Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 28 April 2020

The impact a-gender: gendered orientations towards research Impact and its evaluation

- J. Chubb ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9716-820X 1 &

- G. E. Derrick ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5386-8653 2

Palgrave Communications volume 6 , Article number: 72 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

21k Accesses

12 Citations

55 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

A Correction to this article was published on 19 May 2020

This article has been updated

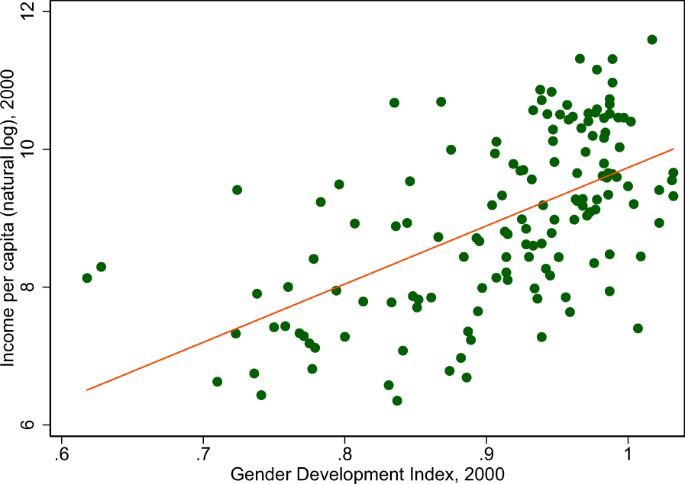

Using an analysis of two independent, qualitative interview data sets: the first containing semi-structured interviews with mid-senior academics from across a range of disciplines at two research-intensive universities in Australia and the UK, collected between 2011 and 2013 ( n = 51); and the second including pre- ( n = 62), and post-evaluation ( n = 57) interviews with UK REF2014 Main Panel A evaluators, this paper provides some of the first empirical work and the grounded uncovering of implicit (and in some cases explicit) gendered associations around impact generation and, by extension, its evaluation. In this paper, we explore the nature of gendered associations towards non-academic impact (Impact) generation and evaluation. The results suggest an underlying yet emergent gendered perception of Impact and its activities that is worthy of further research and exploration as the importance of valuing the ways in which research has an influence ‘beyond academia’ increases globally. In particular, it identifies how researchers perceive that there are some personality traits that are better orientated towards achieving Impact; how these may in fact be gendered. It also identifies how gender may play a role in the prioritisation of ‘hard’ Impacts (and research) that can be counted, in contrast to ‘soft’ Impacts (and research) that are far less quantifiable, reminiscent of deeper entrenched views about the value of different ‘modes’ of research. These orientations also translate to the evaluation of Impact, where panellists exhibit these tendencies prior to its evaluation and describe the organisation of panel work with respect to gender diversity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Unequal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on researchers: evidence from Chile and Colombia

Magdalena Gil, Constanza Hurtado-Acuna, … Alejandra Caqueo-Urízar

The impact of gender diversity on scientific research teams: a need to broaden and accelerate future research

Hannah B. Love, Alyssa Stephens, … Ellen R. Fisher

A bibliometric analysis of the gender gap in the authorship of leading medical journals

Oscar Brück

Introduction

The management and measurement of the non-academic impact Footnote 1 (Impact) of research is a consistent theme within the higher education (HE) research environment in the UK, reflective of a drive from government for greater visibility of the benefits of research for the public, policy and commercial sectors (Chubb, 2017 ). This is this mirrored on a global scale, particularly in Australia, where, at the ‘vanguard’ (Upton et al., 2014 , p. 352) of these developments, methods were first devised (but were subsequently abandoned) to measure research impact (Chubb, 2017 ; Hazelkorn and Gibson, 2019 ). What is broadly known in both contexts as an ‘Impact Agenda’—the move to forecast and assess the ways in which investment in academic research delivers measurable socio-economic benefit—initially sparked broad debate and in some instances controversy, among the academic community (and beyond) upon its inception (Chubb, 2017 ). Since then, the debate has continued to evolve and the ways in which impact can be better conceptualised and implemented in the UK, including its role in evaluation (Stern, 2016 ), and more recently in grant applications (UKRI, 2020 ) is robustly debated. Notwithstanding attempts to better the culture of equality and diversity in research, (Stern, 2016 ; Nature, 2019 ) in the broader sense, and despite the implementation of the Impact agenda being studied extensively, there has been very little critical engagement with theories of gender and how this translates specifically to more downstream gendered inequities in HE such as through an impact agenda.

The emergence of Impact brought with it many connotations, many of which were largely negative; freedom was questioned, and autonomy was seen to be at threat because of an audit surveillance culture in HE (Lorenz, 2012 ). Resistance was largely characterised by problematising the agenda as symptomatic of the marketisation of knowledge threatening traditional academic norms and ideals (Merton, 1942 ; Williams, 2002 ) and has led to concern about how the Impact agenda is conceived, implemented and evaluated. This concern extends to perceptions of gendered assumptions about certain kinds of knowledge and related activities of which there is already a corpus of work, i.e., in the case of gender and forms of public engagement (Johnson et al., 2014 ; Crettaz Von Roten, 2011 ). This paper explores what it terms as ‘the Impact a-gender’ (Chubb, 2017 ) where gendered notions of non-academic, societal impact and how it is generated feed into its evaluation. It does not wed itself to any feminist tradition specifically, however, draws on Carey et al. ( 2018 ) to examine, acknowledge and therefore amend how the range of policies within HE and how implicit power dynamics in policymaking produce gender inequalities. Instead, an impact fluidity is encouraged and supported. For this paper, this means examining how the impact a-gender feeds into expectations and the reward of non-academic impact. If left unchecked, the propagation of the impact a-gender, it is argued, has the potential to guard against a greater proportion of women generating and influencing the use of research evidence in public policy decision-making.

Scholars continue to reflect on ‘science as a gendered endeavour’ (Amâncio, 2005 ). The extensive corpus of historical literature on gender in science and its originators (Merton, 1942 ; Keller et al., 1978 ; Kuhn, 1962 ), note the ‘pervasiveness’ of the ‘masculine’ and the ‘objective and the scientific’. Indeed, Amancio affirmed in more recent times that ‘modern science was born as an exclusively masculine activity’ ( 2005 ). The Impact agenda raises yet more obstacles indicative of this pervasiveness, which is documented by the ‘Matthew’/‘Matilda’ effect in Science (Merton, 1942 ; Rossiter, 1993 ). Perceptions of gender bias (which Kretschmer and Kretschmer, 2013 hypothesise as myths in evaluative cultures) persist with respect to how gender effects publishing, pay and reward and other evaluative issues in HE (Ward and Grant, 1996 ). Some have argued that scientists and institutions perpetuate such issues (Amâncio, 2005 ). Irrespective of their origin, perceptions of gendered Impact impede evaluative cultures within HE and, more broadly, the quest for equality in excellence in research impact beyond academia.

To borrow from Van Den Brink and Benschop ( 2012 ), gender is conceptualised as an integral part of organisational practices, situated within a social construction of feminism (Lorber, 2005 ; Poggio, 2006 ). This article uses the notion of gender differences and inequality to refer to the ‘ hierarchical distinction in which either women and femininity and men and masculinity are valued over the other ’ (p. 73), though this is not precluding of individual preferences. Indeed, there is an emerging body of work focused on gendered associations not only about ‘types’ of research and/or ‘areas and topics’ (Thelwall et al., 2019 ), but also about what is referred to as non-academic impact. This is with particular reference to audit cultures in HE such as the Research Excellence Framework (REF), which is the UK’s system of assessing the quality of research (Morley, 2003 ; Yarrow and Davies, 2018 ; Weinstein et al., 2019 ). While scholars have long attended to researching gender differences in relation to the marketisation of HE (Ahmed, 2006 ; Bank, 2011 ; Clegg, 2008 ; Gromkowska-Melosik, 2014 ; Leathwood et al., 2008 ), and the gendering of Impact activities such as outreach and public engagement (Ward and Grant, 1996 ), there is less understanding of how far academic perceptions of Impact are gendered. Further, how these gendered tensions influence panel culture in the evaluation of impact beyond academia is also not well understood. As a recent discussion in the Lancet read ‘ the causes of gender disparities are complex and include both distal and proximal factors ’. (Lundine et al., 2019 , p. 742).

This paper examines the ways in which researchers and research evaluators implicitly perceive gender as related to excellence in Impact both in its generation and in its evaluation. Using an analysis of two existing data sets; the pre-evaluation interviews of evaluators in the UK’s 2014 Research Excellence Framework and interviews with mid-senior career academics from across the range of disciplines with experience of building impact into funding applications and/ or its evaluation in two research-intensive universities in the UK and Australia between 2011 and 2013, this paper explores the implicitly gendered references expressed by our participants relating to the generation of non-academic, impact which emerged inductively through analysis. Both data sets comprise researcher perceptions of impact prior to being subjected to any formalised assessment of research Impact, thus allowing for the identification of unconscious gendered orientations that emerged from participant’s emotional and more abstract views about Impact. It notes how researchers use loaded terminology around ‘hard’, and ‘soft’ when conceptualising Impact that is reminiscent of long-standing associations between epistemological domains of research and notions of masculinity/femininity. It refers to ‘hard’ impact as those that are associated with meaning economic/ tangible and efficiently/ quantifiably evaluated, and ‘soft’ as denoting social, abstract, potentially qualitative or less easily and inefficiently evaluated. By extending this analysis to the gendered notions expressed by REF2014 panellists (expert reviewers whose responsibility it is to review the quality of the retrospective impact articulated in case studies for the purposes of research evaluation) towards the evaluation of Impact, this paper highlights how instead of challenging these tendencies, shared constructions of Impact and gendered productivity in academia act to amplify and embed these gendered notions within the evaluation outcomes and practice. It explores how vulnerable seemingly independent assessments of Impact are to these widespread gendered- associations between Impact, engagement and success. Specifically, perceptions of the excellence and judgements of feasibility relating to attribution, and causality within the narrative of the Impact case study become gendered.

The article is structured as follows. First, it reviews the gender-orientations towards notions of ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ excellence in forms of scholarly distinction and explores how this relates to the REF Impact evaluation criteria, and the under-representation of women in the academic workforce. Specifically, it hypothesises the role of how gendered notions of excellence that construct academic identities contribute to a system that side-lines women in academia. This is despite associating the generation of Impact as a feminised skill. We label this as the ‘Impact a-gender’. The article then outlines the methodology and how the two, independent databases were combined and convergent themes developed. The results are then presented from academics in the UK and Australia and then from REF2014 panellists. This describes how the Impact a-gender currently operates through academic cultural orientations around Impact generation, and in its evaluation through peer-review panels by members of this same academic culture. The article concludes with a recommendation that the Impact a-gender be explored more thoroughly as a necessary step towards guiding against gender- bias in the academic evaluation, and reward system.

Literature review

Notions of impact excellence as ‘hard’ or ‘soft’.

Scholars have long attempted to consider the commonalities and differences across certain kinds of knowledge (Becher, 1989 , 1994 ; Biglan, 1973a ) and attempts to categorise, divide and harmonise the disciplines have been made (Biglan, 1973a , 1973b ; Becher, 1994 ; Caplan, 1979 ; Schommer–Aikins et al., 2003 ). Much of this was advanced with a typology of the disciplines from (Trowler, 2001 ), which categorised the disciplines as ‘hard’ or ‘soft’. Both anecdotally and in the literature, ‘soft’ science is associated with working more with people and less with ‘things’ (Cassell, 2002 ; Thelwall et al., 2019 ). These dichotomies often lead to a hierarchy of types of Impact and oppose valuation of activities based on their gendered connotations.

Biglan’s system of classifying disciplines into groups based on similarities and differences denotes particular behaviours or characteristics, which then form part of clusters or groups—‘pure’, ‘applied’, ‘soft’, ‘hard’ etc. Simpson ( 2017 ) argues that Biglan’s classification persists as one of the most commonly referred to models of the disciplines despite the prominence of some others (Pantin, 1968 ; Kuhn, 1962 ; Smart et al., 2000 ). Biglan ( 1973b ) classified the disciplines across three dimensions; hard and soft, pure and applied, life and non-life (whether the research is concerned with living things/organisms) . This ‘taxonomy of the disciplines’ states that ‘pure-hard’ domains tend toward the life and earth sciences,’pure-soft’ the social sciences and humanities, and ‘applied hard’ focus on engineering and physical science with ‘soft-applied’ tending toward professional practice such as nursing, medicine and education. Biglan’s classification looked at levels of social connectedness and specifically found that applied scholars Footnote 2 were more socially connected, more interested and involved in service activities, and more likely to publish in the form of technical reports than their counterparts in the pure (hard) areas of study. This resonates with how Impact brings renewed currency and academic prominence to applied researchers (Chubb, 2017 ). Historically, scholars inhabiting the ‘hard’ disciplines had a greater preference for research; whereas, scholars representing soft disciplines had a greater preference for teaching (Biglan, 1973b ). Further, Biglan ( 1973b ) also found that hard science scholars sought out greater collaborative efforts among colleagues when teaching as opposed to their soft science counterparts.

There are also long-standing gendered associations and connotations with notions of ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ (Storer, 1967 ). Typically used to refer to skills, but also used heavily with respect to the disciplines and knowledge domains, gendered assumptions and the mere use of ‘hard’ or ‘soft’ to describe knowledge production carries with it assumptions, which are often noted in the literature; ‘ we think of physics as hard and of political science as soft ’, Storer explains, adding how ‘hard seems to imply tough, brittle, impenetrable and strong, while soft on the other hand calls to mind the qualities of weakness, gentleness and malleability’ (p. 76). As described, hard science is typically associated with the natural sciences and quantitative paradigms whereas normative perceptions of feminine ‘soft’ skills or ‘soft’ science are often equated with qualitative social science. Scholars continue to debate dichotomised paradigms or ‘types’ of research or knowledge (Gibbons, 1999 ), which is emblematic of an undercurrent of epistemological hierarchy of the value of different kinds of knowledge. Such debates date back to the heated back and forth between scholars Snow (Snow, 2012 ) and literary critic Leavis who argued for their own ‘cultures’ of knowledge. Notwithstanding, these binary distinctions do few favours when gender is then ascribed to either knowledge domain or related activity (Yarrow and Davies, 2018 ). This is particularly pertinent in light of the current drive for more interdisciplinary research in the science system where there is also a focus on fairness, equality and diversity in the science system.

Academic performance and the Impact a-gender

Audit culture in academia impacts unfairly on women (Morley, 2003 ), and is seen as contributory to the wide gender disparities in academia, including the under-representation of women as professors (Ellemers et al., 2004 ), in leadership positions (Carnes et al., 2015 ), in receiving research acknowledgements (Larivière et al., 2013 ; Sugimoto et al., 2015 ), or being disproportionately concentrated in non-research-intensive universities (Santos and Dang Van Phu, 2019 ). Whereas gender discrimination also manifests in other ways such as during peer review (Lee and Noh, 2013 ), promotion (Paulus et al., 2016 ), and teaching evaluations (Kogan et al., 2010 ), the proliferation of an audit culture links gender disparities in HE to processes that emphasise ‘quantitative’ analysis methods, statistics, measurement, the creation of ‘experts’, and the production of ‘hard evidence’. The assumption here is that academic performance and the metrics used to value, and evaluate it, are heavily gendered in a way that benefits men over women, reflecting current disparities within the HE workforce. Indeed, Morely (2003) suggests that the way in which teaching quality is female dominated and research quality is male dominated, leads to a morality of quality resulting in the larger proportion of women being responsible for student-focused services within HE. In addition, the notion of ‘excellence’ within these audit cultures implicitly reflect images of masculinity such as rationality, measurement, objectivity, control and competitiveness (Burkinshaw, 2015 ).

The association of feminine and masculine traits in academia (Holt and Ellis, 1998 ), and ‘gendering its forms of knowledge production’ (Clegg, 2008 ), is not new. In these typologies, women are largely expected to be soft-spoken, nurturing and understanding (Bellas, 1999 ) yet often invisible and supportive in their ‘institutional housekeeping’ roles (Bird et al., 2004 ). Men, on the other hand are often associated with being competitive, ambitious and independent (Baker, 2008 ). When an individual’s behaviour is perceived to transcend these gendered norms, then this has detrimental effects on how others evaluate their competence, although some traits displayed outside of these typologies go somewhat ‘under the radar’. Nonetheless, studies show that women who display leadership qualities (competitiveness, ambition and decisiveness) are characterised more negatively than men (Rausch, 1989 ; Heilman et al., 1995 ; Rossiter, 1993 ). Incongruity between perceptions of ‘likeability’ and ‘competence’ and its relationship to gender bias is present in evaluations in academia, where success is dependent on the perceptions of others and compounded within an audit culture (Yarrow and Davis, 2018). This has been seen in peer review, reports for men and women applicants, where women were disadvantaged by the same characteristics that were seen as a strength on proposals by men (Severin et al., 2019 ); as well as in teaching evaluations where women receive higher evaluations if they are perceived as ‘nurturing’ and ‘supportive’ (Kogan et al., 2010 ). This results in various potential forms of prejudice in academia: Where traits normally associated with masculinity are more highly valued than those associated with femininity (direct) or when behaviour that is generally perceived to be ‘masculine’ is enacted by a woman and then perceived less favourably (indirect/ unconscious). That is not to mention direct sexism, rather than ‘through’ traits; a direct prejudice.

Gendered associations of Impact are not only oversimplified but also incredibly problematic for an inclusive, meaningful Impact agenda and research culture. Currently, in the UK, the main funding body for research in the UK, UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) uses a broad Impact definition: ‘ the demonstrable contribution that excellent research makes to society and the economy ’ (UKRI website, 2019 ). The most recent REF, REF2014, Impact was defined as ‘ …an effect on, change or benefit to the economy, society, culture, public policy or services, health, the environment or quality of life, beyond academia ’. In Australia, the Australian Research Council (ARC) proposed that researchers should ‘embed’ Impact into the research process from the outset. Both Australia and the UK have been engaged in policy borrowing around the evaluation of societal impact and share many similarities in approaches to generating and evaluating it. Indeed, Impact has been deliberately conceptualised by decision-makers, funders and governments as broad in order to increase the appearance of being inclusivity, to represent a broad range of disciplines, as well as to reflect the ‘diverse ways’ that potential beneficiaries of academic research can be reached ‘beyond academia’. The adoption of societal impact as a formalised criterion in the evaluation of research excellence was initially perceived to be potentially beneficial for women, due to its emphasis on concepts such as ‘public engagement’; ‘duty’ and non-academic ‘cooperation/collaboration’ (Yarrow and Davies, 2018 ). In addition, the adoption of narrative case studies to demonstrate Impact, rather than adopting a complete metrics-focused exercise, can also be seen as an opportunity for women to demonstrate excellence in the areas where they are over-represented, such as teaching, cultural enrichment, public engagement (Andrews et al., 2005 ), informing public policy and improving public services (Schatteman, 2014 ; Wheatle and BrckaLorenz, 2015). However, despite this, studies highlight how for the REF2014, only 25% of Impact Case Studies for business and management studies were from women (Davies et al., 2020 ).

With respect to Impact evaluation, previous research shows that there is a direct link between notions of academic culture, and how research (as a product of that culture) is valued and evaluated (Leathwood and Reid, 2008 ; p. 120). Geertz ( 1983 ) argues that academic membership is a ‘cultural frame that defines a great part of one’s life’ influences belief systems around how academic work is orientated. This also includes gendered associations implicit in the academic reward system, which in turn influences how academics believe success is to be evaluated, and in what form that success emerges. This has implications in how academic associations of the organisation of research work and the ongoing constructions of professional identity relative to gender, feeds into how these same academics operate as evaluators within a peer review system evaluation. In this case, instead of operating to challenge these tendencies, shared constructions of gendered academic work are amplified to the extent that they unconsciously influence perceptions of excellence and the judgements of feasibility as pertaining to the attribution and causality of the narrative argument. As such, in an evaluation of Impact with its ambiguous definition (Derrick, 2018 ), and the lack of external indicators to signal success independent of cultural constructions inherent in the panel membership, effects are assumed to be more acute. In this way, this paper argues that the Impact a-gender can act to further disadvantage women.

The research combines two existing research data sets in order to explore implicit notions of gender associated with the generation and evaluation of research Impact beyond academia. Below the two data sets and the steps involved in analysing and integrating findings are described along with our theoretical positioning within the feminist literature Where verbatim quotation is used, we have labelled the participants according to each study highlighting their role and gender. Further, the evaluator interviews specify the disciplinary panel and subpanel to which they belonged, as well as their evaluation responsibilities such as: ‘Outputs only’; ‘Outputs and Impact’; and ‘Impacts only’.

Analysis of qualitative data sets

This research involved the analysis and combination of two independently collected, qualitative interview databases. The characteristics and specifics of both databases are outlined below.

Interviews with mid-senior academics in the UK and Australia

Fifty-one semi-structured interviews were conducted between 2011 and 2013 with mid-senior academics at two research-intensive universities in Australia and the UK. The interviews were 30–60 min long and participants were sourced via the research offices at both sites. Participants were contacted via email and invited to participate in a study concerning resistance towards the Impact agenda in the UK and Australia and were specifically asked for their perceptions of its relationship with freedom, value and epistemic responsibility and variations across discipline, career stage and national context. Mostly focused on ex ante impact, some interviewees also described their experiences of Impact in the UK and Australia, in relation to its formal assessment as part of the Excellence Innovation Australia (EIA) for Australia and the Research Excellence Framework (REF) in the UK.

Participants comprised mid to senior career academics with experience of winning funding from across the range of disciplines broadly representative of the arts and humanities, social sciences, physical science, maths and engineering and the life and earth sciences. For the purposes of this paper, although participant demographic information was collected, the relationship between the gender of the participants, their roles, disciplines/career stage was not explicitly explored instead, such conditions were emergent in the subsequent inductive coding during thematic analysis. A reflexive log was collected in order to challenge and draw attention to assumptions and underlying biases, which may affect the author, inclusive of their own gender identity. Further information on this is provided in Chubb ( 2017 ).

Pre- and post-evaluation interviews with REF2014 evaluators

REF2014 in the UK represented the world’s first formalised evaluation of ex-post impact, comprising of 20% of the overall evaluation. This framework served as a unique experimental environment with which to explore baseline tendencies towards impact as a concept and evaluative object (Derrick, 2018 ).

Two sets of semi-structured interviews were conducted with willing participants: sixty-two panellists were interviewed from the UK’s REF2014 Main Panel A prior to the evaluation taking place; and a fifty-seven of these were re-interviewed post-evaluation. Main Panel A covers six Sub-panels: (1) Clinical Medicine; (2) Public Health, Health Services and Primary Care; (3) Allied Health Professions, Dentistry, Nursing and Pharmacy; (4) Psychology, Psychiatry and Neuroscience; (5) Biological Sciences; and (6) Agriculture, Veterinary and Food Sciences. Again, the relationship between the gender of the participants and their discipline is not the focus for the purposes of this paper.

Database combination and identification of common emergent themes

The inclusion of data sets using both Australian and UK researchers was pertinent to this study as both sites were at the cusp of implementing the evaluation of Impact formally. These researcher interviews, as well as the evaluator interviews were conducted prior to any formalised Impact evaluation took place, but when both contexts required ex ante impact in terms of certain funding allocation, meaning an analysis of these baseline perceptions between databases was possible. Further, the inclusion of the post-evaluation interviews with panellists in the UK allowed an exploration of how these gendered perceptions identified in the interviews with researchers and panellists prior to the evaluation, influenced panel behaviour during the evaluation of Impact.

Initially, both data sets were analysed using similar, inductive, grounded-theory-informed approaches inclusive of a discourse and thematic analysis of the language used by participants when describing impact, which allowed for the drawing out of metaphor (Zinken et al., 2008 ). This allowed data combination and analysis of the two databases to be conducted in line with the recommendations for data-synthesis as outlined in Weed ( 2005 ) as a form of interpretation. This approach guarded against the quantification of qualitative findings for the purposes of synthesis, and instead focused on an initial dialogic approach between the two authors (Chubb and Derrick), followed by a re-analysis of qualitative data sets (Heaton, 1998 ) in line with the outcomes of the initial author-dialogue as a method of circumventing many of the drawbacks associated with qualitative data-synthesis. Convergent themes from each, independently analysed data set were discussed between authors, before the construction of new themes that were an iterative analysis of the combined data set. Drawing on the feminist tradition the authors did not apply feminist standpoint theory, instead a fully inductive approach was used to unearth rich empirical data. An interpretative and inductive approach to coding the data using NVIVO software in both instances was used and a reflexive log maintained. The availability of both full, coded, qualitative data sets, as well as the large sample size of each, allowed this data-synthesis to happen.

Researcher’s perceptions of Impact as either ‘hard’ or ‘soft’

Both UK and Australian academic researchers (researchers) perceive a guideline of gendered productivity (Davies et al., 2017 ; Sax et al., 2002 ; Astin, 1978 ; Ward and Grant, 1996 ). This is where men or women are being dissuaded (by their inner narratives, their institutions or by colleagues) from engaging in Impact either in preference to other (more masculine) notions of academic productivity, or towards softer (for women) because they consider themselves and are considered by others to be ‘good at it’. Participants often gendered the language of Impact and introduced notions of ‘hard’ and ‘soft’. On the one hand, this rehearses and resurfaces long-standing views about the ‘Matthew Effect’ because often softer Impacts were seen as being of less value by participants, but also indicates that the word impact itself carries its own connotations, which are then weighed down further by more entrenched gender associations.

Our research shows that when describing Impact, it was not necessarily the masculinity or femininity of the researcher that was emphasised by participants, rather researchers made gendered presumptions around the type of Impact, or the activity used to generate it as either masculine or feminine. Some participants referred to their own research or others’ research as either ‘hard’ or as ‘soft and woolly’. Those who self-professed that their research was ‘soft’ or woolly’ felt that their research was less likely to qualify as having ‘hard’ impact in REF terms Footnote 3 ; instead, they claimed their research would impact socially, as opposed to economically; ‘ stuff that’s on a flaky edge — it’s very much about social engagement ’ (Languages, Australia, Professor, Male) . One researcher described Impact as ‘a nasty Treasury idea,’ comparing it to: a tsunami, crashing over everything which will knock out stuff that is precious ’ . (Theatre, Film and TV, UK, Professor, Male) . This imagery associates the concept of impact with force and weight (or hardness as mentioned earlier) particularly in disciplines where the effect of their research may be far more nuanced and subtle. One Australian research used force to depict the impact of teaching and claimed Impact was like a footprint, and teaching was ‘ a pretty heavy imprint ’ (Environment, UK, Professor, Male) . Participants characterised ‘force and weight’ as masculine, suggesting that some connotations of Impact and the associated activities may be gendered. The word ‘Impact’ was inherently perceived by many researchers as problematic, bound with linguistic connotations and those imposed by the official definitions, which in many cases are perceived as negative or maybe even gendered (Chubb, 2017 ): ‘ The etymology of a word like impact is interesting. I’ve always seen what I do as being a more subtle incremental engagement, relevance, a contribution ’. (Theatre, Film and TV, UK, Professor, Male) .

Researchers associated the word ‘impact’ with hard-ness, weight and force; ‘ anything that sorts of hits you ’ (Languages, UK, Senior Lecturer, Female) . One researcher suggested that Impact ‘ sounds kind of aggressive — the poor consumer! ’ (History, Australia, Professor, Female) . Talking about her own research in the performing arts, one Australian researcher commented: ‘ It’s such a pain in the arse because the Arts don’t fit the model. But in a way they do if you look at the impact as being something quite soft ’ (Music, Australia, Professor, Female) . Likewise, a similar comparison was seen by a female researcher from the mechanical engineering discipline: ‘ My impact case study wasn’t submitted mainly because I’m dealing with that slightly on the woolly side of things ’ (Mechanical Engineering, Australia, Professor, Female) . Largely, gender related comments hailed from the ‘hard’ science and from arts and humanities researchers. Social scientists commented less, and indeed, one levelled that Impact was perhaps less a matter of gender, and more a matter of ability (Chubb, 2017 ): ‘ It’s about being articulate! Both guys and women who are very articulate and communicate well are outward looking on all of these things ’ ( Engineering Education, Australia, Professor, Female).

Gendered notions of performativity were also very pronounced by evaluators who were assessing the outputs only, suggesting how these panel cultures are orientated around notions of gender and scientific outputs as ‘hard’ if represented by numbers. The focus on numbers was perceived by the following panellist as ‘ a real strong tendency particularly amongst the Alpha male types ’ within the panel that relate to findings about the association of certain traits—risk aversion, competitiveness, for example, with a masculinised market logic in HE;

And I like that a lot because I think that there is a real strong tendency particularly amongst the Alpha male types of always looking at the numbers, like the numbers and everything. And I just did feel that steer that we got from the panel chairs, both of them were men by the way, but they were very clear, the impact factors and citations and the rank order of a journal is this is information that can be useful, but it’s not your immediate first stop. (Panel 1, Outputs and Impact, Female)

However, a metric-dominant approach was not the result of a male-dominated panel environment and instead, to the panels credit, evaluators were encouraged not to use one-metric as the only deciding factor between star-rating of quality. However, this is not to suggest that metrics did not play a dominant role. In fact, in order to resolve arguments, evaluators were encouraged to ‘ reflect on these other metrics ’ (Panel 3, Outputs only, Male) in order to rectify arguments where the assessment of quality was in conflict. This use of ‘other metrics’ was preferential to a resolution of differences that are based on more ‘soft’ arguments that are based on understanding where differences in opinion might lie in the interpretation of the manuscript’s quality. Instead, the deciding factor in resolving arguments would be the responsibility, primarily, of a ‘hard’ concept of quality as dictated by a numerical value;

Read the paper, judge the quality, judge the originality, the rigour, the impact — if you have to because you’re in dispute with another assessor, then reflect on these other metrics. So I don’t think metrics are that helpful actually if and until you’ve got a real issue to be able to make a decision. But I worry very much that metrics are just such a simple way of making the process much easier, and I’m worried about that because I think there’s a bit of game playing going on with impact factors and that kind of thing. (Panel 3, Outputs Only, Male)

Table 1 outlines the emergent themes, which, through inductive coding participants broadly categorised domains of research, their qualities and associations, types of activities and the gendered assumption generally made by participants when describing that activity. The table is intended only to provide an indicative overview of the overall tendencies of participants toward certain narratives as is not exhaustive, as well as a guide to interpret the perceptions of Impact illustrated in the below results.

Table one describes the dichotomous views that seemed to emerge from the research but it’s important to note that researchers associated Impact as related to gender in subtle, and in some cases overt ways. The data suggests that some male participants felt that female academics might be better at Impact, suggesting that female academics might find it liberating, linked it to a sense of duty or public service, implying that it was second nature. In addition, some male participants associated types of Impact domains as female-orientated activity and the reverse was the case with female and male-orientated ‘types’ of Impact. For example, at one extreme, a few male researchers seemed to perceive public engagement as something, which females would be particularly good at, generalising that they are not competitive ‘ women are better at this! They are less competitive! ’ (Environment, UK, Professor, Male) . Indeed, one male researcher suggested that competitiveness actually helps academics have an impact and does not impede it:

I get a huge buzz from trying to communicate those to a wider audience and winning arguments and seeing them used. It’s not the use that motivates me it’s the process of winning, I’m competitive! (Economics, UK, Professor, Male)

Analysis also revealed evidence that some researchers has gendered perceptions of Impact activities just as evaluators did. Here, women were more likely to promote the importance of engaging in Impact activities, whereas men were focused on producing indicators with hard, quantitative indicators of success. Some researchers implied that public engagement was not something entirely associated with the kinds of Impact needed to advance one’s career and for a few male researchers, this was accordingly associated with female academics. Certain female researchers in the sciences and the arts suggested similarly that there was a strong commitment among women to carry out public engagement, but that this was not necessarily shared by their male counterparts who, they perceived, undervalued this kind of work:

I think the few of us women in the faculty will grapple with that a lot about the relevance of what we’re doing and the usefulness, but for the vast majority of people it’s not there… [She implies that]…I think there is a huge gender thing there that every woman that you talk to on campus would consider that the role of the university is along the latter statement (*to communicate to the public). The vast majority of men would not consider that’s a role of the university. There’s a strong gender thing. (Chemical Engineering, Australia, Professor, Female)

Notwithstanding, it is important to distinguish between engagement and Impact. This research shows that participants perceive Impact activities to be gendered. There was a sense from one arts female researcher that women might be more interested in getting out there and communicating their work but that crucially, it is not the be-all and end- all of doing research: ‘ Women feel that there’s something more liberating, I can empathise with that, but that couldn’t be the whole job ’. Music, Australia, Professor, Female Footnote 4 . When this researcher, who was very much orientated towards Impact, asked if there were enough interviewees, she added ‘ mind you, you’ve probably spoken to enough men in lab coats ’. This could imply that inward-facing roles are associated with male-orientated activity and outward facing roles as perceived as more female orientated. Such sentiments perhaps relate to a binary delineation of women as more caring, subjective, applied and of men as harder, scientific and theoretical/ rational. This links to a broader characterisation of HE as marketised and potentially, more ‘male’ or at least masculinised—where increasing competitiveness, marketisation and performativity can be seen as linked to an increasingly macho way of doing business (Blackmore, 2002 ; Deem, 1998 ; Grummell et al., 2009 ; Reay, n.d. ). The data is also suggestive of the attitude that communication is a ‘soft’ skill and the interpersonal is seen as a less masculine trait. ‘ This is a huge generalisation but I still say that the profession is so dominated by men, undergraduates are so dominated by men and most of those boys will come into engineering because they’re much more comfortable dealing with a computer than with people ’ (Chemical Engineering, Australia, Professor, Female) . Again, this suggests women are more likely to pursue those scientific subjects, which will make a difference or contribute to society (such as nursing or environmental research, certainly those subjects that would be perceived as less ‘hard’ science domains).

There was also a sense that Impact activity, namely in this case public engagement and community work, was associated with women more than men by some participants (Amâncio, 2005 ). However, public engagement and certain social impact domains appeared to have a lower status and intellectual worth in the eyes of some participants. Some inferred that social and ‘soft’ impacts are seen as associated. With discipline. For instance, research concerning STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Medicine) subjects with females. They in turn may be held in low esteem. Some of the accounts suggest that soft impacts are perceived by women as not ‘counting’ as Impact:

‘ At least two out of the four of us who are female are doing community service and that doesn’t count, we get zero credit, actually I would say it gets negative credit because it takes time away from everything else ’. (Education Engineering, Australia, Professor, Female)

This was intimated again by another female UK computer scientist who claimed that since her work was on the ‘woolly side’ of things, and her impacts were predominantly in the social and public domain, she would not be taken seriously enough to qualify as a REF Impact case study, despite having won an award for her work:

‘ I don’t think it helps that if I were a male professor doing the same work I might be taken more seriously. It’s interesting, why recently? Because I’ve never felt that I’ve not been taken seriously because I’m a woman, but something happened recently and I thought, oh, you’re not taking me seriously because I’m a woman. So I think it’s a part ’. (Computer Science, UK, Professor, Female)

Researchers also connect the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ associations with Impact described earlier to male and female traits. The relationship between Impact and gender is not well understood and it is not clear how much these issues are directly relatable to Impact or more symptomatic of the broader picture in HE. In order to get a broader picture, it is important to examine how these gendered notions of Impact translate into its evaluation. Some participants suggested that gender is a factor in the securing of grant money—certainly this comment reveals a local speculation that ‘the big boys’ get the grants, in Australia, at least: ‘ ARC grants? I’ve had a few but nothing like the big boys that get one after the other ,’ (Chemical Engineering, Australia, Professor, Female) . This is not dissimilar to the ‘alpha male’ comments from the evaluators described below who note a tendency for male evaluators to rely on ‘hard’ numbers whose views are further examined in the following section.

Gendered excellence in Impact evaluation

In the pre-evaluation interviews, panellists were asked about what they perceived to be ‘excellent’ research and ‘excellent’ Impact. Within this context, are mirrored conceptualisations of impacts as either ‘soft’ or ‘hard’ as was seen with the interviews with researchers described above. These conceptualisations were captured prior to the evaluation began. They can therefore be interpreted as the raw, baseline assumptions of Impact that are free from the effects of the panel group, showed that there were differences in how evaluators perceived Impact, and that these perceptions were gendered.

Although all researchers conceptualised Impact as a linear process for the purposes of the REF2014 exercise (Derrick, 2018 ), there was a tendency for female evaluators to be open to considering the complexity of Impact, even in a best-case scenario. This included a consideration that Impact as dictated within the narrative might have different indicators of value to different evaluators; ‘ I just think that that whole framing means that there is a form of normative standard of perfect impact ’ (Main Panel, Outputs and Impacts, Female) . This evaluator, in particular, went further to state how that their impression of Impact would be constructed from the comparators available during the evaluation;

‘ Given that I’m presenting impact as a good story, it would be like you saying to me; ‘Can you describe to me a perfect Shakespearean play?’…. well now of course, I can’t. You can give me lots of plays but they all have different kinds of interesting features. Different people would say that their favourite play was different. To me, if you’re taking interpretivist view, constructivist view, there is no perfect normative standard. It’s just not possible ’. (Panel 1, Outputs and Impacts, Female)

Female evaluators were also more sensitive to other complex factors influencing the evaluation of Impact, including time lag; ‘ …So it takes a long time for things like that to be accepted…it took hundreds of studies before it was generally accepted as real ’ (Panel 1, Outputs and Impacts, Female ); as well as the indirect way that research influences policy as a form of Impact;

‘ I don’t think that anything would get four stars without even blinking. I think that is impossible to answer because you have to look at the whole evidence in this has gone on, and how that does link to the impact that is being claimed, and then you would then have to look at how that impact, exactly how that research has impacted on the ways of the world, in terms of change or in terms of society or whatever. I don’t think you can see this would easily get four stars because of the overall process is being looked at, as well as the actual outcome ’ . (Panel 3, Outputs and Impact, Female)

Although these typologies were not absolute, there was a lack of complexity in the nuances around Impact. There was also heavily gendered language around Impacts as measurable, or not, that mirrored the association of Impact as being either ‘hard’, and therefore measurable, or ‘soft, and therefore more nuanced in value. In this way, male evaluators expressed Impact as a causal, linear event that occurred ‘ in a very short time ’ (P2, Outputs and Impact, Male) and involved a single ‘ star ’ (P3, Impacts only, Male) or ‘ impact champion ’ (Main Panel, Outputs and Impacts, Male) that drove it from start (research), to finish (Impact). These associations about Impact being ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ made by evaluators, mirror the responses from researchers in the above sections. In the example below, the evaluator used words such as ‘ strong ’ and ‘ big way ’ to describe Impact success, as well as emphasises causality in the argument;

‘ …if it has affected a lot of people or affected policy in a strong way or created change in a big way, and it can be clearly linked back to the research, and it’s made a difference ’. (Panel 2, Outputs and Impact, Male)

These perhaps show disciplinary differences as much as gendered differences. Further, there was a stronger tendency for male evaluators to strive towards conceptualisations of excellence in Impact as measurable or ‘ it’s something that is decisive and actionable ’ (Panel 6, Impacts, Male) . One male evaluator explained his conceptualised version of Impact excellence as ‘ straightforward ’ and therefore ‘ obviously four-star ’ due to the presence of metrics with which to measure Impact. This was a perception more commonly associated with male evaluators;

‘ …if somebody has been able to devise a — let’s say pancreatic cancer — which is a molecular cancer, which hasn’t made any progress in the last 40 years, and where the mortality is close to 100% after diagnosis, if someone devised a treatment where now suddenly, after diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, 90 percent of the people are now still alive 5 years later, where the mortality rate is almost 0%, who are alive after 5 years. That, of course, would be a dramatic, transformative impact ’. (Panel 1, Outputs and Impact, Male)

In addition, his tendency to seek various numeric indicators for measuring, and therefore assessing Impact (predominantly economic impact), as well as compressing its realisation to a small period of time ( ‘ suddenly ’ ) in a causal fashion, was more commonly expressed in male evaluators. This tendency automatically indicates the association of impacts as either ‘soft’ or ‘hard’ and divided along gendered norms, but also expresses Impact in monetary terms;

‘ Something that went into a patient or the company has pronounced with…has spun out and been taken up by a commercial entity or a clinical entity ’ (Panel 3, Outputs and Impacts, Male) , as well as impacts that are marketised; ‘ A new antimicrobial drug to market ’. (Panel 6, Outputs and Impact, Male) .

There was also the perception that female academics would be better at engagement (Johnson et al., 2014 ; Crettaz Von Roten, 2011 ) due to its link with notions of ‘ duty ’ (as a mother), ‘ engagement ’ and ‘ public service ’ are reflected in how female evaluators were also more open to the idea that excellent Impact is achieved through productive, ongoing partnerships with non-academic stakeholders. Here, the reflections of ‘duty’ from the evaluators was also mirrored by in interviews with researchers. Indeed, the researchers merged perceptions of parenthood, an academic career and societal impact generation. One female researcher drew on her role as a mother as supportive of her ability to participate in Impact generation, ‘ I have kids that age so… ’ (Biology, UK, Senior Lecturer, Female) . Indeed, parenthood emerged from researchers of both genders in relation to the Impact agenda. Two male participants spoke positively about the need to transfer knowledge of all kinds to society referencing their role as parents: ‘ I’m all for that. I want my kids to have a rich culture when they go to school ’ (Engineering, Australia, Professor, Male, E2) , and ‘ My children are the extension of my biological life and my students are an extension of my thoughts ’ (Engineering, Australia, Professor, Male, E1) . One UK female biologist commented that she indeed enjoys delivering public engagement and outreach and implies a reference to having a family as enabling her ability to do so: ‘ It’s partly being involved with the really well-established outreach work ,’ (Biology, UK, Senior Lecturer, Female) .

For the evaluators, the idea that ‘public service’ as second nature for female academics, was reflected in how female evaluators perceived the long, arduous and serendipitous nature of Impact generation, as well as their commitment to assessing the value of Impact as a ‘pathway’ rather than in line with impact as a ‘product’. Indeed, this was highlighted by one male evaluator who suggested that the measurement and assessment of Impact ‘ …needs to be done by economists ’ and that

‘ you [need] to put in some quantification one everything…[that] puts a negative value on being sick and a positive large value on living longer. So, yeah, the greatest impact would be something that saves us money and generates income for the country but something broad and improves quality of life ’. (Panel 2, Impacts, Male)

Since evaluators tend to exercise cognitive bias in evaluative situations (Langfeldt, 2006 ), these preconceived ideas about Impact, its generation and the types of people responsible for its success are also likely to permeate the evaluative deliberations around Impact during the peer review process. What is uncertain is the extent that these messages are dominant within the panel discourse, and therefore the extent that they influence the formation of a consensus within the group, and the ‘dominant definition’ of Impact (Derrick, 2018 ) that emerges as a result.

Notions of gender from the evaluators post-evaluation

Similar notions of gender-roles in academia pertaining to notions of scientific productivity were echoed by academics who were charged with its evaluation as part of the UK’s 2014 Research Excellence Framework. Interviews with evaluators revealed not only that the panel working-methods and characteristics about what constituted a ‘good’ evaluator were implicitly along gendered norms, but also that the assumed credit assumptions of performativity were also based on gender.

In assessments of the Impact criterion, an assessment that is not as amenable to quantitative representation requiring panels to conceptualise a very complex process, with unstandardised measures of significance and reach, there was still a gendered perception of Impact being ‘women’s work’ in academia. This perception was based on the tendency towards conceptualising Impact as ‘slightly grubby’ and ‘not very pure’, which echoes previously reported pre-REF2014 tensions that Impact is a task that an academic does when they cannot do real research (de Jong et al., 2015 );

But I would say that something like research impact is — it seems something slightly grubby. It’s not seen as not — by the academics, as not very pure. To some of them, it seems women’s work. Talking to the public, do you see what I mean? (Main Panel, Outputs and Impact, Female)

In addition, gendered roles also relate to how the panel worked with the assessment of Impact. Previous research has outlined how the equality and diversity assessment of panels for REF2014 were not conducted until after panellists were appointed (Derrick, 2018 ), leading to a lack of equal-representation of women on most panels. Some of the female panellists reflected that this resulted not only in a hyper-awareness of one’s own identity and value as a woman on the panel, but also implicitly associating the role that a female panellist would play in generating the evaluation. One panellist below, reflected that she was the only female in a male-dominated panel, and that the only other females in the room were the panel secretariat. The panellist goes further to explain how this resulted in a gendered-division of labour surrounding the assessment of Impact;

I mean, there’s a gender thing as well which isn’t directing what you’re talking about what you’re researching, but I was the only woman on the original appointed panel. The only other women were the secretariat. In some ways I do — there was initially a very gendered division of perspective where the women were all the ones aggregate the quantitative research, or typing it all up or talking about impact whereas the men were the ones who represented the big agenda, big trials. (Main Panel, Outputs and Impact, Female)

In addition, evaluators expressed opinions about what constituted a good and a bad panel member. From this, the evaluation showed that traits such as the ability to work as a ‘team’ and to build on definitions and methods of assessment for Impact through deliberation and ‘feedback’ were perceived along gendered lines. In this regard, women perceived themselves as valuable if they were ‘happy to listen to discussions’, and not ‘too dogmatic about their opinion’. Here, women were valued if they played a supportive, supplementary role in line with Bellas ( 1999 ), which was in clear distinction to men who contributed as creative thinkers and forgers of new ideas. As one panellist described;

A good panel member is an Irish female. A good panel member was someone who was happy to — someone who is happy to listen to discussions; to not be too dogmatic about their opinion, but can listen and learn, because impact is something we are all learning from scratch. Somebody who wasn’t too outspoken, was a team player. (Panel 3, Outputs and Impact, Female)

Likewise, another female evaluator reflected on the reasons for her inclusion as a panel member was due to her ‘generalist perspective’ as opposed to a perspective that is over prescribed. This was suggestive of how an overly specialist perspective would run counter to the reasons that she was included as a panellist which was, in her opinion, due to her value as an ethnic and gender ‘token’ to the panel;

‘ I think it’s also being able to provide some perspective, some general perspective. I’m quite a generalist actually, I’m not a specialist……So I’m very generalist. And I think they’re also well aware of the ethnic and gender composition of that and lots of reasons why I’m asked on panels. (Panel 1, Outputs and Impact, Female)

Women perceived their value on the panel as supportive, as someone who is prepared to work on the team, and listen to other views towards as a generalist, and constructionist, rather than as an enforced of dogmatic views and raw, hard notions of Impact that were represented through quantitative indicators only. As such, how the panel operated reflects general studies of how work can be organised along gender lines, as well as specific to workload and power in the academy. The similarity between the gendered associations towards conceptualising Impact from the researchers and evaluators, combined with how the panel organises its work along gendered lines, suggests how panel culture echoes the implicit tendencies within the wider research community. The implications of this tendency in relation to the evaluation of non-academic Impact is discussed below.

Discussion: an Impact a-gender?

This study shows how researchers and evaluators in two, independent data sets echoed a gendered orientation towards Impact, and how this implies an Impact a-gender. That gendered notions of Impact emerged as a significant theme from two independent data sets speaks to the importance of the issue. It also illustrates the need for policymakers and funding organisations to acknowledge its potential effects as part of their efforts towards embedding a more inclusive research culture around the generation and evaluation of research impact beyond academia.

Specifically, this paper has identified gendered language around the generation of, and evaluation of Impact by researchers in Australia and the UK, as well as by evaluators by the UK’s most recent Research Excellence Framework in 2014. For the UK and Australia, the prominence of Impact, as well as the policy borrowing between each country (Chubb, 2017 ) means that a reliable comparison of pre-evaluation perceptions of researchers and evaluators can be made. In both data sets presumptions of Impact as either ‘soft’ or ‘hard’ by both researchers and evaluators were found to be gendered. Whereas it is not surprising that panel culture reflects the dominant trends within the wider academic culture, this paper raises the question of how the implicit operation of gender bias surrounding notions of scientific productivity and its measurement, invade and therefore unduly influence the evaluation of those notions during peer-review processes. This negates the motivation behind a broad Impact definition and evaluation as inclusive since unconscious bias towards women can still operate if left unchecked and unmanaged.

Gendered notions of excellence were also related to the ability to be ‘competitive’, and that once Impact became a formalised, countable and therefore competitive criterion, it also become masculine where previously it existed as a feminised concept related to female academic-ness. As a feminised concept, Impact once referred to notions of excellence requiring communication such as public engagement, or stakeholder coordination—the ‘softer’ impacts. However, this association only remains ‘soft’ insofar as Impact remains unmeasurable, or more nuanced in definition. This is especially pertinent for the evaluation of societal impact where already conceived ideas of engagement and ‘ women’s work ’ influence how evaluators assess the feasibility of impact narratives for the purposes of its assessment. This paper also raises the question that notions of gender in relation to Impact persist irrespective of the identities assumed for the purposes of its evaluation (i.e., as a peer reviewer). This is not to say that academic culture in the UK and Australia, where Impact is increasingly being formalised into rewards systems, is not changing. More that there is a tendency in some evaluations for the burden of evidence to be applied differently to genders due to tensions surrounding what women are ‘good’ at doing: engagement, versus what ‘men’ are good at doing regarding Impact. In this scenario, quantitative indicators of big, high-level impacts are to be attributable to male traits, rather than female. This has already been noted in student evaluations of teaching (Kogan et al., 2010 ) and of academic leadership performance where the focus on the evaluation is on how others interpret performance based on already held gendered views about competence based on behaviours (Williams et al., 2014 ; Holt and Ellis, 1998 ). As such, when researchers transcend these gendered identities that are specific to societal impact, there is a danger of an Impact-a-gender bias arising in the assessment and forecasting of Impact. This paper extends this understanding and outlines how this may also be the case for assessments of societal impact.

By examining perceptions, as well as using an inductive analysis, this study was able to unearth unconsciously employed gendered notions that would not have been prominent or possible to pick up if we asked the interviewees about gender directly. This was particularly the case for the re-analysis of the post-evaluation interviews. However, future studies might consider incorporating a disciplinary-specific perspective as although the evaluators were from the medical/biomedical disciplines, researchers were from a range of disciplines. This would identify any discipline-specific risk towards an Impact a-gender. Nonetheless, further work that characterises the impact a-gender, as well as explores its wider implications for gender inequities within HE is currently underway.

How research evidence is labelled as excellent and therefore trustworthy, is heavily dictated by an evaluation process that is perceived as impartial and fair. However, if evaluations are compounded by gender bias, this confounds assessments of excellence with gendered expectation of non-academic impact. Consequently, gendered expectations of excellence for non-academic impact has the potential to: unconsciously dissuade women from pursuing more masculinised types of impact; act as a barrier to how female researchers mobilise their research evidence; as well as limit the recognition female researchers gain as excellent and therefore trustworthy sources of evidence.

The aim of this paper was not to criticise the panellists and researchers for expressing gendered perspectives, nor to present evidence about how researchers are unduly influenced by gender bias. The results shown do not support either of these views. However, the aim of this paper was to acknowledge how gender bias in research Impact generation can lead to a panel culture dominated by academics that translate the implicit and explicit biases within academia that influence its evaluation. This paper raises an important question regarding what we term the ‘Impact a-gender’, which outlines a mechanism in which gender bias feeds into the generation and evaluation of a research criterion, which is not traditionally associated with a hard, metrics-masculinised output from research. Along with other techniques used to combat unconscious bias in research evaluation, simply by identifying, and naming the issue, this paper intends to combat its ill effects through a community-wide discussions as a mechanism for developing tools to mitigate its wider effect if left unchecked or merely accepted as ‘acceptable’. In addition, it is suggested that government and funding organisations explicitly refer to the impact a-gender as part of their wider EDI (Equity, Diversity and Inclusion) agendas towards minimising the influence of unconscious bias in research impact and evaluation.

Data availability

Data is available upon request subject to ethical considerations such as consent so as not to compromise the individual privacy of our participants.

Change history

19 may 2020.

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

For the purposes of this paper, when the text refers to non-academic, societal impact, or the term ‘Impact’ we are referring to the change and effect as defined by REF2014/2021 and the larger conceptualisation of impact that is generated through knowledge exchange and engagement. In this way, the paper refers to a broad conceptualisation of research impact that occurs beyond academia. This allows a distinction between Impact as central to this article’s contribution, as opposed to academic impact, and general word ‘impact’.

Impact scholars or those who are ‘good at impact’ are often equated with applied researchers.

One might interpret this as meaning ‘economic impact’.

This is described in the next section as ‘women’s work’ by one evaluator.

Ahmed S (2006) Doing diversity work in higher education in Australia. Educ Philos Theory 38(6):745–768

Article Google Scholar

Amâncio L (2005) Reflections on science as a gendered endeavour: changes and continuities. Soc Sci Inf 44(1):65–83

Andrews E, Weaver A, Hanley D, Shamatha J, Melton G (2005) Scientists and public outreach: participation, motivations, and impediments. J Geosci Educ 53(3):281–293

Astin HS (1978) Factors affecting women’ scholarly productivity. In: Astin AS, Hirsch WZ (eds) The higher education of women: essays in honor of Rosemary Park. Praeger, New York, pp. 133–157

Google Scholar

Baker M (2008) Ambition, confidence and entrepreneurial skills: gendered patterns in academia. Australian Sociological Association Annual Meeting, Melbourne. Retrieved from https://www.tasa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Baker-Maureen-Session-46-PDF1.Pdf

Bank BJ (2011) Gender and higher education. JHU Press

Becher T (1989) Academic tribes and territories. Open University Press/Society for Research into Higher Education, Buckingham

Becher T (1994) The significance of disciplinary differences. Stud High Educ 19(2):151–162

Bellas ML (1999) Emotional labor in academia: the case of professors. Ann Am Acad Political Soc Sci 561(1):96–110

Biglan A (1973a) The characteristics of subject matter in different academic areas. J Appl Psychol 57:195–203

Biglan A (1973b) Relationships between subject matter characteristics and the structure and output of university departments. J Appl Psychol 57(3):204

Bird S, Litt J, Wang Y (2004) Creating status of women reports: Institutional housekeeping as “Women’s Work”. NWSA J 194–206

Blackmore J (2002) Globalisation and the restructuring of higher education for new knowledge economies: New dangers or old habits troubling gender equity work in universities? High Educ Q 56(4):419–441

Brink MvD, Benschop Y (2012) Gender practices in the construction of academic excellence: Sheep with five legs. Organization 19(4):507–524

Burkinshaw P (2015) Higher education, leadership and women vice chancellors: fitting in to communities of practice of masculinities. Springer

Caplan N (1979) The two-communities theory and knowledge utilization. Am Behav Sci 22(3):459–470

Carey G, Dickinson H, Cox EM (2018) Feminism, gender and power relations in policy–Starting a new conversation. Aust J Public Adm 77(4):519–524

Carnes M, Bartels CM, Kaatz A, Kolehmainen C (2015) Why is John more likely to become department chair than Jennifer? Trans Am Clin Climatological Assoc 126:197

Cassell J (2002) Perturbing the system: “hard science,” “soft science,” and social science, the anxiety and madness of method Hum Organ 61(2):177–185. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/44127444

Chubb JA (2017) Instrumentalism and epistemic responsibility: researchers and the impact agenda in the UK and Australia (Doctoral dissertation, University of York)

Clegg S (2008) Academic identities under threat? Br Educ Res J 34(3):329–345

Davies J, Syed J, Yarrow E (2017) The research impact agenda and gender. In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2017, No. 1, p. 15298). Academy of Management, Briarcliff Manor, NY

Davies J, Yarrow E, Syed J (2020) The curious under-representation of women impact case leaders: Can we disengender inequality regimes? Gend Work Organ 27(2):129–148

Deem R (1998) New managerialism’ and higher education: the management of performances and cultures in universities in the United Kingdom. Int Stud Sociol Educ 8(1):47–70

Derrick GE (2018) The Evaluators’ Eye: Impact assessment and academic peer review. Palgrave Macmillan, London, UK

Book Google Scholar

Ellemers N, van den Heuvel H, de Gilder D, Maass A, Bonvini A (2004) The underrepresentation of women in science: differential commitment or the queen bee syndrome? Br J Soc Psychol 43(Pt 3):315–338

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Geertz C (1983) Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology, Basic Books, New York

Gibbons M (1999) Science’s new social contract with society. Nature 402(6761 Suppl):C81–C84

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Gromkowska-Melosik A (2014) The masculinization of identity among successful career women? A case study of Polish female managers. J Gend Power 1(1) http://hdl.handle.net/10593/11289

Grummell B, Devine D, Lynch K (2009) The care-less manager: gender, care and new managerialism in higher education. Gend Educ 21(2):191–208

Hazelkorn E, Gibson A (2019) Public goods and public policy: What is public good, and who and what decides? High Educ 78(2):257–271

Heaton J (1998) Secondary analysis of qualitative data. Soc Res Update 22(4):88–93

Heilman ME (1995) Sex stereotypes and their effects in the workplace: What we know and what we don't know. J Soc Behav Pers 10(4):3

ADS Google Scholar

Holt C, Ellis J (1998) Assessing the current validity of the Bem Sex-Role Inventory. Sex Roles 39 929941:11–12

Johnson D, Ecklund E, Lincoln A (2014) Narratives of science outreach in elite contexts of academic science. Sci Commun 36:81–105

Jong S, Smit J, Drooge LV (2015) Scientists’ response to societal impact policies: a policy paradox. Sci Public Policy 43(1):102–114

Keller JF, Eakes E, Hinkle D, Hughston GA (1978) Sexual behavior and guilt among women: a cross-generational comparison. J Sex Marital Ther 4(4):259–265

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kogan L, Schoenfeld-Tacher R, Hellyer P (2010) Student evaluations of teaching: perceptions of faculty based on gender, position, and rank. Teach High Educ 15(6):623–636

Kretschmer H, Kretschmer T (2013) Gender bias and explanation models for the phenomenon of women’s discriminations in research careers. Scientometrics 97(1):25–36

Kuhn TS (1962) The structure of scientific revolutions: University of Chicago press

Langfeldt L (2006) The policy challenges of peer review: Managing bias, conflict of interests and interdisciplinary assessments. Res Evaluation 15(1):31–41

Larivière V, Ni C, Gingras Y, Cronin B, Sugimoto CR (2013) Bibliometrics: global gender disparities in science. Nature 504(7479):211–213

Leathwood C, Read B (2008) Gender and the changing face of higher education: a feminized future? McGraw-Hill Education, UK

Lee JH, Noh G (2013) Polydesensitisation with reducing elevated serum total IgE by IFN-gamma therapy in atopic dermatitis: IFN-gamma and polydesensitisation (PDS). Cytokine 64(1):395–403

Lorber M (2005) Endocarditis from Staphylococcus aureus . JAMA 294(23):2972

Lorenz C (2012) If you’re so smart, why are you under surveillance?: universities, neoliberalism and new public management’. Crit Inquiry 38(3):599–629

Lundine J, Bourgeault IL, Clark J, Heidari S, Balabanova D (2019) Gender bias in academia. Lancet (Lond, Engl) 393(10173):741–743

Merton R (1942) On science and democracy. J Legal Polit Sociol 1942(1):115–126

Morley L (2003) Quality and power in higher education. McGraw-Hill Education, UK

Nature (2019) A kinder research culture is possible. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-02951-4

Pantin CFA (1968) The relations between the sciences. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Paulus JK, Switkowski KM, Allison GM, Connors M, Buchsbaum RJ, Freund KM, Blazey-Martin D (2016) Where is the leak in the pipeline? Investigating gender differences in academic promotion at an academic medical centre. Perspect Med Educ 5(2):125–128

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Poggio B (2006) Outline of a theory of gender practices. Gend Work Organ 13(3):225–233

Rausch DK (1989) The academic revolving door: why do women get caught? CUPA J 40(1):1–16

Reay D (n.d.) Cultural capitalists and academic habitus: classed and gendered labour in UK higher education. In Womens studies international forum (Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 31–39) Pergamon

Rossiter MW (1993) The Matthew Matilda effect in science. Soc Stud Sci 23(2):325–341

Santos G, Phu S (2019) Dang van gender and academic rank in the UK. Sustainability 3171, 11(11):1–46

Sax LJ, Hagedorn LS, Arredondo M, DiCrisi FA (2002) Faculty research productivity: Exploring the role of gender and family-related factors. Res Higher Educ 43(4):423–446

Schatteman A (2014) Academics meets action: Community engagement motivations, benefits, and constraints. J Community Engagem High Educ 6(1):17–30

Schommer-Aikins M, Duell O, Barker S (2003) Epistemological beliefs across domains using Biglan’s classification of academic disciplines. Res High Educ 44(3):347–366

Severin A, Martins J, Delavy F, Jorstad A, Egger M, Heyard R (2019) Gender and other potential biases in peer review: Analysis of 38,250 external peer review reports. Peer J Preprints 7:e27587v3

Simpson A (2017) The surprising persistence of Biglan’s classification scheme. Stud High Educ 42(8):1520–1531

Smart J, Feldman K, Ethington C, Nashville T (2000) Academic disciplines: Holland’s theory and the study of college students and faculty, 1st edn. Vanderbilt University Press

Snow CP (2012) The two cultures. Cambridge University Press

Stern N (2016) Research Excellence Framework review: building on success and learning from experience. Gov. UK

Storer NW (1967) The hard sciences and the soft: Some sociological observations. Bull Med Libr Assoc 55(1):75–84

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sugimoto CR, Ni C, West JD, Larivière V (2015) The academic advantage: gender disparities in patenting. PLoS ONE 10(5):e0128000

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Thelwall M, Bailey C, Tobin C, Bradshaw N (2019) Gender differences in research areas, methods and topics: Can people and thing orientations explain the results? J Informetr 13(1):149–169

Trowler PR (2001) Academic tribes and territories. McGraw-Hill Education, UK

Upton S, Vallance P, Goddard J (2014) From outcomes to process: evidence for a new approach to research impact assessment. Res Evaluation 2014 23(4):352–365

UKRI (2019) Excellence with Impact. Retrieved from https://www.ukri.org/innovation/excellence-with-impact/

UKRI (2020) Pathways to impact: impact core to the UK Research and Innovation application process. Retrieved from https://www.ukri.org/news/pathways-to-impact-impact-core-to-the-uk-research-and-innovation-application-process/

Von Roten F (2011) Crettaz gender differences in scientists’ public outreach and engagement activities. Sci Commun 33(1):52–75

Ward KB, Grant L (1996) Gender and academic publishing. (Vol. 11, pp. 172–212) Higher Education-New York-Agathon Press Incorporated

Weinstein N, Wilsdon J, Chubb J, Haddock G (2019) The Real Time REF Review: A Pilot Study to Examine the Feasibility of a Longitudinal Evaluation of Perceptions and Attitudes Towards REF 2021. Retrieved from https://re.ukri.org/news-events-publications/publications/real-time-ref-review-pilot-study/

Weed M (2005) “Meta Interpretation”: A Method for the Interpretive Synthesis of Qualitative Research. In Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research (Vol. 6, No. 1)

Wheatle K, BrckaLorenz A (2015) Civic engagement, service-learning, and faculty engagement: a profile of Black women faculty. American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting

Williams BAO (2002) Truth & truthfulness: An essay in genealogy. Princeton University Press

Williams J, Dempsey R, Slaughter A (2014) What works for women at work: four patterns working women need to know. New York University Press, New York

Yarrow E, Davies J (2018) The gendered impact agenda-how might more female academics’ research be submitted as REF impact case studies? Impact of Social Sciences Blog

Zinken J, Hellsten I, Nerlich B (2008) Discourse metaphors. Body, Lang Mind 2:363–385

Download references

Acknowledgements