.css-s5s6ko{margin-right:42px;color:#F5F4F3;}@media (max-width: 1120px){.css-s5s6ko{margin-right:12px;}} Discover how today’s most successful IT leaders stand out from the rest. .css-1ixh9fn{display:inline-block;}@media (max-width: 480px){.css-1ixh9fn{display:block;margin-top:12px;}} .css-1uaoevr-heading-6{font-size:14px;line-height:24px;font-weight:500;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;color:#F5F4F3;}.css-1uaoevr-heading-6:hover{color:#F5F4F3;} .css-ora5nu-heading-6{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-box-pack:start;-ms-flex-pack:start;-webkit-justify-content:flex-start;justify-content:flex-start;color:#0D0E10;-webkit-transition:all 0.3s;transition:all 0.3s;position:relative;font-size:16px;line-height:28px;padding:0;font-size:14px;line-height:24px;font-weight:500;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;color:#F5F4F3;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover{border-bottom:0;color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover path{fill:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover div{border-color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover div:before{border-left-color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active{border-bottom:0;background-color:#EBE8E8;color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active path{fill:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active div{border-color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active div:before{border-left-color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover{color:#F5F4F3;} Read the report .css-1k6cidy{width:11px;height:11px;margin-left:8px;}.css-1k6cidy path{fill:currentColor;}

- Leadership |

- 7 important steps in the decision makin ...

7 important steps in the decision making process

The decision making process is a method of gathering information, assessing alternatives, and making a final choice with the goal of making the best decision possible. In this article, we detail the step-by-step process on how to make a good decision and explain different decision making methodologies.

We make decisions every day. Take the bus to work or call a car? Chocolate or vanilla ice cream? Whole milk or two percent?

There's an entire process that goes into making those tiny decisions, and while these are simple, easy choices, how do we end up making more challenging decisions?

At work, decisions aren't as simple as choosing what kind of milk you want in your latte in the morning. That’s why understanding the decision making process is so important.

What is the decision making process?

The decision making process is the method of gathering information, assessing alternatives, and, ultimately, making a final choice.

Decision-making tools for agile businesses

In this ebook, learn how to equip employees to make better decisions—so your business can pivot, adapt, and tackle challenges more effectively than your competition.

The 7 steps of the decision making process

Step 1: identify the decision that needs to be made.

When you're identifying the decision, ask yourself a few questions:

What is the problem that needs to be solved?

What is the goal you plan to achieve by implementing this decision?

How will you measure success?

These questions are all common goal setting techniques that will ultimately help you come up with possible solutions. When the problem is clearly defined, you then have more information to come up with the best decision to solve the problem.

Step 2: Gather relevant information

Gathering information related to the decision being made is an important step to making an informed decision. Does your team have any historical data as it relates to this issue? Has anybody attempted to solve this problem before?

It's also important to look for information outside of your team or company. Effective decision making requires information from many different sources. Find external resources, whether it’s doing market research, working with a consultant, or talking with colleagues at a different company who have relevant experience. Gathering information helps your team identify different solutions to your problem.

Step 3: Identify alternative solutions

This step requires you to look for many different solutions for the problem at hand. Finding more than one possible alternative is important when it comes to business decision-making, because different stakeholders may have different needs depending on their role. For example, if a company is looking for a work management tool, the design team may have different needs than a development team. Choosing only one solution right off the bat might not be the right course of action.

Step 4: Weigh the evidence

This is when you take all of the different solutions you’ve come up with and analyze how they would address your initial problem. Your team begins identifying the pros and cons of each option, and eliminating alternatives from those choices.

There are a few common ways your team can analyze and weigh the evidence of options:

Pros and cons list

SWOT analysis

Decision matrix

Step 5: Choose among the alternatives

The next step is to make your final decision. Consider all of the information you've collected and how this decision may affect each stakeholder.

Sometimes the right decision is not one of the alternatives, but a blend of a few different alternatives. Effective decision-making involves creative problem solving and thinking out of the box, so don't limit you or your teams to clear-cut options.

One of the key values at Asana is to reject false tradeoffs. Choosing just one decision can mean losing benefits in others. If you can, try and find options that go beyond just the alternatives presented.

Step 6: Take action

Once the final decision maker gives the green light, it's time to put the solution into action. Take the time to create an implementation plan so that your team is on the same page for next steps. Then it’s time to put your plan into action and monitor progress to determine whether or not this decision was a good one.

Step 7: Review your decision and its impact (both good and bad)

Once you’ve made a decision, you can monitor the success metrics you outlined in step 1. This is how you determine whether or not this solution meets your team's criteria of success.

Here are a few questions to consider when reviewing your decision:

Did it solve the problem your team identified in step 1?

Did this decision impact your team in a positive or negative way?

Which stakeholders benefited from this decision? Which stakeholders were impacted negatively?

If this solution was not the best alternative, your team might benefit from using an iterative form of project management. This enables your team to quickly adapt to changes, and make the best decisions with the resources they have.

Types of decision making models

While most decision making models revolve around the same seven steps, here are a few different methodologies to help you make a good decision.

Rational decision making models

This type of decision making model is the most common type that you'll see. It's logical and sequential. The seven steps listed above are an example of the rational decision making model.

When your decision has a big impact on your team and you need to maximize outcomes, this is the type of decision making process you should use. It requires you to consider a wide range of viewpoints with little bias so you can make the best decision possible.

Intuitive decision making models

This type of decision making model is dictated not by information or data, but by gut instincts. This form of decision making requires previous experience and pattern recognition to form strong instincts.

This type of decision making is often made by decision makers who have a lot of experience with similar kinds of problems. They have already had proven success with the solution they're looking to implement.

Creative decision making model

The creative decision making model involves collecting information and insights about a problem and coming up with potential ideas for a solution, similar to the rational decision making model.

The difference here is that instead of identifying the pros and cons of each alternative, the decision maker enters a period in which they try not to actively think about the solution at all. The goal is to have their subconscious take over and lead them to the right decision, similar to the intuitive decision making model.

This situation is best used in an iterative process so that teams can test their solutions and adapt as things change.

Track key decisions with a work management tool

Tracking key decisions can be challenging when not documented correctly. Learn more about how a work management tool like Asana can help your team track key decisions, collaborate with teammates, and stay on top of progress all in one place.

Related resources

Fix these common onboarding challenges to boost productivity

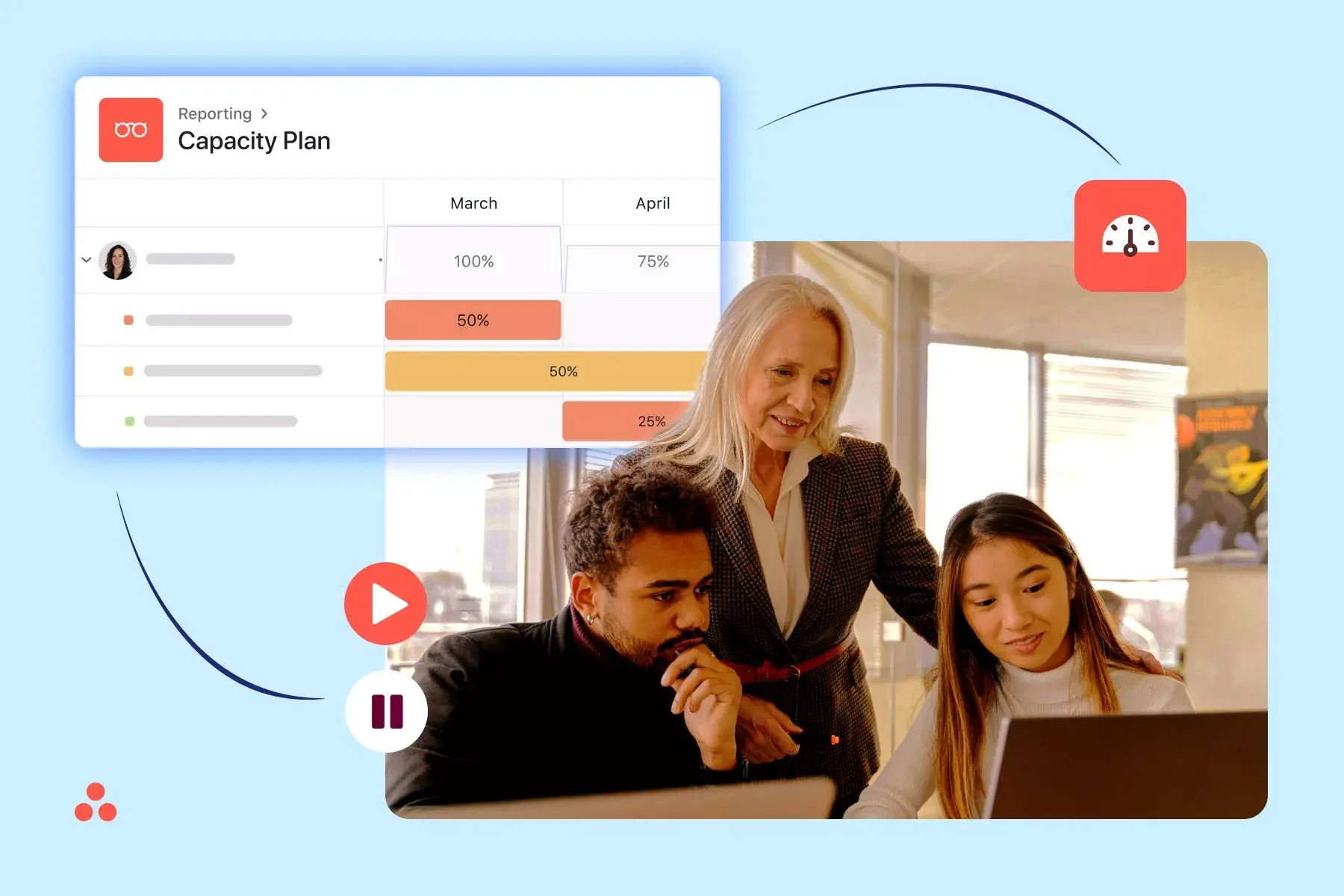

How Asana uses work management to optimize resource planning

Understanding dependencies in project management

How Asana uses work management for organizational planning

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

8.5: Problem Solving and Decision-Making in Groups

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 106475

- Lisa Coleman, Thomas King, & William Turner

- Southwest Tennessee Community College

Learning Objectives

- Discuss the common components and characteristics of problems.

- Explain the five steps of the group problem-solving process.

- Discuss the various influences on decision-making.

Although the steps of problem-solving and decision-making that we will discuss next may seem obvious, we often don’t think to or choose not to use them. Instead, we start working on a problem and later realize we are lost and have to backtrack. I’m sure we’ve all reached a point in a project or task and had the “OK, now what?” moment. I’ve recently taken up some carpentry projects as a functional hobby, and I have developed a great respect for the importance of advanced planning. It’s frustrating to get to a crucial point in building or fixing something only to realize that you have to unscrew a support board that you already screwed in, have to drive back to the hardware store to get something that you didn’t think to get earlier, or have to completely start over. In this section, we will discuss the group problem-solving process, methods of decision making, and influences on these processes.

Group Problem-Solving Process

There are several variations of similar problem-solving models based on US American scholar John Dewey’s reflective thinking process (Bormann & Bormann, 1988). As you read through the steps in the process, think about how we can apply what we have learned regarding the general and specific elements of problems. Some of the following steps are straightforward, and they are things we would logically do when faced with a problem. However, taking a deliberate and systematic approach to problem-solving has been shown to benefit group functioning and performance. A deliberate approach is especially beneficial for groups that do not have an established history of working together and will only be able to meet occasionally. Although a group should attend to each step of the process, group leaders or other group members who facilitate problem-solving should be cautious not to dogmatically follow each element of the process or force a group along. Such a lack of flexibility could limit group member input and negatively affect the group’s cohesion and climate.

Step 1: Define the Problem

Define the problem by considering the three elements shared by every problem: the current undesirable situation , the goal or more desirable situation, and obstacles in the way (Adams & Galanes, 2009). At this stage, group members share what they know about the current situation, without proposing solutions or evaluating the information. Here are some good questions to ask during this stage: What is the current difficulty? How did we come to know that the difficulty exists? Who/what is involved? Why is it meaningful/urgent/important? What have the effects been so far? What, if any, elements of the difficulty require clarification? At the end of this stage, the group should be able to compose a single sentence that summarizes the problem called a problem statement. Avoid wording in the problem statement or question that hints at potential solutions. A small group formed to investigate ethical violations of city officials could use the following problem statement: “Our state does not currently have a mechanism for citizens to report suspected ethical violations by city officials.”

Step 2: Analyze the Problem

During this step, a group should analyze the problem and the group’s relationship to the problem. Whereas the first step involved exploring the “what” related to the problem, this step focuses on the “why.” At this stage, group members can discuss the potential causes of the difficulty. Group members may also want to begin setting out an agenda or timeline for the group’s problem-solving process, looking forward to the other steps. To fully analyze the problem, the group can discuss the five common problem variables discussed before. Here are two examples of questions that the group formed to address ethics violations might ask: Why doesn’t our city have an ethics reporting mechanism? Do cities of similar size have such a mechanism? Once the problem has been analyzed, the group can pose a problem question that will guide the group as it generates possible solutions. “How can citizens report suspected ethical violations of city officials and how will such reports be processed and addressed?” As you can see, the problem question is more complex than the problem statement, since the group has moved on to a more in-depth discussion of the problem during step 2.

Step 3: Generate Possible Solutions

During this step, group members generate possible solutions to the problem. Again, solutions should not be evaluated at this point, only proposed and clarified. The question should be what could we do to address this problem, not what should we do to address it. It is perfectly OK for a group member to question another person’s idea by asking something like “What do you mean?” or “Could you explain your reasoning more?” Discussions at this stage may reveal a need to return to previous steps to better define or more fully analyze a problem. Since many problems are multifaceted, it is necessary for group members to generate solutions for each part of the problem separately, making sure to have multiple solutions for each part. Stopping the solution-generating process prematurely can lead to groupthink. For the problem question previously posed, the group would need to generate solutions for all three parts of the problem included in the question. Possible solutions for the first part of the problem (How can citizens report ethical violations?) may include “online reporting system, e-mail, in-person, anonymously, on-the-record,” and so on. Possible solutions for the second part of the problem (How will reports be processed?) may include “daily by a newly appointed ethics officer, weekly by a nonpartisan nongovernment employee,” and so on. Possible solutions for the third part of the problem (How will reports be addressed?) may include “by a newly appointed ethics commission, by the accused’s supervisor, by the city manager,” and so on.

Step 4: Evaluate Solutions

During this step, solutions can be critically evaluated based on their credibility, completeness, and worth. Once the potential solutions have been narrowed based on more obvious differences in relevance and/or merit, the group should analyze each solution based on its potential effects—especially negative effects. Groups that are required to report the rationale for their decision or whose decisions may be subject to public scrutiny would be wise to make a set list of criteria for evaluating each solution. Additionally, solutions can be evaluated based on how well they fit with the group’s charge and the abilities of the group. To do this, group members may ask, “Does this solution live up to the original purpose or mission of the group?” and “Can the solution actually be implemented with our current resources and connections?” and “How will this solution be supported, funded, enforced, and assessed?” Secondary tensions and substantive conflict, two concepts discussed earlier, emerge during this step of problem-solving, and group members will need to employ effective critical thinking and listening skills.

Decision-making is part of the larger process of problem-solving and it plays a prominent role in this step. While there are several fairly similar models for problem-solving, there are many varied decision-making techniques that groups can use. For example, to narrow the list of proposed solutions, group members may decide by majority vote, by weighing the pros and cons, or by discussing them until a consensus is reached. There are also more complex decision-making models like the “six hats method,” which we will discuss later. Once the final decision is reached, the group leader or facilitator should confirm that the group is in agreement. It may be beneficial to let the group break for a while or even to delay the final decision until a later meeting to allow people time to evaluate it outside of the group context.

Step 5: Implement and Assess the Solution

Implementing the solution requires some advanced planning, and it should not be rushed unless the group is operating under strict time restraints or delay may lead to some kind of harm. Although some solutions can be implemented immediately, others may take days, months, or years. As was noted earlier, it may be beneficial for groups to poll those who will be affected by the solution as to their opinion of it or even do a pilot test to observe the effectiveness of the solution and how people react to it. Before implementation, groups should also determine how and when they would assess the effectiveness of the solution by asking, “How will we know if the solution is working or not?” Since solution assessment will vary based on whether or not the group is disbanded, groups should also consider the following questions: If the group disbands after implementation, who will be responsible for assessing the solution? If the solution fails, will the same group reconvene or will a new group be formed?

Certain elements of the solution may need to be delegated out to various people inside and outside the group. Group members may also be assigned to implement a particular part of the solution based on their role in the decision-making or because it connects to their area of expertise. Likewise, group members may be tasked with publicizing the solution or “selling” it to a particular group of stakeholders. Last, the group should consider its future. In some cases, the group will get to decide if it will stay together and continue working on other tasks or if it will disband. In other cases, outside forces determine the group’s fate.

“Getting Competent”: Problem Solving and Group Presentations

Giving a group presentation requires that individual group members and the group as a whole solve many problems and make many decisions. Although having more people involved in a presentation increases logistical difficulties and has the potential to create more conflict, a well-prepared and well-delivered group presentation can be more engaging and effective than a typical presentation. The main problems facing a group giving a presentation are (1) dividing responsibilities, (2) coordinating schedules and time management, and (3) working out the logistics of the presentation delivery.

In terms of dividing responsibilities, assigning individual work at the first meeting and then trying to fit it all together before the presentation (which is what many college students do when faced with a group project) is not the recommended method. Integrating content and visual aids created by several different people into a seamless final product takes time and effort, and the person “stuck” with this job at the end usually ends up developing some resentment toward his or her group members. While it’s OK for group members to do work independently outside of group meetings, spend time working together to help set up some standards for content and formatting expectations that will help make later integration of work easier. Taking the time to complete one part of the presentation together can help set those standards for later individual work. Discuss the roles that various group members will play openly so there isn’t role confusion. There could be one point person for keeping track of the group’s progress and schedule, one point person for communication, one point person for content integration, one point person for visual aids, and so on. Each person shouldn’t do all that work on his or her own but help focus the group’s attention on his or her specific area during group meetings (Stanton, 2009).

Scheduling group meetings is one of the most challenging problems groups face, given people’s busy lives. From the beginning, it should be clearly communicated that the group needs to spend considerable time in face-to-face meetings, and group members should know that they may have to make an occasional sacrifice to attend. Especially important is the commitment to scheduling time to rehearse the presentation. Consider creating a contract of group guidelines that include expectations for meeting attendance to increase group members’ commitment.

Group presentations require members to navigate many logistics of their presentation. While it may be easier for a group to assign each member to create a five-minute segment and then transition from one person to the next, this is definitely not the most engaging method. Creating a master presentation and then assigning individual speakers creates a more fluid and dynamic presentation and allows everyone to become familiar with the content, which can help if a person doesn’t show up to present and during the question-and-answer section. Once the content of the presentation is complete, figure out introductions, transitions, visual aids, and the use of time and space (Stanton, 2012). In terms of introductions, figure out if one person will introduce all the speakers at the beginning, if speakers will introduce themselves at the beginning, or if introductions will occur as the presentation progresses. In terms of transitions, make sure each person has included in his or her speaking notes when presentation duties switch from one person to the next. Visual aids have the potential to cause hiccups in a group presentation if they aren’t fluidly integrated. Practicing with visual aids and having one person control them may help prevent this. Know how long your presentation is and know how you’re going to use the space. Presenters should know how long the whole presentation should be and how long each of their segments should be so that everyone can share the responsibility of keeping time. Also, consider the size and layout of the presentation space. You don’t want presenters huddled in a corner until it’s their turn to speak or trapped behind furniture when their turn comes around.

- Of the three main problems facing group presenters, which do you think is the most challenging and why?

- Why do you think people tasked with a group presentation (especially students) prefer to divide the parts up and have members work on them independently before coming back together and integrating each part? What problems emerge from this method? In what ways might developing a master presentation and then assign parts to different speakers be better than the more divided method? What are the drawbacks to the master presentation method?

Specific Decision-Making Techniques

Some decision-making techniques involve determining a course of action based on the level of agreement among the group members. These methods include majority , expert , authority , and consensus rule . Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) “Pros and Cons of Agreement-Based Decision-Making Techniques” reviews the pros and cons of each of these methods.

Majority rule is a commonly used decision-making technique in which a majority (one-half plus one) must agree before a decision is made . A show-of-hands vote, a paper ballot, or an electronic voting system can determine the majority choice. Many decision-making bodies, including the US House of Representatives, Senate, and Supreme Court, use majority rule to make decisions, which shows that it is often associated with democratic decision-making since each person gets one vote and each vote counts equally. Of course, other individuals and mediated messages can influence a person’s vote, but since the voting power is spread out over all group members, it is not easy for one person or party to take control of the decision-making process. In some cases—for example, to override a presidential veto or to amend the constitution—a supermajority of two-thirds may be required to make a decision.

Minority rule is a decision-making technique in which a designated authority or expert has the final say over a decision and may or may not consider the input of other group members . When a designated expert makes a decision by minority rule, there may be buy-in from others in the group, especially if the members of the group didn’t have relevant knowledge or expertise. When a designated authority makes decisions, buy-in will vary based on group members’ level of respect for the authority. For example, decisions made by an elected authority may be more accepted by those who elected him or her than by those who didn’t. As with majority rule, this technique can be time-saving. Unlike majority rule, one person or party can have control over the decision-making process. This type of decision-making is more similar to that used by monarchs and dictators. An obvious negative consequence of this method is that the needs or wants of one person can override the needs and wants of the majority. A minority deciding for the majority has led to negative consequences throughout history. The white Afrikaner minority that ruled South Africa for decades instituted apartheid, which was a system of racial segregation that disenfranchised and oppressed the majority population. The quality of the decision and its fairness really depends on the designated expert or authority.

Consensus rule is a decision-making technique in which all members of the group must agree on the same decision . On rare occasions, a decision may be ideal for all group members, which can lead to a unanimous agreement without further debate and discussion. Although this can be positive, be cautious that this isn’t a sign of groupthink. More typically, the consensus is reached only after a lengthy discussion. On the plus side, consensus often leads to high-quality decisions due to the time and effort it takes to get everyone in agreement. Group members are also more likely to be committed to the decision because of their investment in reaching it. On the negative side, the ultimate decision is often one that all group members can live with but not one that’s ideal for all members. Additionally, the process of arriving at a consensus also includes conflict, as people debate ideas and negotiate the interpersonal tensions that may result.

“Getting Critical”: Six Hats Method of Decision Making

Edward de Bono developed the Six Hats method of thinking in the late 1980s, and it has since become a regular feature in decision-making training in business and professional contexts (de Bono, 1985). The method’s popularity lies in its ability to help people get out of habitual ways of thinking and to allow group members to play different roles and see a problem or decision from multiple points of view. The basic idea is that each of the six hats represents a different way of thinking, and when we figuratively switch hats, we switch the way we think. The hats and their style of thinking are as follows:

- White hat. Objective—focuses on seeking information such as data and facts and then processes that information in a neutral way.

- Red hat. Emotional—uses intuition, gut reactions, and feelings to judge information and suggestions.

- Black hat. Negative—focus on potential risks, point out possibilities for failure, and evaluates information cautiously and defensively.

- Yellow hat. Positive—is optimistic about suggestions and future outcomes gives constructive and positive feedback, points out benefits and advantages.

- Green hat. Creative—try to generate new ideas and solutions, think “outside the box.”

- Blue hat. Philosophical—uses metacommunication to organize and reflect on the thinking and communication taking place in the group, facilitates who wears what hat and when group members change hats.

Specific sequences or combinations of hats can be used to encourage strategic thinking. For example, the group leader may start off wearing the Blue Hat and suggest that the group start their decision-making process with some “White Hat thinking” in order to process through facts and other available information. During this stage, the group could also process through what other groups have done when faced with a similar problem. Then the leader could begin an evaluation sequence starting with two minutes of “Yellow Hat thinking” to identify potential positive outcomes, then “Black Hat thinking” to allow group members to express reservations about ideas and point out potential problems, then “Red Hat thinking” to get people’s gut reactions to the previous discussion, then “Green Hat thinking” to identify other possible solutions that are more tailored to the group’s situation or completely new approaches. At the end of a sequence, the Blue Hat would want to summarize what was said and begin a new sequence. To successfully use this method, the person wearing the Blue Hat should be familiar with different sequences and plan some of the thinking patterns ahead of time based on the problem and the group members. Each round of thinking should be limited to a certain time frame (two to five minutes) to keep the discussion moving.

- This decision-making method has been praised because it allows group members to “switch gears” in their thinking and allows for role-playing, which lets people express ideas more freely. How can this help enhance critical thinking? Which combination of hats do you think would be best for a critical thinking sequence?

- What combinations of hats might be useful if the leader wanted to break the larger group up into pairs and why? For example, what kind of thinking would result from putting Yellow and Red together, Black and White together, or Red and White together, and so on?

- Based on your preferred ways of thinking and your personality, which hat would be the best fit for you? Which would be the most challenging? Why?

Influences on Decision Making

The personalities of group members, especially leaders and other active members, affect the climate of the group. Group member personalities can be categorized based on where they fall on a continuum anchored by the following descriptors: dominant/submissive, friendly/unfriendly, and instrumental/emotional (Cragan & Wright, 1999). The more group members there are in any extreme of these categories, the more likely it that the group climate will also shift to resemble those characteristics.

- Dominant versus submissive. Group members that are more dominant act more independently and directly, initiate conversations, take up more space, make more direct eye contact, seek leadership positions, and take control over decision-making processes. More submissive members are reserved, contribute to the group only when asked to, avoid eye contact, and leave their personal needs and thoughts unvoiced or give in to the suggestions of others.

- Friendly versus unfriendly. Group members on the friendly side of the continuum find a balance between talking and listening, don’t try to win at the expense of other group members, are flexible but not weak, and value democratic decision-making. Unfriendly group members are disagreeable, indifferent, withdrawn, and selfish, which leads them to either not invest in decision making or direct it in their own interest rather than in the interest of the group.

- Instrumental versus emotional. Instrumental group members are emotionally neutral, objective, analytical, task-oriented, and committed followers, which leads them to work hard and contribute to the group’s decision-making as long as it is orderly and follows agreed-on rules. Emotional group members are creative, playful, independent, unpredictable, and expressive, which leads them to make rash decisions, resist group norms or decision-making structures and switch often from relational to task focus.

Domestic Diversity and Group Communication

While it is becoming more likely that we will interact in small groups with international diversity, we are guaranteed to interact in groups that are diverse in terms of the cultural identities found within a single country or the subcultures found within a larger cultural group.

Gender stereotypes sometimes influence the roles that people play within a group. For example, the stereotype that women are more nurturing than men may lead group members (both male and female) to expect that women will play the role of supporters or harmonizers within the group. Since women have primarily performed secretarial work since the 1900s, it may also be expected that women will play the role of the recorder. In both of these cases, stereotypical notions of gender place women in roles that are typically not as valued in group communication. The opposite is true for men. In terms of leadership, despite notable exceptions, research shows that men fill an overwhelmingly disproportionate amount of leadership positions. We are socialized to see certain behaviors by men as indicative of leadership abilities, even though they may not be. For example, men are often perceived to contribute more to a group because they tend to speak first when asked a question or to fill a silence and are perceived to talk more about task-related matters than relationally oriented matters. Both of these tendencies create a perception that men are more engaged with the task. Men are also socialized to be more competitive and self-congratulatory, meaning that their communication may be seen as dedicated and their behaviors seen as powerful, and that when their work isn’t noticed they will be more likely to make it known to the group rather than take silent credit. Even though we know that the relational elements of a group are crucial for success, even in high-performance teams, that work is not as valued in our society as task-related work.

Despite the fact that some communication patterns and behaviors related to our typical (and stereotypical) gender socialization affects how we interact in and form perceptions of others in groups, the differences in group communication that used to be attributed to gender in early group communication research seem to be diminishing. This is likely due to the changing organizational cultures from which much group work emerges, which have now had more than sixty years to adjust to women in the workplace. It is also due to a more nuanced understanding of gender-based research, which doesn’t take a stereotypical view from the beginning as many of the early male researchers did. Now, instead of biological sex being assumed as a factor that creates inherent communication differences, group communication scholars see that men and women both exhibit a range of behaviors that are more or less feminine or masculine. It is these gendered behaviors, and not a person’s gender, that seem to have more of an influence on perceptions of group communication. Interestingly, group interactions are still masculinist in that male and female group members prefer a more masculine communication style for task leaders and that both males and females in this role are more likely to adapt to a more masculine communication style. Conversely, men who take on social-emotional leadership behaviors adopt a more feminine communication style. In short, it seems that although masculine communication traits are more often associated with high-status positions in groups, both men and women adapt to this expectation and are evaluated similarly (Haslett & Ruebush, 1999).

Other demographic categories are also influential in group communication and decision-making. In general, group members have an easier time communicating when they are more similar than different in terms of race and age. This ease of communication can make group work more efficient, but the homogeneity, meaning the members are more similar, may sacrifice some creativity. n general, groups that are culturally heterogeneous have better overall performance than more homogenous groups (Haslett & Ruebush, 1999). These groups benefit from the diversity of perspectives in terms of the quality of decision-making and creativity of output.

The benefits and challenges that come with the diversity of group members are important to consider. Since we will all work in diverse groups, we should be prepared to address potential challenges in order to reap the benefits. Diverse groups may be wise to coordinate social interactions outside of group time in order to find common ground that can help facilitate interaction and increase group cohesion. We should be sensitive but not let sensitivity create fear of “doing something wrong” which then prevents us from having meaningful interactions.

Key Takeaways

- Every problem has common components: an undesirable situation, the desired situation, and obstacles between the undesirable and desirable situations. Every problem also has a set of characteristics that vary among problems, including task difficulty, number of possible solutions, group member interest in the problem, group familiarity with the problem, and the need for solution acceptance.

- Define the problem by creating a problem statement that summarizes it.

- Analyze the problem and create a problem question that can guide solution generation.

- Generate possible solutions. Possible solutions should be offered and listed without stopping to evaluate each one.

- Evaluate the solutions based on their credibility, completeness, and worth. Groups should also assess the potential effects of the narrowed list of solutions.

- Implement and assess the solution. Aside from enacting the solution, groups should determine how they will know the solution is working or not.

- Common decision-making techniques include majority rule, minority rule, and consensus rule. Only a majority, usually one-half plus one, must agree before a decision is made with majority rule. With minority rule, designated authority or expert has final say over a decision, and the input of group members may or may not be invited or considered. With consensus rule, all members of the group must agree on the same decision.

- Situational factors include the degree of freedom a group has to make its own decisions, the level of uncertainty facing the group and its task, the size of the group, the group’s access to information, and the origin and urgency of the problem.

- Personality influences on decision making include a person’s value orientation (economic, aesthetic, theoretical, political, or religious), and personality traits (dominant/submissive, friendly/unfriendly, and instrumental/emotional).

- Cultural influences on decision making include the heterogeneity or homogeneity of the group makeup; cultural values and characteristics such as individualism/collectivism, power distance, and high-/low-context communication styles; and gender and age differences.

- Scenario 1. Task difficulty is high, the number of possible solutions is high, group interest in the problem is high, group familiarity with the problem is low, and the need for solution acceptance is high.

- Scenario 2. Task difficulty is low, the number of possible solutions is low, group interest in the problem is low, group familiarity with the problem is high, and the need for solution acceptance is low.

- Scenario 1: Academic. A professor asks his or her class to decide whether the final exam should be an in-class or take-home exam.

- Scenario 2: Professional. A group of coworkers must decide which person from their department to nominate for a company-wide award.

- Scenario 3: Personal. A family needs to decide how to divide the belongings and estate of a deceased family member who did not leave a will.

- Scenario 4: Civic. A local branch of a political party needs to decide what five key issues it wants to include in the national party’s platform.

- Group communication researchers have found that heterogeneous groups (composed of diverse members) have advantages over homogenous (more similar) groups. Discuss a group situation you have been in where diversity enhanced your and/or the group’s experience.

Adams, K., and Gloria G. Galanes, Communicating in Groups: Applications and Skills , 7th ed. (Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill, 2009), 220–21.

Allen, B. J., Difference Matters: Communicating Social Identity , 2nd ed. (Long Grove, IL: Waveland, 2011), 5.

Bormann, E. G., and Nancy C. Bormann, Effective Small Group Communication , 4th ed. (Santa Rosa, CA: Burgess CA, 1988), 112–13.

Clarke, G., “The Silent Generation Revisited,” Time, June 29, 1970, 46.

Cragan, J. F., and David W. Wright, Communication in Small Group Discussions: An Integrated Approach , 3rd ed. (St. Paul, MN: West Publishing, 1991), 77–78.

de Bono, E., Six Thinking Hats (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1985).

Delbecq, A. L., and Andrew H. Ven de Ven, “A Group Process Model for Problem Identification and Program Planning,” The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 7, no. 4 (1971): 466–92.

Haslett, B. B., and Jenn Ruebush, “What Differences Do Individual Differences in Groups Make?: The Effects of Individuals, Culture, and Group Composition,” in The Handbook of Group Communication Theory and Research , ed. Lawrence R. Frey (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1999), 133.

Napier, R. W., and Matti K. Gershenfeld, Groups: Theory and Experience , 7th ed. (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 2004), 292.

Osborn, A. F., Applied Imagination (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1959).

Spranger, E., Types of Men (New York: Steckert, 1928).

Stanton, C., “How to Deliver Group Presentations: The Unified Team Approach,” Six Minutes Speaking and Presentation Skills , November 3, 2009, accessed August 28, 2012, http://sixminutes.dlugan.com/group-presentations-unified-team-approach .

Thomas, D. C., “Cultural Diversity and Work Group Effectiveness: An Experimental Study,” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 30, no. 2 (1999): 242–63.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.10: Problem Solving and Decision Making

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 41786

Learning Objectives

- Learn to understand the problem.

- Learn to combine creative thinking and critical thinking to solve problems.

- Practice problem solving in a group.

Much of your college and professional life will be spent solving problems; some will be complex, such as deciding on a career, and require time and effort to come up with a solution. Others will be small, such as deciding what to eat for lunch, and will allow you to make a quick decision based entirely on your own experience. But, in either case, when coming up with the solution and deciding what to do, follow the same basic steps.

- Define the problem. Use your analytical skills. What is the real issue? Why is it a problem? What are the root causes? What kinds of outcomes or actions do you expect to generate to solve the problem? What are some of the key characteristics that will make a good choice: Timing? Resources? Availability of tools and materials? For more complex problems, it helps to actually write out the problem and the answers to these questions. Can you clarify your understanding of the problem by using metaphors to illustrate the issue?

- Narrow the problem. Many problems are made up of a series of smaller problems, each requiring its own solution. Can you break the problem into different facets? What aspects of the current issue are “noise” that should not be considered in the problem solution? (Use critical thinking to separate facts from opinion in this step.)

- Generate possible solutions. List all your options. Use your creative thinking skills in this phase. Did you come up with the second “right” answer, and the third or the fourth? Can any of these answers be combined into a stronger solution? What past or existing solutions can be adapted or combined to solve this problem?

Group Think: Effective Brainstorming

Brainstorming is a process of generating ideas for solutions in a group. This method is very effective because ideas from one person will trigger additional ideas from another. The following guidelines make for an effective brainstorming session:

- Decide who should moderate the session. That person may participate, but his main role is to keep the discussion flowing.

- Define the problem to be discussed and the time you will allow to consider it.

- Write all ideas down on a board or flip chart for all participants to see.

- Encourage everyone to speak.

- Do not allow criticism of ideas. All ideas are good during a brainstorm. Suspend disbelief until after the session. Remember a wildly impossible idea may trigger a creative and feasible solution to a problem.

- Choose the best solution. Use your critical thinking skills to select the most likely choices. List the pros and cons for each of your selections. How do these lists compare with the requirements you identified when you defined the problem? If you still can’t decide between options, you may want to seek further input from your brainstorming team.

Decisions, Decisions

You will be called on to make many decisions in your life. Some will be personal, like what to major in, or whether or not to get married. Other times you will be making decisions on behalf of others at work or for a volunteer organization. Occasionally you will be asked for your opinion or experience for decisions others are making. To be effective in all of these circumstances, it is helpful to understand some principles about decision making.

First, define who is responsible for solving the problem or making the decision. In an organization, this may be someone above or below you on the organization chart but is usually the person who will be responsible for implementing the solution. Deciding on an academic major should be your decision, because you will have to follow the course of study. Deciding on the boundaries of a sales territory would most likely be the sales manager who supervises the territories, because he or she will be responsible for producing the results with the combined territories. Once you define who is responsible for making the decision, everyone else will fall into one of two roles: giving input, or in rare cases, approving the decision.

Understanding the role of input is very important for good decisions. Input is sought or given due to experience or expertise, but it is up to the decision maker to weigh the input and decide whether and how to use it. Input should be fact based, or if offering an opinion, it should be clearly stated as such. Finally, once input is given, the person giving the input must support the other’s decision, whether or not the input is actually used.

Consider a team working on a project for a science course. The team assigns you the responsibility of analyzing and presenting a large set of complex data. Others on the team will set up the experiment to demonstrate the hypothesis, prepare the class presentation, and write the paper summarizing the results. As you face the data, you go to the team to seek input about the level of detail on the data you should consider for your analysis. The person doing the experiment setup thinks you should be very detailed, because then it will be easy to compare experiment results with the data. However, the person preparing the class presentation wants only high-level data to be considered because that will make for a clearer presentation. If there is not a clear understanding of the decision-making process, each of you may think the decision is yours to make because it influences the output of your work; there will be conflict and frustration on the team. If the decision maker is clearly defined upfront, however, and the input is thoughtfully given and considered, a good decision can be made (perhaps a creative compromise?) and the team can get behind the decision and work together to complete the project.

Finally, there is the approval role in decisions. This is very common in business decisions but often occurs in college work as well (the professor needs to approve the theme of the team project, for example). Approval decisions are usually based on availability of resources, legality, history, or policy.

Key Takeaways

- Effective problem solving involves critical and creative thinking.

The four steps to effective problem solving are the following:

- Define the problem

- Narrow the problem

- Generate solutions

- Choose the solution

- Brainstorming is a good method for generating creative solutions.

- Understanding the difference between the roles of deciding and providing input makes for better decisions.

Checkpoint Exercises

Gather a group of three or four friends and conduct three short brainstorming sessions (ten minutes each) to generate ideas for alternate uses for peanut butter, paper clips, and pen caps. Compare the results of the group with your own ideas. Be sure to follow the brainstorming guidelines. Did you generate more ideas in the group? Did the quality of the ideas improve? Were the group ideas more innovative? Which was more fun? Write your conclusions here.

__________________________________________________________________

Using the steps outlined earlier for problem solving, write a plan for the following problem: You are in your second year of studies in computer animation at Jefferson Community College. You and your wife both work, and you would like to start a family in the next year or two. You want to become a video game designer and can benefit from more advanced work in programming. Should you go on to complete a four-year degree?

Define the problem: What is the core issue? What are the related issues? Are there any requirements to a successful solution? Can you come up with a metaphor to describe the issue?

Narrow the problem: Can you break down the problem into smaller manageable pieces? What would they be?

Generate solutions: What are at least two “right” answers to each of the problem pieces?

Choose the right approach: What do you already know about each solution? What do you still need to know? How can you get the information you need? Make a list of pros and cons for each solution.

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 6 min read

An Overview of Decision-Making

Techniques and practices to hone your decision making skills.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

Decision-making is one of the most important aspects of a leader’s role, but it can also be one of the most challenging. Here we provide an overview of the processes, techniques and best practice advice that can help leaders hone their decision-making skills and tackle some of the trickier aspects of decision-making more effectively.

The Decision-Making Process

Adopting a structured approach to decision-making can often be a helpful way of navigating some of its potential challenges and pitfalls. The decision-making process consists of four key steps:

1. Define the Decision to Be Made

The first step is to identify exactly what the decision should be about. This involves examining the situation and identifying the core issues or problems at the heart of it. For example, poor sales figures may be symptomatic of a number of different problems: the sales strategy may need revising, managers might need to motivate their teams more effectively or the products or services the organization offers might need to be improved.

It is also important to frame the issue (identify the perspective – or perspectives – from which to view the situation) before moving on to the next stage of the decision-making process. This isn’t always straightforward, as we are all susceptible to biases that can sometimes lead us in the wrong direction.

Prospect theory, devised by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, states that decision-makers respond more strongly to the prospect of losses than gains (this is known as loss aversion ). The theory also says that we tend to overestimate the likelihood of low-probability events, and underestimate the likelihood of high-probability events. [1]

When it comes to framing the issue, it is vital for decision-makers to be aware of these biases and to remain as objective as possible at this early stage of the decision-making process.

2. Identify and Gather Information

There are two main types of information that can assist decision-making: primary sources, which come directly from a person or organization, and secondary sources, which interpret and comment on primary information. Both types can be useful but, by their very nature, secondary sources may not always be as reliable as primary sources, so be sure to select them carefully.

It is also important to be aware of the difference between quantitative and qualitative data. Quantitative data is definable,measurable, and is normally expressed in figures, while qualitative data is descriptive and may involve value judgements or opinions. Quantitative information is often the more efficient and technically accurate of the two, but it can miss contextual data (i.e. it might present an answer or solution, but fail to indicate the reasons behind it). Qualitative information is richer but subjective, and can therefore be less accurate and conclusive than quantitative data.

Depending on the decision-making scenario, it is likely that a combination of primary and secondary information sources that provide both quantitative and qualitative data will be useful. This might involve consulting sources such as:

- internal documents

- external websites

- other people (either internally or in external networks)

- industry magazines, journals or periodicals

- management books

- reference material

- official/government publications and legislation

To assess the validity of the gathered information, it is important to take into account the credibility of the source and the objectivity of the material. It is also vital to consider whether the information is up to date and, above all, whether it is relevant to the decision you are making.

3. Analyze Options and Make a Decision

After gathering the relevant information, the next stage of the process is to identify the options that are available, analyze them, and make a decision. Research conducted at the information-gathering stage might suggest that a certain course of action should be taken or avoided. Alternatively, a new set of solutions might present themselves. All this should be taken into account during the analysis stage.

It is important to consider the potential impact of each option on the whole organization, not just one department or business area. To this end, it might be helpful to seek the input of a colleague, or, if appropriate, a trusted peer or friend from outside the organization, who may be able to offer an objective perspective.

While decision-makers should always spend some time analyzing their options, it is vital to avoid falling into the trap of ‘paralysis by analysis’. After deciding on an appropriate course of action, it is good practice to move onto the next stage of the decision-making process as soon as possible.

4. Communicate and Implement the Decision

On reaching a decision, it is vital to communicate this to everyone involved (e.g. managers, colleagues, customers). Depending on the situation, the decision could be communicated face-to-face, either in team meetings or one-to-one meetings, or via email. The communication should include details of the decision, the reasons it was made, and how it might affect those involved. It is also a good idea to offer individuals the opportunity to ask questions.

It is good practice to treat the implementation of the decision as a small project. When an implementation plan has been identified, it is important to update everyone affected by the decision and let them know what to expect.

Decision-Making Techniques

A range of tools and techniques exist to support every aspect of the decision-making process. Tools such as Implement your Decision (available in the Decision-Making topic) can help decision-makers consider the potential impact of their decision, while the simple checklist can be used to assess whether the information that has been gathered is robust and credible. At the analysis stage of the decision-making process, the Simple Influence Diagrams technique can help decision-makers identify the pros and cons of different options. Plus Minus Implications can be used to support to complex decision-making, and for decisions that require the input of several different stakeholders, techniques such as Critical Decision-Making Techniques and the RAPID Decision-Making can be extremely helpful.

In each decision-making situation, it’s important to use the most appropriate tool. When considering which technique to use, be sure to take into account the nature and complexity of the decision at hand. Remember that decision-making techniques are designed to support decision-making; the outcomes of a technique should be taken into account along with any other information that comes to light during the decision-making process.

Managing Ambiguity

Ambiguity means not knowing exactly what is going to happen. It can occur in almost any aspect of working life and can often have a serious impact on people’s ability to make timely and well-informed decisions. When it comes to managing ambiguity, Philip Hodgson and Randall White, authors of Relax, It’s Only Uncertainty , argue that people’s ability to do this depends on their attitude, behavior and capability. In ambiguous situations, it is important to both remain productive and take steps to reduce the ambiguity wherever possible. This might involve seeking out new information, re-prioritizing tasks or breaking the problem down into smaller components.

You can find further advice and guidance on this aspect of decision-making in The KJ-Method for Establishing Priorities. And you can read an overview of Hodgson and White’s findings in Hodgson and White on Managing Ambiguity.

Beliefs and Biases in Decision-Making

Even when we follow a structured decision-making process, there are a number of innate cognitive biases that can affect our ability to make good decisions. These biases include the ‘bandwagon effect’ (a tendency to do or believe things because many other people do) and ‘confirmation bias’ (the tendency to seek out information that supports our existing beliefs). These biases are innate and everyone is susceptible to them. However, quite often, the best way to avoid these biases (or at least reduce their effects) is to be aware that they exist. Dan Ariely’s Predictably Irrational and Jonah Lehrer’s How We Decide both provide a fascinating insight into the phenomenon of decision-making bias. Audio interviews with each of these authors are available to download from the Decision-Making topic.

While decision-making can be challenging, there are a number of steps that leaders can take to tackle this important aspect of their role successfully. Following each stage of the decision-making process in order, wherever possible, and using the appropriate tools or techniques for each situation will help leaders to approach the different aspects of decision-making effectively. Where ambiguity exists, remaining productive, while taking steps to reduce the level of ambiguity will help to ensure that it doesn’t derail the decision-making process. Meanwhile, being aware of the biases to which everyone is susceptible will prevent them from having an undue influence on the final decision. Adopting this approach will help leaders to make timely, well-informed decisions with confidence.

[1] Amos Tversky & Daniel Kahneman, 'The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice', Science, 211 (1981), p 457.

Join Mind Tools and get access to exclusive content.

This resource is only available to Mind Tools members.

Already a member? Please Login here

Try Mind Tools for FREE

Get unlimited access to all our career-boosting content and member benefits with our 7-day free trial.

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Newest Releases

Team Briefings

Onboarding With STEPS

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

New pain points podcast - perfectionism.

Why Am I Such a Perfectionist?

Pain Points Podcast - Building Trust

Developing and Strengthening Trust at Work

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Get your ideas off the ground.

Turning Ideas Into Reality

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

- INTERPERSONAL SKILLS

- Decision-Making and Problem Solving

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Interpersonal Skills:

- A - Z List of Interpersonal Skills

- Interpersonal Skills Self-Assessment

- Communication Skills

- Emotional Intelligence

- Conflict Resolution and Mediation Skills

- Customer Service Skills

- Team-Working, Groups and Meetings

Decision-Making and Problem-Solving

- Effective Decision Making

- Decision-Making Framework

- Introduction to Problem Solving

Identifying and Structuring Problems

Investigating Ideas and Solutions

Implementing a Solution and Feedback

- Creative Problem-Solving

Social Problem-Solving

- Negotiation and Persuasion Skills

- Personal and Romantic Relationship Skills

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

The SkillsYouNeed Guide to Interpersonal Skills

Making decisions and solving problems are two key areas in life, whether you are at home or at work. Whatever you’re doing, and wherever you are, you are faced with countless decisions and problems, both small and large, every day.

Many decisions and problems are so small that we may not even notice them. Even small decisions, however, can be overwhelming to some people. They may come to a halt as they consider their dilemma and try to decide what to do.

Small and Large Decisions

In your day-to-day life you're likely to encounter numerous 'small decisions', including, for example:

Tea or coffee?

What shall I have in my sandwich? Or should I have a salad instead today?

What shall I wear today?

Larger decisions may occur less frequently but may include:

Should we repaint the kitchen? If so, what colour?

Should we relocate?

Should I propose to my partner? Do I really want to spend the rest of my life with him/her?

These decisions, and others like them, may take considerable time and effort to make.

The relationship between decision-making and problem-solving is complex. Decision-making is perhaps best thought of as a key part of problem-solving: one part of the overall process.

Our approach at Skills You Need is to set out a framework to help guide you through the decision-making process. You won’t always need to use the whole framework, or even use it at all, but you may find it useful if you are a bit ‘stuck’ and need something to help you make a difficult decision.

Decision Making

Effective Decision-Making

This page provides information about ways of making a decision, including basing it on logic or emotion (‘gut feeling’). It also explains what can stop you making an effective decision, including too much or too little information, and not really caring about the outcome.

A Decision-Making Framework

This page sets out one possible framework for decision-making.

The framework described is quite extensive, and may seem quite formal. But it is also a helpful process to run through in a briefer form, for smaller problems, as it will help you to make sure that you really do have all the information that you need.

Problem Solving

Introduction to Problem-Solving

This page provides a general introduction to the idea of problem-solving. It explores the idea of goals (things that you want to achieve) and barriers (things that may prevent you from achieving your goals), and explains the problem-solving process at a broad level.

The first stage in solving any problem is to identify it, and then break it down into its component parts. Even the biggest, most intractable-seeming problems, can become much more manageable if they are broken down into smaller parts. This page provides some advice about techniques you can use to do so.

Sometimes, the possible options to address your problem are obvious. At other times, you may need to involve others, or think more laterally to find alternatives. This page explains some principles, and some tools and techniques to help you do so.

Having generated solutions, you need to decide which one to take, which is where decision-making meets problem-solving. But once decided, there is another step: to deliver on your decision, and then see if your chosen solution works. This page helps you through this process.

‘Social’ problems are those that we encounter in everyday life, including money trouble, problems with other people, health problems and crime. These problems, like any others, are best solved using a framework to identify the problem, work out the options for addressing it, and then deciding which option to use.

This page provides more information about the key skills needed for practical problem-solving in real life.

Further Reading from Skills You Need

The Skills You Need Guide to Interpersonal Skills eBooks.

Develop your interpersonal skills with our series of eBooks. Learn about and improve your communication skills, tackle conflict resolution, mediate in difficult situations, and develop your emotional intelligence.

Guiding you through the key skills needed in life

As always at Skills You Need, our approach to these key skills is to provide practical ways to manage the process, and to develop your skills.

Neither problem-solving nor decision-making is an intrinsically difficult process and we hope you will find our pages useful in developing your skills.

Start with: Decision Making Problem Solving

See also: Improving Communication Interpersonal Communication Skills Building Confidence

Week 8: Critical Thinking

Problem solving and decision making, learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Learn to understand the problem.

- Learn to combine creative thinking and critical thinking to solve problems.

- Practice problem solving in a group.

Much of your college and professional life will be spent solving problems; some will be complex, such as deciding on a career, and require time and effort to come up with a solution. Others will be small, such as deciding what to eat for lunch, and will allow you to make a quick decision based entirely on your own experience. But, in either case, when coming up with the solution and deciding what to do, follow the same basic steps.

- Define the problem. Use your analytical skills. What is the real issue? Why is it a problem? What are the root causes? What kinds of outcomes or actions do you expect to generate to solve the problem? What are some of the key characteristics that will make a good choice: Timing? Resources? Availability of tools and materials? For more complex problems, it helps to actually write out the problem and the answers to these questions. Can you clarify your understanding of the problem by using metaphors to illustrate the issue?

- Narrow the problem. Many problems are made up of a series of smaller problems, each requiring its own solution. Can you break the problem into different facets? What aspects of the current issue are “noise” that should not be considered in the problem solution? (Use critical thinking to separate facts from opinion in this step.)

- Generate possible solutions. List all your options. Use your creative thinking skills in this phase. Did you come up with the second “right” answer, and the third or the fourth? Can any of these answers be combined into a stronger solution? What past or existing solutions can be adapted or combined to solve this problem?

Group Think: Effective Brainstorming

Brainstorming is a process of generating ideas for solutions in a group. This method is very effective because ideas from one person will trigger additional ideas from another. The following guidelines make for an effective brainstorming session:

- Decide who should moderate the session. That person may participate, but his main role is to keep the discussion flowing.

- Define the problem to be discussed and the time you will allow to consider it.

- Write all ideas down on a board or flip chart for all participants to see.

- Encourage everyone to speak.

- Do not allow criticism of ideas. All ideas are good during a brainstorm. Suspend disbelief until after the session. Remember a wildly impossible idea may trigger a creative and feasible solution to a problem.

- Choose the best solution. Use your critical thinking skills to select the most likely choices. List the pros and cons for each of your selections. How do these lists compare with the requirements you identified when you defined the problem? If you still can’t decide between options, you may want to seek further input from your brainstorming team.

Decisions, Decisions

KEY TAKEAWAYs

- Effective problem solving involves critical and creative thinking.

- Define the problem

- Narrow the problem

- Generate solutions

- Choose the solution

- Brainstorming is a good method for generating creative solutions.

- Understanding the difference between the roles of deciding and providing input makes for better decisions.

Checkpoint EXERCISES

- Gather a group of three or four friends and conduct three short brainstorming sessions (ten minutes each) to generate ideas for alternate uses for peanut butter, paper clips, and pen caps. Compare the results of the group with your own ideas. Be sure to follow the brainstorming guidelines. Did you generate more ideas in the group? Did the quality of the ideas improve? Were the group ideas more innovative? Which was more fun? Write your conclusions here.

- Define the problem: What is the core issue? What are the related issues? Are there any requirements to a successful solution? Can you come up with a metaphor to describe the issue?

- Narrow the problem: Can you break down the problem into smaller manageable pieces? What would they be?

- Generate solutions: What are at least two “right” answers to each of the problem pieces?

- Choose the right approach: What do you already know about each solution? What do you still need to know? How can you get the information you need? Make a list of pros and cons for each solution.

- Success in College. Authored by : anonymous. Located at : http://2012books.lardbucket.org/ . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Image of group at table. Authored by : Juhan Sonin. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/6YRkya . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of figure with arrows. Authored by : Impact Hub. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/64TEyQ . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Art of Effective Problem Solving: A Step-by-Step Guide

- Learn Lean Sigma

- Problem Solving

Whether we realise it or not, problem solving skills are an important part of our daily lives. From resolving a minor annoyance at home to tackling complex business challenges at work, our ability to solve problems has a significant impact on our success and happiness. However, not everyone is naturally gifted at problem-solving, and even those who are can always improve their skills. In this blog post, we will go over the art of effective problem-solving step by step.

You will learn how to define a problem, gather information, assess alternatives, and implement a solution, all while honing your critical thinking and creative problem-solving skills. Whether you’re a seasoned problem solver or just getting started, this guide will arm you with the knowledge and tools you need to face any challenge with confidence. So let’s get started!

Table of Contents

Problem solving methodologies.

Individuals and organisations can use a variety of problem-solving methodologies to address complex challenges. 8D and A3 problem solving techniques are two popular methodologies in the Lean Six Sigma framework.

Methodology of 8D (Eight Discipline) Problem Solving:

The 8D problem solving methodology is a systematic, team-based approach to problem solving. It is a method that guides a team through eight distinct steps to solve a problem in a systematic and comprehensive manner.

The 8D process consists of the following steps:

- Form a team: Assemble a group of people who have the necessary expertise to work on the problem.

- Define the issue: Clearly identify and define the problem, including the root cause and the customer impact.

- Create a temporary containment plan: Put in place a plan to lessen the impact of the problem until a permanent solution can be found.

- Identify the root cause: To identify the underlying causes of the problem, use root cause analysis techniques such as Fishbone diagrams and Pareto charts.

- Create and test long-term corrective actions: Create and test a long-term solution to eliminate the root cause of the problem.

- Implement and validate the permanent solution: Implement and validate the permanent solution’s effectiveness.

- Prevent recurrence: Put in place measures to keep the problem from recurring.

- Recognize and reward the team: Recognize and reward the team for its efforts.

Download the 8D Problem Solving Template

A3 Problem Solving Method:

The A3 problem solving technique is a visual, team-based problem-solving approach that is frequently used in Lean Six Sigma projects. The A3 report is a one-page document that clearly and concisely outlines the problem, root cause analysis, and proposed solution.

The A3 problem-solving procedure consists of the following steps:

- Determine the issue: Define the issue clearly, including its impact on the customer.

- Perform root cause analysis: Identify the underlying causes of the problem using root cause analysis techniques.

- Create and implement a solution: Create and implement a solution that addresses the problem’s root cause.

- Monitor and improve the solution: Keep an eye on the solution’s effectiveness and make any necessary changes.

Subsequently, in the Lean Six Sigma framework, the 8D and A3 problem solving methodologies are two popular approaches to problem solving. Both methodologies provide a structured, team-based problem-solving approach that guides individuals through a comprehensive and systematic process of identifying, analysing, and resolving problems in an effective and efficient manner.

Step 1 – Define the Problem