Freedom Riders

Written by: Bill of Rights Institute

By the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain how and why various groups responded to calls for the expansion of civil rights from 1960 to 1980

Suggested Sequencing

Use this narrative with The March on Birmingham Narrative; the Black Power Narrative; the Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” 1963 Primary Source; the Martin Luther King Jr., “I Have a Dream,” August 28, 1963 Primary Source; the Civil Disobedience across Time Lesson; the The Music of the Civil Rights Movement Lesson; and the Civil Rights DBQ Lesson to discuss the different aspects of the civil rights movement during the 1960s.

After World War II, the civil rights movement sought equal rights and integration for African Americans through a combination of federal action and local activism. One specific area the movement attempted to change was the segregation of interstate travel. In Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia (1946), the Supreme Court had ruled that segregated seating on interstate buses was unconstitutional, but the ruling was largely ignored in southern states.

In 1960, the Supreme Court followed up on its earlier decision and ordered the integration of interstate buses and terminals. In 1961, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), which had been formed in 1942, appointed a new national director, James Farmer. Farmer’s idea for a freedom ride to desegregate interstate buses was inspired by the college students who had launched the recent spontaneous and nonviolent sit-ins to desegregate lunch counters, starting in Greensboro, North Carolina. These sit-ins had soon spread to 100 cities across the South. Farmer decided to have an interracial group ride the buses from Washington, DC, to New Orleans to commemorate the anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education case.

James Farmer was a leader in the civil rights movement and, in 1961, helped organize the first freedom ride.

Members of CORE sent letters to President Kennedy, his brother Attorney General Robert Kennedy, Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) director J. Edgar Hoover, the chair of the Interstate Commerce Commission, and the president of the Greyhound Corporation announcing their intentions to make the ride and hoping for protection. CORE decided to move forward despite receiving no response.

The 13 recruits underwent three days of intensive training in the philosophy of nonviolence, role playing the difficult situations they could expect to encounter. On May 4, 1961, six of the riders boarded a Greyhound bus and seven took a Trailways bus, planning to ride to New Orleans. The riders knew they would face racial epithets, violence, and possibly death. They hoped they had the courage to face the trial nonviolently in their fight for equality.

The riders challenged the segregated bus seating, with black participants riding in the “white” sections and riders of both races using segregated lunch counters and restrooms in the Virginia cities of Fredericksburg, Richmond, Farmville, and Lynchburg, but no one seemed to care. After they crossed into North Carolina, one of the black riders was arrested trying to get a shoeshine at a whites-only chair in Charlotte but was soon released. The group faced physical violence for the first time in Rock Hill, South Carolina: John Lewis, a black college student; Albert Bigelow, an older white activist; and Genevieve Hughes, a young white woman, were all assaulted before they were rushed to safety by a local black pastor. Two more riders were arrested and released in Winnsboro, and two riders had to interrupt the ride for other commitments, but four new riders joined.

On May 6, while the rides continued, the attorney general delivered a major civil rights address promising that the Kennedy administration would enforce civil rights laws. Though he seemed more concerned with America’s image abroad during the Cold War, he stated that the administration “will not stand by and be aloof.” The freedom rides presented an opportunity for the attorney general to fulfill that promise.

Attorney General Robert Kennedy was a supporter of enforcing federal civil rights laws. He spoke to CORE in 1963, outside the Justice Department in Washington, DC.

In Augusta and Atlanta, Georgia, the riders ate at desegregated lunch counters and sat in desegregated waiting rooms. They were discovering that different communities throughout several southern states had different racial mores. They met with Martin Luther King Jr., who shared intelligence he had about impending violence in Alabama. A Birmingham police sergeant, Tom Cook, and the public safety commissioner, Bull Connor, were in league with the local Ku Klux Klan (KKK), which was planning a violent reception for the riders in that city. Cook and Connor had agreed that the mob could beat the riders for about 15 minutes before they would send the police and make a show of restoring order. The FBI had informed the attorney general, but neither acted to protect the riders or even to inform them of what awaited them.

The Greyhound bus departed Atlanta on the morning of May 14. The first group reached a stop in Anniston, Alabama, where an angry mob of whites armed with guns, bats, and brass knuckles surrounded the bus. Two undercover Alabama Highway Patrol officers on the bus quickly locked the doors, but members of the crowd smashed its windows. The Anniston police temporarily restored order and the bus left, trailed by 30 to 40 cars that then surrounded it and forced it to stop. Suddenly, a member of the crowd hurled flaming rags into the bus, and it exploded into flames. The riders climbed out through windows and the doors, barely escaping with their lives. The mob assaulted them and used a baseball bat on the skull of a young black male, Hank Thomas, before an undercover officer fired his gun into the air and a fuel tank exploded, dispersing the crowd. The riders went to the hospital, where they were refused care and were driven in activists’ cars to Birmingham.

A Greyhound bus carrying freedom riders was firebombed by an angry mob while in Anniston, Alabama, in 1961. Forced to evacuate, the passengers were then assaulted. (credit: “Freedom Riders Bus Attack” by Federal Bureau of Investigation)

The riders on the Trailways bus were terrorized by KKK hoodlums who boarded in Atlanta. At first, the white supremacists merely taunted the riders with warnings about the violence that awaited them in Birmingham, but when the riders sat in the white section of the bus, horrific violence erupted. Two riders were punched in the face and knocked to the floor where they were repeatedly kicked and beaten into unconsciousness. Two other riders tried to intervene peacefully and suffered the same fate. They were dragged to the back of the bus and dumped there.

Bull Connor carried out his plan not to post officers at the Birmingham bus station, with the excuse that it was Mother’s Day. Consequently, another large mob awaited the riders and forced them off the bus and assaulted them. Riders Ike Reynolds and Charles Person were knocked down and bloodied by a series of vicious blows. An older white rider, Jim Peck, was struck in the head several times, opening a wound that required 53 stitches. Peck later told a reporter that he endured the violence courageously to “show that nonviolence can prevail over violence.” The police finally showed up after the allotted 15 minutes but made no arrests. Other riders escaped, and they all met at Reverend Fred Shuttleworth’s church.

Americans across the country learned about the violence as the images of burning buses and beaten riders were broadcast on television and printed in newspapers. President Kennedy was preparing for a foreign summit and wanted the freedom riders to stop causing controversy. Attorney General Kennedy tried to persuade the Alabama governor, John Patterson, to protect the riders but was frustrated in the attempt. Also exasperated by Greyhound’s unwillingness to provide a new bus for the riders, the attorney general sent one federal official, John Seigenthaler, to the riders in Birmingham.

The riders planned to go to Montgomery and continue to New Orleans but could not find a bus. They reluctantly settled on flying to their final destination but had to wait out bomb threats before quietly boarding a flight. Although the CORE freedom ride was over, Diane Nash, a black student at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, was inspired by their example. She coordinated additional freedom rides to desegregate interstate travel, which immediately proceeded from Nashville to Birmingham to finish the ride.

On Wednesday, the new group of riders were met at the Birmingham terminal by the police, who quickly arrested them. The riders went on a hunger strike in jail and were dumped on the side of the road more than 100 miles away in Tennessee before sunrise on Friday. However, they simply drove back to Birmingham, where they attempted to board a bus for Montgomery, but the terrified driver refused to let them on. The Kennedy administration negotiated a settlement in which the state police were to protect the bus bound for Montgomery.

The bus pulled into the Birmingham station, but the police cars disappeared. The freedom riders faced another horrendous scene: a crowd armed with bricks, pipes, baseball bats, and sticks yelling death threats. A young white man, Jim Zwerg, stepped off the bus first and was dragged down into the mob and knocked unconscious. Two female riders were pummeled, one by a woman swinging a purse and repeatedly hitting her in the head, the other by a man punching her repeatedly in the face.

Seigenthaler attempted to rescue the women by putting them into his car and driving away, but he was dragged from the car and knocked unconscious with a pipe and kicked in the ribs. A young black rider, William Barbee, was beaten into submission with a baseball bat and suffered permanent brain damage. A black bystander was even set afire after having kerosene thrown on him. The mayhem ended when a state police officer fired warning shots into the ceiling of the station. All the riders needed medical attention and were rushed to a local hospital.

That night, Martin Luther King Jr. came to Montgomery. Protected by a ring of federal marshals, King addressed a mass rally at First Baptist Church. He told the assembly, “Alabama will have to face the fact that we are determined to be free. The main thing I want to say to you is fear not, we’ve come too far to turn back . . . We are not afraid and we shall overcome.” Meanwhile, a white riot had erupted outside the church, and congregants spent the night inside.

A compromise was worked out two days later to get the riders out of Alabama and send them to Mississippi. A total of 27 freedom riders boarded the buses safely, accompanied by the Alabama National Guard, which, to the riders, defeated the purpose of challenging segregated seating on the bus. They were all arrested in Jackson in the bus depot for violating segregation statutes and were taken to jail. In the coming weeks, additional rides were made, but all suffered the same fate and more than 80 riders landed in jail under deplorable conditions.

Freedom riders Priscilla Stephens, from CORE, and Reverend Petty D. McKinney, from Nyack, New York, are shown after their arrest by the police in Tallahassee, Florida, in June 1961.

During the summer, the national media and many Americans lost interest in the freedom rides. A Gallup Poll in mid-June showed that a majority of Americans supported desegregated interstate travel and the use of federal marshals to enforce it. However, 64 percent of Americans disapproved of the rides after initial expressions of sympathy, and 61 percent thought civil rights should be achieved gradually instead of through direct action.

The civil rights movement was undeterred by such popular opinion. The 1960 Greensboro sit-ins and the 1961 freedom rides created a new momentum in the struggle for equal rights and freedom. Over the next few years, civil rights activists directly confronted segregation through nonviolent tactics at places like Birmingham and Selma to arouse the national conscience and to pressure the federal government for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Review Questions

1. The freedom rides in 1961 were most directly inspired by

- the lunch counter sit-ins started in Greensboro, North Carolina

- the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education

- the Supreme Court’s decision in Morgan v. Commonwealth

- the formation of the Congress of Racial Equality

2. Freedom riders from the early 1960s were best known for

- inciting violent protests against urban policing policies

- providing transportation to those participating in the Montgomery bus boycott

- boycotting travel on segregated buses across the South

- challenging segregated seating on interstate bus routes

3. Response to the freedom riders as they travelled throughout the South illustrated

- uniformly violent opposition to their actions

- varied racial attitudes and reactions on the part of southerners

- widespread indifference

- local support and public mobilization of the black community

4. The freedom riders encountered the most violent reactions to their methods in

- Lynchburg, Virginia

- Charlotte, North Carolina

- Atlanta, Georgia

- Birmingham, Alabama

5. The federal government’s response to the freedom rides was characterized generally by

- overwhelming support, including federal protection of the riders

- the full support of Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy and President John F. Kennedy, but not of Congress

- observation and information gathering but limited actual support

- official training in nonviolent tactics but little overt support

6. Compared with earlier tactics in the movement, in the early 1960s, new civil rights groups advocated greater emphasis on

- taking direct action

- working through the federal court system

- inciting violent revolution

- electing local officials sympathetic to their cause

7. The actions of the freedom riders most directly contributed to the

- Brown v. Board of Education decision

- Civil Rights Act of 1964

- Voting Rights Act of 1965

- election of President John F. Kennedy

Free Response Questions

- Explain how the freedom riders of the early 1960s drew upon the U.S. Constitution to justify their actions.

- Explain how the freedom rides of the early 1960s represented an evolution in the methods of the civil rights movement.

AP Practice Questions

1. The events in the image most directly led to

- a Supreme Court decision declaring segregation unconstitutional

- increased support for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

- the development of the counterculture

- Martin Luther King Jr.’s becoming a civil rights leader

2. The event in the photograph contributed to which of the following?

- Debates over the role of government in American life

- An increase in public confidence in political institutions

- Domestic opposition to containment

- The abandonment of direct-action techniques to achieve civil rights

3. The event in the image was most directly shaped by

- the techniques and strategies of the anti-war movement

- desegregation of the armed forces

- a desire to achieve the promise of the Fourteenth Amendment

- Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society program

Primary Sources

James Farmer: letters to President John Kennedy. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum . 1961. https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/education/students/leaders-in-the-struggle-for-civil-rights/james-farmer

Suggested Resources

Arsenault, Raymond. Freedom Rides: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-1963 . New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988.

Chafe, William. Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina, and the Black Struggle for Freedom . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980.

Dudziak, Mary L. Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Graham, Hugh Davis. The Civil Rights Era: Origins and Development of National Policy . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Lawson, Stephen F., and Charles Payne. Debating the Civil Rights Movement, 1945-1968 . Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 1998.

Salmond, John A. “My Mind Set on Freedom:” A History of the Civil Rights Movement, 1954-1968 . Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1997.

Stern, Mark. Calculating Visions: Kennedy, Johnson, and Civil Rights . New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1992.

Related Content

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness

In our resource history is presented through a series of narratives, primary sources, and point-counterpoint debates that invites students to participate in the ongoing conversation about the American experiment.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Freedom Riders

By: History.com Editors

Updated: January 20, 2022 | Original: February 2, 2010

Freedom Riders were groups of white and African American civil rights activists who participated in Freedom Rides, bus trips through the American South in 1961 to protest segregated bus terminals. Freedom Riders tried to use “whites-only” restrooms and lunch counters at bus stations in Alabama, South Carolina and other Southern states. The groups were confronted by arresting police officers—as well as horrific violence from white protestors—along their routes, but also drew international attention to the civil rights movement.

Civil Rights Activists Test Supreme Court Decision

The 1961 Freedom Rides, organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) , were modeled after the organization’s 1947 Journey of Reconciliation. During the 1947 action, African American and white bus riders tested the 1946 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Morgan v. Virginia that found segregated bus seating was unconstitutional.

The 1961 Freedom Rides sought to test a 1960 decision by the Supreme Court in Boynton v. Virginia that segregation of interstate transportation facilities, including bus terminals, was unconstitutional as well. A big difference between the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation and the 1961 Freedom Rides was the inclusion of women in the later initiative.

In both actions, Black riders traveled to the Jim Crow South—where segregation continued to occur—and attempted to use whites-only restrooms, lunch counters and waiting rooms.

The original group of 13 Freedom Riders—seven African Americans and six whites—left Washington, D.C. , on a Greyhound bus on May 4, 1961. Their plan was to reach New Orleans , Louisiana , on May 17 to commemorate the seventh anniversary of the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision, which ruled that segregation of the nation’s public schools was unconstitutional.

The group traveled through Virginia and North Carolina , drawing little public notice. The first violent incident occurred on May 12 in Rock Hill, South Carolina . John Lewis , an African American seminary student and member of the SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), white Freedom Rider and World War II veteran Albert Bigelow and another Black rider were viciously attacked as they attempted to enter a whites-only waiting area.

The next day, the group reached Atlanta, Georgia , where some of the riders split off onto a Trailways bus.

Did you know? John Lewis, one of the original group of 13 Freedom Riders, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in November 1986. Lewis, a Democrat, continued to represent Georgia's 5th Congressional District, which includes Atlanta, until his death in 2020.

Freedom Riders Face Bloodshed in Alabama

On May 14, 1961, the Greyhound bus was the first to arrive in Anniston, Alabama . There, an angry mob of about 200 white people surrounded the bus, causing the driver to continue past the bus station.

The mob followed the bus in automobiles, and when the tires on the bus blew out, someone threw a bomb into the bus. The Freedom Riders escaped the bus as it burst into flames, only to be brutally beaten by members of the surrounding mob.

The second bus, a Trailways vehicle, traveled to Birmingham, Alabama, and those riders were also beaten by an angry white mob, many of whom brandished metal pipes. Birmingham Public Safety Commissioner Bull Connor stated that, although he knew the Freedom Riders were arriving and violence awaited them, he posted no police protection at the station because it was Mother’s Day .

Photographs of the burning Greyhound bus and the bloodied riders appeared on the front pages of newspapers throughout the country and around the world the next day, drawing international attention to the Freedom Riders’ cause and the state of race relations in the United States.

Following the widespread violence, CORE officials could not find a bus driver who would agree to transport the integrated group, and they decided to abandon the Freedom Rides. However, Diane Nash , an activist from the SNCC, organized a group of 10 students from Nashville, Tennessee , to continue the rides.

U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy , brother of President John F. Kennedy , began negotiating with Governor John Patterson of Alabama and the bus companies to secure a driver and state protection for the new group of Freedom Riders. The rides finally resumed, on a Greyhound bus departing Birmingham under police escort, on May 20.

Federal Marshals Called In

The violence toward the Freedom Riders was not quelled—rather, the police abandoned the Greyhound bus just before it arrived at the Montgomery, Alabama, terminal, where a white mob attacked the riders with baseball bats and clubs as they disembarked. Attorney General Kennedy sent 600 federal marshals to the city to stop the violence.

The following night, civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr . led a service at the First Baptist Church in Montgomery, which was attended by more than one thousand supporters of the Freedom Riders. A riot ensued outside the church, and King called Robert Kennedy to ask for protection.

Kennedy summoned the federal marshals, who used tear gas to disperse the white mob. Patterson declared martial law in the city and dispatched the National Guard to restore order.

Kennedy Urges ‘Cooling Off’ Period

On May 24, 1961, a group of Freedom Riders departed Montgomery for Jackson, Mississippi . There, several hundred supporters greeted the riders. However, those who attempted to use the whites-only facilities were arrested for trespassing and taken to the maximum-security penitentiary in Parchman, Mississippi.

That same day, U.S. Attorney General Kennedy issued a statement urging a “cooling off” period in the face of the growing violence:

“A very difficult condition exists now in the states of Mississippi and Alabama. Besides the groups of 'Freedom Riders' traveling through these states, there are curiosity seekers, publicity seekers and others who are seeking to serve their own causes, as well as many persons who are traveling because they must use the interstate carriers to reach their destination.

In this confused situation, there is increasingly possibility that innocent persons may be injured. A mob asks no questions.

A cooling off period is needed. It would be wise for those traveling through these two Sites to delay their trips until the present state of confusion and danger has passed and an atmosphere of reason and normalcy has been restored.”

During the Mississippi hearings, the judge turned and looked at the wall rather than listen to the Freedom Riders’ defense—as had been the case when sit-in participants were arrested for protesting segregated lunch counters in Tennessee. He sentenced the riders to 30 days in jail.

Attorneys from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People ( NAACP ), a civil rights organization, appealed the convictions all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court , which reversed them.

Desegregating Travel

The violence and arrests continued to garner national and international attention, and drew hundreds of new Freedom Riders to the cause.

The rides continued over the next several months, and in the fall of 1961, under pressure from the Kennedy administration, the Interstate Commerce Commission issued regulations prohibiting segregation in interstate transit terminals.

HISTORY Vault: Voices of Civil Rights

A look at one of the defining social movements in U.S. history, told through the personal stories of men, women and children who lived through it.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Freedom Rides

May 4, 1961 to December 16, 1961

During the spring of 1961, student activists from the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) launched the Freedom Rides to challenge segregation on interstate buses and bus terminals. Traveling on buses from Washington, D.C., to Jackson, Mississippi, the riders met violent opposition in the Deep South, garnering extensive media attention and eventually forcing federal intervention from John F. Kennedy ’s administration. Although the campaign succeeded in securing an Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) ban on segregation in all facilities under their jurisdiction, the Freedom Rides fueled existing tensions between student activists and Martin Luther King, Jr., who publicly supported the riders, but did not participate in the campaign.

The Freedom Rides were first conceived in 1947 when CORE and the Fellowship of Reconciliation organized an interracial bus ride across state lines to test a Supreme Court decision that declared segregation on interstate buses unconstitutional. Called the Journey of Reconciliation, the ride challenged bus segregation in the upper parts of the South, avoiding the more dangerous Deep South. The lack of confrontation, however, resulted in little media attention and failed to realize CORE’s goals for the rides. Fourteen years later, in a new national context of sit-ins , boycotts, and the emergence of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Freedom Rides were able to harness enough national attention to force federal enforcement and policy changes.

Following an earlier ruling, Morgan v. Virginia (1946), that made segregation in interstate transportation illegal, in 1960 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Boynton v. Virginia that segregation in the facilities provided for interstate travelers, such as bus terminals, restaurants, and restrooms, was also unconstitutional. Prior to the 1960 decision, two students, John Lewis and Bernard Lafayette , integrated their bus ride home from college in Nashville, Tennessee, by sitting at the front of a bus and refusing to move. After this first ride, they saw CORE’s announcement recruiting volunteers to participate in a Freedom Ride, a longer bus trip through the South to test the enforcement of Boynton . Lafayette’s parents would not permit him to participate, but Lewis joined 12 other activists to form an interracial group that underwent extensive training in nonviolent direct action before launching the ride.

On 4 May 1961, the freedom riders left Washington, D.C., in two buses and headed to New Orleans. Although they faced resistance and arrests in Virginia, it was not until the riders arrived in Rock Hill, South Carolina, that they encountered violence. The beating of Lewis and another rider, coupled with the arrest of one participant for using a whites-only restroom, attracted widespread media coverage. In the days following the incident, the riders met King and other civil rights leaders in Atlanta for dinner. During this meeting, King whispered prophetically to Jet reporter Simeon Booker, who was covering the story, “You will never make it through Alabama” (Lewis, 140).

The ride continued to Anniston, Alabama, where, on 14 May, riders were met by a violent mob of over 100 people. Before the buses’ arrival, Anniston local authorities had given permission to the Ku Klux Klan to strike against the freedom riders without fear of arrest. As the first bus pulled up, the driver yelled outside, “Well, boys, here they are. I brought you some niggers and nigger-lovers” (Arsenault, 143). One of the buses was firebombed, and its fleeing passengers were forced into the angry white mob. The violence continued at the Birmingham terminal where Eugene “Bull” Connor ’s police force offered no protection. Although the violence garnered national media attention, the series of attacks prompted James Farmer of CORE to end the campaign. The riders flew to New Orleans, bringing to an end the first Freedom Ride of the 1960s.

The decision to end the ride frustrated student activists, such as Diane Nash , who argued in a phone conversation with Farmer: “We can’t let them stop us with violence. If we do, the movement is dead” (Ross, 177). Under the auspices and organizational support of SNCC, the Freedom Rides continued. SNCC mentors were wary of this decision, including King, who had declined to join the rides when asked by Nash and Rodney Powell. Farmer continued to express his reservations, questioning whether continuing the trip was “suicide” (Lewis, 144). With fractured support, the organizers had a difficult time securing financial resources. Nevertheless, on 17 May 1961, seven men and three women rode from Nashville to Birmingham to resume the Freedom Rides. Just before reaching Birmingham, the bus was pulled over and directed to the Birmingham station, where all of the riders were arrested for defying segregation laws. The arrests, coupled with the difficulty of finding a bus driver and other logistical challenges, left the riders stranded in the city for several days.

Federal intervention began to take place behind the scenes as Attorney General Robert Kennedy called the Greyhound Company and demanded that it find a driver. Seeking to diffuse the dangerous situation, John Seigenthaler, a Department of Justice representative accompanying the freedom riders, met with a reluctant Alabama Governor John Patterson . Seigenthaler’s maneuver resulted in the bus’s departure for Montgomery with a full police escort the next morning.

At the Montgomery city line, as agreed, the state troopers left the buses, but the local police that had been ordered to meet the freedom riders in Montgomery never appeared. Unprotected when they entered the terminal, riders were beaten so severely by a white mob that some sustained permanent injuries. When the police finally arrived, they served the riders with an injunction barring them from continuing the Freedom Ride in Alabama.

During this time, King was on a speaking tour in Chicago. Upon learning of the violence, he returned to Montgomery, where he staged a rally at Ralph Abernathy ’s First Baptist Church. In his speech, King blamed Governor Patterson for “aiding and abetting the forces of violence” and called for federal intervention, declaring that “the federal government must not stand idly by while bloodthirsty mobs beat nonviolent students with impunity” (King, 21 May 1961). As King spoke, a threatening white mob gathered outside. From inside the church, King called Attorney General Kennedy, who assured him that the federal government would protect those inside the church. Kennedy swiftly mobilized federal marshals who used tear gas to keep the mob at bay. Federal marshals were later replaced by the Alabama National Guard, who escorted people out of the church at dawn.

As the violence and federal intervention propelled the freedom riders to national prominence, King became one of the major spokesmen for the rides. Some activists, however, began to criticize King for his willingness to offer only moral and financial support but not his physical presence on the rides. In a telegram to King the president of the Union County National Association for the Advancement of Colored People branch in North Carolina, Robert F. Williams , urged him to “lead the way by example.… If you lack the courage, remove yourself from the vanguard” ( Papers 7:241–242 ). In response to Nash’s direct request that King join the rides, King replied that he was on probation and could not afford another arrest, a response many of the students found unacceptable.

On 29 May 1961, the Kennedy administration announced that it had directed the ICC to ban segregation in all facilities under its jurisdiction, but the rides continued. Students from all over the country purchased bus tickets to the South and crowded into jails in Jackson, Mississippi. With the participation of northern students came even more press coverage. On 1 November 1961, the ICC ruling that segregation on interstate buses and facilities was illegal took effect.

Although King’s involvement in the Freedom Rides waned after the federal intervention, the legacy of the rides remained with him. He, and all others involved in the campaign, saw how provoking white southern violence through nonviolent confrontations could attract national attention and force federal action. The Freedom Rides also exposed tactical and leadership rifts between King and more militant student activists, which continued until King’s death in 1968.

Arsenault, Freedom Riders , 2006.

“Bi-Racial Group Cancels Bus Trip,” New York Times , 16 May 1961.

Carson, In Struggle , 1981.

Garrow, Bearing the Cross , 1986.

King, Statement Delivered at Freedom Riders Rally at First Baptist Church, 21 May 1961, MMFR .

Lewis, Walking with the Wind , 1998.

Peck, Freedom Ride , 1962.

Ross, Witnessing and Testifying , 2003.

Williams to King, 31 May 1961, in Papers 7:241–242 .

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Who Were the Freedom Riders?

Representative John Lewis was among the 13 original Freedom Riders, who encountered violence and resistance as they rode buses across the South, challenging the nation’s segregation laws.

By Derrick Bryson Taylor

Representative John Lewis, who died on Friday at 80 , was an imposing figure in American politics and the civil rights movement. But his legacy of confronting racism directly, while never swaying from his commitment to nonviolence, started long before he became a national figure.

Mr. Lewis, a Georgia Democrat, was among the original 13 Freedom Riders who rode buses across the South in 1961 to challenge segregation in public transportation. The riders were attacked and beaten, and one of their buses was firebombed, but the rides changed the way people traveled and set the stage for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

How did the Freedom Rides start?

In 1947, the Congress of Racial Equality, known as CORE, created a “Journey of Reconciliation” to draw attention to racial segregation in public transportation in Southern cities and states across the United States. That movement was only moderately successful, but it led to the Freedom Rides of 1961, which forever changed the way Americans traveled between states.

The Freedom Rides, which began in May 1961 and ended late that year, were organized by CORE’s national director, James Farmer. The mission of the rides was to test compliance with two Supreme Court rulings: Boynton v. Virginia, which declared that segregated bathrooms, waiting rooms and lunch counters were unconstitutional, and Morgan vs. Virginia, in which the court ruled that it was unconstitutional to implement and enforce segregation on interstate buses and trains. The Freedom Rides took place as the Civil Rights movement was gathering momentum, and during a period in which African-Americans were routinely harassed and subjected to segregation in the Jim Crow South.

Who were the first 13 Freedom Riders?

The original Freedom Riders were 13 Black and white men and women of various ages from across the United States.

Raymond Arsenault, a Civil Rights historian and the author “ Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice ,” said CORE had advertised for participants and asked for applications. “They wanted a geographic distribution and age distribution,” he said.

Among those chosen were the Rev. Benjamin Elton Cox , a minister from High Point, N.C., and Charles Person of Atlanta, then a freshman at Morehouse College in Atlanta, who was the youngest of the group at 18. “They had antinuclear activists; they had a husband-and-wife team from Michigan,” Mr. Arsenault said of the diverse group of participants.

Mr. Lewis, then 21, represented the Nashville movement, which staged demonstrations at department stores and sit-ins at lunch counters. But Mr. Lewis nearly missed his opportunity, according to his 1998 autobiography, “Walking With the Wind.” After receiving his bus ticket to Washington, D.C., from CORE, Mr. Lewis was driven to the bus station by two friends, James Bevel and Bernard Lafayette. He arrived to find that his scheduled bus had already departed. “We threw my bag back in Bevel’s car, floored it east and caught up in Murfreesboro,” Mr. Lewis said.

The original group completed a few days of training in Washington, Mr. Arsenault said, preparing by role-playing to respond in nonviolent ways to the harassment that they would endure.

As the movement grew, so did the number of participants. Later in May, in Jackson, Miss., Mr. Lewis and hundreds of other protesters were arrested and hastily convicted of breach of peace. Many of the Freedom Riders spent six weeks in prison, sweltering in filthy, vermin-infested cells.

What was the first ride like?

On May 4, 1961, the first crew of 13 Freedom Riders left Washington for New Orleans in two buses. The group encountered some resistance in Virginia, but they didn’t encounter violence until they arrived in Rock Hill, S.C. At the bus station there, Mr. Lewis and another rider were beaten, and a third person was arrested after using a whites-only restroom.

When they reached Anniston, Ala., on May 14, Mother’s Day, they were met by an angry mob. Local officials had given the Ku Klux Klan permission to attack the riders without consequences. The first bus was firebombed outside Anniston while the mob held the door closed. The passengers were beaten as they fled the burning bus.

When the second bus reached Anniston, eight Klansmen boarded it and attacked and beat the Freedom Riders. The bus managed to continue on to Birmingham, Ala., where the passengers were again attacked at a bus terminal, this time with baseball bats, iron pipes and bicycle chains.

At one point during the rides, Mr. Lewis and others were attacked by a mob of white people in Montgomery, Ala., and he was left unconscious in a pool of his own blood outside the Greyhound Bus Terminal. He was jailed several times and spent a month in Mississippi’s notorious Parchman Penitentiary.

The attacks received widespread attention in the news media, but they pushed Mr. Farmer to end the initial campaign. The Freedom Riders finished their journey to New Orleans by plane.

Many more Freedom Rides followed over the next several months. Ultimately, 436 riders participated in more than 60 Freedom Rides, Mr. Arsenault said.

Were the rides a success?

On May 29, 1961, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy petitioned the Interstate Commerce Commission to ban segregation in interstate bus travel, according to PBS . The order, which was issued on Sept. 22 and went into effect on Nov. 1, led to the removal of Jim Crow signs from stations, waiting rooms, water fountains and restrooms in bus terminals.

Three years later, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ended segregation in public spaces across the United States.

How did the Freedom Rides influence Mr. Lewis’s career?

Mr. Lewis attained a particular status as a civil rights activist because he had been arrested and beaten so many times, Mr. Arsenault said.

“He was absolutely fearless and courageous, totally committed,” he said. “People knew that he always had their back and that they could count on him. He had an incorruptible commitment to nonviolence.”

In 1963, Mr. Lewis became the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and helped to organize the March on Washington, where the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech.

“That whole experience and in his role with the Freedom Riders really consolidated his reputation as this fearless civil rights activist who really had a strategic sense of the power of nonviolence,” said Kevin Gaines, the Julian Bond professor of civil rights and social justice at the University of Virginia. “Lewis really emerged among a group of impressive and very effective civil rights leaders.”

Derrick Bryson Taylor is a general assignment reporter on the Express Desk. He previously worked at The New York Post's PageSix.com and Essence magazine. More about Derrick Bryson Taylor

Sharing Stories Inspiring Change

- Civil Rights

- Community Organizing

- Disability Rights

- Labor Rights

- LGBTQIA Rights

- Reproductive Rights

- Voting Rights

- Women's Rights

- Architecture

- Fashion and Beauty

- Photography

- Advertising and Marketing

- Entrepreneurs

- Jewish Education

- Jewish Studies

- Summer Camps

- Women’s and Gender Studies

- Food Writing

- Antisemitism

- Soviet Jewry

- World War II

- Rosh Hashanah

- Simchat Torah

- Tisha B'Av

- Tu B'Shvat

- Philanthropy

- Social Work

- Civil Service

- Immigration

- International Relations

- Organizations and Institutions

- Social Policy

- Judaism-Conservative

- Judaism-Orthodox

- Judaism-Reconstructionist

- Judaism-Reform

- Midrash and Aggadah

- Spirituality and Religious Life

- Synagogues/Temples

- Agriculture

- Engineering

- Mathematics

- Natural Science

- Psychology and Psychiatry

- Social Science

- Coaches and Management

- Non-Fiction

Civil Disobedience and the Freedom Rides: Introductory Essay

Introductory Essay for Living the Legacy , Civil Rights, Unit 2, Lesson 3

One of the ways African American communities fought legal segregation was through direct action protests, such as boycotts, sit-ins, and mass civil disobedience. The tactic of non-violence civil disobedience in the Civil Rights Movement was deeply influenced by the model of Mohandas Gandhi, an Indian lawyer who became a spiritual leader and led a successful nonviolent resistance movement against British colonial power in India. Gandhi's approach of non-violent civil disobedience involved provoking authorities by breaking the law peacefully, to force those in power to acknowledge existing injustice and bring it to an end. For its followers, this strategy involved a willingness to suffer and sacrifice oneself.

In 1960, black college students used non-violent civil disobedience to fight against segregation in restaurants and other public places. On February 1, four black students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College in Greensboro, North Carolina, sat down at the whites-only lunch counter in Woolworth's and politely ordered some food. As expected, they were refused service, but they remained sitting at the counter until the store closed. The next day, they were joined by more than two dozen supporters. On day three, 63 of the 66 lunch counter seats were filled by students. By the end of the week, hundreds of black students and a few white supporters filled the lunch counters at Woolworth's and another store down the street.

The sit-ins attracted national attention, and city officials tried to end the confrontation by negotiating an end to the protests. But white community leaders were unwilling to change the segregation laws, so in April, students began the sit-ins again. After the mass arrest of student protestors on the charge of trespassing, the African American community organized a boycott of targeted stores. When the merchants felt the economic impact of the boycott, they relented, and on July 25, 1960, African Americans were served their first meal at Woolworth's.

The success of the Greensboro sit-ins led to a wave of similar protests across the South. More than 70,000 people – mostly black students, joined by some white allies – participated in sit-ins over the next year and a half, with more than 3,000 arrested for their actions.

Like the sit-ins, the Freedom Rides of 1961 were designed to provoke arrests, though in this case to prompt the Justice Department to enforce already existing laws banning segregation in interstate travel and terminal accommodations. These were not the first Freedom Rides. In 1947, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), an organization devoted to interracial, nonviolent direct action led by the African American pacifist Bayard Rustin, co-sponsored a bus ride through the South with the Christian pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation, to test compliance with 1946 Morgan v. Virginia decision that prohibited segregation on interstate buses. Those first Freedom Riders were arrested in North Carolina when they refused to leave the bus. In 1961, James Farmer – one of CORE's founders and its national director – decided to hold another interracial Freedom Ride, with support from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (founded in 1957 by Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP, founded in 1909).

The Freedom Ride began in Washington DC in May, with two interracial groups traveling on public buses headed toward Alabama and Mississippi. (John Lewis, who appears in Unit 2 lesson 7 and Unit 3 lesson 5, was among those on the first buses of Freedom Riders.) They faced only isolated harassment until they reached Anniston, Alabama, where an angry mob attacked one bus, breaking windows, slashing its tires, and throwing a firebomb through the window. The mob violently beat the Freedom Riders with iron bars and clubs while the bus burned. The second bus was also brutally attacked in Anniston. Violence followed both buses to Birmingham, where a mob beat the Freedom Riders while the police and the FBI watched and did nothing. No bus would take the remaining Freedom Riders on to Montgomery, so they flew to New Orleans on a special flight arranged by the Justice Department.

The CORE-sponsored Freedom Ride disbanded, but SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, founded in 1960) took up the project, gathering new volunteers to continue the rides. A new group of Freedom Riders, students from Nashville led by Diane Nash -- a young African American woman -- gathered in Birmingham and departed for Montgomery on May 20. The Montgomery bus station, which initially seemed deserted, filled with a huge mob when the passengers got off the bus. Several Freedom Riders were severely injured, as were journalists and observers. The mob violence and indifference of the Alabama police attracted negative international press for the Kennedy Administration. In response, Attorney General Robert Kennedy sent 400 U.S. marshals to prevent further mob violence, and called for a cooling off period, but civil rights leaders including Martin Luther King, James Farmer and SNCC leaders insisted that the Freedom Rides would continue. So Robert Kennedy brokered a compromise agreement: if the Freedom Riders were allowed to pass safely through Mississippi, the federal government would not interfere with their arrest in Jackson.

At this point, the Freedom Riders developed a new strategy: fill the jails. They called on civil rights activists to join them on the Freedom Rides, and buses from all over the country headed South carrying activists committed to challenging segregation. Over the course of the summer, more than 300 Freedom Riders were arrested in Jackson, where they refused bail and instead filled the jails, often facing beatings, harassment, and deplorable conditions. More than half of the white Freedom Riders were Jewish.

Judith Frieze, a recent graduate of Smith College, was among those white northerners and many Jews who joined the Freedom Rides in the summer of 1961. Arrested in Jackson, she spent six weeks in a maximum security prison. Upon her release, she documented her experience in an 8-part series of articles published in the Boston Globe .

Eventually, the Freedom Rides succeeded in their mission: by the end of 1962, the Justice Department pressed the Interstate Commerce Commission to issue clear rules prohibiting segregation in interstate travel. The experience revealed the hesitancy of the federal government to enforce the law of the land and the intransigence of white resistance to desegregation. But it also strengthened SNCC, whose leadership at a crucial moment of the Freedom Rides led to the project's success and taught these young civil rights activists about the central role of politics, and the importance of appealing to the pragmatism of politicians -- even the President -- in the fight for civil rights.

Help us elevate the voices of Jewish women.

Listen to Our Podcast

Get sweet swag.

Get JWA in your inbox

Read the latest from JWA from your inbox.

sign up now

How to cite this page

Jewish Women's Archive. "Civil Disobedience and the Freedom Rides: Introductory Essay." (Viewed on April 2, 2024) <http://jwa.org/teach/livingthelegacy/civil-disobedience-and-freedom-rides-introductory-essay>.

For Teachers

- Changing America

- Freedom Summer

The Abolitionists

Slavery by Another Name

Freedom Riders

The Loving Story

You are here

- The Power of the Individual

Film & Theme

The power of the individual: freedom riders.

In the spring of 1961, the Freedom Rides brought together people of different races, religions, cultures, and economic backgrounds from across the country. Most were students in their late teens or twenties. Some traveled alone, others as part of a group unified by the single objective to challenge segregation in the former Confederate states. Many southern whites believed segregation was a fundamental part of their communities and reacted violently to any attempt to change it.

One of the major clashes between the Freedom Riders and supporters of segregation occurred outside Anniston, Alabama in May 1961. This clip shows the brutal confrontation that resulted when a white mob ambushed and burned the bus. The events are recounted by a variety of white and black eye witnesses who reveal several different perspectives.

Further Analysis

Freedom Riders . Day 1. 20:00–29:00: Two buses of Freedom Riders travel through Alabama; Governor Patterson reacts to the Rides; Attack at the Anniston bus station.

Questions for class discussion

- Recount the stages of the events in Anniston.

- The film shows many whites who reacted violently but others—the young girl who brought water and the police officer who eventually stopped the confrontation —who did not. Why did so many white southerners react so violently to the Freedom Riders? Why did these other whites react differently?

- Was the attack a success from the attackers’ point of view? From the Riders’ point of view?

Scholarly Essay

- Raymond Arsenault on Freedom Riders

Background Articles for the Teacher

- Freedom Riders Online Exhibit

- “People Get Ready”: Music and the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s

Lesson Plans

- JFK, Freedom Riders, and the Civil Rights Movement

- Freedom Riders and the Popular Music of the Sixties

Primary Sources

- Robert Kennedy on civil rights , (1963)

- George Wallace on segregation , (1964)

More Resources

- Freedom Riders Website

- Film Segments

Explore Created Equal in the Classroom:

- Equality Under the Law - The Power of the Individual - The Strategy of Nonviolence

Community Programs

The NEH Created Equal project uses the power of documentary films to encourage public conversations about the changing meanings of freedom and equality in America.

Changing America Exhibit

Find a "Changing America" exhibit in your community.

- Lesson Plans

- Teacher's Guides

- Media Resources

JFK, Freedom Riders, and the Civil Rights Movement

Images of Freedom Riders at the Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, Georgia.

Wikimedia Commons

"I was an original 'Freedom Rider.' I was attacked and beaten by the Klu Klux Klan [sic] in Alabama; and I walked among the giants of the Civil Rights Movement and I felt at home. The lumps and bruises on my head are a daily reminder of my commitment and my obligations." — Charles Person, "My Reflection of Years Gone By"

Most lessons on the 1960s Civil Rights Movement focus on key national leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and President John F. Kennedy. This lesson is no exception; however, it will also look at less well-known members of the civil rights struggle: those whose courageous actions triggered a federal response. This lesson will help students learn more about these members of the grassroots civil rights struggle through the use of primary documents, audio sources, and photographs.

The first part of this lesson focuses on the Freedom Riders . It demonstrates the critical role of activists in pushing the Kennedy Administration to face the contradiction between its ideals and the realities of federal politics. In this case, the Kennedy Administration finally acted in defense of individual rights at the risk of offending powerful Southern politicians.

The second activity revisits the famous Birmingham Movement of 1963. It allows students to learn something about the grassroots protests against segregation and exclusion, the reaction of Alabama and Birmingham officials, and President Kennedy's public response-a renewed commitment to civil rights.

Finally, the 1963 March on Washington remains a touchstone of the Civil Rights Movement, and the "I Have A Dream Speech" will be familiar to teachers and students. Here, that speech is contextualized by three other speeches: President Kennedy's June 11, 1963 speech on civil rights, the John Lewis speech given at the March (in the slightly censored version demanded on the day of the March), and a Malcolm X speech critiquing the March. Collectively, these readings will give students a fuller perspective on the "I Have a Dream" speech, one shaped by the diverse viewpoints of contemporaries.

Guiding Questions

Why did the issue of civil rights divide people in the U.S.?

Whose approach to advancing civil rights appears most plausible?

Why do the speeches and perspectives regarding civil rights in the U.S. given at the time remain relevant today?

Learning Objectives

Evaluate the significance of the Freedom Rides, the 1963 Birmingham Movement, and the 1963 March on Washington to the civil rights movement.

Analyze the speeches and competing perspectives regarding how to establish civil rights protections in the U.S.

Analyze and evaluate the relationship between civil rights activists and the Federal Government.

Lesson Plan Details

Much of The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and '60s hinged on the relationship between grass roots activists, segregationist state and local governments, and a Federal Government bound (sometimes ambivalently) to uphold the Constitution. These lessons examine this relationship first of all with a look at the Freedom Rides. Student activists from the newly-formed Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the older Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) launched the Freedom Rides in 1961 , challenging and helping to destroy Jim Crow . By traveling as a racially integrated group on interstate buses through the South, the Freedom Riders sought to confront the Southern state authorities who enforced segregation, and to pressure the Federal Government to implement the Supreme Court ruling in Boynton v. Virginia (1960) that outlawed segregation in interstate travel.

Riding from Washington, DC to Montgomery, Alabama, the Freedom Riders were violently attacked by white segregationist mobs. Several riders were brutally beaten and some were permanently injured, but the rides continued as new students and activists took the place of those forced to drop out because of their injuries. Widespread media coverage of assaults on the riders gripped the nation and played a role in pushing the Kennedy Administration to intervene on the riders' behalf. After a summer in which the Federal Justice Department struggled to accommodate the conflicting demands of the Civil Rights activists and Southern politicians, the Federal Interstate Commerce Commission outlawed segregation in interstate bus travel in a much more detailed and forceful manner than the Supreme Court had. The Freedom Rides had achieved their aim .

However, the Freedom Rides gave rise to friction within the movement between the student protesters who became the backbone of the rides and Martin Luther King, Jr., who actively supported the rides, but did not directly participate. They also heightened tensions between the Kennedy Administration and the increasingly militant student wing of the movement, which viewed the administration's willingness to compromise with Southern politicians with great suspicion.

Despite the assistance of black and pro-civil rights voters in winning the 1960 Presidential Election, Kennedy had done little to push civil rights in his first year in office. Violence surrounding civil rights protests in the South, however, spurred him to action on the side of the growing movement. The Freedom Rides and attempts to integrate southern state universities prompted him to deploy federal marshals in defense of blacks demanding equal rights. Yet perhaps the most decisive influence on President Kennedy's civil rights agenda were the civil rights protests that rocked the city of Birmingham in 1963 and garnered worldwide attention. The shock and outrage that followed television and newspaper images of police dogs and fire hoses attacking black children and the racial violence that accompanied the protests made Kennedy feel that broad federal civil rights legislation was necessary. On June 11, 1963, he spoke to the country in a televised address in which he asked the American people to support the strongest civil rights bill since the Reconstruction Era.

To show that this bill had widespread support and to press their own demands further onto the national political agenda, civil rights groups around the country mobilized in support of a March on Washington on August 28, 1963. Today, the March is remembered primarily for the memorable speech that Martin Luther King gave on that day, known as the "I Have a Dream" speech.

It is important to understand, however, that the same historically creative tensions that marked events such as the Freedom Rides played an important role in the March's organization, program, and impact. The Kennedy Administration, Martin Luther King, and the militant student civil rights activists supported the March's overall demands, but they differed significantly in their assessment of the political landscape surrounding the March. In fact, the Kennedy Administration had initially opposed the idea of the March. There was also an ongoing mistrust of federal power within the black community, personified at that moment by black nationalists such as Malcolm X. These contrasting perspectives would continue to exercise influence as the civil rights movement grew and diversified.

NCSS.D2.His.1.9-12. Evaluate how historical events and developments were shaped by unique circumstances of time and place as well as broader historical contexts.

NCSS.D2.His.2.9-12. Analyze change and continuity in historical eras.

NCSS.D2.His.3.9-12. Use questions generated about individuals and groups to assess how the significance of their actions changes over time and is shaped by the historical context.

NCSS.D2.His.4.9-12. Analyze complex and interacting factors that influenced the perspectives of people during different historical eras.

NCSS.D2.His.14.9-12. Analyze multiple and complex causes and effects of events in the past.

NCSS.D2.His.15.9-12. Distinguish between long-term causes and triggering events in developing a historical argument.

NCSS.D2.His.16.9-12. Integrate evidence from multiple relevant historical sources and interpretations into a reasoned argument about the past.

The following EDSITEMENT-reviewed websites provide helpful background material to review before teaching this lesson:

- The PBS film and website Freedom Riders partially funded by NEH (above), is devoted to telling the story of the 400 black and white Americans who risked their lives—and many endured savage beatings and imprisonment—for simply traveling together on buses and trains as they journeyed through the Deep South.

- The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History an EDSITEment-reviewed website has an entire issue of their journal History Now devoted to the civil rights movement with essays, lesson plans and an interactive jukebox. For this lesson, the James T. Patterson essay " The Civil Rights Movement: Major Events and Legacies " provides an excellent general background. Anthony J. Badger's essay " Different Perspectives on the Civil Rights Movement " evaluates new trends in research which are putting civil rights successes in a different light.

- The major events and people covered in this lesson are described in short, informative entries at the EDSITEment-reviewed Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project . Recommended entries for this lesson include the Freedom Rides (1961), the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (1963), and the Birmingham Campaign (1963). You may also wish to read entries about John Lewis, Malcolm X, John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr.

- If you wish to know more about John F. Kennedy and civil rights, the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library presents an essay describing Southern race relations from the founding of the United States up to Kennedy's Administration. If you'd like to skip to the early 1960s section, just read pages three to four. This page is linked to the EDSITEment-reviewed American President.org. The PBS documentary Freedom Riders also hosts a brief summary of President Kennedy's role in the early Civil Rights Movement.

- The site SNCC: 1960-1966 presents the early history of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. It has articles on the Freedom Rides and John Lewis which are especially pertinent for this lesson. If you will be using civil rights to open up a discussion of other 1960s movements, you can also explore SNCC's connection to the feminism and Vietnam War protests in the website's Issues section .

Activity 1. The Kennedy Administration's Record on Civil Rights

In this initial step, students learn background information through doing two readings before going on to the next activities. They are asked to take notes on the reading.

For homework, students should read an online summary of President Kennedy's civil rights record , from the EDSITEment-reviewed Center for History and New Media website, and the King Encyclopedia entry on the Freedom Rides . Additionally, students should consult the PBS documentary Freedom Riders for background on the issues faced by the Freedom Rides campaign .

Students should take notes on what they read, listing:

- the actions that the Kennedy Administration took regarding civil rights and the Civil Rights Movement;

- any criticisms, positive or negative, those participants in the Civil Rights Movement made of the Kennedy Administration or the Federal Government.

Students should then read the following online documents, linked to the EDSITEment-reviewed Center for History and New Media website:

- The Introduction to Project "C" in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference's 1963 campaign in Birmingham, Alabama

- President Kennedy's press conference comments, " An Ugly Situation in Birmingham, 1963 ," on the civil rights protests in Birmingham

- Teachers may also want to review students' notes from their reading of the summary of President Kennedy's civil rights record

Then, in the final part of this activity, students should respond in writing to the following questions:

What do President Kennedy's comments tell us about:

- How does President Kennedy say this conflict has been resolved?

- How does he describe what has happened in Birmingham?

- What is he leaving out of this description?

- Why would he omit this information?

- What type of audience is watching events in Birmingham, according to Kennedy?

And, judging by these comments, to what extent does President Kennedy appear to support or oppose the Civil Right Movement in Birmingham at this time? Please use evidence from the press conference reading to support your answers.

Activity 2. Different Actors in the Civil Rights Movement

- Students will read a brief background explanation, view the official program of the 1963 March On Washington for Jobs and Freedom, as well as see a photo of the crowds attending the March, at Our Documents' Official Program for the March on Washington , linked to National Archives Education , an EDSITEment-reviewed website.

- Students will read a brief excerpt from the King Encyclopedia on the EDSITEment-reviewed Martin Luther King Papers' Project site, mentioning Kennedy's initial fear and then embrace of the March on Washington. Click here to go to the King Encyclopedia , and then click on "March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom."

- Students will then examine four speeches connected to the March. The teacher can assign all students to read all four speeches. Alternatively, the teacher might use a "jigsaw" approach, dividing the class into four groups, giving each group one speech. After each group has read its assigned speech and answered the questions, students can meet in groups of four in which each student has read a different speech. Now each student explains the speech he or she read to the other students, and how his or her group answered the questions. Following the "jigsaw," the teacher can lead a classwide discussion on the speeches.

The speeches

- President Kennedy's Speech on Civil Rights June 11, 1963—Here is the transcript , and an audio clip . Both links are from the EDSITEment-reviewed American President ;

- John Lewis speech delivered at the March on Washington in August, 1963—" Patience is a Dirty and Nasty Word ."

- Martin Luther King speech delivered at the March on Washington in August, 1963—" I Have A Dream" from the EDSITEment-reviewed Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project ;

- From Malcolm X Speaks , an audio clip from the November 10, 1963 "Message to the Grassroots"—click on "The March on Washington" to hear his critique of the March. This site is connected to the EDSITEment-reviewed History Matters website.

Questions on the speeches:

How do each of these speeches describe the role played by the Federal Government in the Civil Rights Movement?

- What is the role of the Federal Government in ensuring equal rights for African Americans, according to each of the different speakers?

- What do each of the speakers think is the key to changing the second-class status of African Americans in American life?

- Based upon your prior knowledge of the status of African-Americans in the United States at this time, and your analysis of the arguments in each speech, which speech or speaker gives the best explanation of the U.S. Government's relationship to the Civil Rights Movement?

Following the class discussion, return the students to the "jigsaw" group from Activity 3, in which each student read a different speech (if all students have read all of the speeches, any groups will work). Assign each group a different newspaper: a Northern newspaper, a Southern newspaper, or an African American newspaper.

Students, acting as the editorial board for their assigned newspaper, will write an editorial commenting on the speeches given at the March on Washington. Which position would the editorial board endorse for the African American community? What would they have the Administration endorse (bear in mind Kennedy's initial opposition to the March)? How should the majority of Americans, who were not at the March, respond to the issues raised that day?

- Have students look at images of the Birmingham Protest at Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement site , a link on EDSITEment-reviewed History Matters , and then write a quick response to President Kennedy on the Birmingham press conference from the point of view of a protestor. There are additional images from the Library of Congress website, The Civil Rights Era in the U.S. News & World Report Photographs Collection.

- Students can read oral histories of the freedom riders at such sites as the Civil Rights Movement Timeline . One particularly powerful account is by Steve McNichols " The Last Freedom Ride ," about CORE's last ride from Los Angeles to Houston, Texas in August of 1961. One idea would be to ask students read it and then write to President Kennedy on the Birmingham Press Conference. Additional oral histories could be found The Civil Rights in Mississippi: A Digital Archives , is a link on the EDSITEment-reviewed History Matters .

Selected EDSITEment Websites

- JFK, LBJ, and the Fight for Equal Opportunity in the 1960s

- The Civil Rights Era in the U.S. News & World Report Photographs Collection

- JFK in History: Civil Rights Context in the early 1960s

- John F. Kennedy Speeches: Address on Civil Rights

- John Lewis, "Patience is a Dirty and Nasty Word"

- People & Events: The Kennedys and Civil Rights

- Project "C" in Birmingham

- "An Ugly Situation in Birmingham," 1963

- Official Program for the March on Washington (1963)

- History Now: the Civil Rights Movement

- " The Civil Rights Movement: Major Events and Legacies "

- " Different Perspectives on the Civil Rights Movement "

- The Civil Rights in Mississippi: A Digital Archives

- Malcolm X Speaks

- Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement: Images of a People's Movement

- SNCC: 1960-1966

- Freedom Rides

- SNCC -- Issues

- Martin Luther King, Jr., "I Have A Dream"

- King Encyclopedia

- PBS Freedom Riders Documentary

Related on EDSITEment

A raisin in the sun: whose "american dream", jfk, lbj, and the fight for equal opportunity in the 1960s, let freedom ring: the life & legacy of martin luther king, jr., martin luther king, jr., gandhi, and the power of nonviolence, the freedom riders and the popular music of the civil rights movement.

Over 3 Million Original Newspapers World’s Largest Archive

Order early to beat the Easter bank holiday weekend!

15% off Birthday Books!

The Freedom Riders of 1961: Through The Papers

Written by Samples

Last Updated on 2nd February 2021

Thirteen men and women made history when they courageously defied the segregation norms of the United States in 1961 , during the Civil Rights Movement. Their efforts would pave the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as well as the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which were crucial acts passed to end legal segregation in the United States.

This post tells their story through newspaper content written about the Freedom Riders, showing how publications at the time reported on the movement. The reports reveal the racial attitudes of the American South at the time and provide fascinating first-hand accounts from those who saw the rides taking place.

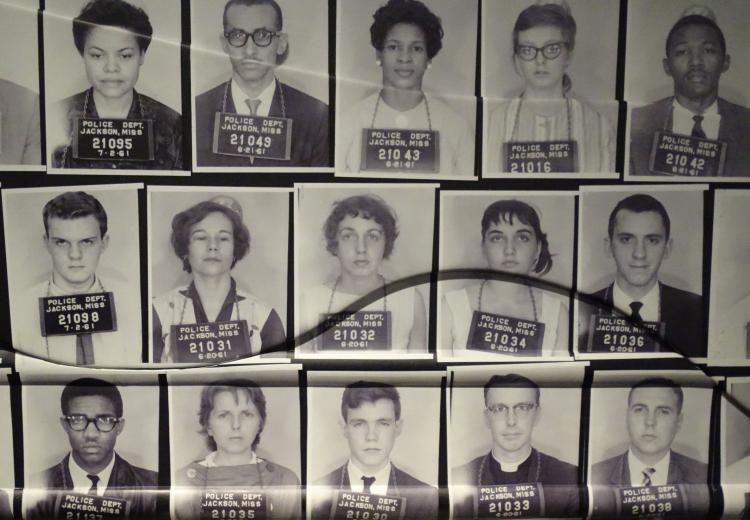

Mug shots of a group of Freedom Riders Image: Wikimedia Commons

Turn the page to:

Who Were The Freedom Riders?

The violence continues, lack of police protection, “eyewitness tells story of rioting”, armed officers dispatched, arrests made, discipline for students, the ku klux klan intervene, from montgomery to mississippi, robert f. kennedy.

- Corruption Among the Police

The Freedom Riders were a group of thirteen young people who rode buses across the Southern states to challenge segregation laws surrounding public transport. The origins of the Freedom Rides came from the 1947 “Journey of Reconciliation” created by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), which attempted to focus attention on the way in which transport in Southern cities and states was racially segregated.

At the time the Freedom Rides took place, the renowned Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s was gathering momentum, and African American citizens were still subject to racial hatred and discrimination in the Jim Crow Southern states. Starting in May 1961, and led by the director of CORE James Farmer , the main aim of the Freedom Riders was to test the compliance with two Supreme Court Rulings:

- Boynton v. Virginia, which claimed that the segregation of lunch counters, waiting rooms and bathrooms was unconstitutional

- Morgan v. Virginia, which stated that it was unconstitutional to implement and enforce segregation on interstate trains and buses.

Among the riders was representative John Lewis, then aged 21, who would become a crucial figure in the civil rights movement and American politics. In total, there were seven black and six white riders, with the defiant act crossing racial boundaries. While the original group of riders was small, the group expanded dramatically as the movement took off. Some of the other riders included, but were not limited to:

- CORE Director James Farmer – leader of the Freedom Riders

- Raymond Arsenault

- Rev. Benjamin Elton Cox

- Genevieve Hughes

- Mae Frances Moultrie

- Joseph Perkins

- Charles Person

- William E. Harbour

- Joan Trumpauer Mullholland

- Ed Blankenheim

Before the riders took off, they engaged in some training in the form of role-playing so they could prepare for some of the harassment they would face. Racial segregation and discrimination was still in full force during this time, particularly in the American South, so the group were completely aware of the backlash they would face as a result of their actions.

Racial violence was common in the states they were travelling across and their efforts would be strongly disapproved of by white southerners. The Freedom Riders journey became an iconic part of the civil rights movement and was a memorable attempt to challenge the racial norms of the American South.

Freedom Rider Mobbing

On Sunday, May 21, 1961, The Washington Post reported on the violent mobbing of the Freedom Riders, 17 days after their traveling first began. The front page headline on this day was:

The Washington Post headline, Sunday, May 21, 1961

Immediately, we can interpret that the violence was extreme, since marshals had been ordered by the President to offer back up support due to the eruption of mobbing. The subheading also stated “U.S. Official Is Knocked Unconscious,” showing the public the seriousness of the situation. According to the newspaper:

“James Zwerg, the only white youth among the freedom riders, apparently was the most seriously hurt.”

This reveals to us that the violent mobs were infuriated by the whole group and their efforts, and were not afraid to attack whoever was involved, no matter the color of their skin.

The newspaper includes a quote from screaming women, giving us an insight into the racial attitudes of the time:

“Kill the n*****-loving……,” several women screamed when the Appleton, Wis., youth stepped from the bus.”

This quote allows us to feel the strength of racial hatred among some white Southerners who were at the station where the participants got off.

This Washington Post issue also pays a lot of attention to James Zwerg, writing that:

“Several bearded youths immediately pounced on Zwerg, a tall youth dressed in an olive green business suit. He was knocked to the pavement with a rain of blows to the face and shoulders and lay bleeding profusely in the street.”

Since Zwerg was the only white person on the bus at this time, did the newspaper focus on him for this reason, or was it purely because he was badly hurt?

In terms of the official knocked unconscious, the newspaper writes that:

“The Kennedy aide who was beaten was John Seigenthaler, 32, an administrative assistant to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy.”

At the time, Seigenthaler was in the South to have discussions about the best way to protect the Freedom Riders. While trying to help one girl escape the mob, he was knocked unconscious. Interestingly, the newspaper reported:

“A reporter asked Police Commissioner L. B. Sullivan why an ambulance wasn’t called for Zewrg and Seigenthaler.”

Sullivan allegedly replied that every white ambulance in town had reported that their vehicles had broken down.

The same newspaper issue continues discussing the mobbing on the following page, claiming that:

“The actual violence was carried out by only 25 or 30 of the estimated 300 persons that gathered at the bus terminals for the freedom riders arrival.”

This shows that the Freedom Riders had gained significant attention from the public, allowing their cause to spread further, especially when the Washington Post goes on to say that the crowds got up to an estimated 1500 to 2000 people.

Details of the violence were included in the reports, stating that: