Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples

Published on May 6, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection .

Example: Hypothesis

Daily apple consumption leads to fewer doctor’s visits.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more types of variables .

- An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls.

- A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

If there are any control variables , extraneous variables , or confounding variables , be sure to jot those down as you go to minimize the chances that research bias will affect your results.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Step 1. ask a question.

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2. Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to ensure that you’re embarking on a relevant topic . This can also help you identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalize more complex constructs.

Step 3. Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

4. Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

5. Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if…then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis . The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

- H 0 : The number of lectures attended by first-year students has no effect on their final exam scores.

- H 1 : The number of lectures attended by first-year students has a positive effect on their final exam scores.

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

A hypothesis is not just a guess — it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations and statistical analysis of data).

Null and alternative hypotheses are used in statistical hypothesis testing . The null hypothesis of a test always predicts no effect or no relationship between variables, while the alternative hypothesis states your research prediction of an effect or relationship.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 11, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/hypothesis/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, construct validity | definition, types, & examples, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, operationalization | a guide with examples, pros & cons, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

The Craft of Writing a Strong Hypothesis

Table of Contents

Writing a hypothesis is one of the essential elements of a scientific research paper. It needs to be to the point, clearly communicating what your research is trying to accomplish. A blurry, drawn-out, or complexly-structured hypothesis can confuse your readers. Or worse, the editor and peer reviewers.

A captivating hypothesis is not too intricate. This blog will take you through the process so that, by the end of it, you have a better idea of how to convey your research paper's intent in just one sentence.

What is a Hypothesis?

The first step in your scientific endeavor, a hypothesis, is a strong, concise statement that forms the basis of your research. It is not the same as a thesis statement , which is a brief summary of your research paper .

The sole purpose of a hypothesis is to predict your paper's findings, data, and conclusion. It comes from a place of curiosity and intuition . When you write a hypothesis, you're essentially making an educated guess based on scientific prejudices and evidence, which is further proven or disproven through the scientific method.

The reason for undertaking research is to observe a specific phenomenon. A hypothesis, therefore, lays out what the said phenomenon is. And it does so through two variables, an independent and dependent variable.

The independent variable is the cause behind the observation, while the dependent variable is the effect of the cause. A good example of this is “mixing red and blue forms purple.” In this hypothesis, mixing red and blue is the independent variable as you're combining the two colors at your own will. The formation of purple is the dependent variable as, in this case, it is conditional to the independent variable.

Different Types of Hypotheses

Types of hypotheses

Some would stand by the notion that there are only two types of hypotheses: a Null hypothesis and an Alternative hypothesis. While that may have some truth to it, it would be better to fully distinguish the most common forms as these terms come up so often, which might leave you out of context.

Apart from Null and Alternative, there are Complex, Simple, Directional, Non-Directional, Statistical, and Associative and casual hypotheses. They don't necessarily have to be exclusive, as one hypothesis can tick many boxes, but knowing the distinctions between them will make it easier for you to construct your own.

1. Null hypothesis

A null hypothesis proposes no relationship between two variables. Denoted by H 0 , it is a negative statement like “Attending physiotherapy sessions does not affect athletes' on-field performance.” Here, the author claims physiotherapy sessions have no effect on on-field performances. Even if there is, it's only a coincidence.

2. Alternative hypothesis

Considered to be the opposite of a null hypothesis, an alternative hypothesis is donated as H1 or Ha. It explicitly states that the dependent variable affects the independent variable. A good alternative hypothesis example is “Attending physiotherapy sessions improves athletes' on-field performance.” or “Water evaporates at 100 °C. ” The alternative hypothesis further branches into directional and non-directional.

- Directional hypothesis: A hypothesis that states the result would be either positive or negative is called directional hypothesis. It accompanies H1 with either the ‘<' or ‘>' sign.

- Non-directional hypothesis: A non-directional hypothesis only claims an effect on the dependent variable. It does not clarify whether the result would be positive or negative. The sign for a non-directional hypothesis is ‘≠.'

3. Simple hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement made to reflect the relation between exactly two variables. One independent and one dependent. Consider the example, “Smoking is a prominent cause of lung cancer." The dependent variable, lung cancer, is dependent on the independent variable, smoking.

4. Complex hypothesis

In contrast to a simple hypothesis, a complex hypothesis implies the relationship between multiple independent and dependent variables. For instance, “Individuals who eat more fruits tend to have higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.” The independent variable is eating more fruits, while the dependent variables are higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.

5. Associative and casual hypothesis

Associative and casual hypotheses don't exhibit how many variables there will be. They define the relationship between the variables. In an associative hypothesis, changing any one variable, dependent or independent, affects others. In a casual hypothesis, the independent variable directly affects the dependent.

6. Empirical hypothesis

Also referred to as the working hypothesis, an empirical hypothesis claims a theory's validation via experiments and observation. This way, the statement appears justifiable and different from a wild guess.

Say, the hypothesis is “Women who take iron tablets face a lesser risk of anemia than those who take vitamin B12.” This is an example of an empirical hypothesis where the researcher the statement after assessing a group of women who take iron tablets and charting the findings.

7. Statistical hypothesis

The point of a statistical hypothesis is to test an already existing hypothesis by studying a population sample. Hypothesis like “44% of the Indian population belong in the age group of 22-27.” leverage evidence to prove or disprove a particular statement.

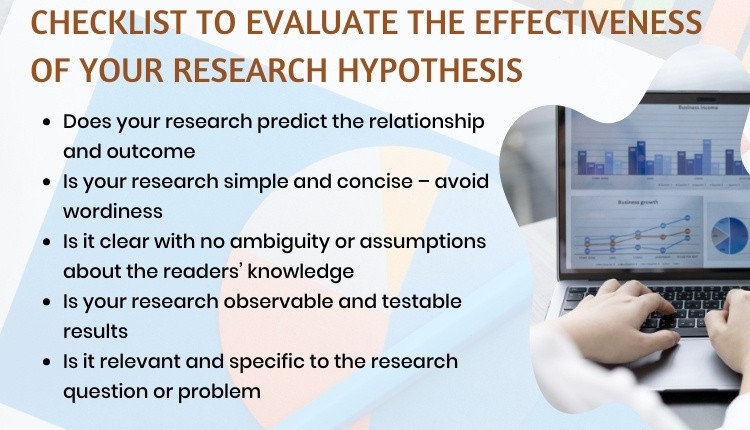

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

Writing a hypothesis is essential as it can make or break your research for you. That includes your chances of getting published in a journal. So when you're designing one, keep an eye out for these pointers:

- A research hypothesis has to be simple yet clear to look justifiable enough.

