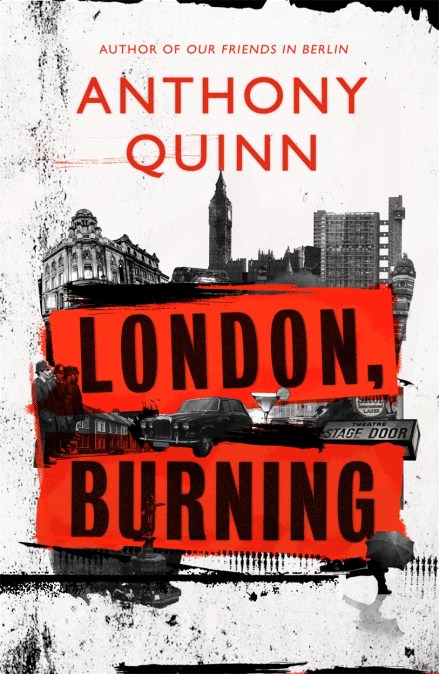

London, Burning: ‘A page-turning delight’

For his eighth novel, Anthony Quinn continues his noble tradition of producing a thumping good read

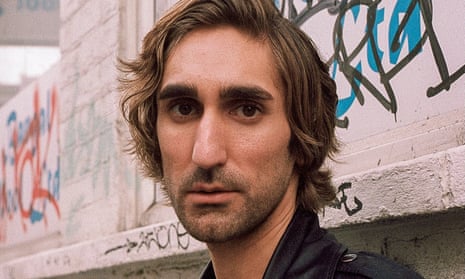

T he publicity blurb for the film critic-turned-novelist Anthony Quinn’s new book — his eighth novel — describes him as “one of Britain’s finest contemporary writers”. This may come as a surprise to many, not because of any dearth of talent on Quinn’s part but because he has somewhat flown under the radar during his career. This is despite winning numerous awards, including the Authors’ Club award for Best First Novel for his 2009 first novel The Rescue Man, and his biggest success to date, 2015’s Curtain Call, has been adapted for film by none other than Patrick Marber, featuring a starry cast including Gemma Arterton, Colin Firth, and in the role of Jimmy Erskine, a lightly fictionalised version of the theatre critic James Agate, Simon Russell Beale.

Quinn’s novels all follow a relatively similar trajectory. They are all set in a specific historic period, ranging from the Victoria era ( The Streets) to London, Burning ’s keenly evoked depiction of the late Seventies, when Britain was a country of uncollected rubbish and the tail end of the Callaghan government, with the IRA striking fear into the nation. Many of them feature real-life characters barely disguised for creative purposes, such as the theatre critic Kenneth Tynan appearing as Nat Fane in Freya and Eureka or, here, the director Peter Hall being lightly guyed as the priapic gourmand Freddie Selves, in charge of the National Music Hall as he juggles responsibilities professional and personal.

And all of them, without exception, are that rarest and most unfashionable of things, a thumping good read. His new book carries on that noble tradition.

London, Burning is Quinn’s first novel for Little, Brown — the others were published by Jonathan Cape — but a change of publisher has done nothing to change his modus operandi. It focuses on four major characters including the aforementioned Selves; Vicky Tress, a policewoman who finds herself mired within a corruption scandal in the Met; Hannah Strode, a reporter on a paper not a million miles away from The Independent; and Callum Conlan, a Northern Irish academic who is regarded with faint suspicion because of his accent and background. Over the course of the novel, the characters interact with one another in both predictable and unexpected ways, as terrorist bombings, thwarted and otherwise, punctuate the narrative to explosive effect.

Quinn is a witty and erudite writer who manages to make his characters’ dialogue sound natural and engaging

If Quinn should be compared to any other novelist, William Boyd is a fair point of comparison. Like Boyd, Quinn is a witty and erudite writer who manages to make his characters’ dialogue sound natural and engaging, and whose literary name-dropping (the first paragraph of the second chapter contains two separate — and entirely appropriate — allusions to Philip Larkin) exemplifies the slight artificiality of the worlds that he creates. Quinn’s years spent as a film critic can be discerned from the cinematic sweep of his narratives and the speed with which he establishes his mise-en-scène; if you’re not gripped within the first ten or so pages, then you haven’t been paying attention.

This isn’t to say that London, Burning is a flawless novel. The storyline involving PC Tress is full of vivid and interesting details (I never knew that “plonk” was slang for a WPC) but it suffers from a sense of over-familiarity. I cannot be the only reader who is weary of tales of institutional corruption in the Met, even down to the character of a loquacious grass who helpfully dispenses plot-advancing titbits at the appropriate moment. It is also resolved in a frustratingly open-ended fashion, hinting at a follow-up novel if this one is a success. Some of Tress’s actions and motivations later in the book seem to stretch credibility, although it would be unfair to hint at why. And at least one major development in the book seemed slightly pat and convenient, hinging on a dramatic device — the writing of a letter by a high-ranking politician — that would have been seen as old hat as far back as the Victorian novelists that Quinn clearly reveres.

The title might seem to suggest a fierier conflagration than eventually takes place, but Quinn’s book is a page-turning delight

Yet such objections are ultimately niggling and somewhat mean-spirited when set against the novel’s greater achievements. Just as Erskine ends up dominating Curtain Call entirely — it’s nominally a murder mystery but it becomes a wonderful character study — so Selves is undoubtedly the most flamboyantly enjoyable figure depicted here. Anyone who has read Peter Hall’s Diaries, which depict his time running the National Theatre while dealing with union strikes, grumpy journalists and unreliable thespians, will relish his alter ego’s portrayal. Quinn sensibly borrows some of the most engaging stories about the real-life Hall, such as his ill-considered but lucrative decision to appear in an advert for Sanderson wallpaper, and places them in a highly entertaining dramatic context. Yet crucially, Selves remains a likeable and engaging character, despite his frequently dreadful behaviour, meaning that the reader sympathises with, rather than despairs at, his antics.

There are numerously beautifully drawn set-pieces throughout, ranging from an unintentional blind date to a High Tory New Year’s Eve party in the country, featuring an irritating party animal known as “Banger”. If Quinn flirts with tastelessness by depicting the late Airey Neave as a character called Anthony Middleton, a hardline hanger and flogger who sees the conflict with the Irish as an almost religious exercise in crusade, then this pays off splendidly in a well-observed and tense scene at a first-night party at the National Music Hall, showing the pervasive fear that Londoners felt at all times with the prospect of bombings and terrorism.

The title might seem to suggest a fierier conflagration than eventually takes place, but Quinn’s book is a page-turning delight. I can pay it no higher compliment than to say that, when I finished reading it, I felt almost sad that I was not going to be spending time with its characters any longer, and I hope that a sequel or continuation of this fascinating saga awaits in due course.

