- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Federalist Papers

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 22, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

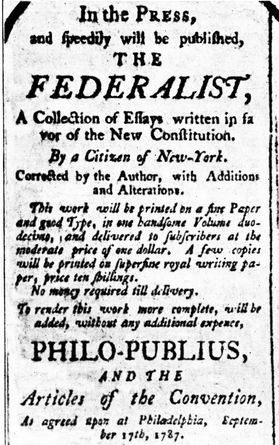

The Federalist Papers are a collection of essays written in the 1780s in support of the proposed U.S. Constitution and the strong federal government it advocated. In October 1787, the first in a series of 85 essays arguing for ratification of the Constitution appeared in the Independent Journal , under the pseudonym “Publius.” Addressed to “The People of the State of New York,” the essays were actually written by the statesmen Alexander Hamilton , James Madison and John Jay . They would be published serially from 1787-88 in several New York newspapers. The first 77 essays, including Madison’s famous Federalist 10 and Federalist 51 , appeared in book form in 1788. Titled The Federalist , it has been hailed as one of the most important political documents in U.S. history.

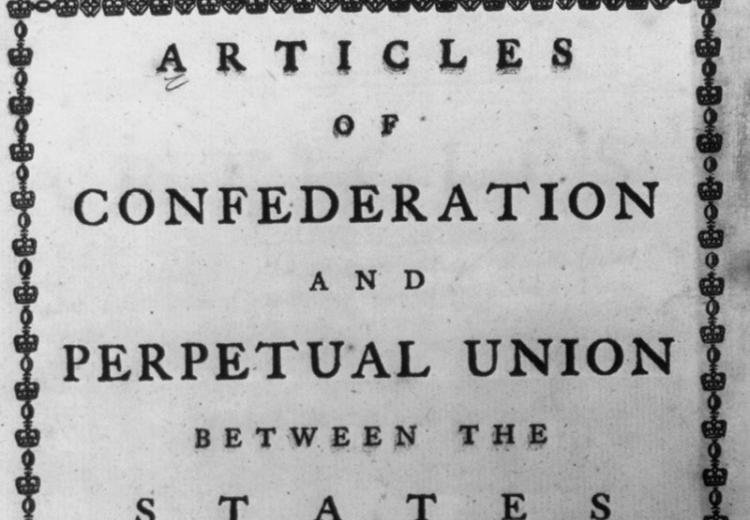

Articles of Confederation

As the first written constitution of the newly independent United States, the Articles of Confederation nominally granted Congress the power to conduct foreign policy, maintain armed forces and coin money.

But in practice, this centralized government body had little authority over the individual states, including no power to levy taxes or regulate commerce, which hampered the new nation’s ability to pay its outstanding debts from the Revolutionary War .

In May 1787, 55 delegates gathered in Philadelphia to address the deficiencies of the Articles of Confederation and the problems that had arisen from this weakened central government.

A New Constitution

The document that emerged from the Constitutional Convention went far beyond amending the Articles, however. Instead, it established an entirely new system, including a robust central government divided into legislative , executive and judicial branches.

As soon as 39 delegates signed the proposed Constitution in September 1787, the document went to the states for ratification, igniting a furious debate between “Federalists,” who favored ratification of the Constitution as written, and “Antifederalists,” who opposed the Constitution and resisted giving stronger powers to the national government.

The Rise of Publius

In New York, opposition to the Constitution was particularly strong, and ratification was seen as particularly important. Immediately after the document was adopted, Antifederalists began publishing articles in the press criticizing it.

They argued that the document gave Congress excessive powers and that it could lead to the American people losing the hard-won liberties they had fought for and won in the Revolution.

In response to such critiques, the New York lawyer and statesman Alexander Hamilton, who had served as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, decided to write a comprehensive series of essays defending the Constitution, and promoting its ratification.

Who Wrote the Federalist Papers?

As a collaborator, Hamilton recruited his fellow New Yorker John Jay, who had helped negotiate the treaty ending the war with Britain and served as secretary of foreign affairs under the Articles of Confederation. The two later enlisted the help of James Madison, another delegate to the Constitutional Convention who was in New York at the time serving in the Confederation Congress.

To avoid opening himself and Madison to charges of betraying the Convention’s confidentiality, Hamilton chose the pen name “Publius,” after a general who had helped found the Roman Republic. He wrote the first essay, which appeared in the Independent Journal, on October 27, 1787.

In it, Hamilton argued that the debate facing the nation was not only over ratification of the proposed Constitution, but over the question of “whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.”

After writing the next four essays on the failures of the Articles of Confederation in the realm of foreign affairs, Jay had to drop out of the project due to an attack of rheumatism; he would write only one more essay in the series. Madison wrote a total of 29 essays, while Hamilton wrote a staggering 51.

Federalist Papers Summary

In the Federalist Papers, Hamilton, Jay and Madison argued that the decentralization of power that existed under the Articles of Confederation prevented the new nation from becoming strong enough to compete on the world stage or to quell internal insurrections such as Shays’s Rebellion .

In addition to laying out the many ways in which they believed the Articles of Confederation didn’t work, Hamilton, Jay and Madison used the Federalist essays to explain key provisions of the proposed Constitution, as well as the nature of the republican form of government.

'Federalist 10'

In Federalist 10 , which became the most influential of all the essays, Madison argued against the French political philosopher Montesquieu ’s assertion that true democracy—including Montesquieu’s concept of the separation of powers—was feasible only for small states.

A larger republic, Madison suggested, could more easily balance the competing interests of the different factions or groups (or political parties ) within it. “Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests,” he wrote. “[Y]ou make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens[.]”

After emphasizing the central government’s weakness in law enforcement under the Articles of Confederation in Federalist 21-22 , Hamilton dove into a comprehensive defense of the proposed Constitution in the next 14 essays, devoting seven of them to the importance of the government’s power of taxation.

Madison followed with 20 essays devoted to the structure of the new government, including the need for checks and balances between the different powers.

'Federalist 51'

“If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” Madison wrote memorably in Federalist 51 . “If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.”

After Jay contributed one more essay on the powers of the Senate , Hamilton concluded the Federalist essays with 21 installments exploring the powers held by the three branches of government—legislative, executive and judiciary.

Impact of the Federalist Papers

Despite their outsized influence in the years to come, and their importance today as touchstones for understanding the Constitution and the founding principles of the U.S. government, the essays published as The Federalist in 1788 saw limited circulation outside of New York at the time they were written. They also fell short of convincing many New York voters, who sent far more Antifederalists than Federalists to the state ratification convention.

Still, in July 1788, a slim majority of New York delegates voted in favor of the Constitution, on the condition that amendments would be added securing certain additional rights. Though Hamilton had opposed this (writing in Federalist 84 that such a bill was unnecessary and could even be harmful) Madison himself would draft the Bill of Rights in 1789, while serving as a representative in the nation’s first Congress.

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Ron Chernow, Hamilton (Penguin, 2004). Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 (Simon & Schuster, 2010). “If Men Were Angels: Teaching the Constitution with the Federalist Papers.” Constitutional Rights Foundation . Dan T. Coenen, “Fifteen Curious Facts About the Federalist Papers.” University of Georgia School of Law , April 1, 2007.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Timeline of the Federalist-Antifederalist Debates

Introduction to the chronology of the federalist-antifederalist debates.

The Federalist-Antifederalist Debate is usually conceived of as having taken place after the release of the Constitution in September, 1787, and continuing up to its ratification in 1788. The debate, waged between editorialists – some name and most under pen-names – began before the Constitutional Convention had formally convened, and picked up pace by August, 1787. Most initial essays, printed in newspapers across the states, were from opponents to a new government; however, as time passed and the Federalist authors began producing their work from New York, other Federalist-aligned authors joined the effort, even if there was virtually no coordination between them.

What follows are essays from both those who supported and opposed the new constitution, from across the country, from Spring 1787 through the closing days of 1788, provided alongside one another for context.

- May 16, 1787: Z. (Pennsylvania)

August 1787

- Aug 6, 1787: A Foreign Spectator I (Pennsylvania)

- Aug 9, 1787: Atticus Essay I (Massachusetts)

- Aug 10, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part IV (Pennsylvania)

- Aug 16, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part VI (Pennsylvania)

- Aug 17, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part VII (Pennsylvania)

- Aug 24, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part X (Pennsylvania)

September 1787

- Sept 4, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part XV (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 12, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part XX (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 13, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part XXI (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 13, 1787: Objections to the Constitution (Virginia)

- Sept 17, 1787: Benjamin Franklin Speech, Federal Convention (Constitutional Convention)

- Sept 17, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part XXIII (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 18, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part XXIV (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 21, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part XXV (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 26, 1787: Letter from Sherman and Ellsworth to the Governor of Connecticut (Connecticut)

- Sept 26, 1787: An American Citizen I (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 27, 1787: A Pennsylvania Farmer (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 27, 1787: Cato I (New York)

- Sept 28, 1787: Call for state ratifying conventions by Confederation Congress (Confederation Congress)

- Sept 28, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part XXVIII (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 28, 1787: An American Citizen II (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 28, 1787: An American Citizen III (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 29, 1787: Curtius No. I (New York)

October 1787

- Oct 1787: An American Citizen IV (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 1, 1787: Caesar I (New York)

- Oct 1, 1787: Letter from Richard Henry Lee to George Mason (Virginia)

- Oct 2, 1787: Foreign Spectator XXIX (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 5, 1787: Centinel I (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 6, 1787: Crito (Rhode Island)

- Oct 8, 1787: Federal Farmer I (Virginia)

- Oct 9, 1787: Federal Farmer II (Virginia)

- Oct 10, 1787: Federal Farmer III (Virginia)

- Oct 10, 1787: Randolph Letter, On the Federal Constitution (Virginia)

- Oct 11, 1787: Cato II (New York)

- Oct 12, 1787: Federal Farmer IV (Virginia)

- Oct 12, 1787: An Old Whig I (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 13, 1787: Federal Farmer V (Virginia)

- Oct 13, 1787: Convention Essay (Massachusetts)

- Oct 15, 1787: One of Four Thousand (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 17, 1787: Connecticut calls for state convention (Connecticut)

- Oct 17, 1787: A Democratic Federalist (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 17, 1787: Caesar II (New York)

- Oct 17, 1787: An Old Whig II (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 17, 1787: A Citizen of America by Noah Webster (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 17, 1787: A Citizen of America: An Examination Into the Leading Principles of America (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 18, 1787: Brutus I (New York) ( click here for special commentary on Brutus I )

- Oct 18, 1787: Elbridge Gerry’s Objections (Massachusetts)

- Oct 18, 1787: Atticus Essay II (Massachusetts)

- Oct 20, 1787: An Old Whig III (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 22, 1787: John DeWitt I (Massachusetts)

- Oct 24, 1787: James Madison to Thomas Jefferson (Virginia)

- Oct 24, 1787: Monitor Essay (Massachusetts)

- Oct 24, 1787: Centinel II (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 25, 1787: A Republican No. 1 (New York)

- Oct 25, 1787: Cato III (New York)

- Oct 25, 1787: A Federalist Essay (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 27, 1787: John DeWitt II (Massachusetts)

- Oct 27, 1787: An Old Whig IV (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 27, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 1 (New York)( Click here for special commentary on Federalist 1 )

- Oct 30, 1787: Philo-Publius Essay I (New York)

- Oct 30, 1787: Letter from Gouverneur Morris to George Washington (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 31, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 2 (New York)

November 1787

- Nov 1, 1787: An Old Whig V (Pennsylvania)

- Nov 1, 1787: Brutus II (New York)

- Nov 1, 1788: Cincinnatus No. 1 (New York)

- Nov 2, 1787: Foreigner I (Pennsylvania)

- Nov 3, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 3 (New York)

- Nov 3, 1788: Elbridge Gerry to the Massachusetts General Court (Massachusetts)

- Nov 5, 1787: John DeWitt III (Massachusetts)

- Nov 5, 1787: A Landholder Letter I (Connecticut)

- Nov 6, 1787: An Officer of the Late Continental Army (Pennsylvania)

- Nov 7, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 4 (New York)

- Nov 7, 1787: Philadelphiensis I (Pennsylvania)

- Nov 8, 1787: Centinel III (Pennsylvania)

- Nov 8, 1787: Brutus, Junior (New York)

- Nov 8, 1787: Cato IV (New York)

- Nov 8, 1787: Cincinnatus No. 2 (New York)

- Nov 8, 1787: Federal Farmer: Letters to the Republican (Virginia)

- Nov 10, 1787: Massachusetts Centinel (Massachusetts)

- Nov 10, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 5 (New York)

- Nov 14, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 6 (New York)

- Nov 12, 1787: A Landholder Letter II (Connecticut)

- Nov 14, 1787: Socius Essay (Pennsylvania)

- Nov 15, 1787: Brutus III (New York)

- Nov 15, 1787: A Countryman I (Connecticut)

- Nov 15, 1787: Essay by a Georgian (Georgia)

- Nov 16, 1787: Philo-Publius Essay II (New York)

- Nov 17, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 7 (New York)

- Nov 17, 1787: An American: The Crisis (Massachusetts)

- Nov 19, 1787: A Landholder III (Connecticut)

- Nov 19, 1787: A Farmer, of New Jersey: Observations on Government New York (New Jersey)

- Nov 20, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 8 (New York)

- Nov 21, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 9 (New York)

- Nov 21, 1787: George Mason’s Objections (Virginia)

- Nov 22, 1787: Brutus on Mason’s Objections (Virginia)

- Nov 22, 1787: Cato V (New York)

- Nov 22, 1787: A Countryman II (Connecticut)

- Nov 22, 1787: Atticus Essay III (Massachusetts)

- Nov 22, 1787: Cincinnatus No. 4 (New York)

- Nov 22, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 10 (New York)( Click here for special commentary on Federalist 10 )

- Nov 23, 1787: Agrippa I (Massachusetts)

- Nov 24, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 11 (New York)

- Nov 24, 1787: An Old Whig VI (Pennsylvania)

- Nov 24, 1787 – Dec 24, 1787: Timothy Pickering and the Letters from the Federal Farmer (New York)

- Nov 24, 1787: John Jay and the Constitution (New York)

- Nov 26, 1787: A Landholder Letter IV (Connecticut)

- Nov 26,1787: A Democratic Federalist (Pennsylvania)

- Nov 27, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 12 (New York)

- Nov 27, 1787: Agrippa II (Massachusetts)

- Nov 28, 1787: Philadelphia Freeman’s Journal (Pennsylvania)

- Nov 28, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 13 (New York)

- Nov 28, 1787: Philadelphiensis II (Pennsylvania)

- Nov 28, 1787: An Old Whig VII (Pennsylvania)

- Nov 28, 1787: A Federal Republican: A Review of the Constitution (Virginia)

- Nov 29, 1787: Brutus IV (New York)

- Nov 29, 1787: Philo-Publius Essay III (New York)

- Nov 29, 1787: Maryland’s Constitutional Convention Delegates Address the State House of Delegates (Maryland)

- Nov 29, 1787: A Countryman III (Connecticut)

- Nov 30, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 14 (New York)

- Nov 30, 1787: Centinel IV (Pennsylvania)

- Nov 30, 1787: Agrippa III (Massachusetts)

December 1787

- Dec 1787: John DeWitt IV (Massachusetts)

- Dec 1, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 15 (New York)

- Dec 1, 1787: Philo-Publius Essay IV (New York)

- Dec 2, 1787: Daniel Carroll to Benjamin Franklin, Annapolis (Maryland)

- Dec 3, 1787: Agrippa IV (Massachusetts)

- Dec 3, 1787: A Landholder Letter V (Connecticut)

- Dec 3, 1787: Tobias Lear to John Langdon, Mount Vernon (Virginia)

- Dec 4, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 16 (New York)

- Dec 5, 1787: Philadelphiensis No. 3 (Pennsylvania)

- Dec 5, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 17 (New York)

- Dec 6, 1787: A Countryman IV (Connecticut)

- Dec 6, 1787: Z. (Massachusetts)

- Dec 6, 1787: Cincinnatus VI (New York)

- Dec 7, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 18 (New York)

- Dec 8, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 19 (New York)

- Dec 10, 1787: A Landholder VI (Connecticut)

- Dec 11, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 20 (New York)

- Dec 11, 1787: Agrippa V (Massachusetts)

- Dec 12, 1787: Philadelphiensis IV (Pennsylvania)

- Dec 12, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 21 (New York)

- Dec 12, 1787: Cato Essay (New York)

- Dec 13, 1787: Brutus V (New York)

- Dec 13, 1787: Alfred (Pennsylvania)

- Dec 14, 1787: Agrippa VI (Massachusetts)

- Dec 14, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 22 (New York)

- Dec 14, 1787: Letter from George Washington to Charles Carter (Virginia)

- Dec 16, 1787: Cato VI (New York)

- Dec 17, 1787: A Landholder Letter VII (Connecticut)

- Dec 18, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 23 (New York)

- Dec 18, 1787: Agrippa VII (Massachusetts)

- Dec 19, 1787: Extract of a Letter from New York, dated December 7 (New York)

- Dec 19, 1787: Anti-Cincinnatus (Pennsylvania)

- Dec 19, 1787: Philadelphiensis No. 5 (Pennsylvania)

- Dec 19, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 24 (New York)

- Dec 20, 1787: A Countryman V (Connecticut)

- Dec 21, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 25 (New York)

- Dec 22, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 26 (New York)

- Dec 22, 1787: Atticus Essay IV (Massachusetts)

- Dec 28, 1787: Genuine Information I (Maryland)

- Dec 24, 1787: A Landholder Letter VIII (Connecticut)

- Dec 25, 1787: Centinel VI (Pennsylvania)

- Dec 25, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 27 (New York)

- Dec 25, 1787: Federal Farmer VI (Virginia)

- Dec 25, 1787: Agrippa VIII (Massachusetts)

- Dec 26, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 28 (New York)

- Dec 26, 1787: Philadelphiensis No. 6 (Pennsylvania)

- Dec 27, 1787: Centinel VII (Pennsylvania)

- Dec 27, 1787: Brutus VI (New York)

- Dec 28, 1787: Samuel Adams and the Constitution (Massachusetts)

- Dec 28, 1787: Agrippa IX (Massachusetts)

- Dec 28, 1787: Luther Martin: Genuine Information II (Maryland)

- Dec 29, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 29 (New York)

- Dec 30, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 30 (New York)

- Dec 29, 1787: Centinel VIII (Pennsylvania)

- Dec 31, 1787: A Landholder Letter IX (Connecticut)

- Dec 31, 1787: Federal Farmer VII (Virginia)

- Dec 31, 1787: America by Noah Webster (New York)

- Dec 31, 1787: A Freeman Essay to the People of Connecticut (Connecticut)

Month Unknown

- 1788: A Citizen of New York (New York)

January 1788

- Jan 1788: Address by a Plebian (New York)

- Jan 1788: Advertisement for the Pamphlet Edition of the Federalist (New York)

- Jan 1, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 31 (New York)

- Jan 1, 1788: Agrippa X (Massachusetts)

- Jan 1, 1788: Genuine Information II ( Maryland)

- Jan 2, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 32 (New York)

- Jan 2, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 33 (New York)

- Jan 3, 1788: Cato VII (New York)

- Jan 3, 1788: Federal Farmer VIII (New York)

- Jan 3, 1788: Brutus VII (New York)

- Jan 4, 1788: Federal Farmer IX (Virginia)

- Jan 4, 1788: Luther Martin: Genuine Information III (Maryland)

- Jan 5, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 34 (New York)

- Jan 5, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 35 (New York)

- Jan 7, 1788: Resolutions of the Tradesmen of Boston (Massachusetts)

- Jan 7, 1788: Federal Farmer X (Virginia)

- Jan 8, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 36 (New York)

- Jan 8, 1788: Centinel IX (Pennsylvania)

- Jan 8, 1788: Luther Martin: Genuine Information IV (Maryland)

- Jan 8, 1788: Agrippa XI (Massachusetts)

- Jan 10, 1788: Brutus VIII (New York)

- Jan 10, 1788: Philadelphiensis No. 7 (Pennsylvania)

- Jan 11, 1788: Federal Farmer XI (Virginia)

- Jan 11, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 37 (New York)

- Jan 11, 1788: Common Sense Essay (Massachusetts)

- Jan 11, 1788: Agrippa XII Part 1 (Massachusetts)

- Jan 11, 1788: Governor George Clinton Speech to the New York Legislature (New York)

- Jan 11, 1788: Luther Martin: Genuine Information V (Maryland)

- Jan 12, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 38 (New York)

- Jan 12, 1788: Federal Farmer XII (Virginia)

- Jan 12, 1788: Centinel X (Pennsylvania)

- Jan 14, 1788: Federal Farmer XIII (Virginia)

- Jan 14, 1788: Agrippa XII Part 2 (Massachusetts)

- Jan 14, 1788: The Report of the New York’s Delegates to the Constitutional Convention (New York)

- Jan 15, 1788: Fisher Ames Speech, Massachusetts Convention (Massachusetts)

- Jan 15, 1788: Luther Martin: Genuine Information VI (Maryland)

- Jan 16, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 39 (New York)

- Jan 16, 1788: State Soldier Essay I (Virginia)

- Jan 16, 1788: Centinel XI (Pennsylvania)

- Jan 17, 1788: Brutus IX (New York)

- Jan 17, 1788: Federal Farmer XIV (Virginia)

- Jan 18, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 40 (New York)

- Jan 18, 1788: Luther Martin: Genuine Information VII (Maryland)

- Jan 18, 1788: Agrippa Letter XII Part 3 (Massachusetts)

- Jan 18, 1788: Federal Farmer XV (Virginia)

- Jan 18, 1788: A Citizen of New Haven by Roger Sherman, Letter I (Connecticut)

- Jan 19, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 41 (New York)

- Jan 22, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 42 . (New York)

- Jan 22, 1788: Luther Martin: Genuine Information VIII (Maryland)

- Jan 22, 1788: Agrippa XIII (Massachusetts)

- Jan 23, 1788: Centinel XII ( Pennsylvania)

- Jan 23, 1788: Federal Farmer XVI ( Virginia)

- Jan 23, 1788: A Copy of a Letter from Centinel (Pennsylvania)

- Jan 23, 1788: Philadelphiensis VIII (Pennsylvania)

- Jan 23, 1788: Federal Farmer XVII (Virginia)

- Jan 23, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 43 (New York)

- Jan 23, 1788: A Freeman Essay I (Pennsylvania)

- Jan 24, 1788: Brutus X (New York)

- Jan 25, 1788: Agrippa XIV Part 1 (Massachusetts)

- Jan 25, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 44 (New York)

- Jan 25, 1788: Federal Farmer XVIII (Virginia)

- Jan 26, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 45 (New York)

- Jan 27, 1788: Luther Martin to Thomas Cockey Deye (Maryland)

- Jan 29, 1788: Genuine Information IX (Maryland)

- Jan 29, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 46 (New York)

- Jan 29, 1788: Luther Martin: Genuine Information IX (Maryland)

- Jan 29, 1788: Agrippa XIV Part 2 (Massachusetts)

- Jan 29, 1788: Agrippa XV (Massachusetts)

- Jan 30, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 47 (New York)

- Jan 30, 1788: A Freeman Essay II (Pennsylvania)

- Jan 30, 1788: Centinel XIII (Pennsylvania)

- Jan 31, 1788: Brutus XI (New York)

February 1788

- Feb 1, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 48 (New York)

- Feb 1, 1788: Luther Martin: Genuine Information X (Maryland)

- Feb 2, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 49 (New York)

- Feb 5, 1788: Agrippa XVI (Massachusetts)

- Feb 5, 1788: Centinel XIV (Pennsylvania)

- Feb 5, 1788: Sidney No. 1 (New York)

- Feb 5, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 50 (New York)

- Feb 6, 1788: Old Whig No. 8 (Pennsylvania)

- Feb 6, 1788: Philadelphiensis No. 9 (Pennsylvania)

- Feb 6, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 51 (New York)( Click here for special commentary on Federalist 51 )

- Feb 6, 1788: A Freeman Essay III (Pennsylvania)

- Feb 6, 1788: State Soldier Essay II (Virginia)

- Feb 7, 1788: Brutus XII (Part 1) (New York)

- Feb 8, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 52 (New York)

- Feb 8, 1788: Luther Martin: Genuine Information XII (Maryland)

- Feb 9, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 53 ( New York)

- Feb 12, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 54 (New York)

- Feb 13, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 55 (New York)

- Feb 14, 1788: Brutus XII (Part 2) (New York)

- Feb 16, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 56 (New York)

- Feb 18, 1788: Elihu Essay (Connecticut)

- Feb 19, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 57 (New York)

- Feb 20, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 58 (New York)

- Feb 21, 1788: Brutus XIII (New York)

- Feb 21, 1788: Sidney No. 2 (New York)”

- Feb 22, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 59 (New York)

- Feb 22, 1788: Centinel XV (Pennsylvania)

- Feb 23, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 60 (New York)

- Feb 23, 1788: John Langdon to Rufus King (New Hampshire)

- Feb 25-27, 1788: Remarks on the New Plan of Government, Hugh Williamson (New York)

- Feb 26, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 61 (New York)

- Feb 26, 1788: Centinel XVI (Pennsylvania)

- Feb 27, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 62 (New York)

- Feb 27, 1788: Massachusetts Centinel (New Hampshire)

- Feb 27, 1788: Speech by John Hancock to the Massachusetts General Court (Massachusetts)

- Feb 28, 1788: Brutus XIV (Part 1) (New York)

- Feb 29, 1788: A Landholder X (Maryland)

- Mar 1, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 63 (New York)

- Mar 5, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 64 (New York)

- Mar 6, 1788: Brutus XIV (Part 2) (New York)

- Mar 7, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 65 (New York)

- Mar 7, 1788: Maryland Farmer Essay III (Part 1) (Maryland)

- Mar. 7, 1788: Reply to Maryland Landholder X (Maryland)

- Mar 8, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 66 (New York)

- Mar 8, 1788: Philadelphiensis XI (Pennsylvania)

- Mar 10, 1788: A Landholder XI (Connecticut)

- Mar 11, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 67 (New York)

- Mar 12, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 68 (New York)

- Mar 12, 1788: State Soldier Essay III (Virginia)

- Mar 12, 1788: One of the People Called Quakers (Virginia)

- Mar 14, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 69 (New York)

- Mar 15, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 70 (New York)

- Mar 17, 1788: A Landholder XII (Connecticut)

- Mar 18, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 71 (New York)

- Mar 18, 1788: Maryland Farmer Essay III (Part 2) (Maryland)

- Mar 18, 1788: Luther Martin: Address No. 1 (Maryland)

- Mar 19, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 72 (New York)

- Mar 19, 1788: State Soldier Essay IV (Virginia)

- Mar 20, 1788: Brutus XV (New York)

- Mar 21, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 73 (New York)

- Mar 21, 1788: Luther Martin: Address No. 2 (Maryland)

- Mar 24, 1788: A Landholder Letter XIII (Connecticut)

- Mar 24, 1788: Centinel XVII (Pennsylvania)

- Mar 25, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 74 (New York)

- Mar 26, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 75 (New York)

- Mar 28, 1788: Luther Martin: Address No. 3 (Maryland)

- Mar 30, 1788: Luther Martin to the Citizens of the United States (Maryland)

- Apr 1, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 76 (New York)

- Apr 2, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 77 (New York)

- Apr 2, 1788: State Soldier Essay V (Virginia)

- Apr 4, 1788: Maryland Farmer Essay VII (Part 1) (Maryland)

- Apr 4, 1788: Luther Martin: Address No. 4 (Maryland)

- Apr 9, 1788: Centinel XVIII (Pennsylvania)

- Apr 9, 1788: Philadelphiensis XII (Pennsylvania)

- Apr 10, 1788: Brutus XVI (New York)

- Apr 10, 1788: Spurious Luther Martin: Address No. 5 (Pennsylvania)

- Apr 17, 1788: A Plebeian: An Address to the People of New York (New York)

- Apr 12, 1788: Fabius I (Pennsylvania)

- Apr 15, 1788: Fabius II (Pennsylvania)

- Apr 17, 1788: Fabius III (Pennsylvania)

- Apr 18, 1788: Elbridge Gerry Responds to the Maryland “Landholder” X (Massachusetts)

- Apr 19, 1788: Fabius IV ( Pennsylvania)

- Apr 22, 1788: Fabius V (Pennsylvania)

- Apr 24, 1788: Fabius VI (Pennsylvania)

- Apr 26, 1788: Fabius VII (Pennsylvania)

- Apr 29, 1788: Fabius VIII ( Pennsylvania)

- May 1, 1788: Fabius IX (Pennsylvania)

- May 2, 1788: Federal Farmer: An Additional Number of Letters to the Republican (Virginia)

- May 12, 1788: Philodemos Essay (Massachusetts)

- May 25, 1788: Observations on the Constitution (Virginia)

- May 28, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 78 (New York)

- June 1, 1788: Observations of the Constitution, James Monroe (Virginia)

- June 6, 1788: Edmund Randolph Speech (Virginia)

- June 10, 1788: Edmund Randolph Speech, Virginia Ratifying Convention (Virginia)

- June 18, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 79 (New York)

- June 21, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 80 (New York)

- June 24, 1788: John Lansing, New York Ratifying Convention (New York)

- June 25, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 81 (New York)

- July 2, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 82 (New York)

- July 4, 1788: Oration on the Fourth of July (Pennsylvania)

- July 5, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 83 ( New York)

- July 16, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 84 (New York)

August 1788

- August 13, 1788: Federalist Paper No. 85 (New York)

December 1788

- Dec 10, 1788: An American Citizen: Thoughts on the Subject of Amendments, Part II (Pennsylvania)

- Dec 18, 1788: A Citizen of New Haven by Roger Sherman, Letter I (Connecticut)

- Dec 24, 1788: An American Citizen: Thoughts on the Subject of Amendments, Part III (Pennsylvania)

- Dec 25, 1788: A Citizen of New Haven by Roger Sherman, Letter II (Connecticut)

Receive resources and noteworthy updates.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.4: Debates between Federalists and Antifederalists

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 125855

- Robert W. Maloy & Torrey Trust

- University of Massachusetts via EdTech Books

Standard 2.4: Debates between Federalists and Anti-Federalists

Compare and contrast key ideas debated between the Federalists and Anti-Federalists over ratification of the Constitution (e.g., federalism, factions, checks and balances, independent judiciary, republicanism, limited government). (Massachusetts Curriculum Framework for History and Social Science) [8.T2.4]

FOCUS QUESTION: What were the key points of debate between Federalists and Anti-Federalists?

To replace the government that was operating under The Articles of Confederation , the Constitution was proposed, created, and sent to the states for ratification on September 17, 1787. To become law, the new Constitution had to be ratified (approved) by 9 of 13 states (as required by Article VII).

State legislatures were directed to call ratification conventions to debate and then approve or reject the new framework for the national government. Despite unhappiness over the Articles of Confederation, there was significant opposition to the new Constitution and its approval was very much in doubt in many states.

The debate over the ratification of the U.S. Constitution is known for the sharp divide it created among people in the newly independent states.

Two groups, the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists , emerged with the Federalists arguing for ratification and the Anti-Federalists arguing against the ratification. Federalist supporters of the Constitution included James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay, the authors of the Federalist Papers. Anti-Federalist opponents included George Clinton, Patrick Henry, and James Monroe (the future fifth President).

The new Constitution was finally approved on June 21, 1788 when New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify it (The Day the Constitution Was Ratified).

What were the main disagreements between Federalists and Anti-Federalists? The modules for this topic outline the two sides, the role of women in the debates, and how those disagreements are still impacting our lives and our politics today.

Modules for this Standard Include:

- MEDIA LITERACY CONNECTIONS: Investigating Political Debates Through Songs from the Musical Hamilton

- UNCOVER: Abigail Adams, Mercy Otis Warren, and the Political Roles of Women

- ENGAGE: Who Should Have Primary Responsibility for Environmental Policies?

2.4.1 INVESTIGATE: The Federalist-Antifederalist Debates

The Federalists believed that the Constitution would create a needed change in the structure of government. In their view, the Articles had created disarray through a system where state governments competed with one another for power and control. Federalists hoped the Constitution would establish a strong central government that could enforce laws of states, get things done, and maintain the union. It would create stability and the promise of growth as a unified nation . Key examples of the views of Federalists can be found in Federalist Paper Number 10 and Federalist Papers Numbers 1, 9, 39, 51, and 78 .

The Anti-Federalists feared the Constitution would create a central government that would act like a monarchy with little protection for civil liberties . Anti-Federalists favored power for state governments where public debate and citizen awareness had opportunities to influence and direct state and national policies. Important primary sources for Anti-Federalists include The Federal Farmer I , Brutus I , and the Speech of Patrick Henry (June 5, 1788).

The divide was intense and in most states, ratification of the new Constitution just barely happened. The Massachusetts vote, held on February 6, 1788, was 187 for ratification, 168 against.

You can learn more at the resourcesforhistoryteachers wiki page Federalists and Anti-Federalists .

Media Literacy Connections: Investigating Political Debates Through Songs from the Musical Hamilton

Hamilton: An American Musical , written by Lin-Manuel Miranda, tells the story of Alexander Hamilton and the founding of the United States using hip hop, R&B, pop, and soul music as well as Broadway-style show tunes. It opened in February 2015 and won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for Drama as well as numerous Tony Awards that same year.

Lin-Manuel Miranda described the musical as about "America then, as told by America now" ( The Atlantic , September 29, 2015, para. 2).

Explore how Hamilton portrays history and then write your own Hamilton- style lyrics in the following activities:

- Activity 1: Analyze the Lyrics from Hamilton

- Activity 2: Write Your Own Hamilton -Style Lyrics

Suggested Learning Activities

- Minimum Wage Laws

- Early Voting Days and Times

- Motorcycle Helmet Laws and Traffic Speed Limits

- Environmental Protections and Air Quality

Online Resources on Federalists and Anti-Federalists

- Multimedia video and lesson plan on the Constitutional Convention from Khan Academy

- The Question of States' Rights: The Constitution and American Federalism , from Exploring Constitutional Conflicts

2.4.2 UNCOVER: Abigail Adams, Mercy Otis Warren, and the Political Roles of Women

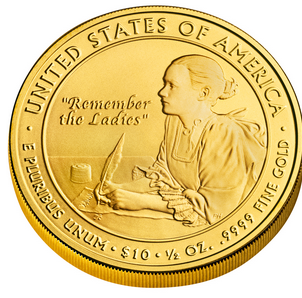

While men did the writing of the Constitution, the voices of women were heard in the debates over ratification and the rights of citizens.

Abigail Adams was an advocate for women's rights, supporter of education for women, and active opponent of slavery. She was also the wife of future President John Adams and mother of President John Quincy Adams. Her "Remember the Ladies" letter to husband John Adams is a famous document from the time.

You can read more of her writing at About the Correspondence Between John & Abigail Adams , from the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Mercy Otis Warren , from Barnstable and Plymouth, Massachusetts, was a poet, playwright, and essayist whose writing was strongly political - a dramatic departure from how women were supposed to behave at the time.

Mercy Otis Warren has been described as "the leading female intellectual of the Revolution and early republic" (Michals, 2015, para. 1; National Women's History Museum ). Warren was both an outspoken supporter of the American Revolution and a strong Anti-Federalist opponent of the Constitution. Like other anti-federalists, her opposition to the new government ranged from the "lack of a bill of rights guaranteeing freedom of the press and the rights of individuals, to the indirect, antidemocratic method for electing the president" (Brown & Tager, 2000, p. 108).

Mercy Otis Warren wrote many political pieces under the pseudonym "A Columbian Patriot" in support of the Anti-Federalist ideals. Explore her writing at: " Observations on the new Constitution, and on the federal and state conventions. By a Columbian patriot. ; Sic transit gloria Americana ."

- Watch the video The Founding Mothers of the United States: An Overview , in which journalist Cokie Roberts and author Walter Isaacson discuss the life and times of Martha Washington, Deborah Franklin, and Mercy Otis Warren.

- What roles did these women play in the beginning of the United States?

- Using Milestones for Women in Politics website as a starting point, build a timeline of women's political roles in the United States (using Timeline JS , Tiki Toki , or another interactive timeline builder).

Online Resources for the Political Role of Women in the Early United States

- Mercy Otis Warren , New World Encyclopedia

- Mercy Otis Marries James Warren, November 14, 1754

- Persuading male voters

- Crusades against slavery and alcohol

- Compelling narratives

- Political organizing

- Transforming everyday objects into political vehicles

- Did the American Revolution Change the Role of Women in Society? History in Dispute (Vol. 12)

- Founding Mothers: Women's Roles in American Independence

2.4.3 ENGAGE: Who Should Have Primary Responsibility for Environmental Policies?

In fulfilling a 2016 campaign pledge to create more business- and industry-friendly policies (especially for fossil fuel and nuclear power companies), the Presidential Administration of Donald Trump has dramatically altered the environmental policies of the federal government.

The Department of the Interior and other federal branch agencies have loosened or eliminated rules and regulations put in place by previous Presidents, rolling back offshore drilling safety regulations, greenlighting oil and gas pipeline projects, granting energy companies access to wildlife habitats, permitting increased logging of federal forests, and easing restrictions on greenhouse gas emissions from coal power plants, among other changes ( A Running List of How President Trump is Changing Environmental Policy , National Geographic, 2017; updated 2019; Trump v. Earth , National Resources Defense Council, 2020).

Deregulation policies included replacing the Clean Power Plan, revising and weakening the Endangered Species Act, Coal Ash Rule, the Mercury and Air Toxic Standards, and reversing bans on the use of pesticides in farming ( The Trump Administration's Major Environmental Deregulations , Brookings, December 15, 2020). You can follow changes in environmental rules and policies with a Climate Deregulation Tracker from the Sabin Center for Climate Change at Columbia University School of Law.

The Trump Administration's environmental policies have placed the federal government in direct and contentious opposition to numerous state governments , notably those controlled by Democrats. That state governments have a central role in environmental policy has been established in court, namely Massachusetts v. EPA (2006), a landmark climate change case where the Supreme Court ruled that a state government had the authority under the Clean Air Act to regulate auto emissions. That decision was written by Justice John Paul Stevens , who wrote a number of significant environmental decisions during his time on the Court; Stevens died in 2019 at the age of 99.

Trump policies led to direct conflicts with states, notably California, which has enacted stricter environmental protection laws than most of the rest of the states in the country ( California sues Trump again for revoking state's authority to limit auto emissions ). It is one of the latest examples of the historic tension in American politics between states' rights and federal power—a tension that goes all the way back to the Articles of Confederation and what policies are to be controlled states or by the national government.

The Yosemite Land Grant of 1864 , signed by President Abraham Lincoln on June 30 of that year, was the first time the federal government set aside land specifically for preservation and recreational use. This area became Yosemite National Park in 1890.

The federal government established the world's first national park, Yellowstone National Park, in 1872. However, it did so on lands that native tribes consider sacred, adding another source of dispute between American Indians and the U.S. government (Yellowstone National Park Created on Sacred Land).

The National Park Service was created in 1916. Following the publication of Rachel Carson's seminal book Silent Spring (1962), Congress passed the Clean Air Acts of 1963, 1970 and 1990 along with the Clean Water Act in 1972. There is more historical background and information at a resourcesforhistoryteachers wiki page, The Clean Air Act .

Following the first Earth Day (1970), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was established in 1970. As President, Barack Obama took numerous steps to extend environmental protections (Mother Nature Network, 2016).

Following the election of Joe Biden in 2020, Republican led states (asserting their powers as state governments under federalism) began passing legislation making it harder to reduce dependence on fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas). The state of Florida, for example, passed a bill to prevent the city of Miami from banning natural gas infrastructure in new buildings.

The Biden Administration has responded by pausing new oil and gas leasing on public lands and water and reversing other Trump-era environmental and energy policies. You can track Joe Biden's environmental actions as President at this site from The Washington Post .

- Propose this role for yourself, another student, or a group of students as a school, classroom, or family sustainability ambassador.

- What steps could that person(s) take to improve air and water quality, food safety, waste reduction, and other environmental and climate justice concerns?

- Design a poster or short video explaining the role and its goals.

- What are the limits of states' rights and federal power in matters related to the environment?

- Can states block federal directives?

- Can the federal government ignore state laws?

- Should state governments or the federal government have primary responsibility for modern-day environmental policy?

- How successful were you in preventing a disaster?

- What did you learn about environmental policy choices from playing one of these games?

Online Resources for States' Rights vs. Federal Power in Modern-Day Environmental Politics

- Toxic 100 Names Top Climate, Air and Water Polluters , Political Economy Institute, University of Massachusetts Amherst, July 29, 2019

- How the U.S. Protects the Environment, from Nixon to Trump , The Atlantic (March 29, 2017)

- In Trump Era, Democrats and Republicans Switch Sides on States' Rights, Reuters (January 26, 2017)

- The States Resist Trump's Environmental Agenda , Earth Institute, Columbia University (May 7, 2018)

- Environmental Laws Timeline Activity, American Bar Association

- Take a Poll, Debate the Issue: Environmental Policy , PBS Newshour (May 31, 2016)

- Is the "Right to Clean Water" Fake News? An Inquiry in Media Literacy and Human Rights , Social Studies and the Young Learner (2020)

Standard 2.4 Conclusion

During the writing of the Constitution, Federalists and Anti-Federalists offered sharply diverging visions for the roles of state and federal government, differences which have continued in American politics to the present day. INVESTIGATE outlined the main points of the Federalist-Anti-Federalist debates. UNCOVER examined the political roles of women through the actions of Abigail Adams and Mercy Otis Warren. ENGAGE placed the debates between Federalists and Anti-Federalists in a modern-day context by asking which level of government should have primary responsibility for environmental policies.

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

The United States Constitution: Federalists v. Anti-Federalists

By tim bailey, unit objective.

This unit is part of Gilder Lehrman’s series of Common Core State Standards–based teaching resources. These units were developed to enable students to understand, summarize, and analyze original texts of historical significance. Through a step-by-step process, students will acquire the skills to analyze any primary or secondary source material.

Today students will participate as members of a critical thinking group and "read like a detective" in order to analyze the arguments made by the Federalists in favor of ratifying the new US Constitution.

Introduction

Tell the students that after the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in Philadelphia, the nation’s new Constitution had to be ratified by the states. The debate over ratification became very heated, especially in New York. This led to a spirited exchange of short essays between the Federalists, who promoted the new Constitution, and the Anti-Federalists, who put forward a variety of objections to the proposed new government. Today we will be closely reading excerpts from four of the Federalist Papers in order to discover what the Federalists’ positions and arguments were. Although the Federalist Papers were written anonymously under the pen name "Publius," historians generally agree that the essays were written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay.

- Federalist Papers #1, #10, #51, and #84 (excerpts) . Source: The full text of all the Federalist Papers are available online at the Library of Congress.

- US Constitution, 1787 . Source: Charters of Freedom , National Archives and Records Administration, www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters

- Overhead projector or other display

The students will encounter vocabulary that they do not know. There are words in eighteenth-century essays that many adults do not know the meaning of either. It would be overwhelming to give the definition for every unknown word as well as self-defeating when we are trying to get the students to be more independent learners. One benefit of having the students work in groups is that they can reason out the meanings of words in context together. If the students are truly stuck on a word that is critical to the passage, you can open up a class discussion. As a last resort, you can provide the meaning.

First, a caution: do not reveal too much to the students about the arguments presented by either the Federalists or Anti-Federalists. The point is to let the students discover them through careful reading of the text and discussion with their classmates. They will then construct their own arguments based on the text. Depending on the length of the class period or other factors, this lesson may carry over into tomorrow as well.

- Divide the class into groups of three to five students. These will be the "critical thinking groups" for the next several days.

- Discuss the information in the introduction. The students need to at least be familiar with the failure of the Articles of Confederation, the Constitutional Convention, and the writing of the US Constitution.

- Hand out the four excerpts from Federalist Papers #1, #10, #51, and #84. If possible have a copy up on a document projector so that everyone can see it and you can refer to it easily.

- "Share read" the Federalist Papers with the students. This is done by having the students follow along silently while the teacher begins reading aloud. The teacher models prosody, inflection, and punctuation. The teacher then asks the class to join in with the reading after a few sentences while the teacher continues to read along with the students, still serving as the model for the class. This technique will support struggling readers as well as English language learners (ELL).

- Answers will vary, but in the end the students should conclude that groups interested in "the rights of the people" more often end up as "tyrants."

- Answers will vary, but in the end the students should conclude that the "effects" include "a division of society," and the remedy is the formation of "a republic."

- Answers will vary, but in the end the students should conclude that "such devices [separation of powers] should be necessary to control the abuses of government" and "you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself."

- Answers will vary, but in the end they should conclude that "the Constitution is itself, in every rational sense, and to every useful purpose, A BILL OF RIGHTS . . ."

- Wrap-up: Discuss final conclusions and clarify points of confusion. We want students to be challenged, not overwhelmed.

Today students will participate as members of a critical thinking group and "read like a detective" in order to analyze the arguments made by the Anti-Federalists in opposition to ratifying the new US Constitution.

Review the background information from the last lesson. Today we will be closely reading excerpts from four of the Anti-Federalist Papers in order to discover just what the Anti-Federalists’ positions and arguments were. Although the Anti-Federalists’ essays were written anonymously under various pen names, most famously "Brutus," historians generally agree that among the authors of the Anti-Federalist essays were Robert Yates, Samuel Bryan, George Clinton, and Richard Henry Lee.

- Anti-Federalist Papers #1, #9, #46, and #84 (excerpts) . Source: Morton Borden, ed. The Antifederalist Papers (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1965). Unlike the Federalist Papers, the essays by Anti-Federalists were not conceived of as a unified series. Thus historians have imposed different numbering systems as they compiled various essays; the numbers used here are Morton Borden’s chronology.

- US Constitution, 1787

- Overhead projector or other display method

As in the previous lesson, encourage students to reason out the meanings of words they do not know. If the students are truly stuck on a word that is critical to the passage, you can open up a class discussion. As a last resort, you can provide the meaning.

- Students should sit with their critical thinking groups from the last lesson.

- Discuss the information in the introduction.

- Hand out the four excerpts from Anti-Federalist Papers #1, #9, #46, and #84. If possible have a copy up on a document projector so that everyone can see it and you can refer to it easily.

- "Share read" the Anti-Federalist Papers with the students.

- Answers will vary, but in the end the students should conclude that the "Aristocracy" and "Lawyers" are out to deceive "The People" in order to "satiate their voracious stomachs with the golden bait."

- Answers will vary, but in the end the students should conclude that this Anti-Federalist Paper is a satire and that the evidence includes statements such as "totally incapable of thinking or acting" and "have power over little else than yoking hogs."

- Answers will vary, but in the end the students should conclude that "the Congress are therefore vested with the supreme legislative powers" and "undefined, unbounded and immense power."

- Answers will vary but in the end they should conclude that "but rulers have the same propensities as other men, they are likely to use the power with which they are vested, for private purposes" and "grand security to the rights of the people is not to be found in this Constitution."

The students will deeply understand the major arguments concerning the ratification of the US Constitution. This understanding will be built upon close analysis of the Federalist Papers and Anti-Federalist Papers. The students will demonstrate their understanding in both writing and speaking.

Tell the students that now they get to apply their knowledge and understanding of the Federalist and Anti-Federalist arguments. They will need to select a debate moderator from within their group and divide the remaining students into Federalists and Anti-Federalists. As a group they will write questions based on the issues presented in the primary documents. They will also script responses from both sides based solely on what is written in the documents. This is not an actual debate but rather a scripted presentation for the sake of making arguments that the authors of these documents would have made in a debate format. In the next lesson the groups will present their debates for the class.

- Federalist Papers #1, #10, #51, and #84 (excerpts)

- Anti-Federalist Papers #1, #9, #46, and #84 (excerpts)

Students will be sitting with the same critical thinking group as in the previous two lessons. All of the students should have copies of the excerpts from the Federalist Papers and the Anti-Federalist Papers as well as the United States Constitution as reference materials.

- Tell the students that they need to choose one person to be a debate moderator and then divide the rest of the group into Federalists and Anti-Federalists.

- Inform the students that they will be writing a script for a debate based on the issues raised in the primary documents that you have been studying. This script is to be written as a team effort, and everyone in the group will have a copy of the final script.

- The teacher will provide three questions that all groups must address during the debate. However, the students should add another two to four questions that can be answered directly from the primary source material.

- It is important that the students portraying both the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists use the actual text from the documents to make their arguments.

- What is your position on a bill of rights being added to the Constitution?

- How would you address concerns about the "powers of government" under this new Constitution?

- Can you explain why this Constitution is or is not in the best interests of our nation as a whole?

- Students can then construct their own questions to be directed to either side with the opportunity for rebuttal from the other side.

- Remind the students again that everyone needs to work on the script and the responses must be taken directly from the text of the documents introduced in class.

- Wrap-up: If students have time, let them rehearse their presentations for the next lesson.

The students will demonstrate their knowledge and understanding of the Federalist and Anti-Federalist arguments. This is not an actual debate but a scripted presentation making arguments that the authors of these documents would have made in a debate format.

Students will be sitting with the same critical thinking groups as in the previous three lessons. All of the students should have copies of the excerpts from the Federalist Papers and the Anti-Federalist Papers as well as the United States Constitution as reference materials.

- Tell the students that they will be presenting the debates between the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists that they scripted in the last lesson.

- The Moderator should begin the debate by introducing both sides and setting out the protocol for the "debate." (Actually watching a clip of a debate might be helpful as well.)

- In evaluating the student work you should measure the following: Did the students effectively address all three mandatory questions using text-based evidence? Did the additional questions developed by the students address pertinent issues? Were all of the students in a group involved in the process?

- Wrap-up: As time allows, have students debrief the last four lessons and what they learned.

- OPTIONAL: If you believe that you need to evaluate more individualized understanding of the issues presented over the past four lessons you can have students write a short essay addressing the three mandatory questions that they were given as a group.

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

The Ratification Debate on the Constitution

Written by: Bill of Rights Institute

By the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain the differing ideological positions on the structure and function of the federal government

Suggested Sequencing

Use this Narrative with the Were the Anti-Federalists Unduly Suspicious or Insightful Political Thinkers? Point-Counterpoint and the Federalist/Anti-Federalist Debate on Congress’s Powers of Taxation DBQ Lesson to have students analyze the debate between Federalists and Anti-Federalists.

On September 19, 1787, the Pennsylvania Packet newspaper published the draft of the Constitution for the consideration of the people and their representatives. On September 28, the Confederation Congress voted to send the Constitution to the state legislatures as written, so state conventions could be called to decide whether to ratify the new framework of government.

During the year-long debates over ratification, supporters of the Constitution called themselves Federalists; as a result, their opponents were known as Anti-Federalists. At the center of the often-contentious arguments that took place in homes, taverns, and on the printed page was the federal principle of balancing national and state power. Federalists defended the Constitution’s strengthened national government, with its greater congressional powers, more powerful executive, and independent judiciary. They argued that the new government supported the principles of separation of powers, checks and balances, and federalism. Anti-Federalists, on the other hand, worried that the proposed constitution represented a betrayal of the principles of the American Revolution. Had not Americans fought a war against the consolidation of power in a distant, central government that claimed unlimited powers of taxation? They feared a large republic in which the government, like the Empire from which they had declared independence, was unresponsive to the people. They also feared that a corrupt senate, judiciary, and executive would conspire to form an aristocracy. Finally, they argued against the absence of a bill of rights. States had them, in no small part because they remembered the English Bill of Rights of 1689, which had helped focus attention on the ways in which the British government abused its power.

Through September and October, various Anti-Federalists published essays under pseudonyms like Brutus, Cato, and the Federal Farmer in New York newspapers critiquing the Constitution. Although they did not coordinate their efforts, a coherent set of principles about government and opposition to the proposed Constitution emerged. Alexander Hamilton noted that the “artillery of [the Constitution’s] opponents makes some impression.”

In mid-October, for a series of essays he planned to defend the Constitution from critics, Hamilton enlisted the contributions of Madison, the “father of the Constitution,” as well as John Jay, the president of the Continental Congress and a New York diplomat. The first of these Federalist essays was published in a New York newspaper, under the pseudonym Publius, on October 27. It was addressed to the people of New York but was aimed at the delegates to the state’s Ratifying Convention. In it, Hamilton described the meaning of the choice the states would make:

It seems to have been reserved to the people of this country, by their conduct and example, to decide the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.

Alexander Hamilton, shown in an 1806 portrait by John Trumbull, was the driving force behind The Federalist Paper sand wrote fifty-one of the essays arguing for ratification.

By mid-January, 1788, five states (Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania) had ratified the Constitution. The Federalists were building momentum toward the nine states they needed to win, but they knew the main opposition would come from Anti-Federalists in large and powerful states, including Massachusetts, New York, and Virginia.

The Anti-Federalists were also mounting an effective opposition in essays and debates. Some demanded prior amendments to be sent to a second convention before they would accept the new government. During the debate in Massachusetts, opposition forced the Federalists to promise to consider amendments protecting the liberties of the people after the Constitution was ratified as written. On February 6, Massachusetts became the sixth state to approve the Constitution by a narrow vote of 187 to 168.

In New Hampshire, the Federalists thought they did not have enough votes to ratify, so they strategically adjourned the convention until June so that they could muster more support. Two other states, Maryland and South Carolina, met that spring and overwhelmingly ratified the Constitution, bringing the total to eight. Still, to be considered legitimate the Constitution would need the support of Virginia and New York, because of their political and economic influence and geographical location, even if the approval of nine other states met the constitutional threshold for the new government to go into operation.

On March 22, Hamilton and Madison arranged for the first thirty-six Federalist essays to be published in book form and distributed copies to friends in hope of influencing the delegates to the New York and Virginia ratifying conventions. Because the outcome remained highly uncertain, a second volume including the rest of the eighty-five essays was published on May 28. George Washington praised The Federalist for throwing “new lights upon the science of government” and giving “the rights of man a full and fair discussion.” Thomas Jefferson said it was “the best commentary on the principles of government which ever was written.” The Anti-Federalist essays contributed important reflections on human nature and the character of a republican government in making arguments about why the writers thought the proposed Constitution dangerously expanded the powers of the central government.

When the Virginia Convention met on June 2, a titanic debate took place as two Federalist masters of political debate, Madison and John Marshall, clashed with George Mason and the fiery orator Patrick Henry. Among other Virginians, Washington stayed above the debate, although everyone knew he supported the Constitution, and Jefferson, then in Paris, at first opposed and then supported ratification with prior amendments, because he favored a bill of rights.

Railing against the Constitution, Henry warned that the states would lose their sovereignty in a Union of “we the people” instead of “we the states.” He cautioned that a powerful national government would violate natural rights and civil liberties, thus destroying “the rights of conscience, trial by jury, liberty of the press . . . all pretentions to human rights and privileges, are rendered insecure, if not lost, by this change.” Henry also thundered that the president would lead a standing army against the people.

Madison countered with a line-by-line exposition of the reasoning behind each clause of the Constitution. On June 25, the Virginia Convention voted 89 to 79 for ratification.

Meanwhile, the Anti-Federalists dominated the New York Convention three to one. Hamilton passionately defended the Constitution and urged his allies in Virginia and New Hampshire to send word of the outcomes in those two states by express rider to influence the New York debate. New Yorkers soon learned that the Constitution had officially become the fundamental law of the land for the states adopting it. The question was now whether New York would join the new federal union. On July 26, by a narrow vote of 30 to 27, New York answered in the affirmative, conditionally ratifying the Constitution with a call for another convention to propose a bill of rights. Only after Congress voted in 1789 to send amendments to the states for approval did North Carolina and Rhode Island vote to ratify the new Constitution.

The sovereign people participated in a great deliberative moment in which they ultimately decided to accept a new Constitution with a central government wielding greater powers to protect their rights, safety, and happiness. The formal and informal deliberations about the principles of government defined the republican nature of the new U.S. government. Meanwhile, the spirit of compromise that yielded not only ratification but also, at the urging of Anti-Federalists, the adoption of the Bill of Rights, reflected genuine patriotism by the people who served the public good and suggested that the Americans were capable of self-government.

Review Questions

1. Who of the following were key advocates for the Constitution?

- Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison

- John Jay, George Mason, and James Madison

- Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and Edmund Randolph

- George Mason, Patrick Henry, and Edmund Randolph

2. Who of the following refused to sign the Constitution because, in their opinion, it gave too much power to the federal government?

- George Mason, Elbridge Gerry, and Edmund Randolph

3. What key feature, which many Anti-Federalists argued was essential, was missing from the original Constitution?

- A due process clause

- A decision on the issue of the slave trade

- A bill of rights

- Multiple branches of government

4. Which of the following was the primary source of disagreement between the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists when debating the merits of the Constitution?

- Inclusion of clauses that acknowledge slavery and included slaves in representation

- Size and scope of the federal government balanced with that of the states

- Ability to conduct foreign affairs at the federal level only

- Possibility of the legislative branch requiring taxes at the state level

5. The Anti-Federalists’ distrust of corrupt elite politicians is best exemplified by their adamant insistence on the

- electoral college, which would elect the president

- Supreme Court Justices, who would be elected not appointed

- Bill of Rights, which articulated the rights of each person

- executive position, which would be eligible for reelection

6. One advantage the Federalists had during the ratification debate was that

- many smaller state governments were open to the concept of a stronger federal government

- highly organized authors published essay after essay supporting and explaining the new form of government

- the large and influential states of New York and Virginia were eager to ratify the Constitution as soon as possible

- almost unanimous support for the Constitution existed in every state

7. Many Anti-Federalists argued that the Constitution’s strong national government was

- absolutely necessary to protect the sovereignty of the nation

- too similar to the monarchy from which colonists had fought to be free

- carefully crafted to prevent any abuses of private citizens

- akin to the Articles of Confederation, which required no change

8. How did the debate for ratification ultimately end?

- Not enough states voted to ratify and the Constitution did not become the government of the United States,

- The minimum number of states ratified the Constitution, so it became the law of the land, but only for the states that accepted it.

- Each state ultimately ratified the Constitution, despite close votes and thorough debates.

- Debates continue on the merits of the Constitution, and a few states still need to hold their ratifying convention.

Free Response Questions

- How did the ratification debate demonstrate republicanism in the United States’ founding?

- How was the deliberative process of making and ratifying the Constitution a key moment in the history of republics?

AP Practice Questions

The Federal Pillars.

1. The image shown best supports which argument of the ratification debate?

- The need for a bill of rights to curtail the powers of the central government and guarantee people’s individual liberties

- The potential destruction of deliberation and creation of rival factions

- The view that states need to stand individually without an overarching, omnipotent central government

- The need for states to support and ratify the Constitution to guarantee the existence of a republican union

“In the course of the preceding observations, I have had an eye, my fellow-citizens, to putting you upon your guard against all attempts, from whatever quarter, to influence your decision in a matter of the utmost moment to your welfare, by any impressions other than those which may result from the evidence of truth. You will, no doubt, at the same time, have collected from the general scope of them, that they proceed from a source not unfriendly to the new Constitution. Yes, my countrymen, I own to you that, after having given it an attentive consideration, I am clearly of opinion it is your interest to adopt it. I am convinced that this is the safest course for your liberty, your dignity, and your happiness. I affect not reserves which I do not feel. I will not amuse you with an appearance of deliberation when I have decided. I frankly acknowledge to you my convictions, and I will freely lay before you the reasons on which they are founded. The consciousness of good intentions disdains ambiguity. I shall not, however, multiply professions on this head. My motives must remain in the depository of my own breast. My arguments will be open to all, and may be judged of by all. They shall at least be offered in a spirit which will not disgrace the cause of truth.”

Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist Papers: No. 1 , October 27, 1787

2. Which of the following best describes the purpose of The Federalist essays?

- To promote the advantages of states’ rights

- To convince delegates and people to support the Constitution to secure ratification

- To narrate the ongoing deliberations at the ratification conventions

- To outline characteristics of a new form of government to be included in the Constitution

3. Which of the following is an accurate statement about Anti-Federalist and Federalist beliefs in constitutional principles?

- Anti-Federalists argued for the value of limited central government, whereas Federalists maintained that natural rights to life, liberty, and property would be best protected under a strong central government.

- Anti-Federalists supported the idea of a strong executive elected by the consent of the governed, whereas Federalists argued for states’ rights and cooperation of the states as a confederacy.

- Anti-Federalists asserted that the rule of law would best serve the people of the United States, whereas Federalists promoted a limited government and cooperation of the states.

- Anti-Federalists advocated for republicanism and self-governance, whereas Federalists argued that a representative government could be legitimized only through cooperation with international allies.

“Amendment I. Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances. Amendment II. A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed. Amendment III. No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.”

The United States Bill of Rights, 1789

4. Which of the following pieces of outside evidence provides context for this document?

- Many citizens were concerned that individual rights were not expressed in the Constitution and demanded the addition.

- The Founders wanted to follow in the footsteps of Great Britain by adding a bill of rights.

- Women felt strongly their needs were not being met by the Constitution and held a convention of their own, resulting in this document.

- After intense debate, state conventions decided this document would replace the Constitution.

5. Which of the following did not influence the addition of the Bill of Rights?

- Actions taken by the British government before and during the Revolution inspired some of the amendments.

- State constitutions had articulated many of these rights prior to the Constitution.

- Political factions demanded clarification of inalienable rights to support the Constitution’s ratification.

- The French alliance inspired the founders to adopt the French form of government.

6. Which of the following explains why the amendments provided were not included in the original Constitution?

- State delegations at the Convention argued that additional amendments were unnecessary because most states already had a Bills of Rights.

- The Founders published the Constitution in newspapers and forgot to include the page with these amendments.

- The Founders were influenced by the British tradition of unwritten government that relied on precedent.

- Delegates at the convention were unable to reach a quorum to vote on these items, because the summer was over and many had already headed home.

7. Which political faction primarily advocated the document excerpted previously?

- Federalists

- Anti-Federalists

Primary Sources

Hamilton, Alexander. The Federalist 1 . American History. University of Groningen. http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/documents/1786-1800/the-federalist-papers/the-federalist-1.php

U.S. Constitution . Yale Law School. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/usconst.asp

Suggested Resources

Allen, W.B. and Gordon Lloyd, eds. The Essential Anti-Federalist . Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002.