The most comprehensive and authoritative history site on the Internet.

The History of Gun Control and the Second Amendment

The U.S. Supreme Court decision on June 23, 2022, invalidated a 1905 New York law that makes it unlawful to own a gun without a state license. It’s the latest and most unequivocal evidence of how the justices’ view of the Second Amendment has taken a dramatic turn in the 21st century. In New York State Rifle and Pistol Assn. v. Bruen, the court found in a 6-3 ruling that the New York requirement violated a citizens’ rights to bear arms.

In the majority opinion, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote that “individual self-defense is the central component of the Second Amendment right.”

That majority decision stands as a sharp contrast to the high court’s view of the Second Amendment in the first 200 years of its history. The strong dissents from the Court’s three most liberal Justices underscore how what were once unanimous decisions on gun rights have turned into rancorous debates in a sharply divided Court.

WHAT DOES THE SECOND AMENDMENT SAY?

The Second Amendment was added to the Constitution as part of the Bill of Rights in December 1791. It reads: “A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

That was not a controversial provision, merely codifying a widely held view on the legitimacy of a citizen militia and repeating a guarantee included in the British Bill of Rights of 1689 and the earlier U.S. Articles of Confederation.

What gun controls were and were not allowed was so uncontroversial that it was 1939 before the first case in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on whether the Second Amendment applied to a specific law curbing gun ownership. In fact, the Supreme Court had been in business for 85 years before it got its first case involving the Second Amendment at all. And then it was only a peripheral issue.

THE SUPREME COURT’S FIRST GUN CONTROL CASE

1875’s United States v. Cruikshank had its origins in disputes over the outcome of the 1872 gubernatorial election in Louisiana — disputes that led to such violence that more than 100 Blacks were killed. The federal government charged some of the white vigilantes with violating an 1870 statute making it unlawful to conspire to deprive anyone of their constitutional rights. Part of the charges were that the defendants had taken away the arms with which the Blacks were defending themselves.

The justices unanimously freed the vigilantes, saying that the constitutional curbs on seizing guns do not apply to actions of individuals. The Second Amendment, they said, doesn’t give anyone the right to own firearms, it merely prohibits governmental action to take away their guns.

But the opinion by Chief Justice Morrison Waite went much further. The Second Amendment, he wrote “means no more than it shall not be infringed by Congress. This is one of the amendments that has no other effect than to restrict the powers of the national government.”

In other words, he said, the Bill of Rights creates no barriers to firearms regulation by state or local government.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

THE SUPREME COURT SAYS AGAIN IT’S UP TO STATES

The Supreme Court — again unanimously — reaffirmed that position 11 years later. The case had to do with the validity of a $10 fine.

It was imposed on Herman Presser, a member of a group of Chicago workers of German background organized to counter the armed private guard squads formed by local employers. He headed some 400 of the members as they marched through Chicago streets carrying rifles.

That violated a state statute against any private militia not licensed by the governor. Presser insisted that prosecuting him infringed on his Second Amendments right to bear arms, but the justices were having none of it. Reiterating the Cruikshankstance, in Presser v. Illinois Justice William B. Woods wrote unequivocally: “[T]he amendment is a limitation only upon the power of Congress and the national government, and not upon that of the state.”

STATES PASS MORE GUN CONTROL LAWS

From the beginning of the republic, states had placed some limits on gun owners, such as forbidding carrying them in crowded places. But with the Supreme Court assurance that such statutes were valid, in the last decades of the 19th century, the popularity of such laws in state legislatures really took off.

Twenty-eight states had some curbs on where guns could be carried, and 15 barred minors from owning guns. In 1875, Wyoming actually banned all personally owned firearms from “any city, town or village.”

None of these state statutes were challenged at the Supreme Court.

GANGLAND VIOLENCE AND FEDERAL GUN CONTROL

It was 53 years before the Supreme Court again ruled on a Second Amendment case. United States v. Millerwas the first time the Justices looked directly at a Second Amendment challenge to a gun control law; without dissent they continued to emphasize that the amendment leaves lots of leeway for government regulation.

Under scrutiny was the very first significant federal curb on gun ownership. The 1934 National Firearms Act, passed in reaction to bloody criminal gang shootouts , imposed no bans; it did demand that various guns (those mostly used by criminals) be registered for a $200 fee. Two men arrested for bringing an unregistered sawed-off shotgun from Oklahoma into Arkansas argued that the law was an invalid incursion on their right to bear arms.

But the decision found that right was a very narrow one. The opinion by Justice James C. McReynolds interpreted the amendment as applying only to a defensive militia, and found that a sawed-off shotgun does not have “some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia.”

MODERN GUN CONTROL: THE SUPREME COURT REVERSES COURSE

It was not until 1995 that there was a hint that new personnel on the court might be bringing with them a different reading of the Second Amendment. It came in United States v. Lopez, a challenge to the conviction of Alfonso Lopez Jr. for bringing a concealed handgun and bullets to his high school in San Antonio, Texas — a violation of a 1990 federal law banning possession of any firearm “at a place that the individual knows, or has reasonable cause to believe, is a school zone.”

The high court threw out the conviction and held the law invalid as reaching beyond the powers the powers Congress claimed it had to regulate commerce. The Second Amendment was not at issue at all.

But Lopezis a significant part of gun rights history because it was the very first time the Supreme Court struck down a firearms control law. And the justices’ 5-4 vote showed that the unanimity that had characterized the previous gun control decisions had been shattered.

HITTING THE RESET BUTTON ON THE SECOND AMENDMENT

In 2008, those hints that the Supreme Court was moving away from its narrow reading of the constitutional limits on gun control became unequivocal reality. With another 5-4 decision, the justices tremendously broadened the Second Amendment prohibitions and threw into doubt more than a century of precedents.

That case, Washington, D.C. v. Heller, invalidated a broad gun control law in the District of Columbia that barred possession of handguns and required that other firearms be registered and kept unassembled, even in the owner’s home. Robert A. Levy, a lawyer who sensed that the Supreme Court was ready to changes its views of gun control laws, had rounded up a diverse group of six local residents to challenge the law.

At the high court, a five-justice majority agreed with Levy’s clients. The opinion written by Justice Antonin Scalia specifically rejected the interpretation that the Second Amendment was exclusively about owning firearms that could be used by a militia, calling that language only a “prefatory clause.” In fact, he wrote, “the Second Amendment right is exercised individually and belongs to all Americans” whether or not they have an intention of participating in a militia.

In other words, as a general rule, neither the federal nor state or local government can put curbs on individual gun ownership.

“The court in Heller almost hits the reset button on the Second Amendment,” Duke University law professor Joseph Blocher, co-director of the university’s Center for Firearms Law, said.

Scalia did go to pains to make clear that that rule was not absolute — that some gun controls were valid, albeit only narrow ones.

“Nothing in our opinion should be taken to cast doubt on the longstanding prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, or laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings,” he wrote.

THE POST-HELLER GUN-CONTROL LANDSCAPE

Heller is the standard by which all gun control measures are now judged. In two cases that it took up before the current one assessing the New York gun carry law, the Supreme Court made that clear. Because the District of Columbia is a federal enclave, some argued that Heller did not apply to the state and local laws. But in 2010, again in a 5-4 decision, the court held that the same standard applies to all jurisdictions, thereby invalidating a Chicago policy that for 50 years had effectively banned the acquisition of handguns. And in 2016, in a case the justices thought was so clear-cut that they didn’t need to hear oral arguments, the high court invalidated a Massachusetts ban on stun guns, even thought it had been upheld by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, that state’s highest court.

*Story updated on June 23, 2022.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.

Related stories

Portfolio: Images of War as Landscape

Whether they produced battlefield images of the dead or daguerreotype portraits of common soldiers, […]

Jerrie Mock: Record-Breaking American Female Pilot

In 1964 an Ohio woman took up the challenge that had led to Amelia Earhart’s disappearance.

Western Writers of America Announces Its 2024 Wister Award Winner

Historian Quintard Taylor has devoted his career to retracing the black experience out West.

How Saladin Became A Successful War Leader

How Saladin, Egypt’s first Sultan, unified his allies and won the admiration of his foes.

- Share full article

Gun Control, Explained

A quick guide to the debate over gun legislation in the United States.

By The New York Times

As the number of mass shootings in America continues to rise , gun control — a term used to describe a wide range of restrictions and measures aimed at controlling the use of firearms — remains at the center of heated discussions among proponents and opponents of stricter gun laws.

To help understand the debate and its political and social implications, we addressed some key questions on the subject.

Is gun control effective?

Throughout the world, mass shootings have frequently been met with a common response: Officials impose new restrictions on gun ownership. Mass shootings become rarer. Homicides and suicides tend to decrease, too.

After a British gunman killed 16 people in 1987, the country banned semiautomatic weapons like the ones he had used. It did the same with most handguns after a school shooting in 1996. It now has one of the lowest gun-related death rates in the developed world.

In Australia, a 1996 massacre prompted mandatory gun buybacks in which, by some estimates , as many as one million firearms were then melted into slag. The rate of mass shootings plummeted .

Only the United States, whose rate and severity of mass shootings is without parallel outside conflict zones, has so consistently refused to respond to those events with tightened gun laws .

Several theories to explain the number of shootings in the United States — like its unusually violent societal, class and racial divides, or its shortcomings in providing mental health care — have been debunked by research. But one variable remains: the astronomical number of guns in the country.

America’s gun homicide rate was 33 per one million people in 2009, far exceeding the average among developed countries. In Canada and Britain, it was 5 per million and 0.7 per million, respectively, which also corresponds with differences in gun ownership. Americans sometimes see this as an expression of its deeper problems with crime, a notion ingrained, in part, by a series of films portraying urban gang violence in the early 1990s. But the United States is not actually more prone to crime than other developed countries, according to a landmark 1999 study by Franklin E. Zimring and Gordon Hawkins of the University of California, Berkeley. Rather, they found, in data that has since been repeatedly confirmed , that American crime is simply more lethal. A New Yorker is just as likely to be robbed as a Londoner, for instance, but the New Yorker is 54 times more likely to be killed in the process. They concluded that the discrepancy, like so many other anomalies of American violence, came down to guns. More gun ownership corresponds with more gun murders across virtually every axis: among developed countries , among American states , among American towns and cities and when controlling for crime rates. And gun control legislation tends to reduce gun murders, according to a recent analysis of 130 studies from 10 countries. This suggests that the guns themselves cause the violence. — Max Fisher and Josh Keller, Why Does the U.S. Have So Many Mass Shootings? Research Is Clear: Guns.

