Understanding Ethical Challenges in Medical Education Research

Affiliation.

- 1 R.L. Klitzman is professor of psychiatry and director, Masters of Bioethics Program, Columbia University, New York, New York.

- PMID: 34292193

- DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004253

Rapidly advancing biomedical and electronic technologies, ongoing health disparities, and new online educational modalities are all changing medicine and medical education. As medical training continues to evolve, research is increasingly critical to help improve it, but medical education research can pose unique ethical challenges. As research participants, medical trainees may face several risks and in many ways constitute a vulnerable group. In this commentary, the author examines several of the ethical challenges involved in medical education research, including confidentiality and the risk of stigma; the need for equity, diversity, and inclusion; genetic testing of students; clustered randomized trials of training programs; and questions about quality improvement activities. The author offers guidance for navigating these ethical challenges, including the importance of engaging with institutional review boards. Academic medical institutions should educate and work closely with faculty to ensure that all research adheres to appropriate ethical guidelines and regulations and should provide instruction about the ethics of medical education research to establish a strong foundation for the future of the field. Research on medical education will become increasingly important. Given the potential sensitivity of the data collected in such research, investigators must understand and address potential ethical challenges as carefully as possible.

Copyright © 2021 by the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Publication types

- Biomedical Research*

- Education, Medical*

- Educational Status

- Ethics Committees, Research

- Research Personnel

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- The ethics of medical...

The ethics of medical education

- Related content

- Peer review

- Reshma Jagsi , resident in radiation oncology 1 ,

- Lisa Soleymani Lehmann ( llehmann1{at}partners.org ) , instructor in medicine and medical ethics 2

- 1 Department of Radiation Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

- 2 Division of General Medicine and Primary Care, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 1620 Tremont Street, Boston, MA 02120-1613, USA

- Correspondence to: L S Lehmann

- Accepted 23 March 2004

Medical students and doctors in training need to hone their clinical skills on patients to make themselves better doctors, but patients may not benefit directly from such attention. Jagsi and Lehmann consider this ethical dilemma and suggest ways to minimise the potential harm to patients

Participation of trainees in patient care is an integral part of medical education. Although educating doctors is critical to society, an ethical dilemma results from the fact that patients may not benefit from doctors in training and medical students participating in their care, and may even be harmed by it. 1 2 However, this dilemma has received little attention—political, 3 institutional, 4 or academic. 5 6 Professional societies advise only generally, noting that participation should be voluntary without providing specific procedural requirements. As a result, patients may be misinformed about the qualifications and experience of their care givers. 7 This situation is objectionable in its own right, but it also provides a problematic example at a critical point during trainees' moral development.

In contrast, the ethics of medical research on human subjects have been the subject of much analysis and policy development. 8 A compelling analogy exists between such research and medical education. 9 10 In both cases doctors ask patients to participate in an endeavour whose primary aim is to benefit society as a whole, not the individual. In both cases doctors must also balance the good to society and potential benefit to individual participants against potential harm to those participants, avoid the unfair distribution of risks and benefits, and maintain respect for patient autonomy. Although education and research have different goals, their similarities are sufficient to allow for fruitful discussion based on this analogy.

Credit: FELDMAN/SPL STEPHEN

In this article we apply three principles of research ethics—respect for individuals, beneficence, and distributive justice—to medical education in order to review current practice and guide further research and policy.

Respect for individuals

Western philosophers have long argued that human beings have an inherent personal dignity that merits respect for its own sake. To use people only as a means to an end—as is the case when patients are the objects of medical education or research without meaningful consent—violates that fundamental principle.

Evidence suggests that the current practice of medical education does not always accord adequate respect to patients. In one US survey, only 38% of responding teaching hospitals claimed that they informed patients that students would be involved in their care. 11 Other studies show that students and their supervisors sometimes misrepresent or inadequately explain students' status. 12 Moreover, student conscientiousness about disclosing their status seems to decay over the course of training. 13 Patient surveys confirm that they receive inadequate information about trainees' roles. 14

Procedures to ensure meaningful consent from patients to participation in medical education are therefore necessary. Patients must be fully informed of the training status and experience of all staff caring for them and must comprehend the risks, benefits, and alternatives. The proximity of consent to individual procedures is crucial, and a “blanket” consent at admission is insufficient.

Beneficence

The principle of beneficence consists of a spectrum of obligations to promote welfare, ranging from the negative duty not to inflict harm to the positive duty to do good. Beneficence requires that, even before patients are asked to participate in research or education, doctors must first decide whether the overall balance of risks and benefits justifies requesting that participation. It also requires that doctors minimise risks. Understanding the nature and probability of risks and benefits is thus essential.

Both medical education and research are primarily directed at providing benefits to society as a whole. With research, society benefits from contributions to medical knowledge; with education, it benefits from the production of well trained doctors. Both medical education and research may also benefit participating individuals. Patients may benefit from participating in research by gaining access to experimental treatments and from closer follow up. Similarly, patients may benefit from closer attention when trainees participate in their care.

Studies have shown that patient satisfaction does not decrease when students participate in their medical care. Many patients are willing to allow students to participate in invasive procedures and pelvic examinations, 15 indicating that they may believe the balance of potential benefits to themselves and society outweigh the risks. Altruism, rather than perceived benefit to self, seems to be the primary motivation for participation in medical education. 16 Self interest may play a larger role in patients' motivations for participating in research than in the case of education, and this difference has important implications. While researchers may reasonably be bound by non-maleficence alone, educators bear a stricter positive duty to do good.

Few empirical data exist regarding potential hazards of participation in medical education. Research relating provider inexperience to patient outcomes, including the idea of a “July phenomenon” (increased patient morbidity and mortality linked with the influx of new medical trainees), has been inconclusive. 17 Because the goals and nature of education and research differ, it seems appropriate to require a higher threshold by which benefits should exceed risks in the case of education. Further research into outcomes of trainee participation is necessary to allow doctors to provide comprehensive information to patients regarding the risks and benefits they face. Such research could also be used to develop guidelines about the appropriate level of supervision for given classes of activity and levels of experience. Educators should also identify ways to minimise the risk of participation by inexperienced providers, such as increased reliance on advanced technological simulations. 18

Distributive justice

The burdens of medical education are not currently distributed fairly. In one US study, students saw disproportionately high numbers of non-white patients and patients with Medicaid (public insurance for the indigent). 19 Another study found that children of doctor parents were less likely to be seen by trainees than were other children. 20

Such disparities may exist because disadvantaged patients may not feel empowered to withhold consent. They may also exist because consultants assume that certain patients are likely to refuse and therefore do not ask them to participate. The lack of participation of trainees in the care of doctors' children is particularly troubling, for it indicates that those most informed about the true risks and benefits of the system of medical education are more likely to withhold consent. There is a tension between the three principles, as it is difficult to secure the societal benefit of medical education and maintain respect for patients who withhold consent without placing an unfair burden on disempowered groups.

Summary points

The current system of medical education, in which doctors in training and medical students participate in patient care, may expose patients to physical, psychological, and economic risks, often without their full consent

Few analyses of the ethics of trainee participation in patient care have been made, and policies are not well developed

The ethics of medical education can be informed by the ethics of research on human subjects

We provide a theoretical framework for ethical medical education by extending three key concepts from the literature of research ethics—respect for individuals, beneficence, and distributive justice

Within the framework provided by these concepts, we assess the current practice and effects of trainee participation in patient care and provide suggestions for policy development and further research

When socioeconomic constraints lead certain groups to participate in medical education because it is their only opportunity to obtain care, the principle of distributive justice is clearly violated. System-wide changes, including broadening the location of medical training to settings outside the wards of inner city hospitals and improving the access of disempowered groups to health care more generally, particularly in the United States, are necessary if the distribution of the benefits and burdens of medical education is to be truly just.

