- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 21 May 2021

Blood pattern analysis—a review and new findings

- Prashant Singh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1340-1789 1 ,

- Nandini Gupta 1 &

- Ravi Rathi 2

Egyptian Journal of Forensic Sciences volume 11 , Article number: 9 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

24k Accesses

2 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Blood is one of the most common pieces of evidence encountered at the crime scene. Due to the viscous nature of blood, unique bloodstain patterns are formed which when studied can reveal what might have happened at the scene of the crime. Blood pattern analysis (BPA), i.e., the study of shape, size, and nature of bloodstain. The focus of this paper is to understand blood and BPA. An experimental finding to understand blood stain formation using Awlata dye was conducted within the university premises under laboratory conditions. Awlata ( Alta ), an Indian dye used for grooming of women, was used to create fake blood stains to understand the formation of bloodstains with respect to varying heights, and their relation with spines and satellite stains was determined.

When the height of dropping fake blood increased, the distance of satellite stains emerging from the fake blood stains was also increasing. From the experimental finding, it was found that satellite stains were directly proportional to height of blood stain and spines were inversely proportional.

It can be concluded that blood is a vital source of information and when interpreted correctly it can be used as a source of information that can aid in investigations. Thus, a relation between formation of blood stains with relation to height was established. This finding using fake blood stains can help in carrying out future studies.

The study aims to determine the relationship between spines and satellites stains in accordance with varying heights using Awlata dye. It involves creation of fake bloodstains using Awlata dye to determine this relation. The study also seeks to suggest the use of Awlata dye for studying bloodstains for conducting future studies.

Blood is an organic fluid circulating in our body that is essential to maintain life; it includes blood cells and plasma that accounts for approximately 8% of body weight. Blood ranges from 4–5 L (female) to 5–6 L (male). Blood has few bodily capabilities which can be required for its morphological interpretation like specific weight, viscosity, and surface tension (Peschel et al. 2011 ; Bevel and Gardner 2012 ). Viscosity in terms of blood may be described as the pressure of the flow of blood, due to shear stress or extensional stress inside the body (Bevel and Gardner 2012 ). An elastic-like property of a fluid due to cohesive forces between liquid molecules is surface tension (Larkin et al. 2012 ). Blood possesses fluid nature inside the body or when it exits from the body due to an impact/injury (James et al. 2005 ). If there were blood clots in the blood found at the crime scene, it suggests that the victim was exposed to an extended injury (Peschel et al. 2011 ; Bevel and Gardner 2012 ).

Blood can exit from the body as drip, spurt, etc., or can even ooze from wounds depending on the type of infliction/damage. BPA is a type of examination that includes the interpretation of shapes of the bloodstains (James et al. 2005 ). Blood pattern analysis aims to reveal the physical events that might have occurred at the crime scene. These bloodstains can be interpreted by their shape, size, and distribution (Brodbeck 2012 ). The facts acquired from BPA can help in crime scene reconstruction, corroborating witness statements, for the investigative procedure (James et al. 2005 ). If bloodstains at a crime scene are either dried or removed by the assailant, they can still be recovered by spraying luminol. Luminol (5-amino-2,3 dihydro-1,4-pthalazine-dione) can be used to detect the presence of minor, unnoticed, or hidden bloodstains diluted down to a level of 1:10 6 (1 μL of blood in 1 L of solution) which gives chemiluminescence or glowing effect when it reacts with dried bloodstains (Quickenden and Creamer 2001 ).

Luminol solution is usually directly sprayed in completely dark environments, and then UV (ultra violet) light visualizes the sample (blood). The fluorescence obtained is then photographed or filmed. Luminol can be used to identify minor, unnoticed, or hidden bloodstains, and it also has a high sensitivity to old blood or completely dried blood but, unfortunately, luminol can react with detergents, metals, and vegetables to give false-positive results (Barni et al. 2007 ). Sometimes, there are probabilities that the bloodstain recovered had been created using certain substances (dyes/stains) to deceive the investigators. To distinguish whether a sample is blood or not, assays like Kastle-Meyer (phenolphthalein test), Medinger reaction (Leuco malachite Green), and Tetramethylbenzidine test are used, but they cannot satisfactorily confirm blood (preliminary tests). So, for the confirmatory evaluation of blood, Teichmann and Takayama tests are performed to distinguish if the samples were blood or not (Saferstein and Hall 2020 ). It is also very important for the analyst to determine the origin of species of blood (whether human or animal) by precipitin test; this is often necessary to avoid confusion in investigative findings. There are several conditions in which the bloodstain patterns are disturbed/altered and in such cases, no useful information can be interpreted. So, DNA analysis is utilized for providing investigative leads (Saferstein and Hall 2020 ). When the bloodstains are suspected to be from multiple sources, the investigator can often rely on DNA to reveal valuable details about the crime. So, in the case of multiple victims, analysts often use DNA profiling to determine whose blood it was (James et al. 2005 ; Karger et al. 2008 ).

Bloodstain patterns distributed at the crime scene can be used for the reconstruction of an event (Comiskey et al. 2016 ). Before reconstruction, an analyst must have a comprehensive view of the overall picture and use the step-by-step approach to differentiate and analyze the bloodstain patterns and search for the informative points (James et al. 2005 ). It is also required that the investigator must create a hypothesis on the formation of blood patterns due to injuries. Reconstruction can be further improved by the contribution of case descriptions and statements (witnesses/perpetrators) that can provide insights on the sequence of events. Hence, to carry out an effective reconstruction, both casework experience combined with knowledge of injuries should be known (Karger et al. 2008 ; Kunz et al. 2013 ; Kunz et al. 2015 ).

Types of bloodstains

Passive patterns.

It is a type of bloodstain pattern formed due to gravity, patterns like drip stain, flow stain, blood pool, and serum stain are observed. A drip stain is a drop falling without any disturbance that can take a spherical shape without disintegrating into smaller droplets. Bloodstains, depending on the angle, can cause the blood drop to have a circular or slightly elongated shape; this helps in the determination of the angle of impact (Swgstain 2009 ). Sometimes, a trail can be formed due to the dripping of blood from a weapon as well as in case of blunt or trauma injuries, due to which large volume of blood can be encountered at the crime scene (James et al. 2005 ; Peschel et al. 2011 ).

Spatter patterns

These are patterns formed when hard objects are used to strike the victim (example: a pipe). Forward spatter on the other hand is a pattern formed towards the direction of damage (example: bullet creating an exit wound) (James et al. 2005 ; Peschel et al. 2011 ). Back spatter is a pattern formed by blood when damage is to a hard surface like the skull by a bullet, and the bloodstains will be pointing away from the impact. Gunfire spatter can also vary on the caliber of the weapon used, location of impact, and the location of the victim (James et al. 2005 ; Peschel et al. 2011 ).

Projected patterns are irregular patterns that are due to the motion of weapon (example: stabbing). If in case at the crime scene there was existence of droplets of blood of varied sizes, it is called a cast-off pattern (example: injuries by hammers) (James et al. 2005 ). In case of injury to the artery, the blood from the blood vessel flows like a fountain (upward to downward flow), a zig-zag pattern will be observed until the pressure of the lungs reduces. If there was injury internally, expiration from the mouth/nose releases blood that creates a pattern very small to see (fine mist-like) (James et al. 2005 ; Peschel et al. 2011 ).

Altered patterns

Bloodstain patterns that indicate that a physical change had occurred can be said as altered patterns. This change can be due to physical activity, diffusion, dilution, or insects’, which can misguide the investigators to consider them as drip patterns. In case if the body was dragged over pre-existing blood, it leaves a tangential path (James et al. 2005 ). Contact prints may also be recovered on clean surfaces at the crime scenes (bloody shoe prints, fingerprints, or the entire palm) that can help investigators in determining what might have occurred at the crime scene. This can help investigators to determine what object could have been at the crime scene (James et al. 2005 ; Peschel et al. 2011 ).

Void patterns on the other hands are formed when an object is placed between the blood source and projection area, it is likely to receive some of the stains, which consequently leads to an absence of the stains in an otherwise continuous bloodstain pattern, which can indicate that an object or person would have been a part of the pattern (like a missing object from the wall) that if recovered can help in completing the pattern (James et al. 2005 ; Peschel et al. 2011 ).

Insects that move over the blood can also create a unique pattern that can often confuse the investigators to what pattern it could be. When blood comes into contact with clothing and fabric it spreads via diffusion, often leaving an irregularly shaped pattern which is difficult to interpret, especially in that cases the surface could be collected and send for examination to forensic labs (James et al. 2005 ; Peschel et al. 2011 ).

Moreover, to reconstruct the events that caused bloodshed, the investigators use the direction and angle of the spatter to calculate the areas of convergence (it is the starting point of the bloodshed) and area of origin (point from where the blood immerged) to mark the location of the victim and perpetrator (James et al. 2005 ) (Fig. 1 ).

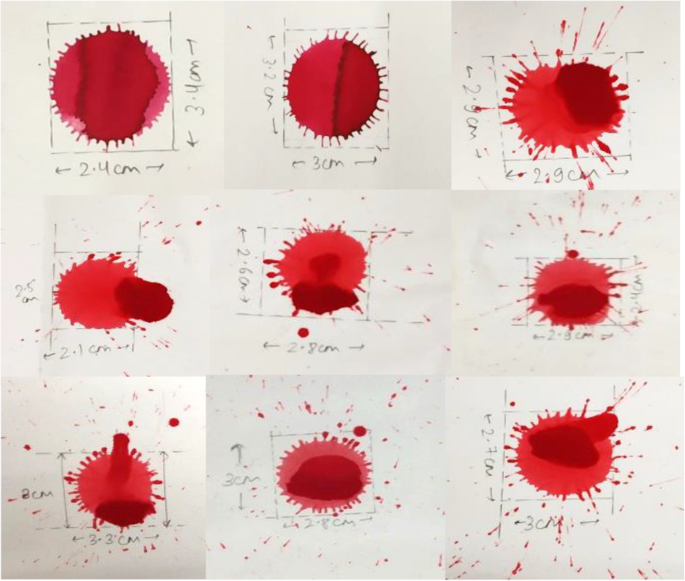

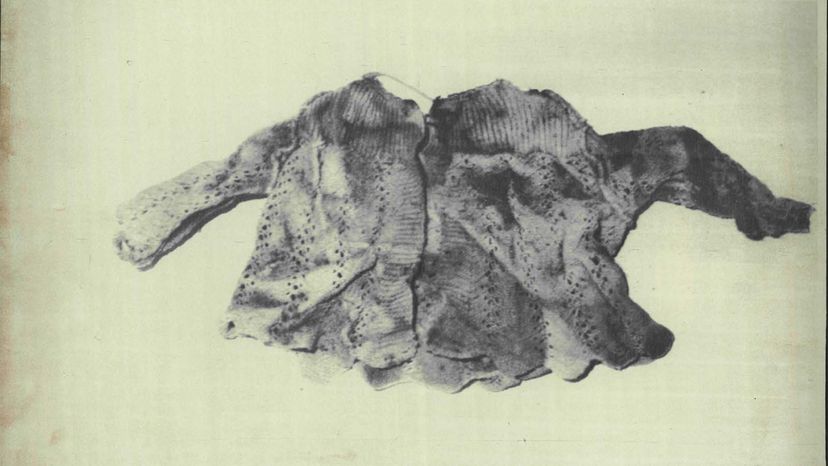

Fake blood stains that were made using Awlata dye

Different works have been carried in blood pattern analysis, a study showed that when determining area of origin from blood stains, larger drops which are elliptical should be given more consideration (de Bruin et al. 2011 ). In another study, the velocities of blood were considered with factors like air drag and gravity which was used to predict the back-spatter formation by carrying the experiment using a blood-soaked sponge (Comiskey et al. 2016 ).

Fluid dynamics was also given consideration in blood pattern analysis to understand how the blood behaves as a liquid when in air and the factors that are affecting the formation the blood drop (Attinger et al. 2013 ). Study of spines and satellite on basis of velocity has also depicted the formation of bloodstains (Attinger et al. 2013 ).

In a real-time setting, studying bloodstains and its patterns using real blood can be a tedious task, as it requires a large amount of blood. Moreover, in order to carry out such a study, it will require ethical clearance as well as financial support. Using Awlata dye for studying bloodstains can solve these problems because of its easy availability, low cost, and it can be made under laboratory conditions. Thus, investigators and scientists can use this for experimental purposes and to carry future studies.

Article selection criteria for review

The initial criteria for selecting literature were based on searching different keywords on Google searching engine for blood, blood pattern analysis, and blood pattern analysis in forensic science. Then, after screening of articles based on the title and abstract of papers, papers were sorted. Articles and relevant internet sources that matched the relevant criteria of the review were also selected.

Article eligibility criteria for review

Eligibility of articles was finalized by analyzing whether the papers were discussing about BPA and its related methodology or not.

On basis of analyzing existing literature, it was decided that a study needs to be conducted by creating fake bloodstains using Awlata, so as to understand the formation of stains if the angle is kept fixed and the height is varied (Buck et al. 2011 ; Attinger et al. 2013 ). An Indian dye (Awlata/Alta) was used to make fake blood stains to depict similar patterns as that of blood. Awlata (Alta) is a traditional Indian red dye used by women in the festive season and is applied to hands and feet. For the experiment Awlata dye, a Pasteur pipette and white chart papers were used. The experiment was carried within the university premises in the university laboratory.

Preparation/composition of Awlata

In cultural practices, Awlata dye was made from Betel leaves which is a vine from the family Piperaceae. Awlata is also made from the extract of lac that is a red dye obtained from the scale of an insect Laccifer Lacca. Nowadays, Awlata can be made chemically by using Vermillion (red powder) with water to make a liquid.

Source of Awlata for the experiment

For this experiment, a ready-made Awlata dye (Pari) was bought from the local market which had its composition defined and came packed in a 50-ml bottle. The reason for taking Awlata for experiment, was Awlata dries within a few minutes and its life span is about 1–2 months, after which it starts to fade. But if it is preserved and stored properly, it can stay intact for long durations.

Formation of fake bloodstains

In this experiment, we conducted different height variations to create fake bloodstains using Awlata dye (Buck et al. 2011 ; Attinger et al. 2013 ). The experiment aimed to study the shape (morphology) of these fake bloodstains at different heights (3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 feet) so that an approximate estimation of actual blood stain formation can be studied (Attinger et al. 2013 ). A Pasteur pipette was used for this experiment and about 0.5 ml of Awlata dye was taken for making a single fake blood stain.

The amount of Awlata dye that was used to make a single fake blood stain was ascertained using the indications labeled on the Pasteur pipette. Ninety-degree angle was maintained and the Awlata dye was dropped from different heights and observations were made. For each height, two stains were made and labeled drop 1 and drop 2; this was done to compare the observation and confirm the findings.

After Awlata dye was dropped from different heights to create fake blood stains, it was observed that as the height was increased, the distance of satellite stains emerging from the fake blood stains was also increasing. It can be observed that fake blood stain created from three feet has many numbers of spines and less satellite stains and they are very close to the parent stain. Similarly, as the height was increased, the numbers of spines were reduced and the number of satellite stains was increased.

The experimental observation noted was that as the height was increased, the force of gravity acting on the Awlata dye was also increasing, and hence when the Awlata dye was dropped from a height to create fake blood stains, the impact of the dye on the surface due to gravitational forces, inertial forces, and viscous forces (Attinger et al. 2013 ) could be the possible cause of formation of such stains. To ascertain the formation of these fake blood stains, we retook the height experiment and the observations were very similar to that of the first drop (see Table 1 ).

Discussions

After the experiment carried with Awlata dye, it was observed that height was directly proportional to the number of satellite stains (stains that are small droplets moving away from the parent stain, they are partially/not attached to the parent stain), i.e., more distant the satellite stains from the parent drop, more will be the height. Whereas relation of spines (these are small projections coming out from the parent stain, they remain attached to the parent stain) and height was inverse in nature, i.e., when the height was increased the number of spines reduced.

Though Awlata was used to study the formation of fake blood stains, care must be taken that this dye should be kept away from contact with moisture/water as repeated moisture/water tends to fade the dye and also wash it off. So, if Awlata dye is used for future studies, the observations made from this dye should be properly stored and preserved. This will help ensure the integrity of experimental findings is not altered.

Factors like size, age, and health of the individual should also be given consideration while studying the blood stain formation. Moreover, surface tension also plays an important role in the formation of bloodstains (Larkin et al. 2012 ). Surface tension is also varied if there is some chemical or other chemical present in the blood (Raymond et al. 1996 ). The surface roughness, permeability, and porosity also effect the formation of bloodstain formation. So, these factors are also needed to be given consideration when studying bloodstains (Bear 1975 ).

Study of fake bloodstains using Awlata dye highlights these potential aspects and on basis of existing literary works carried by other scientists a more definite version of BPA can be worked upon. Study of fluid dynamics should also be given consideration while studying bloodstain formation (Attinger et al. 2013 ). To open new gateways of research in BPA and support investigative observations, the findings depicted in this paper can be used as a source to validate actual blood stains and also carry out future studies. Domains like how angle variation with respect to height effects formation of blood stains can be explored on the basis of these findings. This finding can help to understand the formation of blood stains for future research and development.

The future of BPA is promising and more research needs to be done to improve BPA. A more precise method of blood interpretations should be created to make investigations more accurate, so that crime scene reconstruction can be carried out efficiently. The study conducted using Awlata dye can be a contributor to the existing literature on BPA. This paper is a review work which can be utilized by students, scientists, or experts as a reference for carrying out future studies or to enhance their knowledge. Blood pattern analysis is indeed a useful tool in forensic science which can help in crime scene reconstruction and if BPA is coupled with DNA analysis and other investigative findings, more conclusive and thorough details of the sequence of events can be obtained from blood evidence.

Limitations of Awlata dye

The composition of Awlata dye (Alta) and blood vary; hence, Awlata dye (Alta) cannot be considered as blood. Awlata was used to create fake bloodstains which can give an approximate idea towards BPA and resemblance somewhat similar to actual blood stains. The actual scenario at the crime scene that led to the formation of blood stains and that made by Awlata dye has scope for human errors too as studying blood stains in real and that in experimental conditions differ.

Awlata dye use in the forensic scenario

Studying BPA is a very skillful task, and at the crime scene when real blood is concerned, the scenarios are simultaneous and unpredictable. To carry studies to understand bloodstains is not always possible; it requires a large amount of blood which is subjected to ethical clearance. Awlata dye can be an emerging substitute to this problem, as it is cost-effective, readily available, and can also be made in the lab. Awlata dye can be used to create experimental conditions to study different forensic scenarios. Fake blood created with Awlata dyes can be used to make simulated crime scenes from forensic and investigative findings to derive case supportive conclusions.

From the experiment done using Awlata dye ( Alta ), it can be concluded that blood stains can help experts estimate the approximate height of the assailant. The formation of the bloodstain can correspond to the height it originated from, thus being a vital source of information. A relation of formation of blood stains with change in varying height was established in accordance with interpretation of spines and satellite stains. Though Awlata is not similar to blood, it can be used to carry out experimental studies to explore more about BPA. Existing studies on BPA depict that blood patterns are very useful source of information and it can help investigators to examine the crime scene precisely.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

Blood pattern analysis

Deoxyribonucleic acid

Ultra violet

Attinger D, Moore C, Donaldson A, Jafari A, Stone H (2013) Fluid dynamics topics in bloodstain pattern analysis: Comparative review and research opportunities. Forensic Sci Int 231(1-3):375–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2013.04.018

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Barni F, Lewis S, Berti A, Miskelly G, Lago G (2007) Forensic application of the luminol reaction as a presumptive test for latent blood detection. Talanta 72(3):896–913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2006.12.045

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Bear J (1975) Dynamics of fluids in porous media. Soil Sci 120(2):162–163. https://doi.org/10.1097/00010694-197508000-00022

Article Google Scholar

Bevel T, Gardner R (2012) Bloodstain pattern analysis with an introduction to crime scene reconstruction, 3rd edn. Taylor and Francis, Hoboken

Google Scholar

Brodbeck S (2012) Introduction to bloodstain pattern analysis. SIAK J J Police Sci Pract 2:51–57 Avaialble via DIALOG. https://www.bmi.gv.at/104/Wissenschaft_und_Forschung/SIAK-Journal/internationalEdition/files/Brodbeck_IE_2012.pdf

Buck U, Kneubuehl B, Näther S, Albertini N, Schmidt L, Thali M (2011) 3D bloodstain pattern analysis: Ballistic reconstruction of the trajectories of blood drops and determination of the centres of origin of the bloodstains. Forensic Sci Int 206(1-3):22–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.06.010

Comiskey P, Yarin A, Kim S, Attinger D (2016) Prediction of blood back spatter from a gunshot in bloodstain pattern analysis. Phys Rev Fluids. 1(4). https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevfluids.1.043201

de Bruin K, Stoel R, Limborgh J (2011) Improving the point of origin determination in bloodstain pattern analysis. J Forensic Sci 56(6):1476–1482. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2011.01841.x

James S, Kish P, Sutton T (2005) Principles of bloodstain analysis. CRC, Boca Raton, Fla. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420039467

Book Google Scholar

Karger B, Rand S, Fracasso T, Pfeiffer H (2008) Bloodstain pattern analysis—casework experience. Forensic Sci Int 181(1-3):15–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2008.07.010

Kunz S, Brandtner H, Meyer H (2013) Unusual blood spatter patterns on the firearm and hand: a backspatter analysis to reconstruct the position and orientation of a firearm. Forensic Sci Int 228(1-3):e54–e57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2013.02.012

Kunz S, Brandtner H, Meyer H (2015) Characteristics of backspatter on the firearm and shooting hand-an experimental analysis of close-range gunshots. J Forensic Sci 60(1):166–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.12572

Larkin B, El-Sayed M, Brownson D, Banks C (2012) Crime scene investigation III: exploring the effects of drugs of abuse and neurotransmitters on bloodstain pattern analysis. Anal Methods 4(3):721. https://doi.org/10.1039/c2ay05762j

Article CAS Google Scholar

Peschel O, Kunz S, Rothschild M, Mützel E (2011) Blood stain pattern analysis. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 7(3):257–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12024-010-9198-1

Quickenden T, Creamer J (2001) A study of common interferences with the forensic luminol test for blood. Luminescence 16(4):295–298. https://doi.org/10.1002/bio.657

Raymond M, Smith E, Liesegang J (1996) The physical properties of blood–forensic considerations. Sci Justice 36(3):153–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1355-0306(96)72590-x

Saferstein R, Hall A (2020) Forensic science handbook. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Milton. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315119939

Swgstain S (2009) Scientific Working Group on bloodstain pattern analysis: recommended terminology. Forensic Sci Commun 11(2):14–17 Available via DIALOG. http://theiai.org/docs/SWGSTAIN_Terminology.pdf

Download references

Acknowledgements

Author information, authors and affiliations.

School of Forensic Science, National Forensic Sciences University, Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India

Prashant Singh & Nandini Gupta

Department of Chemistry, Biochemistry and Forensic Sciences, Amity University, Manesar, Haryana, India

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

PS and NG worked on researching relevant data and writing of this review paper. RR was our guide and mentor who constantly guided us and helped formulate the different sections of the review and did the final check. We clarify that all authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Prashant Singh .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Singh, P., Gupta, N. & Rathi, R. Blood pattern analysis—a review and new findings. Egypt J Forensic Sci 11 , 9 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41935-021-00224-8

Download citation

Received : 28 September 2020

Accepted : 09 May 2021

Published : 21 May 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s41935-021-00224-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Bloodstains

Bloodstain Pattern Analysis: The Case of David Camm

By: Bill Clutter

The first use of blood stain analysis in an American courtroom occurred in 1966, in the re-trial of Sam Sheppard, an Ohio physician who spent over 10 years in prison before being freed. Sheppard had been convicted in 1954 of bludgeoning his wife to death in her bed, but maintained his innocence, claiming the attack was perpetrated by an intruder. This famous case inspired the TV series The Fugitive (1963-67) and the 1993 movie, starring Harrison Ford. The U.S. Supreme Court vacated the original conviction because of pre-trial publicity that made it impossible to receive a fair trial. F. Lee Bailey, gained fame as a criminal defense lawyer by winning an acquittal on re-trial. Dr. Paul Kirk, a criminologist at the University of California, Berkley, conducted a reconstruction of the crime scene and provided the first expert testimony interpreting for the jury patterns of cast-off and impact spatter bloodstains that were present at the crime scene. His testimony helped win Sheppard’s freedom. However, it was Herbert L. MacDonell, who is credited with establishing the profession of Bloodstain Pattern Analysis (BPA). In 1971, MacDonell wrote Flight Characteristics and Stain Patterns of Human Blood , the first authoritative BPA training manual. In 1983, he organized a meeting of his disciples whom he trained in Corning, NY and organized the International Association of Bloodstain Pattern Analysts (IABPA). To acquire a better understanding of this specialty, I attended a bloodstain pattern analysis course sponsored by Bevel Gardner & Associates.

THE CAMM CASE: “A BLACK-EYE” TO THE BPA PROFESSION After giving an overview of BPA history, the instructor mentioned that the bloodstain profession has taken a few hits with the 2009 report from the National Academy of Sciences that was critical of some of the practices of BPA in American courtrooms. He noted that one case in particular, the David Camm case in Indiana, has given the profession “a black eye”. I had watched the CBS 48 Hours story on the Camm case several years earlier, so I was aware that former Indiana State Trooper, David Camm’s alibi had been corroborated by eleven men. He had been playing basketball at a church where his uncle was the pastor. The game started around 7 p.m., about the same time that his wife and two children were last seen alive. The men played basketball for about two hours and David was there the entire time, according to those who played ball with him. At approximately 9:26 p.m. he arrived home and called his old post at the Indiana State Police after finding the bodies of his wife and two children in the garage of their home in Georgetown, Indiana.

David told police he found his wife lying on the floor of the garage. She had a single bullet wound to the head. He found his five-year-old daughter, Jill, in her seat belt in the back seat of his wife’s Ford Bronco inside the garage. Jill had been shot once in the head. His son Brad was slumped over the back seat as if he had attempted to escape to the back cargo area when he was shot. David said his son’s body felt warm, possibly still alive. David climbed into the back seat, carried his son out of the vehicle and laid him next to his mother so he could perform CPR. Brad died from the single gun-shot wound that entered just under his arm pit. At autopsy, the pathologist found possible evidence of a possible “sexual assault” in Jill’s vaginal area which immediately changed the dynamics of the homicide investigation. The demeanor of the questioning toward David became accusatory. However, a week earlier, the child’s pediatrician had noticed the same inflammation, but attributed it to aggressive wiping or possibly a reaction to bubble baths. A mandatory reporter, the family doctor was not alarmed. No report of child abuse had been made at that time.

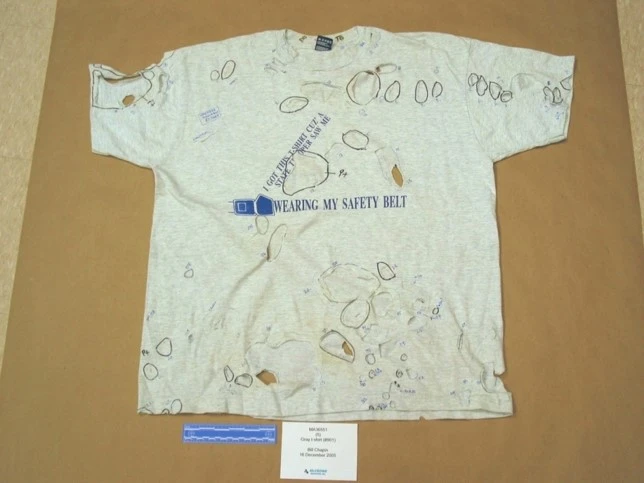

Prosecutors decided to call in a bloodstain pattern “expert” who had a reputation for assisting in the prosecution of cases that were difficult to prove. Two days later, David Camm was arrested for first degree murder, based on an interpretation of eight tiny bloodstains on his t-shirt. The “expert” who had been called to the crime scene interpreted these stains as high velocity impact spatter from allegedly firing the gun that killed his family. Some of the leading experts in BPA, however, disagreed, and said the stains were caused by transfer from coming into contact with his 5 year-old daughter’s hair that was saturated with her blood when he removed his son from the vehicle.

Robert Stites was the so-called “expert” in crime scene reconstruction and bloodstain pattern analysis who arrived in New Albany, Indiana to assist Floyd County prosecutor Stan Faith. Stites, however, was merely a crime scene photographer who was working at the direction of Rodney Englert. The real “expert” was Englert, who was a Charter Member of the International Association of Bloodstain Pattern Analysts (IABPA). Englert was not able to travel to the crime scene, so he sent his photographer. Police were unaware at the time that Stites was unqualified to render opinions about blood-stain analysis, but he did. Prior to traveling to Indiana, Stites had never taken any courses on bloodstain analysis or crime scene reconstruction, and was not a member of any blood stain analysis organization. The Indiana State Police evidence technician, who was initially in charge of processing the crime scene, had strong reservations about the so-called “expertise” of Robert Stites. After watching Stites the seasoned CSI realized that Stites didn’t know what he was doing.

The CSI came to this realization after Stites claimed there was evidence of clean-up at the crime scene. He said there had been a clear watery substance added to the large volume of blood that flowed downward to the edge of the garage away from the wife’s head wound. It turns out that it was serum separation, which helped provide a timeline as to when the murders happened. A defense bloodstain expert calculated that it would have taken about two hours for the serum to separate, placing the time of death at around 7:30 p.m. Stites arrived at the crime scene on Sept. 30, 2000. On the following day, David was arrested based on Stite’s opinion that high velocity impact spatter was present on David’s gray t-shirt known as Area 30. The police officer who served the arrest warrant, had reservations about arresting David based on the opinions of Stites. The affidavit that prosecutors drafted that provided probable cause to arrest Camm relied entirely on the opinions of Stites. Stites observed eight small blood stains on the front left side of David’s t-shirt that were less than one millimeter in diameter. The size of stains, he said, meant this had to have been high velocity impact spatter from being in close proximity to a fired gun. Backspatter and forward spatter from a bullet penetrating a blood source at high velocity can project a fine mist pattern of blood stains; backward as the bullet penetrates the object and forward as the bullet exits. Blood stains from high velocity impact spatter typically are less than a millimeter in diameter, as is found on David’s t-shirt. However, as I learned from my BPA training, “Both expectorate blood [aspirated from the mouth] and flies produce patterns that an analyst can misidentify as impact spatter”, according to Tom Bevel’s book Bloodstain Pattern Analysis: with an Introduction to Crime Scene Analysis. Bevel cautions that it is, therefore, important for the analyst to consider the full context of the crime scene.

EXPERTS FOR THE DEFENSE Blood stain experts Bart Epstein, Terry Laber, Stuart James, and Paul Kish, some of the most respected bloodstain experts in the country testified for the defense. They expressed their professional opinions that the small spots of blood on David’s t-shirt were transfer stains caused by the t-shirt coming into contact with blood saturated strands of his daughter’s hair. However, none of the State’s bloodstain experts reported observing high velocity impact spatter stains on David’s shorts. The absence of spatter stains on David’s pants adds strength to the conclusion that the stains on Area 30 were caused by transfer from the shirt coming into contact with his daughter’s blood soaked strands of hair. The linear pattern of the stains is also not consistent with high velocity impact spatter. One would expect to see a conical pattern of dispersal from high velocity impact spatter (both forward and back spatter) when a bullet fired from a gun impacts a body of blood. However, the bloodstains on Area 30 form a straight line, a pattern that is more consistent with a transfer of blood from strands of hair from a head wound.

MISUSE OF BPA IN AMERICAN COURTROOMS My first case involving Rodney Englert, was a Lawrenceville, IL woman who was facing the death penalty. In June of 2000, I received a phone call from Katharine Liell, a criminal defense attorney from Bloomington, IN. Ironically; she would later represent David Camm. Her client, Julie Rea, was a Ph. D. student at Indiana University. It was a cold-case. Three years had gone by since the murder of Julie’s son, 10 year-old Joel Kirkpatrick. On Oct. 13, 1997, at 4 a.m., Julie was awakened by her son’s screams for help. When she went into his room, she startled an intruder. He had just stabbed her son to death with a knife that came from her kitchen. The elected state’s attorney resisted pressure from the sheriff and her ex-husband to place her under arrest. The prosecutor made a public statement that there was not enough evidence to arrest anyone. After he left office, a special prosecutor intent on charging Julie Rea with a capital offense was appointed to take charge of the investigation. The special prosecutor hired Rodney Englert.

Englert was able to see evidence of cast off bloodstains in his interpretation of the night-shirt Julie was wearing when she encountered the intruder. Englert opined that the cast-off stains were allegedly caused when the mother drew back the knife after repeatedly stabbing her son to death. Bloodstain interpretations previously made by forensic scientists from the Illinois State Police could only find transfer patterns consistent with the mother’s story about colliding into an intruder and struggling with the man. She had a black eye where the man had punched her in the face, and she had a gash on her arm that required sutures. I told Julie’s attorney that if I was appointed to her client’s case, I would want to investigate whether Tommy Lynn Sells had been in the area at the time of the murder. A child serial killer, Sells had just been arrested in Del Rio, TX, for a similar crime in which he broke into a trailer at 4 a.m and used a knife from the kitchen to kill Kaylene Harris while her mother slept. However, prosecutors decided not to seek the death penalty in a maneuver to avoid reforms that would have leveled the playing field by providing Julie’s defense with financial resources to investigate her innocence prior to trial. After Julie was convicted in March of 2002, Diane Fanning published Through the Window: The Terrifying True Story of Cross-Country Killer Tommy Lynn Sells. Sells had told Fanning about a murder in Illinois in which he had killed a child and was startled by the mother who came into the room. He said he would have killed her too, if he hadn’t dropped the knife. Crime scene investigators found the bloody knife on the floor at the doorway, where Julie said she encountered the man.

I was able to corroborate the confession with witnesses who reported to their sheriff an intruder who matched Sell’s physical description. Based on this evidence, Texas Ranger John Allen provided an affidavit supporting Julie’s petition seeking to overturn her conviction. However, after her conviction was overturned the same prosecutors and police investigators who got it wrong dug in their heels and decided to disbelieve the confession before consulting with Texas law enforcement authorities. They re-arrested Julie just as she was about to be released from prison and set her case for re-trial. A new jury, hearing the evidence of the serial killer’s confession found her not guilty in 2006. She was represented by the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University Law School pro bono. She subsequently received a Certificate of Innocence.

On June 2, 2003, a year after Englert’s testimony was used to persuade juries to convict David Camm and Julie Rea, an ethics complaint against Englert was filed with the American Academy of Forensic Science by some of the most respected bloodstain experts in the country alleging that Englert had misrepresented his education, training and experience. Subsequent to this, Englert filed suit against Herb MacDonell (regarded as the father of the BPA profession) alleging slander for calling Englert among other things “a forensic whore”, “liar-for-hire”, “a very smooth charlatan”, and “the Bin Laden of bloodstains”. In 2009, the National Academy of Sciences released a critique of forensic science practices in U.S. courtrooms, noting that since the introduction of DNA testing in 1989 that “faulty science” was found to be responsible for the wrongful convictions of a number of post-conviction DNA exonerations. BPA was one of several disciplines that were faulted because of the interjection of “examiner bias” that may lead to erroneous conclusions when interpreting evidence like bite marks, tool marks and bloodstains. The report noted “many sources of variability arise with the production of bloodstain patterns, and their interpretation is not nearly as straightforward as the process implies”. The report found, “some experts extrapolate far beyond what can be supported”, and went on to conclude that “extra care must be given to the way in which the analyses are presented in court. The uncertainties associated with bloodstain pattern analysis are enormous”.

DNA IDENTIFIES CHARLES BONEY Four years after David Camm was arrested, his conviction was reversed in Aug. 2004, because prosecutors had unfairly inflamed the jury by introducing testimony about his extramarital affairs. Some of his affairs were with women with whom he worked at the Indiana State Police Sellersburg Post, which had taken charge of the homicide investigation. A new team of investigators were called into the case to be “fresh eyes”. They discovered from their review of the file that there had been a grey sweatshirt that was foreign to the crime scene. The sweatshirt was found underneath Brad Camm’s body, where his father laid his son next to his wife. The inside collar had the moniker “BACK-BONE” written in black ink. At the very beginning of the investigation the collar had been swabbed by a forensic scientist to identify the wearer’s DNA. An unknown male DNA profile was identified. Prior to David’s first trial his defense attorney asked the prosecutor, Stan Faith, (who had charged David) whether this DNA profile had been entered into CODIS, the FBI offender DNA database. The prosecutor told the defense attorney that it was submitted, but there was no hit. This was a false representation, which obstructed justice for David Camm.

Years later, after an appellate court reversed David’s conviction, Camm’s new attorney, Katherine Liell, requested that the DNA be entered into CODIS. In Feb. 2005, a CODIS hit came back identifying a career criminal named Charles Darnell Boney whose prison nickname was BACK-BONE. He had been released from prison a few months before the Camm family was killed. Known as the “Shoe Bandit”, Boney had a foot fetish and was sexually aroused by holding women at gunpoint and stealing their shoes. One of the female troopers who arrived at the crime scene had noted in her report that it was odd that the shoes of David’s wife had been removed from her feet and were placed on top of the vehicle.

Now, it all made sense. Although his wife’s shoes and pants had been removed, there was no evidence of a sexual assault in the conventional sense. So investigators dismissed the idea that the crime was motivated by the behavior of a sexual predator. But knowing Boney’s sexual predilection of being aroused by women’s bare feet and legs, the artifacts of the crime scene fit perfectly with his MO.

THE PROSECUTION COMPLEX Chicago Sun Times reporter Tom Frisbie described the “Prosecution Complex” in his book Victims of Justice , about the infamous Nicarico case. Instead of seeking justice when new and exonerating evidence was found proving the innocence of Rolando Cruz, which included DNA and confession of a serial killer, the police and prosecutors who got it wrong tend to circle the wagons to fend off the attack on the original conviction. In that case, police and prosecutors were eventually indicted for a conspiracy to obstruct justice. Less than a month after DNA identified Charles Boney, his palm print was found on the door frame of the passenger side of David’s wife’s Ford Bronco. This palm print is consistent with Boney having reached inside the vehicle to fire the shots that killed 7 year-old Brad, and his 5 year-old sister, Jill, who was still seat belted inside the vehicle. Earlier, a judge had lowered David’s bond. He was released to what remained of his family. His uncle, Sam Lockhart, who had been playing basketball that night with David, bonded him out of jail. But now Boney was given a choice. He could be charged with the death penalty, or he could cooperate and assist prosecutors with their theory that Boney provided the gun to David Camm that he allegedly used to kill his family. Boney initially denied knowing David when he was interviewed in February. A month later, with this new and compelling evidence of his palm print, Boney’s life depended on which choice he made. Despite his previous series of proven lies, Boney changed his story, and now said he met David playing basketball and after this first meeting arranged to sell him a gun that he wrapped in his sweatshirt. However, this does not explain why David’s wife’s DNA is on the left sleeve of the sweatshirt. The autopsy revealed that David’s wife had struggled with the assailant and had injuries suggesting she had been choked.

Nevertheless, David was re-indicted for conspiracy to commit murder and has been confined to a prison cell ever since. Although Boney was convicted of conspiracy to commit murder and remains in prison, he recently said he has every expectation of being a free man someday. EXONERATING THE INNOCENT The highlight of my BPA training was the arrival of Tom Bevel. He had been on the road most of that week testifying in court. During the noon break after his presentation, he told me about his work on a case in North Carolina where he had provided testimony of his interpretation of bloodstain evidence that had helped to exonerate an innocent man On Feb. 10, 2010, he provided testimony for the North Carolina Innocence Project before an independent panel of three judges. This special commission was created by the state’s Supreme Court to establish an independent review of inmate claims of actual innocence called North Carolina Innocence Inquiry Commission, the first of its kind in the nation. Bevel’s testimony persuaded the three judges that there was clear and convincing evidence demonstrating the innocence of Greg Taylor. Taylor was granted a full pardon on May 21, 2010, and was released from prison. He had been wrongfully convicted in 1993 of first degree murder based on erroneous testimony concerning bloodstain evidence. He spent nearly two decades in prison for a crime he did not commit.

A few years before that, Bevel had also assisted with the release of Tim Masters, an innocent man who had been convicted of murder in Colorado. In that case, Bevel reversed the previous opinion he had given that originally helped to convict Masters, after he had been provided additional evidence that had been concealed from him by the police detective who was later indicted for his alleged misconduct in the case.

Some of the real heroes in cases like this are guys like Tom Bevel, who dare to reveal their humanity by admitting when they get it wrong, but are willing to work to make it right.

( On October 24, 2013, David Camm, walked free after 13-years in prison after a jury in Lebanon, Indiana found him not guilty in a third re-trial. His case was the first exoneration for Investigating Innocence , which was started earlier that year. Bill Clutter, who started the project, was a member of Camm’s defense team and suggested conducting an animated crime scene reconstruction, which helped persuade the jury that David Camm is innocent. Students at the University of Indiana assisted Clutter and the Camm defense team in reviewing the case and provided a fresh set of eyes. ( Read more about the exoneration here. ) Bill Clutter is a board certified member of the Criminal Defense Investigation Training Council. He started the Illinois Innocence Project in 2001, and is the Director of Investigations for a national innocence project called Investigating Innocence that he started in January 2013.

Share this:

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Advertisement

How Bloodstain Pattern Analysis Works

- Share Content on Facebook

- Share Content on LinkedIn

- Share Content on Flipboard

- Share Content on Reddit

- Share Content via Email

Bloodstain Pattern Analysis in Action: The Chamberlain Case

One infamous case that comes to the minds of many people when thinking about blood spatter analysis involves a line that has since become a pop culture catchphrase, thanks to Meryl Streep in "A Cry in the Dark" and Julia Louis-Dreyfus on "Seinfeld": " The dingo ate my baby. "

In August 1980, the Chamberlain family camped near Uluru (formerly known as Ayers Rock) in the Red Centre desert of Australia's Northern Territory. One night, Lindy Chamberlain put two of her children, 4-year-old Reagan and 9-week-old Azaria, to bed in their tent. When she returned, the story goes, she cried, "The dingo's got my baby!" [source: Latson ].

According to Lindy , when she got to the tent she saw a dingo with a bundle in its mouth. She wasn't close enough to see what it was, but when she checked on the children she saw that her daughter Azaria was missing [source: Haberman ]. As the cry went out, she and her husband, Michael, along with other campers, began searching for the child. A nearby camper, Sally Lowe, went into the tent to check on the still-sleeping Reagan. Seeing a pool of wet blood on the floor of the tent, she thought that Azaria was probably already dead [source: Linder ].

When a tourist found the baby's jumpsuit, it was only slightly torn and bloody, but mostly intact. Though an initial investigation backed up Lindy's claim of a wild dog attacking her daughter, it was not long before the parents themselves stood accused [source: Haberman ].

The baby had been wearing other clothes that weren't found at the time.

Throughout the case, the local police improperly handled blood spatter and other evidence. Forensics investigators found "blood stains" in the family car and concluded that Lindy had taken Azaria there to cut her throat. Later analysis revealed that the stains came from a spilled drink and a sound-deadening compound that came with the car. One expert identified a "bloody handprint" on Azaria's jumpsuit that later analysis revealed to be red desert sand.

However, in 1982, expert testimony — and public opinion — proved enough to convict Lindy Chamberlain of murder and her husband of being an accessory to murder. The baby's knit jacket, found four years later in 1986 near a dingo lair, helped exonerate the Chamberlains after Lindy had served three years of a life sentence, but several years of trials and hearings were yet to come [source: Latson ]. In 2012, 32 years after the event, a coroner finally pronounced that a dingo was responsible for Azaria's death [sources: Haberman , Latson ].

The Chamberlain case shows what can happen when people involved in handling and analyzing blood evidence lack proper training, or when investigators allow public opinion or preconceived notions to influence their analysis.

Related Articles

- 10 Terribly Bungled Crimes

- How Autopsies Work

- How Blood Works

- How Crime-scene Clean-up Works

- How Crime Scene Investigation Works

- How DNA Evidence Works

- How Fingerprinting Works

- How Lie Detectors Work

- How Luminol Works

More Great Links

- Forensic Magazine

- International Association of Bloodstain Pattern Analysts (IABPA)

- International Association for Identification (IAP)

- Akin, Louis. "Directional Analysis of Blood Spatter at Crime and Accident Scenes for the Private Investigator." The Forensic Examiner. Summer 2005. http://www.akininc.com/PDFs/Directional%20Analysis%20for%20PI's%20condensed.pdf

- Brodbeck, Silke. "Introduction to Bloodstain Pattern Analysis." SIAK-Journal — Journal for Police Science and Practice. Vol. 2. Pages 51-57. 2012. (Oct. 14, 2015) http://www.bmi.gv.at/cms/bmi_siak/4/2/1/ie2012/files/brodbeck_ie_2012.pdf

- Cotton, Fred B. "Justice Applications of Computer Animation." SEARCH Technical Bulletin. Iss. 2. 1994. (Oct. 16, 2015) http://www.search.org/files/pdf/tbanimat.pdf

- Dutelle, Aric W. "An Introduction to Crime Scene Investigation." Jones & Bartlett Publishers. Jan. 28, 2011.

- Eckert, William G. and Stuart H. James. "Interpretation of Bloodstain Evidence at Crime Scenes." CRC Press. 1999.

- Evans, Collin. "Murder 2: The Second Casebook of Forensic Detection." John Wiley & Sons. 2004.

- Forensic Science Simplified. "A Simplified Guide to Bloodstain Pattern Analysis." (Nov. 30, 2021)

- Forensic Science Simplified. "A Simplified Guide to Bloodstain Pattern Analysis." (Nov. 30, 2021)http://www.forensicsciencesimplified.org/blood/how.html

- Genge, N.E. "The Forensic Casebook: The Science of Crime Scene Investigation." Ballantine Books. 2002.

- Haberman, Clyde. "Vindication at Last for a Woman Scorned by Australia's News Outlets." The New York Times. Nov. 16, 2014. (Oct. 14, 2015) http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/17/us/vindication-at-last-for-a-woman-scorned-by-australias-news-media.html?_r=0

- Hueske, Edward E. "Practical Analysis and Reconstruction of Shooting Incidents." CRC Press. Nov. 29, 2005.

- International Association for Identification. https://www.theiai.org/

- International Association of Bloodstain Pattern Analysts. (Nov. 30, 2021)

- International Association of Bloodstain Pattern Analysts. (Nov. 30, 2021)https://iabpa.org

- Iowa State University. "Iowa State Engineer Working to Put More Science Behind Bloodstain Pattern Analysis." April 18, 2013. (Oct. 12, 2015) http://www.news.iastate.edu/news/2013/04/18/bloodstains

- James, Stuart H., et al. "Forensic Science: An Introduction to Scientific and Investigative Techniques, Fourth Edition." Taylor & Francis. Jan. 13, 2014.

- James, Stewart H. et al. "Principles of Bloodstain Pattern Analysis: Theory and Practice." CRC Press. 2005.

- Latson, Jennifer. "Why that 'Dingo's Got My Baby' Line isn't Funny." Time. Oct. 29, 2014. (Oct. 14, 2015)

- Latson, Jennifer. "Why that 'Dingo's Got My Baby' Line isn't Funny." Time. Oct. 29, 2014. (Oct. 14, 2015) http://time.com/3537456/dingo-got-my-baby/

- Linder, Douglas O. "The Trial Transcript in Crown v Lindy and Michael Chamberlain ("The Dingo Trial"): Selected Excerpts." Famous Trials. (Oct. 14, 2015) http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/chamberlain/chamberlaintranscript.html

- Lindy Chamberlain. (Nov. 30, 2021)

- Lindy Chamberlain. (Nov. 30, 2021)https://lindychamberlain.com/the-story/timeline-of-events/

- Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension. "Bloodstain Pattern Analysis." (Nov. 30, 2021)

- Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension. "Bloodstain Pattern Analysis." (Nov. 30, 2021)https://dps.mn.gov/divisions/bca/bca-divisions/forensic-science/Pages/forensic-programs-crime-scene-bpa.aspx

- Murray, Elizabeth. "Blood Spatter Lecture." Marshall University College of Science. Feb. 19, 2008. (Oct. 26, 2015) http://www.science.marshall.edu/murraye/2008%20Forensics%20Lectures/Blood%20Spatter%202008color.pdf

- National Forensic Science Technology Center. "Blood Spatter Animations." 2008. http://gallery.nfstc.org/swf/BloodSpatters.html

- Nickell, Joe and John F. Fischer. "Crime Science: Methods of Forensic Detection." University Press of Kentucky. 1999.

- Ramsland, Katherine. "The Forensic Science of C.S.I." Berkeley Boulevard. 2001.

- Red Rocks Community College. "The Many Faces of Criminal Justice." 2014. (Oct. 15, 2015) http://www.rrcc.edu/criminal-justice/criminal-justice-careers#blood

- Rosina, J. et al. "Temperature Dependence of Blood Surface Tension." Physiological Research. Vol. 56 (Suppl. 1). Pages S93-S98. 2007. (Oct. 12, 2015) http://www.researchgate.net/publication/6283606_Temperature_dependence_of_blood_surface_tension

- Shen, A.R. et al. "Toward Automatic Blood Spatter Analysis in Crime Scenes." Proceedings of the Institution of Engineering and Technology Conference on Crime and Security. Page 378. 2006. http://mi.eng.cam.ac.uk/research/projects/BloodSpatter/BloodSpatter_ShenBrostow.pdf

- Slemeko, Joe. "Bloodstain Tutorial." Joseph Slemeko Forensic Consulting, 2007. http://www.bloodspatter.com/BPATutorial.htm

- Wonder, Anita Y. "Bloodstain Patterns: Identification, Interpretation and Application." Academic Press. Dec. 17, 2014. (Oct. 12, 2015)

- , 2014. (Oct. 12, 2015)

Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article:

- [email protected]

- 01235 774870

How blood pattern analysis can be used to solve a murder: the Gareth MacDonald case

News December 01, 2021

By Forensic Access

Forensic Access recently featured in the BBC’s new true crime series which explored the role of scientists in forensic investigations, showing how some of the UK’s most serious crimes were solved. Episode 14: Paint Materials and Blood Patterns covered Forensic Access’ resident BPA expert, Dr. Philip Avenell’s, involvement with the Gareth MacDonald case. Here we tell the story of how Blood Pattern Analysis was used to solve the murder and bring Mr. MacDonald’s killer to justice.

The body of Gareth MacDonald, 30, was discovered in a Travelodge hotel room after he sustained multiple blows to the head in September 2007.

He was found in a ground floor room at Heston services next to the M4 motorway early on the morning of Saturday 15 th September. There was a significant amount of blood on the bedsheets and it appeared at an early stage that a fire extinguisher discovered at the scene was the murder weapon.

MacDonald, a father of three from Prestatyn, North Wales was headed to London with his boyfriend Glenn Rycroft, who he met online the year before. Rycroft claimed that MacDonald was safe and well when he left the hotel room at 07:00 that morning, but when he returned fifteen minutes later, he discovered MacDonald lifeless in a pool of blood.

However, there were no signs of forced entry, and Rycroft was stained with the victim’s blood with his fingerprints were discovered on the murder weapon. His explanation for this was that he attempted to hug Gareth’s body, which meant that he himself became covered in the deceased’s blood.

Rycroft’s actions had contaminated the crime scene, meaning that finding forensic evidence was now a major challenge. This is when the police turned to forensic science for help, enlisting the expertise of Dr. Philip Avenell who is a specialist in blood pattern analysis.

The police first submitted the shoes that Rycroft has been wearing at the time of his arrest. The right shoe had some blood staining on it but there was nothing particularly distinctive there, whereas the left shoe had a very clear impact spatter on it.

“The front on view the shoe showed a distribution of blood spatters across it of varying sizes – but many of them very small.

“Small blood stains won’t travel very far, so you can start to get an idea of how far away the perpetrator was. The shoe was close to impact with wet blood,” Dr. Avenell said.

Due to the colour and texture of the material that some items are made out of, it is not always easy to clearly see blood on an exhibit, particularly the fine detail. Because of this, scientists will make sketches or use software to represent basic images of an item, which can then be annotated to clearly show exactly where the blood appeared and the type of blood staining present.

“From the digital sketch you can see there is a lot more blood on there than is visible to the naked eye when you are looking at the exhibit. It really highlights that there was a heavy impact from wet blood that’s made its way onto the shoe,” Dr. Avenell said.

Rycroft claimed to have found MacDonald deceased when he went back to the hotel room, however the blood pattern evidence on Rycroft’s shoes told a different story. It showed that Rycroft could have been in the room when MacDonald was fatally injured. The police now had crucial evidence that potentially placed Rycroft at the scene of the crime.

The prosecution now required further proof of what had happened in the hotel room. Blood spatter on Rycroft’s shoes showed that he was in close proximity to MacDonald when there had been a heavy impact into wet blood, and further examination of Rycroft’s clothing was needed.

Dr. Avenell examined the trousers that Rycroft had been wearing at the time of MacDonald’s murder and had been recovered from Rycroft when he was taken into police custody.

“There was a lot of heavy blood staining on the trousers. This is what we call contact blood staining, where the item has leant into something that’s wet with blood or vice versa.

“There’s difficulties when you have lots of heavy blood stains and lots of different types of blood patterns overlaying each other. It then becomes quite difficult to work out exactly what’s there. That’s when you’re looking at the very fine, small detail in the blood,” he said.

Dr Avenell began an intricate examination of the blood stains on Rycroft’s trousers, finding a small yet vital clue. Around halfway up the left leg, the team found three very small blood stains which were identified as blood that’s travelled through the air and landed on the surface of the trousers.

The consistency of the blood was clearly different to that of the other blood stains, proving to be clotted blood which meant that these blood stains were made at a different time.

Dr. Avenell then turned his attention to the bedsheets. They were also soaked in blood, but amongst the heavy staining he discovered further evidence of clotted blood – just like on Rycroft’s trousers.

“We could see where the impact had happened and the blood radiated out from the point of impact. From the initial impact, the blood started to flow and then there was a time delay for that blood to start clotting. This showed there had been a second impact into the blood after that,” he said.

For Dr. Avenell, this information provided a sequence of events surrounding MacDonald’s murder. It showed that MacDonald had been struck once, then a minimum minutes later as the blood was beginning to clot, he was struck a second time.

“We knew there had been an impact into blood after there had been a period of time of bleeding. Typically, this is between three and fifteen minutes. It showed there had been at least two blows and that the blows were minutes apart.

“You look at what you’ve got and you try to understand the timeline of events and what has happened. It’s interesting when you then start to piece them together,” he said.

Blood pattern analysis by Dr. Avenell was pertinent to the prosecution’s case, providing police with the definitive answer which DNA evidence and fingerprints evidence would not have achieved.

In July 2009 Glenn Rycroft stood trial at the Old Bailey. He was found guilty of murder and sentenced to life in prison, serving a minimum of twenty-five years.

Blood Pattern Analysis Expertise

The world-class team of forensic scientists at Forensic Access operate in bespoke facilities. The forensic work we carry out is to the highest quality standards.

We have a dedicated team of Casework Managers who support all defence work, providing end-to-end assistance and coordination. The Casework team has direct access to our team of scientists, helping barristers and solicitors prepare a more effective defence strategy, and all expert witness reports are thoroughly documented and peer reviewed.

To learn more about the forensic services we offer, or to receive a free consultation and quote, please fill-in our contact form or Tel: 01235 774870.

You might also be interested in these articles…

Leave No Stone Unturned- Professor Angela Gallop shares her insights into what it takes to solve the most complex cases

In a recent webinar Professor Angela Gallop spoke with Alex O’Brien from the Association of British Science Writers, sharing insights,…

May 24, 2021

Steps to Choosing an Expert Witness

Finding the right expert witness is a key step in building your defence strategy and can either make or break…

September 29, 2021

Unpacking and Understanding Cell Site Analysis in Forensic Investigations

Cell site analysis is not an exact science, however, it is a recognised and accepted method of geolocating a mobile…

August 12, 2021

The New York Times

Magazine | how an unproven forensic science became a courtroom staple, how an unproven forensic science became a courtroom staple.

By LEORA SMITH and PROPUBLICA MAY 31, 2018

A timeline of a niche, unproven discipline that gained a hold in the American justice system.

By LEORA SMITH, PROPUBLICA MAY 31, 2018

Testimony from bloodstain-pattern analysts is now accepted in courts throughout the country. But in recent years, some scientists and legal scholars have questioned the training of these experts, as well as the validity of the field itself. How did a niche, unproven discipline gain a hold in the American justice system and proliferate state by state?

The modern era of bloodstain-pattern analysis began when a small group of scientists and forensic investigators started testifying in cases, as experts in a new technique. Some of them went on to train hundreds of police officers, investigators and crime-lab technicians — many of whom began to testify as well. When defendants appealed the legitimacy of the experts’ testimony, the cases made their way to state appeals courts. Once one court ruled such testimony admissible, other states’ courts followed suit, often citing their predecessors’ decisions. When discussing the reliability or accuracy of the technique, judges typically relied on their own — or the testifying expert’s own — assessment. Rarely, if ever, have courts required objective proof of bloodstain-pattern analysis’ accuracy.

Sam Sheppard, an Ohio doctor, is convicted of murdering his wife in a case that attracts widespread attention. Paul Leland Kirk, a renowned scientist and criminalist who worked on the Manhattan Project, studies the bloodstains in the Sheppard home and, the following year, offers an interpretation of events that the defense believes exonerates Sheppard.

People v. Carter

The Supreme Court of California affirms that bloodstain-pattern analysis is a proper area for expert testimony and that Kirk is a qualified expert in the field. The case is possibly the earliest instance of an appellate court explicitly accepting bloodstain-pattern analysis as an appropriate field of expertise.

• Sets precedent in California.

Sam Sheppard is retried, and Kirk’s findings play a central role in Sheppard’s defense. Sheppard is found not guilty.

Pedersen v. State

The Supreme Court of Alaska holds that bloodstain-pattern analysis is an acceptable area for expert testimony. An Alaska State Police officer uses blood spatters on a crab-fishing ship to determine where the victim was standing when shot.

• Sets precedent in Alaska.

The United States Department of Justice publishes a report, “Flight Characteristics and Stain Patterns of Human Blood,” by Herbert Leon MacDonell, an instructor at a two-year college in New York with a master’s degree. It becomes a foundational text in the field of bloodstain-pattern analysis.

MacDonell teaches his first Bloodstain Institute, a weeklong workshop, in Jackson, Miss., training police officers as bloodstain-pattern analysts. Months later, he teaches a second institute in Elmira, N.Y. Over the next few decades, MacDonell will train more than 1,000 new analysts.

Compton v. Commonwealth

The Supreme Court of Virginia rules that bloodstain-pattern analysis is a proper area for expert testimony. A Danville police officer testifies that bloodless circles on the floor helped determine that the victim was probably sitting at a table when shot.

• Sets precedent in Virginia.

People v. Erickson

An Illinois appellate court upholds a man’s conviction for murdering his wife. MacDonell testifies that blood patterns on the defendant’s clothes suggest that his wife’s blood spattered on him while he attacked her. On appeal, the court doesn’t rule on the issue of admissibility of experts in bloodstain-pattern analysis, because the defendant did not specifically appeal MacDonell’s admission as an expert.

• The case does not set bloodstain-pattern-analysis precedent in Illinois, but it is later cited by courts in Michigan and Texas to support the admission of experts in the field.

State v. Hall

The Supreme Court of Iowa affirms the admission of bloodstain-pattern evidence and the admission of MacDonell as an expert. The court refers to MacDonell’s field as “relatively uncomplicated” and, as a result, does not require extensive proof of its reliability. The judges write, “The evidence offered to show the reliability of the bloodstain analysis included: (1) Professor MacDonell’s considerable experience and his status as the leading expert in the field; (2) the existence of national training programs; (3) the existence of national and state organizations for experts in the field; (4) the offering of courses on the subject in several major schools; (5) use by police departments throughout the country in their day-to-day operations; (6) the holding of annual seminars; and (7) the existence of specialized publications.” The court does not acknowledge that MacDonell himself is the source of almost all these indicators of reliability.

• Sets precedent in Iowa.

State v. Hilton

The Supreme Judicial Court of Maine discusses the testimony of an expert in bloodstain-pattern analysis but does not actually rule on the issue of admissibility of such testimony.

• The case does not set precedent in Maine, but it is later cited by courts in Idaho and Texas to support the admission of experts in bloodstain-pattern analysis.

State v. Melson

The Supreme Court of Tennessee affirms a man’s murder conviction and death sentence and finds that bloodstain-pattern-analysis testimony of MacDonell was properly admitted.

• Sets precedent in Tennessee.

MacDonell holds his first Advanced Bloodstain Institute. Twenty-two graduates of the advanced class go on to form the International Association of Bloodstain Pattern Analysts, and Tom Bevel, an Oklahoma police officer and former student of MacDonell’s, becomes its first president.

Farris v. State

The Court of Criminal Appeals of Oklahoma rules that bloodstain-pattern analysis is a proper area for expert testimony. In a murder case under review, Bevel had testified that the bloodstains showed that the defendant struck the victim multiple times after shooting him and that the victim tried to defend himself.

• Sets precedent in Oklahoma, citing cases in Alaska and California.

People v. Knox

An appellate court in Illinois accepts bloodstain-pattern analysis as a proper area of expertise and holds that a police officer who takes a three-week course with MacDonell is qualified to testify as an expert.

• Sets precedent in Illinois.

Jordan v. State

The Supreme Court of Mississippi holds that even if a court erred in admitting a bloodstain-pattern analyst, the testimony was not influential enough to merit a retrial. The expert in the case attended a one-week institute with MacDonell in 1973, the first year the course was offered.

Lewis v. State

An appellate court in Texas affirms the reliability of bloodstain-pattern analysis and MacDonell’s qualification to testify as an expert witness.

• Sets precedent in Texas, citing cases in California, Illinois, Maine and Tennessee.

Fox v. State

The Supreme Court of Indiana upholds a conviction and finds that the expert in bloodstain-pattern analysis who testified in a murder case is qualified because he met Indiana’s requirements for expert witnesses: His knowledge exceeded that of an “average layperson,” and he had sufficient knowledge and skill to aid the judge and jury at trial. The detective who testified had attended one course on bloodstain-pattern analysis in 1980 and had never testified about such evidence before.

• Sets precedent in Indiana.

State v. Moore

The Supreme Court of Minnesota rules that bloodstain-pattern analysis is a proper area for expert testimony and that a serology expert who has never taken a course on bloodstain-pattern analysis is qualified enough to testify as an expert.

• Sets precedent in Minnesota, citing cases in Illinois, Iowa and Texas.

State v. Rodgers

The Supreme Court of Idaho decides that bloodstain-pattern analysis is an appropriate area for expert testimony. The two experts in the case had trained with MacDonell and Bevel. The court affirms the men’s admission as experts, saying they each meet Idaho’s legal standard, which requires only that experts be more knowledgeable on a topic than an average juror.

• Sets precedent in Idaho, citing cases in Maine, Oklahoma, Tennessee and Texas.

State v. Goode

The Supreme Court of North Carolina rules that bloodstain-pattern analysis is admissible as expert testimony and upholds the death sentence for a defendant convicted of two counts of first-degree murder. The expert, Duane Deaver, worked in forensics for the State Bureau of Investigation and had studied bloodstain-pattern analysis with former students of MacDonell and Kirk. Deaver testified that the defendant, who appeared to have no blood on his clothes, actually had minuscule blood spots on his boots.

• Sets precedent in North Carolina, citing cases in Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Oklahoma, Tennessee and Virginia. People v. Haywood

People v. Haywood

The Michigan Court of Appeals affirms the admission of bloodstain-pattern-analysis testimony and holds, among other reasons, that because bloodstain-pattern analysis is not a novel technique, extensive proof of its reliability is not required.

• Sets precedent in Michigan, citing cases in California and Texas.

State v. Halake

The Tennessee Court of Criminal Appeals overturns a conviction of first-degree murder, finding that a police officer who had never attended a full course in bloodstain-pattern analysis was improperly admitted as an expert at trial. The court contrasts the officer’s credentials with experts admitted by other courts, including MacDonell.

Holmes v. State

The Texas Court of Appeals holds that a detective who attended one weeklong bloodstain-pattern-analysis institute is sufficiently qualified to testify as an expert witness and upholds Texas’ longstanding acceptance of bloodstain-pattern analysis as a reliable technique fit for expert testimony.

• Sets precedent in Texas, citing cases from 15 other states.

A groundbreaking National Academy of Sciences study finds serious deficiencies in the field of forensic science in the United States and notes that “the uncertainties associated with bloodstain-pattern analysis are enormous.” The authors note that “in general, the opinions of bloodstain-pattern analysts are more subjective than scientific.”

A federal court finds that Duane Deaver, who testified as a bloodstain analyst in the 1995 North Carolina case State v. Goode, had performed inadequate testing. An audit of the state forensics lab where he worked will find the next year that Deaver provided misleading information on his reports for years. By the time these findings are public, judges in Tennessee and Texas will have already have cited State v. Goode in deciding to admit bloodstain-pattern analysis as a reliable field.

In January, the Texas Forensic Science Commission holds a one-day hearing, prompted in part by its investigation into the role that a minimally trained bloodstain-pattern analyst played in the convictions of Joe Bryan. In February, the commission decides to create an accreditation requirement for bloodstain-pattern-analysis experts in Texas.

Related Coverage

Blood will tell, part 1: who killed mickey bryan.

May 23, 2018

Blood Will Tell, Part 2: Did Faulty Evidence Doom Joe Bryan?

May 31, 2018

More on NYTimes.com

Advertisement

- Forensic Science Resources

- Special Features

Blood Spatter Evidence in Bryan Case

Recent testimony from an evidentiary hearing in the Joe Bryan case in Texas has centered on blood spatter interpretation. Bryan was a school principal who has been serving a 99-year prison sentence for the 1985 murder of his wife. His conviction was based in part on the testimony of an expert witness in blood spatter interpretation.

The blood spatter testimony indicated that the weapon used was a .357, like the one that Bryan owned. The prosecution stated that a flashlight found in Bryan’s car days after the murder contained small drops of the victim’s blood, although only presumptive tests were conducted. The blood spatter analyst testified the killer held the flashlight as he shot from close range.

Bryan continues to assert his innocence and an evidentiary hearing was held last month in which his attorney argued – backed by the testimony of a crime scene investigator – that the blood spatter testimony presented at trial was scientifically unsubstantiated. The hearing is currently in recess, awaiting the results of DNA testing on the flashlight that are expected to come back sometime in the fall.