Every mass shooting is, in some sense, a fringe event, driven by one-off factors like the ideology or personal circumstances of the assailant. The risk is impossible to fully erase.

Still, the record is confirmed by reams of studies that have analyzed the effects of policies like Britain’s and Australia’s: When countries tighten gun control laws, it leads to fewer guns in private citizens’ hands, which leads to less gun violence.

What gun control measures exist at the federal level?

Much of current federal gun control legislation is a baseline, governing who can buy, sell and use certain classes of firearms, with states left free to enact additional restrictions.

Dealers must be licensed, and run background checks to ensure their buyers are not “prohibited persons,” including felons or people with a history of domestic violence — though private sellers at gun shows or online marketplaces are not required to run background checks. Federal law also highly restricts the sale of certain firearms, such as fully automatic rifles.

The most recent federal legislation , a bipartisan effort passed last year after a gunman killed 19 children and two teachers at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, expanded background checks for buyers under 21 and closed what is known as the boyfriend loophole. It also strengthened existing bans on gun trafficking and straw purchasing.

— Aishvarya Kavi

Advertisement

What are gun buyback programs and do they work?

Gun buyback programs are short-term initiatives that provide incentives, such as money or gift cards, to convince people to surrender firearms to law enforcement, typically with no questions asked. These events are often held by governments or private groups at police stations, houses of worship and community centers. Guns that are collected are either destroyed or stored.

Most programs strive to take guns off the streets, provide a safe place for firearm disposal and stir cultural changes in a community, according to Gun by Gun , a nonprofit dedicated to preventing gun violence.

The first formal gun buyback program was held in Baltimore in 1974 after three police officers were shot and killed, according to the authors of the book “Why We Are Losing the War on Gun Violence in the United States.” The initiative collected more than 13,000 firearms, but failed to reduce gun violence in the city. Hundreds of other buyback programs have since unfolded across the United States.

In 1999, President Bill Clinton announced the nation’s first federal gun buyback program . The $15 million program provided grants of up to $500,000 to police departments to buy and destroy firearms. Two years later, the Senate defeated efforts to extend financing for the program after the Bush administration called for it to end.

Despite the popularity of gun buyback programs among certain anti-violence and anti-gun advocates, there is little data to suggest that they work. A study by the National Bureau of Economic Research , a private nonprofit, found that buyback programs adopted in U.S. cities were ineffective in deterring gun crime, firearm-related homicides or firearm-related suicides. . Evidence showed that cities set the sale price of a firearm too low to considerably reduce the supply of weapons; most who participated in such initiatives came from low-crime areas and firearms that were typically collected were either older or not in good working order.

Dr. Brendan Campbell, a pediatric surgeon at Connecticut Children’s Medical Center and an author of one chapter in “Why We Are Losing the War on Gun Violence in the United States,” said that buyback programs should collect significantly more firearms than they currently do in order to be more effective.

Dr. Campbell said they should also offer higher prices for handguns and assault rifles. “Those are the ones that are most likely to be used in crime,” and by people attempting suicide, he said. “If you just give $100 for whatever gun, that’s when you’ll end up with all these old, rusted guns that are a low risk of causing harm in the community.”

Mandatory buyback programs have been enacted elsewhere around the world. After a mass shooting in 1996, Australia put in place a nationwide buyback program , collecting somewhere between one in five and one in three privately held guns. The initiative mostly targeted semiautomatic rifles and many shotguns that, under new laws, were no longer permitted. New Zealand banned military-style semiautomatic weapons, assault rifles and some gun parts and began its own large-scale buyback program in 2019, after a terrorist attack on mosques in Christchurch. The authorities said that more than 56,000 prohibited firearms had been collected from about 32,000 people through the initiative.

Where does the U.S. public stand on the issue?

Expanded background checks for guns purchased routinely receive more than 80 or 90 percent support in polling.

Nationally, a majority of Americans have supported stricter gun laws for decades. A Gallup poll conducted in June found that 55 percent of participants were in favor of a ban on the manufacture, possession and sale of semiautomatic guns. A majority of respondents also supported other measures, including raising the legal age at which people can purchase certain firearms, and enacting a 30-day waiting period for gun sales.

But the jumps in demand for gun control that occur after mass shootings also tend to revert to the partisan mean as time passes. Gallup poll data shows that the percentage of participants who supported stricter gun laws receded to 57 percent in October from 66 percent in June, which was just weeks after mass shootings in Uvalde, Texas, and Buffalo. A PDK poll conducted after the shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde found that 72 percent of Republicans supported arming teachers, in contrast with 24 percent of Democrats.

What do opponents of gun control argue?

Opponents of gun control, including most Republican members of Congress, argue that proposals to limit access to firearms infringe on the right of citizens to bear arms enshrined in the Second Amendment to the Constitution. And they contend that mass shootings are not the result of easily accessible guns, but of criminals and mentally ill people bent on waging violence.

— Annie Karni

Why is it so hard to push for legislation?

Polling suggests that Americans broadly support gun control measures, yet legislation is often stymied in Washington, and Republicans rarely seem to pay a political price for their opposition.

The calculation behind Republicans’ steadfast stonewalling of any new gun regulations — even in the face of the kind unthinkable massacres like in Uvalde, Texas — is a fairly simple one for Senator Kevin Cramer of North Dakota. Asked what the reaction would be from voters back home if he were to support any significant form of gun control, the first-term Republican had a straightforward answer: “Most would probably throw me out of office,” he said. His response helps explain why Republicans have resisted proposals such as the one for universal background checks for gun buyers, despite remarkably broad support from the public for such plans — support that can reach up to 90 percent nationwide in some cases. Republicans like Mr. Cramer understand that they would receive little political reward for joining the push for laws to limit access to guns, including assault-style weapons. But they know for certain that they would be pounded — and most likely left facing a primary opponent who could cost them their job — for voting for gun safety laws or even voicing support for them. Most Republicans in the Senate represent deeply conservative states where gun ownership is treated as a sacred privilege enshrined in the Constitution, a privilege not to be infringed upon no matter how much blood is spilled in classrooms and school hallways around the country. Though the National Rifle Association has recently been diminished by scandal and financial turmoil , Democrats say that the organization still has a strong hold on Republicans through its financial contributions and support, hardening the party’s resistance to any new gun laws. — Carl Hulse, “ Why Republicans Won’t Budge on Guns .”

Yet while the power of the gun lobby, the outsize influence of rural states in the Senate and single-voter issues offer some explanation, there is another possibility: voters.

When voters in four Democratic-leaning states got the opportunity to enact expanded gun or ammunition background checks into law, the overwhelming support suggested by national surveys was nowhere to be found. For Democrats, the story is both unsettling and familiar. Progressives have long been emboldened by national survey results that show overwhelming support for their policy priorities, only to find they don’t necessarily translate to Washington legislation and to popularity on Election Day or beyond. President Biden’s major policy initiatives are popular , for example, yet voters say he has not accomplished much and his approval ratings have sunk into the low 40s. The apparent progressive political majority in the polls might just be illusory. Public support for new gun restrictions tends to rise in the wake of mass shootings. There is already evidence that public support for stricter gun laws has surged again in the aftermath of the killings in Buffalo and Uvalde, Texas. While the public’s support for new restrictions tends to subside thereafter, these shootings or another could still produce a lasting shift in public opinion. But the poor results for background checks suggest that public opinion may not be the unequivocal ally of gun control that the polling makes it seem. — Nate Cohn, “ Voters Say They Want Gun Control. Their Votes Say Something Different. ”

Second Amendment

Range v. attorney general.

Third Circuit Holds that a Nonviolent Offender May Not Be Stripped of Second Amendment Rights.

How States Can Limit Gun Violence

- Scott A. Budow

Bruen ’s Ricochet: Why Scored Live-Fire Requirements Violate the Second Amendment

Racism, abolition, and historical resemblance.

Forum response to Professor Bridges' Foreword

- Dorothy E. Roberts

Race in the Roberts Court

- Khiara M. Bridges

Inequality, Anti-Republicanism, and Our Unique Second Amendment

- Bertrall L. Ross II

Racist Gun Laws and the Second Amendment

- Adam Winkler

Parchment Rights

- Franita Tolson

Public Carry and Criminal Law after Bruen

Governing through gun crime: how chicago funded police after the 2020 blm protests.