Medical educators have much to gain from research ethics. As in clinical research, patient participation should be guided by the principles of respect for individuals, beneficence, and justice. Systematic procedures are necessary to apply these principles to the practice of medical education. Professional organisations should give detailed guidelines, and teaching institutions must develop, in consultation with community members, effective mechanisms to ensure the ethical practice of medical education.

Some readers may cringe at the spectre of a new bureaucracy being created to implement these recommendations. The rapidly evolving nature of medical research and the wide variety of research proposals necessitate standing independent boards to conduct frequent reviews. Since the field of medical education has a well developed infrastructure, the application of these ethical principles should not entail substantial extra administrative burdens.

Just as there is a continuum between innovative practice and research, there is a continuum between practice and education, for medicine is a career of life-long learning. The principles discussed in this paper are applicable not only to medical trainees but may prove useful to junior doctors and even senior doctors attempting new procedures or practices.

The history of research ethics suggests that the medical profession should be proactive rather than reactive in approaching the ethics of medical education. The time has come for the profession to turn its attention to this important issue.

Contributors and sources: LSL had the initial idea for this article. The concepts were refined by dialogue between LSL and RJ. RJ did a Medline search from 1966 to the present, and both authors examined references cited in commonly used textbooks of medical ethics and clinical research ethics. Both authors reviewed the published literature. RJ wrote the first draft of the article, which was revised by LSL. LSL is guarantor for the article.

Funding This study was funded by the Harvard Medical School Division of Medical Ethics.

Competing interests None declared.

- Robertson DW ,

- Robinson DL ,

- Coldicott Y ,

- Basson MD ,

- Dworkin G ,

- Marracino RK ,

- McCullough LB ,

- Kessel RWI ,

- Apostolides AY ,

- Heiderich KJ ,

- Vinicky JK ,

- Connors RB Jr . ,

- Heiderich KJ

- Beatty ME ,

- Silver-Isenstadt A ,

- Benbow SJ ,

- Elizabeth J ,

- Williams CT ,

- Magrane D ,

- Gifford G ,

- Luxenberg M ,

- Butters JM ,

- Stange KC ,

- Diekema DS ,

- Cummings P ,

Ethics teaching in medical school: the perception of medical students

- original article

- Open access

- Published: 22 December 2022

- Volume 136 , pages 129–136, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Lorenz Faihs ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1824-0024 1 , 2 ,

- Carla Neumann-Opitz 1 ,

- Franz Kainberger 3 &

- Christiane Druml 4 , 5

2386 Accesses

3 Citations

Explore all metrics

In times of a pandemic, morals and ethics take center stage. Due to the challenges of the pandemic and ongoing discussions about the end of life, student teaching demands might have changed. This study aimed to evaluate teaching ethics, law, and decision-making skills in medical education via a survey to customize the curriculum to the students’ needs. Furthermore, gender differences were examined to determine gender equality in medical education.

The medical students at the Medical University of Vienna were requested to complete an anonymous online survey, providing feedback on the teaching of ethics, law, and decision-making skills.

Our study showed the students’ strong demand for more teaching of ethics, law, and decision-making skills. Moreover, we found that students were afraid to encounter ethical and moral dilemmas. Gender differences could be found, with female students assessing their knowledge and the teaching as being more insufficient, resulting in greater fear of encountering ethical and moral dilemmas.

The fear of encountering ethical and moral dilemmas might be linked to medical students’ self-perceived insufficient legal knowledge. The education should guarantee gender equality in medical training and be customized to the students to provide the future doctors with the ethical and legal expertise to preserve the patient’s rights and protect their mental health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Must we remain blind to undergraduate medical ethics education in Africa? A cross-sectional study of Nigerian medical students

Onochie Okoye, Daniel Nwachukwu & Ferdinand C. Maduka-Okafor

What Do Students Perceive as Ethical Problems? A Comparative Study of Dutch and Indonesian Medical Students in Clinical Training

Amalia Muhaimin, Derk Ludolf Willems, … Maartje Hoogsteyns

The state of ethics education at medical schools in Turkey: taking stock and looking forward

Mustafa Volkan Kavas, Yesim Isil Ulman, … Nadi Bakırcı

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Medical knowledge and skills are undoubtedly the basis of medical education; however, with every medical decision, various aspects must be considered. Among these are ethics, morality, and legal factors, which also play a significant role in the everyday working life of a doctor. At the beginning of the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, with scarce resources and limited knowledge about the disease, doctors faced difficult decisions that may often contradict their personal ethical and moral principles. These personal ethical or moral code violations might lead to adverse psychological effects, such as a moral injury [ 1 ]. The symptoms include negative thoughts about oneself, such as shame, guilt, or disgust, which can lead to further mental health issues [ 2 ].

Doctors must train their intellectual and emotional capacity to develop an ethical preparedness to make decisions in times of crisis [ 3 ]. Medical schools should provide future doctors with the tools to face these difficult situations by integrating the education of medical ethics and the legal background vertically and horizontally in their curriculum [ 4 ].

The medical ethics curricula, their structural preconditions and the respective academic course hours vary substantially between medical schools [ 5 , 6 ]. UNESCO created a bioethics core curriculum, which covers the core contents of the bioethical principles of the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights [ 7 ]. Furthermore, the World Medical Association Ethics Unit published a Medical Ethics Manual to provide a “universally used curriculum for the teaching of medical ethics” [ 8 ].

At the Medical University of Vienna, bioethics is taught primarily in the public health module in the fourth year, which consists of 12 academic hours. The teaching has an interdisciplinary approach based on four points of view: ethics in the healthcare system, ethical issues in the doctor-patient relation, ethical aspects at the end of life and in palliative care, ethnomedicine and ethical aspects of the interculturality [ 9 ].

The way knowledge is tested at the Medical University of Vienna mainly consists of a summative, integrated examination (SIP), a written multiple choice test at the end of each academic year. Haidinger et al. revealed that female students showed less confidence in success before taking this examination [ 10 ]. Furthermore, past studies showed that female students perceive their skills and knowledge as inferior, although they end up being equal to their male colleagues [ 11 , 12 ]. Through our study, we aimed to evaluate if a gender difference can also be found regarding the assessment and the opinions about bioethics.

Past studies have evaluated ethical competence and the students’ awareness of and attitudes towards medical ethics [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ]; however, due to the ongoing changes in moral concepts and the current pandemic with its concomitant ethical and moral dilemmas, the students’ perception of the teaching of ethics and morals might also have evolved. We sought to assess the student’s evaluation of ethics teaching in medical education with a particular focus on the ethical and moral aspects of a pandemic and end of life issues as well as the corresponding legal background. Furthermore, we wanted to survey the students’ awareness of ethical topics, their wishes, and preferences for a better education in bioethics and to evaluate if there are any differences in opinion between genders. The findings of this study can contribute to understanding the students’ needs, wishes, and fears regarding their future working life and improve ethics teaching in medical education by implementing the results in the medical curricula.

Medical students at the Medical University of Vienna were asked to give feedback on the ethics curriculum in an online survey. The anonymous questionnaire was embedded in the Moodle course of the lecture line interdisciplinary case conferences in which all students ( n = 662) of the ninth semester were enrolled. The prescribed course covers ethical and moral aspects of medicine among other topics and therefore provides a good opportunity to ask for feedback regarding the survey’s topics. This cohort of students finished ethical teaching in medical school after an emphasis on bioethics in the fourth year. They will soon be confronted with moral and ethical dilemmas with the start of their clinical training in their elective work in the sixth year. We decided to conduct the survey through an online questionnaire in German to reach as many students as possible. Completing the online questionnaire was voluntary and anonymous; there were no consequences if the students did not participate in the survey. We refused to ask for age and other demographic data besides gender to preserve the anonymity of the participants.

