effectively.

The road ahead

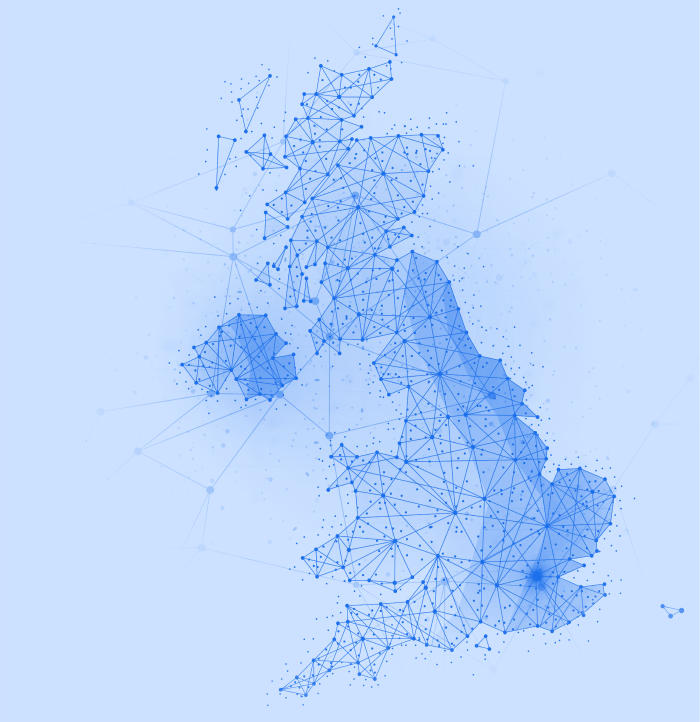

According to Kim, many of these issues will remain for years to come. However, there is good news. Population growth means that the undergraduate market will remain buoyant in the coming years – very shortly becoming tomorrow’s PG market (as soon as 2024). Indeed, the Office for National Statists predicts that the population of the UK will increase from an estimated 67.1 million in mid-2020 to 69.2 million in mid-2030, with England’s population is projected to grow more quickly than the other UK nations.

“Population growth in the home market will continue to be buoyant for the next 10-15 years,” says Kim. “Between 2016 and 2021, the population had a dip, but today the 18-21 market is bouncing back at a huge rate. What you do have is disproportionate growth across the country. And what that means is that London is going to be the hunting ground for students.

“The message for universities is that the population is there, and the market is there, the challenge is working out what part of the market you want to capture,” says Kim. “The UK is also fast becoming the number one destination for international students. While some issues will remain, between the growth in the two markets, the future is looking very, very rosy for any higher education institutions.”

We’ve got our fingers on the pulse, so drop us a line at [email protected] and let’s chat.

Want to see what we can do for you?

Is online learning just another HE 'trend'?

5 youth marketing trends for 2023

- Meet the Team

- Education Focussed

- CRM and Automation

Quick Links

- Our Services

- Privacy Overview

- 3rd Party Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

This website uses Google Analytics to collect anonymous information such as the number of visitors to the site, and the most popular pages.

Keeping this cookie enabled helps us to improve our website.

Please enable Strictly Necessary Cookies first so that we can save your preferences!

- Teaching, learning and quality

Higher education in facts and figures: 2021

Last updated on Wednesday 14 Jun 2023 at 2:52pm

On this page

About this data.

- Back to top

An overview of the data on students, staff and university finances from our member institutions.

Highlights

Record proportions of the most disadvantaged students began a full-time undergraduate course in the UK in 2020, across all four nations of the UK.

In 2020, median graduate salaries were £10,000 higher in England than non-graduate salaries.

In 2019−20, 15.8% of undergraduate students and 40.5% of postgraduate students at UUK member institutions were from outside the UK.

In 2019−20, nearly half of total expenditure was spent directly on teaching and research activities.

What data have we used?

Most data we’ve used refers to just our member institutions. This covers 140 universities and higher education providers in the UK.

The data we have used for each chart is clearly labelled and mostly comes from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) records, which covers a wider set of providers. The below charts show the proportion of student, staff and finance data within each of the public HESA records that is represented by Universities UK members.

Promoted content

Stay up to date with our work.

Our monthly updates are a great way for you to stay up to date with our work, events, and higher education news.

In 2019−20, there were 2,413,155 students at UUK member institutions; an increase of 3.1% compared to 2018−19. Of these students:

- 79.6% studied full time

- 74.5% were undergraduates

- 5.8% were from EU countries

- 16.3% were from other non-EU countries

- 56.9% were females

- 59.9% were mature students (aged 21 and over)

Students by mode of study and country of institution, 2019–20

The number of students studying full time has increased by 3.1% since 2018–19. Part-time numbers have decreased slightly (down 0.2% on 2018–19). In 2019−20, part-time students accounted for 36.9% of postgraduate students and 14.7% of undergraduate students.

Students by level and mode of study, 2019–20

In 2019–20, four fifths of students were studying full-time. 69.2% of students were studying for a first degree either full or part time, and a quarter (25.5%) were postgraduates. 'Other undergraduates' (which includes those studying for foundation degrees, diplomas in higher education, or Higher National Diplomas among others) were the most likely to be studying part time, followed by postgraduate taught students.

Applicants, acceptances and UK 18-year-old entry rates, 2011 to 2020

For the 2020 cycle, the total number of people applying for UK full-time undergraduate higher education courses increased by 3.2% on 2019, while total acceptances increased by 5.4%. The UK 18-year-old entry rate was also at record levels, with 37.0% of this group starting a full-time undergraduate course.

Entry rates of the most disadvantaged 18-year-olds by domicile, 2011 to 2021

Record proportions of the most disadvantaged students began a full-time undergraduate course in the UK in 2020 across all four nations of the UK. The charts below show the proportion of 18-year-olds from the areas considered to be in the top fifth most disadvantaged areas who began a course.

Students by age and ethnicity, 2019–20

In 2019−20, mature students (aged 21 and over) accounted for 57.5% of the student population at UUK member institutions. This includes 44.3% of students studying for their first undergraduate degree. Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) students accounted for 25.1% of students living permanently in the UK.

Students by sex, subject area and level of study, 2019–20

In 2019−20, undergraduate student numbers were highest in the subjects of business, subjects allied to medicine and social sciences. Postgraduate numbers were highest for business, subjects allied to medicine and education. Psychology had the highest proportion of female students at 81.1% with the lowest found in computing, and engineering and technology at 19.8% each.

Students by domicile and level of study, 2019–20

In 2019−20, 5.5% of undergraduates were from EU countries, while 10.3% were from outside the EU. Percentages for postgraduates were 6.8% and 33.7% respectively.

In 2019-20, UUK members awarded 761,215 qualifications.

- 61% were undergraduate qualifications and 39% were postgraduate

- 80% of graduates were in employment or unpaid work 15 months after graduation

- 19% of graduates were in further study

- Median salaries for graduates were £9,500 higher than non-graduates

- 5.3% of non-graduates were unemployed compared to 3.7% of graduates

Qualifications awarded by level and mode of study, 2019–20

In 2019−20, more than half (53.6%) of qualifications awarded by UUK member institutions were first degrees. 85.8% of qualifications awarded were for full-time study.

Graduate outcomes by activity, 2018–19

In 2019−20, 80% of graduates who responded to HESA's Graduate Outcomes survey were in employment or unpaid work. 19% of survey respondents were in further study, including those who were also in employment.