- Robert Vargas

- Caitlin Loftus

Hot Topics: The Second Amendment and Gun Control

- Introduction to Gun Control Debate

The Second Amendment

- Mass Shootings

- Gun Legislation and Policies

- Grant Funding for Violence Prevention

- Contact Me Online This link opens in a new window

- Table of Cases

- Table of Supreme Court Decisions Overruled by Subsequent Decisions

- Table of Laws Held Unconstitutional in Whole or in Part by the Supreme Court

- Table of Supreme Court Justices

- Beyond the Constitution Annotated: Table of Additional Resources

- Methodologies for the Tables

van Alstyne, W. (1994). The Second Amendment and the Personal Right to Arms . Duke Law Journal , 43 (6), 1236–1255. https://doi.org/10.2307/1372856

Blocher, J., & Miller, D. A. H. (2016). What Is Gun Control? Direct Burdens, Incidental Burdens, and the Boundaries of the Second Amendment. The University of Chicago Law Review , 83 (1), 295–355. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43741601

Churchill, R. H. (2007). Gun Regulation, the Police Power, and the Right to Keep Arms in Early America: The Legal Context of the Second Amendment . Law and History Review , 25 (1), 139–175. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27641432

Halbrook, S. P. (1986). What the Framers Intended: A Linguistic Analysis of the Right to “Bear Arms. ” Law and Contemporary Problems , 49 (1), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.2307/1191615

Kates, D. B. (1986). The Second Amendment: A Dialogue. Law and Contemporary Problems , 49 (1), 143–150. https://doi.org/10.2307/1191614

Kates, D. B. (1983). Handgun Prohibition and the Original Meaning of the Second Amendment. Michigan Law Review , 82 (2), 204–273. https://doi.org/10.2307/1288537

Levinson, S. (1989). The Embarrassing Second Amendment. The Yale Law Journal , 99 (3), 637–659. https://doi.org/10.2307/796759

Williams, D. C. (1991). Civic Republicanism and the Citizen Militia: The Terrifying Second Amendment . The Yale Law Journal , 101 (3), 551–615. https://doi.org/10.2307/796867

Winkler, A. (2007). Scrutinizing the Second Amendment. Michigan Law Review , 105 (4), 683–733. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40041533

Yassky, D. (2000). The Second Amendment: Structure, History, and Constitutional Change . Michigan Law Review , 99 (3), 588–668. https://doi.org/10.2307/1290496

Big Think (Producer), & . (2019). The incredible history of the 2nd Amendment and America’s gun violence problem. [Video/DVD] Big Think. https://video.alexanderstreet.com/watch/the-incredible-history-of-the-2nd-amendment-and-america-s-gun-violence-problem

- << Previous: Introduction to Gun Control Debate

- Next: Mass Shootings >>

- Last Updated: Apr 23, 2024 12:24 PM

- URL: https://research.library.gsu.edu/secondamendment

Second Amendment :

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

Historical surveys of the Second Amendment often trace its roots, at least in part, through the English Bill of Rights of 1689, 1 Footnote See William Rawle , A View of the Constitution of the United States of America 126 (1829) ( “In England, a country which boasts so much of its freedom, the right was secured to protestant subjects only, on the revolution of 1688; and it is cautiously described to be that of bearing arms for their defence, ‘suitable to their conditions, and as allowed by law.’” ). which declared that “subjects, which are protestants, may have arms for their defence suitable to their condition, and as allowed by law.” 2 Footnote 3 Joseph Story , Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States § 1891 (1833) . That provision grew out of friction over the English Crown’s efforts to use loyal militias to control and disarm dissidents and enhance the Crown’s standing army, among other things, prior to the Glorious Revolution that supplanted King James II in favor of William and Mary. 3 Footnote Joyce Lee Malcolm , To Keep and Bear Arms: The Origins of an Anglo-American Right 115–16 (1994) .

The early American experience with militias and military authority would inform what would become the Second Amendment as well. In Founding-era America, citizen militias drawn from the local community existed to provide for the common defense, and standing armies of professional soldiers were viewed by some with suspicion. 4 Footnote See The Federalist No. 29 (Alexander Hamilton) (referencing proposition that “standing armies are dangerous to liberty” and militias are “the most natural defense of a free country” ). The Declaration of Independence listed as greivances against King George III that he had “affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power” and had “kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.” 5 Footnote The Declaration of Independence paras. 13–14 (U.S. 1776) . Following the Revolutionary War, several states codified constitutional arms-bearing rights in contexts that echoed these concerns—for instance, Article XIII of the Pennsylvania Declaration of Rights of 1776 read:

That the people have a right to bear arms for the defence of themselves and the state; and as standing armies in the time of peace are dangerous to liberty, they ought not to be kept up; And that the military should be kept under strict subordination to, and governed by, the civil power. 6 Footnote Pa. Declaration of Rights § XIII (1776) , in 5 The Federal and State Constitutions, Colonial Charters, and Other Organic Laws 3083 (Francis N. Thorpe ed., 1909) .

Similarly, as another example, Massachusetts’s Declaration of Rights from 1780 provided:

The people have a right to keep and to bear arms for the common defence. And as, in time of peace, armies are dangerous to liberty, they ought not to be maintained without the consent of the legislature; and the military power shall always be held in an exact subordination to the civil authority, and be governed by it. 7 Footnote Ma. Declaration of Rights § XVII (1780) , in 3 id. at 1892.

Mistrust of standing armies, like the one employed by the English Crown to control the colonies, and anti-Federalist concerns with centralized military power colored the debate surrounding ratification of the federal Constitution and the need for a Bill of Rights. 8 Footnote See, e.g. , 3 The Debates in the Several State Conventions, on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution, As Recommended by the General Convention at Philadelphia in 1787 , at 401 (Jonathan Elliot ed., 1836) (statement of Gov. Edmund Randolph) ( “With respect to a standing army, I believe there was not a member in the federal Convention, who did not feel indignation at such an institution.” ). Provisions in the Constitution gave Congress power to establish and fund an Army, 9 Footnote U.S. Const. art. II, § 8, cl. 12 . as well as authority to organize, arm, discipline, and call forth the militia in certain circumstances (while reserving to the states authority over appointment of militia officers and training). 10 Footnote Id. art. II, § 8, cl. 15–16 . The motivation for these provisions appears to have been “recognition of the danger of relying on inadequately trained soldiers as the primary means of providing for the common defense.” 11 Footnote Perpich v. Dep’t of Def., 496 U.S. 334, 340 (1990) . However, despite structural limitations such as a two-year limit on Army appropriations and certain militia reservations to the states, fears remained during the ratification debates that these provisions of the Constitution gave too much power to the federal government and were dangerous to liberty. 12 Footnote See Steven J. Heyman , Natural Rights and the Second Amendment , in The Second Amendment in Law and History: Historians and Constitutional Scholars on the Right to Bear Arms 200–01 (Carl T. Bogus ed., 2000) (collecting anti-federalist objections regarding power over militia and “to raise a standing army that could be used to destroy public liberty and erect a military despotism” ).

In The Federalist , James Madison argued that “the State governments, with the people on their side,” would be more than adequate to counterbalance a federally controlled “regular army,” even one “fully equal to the resources of the country.” 13 Footnote The Federalist No. 46 (James Madison) . In Madison’s view, “the advantage of being armed,” together with “the existence of subordinate governments, to which the people are attached, and by which the militia officers are appointed, forms a barrier against the enterprises of ambition, more insurmountable than any which a simple government of any form can admit of.” 14 Footnote Id. Nevertheless, several states considered or proposed to the First Congress constitutional amendments that would explicitly protect arms-bearing rights, in various formulations. 15 Footnote E.g. , Amendments Proposed by the Virginia Convention June 27, 1788 , in Creating the Bill of Rights: the Documentary Record from the First Federal Congress 19 (Helen E. Veit et al. eds., 1991) (proposing among other things, “[t]hat the people have a right to keep and bear arms; that a well regulated Militia composed of the body of the people trained to arms is the proper, natural and safe defence of a free State[,]” and “[t]hat any person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms ought to be exempted upon payment of an equivalent to employ another to bear arms in his stead” ); Amendments Proposed by the New York Convention July 26, 1788 , in id. at 22 (proposing similar language but omitting religious-objector provision); Amendments Proposed by the New Hampshire Convention June 21, 1788 , in id. at 17 (proposing that “Congress shall never disarm any Citizen unless such as are or have been in Actual Rebellion” ).

Tasked with “digesting the many proposals for amendments made by the various state ratification conventions and stewarding them through the First Federal Congress,” 16 Footnote Saul Cornell , A Well-Regulated Militia: The Founding Fathers and the Origins of Gun Control in America 59 (2006) . James Madison produced an initial draft of the Second Amendment as follows:

The right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed; a well armed and well regulated militia being the best security of a free country: but no person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms shall be compelled to render military service in person. 17 Footnote 1 Annals of Cong. 451 (1789) (Joseph Gales ed., 1834) .

The committee of the House of Representatives that considered Madison’s formulation altered the order of the clauses such that the militia clause now came first, with a new specification of the militia as “composed of the body of the people,” and made several other wording and punctuation changes. 18 Footnote The Complete Bill of Rights: The Drafts, Debates, Sources, & Origins 264 (Neil H. Cogan ed., 2015) (House Committee of Eleven Report, July 28, 1789) [hereinafter, Complete Bill of Rights ].

Debate in the House largely centered on the proposed Amendment’s religious-objector clause, with Elbridge Gerry, for instance, arguing that the clause would give “the people in power” the ability to “declare who are those religiously scrupulous, and prevent them from bearing arms.” 19 Footnote 1 Annals of Cong. 778 (1789) (Joseph Gales ed., 1834) . Gerry proposed that the provision “be confined to persons belonging to a religious sect scrupulous of bearing arms,” but his proposed addition was not accepted. 20 Footnote Id. at 779 . Other proposals not accepted included striking out the entire clause, making it subject to “paying an equivalent,” which Roger Sherman found problematic given religious objectors would be “equally scrupulous of getting substitutes or paying an equivalent,” 21 Footnote Id. and adding after “a well regulated militia” the phrase “trained to arms,” which Elbridge Gerry believed would make clear that it was “the duty of the Government” to provide the referenced security of a free State. 22 Footnote Id. at 780 .

As resolved by the House of Representatives on August 24, 1789, the version of the Second Amendment sent to the Senate remained similar to the version initially drafted by James Madison, with one of the largest changes being the re-ordering of the first two clauses. 23 Footnote Complete Bill of Rights , supra 18, at 267 (House Resolution, August 24, 1789). The provision at that time read:

A well regulated militia, composed of the body of the People, being the best security of a free State, the right of the People to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed, but no one religiously scrupulous of bearing arms, shall be compelled to render military service in person. 24 Footnote Complete Bill of Rights , supra 18, at 267 (House Resolution, August 24, 1789).