London, Burning is due to be published by Little, Brown on 8 April 2021

Enjoying The Critic online? It's even better in print

Try five issues of Britain’s newest magazine for £10

- Book Review

- Historical Fiction

What to read next

Murders for April

From the golden age of crime fiction to the modern day, Jeremy Black recommends seven books to see you through April

Murders for the onset of shorter days

Professor Jeremy Black on British Library Crime Classics and his favourite ‘whodunits’

Murder stories for December days

Jeremy Black makes his way through the British Library’s Crime Classics collection

Escaping Plato’s goon cave

Vision Pro illuminates the telos of modernity and the narrowing of human experience

An array of civilised music

Walter Kaufmann: 3rd piano concerto, 3rd symphony &c. (CPO)

Time for realpolitik in Israel

Britain’s foreign policy in the Middle East should put British interests first

How widespread is NHS qualifications fraud?

A viral Twitter post raises uncomfortable questions about the level of training in British institutions

There is no conservative case for Keir Starmer

Despairing at the Tories is understandable, but the opposition of your opposition is not your ally

Hatred and mental illness are not mutually exclusive

Violent men being mentally ill need not make broader societal phenomena irrelevant

Wragg must go

He should resign or be fired

Giants and pygmies

Some stop-gap leaders of the opposition were never intended to be potential prime ministers

The shadowy economics of fentanyl

One professor is investigating how the deadly drug trade works — and how it might be fought

Religious freedom is back on the agenda

The International Freedom of Religion or Belief Bill, currently before parliament, is an important step for securing Britain’s role in promoting religious liberty

War on Nazis in Oz and in the air

LeBor reviews Our Dad the Nazi Killer and Masters of the Air

This is one of your 3 free articles without registering

For full access, subscribe to The Critic for less than £3 per month.

Already have an account? Log in .

SUBSCRIBE REGISTER FREE

You've reached the end!

Don't worry.

You can register for free to read Artillery Row articles.

Or get full access to The Critic for as little as £3 per month.

REGISTER FREE SUBSCRIBE

Premium access only.

Don't worry. You can continue reading by subscribing to get full access.

- Coffee House

Dark days for Britain: London, Burning, by Anthony Quinn, reviewed

The national front reaches its peak of popularity as ira bombs terrorise the capital in this disturbing novel set in the late 1970s.

- From magazine issue: 17 April 2021

Mark Bostridge

London, Burning

Anthony Quinn

Little, Brown, pp. 339, £14

Not long ago, a group of psychologists analysing data about national happiness discovered that the British were at their unhappiest in 1978. Reading Anthony Quinn’s enjoyable novel set in that year and early 1979, it’s not difficult to see why. In case you’ve forgotten, strikes were spreading like wildfire. The National Front were reaching a peak of popularity. Most alarming of all, the Provisional IRA were expanding their bomb attacks on mainland Britain.

Most popular

Tory mps savage poulter in the group chat.

There were compensations. Kate Bush’s whiny lament ‘Wuthering Heights’ was released in 1978, and there was a new Pinter at the National Theatre ( Betrayal ). Punk rock was going commercial. One of the characters in London, Burning turns up at a party in a white trouser suit with kick-flares, a sort of homage to John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever . Quinn trowels on the period detail in a way that initially feels oppressive and faintly ridiculous, but which becomes increasingly funny with each new placement.

Into this maelstrom are thrown four protagonists: Vicky, a young policewoman; Hannah, a streetwise reporter on a national (too much like a stock character); Calum, a struggling Irish academic; and Freddie, a theatrical impresario (the best realised of the lot). Their destinies are interlinked in a narrative dependent on a series of coincidences, excused here as illustrating the randomness of life. The capital itself doesn’t figure much as a character, merely as a backdrop. Nor is there a great sense of 1970s society being on the brink of change. There’s something curiously static about this, as if the novel’s larger underlying themes had failed to rise to the surface.

Quinn lights a long fuse and stands well back. The story’s two bomb explosions, the first killing the shadow home secretary — a fairly colourless rendition of Airey Neave, mysteriously disguised as ‘Middleton’, which was Neave’s second name — are every bit as exciting and climactic as they should be. The loud thunderclap of one bomb going off made me shudder at the memory of an IRA explosion which I witnessed at close quarters and which came close to killing me. Extraordinary to think of the extent to which, as a pupil at a central London school in 1978, one’s existence was constantly shadowed by the threat of bomb scares and actual explosions.

Off stage, at the end of the novel, is the country’s triumphant first woman prime minister. ‘The barbarians are at the gates,’ declares one character. ‘Who knows,’ says another, ‘the change might do us good.’

Taylor Swift’s new album is exhausting

Because you read about airey neave

The sheer tedium of life at Colditz

Also by Mark Bostridge

Sisterly duty: The Painter’s Daughters, by Emily Howes, reviewed

Humza Yousaf’s five worst moments as First Minister

Comments will appear under your real name unless you enter a display name in your account area. Further information can be found in our terms of use .

London, Burning

Anthony Quinn Little, Brown Released 8 April 2021

Go to book...

In his earlier novel, Curtain Call , Anthony Quinn demonstrated great interest in and impressive knowledge of the London Theatre scene just before the Second World War. While London, Burning ranges more widely, one significant thread follows the activities of a theatre director enjoying his pomp in the 1970s, when this novel is set.

Quinn’s style is to start a number of hares running, slowly but inexorably bringing them together in plots that are always satisfying and often thrilling. In this case, we follow the trail of Vicky, a young police officer who finds herself embroiled in a series of juicy cases but also an uncomfortable web of corruption.

Then there is Callum, a bookish lecturer from Newry in Northern Ireland with an accent that instantly inflames prejudice at a time when the IRA was launching a war on the United Kingdom with explosive activity in London.

The linchpin who eventually connects each of the themes is a Fleet Street broadsheet journalist named Hannah. She is good at her job but also attractive enough to ensure that every man in the novel makes a play for the desirable hack. That includes theatre director Freddie, the talented grandee in charge of the fictional National Music Hall.

The name may include something of an in-joke, since anyone with a reasonable knowledge of theatre history of the period will instantly recognise a portrait that feels incredibly close to the future Sir Peter Hall. As readers will discover, Freddie is not only a self-promoting workaholic but also a superb theatre director and compulsive adulterer.

He is not the only real-life character mildly fictionalised to ramp up the drama. The shadow Home Secretary who hopes to take over as Northern Ireland minister in a future government led by Margaret Thatcher, if only she can win the election, has much in common with the late Airey Neave, once an escapee hero of Colditz and subsequently a strong-willed, unforgiving Tory politician.

Having introduced these memorable characters and many more, Anthony Quinn weaves a plot that features Freddie trying to balance a precarious love life and stressful career as his 50 th birthday approaches, Hannah and Vicky pairing up to do detective work after a pair of IRA bomb outrages and some political inside knowledge as strikes and then the 1979 general election threaten to wreck Freddie’s birthday party, not to mention the career of James Callaghan.

