Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

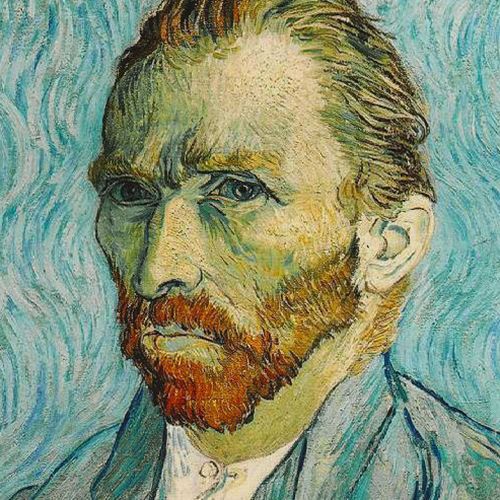

Vincent van gogh (1853–1890).

Road in Etten

Vincent van Gogh

Nursery on Schenkweg

Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat (obverse: The Potato Peeler)

The Potato Peeler (reverse: Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat)

Street in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer

The Flowering Orchard

Peasant Woman Cooking by a Fireplace

Wheat Field with Cypresses

Corridor in the Asylum

L'Arlésienne: Madame Joseph-Michel Ginoux (Marie Julien, 1848–1911)

La Berceuse (Woman Rocking a Cradle; Augustine-Alix Pellicot Roulin, 1851–1930)

Olive Trees

First Steps, after Millet

Department of European Paintings , The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2004 (originally published) March 2010 (last revised)

Vincent van Gogh, the eldest son of a Dutch Reformed minister and a bookseller’s daughter, pursued various vocations, including that of an art dealer and clergyman, before deciding to become an artist at the age of twenty-seven. Over the course of his decade-long career (1880–90), he produced nearly 900 paintings and more than 1,100 works on paper. Ironically, in 1890, he modestly assessed his artistic legacy as of “very secondary” importance.

Largely self-taught, Van Gogh gained his footing as an artist by zealously copying prints and studying nineteenth-century drawing manuals and lesson books, such as Charles Bargue’s Exercises au fusain and cours de dessin . He felt that it was necessary to master black and white before working with color, and first concentrated on learning the rudiments of figure drawing and rendering landscapes in correct perspective. In 1882, he moved from his parents’ home in Etten to the Hague, where he received some formal instruction from his cousin, Anton Mauve, a leading Hague School artist. That same year, he executed his first independent works in watercolor and ventured into oil painting; he also enjoyed his first earnings as an artist: his uncle, the art dealer Cornelis Marinus van Gogh, commissioned two sets of drawings of Hague townscapes for which Van Gogh chose to depict such everyday sites as views of the railway station, gasworks, and nursery gardens ( 1972.118.281 ).

Van Gogh’s admiration for the Barbizon artists, in particular Jean-François Millet, influenced his decision to paint rural life. In the winter of 1884–85, while living with his parents in Nuenen, he painted more than forty studies of peasant heads, which culminated in his first multifigured, large-scale composition ( The Potato Eaters , Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam); in this gritty portrayal of a peasant family at mealtime, Van Gogh wrote that he sought to express that they “have tilled the earth themselves with the same hands they are putting in the dish.” Its dark palette and coarse application of paint typify works from the artist’s Nuenen period ( 67.187.70b ; 1984.393 ).

Interested in honing his skills as a figure painter, Van Gogh left the Netherlands in late 1885 to study at the Antwerp Academy in Belgium. Three months later, he departed for Paris, where he lived with his brother Theo, an art dealer with the firm of Boussod, Valadon et Cie, and for a time attended classes at Fernand Cormon’s studio. Van Gogh’s style underwent a major transformation during his two-year stay in Paris (February 1886–February 1888). There he saw the work of the Impressionists first-hand and also witnessed the latest innovations by the Neo-Impressionists Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. In response, Van Gogh lightened his palette and experimented with the broken brushstrokes of the Impressionists as well as the pointillist touch of the Neo-Impressionists, as evidenced in the handling of his Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat ( 67.187.70a ), which was painted in the summer of 1887 on the reverse of an earlier peasant study ( 67.187.70b ). In Paris, he executed more than twenty self-portraits that reflect his ongoing exploration of complementary color contrasts and a bolder style.

In February 1888, Van Gogh departed Paris for the south of France, hoping to establish a community of artists in Arles. Captivated by the clarity of light and the vibrant colors of the Provençal spring, Van Gogh produced fourteen paintings of orchards in less than a month, painting outdoors and varying his style and technique. The composition and calligraphic handling of The Flowering Orchard ( 56.13 ) suggest the influence of Japanese prints , which Van Gogh collected. The artist’s debt to ukiyo-e prints is also apparent in the reed pen drawings he made in Arles, distinguished by their great verve and linear invention ( 48.190.1 ). In August, he painted the still lifes Oleanders ( 62.24 ) and Shoes ( 1992.374 ); each work resonates with the artist’s personal symbolism. For Van Gogh, oleanders were joyous and life-affirming (much like the sunflower); he reinforced their significance with the compositional prominence accorded to Émile Zola’s 1884 novel La joie de vivre . The still life of unlaced shoes, which Van Gogh had apparently hung in Paul Gauguin ‘s “yellow room” at Arles, suggested, to Gauguin, the artist himself—he saw them as emblematic of Van Gogh’s itinerant existence.

Gauguin joined Van Gogh in Arles in October and abruptly departed in late December 1888, a move precipitated by Van Gogh’s breakdown, during which he cut off part of his left ear with a razor. Upon his return from the hospital in January, he resumed working on a portrait of the wife of the postmaster Joseph Roulin; although he painted all the members of the Roulin family, Van Gogh produced five versions of Madame Roulin as La Berceuse , shown holding the rope that rocks her newborn daughter’s cradle ( 1996.435 ). He envisioned her portrait as the central panel of a triptych, flanked by paintings of sunflowers. For Van Gogh, her image transcended portraiture, symbolically resonating as a modern Madonna; of its palette, which ranges from ocher to vermilion and malachite, Van Gogh expressed his desire that it “sing a lullaby with color,” underscoring the expressive role of color in his art.

Fearing another breakdown, Van Gogh voluntarily entered the asylum at nearby Saint-Rémy in May 1889, where, over the course of the next year, he painted some 150 canvases. His initial confinement to the grounds of the hospital is reflected in his imagery, from his depictions of its corridors ( 48.190.2 ) to the irises and lilacs of its walled garden, visible from the window of the spare room he was allotted to use as a studio. Venturing beyond the grounds of the hospital, he painted the surrounding countryside, devoting series to its olive groves ( 1998.325.1 ) and cypresses, which he saw as characteristic of Provence. In June, he produced two paintings of cypresses, rendered in thick, impastoed layers of paint ( 49.30 ; Cypresses , Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo), likening the form of a cypress to an Egyptian obelisk in a letter to his brother Theo. These evocative trees figure prominently in a landscape, produced the same month ( 1993.132 ). Van Gogh regarded this work, with its sun-drenched wheat field undulating in the wind, as one of his “best” summer canvases. At Saint-Rémy, he also painted copies of works by such artists as Delacroix, Rembrandt , and Millet, using black-and-white photographs and prints. In fall and winter 1889–90, he executed twenty-one copies after Millet ( 64.165.2 ); he described his copies as “interpretations” or “translations,” comparing his role as an artist to that of a musician playing music written by another composer. During his last week at the asylum, he extended his repertoire of still life by painting four bouquets of Irises ( 58.187 ) and Roses ( 1993.400.5 ) as a final series comparable to the sunflower decoration he made earlier in Arles.

After a year at Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh left, in May 1890, to settle in Auvers-sur-Oise, where he was near his brother Theo in Paris and under the care of Dr. Paul Gachet, a homeopathic physician and amateur painter. In just over two months, Van Gogh averaged a painting a day; however, on July 27, 1890, he shot himself in the chest in a wheat field; he died two days later. His artistic legacy is preserved in the paintings and drawings he left behind, as well as in his voluminous correspondence, primarily with Theo, which lays bare his working methods and artistic intentions and serves as a reminder of his brother’s pivotal role as a mainstay of support throughout his career.