The Amendment would take what would become its final form in the Senate, where the religious-objector clause was finally removed and several other phrases were modified. 25 Footnote Any Senate debate of what would become the Second Amendment does not survive in recorded form. See James H. Hutson , The Creation of the Constitution: The Integrity of the Documentary Record , 65 Tex. L. Rev. 1 , 36 (1986) ( “The documentary record of debates on the Bill of Rights consists . . . of deliberations in the House of Representatives.” ). For instance, the phrase referencing the militia as “composed of the body of the People” was struck, and the descriptor of the militia as “the best security of a free State” was modified to “necessary to the security of a free State.” 26 Footnote Complete Bill of Rights , supra 18, at 270 . Several other changes were proposed and rejected, including adding limitations on a standing army “in time of peace” and adding next to the words “bear arms” the phrase “for the common defence.” 27 Footnote Complete Bill of Rights , supra 18, at 268–69 . The final language of the Second Amendment was agreed to and transmitted to the states in late September of 1789. 28 Footnote Complete Bill of Rights , supra 18, at 274 .

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Key facts about Americans and guns

Guns are deeply ingrained in American society and the nation’s political debates.

The Second Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees the right to bear arms, and about a third of U.S. adults say they personally own a gun. At the same time, in response to concerns such as rising gun death rates and mass shootings , President Joe Biden has proposed gun policy legislation that would expand on the bipartisan gun safety bill Congress passed last year.

Here are some key findings about Americans’ views of gun ownership, gun policy and other subjects, drawn primarily from a Pew Research Center survey conducted in June 2023 .

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to summarize key facts about Americans and guns. We used data from recent Center surveys to provide insights into Americans’ views on gun policy and how those views have changed over time, as well as to examine the proportion of adults who own guns and their reasons for doing so.

The analysis draws primarily from a survey of 5,115 U.S. adults conducted from June 5 to June 11, 2023. Everyone who took part in the surveys cited is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Here are the questions used for the analysis on gun ownership , the questions used for the analysis on gun policy , and the survey’s methodology .

Additional information about the fall 2022 survey of parents and its methodology can be found at the link in the text of this post.

Measuring gun ownership in the United States comes with unique challenges. Unlike many demographic measures, there is not a definitive data source from the government or elsewhere on how many American adults own guns.

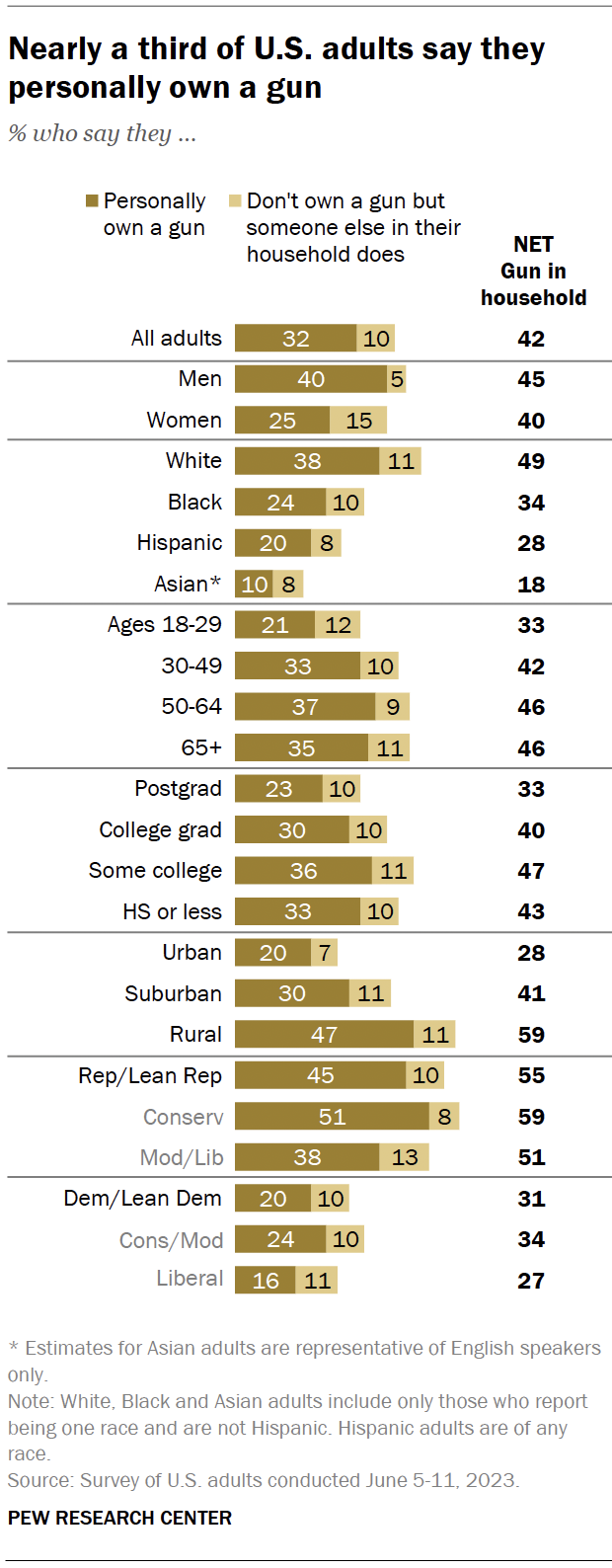

The Pew Research Center survey conducted June 5-11, 2023, on the Center’s American Trends Panel, asks about gun ownership using two separate questions to measure personal and household ownership. About a third of adults (32%) say they own a gun, while another 10% say they do not personally own a gun but someone else in their household does. These shares have changed little from surveys conducted in 2021 and 2017 . In each of those surveys, 30% reported they owned a gun.

These numbers are largely consistent with rates of gun ownership reported by Gallup , but somewhat higher than those reported by NORC’s General Social Survey . Those surveys also find only modest changes in recent years.

The FBI maintains data on background checks on individuals attempting to purchase firearms in the United States. The FBI reported a surge in background checks in 2020 and 2021, during the coronavirus pandemic. The number of federal background checks declined in 2022 and through the first half of this year, according to FBI statistics .

About four-in-ten U.S. adults say they live in a household with a gun, including 32% who say they personally own one, according to an August report based on our June survey. These numbers are virtually unchanged since the last time we asked this question in 2021.

There are differences in gun ownership rates by political affiliation, gender, community type and other factors.

- Republicans and Republican-leaning independents are more than twice as likely as Democrats and Democratic leaners to say they personally own a gun (45% vs. 20%).

- 40% of men say they own a gun, compared with 25% of women.

- 47% of adults living in rural areas report personally owning a firearm, as do smaller shares of those who live in suburbs (30%) or urban areas (20%).

- 38% of White Americans own a gun, compared with smaller shares of Black (24%), Hispanic (20%) and Asian (10%) Americans.

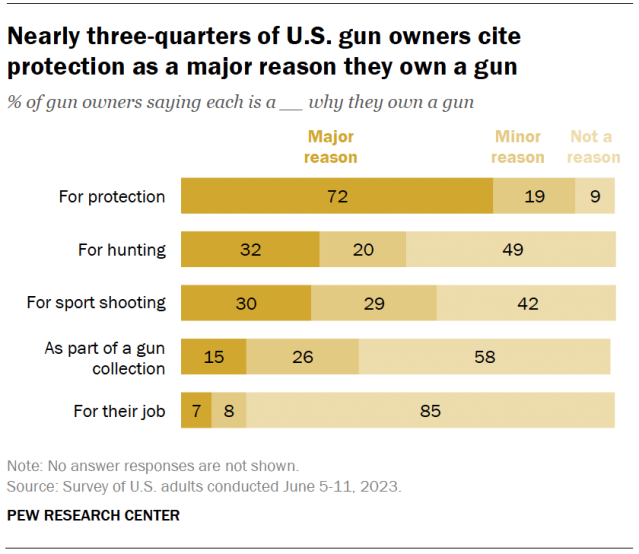

Personal protection tops the list of reasons gun owners give for owning a firearm. About three-quarters (72%) of gun owners say that protection is a major reason they own a gun. Considerably smaller shares say that a major reason they own a gun is for hunting (32%), for sport shooting (30%), as part of a gun collection (15%) or for their job (7%).

The reasons behind gun ownership have changed only modestly since our 2017 survey of attitudes toward gun ownership and gun policies. At that time, 67% of gun owners cited protection as a major reason they owned a firearm.

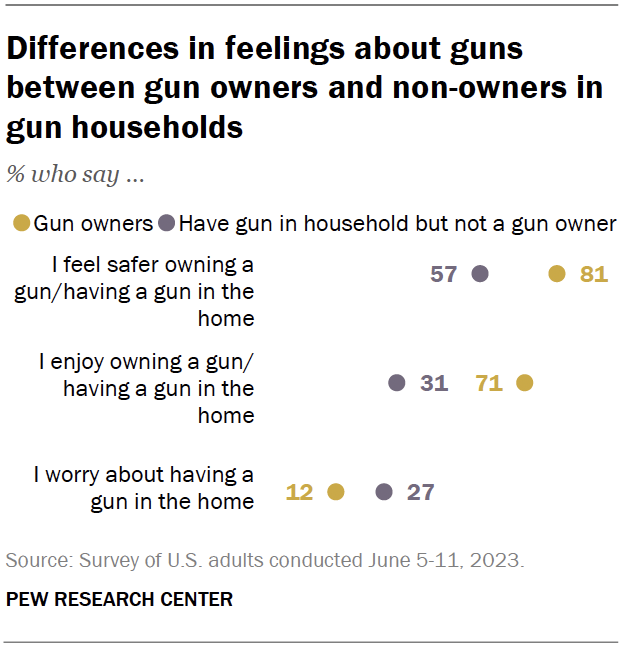

Gun owners tend to have much more positive feelings about having a gun in the house than non-owners who live with them. For instance, 71% of gun owners say they enjoy owning a gun – but far fewer non-gun owners in gun-owning households (31%) say they enjoy having one in the home. And while 81% of gun owners say owning a gun makes them feel safer, a narrower majority (57%) of non-owners in gun households say the same about having a firearm at home. Non-owners are also more likely than owners to worry about having a gun in the home (27% vs. 12%, respectively).

Feelings about gun ownership also differ by political affiliation, even among those who personally own firearms. Republican gun owners are more likely than Democratic owners to say owning a gun gives them feelings of safety and enjoyment, while Democratic owners are more likely to say they worry about having a gun in the home.

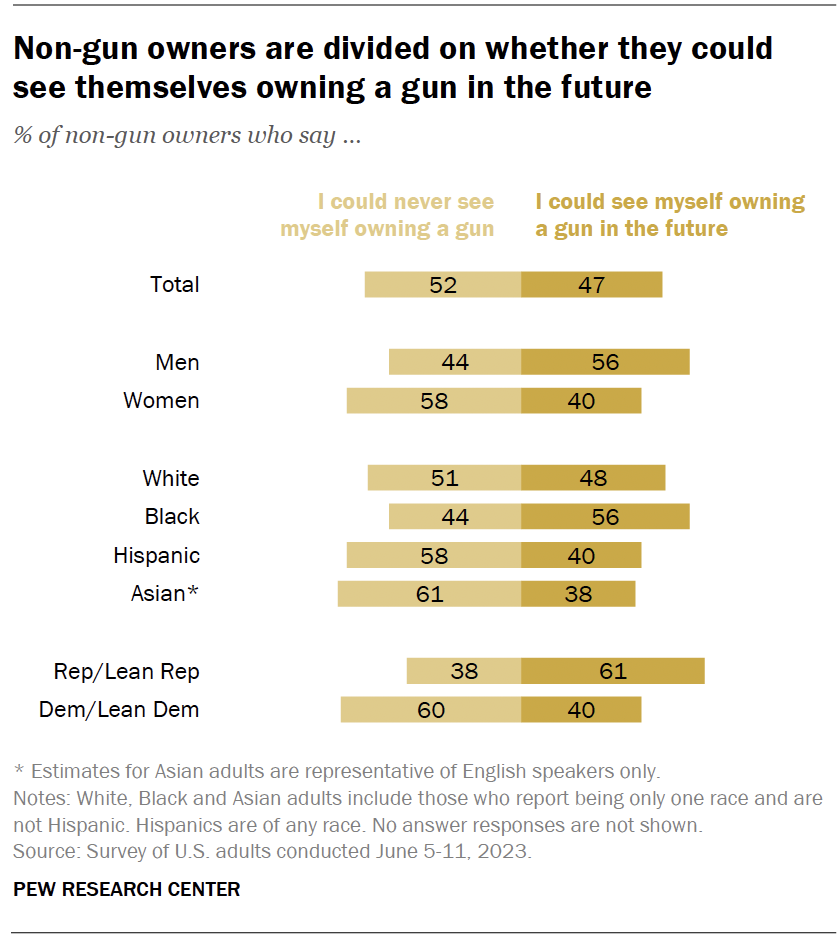

Non-gun owners are split on whether they see themselves owning a firearm in the future. About half (52%) of Americans who don’t own a gun say they could never see themselves owning one, while nearly as many (47%) could imagine themselves as gun owners in the future.

Among those who currently do not own a gun:

- 61% of Republicans and 40% of Democrats who don’t own a gun say they would consider owning one in the future.

- 56% of Black non-owners say they could see themselves owning a gun one day, compared with smaller shares of White (48%), Hispanic (40%) and Asian (38%) non-owners.

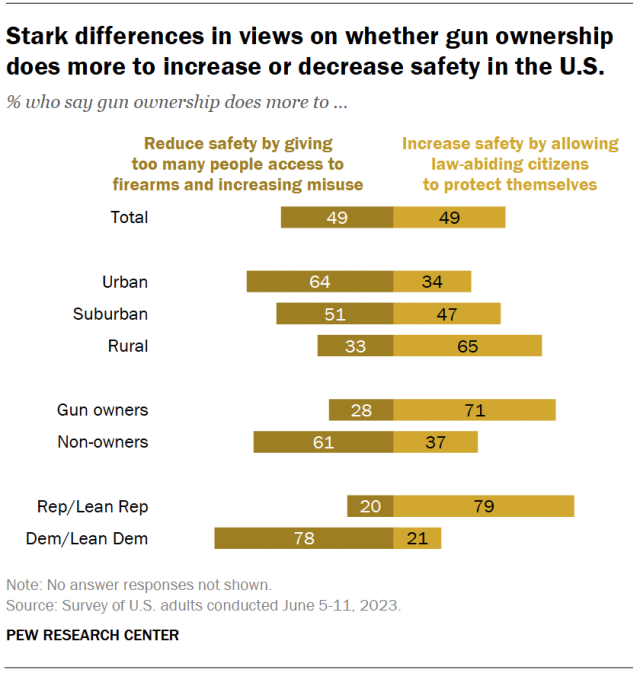

Americans are evenly split over whether gun ownership does more to increase or decrease safety. About half (49%) say it does more to increase safety by allowing law-abiding citizens to protect themselves, but an equal share say gun ownership does more to reduce safety by giving too many people access to firearms and increasing misuse.

Republicans and Democrats differ on this question: 79% of Republicans say that gun ownership does more to increase safety, while a nearly identical share of Democrats (78%) say that it does more to reduce safety.

Urban and rural Americans also have starkly different views. Among adults who live in urban areas, 64% say gun ownership reduces safety, while 34% say it does more to increase safety. Among those who live in rural areas, 65% say gun ownership increases safety, compared with 33% who say it does more to reduce safety. Those living in the suburbs are about evenly split.

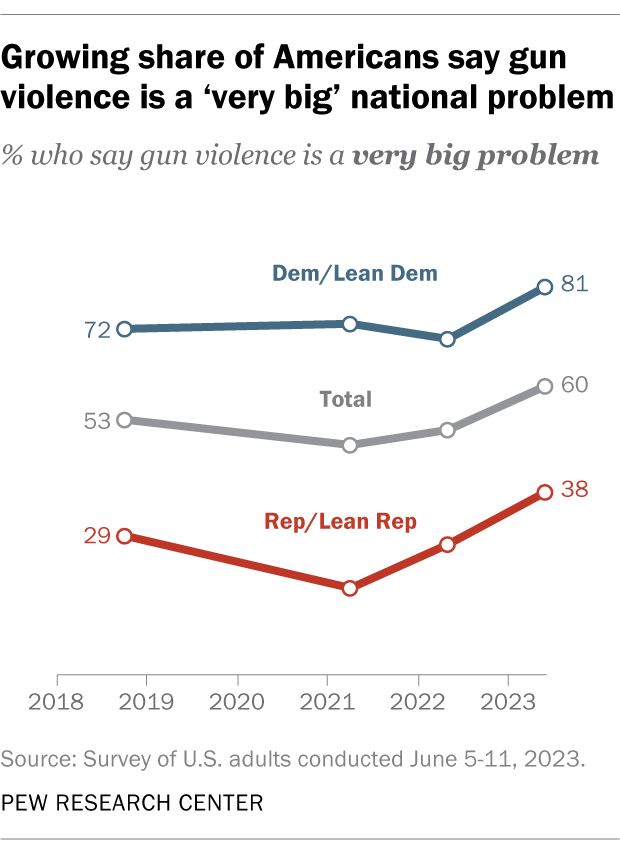

Americans increasingly say that gun violence is a major problem. Six-in-ten U.S. adults say gun violence is a very big problem in the country today, up 9 percentage points from spring 2022. In the survey conducted this June, 23% say gun violence is a moderately big problem, and about two-in-ten say it is either a small problem (13%) or not a problem at all (4%).

Looking ahead, 62% of Americans say they expect the level of gun violence to increase over the next five years. This is double the share who expect it to stay the same (31%). Just 7% expect the level of gun violence to decrease.

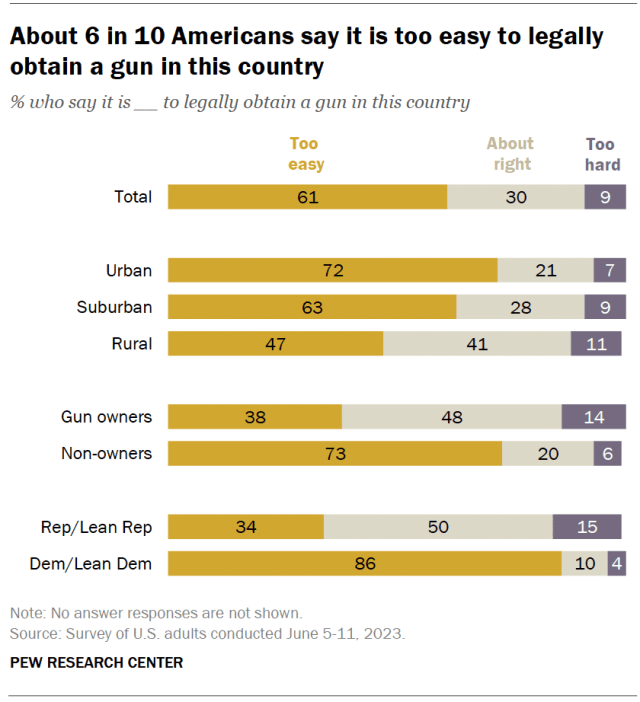

A majority of Americans (61%) say it is too easy to legally obtain a gun in this country. Another 30% say the ease of legally obtaining a gun is about right, and 9% say it is too hard to get a gun. Non-gun owners are nearly twice as likely as gun owners to say it is too easy to legally obtain a gun (73% vs. 38%). Meanwhile, gun owners are more than twice as likely as non-owners to say the ease of obtaining a gun is about right (48% vs. 20%).

Partisan and demographic differences also exist on this question. While 86% of Democrats say it is too easy to obtain a gun legally, 34% of Republicans say the same. Most urban (72%) and suburban (63%) dwellers say it’s too easy to legally obtain a gun. Rural residents are more divided: 47% say it is too easy, 41% say it is about right and 11% say it is too hard.

