5 Easy Steps for Teaching When Questions for Speech Therapy

- October 19, 2022

- Speech Therapy Planning , Teaching Speech Therapy Skills , Therapy Materials , Uncategorized , WH Questions

Sharing is caring!

Teaching when questions for speech therapy intervention can be a challenge, especially when there is never enough time in your day to plan effective therapy. I’m here to simplify your therapy by giving you an easy-to-follow plan when it comes to teaching when questions.

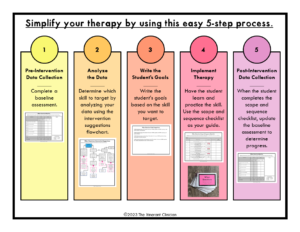

After reading this post, you will have a structured speech therapy intervention plan for teaching when questions that you can implement tomorrow. Here is an overview of the 5 steps that will make you the expert at your school when it comes to writing and addressing those when question IEP goals.

- Step 1: Start with pre-intervention data collection for when questions.

- Step 2: Analyze the data from Step 1 to determine where to start your intervention.

- Step 3: Using the information from Step 2, write your student’s speech therapy goals.

- Step 4: Implement therapy.

- Step 5: Complete your post-intervention data collection.

Note: This easy 5-step process is included in my When Questions Flashcards resource. If you would like to skip the rest of this article and jump right into your intervention, click the picture below.

Step 1. Start with pre-intervention data collection for when questions.

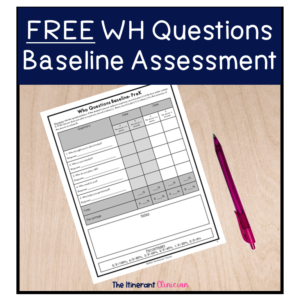

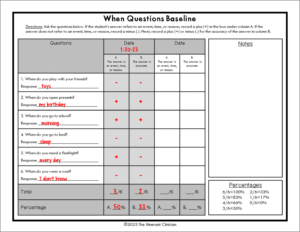

Determining IEP goals and planning speech therapy intervention depends upon knowing how the student is currently performing with a specific skill. Using an informal WH question test for data collection in speech therapy is a must.

If you don’t have a data collection tool for WH or WHEN questions, don’t worry. Download my FREE WH Questions Baseline Assessment today!

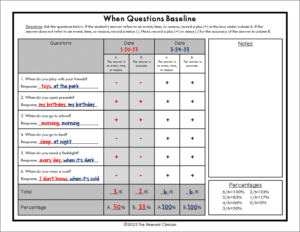

Here is a completed when questions baseline from my wh questions for speech therapy resource.

Step 2. Analyze the data from Step 1 to determine where to start your intervention.

Knowing where to start when questions speech therapy intervention can sometimes be tricky. After completing the baseline assessment from step 1, use this free flow chart to help you analyze your data. This will help you determine your therapy plan.

If you would like a free copy of this flow chart, click on the picture above and print.

There are four columns on the flow chart. Here is what each column means.

- Left Column: Focus on teaching prelinguistic skills and building receptive language.

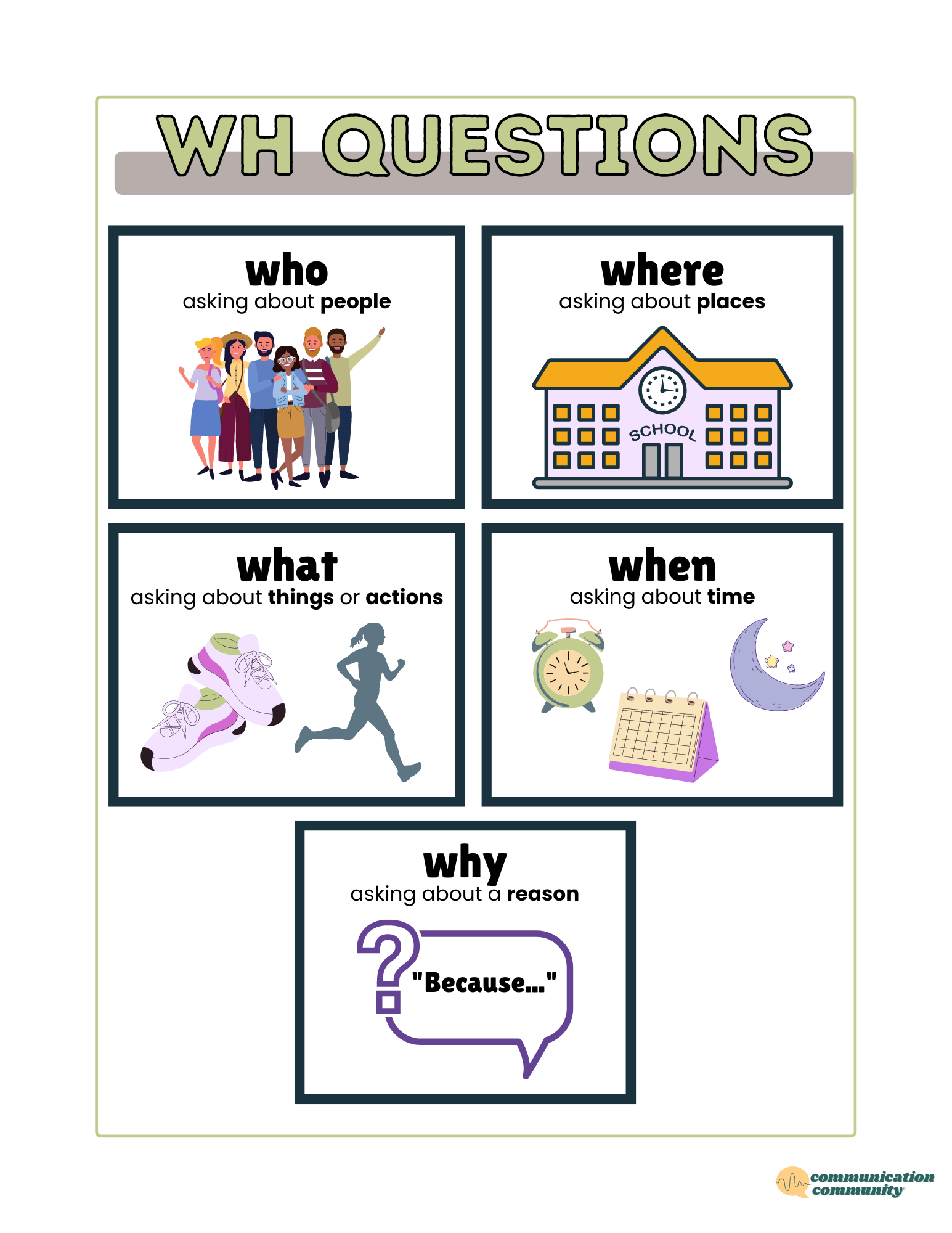

- Left Middle Column: Work on teaching early developing WH questions- who, what, where.

- Right Middle Column: Work on teaching when questions.

- Right Column: Work on increasing vocabulary. Making IEP accommodations might also be appropriate.

Step 3. Write your student’s speech therapy goals based on the information from step 2.

First, keep in mind normal when question development..

For planning when question speech therapy goals, it is important to keep in mind normal when question development. Here are the norms that I use from the resource Guide to Communication Milestones (Lanza, J. R. & Flahive, L. K., 2012).

WHEN Question Development

- Answers WHEN questions: 4 years of age.

Keep in mind that this norm is most likely referring to simple when questions that don’t require a great deal of background knowledge.

Then, determine a starting point for speech therapy intervention.

Using the flow chart from step 2, while keeping in mind normal when question development, determine your IEP goals.

1. Left Column: Focus on prelinguistic goals and receptive language goals. If your student is on this side of the flow chart, you should not introduce when questions.

Prelinguistic Goal for Joint Attention : The student will demonstrate joint attention in 8/10 trials when the adult points to/shows an object or talks about an immediate event (something that is happening in the child’s present environment).

Click here for more information on joint attention .

Prelinguistic Goal for Attending : The student will attend to a reading and/or play activity for ___ minutes with minimal adult support in 4/5 trials.

Receptive Language Goal for WH Questions (Play Based) : The student will respond to WHO, WHAT, and/or WHERE questions during a play activity in 8/10 trials by pointing.

Early Developing WH Questions Goal (Skill Based) : The student will answer basic WHO, WHAT, and/or WHERE questions by pointing to or stating the answer with 80% accuracy. (i.e., Where is your nose? What is this?)

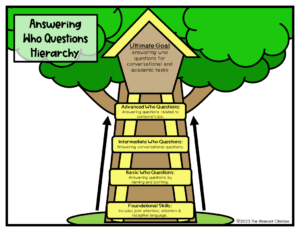

2. Left Middle Column: Focus on teaching early developing wh questions- who, what, where. After these questions are mastered, move on to when questions.

WHO Questions Speech Therapy Goal : The student will answer WHO questions with 80% accuracy when picture choices are presented.

WHO Questions Speech Therapy Goal: The student will answer WHO questions with 80% accuracy. (no picture choices)

WHAT Questions Speech Therapy Goal : The student will answer WHAT questions with 80% accuracy when picture choices are presented.

WHAT Questions Speech Therapy Goal : The student will answer WHAT questions with 80% accuracy. (no picture choices)

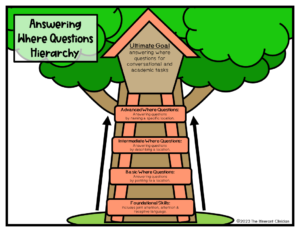

WHERE Questions Speech Therapy Goal : The student will answer WHERE questions with 80% accuracy when picture choices are presented.

WHERE Questions Speech Therapy Goal : The student will answer WHERE questions with 80% accuracy. (no picture choices)

3. Right Middle Column: Focus on teaching when questions.

Although you can get very detailed with your IEP goals, I recommend keeping things simple. It’s important that other team members understand the student’s goals. Here are two simple when questions example goals.