As always, this author has written an addictive page turner, while at the same time showing off his literary credentials and a great knowledge of the stage, not to mention the colourful history of one of its most highly regarded and larger-than-life characters.

Reviewer: Philip Fisher

* Some links, including Amazon, Stageplays.com, Bookshop.org, ATG Tickets, LOVEtheatre, BTG Tickets, Ticketmaster, The Ticket Factory, LW Theatres and QuayTickets, are affiliate links for which BTG may earn a small fee at no extra cost to the purchaser.

Are you sure?

- All content

- Rural Alaska

- Crime & Courts

- Alaska Legislature

- ADN Politics Podcast

- National Opinions

- Letters to the Editor

- Nation/World

- Film and TV

- Outdoors/Adventure

- High School Sports

- UAA Athletics

- Food and Drink

- Visual Stories

- Alaska Journal of Commerce (Opens in new window)

- The Arctic Sounder

- The Bristol Bay Times

- Legal Notices (Opens in new window)

- Peak 2 Peak Events (Opens in new window)

- Educator of the Year (Opens in new window)

- Celebrating Nurses (Opens in new window)

- Top 40 Under 40 (Opens in new window)

- Alaska Spelling Bee (Opens in new window)

- Alaska Craft Brew Festival

- Best of Alaska

- Spring Career Fair (Opens in new window)

- Achievement in Business

- Youth Summit Awards

- Lynyrd Skynyrd Ticket Giveaway

- Teacher of the Month

- 2024 Alaska Summer Camps Guide (Opens in new window)

- 2024 Graduation (Opens in new window)

- Alaska Visitors Guide 2024 (Opens in new window)

- 2023 Best of Alaska (Opens in new window)

- Alaska Health Care (Opens in new window)

- Merry Merchant Munch (Opens in new window)

- On the Move AK (Opens in new window)

- Senior Living in Alaska (Opens in new window)

- Youth Summit Awards (Opens in new window)

- Alaska Visitors Guide

- ADN Store (Opens in new window)

- Classifieds (Opens in new window)

- Jobs (Opens in new window)

- Place an Ad (Opens in new window)

- Customer Service

- Sponsored Content

- Real Estate/Open Houses (Opens in new window)

When fiction borrows from real life: the Alaskan behind London’s ‘Burning Daylight’

Norwegian rookie Thomas Waerner mushes on the Yukon River between Nulato and Kaltag on Sunday, March 15, 2015. (Loren Holmes / ADN archive 2015)

Imagine you — yes, you, gentle reader — a character in a novel. How would you feel, sitting in your favorite chair reading about the version of you a writer has transformed into a fictional character? Would the chaired you recognize, much less approve of, the you in motion throughout pages of the novel?

Real people appear in fiction frequently — sometimes under their own name, sometimes not.

Several decades ago, New York Times columnist William Safire wrote a bestseller about Abraham Lincoln. Safire made it clear up front: This is a novel. But so many legends surround the Great Emancipator it is hard to know where fact ends and fiction begins, even in some Lincoln biographies.

Novelist Thomas Wolfe (1900-1937) wrote “Look Homeward Angel,” a lengthy fictionalized account of his childhood in Asheville, N.C., featuring his parents and himself as major characters and many neighbors as extras. The portrayal of the Wolfe family as the Gants — a betrayal in the minds of the home folks — provoked a Carolina uproar so loud Thomas Wolfe did not return homeward for eight years.

Probably the best-known Alaskan who became a fictional character (putting aside politicians in their memoirs) is Elam Harnish (1866-1941) a Gold Rush dog musher, miner, woodsman and fully certifiable sourdough by any definition. Nicknames proliferated during the Gold Rush and after — for instance, the Snowshoe Kid or the Highpower Swede. Harnish was known as “Burning Daylight,” a moniker allegedly bestowed on him by a cabin mate whom Harnish hectored to get out of bed because the morning was a-wastin’; he said the mate was “burning daylight.”

Writer Jack London (1876-1916), who joined the Klondike stampede an untested greenhorn, knew Harnish well. By Harnish’s account, they were cabin mates. Some 10 years after London quit moiling for gold in the frozen north and returned to his hometown, San Francisco, he wrote the novel “Burning Daylight.” It’s still in print through the University of Alaska Press. The hardcover edition I have was published by Macmillan in 1913. It has a crude drawing of a dog musher and his husky on the copper-colored cover.

The opening chapters of “Burning Daylight” are set in Circle City on the Yukon River in 1895, before the Klondike stampede. It’s Daylight’s 30th birthday, and he has come to the local saloon this winter eve to celebrate. This big, strong, generous, handsome man proclaims, “Drinks are on me, boys!” and the party is on. The omniscient author — London — tells this part of the story in “Robert Service-ese;” that is, the imagery, the allusions, the cliches of Service poetry.

This is rather like issuing the characters uniforms. So the Frenchman is sure to begin his sentences with “By Gar” and the Scandinavian with “By Yupiter.” The Lady Who Is Known as Lou appears in this barroom as The Virgin. Well, she does have a heart of gold – and has her own gold, so she is not after Daylight’s. She’s after his body. But Daylight prefers the manly comradeship of the woods. No woman is going to tie him to her apron strings.

The next hundred pages are set on the winter mail trail. Daylight mushes from Circle City to Dyea and back with the frosty postal bags, and this interlude is the best part of the book. As he proved in his classic short story “To Build a Fire,” London was a master painter of the natural world. The frozen Yukon River, the snow-covered hills, the midday sun barely peeking over the horizon are beautifully rendered.

Before long, gold is discovered in the Klondike. The rush is on. Daylight is not just a miner with a pick and shovel: He is a visionary who stakes claims wherever the diggin’ looks promising. He applies modern industrial techniques to mining. He becomes rich, still beloved by his male peers but successfully resisting female temptation. With $11 million in his Gladstone bag, he heads for San Francisco to “try his hand” in a bigger game.

To conclude what amounts to a Three-Minute Shakespeare summary of “Burning Daylight,” in the Bay Area, the musher-miner becomes a cruel, rapacious titan of industry who crushes rivals, leaves the downtrodden further trodden, and triples his fortune. He also becomes a martini-soaked, flabby, obtuse wretch — but not so obtuse he fails to notice his stenographer, Dede, is a pretty little gal. When a national financial panic ruins many a capitalist, Daylight barely survives — but now, enlightened by the gal, he gives up his empire and the newlyweds move across the bay to Sonoma, finding marital bliss on their farm.

The love of a good woman has saved a man gone wrong. Cue the Tin Pan Alley hit of yesteryear, “Big Bad Bill is Sweet William Now.”

A New York Times review said London had no talent for describing men and women: Jack, stick to dogs.

The major magazines of 1890-1910 were packed with similar redemptive tales. The actual dynamics of male-female relationships were relegated to the police blotter.

What did Harnish think of “Burning Daylight?” Allegedly, he said the book was like the northern weather: sometimes good, sometimes bad, but he was happy London remembered him.

The Elam Harnish of Jack London was built like a rangy NFL receiver. Historian Terrence Cole reported that the Harnish who died in Fairbanks and lies in the Birch Hill Cemetery was, though muscular, 5-foot-2.

Michael Carey is an occasional columnist and the former editorial page editor of the Anchorage Daily News.

The views expressed here are the writer’s and are not necessarily endorsed by the Anchorage Daily News, which welcomes a broad range of viewpoints. To submit a piece for consideration, email commentary(at)adn.com . Send submissions shorter than 200 words to [email protected] or click here to submit via any web browser . Read our full guidelines for letters and commentaries here .

Michael Carey

We have updated our Privacy Policy Please take a moment to review it. By continuing to use this site, you agree to the terms of our updated Privacy Policy.

- Facebook Icon

- Twitter Icon

London, Burning

By anthony quinn.

8th April 2021

Price: £14.99

Fiction & Related Items / Modern & Contemporary Fiction (post C 1945)

Select a format

- Audiobook Downloadable

- Blackwell's

- Bookshop.org

- Waterstones

Disclosure: If you buy products using the retailer buttons above, we may earn a commission from the retailers you visit.

Newsletter Signup

Get recommended reads, deals, and more from Hachette

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

Subscription Offers

Give a Gift

London Burning

A fresh account of how Londoners responded to the impact of the Second World War.

In this, his eighth book on London’s history, Jerry White gives us a fresh and masterful account of how Londoners responded to the impact of the Second World War. This is well-trodden territory, but White offers a distinctive perspective on the appalling toll from the air raids and how officials and volunteers came together to save lives and their city.

It became fashionable in the 1990s to write of ‘the myth of the Blitz’ and White usefully contextualises this trend. He points out that observers in 1940 needed ‘a story’ and critical assessments based on local failings had a lasting effect. Even Mass Observation could be ‘constitutionally disposed to look on the gloomy side of life’. The reality was more complex.

There are expert insights into the politics of local civil defence. Labour fiefdoms could be resentful of the arrival of well-intentioned volunteers. Poplar was ‘a model of civil defence’, in contrast to Stepney, where there were failings of leadership. The better-run boroughs had the good sense to bring their post-raid facilities into one building to save the bombed-out from having to traipse from one office to another. As for central government, it was known to be penny-pinching and was often under suspicion.

There is interesting material on London’s economy, including the adaptability of companies to the demands of the war. Ford Dagenham, for example, produced nearly 350,000 army lorries, RAF tractors and troop carriers. We get a sense of the physical changes to the city – the huge pile of rubble trucked over from the devastated areas and heaped up in Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park. Everyone was conscious of class differences, but there was greater equality now: air raid warden Barbara Nixon observed how a number 38 bus conductor neatly reproved a well-to-do woman who complained about the presence of a wretched-looking passenger with her two children. With dust and glass in their hair, the conductor could see that they had just survived a raid.

Throughout the book White deploys the words of a handful of diarists: typists, a clerk, a warehouseman, a social worker. ‘Hope to goodness my nerve doesn’t break’, confided Olivia Cockett. ‘How I hate myself for being sick with fear’, worried Vivienne Hall. With them we sense the relentless arrival each year of Christmas, somehow needing to be celebrated despite shortages and there being no end in sight.

The rest of the nation knew that London had had it the worst. White gives us little-known episodes, like the selfless support that came from the provinces at the time of the V1 flying bomb attacks: 1,000 air raid wardens from across Britain travelled to the capital to help defend it against this new and terrifying phenomenon. The WVS (Women’s Voluntary Services) ingeniously organised the ‘adoption’ of London boroughs by regions in the rest of the UK. Warwickshire adopted Shoreditch, Shropshire adopted Hackney and so forth, supplying them with all manner of furniture and appliances.

Eventually the war ended, but the scale of the destruction meant that there was desperate overcrowding and homelessness, with thousands in temporary billets and shelters. Nearly 30,000 Londoners had lost their lives and over 50,000 had been hospitalised by injury. The collectivism that had been ‘woven into the fabric of every neighbourhood’ had produced extraordinary bonds but, as White shows us in this masterful account, the city’s recovery would take decades.

The Battle of London 1939-45: Endurance, Heroism and Frailty Under Fire Jerry White The Bodley Head 448pp £30 Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Suzanne Bardgett is Head of Research and Academic Partnerships, Imperial War Museum Institute.

Related Articles

Beneath the Bombs

Is the Story of ‘The Few’ More Myth Than Reality?

Popular articles.

‘Bluestockings’ by Susannah Gibson review

Life and Land in Anglo-Saxon England

London, Burning › Customer reviews

Customer reviews.

London, Burning

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. Please try again later.

From the united states, from other countries.

- ← Previous page

- Next page →

Questions? Get fast answers from reviewers

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Advertisement

More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

May 9, 2024

Current Issue

May 9, 2024 issue

Kim Dorland

Kim Dorland: Fever Dream , 2022

Submit a letter:

Email us [email protected]

Fire Weather: A True Story from a Hotter World

The Heat Will Kill You First: Life and Death on a Scorched Planet

In 1957 Manley Natland, a geologist working for the California-based Richfield Oil Corporation, was sent to the Athabasca oil sands in Alberta, Canada, where he hatched a terrible plan. Extracting crude oil from tar sands is a slow, dirty, and expensive task, requiring the separation of bitumen—a thick oil substance—from the sandy peatland of the Canadian forests. Seeking a more efficient method, Natland figured that setting off nuclear bombs might make the process easier.

His idea, later named Project Oilsand, was in line with the nuclear fever dreams of the late 1950s and early 1960s, when scientists and politicians in Canada, Russia, and the United States were considering all variety of ways of “taming the H-bomb.” (Another government initiative, Project Plowshare, championed by Edward Teller—“father of the hydrogen bomb”—was exploring the use of nukes to build canals, dam rivers, and dig for precious metals.) Speaking before the Atomic Energy Research and Development Subcommittee on March 22, 1960, the president of Richfield Oil, W.J. Travers, proposed exploding a nine-kiloton atomic device—just over half the strength of “Little Boy,” the bomb US Air Force pilots dropped on Hiroshima—1,300 feet underground in the Canadian wilderness. “The explosion,” said Travers, “would suddenly liberate 9 trillion calories of heat,” as well as, he hoped, lots of oil.