- It has to be testable — your research would be rendered pointless if too far-fetched into reality or limited by technology.

- It has to be precise about the results —what you are trying to do and achieve through it should come out in your hypothesis.

- A research hypothesis should be self-explanatory, leaving no doubt in the reader's mind.

- If you are developing a relational hypothesis, you need to include the variables and establish an appropriate relationship among them.

- A hypothesis must keep and reflect the scope for further investigations and experiments.

Separating a Hypothesis from a Prediction

Outside of academia, hypothesis and prediction are often used interchangeably. In research writing, this is not only confusing but also incorrect. And although a hypothesis and prediction are guesses at their core, there are many differences between them.

A hypothesis is an educated guess or even a testable prediction validated through research. It aims to analyze the gathered evidence and facts to define a relationship between variables and put forth a logical explanation behind the nature of events.

Predictions are assumptions or expected outcomes made without any backing evidence. They are more fictionally inclined regardless of where they originate from.

For this reason, a hypothesis holds much more weight than a prediction. It sticks to the scientific method rather than pure guesswork. "Planets revolve around the Sun." is an example of a hypothesis as it is previous knowledge and observed trends. Additionally, we can test it through the scientific method.

Whereas "COVID-19 will be eradicated by 2030." is a prediction. Even though it results from past trends, we can't prove or disprove it. So, the only way this gets validated is to wait and watch if COVID-19 cases end by 2030.

Finally, How to Write a Hypothesis

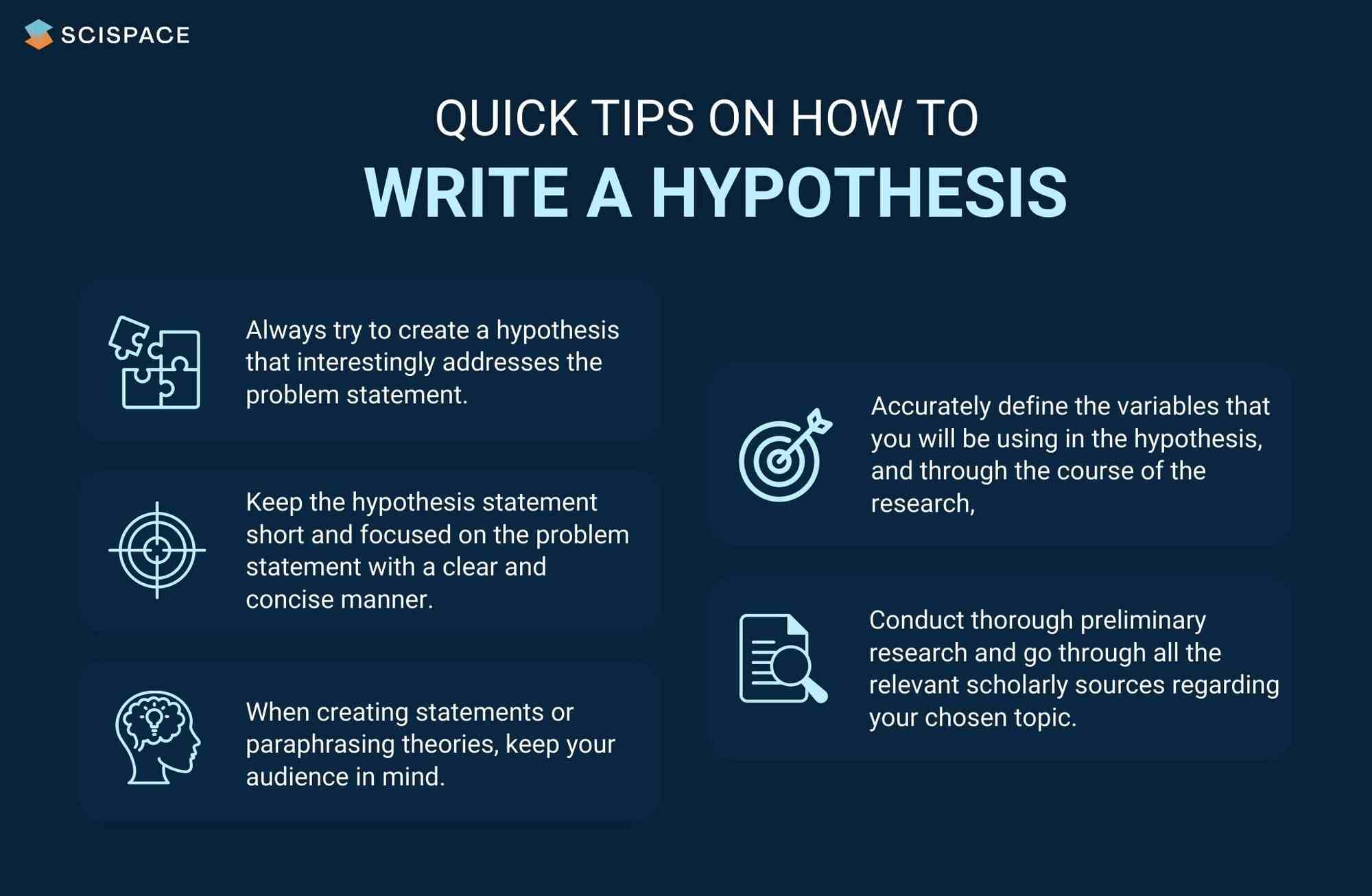

Quick tips on writing a hypothesis

1. Be clear about your research question

A hypothesis should instantly address the research question or the problem statement. To do so, you need to ask a question. Understand the constraints of your undertaken research topic and then formulate a simple and topic-centric problem. Only after that can you develop a hypothesis and further test for evidence.

2. Carry out a recce

Once you have your research's foundation laid out, it would be best to conduct preliminary research. Go through previous theories, academic papers, data, and experiments before you start curating your research hypothesis. It will give you an idea of your hypothesis's viability or originality.

Making use of references from relevant research papers helps draft a good research hypothesis. SciSpace Discover offers a repository of over 270 million research papers to browse through and gain a deeper understanding of related studies on a particular topic. Additionally, you can use SciSpace Copilot , your AI research assistant, for reading any lengthy research paper and getting a more summarized context of it. A hypothesis can be formed after evaluating many such summarized research papers. Copilot also offers explanations for theories and equations, explains paper in simplified version, allows you to highlight any text in the paper or clip math equations and tables and provides a deeper, clear understanding of what is being said. This can improve the hypothesis by helping you identify potential research gaps.

3. Create a 3-dimensional hypothesis

Variables are an essential part of any reasonable hypothesis. So, identify your independent and dependent variable(s) and form a correlation between them. The ideal way to do this is to write the hypothetical assumption in the ‘if-then' form. If you use this form, make sure that you state the predefined relationship between the variables.

In another way, you can choose to present your hypothesis as a comparison between two variables. Here, you must specify the difference you expect to observe in the results.

4. Write the first draft

Now that everything is in place, it's time to write your hypothesis. For starters, create the first draft. In this version, write what you expect to find from your research.

Clearly separate your independent and dependent variables and the link between them. Don't fixate on syntax at this stage. The goal is to ensure your hypothesis addresses the issue.

5. Proof your hypothesis

After preparing the first draft of your hypothesis, you need to inspect it thoroughly. It should tick all the boxes, like being concise, straightforward, relevant, and accurate. Your final hypothesis has to be well-structured as well.

Research projects are an exciting and crucial part of being a scholar. And once you have your research question, you need a great hypothesis to begin conducting research. Thus, knowing how to write a hypothesis is very important.

Now that you have a firmer grasp on what a good hypothesis constitutes, the different kinds there are, and what process to follow, you will find it much easier to write your hypothesis, which ultimately helps your research.

Now it's easier than ever to streamline your research workflow with SciSpace Discover . Its integrated, comprehensive end-to-end platform for research allows scholars to easily discover, write and publish their research and fosters collaboration.

It includes everything you need, including a repository of over 270 million research papers across disciplines, SEO-optimized summaries and public profiles to show your expertise and experience.

If you found these tips on writing a research hypothesis useful, head over to our blog on Statistical Hypothesis Testing to learn about the top researchers, papers, and institutions in this domain.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. what is the definition of hypothesis.

According to the Oxford dictionary, a hypothesis is defined as “An idea or explanation of something that is based on a few known facts, but that has not yet been proved to be true or correct”.

2. What is an example of hypothesis?

The hypothesis is a statement that proposes a relationship between two or more variables. An example: "If we increase the number of new users who join our platform by 25%, then we will see an increase in revenue."

3. What is an example of null hypothesis?

A null hypothesis is a statement that there is no relationship between two variables. The null hypothesis is written as H0. The null hypothesis states that there is no effect. For example, if you're studying whether or not a particular type of exercise increases strength, your null hypothesis will be "there is no difference in strength between people who exercise and people who don't."

4. What are the types of research?

• Fundamental research

• Applied research

• Qualitative research

• Quantitative research

• Mixed research

• Exploratory research

• Longitudinal research

• Cross-sectional research

• Field research

• Laboratory research

• Fixed research

• Flexible research

• Action research

• Policy research

• Classification research

• Comparative research

• Causal research

• Inductive research

• Deductive research

5. How to write a hypothesis?

• Your hypothesis should be able to predict the relationship and outcome.

• Avoid wordiness by keeping it simple and brief.

• Your hypothesis should contain observable and testable outcomes.

• Your hypothesis should be relevant to the research question.

6. What are the 2 types of hypothesis?

• Null hypotheses are used to test the claim that "there is no difference between two groups of data".

• Alternative hypotheses test the claim that "there is a difference between two data groups".

7. Difference between research question and research hypothesis?

A research question is a broad, open-ended question you will try to answer through your research. A hypothesis is a statement based on prior research or theory that you expect to be true due to your study. Example - Research question: What are the factors that influence the adoption of the new technology? Research hypothesis: There is a positive relationship between age, education and income level with the adoption of the new technology.

8. What is plural for hypothesis?

The plural of hypothesis is hypotheses. Here's an example of how it would be used in a statement, "Numerous well-considered hypotheses are presented in this part, and they are supported by tables and figures that are well-illustrated."

9. What is the red queen hypothesis?

The red queen hypothesis in evolutionary biology states that species must constantly evolve to avoid extinction because if they don't, they will be outcompeted by other species that are evolving. Leigh Van Valen first proposed it in 1973; since then, it has been tested and substantiated many times.

10. Who is known as the father of null hypothesis?

The father of the null hypothesis is Sir Ronald Fisher. He published a paper in 1925 that introduced the concept of null hypothesis testing, and he was also the first to use the term itself.

11. When to reject null hypothesis?

You need to find a significant difference between your two populations to reject the null hypothesis. You can determine that by running statistical tests such as an independent sample t-test or a dependent sample t-test. You should reject the null hypothesis if the p-value is less than 0.05.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Format, Examples, and Tips

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis, operational definitions, types of hypotheses, hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

Frequently Asked Questions

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study.

One hypothesis example would be a study designed to look at the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance might have a hypothesis that states: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. It is only at this point that researchers begin to develop a testable hypothesis. Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore a number of factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk wisdom that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in a number of different ways. One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. How would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

In order to measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming other people. In this situation, the researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests that there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent variables and a dependent variable.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative sample of the population and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- Complex hypothesis: "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have scores different than students who do not receive the intervention."

- "There will be no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will perform better than students who did not receive the intervention."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when it would be impossible or difficult to conduct an experiment . These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can then be used to look at how the variables are related. This type of research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

A Word From Verywell

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Some examples of how to write a hypothesis include:

- "Staying up late will lead to worse test performance the next day."

- "People who consume one apple each day will visit the doctor fewer times each year."

- "Breaking study sessions up into three 20-minute sessions will lead to better test results than a single 60-minute study session."

The four parts of a hypothesis are:

- The research question

- The independent variable (IV)

- The dependent variable (DV)

- The proposed relationship between the IV and DV

Castillo M. The scientific method: a need for something better? . AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34(9):1669-71. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A3401

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

What Is A Research (Scientific) Hypothesis? A plain-language explainer + examples

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

If you’re new to the world of research, or it’s your first time writing a dissertation or thesis, you’re probably noticing that the words “research hypothesis” and “scientific hypothesis” are used quite a bit, and you’re wondering what they mean in a research context .

“Hypothesis” is one of those words that people use loosely, thinking they understand what it means. However, it has a very specific meaning within academic research. So, it’s important to understand the exact meaning before you start hypothesizing.

Research Hypothesis 101

- What is a hypothesis ?

- What is a research hypothesis (scientific hypothesis)?

- Requirements for a research hypothesis

- Definition of a research hypothesis

- The null hypothesis

What is a hypothesis?

Let’s start with the general definition of a hypothesis (not a research hypothesis or scientific hypothesis), according to the Cambridge Dictionary:

Hypothesis: an idea or explanation for something that is based on known facts but has not yet been proved.

In other words, it’s a statement that provides an explanation for why or how something works, based on facts (or some reasonable assumptions), but that has not yet been specifically tested . For example, a hypothesis might look something like this:

Hypothesis: sleep impacts academic performance.

This statement predicts that academic performance will be influenced by the amount and/or quality of sleep a student engages in – sounds reasonable, right? It’s based on reasonable assumptions , underpinned by what we currently know about sleep and health (from the existing literature). So, loosely speaking, we could call it a hypothesis, at least by the dictionary definition.

But that’s not good enough…

Unfortunately, that’s not quite sophisticated enough to describe a research hypothesis (also sometimes called a scientific hypothesis), and it wouldn’t be acceptable in a dissertation, thesis or research paper . In the world of academic research, a statement needs a few more criteria to constitute a true research hypothesis .

What is a research hypothesis?

A research hypothesis (also called a scientific hypothesis) is a statement about the expected outcome of a study (for example, a dissertation or thesis). To constitute a quality hypothesis, the statement needs to have three attributes – specificity , clarity and testability .

Let’s take a look at these more closely.

Need a helping hand?

Hypothesis Essential #1: Specificity & Clarity

A good research hypothesis needs to be extremely clear and articulate about both what’ s being assessed (who or what variables are involved ) and the expected outcome (for example, a difference between groups, a relationship between variables, etc.).

Let’s stick with our sleepy students example and look at how this statement could be more specific and clear.

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

As you can see, the statement is very specific as it identifies the variables involved (sleep hours and test grades), the parties involved (two groups of students), as well as the predicted relationship type (a positive relationship). There’s no ambiguity or uncertainty about who or what is involved in the statement, and the expected outcome is clear.

Contrast that to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – and you can see the difference. “Sleep” and “academic performance” are both comparatively vague , and there’s no indication of what the expected relationship direction is (more sleep or less sleep). As you can see, specificity and clarity are key.

Hypothesis Essential #2: Testability (Provability)

A statement must be testable to qualify as a research hypothesis. In other words, there needs to be a way to prove (or disprove) the statement. If it’s not testable, it’s not a hypothesis – simple as that.

For example, consider the hypothesis we mentioned earlier:

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

We could test this statement by undertaking a quantitative study involving two groups of students, one that gets 8 or more hours of sleep per night for a fixed period, and one that gets less. We could then compare the standardised test results for both groups to see if there’s a statistically significant difference.

Again, if you compare this to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – you can see that it would be quite difficult to test that statement, primarily because it isn’t specific enough. How much sleep? By who? What type of academic performance?

So, remember the mantra – if you can’t test it, it’s not a hypothesis 🙂

Defining A Research Hypothesis

You’re still with us? Great! Let’s recap and pin down a clear definition of a hypothesis.

A research hypothesis (or scientific hypothesis) is a statement about an expected relationship between variables, or explanation of an occurrence, that is clear, specific and testable.

So, when you write up hypotheses for your dissertation or thesis, make sure that they meet all these criteria. If you do, you’ll not only have rock-solid hypotheses but you’ll also ensure a clear focus for your entire research project.

What about the null hypothesis?

You may have also heard the terms null hypothesis , alternative hypothesis, or H-zero thrown around. At a simple level, the null hypothesis is the counter-proposal to the original hypothesis.

For example, if the hypothesis predicts that there is a relationship between two variables (for example, sleep and academic performance), the null hypothesis would predict that there is no relationship between those variables.

At a more technical level, the null hypothesis proposes that no statistical significance exists in a set of given observations and that any differences are due to chance alone.

And there you have it – hypotheses in a nutshell.

If you have any questions, be sure to leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to help you. If you need hands-on help developing and testing your hypotheses, consider our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the research journey.

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

You Might Also Like:

16 Comments

Very useful information. I benefit more from getting more information in this regard.

Very great insight,educative and informative. Please give meet deep critics on many research data of public international Law like human rights, environment, natural resources, law of the sea etc

In a book I read a distinction is made between null, research, and alternative hypothesis. As far as I understand, alternative and research hypotheses are the same. Can you please elaborate? Best Afshin

This is a self explanatory, easy going site. I will recommend this to my friends and colleagues.

Very good definition. How can I cite your definition in my thesis? Thank you. Is nul hypothesis compulsory in a research?

It’s a counter-proposal to be proven as a rejection

Please what is the difference between alternate hypothesis and research hypothesis?

It is a very good explanation. However, it limits hypotheses to statistically tasteable ideas. What about for qualitative researches or other researches that involve quantitative data that don’t need statistical tests?

In qualitative research, one typically uses propositions, not hypotheses.

could you please elaborate it more

I’ve benefited greatly from these notes, thank you.

This is very helpful

well articulated ideas are presented here, thank you for being reliable sources of information

Excellent. Thanks for being clear and sound about the research methodology and hypothesis (quantitative research)

I have only a simple question regarding the null hypothesis. – Is the null hypothesis (Ho) known as the reversible hypothesis of the alternative hypothesis (H1? – How to test it in academic research?

this is very important note help me much more

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- What Is Research Methodology? Simple Definition (With Examples) - Grad Coach - […] Contrasted to this, a quantitative methodology is typically used when the research aims and objectives are confirmatory in nature. For example,…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes .

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more variables . An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls. A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Step 1: ask a question.

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2: Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalise more complex constructs.

Step 3: Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

Step 4: Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

Step 5: Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if … then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

Step 6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

A hypothesis is not just a guess. It should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (‘ x affects y because …’).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses. In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, May 06). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 9 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/hypothesis-writing/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, operationalisation | a guide with examples, pros & cons, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples.

Research Hypothesis In Psychology: Types, & Examples

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

A research hypothesis, in its plural form “hypotheses,” is a specific, testable prediction about the anticipated results of a study, established at its outset. It is a key component of the scientific method .

Hypotheses connect theory to data and guide the research process towards expanding scientific understanding

Some key points about hypotheses:

- A hypothesis expresses an expected pattern or relationship. It connects the variables under investigation.

- It is stated in clear, precise terms before any data collection or analysis occurs. This makes the hypothesis testable.

- A hypothesis must be falsifiable. It should be possible, even if unlikely in practice, to collect data that disconfirms rather than supports the hypothesis.

- Hypotheses guide research. Scientists design studies to explicitly evaluate hypotheses about how nature works.

- For a hypothesis to be valid, it must be testable against empirical evidence. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

- Hypotheses are informed by background knowledge and observation, but go beyond what is already known to propose an explanation of how or why something occurs.

Predictions typically arise from a thorough knowledge of the research literature, curiosity about real-world problems or implications, and integrating this to advance theory. They build on existing literature while providing new insight.

Types of Research Hypotheses

Alternative hypothesis.

The research hypothesis is often called the alternative or experimental hypothesis in experimental research.

It typically suggests a potential relationship between two key variables: the independent variable, which the researcher manipulates, and the dependent variable, which is measured based on those changes.

The alternative hypothesis states a relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable affects the other).

A hypothesis is a testable statement or prediction about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a key component of the scientific method. Some key points about hypotheses:

- Important hypotheses lead to predictions that can be tested empirically. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

In summary, a hypothesis is a precise, testable statement of what researchers expect to happen in a study and why. Hypotheses connect theory to data and guide the research process towards expanding scientific understanding.

An experimental hypothesis predicts what change(s) will occur in the dependent variable when the independent variable is manipulated.

It states that the results are not due to chance and are significant in supporting the theory being investigated.

The alternative hypothesis can be directional, indicating a specific direction of the effect, or non-directional, suggesting a difference without specifying its nature. It’s what researchers aim to support or demonstrate through their study.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis states no relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable does not affect the other). There will be no changes in the dependent variable due to manipulating the independent variable.

It states results are due to chance and are not significant in supporting the idea being investigated.

The null hypothesis, positing no effect or relationship, is a foundational contrast to the research hypothesis in scientific inquiry. It establishes a baseline for statistical testing, promoting objectivity by initiating research from a neutral stance.

Many statistical methods are tailored to test the null hypothesis, determining the likelihood of observed results if no true effect exists.

This dual-hypothesis approach provides clarity, ensuring that research intentions are explicit, and fosters consistency across scientific studies, enhancing the standardization and interpretability of research outcomes.

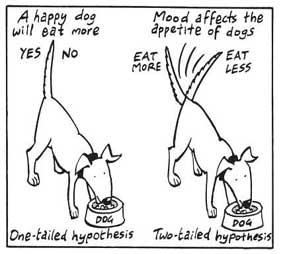

Nondirectional Hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis, also known as a two-tailed hypothesis, predicts that there is a difference or relationship between two variables but does not specify the direction of this relationship.

It merely indicates that a change or effect will occur without predicting which group will have higher or lower values.

For example, “There is a difference in performance between Group A and Group B” is a non-directional hypothesis.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional (one-tailed) hypothesis predicts the nature of the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. It predicts in which direction the change will take place. (i.e., greater, smaller, less, more)

It specifies whether one variable is greater, lesser, or different from another, rather than just indicating that there’s a difference without specifying its nature.

For example, “Exercise increases weight loss” is a directional hypothesis.

Falsifiability

The Falsification Principle, proposed by Karl Popper , is a way of demarcating science from non-science. It suggests that for a theory or hypothesis to be considered scientific, it must be testable and irrefutable.

Falsifiability emphasizes that scientific claims shouldn’t just be confirmable but should also have the potential to be proven wrong.

It means that there should exist some potential evidence or experiment that could prove the proposition false.

However many confirming instances exist for a theory, it only takes one counter observation to falsify it. For example, the hypothesis that “all swans are white,” can be falsified by observing a black swan.

For Popper, science should attempt to disprove a theory rather than attempt to continually provide evidence to support a research hypothesis.

Can a Hypothesis be Proven?

Hypotheses make probabilistic predictions. They state the expected outcome if a particular relationship exists. However, a study result supporting a hypothesis does not definitively prove it is true.

All studies have limitations. There may be unknown confounding factors or issues that limit the certainty of conclusions. Additional studies may yield different results.

In science, hypotheses can realistically only be supported with some degree of confidence, not proven. The process of science is to incrementally accumulate evidence for and against hypothesized relationships in an ongoing pursuit of better models and explanations that best fit the empirical data. But hypotheses remain open to revision and rejection if that is where the evidence leads.

- Disproving a hypothesis is definitive. Solid disconfirmatory evidence will falsify a hypothesis and require altering or discarding it based on the evidence.

- However, confirming evidence is always open to revision. Other explanations may account for the same results, and additional or contradictory evidence may emerge over time.

We can never 100% prove the alternative hypothesis. Instead, we see if we can disprove, or reject the null hypothesis.

If we reject the null hypothesis, this doesn’t mean that our alternative hypothesis is correct but does support the alternative/experimental hypothesis.

Upon analysis of the results, an alternative hypothesis can be rejected or supported, but it can never be proven to be correct. We must avoid any reference to results proving a theory as this implies 100% certainty, and there is always a chance that evidence may exist which could refute a theory.

How to Write a Hypothesis

- Identify variables . The researcher manipulates the independent variable and the dependent variable is the measured outcome.

- Operationalized the variables being investigated . Operationalization of a hypothesis refers to the process of making the variables physically measurable or testable, e.g. if you are about to study aggression, you might count the number of punches given by participants.

- Decide on a direction for your prediction . If there is evidence in the literature to support a specific effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, write a directional (one-tailed) hypothesis. If there are limited or ambiguous findings in the literature regarding the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, write a non-directional (two-tailed) hypothesis.

- Make it Testable : Ensure your hypothesis can be tested through experimentation or observation. It should be possible to prove it false (principle of falsifiability).

- Clear & concise language . A strong hypothesis is concise (typically one to two sentences long), and formulated using clear and straightforward language, ensuring it’s easily understood and testable.

Consider a hypothesis many teachers might subscribe to: students work better on Monday morning than on Friday afternoon (IV=Day, DV= Standard of work).

Now, if we decide to study this by giving the same group of students a lesson on a Monday morning and a Friday afternoon and then measuring their immediate recall of the material covered in each session, we would end up with the following:

- The alternative hypothesis states that students will recall significantly more information on a Monday morning than on a Friday afternoon.

- The null hypothesis states that there will be no significant difference in the amount recalled on a Monday morning compared to a Friday afternoon. Any difference will be due to chance or confounding factors.

More Examples

- Memory : Participants exposed to classical music during study sessions will recall more items from a list than those who studied in silence.

- Social Psychology : Individuals who frequently engage in social media use will report higher levels of perceived social isolation compared to those who use it infrequently.

- Developmental Psychology : Children who engage in regular imaginative play have better problem-solving skills than those who don’t.

- Clinical Psychology : Cognitive-behavioral therapy will be more effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety over a 6-month period compared to traditional talk therapy.

- Cognitive Psychology : Individuals who multitask between various electronic devices will have shorter attention spans on focused tasks than those who single-task.

- Health Psychology : Patients who practice mindfulness meditation will experience lower levels of chronic pain compared to those who don’t meditate.

- Organizational Psychology : Employees in open-plan offices will report higher levels of stress than those in private offices.

- Behavioral Psychology : Rats rewarded with food after pressing a lever will press it more frequently than rats who receive no reward.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Research Hypothesis: What It Is, Types + How to Develop?

A research study starts with a question. Researchers worldwide ask questions and create research hypotheses. The effectiveness of research relies on developing a good research hypothesis. Examples of research hypotheses can guide researchers in writing effective ones.

In this blog, we’ll learn what a research hypothesis is, why it’s important in research, and the different types used in science. We’ll also guide you through creating your research hypothesis and discussing ways to test and evaluate it.

What is a Research Hypothesis?

A hypothesis is like a guess or idea that you suggest to check if it’s true. A research hypothesis is a statement that brings up a question and predicts what might happen.

It’s really important in the scientific method and is used in experiments to figure things out. Essentially, it’s an educated guess about how things are connected in the research.

A research hypothesis usually includes pointing out the independent variable (the thing they’re changing or studying) and the dependent variable (the result they’re measuring or watching). It helps plan how to gather and analyze data to see if there’s evidence to support or deny the expected connection between these variables.

Importance of Hypothesis in Research

Hypotheses are really important in research. They help design studies, allow for practical testing, and add to our scientific knowledge. Their main role is to organize research projects, making them purposeful, focused, and valuable to the scientific community. Let’s look at some key reasons why they matter:

- A research hypothesis helps test theories.

A hypothesis plays a pivotal role in the scientific method by providing a basis for testing existing theories. For example, a hypothesis might test the predictive power of a psychological theory on human behavior.

- It serves as a great platform for investigation activities.

It serves as a launching pad for investigation activities, which offers researchers a clear starting point. A research hypothesis can explore the relationship between exercise and stress reduction.

- Hypothesis guides the research work or study.

A well-formulated hypothesis guides the entire research process. It ensures that the study remains focused and purposeful. For instance, a hypothesis about the impact of social media on interpersonal relationships provides clear guidance for a study.

- Hypothesis sometimes suggests theories.

In some cases, a hypothesis can suggest new theories or modifications to existing ones. For example, a hypothesis testing the effectiveness of a new drug might prompt a reconsideration of current medical theories.

- It helps in knowing the data needs.

A hypothesis clarifies the data requirements for a study, ensuring that researchers collect the necessary information—a hypothesis guiding the collection of demographic data to analyze the influence of age on a particular phenomenon.

- The hypothesis explains social phenomena.

Hypotheses are instrumental in explaining complex social phenomena. For instance, a hypothesis might explore the relationship between economic factors and crime rates in a given community.

- Hypothesis provides a relationship between phenomena for empirical Testing.

Hypotheses establish clear relationships between phenomena, paving the way for empirical testing. An example could be a hypothesis exploring the correlation between sleep patterns and academic performance.

- It helps in knowing the most suitable analysis technique.

A hypothesis guides researchers in selecting the most appropriate analysis techniques for their data. For example, a hypothesis focusing on the effectiveness of a teaching method may lead to the choice of statistical analyses best suited for educational research.

Characteristics of a Good Research Hypothesis

A hypothesis is a specific idea that you can test in a study. It often comes from looking at past research and theories. A good hypothesis usually starts with a research question that you can explore through background research. For it to be effective, consider these key characteristics:

- Clear and Focused Language: A good hypothesis uses clear and focused language to avoid confusion and ensure everyone understands it.

- Related to the Research Topic: The hypothesis should directly relate to the research topic, acting as a bridge between the specific question and the broader study.

- Testable: An effective hypothesis can be tested, meaning its prediction can be checked with real data to support or challenge the proposed relationship.

- Potential for Exploration: A good hypothesis often comes from a research question that invites further exploration. Doing background research helps find gaps and potential areas to investigate.

- Includes Variables: The hypothesis should clearly state both the independent and dependent variables, specifying the factors being studied and the expected outcomes.

- Ethical Considerations: Check if variables can be manipulated without breaking ethical standards. It’s crucial to maintain ethical research practices.

- Predicts Outcomes: The hypothesis should predict the expected relationship and outcome, acting as a roadmap for the study and guiding data collection and analysis.

- Simple and Concise: A good hypothesis avoids unnecessary complexity and is simple and concise, expressing the essence of the proposed relationship clearly.

- Clear and Assumption-Free: The hypothesis should be clear and free from assumptions about the reader’s prior knowledge, ensuring universal understanding.

- Observable and Testable Results: A strong hypothesis implies research that produces observable and testable results, making sure the study’s outcomes can be effectively measured and analyzed.

When you use these characteristics as a checklist, it can help you create a good research hypothesis. It’ll guide improving and strengthening the hypothesis, identifying any weaknesses, and making necessary changes. Crafting a hypothesis with these features helps you conduct a thorough and insightful research study.

Types of Research Hypotheses

The research hypothesis comes in various types, each serving a specific purpose in guiding the scientific investigation. Knowing the differences will make it easier for you to create your own hypothesis. Here’s an overview of the common types:

01. Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis states that there is no connection between two considered variables or that two groups are unrelated. As discussed earlier, a hypothesis is an unproven assumption lacking sufficient supporting data. It serves as the statement researchers aim to disprove. It is testable, verifiable, and can be rejected.

For example, if you’re studying the relationship between Project A and Project B, assuming both projects are of equal standard is your null hypothesis. It needs to be specific for your study.

02. Alternative Hypothesis

The alternative hypothesis is basically another option to the null hypothesis. It involves looking for a significant change or alternative that could lead you to reject the null hypothesis. It’s a different idea compared to the null hypothesis.

When you create a null hypothesis, you’re making an educated guess about whether something is true or if there’s a connection between that thing and another variable. If the null view suggests something is correct, the alternative hypothesis says it’s incorrect.

For instance, if your null hypothesis is “I’m going to be $1000 richer,” the alternative hypothesis would be “I’m not going to get $1000 or be richer.”

03. Directional Hypothesis

The directional hypothesis predicts the direction of the relationship between independent and dependent variables. They specify whether the effect will be positive or negative.

If you increase your study hours, you will experience a positive association with your exam scores. This hypothesis suggests that as you increase the independent variable (study hours), there will also be an increase in the dependent variable (exam scores).

04. Non-directional Hypothesis

The non-directional hypothesis predicts the existence of a relationship between variables but does not specify the direction of the effect. It suggests that there will be a significant difference or relationship, but it does not predict the nature of that difference.

For example, you will find no notable difference in test scores between students who receive the educational intervention and those who do not. However, once you compare the test scores of the two groups, you will notice an important difference.

05. Simple Hypothesis

A simple hypothesis predicts a relationship between one dependent variable and one independent variable without specifying the nature of that relationship. It’s simple and usually used when we don’t know much about how the two things are connected.

For example, if you adopt effective study habits, you will achieve higher exam scores than those with poor study habits.

06. Complex Hypothesis

A complex hypothesis is an idea that specifies a relationship between multiple independent and dependent variables. It is a more detailed idea than a simple hypothesis.

While a simple view suggests a straightforward cause-and-effect relationship between two things, a complex hypothesis involves many factors and how they’re connected to each other.

For example, when you increase your study time, you tend to achieve higher exam scores. The connection between your study time and exam performance is affected by various factors, including the quality of your sleep, your motivation levels, and the effectiveness of your study techniques.

If you sleep well, stay highly motivated, and use effective study strategies, you may observe a more robust positive correlation between the time you spend studying and your exam scores, unlike those who may lack these factors.

07. Associative Hypothesis

An associative hypothesis proposes a connection between two things without saying that one causes the other. Basically, it suggests that when one thing changes, the other changes too, but it doesn’t claim that one thing is causing the change in the other.

For example, you will likely notice higher exam scores when you increase your study time. You can recognize an association between your study time and exam scores in this scenario.

Your hypothesis acknowledges a relationship between the two variables—your study time and exam scores—without asserting that increased study time directly causes higher exam scores. You need to consider that other factors, like motivation or learning style, could affect the observed association.

08. Causal Hypothesis

A causal hypothesis proposes a cause-and-effect relationship between two variables. It suggests that changes in one variable directly cause changes in another variable.

For example, when you increase your study time, you experience higher exam scores. This hypothesis suggests a direct cause-and-effect relationship, indicating that the more time you spend studying, the higher your exam scores. It assumes that changes in your study time directly influence changes in your exam performance.

09. Empirical Hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is a statement based on things we can see and measure. It comes from direct observation or experiments and can be tested with real-world evidence. If an experiment proves a theory, it supports the idea and shows it’s not just a guess. This makes the statement more reliable than a wild guess.

For example, if you increase the dosage of a certain medication, you might observe a quicker recovery time for patients. Imagine you’re in charge of a clinical trial. In this trial, patients are given varying dosages of the medication, and you measure and compare their recovery times. This allows you to directly see the effects of different dosages on how fast patients recover.

This way, you can create a research hypothesis: “Increasing the dosage of a certain medication will lead to a faster recovery time for patients.”

10. Statistical Hypothesis

A statistical hypothesis is a statement or assumption about a population parameter that is the subject of an investigation. It serves as the basis for statistical analysis and testing. It is often tested using statistical methods to draw inferences about the larger population.

In a hypothesis test, statistical evidence is collected to either reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis or fail to reject the null hypothesis due to insufficient evidence.

For example, let’s say you’re testing a new medicine. Your hypothesis could be that the medicine doesn’t really help patients get better. So, you collect data and use statistics to see if your guess is right or if the medicine actually makes a difference.

If the data strongly shows that the medicine does help, you say your guess was wrong, and the medicine does make a difference. But if the proof isn’t strong enough, you can stick with your original guess because you didn’t get enough evidence to change your mind.

How to Develop a Research Hypotheses?

Step 1: identify your research problem or topic..

Define the area of interest or the problem you want to investigate. Make sure it’s clear and well-defined.

Start by asking a question about your chosen topic. Consider the limitations of your research and create a straightforward problem related to your topic. Once you’ve done that, you can develop and test a hypothesis with evidence.

Step 2: Conduct a literature review

Review existing literature related to your research problem. This will help you understand the current state of knowledge in the field, identify gaps, and build a foundation for your hypothesis. Consider the following questions:

- What existing research has been conducted on your chosen topic?

- Are there any gaps or unanswered questions in the current literature?

- How will the existing literature contribute to the foundation of your research?

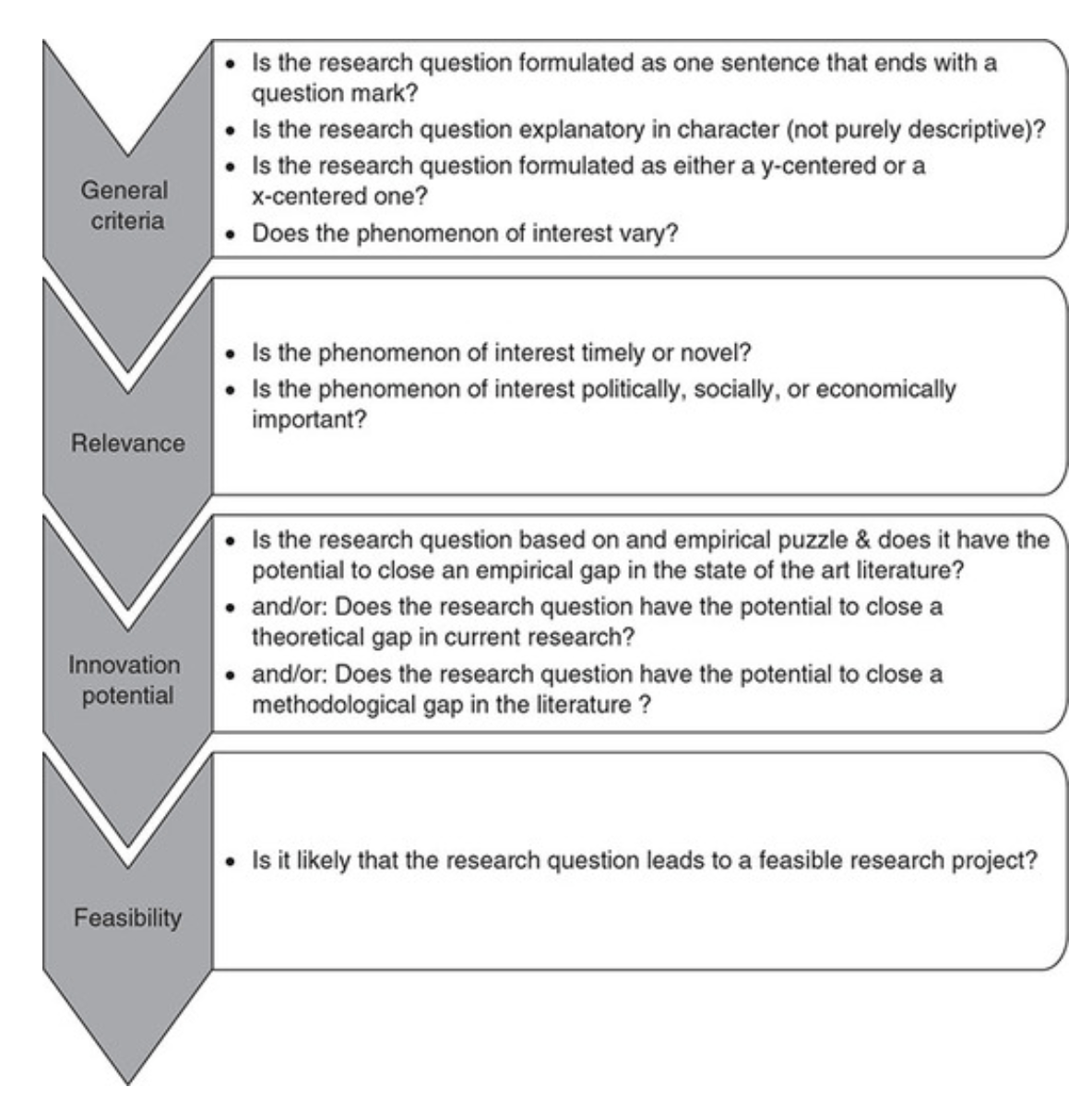

Step 3: Formulate your research question

Based on your literature review, create a specific and concise research question that addresses your identified problem. Your research question should be clear, focused, and relevant to your field of study.

Step 4: Identify variables

Determine the key variables involved in your research question. Variables are the factors or phenomena that you will study and manipulate to test your hypothesis.

- Independent Variable: The variable you manipulate or control.

- Dependent Variable: The variable you measure to observe the effect of the independent variable.

Step 5: State the Null hypothesis

The null hypothesis is a statement that there is no significant difference or effect. It serves as a baseline for comparison with the alternative hypothesis.

Step 6: Select appropriate methods for testing the hypothesis

Choose research methods that align with your study objectives, such as experiments, surveys, or observational studies. The selected methods enable you to test your research hypothesis effectively.

Creating a research hypothesis usually takes more than one try. Expect to make changes as you collect data. It’s normal to test and say no to a few hypotheses before you find the right answer to your research question.

Testing and Evaluating Hypotheses

Testing hypotheses is a really important part of research. It’s like the practical side of things. Here, real-world evidence will help you determine how different things are connected. Let’s explore the main steps in hypothesis testing:

- State your research hypothesis.