WHEN Questions Goal : The student will answer WHEN questions with 80% accuracy when picture choices are presented.

WHEN Questions Goal : The student will answer WHEN questions with 80% accuracy. (no picture choices)

If your student is working on generalizing when questions to conversational and reading comprehension tasks, these are some suggestions.

WHEN Questions Conversational Speech Therapy Goal : The student will answer WHEN questions during conversation with 80% accuracy.

WHEN Questions Reading Comprehension Speech Therapy Goal : The student will answer WHEN questions for reading comprehension tasks with 80% accuracy.

4. Right Column: Increasing vocabulary to support answering when questions might be the best course of treatment. Considering IEP accommodations for addressing language complexity might also be appropriate.

You might find that it is more appropriate to focus on accommodations and modifications to decrease the barriers that might exist when answering questions. Here is a list of possible accommodations and modifications.

- Simplify questions by decreasing the amount of complex language used in the question.

- Supplement your verbal question with a picture scene or picture cue.

- Give the student visual or verbal choices of answers.

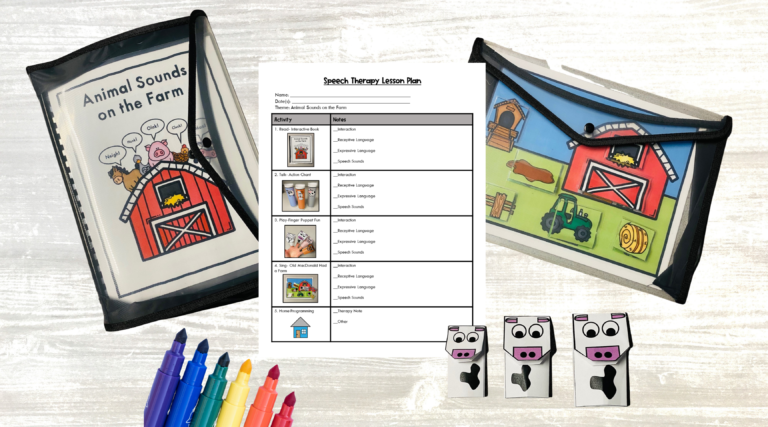

Step 4. Implement therapy.

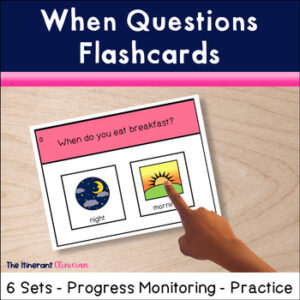

Now that you have your student’s IEP goals written, it’s time to get your speech therapy intervention tools ready. You might already have a resource that works well for addressing when question goals. However, if you are looking for a more comprehensive resource for teaching when questions, I have created a set of when questions flashcards that you can purchase. The flashcards featured in this section are from that resource.

First, teach the skill.

Explicit instruction.

Consider starting with explicit instruction when teaching a student to answer when questions. This is how I begin each session. There is research in the area of grammar intervention that suggests combining explicit instruction with implicit instruction is more efficient than just implicit instruction alone. (Calder, S.D., Claessen, M., Ebbels, S. & Leitao, S., 2020)

Directly teach your students that when they hear the word when in a question it refers to an event, time, or reason for doing something.

Then, practice the skill.

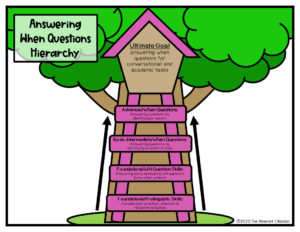

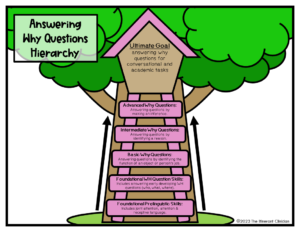

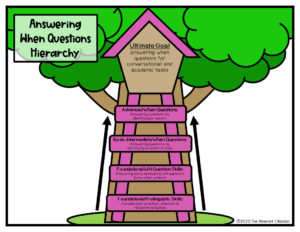

There isn’t much research that I’ve come across in regards to a hierarchy for how to teach when questions. The following is based on my clinical experience and what I’ve found to be effective in teaching when questions for speech therapy intervention. Although this learning ladder provides a general hierarchy, you should always consider the student’s language profile when planning intervention.

Note: I only practice when questions with elementary-age students (5K+). When questions require higher level language skills to answer because the questions/answers require more abstract thinking than early developing WH questions (who, what, where). Instead of focusing on concrete objects or people, as we do with early developing WH questions, many when questions/answers are based upon the understanding of cultural norms, time, or the reasons we demonstrate certain behaviors.

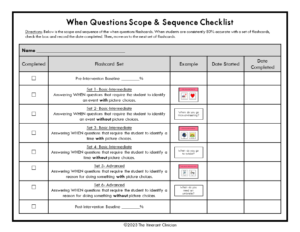

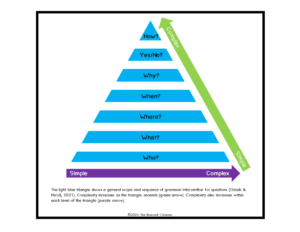

Here is the scope and sequence of my when questions flashcard resource.

If the student is old enough, I use flashcards between turns of an open-ended game. The game motivates students to participate in a flashcard activity that would otherwise be a nonpreferred task.

1. Basic-Intermediate When Questions

If your student does not need to work on foundational WH question skills, start with basic-intermediate when questions. (These WH question examples are from sets 1-4 of my when questions flashcards resource .) If your student can already answer intermediate when questions, move on to advanced when questions.

For the basic-intermediate level of when questions, I decided to start with when questions that refer to events. I then proceeded to when questions that focus on time. In reality, there isn’t that much of a divide in complexity between the two types of when questions. You might find that sets 3 and 4 are easier for some students than sets 1 and 2.

Examples : When do you open presents? When is your birthday?

Prerequisite Skills : The student needs to understand cultural norms and time.

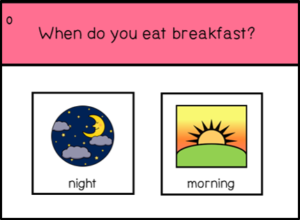

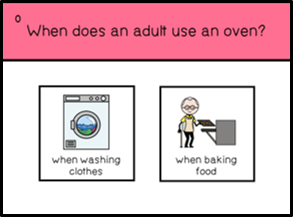

First, I start by using flashcards with picture choices. Before moving on to the next set of cards, I might use these cards again but not show the picture choices. If the student has difficulty answering the question, I show the picture choices.

Although the research is mixed on the efficacy of using picture choices to teach questions, I find that pictures minimize frustration with teaching when questions. It is a perfect strategy for students who need to take baby steps when learning a new skill.

Then, I move on to flashcards without picture choices.

2. Advanced When Questions

Next, address when questions that require the student to state a reason. (This WH question example is from sets 5-6 of the when questions flashcards resource .)

Example : When do you go to the doctor?

Prerequisite Skills : The student needs to understand the reason we demonstrate certain behaviors.

Step 5. Complete your post-intervention data collection.

When your session data suggests that the student has learned how to answer when questions, update the original baseline assessment. This provides you with data to report at the IEP meeting and/or on the progress report. If the student has met his or her goal, move on to the next skill.

What is the ultimate goal for working on when questions?

It is important to note that during this process of teaching when questions for speech therapy, it’s essential to incorporate when questions into conversational and read-aloud activities. This is the overarching goal of working on questions- to be able to participate in a conversation and answer questions for academic tasks.

If you are unsure of what your student’s accuracy is with answering WH and WHEN questions, get a free baseline tool . This will help you determine where you should start with intervention.

Wondering where you can get the WH question examples featured in this post? Get your own set of when question flashcards to complement your therapy at my Teachers Pay Teachers store.

Other Related Posts:

4 Things To Consider Before Writing Speech Therapy WH Question Goals

5 Steps for Effectively Teaching Who Questions for Speech Therapy

5 Steps for Effectively Teaching What Questions in Speech Therapy

5 Simple Steps for Teaching Where Questions for Speech Therapy

Calder, S.D., Claessen, M., Ebbels, S., & Leitão, S. (2020). Explicit grammar intervention in young school-aged children with developmental language disorder: An efficacy study using single-case experimental design. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools . https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_LSHSS-19-00060

Calder, S. D., Claessen, M., Ebbels, S., & Leitão, S. (2020). The efficacy of an explicit intervention approach to improve past tense marking for early school-age children with developmental language disorder. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_JSLHR-20-00132

Ebbels, S., & Owen Van Horne, A. (2020). Grammatical concepts of English: Suggested order of intervention. The Informed SLP . https://www.theinformedslp.com/review/the-grammar-guide-you-never-knew-you-always-wanted

Gaertner et al., (2008) Focused Attention in Toddlers: Measurement, Stability, and Relations to Negative Emotion and Parenting. Journal of Infant Child Development . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2607062/pdf/nihms-81608.pdf

Lanza, J. R. & Flahive, L. K. (2012) Guide to Communication Milestones. LinguiSystems. ( https://www.carolinatherapeutics.com/wp-content/uploads/milestones-guide.pdf )

2 Responses

Thanks for reading!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

More blog posts...

How to Teach Why Questions for Speech Therapy: 5 Essential Steps

Teaching why questions for speech therapy intervention can be a challenge, especially when there is never enough time

Enhancing Communication Skills through Joint Attention in Speech Therapy

Enhancing communication skills through joint attention in speech therapy is often the primary goal for young students. For

Teaching who questions for speech therapy intervention can be a challenge, especially when there is never enough time

4 Things To Consider Before Writing Speech Therapy WH Questions Goals

In speech therapy, WH questions can be a challenge for many special education students. Before writing speech therapy

Teaching when questions for speech therapy intervention can be a challenge, especially when there is never enough time

Teaching where questions for speech therapy intervention can be a challenge, especially when there is never enough time

Hi, I'm Catherine!

