Mental Health Case Study: Understanding Depression through a Real-life Example

Imagine feeling an unrelenting heaviness weighing down on your chest. Every breath becomes a struggle as a cloud of sadness engulfs your every thought. Your energy levels plummet, leaving you physically and emotionally drained. This is the reality for millions of people worldwide who suffer from depression, a complex and debilitating mental health condition.

Understanding depression is crucial in order to provide effective support and treatment for those affected. While textbooks and research papers provide valuable insights, sometimes the best way to truly comprehend the depths of this condition is through real-life case studies. These stories bring depression to life, shedding light on its impact on individuals and society as a whole.

In this article, we will delve into the world of mental health case studies, using a real-life example to explore the intricacies of depression. We will examine the symptoms, prevalence, and consequences of this all-encompassing condition. Furthermore, we will discuss the significance of case studies in mental health research, including their ability to provide detailed information about individual experiences and contribute to the development of treatment strategies.

Through an in-depth analysis of a selected case study, we will gain insight into the journey of an individual facing depression. We will explore their background, symptoms, and initial diagnosis. Additionally, we will examine the various treatment options available and assess the effectiveness of the chosen approach.

By delving into this real-life example, we will not only gain a better understanding of depression as a mental health condition, but we will also uncover valuable lessons that can aid in the treatment and support of those who are affected. So, let us embark on this enlightening journey, using the power of case studies to bring understanding and empathy to those who need it most.

Understanding Depression

Depression is a complex and multifaceted mental health condition that affects millions of people worldwide. To comprehend the impact of depression, it is essential to explore its defining characteristics, prevalence, and consequences on individuals and society as a whole.

Defining depression and its symptoms

Depression is more than just feeling sad or experiencing a low mood. It is a serious mental health disorder characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and a loss of interest in activities that were once enjoyable. Individuals with depression often experience a range of symptoms that can significantly impact their daily lives. These symptoms include:

1. Persistent feelings of sadness or emptiness. 2. Fatigue and decreased energy levels. 3. Significant changes in appetite and weight. 4. Difficulty concentrating or making decisions. 5. Insomnia or excessive sleep. 6. feelings of guilt, worthlessness, or hopelessness. 7. Loss of interest or pleasure in activities.

Exploring the prevalence of depression worldwide

Depression knows no boundaries and affects individuals from all walks of life. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 264 million people globally suffer from depression. This makes depression one of the most common mental health conditions worldwide. Additionally, the WHO highlights that depression is more prevalent among females than males.

The impact of depression is not limited to individuals alone. It also has significant social and economic consequences. Depression can lead to impaired productivity, increased healthcare costs, and strain on relationships, contributing to a significant burden on families, communities, and society at large.

The impact of depression on individuals and society

Depression can have a profound and debilitating impact on individuals’ lives, affecting their physical, emotional, and social well-being. The persistent sadness and loss of interest can lead to difficulties in maintaining relationships, pursuing education or careers, and engaging in daily activities. Furthermore, depression increases the risk of developing other mental health conditions, such as anxiety disorders or substance abuse.

On a societal level, depression poses numerous challenges. The economic burden of depression is significant, with costs associated with treatment, reduced productivity, and premature death. Moreover, the social stigma surrounding mental health can impede individuals from seeking help and accessing appropriate support systems.

Understanding the prevalence and consequences of depression is crucial for policymakers, healthcare professionals, and individuals alike. By recognizing the significant impact depression has on individuals and society, appropriate resources and interventions can be developed to mitigate its effects and improve the overall well-being of those affected.

The Significance of Case Studies in Mental Health Research

Case studies play a vital role in mental health research, providing valuable insights into individual experiences and contributing to the development of effective treatment strategies. Let us explore why case studies are considered invaluable in understanding and addressing mental health conditions.

Why case studies are valuable in mental health research

Case studies offer a unique opportunity to examine mental health conditions within the real-life context of individuals. Unlike large-scale studies that focus on statistical data, case studies provide a detailed examination of specific cases, allowing researchers to delve into the complexities of a particular condition or treatment approach. This micro-level analysis helps researchers gain a deeper understanding of the nuances and intricacies involved.

The role of case studies in providing detailed information about individual experiences

Through case studies, researchers can capture rich narratives and delve into the lived experiences of individuals facing mental health challenges. These stories help to humanize the condition and provide valuable insights that go beyond a list of symptoms or diagnostic criteria. By understanding the unique experiences, thoughts, and emotions of individuals, researchers can develop a more comprehensive understanding of mental health conditions and tailor interventions accordingly.

How case studies contribute to the development of treatment strategies

Case studies form a vital foundation for the development of effective treatment strategies. By examining a specific case in detail, researchers can identify patterns, factors influencing treatment outcomes, and areas where intervention may be particularly effective. Moreover, case studies foster an iterative approach to treatment development—an ongoing cycle of using data and experience to refine and improve interventions.

By examining multiple case studies, researchers can identify common themes and trends, leading to the development of evidence-based guidelines and best practices. This allows healthcare professionals to provide more targeted and personalized support to individuals facing mental health conditions.

Furthermore, case studies can shed light on potential limitations or challenges in existing treatment approaches. By thoroughly analyzing different cases, researchers can identify gaps in current treatments and focus on areas that require further exploration and innovation.

In summary, case studies are a vital component of mental health research, offering detailed insights into the lived experiences of individuals with mental health conditions. They provide a rich understanding of the complexities of these conditions and contribute to the development of effective treatment strategies. By leveraging the power of case studies, researchers can move closer to improving the lives of individuals facing mental health challenges.

Examining a Real-life Case Study of Depression

In order to gain a deeper understanding of depression, let us now turn our attention to a real-life case study. By exploring the journey of an individual navigating through depression, we can gain valuable insights into the complexities and challenges associated with this mental health condition.

Introduction to the selected case study

In this case study, we will focus on Jane, a 32-year-old woman who has been struggling with depression for the past two years. Jane’s case offers a compelling narrative that highlights the various aspects of depression, including its onset, symptoms, and the treatment journey.

Background information on the individual facing depression

Before the onset of depression, Jane led a fulfilling and successful life. She had a promising career, a supportive network of friends and family, and engaged in hobbies that brought her joy. However, a series of life stressors, including a demanding job, a breakup, and the loss of a loved one, began to take a toll on her mental well-being.

Jane’s background highlights a common phenomenon – depression can affect individuals from all walks of life, irrespective of their socio-economic status, age, or external circumstances. It serves as a reminder that no one is immune to mental health challenges.

Presentation of symptoms and initial diagnosis

Jane began noticing a shift in her mood, characterized by persistent feelings of sadness and a lack of interest in activities she once enjoyed. She experienced disruptions in her sleep patterns, appetite changes, and a general sense of hopelessness. Recognizing the severity of her symptoms, Jane sought help from a mental health professional who diagnosed her with major depressive disorder.

Jane’s case exemplifies the varied and complex symptoms associated with depression. While individuals may exhibit overlapping symptoms, the intensity and manifestation of those symptoms can vary greatly, underscoring the importance of personalized and tailored treatment approaches.

By examining this real-life case study of depression, we can gain an empathetic understanding of the challenges faced by individuals experiencing this mental health condition. Through Jane’s journey, we will uncover the treatment options available for depression and analyze the effectiveness of the chosen approach. The case study will allow us to explore the nuances of depression and provide valuable insights into the treatment landscape for this prevalent mental health condition.

The Treatment Journey

When it comes to treating depression, there are various options available, ranging from therapy to medication. In this section, we will provide an overview of the treatment options for depression and analyze the treatment plan implemented in the real-life case study.

Overview of the treatment options available for depression

Treatment for depression typically involves a combination of approaches tailored to the individual’s needs. The two primary treatment modalities for depression are psychotherapy (talk therapy) and medication. Psychotherapy aims to help individuals explore their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, while medication can help alleviate symptoms by restoring chemical imbalances in the brain.

Common forms of psychotherapy used in the treatment of depression include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy (IPT), and psychodynamic therapy. These therapeutic approaches focus on addressing negative thought patterns, improving relationship dynamics, and gaining insight into underlying psychological factors contributing to depression.

In cases where medication is utilized, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly prescribed. These medications help rebalance serotonin levels in the brain, which are often disrupted in individuals with depression. Other classes of antidepressant medications, such as serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) or tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), may be considered in specific cases.

Exploring the treatment plan implemented in the case study

In Jane’s case, a comprehensive treatment plan was developed with the intention of addressing her specific needs and symptoms. Recognizing the severity of her depression, Jane’s healthcare team recommended a combination of talk therapy and medication.

Jane began attending weekly sessions of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with a licensed therapist. This form of therapy aimed to help Jane identify and challenge negative thought patterns, develop coping strategies, and cultivate more adaptive behaviors. The therapeutic relationship provided Jane with a safe space to explore and process her emotions, ultimately helping her regain a sense of control over her life.

In conjunction with therapy, Jane’s healthcare provider prescribed an SSRI medication to assist in managing her symptoms. The medication was carefully selected based on Jane’s specific symptoms and medical history, and regular follow-up appointments were scheduled to monitor her response to the medication and adjust the dosage if necessary.

Analyzing the effectiveness of the treatment approach

The effectiveness of treatment for depression varies from person to person, and it often requires a period of trial and adjustment to find the most suitable intervention. In Jane’s case, the combination of cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication proved to be beneficial. Over time, she reported a reduction in her depressive symptoms, an improvement in her overall mood, and increased ability to engage in activities she once enjoyed.

It is important to note that the treatment journey for depression is not always linear, and setbacks and challenges may occur along the way. Each individual responds differently to treatment, and adjustments might be necessary to optimize outcomes. Continuous communication between the individual and their healthcare team is crucial to addressing any concerns, monitoring progress, and adapting the treatment plan as needed.

By analyzing the treatment approach in the real-life case study, we gain insights into the various treatment options available for depression and how they can be tailored to meet individual needs. The combination of psychotherapy and medication offers a holistic approach, addressing both psychological and biological aspects of depression.

The Outcome and Lessons Learned

After undergoing treatment for depression, it is essential to assess the outcome and draw valuable lessons from the case study. In this section, we will discuss the progress made by the individual in the case study, examine the challenges faced during the treatment process, and identify key lessons learned.

Discussing the progress made by the individual in the case study

Throughout the treatment process, Jane experienced significant progress in managing her depression. She reported a reduction in depressive symptoms, improved mood, and a renewed sense of hope and purpose in her life. Jane’s active participation in therapy, combined with the appropriate use of medication, played a crucial role in her progress.

Furthermore, Jane’s support network of family and friends played a significant role in her recovery. Their understanding, empathy, and support provided a solid foundation for her journey towards improved mental well-being. This highlights the importance of social support in the treatment and management of depression.

Examining the challenges faced during the treatment process

Despite the progress made, Jane faced several challenges during her treatment journey. Adhering to the treatment plan consistently proved to be difficult at times, as she encountered setbacks and moments of self-doubt. Additionally, managing the side effects of the medication required careful monitoring and adjustments to find the right balance.

Moreover, the stigma associated with mental health continued to be a challenge for Jane. Overcoming societal misconceptions and seeking help required courage and resilience. The case study underscores the need for increased awareness, education, and advocacy to address the stigma surrounding mental health conditions.

Identifying the key lessons learned from the case study

The case study offers valuable lessons that can inform the treatment and support of individuals with depression:

1. Holistic Approach: The combination of psychotherapy and medication proved to be effective in addressing the psychological and biological aspects of depression. This highlights the need for a holistic and personalized treatment approach.

2. Importance of Support: Having a strong support system can significantly impact an individual’s ability to navigate through depression. Family, friends, and healthcare professionals play a vital role in providing empathy, understanding, and encouragement.

3. Individualized Treatment: Depression manifests differently in each individual, emphasizing the importance of tailoring treatment plans to meet individual needs. Personalized interventions are more likely to lead to positive outcomes.

4. Overcoming Stigma: Addressing the stigma associated with mental health conditions is crucial for individuals to seek timely help and access the support they need. Educating society about mental health is essential to create a more supportive and inclusive environment.

By drawing lessons from this real-life case study, we gain insights that can improve the understanding and treatment of depression. Recognizing the progress made, understanding the challenges faced, and implementing the lessons learned can contribute to more effective interventions and support systems for individuals facing depression.In conclusion, this article has explored the significance of mental health case studies in understanding and addressing depression, focusing on a real-life example. By delving into case studies, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexities of depression and the profound impact it has on individuals and society.

Through our examination of the selected case study, we have learned valuable lessons about the nature of depression and its treatment. We have seen how the combination of psychotherapy and medication can provide a holistic approach, addressing both psychological and biological factors. Furthermore, the importance of social support and the role of a strong network in an individual’s recovery journey cannot be overstated.

Additionally, we have identified challenges faced during the treatment process, such as adherence to the treatment plan and managing medication side effects. These challenges highlight the need for ongoing monitoring, adjustments, and open communication between individuals and their healthcare providers.

The case study has also emphasized the impact of stigma on individuals seeking help for depression. Addressing societal misconceptions and promoting mental health awareness is essential to create a more supportive environment for those affected by depression and other mental health conditions.

Overall, this article reinforces the significance of case studies in advancing our understanding of mental health conditions and developing effective treatment strategies. Through real-life examples, we gain a more comprehensive and empathetic perspective on depression, enabling us to provide better support and care for individuals facing this mental health challenge.

As we conclude, it is crucial to emphasize the importance of continued research and exploration of mental health case studies. The more we learn from individual experiences, the better equipped we become to address the diverse needs of those affected by mental health conditions. By fostering a culture of understanding, support, and advocacy, we can strive towards a future where individuals with depression receive the care and compassion they deserve.

Similar Posts

Exploring the World of Bipolar Bingo: Understanding the Game and Its Connection to Bipolar Disorder

Imagine a world where a game of chance holds the power to bring solace and support to individuals affected by bipolar disorder. A seemingly unlikely connection, but one that exists nonetheless. Welcome to the world of…

Can Anxiety Disorders be Genetic? Exploring the Hereditary Aspects of Anxiety Disorders

Introduction to Genetic Factors in Anxiety Disorders Understanding anxiety disorders Anxiety disorders are a common mental health condition that affect millions of individuals worldwide. People with anxiety disorders experience overwhelming feelings of fear, worry, and unease…

Understanding the Abbreviations and Acronyms for Bipolar Disorder

Living with bipolar disorder can be a challenging journey. The constant rollercoaster of emotions, the highs and lows, can take a toll on a person’s mental and emotional well-being. But what if there was a way…

The Connection Between Ice Cream and Depression: Can Ice Cream Really Help?

Ice cream has long been hailed as a delightful treat, bringing joy to people of all ages. It is often associated with carefree summer days, laughter, and moments of pure bliss. But what if I told…

Understanding the Relationship Between Bipolar Disorder and PTSD

Imagine living with extreme mood swings that can range from feeling on top of the world one day to plunging into the depths of despair the next. Now add the haunting memories of a traumatic event…

The Connection Between Meth and Bipolar: Understanding the Link and Seeking Treatment

It’s a tangled web of interconnectedness – the world of mental health and substance abuse. One doesn’t often think of them as intertwined, but for those battling bipolar disorder, the link becomes all too clear. And…

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Patient Case Presentation

Figure 1. Blue and silver stethoscope (Pixabay, N.D.)

Ms. S.W. is a 48-year-old white female who presented to an outpatient community mental health agency for evaluation of depressive symptoms. Over the past eight weeks she has experienced sad mood every day, which she describes as a feeling of hopelessness and emptiness. She also noticed other changes about herself, including decreased appetite, insomnia, fatigue, and poor ability to concentrate. The things that used to bring Ms. S.W. joy, such as gardening and listening to podcasts, are no longer bringing her the same happiness they used to. She became especially concerned as within the past two weeks she also started experiencing feelings of worthlessness, the perception that she is a burden to others, and fleeting thoughts of death/suicide.

Ms. S.W. acknowledges that she has numerous stressors in her life. She reports that her daughter’s grades have been steadily declining over the past two semesters and she is unsure if her daughter will be attending college anymore. Her relationship with her son is somewhat strained as she and his father are not on good terms and her son feels Ms. S.W. is at fault for this. She feels her career has been unfulfilling and though she’d like to go back to school, this isn’t possible given the family’s tight finances/the patient raising a family on a single income.

Ms. S.W. has experienced symptoms of depression previously, but she does not think the symptoms have ever been as severe as they are currently. She has taken antidepressants in the past and was generally adherent to them, but she believes that therapy was more helpful than the medications. She denies ever having history of manic or hypomanic episodes. She has been unable to connect to a mental health agency in several years due to lack of time and feeling that she could manage the symptoms on her own. She now feels that this is her last option and is looking for ongoing outpatient mental health treatment.

Past Medical History

- Hypertension, diagnosed at age 41

Past Surgical History

- Wisdom teeth extraction, age 22

Pertinent Family History

- Mother with history of Major Depressive Disorder, treated with antidepressants

- Maternal grandmother with history of Major Depressive Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder

- Brother with history of suicide attempt and subsequent inpatient psychiatric hospitalization,

- Brother with history of Alcohol Use Disorder

- Father died from lung cancer (2012)

Pertinent Social History

- Works full-time as an enrollment specialist for Columbus City Schools since 2006

- Has two children, a daughter age 17 and a son age 14

- Divorced in 2015, currently single

- History of some emotional abuse and neglect from mother during childhood, otherwise denies history of trauma, including physical and sexual abuse

- Smoking 1/2 PPD of cigarettes

- Occasional alcohol use (approximately 1-2 glasses of wine 1-2 times weekly; patient had not had any alcohol consumption for the past year until two weeks ago)

Antidepressants: A Research Update and a Case Example

What experiences do people have if they take antidepressants.

Posted December 20, 2018

- Find a therapist to overcome depression or anxiety

This post briefly reviews what researchers have been finding about the effectiveness and also the downsides of antidepressant medications — Zoloft, Prozac, and the like. The post then adds a fascinating case example, a self-description submitted to me by a reader who has experienced both the ups and the downs of antidepressant drugs. First, though, a word about my personal bias : Antidepressant pills definitely do help some people. At the same time, I regard them as vastly over-prescribed for mild to moderate depression and also for anxiety . Other treatment strategies for these situations can be equally or more effective, and without the downsides. In my TEDx talk on lifting depression , for instance, I demonstrate an antidepressant visualization exercise that I have used effectively in my clinical practice for decades. See also the techniques here .

What does the latest research suggest about whether you should take antidepressant medications?

For a particularly comprehensive review of the established medical risks of antidepressants , this article from Harvard Medical School is especially informative. You can find many similar articles with a web search of antidepressant risks.

In addition, a recent comprehensive review article of 522 trials and more than 116,000 patients — a meta-analysis combining the findings of all the available studies — reported on findings regarding 21 antidepressant drugs. This review was described as the most comprehensive analysis of the evidence ever undertaken. The Lancet Psychiatry , which reported the study, also then published a further analysis by the study’s authors. Here are their conclusions:

- Antidepressants can be, on average, an effective treatment for adults with moderate-to-severe major depression in the acute phase of illness.

- Effective as defined in this study means that there was a 50 percent or more reduction of depressive symptoms over an eight-week period. “Effective” did not imply complete remission (removal) of the depression.

- Some patients experienced great benefit from the medication ; others gained little or no benefit. In general, the more severe the depression, the more benefits from the antidepressant.

- The average response to a placebo (a sugar pill disguised as medication) was 35 percent. The average response to antidepressants ranged between 42 percent (reboxetine) and 53 percent (amitriptyline).

- For between 47 and 58 percent of subjects, depending on the specific drug, the medication was not effective. That is, they did not experience at least a 50 percent reduction in their depression symptoms.

Note that the depressed clients who did receive relief from taking an antidepressant medication definitely felt better — and yet not necessarily fully healed. Again, "effective" is defined as a 50 percent improvement in symptoms. This definition raises a number of questions:

- What about the remaining effects of depression, if only 50 percent of the symptoms have been relieved by the medication?

- Are antidepressant drugs appropriate to prescribe for milder depression? Or are non-medication therapy techniques just as or more effective? The research deals with only moderate to severe depression. Yet most prescriptions for antidepressants are given for milder to moderate depressive reactions.

- Earlier studies have concluded that the combination of both drugs and psychotherapy has the highest response rate. Both show about equal effectiveness on their own, except that psychotherapy has longer-lasting positive impacts, because it teaches skills and understandings that have long-term benefits. And what about the European research which has found that after people have taken an antidepressant, they become more likely to have subsequent depressive episodes?

- Because of the addictive potential of anti-anxiety drugs, like Xanax and Librium (xxx), antidepressants with sedating side-effect profiles now are prescribed to keep anxiety at bay. What are the effectiveness rates of antidepressants for treating anxiety?

- What about the negative side effects of antidepressants? The Lancet Psychiatry summary article says nothing about these, the most significant of which is drug dependency. Drug dependency means that once people have taken an antidepressant over a significant time period, their body begins to depend on it. The result is that when they try to discontinue taking the medication, their body has a rebound reaction of depression. That depression does not mean that they needed the antidepressant all along. It just means that the drug has caused their body to no longer produce the chemistry of well-being on its own.

A Medications Case Example: Despair, Delight, Disaster, and More

Many thanks to LC, for sharing her antidepressant experiences.

LC: It all started one late afternoon. I was in my car with my toddler-aged son, driving home through typical late afternoon traffic.

Suddenly I smelled the distinct scent of burning. Ahead of me, just five cars away, a plume of neon orange fire was climbing higher and higher. It was so out of place and so sudden that I didn't feel panicked or scared, I just stared for a few seconds, mouth wide open, my brain calibrating a fire on the highway.

Then I saw the people starting to run. And the panic set in. People all around me were jumping out of their cars and running down the highway, away from the gas truck that was literally on fire in front of us. The truck was still mostly intact, and it dawned on me all at once that a larger explosion might be imminent.

I jumped out of the car, pried open the car-seat straps, and then, flinging my son over my shoulder, ran to get as far away from the gasoline truck as possible. There was a BOOM sound, but I didn't look back. I just kept running and saying, "It's OK. We just need to move away from the fire," both to my son, and to myself.

The sirens started. Police and fire-trucks and ambulances somehow made their way through the maze of stopped cars.

A tragic gas leak had killed the driver of the truck. I texted my husband. I called and apologized profusely to my one-year-old's sitter for being so late.

Three hours later, I was on my way home. I had to run to the grocery store, pick up my 4-year-old from preschool, and make dinner. With three young children, I didn't have time to panic, process, or recover. I had to just keep going.

It was only later that night, after 11:00 p.m., that I felt the effects of that experience. My husband tried to calm me down. I was inconsolable. I wanted to scream or cry or run, but I was paralyzed and terrified.

The next day, I couldn't do anything. My anxiety was telling me that I was in danger. I wasn't, but the panic was still there. I was dreading trying to sleep again.

My sister told me to go immediately to a psychiatrist. I did. The psychiatrist talked to me for about 1 minute and then handed me a Xanax (an anti-anxiety pill) and a cup of water: "You are having a panic attack, and you've been in it for almost 24 hours. We need to get you calmed down."

Having a doctor hand me something I could swallow immediately soothed me. I was able finally to speak enough to tell the psychiatrist that I had seen a terrifying accident, and that I had never really suffered from anxiety or panic attacks before. I begged her to please make the anxiety stop.

The psychiatrist prescribed Xanax for a couple of weeks and then Cipralex, a commonly-used SSRI antidepressant that treats both depression and anxiety, to take long-term. She also said that it was imperative that I find a therapist and explore what was going on in my mind. I guess she assumed the trigger was deeper than just seeing a gasoline truck in flames.

Dr. Heitler: Traumatic events can trigger intense panic either during or at some point after the dangerous event has concluded. Eventually, especially with a chance to talk about what happened, the anxiety calms down. In LC’s case however, the parasympathetic nervous system , whose job it is to calm feelings of fear , was not functioning.

Fortunately, the anti-anxiety pill, Xanax, is fast-acting and effective.

Fortunately also, the psychiatrist had suggested that Lia speak with a talk therapist. Talking about the thoughts that were barraging her would enable Lia to digest her thoughts and feelings, both from the recent trauma and from prior events that had troubled her for some time.

Unfortunately, the psychiatrist did not offer non-pill options to calm the intense anxiety reaction. As the saying goes, to a man with a hammer, the world is a nail.

In this case, the hammer was in fact effective. Xanax brought Lia immediate relief. There are, however, non-pill options that can produce the same immediate calming effect. Both acupoint tapping and a visualization called the spinning technique would probably have done the job equally well. In addition, Lia easily could learn to do these techniques on her own at home should the anxiety return.

LC: The thing is . . . I knew that I needed therapy. It had been a long time coming. An unspoken trauma from the past was finding its way out, visiting me in dreams , and violating random moments in my life. I had been doing my best to silence it, shushing it desperately, hoping that it would just go away. So I started therapy. And I started the antidepressant drugs. And I was able to breathe. For a while.

Therapy opened my mind to myself. I had closed it years before. Re-opening it was as if a door had been kicked down. The halls and rooms of my mind were inviting me to explore, to wander, and to get reacquainted with my inner-world.

The SSRI seemed to be working too. I was more calm. I was more at ease. I wasn't barking at my husband about crumbs on the counter or scrubbing toys with bleach every night. I was laughing a little more, yelling a little less, more balanced.

What was from therapy, and what was from the SSRI? I didn’t care. I was just relieved to be breathing normally.

Dr. Heitler: Multiple studies of the treatment of serious emotional distress conclude that the combination of medication and psychotherapy is more potent than either alone. Lia’s case exemplifies this principle. Pills and talk therapy can potentiate each other, that is, cause each other to be more effective than either treatment alone could be.

At the same time, newer therapy techniques, such as the Body Code and Emotion Code, enable a therapist to radically shorten the time and intensity of talk therapy. Within one session or several, an Emotion Code therapist can pinpoint the earlier problem and immediately release trapped negative emotions so that they cease to have impact. With the underground spring that had been feeding anxious, angry and/or depressed feelings turned off, the feelings of vitality and well-being that we call mental health can emerge.

Marriage therapy also might well have helped Lia. My policy is when anyone who is married seeks therapy with me, I encourage them to bring their spouse. In almost all cases, underlying marital issues have been fanning the flames of negative emotions.

The spouse also can have a significant role in fostering a return to mental health. For instance, an anxious or depressed person may have an impulse to spend his evenings isolating and ruminating, saying troubling thoughts over and over to himself. Rumination exacerbates anxiety and depression. If husband and wife enjoy activities together in the evening, they are likely to be able to replace the rumination with pleasant interactions.

LC: I don't regret starting the antidepressant, the Cipralex. I truly feel like that drug saved my mind. It also probably held my marriage together for several more years. But by a year later, I knew that something was off. I knew that it was the medication.

Dr. Heitler: An antidepressant, especially in combination with good talk therapy, can work miracles in enabling people to get back to functioning in a normal emotional zone. The difficulties tend to come with the duration of use.

By prescribing an antidepressant medication and then keeping her on it for more than an initial several months, LC’s psychiatrist had inadvertently invited increasingly negative side effects. The negative side effects which had begun while Lia was taking the pills became even worse when she tried to get off the pills.

LC: At about a year, I started feeling fuzzy, numb, and detached. I would have several-minute episodes of not knowing what I was doing or how I got there. Then the confusion would dissipate, and I would be left thinking that I was just imagining it. But it would happen again. Fleeting, but tangible. Almost leaving a taste in my mouth.

I shared this with my husband, but he was worried about the anxiety returning if I messed with my medication. I waited.

Dr. Heitler: LC’s husband’s concerns had some genuine validity. The difficulty is that after a year of taking antidepressants, anyone who attempts to stop taking them must end their use very slowly. Otherwise, removal of the drugs can precipitate serious depression and/or anxiety.

It’s not that these emotions had been lurking there all along. Rather, antidepressants create drug dependency. The body forgets how to produce the chemicals that sustain well-being when they are being provided artificially by pills.

LC: The side effects worsened. I had no sex drive. I stopped feeling motivated to hang out with friends. I stopped caring about how I looked or what I was wearing. I was sinking. I had been saved from anxiety, and was now slipping into depression.

I made a unilateral decision to go off my meds. It wasn't a wise one. Looking back, I see that it was very much a desperate stand against the many factors in my life that I wasn't in control of — my devastation over my marriage that was quietly but quickly ending, my loss of focus on my passions and hobbies, my overweight and exhausted body, too strict in my religious life . . . the list goes on.

To simply argue that the SSRIs were ruining my life would be short-sighted and most likely wrong. I was ruining my life. But I was absolutely clear that the drug I was putting into my body every day was dragging me down and making it much harder to move forward. I felt very much alone — and for the first time in a while, very clear in my mission.

Dr. Heitler: In addition to creating drug dependency when used for more than several months at a stretch, antidepressants can produce a number of further negative side effects. Weight gain, loss of sexual feelings, emotional numbness, and "brain zapping" are among the most common. LC experienced these, and more.

LC: Going off SSRIs cold-turkey is nothing short of a ride through hell. The physical and emotional effects of suddenly depriving your brain of serotonin is horrific.

I was tormented by anxiety. I experienced electric pulses starting in my head and traveling down my entire body. I found myself in tears over everything. I had so much guilt over the decision. But I couldn't put that pill back in my mouth.

I pushed. It was raw without the drug. My husband and I separated. I said goodbye to God on a park bench and said hello to myself. I sabotaged a friendship — not something I'm proud of. I lost 35 pounds. I started singing out loud. I started running.

I told the psychiatrist what I had done. Even though so many things were better, I was on the verge of another breakdown, and I didn't know what to do.

The psychiatrist prescribed a different drug, this time an SNRI (two chemicals for the brain's "happy" place instead of one). She explained that since I was in the middle of a divorce — a major life-crisis for anyone — it probably wasn't the best time to go off psychiatric drugs.

That night I sat with the new pill in my hand. It took a serious pep talk to swallow it, but I did. I felt like I needed all the help I could get. I had three young children depending on me to keep it together, and I couldn't afford to let emotions destroy me. I had delved extensively into my past and had finally put to rest the lurking earlier trauma. I told myself I would take the drug, and when life settled down, I would get off.

Fast-forward a year and a half. A very similar cycle ensued. At first the SNRI filled me with renewed calm. It was like a rosy tint on life was just a pill away. And then . . . the fog set in. Again, about a year in, I felt that familiar detachment. I stopped caring about the little things. I started to feel like I was being numbed. Like I was underwater. Watching the world from below, too slow to stay actively involved in my own life. My sex drive started dying, and with it, my drive for life deteriorated.

With this new and more powerful drug, I again started feeling physical side effects. If I took the pill a few hours later than usual, I would get extremely nauseous. But if I took it in the morning, I would also get nausea and throw up. On the drug, I was more prone to migraines , I fainted several times that year, and I started gaining weight quite rapidly — despite my strictly healthy lifestyle.

This time around, I was determined to get off the drug safely. I checked in with a doctor. I started by taking off just one-quarter of the dose and did so every four weeks, allowing my brain to adapt each time.

Nonetheless, again it was hard, even painful. Each time I weaned down a dose, I had a week of horrible brain zaps. Even worse, I was much more reactive and impatient with my children. The weaning process took four months.

At the same time, I truly feel like this time around I experienced a beautiful and inspiring rebirth of myself. My senses feel heightened. My experiences are fully my own again.

Dr. Heitler: Paradoxically, ending her use of antidepressants turned out for LC to be the ultimate cure. With the pills no longer compromising her body’s chemistry, LC’s natural vitality eventually returned. So did her sexual feelings, ability to lose weight, eventual loss of the brain zapping, and a return of her former good-humored self.

LC’s conclusions: I'm still forming an objective opinion on the use of SSRIs. The power of these drugs, for better and for worse, is something that shouldn't be taken lightly. Off them now though, for me, heading away from antidepressants is heading in the right direction.

Dr. Heitler’s conclusions: Again, as I said at the outset, for a severe or suicidal depressive episode, antidepressant medications can relieve the intensity of dark thoughts and desperate feelings.

At the same time, Lia’s case illustrates well that antidepressants may:

- Have limited or no effectiveness for almost half of users

- Help somewhat, while many aspects of the depression remain

- Produce problematic side effects, like weight gain, decreased sexual feelings, brain zapping, nausea, clouded thinking, and numbing of feelings of joy as well as of negative emotions

- Create drug dependence when used for longer than a few months, and therefore difficult withdrawal symptoms, including withdrawal-induced depression

- Be prescribed for usages for which they are not intended (i.e., mild depressive reactions and anxiety) and for which non-drug options may be equally effective

- Be prescribed at length, for years rather than months, increasing the difficulties of eventual withdrawal

Susan Heitler, Ph.D ., is the author of many books, including From Conflict to Resolution and The Power of Two . She is a graduate of Harvard University and New York University.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Case Study Research Method in Psychology

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Case studies are in-depth investigations of a person, group, event, or community. Typically, data is gathered from various sources using several methods (e.g., observations & interviews).

The case study research method originated in clinical medicine (the case history, i.e., the patient’s personal history). In psychology, case studies are often confined to the study of a particular individual.

The information is mainly biographical and relates to events in the individual’s past (i.e., retrospective), as well as to significant events that are currently occurring in his or her everyday life.

The case study is not a research method, but researchers select methods of data collection and analysis that will generate material suitable for case studies.

Freud (1909a, 1909b) conducted very detailed investigations into the private lives of his patients in an attempt to both understand and help them overcome their illnesses.

This makes it clear that the case study is a method that should only be used by a psychologist, therapist, or psychiatrist, i.e., someone with a professional qualification.

There is an ethical issue of competence. Only someone qualified to diagnose and treat a person can conduct a formal case study relating to atypical (i.e., abnormal) behavior or atypical development.

Famous Case Studies

- Anna O – One of the most famous case studies, documenting psychoanalyst Josef Breuer’s treatment of “Anna O” (real name Bertha Pappenheim) for hysteria in the late 1800s using early psychoanalytic theory.

- Little Hans – A child psychoanalysis case study published by Sigmund Freud in 1909 analyzing his five-year-old patient Herbert Graf’s house phobia as related to the Oedipus complex.

- Bruce/Brenda – Gender identity case of the boy (Bruce) whose botched circumcision led psychologist John Money to advise gender reassignment and raise him as a girl (Brenda) in the 1960s.

- Genie Wiley – Linguistics/psychological development case of the victim of extreme isolation abuse who was studied in 1970s California for effects of early language deprivation on acquiring speech later in life.

- Phineas Gage – One of the most famous neuropsychology case studies analyzes personality changes in railroad worker Phineas Gage after an 1848 brain injury involving a tamping iron piercing his skull.

Clinical Case Studies

- Studying the effectiveness of psychotherapy approaches with an individual patient

- Assessing and treating mental illnesses like depression, anxiety disorders, PTSD

- Neuropsychological cases investigating brain injuries or disorders

Child Psychology Case Studies

- Studying psychological development from birth through adolescence

- Cases of learning disabilities, autism spectrum disorders, ADHD

- Effects of trauma, abuse, deprivation on development

Types of Case Studies

- Explanatory case studies : Used to explore causation in order to find underlying principles. Helpful for doing qualitative analysis to explain presumed causal links.

- Exploratory case studies : Used to explore situations where an intervention being evaluated has no clear set of outcomes. It helps define questions and hypotheses for future research.

- Descriptive case studies : Describe an intervention or phenomenon and the real-life context in which it occurred. It is helpful for illustrating certain topics within an evaluation.

- Multiple-case studies : Used to explore differences between cases and replicate findings across cases. Helpful for comparing and contrasting specific cases.

- Intrinsic : Used to gain a better understanding of a particular case. Helpful for capturing the complexity of a single case.

- Collective : Used to explore a general phenomenon using multiple case studies. Helpful for jointly studying a group of cases in order to inquire into the phenomenon.

Where Do You Find Data for a Case Study?

There are several places to find data for a case study. The key is to gather data from multiple sources to get a complete picture of the case and corroborate facts or findings through triangulation of evidence. Most of this information is likely qualitative (i.e., verbal description rather than measurement), but the psychologist might also collect numerical data.

1. Primary sources

- Interviews – Interviewing key people related to the case to get their perspectives and insights. The interview is an extremely effective procedure for obtaining information about an individual, and it may be used to collect comments from the person’s friends, parents, employer, workmates, and others who have a good knowledge of the person, as well as to obtain facts from the person him or herself.

- Observations – Observing behaviors, interactions, processes, etc., related to the case as they unfold in real-time.

- Documents & Records – Reviewing private documents, diaries, public records, correspondence, meeting minutes, etc., relevant to the case.

2. Secondary sources

- News/Media – News coverage of events related to the case study.

- Academic articles – Journal articles, dissertations etc. that discuss the case.

- Government reports – Official data and records related to the case context.

- Books/films – Books, documentaries or films discussing the case.

3. Archival records

Searching historical archives, museum collections and databases to find relevant documents, visual/audio records related to the case history and context.

Public archives like newspapers, organizational records, photographic collections could all include potentially relevant pieces of information to shed light on attitudes, cultural perspectives, common practices and historical contexts related to psychology.

4. Organizational records

Organizational records offer the advantage of often having large datasets collected over time that can reveal or confirm psychological insights.

Of course, privacy and ethical concerns regarding confidential data must be navigated carefully.

However, with proper protocols, organizational records can provide invaluable context and empirical depth to qualitative case studies exploring the intersection of psychology and organizations.

- Organizational/industrial psychology research : Organizational records like employee surveys, turnover/retention data, policies, incident reports etc. may provide insight into topics like job satisfaction, workplace culture and dynamics, leadership issues, employee behaviors etc.

- Clinical psychology : Therapists/hospitals may grant access to anonymized medical records to study aspects like assessments, diagnoses, treatment plans etc. This could shed light on clinical practices.

- School psychology : Studies could utilize anonymized student records like test scores, grades, disciplinary issues, and counseling referrals to study child development, learning barriers, effectiveness of support programs, and more.

How do I Write a Case Study in Psychology?

Follow specified case study guidelines provided by a journal or your psychology tutor. General components of clinical case studies include: background, symptoms, assessments, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Interpreting the information means the researcher decides what to include or leave out. A good case study should always clarify which information is the factual description and which is an inference or the researcher’s opinion.

1. Introduction

- Provide background on the case context and why it is of interest, presenting background information like demographics, relevant history, and presenting problem.

- Compare briefly to similar published cases if applicable. Clearly state the focus/importance of the case.

2. Case Presentation

- Describe the presenting problem in detail, including symptoms, duration,and impact on daily life.

- Include client demographics like age and gender, information about social relationships, and mental health history.

- Describe all physical, emotional, and/or sensory symptoms reported by the client.

- Use patient quotes to describe the initial complaint verbatim. Follow with full-sentence summaries of relevant history details gathered, including key components that led to a working diagnosis.

- Summarize clinical exam results, namely orthopedic/neurological tests, imaging, lab tests, etc. Note actual results rather than subjective conclusions. Provide images if clearly reproducible/anonymized.

- Clearly state the working diagnosis or clinical impression before transitioning to management.

3. Management and Outcome

- Indicate the total duration of care and number of treatments given over what timeframe. Use specific names/descriptions for any therapies/interventions applied.

- Present the results of the intervention,including any quantitative or qualitative data collected.

- For outcomes, utilize visual analog scales for pain, medication usage logs, etc., if possible. Include patient self-reports of improvement/worsening of symptoms. Note the reason for discharge/end of care.

4. Discussion

- Analyze the case, exploring contributing factors, limitations of the study, and connections to existing research.

- Analyze the effectiveness of the intervention,considering factors like participant adherence, limitations of the study, and potential alternative explanations for the results.

- Identify any questions raised in the case analysis and relate insights to established theories and current research if applicable. Avoid definitive claims about physiological explanations.

- Offer clinical implications, and suggest future research directions.

5. Additional Items

- Thank specific assistants for writing support only. No patient acknowledgments.

- References should directly support any key claims or quotes included.

- Use tables/figures/images only if substantially informative. Include permissions and legends/explanatory notes.

- Provides detailed (rich qualitative) information.

- Provides insight for further research.

- Permitting investigation of otherwise impractical (or unethical) situations.

Case studies allow a researcher to investigate a topic in far more detail than might be possible if they were trying to deal with a large number of research participants (nomothetic approach) with the aim of ‘averaging’.

Because of their in-depth, multi-sided approach, case studies often shed light on aspects of human thinking and behavior that would be unethical or impractical to study in other ways.

Research that only looks into the measurable aspects of human behavior is not likely to give us insights into the subjective dimension of experience, which is important to psychoanalytic and humanistic psychologists.

Case studies are often used in exploratory research. They can help us generate new ideas (that might be tested by other methods). They are an important way of illustrating theories and can help show how different aspects of a person’s life are related to each other.

The method is, therefore, important for psychologists who adopt a holistic point of view (i.e., humanistic psychologists ).

Limitations

- Lacking scientific rigor and providing little basis for generalization of results to the wider population.

- Researchers’ own subjective feelings may influence the case study (researcher bias).

- Difficult to replicate.

- Time-consuming and expensive.

- The volume of data, together with the time restrictions in place, impacted the depth of analysis that was possible within the available resources.

Because a case study deals with only one person/event/group, we can never be sure if the case study investigated is representative of the wider body of “similar” instances. This means the conclusions drawn from a particular case may not be transferable to other settings.

Because case studies are based on the analysis of qualitative (i.e., descriptive) data , a lot depends on the psychologist’s interpretation of the information she has acquired.

This means that there is a lot of scope for Anna O , and it could be that the subjective opinions of the psychologist intrude in the assessment of what the data means.

For example, Freud has been criticized for producing case studies in which the information was sometimes distorted to fit particular behavioral theories (e.g., Little Hans ).

This is also true of Money’s interpretation of the Bruce/Brenda case study (Diamond, 1997) when he ignored evidence that went against his theory.

Breuer, J., & Freud, S. (1895). Studies on hysteria . Standard Edition 2: London.

Curtiss, S. (1981). Genie: The case of a modern wild child .

Diamond, M., & Sigmundson, K. (1997). Sex Reassignment at Birth: Long-term Review and Clinical Implications. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine , 151(3), 298-304

Freud, S. (1909a). Analysis of a phobia of a five year old boy. In The Pelican Freud Library (1977), Vol 8, Case Histories 1, pages 169-306

Freud, S. (1909b). Bemerkungen über einen Fall von Zwangsneurose (Der “Rattenmann”). Jb. psychoanal. psychopathol. Forsch ., I, p. 357-421; GW, VII, p. 379-463; Notes upon a case of obsessional neurosis, SE , 10: 151-318.

Harlow J. M. (1848). Passage of an iron rod through the head. Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, 39 , 389–393.

Harlow, J. M. (1868). Recovery from the Passage of an Iron Bar through the Head . Publications of the Massachusetts Medical Society. 2 (3), 327-347.

Money, J., & Ehrhardt, A. A. (1972). Man & Woman, Boy & Girl : The Differentiation and Dimorphism of Gender Identity from Conception to Maturity. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Money, J., & Tucker, P. (1975). Sexual signatures: On being a man or a woman.

Further Information

- Case Study Approach

- Case Study Method

- Enhancing the Quality of Case Studies in Health Services Research

- “We do things together” A case study of “couplehood” in dementia

- Using mixed methods for evaluating an integrative approach to cancer care: a case study

Related Articles

Research Methodology

Qualitative Data Coding

What Is a Focus Group?

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Validity In Research?

Research Methodology , Statistics

What Is Face Validity In Research? Importance & How To Measure

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 30 May 2024

ProMENDA: an updated resource for proteomic and metabolomic characterization in depression

- Juncai Pu 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Yue Yu 3 na1 ,

- Yiyun Liu 2 ,

- Dongfang Wang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7517-3972 2 ,

- Siwen Gui 2 ,

- Xiaogang Zhong 2 ,

- Weiyi Chen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2520-1082 1 , 2 ,

- Xiaopeng Chen 1 , 2 ,

- Yue Chen 1 , 2 ,

- Xiang Chen 1 , 2 ,

- Renjie Qiao 1 , 2 ,

- Yanyi Jiang 1 , 2 ,

- Hanping Zhang 1 , 2 ,

- Li Fan 1 , 2 ,

- Yi Ren 1 , 2 ,

- Xiangyu Chen 1 , 2 ,

- Haiyang Wang 2 &

- Peng Xie ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0081-6048 1 , 2 , 4 , 5

Translational Psychiatry volume 14 , Article number: 229 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

- Molecular neuroscience

Depression is a prevalent mental disorder with a complex biological mechanism. Following the rapid development of systems biology technology, a growing number of studies have applied proteomics and metabolomics to explore the molecular profiles of depression. However, a standardized resource facilitating the identification and annotation of the available knowledge from these scattered studies associated with depression is currently lacking. This study presents ProMENDA, an upgraded resource that provides a platform for manual annotation of candidate proteins and metabolites linked to depression. Following the establishment of the protein dataset and the update of the metabolite dataset, the ProMENDA database was developed as a major extension of its initial release. A multi-faceted annotation scheme was employed to provide comprehensive knowledge of the molecules and studies. A new web interface was also developed to improve the user experience. The ProMENDA database now contains 43,366 molecular entries, comprising 20,847 protein entries and 22,519 metabolite entries, which were manually curated from 1370 human, rat, mouse, and non-human primate studies. This represents a significant increase (more than 7-fold) in molecular entries compared to the initial release. To demonstrate the usage of ProMENDA, a case study identifying consistently reported proteins and metabolites in the brains of animal models of depression was presented. Overall, ProMENDA is a comprehensive resource that offers a panoramic view of proteomic and metabolomic knowledge in depression. ProMENDA is freely available at https://menda.cqmu.edu.cn .

Similar content being viewed by others

Analysis of gene expression in the postmortem brain of neurotypical Black Americans reveals contributions of genetic ancestry

Integrating human endogenous retroviruses into transcriptome-wide association studies highlights novel risk factors for major psychiatric conditions

The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence

Introduction.

Depression is a prevalent mental disorder characterized by low mood and loss of pleasure, with a lifetime prevalence of 11.1%–14.6% [ 1 , 2 ]. The condition leads to severe functional impairment and was reported as one of the top three leading causes of burden in 2019 [ 3 ]. Unlike other somatic diseases, the clinical diagnosis of depression relies entirely on the clinical symptoms of patients, while reliable biomarkers are still lacking [ 4 , 5 ]. Moreover, the clinical efficacy of antidepressants is limited, with more than one-third of patients demonstrating inadequate treatment responses [ 6 ]. Furthermore, the long-term use of antidepressants may lead to various side effects and treatment discontinuation [ 7 ]. Therefore, the screening of biomarkers and new drug targets is expected to improve the diagnosis and treatment of depression [ 8 ]. Despite substantial research efforts, the precise mechanism underlying the onset of depression remains incompletely defined, and a systematic molecular profile of depression is still lacking.

The rapid development of systems biology technology has led to the emergence of multi-omics approaches as powerful methods enabling the determination of molecular profiles of diseases with complex biological mechanisms [ 9 , 10 ]. In the field of depression, omics methods, such as metabolomics and proteomics, have been widely applied to study the brain and peripheral samples of patients and animal models. The results have identified numerous differential metabolites and proteins between depressed and normal states [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. Recent developments and applications in omics research have highlighted the need for comprehensive resources that integrate the available knowledge from scattered studies and provide a panoramic view of molecular characterization in depression [ 14 ]. Therefore, MENDA was developed to present the manually curated metabolic characterization (with 5,600 metabolite entries) in the context of depression [ 15 ]. Since its first release in 2019, multiple integrated studies have employed MENDA to generate meaningful biological insights [ 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]. However, the number of metabolomics studies has doubled since the first release, and the core dataset warrants an update. Moreover, molecular data at the protein level is required to capture the multi-level biochemical dysregulation of depression, which could provide information on specific enzymes in the metabolic pathways and networks [ 20 , 21 ]. A growing body of proteomics studies have identified alterations in protein abundances in depression [ 22 , 23 , 24 ], providing an important resource of proteomic information. To date, a platform facilitating the systematic curation of proteomic changes in depression is still lacking. Adding protein information to the MENDA will contribute to a deeper understanding of molecular alterations in depression.

This study aimed to create a standardized resource for all available knowledge in the growing area of proteomic and metabolomic research in depression. Therefore, this study presents Protein and Metabolite Network of Depression Database (ProMENDA), an upgraded resource that provides a platform for the manual annotation of candidate proteins and metabolites linked to depression. The data set now contains 43,366 molecular entries from 1370 studies that investigated differential proteins and metabolites in both patients and animal models of depression. This update represents a significant increase (more than 7-fold) in molecular entries compared to the initial release of MENDA. Additionally, the web interface was redesigned to enhance the ease of use. The design and implementation of these updates and changes are described below. To demonstrate the usage of ProMENDA, a case study analyzing the molecular changes in the brains of animal models is presented. ProMENDA is expected to contribute to the investigation of the molecular profile of depression.

Materials and methods

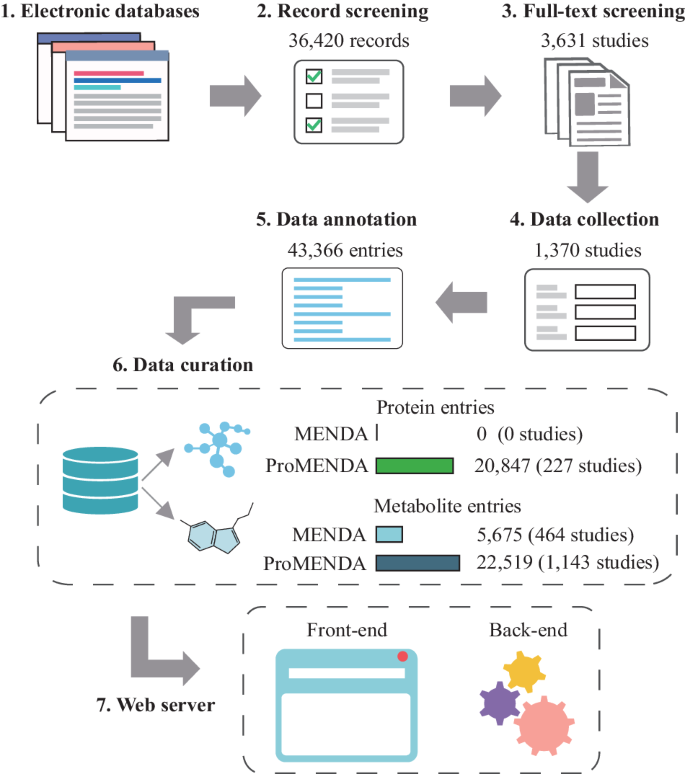

Overview of promenda framework.

The schematic overview of ProMENDA is illustrated in Fig. 1 . In brief, information on study design and candidate molecules from proteomics and metabolomics studies of depression was manually collected using standardized data extraction tables. These tables were then integrated into annotated datasets based on a multi-faceted annotation scheme. In addition, a brand-new web interface was developed in this update to enhance user experience.

The flowchart of the construction process for the ProMENDA.

Creation of the proteomic dataset

Data from proteomic studies of depression were incorporated to expand the scope of MENDA. Relevant proteomic studies were searched from PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and PsychInfo (Table S1 ), resulting in a cumulative total of 13,742 literature records retrieved as of May 18, 2023 (Table S2 ). Studies that investigated proteomic changes associated with depression and its treatment in both human and animal models were screened based on titles and abstracts, yielding 436 potential studies. After checking the full text of these studies, 227 studies were finally included. The exclusion reasons are summarized in Table S3 .

Subsequently, a proteomic dataset was created by manually selecting the study information and differentially expressed proteins from the full texts and supplementary materials of these studies using a standardized data abstraction spreadsheet (Table S4 ). To present experimental information on each protein, the proteomic data were annotated based on a multi-faceted annotation scheme as described in MENDA [ 15 ], with minor modifications. The annotation scheme involved manual annotation of information of interest at both the study and protein levels, including experimental design, types of organisms, categories of depression, categories of tissues, experimental techniques, citations, etc.

Moreover, protein information was annotated to ensure standardization, including UniProt accessions, UniProt entry names, protein names, and gene symbols based on the UniProtKB database (version 2023_03) [ 25 ]. This step was necessary as proteins were presented in different formats in the original reports, such as protein names, Uniprot accession, or gene symbols. A total of 20,847 protein entries were finally curated.

Update for metabolomic dataset

In this update, MENDA was expanded to include more comprehensive and up-to-date metabolite entries. The initial release of MENDA included 5675 metabolite entries from 464 metabolomics and magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies as of March 20, 2018. To ensure that the ProMENDA remains current, literature databases were re-screened as of May 18, 2023, resulting in a cumulative total of 22,678 records. After screening the full text of 3195 studies, a total of 1143 eligible studies were included in ProMENDA. The reasons for the exclusion of the ineligible studies are summarized in Table S3 . Using a similar data extraction and annotation process to the proteomic dataset, a total of 22,519 differential metabolite entries were curated in this update. The expansion of the metabolite dataset will provide researchers with a more comprehensive overview of metabolic changes associated with depression.

Web interface implementation

The front end of the ProMENDA website has been implemented using HTML, JavaScript, and CSS. The web interface was designed using Bootstrap ( https://getbootstrap.com/ ) and jQuery ( https://jquery.com/ ) libraries, and the interactive tables were constructed using the DataTables library ( https://datatables.net/ ). In addition, the website is hosted on an Apache server ( https://httpd.apache.org ).

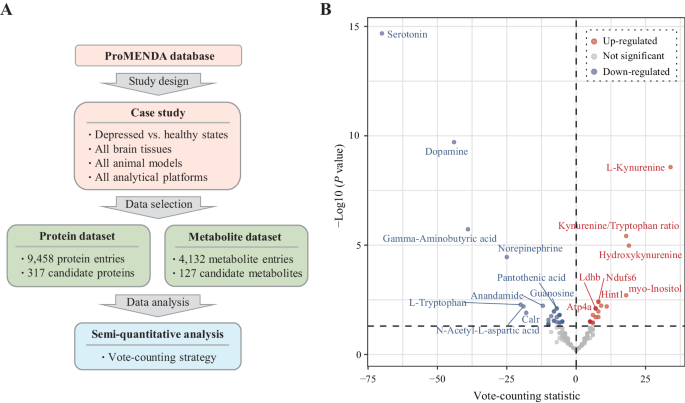

Case study for applications of ProMENDA

In addition to data browsing, users can download data from ProMENDA to conduct data mining studies. To illustrate the potential applications of ProMENDA, a case study involving an integrated analysis was conducted based on protein and metabolite entries in the brains of animal models of depression. Metabolite and protein entries were selected based on the following criteria: (1) differential molecules between depressed vs. healthy states; (2) all types of animal models; (3) all brain tissues; and (4) all analytical platforms. Semi-quantitative analyses were performed based on selected data. Considering the possibility of inconsistencies in the up- and down-regulation of certain molecules (with unique gene symbols or metabolite names) across different studies, a vote-counting method was utilized for semi-quantitative analysis. This approach effectively identifies the molecules exhibiting consistent up- or down-regulation under specific conditions, indicating their high reproducibility and potential as biomarkers [ 26 ]. Furthermore, the binom.test function in R (version 4.3.0, https://www.rproject.org/ ) was used based on the downloaded data of interest to identify consistently differentially expressed molecules [ 27 ]. Candidate molecules with one-tailed P < 0.05 across different studies were considered as consistently altered. ImageGP was used to create plots [ 28 ].

Data summary

The initial release of MENDA comprised 5675 metabolite entries. In ProMENDA, significant efforts have been made to expand the molecular entries. A cumulative total of 36,420 records were screened from electronic databases, and after checking the full texts of 3631 studies, 1370 studies that investigated the levels of proteins and metabolites in depression and its treatment were included. A standardized data extraction and annotation process was adopted, and 43,366 molecular entries were curated, including 20,847 protein entries (Supplementary Data 1 ) and 22,519 metabolite entries (Supplementary Data 2 ). This has resulted in a significant increase (more than 7-fold) in molecular entries compared to the previous version of MENDA (Fig. 1 ). Moreover, our laboratory provided 3173 metabolites entries and 3927 protein entries in ProMENDA, accounting for 16.4% of all molecular entries.

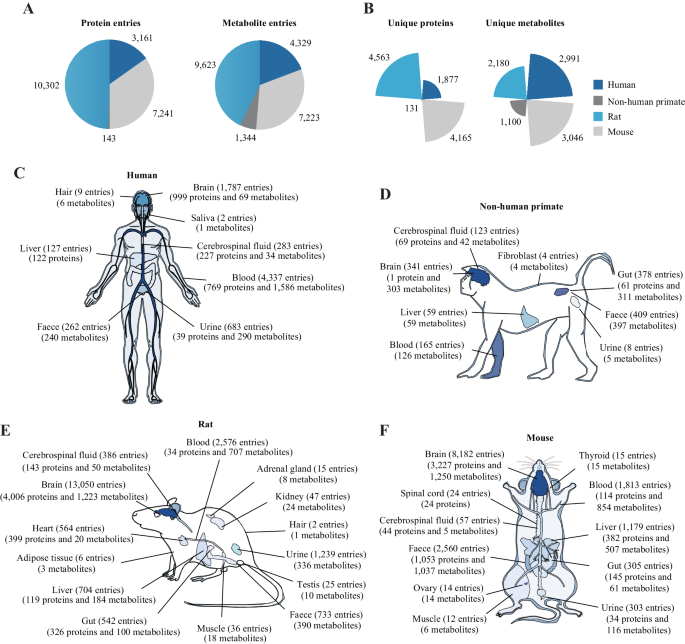

The number of studies that explored molecular alterations in each organism and each tissue is shown in Fig. S1 . In ProMENDA, 7490 molecular entries were curated from human tissues, 1487 from non-human primate tissues, 19,925 from rat tissues, and 14,464 from mice (Fig. 2A ). The numbers of unique proteins and metabolites in humans, non-human primates, rats, and mice are shown in Fig. 2B . Specifically, in humans, 3161 protein entries (from 1877 unique proteins) and 4329 metabolite entries (from 2991 unique metabolites) were curated from 8 types of tissues (Fig. 2C ). In non-human primates, 143 protein entries (from 131 unique proteins) and 1344 metabolite entries (from 1100 unique metabolites) were curated from 8 types of tissues (Fig. 2D ). In rats, 10,302 protein entries (from 4563 unique proteins) and 9623 metabolite entries (from 2180 unique metabolites) were collected from 14 types of tissues (Fig. 2E ). In mice, 7241 protein entries (from 4165 unique proteins) and 7223 metabolite entries (from 3046 unique metabolites) were obtained from 11 types of tissues (Fig. 2F ). The most frequently reported proteins and metabolites in each organism are displayed in Fig. S2 . Among these molecular entries, 72.7% of protein entries and 63.8% of metabolite entries were collected from studies that compared molecular levels between depressed and healthy states; the remaining entries were collected from studies that investigated molecular changes resulting from antidepressant treatments.

A The number of molecular entries from each organism. B The number of unique proteins and metabolites from each organism. C The number of molecular entries and unique molecules in 8 human tissues. D The number of molecular entries and unique molecules in 8 non-human primate tissues. E The number of molecular entries and unique molecules in 14 rat tissues. F The numbers of molecular entries and unique molecules in 11 mouse tissues.

Web interface of ProMENDA

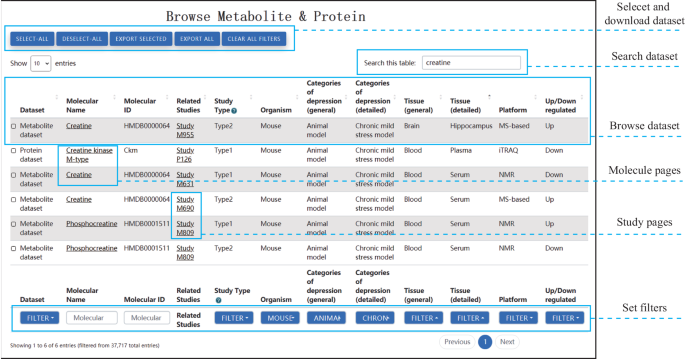

To facilitate the storage and access of study-level and molecular-level datasets, a new web interface was developed for ProMENDA. This interface comprises three main web pages, including Browse, Search, and Download.

Browse page: The Browse page features interactive tables that present molecular and study information, providing web links for each study and molecule (Fig. 3 ). Users can easily search these tables by using search columns and applying filters based on study type, organism, categories of depression, tissue, platform, and up/down-regulation. Users are also allowed to select and download data of interest. Basic information about the molecule is provided on the web page of each molecule and the related data entries are summarized. On the web page of each study, its experimental design and candidate molecules are listed.

The web interface allows users to easily browse, search, filter, and download molecular entries of interest. The browse page displays molecular entries in an interactive table format, enabling users to quickly access relevant information.

(ii) Search page: On the Search page, users can search for protein or metabolite entries using molecular names or IDs. Each query generates hyperlinks for relevant molecules and their links to other databases, including UniProt, HMDB, KEGG, and PubChem [ 25 , 29 , 30 , 31 ].

(iii) Download page: The Download page provides free access to the core datasets of ProMENDA, with additional information available in the Excel documents.

(iv) Others: In addition to the pages mentioned above, ProMENDA also offers other pages in its web interface, including Home, Introduction, News, Tutorial, and Contact pages. These pages enhance the user experience and provide users with a complete understanding of ProMENDA and its features.

Use case: investigating molecular changes in the brains of animal models of depression