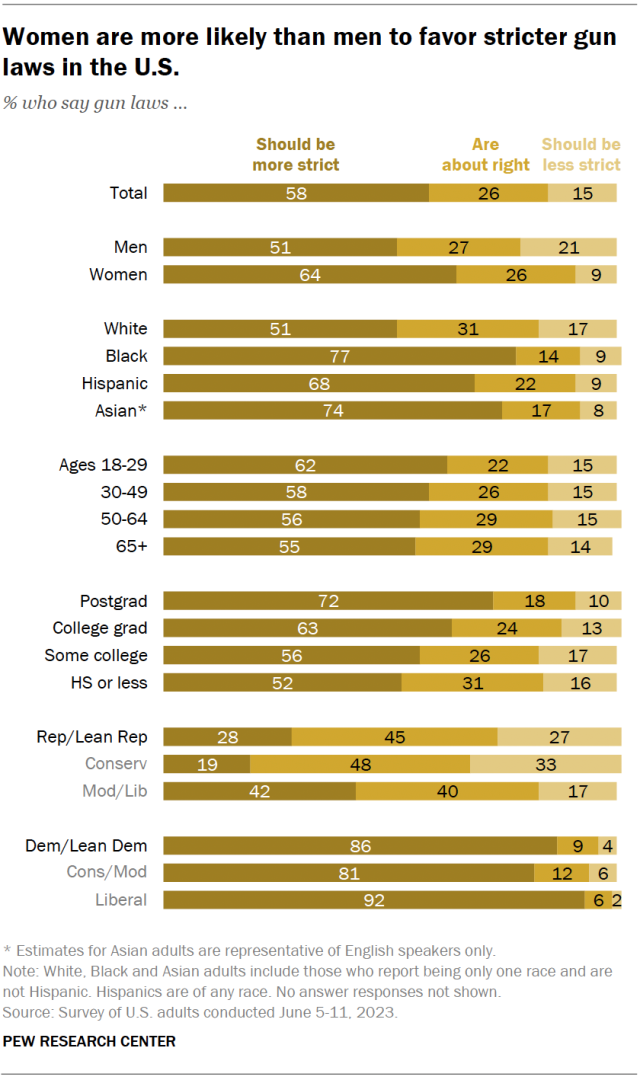

About six-in-ten U.S. adults (58%) favor stricter gun laws. Another 26% say that U.S. gun laws are about right, and 15% favor less strict gun laws. The percentage who say these laws should be stricter has fluctuated a bit in recent years. In 2021, 53% favored stricter gun laws, and in 2019, 60% said laws should be stricter.

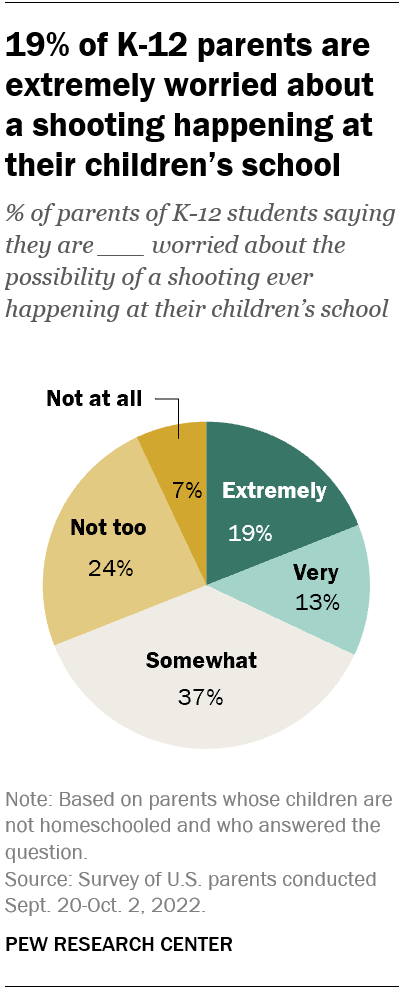

About a third (32%) of parents with K-12 students say they are very or extremely worried about a shooting ever happening at their children’s school, according to a fall 2022 Center survey of parents with at least one child younger than 18. A similar share of K-12 parents (31%) say they are not too or not at all worried about a shooting ever happening at their children’s school, while 37% of parents say they are somewhat worried.

Among all parents with children under 18, including those who are not in school, 63% see improving mental health screening and treatment as a very or extremely effective way to prevent school shootings. This is larger than the shares who say the same about having police officers or armed security in schools (49%), banning assault-style weapons (45%), or having metal detectors in schools (41%). Just 24% of parents say allowing teachers and school administrators to carry guns in school would be a very or extremely effective approach, while half say this would be not too or not at all effective.

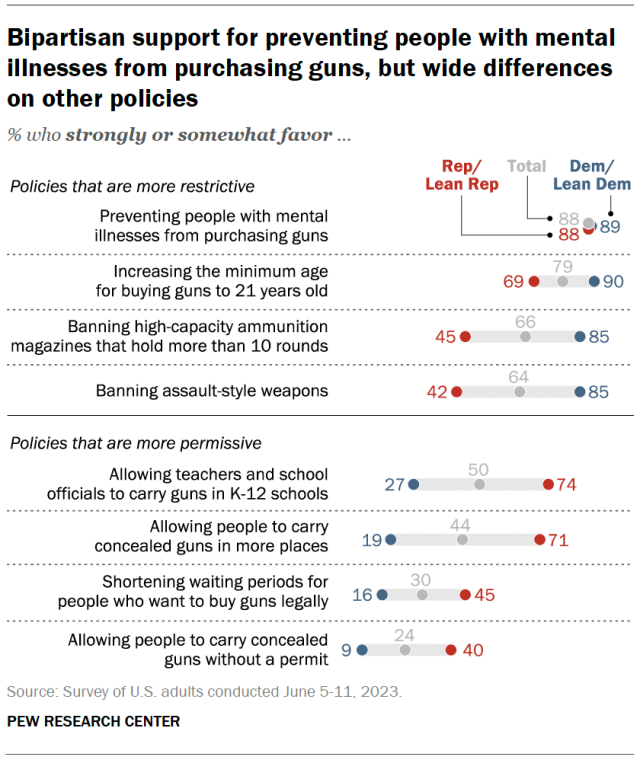

There is broad partisan agreement on some gun policy proposals, but most are politically divisive, the June 2023 survey found . Majorities of U.S. adults in both partisan coalitions somewhat or strongly favor two policies that would restrict gun access: preventing those with mental illnesses from purchasing guns (88% of Republicans and 89% of Democrats support this) and increasing the minimum age for buying guns to 21 years old (69% of Republicans, 90% of Democrats). Majorities in both parties also oppose allowing people to carry concealed firearms without a permit (60% of Republicans and 91% of Democrats oppose this).

Republicans and Democrats differ on several other proposals. While 85% of Democrats favor banning both assault-style weapons and high-capacity ammunition magazines that hold more than 10 rounds, majorities of Republicans oppose these proposals (57% and 54%, respectively).

Most Republicans, on the other hand, support allowing teachers and school officials to carry guns in K-12 schools (74%) and allowing people to carry concealed guns in more places (71%). These proposals are supported by just 27% and 19% of Democrats, respectively.

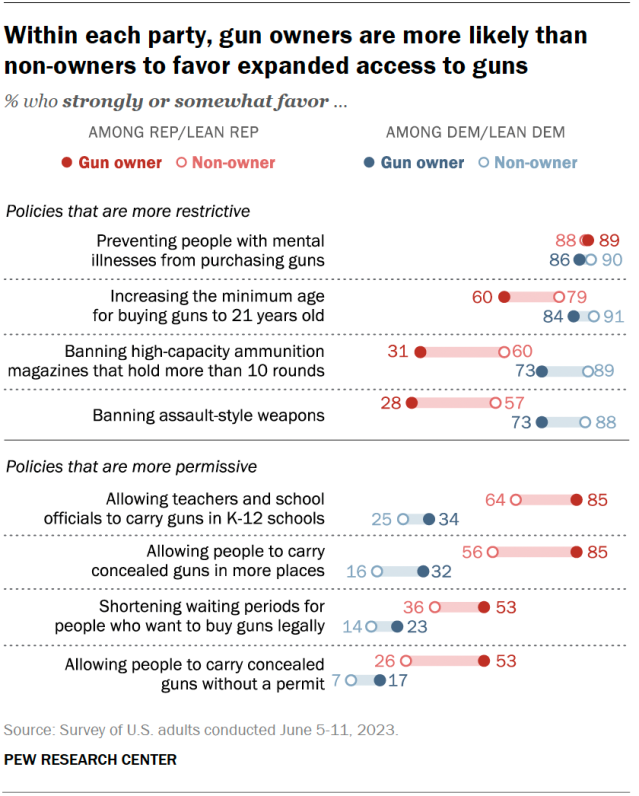

Gun ownership is linked with views on gun policies. Americans who own guns are less likely than non-owners to favor restrictions on gun ownership, with a notable exception. Nearly identical majorities of gun owners (87%) and non-owners (89%) favor preventing mentally ill people from buying guns.

Within both parties, differences between gun owners and non-owners are evident – but they are especially stark among Republicans. For example, majorities of Republicans who do not own guns support banning high-capacity ammunition magazines and assault-style weapons, compared with about three-in-ten Republican gun owners.

Among Democrats, majorities of both gun owners and non-owners favor these two proposals, though support is greater among non-owners.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published on Jan. 5, 2016 .

- Partisanship & Issues

- Political Issues

Katherine Schaeffer is a research analyst at Pew Research Center

About 1 in 4 U.S. teachers say their school went into a gun-related lockdown in the last school year

Striking findings from 2023, for most u.s. gun owners, protection is the main reason they own a gun, gun violence widely viewed as a major – and growing – national problem, what the data says about gun deaths in the u.s., most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Am J Public Health

- v.108(7); Jul 2018

The Second Amendment and Firearms Regulation: A Venerable Tradition Regulating Liberty While Securing Public Safety

Both authors contributed equally to this editorial.

Firearms violence in the United States has reached epidemic proportions, with more than 30 000 Americans dying as a result of gun violence each year. 1 Proposals for more effective gun regulation inevitably trigger arguments that the Second Amendment poses limits on such policies and that reasonable regulations are infringements on Second Amendment rights. This view, however, does not have a solid foundation in either American history or law. As long as there have been guns in America, there has been regulation of firearms.

ANGLO-AMERICAN LAW ROOTS

The settlers who migrated to America brought a variety of gun regulations with them. The individual colonies also supplemented these regulations with their own laws aimed at preserving the peace. Restrictions on the storage of gunpowder, prohibitions on armed travel in public, and the disarmament of those deemed potentially dangerous are all examples of regulations that have ancient roots in Anglo-American law. 2 Two specific illustrations are 1715 Massachusetts Acts 311, An Act in Addition to an Act for Erecting of a Powder-house in Boston ( bit.ly/2qJ9FOM ), an early example of a law regulating how gunpowder was stored, and An Act Against Wearing Swords, Etc. ( bit.ly/2qOeYgb ), a New Jersey law prohibiting public carry of a variety of weapons. Both of these colonial laws demonstrate the robust power of the state to regulate weapons, including firearms, to promote public health and safety.

Another instance of the broad scope of state power to regulate arms dates to an even earlier period of Anglo-American law. Consider the restrictions imposed by the Statute of Northampton, a law enacted during the reign of King Edward III in the 14th century. It prohibited any individual from traveling armed in populous areas or coming before the king’s ministers with arms. Before the age of modern police forces, much of the day-to-day enforcement of law was community based and depended on justices of the peace who enjoyed broad powers to maintain public order and safety, including the power to detain, disarm, arrest, and imprison those who threatened the peace. Indeed, any member of the local community could approach a local justice of the peace and demand that an individual who posed a potential threat be forced to provide a peace bond, something akin to the types of bail bonds currently used when suspects in criminal prosecutions await trial. 3

MODERN AMERICAN LAW

Although the Second Amendment is often invoked by both sides in the contemporary gun debate, each side tends to focus on only part of the amendment. The entire text reads as follows: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed” ( http://bit.ly/2KxUDEL ). The National Rifle Association and other gun rights groups are fond of quoting the latter part of the amendment, which affirms the right to keep and bear arms. Conversely, gun control supporters typically focus their attention on the part of the text asserting the necessity of a well-regulated militia. The portion of the amendment that is largely ignored in today’s debate is that linking both of these parts to “the security of a free State.” 4

The framers and adopters of the Second Amendment certainly feared tyranny, but they also feared anarchy. 5 In their view, there could be no liberty without regulation and the rule of law. This is a vital principle of America’s constitutional tradition. Indeed, in the decades after the adoption of the Second Amendment, levels of gun regulation in America increased as opposed to decreasing. Although each side in today’s great American gun debate claims to be the true heir of the founding generation and the Second Amendment, the historical truth is that both sides are actually products of a later period in American history.

Today's gun rights and gun control movements are actually products of America's first gun violence epidemic, a public health crisis that emerged decades after the adoption of the Second Amendment in the early 19th century. Rates of gun violence at the time of the Second Amendment were relatively low, and only a tiny fraction of Americans owned handguns. As is the case today, gun violence was largely a problem associated with the proliferation of handguns. Given this fact, it is hardly surprising that not until the development and marketing of cheap and reliable pistols, decades after the adoption of the Second Amendment, were the first modern gun control laws passed. These laws also triggered the first court cases testing the meaning of the right to keep and bear arms. Although most courts accepted the need for reasonable regulations, a few courts in the slave South embraced a more libertarian vision of the right to keep and bear arms. 6

The two positions—gun rights and gun control, the opposing views that dominate modern debate over gun policies—have little to do with the original Second Amendment but are products of this later moment. Americans have been arguing over the meaning and scope of the right to keep and bears since the first gun violence epidemic. Then as now, most Americans accepted that the right to bear arms was perfectly consistent with a wide range of firearms regulations. 7 Modern laws such as “extreme risk protection orders” that seek to remove firearms from those who demonstrate a threat to personal or public safety are thus part of a long legal history extending back more than five centuries, a venerable tradition that seeks to regulate liberty while securing public safety. Scouring the history of gun regulation, one could find many other examples of ancient precedents for robust regulation of firearms today.

RECLAIMING A LEGACY

Both gun rights advocates and champions of gun control need to understand that regulation of firearms is not a new development in American legal history but, rather, a tradition that predates the creation of America by centuries. Legislation designed to improve public safety and reduce firearm violence is fully consistent with the American legal tradition. The majority of Americans who seek and support reasonable regulation can reclaim this legacy.

See also Galea and Vaughan, p. 856 ; and the Gun Violence Prevention Section, pp. 858 – 888 .

The only newsroom dedicated to covering gun violence.

In guns we trust, guns are as old as america — but so are gun laws.

Gun restrictions were not always so fraught in America. The second episode of “Long Shadow: In Guns We Trust” explains how the National Rifle Association seized on the Second Amendment to change the course of history.

Go beyond the headlines.

Your weekly briefing on gun violence..

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Email a link to this page

It’s hard to imagine, but for most of American history, guns were not a contentious topic. The Second Amendment wasn’t a matter of much debate or even thought — until the 1920s and ‘30s.

That’s when Tommy guns, the first handheld machine guns, were implicated in some very visible shootings, spurring the federal gun control law. The National Firearms Act taxed and heavily regulated machine guns — and originally included handguns, until the National Rifle Association intervened.

But the NRA of the 1930s wasn’t as hardline as it is today: Then-NRA president Karl Frederick testified before Congress that he didn’t believe in the “promiscuous toting of guns.” And he didn’t even cite the Second Amendment — he cited the need for self-defense in rural areas.

In the first episode of “Long Shadow: In Guns We Trust,” host Garrett Graff explored the legacy of Columbine. In the second episode, he delves into the history of the Second Amendment, and how it became a rallying cry for the nascent gun lobby. He discovers that guns are as old as America — but so are gun laws.

“Long Shadow: In Guns We Trust” is produced by Long Lead and Campside Media in collaboration with The Trace, and distributed by PRX. Listen and follow on Apple, Spotify, Amazon Music, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Garrett Graff: A note for listeners: On and across this season, there are repeated mentions of guns, gun violence, and their collective toll on our society and our psyche. Please take care while you listen.

Garrett Graff: The state bird of Florida has been the same since 1927 — the northern mockingbird. The bird you’re hearing right now. For seven decades the mockingbird sat peacefully on its Florida throne. But it’s also the state bird of Arkansas, Mississippi , Tennessee, and Texas. So in the 1990s, the Florida Audubon Society started drumming up support for a new candidate: the Florida scrub-jay. The scrub-jay was teetering close to extinction, and the Audubon Society thought a publicity boost could help increase its chances of survival. Plus, the scrub-jay was endemic to Florida — a uniquely Floridian bird to represent a unique state. A high school teacher who had heard about the Audubon Society campaign brought it to his students as a project in civic engagement, and the kids took up the cause with a passion. They wrote letters to their legislators and traveled to other schools in the county. They convinced thousands of fellow students to ask legislators to put forward a bill on the scrub-jay’s behalf. And the legislators did.

Mike Spies: And kids came down to the legislature to testify in support of the new bird and to petition the government to make the change.

Garrett Graff: This is Mike Spies, senior writer for The Trace, a nonprofit newsroom covering guns in America, and our partner this season.

Mike Spies: They all went through it — it was obviously extremely uncontroversial.

Garrett Graff: State representative Howard Futch sponsored the bill and brought it to committee in April 1999.

Rep. Howard Futch: This bird has really got family values. The young come back to take care of the new ones. The families work closely together for food and everything.

Garrett Graff: The Audubon Society and the students had thought that the bill would pass easily, but they’d underestimated the vengeful streak of one of Florida’s most influential people.

Mike Spies: So then out of nowhere, Marion showed up.

Garrett Graff: NRA lobbyist Marion Hammer. She had no interest in this break with tradition.

Marion Hammer: You see, scrub-jays are lazy and scurrilous. They eat the eggs and nestlings of other birds. To me, that’s robbery and murder, and it’s not good family values.

Garrett Graff: She’s one of the voices you heard on that NRA conference call in episode one. She seemed to have a deep-seated dislike for the Florida scrub-jay.

Mike Spies: She was the only person who spoke out against changing the bird, and said that the bird had a welfare mentality, and was known for, like, stealing the eggs from other birds.

Garrett Graff: Why would Hammer, arbiter of all things guns in the state of Florida, care so much about this bird? Turns out, the scrub-jay may have been collateral damage for an entirely different dispute — a dispute about guns.

Mike Spies: Some minor gun restriction got enshrined into law and she blamed one particular guy for that. And that guy had nothing to do with guns. Yeah, he was a bird person.

Garrett Graff: That guy was Clay Henderson. Clay Henderson: I’m a retired long-time environmental lawyer and advocate.

Garrett Graff: He was president of Florida’s Audubon Society in 1999. And in 1998, he’d been appointed to Florida’s Constitution Revision Commission. Every 20 years, specially appointed state commissioners propose revisions to the Florida Constitution, revisions then put directly to voters during the next general election.

Clay Henderson: Where I was involved was that we had a bundle of environmental initiatives that we wanted to bring forward — you know, environmental bill of rights, independent wildlife commission, things like that. But one of the other issues that was extremely controversial was to allow local governments the ability to impose a waiting period for purchase of handguns.

Garrett Graff: Much to Hammer’s chagrin, the amendment passed — with more than 70 percent of the popular vote. So when her latest enemy began a campaign to change the state bird, she showed up.

Clay Henderson: And she claimed it wasn’t personal, that she just loved mockingbirds. Well, you know, I didn’t quite buy that. (laughs)

Garrett Graff: The mockingbird had found a powerful ally in Marion Hammer. The scrub-jay had the students; the mockingbird had the NRA’s top lobbyist.

Mike Spies: And she won. The measure got defeated. And then it happened, like, multiple times after that. Every time someone brought up the issue, she would come down to the legislature to lobby against it. And every time she — it almost became like an annual tradition.

Garrett Graff: The message was clear: Cross Hammer, and you — along with whatever your personal scrub-jay is — will pay.

Mike Spies: And that’s just a good example. You know, it doesn’t matter how marginal it is. I think for her, in order to be effective, she had to demonstrate that she could push people to do what she wanted, that she was able, even arbitrarily, to demonstrate her power.

Garrett Graff: The campaign for the scrub-jay continues in various forms, but so does Hammer’s vehement opposition: In 2023, more than two decades later, Hammer penned an op-ed for the Tallahassee Democrat, where she described scrub-jays as, quote, “evil little birds” that “can’t even sing.” Mockingbirds, on the other hand, she described as “family protectors” that “chase off intruders who get too close to their nests.” One could extrapolate that Marion Hammer believes, if the opportunity were available to them, mockingbirds are the type of bird that would keep a gun on hand to defend their home and their property. The bio for that op-ed describes Hammer as a mother and a grandmother. But of course, she’s a lot more than that. Clay Henderson: Florida is like the Wild Wild West when it comes to guns, you know, so … Marion Hammer is primarily responsible for that.

Garrett Graff: Mike Spies spent a year reporting on the NRA lobbyist’s unchecked influence for an investigation published by The Trace and The New Yorker in 2018. In it, he documented how she’s the architect of some of the country’s most pervasive and impactful pro-gun laws, from Stand Your Ground to open carry, and a relentless defender of the Second Amendment.

Mike Spies: The sort of notion to be as confrontational and divisive and harsh as possible, as absolutist as possible, I mean that posture is her posture and has also become the movement’s posture.

Garrett Graff: We take the NRA’s approach for granted today; it’s part of the American political furniture: Republicans are pro-gun, Democrats are anti-gun, and the NRA will do whatever it takes to keep guns in the hands of every law-abiding citizen. But the NRA wasn’t always like this. In fact, America wasn’t always like this. There was a time before, a time with plenty of its own serious problems, but when guns were not the intractable issue they’ve become today. Up until the latter decades of the 20th century, guns weren’t front and center in U.S. politics. And from Long Lead, PRX and Campside Media, in collaboration with The Trace, I’m Garrett Graff and this is Long Shadow: In Guns We Trust. Episode two: “Shall Not Be Infringed.”

Garrett Graff: Guns have been a part of our history since the very beginning — we were after all a country founded in armed revolution — but there are a couple moments that stand out. To understand how guns became a third rail in American political life, we have to go back to the 1920s and ‘30s. America’s relationship with guns begins to change, thanks to a groundbreaking new invention.

[ Newsreel : Compared with modern arms, the ancient muskets were as deadly as slings and catapults, though they made more noise. Contrast them for instance with the Thompson submachine gun, or the “Tommy gun,” as it’s called. It’s an automatic weapon capable of delivering a high rate of fire. Let’s see how it works.]

Garrett Graff: The Tommy gun was the first handheld machine gun. It was originally designed for U.S. troops in World War I, but it came too late to be used in the war, and instead was later made available to civilians. In the ‘20s, amid Prohibition, the guns became a key feature of organized crime.

Robert Spitzer: You begin to hear stories about criminals using Tommy guns to commit pretty heinous crimes.

Garrett Graff: Professor Robert Spitzer has been studying the history of gun policy for 40 years, and has written five books on the subject.

Robert Spitzer: And in the space of a year or two, this becomes a major, major news story in the way that mass shootings today grab headlines.

Garrett Graff: The Tommy gun became a favorite among bootleggers, bank robbers, and gangsters. There was Machine Gun Kelly, nicknamed for his love of the Tommy gun — and Bonnie and Clyde, John Dillinger, Baby Face Nelson, Bugs Moran, and, of course, Al Capone.

[ Clip from The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre: Al Capone. He invented the rubout and the ride, introduced the Tommy gun to gangland. He pushed the button for hundreds of underworld executions.]

Garrett Graff: Two Tommy guns were used in the infamous 1929 St. Valentine’s Day massacre, a gangland execution of seven men, presumably ordered by Capone. And there was another event that especially captured the public’s attention. One morning in 1933, FBI agents were transporting a notorious gangster named Frank Nash from Kansas City back to the prison he’d escaped in Leavenworth. Back then, the FBI didn’t yet have the power to arrest people or even carry firearms, so they were working with local police officers. They had arrived on an overnight train at Union Station, and needed to transfer the prisoner to a waiting police car for the ride back to Leavenworth. Just as they were loading him into the front seat, a man appeared nearby with a Tommy gun. It was an ambush. As legend has it, someone yelled, “Let ’em have it!” and a stream of bullets pierced the police vehicle and racked the front of Union Station. When the smoke cleared, three officers and one agent were dead. Nash was killed, too. The horror of the scene was quickly telegraphed to Washington, to the FBI’s new director, a young man named J. Edgar Hoover, and made newspaper headlines coast-to-coast. Americans were horrified. The key suspect in what would be known as the Kansas City Massacre was a gangster named Pretty Boy Floyd. Decades later, it would be reported that at least three of the four killed were actually shot by friendly fire, likely from agents carrying weapons they weren’t supposed to have. But at the time, it didn’t matter. The gangsters and their shootouts were seen as an affront to common decency and civilized society.

Robert Spitzer: In the space of a few years, at least 32 states enact laws to bar or restrict civilian possession of Tommy guns and similar weapons, and pressure builds on Congress to take action.

Garrett Graff: Because of that pressure, the federal government passed national restrictions on guns for the first time in American history — what would come to be known as the National Firearms Act of 1934. The law wasn’t a ban, but it would impose a tax and registration system on anybody who wanted to buy certain weapons, including machine guns and specially defined categories of rifles and shotguns. The process was akin to getting a driver’s license or registering a car: You had to be fingerprinted and photographed, go through a background check, have your weapon registered, and pay a hefty fee — $200, the equivalent of more than $4,000 today. And the law worked. Machine guns all but disappeared from the American landscape. The gangland shootings became a thing of the past.

Robert Spitzer: The National Firearms Act of 1934 is arguably the most successful gun law enacted in America. And that kind of set a standard for things that the federal government could do to address what seemed to be the growing gun violence problem at the time.

Garrett Graff: But it set another precedent too — it was the first effort by the NRA to employ the power of its letter-writing campaigns. The original version of the law would have restricted handguns, too, which the NRA believed would make it difficult for people in rural areas with limited police to defend themselves. They mobilized their members to write letters arguing against including handguns in the law. And in the end, the legislation did just that. Machine guns would be taxed and registered, handguns would not. That tweak changed the arc of guns in America — over the decades ahead, gun violence in the U.S. becomes primarily a problem of handguns. Despite their caveat, the NRA cooperated on helping to write the law; they were willing to compromise. And what’s more, in 1934, the NRA’s president told the House Ways and Means Committee that he didn’t believe in the “general promiscuous toting of guns.” He said carrying weapons in public should be “sharply restricted and only under licenses.” And when he was asked whether he thought the 1934 law would violate the Second Amendment, he replied: “I have not given it any study from that point of view.” It’s an astounding comment, given how the NRA would evolve in the next half-century and how the Second Amendment would rise from such relative obscurity to a sacred political totem. That’s after the break.

Garrett Graff: These days, many Americans think of the Bill of Rights as something sacrosanct, a series of protections treated almost with the divine reverence of the Ten Commandments, carved into stone by our Founding Fathers. But the truth is much more chaotic. The Bill of Rights emerged out of roughly a hundred distinct amendments proposed by the states as they originally ratified the Constitution. Many of those proposals overlapped or directly contradicted each other. The Founders didn’t agree about which amendments should be included, or even that they needed a Bill of Rights at all. The right to bear arms ends up in the final Bill of Rights, but not for the reasons we think of today.

Robert Spitzer: The Second Amendment today is the fountainhead of gun rights. But the Second Amendment did not mean when it was written the meaning that has been attached to it in recent years.

Garrett Graff: It was proposed because the states were concerned about handing over too much power to the newly formed federal government — especially military power.

Robert Spitzer: The right that is described in the Second Amendment is a right of citizens to maintain firearms in the context of their service in a government-organized and regulated militia.

Garrett Graff: Militias were the primary force that the new states had for their collective defense at the time. Across the young nation, there were a lot of concerns about both who had guns and who didn’t want guns. In the original wide-ranging chaotic debate over the proposed Bill of Rights, there was almost as much attention paid to the right to not bear arms. In the North, groups like the Quakers wanted protections that ensured that they wouldn’t have to serve in the military. And in the South, there was the problem of slavery.

Robert Spitzer: In the southern states, they were frantic about slave rebellions. And their militias were extremely important in suppressing the enslaved population of their states, which was massive. In some states, nearly half the people were enslaved persons.

Garrett Graff: It all ended up with what we now call the Second Amendment, which reads: A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed. What exactly that means, though, has long been a matter of debate. For most of American history, that right to bear arms coexisted with restrictions on guns.

Robert Spitzer: Gun ownership is as old as the first European settlers who came here in the early 1600s, but so are gun laws.

Garrett Graff: Gun violence was carefully policed for centuries, first in the colonies and then later through city ordinances and state laws. In Boston, the cradle of the revolution, it was illegal to store a loaded firearm at home. Rhode Island required every gun to be registered in a house-to-house survey.

Founder Alexander Hamilton famously died in a duel, shot and killed by Aaron Burr in 1804. Though both men lived in New York, they had decided to duel in New Jersey because of gun laws, as made famous in the musical Hamilton.

[ Clip from Hamilton: (rapping) Everything is legal in New Jersey.]

Garrett Graff: In fact, both states had outlawed dueling, but New Jersey’s punishments at the time were less severe.

Robert Spitzer: In many respects, guns were more heavily regulated in our first 300 years than in the last 30 years.

Garrett Graff: Gun restrictions continued to proliferate in the 1800s, even through a chapter of American history we think of as the golden age of guns — the Wild West.

[ Clip from Gunsmoke: (narration) Around Dodge City and the territory on West, there’s just one way to handle the killers and the spoilers, and that’s with a U.S. Marshall and the smell of … gunsmoke.]