Setting off radioactive bombs under the earth dangerously contaminates the water and surrounding dirt, but Travers told the committee members that “based on available information, Canadian and United States scientists who have carefully studied the safety problem are convinced that the proposed 9-kiloton test would not result in harmful effects.” The US government not only approved the proposal but agreed to supply the bomb. The plans were eventually set aside without being tried—perhaps owing to fear of Russian espionage rather than safety concerns. Yet given the zeal with which humans in the last three quarters of a century have found other ways to suck vast amounts of petroleum out of the earth, a handful of nukes detonated in the Canadian muskeg would have been just a drop in the barrel of oil’s “harmful effects.”

Few books on climate change have so viscerally captured the destruction we’ve wrought by our reckless addiction to petrochemicals as John Vaillant’s Fire Weather , which takes place mostly in those same boreal tar sands that Natland wanted to detonate. Today the US imports almost four million barrels of oil a day from Canada, about 90 percent of which comes from the tar sands. In May 2016 a wildfire enveloped the boomtown of Fort McMurray, in northern Alberta. It was so powerful that one expert in fire physics, delivering a sort of post-ignis-mortem, said, “The best analogy is the Hamburg firestorm”—the Allied campaign in World War II known as Operation Gomorrah, which dropped 9,000 tons of bombs on the German city, killing around 37,000 people.

Vaillant tells the story of the Fort McMurray fire as a lesson: the myriad comforts of the Petrocene—oil-fueled heating, cooling, transportation, and manufacturing—come at a cost. After an abnormally hot and rainless spring, the forest around the town was bone-dry. Vaillant makes that cost dramatically visible by describing in detail the hellaciously hot towers of flames spawned by a fire tornado that tore through the town; pyrocumulonimbus clouds up to two hundred miles wide that pierced the stratosphere; and spontaneous explosions known as “dragons”:

Godzilla-sized and -shaped eruptions of combusting gas bursting from the crowns of superheated conifer trees can be three hundred feet high and are hot enough to reignite the smoke, soot, and embers above them, driving flames hundreds, even thousands, of feet higher into the smoke column.

The fire burned for fifteen months and spread to nearly a million and a half acres until it was finally extinguished in August 2017. In its first days of life (Vaillant repeatedly attributes organic, almost sentient qualities to fire) it was so hot and destructive that entire houses were rendered into ash heaps in five minutes, “like milk cartons in a bonfire.” In an aside on the 2018 Carr fire in and around Redding, California, Vaillant describes another fire tornado with wind speeds reaching 165 miles per hour and temperatures likely close to 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit—about three times as hot as the ambient temperature on Venus. Fire-flecked Category 5 hurricane–level winds with “metal-melting heat,” Vaillant writes, “seemed gratuitously biblical.” Even seemingly impermeable enamel toilets and cast-iron pans were practically disintegrated by the flames. “Natural fire never did this,” said one fire expert surveying the damage. “It shouldn’t moonscape.” But it did.

This is all captivating, terrifying stuff, especially through Vaillant’s excellent telling. He has a penchant for finding stories of monomania: his first book, The Golden Spruce (2005), is about a logger turned crusading anti-logger who, in a confused act of ecoterrorism, chops down the titular tree—considered sacred by the indigenous Haida people—in British Columbia. His next, The Tiger (2010), chronicles a vindictive, homicidal Siberian tiger and an expert tracker’s efforts to contain him. Vaillant has also written a novel, The Jaguar’s Children (2015), which similarly captures a superhuman will: a young migrant’s attempt to escape from the almost airless tank of a water truck that he is trapped inside with fourteen other passengers in southern Arizona.

Fire Weather paints a less individual portrait of obsession and doom. Despite being virtually unknown outside of the petroleum industry, over the last fifty years the petro-city of Fort McMurray became one of the largest cities in the subarctic. That’s thanks to bitumen. But harvesting bitumen—a process Vaillant calls “the petrochemical equivalent of squeezing blood from stones”—was only profitable enough to have turned a remote Albertan outpost into a boomtown because of generous government subsidies and voracious oil demand.

Wildfires are a part of life in the boreal forest, and Vaillant writes that for residents of Fort McMurray the smoke clouding the horizon in late April 2016 initially

represented a familiar seasonal awareness, occupying the same mental space as the possibility of a thunderstorm or a blizzard—one among many manageable threats long since factored into the calculus of daily concerns.

But the fire that ultimately consumed the city—the area’s ninth so far that year—quickly proved to be uncontainable.

Vaillant follows its first flickers from the unconcerned tone the mayor and municipal fire chief take at a press conference—the chief admits that the situation has gotten hairy, but hopes that “nature’s done its thing and it’ll leave us alone for a little bit”—to, two days later, the gradual realization that the black clouds billowing increasingly close to densely populated neighborhoods are an urgent threat requiring evacuation. As residents scramble to flee, a traffic jam bottlenecks the roads out of town. Meanwhile local and regional firefighters resort to unorthodox methods and begin using enormous bulldozers and backhoes to rip down houses, razing entire blocks in attempts to starve the fire of fuel.

Vaillant is masterful at dropping the reader into such scenes: barbecue propane tanks exploding like bombs; garages storing sundry combustibles, such as gas cans or welding tanks, becoming giant incendiary devices; a man in shorts and T-shirt using a bulldozer blade as a blast shield as flying gravel and embers swirled around him and “stung like hornets.” You almost feel as if the paroxysmal blazes will burn to the last page.

Amazingly no one died as a direct result of the Fort McMurray fire. Over 90,000 people were displaced, and the fire destroyed about 2,400 homes and buildings. Residents were lucky: large parts of town were spared, many people eventually returned, and—what some count as a success—before the fire was even extinguished, oil production, which had plummeted by about a million barrels a day, resumed. But the townspeople also faced long-simmering consequences: property loss, depression, alcoholism. The climate-wrecking single-industry town turned tinderbox seems a paragon of hubris. Yet Vaillant doesn’t point his finger at the residents, or the workers burning all the gas to extract all that crude. Instead he blames the corporate rapacity, the misguided subsidies, the collective blind eye, and the century of oil-fueled momentum that set the town aflame.

Vaillant traces that hubris back to another Canadian town—Enniskillen, Ontario—in 1858, when the “first productive New World oil wells” were dug. The following year in Titusville, Pennsylvania, “so many wells were dug, so quickly and in such close proximity,” Vaillant writes, “it seemed as if the local fields had suddenly sprouted bumper crops of wooden oil derricks.” The process of safely and efficiently getting the oil from under the shale and into a barrel, however, was then and very much remains inexact. A nearby Titusville creek soon began shimmering with iridescent slicks—some of them catching fire. Even in the initial decades of the oil rush, prescient scientists and some common observers knew that we were, quite literally, playing with fire.

Fire is not necessarily bad, of course. It has kept us warm, fended off predators, set the mood, and helped us digest food for hundreds of thousands of years. Yet our reliance on it has become so ubiquitous, with trillions of fires burning across the world every day, according to Vaillant’s calculations (he includes in his tally fires less visible than the forest kind, such as those burning in gas stoves, pilot lights, incinerators, matches, and the combustions of all sorts of engines), that “humans could easily be mistaken for a global fire cult.” To fuel those many trillions of fires, “on any given day, the human race consumes about 100 million barrels of crude oil, while another 40 million barrels are in transit around the globe via tanker, pipeline, truck, and train.”

In the last section of Fire Weather , Vaillant walks the reader through the rise of early climate science, showing that we well knew the consequences—dangerously rising global temperatures—of all that smoke. It was the pioneering American “artist, inventor, citizen scientist, and early suffragist” Eunice Newton Foote who conducted what became known as the first-ever climate change experiment. In 1856 Foote filled one glass cylinder with carbon dioxide and let another fill with ordinary air, then recorded how quickly they heated up in the sun: the cylinder with what she called “carbonic acid gas” heated up twice as quickly. In other words: watch out.

Eighty-two years later, in 1938, the English engineer and inventor Guy Callendar was proving not only that “the activities of man could have any influence upon phenomena of so vast a scale” as the planet’s climate but that it “is actually occurring at the present time.” That year the parts per million of CO 2 in the atmosphere was about 311. Today it is 421—and rising.

Our use of oil, in many ways, has transformed both the planet and humankind’s place in it. Take one specific scenario Vaillant paints:

Behind the wheel of a Chevy Silverado, a one-hundred-pound woman can generate more than six hundred horsepower as she draws a six-ton trailer at sixty miles an hour while talking on the phone and drinking coffee, in gym clothes on a frigid winter day. Prior to the Petrocene Age, only a king or a pharaoh could have summoned such power.

“Today,” Vaillant concludes, “with cheap and plentiful oil at our disposal, everyone’s an emperor.”

Vaclav Smil, in How the World Really Works (2022), estimates that the average adult now “has at their disposal nearly 700 times more useful energy than their ancestors had at the beginning of the 19th century.” Translating that into physical labor, Smil calculates that the amount of easily accessible energy people in affluent countries often thoughtlessly burn throughout the day—charging a laptop, checking the time on a nightstand clock, relying on a running refrigerator, or being guided by traffic signals—equals the human power of between 200 and 240 people working for you nonstop, day and night. Having that energy at your disposal may appeal, but underlying that opulence is an inherent volatility.

Such multibillion-dollar fires as Fort McMurray, in which whole cities or neighborhoods succumb to flashover—“sudden and total combustion”—will become more frequent in coming decades. And yet, Vaillant reports, they still seem so unlikely from our perches of comfort that even when they do strike, when the fire is already surrounding a neighborhood or home, people remain in denial. Vaillant relays one woman’s experience: as black clouds sparkling with embers began to blot out the sun and swirl ever closer to the neighborhood, she went to drop off clothes at the dry cleaner. After some hesitation, the worker took the woman’s clothes, logged the drop-off, and said, “Tuesday good?” and the woman responded, “Yeah, next Tuesday’s great.”

But next Tuesday there would be no dry cleaner, no laundry machines, no clothes. Following the author and risk analyst Nassim Taleb, Vaillant refers to such denialism as the Lucretius problem, after the Roman philosopher who noted that a fool believes that the tallest mountain he’s seen is the tallest in existence: “the self-protective tendency to favor the status quo over a potentially disruptive scenario one has not witnessed personally.” Such self-protection only goes so far. We can refuse a thought or deny evidence, but the flames will catch up.

Caught up they have. In June 2021 a heat dome formed and hovered over the Pacific Northwest and western Canada. In British Columbia temperatures topped 121 degrees. At one point, in just a twenty-four-hour period, the temperature in downtown Portland jumped from 76 degrees to 114 degrees. It got so hot, Jeff Goodell writes in his latest book, The Heat Will Kill You First , that “if you’d had the right kind of microphone, scientists say, you could have heard the trees screaming.”

Seattle-area doctors, desperate to lower body temperatures as quickly as possible, filled body bags with ice and zipped people inside. Still, about a hundred people died of the heat. Other deaths more than doubled that month. As bad as it was, Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver could have seen much worse. Europe suffered deadly heat waves in 2003 and again in 2022, which killed approximately 70,000 and over 61,000 people, respectively, most of them elderly or with some underlying condition. “A heat wave is a predatory event,” Goodell writes, “one that culls out the most vulnerable people”—especially the poor. The difference in temperature between rich and poor parts of Portland during that 2021 heat wave, largely due to the “urban heat island effect”—dense concentrations of unshaded concrete—was 25 degrees. As Goodell shows, it only takes a couple of notches up on the climatic thermostat to make the difference between sweaty and dead.

Goodell, a contributing writer at Rolling Stone , has focused his reporting on climate change for over two decades. His previous books include Big Coal (2006) and The Water Will Come (2017). Like Vaillant, Goodell mixes doomsaying with useful finger-pointing. “At some point in the not-so-distant future,” he writes, “the question of who burned the fossil fuel that caused the heat wave that killed Jane Doe will become the climate version of who pulled the trigger of the gun that killed Jane Doe.”

Researchers, activists, and writers such as Vaillant and Goodell are turning climate crises into whodunnits, which is politically and even existentially useful. One of Goodell’s more uplifting chapters, “Anatomy of a Crime Scene,” tells the story of the rise of “extreme event attribution.” Scientists such as Friederike Otto, a German-born climatologist working in Britain, are studying to what extent climate catastrophes are caused by man-made climate change. It’s the “first science ever developed with the court in mind,” Otto tells Goodell. The hope is to pin climate crimes on polluters, clarifying legal liability and beginning to answer the question, “Who is responsible for trashing the climate, and how can they be held responsible?”

The Heat Will Kill You First spans the globe, with Goodell constantly on assignment, jumping from melting icebergs in Antarctica to the scalding streets of Chennai. His stories make heat, and the dangers it incites, visible in new ways: one of his chapter titles is “What You Can’t See Won’t Hurt You,” a dangerous misconception. In a discussion of the history of Parisian architecture, he shows not only why spikes in summer temperatures fry residents under traditional zinc roofs, but how difficult it will be for such a city in coming decades to adapt and keep cool. Heat-proofing Paris is possible but would be a monumental undertaking. “That’s the thing with cities,” Goodell writes. “Unless you have an emperor like Napoléon III or a power broker like Robert Moses, retrofitting takes time.”

What is decidedly not the ultimate answer to being fried in your own city is air-conditioning, Goodell reports. In the summer of 2018, the same season that temperatures in Phoenix, Arizona, crested at 116 degrees—by now this is expected weather—the utility provider Arizona Public Service cut off power to Stephanie Pullman, a seventy-two-year old woman who lived alone with her cat, Cocoa. At the end of August, the company had written her a warning letter, requiring that she pay the $176.84 she owed in the next five days. Pullman, who had been stretching less than a thousand dollars a month in social security payments, paid $125 after receiving the letter, but she was still in arrears. As for many people in Phoenix and the American West, for Pullman air-conditioning was a survival tool. After the utility company turned off her electricity, she died of heat.

Arizona utilities customers are now protected from service shut-offs during extreme weather. Still, Maricopa County, where Phoenix is situated, recorded over six hundred heat-associated deaths in 2023. Most of those who die are poor, often unhoused—a condition Goodell calls “temperature apartheid.”

Goodell interviews Mikhail Chester, a researcher focused on adaptation to climate change who says that Phoenix suffering a major power outage in the summer months—possibly due to a spike in energy usage in reaction to a heat wave, or a wildfire knocking out a power line on a hot day—is inevitable. That could put as many as 1.6 million people into the situation Stephanie Pullman faced: soaring indoor temperatures with no working air conditioners or fans to beat the heat. Chester wondered aloud to Goodell: “What will the Hurricane Katrina of extreme heat look like?”

Using AC to save lives and keep comfortable is a problem not only because it makes us dependent on an undependable fix. Such reliance also keeps us from pursuing more responsible mitigation such as building houses with more shade, more airflow, and less heat-absorbent material. Even more concerningly, it creates a feedback loop: millions of people cooling their homes in high heat requires vast amounts of fossil fuel energy, which increases the level of CO 2 in the atmosphere, which further raises temperatures, which requires more cooling, more energy, and then, one day: blackout.

Heat can push human bodies into a similar “lethal feedback loop.” Once your core body temperature rises to 102 or 103 degrees, your heart desperately tries to pump blood toward the surface of your skin to cool it down. But the faster your heart beats, the higher your metabolism rises, which generates more heat, and so the heart pumps faster, creating yet more heat, and then a higher heart rate, and by the time you reach 107 degrees your cells begin to, as Goodell puts it, “denature.”

What is particularly frightening about hyperthermia, the medical term for a body getting just a few degrees warmer than the Goldilocks range—that just-right spot between about 97 and 99 degrees—is that the brain stops working very well. Goodell tells the story of Kelly Watt, an eighteen-year-old track star who went on a too-long run on a too-hot day in Virginia in 2005 and then died. Handprints found on his car suggested that he had likely made it there, but the heat may have so blurred his thinking that he couldn’t figure out how to open the door and turn on the AC , which probably would have saved his life. Reading Goodell and Vaillant you may begin to wonder if civilization itself is getting so hot that we’re no longer thinking straight.

Goodell tracks other troubling effects of heat. Researchers estimate that since the 1990s, extreme heat waves have cost the global economy around $16 trillion. “When people are stressed by heat,” Goodell writes, “racial slurs and hate speech in social media spike. Suicides rise. Gun violence increases. There are more rapes and more violent crime.” One study found that people honk their car horns more. Higher temperatures have been linked to the outbreak of civil war and migration. “For every degree Celsius of increase in global mean temperature,” Goodell writes, “yields are expected to decrease by 7 percent for corn, 6 percent for wheat, and 3 percent for rice.”

Vaillant offers some hope at the end of Fire Weather , musing on the concept of revirescence—a capacious term for regrowth and regeneration that he imbues with a shade of spirituality. Less than a month after the Carr fire ripped through towns in Northern California, Vaillant writes, green tendrils “burst through the scorched hardpan, nourished by the still-vital roots of those flayed and blackened trees.” Goodell, overall, isn’t as sanguine. In the course of his research he discovered not only “how easily and quickly heat can kill you” but also “how deeply connected we are to one another and to all living things.” So we will all cook together—slight comfort as the mercury creeps upward and wildfires continue to kindle.

‘Who Shall Describe Beauty?’

Israel: The Way Out

Subscribe to our Newsletters

More by John Washington

Javier Zamora’s retelling of the almost lethal three-thousand-mile journey he made from El Salvador to the US as a child gives the experience of migration extraordinary immediacy.

June 8, 2023 issue

John Washington is a staff writer at Arizona Luminaria . His most recent book, The Case for Open Borders , was published in February. (May 2024)

The Russians Have a Word for Dressing Up Reality

December 22, 1988 issue

The Unmaking of Men

October 21, 1999 issue

The Fate of the Union: Kennedy and After

December 26, 1963 issue

The Tipping Point?

January 12, 2006 issue

The Man Who Said No

November 3, 2005 issue

Beware Tamiflu!

May 26, 2011 issue

On Arnold Relman (1923–2014)

A towering figure in American medicine

August 14, 2014 issue

A Deer Harvest?

April 25, 2013 issue

Subscribe and save 50%!

Get immediate access to the current issue and over 25,000 articles from the archives, plus the NYR App.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

England Is Mine by Nicolas Padamsee review – battle lines are drawn

Two teenage boys come of age in a divided and radicalised London in this politically charged debut

T he perilous porousness between our online and offline worlds is the spark for Nicolas Padamsee’s tinderbox thriller about two teenage boys. Deeply astute and devastating in its commentary on immigrant communities, England Is Mine joins a new generation of politically charged novels – including Megha Majumdar’s A Burning and Priya Guns’s Your Driver Is Waiting – in exposing the power and pitfalls of online platforms.

Two youths, David and Hassan, whose intertwined tales are told by turns, are students at the same school in east London. David is a strict vegan and has few friends. He doesn’t plan on going to university (“There would be no reading novels anyway, he thinks. There would only be criticising novels for their heteronormativity, their whiteness, their Europeanness, their whateverness”). As an Anglo-Iranian, he perpetually feels the burden of the question “Where are you from?” His parents are divorced. Between caring for his vulnerable father on the one hand, and bickering with his overbearing but well-meaning mother on the other, he is forced to flit between two houses but rarely feels at home.

He puts all his faith and teenage angst into music – and his hero, Karl Williams, reminiscent of Morrissey from the Smiths. A series of bigoted comments get the singer-songwriter in trouble, and, soon enough, he is cancelled. The news further unmoors David. Slowly at first, then very swiftly, he begins to lose himself to the far-right corners of the dark web – full of trolls, rows and racists.

Meanwhile, Hassan, a West Ham fan, dutiful son and diligent student, is drifting apart from his childhood friends, who care less about grades and more about drugs and drinking. He finds it hard to shrug off comments that reveal “the way white people in Britain see Muslims”, and is determined to defy false perceptions and get into Goldsmiths. But a violent, racially motivated encounter in a park involving both boys radically alters their life trajectories.

Scarred by this event, David begins to lose his sense of self. He lets himself fall prey to – and eventually participate in – the anti-Islam rhetoric to which he’s exposed online. Hassan, who was an innocent bystander, becomes his enemy and therefore his victim. In the pages that follow, he is reduced to nothing more than “the Muslim” in David’s mind; David becomes “the Aryan”. Now, there’s no room for nuance.