After consultation with the intrauniversity data protection and ethics committee of the Medical University of Vienna, no formal approval was needed for this voluntary and totally anonymous online survey.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed with the input of all authors and adapted to focus on the quality of ethics teaching at the Medical University of Vienna. It included 17 statements with a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly agree to 6 = strongly disagree, 2 multiple choice questions (including the question of gender), and 1 open question (I would like an increased emphasis on ethical and moral aspects during medical school in the following topics). We grouped the questions and statements in four subchapters: firstly, the assessment of the education of ethics, morals, and the legal aspects, secondly, pandemics and the current COVID-19 situation, thirdly, end of life and lastly, the preferences for medical ethics curriculum.

Data analysis

Statistical Analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics 27 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The responses to the open question were grouped into 20 categories to allow statistical analysis. As the data were non-normally distributed, the median and interquartile range (IQR) were given. For the comparison of responses by gender, a Mann-Whitney U‑test was performed; for the comparison of the answers of two questions, a Wilcoxon test was used. Bivariate correlations were analyzed with the Spearman rank correlation. A p -value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. No multiple comparison adjustments were performed; p -values should be interpreted as exploratory only.

With 662 actively enrolled students in the Moodle course interdisciplinary case conferences in January of 2021, 283 questionnaires were completed, resulting in a response rate of 42.8%. The majority of respondents identified themselves as female (59.1%, n = 133), 39.6% ( n = 89) as male, and 1.3% ( n = 3) as non-binary ( n = 58 missing data).

Correlations are only mentioned for significantly correlating responses.

Assessment of ethics teaching

Table 1 provides an overview of the assessment of ethics teaching by the students. It shows the frequency of the answers the students provided. The most frequently marked answer was highlighted in italic text for each question. Firstly, students tended to think that ethics and morals are sufficiently covered in medical school (IQR = 2–4, median 3 = slightly agree). Nevertheless, the students did not think physicians and professors took enough time to discuss ethical and moral issues with students (IQR = 3–5, median 4 = slightly disagree).

In contrast to the assessment of ethics and morals teaching, the legal aspects of ethical and moral issues were regarded as not sufficiently covered in medical school (IQR = 3–5, median 4 = slightly disagree). Furthermore, the prospective doctors mostly did not think they had sufficient legal knowledge to handle ethical and moral dilemmas (IQR = 3–5, median 4 = slightly disagree). The difference between the assessment of ethics and morals teaching and the teaching of legal aspects was statistically significant ( p < 0.001). While most participants felt sufficiently prepared to make a decision in the event of an ethical or moral dilemma (IQR = 2–4, median 3 = slightly agree), nearly half (48.1%) of the students slightly, mostly, or strongly disagreed. Concerning the teaching of decision-making skills, most students thought that this subject was not sufficiently taught in medical school (IQR = 3–4, median 4 = slightly disagree). Finally, most students were afraid to encounter ethical and moral dilemmas in their future professional life, as 66.0% responded that they at least slightly agree (IQR = 2–4, median 3 = slightly agree). The responses correlate positively with the answers to the question “I think that physicians are often confronted with ethical and moral dilemmas in their professional life” (Spearman’s Rho = 0.19, p = 0.002), and there is an inverse correlation to the answers to the questions “I think that decision-making skills are sufficiently taught in medical school” (Spearman’s Rho = −0.13, p = 0.036) and “I feel sufficiently prepared to make a decision in the event of an ethical or moral dilemma” (Spearman’s Rho = −0.35, p < 0.001).

Table 2 presents the results of the questions concerning pandemics. Most students felt prepared to make ethical and moral decisions during a pandemic (IQR = 2–4, median 3 = slightly agree) and were not afraid to deal with ethical and moral dilemmas in these times (IQR = 2–5, median 4 = slightly disagree); however, the participants stated that they were often worried about ethical and moral issues during the COVID-19 pandemic (IQR = 2–3, median 2 = mostly agree). Finally, students wanted more intense teaching on the ethical and moral issues during a pandemic (IQR = 1–3, median 2 = slightly agree).

End of life

Table 3 gives an overview of the questions regarding the end of life. On the one hand, most of the participants felt prepared to deal with end of life dilemmas of patients as a physician (IQR = 2–4, median 3 = slightly agree) and were not afraid of having to deal with these dilemmas in their professional life (IQR = 2–5, median 4 = slightly disagree). On the other hand, the students did not think that they have sufficient legal knowledge to deal with end of life issues in their professional life (IQR = 3–5, median 4 = slightly disagree) and would have liked to have broader teaching on the ethical and moral issues of the end of life (IQR = 1–3, median 2 = mostly agree).

Gender differences

We evaluated the gender-specific differences of the responses. Most participants identified themselves as female (59.1%, n = 133), 39.6% ( n = 89) as male. Due to the small, nonrepresentative sample size of participants who identified themselves as non-binary ( n = 3), these questionnaires were excluded from the analysis.

Moreover, the responses of the 59 participants (20.5%) who did not specify their gender could not be implemented in the analysis.

Table 4 presents each question’s gender differences with the mean and median of both genders. The questions with statistically significant differences are in italic text and were marked as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Female students felt that ethics and morals as well as the legal aspects, were not sufficiently covered in medical school even more than the male students. They also assessed their legal knowledge to be more limited than their male colleagues. Moreover, the female participants felt less prepared to decide in the event of an ethical or moral dilemma and were afraid to encounter ethical and moral dilemmas in their future professional lives. Furthermore, they believed even more strongly that decision-making skills were not sufficiently taught in medical school and had a greater wish for more emphasis on ethics and morals in the curriculum than their male fellow students. Not only could a difference be found in the assessment of ethics teaching, but also the responses to the questions concerning pandemics. Female students felt less prepared to make ethical and moral decisions during a pandemic and had a greater fear of dealing with ethical and moral dilemmas in their professional life as a physician in times of a pandemic. Additionally, they worried even more about ethical and moral issues during the COVID-19 pandemic and had a stronger wish for broader teaching of ethical and moral aspects in times of a pandemic. Finally, the female participants felt less prepared to deal with dilemmas regarding end of life in their professional life as a physician, were more fearful of having to deal with end of life issues in their professional life as a physician and would have liked to have even more intense teaching of the ethical and moral issues at the end of life than their male colleagues.

Preferences for medical ethics curriculum

Finally, we asked for the students’ wishes for ethics and morals teaching in the medical curriculum.

Table 5 presents the responses of the students to this question. Most students would have liked more emphasis on these topics (IQR 2, median 2 = mostly agree). The answers to this question showed a positive correlation to the responses to “I am afraid to encounter ethical and moral dilemmas in my future professional life” (Spearman’s Rho = 0.30, p < 0.001).

Next, we asked the students in which context they wanted an increased emphasis on ethics and morals. For this question, a selection of several answers was possible. The majority of students would have liked more teaching within the framework of case reports (70.7%), followed by discussions (62.5%), seminars in study groups (59%), lectures (30.4%), optional subjects (22.3%) and only 1.4% answered with “none”.

In the end, the students were asked about the topics on which they would like a deeper focus on the ethical and moral aspects during medical school in an open question. The most frequent answers were end of life/palliative care ( n = 45), legal aspects ( n = 23), health system/distribution of resources/influence of the economy ( n = 12), general background/history of medicine ( n = 12), and psychiatry ( n = 10).

