Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Gender Studies › Analysis of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own

Analysis of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on October 11, 2020 • ( 1 )

In her highly influential critical A Room of Ones Own (1929), Virginial Woolf studied the cultural, economical and educational disabilities within the patriarchal system that prevent women from realising their creative potential. With her imaginary character Judith (Shakespeare’s fictional sister), she illustrated that a woman with Shakespeare’s faculties would have been denied the opportunities that Shakespeare enjoyed. Examining the careers and works of woman authors like Aphra Behn , Jane Austen , George Eliot and the Bronte sisters, Woolf argued that the patriarchal education system and reading practices condition (or “interpellate,” to use an Althusserian term) women to read from men’s point of view, and make them internalise the aesthetics and literary values created/ adopted by male authors and critics within the patriarchal system — wherein, these values, although male centered are assumed and promoted as universal.

It is in this polemical work, that Woolf suggested that language is gendered, thus inaugurating the language debate, and argued that the woman author, having no other language at her command, is forced to use the sexist/ masculine language. Dale Spender (in her Man Made Language ) as well as the French Feminists primarily investigated the gendered nature of language- Helene Cixous ( Ecriture Feminine ), Julia Kristeva ( chora , semiotic language ) and Luce lrigaray ( Écriture féminine ).

Woolf also realized the need for a narrative form to capture the fluid, incoherent female experiences that defy order and rationality; and hence her employment of the stream-of-consciousness technique in her novels, capturing the lives of Mrs Dalloway, Mrs Ramsay and so on. Inspired by the psychological theories of Carl Jung , Woolf also proposed the concept of the androgynous creative mind, which she fictionalised through Orlando , in an attempt to go beyond the male/female binary. She believed that the best artists were always a combination of the man and the woman or “woman-manly” or “man-womanly”.

Woolf was already connecting feminism to anti-fascism in A Room of One’s Own , which addresses in some detail the relations between politics and aesthetics. The book is based on lectures Woolf gave to women students at Cambridge, but its innovatory style makes it read in places like a novel, blurring boundaries between criticism and fiction. It is regarded as the first modern primer for feminist literary criticism, not least because it is also a source of many, often conflicting, theoretical positions. The title alone has had enormous impact as cultural shorthand for a modern feminist agenda. Woolf ’s room metaphor not only signifies the declaration of political and cultural space for women, private and public, but the intrusion of women into spaces previously considered the spheres of men. A Room of One’s Own is not so much about retreating into a private feminine space as about interruptions, trespassing and the breaching of boundaries (Kamuf, 1982: 17). It oscillates on many thresholds, performing numerous contradictory turns of argument (Allen, 1999). But it remains a readable and accessible work, partly because of its playful fictional style: the narrator adopts a number of fictional personae and sets out her argument as if it were a story. In this reader-friendly manner some complicated critical and theoretical issues are introduced. Many works of criticism, interpretation and theory have developed from Woolf’s original points in A Room of One’s Own , and many critics have pointed up the continuing relevance of the book, not least because of its open construction and resistance to intellectual closure (Stimpson, 1992: 164; Laura Marcus, 2000: 241). Its playful narrative strategies have divided feminist responses, most notably prompting Elaine Showalter’s disapproval (Showalter, 1977: 282). Toril Moi’s counter to Showalter’s critique forms the basis of her classic introduction to French feminist theory, Sexual/Textual Politics (1985), in which Woolf’s textual playfulness is shown to anticipate the deconstructive and post-Lacanian theories of Hélène Cixous, Julia Kristeva and Luce Irigaray.

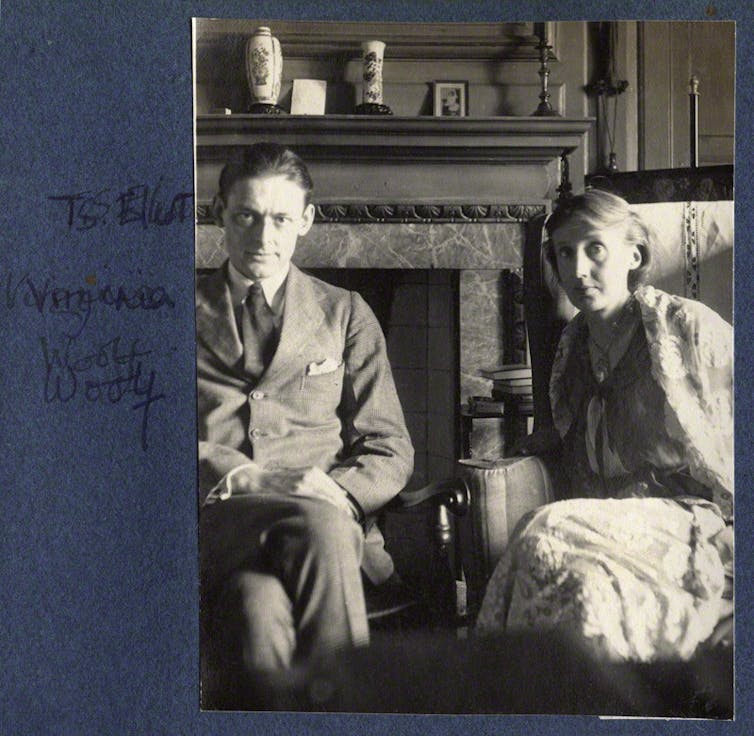

Virginia_Woolf/George Charles Beresford

Although much revised and expanded, the final version of A Room of One’s Own retains the original lectures’ sense of a woman speaking to women. A significant element of Woolf ’s experimental fictional narrative strategy is her use of shifting narrative personae to voice the argument. She anticipates recent theoretical concerns with the constitution of gender and subjectivity in language in her opening declaration that ‘ ‘‘I’’ is only a convenient term for somebody who has no real being . . . (callme Mary Beton, Mary Seton,Mary Carmichael or by any name you please – it is not a matter of any importance)’ (Woolf, 1929: 5). And A Room of One’s Own is written in the voice of at least one of these Mary figures, who are to be found in the Scottish ballad ‘The Four Marys’. Much of the argument is ventriloquised through the voice of Woolf’s own version of ‘Mary Beton’. In the course of the book this Mary encounters new versions of the other Marys – Mary Seton has become a student at ‘Fernham’ college, and Mary Carmichael an aspiring novelist – and it has been suggested that Woolf ’s opening and closing remarks may be in the voice of Mary Hamilton (the narrator of the ballad). The multi-vocal, citational A Room of One’s Own is full of quotations from other texts too. The allusion to the Scottish ballad feeds a subtext in Woolf’s argument concerning the suppression of the role of motherhood – Mary Hamilton sings the ballad from the gallows where she is to be hanged for infanticide. (Marie Carmichael, furthermore, is the nom de plume of contraceptive activist Marie Stopes who published a novel, Love’s Creation , in 1928.)

The main argument of A Room of One’s Own , which was entitled ‘Women and Fiction’ in earlier drafts, is that ‘a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction’ (1929: 4). This is a materialist argument that, paradoxically, seems to differ from Woolf’s apparent disdain for the ‘materialism’ of the Edwardian novelists recorded in her key essays on modernist aesthetics, ‘Modern Fiction’ (1919; 1925) and ‘Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown’ (1924). The narrator of A Room of One’s Own begins by telling of her experience of visiting an Oxbridge college where she was refused access to the library because of her gender. She compares in some detail the splendid opulence of her lunch at a men’s college with the austerity of her dinner at a more recently established women’s college (Fernham). This account is the foundation for the book’s main, materialist, argument: ‘intellectual freedom depends upon material things’ (1929: 141). The categorisation of middle-class women like herself with the working classes may seem problematic, but in A Room of One’s Own Woolf proposes that women be understood as a separate class altogether, equating their plight with the working classes because of their material poverty, even among the middle and upper classes (1929: 73–4).

Woolf’s image of the spider’s web, which she uses as her simile for the material basis of literary production, has become known in literary criticism as ‘Virginia’s web’. It is conceived in the passage where the narrator of A Room of One’s Own begins to consider the apparent dearth of literature by women in the Elizabethan period:

fiction is like a spider’s web, attached ever so lightly perhaps, but still attached to life at all four corners. Often the attachment is scarcely perceptible; Shakespeare’s plays, for instance, seem to hang there complete by themselves. But when the web is pulled askew, hooked up at the edge, torn in the middle, one remembers that these webs are not spun in mid-air by incorporeal creatures, but are the work of suffering human beings, and are attached to grossly material things, like health and money and the houses we live in. (1929: 62–3)

According to this analysis, literary materialism may be understood in several different ways. To begin with, the materiality of writing itself is acknowledged: it is physically made, and not divinely given or unearthly and transcendent. Woolf seems to be attempting to demystify the solitary, romantic figure of the (male) poet or author as mystically singled out, or divinely elected. But the idea that a piece of writing is a material object is also connected to a strand of modernist aesthetics concerned with the text as self-reflexive object, and to a more general sense of the concreteness of words, spoken or printed. Woolf’s spider’s web also suggests, furthermore, that writing is a bodily process, physically produced. The observation that writing is ‘the work of suffering human beings’ suggests that literature is produced as compensation for, or in protest against, existential pain and material lack. Finally, in proposing writing as ‘attached to grossly material things’, Woolf is delineating a model of literature as grounded in the ‘real world’, that is in the realms of historical, political and social experience. Such a position has been interpreted as broadly Marxist, but although Woolf ’s historical materialism may ‘gladden the heart of a contemporary Marxist feminist literary critic’, as Miche`le Barrett has noted, elsewhere Woolf, in typically contradictory fashion, ‘retains the notion that in the correct conditions art may be totally divorced from economic, political or ideological constraints’ (Barrett, 1979: 17, 23). Yet perhaps Woolf’s feminist ideal is in fact for women’s writing to attain, not total divorce from material constraints, but only the near-imperceptibility of the attachment of Shakespeare’s plays to the material world, which ‘seem to hang there complete by themselves’ but are nevertheless ‘still attached to life at all four corners’.

As well as underlining the material basis for women’s achieving the status of writing subjects, A Room of One’s Own also addresses the status of women as readers, and raises interesting questions about gender and subjectivity in connection with the gender semantics of the first person. After looking at the difference between men’s and women’s experiences of University, the narrator of A Room of One’s Own visits the British Museum where she researches ‘Women and Poverty’ under an edifice of patriarchal texts, concluding that women ‘have served all these centuries as looking glasses . . . reflecting the figure of man at twice his natural size’ (Woolf, 1929: 45). Here Woolf touches upon the forced, subordinate complicity of women in the construction of the patriarchal subject. Later in the book, Woolf offers a more explicit model of this when she describes the difficulties for a woman reader encountering the first person pronoun in the novels of ‘Mr A’: ‘a shadow seemed to lie across the page. It was a straight dark bar, a shadow shaped something like the letter ‘I’ . . . Back one was always hailed to the letter ‘I’ . . . In the shadow of the letter ‘I’ all is shapeless as mist. Is that a tree? No it is a woman’ (1929: 130). For a man to write ‘I’ seems to involve the positioning of a woman in its shadow, as if women are not included as writers or users of the first person singular in language. This shadowing or eliding of the feminine in the representation and construction of subjectivity not only emphasizes the alienation experienced by women readers of male-authored texts, but also suggests the linguistic difficulties for women writers in trying to express feminine subjectivity when the language they have to work with seems to have already excluded them. When the word ‘I’ appears, the argument goes, it is always and already signifying a masculine self.

The narrator of A Room of One’s Own discovers that language, and specifically literary language, is not only capable of excluding women as its signified meaning, but also uses concepts of the feminine itself as signs. Considering both women in history and woman as sign, Woolf’s narrator points out that there is a significant discrepancy between women in the real world and ‘woman’ in the symbolic order (that is, as part of the order of signs in the aesthetic realm):

Imaginatively she is of the highest importance; practically she is completely insignificant. She pervades poetry from cover to cover; she is all but absent from history. She dominates the lives of kings and conquerors in fiction; in fact she was the slave of any boy whose parents forced a ring upon her finger. Some of the most inspired words, some of the most profound thoughts in literature fall from her lips; in real life she could scarcely spell, and was the property of her husband. (1929: 56)

Woolf here emphasizes not only the relatively sparse representation of women’s experience in historical records, but also the more complicated business of how the feminine is already caught up in the conventions of representation itself. How is it possible for women to be represented at all when ‘woman’, in poetry and fiction, is already a sign for something else? In these terms, ‘woman’ is a signifier in patriarchal discourse, functioning as part of the symbolic order, and what is signified by such signs is certainly not the lived, historical and material experience of real women. Woolf understands that this ‘odd monster’ derived from history and poetry, this ‘worm winged like an eagle; the spirit of life and beauty in a kitchen chopping suet’, has ‘no existence in fact’ (1929: 56).

Woolf converts this dual image to a positive emblem for feminist writing, by thinking ‘poetically and prosaically at one and the same moment, thus keeping in touch with fact – that she is Mrs Martin, aged thirty-six, dressed in blue, wearing a black hat and brown shoes; but not losing sight of fiction either – that she is a vessel in which all sorts of spirits and forces are coursing and flashing perpetually’ (1929: 56–7). This dualistic model, combining prose and poetry, fact and imagination is also central to Woolf ’s modernist aesthetic, encapsulated in the term ‘granite and rainbow’, which renders in narrative both the exterior, objective and factual (‘granite’), and the interior, subjective experience and consciousness (‘rainbow’). The modernist technique of ‘Free Indirect Discourse’ practised and developed by Woolf allows for this play between the objective and subjective, between third person and first person narrative.

A Room of One’s Own can be confusing because it puts forward contradictory sets of arguments, not least Woolf’s much-cited passage on androgyny, which has been influential on later deconstructive theories of gender. Her narrator declares: ‘it is fatal for anyone who writes to think of their sex’ (1929: 136) and a model of writerly androgyny is put forward, derived from Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s work:

one must be woman-manly or man-womanly. It is fatal for a woman to lay the least stress on any grievance; to plead even with justice any cause; in any way to speak consciously as a woman . . . Some collaboration has to take place in the mind between the woman and the man before the art of creation can be accomplished. Some marriage of opposites has to be accomplished. (1929: 136)

Shakespeare, the poet playwright, is Woolf ’s ideal androgynous writer. She lists others – all men – who have also achieved androgyny (Keats, Sterne, Cowper, Lamb, and Proust – the only contemporary). But if the ideal is for both women and men to achieve androgyny, elsewhere A Room of One’s Own puts the case for finding a language that is gendered – one appropriate for women to use when writing about women.

One of the most controversial of Woolf ’s speculations in A Room of One’s Own concerns the possibility of an inherent politics in aesthetic form, exemplified by the proposition that literary sentences are gendered. A Room of One’s Own culminates in the prophecy of a woman poet to equal or rival Shakespeare: ‘Shakespeare’s sister’. But in collectively preparing for her appearance, women writers need to develop aesthetic form in several respects. In predicting that the aspiring novelist Mary Carmichael ‘will be a poet . . . in another hundred years’ time’ (1929: 123), Mary Beton seems to be suggesting that prose must be explored and exploited in certain ways by women writers before they can be poets. She also finds fault with contemporary male writers, such as Mr A who is ‘protesting against the equality of the other sex by asserting his own superiority’ (1929: 132). She sees this as the direct result of women’s political agitation for equality: ‘The Suffrage campaign was no doubt to blame’ (1929: 129). She raises further concerns about politics and aesthetics when she comments on the aspirations of the Italian Fascists for a poet worthy of fascism: ‘The Fascist poem, one may fear, will be a horrid little abortion such as one sees in a glass jar in the museum of some county town’ (1929: 134). Yet if the extreme patriarchy of fascism cannot produce poetry because it denies a maternal line, Woolf argues that women cannot write poetry either until the historical canon of women’s writing has been uncovered and acknowledged. Nineteenth-century women writers experienced great difficulty because they lacked a female tradition: ‘For we think back through our mothers if we are women’ (1929: 99). They therefore lacked literary tools suitable for expressing women’s experience. The dominant sentence at the start of the nineteenth century was ‘a man’s sentence . . . It was a sentence that was unsuited for women’s use’ (1929: 99–100).

Woolf ’s assertion here, through Mary Beton, that women must write in gendered sentence structure, that is develop a feminine syntax, and that ‘the book has somehow to be adapted to the body’ (1929: 101) seems to contradict the declaration that ‘it is fatal for anyone who writes to think of their sex’. She identifies the novel as ‘young enough’ to be of use to the woman writer: ‘No doubt we shall find her knocking that into shape for herself . . . and providing some new vehicle, not necessarily in verse, for the poetry in her. For it is the poetry that is still denied outlet. And I went on to ponder how a woman nowadays would write a poetic tragedy in five acts’ (1929: 116). Now the goal of A Room of One’s Own has shifted from women’s writing of fictional prose to poetry, the genre Woolf finds women least advanced in, while ‘poetic tragedy’ is Shakespeare’s virtuoso form and therefore the form to which ‘Shakespeare’s sister’ should aspire.Woolf ’s speculations on feminine syntax anticipate the more recent exploration of é criture féminine by French feminists such as Cixous. Woolf ’s interest in the body and bodies, in writing the body, and in the gender and positionality thereof, anticipates feminist investigations of the somatic, and has been understood as materialist, deconstructive and phenomenological (Doyle, 2001). Woolf’s interest in matters of the body also fuels the sustained critique, in A Room of One’s Own , of ‘reason’, or masculinist rationalism, as traditionally disembodied and antithetical to the (traditionally feminine) material and physical.

A Room of One’s Own is concerned not only with what form of literary language women writers use, but also with what they write about. Inevitably women themselves constitute a vital subject matter for women writers. Women writers will need new tools to represent women properly. The assertion of woman as both the writing subject and the object of writing is reinforced in several places: ‘above all, you must illumine your own soul’ (Woolf, 1929: 117), Mary Beton advises. The ‘obscure lives’ (1929: 116) of women must be recorded by women. The example supplied is Mary Carmichael’s novel which is described as exploring women’s relationships with each other. A Room of One’s Own was published shortly after the obscenity trial of Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness (1928), and in the face of this Woolf flaunts a blatantly lesbian narrative: ‘if Chloe likes Olivia and Mary Carmichael knows how to express it she will light a torch in that vast chamber where nobody has yet been’ (1929: 109). Her refrain, ‘Chloe likes Olivia’, has become a critical slogan for lesbian writing. In A Room of One’s Own , Woolf makes ‘coded’ references to lesbian sexuality in her account of Chloe and Olivia’s shared ‘laboratory’ (Woolf, 1929: 109; Marcus, 1987: 152, 169), and she calls for women’s writing to explore lesbianism more openly and for the narrative tools to make this possible.

One of the most controversial and contradictory passages in A Room of One’s Own concerns Woolf’s positioning of black women. Commenting on the sexual and colonial appetites of men, the narrator concludes: ‘It is one of the great advantages of being a woman that one can pass even a very fine negress without wishing to make an Englishwoman of her’ (1929: 65). A number of feminist critics have questioned the relevance of Woolf’s feminist manifesto for the experience of black women (Walker, 1985: 2377), and have scrutinised this sentence in particular (Marcus, 2004: 24–58). In seeking to distance women from imperialist and colonial practices, Woolf disturbingly excludes black women here from the very category of women. This has become the crux of much contemporary feminist debate concerning the politics of identity. The category of women both unites and divides feminists: white middle-class feminists, it has been shown, cannot speak for the experience of all women; and reconciliation of universalism and difference remains a key issue. ‘Women – but are you not sick to death of the word?’ Woolf retorts in the closing pages of A Room of One’s Own , ‘I can assure you I am’ (Woolf, 1929: 145). The category of women is not chosen by women, it represents the space in patriarchy from which women must speak and which they struggle to redefine.

Another contradictory concept in A Room of One’s Own is ‘Shakespeare’s sister’, a figure who represents the possibility that there will one day be a woman writer to match the status of Shakespeare, who has come to personify literature itself. ‘Judith Shakespeare’ stands for the silenced woman writer or artist. But to seek to mimic the model of the individual masculine writing subject may also be considered part of a conservative feminist agenda. On the other hand, Woolf seems to defer the arrival of Shakespeare’s sister in a celebration of women’s collective literary achievement – ‘I am talking of the common life which is the real life and not of the little separate lives which we live as individuals’ (1929 148–9). Shakespeare’s sister is a messianic figure who ‘lives in you and in me’ (1929: 148) and who will draw ‘her life from the lives of the unknown who were her forerunners’ (1929: 149), but has yet to appear. She may be the common writer to Woolf’s ‘common reader’ (a term she borrows from Samuel Johnson), but she has yet to ‘put on the body which she has so often laid down’ (1929: 149). A Room of One’s Own closes with this contradictory model of individual achievement and collective effort.

Barrett, Miche`le (1979), ‘Introduction’, in Virginia Woolf on Women and Writing, ed. Miche`le Barrett, London: Women’s Press. Goldman, Jane (1998), The Feminist Aesthetics of Virginia Woolf: Modernism, Post- Impressionism, and the Politics of the Visual, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Gruber, Ruth (2005), Virginia Woolf: The Will to Create as a Woman, New York: Carroll & Graf. Harrison, Jane (1925), Reminiscences of a Student Life, London: Hogarth Press. Hartman, Geoffrey (1970), ‘Virginia’s Web’, in Beyond Formalism: Literary Essays 1958–1970, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, and Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. Holtby, Winifred (1932), Virginia Woolf, London: Wishart. Kamuf, Peggy (1982), ‘Penelope at Work: Interruptions in A Room of One’s Own’, in Novel 16. Moi, Toril (1985), Sexual/Textual Politics: Feminist Literary Theory, London: Methuen. Showalter, Elaine (1977), A Literature of Their Own: British Women Novelists from Bronte¨ to Lessing, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Stimpson, Catherine (1992), ‘Woolf’s Room, Our Project: The Building of Feminist Criticism’, in Virginia Woolf: Longman Critical Readers, ed. Rachel Bowlby, London: Longman. Woolf, Virginia (1929), A Room of One’s Own, London: Hogarth.

Main Source: Plain, Gill, and Susan Sellers. A History of Feminist Literary Criticism . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Share this:

Categories: Gender Studies

Tags: A Room of One’s Own , A Room of One’s Own Feminism , Analysis of Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own , Commentary Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own , Criticism of Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own , Essays on Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own , Feminism , Feminsit Reading of A Room of One’s Own , Literary Criticism , Literary Theory , Summary of Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own , Synopsis Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own , Themes of Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own , Virginia Woolf , Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own , Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own Analysis , Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own Criticism , Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own Explanation , Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own Notes

Related Articles

- Why this book is a MUST-READ for contemporary female writers. - WORDNAMA

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Guide to the classics: A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf’s feminist call to arms

Professor of English Literature, University of Southern Queensland

Disclosure statement

Jessica Gildersleeve does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Southern Queensland provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

I sit at my kitchen table to write this essay, as hundreds of thousands of women have done before me. It is not my own room, but such things are still a luxury for most women today. The table will do. I am fortunate I can make a living “by my wits,” as Virginia Woolf puts it in her famous feminist treatise, A Room of One’s Own (1929).

That living enabled me to buy not only the room, but the house in which I sit at this table. It also enables me to pay for safe, reliable childcare so I can have time to write.

It is as true today, therefore, as it was almost a century ago when Woolf wrote it, that “a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction” — indeed, write anything at all.

Still, Woolf’s argument, as powerful and influential as it was then — and continues to be — is limited by certain assumptions when considered from a contemporary feminist perspective.

Woolf’s book-length essay began as a series of lectures delivered to female students at the University of Cambridge in 1928. Its central feminist premise — that women writer’s voices have been silenced through history and they need to fight for economic equality to be fully heard — has become so culturally pervasive as to enter the popular lexicon.

Julia Gillard’s A Podcast of One’s Own , takes its lead from the essay, as does Anonymous Was a Woman , a prominent arts funding body based in New York.

Even the Bechdel-Wallace test , measuring the success of a narrative according to whether it features at least two named women conversing about something other than a man, can be seen to descend from the “Chloe liked Olivia” section of Woolf’s book. In this section, the hypothetical characters of Chloe and Olivia share a laboratory, care for their children, and have conversations about their work, rather than about a man.

Woolf’s identification of women as a poorly paid underclass still holds relevance today, given the gender pay gap. As does her emphasis on the hierarchy of value placed on men’s writing compared to women’s (which has led to the establishment of awards such as the Stella Prize ).

Read more: Friday essay: science fiction's women problem

Invisible women

In her book, Woolf surveys the history of literature, identifying a range of important and forgotten women writers, including novelists Jane Austen, George Eliot and the Brontes, and playwright Aphra Behn .

In doing so, she establishes a new model of literary heritage that acknowledges not only those women who succeeded, but those who were made invisible: either prevented from working due to their sex, or simply cast aside by the value systems of patriarchal culture.

Read more: Friday essay: George Eliot 200 years on - a scandalous life, a brilliant mind and a huge literary legacy

To illustrate her point, she creates Judith, an imaginary sister of the playwright Shakespeare.

What if such a woman had shared her brother’s talents and was as adventurous, “as agog to see the world” as he was? Would she have had the freedom, support and confidence to write plays? Tragically, she argues, such a woman would likely have been silenced — ultimately choosing suicide over an unfulfilled life of domestic servitude and abuse.

In her short, passionate book, Woolf examines women’s letter writing, showing how it can illustrate women’s aptitude for writing, yet also the way in which women were cramped and suppressed by social expectations.

She also makes clear that the lack of an identifiable matrilineal literary heritage works to impede women’s ability to write.

Indeed, the establishment of those major women writers in the 18th and 19th centuries (George Eliot, the Brontes et al), when “the middle-class woman began to write” is, Woolf argues, a moment in history “of greater importance than the Crusades or the War of the Roses”.

Male critics such as T.S. Eliot and Harold Bloom have identified a (male) writer’s relation to his precursors as necessary for his own literary production. But how, Woolf asks, is a woman to write if she has no model to look back on or respond to? If we are women, she wrote, “we think back through our mothers”.

Read more: #ThanksforTyping: the women behind famous male writers

Her argument inspired later feminist revisionist work of literary critics like Elaine Showalter , Sandra K. Gilbert and Susan Gubar who sought to restore the reputation of forgotten women writers and turn critical attention to women’s writing as a field worthy of dedicated study.

All too often in history, Woolf asserts, “Woman” is simply the object of the literary text — either the adored, voiceless beauty to whom the sonnet is dedicated or reflecting back the glow of man himself.

Women have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size.

A Room of One’s Own returns that authority to both the woman writer and the imagined female reader whom she addresses.

Stream of consciousness

A Room of One’s Own also demonstrates several aspects of Woolf’s modernism. The early sections demonstrate her virtuoso stream of consciousness technique. She ruminates on women’s position in, and relation to, fiction while wandering through the university campus, driving through country lanes, and dawdling over a leisurely, solo lunch.

Critically, she employs telling patriarchal interruptions to that flow of thought.

A beadle waves his arms in exasperation as she walks on a private patch of grass. A less-than-satisfactory dinner is served to the women’s college. A “deprecating, silvery, kindly gentleman” turns her away from the library. These interruptions show the frequent disruption to the work of a woman without a room.

This is the lesson also imparted in Woolf’s 1927 novel To the Lighthouse where artist Lily Briscoe must shed the overbearing influence of Mr and Mrs Ramsay, a couple who symbolise Victorian culture, if she is to “have her vision”. The flights and flow of modernist technique are not possible without the time and space to write and think for herself.

A Room of One’s Own has been crucial to the feminist movement and women’s literary studies. But it is not without problems. Woolf admits her good fortune in inheriting £500 a year from an aunt.

Indeed her purse now “breed(s) ten-shilling notes automatically”.

Part of the purpose of the essay is to encourage women to make their living through writing.

But Woolf seems to lack an awareness of her own privilege and how much harder it is for most women to fund their own artistic freedom. It is easy for her to advise against “doing work that one did not wish to do, and to do it like a slave, flattering and fawning”.

In her book, Woolf also criticises the “awkward break” in Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (1847), in which Bronte’s own voice interrupts the narrator’s in a passionate protest against the treatment of women.

Here, Woolf shows little tolerance for emotion, which has historically often been dismissed as hysteria when it comes to women discussing politics.

A Room of One’s Own ends with an injunction to work for the coming of Shakespeare’s sister, that woman forgotten by history. “So to work, even in poverty and obscurity, is worthwhile”.

Such a woman author must have her vision, even if her work will be “stored in attics” rather than publicly exhibited.

The room and the money are the ideal, we come to see, but even without them the woman writer must write, must think, in anticipation of a future for her daughter-artists to come.

An adaptation of A Room of One’s Own is currently at Sydney’s Belvoir Theatre.

- Julia Gillard

- English literature

- Virginia Woolf

- Women's writing

Research Fellow

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

A Summary and Analysis of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

A Room of One’s Own is Virginia Woolf’s best-known work of non-fiction. Although she would write numerous other essays, including a little-known sequel to A Room of One’s Own , it is this 1929 essay – originally delivered as several lectures at the University of Cambridge – which remains Woolf’s most famous statement about the relationship between gender and writing.

Is A Room of One’s Own a ‘feminist manifesto’ or a work of literary criticism? In a sense, it’s a bit of both, as we will see. Before we offer an analysis of Woolf’s argument, however, it might be worth breaking down what her argument actually is . You can read the essay in full here .

A Room of One’s Own : summary

Woolf’s essay is split into six chapters. She begins by making what she describes as a ‘minor point’, which explains the title of her essay: ‘a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.’ She goes on to specify that an inheritance of five hundred pounds a year – which would give a woman financial independence – is more important than women getting the vote (women had only attained completely equal suffrage to men in 1928, the same year that Woolf delivered her lectures).

Woolf adopts a fictional persona named ‘Mary Beton’, and addresses her audience (and readers) using this identity. This name has its roots in an old Scottish ballad usually known as either ‘Mary Hamilton’ or ‘The Four Marys’ and concerns Mary Hamilton, a lady-in-waiting to a Queen of Scotland. Mary falls pregnant by the King, but kills the baby and is later sentenced to be executed for her crime. ‘Mary Beton’ is one of the other three Marys in the ballad.

Woolf considers the ways in which women have been shut out from social and political institutions throughout history, illustrating her argument by observing that she, as a woman, would not be able to gain access to a manuscript kept within an all-male college at ‘Oxbridge’ (a rhetorical hybrid of Oxford and Cambridge; Woolf originally delivered A Room of One’s Own to the students of one of the colleges for women which had recently been founded at Cambridge, but these female students were still forbidden to go to certain spaces within all-male colleges at the university).

Next, Woolf turns her attention to what men have said about women in writing, and gets the distinct impression that men – who have a vested interest in retaining the upper hand when it comes to literature and education – portray women in certain ways in order to keep them as, effectively, second-class citizens.

Woolf’s next move is to consider what women themselves have written. It is at this point in A Room of One’s Own that Woolf invents a (fictional) sister to Shakespeare, whom Woolf (perhaps recalling the name of Shakespeare’s own daughter) calls ‘Judith Shakespeare’. (Incidentally, Woolf’s invention of ‘Shakespeare’s sister’ inspired a song by The Smiths of that name and the name of a female pop duo .)

Woolf invites us to imagine that this imaginary sister of William Shakespeare was born with the same genius, the same potential to become a great writer as her brother. But she is shut off from the opportunities her brother enjoys: grammar-school education, the chance to become an actor in London, the opportunity to earn a living in the Elizabethan theatre.

Instead, ‘Judith Shakespeare’ would find the doors to these institutions closed in her face, purely because she was born a woman. Woolf’s point is made in response to people who claim that a woman writer as great as Shakespeare has never been born; this claim misses the important fact that great writers are made as well as born, and few women in Shakespeare’s time enjoyed the opportunities men like Shakespeare had.

Woolf’s ‘Judith’ is seduced by an actor-manager in the London playhouses, she falls pregnant, and takes her own life in poverty and misery.

Woolf then returns to a survey of what women’s writing does exist, considering such authors as Jane Austen and Emily Brontë (both of whom she admires), as well as Aphra Behn, the first professional female author in England, whom Woolf argues should be praised by all women for showing that the professional woman writer could become a reality.

Behn, writing in the seventeenth century, was an important breakthrough for all women ‘for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds.’ Earlier women writers were too constrained by their insecurity – as women writing in a male-dominated literary world – and this leads to a ‘flaw’ in their work.

But nineteenth-century novelists like Austen and George Eliot were ‘trained’ in social observation, and this enabled them to write novels about the world she knew:

Jane Austen hid her manuscripts or covered them with a piece of blotting-paper. Then, again, all the literary training that a woman had in the early nineteenth century was training in the observation of character, in the analysis of emotion. Her sensibility had been educated for centuries by the influences of the common sitting-room. People’s feelings were impressed on her; personal relations were always before her eyes. Therefore, when the middle-class woman took to writing, she naturally wrote novels.

But even this led to limitations: Emily Brontë’s genius was better-suited to poetic plays than to novels, while George Eliot would have made full use of her talents as a biographer and historian rather than as a novelist. So even here, women had to bend their talents into a socially acceptable form, and at the time this meant writing novels.

Woolf contrasts these nineteenth-century women novelists with women novelists of today (i.e., the 1920s). She discusses a recent novel, Life’s Adventure by Mary Carmichael. (Both the novel and the writer are fictional, invented by Woolf for the purpose of her argument.) In this novel, she finds some quietly revolutionary details, including the depiction of friendship between women , where novels had previously viewed women only in relation to men (e.g., as wives, daughters, friends, or mothers).

Woolf concludes by arguing that in fact, the ideal writer should be neither narrowly ‘male’ or ‘female’ but instead should strive to be emotionally and psychologically androgynous in their approach to gender. In other words, writers should write with an understanding of both masculinity and femininity, rather than writing ‘merely’ as a woman or as a man. This will allow writers to encompass the full range of human emotion and experience.

A Room of One’s Own : analysis

Woolf’s essay, although a work of non-fiction, shows the same creative flair we find in her fiction: her adoption of the Mary Beton persona, her beginning her essay mid-flow with the word ‘But’, and her imaginative weaving of anecdote and narrative into her ‘argument’ all, in one sense, enact the two-sided or ‘androgynous’ approach to writing which, she concludes, all authors should strive for.

A Room of One’s Own is both rational, linear argument and meandering storytelling; both deadly serious and whimsically funny; both radically provocative and, in some respects, quietly conservative.

Throughout, Woolf pays particular attention to not just the social constraints on women’s lives but the material ones. This is why the line which provides her essay with its title – ‘a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction’ – is central to her thesis.

‘Judith Shakespeare’, William Shakespeare’s imagined sister, would never have become a great writer because the financial arrangements for women were not focused on educating them so that they could become breadwinners for their families, but on preparing them for marriage and motherhood. Their lives were structured around marriage as the most important economic and material event in their lives, for it was by becoming a man’s wife that a woman would attain financial security.

Such a woman, at least until the late nineteenth century when the Married Women’s Property Act came into English law, would usually have neither ‘a room of her own’ (because the rooms in which she would spend her time, such as the kitchen, bedroom, and nursery, were designed for domestic activities) nor money (because the wife’s wealth and property would, technically, belong to her husband).

Because of this strong focus on the material limitations on women, which in turn prevent them from gaining the experience, the education, or the means required to become great writers, A Room of One’s Own is often described as a ‘feminist’ work. This label is largely accurate, although it should be noted that Woolf’s opinion about women’s writing diverges somewhat from that of many other feminist writers and critics.

In particular, Woolf’s suggestion that writers should strive to be ‘androgynous’ has attracted criticism from later feminist critics because it denies the idea that ‘women’s writing’ and ‘women’s experience’ are distinct and separate from men’s. If women truly are treated as inferior subjects in a patriarchal society, then surely their experience of that society is markedly different from men’s, and they need what Elaine Showalter called ‘a literature of their own’ as well as a room of their own?

Later feminist thinkers, such as the French theorist Hélène Cixous, have suggested there is a feminine writing ( écriture feminine ) which stands as an alternative to a more ‘masculine’ kind of writing: where male writing is about constructing a reality out of solid, materialist details, feminine writing (and much modernist writing, including Woolf’s fiction, is ‘feminine’ in this way) is about the ‘spiritual’ or psychological aspects of everyday living, the daydreams and gaps, the seemingly ‘unimportant’ moments we experience in our day-to-day lives. It is also more meandering, less teleological or concerned with an end-point (marriage, death, resolution), than traditional male writing.

Given how much of Woolf’s fiction is written in this way and might therefore be described as écriture feminine , one wonders how far her argument in A Room of One’s Own is borne out by her own fiction.

Perhaps the answer lies in the novel Woolf had published shortly before she began writing A Room of One’s Own : her 1928 novel Orlando , in which the heroine changes gender throughout the novel as she journeys through three centuries of history. Indeed, if one wished to analyse one work of fiction by Woolf alongside A Room of One’s Own , Orlando might be the ideal choice.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Presented by the family of Eleanor Chilton Agar ’22 Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College

Back to Home next: Woolf's letter to Katherine Mansfield

- Divisions and Offices

- Grants Search

- Manage Your Award

- NEH's Application Review Process

- Professional Development

- Grantee Communications Toolkit

- NEH Virtual Grant Workshops

- Awards & Honors

- American Tapestry

- Humanities Magazine

- NEH Resources for Native Communities

- Search Our Work

- Office of Communications

- Office of Congressional Affairs

- Office of Data and Evaluation

- Budget / Performance

- Contact NEH

- Equal Employment Opportunity

- Human Resources

- Information Quality

- National Council on the Humanities

- Office of the Inspector General

- Privacy Program

- State and Jurisdictional Humanities Councils

- Office of the Chair

- NEH-DOI Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Partnership

- NEH Equity Action Plan

- GovDelivery

Virginia Woolf Was More Than Just a Women’s Writer

She was a great observer of everyday life..

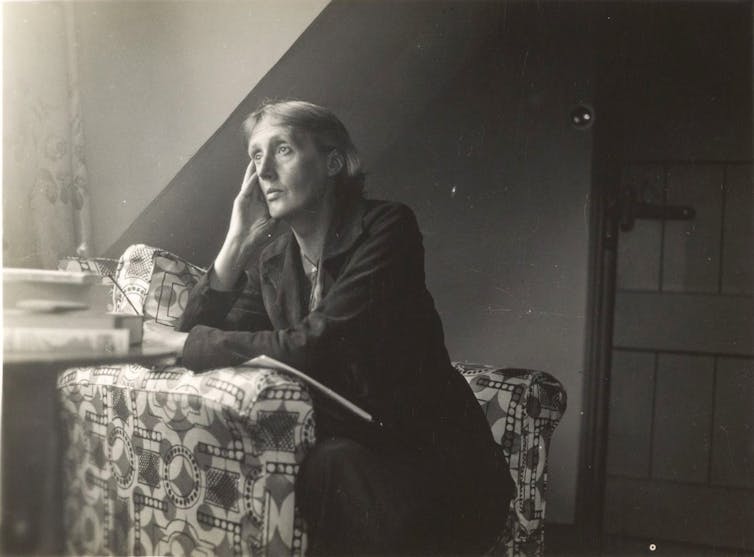

Virginia Woolf, in one of the more lively and often-seen photos of her from the 1930s.

HIP / Art Resource, NY

Virginia Woolf, that great lover of language, would surely be amused to know that, some seven decades after her death, she endures most vividly in popular culture as a pun—within the title of Edward Albee’s celebrated drama, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? In Albee’s play, a troubled college professor and his equally pained wife taunt each other by singing “Who’s Afraid of the Big, Bad Wolf?,” substituting the iconic British writer’s name for that of the fairy-tale villain.

The Woolf reference seems to have no larger meaning, but, perhaps inadvertently, it gives a note of authenticity to the play’s campus setting. Woolf’s experimental novels are much discussed within academia, and her pioneering feminism has given her a special place in women’s studies programs across the country.

It’s a reputation that runs the risk of pigeonholing Woolf as a “women’s writer” and, as a frequent subject of literary theory, the author of books meant to be studied rather than enjoyed. But, in her prose, Woolf is one of the great pleasure-givers of modern literature, and her appeal transcends gender. Just ask Michael Cunningham, author of The Hours , the popular and critically acclaimed novel inspired by Woolf’s classic fictional work, Mrs. Dalloway .

“I read Mrs. Dalloway for the first time when I was a sophomore in high school,” Cunningham told readers of the Guardian newspaper in 2011. “I was a bit of a slacker, not at all the sort of kid who’d pick up a book like that on my own (it was not, I assure you, part of the curriculum at my slacker-ish school in Los Angeles). I read it in a desperate attempt to impress a girl who was reading it at the time. I hoped, for strictly amorous purposes, to appear more literate than I was.”

Cunningham didn’t really understand all of the themes of Dalloway when he first read it, and he didn’t, alas, get the girl who had inspired him to pick up Woolf’s novel. But he fell in love with Woolf’s style. “I could see, even as an untutored and rather lazy child, the density and symmetry and muscularity of Woolf’s sentences,” Cunningham recalled. “I thought, wow, she was doing with language something like what Jimi Hendrix does with a guitar. By which I meant she walked a line between chaos and order, she riffed, and just when it seemed that a sentence was veering off into randomness, she brought it back and united it with the melody.”

Woolf’s example helped drive Cunningham to become a writer himself. His novel The Hours essentially retells Dalloway as a story within a story, alternating between a variation of Woolf’s original narrative and a fictional speculation on Woolf herself. Cunningham’s 1998 novel won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, then was adapted into a 2002 film of the same name, starring Nicole Kidman as Woolf.

“I feel certain she’d have disliked the book—she was a ferocious critic,” Cunningham said of Woolf, who died in 1941. “She’d probably have had reservations about the film as well, though I like to think that it would have pleased her to see herself played by a beautiful Hollywood movie star.”

Kidman created a buzz for the movie by donning a false nose to mute her matinee-perfect face, evoking Woolf as a woman whom family friend Nigel Nicolson once described as “always beautiful but never pretty.”

Woolf, a seminal figure in feminist thought, would probably not have been surprised that a big-screen treatment of her life would spark so much talk about how she looked rather than what she did . But she was also keenly intent on grounding her literary themes within the world of sensation and physicality, so maybe there’s some value, while considering her ideas, in also remembering what it was like to see and hear her.

We know her best in profile. Many pictures of Woolf show her glancing off to the side, like the figure on a coin. The most notable exception is a 1939 photograph by Gisele Freund in which Woolf peers directly into the camera. Woolf hated the photograph—perhaps because, on some level, she knew how deftly Freund had captured her subject. “I loathe being hoisted about on top of a stick for anyone to stare at,” lamented Woolf, who complained that Freund had broken her promise not to circulate the picture.

The most striking aspect of the photo is the intensity of Woolf’s gaze. In both her conversation and her writing, Woolf had a genius for not only looking at a subject, but looking through it, teasing out inferences and implications at multiple levels. It’s perhaps why the sea figures so prominently in her fiction, as a metaphor for a world in which the bright currents we see at the surface of reality reveal, upon closer inspection, a depth that goes downward for miles.

Take, for example, Woolf’s widely anthologized essay, “The Death of the Moth,” in which she notices a moth’s last moments of life, then records the experience as a window into the fragility of all existence. “The insignificant little creature now knew death,” Woolf reports.

As I looked at the dead moth, this minute wayside triumph of so great a force over so mean an antagonist filled me with wonder. . . . The moth having righted himself now lay most decently and uncomplainingly composed. Oh yes, he seemed to say, death is stronger than I am.

Woolf takes an equally miniaturist tack in “The Mark on the Wall,” a sketch in which the narrator studies a mark on the wall ultimately revealed as a snail. Although the premise sounds militantly boring—the literary equivalent of watching paint dry—the mark on the wall works as a locus of concentration, like a hypnotist’s watch, allowing the narrator to consider everything from Shakespeare to World War I. In its subtle tracking of how the mind free-associates and its ample use of interior monolog, the sketch serves as a keynote of sorts for the modernist literary movement that Woolf worked so tirelessly to advance.

Woolf’s penetrating sensibility took some getting used to, since she expected those around her to look at the world just as unblinkingly. She didn’t seem to have much patience for small talk. Renowned scholar Hermione Lee wrote an exhaustive 1997 biography of Woolf, yet confesses some anxiety about the prospect, were it possible, of greeting Woolf in person. “I think I would have been afraid of meeting her,” Lee wrote. “I am afraid of not being intelligent enough for her.”

Nicolson, the son of Woolf’s close friend and onetime lover, Vita Sackville-West, had fond memories of hunting butterflies with Woolf when he was a boy—an outing that allowed Woolf to indulge a pastime she’d enjoyed in childhood. “Virginia could tolerate children for short periods, but fled from babies,” he recalled. Nicolson also remembered Woolf’s distaste for bland generalities, even when uttered by youngsters. She once asked the young Nicolson for a detailed report on his morning, including the quality of the sun that had awakened him, and whether he had first put on his right or left sock while dressing.

“It was a lesson in observation, but it was also a hint,” he wrote many years later. “‘Unless you catch ideas on the wing and nail them down, you will soon cease to have any.’ It was advice that I was to remember all my life.”

Thanks to a commentary Woolf did for the BBC, we don’t have to guess what she sounded like. In the 1937 recording, widely available online, Woolf reflects on how the English language pollinates and blooms into new forms. “Royal words mate with commoners,” she tells listeners in a subversive reference to the recent abdication of King Edward VIII, who had forfeited his throne to marry American Wallis Simpson. Woolf’s voice is plummy and patrician, like an English version of Eleanor Roosevelt. Not surprising, perhaps, given Woolf’s origin in one of England’s most prominent families.

She was born Adeline Virginia Stephen on January 25, 1882, the daughter of Sir Leslie Stephen, a celebrated essayist, editor, and public intellectual, and Julia Prinsep Duckworth Stephen. Julia was, according to Woolf biographer Panthea Reid, “revered for her beauty and wit, her self-sacrifice in nursing the ill, and her bravery in facing early widowhood.” Here’s how Woolf scholar Mark Hussey describes the blended household of Virginia’s childhood:

Her parents, Leslie and Julia Stephen, both previously widowed, began their marriage in 1878 with four young children: Laura (1870–1945), the daughter of Leslie Stephen and his first wife, Harriet Thackery (1840–1875); and George (1868–1934), Gerald (1870–1937), and Stella Duckworth (1869–1897), the children of Julia Prinsep (1846–1895) and Herbert Duckworth (1833–1870).

Together, Leslie and Julia had four more children: Virginia, Vanessa (1879–1961), and brothers Thoby (1880–1906) and Adrian (1883–1948). They all lived at 22 Hyde Park Gate in London.

Although Virginia’s brothers and half-brothers got university educations, Woolf was taught mostly at home—a slight that informed her thinking about how society treated women. Woolf’s family background, though, brought her within the highest circles of British cultural life.

“Woolf’s parents knew many of the intellectual luminaries of the late Victorian era well,” Hussey notes, “counting among their close friends novelists such as George Meredith, Thomas Hardy, and Henry James. Woolf’s great-aunt Julia Margaret Cameron was a pioneering photographer who made portraits of the poets Alfred Tennyson and Robert Browning, of the naturalist Charles Darwin, and of the philosopher and historian Thomas Carlyle, among many others.”

Woolf also had free range over her father’s mammoth library and made the most of it. Reading was her passion—and an act, like any passion, to be engaged actively, not sampled passively. In an essay about her father, Woolf recalled his habit of reciting poetry as he walked or climbed the stairs, and the lesson she took from it seems inescapable. Early on, she learned to pair literature with vitality and movement, and that sensibility runs throughout her lively critical essays, gathered in numerous volumes, including her seminal 1925 collection, The Common Reader . The title takes its cue from Woolf’s appeal to the kind of reader who, like her, was essentially self-educated rather than a professional scholar.

In a 1931 essay, “The Love of Reading,” Woolf describes what it’s like to encounter a literary masterpiece:

The great writers thus often require us to make heroic efforts in order to read them rightly. They bend us and break us. To go from Defoe to Jane Austen, from Hardy to Peacock, from Trollope to Meredith, from Richardson to Rudyard Kipling is to be wrenched and distorted, to be thrown violently this way and that.

As Woolf saw it, reading was a mythic act, not simply a cozy fireside pastime. John Sparrow, reviewing Woolf’s work in the Spectator , connected her view of reading with her broader literary life: “She writes vividly because she reads vividly.”

The Stephen family’s summers in coastal Cornwall also shaped Woolf indelibly, exposing her to the ocean as a source of literary inspiration—and creating memories she would fictionalize for her acclaimed novel, To the Lighthouse .

Darker experiences shadowed Woolf’s youth. In writings not widely known until after her death, she described being sexually abused by her older stepbrothers, George and Gerald Duckworth. Scholars have often discussed how this trauma might have complicated her mental health, which challenged her through much of her life. She had periodic nervous breakdowns, and depression ultimately claimed her life.

“Virginia was a manic-depressive, but at that time the illness had not yet been identified and so could not be treated,” notes biographer Reid. “For her, a normal mood of excitement or depression would become inexplicably magnified so that she could no longer find her sane, balanced self.”

The writing desk became her refuge. “The only way I keep afloat is by working,” Woolf confessed. “Directly I stop working I feel that I am sinking down, down.”

Woolf’s mother died in 1895, and her father died in 1904. After her father’s death, Virginia and the other Stephen siblings, now grown, moved to London’s Bloomsbury neighborhood. “It was a district of London,” noted Nicolson, “that in spite of the elegance of its Georgian squares was considered . . . to be faintly decadent, the resort of raffish divorcées and indolent students, loose in its morals and behavior.”

Bloomsbury’s bohemian sensibility suited Woolf, who joined with other intellectuals in her newfound community to form the Bloomsbury Group, an informal social circle that included Woolf’s sister Vanessa, an artist; Vanessa’s husband, the art critic Clive Bell; artist Roger Fry; economist John Maynard Keynes; and writers Lytton Strachey and E. M. Forster. Through Bloomsbury, Virginia also met writer Leonard Woolf, and they married in 1912.

The Bloomsbury Group had no clear philosophy, although its members shared an enthusiasm for leftish politics and a general willingness to experiment with new kinds of visual and literary art.

The Voyage Out , Woolf’s debut novel published in 1915, follows a fairly conventional form, but its plot—a female protagonist exploring her inner life through an epic voyage—suggested that what women saw and felt and heard and experienced was worthy of fiction, independent of their connection to men. In a series of lectures published in 1929 as A Room of One’s Own , Woolf pointed to the special challenges that women faced in finding the basic necessities for writing—a small income and a quiet place to think. A Room of One’s Own is a formative feminist document, but critic Robert Kanigel argues that men are cheating themselves if they don’t embrace the book, too. “Woolf’s is not a Spartan, clippity-clop style such as the one Ernest Hemingway was perfecting in Paris at about the same time,” Kanigel observes. “This is leisurely, ruminative, with long paragraphs that march up and down the page, long trains of thought, and rich digressions almost hypnotic in their effect. And once trapped within the sweet, sticky filament of her web of words, one is left with no wish whatever to be set free.”

During the Woolfs’ marriage, Virginia had flirtations with women and an affair with Sackville-West, a fellow author in her social circle. Even so, Leonard and Virginia remained close, buying a small printing press and starting a publishing house, Hogarth Press, in 1917. Leonard thought it might be a soothing diversion for Virginia—perhaps the first and only case of anyone entering book publishing to advance their sanity.

If Virginia Woolf had never published a single word of her own, her role in Hogarth would have secured her a place in literary history. Thanks to the Woolfs’ tiny press, the world got its first look at the early work of Katherine Mansfield, T. S. Eliot, and Forster. The press also published Virginia’s work, of course, including novels of increasingly daring scope. In To the Lighthouse , a family summers along the coast, the lighthouse on the horizon suggesting an assuringly fixed universe. But, as the novel unfolds over a decade, we see the subtle working of time and how it shapes the perceptions of various characters.

A young Eudora Welty picked up To the Lighthouse and found her own world changed. “Blessed with luck and innocence, I fell upon the novel that once and forever opened the door of imaginative fiction for me, and read it cold, in all its wonder and magnitude,” Welty recalled.

The Woolfs divided their time between London, a city that Virginia loved and often wrote about, and Monk’s House, a modest country home in Sussex the couple was able to buy as Virginia’s career bloomed. Even as she welcomed literary experiment, Woolf grew wistful about the future of the traditional letter, which she saw being eclipsed by the speed of news-gathering and the telephone. Almost as if to disprove her own point, Woolf wrote as many as six letters a day.

“Virginia Woolf was a compulsive letter writer,” said English critic V. S. Pritchett. “She did not much care for the solitude she needed but lived for news, gossip, and the expectancy of talk.”

Her letters, published in several volumes, shimmer with brilliant detail. In a letter written during World War II, for example, Woolf interrupts her message to Benedict Nicolson to go outside and watch the German bombers flying over her house. “The raiders began emitting long trails of smoke,” she reports. “I wondered if a bomb was going to fall on top of me. . . . Then I dipped into your letter again.”

The war proved too much for her. Distraught by its destruction, sensing another nervous breakdown, and worried about the burden it would impose on Leonard, Virginia stuffed her pockets with stones and drowned herself in the River Ouse near Monk’s House on March 28, 1941.

But Cunningham says it would be a mistake to define Woolf by her death. “She did, of course, have her darker interludes,” he concedes. “But when not sunk in her periodic depressions, [she] was the person one most hoped would come to the party; the one who could speak amusingly on just about any subject; the one who glittered and charmed; who was interested in what other people had to say (though not, I admit, always encouraging about their opinions); who loved the idea of the future and all the wonders it might bring.”

Her influence on subsequent generations of writers has been deep. You can see flashes of her vivid sensitivity in the work of Annie Dillard, a bit of her wry critical eye in the recent essays of Rebecca Solnit. Novelist and essayist Daphne Merkin says that despite her edges, Woolf should be remembered as “luminous and tender and generous, the person you would most like to see coming down the path.” Woolf’s legacy marks Merkin’s work, too, although there’s never been anyone else quite like Virginia Woolf.

“The world of the arts was her native territory; she ranged freely under her own sky, speaking her mother tongue fearlessly,” novelist Katherine Anne Porter said of Woolf. “She was at home in that place as much as anyone ever was.”

Danny Heitman is the editor of Phi Kappa Phi’s Forum magazine and a columnist for the Advocate newspaper in Louisiana. He writes frequently about arts and culture for national publications, including the Wall Street Journal and the Christian Science Monitor.

Funding information

NEH has funded numerous projects related to Virginia Woolf, including four separate r esearch fellowships since 1995 and three education seminars for schoolteachers on Woolf’s major novels. In 2010, Loyola University in Chicago, Illinois, received $175,000 to support WoolfOnline , which documents the biographical, textual, and publication history of To the Lighthouse.

SUBSCRIBE FOR HUMANITIES MAGAZINE PRINT EDITION Browse all issues Sign up for HUMANITIES Magazine newsletter

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming