- Partnership

- The Network

- Secretariat

- Steering Committee

- International Cooperation

- Policies and Institutional Arrangements

- Asymmetries and Gaps

- Data and Statistics

- Modelling and Analytical Tools

- Means of Implementation

- Technological Areas and Innovative Systems

- Water, Energy and COVID-19

- Case Studies

- News and Events

- Publications

Itaipu’s 17 Case Studies Responding to the 17 Sustainable Development Goals

End Poverty In All Its Forms Everywhere

Download Case Study

End Hunger, Achieve Food Security And Promote Sustainable Agriculture

Ensure Healthy Lives And Promote Well-Being For All At All Ages

Ensure Inclusive And Equitable Quality Education And Promote Lifelong Learning Opportunities For All

Achieve Gender Equality And Empower All Women And Girls

Ensuring Availability And Sustainable Management Of Water And Sanitation

Ensuring Access To Affordable, Reliable, Sustainable And Modern Energy For All

Promote Sustained Inclusive And Sustainable Economic Growth, Full And Productive Employment And Decent Work For All

Build Resilient Infrastructure, Promote Inclusive And Sustainable Industrialization And Foster Innovation

Reduce Inequality Within And Among Countries

Make Cities And Human Settlements Inclusive, Safe, Resilient And Sustainable

Ensure Sustainable Consumption And Production Patterns

Take Urgent Action To Combat Climate Change And Its Impacts

Conserve And Sustainably Use The Oceans, Seas And Marine Resources

Protect, Restore And Promote Sustainable Use Of Terrestrial Ecosystems, Sustainably Manage Forests, Combat Desertification, Halt And Reverse Land Degradation And Halt Biodiversity Loss

Promote Peaceful And Inclusive Societies For Sustainable Development

Strenghten The Means Of Implementation And Revitalize The Global Partnership For Sustainable Development

Achieving Sustainable Development Goals: A Case Study of Dalmia Bharat Sugar & Industries Limited

- Scientific Correspondence

- Published: 06 January 2024

- Volume 26 , pages 313–324, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Priyanka Singh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6585-4993 1 ,

- S. Solomon 2 ,

- Pankaj Rastogi 3 ,

- Kuldeep Kumar 3 &

- Govind P. Rao 4

97 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Sugarcane-based agro-industry in India is spread over 5.2 million hectare and employs around 12 million people. It has immense potential to create shared value for the people, communities, businesses, economies, and ecosystems. This sector is instrumental in positively influencing a number of key Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This study was performed at Dalmia Bharat Sugar & Industries Limited (DBSIL), highlighting important SDGs, which the company has achieved over the years. The DBSIL has five sugar units (600,000 tonnes sugar/annum), five co-generation plants (119 MW) and two distilleries (305 KLPD) producing bio-ethanol and hand sanitizer. The company’s 36,500 TCD plants are supporting over 2500 employees, 1,50,000 farmers and their families with an annual turnover of USD 3.7 million (INR 2739 crore). The Sustainable Sugar Intensification project is capable of producing 4.5–5.0 million tonnes of quality sugarcane annually, with 30% saving of irrigation water. It has established 559 vermi-compost units, 948 farmyard manure units, and distributed 1358 solar-powered battery sprayers to promote green technology. The DBSIL has taken several initiatives to protect groundwater quality, rainwater harvesting, reducing greenhouse gases emissions, bio-recycling of wastes and effluents to minimize the carbon foot prints. During 2021, about 29 million KL of water was conserved through drip irrigation; constructed 1401 water harvesting structures and 9200 hectares of land were brought under watershed projects. The company has achieved Zero Liquid Discharge at all their plants and provided 8,01,910 m 3 of recycled water to the farmers for irrigation. At present, 1179 self-help groups consisting of 14,000 women members and 12 training centers are active in income-generating and entrepreneurship development activities. Company’s CSR funded programs include nine e-literacy centers, women and child education, rural health services, climate action, sanitation and potable water facilities, COVID-19 relief, prevention initiatives, and rural roads. The five co-generation plants are producing clean and green electrical energy, and around 60% of surplus renewable electricity is exported to grid for electricity supply to 145 villages. DBSIL has partnered with several NGOs to drive improvement in economic, social and environmental performance of growers and millers, contributing in achieving goals of SDGs.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Sustainability in Sugarcane Supply Chain in Brazil: Issues and Way Forward

Raffaella Rossetto, Nilza Patricia Ramos, … Marcos Guimarães de Andrade Landell

Sustainability of sugarcane production in Brazil. A review

Ricardo de Oliveira Bordonal, João Luís Nunes Carvalho, … Newton La Scala Jr

Environmental and Economic Benefits of Sustainable Sugarcane Initiative and Production Constraints in Pakistan: A Review

Anonymous 2020. https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2023 - 02/10_Report_of_the_Task_Force_on_Sugarcan_%20and_Sugar_Industry_0.pdf.

Anonymous 2021. Dalmia Bharat Sugar, Catalyzing Transition Green Growth, Dalmia Bharat Sugar and Industries Limited, Corporate Responsibility Report FY2020–21. https://www.dalmiasugar.com/sustainability .

Anonymous. 2023. https://www.isosugar.org/publication/135/sugar-and-sustainable-development-goals---mecas(18)17 .

G.P. Rao and P. Singh 2022. Value addition and fortification in non-centrifugal sugar (jaggery): A potential source of functional and nutraceutical foods. Sugar Tech 24(2):387–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12355-021-01020-3

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

N.A. Rivera 2022. Bioindicators for the sustainability of sugar agro-industry. Sugar Tech 24 (3):651–661.

Article Google Scholar

Singh, P. 2020. Sugar industry: A hub of useful bio-based chemicals. In Sugar and sugar derivatives: changing consumer preferences , eds. Mohan, N., P. Singh, 171–194. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-6663-9_11

Chapter Google Scholar

Singh, P., and J. Singh 2020. Sugarcane and sugar diversification: Opportunities for small-scale entrepreneurship. In Sugar and sugar derivatives: changing consumer preferences , eds. Mohan, N., P. Singh, 241–251. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-6663-9_15

P. Singh, Y.G. Ban, L. Kashyap, A. Siraree and J. Singh. 2020. Sugar and sugar substitutes: Recent developments and future prospects. In Sugar and sugar derivatives: changing consumer preferences eds. N. Mohan and P. Singh, 39–75. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-6663-9_4

S. Solomon and M. Swapna 2022. Indian sugar industry: Towards self-reliance for sustainability. Sugar Tech 24: 630-650.

S. Solomon, G.P. Rao, M. Swapna, A. Kumar and R.C. Singh 2019. Corporate social responsibility initiatives and their impact on sugar-mill performance: A case study of the seksaria biswan sugar factory, India. Proceedings of the International Society of Sugar Cane Technologists 30: 377-383.

Google Scholar

S. Solomon, P. Singh, K. Kumar Rastogi, and G.P. Rao. 2023 Contributions of the Indian sugar industry to sustainable development—agenda 2030: A case study of dalmia bharat sugar and industries limited. Proceedings of the International Society of Sugar Cane Technologists 31: 97.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the management of Dalmia Bharat Sugar and Industries Limited, cane development staff and all technical and supporting personnel of the DBSIL units for their cooperation and unstinted support in carrying out this study

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

U. P. Council of Sugarcane Research, Shahjahanpur, U.P., India

Priyanka Singh

Lucknow/Society for Sugar Research and Promotion, Indian Institute of Sugarcane Research, New Delhi, India

Dalmia Bharat Sugar and Industries Limited, Hansalaya Building, 15, Barakhamba Road, New Delhi, India

Pankaj Rastogi & Kuldeep Kumar

Society for Sugar Research and Promotion, New Delhi, India

Govind P. Rao

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Priyanka Singh .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Singh, P., Solomon, S., Rastogi, P. et al. Achieving Sustainable Development Goals: A Case Study of Dalmia Bharat Sugar & Industries Limited. Sugar Tech 26 , 313–324 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12355-023-01343-3

Download citation

Received : 06 April 2023

Accepted : 11 November 2023

Published : 06 January 2024

Issue Date : April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12355-023-01343-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Sugar industry

- Sustainable development goals

- Corporate social responsibility

- Co-generation

- Greenhouse gases

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 06 August 2022

Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals in the post-pandemic era

- Wenwu Zhao ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5342-354X 1 , 2 ,

- Caichun Yin 1 , 2 ,

- Ting Hua 1 , 2 ,

- Michael E. Meadows ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8322-3055 3 , 4 , 5 ,

- Yan Li 1 , 2 ,

- Yanxu Liu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3571-1932 1 , 2 ,

- Francesco Cherubini 6 ,

- Paulo Pereira ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0227-2010 7 &

- Bojie Fu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9920-9802 1 , 2 , 8

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 9 , Article number: 258 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

41 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Development studies

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to pose substantial challenges to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Exploring systematic SDG strategies is urgently needed to aid recovery from the pandemic and reinvigorate global SDG actions. Based on available data and comprehensive analysis of the literature, this paper highlights ongoing challenges facing the SDGs, identifies the effects of COVID-19 on SDG progress, and proposes a systematic framework for promoting the achievement of SDGs in the post-pandemic era. Progress towards attaining the SDGs was already lagging behind even before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Inequitable distribution of food–energy–water resources and environmental crises clearly threaten SDG implementation. Evidently, there are gaps between the vision for SDG realization and actual capacity that constrain national efforts. The turbulent geopolitical environment, spatial inequities, and trade-offs limit the effectiveness of SDG implementation. The global public health crisis and socio-economic downturn under COVID-19 have further impeded progress toward attaining the SDGs. Not only has the pandemic delayed SDG advancement in general, but it has also amplified spatial imbalances in achieving progress, undermined connectivity, and accentuated anti-globalization sentiment under lockdowns and geopolitical conflicts. Nevertheless, positive developments in technology and improvement in environmental conditions have also occurred. In reflecting on the overall situation globally, it is recommended that post-pandemic SDG actions adopt a “Classification–Coordination–Collaboration” framework. Classification facilitates both identification of the current development status and the urgency of SDG achievement aligned with national conditions. Coordination promotes domestic/international and inter-departmental synergy for short-term recovery as well as long-term development. Cooperation is key to strengthening economic exchanges, promoting technological innovation, and building a global culture of sustainable development that is essential if the endeavor of achieving the SDGs is to be successful. Systematic actions are urgently needed to get the SDG process back on track.

Similar content being viewed by others

Expert review of the science underlying nature-based climate solutions

B. Buma, D. R. Gordon, … S. P. Hamburg

Global supply chains amplify economic costs of future extreme heat risk

Yida Sun, Shupeng Zhu, … Dabo Guan

The role of artificial intelligence in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals

Ricardo Vinuesa, Hossein Azizpour, … Francesco Fuso Nerini

Introduction

In 2015, the United Nations (UN) adopted “The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” and proposed 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with the aim of eradicating poverty and promoting peace and prosperity for all on a healthy planet by 2030 (UN, 2015 ). While time is running out to achieve the 2030 Agenda, the world is struggling to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. By May 2022, more than 500 million COVID-19 cases were confirmed, with more than six million deaths (WHO, 2022 ). Health services were stretched to the verge of collapse, lockdowns resulted in labor forces being laid off, and millions pushed back to extreme poverty and malnutrition (Sachs et al., 2020 ; Stephens et al., 2020 ).

Even prior to the pandemic, SDG advancement was constrained and delayed, but the health crisis and socio-economic recession resulting from COVID-19 have severely impeded SDG progression. Systematic and practical solutions are urgently needed to get the SDGs back on track. Accordingly, the objectives of this paper are to (1) analyze challenges to SDGs progress that prevailed prior to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic; (2) identify the impact of COVID-19 on progress towards achieving the SDGs; and (3) provide a systematic and practical framework for implementing SDGs in the post-pandemic era.

Challenges facing SDG progress before COVID-19

Inequitable access to resources limits sustainable development.

Food, energy, and water (SDG 2, 6, 7) are the resource pillars on which the SDG implementation stands (Stephan et al., 2018 ). Their security is threatened by human development pressures and ecosystem degradation. Since 1970, due to the doubling of the global population (World Bank, 2020 ), primary energy and food production have more than tripled (IPBES, 2019 ), yet billions of people still suffer from food and energy shortages, and inadequate water supply in terms of both quantity and quality (Bazilian et al., 2011 ). With the global population estimated to rise to nine billion by 2050, energy and food production must increase by 50% and 70%, respectively, to meet human basic needs (EIA, 2021 ; UNEP, 2021 ). Moreover, one-sixth of human-dominated land has experienced ecosystem service degradation (UNEP, 2021 ), endangering the supply of food, energy, and water, and therefore undermining the very foundations of sustainable development (Yin et al., 2021 ).

Environmental crises threaten SDG implementation

Climate change, ecosystem degradation, and pollution (SDG 13–15) are major global environmental risks that weaken the natural foundations supporting the SDGs (UNEP, 2021 ). These risks inhibit efforts toward poverty reduction, food and agricultural security, human health, and water security (SDG 1–3, 6). Unstable climate conditions also compromise the safety of urban infrastructures (SDG 9, 11) (Nerini et al., 2019 ). Ecosystem degradation is detrimental to gender equality, especially in rural areas, where local livelihoods are primarily dependent on ecosystem services and women are discriminated against in terms of access to land and education (SDG 5) (Naidoo and Fisher, 2020 ; Yin et al., 2022 ). Increased levels of environmental degradation and pollution also amplify the development gap and accentuate inequalities between countries. Low-income countries, where development is highly dependent on healthy soil, clean water, and climate-sensitive sectors such as agriculture bear the greatest burden of climate change and pollution (SDG 10) (Lusseau and Mancini, 2019 ; Yin et al., 2021 ). Progress in sustainable energy, responsible production and consumption, economic growth, and decent work (SDG 7, 8, 12) are all hampered by environmental pollution and the loss of natural capital (IPBES, 2019 ). About 3.2 billion people are affected by land degradation and pollution, and climate-related natural disasters cost $155 billion in 2018 (Swiss Re Institute, 2019 ). More than 2500 conflicts worldwide were attributed to environmental crises that exacerbate migration and competition for natural resources (World Economic Forum, 2020 ), seriously jeopardizing the development of peaceful and inclusive societies (SDG 16, 17).

Gaps between SDG visions and actual capabilities discourage national efforts

The effective implementation of SDGs in a country depends on their integration into national socio-economic development plans. While the UN is committed to a policy of ‘leaving no one behind’ in achieving the SDGs, only about half the countries (53%) have completed or are developing, a roadmap for SDGs to guide their implementation (Allen et al., 2018 ). This is largely due to critical gaps between the SDGs’ requirements and the prevailing vision in countries, especially where the SDG framework sets higher requirements than the country’s development capacity. Under the constraints of a higher target threshold, the challenge remains as to how to formulate a feasible blueprint (Lu et al., 2015 ). Moreover, restricted by the inadequate technology and resource utilization efficiency, improvements in SDGs, including economic growth and social needs, often come with high environmental costs that put planetary boundaries at stake, which in turn negatively affects the overall achievement of SDGs (Hua et al., 2020 ; O’Neill et al., 2018 ). This emphasizes that upgrading technology is key to accelerating SDG progress and reducing the gap between goals and actual capabilities.

Turbulent geopolitical environment undermines the SDG process

Amid the pandemic and political conflicts, a peaceful external environment and functioning multilateral partnerships are critical to advancing the SDGs. Current geopolitical conflicts between countries are adding uncertainty to the SDG process (UN, 2020b ). Armed conflict and regional instability have caused widespread cropland abandonment, further negatively affecting food security. It is estimated that cultivated croplands in war-ravaged South Sudan reduced by 16% from 2016 to 2018 (Olsen et al., 2021 ). Trade wars between major economies led to a surge in soybean cultivation in Brazil, which has led to deforestation, overuse of agricultural land, and thus threatening carbon sequestration (Aguiar et al., 2016 ; Macedo et al., 2012 ). Geopolitical conflict, more especially the war in Ukraine in 2022 (Osendarp et al., 2022 ), has further undermined international markets and threatened food and energy security, constraining international cooperation that would promote the SDGs (Mach et al., 2019 ). Implementing SDGs depends largely on financial support, especially for developing countries with large infrastructure needs and funding gaps. Under the prevailing turbulent geopolitical environment, aid funding to developing countries is likely to be further reduced, leaving them even less able to fulfill their financial needs (UN, 2020a ). This highlights the importance of global coordination to extend sources of aid funds, cultivate social capital, and improve governance.

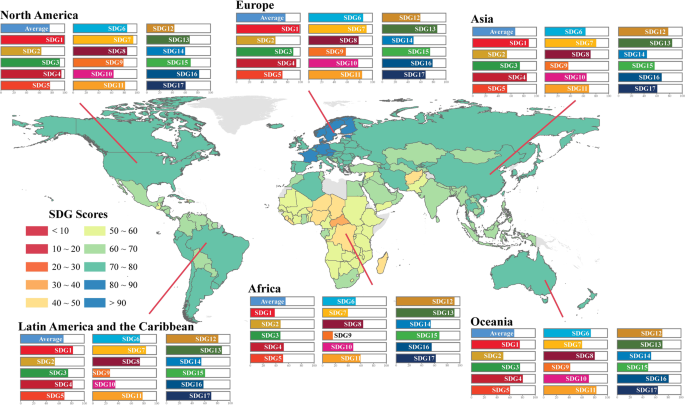

Imbalances and trade-offs limit the effectiveness of SDG implementation

Due to differences in the global resource base, status of the environment, and domestic and international political and economic circumstances, progress in advancing the SDGs is unbalanced and exhibits trade-offs globally (Figs. 1 , S1 , and S2b ). Overall, in developing countries, the risk of climate change and deficiencies in the availability of even basic needs (e.g., clean water, energy availability) are key challenges (Balasubramanian, 2018 ; Cheng et al., 2021 ), while for developed countries, responsible consumption and production, coupled with ecosystem integrity are the main bottlenecks (Yang et al., 2020 ). Additionally, the Matthew effect is manifested in differential SDG achievement, as lower income-level nations evidently make slower progress in implementing the SDG agenda (UN, 2020b ). Uneven SDG advancement, therefore, exacerbates development disparities between and within nations (Liu et al., 2021 ; Xu et al., 2020 ). On the other hand, the effectiveness of SDG actions and policies is affected by interactions between the goals and targets, and the extent to which synergies among them can be leveraged (Nilsson et al., 2018 ; Pradhan, 2019 ; Pradhan et al., 2017 ). Previous studies have highlighted negative interactions, for example between SDG10, SDG12, SDG13, and other goals that impede overall progress (Kroll et al., 2019 ; Pradhan et al., 2017 ). Such trade-offs appear to be even more pronounced in high-income countries. As SDG interactions evolve over time, synergies appear to be diminishing and trade-offs increasing, particularly in the case of interactions between SDG7 and SDG1, and SDG7 and SDG3 (Kroll et al., 2019 ). These perturbing findings mean that the current level of action towards implementing the SDGs is failing to leverage synergies and needs to be strengthened to overcome resistance induced by trade-offs.

The color of the map reflects the global average score for each country on the 17 SDGs. Bar charts indicate the SDG index scores for different subregions, including Asia, Africa, North America, Europe, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Oceania. We collected data from the Sustainable Development Report 2019 ( https://www.sdgindex.org/reports/sustainable-development-report-2019/ ).

The effects of COVID-19 on SDG progress

Covid-19 leads to a decline in sdg performance.

The COVID-19 pandemic has constrained progress in achieving the SDGs, as clearly illustrated by the marked decline in global SDG index scores in 2020 (Fig. S2a ) and the increase in global poverty (SDG1) for the first time in decades, whereby an additional 119–124 million people fell back into extreme poverty (UN, 2020b ). The impact of COVID-19 on population health and wellbeing, along with the disruption of medical services, may have reversed decades of SDG 3 progress (Ranjbari et al., 2021 ). In addition, more than 1.52 billion children and youth were out of school or university in 2020 under lockdowns, wiping out 20 years of education gains (SDG 4) (UN, 2020b ). During the pandemic, the world faced the worst economic recession since the Great Depression (Ibn-Mohammed et al., 2021 ) and precipitated the loss of about 255 million full-time jobs (SDG 8) (UN, 2020a ). The supply chain disruptions under lockdown conditions stalled the manufacturing industry and, GDP per capita was estimated to fall by 4.2% globally in 2020 (UN, 2020b ). Meanwhile, the aviation industry suffered its steepest decline in history (Dube et al. 2021 ) as the number of air passengers fell by 60% from 4.5 billion in 2019 to 1.8 billion in 2020 (SDG 9) (UN, 2020b , 2021a ).

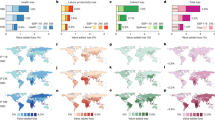

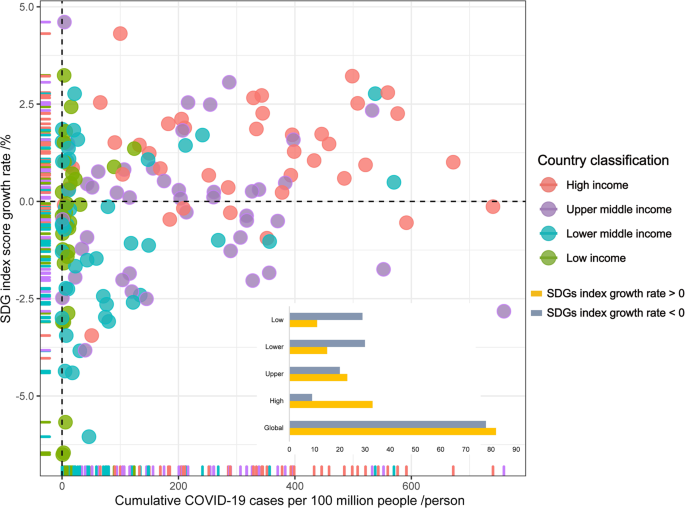

COVID-19 amplifies unevenness in SDG progress

COVID-19 has exacerbated differences among countries and communities in achieving the SDGs (Barbier and Burgess, 2020 ). Overall, the SDG index in almost half (49%) of the world’s countries has registered negative growth (i.e. SDG index score growth rate < 0, Fig. 2 ). Data show that SDG progress decreased significantly in most low and lower-middle-income countries, while it increased in high income countries (Fig. 2 ). Notwithstanding high COVID-19 confirmed rates in middle- and high-income countries, progress towards SDGs in 2020 has remained the same or, in some cases, actually improved (Fig. 2 ), suggesting that health systems, infrastructure, market and regulatory systems in such countries are more resilient to emergencies like COVID-19. Meanwhile, low-income countries lack the fiscal freedom to finance an adequate COVID-19 response and invest in recovery plans (Barbier and Burgess, 2020 ; UN, 2021b ). It has been estimated that COVID-19 increased the average Gini coefficient (SDG 10) in emerging market and developing countries by 6% (UN, 2021a ). Moreover, the risk of COVID-19 transmission has been shown to be much greater in densely populated urban areas (SDG11), which account for more than 90% of confirmed COVID-19 cases (UN, 2020a ), more especially in developing countries where high density informal settlements are abundant. COVID-19 also had an uneven impact on different socio-economic groups, since the poor and more vulnerable, including women, children, the elderly, and informal workers, have been the hardest hit (Hawkins et al., 2020 ). Women comprise up to 70% of the global health workforce, making them more susceptible to infection (UN, 2021a ), while increased care responsibilities and domestic violence during home isolation also threatened progress towards gender equality (SDG 5) (Chattu and Yaya, 2020 ). Older and homeless people were not only besieged by greater health risks but also likely to be less capable of supporting themselves in isolation (D’Cruz and Banerjee, 2020 ; UN, 2020a ).

The bar chart shows the number of countries (divided into global, high-income, upper-middle-income, lower-middle-income, and low-income countries) achieving positive and negative SDG growth (2020 compared to 2019), respectively. We collected data from the Sustainable Development Report 2020 ( https://www.sdgindex.org/reports/sustainable-development-report-2020/ ) and the WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard ( https://covid19.who.int/ ).

COVID-19 undermines connectivity and intensifies anti-globalization

The pandemic has delivered an unprecedented shock to the interconnected global system. Firstly, COVID-19 lockdowns directly limited inter-regional connectivity (such as the flow of human capital, and material and financial resources), which seriously affected the interconnected globalized economy and demand-supply chains (Dube et al., 2021 ; Galvani et al., 2020 ). COVID-19 has disrupted the global market, retarding progress towards economic growth (SDG 8) and production and consumption (SDG 12) in 80% and 70% of the world’s countries, respectively (Fig. S3 ). Secondly, the global lockdown has further disrupted social–ecological interactions. As the global recession loomed, local populations in developing countries with limited incomes were more likely to raid adjacent natural ecosystems, resulting in deforestation, poaching, overfishing, and the weakening of restoration initiatives (Roe et al., 2020 ). Indeed, the slump in ecotourism (SDG 9) during lockdown not only led to the loss of local income but also threatened ecological protection funds considered essential for wildlife and ecosystem conservation (SDG 15) (Naidoo and Fisher, 2020 ; Yin et al., 2021 ). Thirdly, in the absence of secure and stable international trade, many countries/regions were forced to depend more on domestic markets to maintain the demand for food, energy, and water (SDG 2, 6, 7), which in turn interrupts the food–energy–water nexus under conditions of limited ecological carrying capacity (Yin et al., 2022 ). Moreover, the pandemic disrupted global economic exchanges fueled regional inequality and disputes and exacerbated anti-globalization. Regional conflicts (such as wars, protests against structural inequality, and racism) intensified during COVID-19 (Cole and Dodds, 2021 ). Rising trade protectionism and anti-globalization have threatened both equality and peace (SDG 10, 16). Since multilateral and global partnerships are challenged by meager financial resources and regional conflicts, COVID-19 also impeded global partnerships, and, hence, SDG 17 progress has declined in 60.6% of the world’s countries (Fig. S3 ).

COVID-19 generates positive signals of change for SDGs

The pandemic not only posed challenges but also opportunities to promote sustainable transformation (Ibn-Mohammed et al., 2021 ; Pradhan and Mondal, 2021 ). Firstly, digital technology experienced a massive impetus and played a strongly supportive role, for example by improving healthcare responses, alleviating the impact of lockdowns, enabling business continuity through remote working, and supporting online education (Pan and Zhang, 2020 ). The digital economy and high-tech manufacturing fueled an economic recovery in late 2020, up 4% from the end of 2019 (SDG 9) (UN, 2021a ). Secondly, while income constraints may have triggered the plundering of ecosystem resources, the drastic reduction in industrial emissions and economic activity reduced CO 2 emissions and pollution, thereby improving environmental quality and ecosystem health in the short term (Le Quéré et al., 2020 ). COVID-19 was estimated to produce a 6% drop in greenhouse gas emissions for 2020 (SDG 13) (UN, 2021a ). Limited human activity during the lockdown provided a chance for ecosystems and oceans to recuperate (SDG 14) (Diffenbaugh et al., 2020 ). Nevertheless, such improvements are likely to be only short-lived (climate action progress in 85.6% of countries declined throughout 2020, Fig. S3 ). Any such environmentally positive signals need to be prolonged by implementing sustainable development commitment once the pandemic ends and the global economy recovers.

A systematic framework for promoting the achievement of SDGs in the post-pandemic era

To address the fragile foundations, uneven progress, and degraded cooperation context towards sustainable development and to help cope with the multiple challenges facing SDG progress before and amid COVID-19, we recommend that post-pandemic SDG actions adopt a systematic framework of “Classification–Coordination–Collaboration” (Fu et al., 2020 ).

Classification

Classification helps rationalize and identify the current development status, clarify the expected goals for sustainability, and select the appropriate development priorities and paths aligned with the national conditions.

Elucidating the impact of the pandemic : It is necessary for governments to adopt multiple solutions that deal with COVID-19’s adverse effects while maintaining positive momentum (Ranjbari et al., 2021 ). Containing the pandemic and avoiding further adverse social and economic impacts necessitates quick and effective interventions, not least the continuation of prevention, testing, and treatment measures but also through the effective roll-out of vaccines globally. Achieving herd immunity, in which a significant proportion of the population (70 percent) is vaccinated, remains an urgent requirement (Jean-Jacques and Bauchner, 2021 ). Improving health care systems, ensuring resource security, restoring livelihoods and production are also critical.

Identifying the urgency of SDGs : Some SDG targets are more urgent amid COVID-19 (e.g., medical and healthcare systems, food and water security) and, under the ongoing pandemic and economic recession, cash-strapped governments need to identify urgency and priorities among diverse SDG targets according to challenges and national development needs (Naidoo and Fisher, 2020 ). As noted above, identifying and harnessing the SDG synergies can enhance the effectiveness of SDG actions and policies. Based on the principles of cost–benefit and social–ecological analysis, governments, and experts need to determine win-win solutions (e.g., Nature-based Solutions) that minimize trade-offs, promote synergies, and address multidimensional development issues (Zhang et al., 2020 ), so as to meet their most urgent needs and to systematically promote the SDGs (Barbier and Burgess, 2020 ).

Classifying countries/regions standards for SDGs : COVID-19 has amplified deficiencies in the foundations of development, and inadequate resilience and recovery potential. It is difficult for less developed countries to achieve SDGs that are measured against a unified global standard, which therefore frustrates their efforts towards making progress. To implement targeted optimization measures for the SDGs, it would be helpful for the UN to classify different countries/regions, considering their differences in SDG baseline levels, resources, infrastructure, technology, and socio-economic status. More realistic and practicable SDG actions require common but differentiated targets for countries/regions at different levels of development. Countries within similar categories can establish national plans to take concerted action in terms of policy, finance, trade, infrastructure, and values.

Coordination

Coordination includes domestic and international support and inter and intra-departmental coordination for both short-term recovery and long-term development.

Domestic and international coordination : The global experience of COVID-19 suggests that stronger domestic and international coordination is needed for achieving SDGs. On one hand, countries need to establish their own management systems to ensure the security of basic resources (Wang et al., 2020 ), such as improving infrastructure and logistics systems and strengthening the domestic production and stock capacity. On the other hand, international organizations need to strengthen their coordination capacity to improve international dialog mechanisms, build platforms for bilateral and multilateral investment and trade cooperation, and coordinate market rules for basic resources, especially given the additional stresses brought about by the pandemic and associated impacts.

Coordination between different administrative departments : To enhance the synergistic effect among SDGs, it is vital that both intra- and inter-departmental coordination be reinforced. While the SDGs were originally presented and envisaged as separate goals, it is clear that they are strongly interdependent. Coordination between different target-related departments is key to avoiding policy overlap and conflict for SDGs. Facing financial and energy constraints after COVID-19, governments have the duty to seek solutions that minimize trade-offs, promote synergies, and address multidimensional development issues to systematically promote the SDGs.

Coordination between short-term recovery and long-term development : To set the goals back on the path to recovery, both short-term and long-term issues must be identified and addressed with targeted measures. In the short term, the pandemic has negatively impacted goals related to reducing poverty and securing food, water, and energy, which must be addressed urgently. However, in the longer term, improving infrastructure, promoting scientific and technological innovation, and optimizing the relationship between humans and nature are imperatives for the realization of the SDGs (Yang et al., 2020 ). Accordingly, in formulating socio-economic development policies for the post-pandemic era, attention of researchers and policymakers needs to be applied to both short-term recovery and long-term development.

Cooperation

Cooperation includes strengthening economic cooperation, promoting technological innovation, and jointly building a global culture of sustainable development.

Economic cooperation to strengthen global economic partnership : Different stakeholders urgently need to strengthen complementarity, adopt common but differentiated responsibilities and build a stable global economic environment. We recommend three actions for all relevant stakeholders as follows: (i) Provide targeted economic assistance to vulnerable communities/regions in a way that allocates aid funds scientifically, thus ensuring their more efficient and equitable use. (ii) Deepen international cooperation on production capacity by implementing actions that optimize production modes, improve production efficiency and economic benefits, increase employment, and avoid resource waste and environmental damage. (iii) Jointly build a platform for financial cooperation by expanding access to financing to strengthen the resilience of global markets.

Technological cooperation to promote scientific and technical innovation : If economies ravaged by the pandemic are to get back on track, there is an urgent need for researchers, corporations, and the technology industry to strengthen the exchange of scientific and technical innovation in the following areas: (i) Building platforms for collaboration that establish channels for joint innovation and technology transfer between countries/institutions while protecting intellectual and rights. (ii) Ensuring that funding for innovation and collaboration flows into key scientific and technical fields, thereby supporting original scientific achievements and guiding market funds towards them. (iii) Cultivating international talents to stimulate innovation and unleash the greater potential of scientific and technological innovation through collaboration.

Cooperation between cultures to shape sustainable development values. Repairing cultural isolation caused by COVID-19 and the lockdown is even more critical than ever if the world is to recover from the pandemic. On the basis of respecting cultural diversity, cultural institutions, and organizations need to take action to form and nurture a culture of global sustainability and values. Effective actions towards this include: (i) deepening and broadening access to education for sustainable development to enhance public understanding, recognition, and willingness to participate in SDGs, respect differences and diversity, and foster the values of harmony with nature. (ii) Improving the development and maintenance of a cultural infrastructure that reduces cultural imbalances that aggravate gender and racial discrimination and foment violent conflicts.

Concluding remarks

COVID-19 has delivered a grave shock to SDG progress. Under global lockdowns and economic recession, political disputes and armed conflicts constrain international coordination and cooperation for sustainable development. In addition, multiple pressures continue to threaten the achievement of SDGs, and their implementation is not simply a case of stepping out of the shadow of the pandemic, since ongoing population growth puts increased pressure on limited natural resources, climate change impacts social security and intensifies natural disasters, and ecosystem degradation and pollution shake the very foundations of sustainable development. We, therefore, urge the UN’s High-level Political Forum, national governments, researchers, and stakeholders to consider more seriously how to recover and transform SDG actions after the pandemic. In the post-pandemic era, it is urgent that more systematic solutions be found and adopted. Such solutions can be enhanced by reclassifying the SDG status and vision, coordinating multiple resources and policies, and promoting and consolidating economic, technological, cultural, and political collaboration. Last but not least, with just 8 years to 2030, we have to plan ahead regarding where and how SDGs should evolve in 2030 and after 2030. For the phase after 2030, the SDG vision needs to be oriented towards 2045, a year which, incidentally, marks the UN’s 100th anniversary. Ideally, the pandemic and global recession will in the future be considered a watershed, and Agenda 2030 is a milestone guiding the world towards Agenda 2045 and a truly sustainable future.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Aguiar APD, Vieira ICG, Assis TO et al. (2016) Land use change emission scenarios: anticipating a forest transition process in the Brazilian Amazon. Global Change Biol 22:1821–1840. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13134

Article ADS Google Scholar

Allen C, Metternicht G, Wiedmann T (2018) Initial progress in implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): a review of evidence from countries. Sustain Sci 13:1453–1467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0572-3

Article Google Scholar

Balasubramanian M (2018) Climate change, famine, and low-income communities challenge Sustainable Development Goals Comment. Lancet Planet Health 2:E421–E422. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2542-5196(18)30212-2

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Barbier EB, Burgess JC (2020) Sustainability and development after COVID-19. World Dev 135:105082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105082

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bazilian M, Rogner H, Howells M et al. (2011) Considering the energy, water and food nexus: towards an integrated modelling approach. Energy Policy 39:7896–7906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2011.09.039

Chattu VK, Yaya S (2020) Emerging infectious diseases and outbreaks: implications for women’s reproductive health and rights in resource-poor settings. Reprod Health 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-0899-y

Cheng Y, Liu HM, Wang SB et al. (2021) Global action on SDGs: policy review and outlook in a post-pandemic era. Sustainability 13:6461. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116461

Cole J, Dodds K (2021) Unhealthy geopolitics: can the response to COVID-19 reform climate change policy. Bull World Health Organ 99:148–154. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.20.269068

D’Cruz M, Banerjee D (2020) ‘An invisible human rights crisis’: the marginalization of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic—an advocacy review. Psychiatry Res 292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113369

Diffenbaugh NS, Field CB, Appel EA et al. (2020) The COVID-19 lockdowns: a window into the Earth System. Nat Rev Earth Environ 1:470–481. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-020-0079-1

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Dube K, Nhamo G, Chikodzi D (2021) COVID-19 pandemic and prospects for recovery of the global aviation industry. J Air Transp Manag 92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2021.102022

EIA (2021) International Energy Outlook 2021. EIA https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/ieo/pdf/IEO2021_ReleasePresentation.pdf . Accessed 24 Apr 2022

Fu B, Zhang J, Wang S et al. (2020) Classification–coordination–collaboration: a systems approach for advancing Sustainable Development Goals. Natl Sci Rev 7:838–840. https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwaa048

Galvani A, Lew AA, Perez MS (2020) COVID-19 is expanding global consciousness and the sustainability of travel and tourism. Tour Geogr 22:567–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1760924

Hawkins RB, Charles EJ, Mehaffey JH (2020) Socio-economic status and COVID-19-related cases and fatalities. Public Health 189:129–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.09.016

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hua T, Zhao WW, Wang S et al. (2020) Identifying priority biophysical indicators for promoting food-energy-water nexus within planetary boundaries. Resour Conserv Recycl 163:105102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105102

Ibn-Mohammed T, Mustapha KB, Godsell J et al. (2021) A critical analysis of the impacts of COVID-19 on the global economy and ecosystems and opportunities for circular economy strategies. Resour Conserv Recycl 164:105169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105169

IPBES (2019) Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science–Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3553579 . Accessed 24 Apr 2022

Jean-Jacques M, Bauchner H (2021) Vaccine distribution-equity left behind? JAMA 325:829–830. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.1205

Kroll C, Warchold A, Pradhan P (2019) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): are we successful in turning trade-offs into synergies. Palgrave Commun 5:140. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0335-5

Le Quéré C, Jackson RB, Jones MW et al. (2020) Temporary reduction in daily global CO2 emissions during the COVID-19 forced confinement. Nat Clim Chang 10:647–653. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0797-x

Liu YL, Du JQ, Wang YF et al. (2021) Evenness is important in assessing progress towards sustainable development goals. Natl Sci Rev 8:nwaa238. https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwaa238

Lu YL, Nakicenovic N, Visbeck M et al. (2015) Five priorities for the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Nature 520:432–433. https://doi.org/10.1038/520432a

Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar

Lusseau D, Mancini F (2019) Income-based variation in Sustainable Development Goal interaction networks. Nat Sustain 2:242–247. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0231-4

Macedo MN, DeFries RS, Morton DC et al. (2012) Decoupling of deforestation and soy production in the southern Amazon during the late 2000s. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:1341–1346. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1111374109

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mach KJ, Kraan CM, Adger WN et al. (2019) Climate as a risk factor for armed conflict. Nature 571:193–197. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1300-6

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Naidoo R, Fisher B (2020) Sustainable Development Goals: pandemic reset. Nature 583:198–201. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01999-x

Nerini FF, Sovacool B, Hughes N et al. (2019) Connecting climate action with other Sustainable Development Goals. Nat Sustain 2:674–680. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0334-y

Nilsson M, Chisholm E, Griggs D et al. (2018) Mapping interactions between the sustainable development goals: lessons learned and ways forward. Sustain Sci 13:1489–1503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0604-z

O’Neill DW, Fanning AL, Lamb WF et al. (2018) A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nat Sustain 1:88–95. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0021-4

Olsen VM, Fensholt R, Olofsson P et al. (2021) The impact of conflict-driven cropland abandonment on food insecurity in South Sudan revealed using satellite remote sensing. Nat Food 2:990–996. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-021-00417-3

Osendarp S, Verburg G, Bhutta Z et al. (2022) Act now before Ukraine war plunges millions into malnutrition. Nature 604:620–624. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-01076-5

Pan SL, Zhang S (2020) From fighting COVID-19 pandemic to tackling sustainable development goals: an opportunity for responsible information systems research. Int J Inf Manag 55:102196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102196

Pradhan MR, Mondal S (2021) Pattern, predictors and clustering of handwashing practices in India. J Infect Prev 22:102–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757177420973754

Pradhan P (2019) Antagonists to meeting the 2030 Agenda. Nat Sustain 2:171–172. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0248-8

Pradhan P, Costa L, Rybski D et al. (2017) A systematic study of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) interactions. Earths Future 5:1169–1179. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017ef000632

Ranjbari M, Esfandabadi ZS, Zanetti MC et al. (2021) Three pillars of sustainability in the wake of COVID-19: a systematic review and future research agenda for sustainable development. J Clean Prod 297:126660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126660

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Roe D, Dickman A, Kock R et al. (2020) Beyond banning wildlife trade: COVID-19, conservation and development. World Dev 136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105121

Sachs J, Karim SA, Aknin L et al. (2020) Lancet COVID-19 Commission Statement on the occasion of the 75th session of the UN General Assembly. Lancet 396:1102–1124. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31927-9

Article CAS Google Scholar

Stephan RM, Mohtar RH, Daher B et al. (2018) Water–energy–food nexus: a platform for implementing the Sustainable Development Goals. Water Int 43:472–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2018.1446581

Stephens EC, Martin G, van Wijk M et al. (2020) Editorial: impacts of COVID-19 on agricultural and food systems worldwide and on progress to the sustainable development goals. Agric Syst 183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2020.102873

Swiss Re Institute (2019) Natural catastrophes and man-made disasters in 2018: “secondary” perils on the frontline. sigma. https://www.swissre.com/dam/jcr:c37eb0e4-c0b9-4a9f-9954-3d0bb4339bfd/sigma2_2019_en.pdf . Accessed 24 Apr 2022

UN (2015) Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://sdgs.un.org/publications/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development-17981 . Accessed 24 Apr 2022

UN (2020a) Shared responsibility, global solidarity: responding to the socio-economic impacts of COVID-19. https://unsdg.un.org/resources/shared-responsibility-global-solidarity-responding-socio-economic-impacts-covid-19?msclkid=f21129fec47a11ecabe177ea5cf4cc5f . Accessed 24 Apr 2022

UN (2020b) The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020. United Nations Publications, New York

Google Scholar

UN (2021a) The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2021. United Nations publications, New York

UN (2021b) The Sustainable Development Report 2021. Cambridge University Press, the UK

UNEP (2021) Making Peace with Nature—a scientific blueprint to tackle the climate, biodiversity and pollution emergencies. UNEP Secretariat, Nairobi. https://www.unep.org/gan/resources/report/making-peace-nature-scientific-blueprint-tackle-climate-biodiversity-and-pollution . Accessed 24 Apr 2022

Wang YC, Yuan JJ, Lu YL (2020) Constructing demonstration zones to promote the implementation of Sustainable Development Goals. Geogr Sustain 1:18–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geosus.2020.02.004

WHO (2022) WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard https://covid19.who.int/ . Accessed 24 Apr 2022

World Bank (2020) Poverty and shared prosperity 2020: reversals of fortune. World Bank, Washington, DC https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/poverty-and-shared-prosperity . Accessed 24 Apr 2022

World Economic Forum (2020) The Global Risks Report 2020. World Economic Forum, Geneva. https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-risks-report-2020 . Accessed 24 Apr 2022

Xu ZC, Chau SN, Chen XZ et al. (2020) Assessing progress towards sustainable development over space and time. Nature 577:74–78. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1846-3

Yang SQ, Zhao WW, Liu YX et al. (2020) Prioritizing sustainable development goals and linking them to ecosystem services: a global expert’s knowledge evaluation. Geogr Sustain 1:321–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geosus.2020.09.004

Yin CC, Zhao WW, Cherubini F et al. (2021) Integrate ecosystem services into socio-economic development to enhance achievement of sustainable development goals in the post-pandemic era. Geogr Sustain 2:68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geosus.2021.03.002

Yin CC, Pereira P, Hua T et al. (2022) Recover the food–energy–water nexus from COVID-19 under Sustainable Development Goals acceleration actions. Sci Total Environ 817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153013

Yin CC, Zhao WW, Pereira P (2022) Soil conservation service underpins sustainable development goals. Glob Ecol Conserv 33:8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01974

Zhang C, Cai WJ, Liu Z et al. (2020) Five tips for China to realize its co-targets of climate mitigation and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Geogr Sustain 1:245–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geosus.2020.09.001

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Science-based Advisory Program of the Academic Divisions of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, State Key Laboratory of Earth Surface Processes and Resource Ecology (2022-ZD-08), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China. The authors thank the editor and reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

State Key Laboratory of Earth Surface Processes and Resource Ecology, Faculty of Geographical Science, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China

Wenwu Zhao, Caichun Yin, Ting Hua, Yan Li, Yanxu Liu & Bojie Fu

Institute of Land Surface System and Sustainable Development, Faculty of Geographical Science, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China

Department of Environmental & Geographical Science, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, South Africa

Michael E. Meadows

School of Geographic and Ocean Sciences, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China

College of Environmental Sciences, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua, China

Industrial Ecology Program, Department of Energy and Process Engineering, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway

Francesco Cherubini

Environmental Management Center, Mykolas Romeris University, Vilnius, Lithuania

Paulo Pereira

State Key Laboratory of Urban and Regional Ecology, Research Center for Eco-Environmental Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Bojie Fu .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies requiring ethical approval.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary materials: achieving the sustainable development goals in the post-pandemic era, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Zhao, W., Yin, C., Hua, T. et al. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals in the post-pandemic era. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9 , 258 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01283-5

Download citation

Received : 13 February 2022

Accepted : 26 July 2022

Published : 06 August 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01283-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

The impact of covid-19 fiscal spending on climate change adaptation and resilience.

- Alexandra Sadler

- Nicola Ranger

- Brian O’Callaghan

Nature Sustainability (2024)

Characterization of Saponin Extracted from Acacia concinna (Shikakai or Soap Pod) and Thermodynamic Studies of Its Interaction with Organic Dye Rhodamine B

- Wasefa Begum

- Bidyut Saha

- Ujjwal Mandal

Chemistry Africa (2024)

Does banking sector support for achieving the sustainable development goals affect bank loan loss provisions? International evidence

- Peterson K. Ozili

Economic Change and Restructuring (2024)

Multi-way Analysis of the Gender Dimension of the Sustainable Development Goals

- Edith Johana Medina-Hernández

- María José Fernández-Gómez

Social Indicators Research (2024)

Assessing the sustainability of socio-economic boundaries in China: a downscaled “safe and just space” framework

- Qinglong Shao

npj Climate Action (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sustainable Development Goals

- All UCL SDG case studies

Case studies

Search here results.

- UCL students simulate UN SDG summit | Sustainable Development Goals - UCL – University College London

- UCL research helps shape international decarbonisation policy toolkit | Sustainable Development Goals - UCL – University College London

- Researchers at UCL review UK’s progress towards achieving the SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals - UCL – University College London

- Making UCL catering services more sustainable | Sustainable Development Goals - UCL – University College London

- UCL start-up takes ‘living walls’ to new level of sustainability | Sustainable Development Goals - UCL – University College London

- UCL undergraduates inspire more girls to keep up their football | Sustainable Development Goals - UCL – University College London

- New UCL master’s course to accelerate sustainable energy solutions | Sustainable Development Goals - UCL – University College London

- UCL student consultancy challenge boosts charity action towards the SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals - UCL – University College London

- Fourth Gold Athena Swan award recognises UCL’s commitment to equity and inclusion | Sustainable Development Goals - UCL – University College London

- New UCL MSc to equip ecologists with cutting-edge data science tools | Sustainable Development Goals - UCL – University College London

Please enable JavaScript to use this page or visit this page for a non javascript version.

Research outputs

View all UCL’s published research related to the SDGs.

View all SDG research →

About the UN's 17 SDGs

Simon Knowles Head of Coordination (SDGs) [email protected]

Sidebar Menu English

- About the SDG Fund

- Financial information

- How to partner

- Achieving SDGs

- Research and knowledge

- Final Evaluations

- Final Narrative Reports

- Sustainable cooking

- UN Joint Efforts

- National ownership

- Private Sector Advisory Group

- Business and SDG 16

- Universality and the SDGs

- Business and UN

- SDGF Framework of Engagement

- Creative Industries

- Aligning SDGs

- Matching funds

- South South Cooperation

- Architecture

- Digital Education

- Sustainability

- Gender mainstreaming

- Transparency

- Joint Programmes

- Selection process

- UN Agencies

- Private Sector

- Universities

- Case studies

Topbar Menu EN

Case Studies - Achieving SDGs

With this online database of sustainable development case studies, the SDG Fund has gathered a selection of best practices on “how” to achieve a sustainable world and advance the 17 Sustainable Development Goals.

The SDG Fund is a UN mechanism promoting partnerships between UN agencies, governments, academia, civil society and businesses to address the challenges of poverty and achieve the SDGs.

As part of its mission, the SDG Fund collects and disseminates insight for public and private entities worldwide interested in sustainable development, sharing lessons learned and best practices in its current and past development work. Most of these initial case studies come from previous experiences with the MDG Achievement Fund. New case studies will be added after the first round of joint programmes is concluded.

This series of case studies has been created to disseminate a robust evidence base on what implementing innovative development approaches actually means in practice. The case studies produced are concise, engaging, readable and equally appealing to practitioner and non-practitioner audiences. Users can search case studies by SDG or country. Each case study has a brief background of the situation, strategic approach, results and impact of the initiative, and a particular focus on challenges, lessons learned and potential for sustainability.

This project has been possible thanks to the support of the UN Volunteers programme, and particularly the writing, editing and translating work of the following volunteers: Lucy Oyelade, Judith McInally, Jamie Kadoglou, Nathan Weatherdon, Giovanni Avila Flores, Lorena Belenky, Beatriz Ruiz Espejel and Esperanza Escalona Reyes. The SDG Fund also thanks Samant Veer Kakkar and Rebeca Huete, for their work as consultants on this project. Funding has been provided by the Spanish Cooperation for International Cooperation (AECID).

A taste for transformation in Timor-Leste

Addressing Violence against women in Bangladesh

Bangladesh: Strengthening Women’s Ability For Productive New Opportunities (SWAPNO)

Better water and sanitation services through a consumer rights based contract in Albania

Bolivia: Improving the Nutritional Status of Children via the Strengthening of Local Production Systems

Building social capital to prevent violence in El Salvador

Business opportunities network in Panama

Colombia: Productive and Food Secure Territories for a Peaceful and Resilient Cauca

Côte D’Ivoire: Joint Programme on Poverty Reduction in San Pedro Region

Creative industries alleviate poverty in Peru

Cuba: Strenghtening the Resilience of Families and Vulnerable Groups affected by Drough in Santiago de Cuba

Economic opportunities and citizenship for women in extreme poverty in Bolivia

Ecuador: Strenghtening Local Food Systems and Capacity Building aimed at Improving the Production and Access to Safe Food for Families

El Salvador: Food Security and Nutrition for Children and Salvadoran Households (SANNHOS)

Energy efficiency and renewable energy sources in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Ethiopia: Joint Programme on Gender Equality and Women Empowerment – Rural Women Economic Empowerment Component

Fiji: Youth in Organic Agriculture in Fiji

Formulation of a localized customer service code in the Philippines

Gender mainstreaming in the Ministry of Culture in occupied Palestine territory

Gender mainstreaming strategy in the pro-poor horticulture value chain in Upper Egypt

Generating employment opportunities for young people in Honduras

Guatemala: Food and Nutrition Security of the Department of San Marcos

Harnessing the Opportunities of the New Economy in Mozambique: More and Better Jobs in Cabo Delgado and Nampula

Healthy children, healthy Afghanistan: best practices and lessons learned

Honduras: Culture and Tourism for Sustainable Local Development in Ruta Lenca

Indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities in the Chocó department promote their food security and nutrition in Colombia

Indigenous women participating in water management in Panama

Institutional strengthening against gender-based political violence in Bolivia

Institutional strengthening to improve food security and nutrition in El Salvador

Integrated Nutrition and Food Security Strategies for Children and Vulnerable Groups in Viet Nam

Irrigated and integrated agro production systems help Mozambique adapt to climate change

Lessons learned from the implementation of the joint programme on nutrition in Guinea-Bissau

Mauritania converts national policies into concrete action on natural resource management

Multi-disciplinary teams bring agricultural adaptation to climate change in China

Multi-sectoral programme for the fight against gender-based violence in Morocco

Nigeria: Food Africa – Empowering Youth and Promoting Innovative Public-Private Partnerships through More Efficient Agro-Food Value Chains in Nigeria

Occupied Palestinian Territory: A One-Stop-Shop for Sustainable Women-Owned Businesses

Paraguay: Joint Programme on Paraguay Protects, Promotes and Facilitates Effective Implementation of the Right to Food Security and Nutrition

Partnerships to combat malnutrition in Guatemala

Peace building for the displaced in Chiapas, Mexico

Peace-building in the department of Nariño in Colombia

Peru: Economic Inclusion and Sustainable Development of Andean Grain Producers in Ayacucho and Puno

Philippines: Pro-Water: Policies, Infrastructure and Behaviors for Improved Water and Sanitation

Planting Seeds of Change in Ethiopia

Productive cultural recovery on the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua

Regional action plan for youth employment in Tunisia

Samoa: Engaging Youth in Samoa in Organic Farming and Menus: A Farm to Table Value Chain Approach

Sierra Leone: Enabling Sustainable Livelihoods Through Improved Natural Resource Governance and Economic Diversification in the Kono District

Sri Lanka: Scaling Up Nutrition through a Multi-Sector Approach

Strengthening capacity to adapt to climate change in Turkey

Strengthening the institutional environment for the advancement of women in Guatemala

Strengthening the response to malnutrition in Bolivia

Sustainable urban development in El Salvador

Taking a value chain approach towards local economic development and women's economic empowerment in Vietnam

Tanzania: Joint Programme to Support Tanzania’s Productive Social Safety Net

The private sector as an agent of local development in Cuba

Water and sanitation management with a gender perspective in Mexico

Water governance in Ecuador

Women's empowerment through the promotion of cultural entrepreneurship in Cambodia

Women’s Participation in Stabilization and Conflict Prevention in North Kivu

Youth employment and migration in Costa Rica

Youth employment fund in Serbia

Youth in Organic Agriculture in Vanuatu

An initiative of

Useful links

Footer menu en.

- Publications

- Terms of use

Follow us on

British Council

Sustainable development goals (sdgs).

- What are the sustainable development goals?

SDG case studies

Following the SDGs exhibition of 2016, we commissioned an externally-led study to review evidence from a selection of programmes across the British Council's portfolio. This included three case studies to illustrate impact and lessons learned. As well as highlighting success and good practice, the case studies provide useful guidance for further development of programmes, in order to demonstrate contribution to the SDGs, as well as reinforcing the need for evidence of long-term impact.

The English for Education College Trainers (EfECT)

This project was initiated following a request from the Burmese government for support with its process of educational reform. The case study notes that the project was not designed using the SDG framework but Goal 4 underpins the British Council’s work in English and education in Burma.

This programme was started in Pakistan in 2013 and ran until April 2016. The name means ‘friendship’ in Urdu and Hindi but is also an acronym for Developing and Organising Social Transformation Initiatives. The project links football with personal and peace-building development training in which the lessons of the football pitch – teamwork, self-discipline, respect for others, tolerance – are inculcated, deepened and amplified. The case study notes that contribution to gender equality has been significant, breaking down traditional attitudes and empowering girls and young women.

Newton Fund

This case study looks at the way that the support of the Newton Fund – managed by the UK Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy – facilitated the creation of a network of researchers in Oxford and Mexico collaborating on a vaccine against Dengue Fever. Unlike the programmes featured in the other case studies, the SDGs were central to this programme, as the Newton Fund uses contributions to the SDGs as a criterion for assessing funding proposals. The case study notes that the requirement to demonstrate the relevance of their work to the SDGs was not seen as an imposition [by the team] but merely confirmed the implicit focus of their work.

British Council Worldwide

- Afghanistan

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Czech Republic

- Hong Kong, SAR of China

- Korea, Republic of

- Myanmar (Burma)

- Netherlands

- New Zealand

- North Macedonia

- Northern Ireland

- Occupied Palestinian Territories

- Philippines

- Saudi Arabia

- Sierra Leone

- South Africa

- South Sudan

- Switzerland

- United Arab Emirates

- United States of America

Publication

Engineering for sustainable development: delivering on the Sustainable Development Goals

It analyses the transformation of engineering education and capacity-building at the dawn of the Fourth Industrial Revolution that will enable engineers to tackle the challenges ahead. It highlights the global effort needed to address the specific regional disparities, while summarizing the trends of engineering across the different regions of the world.

By presenting case studies and approaches, as well as possible solutions, the report reveals why engineering is crucial for sustainable development and why the role of engineers is vital in addressing basic human needs such as alleviating poverty, supplying clean water and energy, responding to natural disasters, constructing resilient infrastructure, and bridging the development divide, among many other actions, leaving no one behind.

It is hoped that the report will serve as a reference for governments, engineering organizations, academia and educational institutions, and industry to forge global partnerships and catalyse collaboration in engineering so as to deliver on the SDGs.

More information

Related items.

- Natural sciences

- Engineering

- Engineering education

- Science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM)

Other recent publications

Your browser is not supported

Sorry but it looks as if your browser is out of date. To get the best experience using our site we recommend that you upgrade or switch browsers.

Find a solution

We use cookies to improve your experience on this website. To learn more, including how to block cookies, read our privacy policy .

- Skip to main content

- Skip to navigation

- Collaboration Platform

- Data Portal

- Reporting Tool

- PRI Academy

- PRI Applications

- Back to parent navigation item

- What are the Principles for Responsible Investment?

- PRI 2021-24 strategy

- The PRI work programme

- A blueprint for responsible investment

- About the PRI

- Annual report

- Public communications policy

- Financial information

- Procurement

- PRI sustainability

- Diversity, Equity & Inclusion for our employees

- Meet the team

- Board members

- Board committees

- 2023 PRI Board annual elections

- Signatory General Meeting (SGM)

- Signatory rights

- Serious violations policy

- Formal consultations

- Signatories

- Signatory resources

- Become a signatory

- Get involved

- Signatory directory

- Quarterly signatory update

- Multi-lingual resources

- Espacio Hispanohablante

- Programme Francophone

- Reporting & assessment

- R&A Updates

- Public signatory reports

- Progression pathways

- Showcasing leadership

- The PRI Leaders’ Group

- The PRI Awards

- News & events

- The PRI podcast

- News & press

- Upcoming events

- PRI in Person 2024

- All events & webinars

- Industry events

- Past events

- PRI in Person 2023 highlights

- PRI in Person & Online 2022 highlights

- PRI China Conference: Investing for Net-Zero and SDGs

- PRI Digital Forums

- Webinars on demand

- Investment tools

- Introductory guides to responsible investment

- Principles to Practice

- Stewardship

- Collaborative engagements

- Active Ownership 2.0

- Listed equity

- Passive investments

- Fixed income

- Credit risk and ratings

- Private debt

- Securitised debt

- Sovereign debt

- Sub-sovereign debt

- Private markets

- Private equity

- Real estate

- Climate change for private markets

- Infrastructure and other real assets

- Infrastructure

- Hedge funds

- Investing for nature: Resource hub

- Asset owner resources

- Strategy, policy and strategic asset allocation

- Mandate requirements and RfPs

- Manager selection

- Manager appointment

- Manager monitoring

- Asset owner DDQs

- Sustainability issues

- Environmental, social and governance issues

- Environmental issues

- Circular economy

- Social issues

- Social issues - case studies

- Social issues - podcasts

- Social issues - webinars

- Social issues - blogs

- Cobalt and the extractives industry

- Clothing and Apparel Supply Chain

- Human rights

- Human rights - case studies

- Modern slavery and labour rights

- Just transition

- Governance issues

- Tax fairness

- Responsible political engagement

- Cyber security

- Executive pay

- Corporate purpose

- Anti-corruption

- Whistleblowing

- Director nominations

- Climate change

- The PRI and COP28

- Inevitable Policy Response

- UN-convened Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance

- Sustainability outcomes

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Sustainable markets

- Sustainable financial system

- Driving meaningful data

- Private retirement systems and sustainability

- Academic blogs

- Academic Seminar series

- Introduction to responsible investing academic research

- Our policy approach

- Policy reports

- Consultations and letters

- Global policy

- Policy toolkit

- Policy engagement handbook

- Regulation database

- A Legal Framework for Impact

- Fiduciary duty

- Australia policy

- Canada Policy

- China policy

- Stewardship in China

- EU taxonomy

- Japan policy

- SEC ESG-Related Disclosure

- More from navigation items

Global Impact Partners SDG case study

2020-07-27T07:10:00+01:00

Signatory type: Service provider (investment advisory) Operating region: Asia Pacific Practice area: Engagement and investment decisions

Global Impact Partners advises governments, corporations, and non-profits on strategy and impact investment. We collaborate with clients who are contributing towards achieving the SDGs within sectors such as infrastructure and urban development, healthcare, sustainable technology and sustainable agriculture.

Why we focus on the SDGS

The SDGs naturally align with our ethos and provide a framework to guide project selection and indicators to measure impact. We have integrated the goals into our primary ESG framework because their ratification in 2015 reflects a broad-based global consensus on the world’s most pressing environmental and social challenges. In the case of infrastructure and urban development, for example, we believe that the SDGs can provide a frame through which to identify and address the environmental challenges created by unchecked urbanisation.

We believe that applying SDG-based performance targets to projects, through the use of onsite renewable energy generation and smart grids, for example, can directly reduce the operational expenditure of the assets, demonstrating the alignment of the SDGs with commercial objectives. Taking this detailed approach, we can guide infrastructure project design teams in making changes that will optimise the sustainable and commercial outcomes of the project.

Measuring project outcomes

We take a bottom-up, indicator-driven approach to assessing the outcomes from projects. Working with the master-planning and engineering teams during the design phase of infrastructure projects, we can optimise their designs to deliver outcomes which contribute towards the SDGs. In selecting relevant indicators, we use the SDG Impact Indicators guidance published by the Sustainable Finance Platform, chaired by the Dutch Central Bank, which aims to develop “a common set of impact indicators [to] help companies to improve the disclosure of impact data to their shareholders and creditors” 1 . We evaluate which indicators are relevant, taking into account the potential for positive and negative outcomes from the project, and select those which we believe we can most influence.