In light of the results of our study, we conclude that it is essential to emphasize the importance of bioethics as an integral part of medical education.

Past studies have shown medical students’ positive attitudes towards bioethics [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ]. Interestingly, the results of our study show that the students were afraid to encounter ethical and moral dilemmas. This fear might stem from the awareness that decisions have consequences for the decision maker as well as the patients and families involved. The fear of encountering ethical and moral dilemmas might be tied to the feeling that the law is inadequately covered, as legal decisions can have serious professional and personal consequences.

This fear can also be found at the patients’ end of life, where futile life-sustaining treatment prolongs the life of patients. One of the reasons for this futility is the hesitance and inability of some doctors to decide due to their fear of legal consequences [ 22 , 23 ]. Law should be a compulsory component of the curriculum of every medical school, providing the future doctors with the essential skills to make decisions in difficult situations.

Medical law is undoubtedly linked to bioethics and morality and forms the framework for decision making [ 24 ]. Laws are norms of specific ethical values that define the consensus of individuals’ social behavior in a community. Comprehensive ethical and moral training might not be enough to remove the fear of encountering dilemmas from the students, as law and ethics may diverge. The difficulty of deciding if something is legal because it is right or right because it is legal goes back as far as the ancient philosopher Plato in the Euthyphro dilemma [ 25 ].

Female students felt more afraid of dealing with ethical and moral dilemmas in their future professional life than male students and expressed a more significant wish for a deeper teaching of ethics. Similar results describing a greater demand from female students for broader ethics teaching were found in a study by Lehrmann et al. among medical students at the University of Mexico [ 20 ]. Furthermore, a survey of AlMahmoud et al. revealed that women endorsed the aims of ethics teaching more strongly [ 18 ]. Past studies showed that women were less confident in their knowledge and skills than their male colleagues [ 11 , 12 , 26 , 27 ]. These differences in self-assessment might be a reason for the heightened demand for more ethics teaching by women and is likely to be an unconscious wish by men. To compensate for the gender differences, more gender-sensitive teaching in general and female role models in medical schools might help.

The students’ wish for a greater emphasis on ethics and morality in medical education could be found throughout all subtopics of our study. Over 90% of the students did at least slightly agree that they would have liked a greater emphasis on the teaching of ethics and morality in medical school.

Ethics and morality can be implemented in the curriculum in different ways. The participants of our study desired more intense teaching, especially in the framework of case reports (70.7%), discussions (62.5%), and seminars in study groups (59%). Past surveys attained similar results. In a survey at the Medical College of Georgia in 2018, among the most popular educational components for graduate level medical ethics, ethics case-based discussions (80.7%) and ethics discussions in small peer groups (62.7%) can be found [ 19 ]. Furthermore, among the five most desired methods for teaching ethics in a survey conducted in 2009–2013 at the United Arab Emirates University, case conferences, clinical rounds, and discussion groups of peers led by a knowledgeable clinician were mentioned [ 18 ]. Generally, integrated ethics education in medical curricula should be student centered and include problem-based teaching [ 28 ].

This study has potential limitations. One possible limitation of this study is its potential lack of generalizability, as the survey was conducted at one single medical school in Austria. Furthermore, the high percentage (20.5%) of missing data for the comparison of responses by gender might bias the results. Missing values are often unavoidable in research. Data missing not at random might result in a biased estimate of effect [ 29 ]. Finally, the data reflect the students’ opinions and self-assessment but cannot provide an objective assessment of their knowledge of ethics, morality, and medical law.

Medical students will encounter various ethical, moral, and legal problems in their future professional lives. The COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing discussions and legal changes concerning the end of life pose extreme challenges to healthcare workers. Solid training in ethics, morals, and medical law is indispensable to deal with these issues.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights of the United Nations, which states an ideal of ethical standards, demands that “every organ of the society shall strive by teaching and educating to promote respect for these rights and freedoms” [ 30 ]. Furthermore, the World Medical Association demanded in its 51st World Medical Assembly in Tel Aviv in 1999 that “the teaching of medical ethics should become obligatory and be examined as part of the medical curriculum within every medical school” [ 31 ]. In response, in 2004, UNESCO established the Ethics Education Programme to support and foster ethics education in member states. Consequently, at the Medical University of Vienna, a Chair of Bioethics has been established as an institution responsible for bioethics education, ethical issues research and gender equality [ 32 ].

Implementing the students’ wishes in the curriculum pays off [ 33 ]. Ethics education should be customized to the students and the challenges they will encounter in their future professional life [ 34 ].

Basic knowledge of ethical principles is not sufficient for professional challenges. Extensive ethical and legal training during and after medical school is crucial to preserve patient rights, improve patient care quality and maintain healthcare workers’ mental health.

Murray E, Krahé C, Goodsman D. Are medical students in prehospital care at risk of moral injury? Emerg Med J. 2018;35:590–5594. http://emj.bmj.com/content/35/10/590.abstract .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Greenberg N, Docherty M, Gnanapragasam S, Wessely S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368:m1211.

Druml C. COVID-19 and ethical preparedness? Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2020;132(13-14):400–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-020-01709-7 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Stirrat GM, Johnston C, Gillon R, Boyd K; Medical Education Working Group of Institute of Medical Ethics and associated signatories. Medical ethics and law for doctors of tomorrow: the 1998 Consensus Statement updated. J Med Ethics. 2010;36(1):55–60. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2009.034660 .

Schildmann J, Bruns F, Hess V, Vollmann J. “History, Theory and Ethics of Medicine”: The Last Ten Years. A Survey of Course Content, Methods and Structural Preconditions at Twenty-nine German Medical Faculties. GMS J Med Educ. 2017;34(2):Doc23. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma001100 .

Bobbert M. 20 Jahre Ethikunterricht im Medizinstudium: Eine erneute Lehrziel- und Curriculumsdiskussion ist erforderlich. Ethik Med. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00481-012-0216-6 .

Article Google Scholar

UNESCO. Ethics Education Programme. Bioethic Core Curriculum—Section I—Syllabus: Ethics Education Programme. 2008. p. 71.

Google Scholar

Medical Ethics Manual – WMA – The World Medical Association. https://www.wma.net/what-we-do/education/medical-ethics-manual/ . Accessed: 9 Dec 2022.

Hofhansl A, Rieder A, Dorner TE. Ethik im Medizincurriculum Wien fest etabliert [Medical ethics is well established in the Undergraduate Medical Curriculum Vienna]. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2015;165(5-6):98-9. German. doi: 10.1007/s10354-015-0342-0.

Haidinger G, Mitterauer L, Rimroth E, Frischenschlager O. Lernstrategien oder strategisches Lernen? Gender-abhängige Erfolgsstrategien im Medizinstudium an der Medizinischen Universität Wien [Learning strategy or strategic learning? Gender-dependent success in medical studies at the Medical University of Vienna]. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2008;120(1-2):37–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-007-0923-z .

Miller KA, Monuteaux MC, Roussin C, Nagler J. Self-confidence in endotracheal Intubation among pediatric interns: associations with gender, experience, and performance. Acad Pediatr. 2019;19:822–7.

Madrazo L, Lee CB, McConnell M, Khamisa K. Self-assessment differences between genders in a low-stakes objective structured clinical examination (OSCE). BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:393.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Saad TC, Riley S, Hain R. A medical curriculum in transition: audit and student perspective of undergraduate teaching of ethics and professionalism. J Med Ethics. 2017;43:766–70. http://jme.bmj.com/content/43/11/766.abstract .

Schulz S, Woestmann B, Huenges B, Schweikardt C, Schäfer T. How important is medical ethics and history of medicine teaching in the medical curriculum? An empirical approach towards students’ views. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2012;29(1):Doc08. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma000778 .

Chin JJ, Voo TC, Karim SA, Chan YH, Campbell AV. Evaluating the effects of an integrated medical ethics curriculum on first-year students. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2011;40(1):4–18.

MacPherson CC, Veatch RM. Medical student attitudes about bioethics. Cambridge quarterly of healthcare ethics. Vol. 19. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2010. p. 496.

Eckles RE, Meslin EM, Gaffney M, Helft PR. Medical ethics education: Where are we? Where should we be going? A review. Acad Med. 2005;80:1152.

AlMahmoud T, Hashim MJ, Elzubeir MA, Branicki F. Ethics teaching in a medical education environment: preferences for diversity of learning and assessment methods. Med Educ Online. 2017;22:1328257.

DeFoor MT, Chung Y, Zadinsky JK, Dowling J, Sams RW 2nd. An interprofessional cohort analysis of student interest in medical ethics education: a survey-based quantitative study. BMC Med Ethics. 2020;21:26.

Lehrmann JA, Hoop J, Hammond KG, Roberts LW. Medical students’ affirmation of ethics education. Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33:477.

Roberts LW, Warner TD, Hammond KAG, Geppert CMA, Heinrich T. Becoming a good doctor: perceived need for ethics training focused on practical and professional development topics. Acad Psychiatry. 2005;29:309.

Albisser Schleger H, Pargger H, Reiter-Theil S. Futility – Übertherapie am Lebensende? Gründe für ausbleibende Therapiebegrenzung in Geriatrie und Intensivmedizin. Palliativmedizin. 2008;9:75.

Druml W, Druml C. Übertherapie in der Intensivmedizin [Overtreatment in intensive care medicine]. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2019;114(3):194–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00063-019-0548-9 .

Foster C, Miola J. Who’S in charge? The relationship between medical law, medical ethics, and medical morality? Med Law Rev. 2015;23:530.

Misselbrook D. The Euthyphro dilemma. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:263–263. https://bjgp.org/content/63/610/263 .

Corfield L, Williams RA, Lavelle C, Latcham N, Talash K, Machin L. Prepared for practice? UK Foundation doctors’ confidence in dealing with ethical issues in the workplace. J Med Ethics. 2020. http://jme.bmj.com/content/early/2020/04/09/medethics-2019-105961.abstract . https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2019-105961 .

Faihs V, Figalist C, Bossert E, Weimann K, Berberat PO, Wijnen-Meijer M. Medical students and their perceptions of digital medicine: a question of gender? Med Sci Educ. 2022;32:941–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-022-01594-x .

Afshar L. Comparative study of medical ethics curriculum in general medicine course in 10selected universities in the world. J Med Educ. 2019. https://doi.org/10.22037/jme.v18i1.23781 .

Mack C, Su Z, Westreich D. Types of missing data. Agency for healthcare research and quality (US). 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493614/ . Accessed 13 Oct 2022.

Assembly UNG. Universal declaration of human rights. Vol. 302. New York: UN General Assembly; 1948. pp. 14–25.

World Medical Association. WMA resolution on the inclusion of medical ethics and human rights in the curriculum of medical schools world-wide. 1999. pp. 1–2.

Druml C. Bioethics internationally and in Austria: A sense of solidarity. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2016;128(7-8):229–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-016-1000-2 .

Milles LS, Hitzblech T, Drees S, Wurl W, Arends P, Peters H. Student engagement in medical education: a mixed-method study on medical students as module co-directors in curriculum development. Med Teach. 2019;41:1150.

Singer PA, Pellegrino ED, Siegler M. Clinical ethics revisited. BMC Med Ethics. 2001;2:E1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-2-1 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank the students of the Medical University of Vienna for their participation in the feedback.

The authors received no funding or financial compensation for their study and manuscript work.

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Vienna.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Lorenz Faihs & Carla Neumann-Opitz

Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Experimental and Clinical Traumatology, Vienna, Austria

Lorenz Faihs

Division of Neuro- and Musculoskeletal Radiology, Department of Biomedical Imaging and Image-Guided Therapy, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Franz Kainberger

Unesco Chair on Bioethics at the Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Christiane Druml

Department of Ethics, Collections, and History of Medicine (Josephinum), Vienna, Austria

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lorenz Faihs .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

L. Faihs, C. Neumann-Opitz, F. Kainberger and C. Druml declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Availability of data

The automatically generated dataset by the learning platform Moodle is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Data protection and consent to participate

The completion of the online feedback was voluntary and anonymous, as were the other weekly feedbacks on the learning platform Moodle. The feedback was orally explained during the online lecture on interdisciplinary case conferences, which all ninth semester students had to attend. The approval of the intrauniversity data protection commission to publish the data of the online feedback was granted. The data were collected anonymously with the feedback tool on Moodle. Due to the anonymization and the high response rate, it is impossible to identify which students completed the questionnaire. Therefore, we did not ask for the age of the students since it would not benefit the study results. The students had the opportunity to contact the student secretariat for questions and inquiries.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Faihs, L., Neumann-Opitz, C., Kainberger, F. et al. Ethics teaching in medical school: the perception of medical students. Wien Klin Wochenschr 136 , 129–136 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-022-02127-7

Download citation

Received : 31 August 2022

Accepted : 13 November 2022

Published : 22 December 2022

Issue Date : March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-022-02127-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Medical ethics

- Healthcare ethics

- Ethics education

- Ethics curriculum

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Home / Education / Alden March Bioethics Institute

Alden March Bioethics Institute

Doctorate of professional studies.

- Master of Science in Bioethics

- Dual Degree Programs

- Graduate Certificate Programs

- Bioethics Fellowship

- Better Doctoring

Enhance Your Career

Our mission, browse degree programs.

- Doctorate of Professional Studies Bioethics

Related Events

Ethics grand rounds, albany medical college, interested.

Request more information.

Find out more about the application process.

Not a student? Find information for:

Medical students’ and educators’ opinions of teleconsultation in practice and undergraduate education: a UK-based mixed-methods study

- Find this author on Google Scholar

- Find this author on PubMed

- Search for this author on this site

- ORCID record for Lisa-Christin Wetzlmair

- ORCID record for Andrew O'Malley

- For correspondence: [email protected]

- Info/History

- Preview PDF

Introduction: As information and communication technology continues to shape the healthcare landscape, future medical practitioners need to be equipped with skills and competencies that ensure safe, high-quality, and person-centred healthcare in a digitised healthcare system. This study investigated undergraduate medical students’ and medical educators’ opinions of teleconsultation practice in general and their opinions of teleconsultation education. Methods: This study used a cross-sectional, mixed-methods approach, utilising the additional coverage design to sequence and integrate qualitative and quantitative data. An online questionnaire was sent out to all medical schools in the UK, inviting undergraduate medical students and medical educators to participate. Questionnaire participants were given the opportunity to take part in a qualitative semi-structured interview. Descriptive and correlation analyses and a thematic analysis were conducted. Results: A total of 248 participants completed the questionnaire and 23 interviews were conducted. Saving time and the reduced risks of transmitting infectious diseases were identified as common advantages of using teleconsultation. However, concerns about confidentiality and accessibility to services were expressed by students and educators. Eight themes were identified from the thematic analysis. The themes relevant to teleconsultation practice were (1) The benefit of teleconsultations, (2) A second-best option, (3) Patient choice, (4) Teleconsultations differ from in-person interactions, and (5) Impact on the healthcare system. The themes relevant to teleconsultation education were (6) Considerations and reflections on required skills, (7) Learning and teaching content, and (8) The future of teleconsultation education. Discussion: The results of this study have implications for both medical practice and education. Patient confidentiality, safety, respecting patients’ preferences, and accessibility are important considerations for implementing teleconsultations in practice. Education should focus on assessing the appropriateness of teleconsultations, offering accessible and equal care, and developing skills for effective communication and clinical reasoning. High-quality teleconsultation education can influence teleconsultation practice.

Competing Interest Statement

The authors have declared no competing interest.

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Author Declarations

I confirm all relevant ethical guidelines have been followed, and any necessary IRB and/or ethics committee approvals have been obtained.

The details of the IRB/oversight body that provided approval or exemption for the research described are given below:

Data collection was initiated after the initial ethics approval received from the School of Medicine at the University of St Andrews (approval code MD15263). Additional approval and permission to undertake the research was provided by the UK Medical Schools Council (MSC), and individual UK medical schools upon request.

I confirm that all necessary patient/participant consent has been obtained and the appropriate institutional forms have been archived, and that any patient/participant/sample identifiers included were not known to anyone (e.g., hospital staff, patients or participants themselves) outside the research group so cannot be used to identify individuals.

I understand that all clinical trials and any other prospective interventional studies must be registered with an ICMJE-approved registry, such as ClinicalTrials.gov. I confirm that any such study reported in the manuscript has been registered and the trial registration ID is provided (note: if posting a prospective study registered retrospectively, please provide a statement in the trial ID field explaining why the study was not registered in advance).

I have followed all appropriate research reporting guidelines, such as any relevant EQUATOR Network research reporting checklist(s) and other pertinent material, if applicable.

Data Availability

Research data underpinning the PhD thesis are available from 9 May 2028 at https://doi.org/10.17630/84eb74f3-e316-4618-a112-19b2f24377ac

https://doi.org/10.17630/84eb74f3-e316-4618-a112-19b2f24377ac

View the discussion thread.

Thank you for your interest in spreading the word about medRxiv.

NOTE: Your email address is requested solely to identify you as the sender of this article.

Citation Manager Formats

- EndNote (tagged)

- EndNote 8 (xml)

- RefWorks Tagged

- Ref Manager

- Tweet Widget

- Facebook Like

- Google Plus One

Subject Area

- Medical Education

- Addiction Medicine (315)

- Allergy and Immunology (617)

- Anesthesia (159)

- Cardiovascular Medicine (2269)

- Dentistry and Oral Medicine (279)

- Dermatology (201)

- Emergency Medicine (369)

- Endocrinology (including Diabetes Mellitus and Metabolic Disease) (798)

- Epidemiology (11559)

- Forensic Medicine (10)

- Gastroenterology (676)

- Genetic and Genomic Medicine (3560)

- Geriatric Medicine (336)

- Health Economics (615)

- Health Informatics (2297)

- Health Policy (912)

- Health Systems and Quality Improvement (860)

- Hematology (334)

- HIV/AIDS (748)

- Infectious Diseases (except HIV/AIDS) (13133)

- Intensive Care and Critical Care Medicine (755)

- Medical Education (358)

- Medical Ethics (100)

- Nephrology (388)

- Neurology (3341)

- Nursing (191)

- Nutrition (506)

- Obstetrics and Gynecology (650)

- Occupational and Environmental Health (643)

- Oncology (1753)

- Ophthalmology (524)

- Orthopedics (208)

- Otolaryngology (284)

- Pain Medicine (223)

- Palliative Medicine (66)

- Pathology (437)

- Pediatrics (999)

- Pharmacology and Therapeutics (419)

- Primary Care Research (402)

- Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology (3050)

- Public and Global Health (5980)

- Radiology and Imaging (1217)

- Rehabilitation Medicine and Physical Therapy (712)

- Respiratory Medicine (809)

- Rheumatology (367)

- Sexual and Reproductive Health (348)

- Sports Medicine (315)

- Surgery (386)

- Toxicology (50)

- Transplantation (170)

- Urology (142)

- Study Protocol

- Open access

- Published: 26 March 2024

The effect of a midwifery continuity of care program on clinical competence of midwifery students and delivery outcomes: a mixed-methods protocol

- Fatemeh Razavinia ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6827-509X 1 , 2 ,

- Parvin Abedi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6980-0693 3 ,

- Mina Iravani ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8854-1738 4 ,

- Eesa Mohammadi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6169-9829 5 ,

- Bahman Cheraghian ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5446-6998 6 ,

- Shayesteh Jahanfar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6149-1067 7 &

- Mahin Najafian ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6649-3931 8

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 338 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

113 Accesses

Metrics details

The midwifery continuity of care model is one of the care models that have not been evaluated well in some countries including Iran. We aimed to assess the effect of a program based on this model on the clinical competence of midwifery students and delivery outcomes in Ahvaz, Iran.

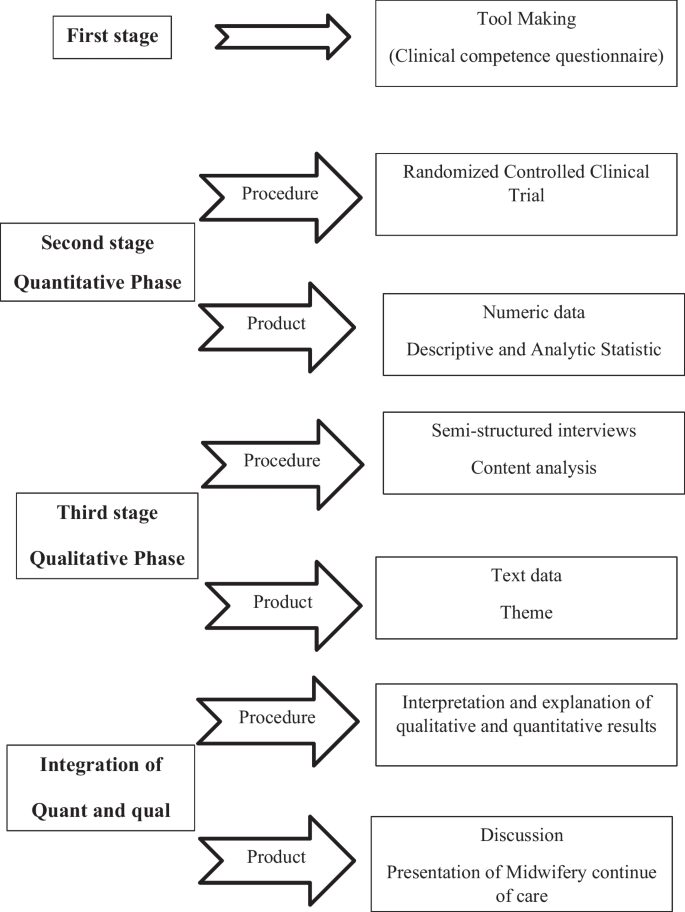

This sequential embedded mixed-methods study will include a quantitative and a qualitative phase. In the first stage, based on the Iranian midwifery curriculum and review of seminal midwifery texts, a questionnaire will be developed to assess midwifery students’ clinical competence. Then, in the second stage, the quantitative phase (randomized clinical trial) will be conducted to see the effect of continuity of care provided by students on maternal and neonatal outcomes. In the third stage, a qualitative study (conventional content analysis) will be carried out to investigate the students’ and mothers’ perception of continuity of care. Finally, the results of the quantitative and qualitative phases will be integrated.

According to the nature of the study, the findings of this research can be effectively used in providing conventional midwifery services in public centers and in midwifery education.

Trial registration

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (IR.AJUMS.REC.1401.460). Also, the study protocol was registered in the Iranian Registry for Randomized Controlled Trials (IRCT20221227056938N1).

Peer Review reports

Providing quality services to pregnant women has been recommended to all countries to achieve the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (Goals 3, 4 and 5) [ 1 ]. There are different care methods to maintain maternal and neonatal health during pregnancy and postpartum [ 1 ]. One of these care models is continuity of care that can be provided by a midwife or an obstetrician.

Midwifery continuity of care is a relationship-based care provided by a midwife who can be supported by one to three more midwives. They provide planned care for a woman during pregnancy, labor, birth, and the early postpartum period up to 6 weeks after delivery [ 2 ].

Continuity of midwifery care has become a global effort to enable women to have access to high-quality maternity care and delivery services [ 3 ]. As a result, many service providers today are transitioning to a continuous care model [ 4 ], and they have considered continuous care to be necessary for realizing women's rights [ 5 ]. Also, continuous midwifery care is known as the gold standard in maternity care to achieve excellent results for women [ 5 , 6 ]. In order to strengthen midwifery services to achieve global health goals in 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed a midwife-led continuous care model [ 7 ].

Countries use different midwifery care models. In Iran, for example, primary health services that are specific to pregnant mothers are provided in public health centers by midwives working in the network system and in compliance with the level of services and the referral system [ 8 ].

In general, midwifery continuous care not only has an important impact on a wide range of health and clinical outcomes for mothers and neonates but also brings about economic consequences for the health system [ 2 , 9 ]. This care model is useful for healthcare professionals as well [ 10 ], and it has improved the job satisfaction of midwives [ 11 ]. The midwife is the main guide in planning, organizing and providing care to a woman from the beginning of pregnancy to the postpartum period [ 12 ]. In 2011, in order to increase job motivation and satisfaction, promote retention of the midwifery workforce [ 13 ], and alleviate the shortage of workforce at the international level [ 14 ], the Nursing and Midwifery Advisory Center recommended using midwifery students (at the bedside and to perform midwifery work) to overcome this problem.

Providing high quality care requires enhancing the clinical competence of the professionals [ 4 ]. There is a close relationship between the concept of patient care quality and clinical competence. Therefore, clinical competence is of unique importance in midwifery practice [ 15 ]. As a result, in order to achieve quality patient care, midwifery professionals need to train students to become workforce with clinical competence in order to provide quality care in the health system. WHO defined clinical competence as a level of performance that demonstrates the effective application of knowledge, skills, and judgment [ 16 ].

A previous study showed that clinical competence of midwives plays an important role in managing the process of providing care, achieving care goals, and improving the quality of midwifery services [ 17 ]. In other words, the graduates of this field must have an acceptable level of clinical and professional skills in performing midwifery duties so that the health of mothers, children, and ultimately the community can be improved.

In Iran, prenatal care and the care during labor, delivery and postpartum are not continuous, and a new health provider may take the responsibility of care at any stage. This fragmented care may negatively affect the pregnancy outcomes and increase the rate of cesarean section [ 18 ]. Furthermore, the results of some studies in Iran indicate that the clinical competence obtained by midwifery students is far from optimal and that they do not acquire the necessary skills and abilities at the end of their studies [ 19 ]. Farrokhi et al. showed that the performance quality of 70% of midwives is average, and only 18.5% of them have good quality performance [ 20 ]. Several factors play a role in acquiring, maintaining and improving clinical competence [ 21 ]. There are a number of solutions that can increase the clinical competence of midwifery students, and one is the use of different care models such as the continuity of care model. The continuity of care model allows students to develop their midwifery knowledge, skills, and values individually [ 22 ]. Despite the strong foundation of midwifery in Iran, midwifery care models have not yet been tested. Some studies have reported that the quality of services provided during pregnancy, delivery and after delivery in Iran is poor to moderate. Also, these studies emphasize the necessity of a paradigm shift for better quality care and greater satisfaction of mothers, and they consider lack of continuity of care as the reason for the increase in unnecessary cesarean sections [ 23 , 24 , 25 ]. Moreover, the lack of qualified and experienced workforce has led to low quality health services, including midwifery care, and an increase in the economic burden of health. In Iran, no study has yet been conducted to investigate the effect of the midwifery continuity of care model on the students’ clinical competence and pregnancy outcomes. Given the importance of this topic, using a mixed-methods study design, we aimed to assess the effect of a midwifery continuity of care program on the clinical competence of midwifery students and pregnancy outcomes in Ahvaz, Iran.

Specific objectives

To determine the effect of midwifery continuity of care program on the clinical competence of midwifery students.

To determine the effect of a midwifery continuity of care program provided by midwifery students on pregnancy outcomes.

To explain the perception of midwifery students and mothers about the use of the midwifery continuity of care program provided by midwifery students.

Methods/design

Study design.

This sequential embedded mixed-methods study will include a quantitative phase and a qualitative one. A mixed (embedded) experimental design involves the collection and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data by the researcher and the integration of the information into an experimental study or intervention trial. This design adds qualitative data to an experiment or intervention to integrate the personal experience of research participants. Therefore, the qualitative data are converted into a secondary source of data embedded before and after the test. Qualitative data is added to the experiment in differrent ways, including: before the experiment, during the experiment, or after the experiment [ 26 , 27 ]. Embedded mixed-methods studies that are qualitative followed by quantitative are used to understand the rationale for the results and receive feedback from participants (to confirm and support the findings of the quantitative studies) [ 27 ]. In the first stage of this study, a questionnaire for assessing midwifery students’ clinical competence will be created based on the midwifery curriculum of Iran and a review of seminal texts of midwifery. Then, the effect of continuity of care provided by midwifery students on maternal and neonatal outcomes will be assessed in a randomized clinical trial. In the third stage, a qualitative study will be carried out to investigate the perception of students and mothers. Finally, the results of the quantitative and qualitative phases will be integrated (Fig. 1 ).

Sequential and embedded mixed-methods design

First stage: questionnaire development

This questionnaire will be developed based on midwifery curriculum and a comprehensive and systematic search (with no time limit) in English and Persian databases (Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, ProQuest, Google scholar, Magiran, SID).

Tool design

There are four steps in tool development:

Choosing a conceptual model to show aspects of clinical competence in the measurement process

Explaining the purpose of the tool

Designing the route map

Developing the tool (use of methods, classification of objects, rules and procedures for scoring tools) [ 28 ].

Answer to the objects

A 1 to 4-point Likert scale will be used for scoring [ 29 ].

Content validity

To ensure the selection of the most important and correct content (necessity of the case), the content validity will be assessed. Also, to ensure that the instrument items are designed in the best way to measure the content, the content validity index will be calculated [ 30 ].

Reliability

Reliability will be evaluated using internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha coefficient ≥ 0.7) and stability (test-re-test ≥ 0.74) by piloting the questionnaire on 20 midwifery students [ 31 ].

Second stage: quantitative phase

A randomized controlled clinical trial will be conducted in this phase of research to examine the effect of the continuous care program of midwifery students on their clinical competence and pregnancy outcomes.

Sample size

According to the study objective and previous study results [ 32 ] with α = 0.01, β = 0.1, p 1 = 0.51 and p 2 = 0.021, the sample size will be n = 23. Considering a 20% dropout rate, the final sample size will be 58 women (29 women in each group).

Data collection

This phase of the randomized clinical trial will be conducted with the participation of 58 undergraduate midwifery students at their 7th and 8th semesters. The students will be divided randomly to intervention (continuous care) and control (routine care) groups providing care to 58 pregnant women in six health centers and two hospitals (Sina and Razi) in Ahvaz city, southwest of Iran.

The study will begin after receiving the approval of the Ethics Committee of Ahvaz University of Medical Sciences and registering the study in the Iranian Registry for Randomized Clinical Trials. Inclusion criteria will be willingness to participate in the study.

Randomization

To implement the intervention, the students will be divided into two intervention (providing continuous care for pregnant women) and control (providing standard care for pregnant women) groups. Allocating students will be done using permuted block randomization technique with a block size of four and an allocation ratio of 1:1. Five blocks of 4 pieces and 3 blocks of 3 pieces will be extracted randomly using WIN PEPI software. In each block of 4, 2 students will be in control and 2 will be in intervention group. Also, in each block of 3 students, 1 student will be in control and 2 will be in intervention group, and the arrangement of each person is random. To prevent contamination, first the control group will provide routine care, and then the intervention group will conduct continuity of care for pregnant women. Mothers are randomly selected based on the hospital where they will give birth. As a result, Razi Hospital will be the control group and Sina Hospital will be the intervention group.

Intervention

Women who meet the inclusion criteria will be recruited in the study using a non-probability convenience sampling method. Women in the intervention group will be included in the study after their first pregnancy visit (6–10 weeks of gestation) and will receive continuous care by midwifery students. Women in the control group will receive the usual and routine care, and will be included in the study at the time of delivery. They will have a gestational age of more than 37 weeks based on the inclusion criteria of the study. Their delivery will be performed by midwifery students who will follow them up until six weeks after delivery.

At first, the necessary training will be given by the lead researcher (FR) to the students in orientation sessions held for both groups separately. In the intervention group, each midwifery student as the main midwife will be responsible for taking care of two or three pregnant women and will be the back-up midwife for two other pregnant women (under the supervision of other students). The lead researcher will create a group in WhatsApp with the participation of students in the intervention group, and they can communicate with each other and the researcher. Also, the midwifery students will be directly and indirectly under the supervision of a qualified person (lead researcher). Another WhatsApp group will be created for the women of the intervention and control groups (to facilitate communication between the researcher and the women). Two midwifery students will be introduced to each pregnant woman in the intervention group (as a main midwife and a backup midwife). If the main midwife is not available, the woman will be in contact with the backup midwife. The backup student will meet the woman at least once and will be introduced to her.

Instruments

All students and pregnant women participating in this study will complete a demographic questionnaire. A checklist will be provided for collecting data during prenatal care, labor, and delivery.

Also, the midwifery students will complete the clinical competency questionnaire at the beginning and end of the study.

Care will be provided and recorded by the main student according to the pregnancy care protocol. Also, danger signs will be taught to the students according to the national protocol, and emergencies will be handled by the midwifery student under the supervision of the lead researcher. Admission to hospital will be arranged by the student, and all information will be recorded. Pregnancy, labour and delivery, postpartum, and newborn checklist will be completed. Students will complete a demographic and obstetric questionnaire that includes questions about age, education, occupation, gravidity, parity, abortions, live and dead children, last contraceptive method, intended and unintended pregnancies, last menstrual period (LMP), gestational age, date of birth, body mass index (BMI), previous pregnancy and childbirth records, high-risk behavior of the mother and father, current history of special care, test and ultrasound results, and participation in childbirth preparation class. Also, the following data will be recorded in the labor and delivery and post-partum checklist: checking the conditions of labor according to the partograph, length of labor, need for induction and the method used type of delivery, examination of perineal trauma, postpartum bleeding, and examination of the condition of the mother up to 6 weeks after delivery. In addition, the amount of bleeding will be checked visually and by measuring the level of hemoglobin and hematocrit. Apgar score of the newborn will be recorded (in infant checklist) in minutes 1 and 5. Also, the newborn’s hospitalization status, breastfeeding and anthropometric indices will be recorded.

The students in the intervention group will start prenatal care < 20 weeks of gestation. At least five round of prenatal care will be provided by each student according to national guidelines for each pregnant woman. Pregnant women can communicate with their in-charge students in non-emergency cases from 8:00 a.m. to 23:00 p.m. and in emergency cases 24 h a day, all days a week. All reports will be recorded by the students. During labor and delivery, the student and the lead researcher will be present at the mother's bedside. In case of natural vaginal delivery (NVD), delivery will be done by a student midwife under the supervision of the researcher. In case of cesarean delivery (CS), a student will be present at the patient's bedside. Postpartum care will be provided by midwifery students in both groups (intervention and control). Each student will be at the mother's bedside for two hours after delivery. The conditions of labor, delivery, and the neonate will be recorded by the student in the relevant form. Also, the mother will be followed up by telephone for up to 6 weeks after delivery (postpartum). The clinical competency questionnaire will be completed by students before and after the intervention.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for midwifery students will be: studying at the seventh and eighth semester and willingness to participate in the study.

Inclusion criteria for service recipients (pregnant women) will be: age 18 – 40 years, Iranian nationality, singleton pregnancy, low risk pregnancy, and gestational age < 20 wks.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria will be: history of psychiatric disorders, previous caesarean section, use of alcohol and tobacco, or having a disease that requires prenatal care by a specialist.

Primary outcome

Clinical competence of midwifery students.

Secondary outcome

Mode of delivery, length of labor stages, the need to induction, postpartum bleeding first and fifth minute Apgar score, admission of neonate to the neonatal intensive care unit, breastfeeding initiation, and exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 weeks postpartum.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses will be done using SPSS version 26.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The independent t-test and Chi-square tests will be used for continuous data and categorical data, respectively. ANCOVA test will be used to eliminate the influence of confounding variables. The effect size will be calculated. A 95% confidence interval (CI) and p values will be reported. P -values less than 0.5 will be considered statistically significant.

Third step of research: qualitative study

This phase will be a qualitative study using conventional content analysis.

Purposeful sampling will be used in this study [ 33 ]. Sampling will continue until data saturation [ 34 ], i.e., no new information or data about a class or relationships between classes is revealed.

This phase of the study is a conventional qualitative content analysis [ 35 ] aimed at examining the perceptions of midwifery students and mothers receiving continuous care. The researcher will conduct in-depth, semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions with students and mothers in the group of the continuous care program. All interviews will be done by the lead researcher who is qualified in qualitative research method. The interview will start with a general and open question such as: “Please tell me about your experiences or feelings about participating in the continuous midwifery care program. How did you feel about participating in this program?” Then, in-depth exploratory questions will be asked based on their answers (e.g., what do you mean? Why? Can you elaborate on that? Can you give me an example so I can understand what you mean?). All interviews will be recorded with the participants' consent. Paralinguistic features, such as mood and features of the participants, including tone of voice, facial expressions, and their posture, will be recorded by the researcher during the interview [ 35 ].

The data will be analyzed based on Granheim and Lundman's 2004 content analysis approach [ 36 ].

Interviews will be transcribed at the end of each interview. Data analysis begins with a careful study of all data so that the researcher can immerse herself in the data and gain an overview. Interviews will be transcribed verbatim. Key concepts will be highlighted and codes will be extracted. Then the first interpretations will be made and analyzed. Labels emerge for codes that represent more than one key concept and are usually taken directly from the text and become the initial coding map. Then the codes are placed in the category based on their similarity. Then, definitions will be created for each category, subcategory and code. When reporting findings, examples of each code and data category will be provided [ 35 ].

Inclusion criteria for midwifery students will be: studying at the seventh or eighth semester, willingness to participate in the study.

Inclusion criteria for service recipients (pregnant women) will be: receiving continuous care provided by the student, willingness to participate in the study, and being able to communicate.

The qualitative study and interview data will be analyzed based on the content analysis approach of Granheim and Lundman 2004 [ 36 ] as follows:

Reading and re-reading the interviews after completion of each interview

Selection of the unit of analysis

Determination of semantic units

Classification

Extraction of information content