By the time of his death in 1890, Van Gogh’s work had begun to attract critical attention. His paintings were featured at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris between 1888 and 1890 and with Les XX in Brussels in 1890. As Gauguin wrote to him, his recent works, on view at the Indépendants in Paris, were regarded by many artists as “the most remarkable” in the show; and one of his paintings sold from the 1890 exhibition in Brussels. In January 1890, the critic Albert Aurier published the first full-length article on Van Gogh, aligning his art with the nascent Symbolist movement and highlighting the originality and intensity of his artistic vision. By the outbreak of World War I, with the discovery of his genius by the Fauves and German Expressionists, Vincent van Gogh had already come to be regarded as a vanguard figure in the history of modern art.

Department of European Paintings. “Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/gogh/hd_gogh.htm (originally published October 2004, last revised March 2010)

Further Reading

Brooks, David. Vincent van Gogh: The Complete Works . CD-ROM. Sharon, Mass.: Barewalls Publications, 2002.

Dorn, Roland, et al. Van Gogh Face to Face: The Portraits . New York: Thames & Hudson, 2000.

Druick, Douglas W., et al. Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Studio of the South . Exhibition catalogue. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2001.

Ives, Colta, et al. Vincent van Gogh: The Drawings . Exhibition catalogue. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005. See on MetPublications

Kendall, Richard. Van Gogh's Van Gogh's: Masterpieces from the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam . Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1998.

The Complete Letters of Vincent van Gogh . 3 vols. Boston: Bullfinch Press, 2000.

Pickvance, Ronald. Van Gogh in Arles . New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1984. See on MetPublications

Pickvance, Ronald. Van Gogh in Saint-Rémy and Auvers . New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986. See on MetPublications

Selected and edited by Ronald de Leeuw. The Letters of Vincent van Gogh . London: Penguin, 2006.

Stein, Susan Alyson, ed. Van Gogh: A Retrospective . New York: New Line Books, 2006.

Stolwijk, Chris, and Richard Thomson. Theo van Gogh . Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 1999.

Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Online resource.

Additional Essays by Department of European Paintings

- Department of European Paintings. “ The Rediscovery of Classical Antiquity .” (October 2002)

- Department of European Paintings. “ Architecture in Renaissance Italy .” (October 2002)

- Department of European Paintings. “ Titian (ca. 1485/90?–1576) .” (October 2003)

- Department of European Paintings. “ The Papacy and the Vatican Palace .” (October 2002)

Related Essays

- Paul Gauguin (1848–1903)

- Post-Impressionism

- The Transformation of Landscape Painting in France

- Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890): The Drawings

- Art of the Pleasure Quarters and the Ukiyo-e Style

- Childe Hassam (1859–1935)

- Claude Monet (1840–1926)

- Édouard Manet (1832–1883)

- Frans Hals (1582/83–1666)

- Georges Seurat (1859–1891) and Neo-Impressionism

- Henri Matisse (1869–1954)

- Impressionism: Art and Modernity

- James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903)

- Landscape Painting in the Netherlands

- The Lure of Montmartre, 1880–1900

- Mary Stevenson Cassatt (1844–1926)

- The Nabis and Decorative Painting

- Paul Cézanne (1839–1906)

- Rembrandt (1606–1669): Paintings

- Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669): Prints

- Woodblock Prints in the Ukiyo-e Style

List of Rulers

- List of Rulers of Europe

- Central Europe and Low Countries, 1800–1900 A.D.

- France, 1800–1900 A.D.

- 19th Century A.D.

- 20th Century A.D.

- Agriculture

- Barbizon School

- Christianity

- Floral Motif

- French Literature / Poetry

- Impressionism

- Literature / Poetry

- Low Countries

- Modern and Contemporary Art

- Neo-Impressionism

- The Netherlands

- Oil on Canvas

- Plant Motif

- Pointillism

- Printmaking

- Religious Art

- Self-Portrait

Artist or Maker

- Delacroix, Eugène

- Gauguin, Paul

- Millet, Jean-François

- Seurat, Georges

- Signac, Paul

- Van Gogh, Vincent

- Van Rijn, Rembrandt

Online Features

- The Artist Project: “Sopheap Pich on Vincent van Gogh’s drawings”

- Connections: “Clouds” by Keith Christiansen

- Connections: “Dutch” by Merantine Hens

Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh was one of the world’s greatest artists, with paintings such as ‘Starry Night’ and ‘Sunflowers,’ though he was unknown until after his death.

(1853-1890)

Who Was Vincent van Gogh?

Vincent van Gogh was a post-Impressionist painter whose work — notable for its beauty, emotion and color — highly influenced 20th-century art. He struggled with mental illness and remained poor and virtually unknown throughout his life.

Early Life and Family

Van Gogh was born on March 30, 1853, in Groot-Zundert, Netherlands. Van Gogh’s father, Theodorus van Gogh, was an austere country minister, and his mother, Anna Cornelia Carbentus, was a moody artist whose love of nature, drawing and watercolors was transferred to her son.

Van Gogh was born exactly one year after his parents' first son, also named Vincent, was stillborn. At a young age — with his name and birthdate already etched on his dead brother's headstone — van Gogh was melancholy.

Theo van Gogh

The eldest of six living children, van Gogh had two younger brothers (Theo, who worked as an art dealer and supported his older brother’s art, and Cor) and three younger sisters (Anna, Elizabeth and Willemien).

Theo van Gogh would later play an important role in his older brother's life as a confidant, supporter and art dealer.

Early Life and Education

At age 15, van Gogh's family was struggling financially, and he was forced to leave school and go to work. He got a job at his Uncle Cornelis' art dealership, Goupil & Cie., a firm of art dealers in The Hague. By this time, van Gogh was fluent in French, German and English, as well as his native Dutch.

He also fell in love with his landlady's daughter, Eugenie Loyer. When she rejected his marriage proposal, van Gogh suffered a breakdown. He threw away all his books except for the Bible, and devoted his life to God. He became angry with people at work, telling customers not to buy the "worthless art," and was eventually fired.

Life as a Preacher

Van Gogh then taught in a Methodist boys' school, and also preached to the congregation. Although raised in a religious family, it wasn't until this time that he seriously began to consider devoting his life to the church

Hoping to become a minister, he prepared to take the entrance exam to the School of Theology in Amsterdam. After a year of studying diligently, he refused to take the Latin exams, calling Latin a "dead language" of poor people, and was subsequently denied entrance.

The same thing happened at the Church of Belgium: In the winter of 1878, van Gogh volunteered to move to an impoverished coal mine in the south of Belgium, a place where preachers were usually sent as punishment. He preached and ministered to the sick, and also drew pictures of the miners and their families, who called him "Christ of the Coal Mines."

The evangelical committees were not as pleased. They disagreed with van Gogh's lifestyle, which had begun to take on a tone of martyrdom. They refused to renew van Gogh's contract, and he was forced to find another occupation.

Finding Solace in Art

In the fall of 1880, van Gogh decided to move to Brussels and become an artist. Though he had no formal art training, his brother Theo offered to support van Gogh financially.

He began taking lessons on his own, studying books like Travaux des champs by Jean-François Millet and Cours de dessin by Charles Bargue.

Van Gogh's art helped him stay emotionally balanced. In 1885, he began work on what is considered to be his first masterpiece, "Potato Eaters." Theo, who by this time living in Paris, believed the painting would not be well-received in the French capital, where Impressionism had become the trend.

Nevertheless, van Gogh decided to move to Paris, and showed up at Theo's house uninvited. In March 1886, Theo welcomed his brother into his small apartment.

In Paris, van Gogh first saw Impressionist art, and he was inspired by the color and light. He began studying with Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec , Camille Pissarro and others.

To save money, he and his friends posed for each other instead of hiring models. Van Gogh was passionate, and he argued with other painters about their works, alienating those who became tired of his bickering.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S VINCENT VAN GOGH FACT CARD

Van Gogh's love life was nothing short of disastrous: He was attracted to women in trouble, thinking he could help them. When he fell in love with his recently widowed cousin, Kate, she was repulsed and fled to her home in Amsterdam.

Van Gogh then moved to The Hague and fell in love with Clasina Maria Hoornik, an alcoholic prostitute. She became his companion, mistress and model.

When Hoornik went back to prostitution, van Gogh became utterly depressed. In 1882, his family threatened to cut off his money unless he left Hoornik and The Hague.

Van Gogh left in mid-September of that year to travel to Drenthe, a somewhat desolate district in the Netherlands. For the next six weeks, he lived a nomadic life, moving throughout the region while drawing and painting the landscape and its people.

Van Gogh became influenced by Japanese art and began studying Eastern philosophy to enhance his art and life. He dreamed of traveling there, but was told by Toulouse-Lautrec that the light in the village of Arles was just like the light in Japan.

In February 1888, van Gogh boarded a train to the south of France. He moved into a now-famous "yellow house" and spent his money on paint rather than food.

Vincent van Gogh completed more than 2,100 works, consisting of 860 oil paintings and more than 1,300 watercolors, drawings and sketches.

Several of his paintings now rank among the most expensive in the world; "Irises" sold for a record $53.9 million, and his "Portrait of Dr. Gachet" sold for $82.5 million. A few of van Gogh’s most well-known artworks include:

'Starry Night'

Van Gogh painted "The Starry Night" in the asylum where he was staying in Saint-Rémy, France, in 1889, the year before his death. “This morning I saw the countryside from my window a long time before sunrise, with nothing but the morning star, which looked very big,” he wrote to his brother Theo.

A combination of imagination, memory, emotion and observation, the oil painting on canvas depicts an expressive swirling night sky and a sleeping village, with a large flame-like cypress, thought to represent the bridge between life and death, looming in the foreground. The painting is currently housed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, NY.

'Sunflowers'

Van Gogh painted two series of sunflowers in Arles, France: four between August and September 1888 and one in January 1889; the versions and replicas are debated among art historians.

The oil paintings on canvas, which depict wilting yellow sunflowers in a vase, are now displayed at museums in London, Amsterdam, Tokyo, Munich and Philadelphia.

In 1889, after entering an asylum in Saint-Rémy, France, van Gogh began painting Irises, working from the plants and flowers he found in the asylum's garden. Critics believe the painting was influenced by Japanese woodblock prints.

French critic Octave Mirbeau, the painting's first owner and an early supporter of Van Gogh, remarked, "How well he has understood the exquisite nature of flowers!"

'Self-Portrait'

Over the course of 10 years, van Gogh created more than 43 self-portraits as both paintings and drawings. "I am looking for a deeper likeness than that obtained by a photographer," he wrote to his sister.

"People say, and I am willing to believe it, that it is hard to know yourself. But it is not easy to paint yourself, either. The portraits painted by Rembrandt are more than a view of nature, they are more like a revelation,” he later wrote to his brother.

Van Gogh's self-portraits are now displayed in museums around the world, including in Washington, D.C., Paris, New York and Amsterdam.

Van Gogh's Ear

In December 1888, van Gogh was living on coffee, bread and absinthe in Arles, France, and he found himself feeling sick and strange.

Before long, it became apparent that in addition to suffering from physical illness, his psychological health was declining. Around this time, he is known to have sipped on turpentine and eaten paint.

His brother Theo was worried, and he offered Paul Gauguin money to go watch over Vincent in Arles. Within a month, van Gogh and Gauguin were arguing constantly, and one night, Gauguin walked out. Van Gogh followed him, and when Gauguin turned around, he saw van Gogh holding a razor in his hand.

Hours later, van Gogh went to the local brothel and paid for a prostitute named Rachel. With blood pouring from his hand, he offered her his ear, asking her to "keep this object carefully."

The police found van Gogh in his room the next morning, and admitted him to the Hôtel-Dieu hospital. Theo arrived on Christmas Day to see van Gogh, who was weak from blood loss and having violent seizures.

The doctors assured Theo that his brother would live and would be taken good care of, and on January 7, 1889, van Gogh was released from the hospital.

He remained, however, alone and depressed. For hope, he turned to painting and nature, but could not find peace and was hospitalized again. He would paint at the yellow house during the day and return to the hospital at night.

Van Gogh decided to move to the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence after the people of Arles signed a petition saying that he was dangerous.

On May 8, 1889, he began painting in the hospital gardens. In November 1889, he was invited to exhibit his paintings in Brussels. He sent six paintings, including "Irises" and "Starry Night."

On January 31, 1890, Theo and his wife, Johanna, gave birth to a boy and named him Vincent Willem van Gogh after Theo's brother. Around this time, Theo sold van Gogh's "The Red Vineyards" painting for 400 francs.

Also around this time, Dr. Paul Gachet, who lived in Auvers, about 20 miles north of Paris, agreed to take van Gogh as his patient. Van Gogh moved to Auvers and rented a room.

On July 27, 1890, Vincent van Gogh went out to paint in the morning carrying a loaded pistol and shot himself in the chest, but the bullet did not kill him. He was found bleeding in his room.

Van Gogh was distraught about his future because, in May of that year, his brother Theo had visited and spoke to him about needing to be stricter with his finances. Van Gogh took that to mean Theo was no longer interested in selling his art.

Van Gogh was taken to a nearby hospital and his doctors sent for Theo, who arrived to find his brother sitting up in bed and smoking a pipe. They spent the next couple of days talking together, and then van Gogh asked Theo to take him home.

On July 29, 1890, Vincent van Gogh died in the arms of his brother Theo. He was only 37 years old.

Theo, who was suffering from syphilis and weakened by his brother's death, died six months after his brother in a Dutch asylum. He was buried in Utrecht, but in 1914 Theo's wife, Johanna, who was a dedicated supporter of van Gogh's works, had Theo's body reburied in the Auvers cemetery next to Vincent.

Theo's wife Johanna then collected as many of van Gogh's paintings as she could, but discovered that many had been destroyed or lost, as van Gogh's own mother had thrown away crates full of his art.

On March 17, 1901, 71 of van Gogh's paintings were displayed at a show in Paris, and his fame grew enormously. His mother lived long enough to see her son hailed as an artistic genius. Today, Vincent van Gogh is considered one of the greatest artists in human history.

Van Gogh Museum

In 1973, the Van Gogh Museum opened its doors in Amsterdam to make the works of Vincent van Gogh accessible to the public. The museum houses more than 200 van Gogh paintings, 500 drawings and 750 written documents including letters to Vincent’s brother Theo. It features self-portraits, “The Potato Eaters,” “The Bedroom” and “Sunflowers.”

In September 2013, the museum discovered and unveiled a van Gogh painting of a landscape entitled "Sunset at Montmajour.” Before coming under the possession of the Van Gogh Museum, a Norwegian industrialist owned the painting and stored it away in his attic, having thought that it wasn't authentic.

The painting is believed to have been created by van Gogh in 1888 — around the same time that his artwork "Sunflowers" was made — just two years before his death.

Watch "Vincent Van Gogh: A Stroke of Genius" on HISTORY Vault

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Vincent van Gogh

- Birth Year: 1853

- Birth date: March 30, 1853

- Birth City: Zundert

- Birth Country: Netherlands

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Vincent van Gogh was one of the world’s greatest artists, with paintings such as ‘Starry Night’ and ‘Sunflowers,’ though he was unknown until after his death.

- Astrological Sign: Aries

- Brussels Academy

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- Some of van Gogh's most famous works include "Starry Night," "Irises," and "Sunflowers."

- In a moment of instability, Vincent Van Gogh cut off his ear and offered it to a prostitute.

- Van Gogh died in France at age 37 from a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

- Death Year: 1890

- Death date: July 29, 1890

- Death City: Auvers-sur-Oise

- Death Country: France

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Vincent van Gogh Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/artists/vincent-van-gogh

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: March 4, 2020

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- As for me, I am rather often uneasy in my mind, because I think that my life has not been calm enough; all those bitter disappointments, adversities, changes keep me from developing fully and naturally in my artistic career.

- I am a fanatic! I feel a power within me…a fire that I may not quench, but must keep ablaze.

- I get very cross when people tell me that it is dangerous to put out to sea. There is safety in the very heart of danger.

- I want to paint what I feel, and feel what I paint.

- As my work is, so am I.

- The love of art is the undoing of true love.

- When one has fire within oneself, one cannot keep bottling [it] up—better to burn than to burst. What is in will out.

- For my part I know nothing with any certainty, but the sight of the stars makes me dream.

- I do not say that my work is good, but it's the least bad that I can do. All the rest, relations with people, is very secondary, because I have no talent for that. I can't help it.

- What is wrought in sorrow lives for all time.

- What I draw, I see clearly. In these [drawings] I can talk with enthusiasm. I have found a voice.

- Enjoy yourself too much rather than too little, and don't take art or love too seriously.

- But I always think that the best way to know God is to love many things.

Famous Painters

11 Notable Artists from the Harlem Renaissance

Fernando Botero

Gustav Klimt

The Surreal Romance of Salvador and Gala Dalí

Salvador Dalí

Margaret Keane

Andy Warhol

Vincent van Gogh

Vincent Willem van Gogh ( Dutch: [ˈvɪnsɛnt ˈʋɪləɱ‿vɑŋ‿ˈɣɔx] ; 30 March 1853 – 29 July 1890) was a Dutch Post-Impressionist painter who is among the most famous and influential figures in the history of Western art. In just over a decade, he created approximately 2100 artworks, including around 860 oil paintings, most of them in the last two years of his life. His oeuvre includes landscapes, still lifes, portraits, and self-portraits, most of which are characterized by bold colors and dramatic brushwork that contributed to the rise of expressionism in modern art. Van Gogh's work was beginning to gain critical attention before he died from a self-inflicted gunshot at age 37. During his lifetime, only one of Van Gogh's paintings, The Red Vineyard , was sold.

Born into an upper-middle-class family, Van Gogh drew as a child and was serious, quiet and thoughtful, but showed signs of mental instability. As a young man, he worked as an art dealer, often travelling, but became depressed after he was transferred to London. He turned to religion and spent time as a missionary in southern Belgium. Later he drifted into ill-health and solitude. He was keenly aware of modernist trends in art and, while back with his parents, took up painting in 1881. His younger brother, Theo, supported him financially, and the two of them maintained a long correspondence.

Van Gogh's early works consist of mostly still lifes and depictions of peasant laborers. In 1886, he moved to Paris, where he met members of the artistic avant-garde , including Émile Bernard and Paul Gauguin, who were seeking new paths beyond Impressionism. Frustrated in Paris and inspired by a growing spirit of artistic change and collaboration, in February 1888, Van Gogh moved to Arles in southern France to establish an artistic retreat and commune. Once there, Van Gogh's art changed. His paintings grew brighter and he turned his attention to the natural world, depicting local olive groves, wheat fields and sunflowers. Van Gogh invited Gauguin to join him in Arles and eagerly anticipated Gauguin's arrival in the fall of 1888.

Van Gogh suffered from psychotic episodes and delusions. Though he worried about his mental stability, he often neglected his physical health, did not eat properly and drank heavily. His friendship with Gauguin ended after a confrontation with a razor when, in a rage, he severed his left ear. Van Gogh spent time in psychiatric hospitals, including a period at Saint-Rémy. After he discharged himself and moved to the Auberge Ravoux in Auvers-sur-Oise near Paris, he came under the care of the homeopathic doctor Paul Gachet. His depression persisted, and on 27 July 1890, Van Gogh is believed to have shot himself in the chest with a revolver, dying from his injuries two days later.

Van Gogh's work began to attract critical artistic attention in the last year of his life. After his death, Van Gogh's art and life story captured public imagination as an emblem of misunderstood genius, due in large part to the efforts of his widowed sister-in-law Johanna van Gogh-Bonger. His bold use of color, expressive line and thick application of paint inspired avant-garde artistic groups like the Fauves and German Expressionists in the early 20th century. Van Gogh's work gained widespread critical and commercial success in the following decades, and he has become a lasting icon of the romantic ideal of the tortured artist. Today, Van Gogh's works are among the world's most expensive paintings ever sold. His legacy is honored and celebrated by the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, which holds the world's largest collection of his paintings and drawings.

This biography is from Wikipedia under an Attribution-ShareAlike Creative Commons License . Spotted a problem? Let us know .

Farms near Auvers

The oise at auvers, thatched roofs, a corner of the garden of st paul’s hospital at st rémy, artist as subject, study for ‘portrait of van gogh iv’, distinguished visitors at the tate, film and audio.

Van Gogh: Challenging the Myth of the 'Tortured Genius'

Seven Things to Know about Vincent van Gogh’s Time in Britain

The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain

Vincent van gogh: the pilgrim painter.

Iain Sinclair

In the shop

Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh. Self-Portrait , 1887. Joseph Winterbotham Collection.

During Vincent van Gogh’s tumultuous career as a painter, he created a revolutionary style characterized by exaggerated forms, a vivid color palette, and loose, spontaneous handling of paint. Although he only actively pursued his art for five years before his death in 1890, his impact has lived on through his works.

In 1886 Van Gogh left his native Holland and settled in Paris, where his beloved brother, Theo, was a paintings dealer. In the two years he spent in Paris, Van Gogh painted no fewer than two dozen self-portraits. The Art Institute’s early, modestly sized example displays the bright palette he adopted with an overlay of small, even brushstrokes, a response to the Pointillist technique Georges Seurat used, most notably in A Sunday on La Grande Jatte—1884 . Works such as Fishing in Spring, the Pont de Clichy (Asnières) ; Grapes, Lemons, Pears, and Apples ; and Cypresses show the influence of the Impressionists.

Exhausted with the Parisian city life, Van Gogh moved on to the town of Arles in 1888. It was here that he created compositions of such personal importance that he repeated them several times, such as The Bedroom and Madame Roulin Rocking the Cradle (La berceuse) , with slight variations on each repetition.

After experiencing several bouts of mental illness, at the time diagnosed as epilepsy, Van Gogh was admitted to the Asylum of Saint Paul in Saint-Rémy. There he sketched and painted the grounds of the asylum and the town around him. On days when he was unable to go out, he copied works by other artists, such as The Drinkers , after a wood engraving of the same title by Honoré Daumier.

Van Gogh spent the last few months of his life in Auvers-sur-Oise, a small town to the north of Paris. Here, he continued drawing and painting the town and those around him, capturing people, landscapes, houses, and flowers in his work until his untimely death. The Art Institute of Chicago has celebrated van Gogh’s path-breaking work in the exhibitions Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Studio of the South (2001–2002) and Van Gogh’s Bedrooms (2016).

- The Bedroom, 1889 Vincent van Gogh

- Self-Portrait, 1887 Vincent van Gogh

- The Poet’s Garden, 1888 Vincent van Gogh

- A Peasant Woman Digging in Front of Her Cottage, c. 1885 Vincent van Gogh

- The Drinkers, 1890 Vincent van Gogh

- Fishing in Spring, the Pont de Clichy (Asnières), 1887 Vincent van Gogh

- Madame Roulin Rocking the Cradle (La berceuse), 1889 Vincent van Gogh

- Terrace and Observation Deck at the Moulin de Blute-Fin, Montmartre, early 1887 Vincent van Gogh

- Grapes, Lemons, Pears, and Apples, 1887 Vincent van Gogh

- Weeping Tree, 1889 Vincent van Gogh

- Weeping Woman, 1883 Vincent van Gogh

- Tetards (Pollards), 1884 Vincent van Gogh

Related Content

- Article On the Wall of Van Gogh’s Bedroom

Throbbing with the hum of life, this garden is as inviting as the artist’s iconic bedroom. Curator Kevin Salatino tells us why.

- Exhibition Closed Van Gogh’s Bedrooms Feb 14 – May 10, 2016

- Exhibition Closed Van Gogh: In Search Of Feb 16 – May 9, 2016

- Exhibition Closed Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Studio of the South Sep 22, 2001 – Jan 13, 2002

- Exhibition Closed Cézanne to Picasso: Ambroise Vollard, Patron of the Avant-Garde Feb 17 – May 13, 2007

- Exhibition Closed Toulouse-Lautrec and Montmartre Jul 16 – Oct 10, 2005

- Print Publication Van Gogh’s Bedrooms

- Print Publication Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Studio of the South

- Exhibition Closed Van Gogh and the Avant-Garde: The Modern Landscape May 14 – Sep 4, 2023

- Exhibition Closed Pure Drawing: Seven Centuries of Art from the Gray Collection Jan 25–Mar 13, 2020 | July 30–Oct 12, 2020

Explore Further

Related artworks.

- Woman and Child at the Well, 1882 Camille Pissarro

- Young Peasant Having Her Coffee, 1881 Camille Pissarro

- Arlésiennes (Mistral), 1888 Paul Gauguin

- Woman in Front of a Still Life by Cezanne, 1890 Paul Gauguin

- Oil Sketch for “A Sunday on La Grande Jatte — 1884”, 1884 Georges Seurat

- Portrait of Jeanne Wenz, 1886 Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

- A Sunday on La Grande Jatte — 1884, 1884/86 Georges Seurat

- The Plate of Apples, c. 1877 Paul Cezanne

- The Bay of Marseille, Seen from L’Estaque, c. 1885 Paul Cezanne

- Still Life: Wood Tankard and Metal Pitcher, 1880 Paul Gauguin

- Moulin de la Galette, 1889 Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

- Landscape: Window Overlooking the Woods, 1899 Édouard Jean Vuillard

- The Red Room, Etretat, 1899 Félix Edouard Vallotton

Sign up for our enewsletter to receive updates.

- News and Exhibitions Career Opportunities Families

- Public Programs K-12 Educator Resources Teen Opportunities Research, Publishing, and Conservation

Gallery actions

Image actions, suggested terms.

- Free Admission

- My Museum Tour

- What to See in an Hour

- Share full article

The Great Read Feature

The Woman Who Made van Gogh

Neglected by art history for decades, Jo van Gogh-Bonger, the painter’s sister-in-law, is finally being recognized as the force who opened the world’s eyes to his genius.

Jo Bonger, at about 21. Credit... F. W. Deutmann, Zwolle. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Supported by

By Russell Shorto

- Published April 14, 2021 Updated June 15, 2023

Listen to This Article

In 1885, a 22-year-old Dutch woman named Johanna Bonger met Theo van Gogh, the younger brother of the artist, who was then making a name for himself as an art dealer in Paris. History knows Theo as the steadier of the van Gogh brothers, the archetypal emotional anchor, who selflessly managed Vincent’s erratic path through life, but he had his share of impetuosity. He asked her to marry him after only two meetings.

Jo, as she called herself, was raised in a sober, middle-class family. Her father, the editor of a shipping newspaper that reported on things like the trade in coffee and spices from the Far East, imposed a code of propriety and emotional aloofness on his children. There is a Dutch maxim, “The tallest nail gets hammered down,” that the Bonger family seems to have taken as gospel. Jo had set herself up in a safely unexciting career as an English teacher in Amsterdam. She wasn’t inclined to impulsiveness. Besides, she was already dating somebody. She said no.

But Theo persisted. He was attractive in a soulful kind of way — a thinner, paler version of his brother. Beyond that, she had a taste for culture, a desire to be in the company of artists and intellectuals, which he could certainly provide. Eventually he won her over. In 1888, a year and a half after his proposal, she agreed to marry him. After that, a new life opened up for her. It was Paris in the belle epoque: art, theater, intellectuals, the streets of their Pigalle neighborhood raucous with cafes and brothels. Theo was not just any art dealer. He was at the forefront, specializing in the breed of young artists who were defying the stony realism imposed by the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Most dealers wouldn’t touch the Impressionists, but they were Theo van Gogh’s clients and heroes. And here they came, Gauguin and Pissarro and Toulouse-Lautrec, the young men of the avant-garde, marching through her life with the exotic ferocity of zoo creatures.

Jo realized that she was in the midst of a movement, that she was witnessing a change in the direction of things. At home, too, she was feeling fully alive. On their marriage night, which she described as “blissful,” her husband thrilled her by whispering into her ear, “Wouldn’t you like to have a baby, my baby?” She was powerfully in love: with Theo, with Paris, with life.

Theo talked incessantly — of their future, and also of things like pigment and color and light, encouraging her to develop a new way of seeing. But one subject dominated. From their first meeting, he regaled Jo with accounts of his brother’s tortured genius. Their apartment was crammed with Vincent’s paintings, and new crates arrived all the time. Vincent, who spent much of his brief career in motion, in France, Belgium, England, the Netherlands, was churning out canvases at a fanatical pace, sometimes one a day — olive trees, wheat fields, peasants under a Provençal sun, yellow skies, peach blossoms, gnarled trunks, clods of soil like the tops of waves, poplar trees like tongues of flame — and shipping them to Theo in hopes he would find a market for them. Theo had little success attracting buyers, but Vincent’s works, three-dimensionally thick with their violent daubs of oil paint, became the source material for Jo’s education in modern art.

When, a little more than nine months after their wedding night, Jo gave birth to a son, she agreed to the name Theo proffered. They would call the boy Vincent.

As much as he looked up to his brother, Theo also fretted constantly about him. Vincent’s mental state had already deteriorated by the time Jo came on the scene. He had slept outside in winter to mortify his flesh, gorged on alcohol, coffee and tobacco to heighten or numb his senses, become riddled with gonorrhea, stopped bathing, let his teeth rot. He had distanced himself from artists and others who might have helped his career. Just before Christmas in 1888, while Theo and Jo were announcing their engagement, Vincent was in Arles cutting off his ear following a series of rows with his housemate Paul Gauguin.

One day a canvas arrived that showed a shift in style. Vincent had been fascinated by the night sky in Arles. He tried to put it into words for Theo: “In the blue depth the stars were sparkling, greenish, yellow, white, pink, more brilliant, more emeralds, lapis lazuli, rubies, sapphires.” He became fixated on the idea of painting such a sky. He read Walt Whitman, whose work was especially popular in France, and interpreted the poet as equating “the great starry firmament” with “God and eternity.”

Vincent sent the finished painting to Theo and Jo with a note explaining that it was an “exaggeration.” “The Starry Night” continued his progression away from realism; the brush strokes were like troughs made by someone who was digging for something deeper. Theo found it disturbing — he could sense his brother drifting away, and he knew buyers weren’t likely to understand it. He wrote back: “I consider that you’re strongest when you’re doing real things.” But he enclosed another 150 francs for expenses.

Then, in the spring of 1890, news: Vincent was coming to Paris. Jo expected an enfeebled mental patient. Instead, she was confronted by the physical embodiment of the spirit that animated the canvases that covered their walls. “Before me was a sturdy, broad-shouldered man with a healthy color, a cheerful look in his eyes and something very resolute in his appearance,” she wrote in her journal. “ ‘He looks much stronger than Theo,’ was my first thought.” He charged out into the arrondissement to buy olives he loved and came back insisting that they taste them. He stood before the canvases he had sent and studied each with great intensity. Theo led him to the room where the baby lay sleeping, and Jo watched as the brothers gazed into the crib. “They both had tears in their eyes,” she wrote.

What happened next was like two blows of a hammer. Theo had arranged for Vincent to stay in the village of Auvers-sur-Oise to the north of Paris, in the care of Dr. Paul Gachet, whose homeopathic approach he hoped would help his brother’s condition. Weeks later came news that Vincent had shot himself (some biographers dispute the notion that his wound was self-inflicted). Theo arrived in the village in time to watch his brother die. Theo was devastated. He had supported his brother financially and emotionally through his brief, 10-year career, an effort to produce, as Vincent once wrote him, “something serious, something fresh — something with soul in it,” art that would reveal nothing less than “what there is in the heart of ... a nobody.” Less than three months after Vincent’s death, Theo suffered a complete physical collapse, the latter stages of syphilis he had contracted from earlier visits to brothels. He began hallucinating. His agony was tremendous and ghoulish. He died in January 1891.

Twenty-one months after her marriage, Jo was alone, stunned at the fecund dose of life she had just experienced, and at what was left to her from that life: approximately 400 paintings and several hundred drawings by her brother-in-law.

The brothers’ dying so young, Vincent at 37 and Theo at 33, and without the artist having achieved renown — Theo had managed to sell only a few of his paintings — would seem to have ensured that Vincent van Gogh’s work would subsist eternally in a netherworld of obscurity. Instead, his name, art and story merged to form the basis of an industry that stormed the globe, arguably surpassing the fame of any other artist in history. That happened in large part thanks to Jo van Gogh-Bonger. She was small in stature and riddled with self-doubt, had no background in art or business and faced an art world that was a thoroughly male preserve. Her full story has only recently been uncovered. It is only now that we know how van Gogh became van Gogh.

Long before Covid-19, Hans Luijten was in the habit of likening Vincent van Gogh to a virus. “If that virus comes into your life, it never goes away,” he said in his bright, modern Amsterdam apartment when we first spoke in April 2020, and added with a note of warning in his voice: “There’s no vaccine for it.” Luijten is 60, slim, with wire-rimmed glasses, floating tufts of gray hair and a strong penchant for American roots music: gospel, Dolly Parton, Justin Townes Earle. He was born in the southern part of the Netherlands, near the Belgian border. Both his parents made shoes for a living — his father in a factory, his mother with a sewing machine in their home — which gave him a respect for hard work and an eye for footwear: “I can’t meet a person without looking down at the feet.”

Despite the fact that there wasn’t a single book in the family house, his parents encouraged Luijten and his brother to follow their highbrow dreams, which turned out to parallel each other. Ger Luijten, five years Hans’s senior, studied art history and is now director of Fondation Custodia, an art museum in Paris. Hans majored in Dutch literature and minored in art history. After getting his doctorate, he heard that the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam wanted to develop a new critical edition of the 902 letters in the Vincent van Gogh correspondence, including those that he and Theo exchanged. In 1994 he was hired as a researcher and spent the next 15 years on that work.

In the process, Luijten developed a particular affinity for the artist. He can speak fluently about the paintings, but it’s in Vincent’s letters that he found another layer of insight. “He worked them very carefully. If you read the published letters, he might say, ‘The deep gray sky. ... ’ But if you look at the handwritten letter, you see he added ‘gray’ and then ‘deep.’ Like he was adding brush strokes. You can see in both his art and writing that he looked at the world as if everything was alive and aware. He treated a tree the same as a human being.”

Luijten is a dogged researcher, the kind who will hunt down slips of paper moldering in archives from Paris to New York, who derives meaning not just from what words in a document say but also from how they are written: “You can see emotion in Van Gogh’s handwriting: doubt, anger. I could tell when he had been drinking, because he started with huge letters, and they would become smaller and smaller as he got to the bottom of the page.”

The end result of this exhaustive research project, which went on far longer than Vincent’s career did, is “Vincent van Gogh: The Letters.” It runs to six volumes and more than 2,000 pages and was published in 2009. An online edition features the original Dutch or French together with an English translation, annotations, facsimiles of the original letters and images of artworks discussed. Leo Jansen, who toiled alongside Luijten for all of those 15 years and who now works at the Huygens Institute for the History of the Netherlands, told me that as they neared the end of the van Gogh project, he sensed that Luijten was beginning to formulate a new idea. “I think Hans realized that, while we were at last delivering Vincent’s letters, that project was only just a start, because Vincent wasn’t even known at the end of his life.”

Which raised a question that had never been completely answered: How exactly did the tortured genius, who alienated dealers and otherwise thwarted his own ambition time and again during his career, become a star? And not just a star, but one of the most beloved figures in the history of art?

Jo van Gogh-Bonger was previously known to have played a role in building the painter’s reputation, but that role was thought to have been modest — a presumption seemingly based on a combination of sexism and common sense, since she had no background in the art business. There were intriguing indications for those interested enough to look. In 2003, the Dutch writer Bas Heijne found himself in the Van Gogh Museum’s library and stumbled across some letters, which prompted him to write a play about Jo. “I just thought, This woman’s life is a great story,” he says. Luijten likewise told me that the letters between the brothers, and those exchanged with other artists and dealers, were littered with clues. He searched the museum’s library and archives and found photographs and account books that contained more hints. He corresponded with archives in France, Denmark and the United States. He began to formulate a thesis: “I started to see that she was the spider in the web. She had a strategy.”

There was another source, a potential holy grail, which he believed might advance his thesis but to which researchers had been denied access. Luijten knew Jo had kept a diary. His interest was piqued in part by the very fact that he hadn’t been able to read it — the van Gogh family had kept it under lock and key since her death in 1925. “I don’t think they were unwilling to acknowledge her role,” Luijten told me. “I think it was out of modesty.” Jo’s son, Vincent, didn’t want the world to know of his mother’s later relationship with another Dutch painter, didn’t want her privacy to be violated. The diary remained under embargo until, in 2009, Luijten asked Jo’s grandson, Johan van Gogh, if he could see it, and Johan granted his wish. ( Jo’s diaries and other materials are now available via the Van Gogh Museum’s website and library.)

The very first entry in the diary — which turned out to be a collection of simple lined notebooks of the kind used by schoolchildren — intrigued Luijten. Jo started it when she was 17, five years before she met Theo. A young woman of that era could look forward to only very narrow options in life, yet here she wrote, “I would think it dreadful to have to say at the end of my life, ‘I’ve actually lived for nothing, I have achieved nothing great or noble.’” “That, to me, was actually very exciting,” Luijten says. It was a clue: She was not content to follow her family’s maxim after all.

In 2009 Luijten began writing a biography of Jo, working in an office in a former schoolhouse opposite the greensward of Amsterdam’s Museum Square. It took him 10 years. In all, he has devoted 25 years, his entire career, to the lives of these three people. The book, “Alles voor Vincent” (“All for Vincent”), was published in 2019. Because it’s still available only in Dutch, it is just beginning to percolate into the world of art scholarship. “It’s massively important,” says Steven Naifeh, co-author of the best-selling 2011 biography “Van Gogh: The Life” and author of the forthcoming “Van Gogh and the Artists He Loved.” “It shows that without Jo there would have been no van Gogh.”

Art historians say Luijten’s biography is a major step in what will be an ongoing reappraisal — not only of the source of van Gogh’s fame but also of the modern notion of what an artist is. For that, too, is something Jo helped to invent.

Jo was at a loss over what to do with herself after Theo died. When a friend from the genteel Dutch village of Bussum suggested she come there and open a boardinghouse, it seemed soothing. She would be back in her home country yet at a comfortable distance from her family, which suited her, because she valued her independence. Bussum, for all its leafy sedateness, had a lively cultural scene. And having income from guests would be important — she would be able to provide for herself and her child.

Before leaving Paris, she corresponded with the artist Émile Bernard, one of the few painters with whom Vincent had had a relationship that was both close and free of discord, to see if he might be able to arrange an exhibition in Paris of her late brother-in-law’s paintings. Bernard urged her to leave Vincent’s canvases in Paris, reasoning that the French capital was a better base from which to sell them. There was sense in this. While Vincent had not generated enough of a following to warrant a one-man show, he had had paintings exhibited in a few group shows just before his death. Perhaps, over time, Bernard would be able to sell his work.

Had that happened, Vincent might have developed some renown. He might have become, say, an Émile Bernard. But Jo’s instincts told her to keep the paintings with her. She declined his offer. This was remarkable in itself, because time and again her diary entries show her to be riddled with insecurities and uncertainty about how to proceed in life: “I’m very bad — ugly as I am, I’m still often vain”; “My outlook on life is utterly and completely wrong at present”; “Life is so difficult and so full of sadness around me and I have so little courage!”

Over the next weeks, dressed in mourning, she settled into her new home. She unpacked linens and silverware, met her neighbors and prepared the house for guests, all the while caring for little Vincent. She seems to have spent the greatest amount of her settling-in time — months, in fact — deciding precisely where to hang her brother-in-law’s paintings. Eventually, virtually every inch of wall space was covered with them. “The Potato Eaters,” the large, mostly brown study of peasants at a humble meal that scholars consider Vincent’s first masterpiece, was hung above the fireplace. She festooned her bedroom with three canvases depicting orchards in vibrant bloom. One of her guests later remarked that “the whole house was filled with Vincents.”

Once all was more or less the way she wanted it, she picked up one of the lined notebooks and returned to the diary she began in her teens. She set it aside the moment she started her life with Theo; her last entry, from almost exactly three years before, began, “On Thursday morning I go to Paris!” During the whole mad period that followed, she was too busy to keep a journal, too swept up in another life. Now she was back. “It’s all nothing but a dream!” she wrote from her guesthouse. “What lies behind me — my short, blissful marital happiness — that, too, has been a dream! For a year and a half I was the happiest woman on Earth.”

Then, matter-of-factly, she identified the two responsibilities that Theo had given her. “As well as the child,” she wrote, “he has left me another task — Vincent’s work — getting it seen and appreciated as much as possible.”

Having no training in how to achieve this, she began with what was at hand. In addition to Vincent’s paintings, she had inherited the enormous trove of letters that the brothers had exchanged. In Bussum, in the evenings, with her guests taken care of and the baby asleep, she pored over them. Nearly all, it turned out, were from Vincent — her husband had carefully kept Vincent’s letters, but Vincent hadn’t been so fastidious with the ones his brother had sent him. Details of the artist’s daily life and tribulations — his insomnia, his poverty, his self-doubt — were mixed with accounts of paintings he was working on, techniques he experimented with, what he was reading, descriptions of paintings by other artists he drew inspiration from. He often felt the need to put into words what he was trying to achieve with color: “Town violet, star yellow, sky blue-green; the wheat fields have all the tones: old gold, copper, green gold, red gold, yellow gold, green, red and yellow bronze.” Repeatedly he sought to explain his objective in capturing what he was looking at: “I tried to reconstruct the thing as it may have been by simplifying and accentuating the proud, unchanging nature of the pines and the cedar bushes against the blue.” He described his harrowing mental breakdowns and his fear of future collapses — that “a more violent crisis may destroy my ability to paint forever,” and his notion that, should he experience another episode, he could “go into an asylum or even to the town prison, where there’s usually an isolation cell.”

She did a lot of other reading as well, undertaking what amounted to a self-guided course in art criticism. She read the Belgian journal L’Art Moderne, which advocated the idea that art should serve progressive political causes, and took notes. She read a book of criticism by the Irish novelist George Moore, jotting down a quote from it that seemed pertinent: “The lot of critics is to be remembered by what they failed to understand.” As if to steel herself for her task ahead, she also read a biography of one of her heroes, Mary Ann Evans, the English protofeminist and social critic who wrote novels under the pen name George Eliot. She described Evans in her diary as “that great, courageous, intelligent woman whom I’ve loved and revered almost since childhood” and noted that “remembering her is always an incentive to be better.”

She began to circulate in society. Some of the people she knew in the area were part of a community of artists, poets and intellectuals who had founded an arts journal called The New Guide. As the industrialization of the late 1880s and early 1890s spawned an anarchist movement and rising nationalisms, they were processing the ferment in Western society and sorting through how the arts should respond. Jo’s diary gives the impression of her attending their gatherings and not so much participating in conversations as listening while the intellectuals held forth on what was wrong with the art of the classical tradition, which followed prescribed rules and favored idea over emotion and line over color. Critics like Joseph Alberdingk Thijm, professor of aesthetics and the history of art at Amsterdam’s State Academy of Visual Arts, held that artists had a moral duty to uphold Christian ideals that undergirded society and to enhance the “representation of nature” in a way that “must be firm, clear, purified.”

By the end of her first year on her own — living with Vincent’s paintings and his words, reading deeply, immersing herself from time to time in these gatherings — Jo had experienced a kind of epiphany: Van Gogh’s letters were part and parcel of the art. They were keys to the paintings. The letters brought the art and the tragic, intensely lived life together into a single package. Jo would have appreciated the view of the French Impressionists she had met in Paris that the notion of following rules on how and what to paint had become impossibly inauthentic, that in a world lacking a central authority an artist had to look within for guidance. That was what Monet, Gauguin and the others had done, and the results were to be seen on their canvases. Bringing an artist’s biography into the mix was simply another step in the same direction.

The letters also pointed to the audience Vincent had intended. Vincent, who once sought a career as a minister and lived among peasants to humble himself, had desperately wanted to make art that reached beyond the cognoscenti and directly into the hearts of common people. “No result of my work would be more agreeable to me,” he wrote to Theo, quoting another artist, “than that ordinary working men should hang such prints in their room or workplace.” Vincent’s letters and paintings seemed to reinforce Jo’s own longstanding convictions about social justice. As a girl, influenced by Sunday sermons, she longed for a life of purpose. Just before agreeing to marry Theo, she visited Belgium, and the minister whose family she was staying with took her to see the living conditions of workers at a nearby coal mine. The experience shook her, and helped fuel what became a lifelong dedication to causes ranging from workers’ rights to female suffrage. She counted herself as one of the “ordinary” people Vincent had written of, and she knew that he had considered himself one as well. After consuming her tortured brother-in-law’s words alone in her guesthouse one night during a storm in 1891, with the wind howling outside, she wrote in a letter, “I felt so desolate — that for the first time I understood what he must have felt, in those times when everyone turned away from him.”

She was now ready to act as agent for Vincent van Gogh. One of her first moves was to approach an art critic named Jan Veth, who in addition to being the husband of a friend was at the forefront of the New Guide circle. Veth was outspoken in his rejection of academic art and in promoting individual expression. At first, though, Veth dismissed Vincent’s work outright and belittled Jo’s efforts. He himself later admitted that he was initially “repelled by the raw violence of some van Goghs,” and found these paintings “nearly vulgar.” His reaction, despite his commitment to the new, gives a sense of the shock that Vincent’s canvases engendered at first sight. Another early critic found Vincent’s landscapes “without depth, without atmosphere, without light, the unmixed colors set beside each other without mutually harmonizing,” and complained that the artist was painting out of a desire to be “modern, bizarre, childlike.”

Jo found Veth’s reaction disappointingly conventional. He must also have said something disparaging about a woman seeking to enter the art world, because she complained to her diary after an encounter with him: “We women are for the most part what men want us to be.” But she realized his importance as a critic and believed that his openness to new ideas meant that she could persuade him to appreciate the paintings, telling her diary, “I won’t rest until he likes them.”

She pressed an envelope full of Vincent’s letters on Veth, encouraging him to use them, as she had, as a means to illuminate the paintings. She didn’t try to come across like an art critic but instead poured her heart out to the man, trying to guide him toward the shift in thinking that she felt was needed to perceive a new mode of artistic expression. She explained to Veth that she had begun reading the correspondence between the brothers in order to be closer to her dead husband, but then Vincent stole his way into her. “I read the letters — not only with my head — I was deep into them with my whole soul,” she wrote to Veth. “I read them and reread them until the whole figure of Vincent was clear before me.” She told him that she wished she could “make you feel the influence that Vincent has had on my life. ... I’ve found serenity.”

Her timing was good. The Dutch historian Johan Huizinga later characterized the “change of spirit that began to be felt in art and literature around 1890” as a swirl of ideas that coalesced around two poles: “that of socialism and that of mysticism.” Jo saw that Vincent’s art straddled both. Jan Veth was among those trying to process a shift from Impressionism to something new, an art that applied individualism to social and even spiritual questions. He listened to Jo and came around. He wrote one of the first appreciations of the artist, saying that he now saw “the astonishing clairvoyance of great humility” and characterized Vincent as an artist who “seeks the raw root of things.” In particular, Jo’s effort to bring her brother-in-law’s life to bear on his art seems to have worked with Veth. “Once having grasped his beauty, I can accept the whole man,” the critic wrote.

Something similar happened when Jo approached an influential artist named Richard Roland Holst to ask him to help promote Vincent. She must have pestered him relentlessly, because Roland Holst wrote to a friend, “Mrs. van Gogh is a charming woman, but it irritates me when someone fanatically raves about something they don’t understand.” But he came around, too, and assisted Jo with one of the first solo exhibitions of Vincent’s art, in Amsterdam in December 1892.

Veth and Roland Holst complained at first about Jo’s amateur enthusiasm. Each man found it unprofessional to look at the paintings with the artist’s life story in mind. Such an approach, Roland Holst huffed, “is not of a purely art-critical nature.” It’s not clear from her diary how consciously Jo used her lay status or her position as a woman to her advantage with these men of power, but somehow she got them to drop their guard and simply look and feel along with her. When Jo asked Roland Holst to make a cover illustration for the catalog of Vincent’s first exhibit in Amsterdam, he crafted a lithograph of a wilting sunflower against a black background, with the word “Vincent” beneath and a halo above the sunflower: an aesthetic canonization. Shortly after, the organizers of another exhibition hung a crown of thorns over a portrait of Vincent. Time and again, critics at first resisted the idea of looking at Vincent’s life and work as one, then gave in to it. When they looked at the paintings, they saw not just the art but Vincent, toiling and suffering, cutting off his ear, clawing at the act of creation. They fused art and artist. They saw what Jo van Gogh-Bonger wanted them to see.

Jo worked doggedly to build on her early successes with critics. She did much else in her life, of course. She raised her son. She fell in love with the painter Isaac Israëls, then broke it off when she realized he was not interested in marriage. She eventually remarried: yet another Dutch painter, Johan Cohen Gosschalk. She became a member of the Dutch Social Democratic Workers’ party and a co-founder of an organization devoted to labor and women’s rights. But all these activities were woven around the task of managing her brother-in-law’s post-mortem career. “You see her thinking out loud,” Hans Luijten told me. In the early days, he said, she went about it as modestly as one could imagine: “She identifies an important gallery in Amsterdam and she goes there: a 30-year-old woman, with a little boy at her side and a painting under her arm. She writes to people across Europe.”

Her training as a language teacher — she knew French, German and English — came in especially handy as she expanded her reach, attracting the interest of galleries and museums in Berlin, Paris, Copenhagen. In 1895, when Jo was 33, the Parisian dealer Ambroise Vollard included 20 van Goghs in a show. Vincent’s intensely personal and emotion-filled approach had been ahead of its time, but time was catching up; in Antwerp, a group of young artists who saw him as a trailblazer asked to borrow several van Goghs to exhibit alongside their own work.

Jo learned the tricks of the trade — for example, to hold onto the best works but to include them as “on loan” alongside paintings that were for sale in a given show. “She knew that if you put a few top works on the wall, people will be stimulated to buy the works next to them,” Luijten says. “She did that all over Europe, in more than 100 shows.” A key to her success, says Martin Bailey, an author of several books on the artist, including “Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum,” was in “selling the works in a controlled way, gradually introducing van Gogh to the public.” For an exhibit in Paris in 1908, for instance, she sent 100 works but stipulated that a quarter of them were not for sale. The dealer begged her to reconsider; she held firm. Bucking her tendency to doubt herself, she proceeded methodically and inexorably, like a general conquering territory.

In 1905, she arranged a major exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam’s premier modern-art showcase. She reckoned that it was time for a grand statement. The success she had had in promoting her brother-in-law’s art boosted her self-confidence. As more and more people in the field came to agree with her assessment of Vincent, she shed her youthful hesitancy. Rather than hand over the task of organizing the show, she insisted on doing everything herself. She rented the galleries, printed the posters, assembled names of important people to invite, even bought bow ties for the staff. Her son, Vincent, now 15, wrote out the invitations. The result was, and remains, the largest-ever van Gogh exhibition, with 484 works on display.

Critics came from all over Europe. The hard work of translating the artist’s vision into the vernacular was mostly done by this time. Fourteen years after she was handed her task and had the epiphany to sell the art and artist as a package, everyone in the art world seemed to know Vincent personally, to know his tragic lifelong struggle to find and convey beauty and meaning. The event cemented the artist’s reputation as a major figure of the modern era. Prices for his paintings rose two- to threefold in the months after.

There was one caveat. The work of Vincent’s later period, when he was in an asylum in the South of France and after, which today is probably the most beloved part of his oeuvre, made some people uncomfortable. To some early critics, these paintings seemed clearly the product of mental illness. The unbridled intensity that Vincent brought to a lone mulberry tree, or a stand of cypresses, or a wheat field under a blazing sun, was off-putting. As one critic wrote, in response to the Amsterdam show, Vincent lacked “the distinctive calm that is inherent in the works of the very Great. He will always be a tempest.”

One painting in particular, “The Starry Night,” which many today consider one of Vincent’s most iconic works, was singled out for criticism. The discomfort over its distortions began with Theo, after Vincent sent the painting to him and Jo from Saint-Rémy. Jo may have initially shared her husband’s uneasiness toward it. She didn’t include it in any of the early exhibitions she arranged, and she eventually sold it. Throughout her life she mostly held onto what she believed to be Vincent’s best work. But she got the owner of the painting to lend it for the Amsterdam show, suggesting that she had come to embrace its intensity.

One reviewer — who had a fit over the whole exhibition, calling it a “scandal” that was “more for those interested in psychology than for art lovers” attacked “The Starry Night,” likening the stars in the painting to oliebollen, the fried dough balls that Dutch people eat on New Year’s Eve. That kind of criticism, however, only seemed to bring more attention to the painting, and ultimately to give further validity to the idea of art as a window into the mind and life of the artist. It may also have confirmed for Jo her reappraisal of Vincent’s more stylized work. She bought the painting back the next year. It eventually ended up at the Museum of Modern Art, becoming the first van Gogh in the collection of a New York museum.

When Emilie Gordenker, a Dutch-American art historian, took over as director of the Van Gogh Museum at the beginning of 2020, the staff greeted her with a copy of Hans Luijten’s biography of Jo van Gogh-Bonger. Gordenker’s background was in 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art; since 2008 she had been the director of the Mauritshuis Museum in The Hague, the storied home of many Vermeers and Rembrandts. She knew she had to get up to speed on van Gogh, so she read the book immediately.

Gordenker said she found herself reacting to Jo’s story as a woman. “Though I’m not nearly the trailblazer Jo was, I can relate to some of the struggles,” she says. “For example, when I make a decision, I’m sometimes told what I am. ‘You’re a woman, so you do things differently.’ You want to be evaluated for your ideas, but you’re sometimes pigeonholed. Of course, it was so much worse for her, being told you can’t do this because it’s not for women.”

She says she was struck by Jo’s self-taught approach to marketing an artist. “She had to make it up as she went along,” she says. “She didn’t have any background in this. But she was forthright and direct and at the same time very unsure of herself. That turns out to be a very productive combination of traits.” Gordenker says she believes it was a simple gut feeling that led Jo to her epiphany. “That informed her decision to make one package of the work and the person. Of course, she could only do that because of the letters. She found them to be a unique selling point. She sold the package to the critics, and they bought it.”

Gordenker stresses that Jo’s approach worked because it suited the times. “It was a moment when everything came together. There was a return to romanticism in art and literature. People were open to it. And her achievement informs our image to this day of what an artist should do: be an individual; suffer for art, if need be.” It takes some effort today to realize that people did not always see artists that way. “When I was studying art history, I was told to unthink that notion of the starving artist in the garret,” Gordenker says. “It doesn’t work for the early modern period, when someone like Rembrandt was a master working with apprentices and had many wealthy clients. In a sense Jo helped shape the image that is still with us.”

Jo also set in motion a family legacy of carrying on her work. Gordenker put me in contact with Jo’s great-grandson Vincent Willem van Gogh. At 67, he gives off an air of easy elegance. He spoke fondly of his grandfather Vincent — Jo and Theo’s son. He told me that he and his grandfather both tried to distance themselves from the burden of their ancestor’s legacy (and by extension of Jo’s obsession): his grandfather by becoming an engineer, he by becoming a lawyer (and by deciding to go by his middle name). But eventually each man came around and accepted his role as a custodian of what Jo began.

Jo’s great-grandson says he remembers spending summers at the house in Laren, the town where his grandfather lived. After Jo’s death, the Engineer (as Jo’s son is referred to in the family, to distinguish him from the other Vincents) made it the temporary home of the collection: the 220 original Van Gogh paintings, as well as hundreds of drawings, that Jo, even after a career of selling Vincent’s works, had kept, and that she left to him.

The artist’s namesake told me he spent many childhood holidays at that house. He remembers that there was a “Sunflowers” hanging in the living room (one of five major renderings of the subject that Vincent painted) and a small painting of an almond-blossom branch in a vase at the end of a corridor, and that his grandfather kept his favorite, a view of Arles, on his desk, leaning against a stack of books. But only a fraction of the collection was displayed. “There was a walk-in closet in an upstairs bedroom,” he told me. All the art was there, everything that Jo had not sold, which today would surely be valued in the tens of billions of dollars. “I remember I would help him to get ready for an exhibition at, say, MoMA, or the Orangerie in Paris. He might be looking for flower paintings. We would go through the closet. I’d locate something and say, ‘This, Grandpa?’” The former lawyer, who is now an adviser to the board of the Van Gogh Museum, gave a chuckle at the memory: “You could never do that now.”

But Jo’s son did not plan on keeping the art in his closet forever. In 1959 he entered into negotiations with the Dutch government to create a permanent home for it. All the art that Jo had kept was transferred to the Vincent van Gogh Foundation. The three living descendants of Jo and Theo’s only son sit on the foundation’s board; the fourth board member is an official with the Dutch ministry of culture. The government built the Van Gogh Museum to house the work and assumed the responsibility of making it public. “There’s not a single painting or drawing by Vincent in the family anymore,” Jo’s great-grandson told me with some pride. “Thanks to Jo, and to her son, it’s no longer ours. It’s for everyone.”

Thus the museum itself is another product of Jo van Gogh-Bonger’s efforts to realize Vincent’s ambition of democratizing his art. By numbers alone it has succeeded spectacularly. When the original building was opened, in 1973, it was with an expectation of receiving 60,000 visitors a year. In 2019, before the pandemic, more than 2.1 million people jostled for the chance to spend a few moments before each of the master’s canvases.

In 1916, at age 54, Jo confronted the most formidable challenge in her campaign to bring Vincent to the world. For all the success she had had in Europe, the United States, with its conservative and puritanical society, lagged in appreciating the artist. She left Europe — left her whole world — and moved to New York with a goal of changing that. She spent nearly three years in the United States, living for a time on the Upper West Side and then in Queens, networking, explaining the artist’s vision and, in her spare time, translating Vincent’s letters into English.