The pace, which is skilfully sustained through 300 pages, quickens as notifications from Twitter (now called X) and YouTube pile-ons keep phones buzzing, then steadies as the two boys face violent moments in the streets. Whether David is in the mosh pit at a gig or caught up in Call of Duty, whether Hassan is playing online Fifa or volunteering for a Muslim Youth Centre helpline, the novel never loses sight of the reader, whether they can relate to gamer and football culture or not.

Padamsee tackles difficult issues – cancel culture, freedom of speech, online radicalism and neo-nazism, masculinity, racial identity, and herd mentality – with a deftness rare for debuts. For his second-generation immigrants, seeking some semblance of belonging in an alienating world, the stakes get ever higher.

As the two teenagers come of age – their beliefs hardened, their hearts broken – we are left questioning our politics and ethics. Who draws the lines between right and left, right and wrong, and what happens when those lines are redrawn, or entirely erased? England is mine. England is mine. England is mine . When the country you call home doesn’t consider you one of its own, who or what will you live – or die – for? Sometimes all you’re left with are desperate, hollow cries in the dark.

after newsletter promotion

- Book of the day

Most viewed

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

London, Burning by Anthony Quinn review - portrait of a divided country. Four strangers are united by the tensions of late 70s Britain in the latest of Quinn's gratifying London novels. S et ...

London, Burning is a novel about the end of the 1970s, and the end of an era. It concerns a nation divided against itself, a government trembling on the verge of collapse, a city fearful of what is to come, and a people bitterly suspicious of one another. In other words, it is also a novel about now. Vicky Tress is a young policewoman on the ...

London, Burning Anthony Quinn Abacus, £8.99, pp344 (paperback) Anthony Quinn's latest impressive novel elegantly depicts a city and an era - the London of the late 1970s - on the verge of ...

London, Burning by Anthony Quinn, (Little Brown, £14.99), 352pp. Quinn's novels all follow a relatively similar trajectory. They are all set in a specific historic period, ranging from the Victoria era ( The Streets) to London, Burning 's keenly evoked depiction of the late Seventies, when Britain was a country of uncollected rubbish and ...

Little, Brown, pp. 339, £14. Not long ago, a group of psychologists analysing data about national happiness discovered that the British were at their unhappiest in 1978. Reading Anthony Quinn's ...

In his earlier novel, Curtain Call, Anthony Quinn demonstrated great interest in and impressive knowledge of the London Theatre scene just before the Second World War.While London, Burning ranges more widely, one significant thread follows the activities of a theatre director enjoying his pomp in the 1970s, when this novel is set.. Quinn's style is to start a number of hares running, slowly ...

Some 10 years after London quit moiling for gold in the frozen north and returned to his hometown, San Francisco, he wrote the novel "Burning Daylight." It's still in print through the ...

London, Burning is a novel about the end of the 1970s, and the end of an era. It concerns a nation divided against itself, a government trembling on the verge of collapse, a city fearful of what is to come, and a people bitterly suspicious of one another. In other words, it is also a novel about now. Vicky Tress is a young policewoman on the ...

London, Burning: 'Richly pleasurable' Observer. Hardcover - 8 April 2021. London, Burning is a novel about the end of the 1970s, and the end of an era. It concerns a nation divided against itself, a government trembling on the verge of collapse, a city fearful of what is to come, and a people bitterly suspicious of one another.

London, Burning is a novel about the end of the 1970s, and the end of an era. It concerns a nation divided against itself, a government trembling on the verge of collapse, a city fearful of what is to come, and a people bitterly suspicious of one another. In other words, it is also a novel about now. Vicky Tress is a young policewoman on the ...

Hardcover - April 8, 2021. London, Burning is a novel about the end of the 1970s, and the end of an era. It concerns a nation divided against itself, a government trembling on the verge of collapse, a city fearful of what is to come, and a people bitterly suspicious of one another. In other words, it is also a novel about now.

Paperback - 3 Feb. 2022. London, Burning is a novel about the end of the 1970s, and the end of an era. It concerns a nation divided against itself, a government trembling on the verge of collapse, a city fearful of what is to come, and a people bitterly suspicious of one another. In other words, it is also a novel about now.

Kindle Edition. London, Burning is a novel about the end of the 1970s, and the end of an era. It concerns a nation divided against itself, a government trembling on the verge of collapse, a city fearful of what is to come, and a people bitterly suspicious of one another. In other words, it is also a novel about now.

The Amazon Book Review Book recommendations, author interviews, editors' picks, and more. Read it now. ... I have read most of Anthony Quinn's books and enjoyed them. London Burning gives us a great reminder of London just before Thatcher came to power - the days of multiple strikes, rubbish building up in the streets and so on. ...

4/5: Well written and atmospheric, this takes one back to the seventies and the febrile anticipation of the doomed election of 1978 when there was no right choice between Uncle Muddle and Mrs Kill. The story is intricately plotted, perhaps relying a bit much on coincidence at some points but the corruption in the Met seems just as relevant today as it would have been back then. Definitely ...

Nearly 30,000 Londoners had lost their lives and over 50,000 had been hospitalised by injury. The collectivism that had been 'woven into the fabric of every neighbourhood' had produced extraordinary bonds but, as White shows us in this masterful account, the city's recovery would take decades. The Battle of London 1939-45: Endurance ...

London 1945: Life in the Debris of War, by Maureen Waller (John Murray, £9.99) As the 60th anniversary of VE Day approaches, we are going to be exhorted to recall the efforts and sacrifices of ...

Find helpful customer reviews and review ratings for London, Burning at Amazon.com. Read honest and unbiased product reviews from our users.

London Burning, Portraits from a Creative City, by author and editor Hossein Amirsadeghi and executive editor Maryam Eisler, and published by Thames & Hudson, is hitting the bookstores on October ...

I thoroughly enjoyed reading London's Burning by Brent Towns. Multiple storylines kept me engaged in this action-packed suspense story. Other reviewers also mention that Mr. Towns is improving with each new book. Although this story leaves somewhat of a cliffhanger, I will purchase the next book to see how the final event turns out. Great job!

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time. Apologies to the late William Gass if I am misremembering, but I seem to recall him saying somewhere that the predominant literary ...

This is all captivating, terrifying stuff, especially through Vaillant's excellent telling. He has a penchant for finding stories of monomania: his first book, The Golden Spruce (2005), is about a logger turned crusading anti-logger who, in a confused act of ecoterrorism, chops down the titular tree—considered sacred by the indigenous Haida people—in British Columbia.

London's Burning by Theo Harris is book 4 in the Summary Justice series. The 24-carat gold and jewel encrusted eye patch goes under the hammer at Christie's for 500,000 pounds. This leads to an explosive chain of events. Kendra, Andy and Trevor bring criminals to justice in an unorthodox, and sometimes illegal, manner.

He puts all his faith and teenage angst into music - and his hero, Karl Williams, reminiscent of Morrissey from the Smiths. A series of bigoted comments get the singer-songwriter in trouble, and ...