Unemployment rates and median salaries in England, 2020

In 2020, median salaries for England-domiciled graduates were £9,500 higher than median non-graduate salaries. The graduate unemployment rate was 3.7%, compared to 5.3% for non-graduates, while the high-skill employment rate was 53.9 percentage points higher for postgraduates than non-graduates, and 41.5 percentage points higher for graduates than non-graduates.

In 2019−20, there were 409,055 staff at UUK member institutions, of these:

- 53.0% were academic staff

- 12.7% were from EU countries

- 9.5% were from non-EU countries

- 54.2% were female

- 30.7% were aged under 35 years old

- 14.4% were Black, Asian and minority ethnic staff.

Staff by nationality and employment function, 2019–20

In 2019−20, over a fifth (22.2%) of staff at UUK member institutions had a non-UK nationality. Half (48.9%) of academic staff with a 'research only' function had a non-UK nationality.

Academic staff by nationality and cost centre, 2019−20

In 2019−20, non-UK staff accounted for nearly half (47.2%) of academic staff in engineering and technology compared to 13.3% in education.

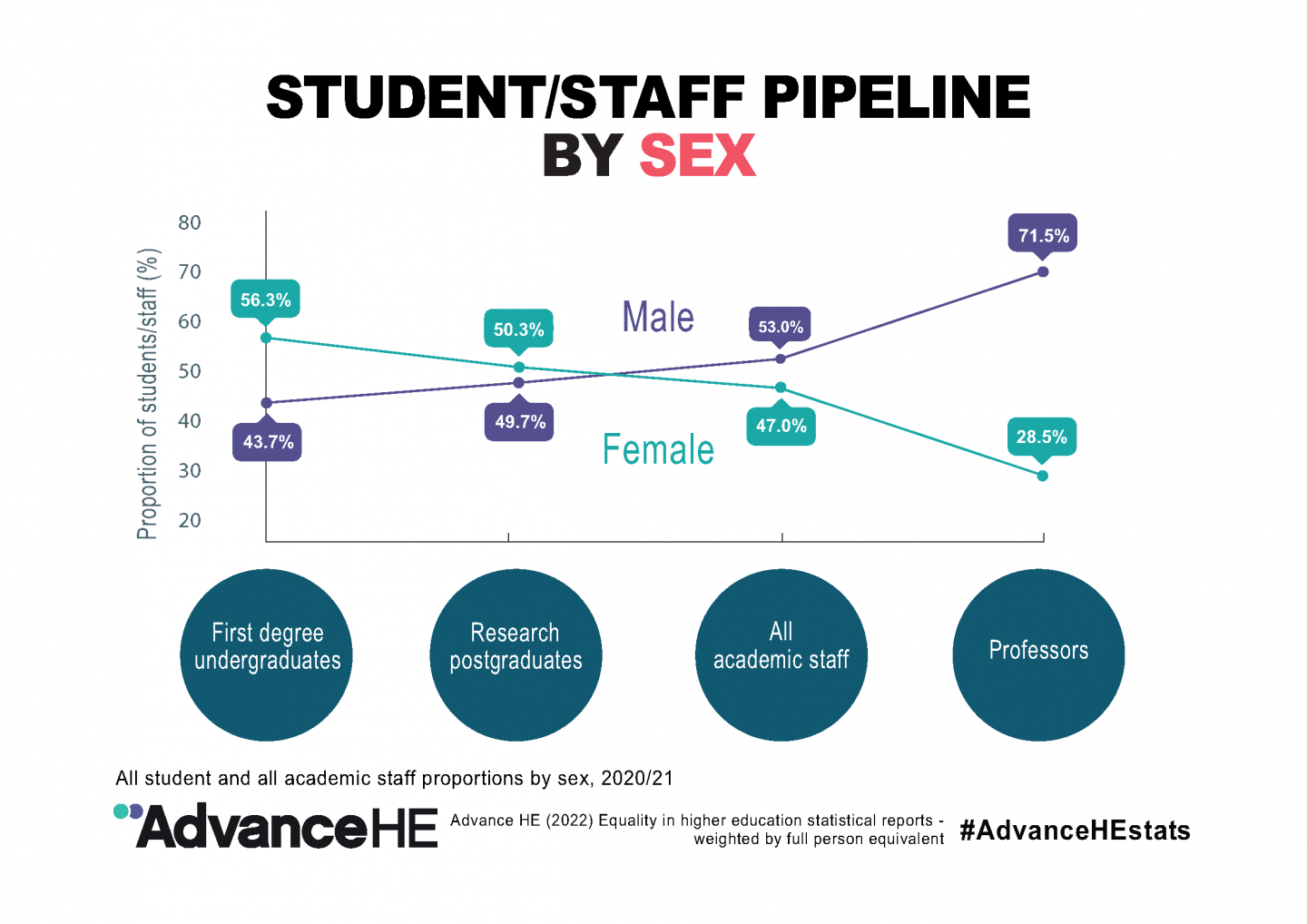

Academic staff by sex, mode of employment and age, 2019–20

In 2019−20, 46.6% of academic staff at UUK member institutions were female, while 34.0% of staff were working part-time. 29.0% were 35 or under.

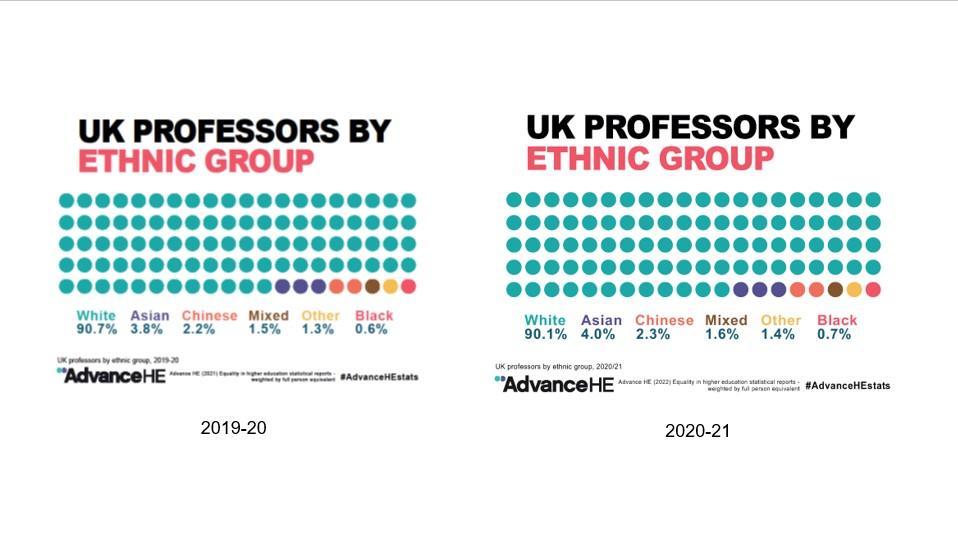

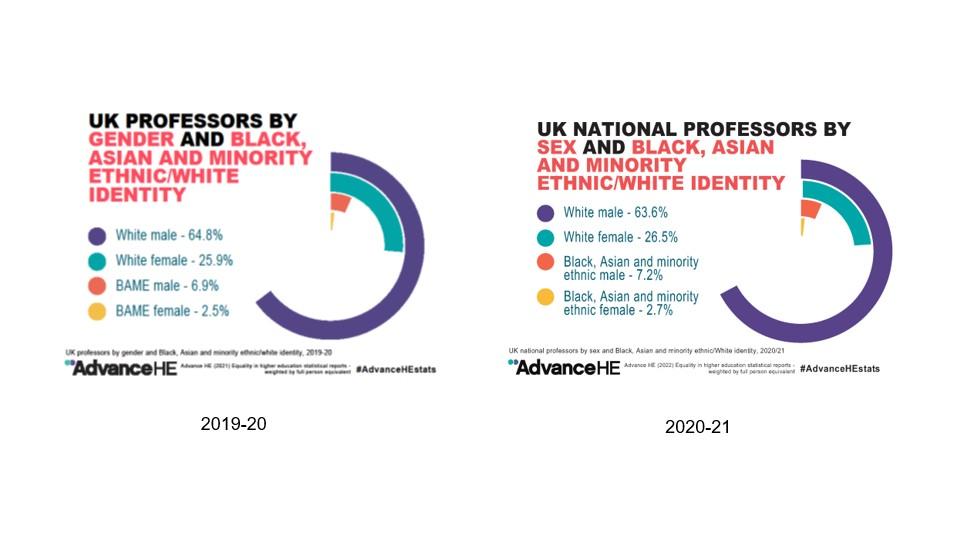

Professors by sex and ethnicity, 2015–16 to 2019–20

Although the number of Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME), professors has increased by nearly a third (32.2%) since 2015−16, they only accounted for 10.0% of professors in 2019−20. Over half (58.6%) were white males.

In 2019–20, the total reported income of UUK member institutions was £39.8 billion. Just over half of this income (£20.7 billion) was related to teaching, 15% was related to research (£6.1 billion), and 11% was related to knowledge exchange activity (£4.5 billion).

In 2019–20, our members' total expenditure was £36.4 billion. Nearly half (£17.5 billion) was spent on direct teaching and research activity, and over a tenth (£3.8 billion) was spent on libraries, IT and museums.

Income and size of higher education institutions, 2018–19 to 2019–20

In 2019−20, three quarters of UUK members had an annual income of £100 million or more, with a similar proportion having at least 10,000 students.

Income by source, 2019–20

In 2019−20, the total reported income of UK higher education institutions was £39.8 billion. Around half (£20.7 billion) of this income was sourced through tuition fees.

Teaching, research and knowledge exchange income by source, 2019–20

In 2019−20 around a third (32.3%) of teaching income was from international students from outside the EU. A third of research income came from research councils (33.6%), and nearly a quarter (23.3%) came from outside of the UK. In 2019−20, over a third of knowledge exchange income came from collaborative research involving public funding. This includes collaboration with at least one non-academic partner, which can include businesses, the third sector, and the public. The estimated current turnover of spin-off or start-up firms based on providers' intellectual property, or started by staff, students or graduates increased significantly in 2019−20. Businesses associated with UUK members had an estimated turnover of £7.9 billion with the majority coming from staff start-ups (£2.8 billion) and student start-ups (£2.6bn).

International Facts and Figures 2021

International Facts and Figures is our annual snapshot of the international dimensions of UK higher education.

Operating expenditure of UK higher education institutions, 2019–20

In 2019–20, the total reported operating expenditure of UUK member institutions was £36 billion. Nearly half of this was spent directly on teaching and research activities. Other areas of spending include those that support teaching and learning, such as libraries and IT, maintaining campuses, providing financial support to students and student facilities.

Academic employment function

A HESA field relating to staff with academic contracts. Categories are divided according to whether the contract is ‘teaching only’, ‘research only’ (no more than six hours of teaching per week), ‘teaching and research’, and neither teaching nor research. For more information visit HESA's website .

Cost centre

Cost centre is a financial concept which groups staff members to categories of spending. They enable analysis between the student, staff and finance streams. The cost centre groups are separate to the JACS/HESA codes due to the groupings and are therefore non-comparable. The reason they can't be compared and the breadth of the elements in this field is to replicate the way in which resources (including staff) can be split over multiple courses and the differences in the way individual higher education providers allocate them. For more information visit HESA's website .

A student’s permanent country of residence. This differs from nationality (see below).

The number of university entrants divided by the estimated base population.

The Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) is the designated data body for English higher education.

High-skill employment

Occupations at this level are generally termed ‘professional’ or ‘managerial’ positions and are found in corporate enterprises or governments. Occupations include senior government officials, financial managers, scientists, engineers, medical doctors, teachers and accountants.

Knowledge exchange activities

Activities that bring together academic staff, users of research and wider groups and communities to exchange ideas, evidence and expertise. Information on knowledge exchange activities is collected by HESA through their Higher Education Business and Community Interaction (HEBCI) survey. For more information visit HESA's website .

Level of study

Whether a student studies at undergraduate or postgraduate level. With these groupings, there are other levels such as ‘first degree’, ‘other undergraduate’, ‘postgraduate (research)’ and ‘postgraduate (taught)’. For more information visit HESA's website .

Mode of study

Whether a student studies full or part time.

Nationality

A HESA field that records the legal nationality of staff. For more information visit HESA's website .

Participation of Local Areas (POLAR) is a widening participation measure which classifies local areas or ‘wards’ into five groups, based on the proportion of 18-year-olds who enter higher education aged 18 or 19 years old. These groups range from quintile 1 areas, with the lowest young participation (most disadvantaged), up to quintile 5 areas with the highest rates (most advantaged).

Professorial staff

HESA codes each staff contract. Professor level is defined as ‘senior academic appointments which may carry the title of professor, but which do not have departmental line management responsibilities’. Other senior contracts include leadership and management responsibilities. These contracts may also be held by people who hold the title of professor. It is likely that the methodology undercounts the number of professors because many will fall into more senior levels, eg heads of department.

The Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation for 2016 is a widening participation measure that identifies small areas of multiple deprivation across Scotland and classifies them into five groups. These groups range from quintile 1 – areas identified as the most disadvantaged, to quintile 5 – areas identified as the most advantaged.

HESA Standard Rounding Methodology

We have applied HESA’s Standard Rounding Methodology to all analysis of HESA data:

- Counts of people are rounded to the nearest multiple of five

- Percentages are not published if they are fractions of a small group of people (fewer than 22.5)

- We have applied the methodology after making calculations, which sometimes means numbers in tables may not sum up to indicated totals

For more information, visit HESA's website .

HESA sources in this report are copyright Higher Education Statistics Agency Limited.

Neither the Higher Education Statistics Agency Limited nor HESA Services Limited can accept responsibility for any inferences or conclusions derived by third parties from data or other information obtained from Heidi Plus.

Higher education in numbers

Key facts and figures about UK higher education.

- Challenges Facing Higher Education In The UK

Challenges Facing Higher Education in the UK

The government’s plan to introduce a cap on the number of students studying ‘low-value’ universities degrees raises wider questions about the future of Higher Education in the UK – not just value for money but also the financial state of UK universities, the return to university education and the number of viable HE institutions. Our Deputy Director Professor Adrian Pabst spoke with Professor Peter Dolton, NIESR Research Director who has worked for several decades on the economics of Higher Education in the UK.

Professor Peter Dolton

Professor Adrian Pabst

Related Themes

What is the financial state of uk universities.

Universities are trying to exert pressure on the government to allow higher fees from their £9,250 level. Their argument is that fees have not risen since 2017 and that the costs of university education have all risen approximately in line with inflation by around 26% (They were set at £9,000 in 2012.) Neither the Conservative government nor the Labour opposition seem prepared to let fees rise as they see this as being unpopular with the electorate and hence a vote loser. At the same time neither major political party is prepared to raise the level of teaching funding from central government (which would obviate the need to raise fees.) This central funding of university education has all but disappeared.

Presently, UK university fees are the highest in the world, with the lowest subsidy to potential students. But as it stands it is still the case that it is predominately the children of middle- and upper-class families who go to university. Several prominent papers in the literature have suggested that higher fees would not deter applicants from going to university. But recent work by Li Lin and myself using a more complete econometric model of post-war demand has suggested that higher fees would have small negative impact on demand.

Many years ago, my work together with colleagues suggested that fees should be allowed to vary by subject and university. There are powerful arguments to support this view, but this is unlikely to happen in the present policy vacuum on HE in the UK. The explicit cross- subsidisation of science and medicine by social science and humanities is not efficient.

Presently, most universities that are only financially viable because of their income from overseas postgraduate income. This is income derived from rich families in predominantly poor countries. This is not a morally or ethically viable way to fund UK universities.

What is the return to university education?

The idea that students should fund their own fees (and subsistence) via a loan is predicated on the theory that graduates have invested in their own human capital and that they will reap a return on this investment via higher future earnings in the labour market as highly qualified people. But what is the return to university education?

The literature on the rate of return has variously suggested that the annual rate of return to a degree is between 8-15 per cent. This figure has been estimated using a limited econometric estimation strategy. Recent work by myself and my co-authors suggests that the true figure is much lower at around 6 per cent. Moreover, this return is an estimated average return which is a lot lower for some subjects. Recent work by the IFS has shown a huge variability across subjects and institutions of graduation in how good a return there is to UK Higher Education.

How many universities do we need?

Around 30 per cent of graduates do not end up with up with a graduate job. This has been the case for around 50 years. This ‘over-education’, as I argued already in 2000 together with Anna Vignoles, is predominantly a problem for graduates in arts and humanities subjects from lesser-known universities. This raises the question of how many university places (and hence universities) we actually need? Arguably, with over 160 universities in the UK, we have far too many places at university offering courses that UK industry does not need.

Other countries educate closer to the number of graduates their industries need in far fewer universities. For example, in the Netherlands they have far fewer universities which offer much larger courses provided in a much more efficient way. It is important that we keep the question open of how many universities the country actually needs. This should be partly determined by the answers to the previous two questions – i.e. how many of our universities are financially viable and what is the rate of return to degree study for individuals?

Related Blog Posts

What Can Be Done To Better Protect Children and Young People From Serious Safeguarding Incidents?

Sophie Kitson

Ekaterina Aleynikova

19 Feb 2024

Putting Increased Pressure on a Fragile System Does Not Help

Claudine Bowyer-Crane

Cecilia Zuniga-Montanez

15 Jan 2024

Safeguarding the Safeguards – more Support Needed, But How?

Lucy Stokes

Johnny Runge

Adrian Pabst

02 May 2023

Can Texting Parents Help Improve Children’s Development?

Ceri Williams

Anneka Dawson

12 May 2022

Related Projects

Evaluation of Talking Time Efficacy Trial

Catch Up Literacy Pilot Study

Impact of Covid-19 on Children’s Language, Education and Socio-Emotional Skills (ICICLES)

Better Start Bradford

Related news.

Press Release: NIESR awarded major grant to study the impact of COVID-19 on children’s educational, language, social & emotional outcomes

17 Jun 2021

Press Release: Targeted home support could be key in children’s early language development

21 Apr 2021

Related Publications

Recruitment and Retention of Senior School Leaders in Wales

Research Report

Domestic Abuse and Schools: Evidence from the Supervision for Designated Safeguarding Leads Evaluations

04 Jul 2023

Supervising Designated Safeguarding Leads in Primary Schools

27 Apr 2023

Supervision for Designated Safeguarding Leads Scale-Up Evaluation

Four major challenges facing Britain’s education system after the pandemic

Associate Pro Vice Chancellor for Student Inclusion and Professor of Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, University of East Anglia

Disclosure statement

Helena Gillespie's research is funded by Erasmus+ and has previously been funded by Advance HE and HEFCE. She is a school governor, multi academy trust member and director of Norfolk Cricket Board.

University of East Anglia provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

The UK goverment’s Department for Education has some new ministers in charge following the political turmoil surrounding Boris Johnson’s resignation. After resigning only two days into the job of education secretary, Michelle Donelan has been replaced by James Cleverly , MP for Braintree.

Donelan’s former role overseeing higher education has been filled by Andrea Jenkyns, MP for Morley and Outwood, who has been named skills, further and higher education minister . Jenkyns’ credentials as an educational leader were called somewhat into question when she was photographed making a gesture to the public gathered outside Downing Street that would certainly have landed her in detention.

While these appointments can be considered, to some extent, to be caretaker roles pending the appointment of the new prime minister in early September, the new ministers still face significant challenges as they oversee schools, colleges and universities. Here are four issues facing them as they get to work.

Getting exams back to normal

The first hurdle comes next month with the annual round of GCSE and A-level exam results. This will be the first cohort since 2019 to have formally sat their exams. The Department of Education will be hoping that the exam results, which have already been taken and marked, will not cause such headline grabbing disruption this summer as in the two previous years.

In 2020, the first year that exams were cancelled due to the pandemic, results were overturned after it became clear that the algorithm used by the government to standardise grades was penalising students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Pupils could choose to use teacher assessments to decide grades instead.

In 2021, the government again elected to use teacher assessment to decide results, but the approach resulted in many more top grades. The jump in A grades at A-level, from 38% to 44%, meant that there were not enough places at top universities to go around – and universities had to offer prospective students packages of support to persuade them to defer to a 2022 start .

However, it is likely that the return to exams will mean a drop in grades from 2021, and there may be many disappointed students and parents. Weathering grade fluctuations in future years while also closing gaps in attainment for students from disadvantaged backgrounds will be a difficult trick to pull off.

Addressing inequality

In November 2020, the Department of Education launched its flagship initiative to address pandemic learning loss in England, the National Tutoring Programme – which pairs schools with tutors who work with individual students or small groups to help them catch up in core subjects.

However, the House of Commons Education Committee recently reported that the National Tutoring Programme is failing to make an impact in the schools in deprived areas where children are most behind with their education.

Read more: The government's academic catch-up strategy is failing children in England

Problems with the catch-up strategy are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to endemic inequalities in education in the UK. School buildings in many areas are facing pressure from growing class sizes and wear and tear. A 2021 report by the Department for Education put the backlog of school maintenance in England at a cost of £11.4 billion, an eye watering sum at a time of economic crisis.

It is difficult to see how schools can level up for their pupils in buildings that are falling down. The education secretary must hope for sympathy and support around the new cabinet table to access the funds needed.

Provide support for teachers

The pandemic has had a serious impact on children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing and the problem remains acute. One of the short-term impacts of this is growing pressures on teachers in classrooms. For this reason as well as the rise in the cost of living, teachers are asking for a substantial pay increase .

It seems unlikely that current proposals for pay rises in schools, which sit below the rate of inflation, will stop a ballot on strike action or address teacher shortages caused by so many leaving the profession. If the new minister is to be able to deliver meaningful educational recovery, schools are going to need to be better staffed and better supported by other sector agencies. Achieving this looks both difficult and expensive.

Free speech in higher education

On 27 June 2022, before her promotion to education secretary and subsequent resignation, Michelle Donelan had written to university vice chancellors advising them to consider whether their membership of certain diversity schemes was appropriate given their responsibility to uphold free speech. This was regarded with concern by many in the education sector as a move that blurred the lines between appropriate regulation and university autonomy.

In addition, the controversial Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Bill, which seeks to ensure that free speech is protected on campus by limiting the “no-platforming” of speakers, is currently passing through the House of Lords. However, a recent survey has found that 61% of students think that universities should prioritise protecting students from discrimination rather than permitting unlimited free speech.

The new Department for Education team has much to do to ensure that good decisions are made on behalf of the UK’s children and young people.

This article was amended on July 19 2022 to reflect that the National Tutoring Programme and Condition of School Buildings Survey refer to England.

- UK universities

- Exam results

- Learning loss

- Department for Education

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Partner, Senior Talent Acquisition

Deputy Editor - Technology

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Academic and Student Life)

- +44 (0) 2033 189 380 (UK)

- +880 1407-093812 (Dhaka)

- +447305319797

- [email protected]

- Testimonial

- Work With Us

- Foundation Courses

- Undergraduate Courses

- Postgraduate Courses

- Professional Courses

- Research Programme

- Online Courses

- Universities

- Student Service

- Partner Service

- Accommodation

- Book Appointment

Challenges Facing the UK Higher Education Sector

The UK higher education sector has long been known for its excellence, attracting students from all over the world to study at prestigious institutions. However, in recent years, the sector has faced numerous challenges threatening its continued success. Rising tuition fees, increased competition for international students, and changing regulatory frameworks are just some of the issues that UK higher education institutions must navigate. This essay will explore the challenges facing the UK higher education sector and discuss possible solutions to ensure its continued success.

What Are the Challenges Facing Higher Education in the UK?

Throughout the years, UK universities have reliably positioned among the world’s best. This doesn’t come as a surprise, given the facilities and the quality of teaching. Be that as it may, just like in any other part of the globe, there are various impediments that the UK government must conquer, a large portion of which is a result of the current political atmosphere. The following list is the most noticeable challenges facing UK higher education.

The UK wants to leave the European Union bloc; this has created a lot of uncertainties surrounding the conditions of the country’s departure. With the country’s imminent release, many people expect the freedom of movement within the region to be disturbed.

This, in particular, is a cause for concern for many universities, given that it has previously facilitated exchange programs such as ERASMUS. Also, there is ambiguity over whether academics from the EU bloc will continue practicing in the UK.

As a result of the uncertainties, UK universities may lose their cultural richness and face financial challenges as more international students abstain from pursuing higher education in these institutions.

2. Dwindling International Reputation

It is given that the Brexit discussion will be finished before long. However, the repercussions of such a move are expected to be extensive. Brexit has brought about a few scenarios that adversely impact the UK’s worldwide higher education standing.

For example, the migration guidelines may be unfavorable to UK higher education. Previously, staff in various institutions across the nation was 16% and 12% from the EU and outside the EU. This implies that many of these personnel may leave the nation, denying its much-needed expertise. Besides, research funding vulnerabilities are neutralizing the institutions’ worldwide standing.

Current information shows that the nation’s universities are on a downward trajectory, which has seen Japan supplant the UK as the second most represented country in the global ranking. Regardless of whether the descending pattern remains, it is clear that proactive measures should be taken to turn around the reputation.

3. International Competition

Besides losing its long-standing position to Japan, other countries are gaining ground representing another cause for concern. Apart from Japan, other countries such as China have improved their education levels, thus enhancing their global ranking. Also, the current political climate has allowed students to choose countries in the Oceania region rather than in the UK.

Nevertheless, it is right to point out that some determinants are beyond the reach of the institutions. For instance, the aftermath of the negotiations will profoundly impact the institutions’ global reputations.

4. Fee Challenges Within the Higher Education

Various quotas have been proposed the lower the tuition fee within the country. The change aims to have the universities charge less for all courses deemed cheap to run. However, this move attracted widespread criticism across the country.

Many people argued that by so doing, the government would lock out students from poor backgrounds from pursuing courses that would charge more, especially those that are science-oriented, which is already proving to be a challenge.

5. Shifting Research Funding

When it comes to research funding, UK universities benefit significantly from the kitty received from the EU. For example, between 2007 and 2013, UK universities received five hundred million pounds as research funding. However, this position is jeopardized by the country’s looming departure from the EU bloc, causing anxiety among academics and institutions.

Although the current funding is expected to continue up until this year, there is a lot of uncertainty surrounding the source of financing once the deal is over. Failure to have adequate research funding would have adverse effects on the country’s progress and global ranking.

6. Increased Cost

It takes a great deal of investment for an institution to remain competitive. This has led to many universities dedicating funds to investing in personnel, infrastructure, and the necessary student facilities. This has increased the costs, resulting in increased students’ expectations.

However, according to Deloitte, the sector has reacted positively to this challenge. For example, institutions of higher learning have managed to cut costs, saving more than in previous periods. This said, each institution should have its strategies to help mitigate the effects posed by this challenge.

7. Attracting and Retaining the Best Talent

Higher education institutions must work towards hiring the right personnel to ensure they attain their corporate strategies and priorities. Universities might not be in a position to attract the required talent post-Brexit. This will have further implications for the sector in the long run.

However, the institutions should not shy away from recruiting from the corporate world to help in their management functions. As such, universities should work to align the incentives while also being sensitive to the implications the move may have on the institution’s culture.

8. Student Well-being

The rate of suicide and other mental-related illnesses has been rising among students. Also, issues such as drug abuse and sexual harassment have been reported as some of the problems currently affecting the students. This means the respective institutions of higher learning must devise ways to curb these problems.

However, providing the necessary support might be in jeopardy as it heavily relies on the fund received. This means the universities will be pressured into finding other sources of finances, which might not be easy.

9. Protecting Free Speech

The issue has elicited mixed reactions when it comes to free speech within the universities. Many people think that giving a platform for free speech will increase controversial speakers; however, other quotas believe that not providing such a platform inhibits free speech. This means the universities must balance external pressure on what they believe is permissible in the institutions.

Final Words

In conclusion, the UK higher education sector is facing various challenges, including rising tuition fees, competition for international students, and changing regulations. However, with strategic planning, innovative approaches, and collaboration, these challenges can be overcome, and the sector can continue to thrive and provide quality education to students from all over the world.

Tags: challenges in higher education UK, global challenges in higher education, challenges facing the higher education sector UK, challenges facing higher education, challenges in higher education, uk education system problems, the greatest challenges facing higher education, challenges facing universities, issues facing higher education today, issues facing higher education students, uk higher education system.

Share this post

Leave a reply cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Related Posts

MOI Accepted Universities in UK

Medium of Instruction or MoI certificate is as an official record,... read more

5 Best Universities in USA for International Students in 2024

Looking for top-notch education in the USA? Our blog on "Best... read more

Scholarships For Pakistani Students In Canada

Ever wondered why Canadian education is becoming increasingly appealing to Pakistani... read more

What is Secure English Language Test (SELT)

Are you going to apply for SELT? What is secure english... read more

We Are Hiring

Job Title: Business Development Executive Identify the potential partnership opportunities with local... read more

Best Colleges In Europe in 2024

Although universities and colleges are the two mediums for higher education,... read more

How to Apply Dependent Visa For UK?

A dependent visa in the UK allows immediate family members of... read more

Predicting the Impact of the UK’s Dependents Policy Change on International Students

The UK government's recent policy change to restrict the entry of... read more

Boost Education Service is Rebranding to BHE UNI

Your most trusted university representative, Boost Education Service, which has been... read more

Duolingo Accepted Universities in the UK 2024

Standardized English Language Proficiency score is necessary for higher studies in... read more

[mailerlite_form form_id=1]

Our Student Says

It was a wonderful experience from the BOOST EDUCATION, they helped me a lot in my study program for the University of Roehampton Landon. Boost Education gives me the right counseling, helped me to select a great university, with the right information. Very professional & helpful to the student.

HENRY SMITH, GHANA University of Roehampton (QAHE) - Bsc (Hons) Computing Techinology - September 2018

Boost Education staffs are very professional and expert for the University admission. Also, they are very helpful and friendly

ANNA ANATOLIEVA Roehampton Universtiy London (QAHE) - Bsc(Hons) Business Management - May 2017

Boost Education service helped a lot for my higher education opportunities in the UK, they always provided me correct information and guidance for the University admission and visa processing

MEHEDI HASAN The University of West of Scotland - Doctor of Business Administration (DBA) - July 2018

Extremely efficient and cooperative team

CATALINE LOANA BUCUR Arden University - BA(Hons) in Business - January 2018

4 trends that will shape the future of higher education

Higher education needs to address the problems it faces by moving towards active learning, and teaching skills that will endure in a changing world. Image: Vasily Koloda for Unsplash

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Diana El-Azar

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Education is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

Listen to the article

- Measures adopted during the pandemic do not address the root causes of the problems facing higher education.

- Institutions need to undertake true reform, moving towards active learning, and teaching skills that will endure in a changing world.

- Formative assessment is more effective than high-stakes exams in equipping students with the skills they need to succeed.

Since the onset of the recent pandemic, schools and universities have been forced to put a lot of their teaching online. On the surface, this seems to have spurred a series of innovations in the education sector. Colleges around the world embraced more flexibility, offering both virtual and physical classrooms. Coding is making its way into more school curricula , and the SAT exam for college admission in the US has recently been shortened and digitized , making it easier to take and less stressful for students.

These changes might give the illusion that education is undergoing some much-needed reform. However, if we look closely, these measures do not address the real problems facing higher education. In most countries, higher education is inaccessible to the socio-economically underprivileged, certifies knowledge rather than nurtures learning, and focuses on easily-outdated knowledge. In brief, it is failing on both counts of quality and access.

Have you read?

Four ways universities can future-proof education, the global education crisis is even worse than we thought. here's what needs to happen, covid-19’s impact on jobs and education: using data to cushion the blow, higher education trends.

In the last year, we have started to see examples of true reform, addressing the root causes of the education challenge. Below are four higher education trends we see taking shape in 2022.

1. Learning from everywhere

There is recognition that as schools and universities all over the world had to abruptly pivot to online teaching, learning outcomes suffered across the education spectrum . However, the experiment with online teaching did force a reexamination of the concepts of time and space in the education world. There were some benefits to students learning at their own pace, and conducting science experiments in their kitchens . Hybrid learning does not just mean combining a virtual and physical classroom, but allowing for truly immersive and experiential learning, enabling students to apply concepts learned in the classroom out in the real world.

So rather than shifting to a “learn from anywhere ” approach (providing flexibility), education institutions should move to a “learn from everywhere ” approach (providing immersion). One of our partners, the European business school, Esade, launched a new bachelor’s degree in 2021, which combines classes conducted on campus in Barcelona, and remotely over a purpose-designed learning platform, with immersive practical experiences working in Berlin and Shanghai, while students create their own social enterprise. This kind of course is a truly hybrid learning experience.

2. Replacing lectures with active learning

Lectures are an efficient way of teaching and an ineffective way of learning. Universities and colleges have been using them for centuries as cost-effective methods for professors to impart their knowledge to students.

However, with digital information being ubiquitous and free, it seems ludicrous to pay thousands of dollars to listen to someone giving you information you can find elsewhere at a much cheaper price. School and college closures have shed light on this as bad lectures made their way into parents’ living rooms, demonstrating their ineffectiveness.

Education institutions need to demonstrate effective learning outcomes, and some are starting to embrace teaching methods that rely on the science of learning. This shows that our brains do not learn by listening, and the little information we learn that way is easily forgotten (as shown by the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve , below). Real learning relies on principles such as spaced learning, emotional learning, and the application of knowledge.

The educational establishment has gradually accepted this method, known as 'fully active learning'. There is evidence that it not only improves learning outcomes but also reduces the education gap with socio-economically disadvantaged students. For example, Paul Quinn College, an HBCU based in Texas, launched an Honors Program using fully active learning in 2020, combined with internships at regional employers. This has given students from traditionally marginalised backgrounds the opportunity to apply the knowledge gained at university in the real world.

3. Teaching skills that remain relevant in a changing world

According to a recent survey, 96% of Chief Academic Officers at universities think they are doing a good job preparing young people for the workforce . Less than half (41%) of college students and only 11% of business leaders shared that view. Universities continue to focus on teaching specific skills involving the latest technologies, even though these skills and the technologies that support them are bound to become obsolete. As a result, universities are forever playing catch up with the skills needed in the future workplace.

What we need to teach are skills that remain relevant in new, changing, and unknown contexts. For example, journalism students might once have been taught how to produce long-form stories that could be published in a newspaper; more recently, they would have been taught how to produce shorter pieces and post content for social media. More enduring skills would be: how to identify and relate to readers, how to compose a written piece; how to choose the right medium for your target readership. These are skills that cross the boundaries of disciplines, applying equally to scientific researchers or lawyers.

San Francisco-based Minerva University, which shares a founder with the Minerva Project, has broken down competencies such as critical thinking or creative thinking into foundational concepts and habits of mind . It teaches these over the four undergraduate years and across disciplines, regardless of the major a student chooses to pursue.

4. Using formative assessment instead of high-stake exams

If you were to sit the final exam of the subject you majored in today, how would you fare? Most of us would fail, as that exam did not measure our learning, but rather what information we retained at that point in time. Equally, many of us hold certifications in subject matters we know little about.

Many people gain admission to higher education based on standardized tests that skew to a certain socio-economic class , rather than measure any real competency level. Universities then try to rectify this bias by imposing admission quotas, rather than dissociating their evaluation of competence from income level. Many US universities are starting to abandon standardized tests, with Harvard leading the charge , and there have been some attempts to replace high-stake exams with other measures that not only assess learning outcomes but actually improve them.

Formative assessment, which entails both formal and informal evaluations through the learning journey, encourages students to actually improve their performance rather than just have it evaluated. The documentation and recording of this assessment includes a range of measures, replacing alphabetical or numerical grades that are uni-dimensional.

The COVID-19 pandemic and recent social and political unrest have created a profound sense of urgency for companies to actively work to tackle inequity.

The Forum's work on Diversity, Equality, Inclusion and Social Justice is driven by the New Economy and Society Platform, which is focused on building prosperous, inclusive and just economies and societies. In addition to its work on economic growth, revival and transformation, work, wages and job creation, and education, skills and learning, the Platform takes an integrated and holistic approach to diversity, equity, inclusion and social justice, and aims to tackle exclusion, bias and discrimination related to race, gender, ability, sexual orientation and all other forms of human diversity.

The Platform produces data, standards and insights, such as the Global Gender Gap Report and the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion 4.0 Toolkit , and drives or supports action initiatives, such as Partnering for Racial Justice in Business , The Valuable 500 – Closing the Disability Inclusion Gap , Hardwiring Gender Parity in the Future of Work , Closing the Gender Gap Country Accelerators , the Partnership for Global LGBTI Equality , the Community of Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officers and the Global Future Council on Equity and Social Justice .

The International School in Geneva just launched its Learner Passport that includes measures of creativity, responsibility and citizenship. In the US, a consortium of schools have launched the Mastery Transcript Consortium that has redesigned the high school transcript to show a more holistic picture of the competencies acquired by students.

Education reform requires looking at the root cause of some of its current problems. We need to look at what is being taught (curriculum), how (pedagogy), when and where (technology and the real world) and whom we are teaching (access and inclusion). Those institutions who are ready to address these fundamental issues will succeed in truly transforming higher education.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Education .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

How universities can use blockchain to transform research

Scott Doughman

March 12, 2024

Empowering women in STEM: How we break barriers from classroom to C-suite

Genesis Elhussein and Julia Hakspiel

March 1, 2024

Why we need education built for peace – especially in times of war

February 28, 2024

These 5 key trends will shape the EdTech market upto 2030

Malvika Bhagwat

February 26, 2024

With Generative AI we can reimagine education — and the sky is the limit

Oguz A. Acar

February 19, 2024

How UNESCO is trying to plug the data gap in global education

February 12, 2024

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Foreign students may be undermining UK higher education, says Cleverly

Home secretary calls for visa review over concern that courses are being used as shortcut to gain work permits

- UK politics – latest updates

The home secretary, James Cleverly , has said international students may be “undermining the integrity and quality of the UK higher education system” by using university courses as a cheap way of getting work visas.

In a letter to the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC), Cleverly asked the body to investigate whether the graduate visa entitlement – allowing international students to work for two or three years after graduating – was failing to attract “the brightest and the best” to the UK.

But university leaders fear that cutting or restricting the graduate visa route will lead to a drastic fall in international recruitment, and provoke a financial crisis for universities that rely on income from international tuition fees.

Cleverly told the MAC that while the government was committed to attracting “talented students from around the world to study in the UK”, it also wanted “to ensure the graduate route is not being abused. In particular, that some of the demand for study visas is not being driven more by a desire for immigration”.

Cleverly said: “An international student can spend relatively little on fees for a one-year course and gain access to two years with no job requirement on the graduate route, followed by four years’ access to a discounted salary threshold on the skilled worker route.

“This means international graduates are able to access the UK labour market with salaries significantly below the requirement imposed on the majority of migrant skilled workers.”

The home secretary instructed the committee, which gives independent advice to the government, to investigate “any evidence of abuse” of the graduate route, “including the route not being fit for purpose”, and to look at which universities were producing graduates who used the route.

He also asked the MAC to analyse “whether the graduate route is undermining the integrity and quality of the UK higher education system, including understanding how the graduate route is or is not, effectively controlling for the quality of international students, such that it is genuinely supporting the UK to attract and retain the brightest and the best, contributing to economic growth and benefiting British higher education”.

Rachel Hewitt, the chief executive of the MillionPlus group of universities, said the government’s review appeared to be deliberately aimed at undermining the success of British higher education.

“It is impossible to imagine the government going out of its way to make Britain less inviting to investment in almost any other sector – and yet every negative headline and policy reform makes Britain less attractive to international students,” Hewitt said.

“The graduate route is a key component of the offer that UK universities can make to international applicants, and its value should be recognised and not eroded.”

Jamie Arrowsmith, the director of Universities UK International, said universities were “deeply concerned” by the short notice given by Cleverly.

after newsletter promotion

“Post-study work matters for many international students, allowing those who have invested in our country the opportunity to find work and contribute to the UK economy,” said Arrowsmith.

“Having publicly recommitted to the graduate route on its current terms in May 2023, any further changes would be extremely damaging to our reputation as a welcoming destination for international students, and risks undermining a UK success story that generates more than £20bn a year in export earnings for the economy.”

Cleverly said “early data” showed that just 23% of international students using the skilled workers route moved into graduate-level jobs, and that last year only a third moved into jobs paying more than £26,000 a year.

The committee is expected to report back in May, and its findings could come at a difficult time for the higher education sector. So far this year, enrolments from overseas have fallen by 40% compared with 2023.

Vanessa Wilson, chief executive of the University Alliance group, said: “It is important that international students have the opportunity to study at the full range of UK universities so they can select the option that is right for them, and so that all UK students and regions can benefit from their contributions.”

- International students

- Immigration and asylum

- James Cleverly

- University funding

- Universities

- Higher education

Home Office asks for emergency £2.6bn after asylum seeker hotels overspend

British students not being ‘squeezed out’ by overseas applicants, say universities

Jimmy Dimly lights our way to the glorious gospel of Rish!

University of York to accept some overseas students with lower grades

Fifth of UK universities’ income comes from overseas students, figures show

Cleverly admits ‘awful’ joke could have distracted from work to tackle spiking

James Cleverly facing calls to resign after joke about date rape drug

English universities warned not to over-rely on fees of students from China

British universities can no longer financially depend on foreign students. They must reform to survive

James Cleverly apologises for ‘appalling’ date rape drug joke at No 10 event

Most viewed.

Major policy issues facing higher education: a plea for nuance

- 2 March 2021

- By Nick Hillman

This is an extract from a speech delivered yesterday by Nick Hillman, HEPI’s Director, to an event in the Mills & Reeve Higher Education Week.

Students as consumers

Five years ago, our host, Gary Attle, told in a HEPI paper how students had gradually come to be treated more like consumers. He started by recalling how the concept of students-as-consumers had once been entirely alien, using the words of Mr Justice Wills in 1896:

I cannot think of anything more fatal to discipline than the notion that a contractual relationship exists between the college and its undergraduates.

Exactly a century later, in 1996, some students started an HND in historical vehicle restoration a couple of miles down the road from where I live, at Rycotewood College in Thame . The staff and students dismantled a car but, like Humpty Dumpty, they couldn’t put it back together again. A judge later found, ‘ None of the teaching staff had any practical experience at all as professional old car restorers ’.

Unsurprisingly, the students complained. Years later, a court ruled they should get £10,000 compensation each, including £2,500 for mental distress, with more for the student whose car had been taken apart. It was a clear example of students being treated more like consumers.

Since then, the shift towards high fees and loans (in England and Wales) and the growing interest of bodies like the Competition and Markets Authority in higher education have accelerated the trend. The key insight of the most recent HEPI paper , by Rosie Bennett, a former journalist at The Times , is that universities have become ‘the ultimate consumer story.’

The disruption caused by COVID means practice is still evolving. On Tuesday, the Office of the Independent Adjudicator for Higher Education ( OIAHE ) for England and Wales will publish its next set of case studies on dealing with complaints during the COVID crisis. I urge people to read them.

Higher education institutions have rejected the idea of across-the-board refunds in the current crisis. Such payments could affect the financial sustainability of some institutions and there are three other good reasons why blanket restitution has not been forthcoming.

- First, teaching is still happening, albeit differently from normal. Where there are particularly big challenges, such as with placements and practice-based courses, the Quality Assurance Agency’s guidance has outlined what providers should do.

- Secondly, good teaching and good student support services cost a lot of money whether delivered in person or online: no one says schools should get fewer resources in the crisis, as the challenges of teaching children during a pandemic are widely acknowledged. The same arguments apply to higher education.

- Thirdly, there is a mature complaints system at both an institutional and a sector-wide level. This may not be as well understood as it should be, but it can lead to compensation. Students should make use of it when they feel they have a robust case.

There may be an argument, as Anthony Seldon wrote in a recent HEPI blog , for the Government to compensate students. But an automatic mass refund scheme is more difficult than is often recognised because over half the costs of the current system are paid by taxpayers rather than students or graduates, thanks to the progressive repayment system.

In short, the current debate about restitution for students is hard because we have a hybrid model of student funding that trades off different priorities against one another:

- it expects a hefty financial contribution from better-off graduates…

- …but taxpayers willingly pick up the tab for those who earn less…

- …and there are no limits on student places in England – which could prove especially useful with the expected further bout of grade inflation this summer .

Trade offs in higher education policy

I start this way because the question of whether students are consumers and whether they should receive refunds illustrates a broader truth about current higher education policy debates: we are at risk of treating complex questions as if they are simple. The big issues are often portrayed in monochrome rather than full technicolour.

- On funding , two years on from the appearance of the Augar report, Ministers have still not ruled out a big cut in tuition fees and some elements of Whitehall clearly want a university education to be delivered for less . Yet a reduction in funding for teaching could leave universities with a binary choice for stemming their losses: either shutting courses or piling students in as a way of chasing a higher income. However, as the recent row about the subject English at the University of Leicester shows, institutions are under pressure not to close courses and we have also been told the era of expansion is over .

- On access , thanks in part to the work of the Office for Students, there is a better understanding than in the past of the benefits of contextualisation in university admissions, whereby applicants’ backgrounds are taken into account. Yet the Office for Students also now want the background of students at higher education institutions to be deemed irrelevant when judging institutional performance . As we showed in a paper on non-continuation rates published in January, unless this is implemented carefully it could risk disincentivising the recruitment of disadvantaged students in the first place.

- On free speech , headlines have been won for the idea of appointing a new Free Speech and Academic Freedom Champion. We recently ran a blog supporting the idea by Arif Ahmed from the University of Cambridge but we have also published the warnings of Nigel Copsey , a historian of anti-fascism at Teesside University, who says the approach could prove counter-productive if is provides succour to provocateurs posing as advocates of free speech.

- On raising skills , we have fewer people whose highest qualification is at Levels 4 and 5 (what used to be called ‘sub-degree’) than our competitors. There is a consensus that we need more skills at these Levels, but this is often accompanied by alongside the idea that we have too many graduates . In fact, the data suggest the reason we have too few people whose highest qualification is at Levels 4 or 5 is that we have too many people whose education topped out too early, at Levels 2 and 3 – it is not because we have too many graduates relative to other developed countries or the needs of the economy.

- Not long ago, the autonomy of universities was confirmed in the Higher Education and Research Act (2017). Yet some recent political interventions – for example, on admissions – suggest autonomy may be falling out of vogue. If universities are not entirely free to compile students’ reading lists , autonomy loses meaning.

- The English regulatory model is based on the idea that student interests should be paramount – that’s why we have an ‘Office for Students’. But the primary official way of capturing the student voice, the National Student Survey (NSS), is having a ‘radical review’ and will have ‘at most a minimal role’ in judging the future quality of provision. This seems the wrong way around to me: the limitations of the NSS are unlikely to be fixed by slimming it down and making it less meaningful. At the moment, the annual HEPI / Advance HE Student Academic Experience Survey remains the best source of information on a wide range of issues – such as contact hours, workload, class sizes, well-being and value-for-money perceptions – and, frankly, we would welcome some competition.

Rather than acting as if such policy areas are black-and-white, we would do better to expose inherent complexities, reflect upon them and then embed them in policymaking. Voters know instinctively that smart policymaking happens at the crossroads where trade offs occur – the current COVID crisis is all about trade offs, such as when to lock down and when to open up, who should get vaccines first and which sectors of the economy to support the most. The four vice-chancellors that HEPI and Advance HE brought together last week for a Question Time were united in believing higher education policymaking should become more nuanced.

My concern that current policy is too one dimensional is not just directed at the UK Government at Westminster. The trade offs in higher education policy are reduced to oversimplistic alternatives in other parts of the UK and by other political parties too.

- When the Official Opposition say their commitment to abolishing tuition fees remains in place, no one explains how this can be adequately funded given the impending growth in 18-year olds .

- In the run up to the Scottish Parliament election this May, politicians from the SNP to the Scottish Conservatives are stressing the progressive features of ‘free’ higher education but without explicitly recognising this has meant the retention of student number controls.

- In some parts of the trades union movement, there has been insufficient recognition of the trade offs between the high costs of employing permanent staff (because of things like existing pension entitlements ) and the precarious contracts of early career staff.

Such trade offs need to be discussed, not brushed under the carpet. For when you recognise trade offs exist, you have to decide how far to give way on any issue in the interests of other valuable concepts worth protecting. So the question is not how to reject any trade offs; it is how to get the balance right when responding to them.

Share this:

Really interesting. Absolutely agree we need more nuance and honesty. Do you have a data source to back up the statement:

‘the data suggest the reason we have too few people whose highest qualification is at Levels 4 or 5 is that we have too many people whose education topped out too early, at Levels 2 and 3’?

The complexity of HE needs to be recognised and trade offs are inevitable given the restrictions on funding. However, I disagree with any plans to increase funding for Universities. We have too many students / graduates and post graduates for the “needs of the economy “ – ask any employer.

When it comes to trade offs, we have too little investment in education for those below the age of 16. To help those from disadvantaged backgrounds we must start well before the age of 18 to release potential and support inherent talent and those with the energy, ability and determination to succeed and prosper.

The whole of our education system needs to improve its productivity, efficiency and effectiveness while creating a much better understanding of what society is seeking to achieve from educating the population and how we will measure success.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

- Current Affairs

Challenges for UK Higher Education and Research Post Brexit

The UK’s exit from the European Union has presented many challenges for the higher education and research sectors. Major challenges exist through changes to immigration policy, restrictions on access to funding and general lack of clarity or continuity in regulation. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has led with more conciliatory overtones than his immediate predecessors and through the developing Windsor Framework, we are seeing an evolving relationship between the EU and UK on higher education and research.

Challenges facing researchers

Research institutions and Universities are reliant on a continued entry of new undergraduate cohorts. Whilst the total number of foreign domiciled students has continued to increase, with the most notable origin countries being China and India with increases of 41% and over 500% between 2017/18 and 2021//22. Whereas since Brexit there has been a marked decline in EU domiciled students overall. Students have declined from 2017/18 to 2021/22 from selected EU countries.

Contributing to the decline are changes in UK immigration policy, removal of government backed funding and increases in tuition fee rates. Compounding this is the UK’s 2020 choice to leave the Erasmus+ scheme, creating the Turing scheme to replace it. The Turing scheme is open to a wider range of countries and intended to promote students from Commonwealth countries and beyond in place of the EU. EU students and researchers have to apply for a visa, due to the removal of freedom of movement, further contributing to the decline.

UK Research Environment

UK based research is funded through a mix of private sector and public sector research councils, for example the UKRI challenge fund is made up of £2.6 billion from the UK government and £3 billion from the private sector.. However this varies by technology readiness level, the higher the technology readiness level the greater the mix of private sector funding.

Public funding is derived through UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) which in turn funds flagship facilities such as the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory (RAL) and Daresbury complex. UKRI also funds research councils which fund the majority of University based research. UKRI funding draws from the two government departments and EU funding, which is due to conclude in 2027.

Whilst the UK government has committed to matching certain prior EU funding levels, this is still not concrete and may affect climate change, biomedical and computer science/AI research. In theory this will allow more fundamental early stage research to take place, however there are concerns over continued sustained private sector funding. UK inward investment has dropped by 35% between 2016 and 2020. This has resulted in a drop from private sector funding both inside and outside the UK. This results from reduced access to the single market, divergent legislation since Brexit and the general economic outlook. Further existent barriers include potential ATAS certification which prevents some collaboration with researchers outside of the UK.

How can the UK attract researchers