I provide itinerant speech-language pathologists with valuable content and travel friendly resources. I specialize in providing lessons and activities for preschool students with language and articulation disabilities, but I also have resources for older students.

I live and work as an itinerant speech-language clinician in Wisconsin. In my spare time, I enjoy traveling with my husband and son.

I’m so grateful that you’ve found my online home. I can’t wait to help you!

Get your free preschool speech therapy lesson plan here!

Copyright 2021 | The Itinerant Clinician | All Rights Reserved

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

Get our FREE Mother's Day Printable 💐!

50+ Higher-Order Thinking Questions To Challenge Your Students

50+ lower order thinking questions too!

Want to help your students make strong connections with the material? Ensure you’re using all six levels of cognitive thinking. This means asking lower-order thinking questions as well as higher-order thinking questions. Learn more about each here, and find plenty of examples for each.

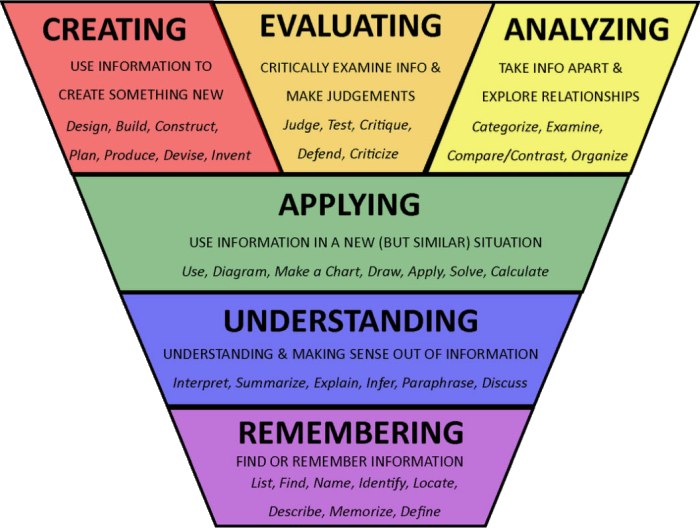

What are lower-order and higher-order thinking questions?

Source: University of Michigan

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a way of classifying cognitive thinking skills. The six main categories—remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, create—are broken into lower-order thinking skills (LOTS) and higher-order thinking skills (HOTS). LOTS includes remember, understand, and apply. HOTS covers analyze, evaluate, and create.

While both LOTS and HOTS have value, higher-order thinking questions urge students to develop deeper connections with information. They also encourage kids to think critically and develop problem-solving skills. That’s why teachers like to emphasize them in the classroom.

New to higher-order thinking? Learn all about it here. Then use these lower- and higher-order thinking questions to inspire your students to examine subject material on a variety of levels.

Remember (LOTS)

- Who are the main characters?

- When did the event take place?

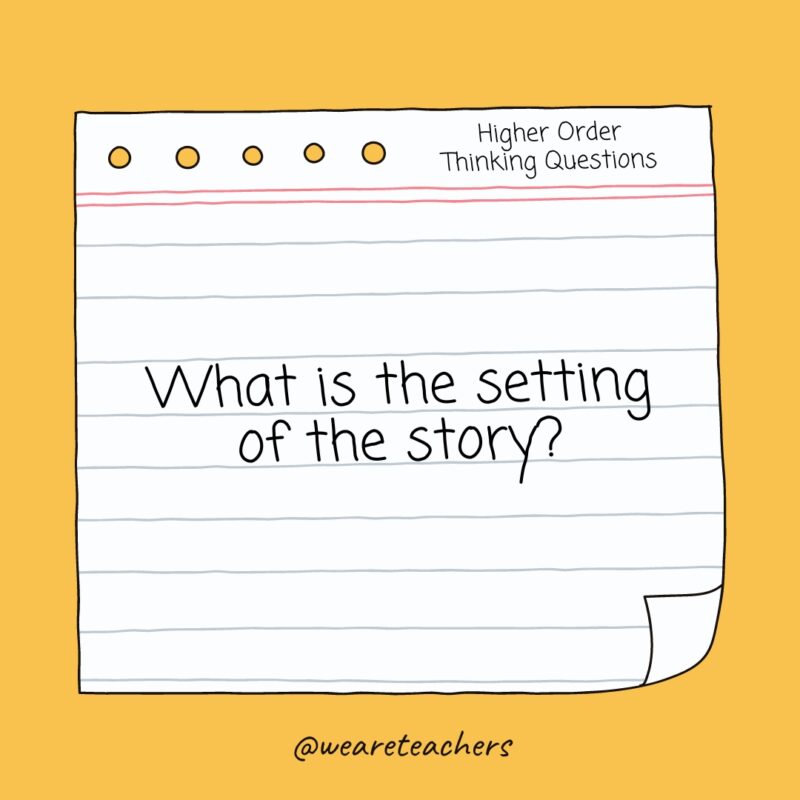

- What is the setting of the story?

- Where would you find _________?

- How do you __________?

- What is __________?

- How do you define _________?

- How do you spell ________?

- What are the characteristics of _______?

- List the _________ in proper order.

- Name all the ____________.

- Describe the __________.

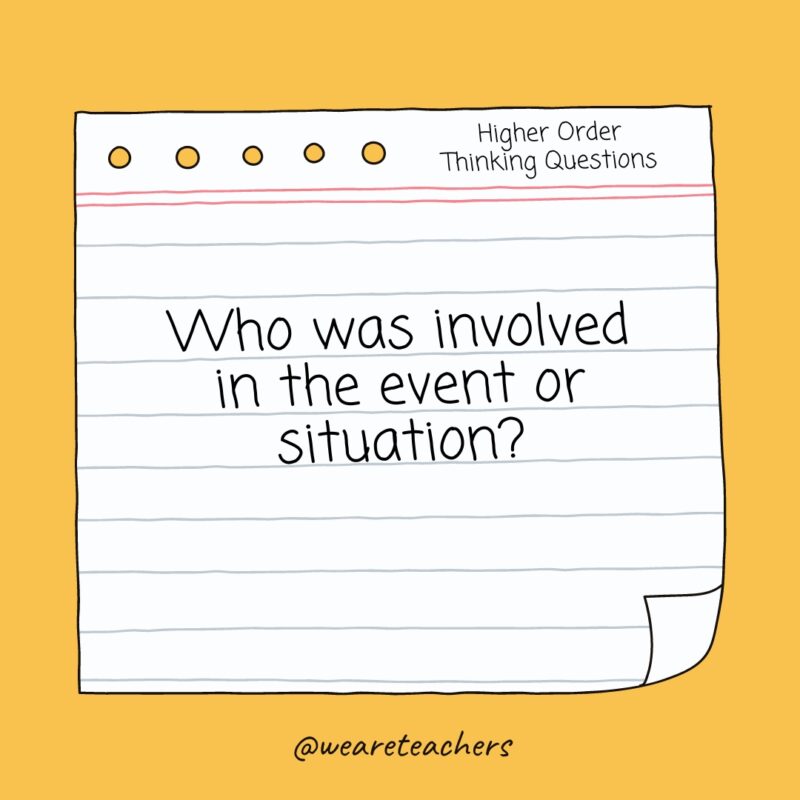

- Who was involved in the event or situation?

- How many _________ are there?

- What happened first? Next? Last?

Understand (LOTS)

- Can you explain why ___________?

- What is the difference between _________ and __________?

- How would you rephrase __________?

- What is the main idea?

- Why did the character/person ____________?

- What’s happening in this illustration?

- Retell the story in your own words.

- Describe an event from start to finish.

- What is the climax of the story?

- Who are the protagonists and antagonists?

- What does ___________ mean?

- What is the relationship between __________ and ___________?

- Provide more information about ____________.

- Why does __________ equal ___________?

- Explain why _________ causes __________.

Apply (LOTS)

- How do you solve ___________?

- What method can you use to __________?

- What methods or approaches won’t work?

- Provide examples of _____________.

- How can you demonstrate your ability to __________.

- How would you use ___________?

- Use what you know to __________.

- How many ways are there to solve this problem?

- What can you learn from ___________?

- How can you use ________ in daily life?

- Provide facts to prove that __________.

- Organize the information to show __________.

- How would this person/character react if ________?

- Predict what would happen if __________.

- How would you find out _________?

Analyze (HOTS)

- What facts does the author offer to support their opinion?

- What are some problems with the author’s point of view?

- Compare and contrast two main characters or points of view.

- Discuss the pros and cons of _________.

- How would you classify or sort ___________?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of _______?

- How is _______ connected to __________?

- What caused __________?

- What are the effects of ___________?

- How would you prioritize these facts or tasks?

- How do you explain _______?

- Using the information in a chart/graph, what conclusions can you draw?

- What does the data show or fail to show?

- What was a character’s motivation for a specific action?

- What is the theme of _________?

- Why do you think _______?

- What is the purpose of _________?

- What was the turning point?

Evaluate (HOTS)

- Is _________ better or worse than _________?

- What are the best parts of __________?

- How will you know if __________ is successful?

- Are the stated facts proven by evidence?

- Is the source reliable?

- What makes a point of view valid?

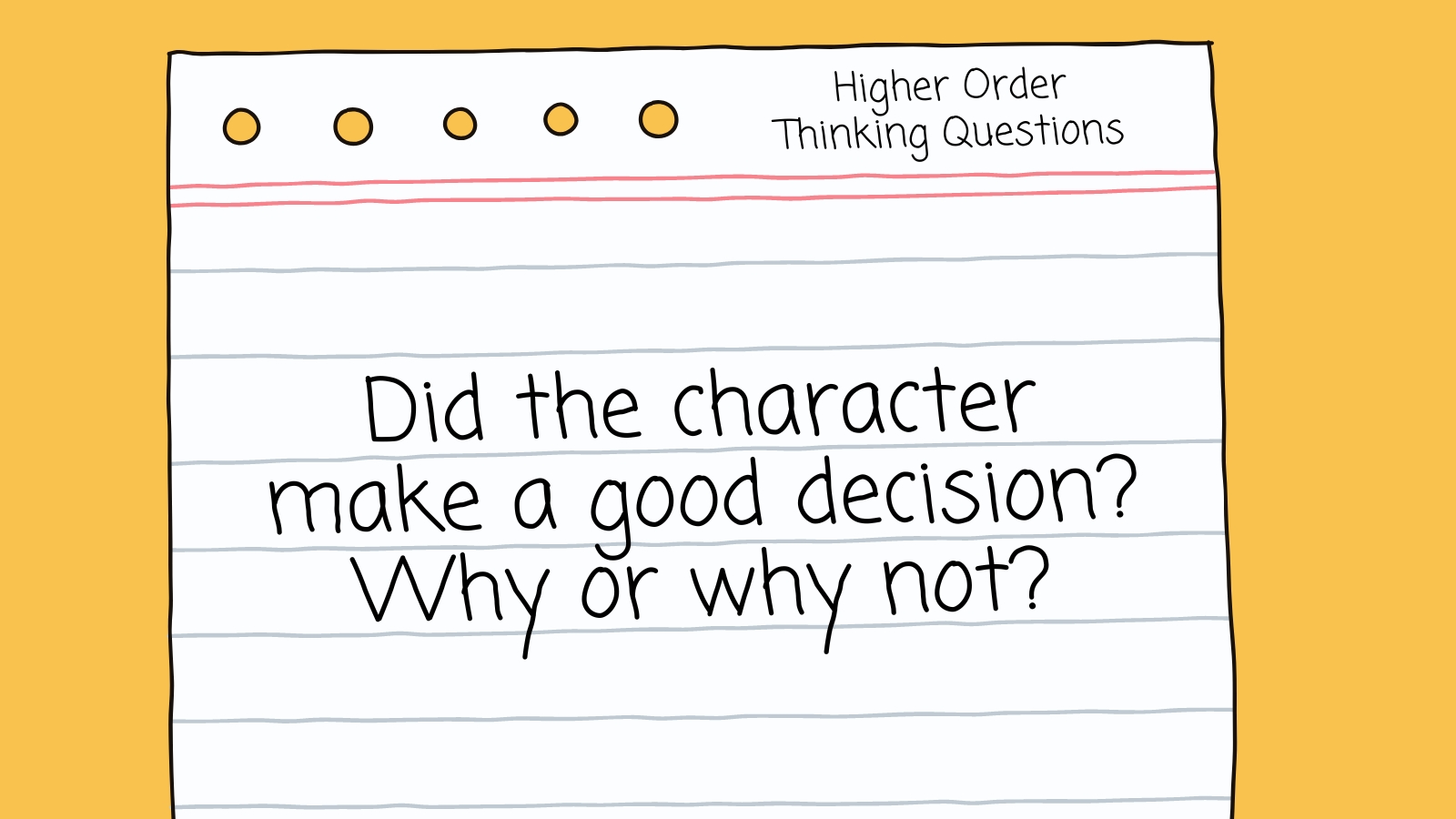

- Did the character/person make a good decision? Why or why not?

- Which _______ is the best, and why?

- What are the biases or assumptions in an argument?

- What is the value of _________?

- Is _________ morally or ethically acceptable?

- Does __________ apply to all people equally?

- How can you disprove __________?

- Does __________ meet the specified criteria?

- What could be improved about _________?

- Do you agree with ___________?

- Does the conclusion include all pertinent data?

- Does ________ really mean ___________?

Create (HOTS)

- How can you verify ____________?

- Design an experiment to __________.

- Defend your opinion on ___________.

- How can you solve this problem?

- Rewrite a story with a better ending.

- How can you persuade someone to __________?

- Make a plan to complete a task or project.

- How would you improve __________?

- What changes would you make to ___________ and why?

- How would you teach someone to _________?

- What would happen if _________?

- What alternative can you suggest for _________?

- What solutions do you recommend?

- How would you do things differently?

- What are the next steps?

- What factors would need to change in order for __________?

- Invent a _________ to __________.

- What is your theory about __________?

What are your favorite higher-order thinking questions? Come share in the WeAreTeachers HELPLINE group on Facebook .

Plus, 100+ critical thinking questions for students to ask about anything ..

You Might Also Like

What Is Higher-Order Thinking and How Do I Teach It?

Go beyond basic remembering and understanding. Continue Reading

Copyright © 2023. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

- Members Sign Up

- Members Login

Toddler Talk 2.0

Toddler talking 2.0.

- Preschool Talk 2.0

- Late Talker

- Speech Disorders

- Language Disorders

- Reading and Writing

- Development

- Speech Therapy

- Read, Talk, Play Tips!

- Speech-Language Activities

Story Companions

- Baby Activities

- Toddler Activities

- School-Aged Activities

- General Speech-Language

- Articulation

WH Questions

- Social Language

- Receptive Language

- Grammar Games

- Story Grammar

- Speech Therapy Toys

- Holiday Activities

- Free Home Therapy ideas

- High Frequency Words

- Teletherapy

- Augmentative Alternative Communication (AAC)

- Documentation

- Back To School

- Spanish Materials

- Bilingual Development

- Bilingual Therapy

- Accent Modification

- Zero Prep Articulation

Everything You Needed To Know

WH Questions! Speech therapists LOVE to worry about WH questions!

You might be thinking...

- What’s the big deal?

- How can I help?

Well, if I just read your mind, I will answer all three of these questions here.

Now, this page is for Kindergarten and early elementary students. However, if you have an older child with a WH question goal, there is good information for you too.

First, why do SLPs care so much about WH questions? I actually had to stop and think about this for a second. I’m so used to assessing this ability, worrying about children’s progress, planning goals and activities that I even had to stop and say…. why in the world do I care so much?

However, the answer is both simple and complicated. Answering WH questions takes a lot of different language skills. A child must:

- Understand the question word

- Know the grammar of the question

- Understand each vocabulary word (not just the question word)

- Makes sense of the information and the social context

- Formulate a response

- Put the words together (syntax & semantics)

- Give a response

This is A LOT of language skills!

Why is it so important?

Being able to answer WH questions is crucial for:

- Participating in conversations with friends and family

- Answering questions in class

- Demonstrating knowledge on tests

- Being able to follow directions & stay safe

- Demonstrating an understanding of school material

- The list goes on...

What is the root of the problem?

Why can’t a child answer WH questions? This can be difficult to tease out.

The main questions to consider are, does the child have trouble:

- Understanding question words?

- Comprehending the grammatical structures?

- Understanding the vocabulary words?

- Formulating a grammatically correct response (demonstrating knowledge)?

- Formulating a semantically correct response (demonstrating knowledge)?

- Attending long enough to hear and understand the question?

How you work on the ability to answer WH questions will depend on the reason the child is having difficulty.

To figure this out, a consultation or evaluation by a qualified SLP is the best starting point.

Ready to help? Here we go!

If you need some no-print, evidence-based materials, check out: WH question materials (answer and explain why) and WH Questions (create your own).

If you need functional materials, please keep reading!

Expectations

1–2 years

- Answers “where” questions by looking/pointing at the correct place and/or using words

- Answers “what” questions by choosing an object or responding verbally

- Answers age-appropriate y es/no questions with words or gestures

- Asks “what’s that” questions?

- Answers “where,” “what,” “what-doing,” and “who” questions.

- Answers age-appropriate critical thinking questions (i.e., what do you wear when it is cold?)

Functional Game

Reading is one of THE best ways to develop language and even speech skills. You will see “reading” for the functional game on this page. Why mess with what works best, right?! The only difference will be HOW you read to your child.

How: Sit down with your child and pick a favorite book (preferably one with pictures and of interest to your child). Read the book with lots of animation and excitement. After reading for a bit...

- Ask “what is this?” and point to an object. See if your child can answer. If he/she can’t, say the answer and see if he/she can repeat.

- Ask “where is....?” about a pictured person/object/animal (the picture helps tremendously with the learning process). Wait to see if your child can answer. If not, answer your own question while pointing to the pictures.

- Ask “who” and “what-doing” questions (for 2-3 years old) as well as the questions listed above. If your child can’t answer a question, answer your own question by pointing to the picture and/or thinking OUT LOUD. By using these strategies, you teach your child HOW to answer a question and not just simply the answer.

Preschool (ages 3-5)

Age 3

- Answers “who,” “why,” “where,” and “how” questions

- Answers “if-what” questions (i.e., “If you are hungry, what do you do?)

- Answers “when” and “how many” questions (new)

- Answers “who,” “why,” “where,” “how,” and “if-what” questions

- Asks “why,” “what,” “where,” “when,” and “how” questions

WH Questions & Story Retell Materials

- 104 pages of materials

- Functional and great for the teaching phase of treatment!

- Learn more here

- Free samples for story companions that target WH questions and more!

FREE SAMPLE!

If you would like a free sample of my WH questions materials and ONE YEAR of FREE materials, please fill out the form below!

You'll receive a complimentary language material every month for an entire year! This is an excellent opportunity to sample the materials available at Speech Therapy Talk and add a touch of joy to your inbox.

FREE WH Question & Story Retell Material

Fill out the form below to grab your free worksheets

Functional Game

- Ask “what” and “where” questions as naturally as possible. These type of questions are easier so start here. If your child doesn’t know the right answer, point to the correct response (if possible) and talk through your reasoning. This “talking through” is the most important part.

- Ask “why,” “how,” and “when” questions while reading. These type of questions require higher level language reasoning skills. Therefore, they are tougher. To make this easier, relate the story to a real-life experience. For example, if you ask “why is George feeling sad?” and your child doesn’t know the answer. You might say, "George is feeling sad because he lost his toy. Look at the previous page, he lost his toy. Remember when you lost your toy and you cried? How did you feel? (child answers sad). That is how George feels."

Key Strategies:

- Point to pictures to help answer questions

- Talk through your reasoning

- Relate the story to real-life experiences

Early Elementary

In the early elementary years, students should be able to answer and ask "who," "where," "what," "what-doing," "why," “if-what” and "how" questions.

Even at this age, reading continues to be one of the best ways to learn how to answer WH questions.

How: Sit down with your child and pick a favorite book (preferably one with pictures and of interest to your child). Read the book with lots of animation and excitement (you know the drill)

Ask your child questions, any of the questions listed above in the “expectations section” as naturally as possible. If your child can’t answer one, try some strategies below:

- Point to pictures to help answer questions: Point to pictures as you answer questions. Any visual is a great thing in the learning process!

- Direct Teaching: If your child is having trouble with a question word such as “where,” open a book and say “where means place. Let’s find all the ‘places’ in this book.” Then, take turns pointing to different places such as a school, car, park, city, etc...

- Relate Story To Real Life: To teach higher level reasoning skills such as “what-if” and “why,” it can help to relate the story to a real-life experience.

- Talk Through Reasoning: For questions such as “what will happen next,” talk through your response. For example, if you say “what do you think will happen next?” listen to your child’s response and applaud ANY answer. If your child is way off, that is actually a good thing. You now have the opportunity to talk through how to answer prediction questions. You can say, "I think the paint will spill. See how the paint is on the edge of the table and the cat jumped on the table (while pointing). I think the cat will make the table shake and the paint will fall. Look it is already tipping! What do you think?"

Want more FUNCTIONAL ideas for your child?

We have step-by-step guides for both parents and professionals that provide FUNCTIONAL and NATURAL ways to learn language at home.

Check out the books below to see if one is the right fit for you

Encourage those precious first words

Expand those first words into a conversation

Preschool Talk

Build a strong foundation of language skills!

References:

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.). How does your child hear and talk? from https://www.asha.org/public/speech/development/chart/

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.). Your child’s communication: Kindergarten. from https://www.asha.org/public/speech/development/kindergarten/

- Lanza, J., & Flahive, L. (2008). Guide to communication milestones. East Moline, IL

- WH Questions & What You Need To Know

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

Excellent Language Skills Can Open Doors

- Parent Information

- Your Middle Schooler

- Administrators: Know Your SLP’s

- Workshops/Conferences Review

- Apps I Can Use

- Advertise On The School Speech Therapist

- Modify That Game

- TBS Speech Therapy, LLC Consulting Services

- Professional Liability for SLPs

- My Book “The School SLP”

Lively Letters

Understanding higher order language skills.

Mar 4, 2012 by Teresa Sadowski MA CCC-SLP

This article was originally posted in Your Middle Schooler: A Unique Age in February 2008. It was the first in a series of articles on Higher Order Language Development. The importance of higher order language development and what to do to foster higher order language development. In following articles I will address strategies to foster understanding and use of higher order language development. If you have a specific concern in this area contact me .

Develop Those Higher Level Language Skills!

During the middle school years, students are beginning to develop higher level language abilities. Most students do this so naturally we do not even notice. Teachers do their best to help students gradually develop mature language skills. However, students with language disabilities or just weak academic habits may have difficulty acquiring these higher level language skills.

What are some higher level language skills?

• Development of mature vocabulary • Understanding of word relationships such as homophones and homographs • Understanding and use of figurative expressions • Organization of mature sentences (oral and written) • Understanding and use of mature grammatical structures (oral and written) • Ability to draw conclusions and inferences • Ability to paraphrase and rephrase with ease • Ability to reason • Looking at things from another’s perspective

Concerns when Students do not attain higher level language skills. • Difficulty with comprehension (oral and written) • Unable to understand and make connections and associations • Difficulty understand jokes, riddles and humor in general • Inability to organize language • Writing skills will suffer • Poor problem solving skills • Inability to be flexible with language ( I will explain more about that later) • Academic success is effected • Immature pragmatic abilities (social speech skills)

Misunderstandings in social situations

Many simple activities can help foster development of higher level language skills. Keep an eye on my blog. I will continue to provide information and suggestions for intervention. If you need me to address an area ASAP or you have specific questions drop me a comment.

Related Posts

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Buy my book!

Buy the marshalla guide.

Shop through Amazon

Subscribe to the school speech therapist.

Delivered by FeedBurner

My TPT products

Try Amazon Prime

Welcome to The School Speech Therapist

This site provides information on speech and language development and remediation, for parents, teachers and administrators. This is also a place where therapists can network, share ideas, consult with each other and express concerns.

Strong language skills will not only aid success in school but in life as well.

Teresa Sadowski MA/SLP-ccc

Educational Supplies Amazon

Speech teacher’s handbook, the school speech therapist.

- Thinking about COVID 19, Schools and Speech Language Pathologists

- Schools have to get back to normal in the fall….not the “new normal”

Written by SLPs

Products i love, tsst policies and disclaimer.

Designed by Elegant Themes | Powered by WordPress

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The Origins of Higher-Order Thinking Lie in Children’s Spontaneous Talk Across the Pre-School Years

Rebecca r. frausel.

a The University of Chicago, United States of America

Catriona Silvey

b University College London, United Kingdom

Cassie Freeman

c The College Board, United States of America

Natalie Dowling

Lindsey e. richland.

d University of California Irvine, United States of America

Susan C. Levine

Steve raudenbush, susan goldin-meadow.

Higher-order thinking is relational reasoning in which multiple representations are linked together, through inferences, comparisons, abstractions, and hierarchies. We examine the development of higher-order thinking in 64 preschool-aged children, observed from 14 to 58 months in naturalistic situations at home. We used children’s spontaneous talk about and with relations (i.e., higher-order thinking talk, or HOTT) as a window onto their higher-order thinking skills. We find that surface HOTT, in which relations between representations are more immediate and easily perceptible, appears before—and is far more frequent than— structure HOTT, in which relations between representations are more abstract and less easy to perceive. Child-specific factors (including early vocabulary and gesture use, first-born status, and family income) predict differences in children’s onset (i.e., age of acquisition) of HOTT and its trajectory of use across development. Although HOTT utterances tend to be longer and more syntactically complex than non-HOTT utterances, HOTT frequently appears in non-complex utterances, and a substantial proportion of children achieve complex utterance onset prior to the onset of HOTT. This finding suggests that complex language is neither necessary nor sufficient for HOTT to occur; other factors above and beyond complex linguistic skills are involved in the onset and use of higher-order thinking. Finally, we found that the trajectory of HOTT, particularly structure HOTT—but not complex utterances—during the preschool period predicts standardized outcome measures of inference and analogy skills in grade school, which underscores the crucial role that this kind of early talk plays for later outcomes.

1. Introduction

As children acquire language, they also develop the ability to use higher-order thinking, which is the cognitive capacity to make inferences and generalizations, use classifications and taxonomies, and broadly go beyond the information given ( Bruner, 1973 ; Resnick, 1987 ). It is a crucial part of children’s emerging cognitive development, and higher-order thinking is increasingly highlighted as a focal goal for education in the 21 st century ( Koenig, 2015 ).

Despite its importance, little is known about the developmental trajectory of children’s higher-order thinking communication in naturalistic contexts (as opposed to experimental contexts, where far more is known), nor about individual variation in its use. In addition, although the human capacities for both generative, symbolic language and higher-order cognitive skills have been argued to differentiate humans from other animals ( Gentner, 2003 ; Penn, Holyoak, & Povinelli, 2008 ; Gentner & Christie, 2008 ), the relations between their development are not well understood.

In this paper, we examine the early foundations of higher-order thinking by examining children’s engagement in talk about and with relations, which we define as higher-order thinking talk (HOTT). We use longitudinal observations of 64 children, videotaped at home every 4 months from 14 to 58 months, to determine the age in development when children begin to regularly display higher-order thinking in their spontaneous talk (their HOTT onset), and we chart the trajectory of this talk over time ( Section 3.1 ). We also explore child-specific factors (e.g., first-born status, family income, early vocabulary and gesture use) that have the potential to influence the onset and developmental trajectory of HOTT ( Section 3.2 ). Furthermore, because HOTT utterances may be longer and more syntactically complex than non-HOTT utterances, we investigated the extent to which HOTT use can be disentangled from complex language use ( Section 3.3 ). Finally, we ask whether children’s early HOTT is related to their performance on standardized measures of higher-order thinking (including verbal and non-verbal analogical reasoning and text-based inferencing ability) administered years later during grade school ( Section 3.4 ). If so, this relation would validate the role of HOTT as an early index of, and potential training opportunity for, children’s higher-order thinking.

1.1. Defining Higher-Order Thinking

Higher-order thinking is, in the words of educational psychologist Lauren Resnick (1987) , “difficult to define but easy to recognize when it occurs” (pg. 44). There are as many different ways to define it as there are researchers studying it, but what most definitions have in common is that higher-order thinking involves rearranging or extending knowledge in novel ways. As Lewis and Smith (1993) say, “Higher-order thinking occurs when a person takes new information and information stored in memory and interrelates and/or rearranges and extends this information to achieve a purpose or find possible answers in perplexing situations” (pg. 136). In this paper, we use the definition of higher-order thinking offered by Resnick (1987) : Higher-order thinking involves “elaborating the given material, making inferences beyond what is explicitly presented, building adequate representations, [and] analyzing and constructing relationships” (pg. 45).

More specifically, we operationalize higher-order thinking as talk in which an individual’s utterance (a unit of speech; see the Methods section) includes reference to an inference or explanation, a comparison, an abstraction/generalization, or a hierarchy/taxonomic relationship. We identified these four types of higher-order thinking on the basis of literature reviews and pilot analyses. Together, they constitute a broad category of speech we call ‘higher-order thinking talk,’ or HOTT. We also differentiate between HOTT that references more immediate and perceivable relationships (surface) versus deeper, underlying relationships (structure), a distinction that the literature on reasoning and transfer has clarified to require different levels of skill (see Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 1999 ; Gentner & Markman, 1997 ; Gick & Holyoak, 1983 ).

1.2. Importance of Higher-Order Thinking

The ability to use higher-order thinking is increasingly recognized as critical to academic and employment success in the 21 st century ( Common Core State Standards Initiative, 2010 ; National Research Council, 2001 ; 2007 ; 2012 ; 2013 ). As technology has advanced, today’s students have fingertip access to wide Internet knowledge and information resources. At the same time, students are increasingly challenged by how best to attend to and use this information, and to organize it effectively so it can be applied to novel situations.

This dilemma is acute: students in the United States, one of the wealthiest and most well-connected countries in the world, frequently lag behind their international peers in standardized assessments of math and science ( Gonzales, 2001 ; Mullis, Martin, Gonzalez, & Chrostowski, 2004 ). Differences in teaching instruction can partially explain these gaps ( Richland, Zur, & Holyoak, 2007 ; Hiebert et al., 2003 ). For example, although American teachers use conceptually rich problems and comparisons at similar rates as teachers from higher-achieving regions such as Hong Kong or Japan, they differ in their use of visuo-spatial supports that draw students’ attention to relevant abstract relations ( Richland, Zur, & Holyoak, 2007 ). Richland and colleagues (2007) suggest that these differences might reflect different cultural orientations to relational reasoning. Developing the ability to attend to relations between representations may therefore be fundamental to supporting abstract thought and developing domain-general thinking skills, which are critical areas of concern for the modern student.

1.3. Developmental Origins of Higher-Order Thinking

Educational and developmental psychologists question when in development children ‘start’ using higher-order thinking (e.g., Walker & Gopnik, 2014 ). We take the position, however, that there is no one particular moment of onset, as children’s capacity for complex relational thinking depends on domain, context, and the specific demands of the task at hand; for example, whether or not the tasks use language. Studies using looking-time or simple physical problem-solving tasks suggest that higher-order and relational reasoning capacity at a basic level emerges very early in development. Pre-linguistic infants as young as 7 months demonstrate generalization of the same-different relation, and generalize this relation to novel pairs ( Ferry, Hespos, & Gentner, 2015 ). Paradigms exploring early causal thinking similarly show that young infants grapple with relational thinking ( Wang & Baillargeon, 2008 ). For example, 13-month-olds learned to transfer a pulling relation (where a cloth could be pulled to reach a toy) to a novel situation ( Chen, Sanchez, & Campbell, 1997 ). The fact that pre-linguistic infants can identify and transfer relationships provides some evidence that higher-order reasoning cannot be entirely dependent on language.

Researchers have found evidence of relational reasoning in experimental tasks that use language beginning around 2 years of age ( Loewenstein & Gentner, 2005 ; Christie & Gentner, 2014 ), suggesting this might also be the age at which children first use higher-order thinking in their spontaneous talk. By ages 3–4, children are much more reliable in their skills even when assessed with language-based tasks ( Richland, Morrison, & Holyoak, 2006 ), and are able to use higher-order relational reasoning when they have adequate knowledge of a task and the task demands are minimized.

Although children begin cultivating higher-order reasoning abilities very early in development, at this young age, they are still challenged by increasing relational complexity, and show susceptibility to errors related to perceptually-similar foils ( Richland, Morrison, & Holyoak, 2006 ). Early in development, children largely attend to surface-level perceptual relationships between representations (as in surface HOTT) when these are salient and available. For example, children might state that a plant stem is similar to a drinking straw because both are long and skinny. As they grow and become more knowledgeable, and as their cognitive resources expand, children more often attend to deeper functional similarities (as in structure HOTT). They begin to make adult-like judgments such as explaining that a plant stem is similar to a drinking straw because both are used to deliver nourishment to a living thing, and both use differential pressure to move liquid up the shaft ( Gentner, 1988 ). This change has been frequently described as the ‘relational shift’ ( Gentner, 1988 ; Gentner & Ratterman, 1991 ), although the nature of children’s developmental changes in relational reasoning is debated (e.g., see Goswami, 2002; Simms, Frausel & Richland, 2018 ). Whatever the cause of the change, the early prioritization of salient object-level and perceptual information may pave the way for more complex and abstract relational structures later in development.

At the same time that children are developing these more robust higher-order skills, they are simultaneously acquiring more complex language abilities. Next, we discuss relations between language and higher-order thinking development, including how specific language features (e.g., vocabulary, syntax) may be useful, or even necessary, for higher-order reasoning.

1.4. The Role of Language in Higher-Order and Relational Reasoning

Gentner and Goldin-Meadow (2003) described three models for how language could support thinking: (1) the language as lens view, or linguistic determinism, which theorizes that language shapes speakers’ perceptions of the world; (2) the language as category shift view, or linguistic relativism, which theorizes that while conceptual categories are universal, language can influence their boundaries; and (3) the language as toolkit view. Our approach best fits under this third view, which postulates that language provides concepts and strategies to support representation and reasoning skills, but does not supplant them. Language may serve to ‘bootstrap’ relational reasoning, and provide the tools for children to extract and formulate relational representations in the world. Consequently, language may also serve as a ‘bottleneck,’ preventing children who lack adequate linguistic skills from engaging in and communicating their higher-order thoughts.

1.4.1. Evidence from Experiments

The experimental literature has provided some indication that language is interrelated with reasoning proficiency. One well-documented phenomenon is that adding useful lexical items to task instructions can improve children’s proficiency. For instance, providing spatial ( in , on , under ) and relational ( top , middle , bottom ) words made 3- and 4-year-olds more proficient at a spatial mapping task ( Loewenstein & Gentner, 2005 ). Children given a challenging mapping task perform better even when provided with more abstract relational labels— Daddy , Mommy , and Baby —that convey monotonic changes in size ( Gentner & Ratterman, 1991 ; Ratterman & Gentner, 1998 ; see also Christie & Gentner, 2014 ). These studies suggest that relational reasoning can be supported by the introduction of linguistic labels denoting relational concepts; the use of relational language may invite children to form deeper relational representations.

1.4.2. Evidence from Naturalistic Studies

We turn next to the relatively few studies of spontaneous language and higher-order thinking development. Özçalışkan, Goldin-Meadow, Gentner, and Mylander (2009) asked whether being exposed to a conventional linguistic system—one that contains explicit terms to highlight comparison such as ‘like’—is essential for children to make different types of similarity comparisons. Özçalışkan and colleagues (2009) compared spontaneous comparisons made by 1-to-3-year-old typically-developing children to spontaneous comparisons made by 2-to-4-year-old deaf children who lacked exposure to a usable language model. The hearing losses of the deaf children prevented them from benefiting from spoken linguistic input, and their hearing parents had not exposed them to sign language. Nonetheless, these deaf children and their hearing families invented gesture systems called homesigns to communicate with their hearing family members ( Feldman, Goldin-Meadow, & Gleitman, 1978 ; Goldin-Meadow, 2003 ). These homesign systems are structured in language-like ways ( Goldin-Meadow & Mylander, 1984 ), but, importantly for our purposes, lack an explicit comparison term, such as ‘like.’

Özçalışkan and colleagues (2009) found that the homesigners expressed similarity relations in their gestures (e.g., point at cat + point at tiger; point at train + point at car), even though none had spontaneously developed a sign for the term ‘like.’ However, their comparisons were always between objects from the same superordinate category that shared multiple features (as in the cat-tiger and train-car examples), and thus were more limited in scope. In contrast, the typically-developing children not only used these broad comparisons, but also used more focused comparisons between objects from different superordinate categories that revolved around a single feature (e.g., highlighting the similarity in color between a red apple and a red book, or the similarity in shape between a lollipop and a balloon). Interestingly, they did so only after acquiring the word ‘like’ around 30 months.

The fact that the typically-developing children began producing these more focused comparisons, based on specific features, after they acquired the word ‘like’—and that the homesigners who lacked the word ‘like’ did not produce focused comparisons—suggests that learning and using a word for similarity may be instrumental in expressing more complex relationships between representations. Certain lexical items may be necessary for children to engage in higher-order reasoning, as when making comparisons. However, less is known about whether other aspects of language (e.g., certain types of syntactic structures) facilitate higher-order thinking use.

1.5. The Current Study

Despite the importance of higher-order and relational reasoning, and its development in tandem with other important linguistic skills in early childhood, the emergence of higher-order cognitive skills in everyday home contexts is not well understood (though see Callanan & Oakes, 1992 , who used diary records from parents to record how preschoolers’ causal questions in everyday interaction contributes to their understanding of causal knowledge structures). The current project bridges this gap through analysis of an unusually rich set of longitudinal data on children’s early talk and later thinking and reasoning skills. Sixty-four typically-developing, monolingual English-acquiring children were videotaped in their homes every 4 months between 14 and 58 months while engaging in regular, everyday activities, yielding over 1,000 hours of video. These same children were visited years later in grade school and administered standardized reasoning outcome measures.

Although early language is known to vary by socioeconomic status (SES) and to predict differences in children’s long-term school and career success, researchers have not yet examined whether these same disparities are present for higher-order reasoning development. Furthermore, little previous research has examined how the development of higher-order reasoning is related to the development of complex language abilities—in part, because the majority of studies of children’s thinking and reasoning have been conducted cross-sectionally using experimenter-derived tasks (e.g., Loewenstein & Gentner, 2005 ; Richland, Morrison, & Holyoak, 2006 ). Moreover, studies of language development using naturalistic data (e.g., Hart & Risley, 1995 ; Huttenlocher, Haight, Bryk, Seltzer, & Lyons, 1991 ) have largely examined differences in language use, such as vocabulary diversity and syntactic complexity. Little previous research has explored the nature and complexity of the thinking embedded in the spontaneous talk produced by children early in development.

Despite these traditionally distinct research pathways, the spontaneous use of conceptually and linguistically complex language in early childhood may have long-term impacts on children’s later thinking and reasoning skills. The spontaneous home talk collected and coded in this study spans from 14 months to 58 months, a crucial period in which language emerges and grows in complexity, and which also represents a period of great growth in children’s thinking and reasoning development. These data thus allow for new insights into the development of children’s thinking and reasoning as expressed through their early language.

1.6. Research Questions

This paper addresses four research questions.

1.6.1. How do children from 14–58 months vary in their onset and developmental trajectory of spontaneous higher-order thinking talk (HOTT)?

Based on the experimental literature (e.g., Loewenstein & Gentner, 2005 ; Christie & Gentner, 2014 ), we predict that HOTT will emerge with regularity around the beginning of the second year of life. Furthermore, we predict that children will vary widely in their onset and trajectory of HOTT, just as they exhibit great variability in their early lexicons ( Huttenlocher, et al., 1991 ), syntax ( Huttenlocher, Vasilyeva, Cymerman, & Levine, 2002 ), and other linguistic skills. Finally, we predict that, due to the different levels of skill required when identifying deeper, more abstract relationships in contrast to simpler, more immediate relationships, onset of structure HOTT will occur later in development than onset of surface HOTT.

1.6.2. What child-specific factors, such as family income, birth order, and early language use, are associated with the onset and trajectory of HOTT?

We expect that HOTT might be another language area, similar to vocabulary (e.g., Hart & Risley, 1995 ), where we find socioeconomic disparities. Children whose parents have higher incomes may use HOTT earlier and more often overall. In addition, we might expect birth order to influence input and use, since the oldest or only child may receive more individualized input from his or her parents, resulting in earlier or more frequent HOTT use. Finally, early language use might influence HOTT. Children with larger vocabularies early in development, or who use a wider variety of gestures to communicate, may elicit richer input from their caregivers, which may result in earlier onset of HOTT and more HOTT use across development.

1.6.3. What is the relation between HOTT and complex language?

Previous research has focused on relations between higher-order thinking and vocabulary. We expand this inquiry to explore two related questions concerning the extent to which HOTT use can be disentangled from complex language use.

Our first question is whether HOTT utterances are longer and more complex than non-HOTT utterances. To answer this question, we assessed the linguistic form (utterance length and verbs per utterance) of surface HOTT, structure HOTT, and non-HOTT utterances. If HOTT utterances are comprised primarily of complex utterances (which we define as utterances containing two or more verbs), this would suggest that our measure of HOTT largely reduces to being another measure of language complexity. Furthermore, it would suggest that describing complex relationships in the world necessarily requires speakers to use complex language—not just certain kinds of words, but lengthier speech and more complex syntax. If, however, HOTT appears in non-complex utterances as well as complex utterances, this would suggest that HOTT and complex language, although perhaps related, are not redundant. Complex language may provide speakers with strategies to support complex representation and reasoning, but may not be necessary for it to occur.

Our second question is whether the onset of HOTT coincides with the onset of complex utterances. Complex utterances allow the expression of two or more propositions within a single utterance, and thus have the potential to foster an understanding of relations between those propositions; children may start using HOTT at the same time they start using complex language. But if onset of complex language precedes onset of HOTT, we would have evidence that, although having complex language may relate to higher-order thinking development, complex language alone is not sufficient. The ability to identify and articulate relations between representations in the world using HOTT may call upon additional cognitive and linguistic skills beyond the ability to construct a complex utterance.

1.6.4. How is HOTT use from 14–58 months related to reasoning outcomes in grade school, including analogical reasoning and inferencing ability?

We explore, for the first time, whether higher-order thinking skills are related across development, as are skills in domains such as math (e.g., Mazzocco, Feigenson, & Halberda, 2011 ; Stevenson & Newman, 1986 ; Case, Griffin, & Kelly, 1999 ). Finding that relationships across development are weak would suggest that factors later in development (e.g., schooling) are needed to explain individual differences in higher-order thinking outcomes.

Overall, the current manuscript focuses on research questions pertaining to identifying HOTT as an important characteristic of children’s early spontaneous language, mapping its developmental trajectory and relations to individual characteristics such as family income, and assessing its predictive validity for future higher-order thinking skills. Determining contributions and mechanisms underlying these patterns, including the role of parent HOTT input, is beyond the scope of this manuscript, though future analyses will be important in exploring these questions.

2.1. Participants

Sixty-four typically-developing children and their primary caregiver(s) participated as part of a larger study of language development ( Goldin-Meadow, et al., 2014 ). Participants were recruited from the greater Chicago area. In order to recruit children and families, direct mailings were sent to approximately 5,000 families living in targeted zip codes, and advertisements were placed in a free, monthly parenting magazine. Responding parents were asked to confirm that they were raising their children in an English-only language environment (approximately 85–90% English, based on parent report). Given that they met this criterion, families were then interviewed for information on their background characteristics in order to create a sample that was demographically representative of the greater Chicago area, as reported in the 2000 U.S. Census.

The resulting final sample has 31 girls and 33 boys, including 34 first-born or only children. The sample was ethnically diverse, including 14 African American, 9 Latino, 35 White, and 6 children of mixed race. At the beginning of the study period, 5 families reported incomes of less than $15,000; 13 had incomes between $15,000 and $34,999; 8 had incomes between $35,000 and $49,999; 13 had incomes between $50,000 and $74,999; 11 had incomes between $75,000 and $99,000, and 14 reported incomes greater than $100,000. Using the midpoint of each income category as an estimate, the sample had an average income of $61,000 ( SD = $32,000).

Parents were asked to report who was primarily responsible for childcare. This person was asked to be home during filming of the home visits. The majority of children ( n = 56) had the mother as the primary caregiver, two children had the father as the primary caregiver, and six families reported that both parents equally shared the role (referred to as dual caregivers). Primary caregivers had an average of 15.6 years ( SD = 2.2 years, range 10 to 18 years) of education, the equivalent of slightly less than a Bachelor’s degree (the mother’s education level was used for the dual caregiver families).

2.2. Procedure

Children were videotaped interacting with the primary caregiver(s) during twelve 90-minute home visits conducted every 4 months from 14 to 58 months. This age range was selected because it represents the period during which children first began to produce language until they entered school. Parents and children were recorded engaging in ordinary, everyday activities such as playing with toys, reading books, and having meals. Not all participants completed every session; on average, subjects completed 11.3 sessions ( SD = 1.8 sessions, range 4 to 12 sessions). Out of a possible 768 session visits (64 subjects x 12 visits each), a total of 726 visits were completed; i.e., only 5.5% of visits were missing.

In addition, children were visited in their homes annually or bi-annually beginning in grade school and continuing through late adolescence. We examine whether children’s early HOTT is related to longer-term reasoning outcomes. The reasoning outcome measures are standardized measures of text-based inferencing given to children at age 9 and verbal and non-verbal analogy given at age 11. When children were 10, their parents completed IQ measures, which we use as a covariate. These measures will be discussed below in Section 2.6 , Standardized Measures.

2.2.1. Transcription of Speech in Spontaneous Interactions

All spontaneous speech by children was transcribed, including all dictionary words, onomatopoeic sounds (e.g., woof-woof), and evaluative sounds (e.g., uh-oh). Ritualized or memorized speech, such as song (e.g., singing the ABC’s) and prayer (e.g., reciting the Lord’s Prayer), was not transcribed. Although a small number of utterances consisting of verbatim reading from books was initially transcribed ( n = 375), these utterances were removed from analyses to more accurately capture children’s use of spontaneous language. Transcribed speech was divided into utterances, defined as any sequence of words preceded and followed by a pause, a change in intonational pattern, or a change in conversational turn ( Rowe & Goldin-Meadow, 2009 ; Rowe, 2012 ). A total of 368,509 child utterances were analyzed, distributed across the 726 visit transcripts.

One out of every three transcripts was checked for transcription agreement; agreement was calculated at the utterance level and the word level, and transcribers had to be at least 90% in agreement for both measures. Ten minutes of each video (randomly selected from the whole video) were transcribed by a second coder. If the first 10 minutes was not at least 90% in agreement, a second 10 minutes were transcribed by the second coder. If the transcript was still not at least 90% in agreement, the transcript was sent back to the coder to be re-transcribed. After re-transcription, another 10 minutes would be transcribed by the second coder. This process continued until all reliability transcripts were at least 90% in agreement for both words and utterance boundaries.

2.3. Coding Higher-Order Thinking Talk in Spontaneous Interactions

Each parent and child utterance was coded for the presence of HOTT, although this paper only examines child utterances. HOTT is talk that indexes two or more representations and constructs a bridge or link between them. HOTT was coded when the child’s utterance contained both representations and the link between them; for example, “They’re laughing because he fell down.” In this example, the representations indexed are two events—people laughing and a person falling down—and the link between them, the word ‘because,’ implies causality. HOTT was also coded when the child responded to a HOTT-eliciting question; for example, a parent asks, “Why were they laughing?” and the child replies, “Because he fell down,” where the question provides one representation and the response provides the second representation. HOTT was also coded when the child asked the HOTT-eliciting question; for example, if the child asks, “Why were they laughing?”

Reliability analyses were performed for parent and child speech combined due to the interdependent nature of the coding, which relied on surrounding talk. Ninety-seven transcripts (approximately 8 from each time point), constituting 13.3% of the transcripts, were coded by two or more people. The mean interrater percent agreement for identification of utterances as HOTT or not was 98.1% (range: 96.0–99.3%).

We also computed Cohen’s kappa ( Cohen, 1968 ), which assesses the reliability of assigning observations to mutually exclusive categories while correcting for chance agreement. It has values ranging from −1 to 1, though Cohen (1968) notes that values less than 0 are unlikely in practice, so it generally ranges from 0 to 1; values 0.40–0.59 are regarded as moderate, values 0.60–0.79 are regarded as substantial, and values over 0.80 are regarded as almost perfect ( McHugh, 2012 ). The mean Cohen’s kappa for identification of utterances as HOTT or not was 0.81 (range 0.73–0.87). Disagreements were resolved through discussion or by the more experienced coders.

2.3.1. Coding the Four Types of HOTT

For this study, four types of links or relationships between representations were included in HOTT: inference, comparison, abstraction, and hierarchy. Although many types of relations could be considered ‘higher-order,’ these four related skills are particularly useful for educational application ( Anderson, Greeno, Reder, & Simon, 2000 ; Dumas, Alexander, & Grossnickle, 2013 ; Halford, Wilson, & Phillips, 2010 ; Speed, 2010 ). The four types of HOTT that we coded are defined and illustrated below. Due to the relative infrequency of HOTT within spontaneous discourse, we analyze the types of HOTT as a combined set.

We calculated reliability for each HOTT type independently. Mean interrater percent agreement was 99.3% (range 99.1–99.7%; M kappa = 0.86; range kappa 0.79–0.92) for inferences; 99.4% (range 99.0–99.9%; M kappa = 0.71; range kappa 0.58–0.82) for comparisons; 99.8% (range 99.4–99.9%; M kappa = 0.62, range kappa 0.41–0.81) for abstractions; and 99.9% (range 99.8–100%; M kappa = 0.72; range kappa 0.40–1.0) for hierarchies.

Inference is defined as deriving a conclusion not otherwise given by using known (or logical) premises. The bridge between representations in inferences is cause-and-effect, a conditional, or speculation based on reasoning. For example, one 54-month-old child said, “If I didn’t have teeth, then I couldn’t eat candy.” This utterance arose as part of a conversation about the child’s favorite part of her body. In this example, the child uses conditional reasoning to infer, in a situation where she had no teeth [representation 1], what might happen—she would be unable to eat candy [representation 2].

Comparison:

Comparison is defined as demonstrating similarities or differences between entities by analogy or by example. The bridge between representations in comparisons is of similarity or difference. For example, the utterance, “A tornado is a like a mean monster” indexes the representations of ‘tornado’ and ‘monster’ and links them through the word “like.” An utterance such as, “The blue stick is longer than the red stick” also illustrates a comparison between two representations—the blue stick and the red stick—based on a featural difference (in this example, length).

Abstraction:

Abstraction is defined as pointing out mental frameworks or models that could facilitate thinking, or making definitions that attempt to describe the meaning of a word or concept, beyond giving a label. In abstractions, representations are bridged through generalizations or definitions. One sample abstraction utterance is, “Every Halloween you can be something new.” Here the two representations, ‘Halloween’ and ‘what you can be,’ are linked through the use of the term “every,” invoking a generalization about Halloween. Abstractions can also take the form of generalizing or generic statements that ascribe defining characteristics to a concept, such as “Big kids carry their own plates.” In this example, carrying one’s own plates is defined as a quality of big kids. Abstractions could also take the form of word definitions, as in the utterance, “‘Spa’ means there’s a new place that has a bath.”

Finally, hierarchy is defined as an arrangement of categories with a superordinate or subordinate framework. An utterance such as, “A hammer is a type of tool,” demonstrates a hierarchical relationship by indexing the representations of ‘hammer’ and ‘tool,’ which are linked through the use of the word ‘type,’ stating that hammers belong to a broader category of tools. More rarely, families used more abstract classifications to denote hierarchies, as in the utterance, “Killer whales are in the dolphin family.”

2.3.2. Coding Surface and Structure HOTT

In addition to coding the type of higher-order relationship, each HOTT utterance was coded for conceptual complexity. Surface HOTT is defined as a single-level mapping where the relationship between the referents is not complex, and not dependent on a deep understanding of the referents indexed; the types of correspondences identified were often easy to perceive and more immediate ( Richland & Simms, 2015 ). For example, a surface inference is, “You knocked it so it fell down,” and a surface comparison is, “Those are both red.” In contrast, structure HOTT is defined as more complex mapping at a systemic level, and requires a deeper understanding of the ideas being linked. The types of correspondences identified are often relatively abstract ( Richland & Simms, 2015 ). For example, a structure inference is, “She’s sad because she misses her momma,” and a structure comparison is, “I want to be brave like Piglet.” Appendix A contains additional criteria and further examples of surface and structure HOTT for each of the four types of HOTT.

Utterances that contain multiple types of HOTT were automatically coded as structure. For example, one child describes a drink she was having at a restaurant by saying, “It was just like Coke because it was spicy.” She illustrates the similarity between the unknown drink and Coke using the word ‘like,’ and justifies their similarity using the word ‘because.’ Multiple types were found in only 3% of children’s HOTT utterances; the remaining 97% of HOTT utterances contained only one type of relationship.

Two coders coded the surface/structure distinction on all HOTT utterances after achieving a mean 98.3% agreement ( κmean = 0.84) on 126 transcripts (which comprised 17% of the 726 transcripts in the corpus). Appendix B reports the frequency of each HOTT type across development. As noted above, for the remainder of this paper, we collapse across HOTT types, and instead focus our analyses on the two levels of HOTT complexity (surface vs. structure).

2.4. Coding Language Complexity in Spontaneous Interactions

2.4.1. utterance length.

The number of words in each utterance was coded to calculate mean length of utterance (in words rather than morphemes; MLU-w) for each child at each session ( Demir, Rowe, Heller, Goldin-Meadow, & Levine, 2015 ). We calculate the average MLU-w for surface HOTT, structure HOTT, and non-HOTT utterances at each timepoint in the corpus.

2.4.2. Syntactic Complexity

Each word of each utterance was also tagged for part of speech using CLAN tools ( MacWhinney, 2000 ). The number of verbs in each utterance was used as a measure of syntactic complexity, because it correlated strongly ( r = .88, p < 0.001) with number of clauses per utterance that were coded manually on a subset of the data. Any utterance containing two or more verbs was classified as a complex utterance.

2.5. Early Child Word and Gesture Types in Spontaneous Interactions as Covariates

2.5.1. child word types at 14 months.

We used the number of different word types children produced at 14 months to control for early vocabulary and linguistic skill. Child word types at 14 months ranged from 0 to 59 ( M = 14.0, SD = 14.5).

2.5.2. Child Gesture Types at 14 Months

The spontaneous communicative gestures that children produce can serve as an early index of variation in subsequent linguistic skill ( Iverson, Capirci, Volterra, & Goldin-Meadow, 2008 ; Rowe & Goldin-Meadow, 2009 ). Therefore, in addition to speech transcription, gestures were isolated from parents’ and children’s motor behavior, and lexical meanings were attributed to the gestures using coding criteria reported in previous studies ( Goldin-Meadow & Mylander, 1984 ). We use the number of gesture types that children produced at 14 months as another indicator of early linguistic skill. Gesture types was defined as the number of different meanings conveyed by gesture. We counted each conventional and representational gesture used by children associated with a different meaning (e.g., shake head no to convey no ; arms flapping to convey flying ), as well as each deictic gesture that indicated a different object as a distinct gesture type. Child gesture types at 14 months ranged from 4 to 54 ( M = 21.7, SD = 12.5).

2.6. Standardized Measures

2.6.1. child higher-order thinking outcome measures.

At ages 9 and 11, participants were administered four standardized outcome measures of higher-order thinking in their homes, including text-based inferencing ability and analogical reasoning. Ten children dropped out of the study in the early period and thus were not given any of the outcome measures. Out of the 54 participants who took the outcome measures, 48 had all four measures; two children were each missing a single measure (one from age 9 and one from age 11), and four were missing both measures at age 11. The four measures are described below.

Diagnostic Assessment of Reading Comprehension:

To assess inferential ability, participants took the Diagnostic Assessment of Reading Comprehension (DARC; August, Francis, & Calderón, 2002 ) at age 9. The DARC has 164 multiple choice items designed to test reading comprehension components, including text memory, text inferencing, knowledge access, knowledge integration, and inference, while controlling for background knowledge. Fifty-three children completed this measure. The mean was 33.9 questions correct ( SD = 7.1, range 14 to 45) on the 45 questions that tested knowledge integration and text inferencing (components of higher-order thinking).

Gates-MacGinitie:

To assess inferencing in a school-like task, and to complement the DARC, we administered the Gates-MacGinitie (GM; MacGinitie, MacGinitie, Maria, & Dreyer, 2002 ). This norm-referenced assessment contains vocabulary and reading comprehension sections with both literal and inferential questions, and is widely used in school settings. We administered the measure to the participants in both the fall and spring at ages 8 and 9. For this paper, the age 9 fall and spring scores were analyzed (averaged together, after finding that these two outcome measures were highly correlated; r = 0.80, p < 0.001) in order to complement the DARC, also administered at age 9. Fifty participants completed this outcome measure both times, and four children completed either the fall or spring outcome measure (3 were missing the fall score, and 1 was missing the spring score). The mean score was 512.1 ( SD = 39.7; range 425.5 to 590.5) for the 54 children.

Ravens Progressive Matrices: