Four of the biggest problems facing education—and four trends that could make a difference

Eduardo velez bustillo, harry a. patrinos.

In 2022, we published, Lessons for the education sector from the COVID-19 pandemic , which was a follow up to, Four Education Trends that Countries Everywhere Should Know About , which summarized views of education experts around the world on how to handle the most pressing issues facing the education sector then. We focused on neuroscience, the role of the private sector, education technology, inequality, and pedagogy.

Unfortunately, we think the four biggest problems facing education today in developing countries are the same ones we have identified in the last decades .

1. The learning crisis was made worse by COVID-19 school closures

Low quality instruction is a major constraint and prior to COVID-19, the learning poverty rate in low- and middle-income countries was 57% (6 out of 10 children could not read and understand basic texts by age 10). More dramatic is the case of Sub-Saharan Africa with a rate even higher at 86%. Several analyses show that the impact of the pandemic on student learning was significant, leaving students in low- and middle-income countries way behind in mathematics, reading and other subjects. Some argue that learning poverty may be close to 70% after the pandemic , with a substantial long-term negative effect in future earnings. This generation could lose around $21 trillion in future salaries, with the vulnerable students affected the most.

2. Countries are not paying enough attention to early childhood care and education (ECCE)

At the pre-school level about two-thirds of countries do not have a proper legal framework to provide free and compulsory pre-primary education. According to UNESCO, only a minority of countries, mostly high-income, were making timely progress towards SDG4 benchmarks on early childhood indicators prior to the onset of COVID-19. And remember that ECCE is not only preparation for primary school. It can be the foundation for emotional wellbeing and learning throughout life; one of the best investments a country can make.

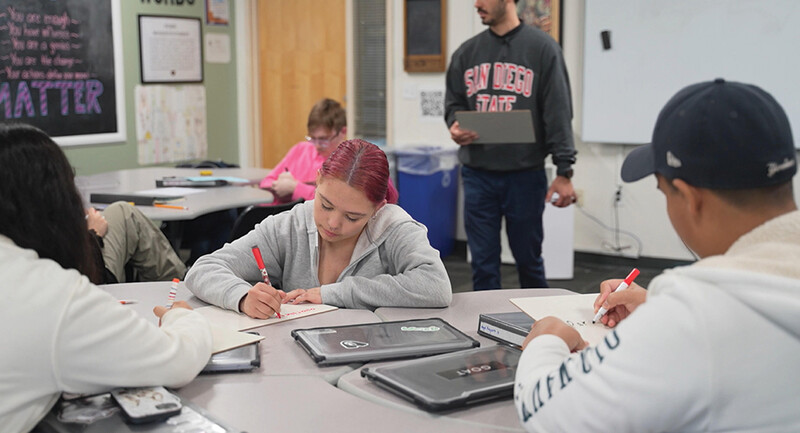

3. There is an inadequate supply of high-quality teachers

Low quality teaching is a huge problem and getting worse in many low- and middle-income countries. In Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, the percentage of trained teachers fell from 84% in 2000 to 69% in 2019 . In addition, in many countries teachers are formally trained and as such qualified, but do not have the minimum pedagogical training. Globally, teachers for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) subjects are the biggest shortfalls.

4. Decision-makers are not implementing evidence-based or pro-equity policies that guarantee solid foundations

It is difficult to understand the continued focus on non-evidence-based policies when there is so much that we know now about what works. Two factors contribute to this problem. One is the short tenure that top officials have when leading education systems. Examples of countries where ministers last less than one year on average are plentiful. The second and more worrisome deals with the fact that there is little attention given to empirical evidence when designing education policies.

To help improve on these four fronts, we see four supporting trends:

1. Neuroscience should be integrated into education policies

Policies considering neuroscience can help ensure that students get proper attention early to support brain development in the first 2-3 years of life. It can also help ensure that children learn to read at the proper age so that they will be able to acquire foundational skills to learn during the primary education cycle and from there on. Inputs like micronutrients, early child stimulation for gross and fine motor skills, speech and language and playing with other children before the age of three are cost-effective ways to get proper development. Early grade reading, using the pedagogical suggestion by the Early Grade Reading Assessment model, has improved learning outcomes in many low- and middle-income countries. We now have the tools to incorporate these advances into the teaching and learning system with AI , ChatGPT , MOOCs and online tutoring.

2. Reversing learning losses at home and at school

There is a real need to address the remaining and lingering losses due to school closures because of COVID-19. Most students living in households with incomes under the poverty line in the developing world, roughly the bottom 80% in low-income countries and the bottom 50% in middle-income countries, do not have the minimum conditions to learn at home . These students do not have access to the internet, and, often, their parents or guardians do not have the necessary schooling level or the time to help them in their learning process. Connectivity for poor households is a priority. But learning continuity also requires the presence of an adult as a facilitator—a parent, guardian, instructor, or community worker assisting the student during the learning process while schools are closed or e-learning is used.

To recover from the negative impact of the pandemic, the school system will need to develop at the student level: (i) active and reflective learning; (ii) analytical and applied skills; (iii) strong self-esteem; (iv) attitudes supportive of cooperation and solidarity; and (v) a good knowledge of the curriculum areas. At the teacher (instructor, facilitator, parent) level, the system should aim to develop a new disposition toward the role of teacher as a guide and facilitator. And finally, the system also needs to increase parental involvement in the education of their children and be active part in the solution of the children’s problems. The Escuela Nueva Learning Circles or the Pratham Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) are models that can be used.

3. Use of evidence to improve teaching and learning

We now know more about what works at scale to address the learning crisis. To help countries improve teaching and learning and make teaching an attractive profession, based on available empirical world-wide evidence , we need to improve its status, compensation policies and career progression structures; ensure pre-service education includes a strong practicum component so teachers are well equipped to transition and perform effectively in the classroom; and provide high-quality in-service professional development to ensure they keep teaching in an effective way. We also have the tools to address learning issues cost-effectively. The returns to schooling are high and increasing post-pandemic. But we also have the cost-benefit tools to make good decisions, and these suggest that structured pedagogy, teaching according to learning levels (with and without technology use) are proven effective and cost-effective .

4. The role of the private sector

When properly regulated the private sector can be an effective education provider, and it can help address the specific needs of countries. Most of the pedagogical models that have received international recognition come from the private sector. For example, the recipients of the Yidan Prize on education development are from the non-state sector experiences (Escuela Nueva, BRAC, edX, Pratham, CAMFED and New Education Initiative). In the context of the Artificial Intelligence movement, most of the tools that will revolutionize teaching and learning come from the private sector (i.e., big data, machine learning, electronic pedagogies like OER-Open Educational Resources, MOOCs, etc.). Around the world education technology start-ups are developing AI tools that may have a good potential to help improve quality of education .

After decades asking the same questions on how to improve the education systems of countries, we, finally, are finding answers that are very promising. Governments need to be aware of this fact.

To receive weekly articles, sign-up here

Consultant, Education Sector, World Bank

Senior Adviser, Education

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

- Our Mission

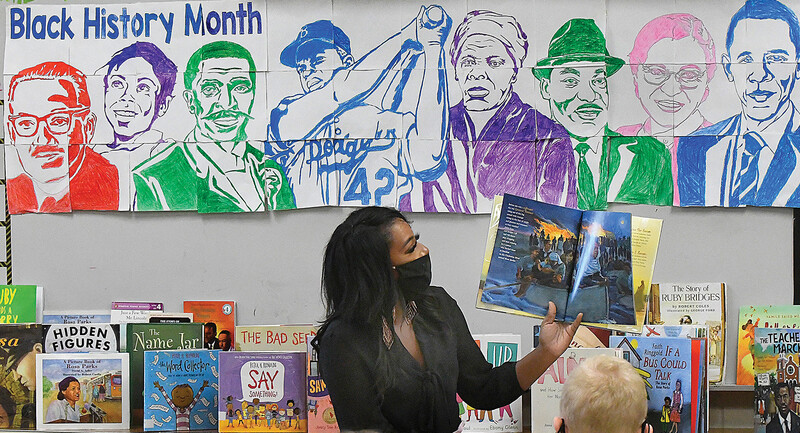

Challenges in Education: A Student’s-Eye View

As many teachers know, the national discussion on education is overcrowded with opinions on teacher training, salaries, tenure, and unions -- with occasional detours through iPads, textbooks, and national policy. In fact, it seems that we listen to every interested party except the one for whom education exists in the first place: students.

We've worked one-on-one with hundreds of students over the last decade, and while they always start from "my teacher hates me" or "I'm just bad at this subject," a change in their own behaviors and beliefs consistently leads to a turnaround in grades. We've seen firsthand all the ways that students can impede their own academic performance. We've seen how parents and our culture at large unwittingly sabotage students' success. And then we've seen our society give teachers full responsibility for a process that is only partially in their hands. That has to stop.

Teachers are essential and influential, guiding their students through new material, drawing out analysis and excitement about ideas. But even the best teacher is helpless against the student looking straight at the board but thinking about lunch. Students are, ultimately, the only party with the ability to truly transform the state of education. And as it turns out, what they have to say is quite telling.

What the Students Are Thinking

A year ago, we were approached by The Princeton Review to help them design a survey about Student Life in America . Rather than focusing on academic performance, they wanted to understand students' academic process. What goes through their heads when they do homework? Where do they turn for help when they're stuck? How do they think and feel during a typical school day? In short, the survey was designed to find out what only students can know: their thoughts, feelings, and goals. The results suggest that if we want to fix education, then we have to move away from blaming teachers, resources, or classroom size, and start talking seriously about what students are doing to create academic success -- and how we can best support them in that process.

Here are some of the survey's most telling results.

Too much homework or too much homework time?

Students readily reported that they spend one-third of their study time stressing out . We hear parents and students constantly complain about teachers assigning too much homework. Based on volume of hours alone, that makes sense. However, what the students have reported provides a totally different picture.

For every three hours that students seem to be spending on homework, only two are productive. Concerns about whether they'll do well, whether they're smart enough to understand the assignment, what grade they have, and how everyone else in class is doing can derail them in a major way. We could cut out that hour so that the work gets done and they can move on. Rather than assigning less homework, we should focus on helping students work more effectively. In preparing students for the modern world, that strategy is essential. In the working world, they won't have time to spend one third of their day unproductively stressing out. They need to learn how to stay on top.

They do care. . . about the wrong things.

One of the most interesting results was that 90 percent of students reported that they want good grades . For an educator, that's thrilling to hear. But only six percent of students want good grades for the sake of learning . Many students are so concerned with grades, tests, and college admissions that they've lost what's really important about school. When they're not succeeding, they feel terrible about school. The irony is that the act of learning in itself releases dopamine, the brain's ultimate feel-good chemical. That’s why those "aha!" moments feel so good. We can help students make that virtuous cycle happen. Better grades and scores matter, but you don’t get them by focusing endlessly on them. Better results come from finding better ways of working -- from improving process.

When students are so obsessed with results -- what they need to learn and what grades they'll get -- that they ignore how learning works. The frequent explanations ("math is stupid" and "my teacher just hates me") are obviously unproductive and untrue. But the survey participants made it clear that we must help students by making sure that they need to know how to learn, manage their stress, ask for help, and get that dopamine kick they deserve.

Here are just a few survey-inspired ways to help your students improve their approach:

1. Do a side-by-side comparison of cramming and learning.

We educators obviously love the subjects we teach and want kids to love learning for its own sake. However, the benefits of learning aren't obvious to students. Help them do a side-by-side comparison of learning and cramming over both the short and long term. While students' preferred strategy of last-minute cramming seems "smart" (why study every night when you can study just one night?), it doesn’t lead to long-term learning. Within hours or days, that material is forgotten, and students end up needing to relearn and refresh basic concepts, month after month or year after year. Also, by choosing to cram the material, students are denying themselves that dopamine release. Since they want to do well in school and have a non-miserable existence, once they realize that actually learning helps them do both, they'll choose it more and more often.

2. Teach your students to substitute action for stress.

Not only is spending one third of your study time freaking out unpleasant, it's a huge waste of time. Doing any small thing that gets your work closer to done is a much better use of time. Getting students to recognize when they're freaking out and substitute that worry for any small, productive action will help them massively reduce the amount of time they spend studying. Best of all, their results will improve, too!

3. Challenge students to produce actionable feedback.

We're all familiar with good and bad tech support, and this is no different. Comments like "Math is stupid" or "When am I going to use this in real life?" often lead to arguments about the virtues of a subject. But the real issue is that when we feel like throwing our computer out the window, it's not because computers are a waste of time. It's because the thing won't work, and we have no idea how to fix it. So we should encourage students to stop discussing results and start discussing actions. Instead of letting them talk in terms of grades and ability, turn the focus to what they actually did and why:

- What steps did you take?

- What could you do differently next time?

- How did you get this answer?

- What specific piece needs improvement?

Solutions at Our Fingertips

The fixes that come from listening to kids don’t require more money, more resources, or consensus in Congress. Talking to our elected leaders doesn't seem to have fixed education. Talking to our kids just might.

How have you gotten your students to take charge of their learning in the classroom? What strategies do you use to help students manage stress? What are your policies for making sure that students can come to you for help? We'd love to hear your thoughts and experiences in the comments section below.

Smithsonian Voices

From the Smithsonian Museums

SMITHSONIAN EDUCATION

Teaching About Real-World, Transdisciplinary Problems and Phenomena through Convergence Education

In its 2018 Federal STEM Strategic Plan, a collaboration of government agencies wrote that science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education should move through a pathway where disciplines “converge” and where teaching and learning moves from disciplinary to transdisciplinary. Classroom examples help spotlight what this framework can look like in practice.

Carol O’Donnell & Kelly J. Day

:focal(356x275:357x276)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4f/18/4f18e5c8-9a86-4a92-9668-2de7e8c3cdac/picture1.jpg)

In today’s K-12 classrooms, students are learning a lot more than just reading, writing, and arithmetic. Today, problem- and phenomenon-based learning means that students are tackling some of the most complex topics of our times, whether it is cybersecurity, innovation and entrepreneurship, climate change, biodiversity loss, infectious disease, water scarcity, energy security, food security, or deforestation. Educators are using transdisciplinary learning to help students address deep scientific questions and tackle broad societal needs.

Convergence Education

But how does an educator, who is assigned to teach one discipline (e.g., reading, writing, math, science, social studies, or art) bring together multiple disciplines to teach about complex socio-scientific problems or opportunities? Researchers at the National Science Foundation (NSF) call this “ convergence ”, and say that it has three primary characteristics:

- A deep scientific phenomenon (that is, an observable event or happening that can be explained, such as clean groundwater);

- An emerging problem (that is, something that can be solved through the development of an object, tool, process or system and includes multiple criteria and constraints, such a new water filtration system); or,

- A pressing societal need (that is, a need to help people and society, such as ensuring all community members have access to clean water to stay healthy).

- It has deep integration across multiple disciplines. This is important because complex socio-scientific problems and phenomena cannot be explained or solved by looking at them through one perspective (e.g., environmental, social, economic, or ethical). Instead, experts from different disciplines must work together to blend their knowledge, theories, and expertise to come up with a comprehensive solution.

- Finally, it is transdisciplinary . That means no one discipline can solve the problem on its own.

From Disciplinary to Transdisciplinary

What do we mean by “transdisciplinary?” In its Federal STEM Strategic Plan, a collaboration of government agencies wrote in 2018 that science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education should move through a pathway where disciplines converge and where teaching and learning moves from disciplinary to transdisciplinary . They wrote:

“Problems that are relevant to people’s lives, communities, or society, as a whole, often cross disciplinary boundaries, making them inherently engaging and interesting. The transdisciplinary integration of STEM teaching and learning across STEM fields and with other fields such as the humanities and the arts enriches all fields and draws learners to authentic challenges from local to global in scale.” ( OSTP, 2018, p 20 )

STEAM education expert and author Joanne Vasquez, former Executive Director of the National Science Teaching Association (NSTA), and her co-authors explain it this way:

- Disciplinary – Students learn concepts and skills separately in isolation.

- Multidisciplinary – Students learn concepts and skills separately in each discipline but in reference to a common theme.

- Interdisciplinary – Students learn concepts and skills from two or more disciplines that are tightly linked so as to deepen knowledge and skills.

- Transdisciplinary – By undertaking real-world problems or explaining phenomena, students apply knowledge and skills from two or more disciplines to help shape the learning experience.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4f/b9/4fb93ac6-dbf3-4880-8190-84480d0dbeb5/picture2.png)

A Classroom Example

Let’s try an example, using images selected by one of the co-authors who is a master STEAM teacher and former Einstein Fellow at the U.S. Department of Energy, Kelly J. Day. Imagine you were teaching about plants so that your students can help people experiencing food insecurities in their community. This requires fundamental disciplinary knowledge about science, mathematics, social studies, civic engagement, and entrepreneurship. What would it look like to move along the pathway to convergence , from disciplinary to transdisciplinary teaching and learning?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/63/bd/63bd8e71-9b31-4bad-9e1b-683fb25da753/analogyconvergence.png)

- Using a disciplinary approach, a science teacher might ask students to examine the properties of soil or have students study how tomato seeds germinate in each soil type. In this case, the teacher is identifying an isolated concept (fact, idea, or practice) that is aligned with only one discipline (e.g., science).

- Using a multidisciplinary approach, a math teacher might ask the students who learned about soil properties and tomato seed germination in science class, to calculate in math class the cost of buying 1 pound of soil, 20 packets of tomato seeds, 10 packets of pepper seeds, and 3 garden tools. The concept now involves multiple disciplines addressed independently on different aspects of the same concept.

- Using an interdisciplinary approach, multiple teachers—for example, one social studies, one science, and one math—might work together to have students plant a variety of seeds in different soil types to grow vegetables on the school grounds. Each teacher would ask students to contribute to the collective problem—studying soil properties and seed germination in their science class; calculating the cost of the materials in their math class; and finally, drawing a map of the local school grounds in their social studies class to help decide where to place the garden based on geographic direction. In this case, students and teachers across disciplines work together in an integrated way that makes the concept more authentic and real-world (but, like the salad shown here, you can still identify the individual component disciplines or parts).

- Finally, using a transdisciplinary approach, you would walk into any one classroom and not be able to tell which discipline(s) are being taught because they have “converged.” For example, students might be asked to come up with an entrepreneurial project to raise funds for those in need in their local community. They decide to design and build a garden so they can make and sell salsa, while also helping people experiencing food insecurities in their community. In this case, students identify a complex real-world problem and work together to create a shared approach to identifying the phenomenon or solving the problem.

A Pathway to Convergence

Teaching for convergence is not about replacing disciplinary teaching with transdisciplinary teaching; instead, it is about a pathway to convergence . Students, especially in the early grades, still require a strong foundation of disciplinary knowledge and skills. The transition along the pathway to convergence , from disciplinary to transdisciplinary teaching and learning, does not just happen—it is intentional, explicit, and measured.

Transdisciplinary teaching and learning that leads students along a pathway to convergence has many different names that you may be familiar with already—phenomenon-based learning, problem-based learning, place-based learning, project-based learning, civic engagement, inquiry-based learning, entrepreneurship education, and applied learning. No matter what you call it, this type of teaching is important to prepare today’s students for tomorrow’s complex world. And it is becoming more common in schools, despite the barriers that exist in the U.S. (e.g., aligning with standards; finding time in the curriculum; finding common planning time to collaborate with other teachers).

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1f/12/1f12b463-848a-4fac-a6e3-65b2742c0932/global_goals.png)

Free Teaching Resources

The Smithsonian and other federal agencies that support STEAM teachers are here to help. We develop resources to support educators as they move from disciplinary to transdisciplinary teaching and learning along the pathway to convergence. At the Smithsonian, for example, we have a front door to discoveries in science, history, art, and culture. We bring these disciplines together by integrating inquiry-based science education, civic engagement, place-based education, global citizenship education, and education for sustainable development, so that students can engage in local action for global goals , whether it is about food security or environmental justice .

Convergence education and a transdisciplinary approach to teaching and learning helps students develop critical reasoning skills, systemic understanding of complex issues, scientific literacy, perspective taking, and consensus building, all as they plan and carry out local actions for social good. Teachers and students across the country, with the support of the Smithsonian and other federal partners, are tackling the most pressing environmental and social issues of our time, supporting young students as they take action to address complex global issues, and helping them find solutions that address societal needs through convergence education.

Acknowledgement : This article is based on the work of the Federal Coordination in STEM Education (FC-STEM) Interagency Working Group on Convergence, under the direction of Quincy Brown and Nafeesa Owens of the Office of Science and Technology Policy. The IWG is co-led by Louie Lopez and Jorge Valdes, with support from Executive Secretary Emily Kuehn.

Editor's Note: To learn more about the Convergence Education framework, join Carol O’Donnell and Kelly J. Day, along with a panel of federal educators and practitioners at the Smithsonian's National Education Summit on July 27-28, 2022. More information is available here: https://s.si.edu/EducationSummit2022

Carol O’Donnell | READ MORE

Dr. Carol O’Donnell is Director of the Smithsonian Science Education Center, dedicated to transforming K-12 Education through Science™ in collaboration with communities across the globe. Carol serves on numerous boards and committees dedicated to science education and is on the part-time faculty of the Physics Department at George Washington University, where she earned her doctorate. Carol began her career as a primary school teacher. Her TedX Talk demonstrates her passion for “doing science” and “object-driven learning.”

Kelly J. Day | READ MORE

Kelly Day is the Albert Einstein Distinguished Educator Fellow at the Department of Energy and is on the Interagency Working Group for Convergence Education. She also helps run the DOE-sponsored National Science Bowl. Prior to her placement at the DOE, Day was a mathematics teacher and in 2015 ,Day received the Fulbright Distinguished Award in Teaching.

Top 10 risks and opportunities for education in the face of COVID-19

Subscribe to the center for universal education bulletin, rebecca winthrop rebecca winthrop director - center for universal education , senior fellow - global economy and development @rebeccawinthrop.

April 10, 2020

March 2020 will forever be known in the education community as the month when almost all the world’s schools shut their doors. On March 1, six governments instituted nationwide school closures due to the deadly coronavirus pandemic, and by the end of the month, 185 countries had closed, affecting 90 percent of the world’s students. The speed of these closures and the rapid move to distance learning has allowed little time for planning or reflection on both the potential risks to safeguard against and the potential opportunities to leverage.

With every crisis comes deep challenges and opportunities for transformation— past education crises have shown that it is possible to build back better. To help me reflect on what some of these challenges and opportunities may be, I recently spoke to Jim Knight , current member of the House of Lords, head of education for Tes Global, and former U.K. schools minister; and to Vicki Phillips , current chief of education at the National Geographic Society and a former U.S. superintendent of schools and state secretary of education. They provide perspectives from inside and outside of government in the U.K. and U.S., though their insights can likely help the many countries worldwide struggling to continue education during the pandemic.

Risks and challenges

#1: Distance learning will reinforce teaching and learning approaches that we know do not work well.

Jim: Many countries are shifting to distance learning approaches, whether through distributing physical packets of materials for students or through using technology to facilitate online learning. And there are real risks because many of these approaches can be very solitary and didactic when you’re just asking students to sit and quietly watch videos, read documents online, or click through presentations—that’s really dull. The worst form of learning is to sit passively and listen, and this may be the form that most students will receive during school closures. It serves no one well, especially those who are the furthest behind.

#2: Educators will be overwhelmed and unsupported to do their jobs well.

Vicki: Teachers had little or no notice about their schools closing and shifting to online learning—this can be challenging for anybody. They’ve shared that they are overwhelmed with all sorts of materials and products, and we are seeing educators begin to push back and request help filtering through all the resources to find those that are quality.

At the same time, teachers are just like the rest of us in that they are experiencing this strange new world as mothers, fathers, aunts, uncles, and grandparents. They are trying to deal with their individual lives and take care of their kids and find new ways to make sure that learning continues.

#3: The protection and safety of children will be harder to safeguard.

Jim: In the U.K., we have stringent processes around checking who has access to children during school, in after-school clubs and sports. Schools have safeguard measures in place to ensure that predators toward children, such as pedophiles, can’t access young people. Now, once you move to online learning in a home environment, you can’t safeguard against this. People have to be mindful about the design of online learning so that bad individuals don’t get to children outside of their home.

#4: School closures will widen the equity gaps.

Vicki: Over the last decade or so, progress has been made in the number of students who have access to devices and connectivity, making this move to online learning possible. At the same time, not every child has access to digital devices or internet connectivity at home, and we need to ensure those kids get access to learning resources as well. This means that learning resources need to be available on every kind of device and it means, for kids who don’t have access, we still need to find a way to reach them.

#5: Poor experiences with ed-tech during the pandemic will make it harder to get buy-in later for good use of ed-tech.

Jim: We know that some students who use ed-tech during the pandemic will have a poor experience because they’re not used to it. Some people will say, “During the virus we tried the ed-tech-enabled learning approaches, it was terrible, and look at my test scores.” Yes, this will happen. People’s test scores will be impacted. People will become unhappy because the mental health effects of being isolated will be profound. We must be prepared for that. Those poor experiences are really important to learn what does and doesn’t work.

Opportunities to Leverage

#1: Blended learning approaches will be tried, tested, and increasingly used.

Jim: We know that the more engaging learning styles are ones that are more interactive, and that face-to-face learning is better than 100 percent online learning. We also know blended learning can draw on the best of both worlds and create a better learning experience than one hundred percent face-to-face learning. If, after having done 100 percent online at the end of this, I think it’s quite possible that we can then think about rebalancing the mix between face-to-face and online. Teachers will have started to innovate and experiment with these online tools and may want to continue online pedagogies as a result of all this. That’s really exciting.

#2: Teachers and schools will receive more respect, appreciation, and support for their important role in society.

Vicki: I think it will be easier to understand that schools aren’t just buildings where students go to learn, and that teachers are irreplaceable. There’s something magic about that in-person connection, that bond between teachers and their students. Having that face-to-face connection with learners and being able to support them across their unique skills—that’s very hard to replicate in a distance learning environment. Also, many students access critical resources at school, such as meals, clothing, and mental health support that may not be as widely available at home.

#3: Quality teaching and learning materials will be better curated and more widely used.

Vicki: Educators are looking to other educators as well as trusted sources to help curate high-quality online learning tools. At National Geographic, we’ve curated collections for K-12 learners in our resource library. We’ve created a new landing page that allows educators, parents, and caregivers to access our free materials quickly, and inspire young people. But it’s not just teachers struggling—it’s parents and other caregivers who are trying to bring learning to life. To that end, we’re livestreaming our Explorer Classroom model that connects young people with scientists, researchers, educators, and storytellers. During this transition, we want students and families to have access to that larger world, in addition to their own backyard.

#4: Teacher collaboration will grow and help improve learning.

Jim: As a profession, I hope we come out of this crisis stronger by collaborating and working together. I’m a firm believer in not asking heavily burdened teachers to reinvent the wheel. At my company Tes, we’ve got a big resource-sharing platform for teachers, including coronavirus-related resources. There are other platforms too, such as Teachers Pay Teachers and Khan Academy, where teachers can see what others have done. A teacher could say, “well, rather than record a video with the instructional element I need, I might be able to find someone who has done that really well already.” One of the most important things teachers can do now is draw on what others are doing: Form community online, share the burden, and make things a bit easier.

#5: This crisis will help us come together across boundaries.

Vicki: We would be remiss if we didn’t take away a greater sense of empathy for each other—the idea that we can work through anything together—from this crisis. I think it’s an opportunity for the education sector to unite, forge connections across countries and continents, and truly share what works in a global way. I don’t think, prior to this crisis, that we’ve been able to do this, and we will have missed a big opportunity if we don’t try to do that now.

Jim: We will get through this stronger. I live in a divided country, and from where I sit, it looks like the U.S. is a divided country too. When you go through a big national crisis like this, you come out stronger as a country because you’ve been fighting together, working together.

Related Content

Rebecca Winthrop

May 4, 2020

Urvashi Sahni

May 14, 2020

Emiliana Vegas, Rebecca Winthrop

November 17, 2020

Related Books

Rachael Katz, Helen Shwe Hadani

June 30, 2022

Tom Loveless

November 1, 2001

Diane Ravitch

January 1, 2000

Education Technology K-12 Education

Global Economy and Development

Center for Universal Education

Brad Olsen, John McIntosh

April 3, 2024

Darcy Hutchins, Emily Markovich Morris, Laura Nora, Carolina Campos, Adelaida Gómez Vergara, Nancy G. Gordon, Esmeralda Macana, Karen Robertson

March 28, 2024

Jennifer B. Ayscue, Kfir Mordechay, David Mickey-Pabello

March 26, 2024

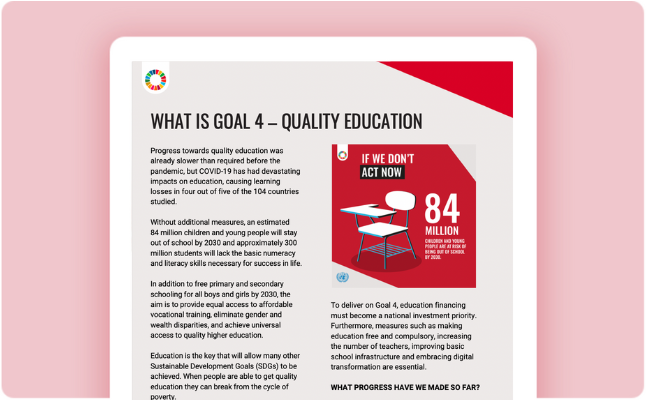

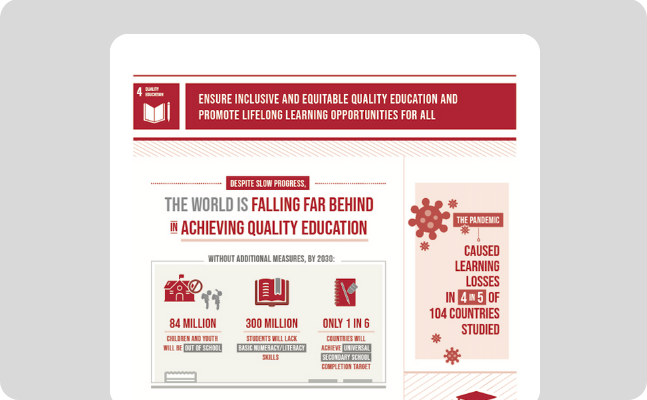

- Progress towards quality education was already slower than required before the pandemic, but COVID-19 has had devastating impacts on education, causing learning losses in four out of five of the 104 countries studied.

Without additional measures, an estimated 84 million children and young people will stay out of school by 2030 and approximately 300 million students will lack the basic numeracy and literacy skills necessary for success in life.

In addition to free primary and secondary schooling for all boys and girls by 2030, the aim is to provide equal access to affordable vocational training, eliminate gender and wealth disparities, and achieve universal access to quality higher education.

Education is the key that will allow many other Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to be achieved. When people are able to get quality education they can break from the cycle of poverty.

Education helps to reduce inequalities and to reach gender equality. It also empowers people everywhere to live more healthy and sustainable lives. Education is also crucial to fostering tolerance between people and contributes to more peaceful societies.

- To deliver on Goal 4, education financing must become a national investment priority. Furthermore, measures such as making education free and compulsory, increasing the number of teachers, improving basic school infrastructure and embracing digital transformation are essential.

What progress have we made so far?

While progress has been made towards the 2030 education targets set by the United Nations, continued efforts are required to address persistent challenges and ensure that quality education is accessible to all, leaving no one behind.

Between 2015 and 2021, there was an increase in worldwide primary school completion, lower secondary completion, and upper secondary completion. Nevertheless, the progress made during this period was notably slower compared to the 15 years prior.

What challenges remain?

According to national education targets, the percentage of students attaining basic reading skills by the end of primary school is projected to rise from 51 per cent in 2015 to 67 per cent by 2030. However, an estimated 300 million children and young people will still lack basic numeracy and literacy skills by 2030.

Economic constraints, coupled with issues of learning outcomes and dropout rates, persist in marginalized areas, underscoring the need for continued global commitment to ensuring inclusive and equitable education for all. Low levels of information and communications technology (ICT) skills are also a major barrier to achieving universal and meaningful connectivity.

Where are people struggling the most to have access to education?

Sub-Saharan Africa faces the biggest challenges in providing schools with basic resources. The situation is extreme at the primary and lower secondary levels, where less than one-half of schools in sub-Saharan Africa have access to drinking water, electricity, computers and the Internet.

Inequalities will also worsen unless the digital divide – the gap between under-connected and highly digitalized countries – is not addressed .

Are there groups that have more difficult access to education?

Yes, women and girls are one of these groups. About 40 per cent of countries have not achieved gender parity in primary education. These disadvantages in education also translate into lack of access to skills and limited opportunities in the labour market for young women.

What can we do?

Ask our governments to place education as a priority in both policy and practice. Lobby our governments to make firm commitments to provide free primary school education to all, including vulnerable or marginalized groups.

Facts and figures

Goal 4 targets.

- Without additional measures, only one in six countries will achieve the universal secondary school completion target by 2030, an estimated 84 million children and young people will still be out of school, and approximately 300 million students will lack the basic numeracy and literacy skills necessary for success in life.

- To achieve national Goal 4 benchmarks, which are reduced in ambition compared with the original Goal 4 targets, 79 low- and lower-middle- income countries still face an average annual financing gap of $97 billion.

Source: The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023

4.1 By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and Goal-4 effective learning outcomes

4.2 By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys have access to quality early childhood development, care and preprimary education so that they are ready for primary education

4.3 By 2030, ensure equal access for all women and men to affordable and quality technical, vocational and tertiary education, including university

4.4 By 2030, substantially increase the number of youth and adults who have relevant skills, including technical and vocational skills, for employment, decent jobs and entrepreneurship

4.5 By 2030, eliminate gender disparities in education and ensure equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for the vulnerable, including persons with disabilities, indigenous peoples and children in vulnerable situations

4.6 By 2030, ensure that all youth and a substantial proportion of adults, both men and women, achieve literacy and numeracy

4.7 By 2030, ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development

4.A Build and upgrade education facilities that are child, disability and gender sensitive and provide safe, nonviolent, inclusive and effective learning environments for all

4.B By 2020, substantially expand globally the number of scholarships available to developing countries, in particular least developed countries, small island developing States and African countries, for enrolment in higher education, including vocational training and information and communications technology, technical, engineering and scientific programmes, in developed countries and other developing countries

4.C By 2030, substantially increase the supply of qualified teachers, including through international cooperation for teacher training in developing countries, especially least developed countries and small island developing states

UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

UN Children’s Fund

UN Development Programme

Global Education First Initiative

UN Population Fund: Comprehensive sexuality education

UN Office of the Secretary General’s Envoy on Youth

Fast Facts: Quality Education

Infographic: Quality Education

Related news

‘Education is a human right,’ UN Summit Adviser says, urging action to tackle ‘crisis of access, learning and relevance’

Masayoshi Suga 2022-09-15T11:50:20-04:00 14 Sep 2022 |

14 September, NEW YORK – Education is a human right - those who are excluded must fight for their right, Leonardo Garnier, Costa Rica’s former education minister, emphasized, ahead of a major United Nations [...]

Showcasing nature-based solutions: Meet the UN prize winners

Masayoshi Suga 2022-08-13T22:16:45-04:00 11 Aug 2022 |

NEW YORK, 11 August – The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and partners have announced the winners of the 13th Equator Prize, recognizing ten indigenous peoples and local communities from nine countries. The winners, selected from a [...]

UN and partners roll out #LetMeLearn campaign ahead of Education Summit

Yinuo 2022-08-10T09:27:23-04:00 01 Aug 2022 |

New York, 1 August – Amid the education crisis exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, the United Nations is partnering with children's charity Theirworld to launch the #LetMeLearn campaign, urging world leaders to hear the [...]

Related videos

Malala yousafzai (un messenger of peace) on “financing the future: education 2030”.

VIDEO: Climate education at COP22

From the football field to the classrooms of Nepal | UNICEF

Share this story, choose your platform!

The 10 Education Issues Everybody Should Be Talking About

- Share article

What issues have the potential to define—or re define—education in the year ahead? Is there a next “big thing” that could shift the K-12 experience or conversation?

These were the questions Education Week set out to answer in this second annual “10 Big Ideas in Education” report.

You can read about last year’s ideas here . In 2019, though, things are different.

This year, we asked Education Week reporters to read the tea leaves and analyze what was happening in classrooms, school districts, and legislatures across the country. What insights could reporters offer practitioners for the year ahead?

Some of the ideas here are speculative. Some are warning shots, others more optimistic. But all 10 of them here have one thing in common: They share a sense of urgency.

Accompanied by compelling illustrations and outside perspectives from leading researchers, advocates, and practitioners, this year’s Big Ideas might make you uncomfortable, or seem improbable. The goal was to provoke and empower you as you consider them.

Let us know what you think, and what big ideas matter to your classroom, school, or district. Tweet your comments with #K12BigIdeas .

No. 1: Kids are right. School is boring.

Out-of-school learning is often more meaningful than anything that happens in a classroom, writes Kevin Bushweller, the Executive Editor of EdWeek Market Brief. His essay tackling the relevance gap is accompanied by a Q&A with advice on nurturing, rather than stifling students’ natural curiosity. Read more.

No. 2: Teachers have trust issues. And it’s no wonder why.

Many teachers may have lost faith in the system, says Andrew Ujifusa, but they haven’t lost hope. The Assistant Editor unpacks this year’s outbreak of teacher activism. And read an account from a disaffected educator on how he built a coalition of his own. Read more.

No. 3: Special education is broken.

Forty years since students with disabilities were legally guaranteed a public school education, many still don’t receive the education they deserve, writes Associate Editor Christina A. Samuels. Delve into her argument and hear from a disability civil rights pioneer on how to create an equitable path for students. Read more.

No. 4: Schools are embracing bilingualism, but only for some students.

Staff Writer Corey Mitchell explains the inclusion problem at the heart of bilingual education. His essay includes a perspective from a researcher on dismantling elite bilingualism. Read more.

No. 5: A world without annual testing may be closer than you think.

There’s agreement that we have a dysfunctional standardized-testing system in the United States, Associate Editor Stephen Sawchuk writes. But killing it would come with some serious tradeoffs. Sawchuk’s musing on the alternatives to annual tests is accompanied by an argument for more rigorous classroom assignments by a teacher-practice expert. Read more.

No. 6: There are lessons to be learned from the educational experiences of black students in military families.

Drawing on his personal experience growing up in an Air Force family, Staff Writer Daarel Burnette II highlights emerging research on military-connected students. Learn more about his findings and hear from two researchers on what a new ESSA mandate means for these students. Read more.

No. 7: School segregation is not an intractable American problem.

Racial and economic segregation remains deeply entrenched in American schools. Staff Writer Denisa R. Superville considers the six steps one district is taking to change that. Her analysis is accompanied by an essay from the president of the American Educational Research Association on what is perpetuating education inequality. Read more.

No. 8: Consent doesn’t just belong in sex ed. class. It needs to start a lot earlier.

Assistant Editor Sarah D. Sparks looked at the research on teaching consent and found schools and families do way too little, way too late. Her report is partnered with a researcher’s practical guide to developmentally appropriate consent education. Read more.

No. 9: Education has an innovation problem.

Are education leaders spending too much time chasing the latest tech trends to maintain what they have? Staff Writer Benjamin Herold explores the innovation trap. Two technologists offer three tips for putting maintenance front and center in school management. Read more.

No. 10: There are two powerful forces changing college admissions.

Some colleges are rewriting the admissions script for potential students. Senior Contributing Writer Catherine Gewertz surveys this changing college admissions landscape. Her insights are accompanied by one teacher’s advice for navigating underserved students through the college application process. Read more.

Wait, there’s more.

Want to know what educators really think about innovation? A new Education Week Research Center survey delves into what’s behind the common buzzword for teachers, principals, and district leaders. Take a look at the survey results.

A version of this article appeared in the January 09, 2019 edition of Education Week as What’s on the Horizon for 2019?

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs, sign up & sign in.

The 10 Biggest Challenges in Education (and How to Overcome Them)

We surveyed educators across the country to discover the 10 biggest challenges facing schools today.

- Featured Podcast

About this Issue

When the Obstacle Is the Way

Repairing the Leaky Bucket

Are We Teaching Care or Control?

The Someday/Monday Dilemma

Creating Clarity on Equity in Schools

4 C’s for Better Student Engagement

Reducing Teacher Workloads

To Address Learning Gaps, Go Deeper

Let’s Talk About Mental Health

A Matter of Respect

Protecting Students’ Freedom to Learn

Grading Writing Just Got Weird

Stop Coachsplaining!

Boosting Sight Reading

Finding Joy in Black Children’s Literacy Lives

And Now for Some Good News

Making an Impact Beyond the Classroom

EL Takeaways

Listen & learn, recent issues, february 2024, december 2023, november 2023, october 2023, to process a transaction with a purchase order please send to [email protected].

Education 2030: topics and issues

The debates included the following sessions:

Providing meaningful learning opportunities to out-of-school children

In this session a panel of experts explored the changes needed in countries which have large out-of-school children populations as well as examples from countries which are ‘in the final mile’. “They are all different, they don’t fit into one box” said Mary Joy Pigozzi, Director of Educate A Child (EAC). Ms Pigozzi emphasized the need for attention to children who are displaced, conflict affected, working children, and so on. Mr Albert Montivans, Head of Education Indicators and Data Analysis at UNESCO Institute for Statistics added: “one of the priorities is to better the disadvantaged”.

The session was also attended by the Minister of Education, Haiti, Nesmy Manigat, the CEO of Global Partnership for Education Alice Albright, and the Director-General in the Romanian Ministry of Education, Liliana Preoteasa. The panelists raised their voices on ‘inclusion’, ‘partnership’, ‘financing’, and ‘sustainable planning’ in order to pull youngsters into the schooling system. The session concluded with further food for thought from Mr Nesmy Manigat, the Minister of Education,Haiti: “Let’s also talk about the children who are in school, yet they do not learn. Teach them what the meaning of school is - what do we need to do in school and not only focus on the policies”.

Mobilizing Business to Realize the 2030 Education Agenda

Representatives from business and education organizations gathered at a parallel session on mobilizing business to realize the 2030 agenda. Chaired by Justin van Fleet, Chief of Staff for the UN Special Envoy for Global Education, the session established a business case to invest in education and focused on how business can coordinate action with other stakeholders. The lively discussion saw questions from the floor around ICT’s, but also issues of trust; with a representative from the Philippines asking the panel whether business cares about education or is simply benefiting from it. The President of Lego Education, Mr Jacob Kragh, said there was a sincere objective from the company “to pursue the benefit of the children and make sure they get the chance to be the best they can in life”. He said that "taking over education was by no means the objective of the private sector", and reiterated the importance of working closely with governments and the public sector. Panelists also included Vikas Pota from GEMS Education, Martina Roth from Intel Corporation and Jouko Sarvi from the Asian Development Bank.

In parallel, Argentina’s Minister of Education, Alberto Sileoni, was joined by UNESCO Director, David Atchoarena, and UN Special Advisor on Post-2015 Development Planning, Amina Mohammed, at a session on Global and regional coordination and monitoring mechanisms. The session dealt with the importance of having robust mechanisms for coordination and monitoring. Session participants looked at how global and regional mechanisms for education should work alongside the new mechanisms for the overall Sustainable Development Goal, with Mr Atchoarena pointing out that the focus on ‘country-level’ monitoring and review was much stronger in the new education agenda.

Effective Governance and Accountability

In this group session, the panelists suggested the right direction for contemporary national education governance. Namely the key policies and strategies to construct a pragmatic governance framework that is both regulatory and collaborative were suggested throughout the discussion.

The chair, Mr. Gwang-Jo Kim, Director of UNESCO’s regional office in Bangkok, Thailand, posed three questions before the discussion: How can we define the term “effective governance”. What would be the role of the private sector and how to balance between autonomy resulting from decentralization, and accountability. The panels and the participants engaged in a lively debate: “Governance should focus on dialogue between communities in society so that private sector can become stakeholders to invest in education,” stated the Minister of Education, Bolivia, Roberto Aguilar, as an answer to the second question. He also gave an example from his country where education campaigns are usually funded by private institutions, saying it is social responsibility for private entities to participate actively in the effective governance framework.

The Minster of Education, Democratic Republic of Congo,Maker Mwangu Famba, said the core elements of effective governance were transparency and responsibility.

How does education contribute to sustainable development post 2015?

Sustainable development is not just about technological solutions, political regulation or financial instruments alone. The realization of the transformative power of education and the importance of cross-sectoral approaches need to be taken into account. This was the message given by Ms Amina Mohammed, Special Advisor to the UN Secretary-General on Post 2015 Development Planning, as she said that education was not simply about learning, it is about empowerment and key in the sustainable development agenda. In this session, the panel members discussed how education can address global challenges, in particular how education contributes to addressing climate change and health issues and poverty reduction.

Education is one of the most powerful tools for people to be informed about diseases, take preventative measures, recognize signs of illness early and be informed to use health care services, the speakers highlighted. Mr Mark Brown, the Minister of Finance in Cook Islands, said that current knowledge as well as new knowledge should reach not only school children but also adults, as they are the educators.

The growing interaction between education and climate change cannot be neglected, Ms Kandia Camara, Minister of National Education, Cote d’lvoire, said: “There are school programs to teach healthy lifestyles and the importance of forests,” actions are being taken to ensure climate-safe and climate-friendly school environments.

Furthermore, Mr Renato Janine Ribeiro, Minister of Education in Brazil, expressed the difficulty of eradicating poverty, “the challenge we face is ‘hunger, they live in places that are very difficult to access”, he said. Hence, geographic placement poses as a barrier to accessibility. Yet, in order to mitigate the problem with a collective effort, he asserted that Brazil would be happy to share its valuable experience on education for sustainable development with any country in order to bolster efforts.

Towards the end of the session, the CEO of the Campaign for Popular Education, Bangladesh, Ms Rasheda Choudhury, firmly stated: “The two nonnegotiable principles are: first, education is a fundamental human right and second, it is the state’s responsibility to provide education to their every single citizen”.

Other recent news

- High contrast

- Press Centre

Search UNICEF

- Inclusive education

Every child has the right to quality education and learning.

There are an estimated 240 million children with disabilities worldwide. Like all children, children with disabilities have ambitions and dreams for their futures. Like all children, they need quality education to develop their skills and realize their full potential.

Yet, children with disabilities are often overlooked in policymaking, limiting their access to education and their ability to participate in social, economic and political life. Worldwide, these children are among the most likely to be out of school. They face persistent barriers to education stemming from discrimination, stigma and the routine failure of decision makers to incorporate disability in school services.

Disability is one of the most serious barriers to education across the globe.

Robbed of their right to learn, children with disabilities are often denied the chance to take part in their communities, the workforce and the decisions that most affect them.

Getting all children in school and learning

Inclusive education is the most effective way to give all children a fair chance to go to school, learn and develop the skills they need to thrive.

Inclusive education means all children in the same classrooms, in the same schools. It means real learning opportunities for groups who have traditionally been excluded – not only children with disabilities, but speakers of minority languages too.

Inclusive systems value the unique contributions students of all backgrounds bring to the classroom and allow diverse groups to grow side by side, to the benefit of all.

Inclusive education allows students of all backgrounds to learn and grow side by side, to the benefit of all.

But progress comes slowly. Inclusive systems require changes at all levels of society.

At the school level, teachers must be trained, buildings must be refurbished and students must receive accessible learning materials. At the community level, stigma and discrimination must be tackled and individuals need to be educated on the benefit of inclusive education. At the national level, Governments must align laws and policies with the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities , and regularly collect and analyse data to ensure children are reached with effective services.

UNICEF’s work to promote inclusive education

To close the education gap for children with disabilities, UNICEF supports government efforts to foster and monitor inclusive education systems. Our work focuses on four key areas:

- Advocacy : UNICEF promotes inclusive education in discussions, high-level events and other forms of outreach geared towards policymakers and the general public.

- Awareness-raising : UNICEF shines a spotlight on the needs of children with disabilities by conducting research and hosting roundtables, workshops and other events for government partners.

- Capacity-building : UNICEF builds the capacity of education systems in partner countries by training teachers, administrators and communities, and providing technical assistance to Governments.

- Implementation support : UNICEF assists with monitoring and evaluation in partner countries to close the implementation gap between policy and practice.

More from UNICEF

The boy who changed his community in Serbia

How one boy overcame stigma and demonstrated the power of inclusive education.

I want to change how society sees people with disabilities

"When I came to school, I was determined to show everybody I could make it."

Climate action for a climate-smart world

UNICEF and partners are monitoring, innovating and collaborating to tackle the climate crisis

Two-thirds of refugee children in Armenia enrolled in school, efforts must now focus on expanding access to education for all children

Fixing the Broken Promise of Education for All

This report draws on national studies to examine why millions of children continue to be denied the fundamental right to primary education.

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities adopts a broad categorization of persons with disabilities and reaffirms that all persons with all types of disabilities must enjoy all human rights and fundamental freedoms.

Inclusive Education: Including Children with Disabilities in Quality Learning

This document provides guidance on what Governments can do to create inclusive education systems.

Towards Inclusive Education: The Impact of Disability on School Attendance in Developing Countries

Using cross-nationally comparable and nationally representative data from 18 surveys in 15 countries, this paper investigates how disability affects school attendance.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

How does technology challenge teacher education?

Lina kaminskienė.

1 Education Academy, Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, Lithuania

Sanna Järvelä

2 Faculty of Education and Psychology, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland

Erno Lehtinen

3 Department of Teacher Education, University of Turku, Turku, Finland

Associated Data

The paper is based on openly available data.

The paper presents an overview of challenges and demands related to teachers’ digital skills and technology integration into educational content and processes. The paper raises a debate how technologies have created new skills gaps in pre-service and in-service teacher training and how that affected traditional forms of teacher education. Accordingly, it is discussed what interventions might be applicable to different contexts to address these challenges. It is argued that technologies should be viewed both as the field where new competences should be developed and at the same time as the method used in developing learning environments for teacher students.

Introduction

In the last few decades, national authorities and multinational organisations have emphasised the importance of increasing the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) in schools and universities (Flecknoe, 2002 ; Roztocki et al., 2019 ; UNESCO ICT Competency Framework for Teachers, 2018 ). This poses a double challenge for teacher education: determining how new technologies can be used to improve the quality of learning experiences that student teachers receive during their university studies and identifying what kinds of new skills future teachers will need for teaching in technologically rich school environments. Several of the arguments in favour of greater use of ICT in schools are based on the belief that due to the general digitisation of the workforce, it is vital that students acquire good digital skills at an early age. However, it has also been argued that the use of ICT will be engaging for students and can thus result in better learning outcomes (Cheung & Slavin, 2013 ; Gloria, 2015 ). A number of large meta-analyses have shown that intervention studies utilising technology have positive effects on students’ motivation and learning (Fadda et al., 2022 ; Wouters et al., 2013 ).

However, when large-scale national and international evaluation studies have examined the relationship between the use of ICT and student achievement, the results have been mixed. Researchers have reported that re-analyses of large international evaluation studies, including the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMMS) and Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), indicate that there is either no relationship or a negative relationship between the frequency of ICT use in teaching and students’ achievements (Eickelmann et al., 2016 ; Papanastasiou et al., 2003 ).

The mixed results regarding the impact of ICT suggest that there are qualitative differences between the ways in which technology is implemented. In intervention studies, ICT applications have typically been used with careful planning, with extensive professional development for teachers conducting the experiment and with continuous support from researchers, whereas large-scale evaluation studies have focused on regular classrooms without such support. When technology is implemented in these latter situations, the pedagogical quality of the technology application is determined by the teachers’ knowledge and skills. However, there is a great deal of variation in the knowledge and competences of teachers when it comes to using technology in their classrooms (Valtonen et al., 2016 ). This highlights the importance of the in-service training of teachers while at the same time calling attention to pre-service teachers’ opportunities to acquire the competencies necessary to implement technology in their classrooms.

What does the development of technology mean for teacher education and how does it challenge traditional forms and content of the discipline? During the past few decades, a large number of policy documents and scientific studies have addressed this issue (Bakir, 2015 ). Different perspectives can be taken into account when discussing the influence of technology on teacher education. Several studies have examined the skills that will be necessary to apply technology to pedagogical practice in the future. This topic has been explored from several perspectives, such as teacher students’ technology literacy or their knowledge of technological pedagogical content (Mishra & Koehler, 2006 ). To ensure that future teachers possess adequate technical skills, standards and recommendations have been developed regarding the content of teacher education programmes. Rather than simply focusing on basic technological skills, the main emphasis has been on the knowledge and skills associated with the pedagogical use of technology (Erstad et al., 2021 ). Moreover, technology can provide many opportunities to develop novel methods to improve the quality of teacher education, such as the development of new methods for conducting research in the field of teacher education. In this special issue, these issues are addressed from a variety of theoretical and methodological perspectives.

Technology integration and content in teacher education

Given the many ways in which technology can be used in education, pre-service teachers’ pedagogical and technical competences in using ICT in teaching have different dimensions. For instance, Tondeur et al. ( 2017 ) developed a test to measure pre-service teachers’ ICT abilities and applied it to a large sample of Belgian teacher candidates. According to the findings, there are two dimensions to ICT competences: (1) competencies for supporting students’ use of ICT in class and (2) competencies for using ICT to create instructional materials. Some studies have also reported barriers that hinder the organisation of adequate teacher education to develop these skills, such as faculty beliefs and skills (Bakir, 2015 ; Polly et al., 2010 ).

The experiences pre-service teachers acquire during their teacher studies have also been shown to influence how willing and skilled they are when it comes to integrating technology in their classrooms (Agyei & Voogt, 2011 ). Additionally, studies have shown that the opportunity for teacher students to observe advanced technology applications in real-world settings is important for their future professional development (Gromseth et al., 2010 ). Hence, it is not sufficient to take formal courses in ICT or educational technology without applying these skills in the classroom.

Finnish pre-service teacher education stresses not only ICT skills but also teachers’ competences, such as strategic learning skills and collaboration competences. Häkkinen et al. ( 2017 ) identified five profiles among Finnish first-year pre-service teachers (N = 872) using perceptions of the teachers’ strategic learning skills and collaboration dispositions and investigated what background variables explained membership to those profiles. The most robust factor explaining membership in the profiles was life satisfaction. For example, pre-service teachers in a profile group with high strategic learning skills and high collaboration dispositions showed the highest anticipated life satisfaction after 5 years. Their results demonstrate the need to develop both ICT skills and learning competences in pre-service teacher education.

Use of technological innovations in organising teacher education

An analysis of the nature of experience and how practise can optimally enhance expertise has demonstrated the importance of deliberate practise (Ericsson et al., 1993 ), defined as an intensive practise that is purposefully focused on developing specific aspects of performance. To achieve this, it is necessary to have the opportunity to practise the most demanding aspects of performance with a large number of repetitions. Feedback from a tutor or coach also plays an important role in deliberate practise (Ericsson, 1993 ). Although deliberate practise has already been applied in some teacher education studies (e.g. Bronkhorst, 2011 ), its main aspect, repeated practise of challenging tasks and informed feedback, has been difficult to apply in traditional teacher education settings. Recent studies have shown that technology can contribute to the development of training methods that better reflect the main principles of deliberate practise.

There is a long tradition of using video technology in teacher education; such technology was first applied in a systematic manner in the 1970s (Nagro & Cornelius, 2013 ). Since then, a number of video-assisted instructional designs have been developed to provide teacher students with opportunities to learn from expert teachers, reflect on their own teaching behaviour and practise professional skills that would not otherwise be possible without this technology. Digital videos that are easy to use and various web platforms that facilitate the sharing and annotation of videos have opened up new opportunities for the development of novel learning environments in the field of teacher education (e.g. Sommerhoff et al., 2022 ). In the past few years, models for using videos recorded by mobile eye-tracking technology in teacher education have also been developed (e.g. Pouta et al., 2021 ).

Simulations are widely used in medical education, and a meta-analysis found that deliberate practise with simulations is superior to traditional clinical training in medical education (McGaghie et al., 2011 ). The use of simulations in teacher education is also gradually increasing. In their review of the use of simulations in teacher education, Theelen et al. ( 2019 ) synthesised the findings of 15 studies that applied computer-based simulations in teacher education. Several studies have demonstrated (Ferdig & Pytash, 2020 ; Samuelsson et al., 2022 ) that classroom simulations increase students’ self-efficacy and confidence in their teaching abilities. Classroom simulations were also found to have a positive impact on the development of classroom management skills.

New technologies can also be used in research on teaching and learning. Digitalisation has provided more ways to collect data and understand the teaching–learning process with multiple data channels and modalities. Multiple layers of data can be collected from contextual interactions, such as high-quality video data, psychophysiological measures and computer logs. With learning analytics, for example, these data can be used to create teacher dashboards, thus fulfilling students’ need for teacher scaffolds (Knoop-van Campen & Molenaar, 2020 ). Recently, eye-tracking technology has also been used to analyse teachers’ and student teachers’ abilities to notice relevant events in classrooms (Gegenfurtner et al., 2020 ; Pouta et al., 2021 ). Eye-movement technology, which has been used to model expert performance in other professional fields (Gegenfurtner et al., 2017 ), could also lead to promising training methods for teacher education.

Articles in this special issue

Three of the articles (Basilotta‑Gómez‑Pablos et al., 2022 ; Peciuliauskiene et al.’s, 2022 ; Kulaksız & Toran, 2022 ) included in this special issue deal with digital competences and interventions aimed at enhancing them.

Basilotta‑Gómez‑Pablos et al. (in this issue) synthesised 56 studies on higher education teachers’ digital competences. The authors used special software called SciMAT to analyse the content of the articles and to present thematic networks. Their review of the literature revealed that the topic is timely and that the number of relevant studies is increasing rapidly. The reviewed studies generally relied on teachers’ self-reports and self-evaluations of their abilities. Overall, the results indicated that the participants were aware of their insufficient knowledge and skills in the area of digital technology. According to the synthesis, many of the articles describe teachers’ experiences of various projects and activities aimed at improving their digital competences; however, many of these articles describe informal learning using internet tools and social networks. The authors conclude that their review clearly shows the gap in the evaluation of teachers’ competence in teaching and learning practice. Their recommendation is that more interventions and training programmes be created to support the development of teachers’ digital competence.

- The recent challenges in education caused by the pandemic situation raised teachers’ awareness on the gap of their digital skills.

- Despite the developed national or EU digital competences frameworks the trend remains that the development of digital skills is not systemic and lacks coherence in in-service and pre-service teacher education.

- Further studies may bring more insights regarding more effective interventions to teaching practices with a wider application of digital technologies.

Peciuliauskiene et al.’s ( 2022 ) paper presents the results of their survey of two Lithuanian universities that offer teacher education programmes. Their questionnaire focused on information literacy (search and evaluation) and ICT self-efficacy. According to their results, both information literacy variables predicted teacher students’ ICT self-efficacy. Additionally, there was an indirect relationship between information evaluation and ICT self-efficacy. The findings of the study are discussed in terms of their theoretical and practical implications. The research indicates that information search ability does not depend on a person’s digital nativity, contrary to what is sometimes assumed when referring to the younger generation of pre-service teachers. As an ICT literacy component, information evaluation has become particularly pertinent during the COVID-19 situation and recent challenges related to distinguishing credible information from the vast amount of fake news and propaganda. It is also noted that optimal time and resources should be planned for the development of information search and evaluation abilities; however, more time should be allocated for the development of information search literacy, as it directly predicts pre-service teachers’ ICT self-efficacy. Based on the findings of this study, we identify the following trends and implications for further studies: