An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Endocrinol Metab

- v.16(4); 2018 Oct

The Principles of Biomedical Scientific Writing: Introduction

Zahra bahadoran.

1 Nutrition and Endocrine Research Center, Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Sajad Jeddi

2 Endocrine Physiology Research Center, Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Parvin Mirmiran

Asghar ghasemi.

A well-written introduction of a scientific paper provides relevant background knowledge to convince the readers about the rationale, importance, and novelty of the research. The introduction should inform the readers about the “problem”, “existing solutions”, and “main limitations or gaps of knowledge”. The authors’ hypothesis and methodological approach used to examine the research hypothesis should also be stated. After reading a good introduction, readers should be guided through “a general context” to “a specific area” and “a research question”. Incomplete, inaccurate, or outdated reviews of the literature are the more common pitfalls of an introduction that may lead to rejection. This review focuses on the principles of writing the introduction of an article and provides a quick look at the essential points that should be considered for writing an optimal introduction.

1. Introduction

Writing scientific papers is currently the most accepted outlet of research dissemination and scientific contribution. A scientific paper is structured by four main sections according to IMRAD (Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion) style ( 1 ).

To quote Plato, the Greek philosopher, “the beginning is half of the whole”, and the introduction is probably one of the most difficult sections in writing a paper ( 2 ). For writing introduction of a scientific paper, a “deductive approach” is generally used; deduction is the reasoning used to apply general theories and principles to reach specific consequences or hypotheses ( 3 ).

The initial impression of readers about writing style, the overall quality of research, validity of its findings, and the conclusion is strongly influenced by the introduction ( 4 ). A poor introduction misleads the readers about the content of the paper, possibly discouraging them from reading the subsequent sections; a well-written introduction, however, convinces the reader about the research logic ( 4 , 5 ). A good introduction is hence the main challenge faced by authors when drafting a research manuscript ( 2 ).

Historically, writing an introduction as an independent section of a research paper was underscored in the 1980s ( 6 ). Studies available on scientific writing provide evidence emphasizing the complexity of the compositional process of writing an introduction; these studies concluded that “introduction is not just wrestling with words to fit the facts, but it is also strongly modulated by perceptions of the anticipated reactions of peer-colleagues” ( 6 ).

Although there is no single correct way to organize different components of a research paper ( 7 ), scientific writing is an experimental science ( 7 ), and several guides have been developed to improve the quality of research disseminations ( 8 - 11 ). Typically, an introduction contains a summary of relevant literature and background knowledge, highlights the gap of knowledge, states the research question or hypothesis, and describes the methodological approach used to fill in the gap and respond to the question ( 12 - 14 ). Some believe that introduction can be a major context for debate about research methodology ( 6 ).

This review focuses on the principles of writing the introduction section and provides a quick look at the main points that must be considered for writing a good introduction.

2. Functions of the Introduction

The introduction of a scientific paper may be described as the gate to a city ( 5 ). It may also resemble a mental road map that should elucidate “the known”, “the unknown”, and “the new knowledge added by findings of the current study” ( 4 ); it presents the background knowledge to convince the readers of the importance of data added to that available in the field ( 15 ); in addition, the introduction sets the scene for readers ( 16 ) and paves the way for what is to follow ( 17 ). The introduction should be tailored to the journal to which the manuscript is being submitted ( 18 ). It has two functions, to be informative enough for understanding the paper and to evoke the reader’s interest ( 19 , 20 ). An introduction should serve as a hook, informing the readers of the question they should expect the paper to address ( 7 ). “A good introduction will sell the study to editors, reviewers, and readers” ( 18 , 21 ).

3. Common Models of Writing an Introduction

A historical overview of scientific writing shows that several models have been proposed overtime on how to organize the introduction of a research paper. One of the most common approaches is the “problem-solving model” developed in 1979; according to this model, a series of subcontexts including “goal”, “current capacity”, “problem”, “solution”, and “criteria for evaluation” have been described ( 6 ). The structure of this model could vary across disciplines ( 22 , 23 ).

Another popular model proposed is “creating a research space”, which mainly focuses on “the dark side” of the issue; this model, is usually known as CARS (create-a-research-space) model and follows three moves including establishing a territory (the situation), establishing a niche (the problem), and occupying a niche (the solution) ( 24 , 25 ). This model can be modified to a four-move model by expanding move 3 to include a “concluding step” when it is required to explain the structure of remaining parts of the paper ( 6 , 25 ).

4. A Typical Model of Introduction

In this paper, we focused on a typical model of introduction commonly used in biomedical papers. As shown in Figure 1 , the form of introduction is a funnel or an inverted pyramid, from large to small or broad to narrow ( 7 , 16 , 19 , 26 ). The largest part of the funnel at the top describes the general context/topic and the importance of the study; the funnel then narrows down to the gap of knowledge, and ends with the authors’ hypothesis or aim of the study and the methodological approach used to examine the research hypothesis ( 18 , 26 ). In fact, introduction presents research ideas flowing from general to specific ( 27 ). As given below, in hypothesis-testing papers, the introduction usually consists of 2 - 3 ( 28 ) and sometimes 4 paragraphs ( 16 ), including the known, the unknown (knowledge gap), hypothesis/question or specific topic, and sometimes the approach ( 16 , 19 ). Some authors end the introduction with essential findings of the paper ( 29 ). It has, however, been argued that the introduction should not include results or conclusion from the work being reported ( 2 , 16 , 20 ), as readers would then lose their interest in reading the rest of the manuscript ( 2 ). The introduction may also be expanded by including some uncommon parts like “future implications of the work” ( 30 ).

4.1. The Known

In this section, a brief summary of background information is provided to present the general topic of the paper ( 20 ). This section should arouse and build the audience’s attention and interest in the hypothesis/question or specific topic ( 29 ). This part may be considered the same as move 1 of the CARS model and includes “claiming importance”, “making topic generalizations”, and “reviewing items of previous research” ( 22 , 24 ).

Besides the different roles proposed for citation, its primary motive is believed to be “perceived relevance” ( 31 ). It is important that the review of literature be complete, fair, balanced ( 29 ), to the point ( 19 ), and directly related to the study ( 16 ); it should not be too long or contain a very detailed review of literature ( 7 , 28 ) or a complete history of the field ( 9 ). Depending on the audience ( 16 ), authors should include background information that they think readers need for following the rest of the paper ( 16 ).

Contrary to the current view that the introduction should be short and act as a prelude to the manuscript itself, another opinion, however, suggests this section provides a complete introduction to the subject ( 32 ). Sweeping generalizations (i.e., applying a general rule to a specific situation) should be avoided in the first (the opening) sentence of the introduction ( 8 ). The first three sentences of the first paragraph should present the issue that will be addressed by the paper ( 8 ). If the general topic be presented in the very first word of a very short sentence, the reader is able to immediately focus on and understand the issue ( 30 ).

4.2. The Unknown/Gap of Knowledge

The importance and novelty of the work should be stated in the introduction ( 19 ). This section describes the gaps in our present understanding of the field and why it is necessary that these gaps in data be filled ( 29 ). In this section, the author should present limitations of prior studies, needed (but currently unavailable) information, or an unsolved problem and highlight the importance of the missing pieces of the puzzle ( 16 ). This section provides information to justify the aim of the study, that is, it provides rationale for the readers to convince them ( 8 , 20 ); however, one-sided or biased views of controversial issues should be avoided ( 33 ).

The unknown section of the introduction is similar to “establishing a niche” and includes “counter-claiming” and “indicating a gap” ( 6 , 25 ). To develop a “counter-claiming” statement, the author needs to mention an opposing viewpoint or perspective or highlight a gap or limitation in current literature ( 24 ). “Counter-claiming” sentences are usually distinguished by a specific terminology, including albeit, although, but, howbeit, however, nevertheless, notwithstanding, unfortunately, whereas, and yet ( 24 ). This step toward or “continuing a tradition” part ( 6 , 25 ) is an extension of prior research to expand upon or clarify a research problem ( 24 ), and the connection is commonly initiated with the following terms: “hence,” “therefore,” “consequently,” or “thus” ( 24 ). An alternative approach for “counter-claiming” within the context of prior research is giving a “new perspective” without challenging the validity of previous research or highlighting their limitations ( 24 ).

Pitfalls in this section include missing an important paper and overstating the novelty of the study ( 29 ).

4.3. Rationale of Research/Hypothesis/Question

Defining the rationale of research is the most critical mission of the introduction section, where the author should tell the reader why the research is biologically meaningful ( 34 ). In stating the rationale of the study, an author should clarify that the study is the next logical step in a line of investigations, addressing the limitations of previous works ( 8 ). This section corresponds to “occupying the niche” in the CARS model ( 6 ), where contribution of the research in the development of “novel” knowledge is stated in contrast to prior research on the topic ( 24 ). The question/hypothesis, something that is not yet proven ( 35 ), is placed at the tip of the inverted cone/pyramid ( 16 ), and it is usually last sentence of the last paragraph in the introduction that presents the specific topic, which is “ What was done in your paper ?” ( 7 , 8 , 19 ).

The main and secondary objectives should be clear and preferably comprise no more than two sentences ( 20 ). The question should be clearly stated as the most common reason for rejection of a manuscript is the inability to do this ( 8 ); it would be a bad start that reviewers/readers cannot grasp the research question of the paper ( 36 ).

5. Writing Tips

5.1. the length.

The introduction should be generally short ( 7 , 37 ) and not exceed one double-spaced typed page ( 37 ), approximately 250 - 300 words are typically sufficient and sometimes it may be longer (500 - 600 words) ( 19 , 38 ); however, depending on the audience and type of paper, the length of the introduction could vary ( 20 ); if it is more than two-thirds the length of the results section, it is probably too long ( 9 ). It has been recommended that the introduction should be no more than 10% to 15% of total manuscript excluding abstract and references ( 18 , 26 ). A long introduction may be used to compensate for the limited data given about the actual research, a pitfall that peer-reviewers are aware of ( 30 ).

5.2. Sentence and Paragraph

In a scientific paper, each paragraph should contain a single main idea ( 7 , 39 ) that stands alone and is very clear ( 7 ). The first sentence of a paragraph should tell the reader what to expect to get out of the paragraph ( 7 ). Flow is a critical element in paragraph structure, that is to say, every sentence should arise logically from the sentence before it and transition logically into the next sentence ( 7 ). It is suggested that length of a sentence in a scientific text should not exceed 25 - 30 words; maximum three to four 30-word sentences are allowed in a paper ( 40 ). The ideal size for a paragraph is 3 - 4 sentences (maximum five sentences) ( 39 ) or 75 - 150 words (ideally not exceeding 150 words) ( 30 ). The maximum length of a paragraph in a well-written paper should not exceed 15 lines ( 30 ).

To test readability of a paragraph or passage, the Gunning Fog scoring formula may be helpful. This index helps the author to write clearly and simply. Fog score is typically between 0 and 20 and estimates the years of formal education the reader requires to understand the text on the first reading (5, is very easy; 6 is easy to read; 14 is difficult; 16 is very difficult) ( 41 , 42 ). Fog score is calculated as follow:

Where a complex word is defined as a word containing three or more syllables ( 43 ). An online tool that calculates the Gunning Fog Index is available at http://gunning-fog-index.com/index.html.

Using the correct verb tense in scientific writing enables authors to manage time and establish a logical relation or “time framework” within different parts of a paper ( 44 ). Two tenses are mostly used in scientific writing, namely the present and the past ( 18 , 45 ); “present tense” is used for established general knowledge (general truths) and “past tense” for the results that you are currently reporting ( 11 , 39 , 45 ). Some authors believe that “present tense” better describes most observations in a scientific paper ( 5 , 7 ). To manage the time framework of the introduction, a transitional verb tense from “present simple” at the beginning (to describe general background) to “present perfect” (describing the problem over time), and again “present simple” at the end of introduction (to state the hypothesis and approach) is commonly recommended ( 30 ).

Although a review of the literature may recommend several tenses, using “present simple” or “present perfect” is more common ( 46 ); the use of “present tense” to refer to the existing research indicates that the authors believe the findings of an older research are still true and relevant ( 44 ). The “present perfect tense” may be adopted when authors communicate “currency” (being current), in both positive (asserting that previous studies have established a firm research foundation) and negative (asserting that not enough relevant or valid work has yet been done) forms ( 44 ).

As seen in Table 1 , much of the introduction emphasizes on previously established knowledge, hence using the present tense ( 11 , 37 ). If you give the author’s name non-parenthetically, present or past tense could be used for the verb that is linked to the author; however, scientific work itself is given in the present tense; for instance, Smith (1975) showed that streptomycin inhibits growth of the organism ( 11 ).

5.4. Citation

Reference section is a vital component of papers ( 51 ). Peer-reviewed articles are preferred by scientific journals ( 51 ). Be cautious never to cite a reference that you have not read ( 51 ) and be sure to cite the source of the original document ( 18 ). The number of references in the introduction should be kept to a minimum ( 19 ) according to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (http://icmje.org). Only directly pertinent references should be selected, but do not miss important previous works ( 9 , 20 ). A common error in the writing of an introduction is the struggle to review all evidence available on the topic, which confuses the readers and often buries the aim of the study in additional information ( 26 , 52 ). If there are many references, select the first, the most important, the most elegant, the most pertinent, and the most recent ones ( 18 , 19 ). References should be selected from updated papers with higher impact factors ( 5 ). In addition, select original rather than review articles ( 2 , 53 ), as this is what most editors/reviewers expect ( 18 ). In the presence of newer references, older ones are usually used if considered as being an influential work ( 16 ).

Unnecessary overlap of introduction and discussion is a problem for both sections, therefore, it has been strongly recommended to cite the references where it makes most sense ( 16 ). No reference needs to be made for accepted facts such as double-helical structure of DNA ( 9 ). There is usually no need to list standard text books as references and if this has been done, specify the place in the book ( 32 ). Some authors believe that referring to papers using author names should be avoided, as it slows the pace of writing ( 8 ).

6. Common Pitfalls in Writing Introduction

The most common pitfalls that occur during writing the introduction include: ( 1 ) Providing too much general information, ( 2 ) going into details of previous studies, ( 3 ) containing too many citations, ( 4 ) criticizing recent studies extensively, ( 5 ) presenting the conclusion of the study, except for studies where the format requires this, ( 6 ) having inconsistency with other sections of the manuscript, ( 7 ) including overlapping information with the discussion section, and ( 8 ) not reporting most relevant papers ( 2 ). In Table 2 , most do’s and don’ts for writing a good introduction are summarized; examples of the principles for writing an introduction for a scientific paper can be found in the literature ( 16 , 19 ).

7. Conclusion

The introduction of scientific original papers should be short but informative. Briefly, the first part of a well-written introduction is expected to contain the most important concisely cited references, focused on the research problem. In the second part, the problem and existing solutions or current limitations should be elaborated, and the last paragraph should describe the rationale for the research and the main research purpose. The introduction is suggested be concluded with a brief paragraph that describes the organization of the rest of the paper. Overall, a good introduction should convince the readers that the study is important in the context of what is already known.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Ms Niloofar Shiva for critical editing of English grammar and syntax of the manuscript.

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 11: The Title

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Content of titles for hypothesis-testing papers.

- CONTENT OF TITLES FOR DESCRIPTIVE PAPERS

- CONTENT OF TITLES FOR METHODS PAPERS

- HALLMARKS OF A GOOD TITLE

- RUNNING TITLES

- SUMMARY OF GUIDELINES FOR TITLES

- EXERCISE 11.1: TITLES

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Titles of biomedical journal articles have two functions: to identify the main topic or the message of the paper and to attract readers.

Stating the Topic in the Title

The standard title of a biomedical research paper is a phrase that identifies the topic of the paper. For a hypothesis-testing paper, the topic includes three pieces of information: the independent variable(s) that you manipulated, if any (X), the dependent variable(s) you observed or measured (Y), and the animal or population and the material on which you did the work (Z). The animal studied must always be included in the title, whether or not the animal studied is included in the question and the answer. If necessary, two other pieces of information may also be included in the title: the condition of the animals or subjects during the study and the experimental approach.

Titles for Papers That Have Both Independent and Dependent Variables

For studies that have both independent and dependent variables, the standard form of the title is

Effect of X on Y in Z.

Note that in this standard form, the animal, population, or material studied comes at the end of the title.

When humans are studied, they are often omitted from the title, as in Example 11.2 , though it is clearest to include "humans" in the title, as in Example 11.22 below.

Effect of Membrane Splitting on Transmembrane Polypeptides

However, when a subpopulation of humans was studied, the subpopulation is always included in the title.

Effects of Esmolol on Airway Function in Patients Who Have Asthma

For the negative implication to work (no population in the title implies that the population is humans), the animal must always be included in the title when the work was done on animals.

Titles for Papers That Have Only Dependent Variables

For hypothesis-testing studies that have only dependent variables, the standard form of the title is

where Y is the dependent variable(s)—that is, the variable(s) observed or measured—and Z is the animal or population and the material on which the work was done. For examples, see the revisions of Examples 11.25 and 11.27 below. Also see Example 11.36 below.

Other Information in the Title

Sign in or create a free Access profile below to access even more exclusive content.

With an Access profile, you can save and manage favorites from your personal dashboard, complete case quizzes, review Q&A, and take these feature on the go with our Access app.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Essentials of writing biomedical research papers

Related Papers

Journal of Surgical Research

IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication

Jalt Journal

Tamara Swenson

The Modern Language Journal

Aleidine Moeller

Anthony Liddicoat

Danielle Ooyoung Pyun

Maureen Andrade

Luisa Pérez

Linda Kay Davis

Mary Jane Treacy

RELATED PAPERS

Claudia Fernández

Sarah Jourdain

Modern Language Journal

Karim Sadeghi

Kathryn F Whitmore

Theresa Y Austin

diana pulido

Jinyan Huang

Jonathan Newton

Matilde Scaramucci

Jean Janecki

Frank Daulton

Mohammad Al-Masri

Cristina Pausini

Roger C Nunn

Peter Sayer

Patricia Cummins

Kathryn Murphy-Judy

Frank Nuessel

International Statistical Review

William Seaver

Randall Schumacker

Daniel Velasco

Shuangzhe Liu

IATEFL ESP SIG Journal Professional and Academic English

Mark Krzanowski , Andy Gillett

Limarys Caraballo

Manuel Diaz-campos

Francisco Yus

María del Pilar García Mayo

Robert W Train

Modern Language Journal 89, p. 158

Charles Grove

Kate Paesani

Mohd Sallehhudin Abd Aziz , Dr momtazur Rahman

International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism

Joseph Lo Bianco

Kees De Bot

Norris John

Bettye Chambers

Yasmina Mobarek

Maria Cristina Peccianti

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Essentials of writing biomedical research papers

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

29 Previews

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station64.cebu on April 1, 2023

Celebrating 75 Years! Learn More >>

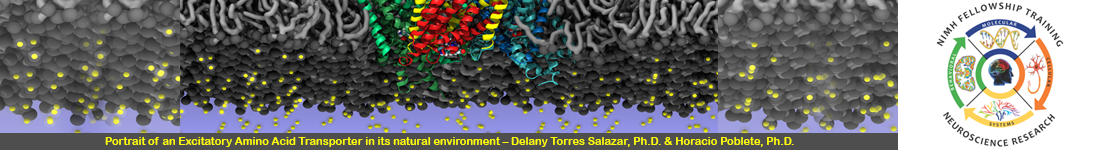

- Research Funded by NIMH

- Research Conducted at NIMH (Intramural Research Program)

- Priority Research Areas

- Research Resources

Writing Biomedical Research Papers

This rigorous course emphasizes that the goal of writing is clarity and reviews how clarity can be achieved via the basic components (words, sentences, and paragraphs) of all expository writing, as applied to each section of a biomedical reserach paper. The course and its associated textbook first reviews the special expectations of each section of a paper in each component and then reviewing examples of both well and poorly written components. Although students do not actually write any new text, they are expected to explicate and edit numerous examples of bad writing. Each hour and half of class requires about three times that amount of time to read the text and to work on its exercises. I try to keep the class interactive and lively by using an Aristotelan approach of asking questions of the students and by adding some of my dry humor. Dr. Robert B. Innis, M.D., Ph.D. Chief , Section on PET Neuroimaging Sciences Molecular Imaging Branch NIMH, IRP

REQUIREMENTS : This course is not a basic introduction to writing; instead, it is an intermediate to advanced level course. Students are expected, for example, to be proficient in English vocabulary, to know the parts of a sentence (subject, verb, and predicate), to readily know parts of speech (noun, adverb, adjective, etc.), and to differentiate active from passive voice. From prior classes, students who lacked these skills received little benefit from the course. To summarize, students appropriate for this course might well be novices at scientific writing, but they should not be novices at writing per se. Session Date Topic 1 9/3/2014 Introduction: Pages 1-8 2 9/8/2014 Chapter 1: Word Choice 3 9/10/2014 Chapter 2: Sentence Structure - first half 4 9/15/2014 5 9/22/2014 Chapter 2: Sentence Structure - second half 6 9/24/2016 7 9/29/2014 Chapter 3: Paragraph Structure - first half 8 10/1/2014 Chapter 3: Paragraph Structure - second half 9 10/6/2014 10 10/8/2014 Chapter 4: Introduction 11 10/15/2014 Introduction: exercise 12 10/20/2014 13 10/22/2014 Introduction: hypothesis-testing paper 14 10/27/2014 Chap 5: Materials & Methods; SI units; verb tense 15 10/29/2014 16 11/3/2014 Chap 5: Exercises 5.1 & 5.2 17 11/5/2014 Chapter 6: Results (first 80%) 18 11/10/2014 19 11/12/2014 Chapter 6: Results (last 20%) plus Chap 7 20 11/19/2014 Chap 7: Discussion 21 11/24/2014 22 12/1/2014 Chap 7: Exercise 7.2 & Chap 8 graphs 23 12/3/2014 Chap 8: Graphs plus Briscoe’s chap on graphs 24 12/8/2014 25 12/11/2014 * Thurs Chap 8: Tables 26 12/15/2014 Chap 8: Abstract 27 12/17/2014 28 12/22/2014 Chap 9: Title & seek students’ opinions of course TIME: Mondays & Wednesdays 3:30 - 5:00 PM (except * Thursday 12/11/2014) LOCATION: TBD TEXTBOOK: Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers , Second Edition, Mimi Zeiger, McGraw-Hill: New York, 2000.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers. Second Edition 2nd by Zeiger, Mimi (1999) Paperback Paperback

- Language English

- Publisher McGraw-Hill Professional

- See all details

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Product details

- ASIN : B00G0AF39W

- Language : English

About the author

Mimi zeiger.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Start Selling with Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Revisions of Exercises

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Summary of Guidelines for Word Choice

Words in scientific research papers should be

Use few if any abbreviations.

Exercise 1.1: Principles of Word Choice

Words in scientific research papers should be PRECISE .

(Strunk and White, II. 16, p. 21: Use definite, specific, concrete language.)

Your words should be as precise as your science.

Note that precise, definite, specific, concrete words evoke a mental image. For example, "dog" evokes much more of a mental image than "animal" does. Similarly, "pattern of discharge" evokes much more of a mental image than "response characteristics" does. Words that evoke mental images help make writing easy to read. Abstractions (such as "animal" and "characteristics") make reading difficult.

greatly decreased; reduced by 80%.

POINT : "Compromised" is imprecise: what happened to renal blood flow? ("Compromise" means "place at risk." A person's chances of survival can be compromised. But blood flow is measurable, so it increases or decreases.) "Drastically" is also imprecise. Science is quantitative; thus, a quantitative detail such as "by 80%" is clearer than a qualitative term such as "greatly."

POINT : "Several" is imprecise. How long is several hours? State the mean or a range.

POINT : A change could be either an increase or a decrease. From the first sentence we cannot tell whether the author meant increase or decrease. But from "further increase" in the next sentence we can see that the change in the first sentence must have been an increase. It is clearest to write "increase," not "change," in the first sentence.

incubated in, grown in, bathed in.

POINT : "Exposed to" is imprecise. How were the cells exposed? Use a precise term. "Put in" does not work here because the cells probably were not added for 48 h.

POINT : Keep the name of the animal in the reader's mind.

prevented, blocked.

POINT : "To rescue" means to free from death or destruction. An appropriate use of "rescue" is to say that the phenotype is rescued (from death or destruction) by some event in the genotype. In Example 6, an intervention prevents a process (it does not rescue the process). In Example 7, one substance offsets the lack of another substance (it does not rescue the lack of another substance). "Rescue" is an example of a "buzz word," that is, a word that is in fashion. Using a buzz word shows that you belong to the club. It is reasonable to use current terminology, including buzz words, but the problem with buzz words is that they are often imprecise. So use buzz words only in their precise meaning.

prevented, inhibited, repressed.

POINT : "Negatively regulated" is a vague way of expressing a concept that can be conveyed precisely by a variety of verbs.

Sign in or create a free Access profile below to access even more exclusive content.

With an Access profile, you can save and manage favorites from your personal dashboard, complete case quizzes, review Q&A, and take these feature on the go with our Access app.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Read Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers, 2e online now, exclusively on AccessBiomedical Science. AccessBiomedical Science is a subscription-based resource from McGraw Hill that features trusted medical content from the best minds in medicine.

Read this chapter of Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers, 2e online now, exclusively on AccessBiomedical Science. AccessBiomedical Science is a subscription-based resource from McGraw Hill that features trusted medical content from the best minds in medicine.

We recommend "Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers" to students, editors, and writers at all levels who want to master IMRAD format or learn techniques that will improve their writing."--"American Medical Writers Association," From the Publisher. Mimi Zeiger, MA is at the University of San Francisco, San Francisco, California ...

This paper aims to provide a scaffolding for clear writing in the field of biomedical research paper-writing by demonstrating the importance of sentence structure in the development of narrative structure. Preface. Credits. The Goal: Clear Writing. Section I: The Building Blocks of Writing. Chapter 1: Word Choice. Chapter 2: Sentence Structure. Chapter 3: Paragraph Structure. Section II: The ...

Second Edition. Mimi Zeiger. McGraw Hill Professional, Oct 21, 1999 - Medical - 440 pages. Provides immediate help for anyone preparing a biomedical paper by givin specific advice on organizing the components of the paper, effective writing techniques, writing an effective results sections, documentation issues, sentence structure and much more.

Read chapter 5 of Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers, 2e online now, exclusively on AccessBiomedical Science. AccessBiomedical Science is a subscription-based resource from McGraw Hill that features trusted medical content from the best minds in medicine.

Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers, Second Edition, provides writers with specific, clear guidelines on word choice, sentence structure, and paragraph structure. In addition, it explains how to construct each section of a research paper, so that, ultimately, the paper as a whole tells a clear story and sends a clear message.

Reaching the Goal: Suggestions for Writing. Revisions of Exercises. Literature Cited. Words Explained in The Text. Read Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers, 2e online now, exclusively on AccessPharmacy. AccessPharmacy is a subscription-based resource from McGraw Hill that features trusted pharmacy content from the best minds in the ...

Provides a complete course in biomedical writing for class use or self-study. Assists mainly new authors to understand what a well written scientific research paper is, by means of example. Introduces them to principles of clear writing, as applied specially to scientific research papers.

Read chapter 4 of Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers, 2e online now, exclusively on AccessPharmacy. AccessPharmacy is a subscription-based resource from McGraw Hill that features trusted pharmacy content from the best minds in the field.

1. Introduction. Writing scientific papers is currently the most accepted outlet of research dissemination and scientific contribution. A scientific paper is structured by four main sections according to IMRAD (Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion) style ().To quote Plato, the Greek philosopher, "the beginning is half of the whole", and the introduction is probably one of the ...

Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers grew out of a course in scientific writing given to postdoctoral fellows in cardiovascular research. The course was started by Julius H. Comroe, Jr., M.D., the founder and first director of the Cardiovascular Research Institute at the University of California, San Francisco.

Essentials of writing biomedical research papers , second edition. Published 2001. Biology, Medicine. TLDR. Journal publication is an integral part of research that documents new information gleaned from an investigation, and in so doing inspires more research, in an endless search for truth. Expand.

Read chapter 11 of Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers, 2e online now, exclusively on AccessPharmacy. AccessPharmacy is a subscription-based resource from McGraw Hill that features trusted pharmacy content from the best minds in the field.

Download Free PDF. View PDF. 33 Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers. Mimi Zeiger. New York: McGraw-Hill, Health Professions Div., 1991. Reviewed by Lilita Rodman University of British Columbia This is an in-depth study of a very specific genre, the biomedical research paper. Growing out of courses Zeiger has taught to graduate ...

Essentials of writing biomedical research papers ... Essentials of writing biomedical research papers by Zeiger, Mimi. Publication date 1991 Topics Medical writing -- Handbooks, manuals, etc, Technical writing -- Handbooks, manuals, etc, Writing Publisher New York : McGraw-Hill, Health Professions Division

Read this chapter of Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers, 2e online now, exclusively on AccessBiomedical Science. AccessBiomedical Science is a subscription-based resource from McGraw Hill that features trusted medical content from the best minds in medicine.

Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers. Second Edition. Mimi Zeiger. McGraw Hill Professional, 2000 - Language Arts & Disciplines - 440 pages. Publisher's Note: Products purchased from Third Party sellers are not guaranteed by the publisher for quality, authenticity, or access to any online entitlements included with the product ...

Writing Biomedical Research Papers. This rigorous course emphasizes that the goal of writing is clarity and reviews how clarity can be achieved via the basic components (words, sentences, and paragraphs) of all expository writing, as applied to each section of a biomedical reserach paper. The course and its associated textbook first reviews the ...

The author does a nice job with basics of writing and then works hard to put each phase of a biomedical article in context. Each chapter provides extensive examples of a block of text that could use some crafting, and then works through how the text could have been presented or revised to make it stronger.

Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers. Mimi Zeiger. New York: McGraw-Hill, Health Professions Div., 1991. Reviewed by Lilita Rodman University of British Columbia This is an in-depth study of a very specific genre, the biomedical research paper. Growing out of courses Zeiger has taught to graduate

Read this chapter of Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers, 2e online now, exclusively on AccessBiomedical Science. AccessBiomedical Science is a subscription-based resource from McGraw Hill that features trusted medical content from the best minds in medicine.